Abstract

The identification of microRNAs (miRNAs) has established new mechanisms that control skeletal muscle adaptation to exercise. The present study investigated the mRNA regulation of components of the miRNA biogenesis pathway (Drosha, Dicer and Exportin-5), muscle enriched miRNAs, (miR-1, -133a, -133b and -206), and several miRNAs dysregulated in muscle myopathies (miR-9, -23, -29, -31 and -181). Measurements were made in muscle biopsies from nine healthy untrained males at rest, 3 h following an acute bout of moderate-intensity endurance cycling and following 10 days of endurance training. Bioinformatics analysis was used to predict potential miRNA targets. In the 3 h period following the acute exercise bout, Drosha, Dicer and Exportin-5, as well as miR-1, -133a, -133-b and -181a were all increased. In contrast miR-9, -23a, -23b and -31 were decreased. Short-term training increased miR-1 and -29b, while miR-31 remained decreased. Negative correlations were observed between miR-9 and HDAC4 protein (r=−0.71; P= 0.04), miR-31 and HDAC4 protein (r =−0.87; P= 0.026) and miR-31 and NRF1 protein (r =−0.77; P= 0.01) 3 h following exercise. miR-31 binding to the HDAC4 and NRF1 3′ untranslated region (UTR) reduced luciferase reporter activity. Exercise rapidly and transiently regulates several miRNA species in muscle. Several of these miRNAs may be involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle regeneration, gene transcription and mitochondrial biogenesis. Identifying endurance exercise-mediated stress signals regulating skeletal muscle miRNAs, as well as validating their targets and regulatory pathways post exercise, will advance our understanding of their potential role/s in human health.

Key points

The discovery of microRNAs (miRNAs) has established new mechanisms that control health, but little is known about the regulation of skeletal muscle miRNAs in response to exercise.

This study investigated components of the miRNA biogenesis pathway (Drosha, Dicer and Exportin-5), muscle enriched miRNAs, (miR-1, -133a, -133b and 206), and several miRNAs dysregulated in muscle myopathies, and showed that 3 h following an acute exercise bout, Drosha, Dicer and Exportin-5, as well as miR-1, -133a, -133-b and miR-181a were all increased, while miR-9, -23a, -23b and -31 were decreased.

Short-term training increased miR-1 and miR-29b, while miR-31 remained decreased.

Negative correlations were observed between miR-9 and HDAC4 protein, miR-31 and HDAC4 protein and between miR-31 and NRF1 protein, 3 h after exercise.

miR-31 binding to the HDAC4 and NRF1 3′ untranslated region (UTR) reduced luciferase reporter activity.

Exercise rapidly and transiently regulates several miRNA species potentially involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle regeneration, gene transcription and mitochondrial biogenesis.

Introduction

Endurance exercise elicits important cellular stress signals responsible for skeletal muscle adaptation. Common adaptations, such as improved mechanical, metabolic, neuromuscular and contractile function, are influenced by the transcriptional and translational regulation of genes that encode the proteins controlling these processes (Dela et al. 1994; Russell et al. 2003, 2005; Short et al. 2003; Wadley et al. 2007). Control of exercise-mediated skeletal muscle gene transcription and translation is regulated by transcription factor activation (Keller et al. 2001; McGee et al. 2006), histone modification (McGee et al. 2009) and DNA methylation (Nakajima et al. 2010; Barres et al. 2012). However, the discovery of microRNAs (miRNAs) (Lee et al. 1993; Reinhart et al. 2000) has revealed another level of complexity in transcriptional and translational regulation (Bartel, 2004).

miRNAs, small (∼20–30 nucleotides) non-coding ribonucleic acids (RNAs), inhibit protein translation or enhance messenger RNA (mRNA) degradation (Hamilton & Baulcombe, 1999; Reinhart et al. 2000). miRNA biogenesis occurs in the nucleus with the transcription of primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) transcripts (Bartel, 2004). The pri-miRNA is then cleaved into a ∼60–70 nt miRNA precursor (pre-miRNA) by the RNase-III type endonuclease Drosha associated to Pasha (also known as DGCR8), exported to the cytoplasm by Exportin-5 (XPO5) and cut into a ∼22 nt miRNA duplex by Dicer (Lee et al. 2003; Lund et al. 2004). One of the duplex strands is degraded, while the other confers the mature miRNA; the latter is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). This mature miRNA allows the RISC to identify and bind to the 3′ or 5′ untranslated regions (UTR) of the target mRNAs, resulting in its degradation or repression of protein translation (Bartel, 2004; Lee et al. 2009). It has been suggested that destabilisation of target mRNAs is the predominant reason for reduced protein output (Guo et al. 2010).

Skeletal and cardiac muscle show an enrichment of miR-1, -133a, -133b, -206, -208a, -208b, -486 and -499 (McCarthy & Esser, 2007; Callis et al. 2008; van Rooij et al. 2008, 2009; Small et al. 2010). Muscle-enriched miRNAs (commonly referred to as myomiRs) influence multiple facets of muscle development and function through their regulation of key genes controlling myogenesis (Chen et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2006; Rao et al. 2006), myosin heavy chain expression (McCarthy et al. 2009; van Rooij et al. 2009) and growth-promoting signalling pathways (Small et al. 2010). These miRNAs can be regulated by MyoD, MEF2, SRF (Liu et al. 2007; van Rooij et al. 2008; Liu & Olson, 2010) and myocardin-related transcription factor-A (MRTF-A; Small et al. 2010). These transcription factors and transcriptional co-activators are upregulated in human skeletal muscle following exercise (Yang et al. 2005; McGee et al. 2006; Lamon et al. 2009). The regulation of muscle enriched miRNAs following endurance exercise is underexplored. However, miR-1 and miR-133a are sensitive to muscle contraction in response to endurance (Safdar et al. 2009; Nielsen et al. 2010; Aoi et al. 2010) and resistance (Drummond et al. 2008) exercise.

The muscle enriched miRNAs-1, -133a and -206, as well as several other miRNAs including miR-9, -23, -29, -31 and -181, show dysregulation in several human myopathies and dystrophies (Eisenberg et al. 2009; Greco et al. 2009; Gambardella et al. 2010). Several of these miRNA species are also dysregulated in skeletal muscle of chronic disease conditions characterised by impaired exercise capacity, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; Lewis et al. 2012), chronic kidney disease (CKD; Wang et al. 2011) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; Williams et al. 2009; Russell et al. 2012), as well as following bed-rest (Ringholm et al. 2011). Reduced skeletal muscle activity caused by cessation of training also regulates miRNA levels (Nielsen et al. 2010). Whether an increase in skeletal muscle activity stimulated via acute endurance exercise or endurance training also regulates miR-9, -23, -29, -31 and -181 in human skeletal muscle is unknown.

Given the fundamental role of miRNAs in transcription and transcriptional regulation, we measured (1) expression levels of members of the miRNA biogenesis complex, (2) muscle-enriched miRNAs and (3) miRNAs known to be dysregulated in muscle wasting and chronic disease conditions. Measurements were made in human skeletal muscle biopsy samples following a single bout of moderate-intensity endurance cycling exercise, as well as after 10 days of combined moderate- or high-intensity endurance cycling training.

Methods

Subjects

The nine male subjects participating in this study were healthy but exercised less than 2 h per week (peak pulmonary oxygen consumption ( ) of 44.1 ± 7.2 ml min−1 kg−1; age, 23 ± 5 years; height, 178 ± 8 cm; weight, 79 ± 8 kg; Benziane et al. 2008). The subjects were fully informed of the possible risks involved in the study before providing written consent. The study was approved by the Monash University Standing Committee on Ethics in Research Involving Humans and Karolinska Institutet Ethics Committee. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration.

) of 44.1 ± 7.2 ml min−1 kg−1; age, 23 ± 5 years; height, 178 ± 8 cm; weight, 79 ± 8 kg; Benziane et al. 2008). The subjects were fully informed of the possible risks involved in the study before providing written consent. The study was approved by the Monash University Standing Committee on Ethics in Research Involving Humans and Karolinska Institutet Ethics Committee. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration.

Peak pulmonary oxygen consumption

tests were completed on an electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer (Lode B.V medical technology, Groningen, The Netherlands). Participants cycled at an initial workload of 100 W, which increased to 150 W after 2.5 min, followed by a 25 W increase every 2.5 min until volitional exhaustion. Volitional fatigue was defined as the point at which the subjects’ cadence decreased below 60 rpm and/or a respiratory exchange ratio (RER) of 1.12.

tests were completed on an electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer (Lode B.V medical technology, Groningen, The Netherlands). Participants cycled at an initial workload of 100 W, which increased to 150 W after 2.5 min, followed by a 25 W increase every 2.5 min until volitional exhaustion. Volitional fatigue was defined as the point at which the subjects’ cadence decreased below 60 rpm and/or a respiratory exchange ratio (RER) of 1.12.  was determined as the average over the last minute from samples measured every 10 s (MOXUS metabolic system, AEI Technologies, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) corresponding to the highest

was determined as the average over the last minute from samples measured every 10 s (MOXUS metabolic system, AEI Technologies, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) corresponding to the highest  that occurred in the last minute of the test. Peak power output (PPO) was also measured. These parameters were used to determine the exercise intensities of 70, 75% and 90% of individual

that occurred in the last minute of the test. Peak power output (PPO) was also measured. These parameters were used to determine the exercise intensities of 70, 75% and 90% of individual  for the relevant exercise tests and training sessions.

for the relevant exercise tests and training sessions.

Exercise tests and training

One week after completing the  test, subjects completed a pre-training acute exercise trial which consisted of cycling for 60 min at ∼70% of their

test, subjects completed a pre-training acute exercise trial which consisted of cycling for 60 min at ∼70% of their  . The cycle training regimen commenced ∼7 days later. Training consisted of 10 days of endurance training on the Lode cycle ergometer, including 4 days of high-intensity interval training as described previously (Benziane et al. 2008). This protocol improves exercise performance and activates molecular signalling pathways controlling metabolism in humans (Benziane et al. 2008). Each subject performed the same relative level of exercise. Subjects rode at ∼75% of their

. The cycle training regimen commenced ∼7 days later. Training consisted of 10 days of endurance training on the Lode cycle ergometer, including 4 days of high-intensity interval training as described previously (Benziane et al. 2008). This protocol improves exercise performance and activates molecular signalling pathways controlling metabolism in humans (Benziane et al. 2008). Each subject performed the same relative level of exercise. Subjects rode at ∼75% of their  for 45 min on days 1, 5, 6, and 10, for 60 min on day 3, and 90 min on day 8. High-intensity training took place on days 2, 4, 7, and 9, consisting of 6 × 5 min intervals at ∼90–100% of subjects’

for 45 min on days 1, 5, 6, and 10, for 60 min on day 3, and 90 min on day 8. High-intensity training took place on days 2, 4, 7, and 9, consisting of 6 × 5 min intervals at ∼90–100% of subjects’ with 2 min recovery at or below 40%

with 2 min recovery at or below 40% between exercise bouts. A second

between exercise bouts. A second  test was performed 4 days after the training period. All tests were performed in the fasted state. Subjects were instructed to abstain from caffeinated products and alcoholic beverages 24 h before the exercise trials while consuming their normal diet, which they recorded in daily food diaries during the 3 days before the exercise trials. They were instructed to consume the same food or record any changes from the initial diet. Food diaries were analysed for total energy consumption and the relative energy sources were 52% CHO, 20% fat and 28% protein. This dietary control was effective, since diet and energy consumption were unchanged.

test was performed 4 days after the training period. All tests were performed in the fasted state. Subjects were instructed to abstain from caffeinated products and alcoholic beverages 24 h before the exercise trials while consuming their normal diet, which they recorded in daily food diaries during the 3 days before the exercise trials. They were instructed to consume the same food or record any changes from the initial diet. Food diaries were analysed for total energy consumption and the relative energy sources were 52% CHO, 20% fat and 28% protein. This dietary control was effective, since diet and energy consumption were unchanged.

Muscle biopsy

Three muscle biopsies were taken from the same thigh but from three separate incisions 20–50 mm apart. An area on the thigh over the vastus lateralis was cleaned and sterilised. The skin was anaesthetised with lignocaine (5% xylocaine; AstraZeneca, North Ryde, Australia) and an incision was made through the skin and muscle fascia. The first muscle biopsy (150—250 mg) was taken at rest using the percutaneous needle biopsy technique with suction applied. Following the initial biopsy, subjects completed the acute 1 h exercise cycling test. Thereafter, the subjects rested in a supine position and were instructed to keep as still as possible for 3 h after which a second biopsy was taken. A third muscle biopsy was taken 2 days after the last training session which also occurred 2 days before the last  test was performed. Muscle biopsies were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis.

test was performed. Muscle biopsies were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription

RNA was extracted from ∼30 mg of skeletal muscle samples using Tri-Reagent® Solution (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA concentration was assessed using the Nanodrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The ratio between A260/A280 was 1.75 to 1.95 for all samples. RNA quality was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). The RNA integrity number (RIN) was between 7.5 and 9.0 for all samples. One microgram of total RNA was DNAse treated for 15 min at room temperature using Sigma DNase treatment kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). The reaction was inactivated for 10 min at 70°C. First-strand cDNA was generated from 1 μg RNA in 20 μl reaction buffer using the High Capacity RT-kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA); 1 × RT buffer and random primers, 8 mm dNTP and 2.5 U μl−1 MultiScribe™ RT enzyme. The RT protocol consisted of 10 min at 25°C, 120 min at 37°C, 5 min at 85°C then cooled to 4°C. Before diluting cDNA, 1 μl ribonuclease H (RNase H; Life Technologies, Mulgrave, VIC, Australia) was added to each sample and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The cDNA was stored at −20°C until further analysis.

mRNA and miRNA analyses using real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was carried out using a Stratagene MX3000 thermal cycler to measure mRNA and miRNA levels. mRNA levels for Drosha, Dicer and Exportin-5, NRF1, Mfn1, Mfn2, atrogin-1/MAFbx, eIF4e, p70s6k, HDAC4, FoXO1 and FoxO3a were measured using 1 × SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA; no. 4309155) and 5 ng of cDNA. All primers were used at a final concentration of 300 nm. Primer details are presented in Table 1. The PCR condition conditions were 1 cycle of 10 min at 95°C; 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 60 s at 60°C, 60 s at 72°C; 1 cycle (melting curve) 60 s at 90°C, 30 s at 55°C, 30 s at 95°C. To compensate for variations in input RNA amounts and efficiency of the reverse transcription, data were normalised to cDNA input as quantified using Oligreen (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as published by our group (Cannata et al. 2010). Primers were designed using Primer3 software, verified using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) and synthesised by Geneworks (Hindmarsh, SA, Australia). miRNA levels were measured using specific primer and probes sets as per the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA; Russell et al. 2012; Table 2) using the 1 × Taqman Universal Master Mix II, no UNG kit (Applied Biosystems; no. 4440047). For miRNA analyses, RNA (10 ng) was reverse transcribed using the Taqman microRNA Reverse Transcription (RT) kit (Applied Biosystems). The RT reaction consisted of 1 mm dNTP, 0.27 U μl−1 RNase inhibitor, 3.3 U μl−1 MultiScribe™ enzyme, 1 × buffer and 7.5 × diluted primers. The RT conditions consisted of 30 min at 16°C, 30 min at 42°C, 5 min at 85°C then cooled to 4°C. PCR plates and films were purchased from Axygen Scientific, Inc. (Union City, CA, USA). miRNA primers were diluted 40×. PCR conditions consisted of 1 cycle of 10 min at 95°C; 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 60 s at 60°C. RNU48 was used as an endogenous control. All samples were run in triplicate for all mRNA and miRNA targets measured. All analysis was performed using the Stratagene MX3000 thermal cycler dedicated software and employed the DdCt method.

Table 1.

Details for the primers used in the present study

| Gene symbol | Sequence accession number | Primer name | Sequence | Length | Primer location | Annealing temp. | Dynamic range (cycles) | Slope | Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DROSHA | NM_013235 | h Drosha For | ACTGTGGCTGTTTATTTCAAGGG | 100 | Exon 34 | 60 | 23.80–28.89 | y=−3.38 | 97.8 |

| h Drosha Rev | ATTTTTCAAGCGCATCCATTG | Exon 35/36 | |||||||

| XPO5 | NM_020750 | h Exportin 5 For | GCGCCGAAAGGACCA | 98 | Exon 31 | 60 | 26.82–31.78 | y=−3.32 | 99.9 |

| h Exportin 5 Rev | AGGGAAGATTCTTAATGTGAACTTCTT | Exon 32 | |||||||

| DICER1 | NM_177438 | h Dicer For | ATCCCATGATGCGGCC | 100 | Exon 28/29 | 60 | 21.93–26.84 | y=−3.29 | 101.4 |

| h Dicer Rev | CTAAATTTGGCAGTTTCTGGTTCC | Exon 29/ 30a/b | |||||||

| NRF1 | NM_005011 | h NRF1 For | GGTGCAGCACCTTTGGAGAA | 73 | Exon 5 | 60 | 25.67–30.95 | y=−3.53 | 91.9 |

| h NRF1 Rev | CCAGAGCAGACTCCAGGTCTTC | Exon 6 | |||||||

| MFN1 | NM_033540 | h MFN1 For | TGTTTTGGTCGCAAACTCTG | 160 | Exon 6 | 60 | 24.0–28.86 | y= 3.23 | 103.8 |

| h MFN1 Rev | CTGTCTGCGTACGTCTTCCA | Exon 7 / 8 | |||||||

| MFN2 | NM_014874 | h MFN2 For | ATGCATCCCCACTTAAGCAC | 301 | Exon 3 | 60 | 20.24–25.31 | y=−3.39 | 97 |

| h MFN2 Rev | CCAGAGGGCAGAACTTTGTC | Exon 5 | |||||||

| EIF4E | NM_001134651 | h EIF4e For | GCAGCAGATGATGAAGTAATAGGAGTT | 69 | Exon 5/6 | 60 | 25.86–29.87 | y =−3.32 | 100 |

| h eIF4e Rev | CCAGACTTGGACGACGTCTTCT | Exon 6 | |||||||

| RPS6KB1 | NM_003161 | h p70s6k For | GGACACTGGAGAAGTTCAAG | 276 | Exon 11/12 | 60 | 25.21–29.26 | y=−3.365 | 98.2 |

| h p70s6k Rev | CGGATTTTTGGTTCAAAGGA | Exon 14 | |||||||

| HDAC4 | NM_006037 | h HDAC4 For | CACAGACTCCGCGTGCAGCA | 94 | Exon 8/ 9 | 60 | 25.81–30.71 | y=−3.23 | 104 |

| h HDAC4 Rev | GGGCGCGATACCGTTCTCCG | Exon 9 | |||||||

| FBXO32 | NM_058229 | h Atrogin-1 For | GCAGCTGAACAACATTCAGATCAC | 97 | Exon 6 | 60 | 22.88–26.91 | y=−3.38 | 97.5 |

| h Atrogin-1 Rev | CAGCCTCTGCATGATGTTCAGT | Exon 7 | |||||||

| FOXO1 | NM_002015 | h FoXO1 For | AAGAGCGTGCCCTACTTCAA | 209 | Exon 1 | 60 | 23.79–28.98 | y=−3.45 | 94.6 |

| h FoXO1 Rev | CTGTTGTTGTCCATGGATGC | Exon 2 | |||||||

| FOXO3a | NM_001455 | h FoXO3a For | CTTCAAGGATAAGGGCGACA | 113 | Exon 2a/b | 60 | 25.88–31.08 | y=−3.39 | 97.4 |

| NM_013235 | h FoXO3a rev | TCTTGCCAGTTCCCTCATT | Exon 3 |

Table 2.

miRNA probe sequence and assay number

| MicroRNA | Sequence | Assay ID |

|---|---|---|

| miR-1 | UGGAAUGUAAAGAAGUAUGUAU | 002222 |

| miR-23a | AUCACAUUGCCAGGGAUUUCC | 000399 |

| miR-23b | AUCACAUUGCCAGGGAUUACC | 000400 |

| miR-29a | UAGCACCAUCUGAAAUCGGUUA | 002112 |

| miR-29b | UAGCACCAUUUGAAAUCAGUGUU | 000413 |

| miR-29c | UAGCACCAUUUGAAAUCGGUUA | 000587 |

| miR-31 | AGGCAAGAUGCUGGCAUAGCU | 002279 |

| miR-133a | UUUGGUCCCCUUCAACCAGCUG | 002246 |

| miR-133b | UUUGGUCCCCUUCAACCAGCUA | 002247 |

| miR-181a | AACAUUCAACGCUGUCGGUGAGU | 000480 |

| miR-206 | UGGAAUGUAAGGAAGUGUGUGG | 000510 |

| miR-455 | UAUGUGCCUUUGGACUACAUCG | 001280 |

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Frozen muscle (50 mg) was freeze-dried and dissected free of blood and connective tissue. Skeletal muscle protein was extracted in ice-cold buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.8, 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 10 mm NaF, 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 5 mm Na4O7P2, 1 mm benzamidine, 1 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin, and 1 μm microcystin). Homogenates were rotated for 60 min at 4°C and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and protein concentration of the resulting supernatant was determined using a commercial kit (Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Aliquots of muscle lysate were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer, and 40 μg of total protein/sample were separated by SDS–PAGE electrophoresis. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). For the measurement of eIF4e, p70s6k and HDAC4 proteins the membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (TBST) containing 7.5% non-fat dried milk for 1–2 h at room temperature, washed 3× with TBST for 10 min, and then incubated at 4°C overnight with the following primary antibodies diluted in 1% BSA in TBS: eIF4e 1:1000 (Cell Signalling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA, USA, no. 9742), p70s6k 1:1000 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; SC-230) and HDAC4 1:1000 (Cell Signalling Technology, Inc., Beverly, USA, no. 2072). Blots were normalised against the GAPDH protein (Santa Cruz no. sc 25778; 1:2000). Immunoreactive proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Standard ECL, GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) and quantified by densitometric scanning.

For the measurement of NRF1, MNF1, MFN2, Atrogin-1, FoxO1 and FoxO3 proteins, electrophoresis was performed using a 4–12% NuPAGE® Novex Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen) in NuPAGE® SDS Mops Running Buffer (Invitrogen). Protein transfer was performed in a Bjerrum buffer containing 50 mm Tris, 17 mm glycine and 10% methanol using PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS, after which they were incubated at 4°C with the following primary antibodies diluted in 3% BSA in PBS: atrogin-1 (Lot-1; ECM Biosciences, Versailles, USA); FoxO3 (FKHRL1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, no. sc-11351); FoxO1 (Cell Signalling Technology, Inc., no. 2880); NRF1 (Rockland Immunochemicals Inc. Gilbertsville, PA, USA); MFN-1 and MFN-2 (Abnova GmBH, Heidelberg, Germany). Primary antibodies were diluted 1:500 except for atrogin-1 and NRF1, which were diluted 1:1000. Following overnight or 1 h incubation (NRF1), the membranes were washed and incubated for 1 h with a goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody labelled with an infrared-fluorescent 800 nm dye (Alexa Fluor® 800, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) diluted 1:5000 in PBS containing 50% Odyssey® blocking buffer (LI-COR Biosciences) and 0.01% SDS. Membranes exposed to the anti-MFN-1 and MFN-2 antibodies were incubated for 1 h with a goat anti-mouse IgG antibody labelled with an infrared-fluorescent 680 nm dye (Alexa Fluor® 680, Invitrogen) diluted 1:5000 in PBS containing 50% Odyssey® blocking buffer (LI-COR Biosciences) and 0.01% SDS. After washing, proteins were exposed on an Odyssey® Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) and individual protein band optical densities were determined using the Odyssey® Infrared Imaging System software. Blots were normalised against the GAPDH protein (Santa Cruz no. sc-25778; 1:2000) which remained stable following the single bout and training periods (P= 0.82). In Fig. 5 the black vertical lines in the densitometry images indicate where one earlier time point between the Pre and Post 3 hrs time points was removed from the blot. This time point was not analysed for other targets due to a lack of tissue and removed from these blots for consistency with the other results. All samples for each subject were run on the same gel.

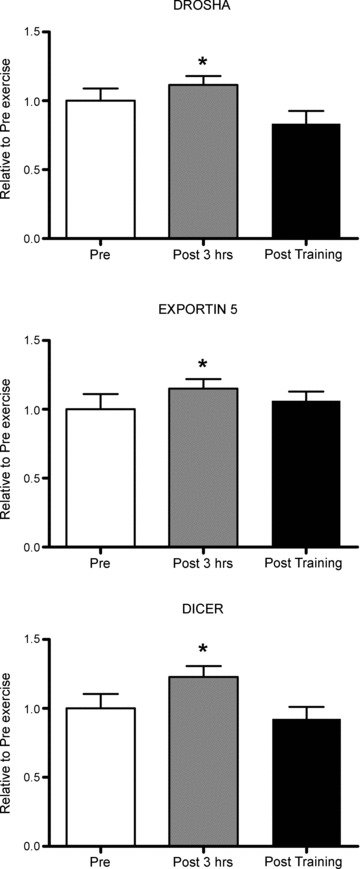

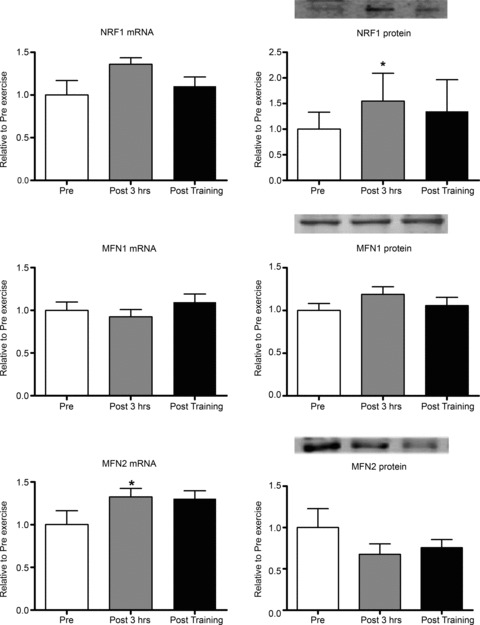

Figure 5. Regulation of targets involved in protein synthesis and transcriptional regulation following a single bout of moderate-intensity endurance exercise and short-term training.

Pre, sample taken before the acute exercise bout; Post 3 hrs, sample taken 3 h after the acute exercise bout; Post training, sample taken 2 days after the 10 day training programme. *Significantly different from other groups, P < 0.05; **significantly different from other groups, P < 0.01. The black vertical lines in the densitometry images indicate where one earlier time point between the pre and Post 3 hrs time points was removed from the blot. This time point was not analysed for other targets due to a lack of tissue and removed from these blots for consistency with the other results. All samples for each subject were run on the same gel. n= 9 subjects per group with data presented as means ± SEM.

Prediction of miRNA targets

For miRNAs that were regulated following acute endurance exercise, we predicted the potential mRNA/protein targets based on 3′UTR sequence homology using miRWalk (Dweep et al. 2011). The miRWalk program enables the prediction of miRNA targets by incorporating several known prediction software programs. miRanda, miRDB, miRWalk, RNA22 and Targetscan were chosen within the miRWalk program.

Reporter assay experiments

Human HDAC4 and NRF1 200–300 bp 3′UTRs, including the putative miR-31 binding sites, were amplified from human cDNA by PCR using Ex Taq HS (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan). The amplified fragment was cloned downstream of luciferase under the SV40 promoter using the XbaI (HDAC4) or EcoRI (NRF1) of the pLuc2EXN plasmid (pLuc2-HDAC4; pLuc-NRF1. Primer sequences for amplifying the HDAC4 3′UTR were: Forward 5′ AAT CTAGATGTTGCTGTCAGATTCTATTTTCAG 3′; Reverse 5′ AATCTAGATGACTGTCAGTTACTGTTGAAGAGA 3′. Primer sequences for amplifying the NRF1 3′UTR were: Forward 5′ GTGGAAACAATAATTCACCCAGTT 3′; Reverse 5′ ATCCTGGTCTAGGACGATTTTTC 3′. For overexpression of miR-31, pCXbG-miR-31 was generated by amplifying miR-31 from human genomic DNA by PCR using following primers: 5′ AAAGTCGA CCCTCCCTCAGGTGAAAGGAA and 3′ AAGATATC TCGAGAAGGGCGCACATACACAG. The PCR product was digested with SalI and EcoRV and introduced into the pCXbG plasmid at the XhoI and EcoRV sites. Reporter assay was performed as described (Wada et al. 2011; Russell et al. 2012). Briefly, C2C12 myoblasts (ATCC) were seeded in 6-well plates 18 h before transfection. Cells were transfected with 0.2 ug pLuc2EXN, pLuc2EXN-HDAC4 3′UTR or pLuc2EXN-NRF1 3′UTR, 0.2 ug of pRL-Tk (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and 0.6 ug of pCXbG-miR-31 or pCXbG-sΔ (mock vector) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were lysed 24 h after transfection and luciferase activity was measured using the dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega Co). Firefly luciferase activity was normalised to Renilla luciferase activity.

Statistics

A one-way analysis of variance with repeated measures was used to determine the effect of acute exercise and short-term training on the dependent variables. Significance was set at P < 0.05. A post hoc analysis was performed using multiple t tests with the Bonferroni adjustment. Linear regression was performed to establish the correlation between miRNAs and their predicted protein targets pre exercise, following acute exercise and following short-term training.

Results

Following 7 days of endurance training, mean (± SEM)  increased by 10% from 44.1 ± 7.2 to 48.5 ± 5.3 ml kg−1 min−1. Peak power output (PPO) increased by 15% from 248 ± 41 to 286 ± 31 W, as reported previously (P < 0.05; Benziane et al. 2008).

increased by 10% from 44.1 ± 7.2 to 48.5 ± 5.3 ml kg−1 min−1. Peak power output (PPO) increased by 15% from 248 ± 41 to 286 ± 31 W, as reported previously (P < 0.05; Benziane et al. 2008).

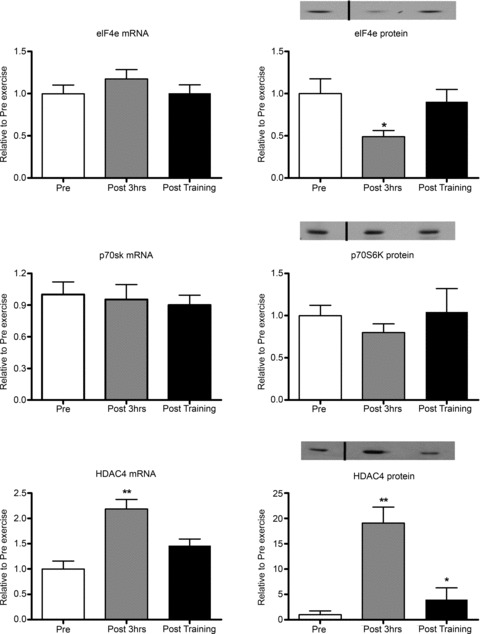

Following 60 min of acute endurance exercise, mRNA expression levels of several key members of the miRNA processing complex, Drosha, Dicer and Exportin-5, were significantly upregulated by 35, 35 and 30%, respectively, during the first 3 h post exercise. Short-term endurance training did not affect the expression of these genes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Components of the miRNA biogenesis machinery are regulated by a single bout of moderate-intensity endurance exercise.

Pre, sample taken before the acute exercise bout; Post 3 hrs, sample taken 3 h after the acute exercise bout; Post training, sample taken 2 days after the 10 day training programme. *Significantly different from other groups, P < 0.05, n= 9 subjects per group with data presented as means ± SEM.

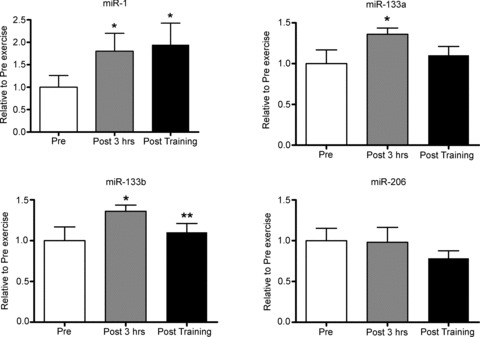

The myomiRs miR-1, miR-133a and miR-133b, but not miR-206, were significantly increased by 60%, 35% and 40% following acute endurance exercise (Fig. 2). Only miR-1 levels remained elevated following short-term endurance training (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Influence of a single bout of moderate-intensity endurance exercise and short-term training on muscle-enriched miRNAs.

Pre, sample taken before the acute exercise bout; Post 3 hrs, sample taken 3 h after the acute exercise bout; Post training, sample taken 2 days after the 10 day training programme. *Significantly different from Pre, P < 0.05; **significantly different from the Pre 3 h time point, P < 0.01, n= 9 subjects per group with data presented as means ± SEM.

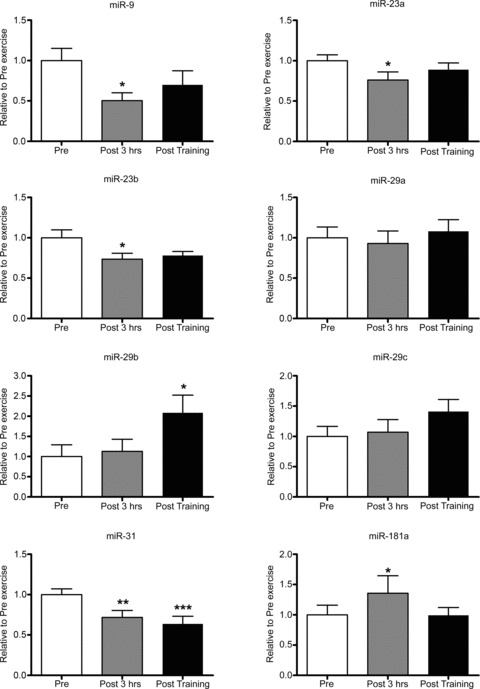

Several other miRNA species, previously shown to be dysregulated in muscle wasting and chronic disease conditions were also investigated. Acute endurance exercise reduced miR-9, -23a, -23b and -31 by 50%, 24%, 27% and 28%, respectively. miR-181 was significantly increased by 35%, with no change observed for miR-29a, -29b and -29c (Fig. 3). Short-term training increased miR-29b by 210% and decreased in miR-31 by 35% (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Influence of a single bout of moderate-intensity endurance exercise and short-term training on miRNAs known to be dysregulated in myopathies and neuromuscular disorders.

Pre, sample taken before the acute exercise bout; Post 3 hrs, sample taken 3 h after the acute exercise bout; Post training, sample taken 2 days after the 10 day training programme. *Significantly different from other groups, P < 0.05, n= 9 subjects per group with data presented as mean ± SEM; **significant different from pre, P < 0.01; ***significant different from pre, P < 0.001.

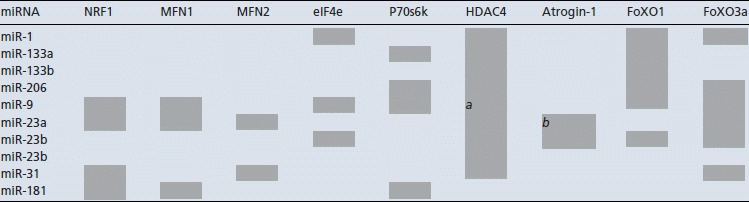

As miRNAs can regulate multiple genes, and a gene can be regulated by multiple miRNAs, (Lewis et al. 2003) we used the miRWALK prediction tool to identify potential mRNA/protein targets (http://www.ma.uni-heidelberg.de/apps/zmf/mirwalk). The miRNAs that were regulated by an acute bout of endurance cycling exercise were screened using miRWALK to predict their potential gene targets. As miRNAs can regulate both mRNA and protein, mRNA and protein levels of several of these targets were measured. The targets selected were identified by at least two or more of the five prediction software programs used within the miRWalk program for an individual miRNA. Finally, the predicted targets selected for mRNA and protein analysis were those that have been shown to be regulated by exercise and which are known to influence mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism, including NRF1 (Short et al. 2003; Kelly & Scarpulla, 2004), mitofusin-1 (MFN1) and MFN2 (Bach et al. 2003; Cartoni et al. 2005), as well as targets regulating muscle growth such as eIF4e (Koshiba et al. 2004), p70s6K (Camera et al. 2010), HDAC4 (McGee et al. 2009), atrogin-1/MAFbx, FoXO1 and FoXO3a (Russell et al. 2005; Louis et al. 2007). Table 3 shows the predicted targets for each miRNA.

Table 3.

Predicted miRNA targets using miRWalk

|

Grey shaded box depicts a possible target. a, Roccaro et al. (2010); b, Wada et al. (2011); previously validated targets.

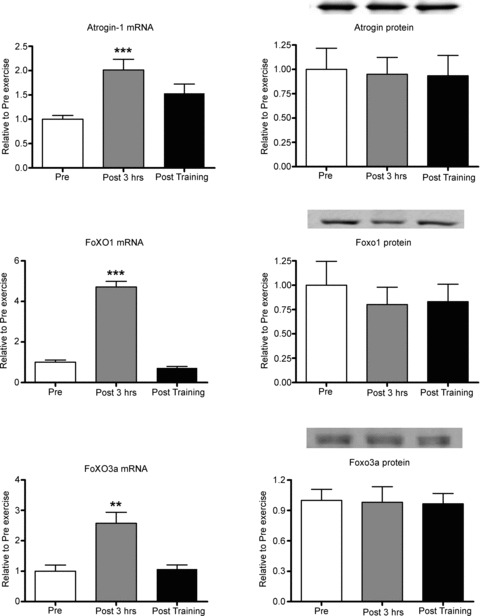

Following acute exercise, NRF1 protein, but not mRNA, was increased by 54%. MFN2 mRNA, but not protein, was increased by 32%, while MFN1 mRNA and protein levels were unaltered (Fig. 4). A significant 50% reduction in eIF4e protein levels, with no changes in its mRNA levels was observed. p70s6K mRNA and protein was unaltered (Fig. 5). HDAC4 mRNA and protein were increased by 2- and 19-fold, respectively. Post training, HDAC4 protein remained elevated 4-fold above pre-training levels, but was lower than the increase observed 3 h post the acute exercise bout (Fig. 5). Following acute exercise Atrogin-1/MAFbx, FoXO1 and FoXO3a mRNA levels increased by 1.0-, 4.7- and 2.4-fold, respectively, without any changes observed in their protein levels. Short term training did not affect atrogin-1/MAFbx, FoXO1 and FoXO3a mRNA or protein levels (Fig. 6).

Figure 4. Regulation of targets involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and function following a single bout of moderate-intensity endurance exercise and short-term training.

Pre, sample taken before the acute exercise bout; Post 3 hrs, sample taken 3 h after the acute exercise bout; Post training, sample taken 2 days after the 10 day training programme. *Significantly different from other groups, P < 0.05, n= 9 subjects per group with data presented as means ± SEM.

Figure 6. Regulation of targets involved in protein breakdown following a single bout of moderate-intensity endurance exercise and short-term training.

Pre, sample taken before the acute exercise bout; Post 3 hrs, sample taken 3 h after the acute exercise bout; Post training, sample taken 2 days after the 10 day training programme. **Significantly different from the other groups, P < 0.001; ***significantly different from other groups, P < 0.001. Only 8 of the 9 subjects are represented due to insufficient sample remaining for 1 subject. Data presented as means ± SEM.

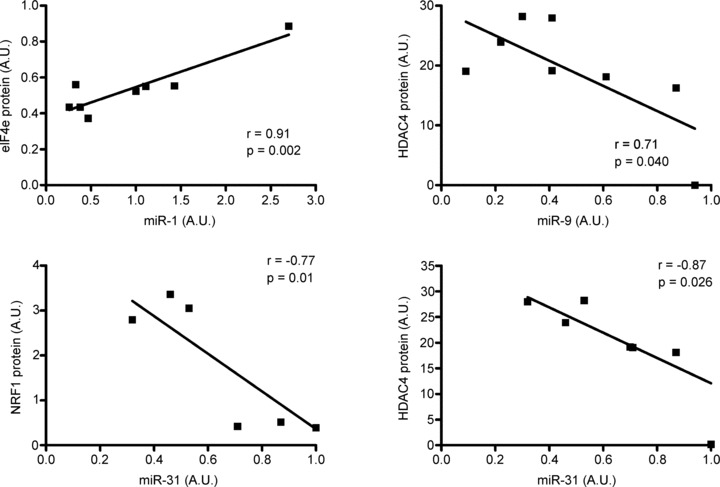

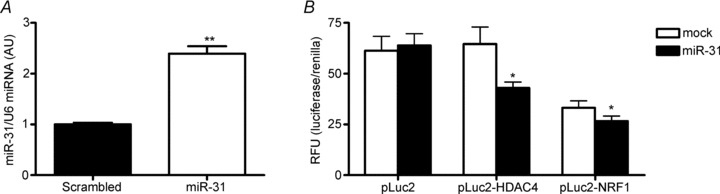

The correlations between miRNA species and their predicted protein targets were only observed following the single bout of moderate-intensity exercise (Fig. 7). Based on the predicted miRNA/protein targets listed in Table 3, inverse correlations were observed between miR-9 and HDAC4 protein (r =−0.71; P= 0.04), miR-31 and HDAC4 protein (r =−0.87; P= 0.026) and miR-31 and NRF1 protein (r =−0.77; P= 0.01). Whether these correlations could have a potential cause and effect was of interest to establish. Since miR-9 regulates HDAC4 (Roccaro et al. 2010), we performed a luciferase reporter assay in C2C12 myotubes to determine if miR-31 can regulate HDAC4 and NRF1 in vitro. The luciferase reporter assay showed a 30% and 18% reduction in luciferase/renilla activity for HDAC4 and NRF1 respectively (Fig. 8). Transfection of the miR-31 expression plasmid increased miR-31 miRNA levels by 2.2-fold in the C2C12 cells (Fig. 8); however, did this not affect either HDAC4 or NRF1 mRNA or protein (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 7. Correlation analysis between miRNAs and predicted protein targets 3 h following the single bout of moderate-intensity endurance exercise.

Only 8 of the 9 subjects are represented in these correlations due to insufficient sample remaining for 1 subject. Data presented as means ± SEM.

Figure 8. Luciferase reporter assay to test the relationship between miR-31 and HDAC4 and miR-31 and NRF1in C2C12 myoblasts.

N= 3 independent experiments with 3 replicates per experiment. pLuc2, empty luciferase control vector; p Luc2-HDAC4, luciferase vector contacting the HDAC4 3-UTR; p Luc2-NRF1, luciferase vector contacting the NRF1 3-UTR; mock, control miRNA.

Correlations were also made between  , PPO and the miRNAs, mRNAs and proteins measured. Pre-training

, PPO and the miRNAs, mRNAs and proteins measured. Pre-training  , positively correlated with miR-181 (r = 0.70; P= 0.03) while pre-training PPO was inversely correlated with miR-23a (r =−0.79; P= 0.012). Post-training PPO was negatively correlated with miR-31 (r =−0.74; P= 0.042). No other correlations were observed.

, positively correlated with miR-181 (r = 0.70; P= 0.03) while pre-training PPO was inversely correlated with miR-23a (r =−0.79; P= 0.012). Post-training PPO was negatively correlated with miR-31 (r =−0.74; P= 0.042). No other correlations were observed.

Discussion

Skeletal muscle miRNAs are responsive to skeletal muscle contractile activity and disuse and play a key role in muscle adaptation/maladaptation. Endurance exercise is a key intervention used to maintain skeletal muscle health and prevent chronic disease. The present study provides evidence that in the 3 h period following an acute bout of endurance cycling exercise in untrained men, gene expression of components of the miRNA biogenesis pathway were elevated, as were several muscle enriched miRNAs including miR-1, -133a and 133-b, as well as miR-181a. miR-9, -23a, -23b and -31 were decreased following acute exercise. Short-term training increased miR-1 and miR-29b, while miR-31 remained decreased.

miRNA biogenesis is a complex process requiring co-ordination of pri-miRNA transcription, and its cleavage by endonucleases, exportation from nucleus to cytoplasm, additional cleavage and then incorporation into the RISC complex (Bartel, 2004). Acute endurance exercise in untrained males increases mRNA for two key endonuclease III enyzmes, Drosha and Dicer, as well as the miRNA export protein, Exportin-5, 3 h post exercise. Following acute resistance exercise in healthy men Exportin-5 increases at 3 h post exercise (Drummond et al. 2008). Exportin-5 exports pre-miRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, and thus its upregulation following exercise most likely assists in the processing of new pre-miRNAs required for exercise-induced adaptations. Exportin-5 also mediates nuclear export of unspliced mRNA, suggesting a novel gene-regulatory mechanism involving Exportin-5 (Lund & Dahlberg, 2006). Mechanisms regulating the miRNA biogenesis machinery following exercise in skeletal muscle are unknown and this should be a focus for future investigation.

In our study, the myomiRs, miR-1, -133a and -133b, but not -206, were increased 3 h post exercise. In another study, the same myomiRs increased 1 h post endurance cycling, but returned to pre-exercise levels when measured 4 h post exercise (Nielsen et al. 2010). The major difference between the studies is that the subjects in the present study were considerably less trained, with  and PPO approximately 20% and 30% lower, respectively, than in the earlier report (Nielsen et al. 2010). While exercise intensity and durations were similar between studies, subjects in the present study may have had more muscular stress due to lack of familiarity with cycling exercise. This may account for the prolonged response of the miRNAs measured here. Of the myomiRs measured, only miR-1 remained elevated following 10 days of training. However, it has been observed that after 6 weeks of moderate-intensity endurance training miR-1 and -133a are reduced (Keller et al. 2011) and after 12 weeks of high-intensity endurance training, miR-1, -133a, -133b, and -206 are reduced (Nielsen et al. 2010). The differences between studies may arise from the training status of the subjects and the duration of the training period or may be a reflection of temporal changes in muscle adaptations that occur with endurance exercise training. The effect of the acute upregulation of these myomiRs following an endurance exercise bout is unknown. miR-1 and -206 increase muscle cell differentiation and inhibit proliferation, while miR-133a/b has the opposite effect (Chen et al. 2006; van Rooij et al. 2008). Acute endurance cycling exercise increases myogenin (Kadi et al. 2004), a positive regulator of myogenesis. Additionally, endurance training remodels skeletal muscle as an adaptive response to enhance metabolic, mitochondrial and contractile function and to repair damage to myofibres (Seene et al. 2009; Egan et al. 2011). The regulation of these miRNAs should play a positive role in regulating skeletal muscle myogenesis as the muscle adapts to the stress of exercise.

and PPO approximately 20% and 30% lower, respectively, than in the earlier report (Nielsen et al. 2010). While exercise intensity and durations were similar between studies, subjects in the present study may have had more muscular stress due to lack of familiarity with cycling exercise. This may account for the prolonged response of the miRNAs measured here. Of the myomiRs measured, only miR-1 remained elevated following 10 days of training. However, it has been observed that after 6 weeks of moderate-intensity endurance training miR-1 and -133a are reduced (Keller et al. 2011) and after 12 weeks of high-intensity endurance training, miR-1, -133a, -133b, and -206 are reduced (Nielsen et al. 2010). The differences between studies may arise from the training status of the subjects and the duration of the training period or may be a reflection of temporal changes in muscle adaptations that occur with endurance exercise training. The effect of the acute upregulation of these myomiRs following an endurance exercise bout is unknown. miR-1 and -206 increase muscle cell differentiation and inhibit proliferation, while miR-133a/b has the opposite effect (Chen et al. 2006; van Rooij et al. 2008). Acute endurance cycling exercise increases myogenin (Kadi et al. 2004), a positive regulator of myogenesis. Additionally, endurance training remodels skeletal muscle as an adaptive response to enhance metabolic, mitochondrial and contractile function and to repair damage to myofibres (Seene et al. 2009; Egan et al. 2011). The regulation of these miRNAs should play a positive role in regulating skeletal muscle myogenesis as the muscle adapts to the stress of exercise.

miR-9, -23, -29, -31 and -181 are dysregulated in skeletal muscle of patients with various neuromuscular disorders and dystrophies (Wang et al. 2008; Eisenberg et al. 2009; Greco et al. 2009; Russell et al. 2012). Following acute endurance exercise miR-9, -23a, -23b, and -31 were downregulated, with lower miR-31 levels following 10 days of training. In contrast miR-181 and miR-29b were elevated after acute exercise. The genes targeted by these miRNAs in skeletal muscle following acute endurance exercise are unknown. miR-9 regulates Sirt1 in pancreatic β-cells with a reduction in miR-9 resulting in an increase in Sirt1 (Ramachandran et al. 2011). Endurance exercise increases Sirt1 (Dumke et al. 2009). Whether this exercise-induced adaptation requires the reduction in miR-9 is unknown.

Loss-of-function/gain-of-function studies in prolife-rating vascular smooth muscle cells confirm that increases in miR-31 have a positive effect on proliferation (Liu et al. 2011). miR-31 is increased in regenerating muscle (Greco et al. 2009) and in muscle samples from patients with diseases such as ALS, neurogenic disease and Duchene muscular dystrophy (Greco et al. 2009; Russell et al. 2012). This increase in miR-31 may be an attempt to regenerate and delay skeletal muscle atrophy in these conditions. As acute endurance exercise increases muscle cell proliferative capacity (Choi et al. 2005), the decrease in miR-31 after acute endurance exercise reported here suggests that miR-31 may not play a role in regeneration of muscle cells, if this process was active. We also observed an increase in miR181a, supporting observations in mice following treadmill running (Safdar et al. 2009). miR-181 is suggested to inhibit Hox-A11 expression; the latter a repressor of MyoD (Naguibneva et al. 2006). The role of miR-181a in skeletal muscle following endurance exercise is unknown; however, it may promote skeletal muscle remodelling by negatively regulating repressors of myogenesis (Safdar et al. 2009). The only other non-myomiR that was increased post endurance exercise was miR-29b. miR-29b levels are increased during human myotube differentiation and in regenerating mouse muscle (Wang et al. 2008). Rescuing miR-29 in myoblasts isolated from muscles of mice with chronic kidney disease improves differentiation into myotubes (Wang et al. 2011). The upregulation of both miR181a and miR-29b in muscle following endurance exercise may be a response to assist with muscle repair, regeneration and remodelling. It is worth noting that after 6 weeks of moderate-intensity endurance training miR-29b, as well as a suite of other miRNAs, was downregulated (Keller et al. 2011), further suggesting that a temporal regulation, at least for miR-29b, may be a reflection of different adaptations controlled by miRNAs.

A causal relationship between the regulation of miRNAs and potential protein targets in human skeletal muscle following exercise is beyond the scope of the present study. However, the use of bioinformatics to predict potential targets of miRNAs, combined with linear regression analysis, provides correlational evidence for potential regulation. Within the limitations associated with prediction tools and correlational assessment, the exercise-induced regulation of HDAC4 proteins may involve miR-9 and miR-31, while the regulation of the NRF1 protein may involve miR-31. In support of this prediction, the miR-9 regulation of HDAC4 has been validated in Waldenström macroglobulinemia cells (Roccaro et al. 2010). Using a reporter assay, we were unable to validate a direct relationship between miR-31 and HDAC4 or miR-31 and NRF1 in vitro. This negative in vitro result obtained under non-physiological conditions, does not exclude the possibility that such interactions are possible in human skeletal muscle following endurance exercise.

The expression levels of several miRNA species are sensitive to muscle contraction stimulated by endurance exercise. However, the exact stress signals initiating these changes in miRNA expression are unknown. During exercise, numerous stress signals are initiated by changes in motor nerve activation and calcium concentrations, mechanical and contractile stress, increased muscle blood flow and shear stress, hormonal and metabolic stress, which activate intracellular signalling pathways controlling skeletal muscle gene transcription and translation (Bassel-Duby & Olson, 2006; Koulmann & Bigard, 2006; Favier et al. 2008; Russell, 2010). Identification of the primary stressor/s activated by endurance exercise that regulate miRNA expression should be investigated in the future.

In conclusion, the stress associated with a single bout of moderate intensity cycling, performed by untrained males, causes an increase in muscle-enriched miRNAs, including miR-1, -133a and 133-b, as well as miR-181a. It also decreases miR-9, -23a, -23b and -31; species upregulated in several muscle wasting disorders. miR-1 remained elevated, while miR-29b and -31 remaining decreased, following short-term training of 10 days. miRNAs play important roles in human health and their rapid, yet transient regulation with endurance exercise suggests that they contribute to the positive adaptations of endurance exercise. Identifying the exercise-mediated intracellular stress signals regulating miRNAs will be an important progression in our understanding of their potential role/s in human health.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr B. Scanlan, Mr T. Burton and A/Prof B. Canny for technical assistance in participant testing, training and tissue sampling.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

A.P.R. was responsible for the development of the project, data analysis, interpretation and prepared the manuscript. S.L. and H.B. performed and analysed Western blotting; S.W. and T.A. completed the in vitro miRNA, mRNA and protein analysis; I.G. and E.L.B. performed the bioinformatics and miRNA analysis; A.V.C., J.R.Z., R.J.S., N.S. were involved in the development of the project; G.D.W. completed gene expression analysis and assisted with the development of the project. All authors were responsible for revising the manuscript throughout the review process.

Funding

This study was supported with funding from the European Research Council Advanced Grant Ideas Program, the Swedish Research Council, the Novo Nordisk Foundation and The Strategic Diabetes Program at Karolinska Institutet. S.L. is supported by an Alfred Deakin postdoctoral fellowship from Deakin University. N.K.S. is supported by the Australian Government Collaborative Research Network scheme.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Fig. 1

References

- Aoi W, Naito Y, Mizushima K, Takanami Y, Kawai Y, Ichikawa H, Yoshikawa T. The microRNA miR-696 regulates PGC1alpha in mouse skeletal muscle in response to physical activity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E799–E806. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00448.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach D, Pich S, Soriano FX, Vega N, Baumgartner B, Oriola J, Daugaard JR, Lloberas J, Camps M, Zierath JR, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Wallberg-Henriksson H, Laville M, Palacin M, Vidal H, Rivera F, Brand M, Zorzano A. Mitofusin-2 determines mitochondrial network architecture and mitochondrial metabolism. A novel regulatory mechanism altered in obesity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17190–17197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres R, Yan J, Egan B, Treebak JT, Rasmussen M, Fritz T, Caidahl K, Krook A, O’Gorman DJ, Zierath JR. Acute exercise remodels promoter methylation in human skeletal muscle. Cell Metabolism. 2012;15:405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Signaling pathways in skeletal muscle remodeling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:19–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benziane B, Burton TJ, Scanlan B, Galuska D, Canny BJ, Chibalin AV, Zierath JR, Stepto NK. Divergent cell signaling after short-term intensified endurance training in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1427–E1438. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90428.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callis TE, Deng Z, Chen JF, Wang DZ. Muscling through the microRNA world. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:131–138. doi: 10.3181/0709-MR-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camera DM, Edge J, Short MJ, Hawley JA, Coffey VG. Early time-course of Akt phosphorylation following endurance and resistance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1843–1852. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181d964e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannata DJ, Ireland Z, Dickinson H, Snow RJ, Russell AP, West JM, Walker DW. Maternal creatine supplementation from mid-pregnancy protects the newborn spiny mouse diaphragm from intrapartum hypoxia-induced damage. Pediatr Res. 2010;68:393–398. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181f1c048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartoni R, Leger B, Hock MB, Praz M, Crettenand A, Pich S, Ziltener JL, Luthi F, Deriaz O, Zorzano A, Gobelet C, Kralli A, Russell AP. Mitofusins 1/2 and ERRalpha expression are increased in human skeletal muscle after physical exercise. J Physiol. 2005;567:349–358. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang DZ. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2006;38:228–233. doi: 10.1038/ng1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Liu X, Li P, Akimoto T, Lee SY, Zhang M, Yan Z. Transcriptional profiling in mouse skeletal muscle following a single bout of voluntary running: evidence of increased cell proliferation. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:2406–2415. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00545.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dela F, Ploug T, Handberg A, Petersen LN, Larsen JJ, Mikines KJ, Galbo H. Physical training increases muscle GLUT4 protein and mRNA in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes. 1994;43:862–865. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.7.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond MJ, McCarthy JJ, Fry CS, Esser KA, Rasmussen BB. Aging differentially affects human skeletal muscle microRNA expression at rest and after an anabolic stimulus of resistance exercise and essential amino acids. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1333–E1340. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90562.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumke CL, Mark Davis J, Angela Murphy E, Nieman DC, Carmichael MD, Quindry JC, Travis Triplett N, Utter AC, Gross Gowin SJ, Henson DA, McAnulty SR, McAnulty LS. Successive bouts of cycling stimulates genes associated with mitochondrial biogenesis. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:419–427. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dweep H, Sticht C, Pandey P, Gretz N. miRWalk–database: prediction of possible miRNA binding sites by “walking” the genes of three genomes. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44:839–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan B, Dowling P, O’Connor PL, Henry M, Meleady P, Zierath JR, O’Gorman DJ. 2-D DIGE analysis of the mitochondrial proteome from human skeletal muscle reveals time course-dependent remodelling in response to 14 consecutive days of endurance exercise training. Proteomics. 2011;11:1413–1428. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg I, Alexander MS, Kunkel LM. miRNAS in normal and diseased skeletal muscle. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favier FB, Benoit H, Freyssenet D. Cellular and molecular events controlling skeletal muscle mass in response to altered use. Pflugers Arch. 2008;456:587–600. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0423-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambardella S, Rinaldi F, Lepore SM, Viola A, Loro E, Angelini C, Vergani L, Novelli G, Botta A. Overexpression of microRNA-206 in the skeletal muscle from myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients. J Transl Med. 2010;8:48. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco S, De Simone M, Colussi C, Zaccagnini G, Fasanaro P, Pescatori M, Cardani R, Perbellini R, Isaia E, Sale P, Meola G, Capogrossi MC, Gaetano C, Martelli F. Common micro-RNA signature in skeletal muscle damage and regeneration induced by Duchenne muscular dystrophy and acute ischemia. FASEB J. 2009;23:3335–3346. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AJ, Baulcombe DC. A species of small antisense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science. 1999;286:950–952. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadi F, Johansson F, Johansson R, Sjostrom M, Henriksson J. Effects of one bout of endurance exercise on the expression of myogenin in human quadriceps muscle. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;121:329–334. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0630-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Steensberg A, Pilegaard H, Osada T, Saltin B, Pedersen BK, Neufer PD. Transcriptional activation of the IL-6 gene in human contracting skeletal muscle: influence of muscle glycogen content. FASEB J. 2001;15:2748–2750. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0507fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller P, Vollaard NB, Gustafsson T, Gallagher IJ, Sundberg CJ, Rankinen T, Britton SL, Bouchard C, Koch LG, Timmons JA. A transcriptional map of the impact of endurance exercise training on skeletal muscle phenotype. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110:46–59. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00634.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DP, Scarpulla RC. Transcriptional regulatory circuits controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Genes Dev. 2004;18:357–368. doi: 10.1101/gad.1177604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Lee YS, Sivaprasad U, Malhotra A, Dutta A. Muscle-specific microRNA miR-206 promotes muscle differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:677–687. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiba T, Detmer SA, Kaiser JT, Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC. Structural basis of mitochondrial tethering by mitofusin complexes. Science. 2004;305:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1099793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulmann N, Bigard AX. Interaction between signalling pathways involved in skeletal muscle responses to endurance exercise. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452:125–139. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-0030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamon S, Wallace MA, Leger B, Russell AP. Regulation of STARS and its downstream targets suggest a novel pathway involved in human skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. J Physiol. 2009;587:1795–1803. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.168674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Ajay SS, Yook JI, Kim HS, Hong SH, Kim NH, Dhanasekaran SM, Chinnaiyan AM, Athey BD. New class of microRNA targets containing simultaneous 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR interaction sites. Genome Res. 2009;19:1175–1183. doi: 10.1101/gr.089367.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Radmark O, Kim S, Kim VN. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A, Riddoch-Contreras J, Natanek SA, Donaldson A, Man WD, Moxham J, Hopkinson NS, Polkey MI, Kemp PR. Downregulation of the serum response factor/miR-1 axis in the quadriceps of patients with COPD. Thorax. 2012;67:26–34. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Olson EN. MicroRNA regulatory networks in cardiovascular development. Dev Cell. 2010;18:510–525. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Williams AH, Kim Y, McAnally J, Bezprozvannaya S, Sutherland LB, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. An intragenic MEF2-dependent enhancer directs muscle-specific expression of microRNAs 1 and 133. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20844–20849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710558105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Cheng Y, Chen X, Yang J, Xu L, Zhang C. MicroRNA-31 regulated by the extracellular regulated kinase is involved in vascular smooth muscle cell growth via large tumor suppressor homolog 2. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42371–42380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.261065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis E, Raue U, Yang Y, Jemiolo B, Trappe S. Time course of proteolytic, cytokine, and myostatin gene expression after acute exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1744–1751. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00679.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E, Dahlberg JE. Substrate selectivity of exportin 5 and Dicer in the biogenesis of microRNAs. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:59–66. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E, Guttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, Kutay U. Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science. 2004;303:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JJ, Esser KA. MicroRNA-1 and microRNA-133a expression are decreased during skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:306–313. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00932.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JJ, Esser KA, Peterson CA, Dupont-Versteegden EE. Evidence of MyomiR network regulation of beta-myosin heavy chain gene expression during skeletal muscle atrophy. Physiol Genomics. 2009;39:219–226. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00042.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee SL, Fairlie E, Garnham AP, Hargreaves M. Exercise-induced histone modifications in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2009;587:5951–5958. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee SL, Sparling D, Olson AL, Hargreaves M. Exercise increases MEF2- and GEF DNA-binding activity in human skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2006;20:348–349. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4671fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguibneva I, Ameyar-Zazoua M, Polesskaya A, Ait-Si-Ali S, Groisman R, Souidi M, Cuvellier S, Harel-Bellan A. The microRNA miR-181 targets the homeobox protein Hox-A11 during mammalian myoblast differentiation. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:278–284. doi: 10.1038/ncb1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Takeoka M, Mori M, Hashimoto S, Sakurai A, Nose H, Higuchi K, Itano N, Shiohara M, Oh T, Taniguchi S. Exercise effects on methylation of ASC gene. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31:671–675. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1246140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Scheele C, Yfanti C, Akerstrom T, Nielsen AR, Pedersen BK, Laye MJ. Muscle specific microRNAs are regulated by endurance exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2010;588:4029–4037. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran D, Roy U, Garg S, Ghosh S, Pathak S, Kolthur-Seetharam U. Sirt1 and mir-9 expression is regulated during glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-islets. FEBS J. 2011;278:1167–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao PK, Kumar RM, Farkhondeh M, Baskerville S, Lodish HF. Myogenic factors that regulate expression of muscle-specific microRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8721–8726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602831103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringholm S, Bienso RS, Kiilerich K, Guadalupe-Grau A, Aachmann-Andersen NJ, Saltin B, Plomgaard P, Lundby C, Wojtaszewski JF, Calbet JA, Pilegaard H. Bed rest reduces metabolic protein content and abolishes exercise-induced mRNA responses in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E649–E658. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00230.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roccaro AM, Sacco A, Jia X, Azab AK, Maiso P, Ngo HT, Azab F, Runnels J, Quang P, Ghobrial IM. microRNA-dependent modulation of histone acetylation in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2010;116:1506–1514. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell AP. The molecular regulation of skeletal muscle mass. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37:378–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell AP, Feilchenfeldt J, Schreiber S, Praz M, Crettenand A, Gobelet C, Meier CA, Bell DR, Kralli A, Giacobino JP, Deriaz O. Endurance training in humans leads to fiber type-specific increases in levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha in skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2003;52:2874–2881. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell AP, Hesselink MK, Lo SK, Schrauwen P. Regulation of metabolic transcriptional co-activators and transcription factors with acute exercise. FASEB J. 2005;19:986–988. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3168fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell AP, Wada S, Vergani L, Hock BM, Lamon S, Légere B, Ushida T, Cartoni R, Wadley G, Hespel P, Kralli A, Soraru G, Angelini C, Akimoto T. Disruption of skeletal muscle mitochondrial network genes and miRNAs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;49C:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safdar A, Abadi A, Akhtar M, Hettinga BP, Tarnopolsky MA. miRNA in the regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation to acute endurance exercise in C57Bl/6J male mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seene T, Kaasik P, Umnova M. Structural rearrangements in contractile apparatus and resulting skeletal muscle remodelling: effect of exercise training. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2009;49:410–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short KR, Vittone JL, Bigelow ML, Proctor DN, Rizza RA, Coenen-Schimke JM, Nair KS. Impact of aerobic exercise training on age-related changes in insulin sensitivity and muscle oxidative capacity. Diabetes. 2003;52:1888–1896. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.8.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small EM, O’Rourke JR, Moresi V, Sutherland LB, McAnally J, Gerard RD, Richardson JA, Olson EN. Regulation of PI3-kinase/Akt signaling by muscle-enriched microRNA-486. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4218–4223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000300107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooij E, Liu N, Olson EN. MicroRNAs flex their muscles. Trends Genet. 2008;24:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooij E, Quiat D, Johnson BA, Sutherland LB, Qi X, Richardson JA, Kelm RJ, Jr, Olson EN. A family of microRNAs encoded by myosin genes governs myosin expression and muscle performance. Dev Cell. 2009;17:662–673. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada S, Kato Y, Okutsu M, Miyaki S, Suzuki K, Yan Z, Schiaffino S, Asahara H, Ushida T, Akimoto T. Translational suppression of atrophic regulators by miR-23a integrates resistance to skeletal muscle atrophy. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:38456–38465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.271270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadley GD, Konstantopoulos N, Macaulay L, Howlett KF, Garnham A, Hargreaves M, Cameron-Smith D. Increased insulin-stimulated Akt pSer473 and cytosolic SHP2 protein abundance in human skeletal muscle following acute exercise and short-term training. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:1624–1631. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00821.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Garzon R, Sun H, Ladner KJ, Singh R, Dahlman J, Cheng A, Hall BM, Qualman SJ, Chandler DS, Croce CM, Guttridge DC. NF-kappaB-YY1-miR-29 regulatory circuitry in skeletal myogenesis and rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XH, Hu Z, Klein JD, Zhang L, Fang F, Mitch WE. Decreased miR-29 suppresses myogenesis in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:2068–2076. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AH, Valdez G, Moresi V, Qi X, McAnally J, Elliott JL, Bassel-Duby R, Sanes JR, Olson EN. MicroRNA-206 delays ALS progression and promotes regeneration of neuromuscular synapses in mice. Science. 2009;326:1549–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.1181046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Creer A, Jemiolo B, Trappe S. Time course of myogenic and metabolic gene expression in response to acute exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1745–1752. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01185.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.