Abstract

Recent studies have highlighted the involvement of the palatine tonsils in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, particularly among patients with recurrent throat infections. However, the underlying immunological mechanism is not well understood. In this study we confirm that psoriasis tonsils are infected more frequently by β-haemolytic Streptococci, in particular Group C Streptococcus, compared with recurrently infected tonsils from patients without skin disease. Moreover, we show that tonsils from psoriasis patients contained smaller lymphoid follicles that occupied a smaller tissue area, had a lower germinal centre to marginal zone area ratio and contained fewer tingible body macrophages per unit area compared with recurrently infected tonsils from individuals without skin disease. Psoriasis patients' tonsils had a higher frequency of skin-homing [cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA+)] CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and this correlated significantly with their frequency of blood CLA+ T cells. The psoriasis patients also had a higher frequency of tonsil T cells expressing the interleukin (IL)-23 receptor that was expressed preferentially by the CLA+ T cell population. In contrast, recurrently infected tonsils of individuals without skin disease had a higher frequency of tonsil T cells expressing the activation marker CD69 and a number of chemokine receptors with unknown relevance to psoriasis. These findings suggest that immune responses in the palatine tonsils of psoriasis patients are dysregulated. The elevated expression of CLA and IL-23 receptor by tonsil T cells may promote the egression of effector T cells from tonsils to the epidermis, suggesting that there may be functional changes within the tonsils, which promote triggering or exacerbation of psoriasis.

Keywords: CLA, follicle, palatine tonsils, psoriasis, streptococcus

Introduction

Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by highly noticeable erythematous, thickened, scaly plaques [1]. The plaques reflect a massive keratinocyte hyperproliferation driven by an inflammatory infiltrate rich in CD4+, CD8+ and γδ-T cells [2–4]. Psoriasis affects approximately 2% of people of both sexes [5], with diminished quality of life [6] and significant co-morbidities [7]. While psoriasis has been established to be a complex genetic disease [8], environmental factors such as trauma and stress can play a role in its elicitation [1]. Throat infections by β-haemolytic Streptococci have been associated with its initiation and acute exacerbation [9–15]. This interaction is not well characterized, but psoriasis patients are more vulnerable to throat infections than their aged-matched household controls [11]. The palatine tonsils are important for mucosal defences due to their location at the opening of the respiratory and digestive tracts as part of the efficient lymphoid defence system, termed Waldeyer's ring [16]. Tonsils are coated with a thick squamous epithelium that extends into branched crypts lined by reticulated epithelium [16]. Tonsils contain numerous secondary lymphoid follicles that form after antigen stimulation. These have a distinguished mantle zone that surrounds a highly organized and dynamic structure, the germinal centre (GC), which is divided into dark and light zones. Within the dark zone, B cells undergo somatic hypermutation and clonal expansion while the light zone is the den of antigen selection and cell proliferation. B cells that do not survive are removed by tingible body macrophages located throughout the GC [17]. The mantle zone contains various cell types, including naive B cells, mature B cells, T cells and dendritic cells. The extra-follicular area is also packed with T cells, mainly of the CD4+ phenotype.

The association between streptococcal throat infection and the onset or exacerbation of psoriasis has been observed in many studies [15], and this observation gave rise to the hypothesis that the T cells that drive psoriatic skin lesions might originate in tonsils, from where they migrate to the skin and stimulate plaque formation [18]. This is supported by the fact that skin T cells tend to be oligoclonal [18] and T cells isolated from the skin and tonsil of the same individual have been shown to carry the same TCRVB gene rearrangements, indicating a common origin [14].

Tonsillectomy appears to be beneficial for some psoriasis patients who have a history of skin disease exacerbation triggered by sore throat [15,19]. There is a strong correlation between disease improvement and a decline in the frequency of skin-homing T cells in the blood that recognize homologous peptides, present in both the streptococcal M protein and keratins in psoriatic skin [19]. This skin-homing characteristic is associated with the expression of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA), which has been shown to be induced by inflammatory stimuli such as interleukin (IL)-12 and streptococcal superantigens [20–22] released during streptococcal throat infections. CLA+ tonsil T cells can be T helper type 17 (Th17), Th22 or Th1 polarized, as these phenotypes have been shown to be increased in psoriatic skin [23–25] and blood [26].

It is currently not understood why, following streptococcal infection, only some people experience psoriatic outbreaks. One possible explanation is that the tonsil micro-environment of these individuals promotes the generation of inflammatory T cells that drive the skin disease. We investigated this possibility by comparing the histology of recurrently infected tonsils from psoriasis patients with those of individuals without skin disease, finding that tonsils from psoriasis patients contained smaller lymphoid follicles covering less tissue area, the proportion of germinal centre to marginal zone area was smaller and there were fewer tingible body macrophages per unit area. In addition, we examined the expression of a number of phenotypic T cell markers on CD4+ and CD8+ tonsil T cells using flow cytometry, and found that psoriasis patients' tonsils had a higher frequency of CLA+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and there was a significant correlation between tonsil and blood CLA+ T cell frequency. The psoriasis patients also had a higher frequency of tonsil T cells expressing IL-23 receptor, which was also expressed preferentially by the CLA+ T cell population.

Our results show that the tonsils of psoriasis patients are distinct histologically from non-psoriasis tonsils, both with regard to follicular morphology and the number of tingible body macrophages present within the GC. Furthermore, psoriasis tonsils had a higher frequency of T cells expressing CLA and IL-23 receptor. These findings might, to some extent, explain why tonsillectomy can have a beneficial effect in psoriasis.

Materials and methods

Study cohort and tissues

Palatine tonsils were obtained from eight patients with hypertrophic tonsils (HT), 66 patients with recurrent infections, 25 of whom were psoriasis patients (PST), and 41 were without skin disease (RT). Tonsils were obtained through routine tonsillectomies at the National University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland or as part of a clinical trial for tonsillectomy as a treatment for psoriasis [19]. A complete medical history was gathered from the psoriasis patients. For non-psoriatic donors, the age, sex and frequency of tonsil infections was obtained. All participants signed informed consent. The study was approved by the National Bioethics Committee of Iceland and conducted in compliance with good clinical practice and according to the Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

Tissue preparation and mononuclear cell isolation

Tonsils were stored immediately in cold sterile saline after excision until processed. For bacterial analyses, swabs were taken from both the crypt and the surface epithelium of the RT and the PST tonsils. For histological evaluation, tonsil tissue was snap-frozen in Tissue-Tek optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura Finetek, Zoeterwoude, NL) and kept at −70°C until processed. Tonsil mononuclear cells were isolated as described previously [27]. Briefly, tonsils were minced into 3-mm pieces, passed through a tea-sieve and washed with Hanks's balanced salt solution (HBSS; Gibco, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). Peripheral blood monuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from the heparinized venous blood of psoriatic individuals prior to tonsillectomy. All mononuclear cells were collected at the interphase fraction formed by density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Cells were then washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in PBS for fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) staining.

Evaluation of T cell surface receptor expression

Isolated mononuclear cells were stained for 30 min on ice with antibodies against CD4 (clone RPA-T4; Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), CD8 (RPA-T8; Biolegend), CLA (HECA-452; Biolegend), CCR4 (205410; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), CCR5 (HEK/1/85a; Biolegend), CCR6 (53103; R&D Systems), CCR7 (150503; R&D Systems), CCR8 (191704; R&D Systems), CCR10 (314305; R&D Systems), CXCR4 (12G5; Biolegend), CXCR5 (51505; R&D Systems), CXCR6 (56811; R&D Systems), IL-23R (218213; R&D Systems) CD62L [DREG-56; Biolegend), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) (HA58; Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA (BD)], CD69 (L78; Becton-Dickinson), CD25 (BC96; Biolegend) or the appropriate isotype controls. Cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed in 0·5% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Stained cells were analysed on a FACSCalibur (Becton-Dickinson) flow cytometer with CellQuest (Becton-Dickinson) software.

Immunohistochemistry

Fresh frozen 5-μm sections of tonsil were air-dried and fixed in cold acetone for 10 min and stained with haematoxylin (Thermo Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), followed by a dip into 37 mM ammonia solution. Sections were dehydrated in alcohol with a concentration gradient of 70–90–100%, fixed in Accustain (Sigma-Aldrich) and mounted with Mountex (Histolab Products AB, Göteborg, Sweden). After fixing, some sections were blocked with 1% hydrogen peroxide in PBS containing 3% mouse serum, washed in PBS and blocked for 20 min with 1·5% mouse serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), then incubated with monoclonal anti-CD68 (KP1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 30 min and stained according to the Vectastain Elite rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig)G kit protocol (Vector Laboratories). The staining was visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Becton-Dickinson) and counterstained with haematoxylin, as described previously. As a negative control, the primary antibody was omitted.

Bacterial culture and typing

Bacterial typing from throat swabs was carried out by culture on sheep blood agar and Streptococcus subspecies were identified using a Streptex kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Remel, Lenexa, KS, USA).

Histological measurements

Tonsil tissue was evaluated by measuring the size of the tissue area and the circumference of follicles, germinal centres and mantle zones. Measurements were collected in mm2 at 25× or ×100 magnification in two to four locations within the same tissue using Axiovision version 4·6·3 software (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Follicles were also counted in the visual field of ×25 magnification from at least four locations within the same tonsil tissue. All tonsil sections were coded and evaluated by a blinded observer. Macrophages were counted within the germinal centre at ×100 magnification. The number of crypts was counted at ×25 magnification. On average, three to four follicles were selected randomly per tissue section of each tonsil. One tissue section was utilized from every tonsil.

Statistics

Statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney U-test, Student's t-test, Fisher's exact test, Spearman's test or linear regression where appropriate.

Results

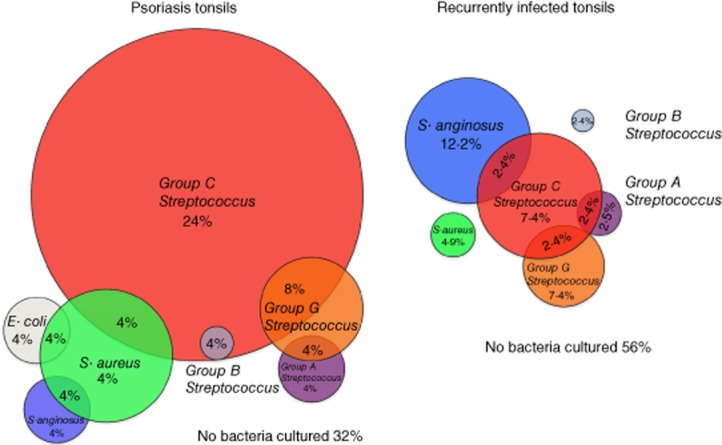

β-haemolytic Streptococcus is isolated more commonly from psoriasis tonsils

Given the previously reported associations between tonsil infections with β-haemolytic Streptococci and psoriasis [9–15], we first analysed the bacterial colonization of recurrently infected tonsils from individuals with and without psoriasis. All the donors of the recurrently infected tonsils (RT) reported that they had, on average, four symptomatic infections annually, and the group of psoriasis patients (PST) had been selected for a clinical trial on the basis that they had a history of worsening of their skin disease following throat infection [19]. Thus, we found that bacteria could be cultured from the tonsils of both groups with 68% of PST tonsils and 44% of RT tonsils positive for one or more species (Table 1, P = 0·0001, Fisher's exact test two-tailed P-value). We found that Group C Streptococcus was the dominant isolate from psoriatic tonsils and this was significantly more frequent in psoriatic than non-psoriatic tonsils (Table 1 and Fig. 1, 40 versus 14·6%, P = 0·021). In addition, all groups of β-haemolytic Streptococci (Groups A, B, C and G) were found to be over-represented significantly in psoriasis tonsils compared with recurrently infected tonsils (Table 1 and Fig. 1, P = 0·036 all groups combined). Interestingly, co-cultured bacteria were found more commonly in psoriatic tonsils (six of 25 versus two of 41, P = 0·0455), as were infections by bacterial species other than streptococcus (Table 1, six of 25 versus two of 41, P = 0·0455). No significant difference was observed between swabs taken from the crypts and the surface epithelium of the same tonsil. Interestingly, tobacco smoking appeared to influence the likelihood of bacterial infections among the psoriasis patients (P = 0·052, Fisher's exact test), but this information was not gathered from the RT group. Smoking did not appear to affect histological features of the tonsils.

Table 1.

Bacterial cultures from psoriasis and recurrently infected tonsils

| Tonsil | Bacteria cultured | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus of group: | Staphylococcus aureus | Escherichia coli | None | |||||

| A | B | C | G | Anginosus | ||||

| PST (25) | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 10 (40%) | 3 (12%) | 2 (8%) | 4 (16%) | 2 (8%) | 8 (32%) |

| RT (41) | 2 (4·9%) | 1 (2·4%) | 6 (14·6%) | 4 (9·8%) | 6 (14·6%) | 2 (4·9%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (56%) |

PST: psoriasis tonsils; RT: recurrently infected tonsils.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of bacteria isolated from recurrently infected tonsils of psoriasis patients and controls revealed that tonsils from psoriasis patients were infected more frequently by β-haemolytic Streptococci. Psoriasis tonsils (PST, left) were infected more frequently by β-haemolytic Streptococci than were the recurrently infected tonsils not associated with skin disease (RT, right, P = 0·021), with a strong bias towards Streptococcus C infection (P = 0·036). Two distinct bacterial species could be cultured from some of the tonsils, and this occurred significantly more frequently with PST tonsils (P = 0·001). In terms of co-infections, the co-culture of Streptococcus G and C was the only common factor between the two tonsil groups. No difference was observed in the overall number of uninfected tonsils [32% in PST versus 56% in recurrently infected tonsils (RT)]. Infections by bacterial species other than streptococcus were more frequent among the psoriasis tonsils (six of 25 versus two of 41, P = 0·0455). Fisher's exact test, two-tailed P-values.

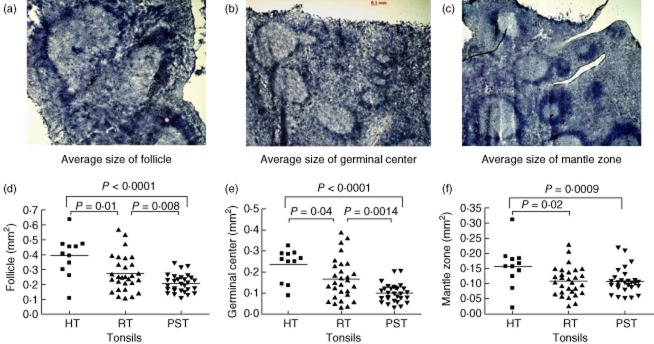

Tonsils from psoriasis patients contain small follicles dominated by mantle zone

To investigate whether there are underlying histological differences in recurrently infected tonsils from individuals with and without psoriasis, we measured the number and size of lymphoid follicles in haematoxylin-stained tonsil cryosections. Whole follicles were measured so that they included both the germinal centre (GC) and the mantle zone (MZ). Hypertrophic tonsils had, on average, the largest follicles (Fig. 2a,d), while the smallest were present in the psoriasis tonsils (Fig. 2c,d). This difference was due both to larger GC (Fig. 2e) and larger MZ within the HT tonsils (Fig. 2f). The RT follicles were most often larger than the psoriasis tonsils (Fig. 2b,d), but did not differ with regard to the size of the MZ area (Fig. 2f). Interestingly, some follicles had very small GC (Fig. 2b,c), while others had negligible MZ (Fig. 2a,b).

Fig. 2.

The follicles of psoriasis tonsils are smaller and have smaller germinal centres than hypertrophic and recurrently infected tonsils. Hypertrophic tonsils (HT, a) are tightly packed with enlarged follicles with noticeably large germinal centres. The recurrently infected tonsils (RT, b) and the psoriasis tonsils (PST, c) contain follicles of various sizes. Measurements of the follicular circumference revealed that PST follicles were smaller than the HT (d, P < 0·0001) and RT follicles (d, P = 0·008). The germinal centres were also significantly smaller in comparison to the other groups (e, HT, P < 0·001; RT, P = 0·0014), while the mantle zone of both RT (f, P = 0·02) and PST (f, P = 0·009) tonsils was smaller than in the HT group. All measurements were made in mm2 at ×25 magnification in two to four visual fields per tonsil. Statistical significance calculated with Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate; n.s.: not significant.

Hypertrophic tonsils are dominated by enlarged lymphoid follicles

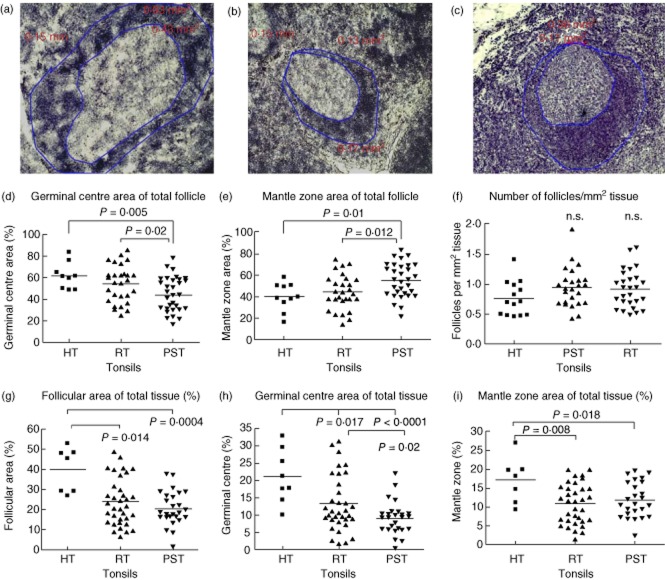

The relative proportions of the GC and the MZ areas revealed that follicles were dominated typically by a GC in the hypertrophic tonsils compared with RT and PST tonsils (Fig. 3a–d, P = 0·005 and P = 0·02, respectively). However, follicles in PST tonsils were dominated by their MZ, which was a significantly larger proportion of the follicle structure compared with that of HT (Fig. 3e, P = 0·012) or RT tonsil follicles (Fig. 3e, P = 0·01). No difference was observed in the number of follicles per unit area of tissue (Fig. 3f), despite the hypertrophic tonsils having a proportionally larger tissue area containing follicles (Fig. 3g). Tonsil stroma consists mainly of follicles and extrafollicular space. Evaluation of the follicle size, as a percentage of tissue that is filled by follicles, could give further indications of histological and functional differences between the tonsils. In hypertrophic tonsils, the follicles account for the largest part of the total tissue area compared with PST and RT tonsils (Fig. 3f, P = 0·0004 and P = 0·014, respectively), while no difference was observed between the PST and RT tonsils. The difference appeared to be due to both the larger size of the GC in the hypertrophic tonsils compared with PST (Fig. 3g, P < 0·0001) and RT tonsils (Fig. 3g, P = 0·017) and the MZ area (Fig. 3h: RT, P = 0·008; PST, P = 0·018). The difference between PST and RT tonsils was observed only in the evaluation of the GC as a proportion of total tissue (Fig. 3g, P = 0·02).

Fig. 3.

Psoriasis tonsils have smaller germinal centres and larger mantle zones. The germinal centre occupies a smaller part of the follicle in the psoriasis tonsils (PST, c) compared with the hypertrophic (HT, a, P = 0·005) and the recurrently infected tonsils (RT, b, P = 0·02) (a–d). Conversely, the mantle zone is the larger portion of the follicle in the PST tonsils compared with the HT (e, P = 0·019) and the RT tonsils (e, P = 0·012). The RT and HT tonsils appeared to be proportionally similar (d,e). Although the tonsils differed in the size of their follicles, there was no difference in follicle number (f). Evaluation of the total tissue area covered by follicles revealed that the HT tonsils had a significantly larger follicle area than both the PST and the RT tonsils (g, P = 0·0004 and P = 0·014, respectively). Germinal centres (GC) and mantle zones (MZ) were analysed further to distinguish which was the influencing factor. HT tonsils had both a larger GC and MZ than both the PST (h, P < 0·0001; i, P = 0·018) and the RT tonsils (h, P = 0·017; i, P = 0·08). However, the difference between RT and PST tonsils was present only for the GC (h) that was significantly smaller in the PST tonsils (P = 0·02). Data points represent average measurements of all follicles in each tonsil in mm2 at ×25 magnification in two to four visual fields for each tonsil. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U-tests as appropriate and indicated on each panel. Follicles shown at ×100 magnification.

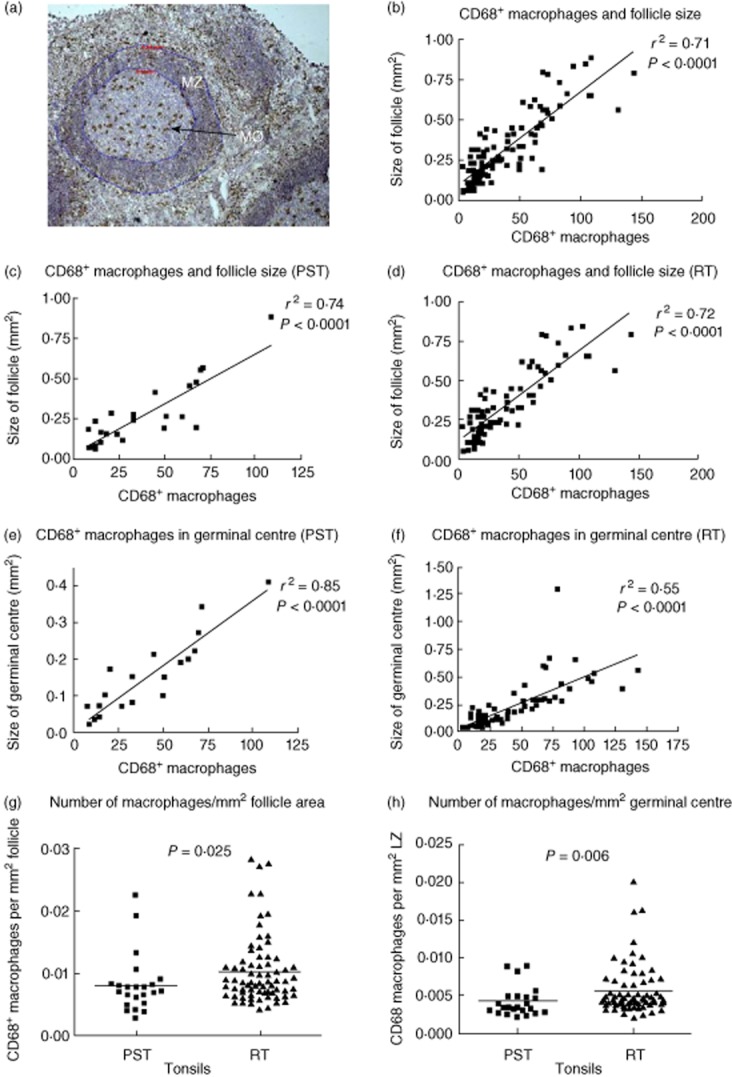

The number of CD68+ macrophages correlates with follicle size and is lower in the PST tonsils

The tingible body macrophages express CD68 on their surface and are located within the GC (Fig. 4a). Their number correlated with both the size of the follicle (Fig. 4b–d) and the GC in all tonsils (Fig. 4e–f). Interestingly, evaluation of the number of macrophages per mm2 of GC or follicle size revealed that they were fewer in the PST tonsils than the RT tonsils (Fig. 4g, P = 0·025; 4h, P = 0·06).

Fig. 4.

The number of CD68+ macrophages correlate with the size of the follicle. CD68+ tingible body macrophages were counted within the germinal centre (GC) (a, see arrow). The circumference of the follicle and the GC were measured and macrophages per square mm of either follicle or GC evaluated. A clear correlation is present between the number of CD68+ macrophages in the germinal centre and its size as well as the size of the whole follicle, regardless of pathology (b, r2 = 0·71). A positive correlation is also observed when analysed separately for psoriasis tonsils (PST) (c, r2 = 0·74) and recurrently infected tonsils (RT) (d, r2 = 0·72). A similar correlation is observed when the number of macrophages is analysed in regard to the size of the germinal GC alone, although the correlation is stronger for the psoriasis tonsils (e, r2 = 0·74 versus f, r2 = 0·74). The number of CD68 macrophages per mm2 area of GC was evaluated for both the GC (g) and the whole follicle (h). Macrophages were more numerous per mm2 of both areas in the recurrently infected tonsils. A total of five PST tonsils and 15 RT tonsils were analysed with, on average, four follicles being measured per tonsil. Statistical significance was determined using linear regression, t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test with P < 0·05 considered significant.

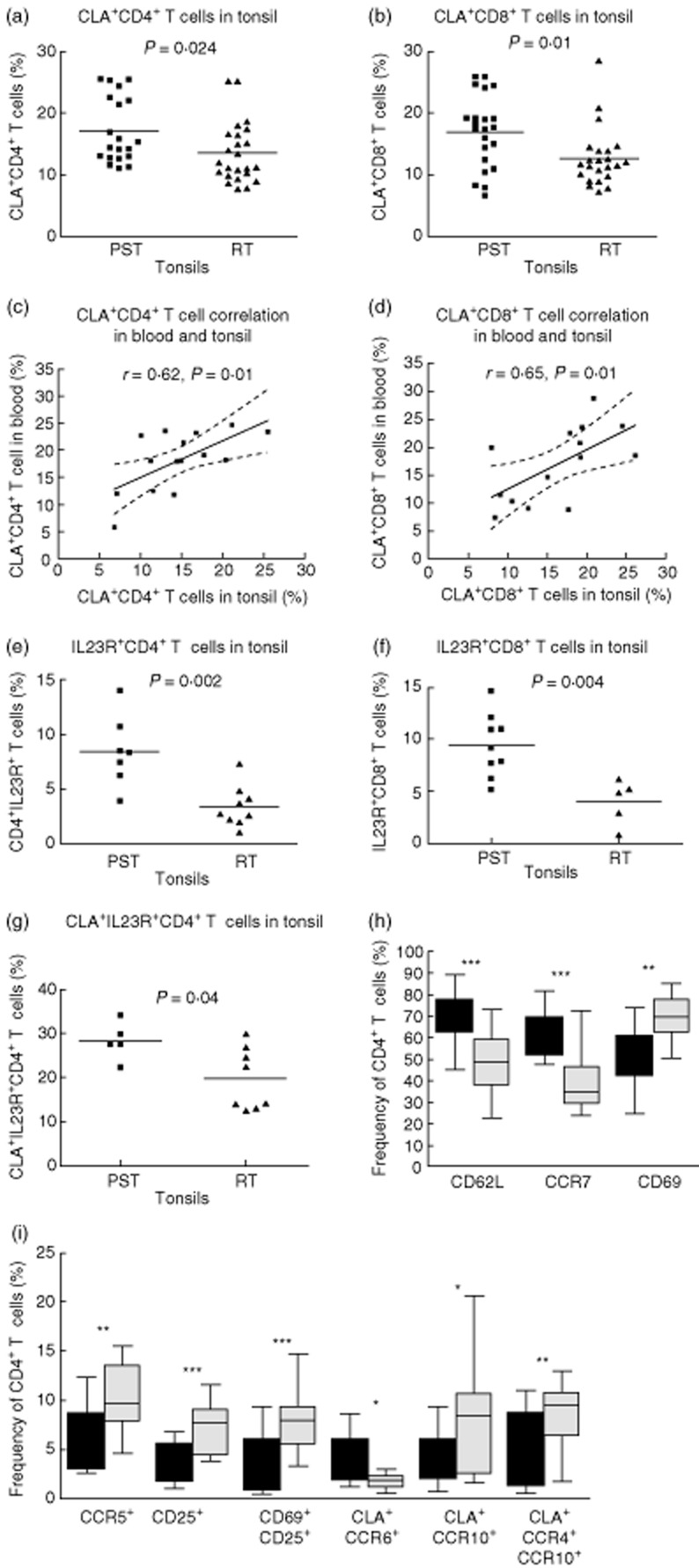

The frequency of skin-homing (CLA+) T cells is increased in the tonsils of psoriasis patients

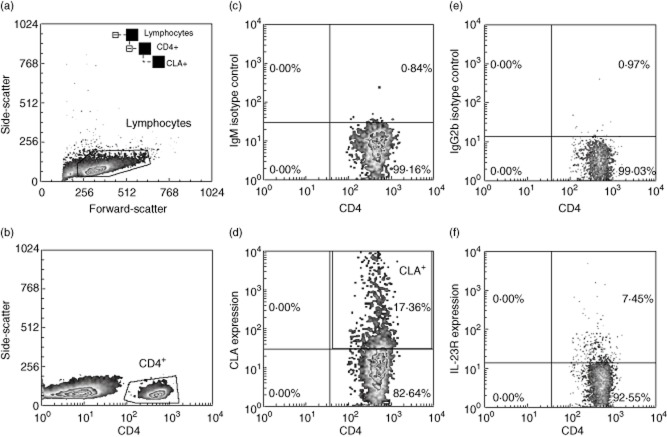

Given the association of sore throat and the onset or exacerbation of psoriasis, the skin-homing potential of tonsil T cells was evaluated by analysing the frequency of CLA+ T cells using flow cytometry. Our gating strategy is illustrated in Fig. 5. The frequency of CLA+ T cells was significantly higher in the PST tonsils compared with RT tonsils (Fig. 6a–b); this applied to both the CD4+ (P = 0·024) and the CD8+ T cell populations (P = 0·01). Furthermore, there was a fairly strong correlation between the frequencies of CLA+ T cells in the tonsils and blood (Fig. 6c,d) of psoriasis patients for both CD4+ (r = 0·62, P = 0·024) and CD8+ T cells (r = 0·65, P = 0·01).

Fig. 5.

Fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) gating strategy on tonsil mononuclear cells and examples of surface phenotype analysis. Following tonsil mononuclear cell isolation on Ficoll, cells were immunophenotyped using fluorescently labelled antibodies and flow cytometry. In this example we acquired 10 000 events then determined interleukin (IL)-23R expression on CD4+cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA)+ lymphocytes by first gating on lymphocytes (a), CD4-positive cells (b), then using an immunoglobulin (Ig)M isotype control (c) to determine CLA-positive cells (d). Gating on CD4+CLA+ lymphocytes, we determined IL-23R expression (e,f).

Fig. 6.

The frequency of skin-homing [cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA)+] T cells is higher in the psoriasis tonsils (PST) patients, and these cells express interleukin (IL)-23R preferentially. The frequency of CD4+ (P = 0·024) and CD8+ (P = 0·01) T cells expressing CLA was higher in the PST than the control tonsils (a,b). There was a correlation between the frequency of CLA+ T cells in the blood and tonsils of psoriasis patients CD4+ r = 0·62, P = 0·01, CD8+ r = 0·61, P = 0·02 (c,d). PSTs had a higher frequency of CD4+ (P = 0·002) and CD8+ (f, P = 0·004) T cells expressing IL-23R (e,f). Furthermore, the IL-23R was expressed preferentially by CLA+ CD4+ T cells, and such co-expression more frequent in the PST tonsils (g, P = 0·04). The frequency of CD4+ T cells expressing CD69 or CD25 alone (h, P = 0·0002 and i, P = 0·0005) or together (i, P = 0·0005) was higher in the recurrently infected tonsils (RT) tonsils. CCR5 expression was also higher in the RT tonsils (i, P = 0·009). Interestingly, CD69+ CD8+ T cells were more frequent in the RT tonsils (P = 0·03, not shown). Furthermore, CD4+ T cells co-expressing CLA and CCR10 (i, P = 0·047) or CCR4 and CCR10 (i, P = 0·006) were more frequent in the RT tonsils. CD4+ T cells expressing CCR7 (h, P < 0·0001), CD62L (h, P < 0·0001) or CLA and CCR6 (i, P = 0·047) were more frequent in PST than RT tonsils. Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals with Spearman's correlation in (c) and (d). For grouped data, statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test as appropriate. Box-plots show median and 95% confidence intervals for PST (n = 11, filled boxes) and RT (n = 22, grey boxes) tonsils.

IL-23R is expressed preferentially by skin-homing T cells in psoriasis tonsils

Analysis of the Th17-associated IL-23 receptor (IL-23R) revealed an increased frequency of both IL-23R+CD4+ T cells (P = 0·002) and IL-23R+CD8+ T cells (P = 0·004) in the psoriatic tonsils compared with RT tonsils (Fig. 6e,f). CD4+ T cells co-expressing CLA and IL-23R were marginally more common in the PST tonsils (Fig. 6g, P = 0·04), with no difference observed for the CD8+ T cells (not shown). Psoriatic tonsils also had a higher frequency of CD4+ T cells expressing the CD62L and CCR7+ (Fig. 6h, P < 0·0001 for both), suggestive of a central memory phenotype. Interestingly, CD4+ T cells expressing the activation markers CD69 or CD25 (Fig. 6h,i; P = 0·0002 and Fig. 6i; P = 0·0005) alone or concomitantly (Fig 5i, P = 0·0005) were significantly more frequent in the RT tonsils. This did not apply to CD8+ T cells. T cells from RT tonsils also had greater expression of CCR5 (Fig. 6i, P = 0·009). Furthermore, a higher co-expression of CLA with the skin-homing-associated molecules CCR10 (Fig. 6i, P = 0·047) and CCR4+CCR10+ (P = 0·006) was observed in the RT tonsils. Interestingly, CLA expression accompanying CCR6 (Fig. 6i, P = 0·047) was more common among the CD4+ T cells in the PST tonsils. No difference was observed between the PST and RT tonsils for CCR4 or CCR10 alone (data not shown).

Discussion

The palatine tonsils form an important part of the mucosal defence system of the upper respiratory tract and the opening of the digestive tract. Due to their location, infections by bacteria, virus and fungi are common, although only few cause symptomatic sore throat. In some instances infections can become persistent, leading to the eventual removal of the tonsils by tonsillectomy. Comparison of the bacteriology of recurrently infected tonsils from psoriasis patients and individuals without skin disease confirmed that bacterial infections were more common among the psoriasis tonsils (Table 1, P = 0·0001) and that tobacco smoking appeared to increase their vulnerability to infection (P = 0·0529).

Psoriasis has a complex genetic background, and numerous linkage studies, followed by genome-wide association studies (GWAS), have resulted in the identification of 41 genetic susceptibility loci [28], 36 of which are associated with genes that have a known immunological function [28] and might be important to the immune responses of the tonsils. These include genes involved in T cell and innate cell function such as ERAP1, IL12B, IL23R, IL23A, NOS, TYK2 and STAT3, as well as TNIP1, TRAF3IP2, TNFAIP3, CARD14 and REL, important for nuclear factor (NF)-κB signal transduction. Thus, the differences in bacterial colonization and tonsil histology reported here may be partly the consequence of particular allele carriage at these loci influencing tonsil innate and adaptive immune responses.

Of note is the ability of some bacteria, including streptococci, to penetrate and survive in host cells as facultative intracellular bacteria [29,30], which renders antibiotic treatment challenging [31–35] and probably influences the outcome of bacterial swab tests, which typically only culture extracellular organisms. Moreover, tonsils are typically not excised during infectious episodes, probably adding to the underestimation of bacteria species. The recent introduction of high-throughput DNA/RNA sequencing for studies of the microbiome, which does not rely on the ability of bacteria to grow on selection media, are now revealing the true diversity of tonsil flora [36,37].

The bacterial infections noted here were mainly by β-haemolytic Streptococci (serotypes A, B, C and G, P = 0·021), in particular Group C Streptococci (Table 1, P = 0·036), which have been associated with psoriasis [9–12]. Streptococcal infections have been shown to induce the expression of the skin-homing molecule CLA on the surface of T cells [20–22,38–40]. We have reported previously that psoriasis patients have an increased frequency of CLA+ T cells in the blood [40], and in this study we show the same pattern in the psoriasis tonsils (Fig. 6a,b). Peptides sharing homologous sequences from streptococcal M protein and human epidermal keratins have been shown to stimulate CLA+ T cells from the blood of psoriasis patients [39] and lesional T cell clones have been shown to respond in a HLA-restricted manner to streptococcal peptidoglycan [41]. We have postulated that these T cells play an important role in psoriasis [18], as improvement after tonsillectomy correlates closely with their reduction in blood [19] and T cell clones with similar TCRVB gene usage have been isolated from the tonsils and skin lesions of psoriasis patients [14]. The finding that psoriasis tonsils are infected more commonly by streptococcus and have a higher T cell CLA expression in tonsils that correlate with levels in blood (Fig. 6c,d) is consistent with the notion that streptococcal antigen-specific T cells are involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, and that effector T cells generated in the tonsils could migrate through the circulation to the skin.

The epidermal proliferation characteristic of psoriasis is now thought to be driven, at least in part, by IL-17- and IL-22-secreting T cells [23,42]. T cells releasing IL-17, IL-22 and related cytokines commonly express IL-23R and CCR6 and these cells were more frequent in the psoriasis tonsils (Fig. 6), suggesting a potential Th17 cytokine bias. A number of studies have shown increased expression of cytokines by T cells from RT compared with HT tonsils, with a predominance of Th1 over Th2 cytokines [43–45]. When cells from HT and RT tonsils were stimulated with intact, heat-inactivated Haemophilus influenzae and Group A Streptococcus, H. influenza induced IL-1α, IL-1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-2, interferon (IFN)-γ, TNF-β and IL-10 production in both tonsil groups, but Group A Streptococcus induced significantly higher frequencies of IFN-γ-positive cells in the RT group [46]. Similar findings emerged when T cells from HT and RT tonsils were stimulated with isolated streptococcal M-protein, with S. pyogenes-positive RT tonsil T cells secreting more IFN-γ [45]. These reports all indicate that cytokine production by tonsil lymphocytes is elevated in RT compared with HT, and suggest that the pattern of cytokine expression probably differs accordingly to match the pathogenic challenge. Since the emergence of Th17, Th22 and Th9 phenotypes, further studies analysing these T cell phenotypes in terms of cytokine and adhesion/homing molecule expression and localization in tonsils are now warranted.

Although a number of case reports [15] and our recent prospective study [19] suggest that tonsillectomy had a positive outcome on the disease activity of some psoriasis patients, this might be restricted to individuals with a genetic predisposition [e.g. human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw6 carriers] and a history of skin disease exacerbation with sore throat. Follow-up periods vary in these reports, and although several years of remission have been reported it is uncertain whether or not this is permanent, given the dynamic nature of the immune response and the possibility of tonsil regrowth.

Psoriasis tonsils differed from recurrently infected tonsils by containing more CD4+ T cells with lymphoid migrating abilities, expressing more CD62L+ and CCR7+, both of which are important for homing to lymph nodes and T cell areas [47,48]. These findings, along with the differential expression of the activation markers CD69 and CD25, implicate a dysregulation of innate immune mechanisms in the PST tonsils that influences the differentiation of T cells. This was evaluated further by comparing the histological characteristics of the tonsil. The histology of hypertrophic and recurrently infected tonsils has been studied thoroughly [49,50] whereas, hitherto, psoriasis tonsils have been histologically undefined. In this study we show that psoriasis tonsils have unique histological characteristics that distinguish them from other tonsils. Tonsil follicles can differ with respect to their reactivity regardless of pathology [51]. Hypertrophic tonsils have large noticeable and clearly defined follicles with an extrafollicular area that is dense with multiple cells (Fig. 2a). The psoriasis tonsils, however, have follicles that are often less defined, and the extrafollicular area appears less densely packed (Fig. 2c); the RT tonsils appear to have an intermediate characteristic (Fig. 2b), with more crypts than HT tonsils (P = 0·018). PST follicles are smaller (Fig. 2) and cover less tissue area (Fig. 3). The composition of the follicles was also different, as they have a lower GC : MZ ratio than the other tonsils. Not all follicles were similar in size and structure in the three groups, as some had proportionally smaller GC and larger MZ. On rare occasions, follicles with limited MZ or hardly noticeable GC were observed. Germinal centres are important for the humoral immune response, as B cell proliferation, differentiation and immunoglobulin class-switching occurs in the GC. The hypertrophic tonsils in this study had the largest follicles and GC, which also covered the greatest tissue area indicating a highly active GC, which is in accordance with earlier studies [49,50]. Why the follicles become enlarged is not understood, but it has been suggested that viral infections causing repeated irritation or lack of cell apoptosis within the GC might be the causal factor [52]; future microbiome studies of the tonsils might shed light on the viral hypothesis. It is possible that the smaller size of the psoriasis follicles is due to a dysfunctional regulation of the GC immune response. Analysis of the tingible body macrophages within the GC can give indications of its function, as their role is to ingest cellular debris within the germinal centre [53] and possibly to down-regulate the GC reaction [54]. Interestingly, the number of CD68 macrophages correlated strongly with both the size of the follicle and the GC. However, psoriasis follicles had fewer macrophages per mm2 of both GC and follicle area than the RT tonsils. This could cause an accumulation of apoptotic cells within the GC that might interrupt its function and increase the risk of autoantigens. Interestingly, with smaller follicles the T cell area, the extrafollicular area, becomes proportionally enlarged. It could be hypothesized that the combination of increased incidences of streptococcal infections and smaller follicles with possible dysfunction in the regulation of the immune response might lead to insufficient clearance of the bacteria, thus causing enhanced intracellular reservoirs of the bacterium within macrophages and epithelial cells. These could reinfect later, when conditions are favourable. In this respect, it has been shown that approximately 9% of psoriasis patients are symptomless carriers of streptococcus, which is 20% more common than in their household controls [11]. However, in the present study the psoriasis patients were selected on the basis of a known association of sore throat and exacerbation of their disease resulting in a carrier rate of 44% for Streptococcus Groups A, C and G combined.

These results suggest that the immune response in the tonsils of psoriasis patients is abnormal. These data are consistent with the idea that the infiltrating T cells which drive psoriatic skin disease might originate in tonsils where streptococcal infection induces a skin-homing phenotype. CD68+ macrophages containing peptidoglycan, thought to have originated in the tonsils, have been found in increased numbers in psoriatic skin lesions [52], and lesional CD4+ T cell clones have been shown to respond in an HLA-restricted manner to this streptococcal peptidoglycan [52]. Thus, the recurrent tonsil infections could lead to the maturation of skin-homing T cells that recognize streptococcal membrane and cell wall moieties [55] which, after migration to the skin, could react with streptococcal epitopes [52] or alternatively skin-specific epitopes via molecular mimicry [18,56], leading to the development of psoriasis plaques.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the Icelandic Research Fund (grant number 080448021-23), the Icelandic Research Fund for Graduate Students, Landspitali University Hospital Research Fund and the Research Fund of the University of Iceland for Doctoral Studies. The authors thank the staff of the ear, nose and throat department, Landspitali-Fossvogur, Reykjavik for their assistance. Andrew Johnston is supported by the Babcock Endowment Fund and the American Skin Association.

Disclosures

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gudjonsson JE, Elder JT. Psoriasis. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AM, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. pp. 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker BS, Swain AF, Fry L, Valdimarsson H. Epidermal T lymphocytes and HLA-DR expression in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:555–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb04678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bos JD, Hulsebosch HJ, Krieg SR, Bakker PM, Cormane RH. Immunocompetent cells in psoriasis. In situ immunophenotyping by monoclonal antibodies. Arch Dermatol Res. 1983;275:181–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00510050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laggner U, Di Meglio P, Perera GK, et al. Identification of a novel proinflammatory human skin-homing Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cell subset with a potential role in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2011;187:2783–2793. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377–385. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelfand JM, Feldman SR, Stern RS, Thomas J, Rolstad T, Margolis DJ. Determinants of quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a study from the US population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:704–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimball AB, Gladman D, Gelfand JM, et al. National Psoriasis Foundation clinical consensus on psoriasis comorbidities and recommendations for screening. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:1031–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elder JT, Bruce AT, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Molecular dissection of psoriasis: integrating genetics and biology. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1213–1226. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fry L. Psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119:445–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb03248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telfer NR, Chalmers RJ, Whale K, Colman G. The role of streptococcal infection in the initiation of guttate psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gudjonsson JE, Thorarinsson AM, Sigurgeirsson B, Kristinsson KG, Valdimarsson H. Streptococcal throat infections and exacerbation of chronic plaque psoriasis: a prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:530–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wardrop P, Weller R, Marais J, Kavanagh G. Tonsillitis and chronic psoriasis. Clin Otolaryngol. 1998;23:67–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1998.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen JE. The relationship between infection with group A beta hemolytic streptococci and the development of psoriasis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:153–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diluvio L, Vollmer S, Besgen P, Ellwart JW, Chimenti S, Prinz JC. Identical TCR beta-chain rearrangements in streptococcal angina and skin lesions of patients with psoriasis vulgaris. J Immunol. 2006;176:7104–7111. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.7104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sigurdardottir SL, Thorleifsdottir RH, Valdimarsson H, Johnston A. The role of the palatine tonsils in the pathogenesis and treatment of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry M, Whyte A. Immunology of the tonsils. Immunol Today. 1998;19:414–421. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Victora GD, Nussenzweig MC. Germinal centers. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:429–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valdimarsson H, Thorleifsdottir RH, Sigurdardottir SL, Gudjonsson JE, Johnston A. Psoriasis – as an autoimmune disease caused by molecular mimicry. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorleifsdottir RH, Sigurdardottir SL, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Improvement of psoriasis after tonsillectomy is associated with a decrease in the frequency of circulating T cells that recognize streptococcal determinants and homologous skin determinants. J Immunol. 2012;188:5160–5165. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung DY, Gately M, Trumble A, Ferguson-Darnell B, Schlievert PM, Picker LJ. Bacterial superantigens induce T cell expression of the skin-selective homing receptor, the cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen, via stimulation of interleukin 12 production. J Exp Med. 1995;181:747–753. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy M, Davis C, Wong J, Prabhakar U. Cutaneous lymphocyte antigen expression on activated lymphocytes and its association with IL-12R (beta1 and beta2), IL-2Ralpha, and CXCR3. Cell Immunol. 2005;236:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sigmundsdottir H, Johnston A, Gudjonsson JE, Valdimarsson H. Differential effects of interleukin 12 and interleukin 10 on superantigen-induced expression of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA) and alphaEbeta7 integrin (CD103) by CD8+ T cells. Clin Immunol. 2004;111:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kryczek I, Bruce AT, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Induction of IL-17+ T cell trafficking and development by IFN-gamma: mechanism and pathological relevance in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2008;181:4733–4741. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harper EG, Guo C, Rizzo H, et al. Th17 cytokines stimulate CCL20 expression in keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo: implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2175–2183. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowes MA, Kikuchi T, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Psoriasis vulgaris lesions contain discrete populations of Th1 and Th17 T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1207–1211. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagami S, Rizzo HL, Lee JJ, Koguchi Y, Blauvelt A. Circulating Th17, Th22, and Th1 cells are increased in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1373–1383. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston A, Sigurdardottir SL, Ryon JJ. Isolation of mononuclear cells from tonsillar tissue. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0708s86. Chapter 7: Unit 7 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsoi LC, Spain SL, Knight J, et al. Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1341–1348. doi: 10.1038/ng.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaPenta D, Rubens C, Chi E, Cleary PP. Group A streptococci efficiently invade human respiratory epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12115–12119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osterlund A, Popa R, Nikkila T, Scheynius A, Engstrand L. Intracellular reservoir of Streptococcus pyogenes in vivo: a possible explanation for recurrent pharyngotonsillitis. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:640–647. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199705000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foote PA, Jr, Brook I. Penicillin and clindamycin therapy in recurrent tonsillitis. Effect of microbial flora. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115:856–859. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1989.01860310094031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orrling A, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, Schalen C. Clindamycin in recurrent group A streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis – an alternative to tonsillectomy? Acta Otolaryngol. 1997;117:618–622. doi: 10.3109/00016489709113448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owen CM, Chalmers RJ, O'Sullivan T, Griffiths CE. A systematic review of antistreptococcal interventions for guttate and chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:886–890. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brook I. Failure of penicillin to eradicate group A beta-hemolytic streptococci tonsillitis: causes and management. J Otolaryngol. 2001;30:324–329. doi: 10.2310/7070.2001.19359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brook I, Leyva F. The treatment of the carrier state of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci with clindamycin. Chemotherapy. 1981;27:360–367. doi: 10.1159/000238005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5721–5732. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segata N, Haake SK, Mannon P, Lemon KP, Waldron L, Gevers D, Huttenhower C, Izard J. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R42. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zollner TM, Nuber V, Duijvestijn AM, Boehncke WH, Kaufmann R. Superantigens but not mitogens are capable of inducing upregulation of E-selectin ligands on human T lymphocytes. Exp Dermatol. 1997;6:161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1997.tb00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnston A, Gudjonsson JE, Sigmundsdottir H, Love TJ, Valdimarsson H. Peripheral blood T cell responses to keratin peptides that share sequences with streptococcal M proteins are largely restricted to skin-homing CD8 T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;138:83–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sigmundsdottir H, Gudjonsson JE, Jonsdottir I, Ludviksson BR, Valdimarsson H. The frequency of CLA+ CD8+ T cells in the blood of psoriasis patients correlates closely with the severity of their disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;126:365–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker BS, Laman JD, Powles A, et al. Peptidoglycan and peptidoglycan-specific Th1 cells in psoriatic skin lesions. J Pathol. 2006;209:174–181. doi: 10.1002/path.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiricozzi A, Guttman-Yassky E, Suarez-Farinas M, et al. Integrative responses to IL-17 and TNF-alpha in human keratinocytes account for key inflammatory pathogenic circuits in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:677–687. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agren K, Andersson U, Nordlander B, et al. Upregulated local cytokine production in recurrent tonsillitis compared with tonsillar hypertrophy. Acta Otolaryngol. 1995;115:689–696. doi: 10.3109/00016489509139388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quiding M, Granstrom G, Nordstrom I, Ferrua B, Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C. High frequency of spontaneous interferon-gamma-producing cells in human tonsils: role of local accessory cells and soluble factors. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;91:157–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb03372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerakawauchi H, Kurono Y, Mogi G. Immune responses against Streptococcus pyogenes in human palatine tonsils. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:634–639. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199705000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agren K, Brauner A, Andersson J. Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pyogenes group A challenge induce a Th1 type of cytokine response in cells obtained from tonsillar hypertrophy and recurrent tonsillitis. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1998;60:35–41. doi: 10.1159/000027560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell JJ, Murphy KE, Kunkel EJ, et al. CCR7 expression and memory T cell diversity in humans. J Immunol. 2001;166:877–884. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown MN, Fintushel SR, Lee MH, et al. Chemoattractant receptors and lymphocyte egress from extralymphoid tissue: changing requirements during the course of inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;185:4873–4882. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang PC, Pang YT, Loh KS, Wang DY. Comparison of histology between recurrent tonsillitis and tonsillar hypertrophy. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2003;28:235–239. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2003.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gorfien JL, Hard R, Noble B, Brodsky L. Quantitative study of germinal center area in normal and diseased tonsils using image analysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:398–402. doi: 10.1177/000348949910800414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sigurdardottir SL, Thorleifsdottir RH, Guzman AM, Gudmundsson GH, Valdimarsson H, Johnston A. The anti-microbial peptide LL-37 modulates immune responses in the palatine tonsils where it is exclusively expressed by neutrophils and a subset of dendritic cells. Clin Immunol. 2012;142:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez-Gonzalez MA, Diaz P, Delgado F, Lucas M. Lack of lymphoid cell apoptosis in the pathogenesis of tonsillar hypertrophy as compared to recurrent tonsillitis. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158:469–473. doi: 10.1007/s004310051122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tabe H, Kawabata I, Koba R, Homma T. Cell dynamics in the germinal center of the human tonsil. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1996;523:64–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith JP, Burton GF, Tew JG, Szakal AK. Tingible body macrophages in regulation of germinal center reactions. Dev Immunol. 1998;6:285–294. doi: 10.1155/1998/38923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker BS, Brown DW, Fischetti VA, et al. Skin T cell proliferative response to M protein and other cell wall and membrane proteins of group A streptococci in chronic plaque psoriasis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;124:516–521. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Besgen P, Trommler P, Vollmer S, Prinz JC. Ezrin, maspin, peroxiredoxin 2, and heat shock protein 27: potential targets of a streptococcal-induced autoimmune response in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2010;184:5392–5402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]