Abstract

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) containing either the α4 and/or α6 subunit are robustly expressed in dopaminergic nerve terminals in dorsal striatum where they are hypothesized to modulate dopamine (DA) release via acetylcholine (ACh) stimulation from cholinergic interneurons. However, pharmacological blockade of nAChRs or genetic deletion of individual nAChR subunits, including α4 and α6, in mice, yields little effect on motor behavior. Based on the putative role of nAChRs containing the α4 subunit in modulation of DA in dorsal striatum, we hypothesized that mice expressing a single point mutation in the α4 nAChR subunit, Leu9′Ala, that renders nAChRs hypersensitive to agonist, would exhibit exaggerated differences in motor behavior compared to WT mice. To gain insight into these differences, we challenged WT and Leu9′Ala mice with the α4β2 nAChR antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE). Interestingly, in Leu9′Ala mice, DHβE elicited a robust, reversible motor impairment characterized by hypolocomotion, akinesia, catalepsy, clasping, and tremor; whereas the antagonist had little effect in WT mice at all doses tested. Pre-injection of nicotine (0.1 mg/kg) blocked DHβE-induced motor impairment in Leu9′Ala mice confirming that the phenotype was mediated by antagonism of nAChRs. In addition, SKF 82958 (1 mg/kg) and amphetamine (5 mg/kg) prevented the motor phenotype. DHβE significantly activated more neurons within striatum and substantia nigra pars reticulata in Leu9′Ala mice compared to WT animals, suggesting activation of the indirect motor pathway as the circuit underlying motor dysfunction. ACh evoked DA release from Leu9′Ala striatal synaptosomes revealed agonist hypersensitivity only at α4(non-α6)* nAChRs. Similarly, α6 nAChR subunit deletion in an α4 hypersensitive nAChR (Leu9′Ala/α6KO) background had little effect on the DHβE-induced phenotype, suggesting an α4(non-α6)* nAChR-dependent mechanism. Together, these data indicate that α4(non-α6)* nAChR have an impact on motor output and may be potential molecular targets for treatment of disorders associated with motor impairment.

Keywords: nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, motor behavior, basal ganglia, dopamine

1. Introduction

Balanced dopamine (DA) concentrations in striatum (ST) are essential for proper functioning of the basal ganglia circuitry and voluntary movement (Rice et al., 2011). Pathologically low DA concentrations, as caused by progressive neurodegeneration of substantia nigra pars compacta DAergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease, leads to motor dysfunction, including akinesia, bradykinesia, resting tremor and catalepsy (Martin et al., 2011). DA release in striatum (as well as other brain regions such as prefrontal cortex and hippocampus) is, in part, modulated by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), ligand gated cation channels expressed on DAergic cell bodies and terminals, which are activated by the endogenous neurotransmitter, acetylcholine (ACh), as well as by the addictive component of tobacco smoke, nicotine (Grady et al., 2007, Albuquerque et al., 2009, Tang and Dani, 2009). Indeed, within striatum, high basal levels of ACh are achieved via tonic activity of striatal large aspiny cholinergic interneurons, suggesting activation of DAergic terminal nAChRs as key regulators of DA release (Zhou et al., 2001, Quik and McIntosh, 2006, Threlfell et al., 2012).

There are at least three major high affinity populations of nAChRs expressed in DAergic neurons in substantia nigra pars compacta: Those that contain the α4 subunit (α4* nAChR, “*” indicates other subunits coassemble with α4 within a petameric nAChR complex), those that contain the a6 subunit (α6* nAChR), and those that contain both subunits (α4α6* nAChR) (Salminen et al., 2004, Grady et al., 2007, Salminen et al., 2007, Gotti et al., 2010). While the majority of data indicating an involvement of nAChRs in modulating DA release from DAergic nerve terminals stems from studies of rodent synaptosomes and striatal slices (Zhou et al., 2001, Salminen et al., 2004, Zhang et al., 2009, Exley et al., 2012, Threlfell et al., 2012), pharmacological blockade of these receptors in mice have little impact on motor behavior (Dwoskin et al., 2008, Jackson et al., 2009). In addition, mouse models that do not express the genes encoding either α4 or α6 nAChR subunits reveal few motor deficits, perhaps due to compensatory mechanisms (Ross et al., 2000, Champtiaux et al., 2002, Marubio et al., 2003). Thus, the precise impact of α4*, α6*, and α4α6* nAChRs on motor behavior is unclear.

While knock-out mice provide insight into the necessity of a targeted nAChR subunit, an alternative strategy is to study mouse models harboring “gain-of-function” mutations in a nAChR subunit (Lester et al., 2003, Drenan and Lester, 2012). To date, mice with a gain-of-function mutation in both α4 and α6 subunits have been generated (Tapper et al., 2004, Drenan et al., 2008a). BAC-transgenic mice expressing α6* nAChR with a point mutation that causes agonist hypersensitivity are hyperactive in both a novel environment and in the home cage (Drenan et al., 2008a). However, hyperactivity is abolished by crossing these animals with α4 KO mice, indicating that increased motor activity is a result of α4α6* nAChRs that are hypersensitive to ACh (Drenan et al., 2010). To date, motor activity of α4 gain-of-function mice has not been studied in detail.

Therefore, we were interested in elucidating a role for α4* nAChRs in basal ganglia related-movement behavior by analyzing motor behavior in knock-in mice that express α4 nAChR subunits with a point mutation (a leucine mutated to an alanine, the Leu9′Ala line) in the second transmembrane pore-forming region rendering functional receptors 50-fold more sensitive to agonist including ACh (Tapper et al., 2004, Fonck et al., 2005). We hypothesized that, if endogenous ACh stimulation of α4* nAChRs were important for DA-dependent motor behavior, then blockade of these receptors in Leu9′Ala mice would have exaggerated effects helping to uncover the role of these receptors on motor output.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Male and female (8- to 14- week-old) Leu9′Ala knock-in mice, α6 KO mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates were used for all experiments. The genetic engineering of Leu9′Ala and α6 KO mice have been described previously (Champtiaux et al., 2002, Tapper et al., 2004). These mice have been backcrossed to the C57BL/6J background for at least 9 generations. Mice, bred at University of Massachusetts Medical School or the Institute for Behavioral Genetics, University of Colorado, were housed four mice/ cage, received food and water ad libitum and kept on a standard 12-h light-dark cycle. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals provided by the National Research Council (National Research Council, 1996) or the guidelines for care and use of mice provided by National Institutes, as well as with an approved animal protocol from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School or the Animal Care and Utilization Committee of the University of Colorado.

2.2. Drugs

Nicotine hydrogen bitartrate, methyllycaconitine citrate salt hydrate, hexamethonium, D-amphetamine hemisulfate salt, Cloro-APB hydrobromide (SKF 82958), S-(-)-eticlopride hydrocloride, nomifensine, pargyline, atropine sulfate, bovine serum albumin (BSA) and diisopropylfluorophosphophate (DFP) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA. Dihydro-β-erythrodine hydrobromide (DHβE) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience Bristol, UK. N-2-(hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N’-(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES) and sodium salt were products of BDH Chemicals distributed by VWR (Denver, CO). [3H]-dopamine ([3H]-DA) (25−40 Ci/mmol) and Optiphase Supermix scintillation cocktail were purchased from Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Boston, MA). α-Conotoxin MII (α-CtxMII) was obtained from Dr. J. Michael McIntosh (University of Utah). All drugs administered to mice were dissolved in 0.9% saline and administered via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection at the indicated doses.

2.3. Motor Characterizations

Drug Naïve mice were placed into novel cages and allowed time to habituate to the cage. At time point 0 min, mice were tested for akinesia, catalepsy, clasping and tremor (described below). Immediately after baseline testing, mice were injected with saline or DHβE and characterizations were conducted for each mouse at the indicated time points over a 180 min period. In preliminary experiments, the effects of DHβE on motor phenotypes including locomotor activity, catalepsy, tremor and akinesia was analyzed between genders in Leu9′Ala mice. Because the resulting analysis revealed no significant effect of gender (data not shown), data from male and female mice were combined.

2.4. Akinesia

Every 30 min, mice were placed into an empty cage and held by the tail so hind limbs were hovering above the floor with forelimbs in contact with the floor of the cage. The number of each forelimb steps forward was counted for 30 s. This was repeated and the two trials were averaged together.

2.5. Catalepsy

The forelimbs of mice were placed on a raised bar 5 cm from the floor. Latency to remove both forelimbs off the bar was measured for up to 2 minutes. Catalepsy was measured every 60 min.

2.6. Clasping and Tremor

Mice were tested for clasping and tremor by raising a mouse by the tail for 30 seconds and giving a score to depict the degree to which the hind limbs were spread apart (clasping) or for severity of a body tremor. The scoring for clasping was as follows: 0= hind limbs spread wide apart (normal position), 1= hind limbs 25% closed, 2= hind limbs 50% closed, 3= hind limbs 75% closed with periods of hind limbs clasped, 4= hind limbs fully clasped for 10 seconds. The severity of a body tremor was scored: 0= no tremor, 1= isolated twitches, 2= non-continuous tremors, 3= consistent tremor.

2.7. Locomotor Activity

For all experiments measuring locomotor activity, mice were given saline injections once a day for 3 days prior to the experiment to reduce differences in locomotor activity due to stress from the injection and handling. Additionally, on the day of the experiment, mice were habituated to the room for 1 hr to reduce differences in locomotor activity due to changes in environment unrelated to the novel cage. To measure locomotor activity, mice were placed into an individual cage within an infrared photobeam frame (San Diego Instruments) to freely roam for 30 min. Locomotor activity was measured by quantifying the number of beam breaks. Mice were challenged with saline or DHβE and placed into the locomotor chamber at the times indicated. Locomotor experiments were counterbalanced such that mice were exposed to either saline or drug and then one week late, drug treatments were switched. Thus, each mouse served as its own control. Additional drug treatments (MLA and nicotine) and blocking experiments were tested in separate groups of mice. On the day of the experiment, mice were pre-injected with saline, nicotine, SKF82958, eticlopride, or amphetamine followed by saline (i.p.) or DHβE 5 min after pre-injection as indicated. For the amphetamine rescue experiment, mice were injected with DHβE followed by an injection of saline or amphetamine 15 min after the first injection. Mice were placed into locomotor chambers at the times indicated post injection and locomotor activity was measured for 30 minutes.

2.8. Immunofluorescence

To avoid neuronal activation due to stress induced handling, all mice were injected with saline once a day for 3 days before the experiment. Separate groups of drug naïve Leu9’Ala and WT mice received either saline or DHβE and perfused 150 minutes later. Prior to perfusion, mice were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg i.p.) and then perfused transcardially with ice-cold 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) followed by 10 mls ice-cold 4% (W/V) paraformaldehyde (PFA) dissolved in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.5). The brains were harvested and post-fixed in PFA solution for 4 hr and then cryoprotected in PBS containing 30% sucrose until the brain was fully fixed (> 72 hrs) in sucrose solution. Coronal sections (20 µm thick) containing the striatum (ST) (between 1.18 and 0.38 from bregma) and the substantia nigra (SN) (between −2.92mm and −3.8mm from bregma) were sliced on a microtome (Leica SM 2000 R, Leica Microsystems Inc., Bannockburn IL, USA) and collected into a 24-well plate containing 1x PBS. Sections were washed for 5 minutes in 1x PBS, placed into 0.4% Triton X-100 PBS (PBST) for 5 minutes, washed again with 1x PBS for 5 minutes, and then incubated in a blocking solution containing 2% BSA in PBS for 30 min. Sections were incubated with primary antibody for c-Fos (polyclonal, 1:400, Santa Cruz) and ChAT (monoclonal 1:100, Santa Cruz) or Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH, monoclonal, 1:1000, Santa Cruz) in the blocking solution overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed three times for 5 minutes and incubated in blocking solution for 30 min followed by another incubation in the blocking solution containing secondary fluorescently-labeled antibodies, goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor® 488 and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor® 594 (1:800, Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene USA) at room temperature for 30 min. Sections were washed five times for 5 min/wash and then mounted on slides and covered using VECTASHIELD® Mounting medium (Vector laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). A fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Carl Zeiss MicroImmaging Inc, NY, USA) was used to identify c-Fos immunopositive neurons, by quantifying intensities that were at least two times higher than that of the average value of background (sections stained without second antibody) using a computer-associated image analyzer (Axiovision Rel. 4.6).

2.9. [3H]-Dopamine release

The methods of Salminen et al, 2007 were followed. Briefly, freshly dissected striata were homogenized by hand in 0.5 ml ice-cold isotonic sucrose buffered with HEPES (5 mM, pH 7.4). After dilution to 2 ml, 0.5 ml aliquots were centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 20 min at 4°C. Aliquots were stored on ice as pellets (maximum time 3 hours) until re-suspension in uptake buffer [128 mM NaCl, 2.4 mM KCl, 3.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM glucose, 10 µM pargyline, 1 mM ascorbic acid)] and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. [3H]-DA (0.1 µM) and DFP (10 µM) were added and incubation continued for 5 min longer. At this point 8 aliquots of the crude synaptosome suspension (80 µl each) were placed on filters on superfusion platforms and superfused with buffer (uptake buffer with 0.1% BSA, 1 µM atropine and 1 µM nomifensine added) at 22°C for 10 min before stimulation with various concentrations of agonist or agonist + DHβE in buffer for 20s followed by buffer. Alternate aliquots were superfused with buffer alone for 7 min, followed by buffer containing α-CtxMII (50 nM) for 3 min to block activity of α6β2*-nAChRs and, subsequently, the same stimulation protocol. Fractions were collected (10s each) into 96-well plates for ∼1 min before stimulation, during stimulation and ∼ 3 min following stimulation using a Gilson FC204 fraction collector (Middletown, WI). After addition of Optiphase Supermix scintillation cocktail (0.15 ml/well) radioactivity was determined using a 1450 MicroBeta Trilux counter (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences-Wallac Oy, Turku, Finland). Data were expressed as units of DA release [summed (cpm – baseline cpm)/(baseline cpm)] for fractions 10% or more above baseline.

2.10. Data Analysis

Behavioral, immunohistochemical and DA release data were analyzed with t-test, one or two-way ANOVA with repeated measures as indicated. Post-hoc analysis was done using Bonferroni post-hoc tests. Data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism 5 software (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). DA release data were analyzed by curve-fitting using SigmaPlot 8.0 (Jandel Scientific, San Raphael, CA).

3. Results

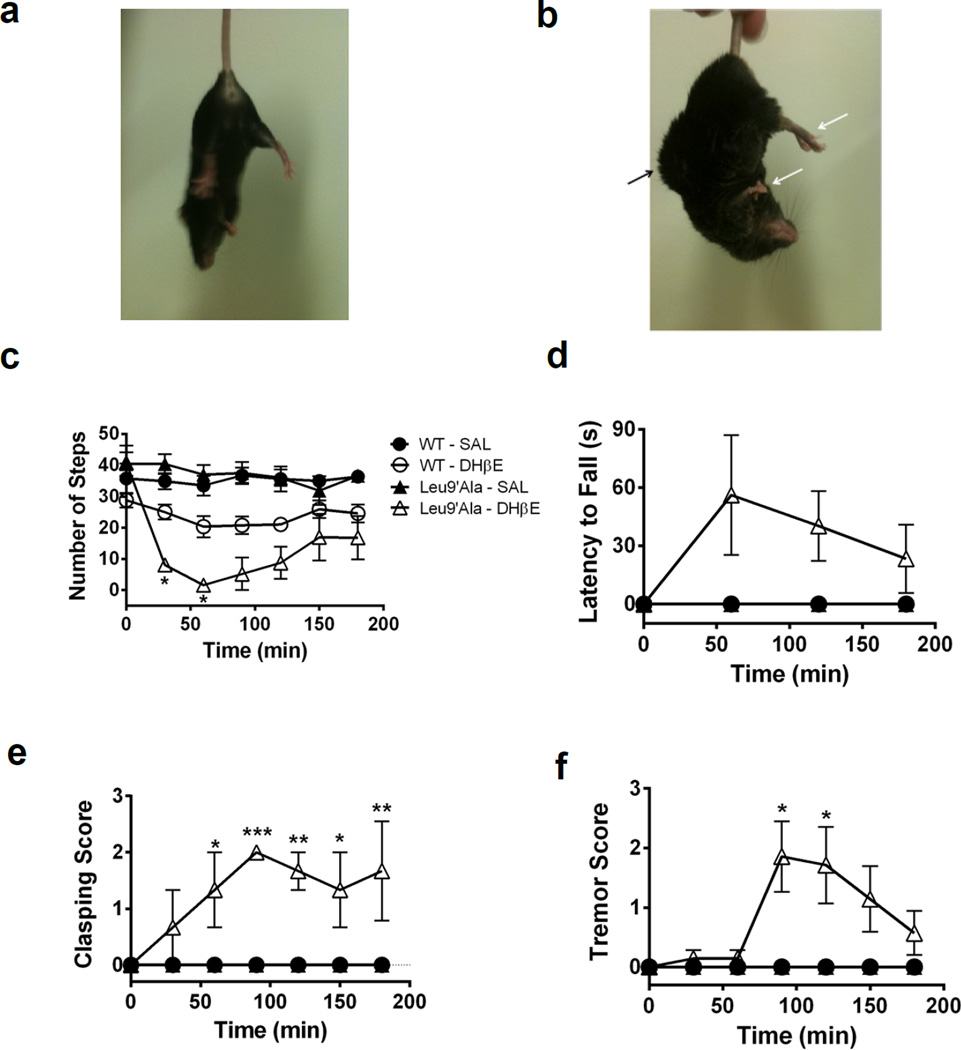

Previous studies indicate that BAC transgenic mice expressing agonist hypersensitive α6* nAChRs are hyperactive and that hyperactivity is abolished with genetic deletion of α4 subunit expression (Drenan et al., 2010). To test the hypothesis that Leu9′Ala mice, which harbor a similar mutation in the α4 subunit rendering α4* nAChR hypersensitive to agonist, are hyperactive, we measured baseline locomotor activity of WT and homozygous Leu9′Ala mice. Locomotor activity did not significantly differ between genotype (data not shown). To test the hypothesis that motor output in Leu9′Ala mice was more sensitive to endogenous ACh compared to WT, we challenged Leu9′Ala mice and their WT littermates with the competitive β2* nAChR antagonist, DHβE and motor behaviors such as akinesia, catalepsy, clasping, tremor (Figure 1) and locomotor activity (Figure 2) were measured. Much like the DA 2 receptor (D2R) agonist, quinpirole (Zhao-Shea et al., 2010), DHβE elicited a profound abnormal motor phenotype in Leu9′Ala mice compared to WT. Figure 1, depicts WT and homozygous Leu9′Ala mice 90 min after an i.p. injection of saline or DHβE (3 mg/kg in WT and 1 mg/kg in Leu9′Ala, respectively). DHβE had little effect in WT mice (Fig. 1a), but induced postural abnormalities, such as curvature of the back and tail and clasping of the limbs in Leu9′Ala mice (indicated by arrows, Fig. 1b). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA of akinesia (Fig. 1c) after DHβE in WT and Leu9′Ala mice revealed a significant effect of time (F6,72 = 16.02, p<0.0001) but not genotype and a significant interaction between genotype and time (F6,72= 6.84, p<0.0001). Post-hoc analysis indicated DHβE significantly reduced number of forelimb steps forward in Leu9′Ala compared with WT mice at 30 min (p<0.05) and 60 min (p<0.05) post-injection. Comparison of the cataleptic effect of DHβE in WT and Leu9′Ala mice (Fig. 1d), analyzed by a two-way repeated measures ANOVA, indicated a significant effect of genotype (F1,36=7.42, p<0.01) but not time nor an interaction. Analysis of clasping (Fig. 1e), by two-way repeated measures ANOVA, indicated a significant effect of genotype (F1,6 = 25.87, p<0.001), time (F6,36 = 3.67, p<0.01), and interaction between genotype and time (F6,36 = 3.67, p<0.001). Further post-hoc analysis revealed that DHβE induced significant increases in clasping in Leu9′Ala compared to WT mice at 60 (p<0.05), 90 (p<0.001), 120 (p<0.01), 150 (p<0.05), and 180 (p<0.01) min. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA of DHβE-induced tremors (Figure 1f) in Leu9′Ala and WT mice revealed a significant effect of genotype (F1,9 = 5.16, p<0.05), time (F6,54 = 2.53, p<0.05), and interaction between genotype and time (F6,54 = 2.53, p<0.05). Post-hoc tests indicated a significant increase in tremor at 90 and 120 min post DHβE injection in Leu9′Ala mice compared to WT. There was no difference between WT and Leu9′Ala mice after a saline injection in any of the motor behavior assays.

Figure 1.

DHβE induces motor abnormalities in Leu9’Ala mice. a) Representative pictures of the phenotypic effect induced by DHβE (1 mg/kg, i.p.) 90 minutes after injection in a) WT and b) Leu9’Ala homozygous mice. Arrows highlight hind limb rigidity, arched back, and curled tail in Leu9’Ala mice. c-f) Motor symptoms were characterized every 30 min for 180 min in WT and Leu9’Ala mice immediately following an i.p. challenge of 3 or 1 mg/kg DHβE, respectively. Effects of saline injection are also shown (n = 4/genotype). c) Akinesia: Number of forelimb steps forward were counted for 30 seconds (WT: n=4, Leu9’Ala: n=7 Leu9’Ala). d) Catalepsy: Latency for forelimbs to fall off a raised bar for 2 minutes was recorded (WT: n=5, Leu9’Ala: n=7). e) Clasping of hind limbs during a 10 second period was measured: 0 = hind limbs spread wide apart, 1 = hind limbs are 25% closed, 2 = hind limbs are 50% closed, 3 = hind limbs are 75% closed with some clasping, 4 = constant clasping. (WT: n=5, Leu9’Ala: n=3). f) Tremor score: 0 = no tremor, 1 = isolated twitches, 2 = tremor with periods of calm, 3 = constant tremor (WT: n=4, Leu9’Ala: n=7). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001

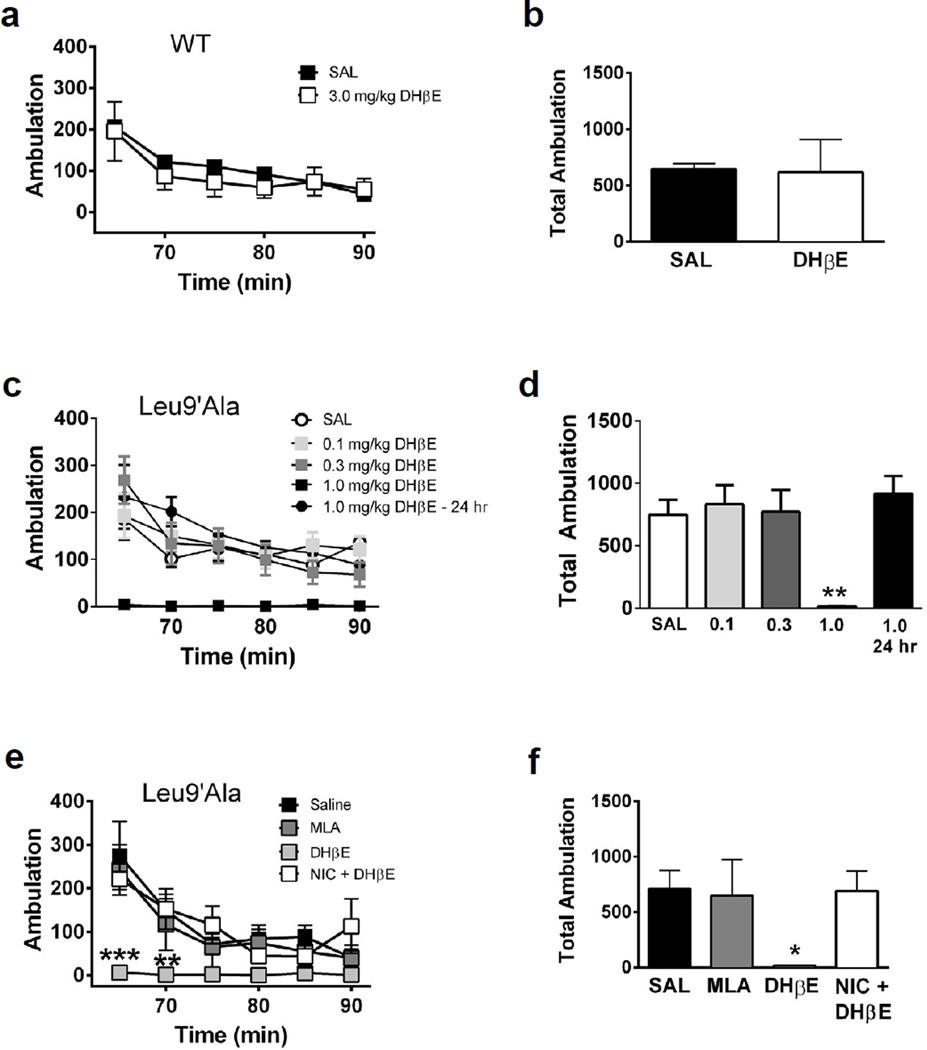

Figure 2.

DHβE induces hypolocomotion in Leu9’Ala mice. a) WT mice were placed into novel cages 60 minutes after saline (i.p., n=4) or DHβE challenge (3 mg/kg, i.p, n=4) and locomotor activity was measured for 30 minutes. Each data point represents the 5 min sum of ambulatory activity. b) Bar graphs represent total ambulation during 30 min of locomotor activity in WT mice measured in panel a. c) Locomotor activity in homozygous Leu9’Ala mice 60 min after saline (i.p., n=4), 60 min after DHβE (0.1–1 mg/kg, i.p., n=4), and 24 hrs after DHβE (1 mg/kg, i.p, n=4). d) Total ambulation was quantified for each condition as in panel b. e) Saline (i.p., n=4), MLA (10 mg/kg, i.p., n=4), DHβE (1 mg/kg, i.p., n=4), and NIC (0.1 mg/kg, i.p.) 5 minutes before DHβE (1 mg/kg, i.p., n=4) was administered to Leu9’Ala mice and locomotor activity was measure 60 min later. f) Quantification of total ambulation in Leu9’Ala mice. *p<0.05 and **p < 0.01

To test the effects of blocking α4* nAChRs on locomotion (Figure 2), saline (i.p.) or DHβE was administered to WT (3 mg/kg, i.p., Fig. 2a, b) and Leu9′Ala mice (0.1, 0.3, 1 mg/kg, and 24 hr post 1 mg/kg, i.p., Fig. 2c, d) and locomotor activity was recorded 60 min post-injection. DHβE did not significantly alter the time course of locomotor activity or total ambulation over 30 min in WT mice (Fig. 2a, b) compared to saline injection. However, DHβE significantly reduced Leu9′Ala locomotor activity compared to saline (Fig. 2c, d). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of drug treatment (F4,22 = 7.53, p<0.001), time (F5,110 = 15.95, p<0.0001) and a significant drug treatment × time interaction (F20,110 = 2.74, p<0.001). Interestingly, locomotor activity returned to baseline levels 24 hr after DHβE challenge indicating the effects of DHβE in Leu9′Ala mice were reversible. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of DHβE in total ambulation in Leu9′Ala mice (Fig. 2d) (F2,10 = 14.51, p<0.01). Post-hoc analysis indicated that total locomotor activity after DHβE injection was significantly lower compared to saline (p<0.01) and 24 hr post DHβE challenge (p<0.01). Additionally, locomotor activity was unaffected by systemic administration of hexamethonium (1 mg/kg, i.p.), a nAChR antagonist which fails to cross the blood brain barrier, indicating that DHβE-induced motor dysfunction in Leu9′Ala is mediated by neuronal nAChRs (data not shown). MLA (10 mg/kg, i.p. Fig. 2e and 2f), an α7 nAChR antagonist, had little effect on locomotor activity in Leu9′Ala mice compared to saline, indicating that the DHβE-induced hypolocomotion was likely a result of blocking α4β2* nAChRs. To test the hypothesis that DHβE is, in fact, acting as a competitive antagonist at α4β2* nAChRs, we injected Leu9′Ala mice with nicotine (0.1 mg/kg, i.p.) 5 min prior to challenge with DHβE (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and measured locomotor activity 1 hr post injection. Interestingly, nicotine (0.1 mg/kg, i.p.) prevented DHβE-induced hypolocomotion in Leu9′Ala mice (Fig. 2e) indicating that the DHβE phenotype is specifically elicited by blockade of nAChRs.

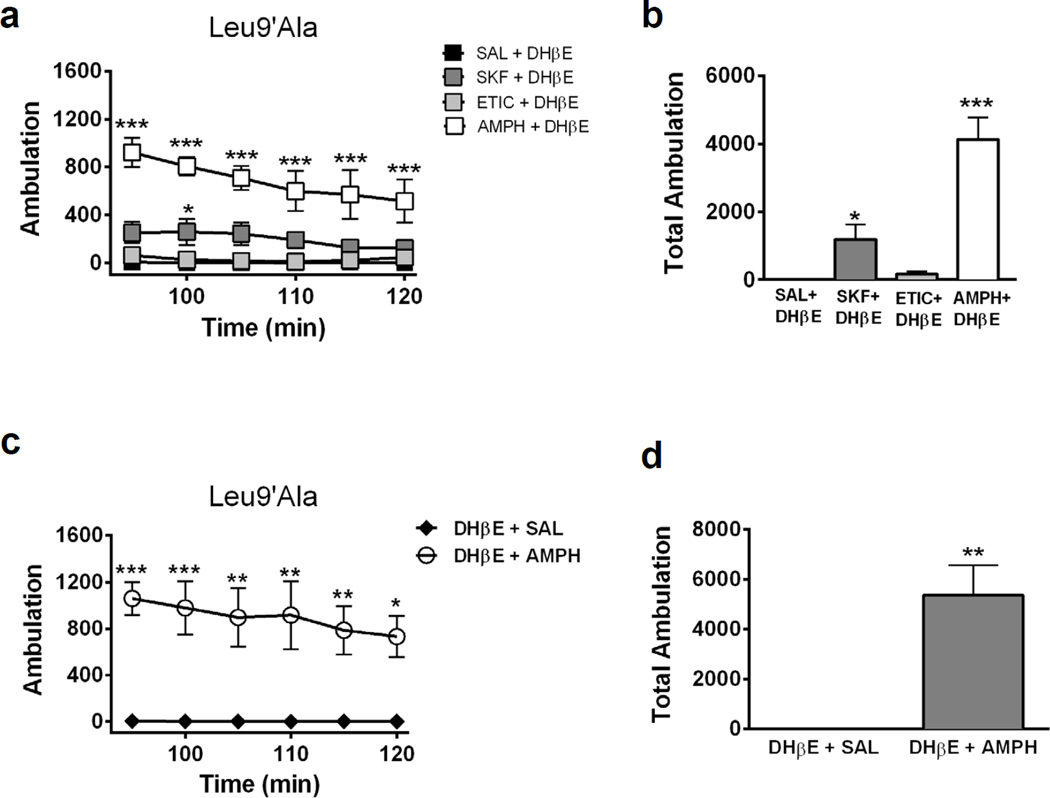

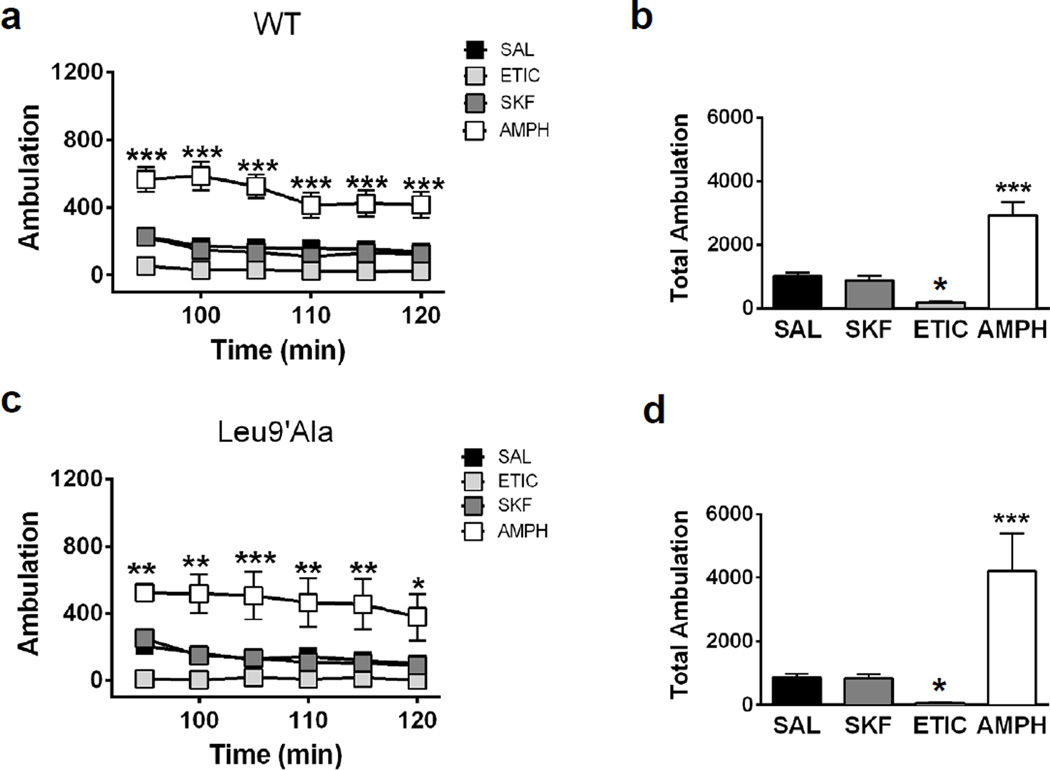

DHβE induced motor deficits in Leu9′Ala mice through blockade of neuronal nAChRs via a CNS-specific mechanism, raising the possibility that DHβE is blocking α4* nAChRs in the basal ganglia. Importantly, α4* nAChRs are robustly expressed in DAergic neuron soma and terminals of the substantia nigra pars compacta where they modulate DA release in dorsal ST (Salminen et al., 2004). Thus, antagonizing these receptors could decrease DA release and elicit the observed hypolocomotor phenotype. To test a potential involvement of DA, Leu9′Ala mice were pre-injected with SKF82958, a D1R agonist (1 mg/kg, i.p), eticlopride, (1 mg/kg, i.p.), a D2R antagonist, or the dopamine transporter competitive substrate, amphetamine (5 mg/kg, i.p.), 5 minutes prior to a DHβE challenge (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and locomotor activity was measured 90 min later (Fig. 3a, b). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of preinjection (F3,17 = 31.43, p<0.0001), time (F5, 85 = 5.21, p<0.001) and significant interaction (F15, 85 = 2.09, p<0.05). Post-hoc analysis indicated amphetamine and SKF82958 significantly increased locomotor activity compared to DHβE alone (Figure 3a). A one-way ANOVA of average total ambulation (Figure 3b) indicated a significant effect of drug pre-injection (F3,14 = 25.77, p<0.001) and post-hoc analysis revealed that amphetamine (p<0.001) and SKF82958 (p<0.05) significantly increased locomotor activity compared to DHβE alone suggesting increasing DA release in striatum or activating D1Rs is sufficient to prevent DHβE-induced hypolocomotion in Leu9′Ala mice. Although statistical analysis of eticlopride did not indicate a significant difference, there was a partial block of hypolocomotor activity indicated by increased locomotor activity counts above zero. In addition, all DA signaling compounds prevented rigidity (data not shown). To test if increasing DAergic signaling could rescue DHβE-induced hypolocomotion in Leu9′Ala mice, we challenged Leu9′Ala mice with DHβE and administered saline or amphetamine 15 min after the initial antagonist injection (Fig. 3c, d). Two-way repeated measure ANOVA revealed a significant effect of post-injection (F1,6 = 19.91, p < 0.01) but not time. Post-hoc analysis indicated an amphetamine post-injection significantly increased activity compared to saline at each time point. Average total locomotor activity was also significantly increased after an amphetamine post-injection compared to saline (t6 = 4.46, p < 0.01). We also tested the action of SKF82958, eticlopride, or amphetamine alone in WT (Fig. 4a and b) and Leu9′Ala (Fig. 4e and f) mice in the absence of DHβE. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA of drug treatment over time in WT mice (Fig. 4a) revealed a significant main effect of drug treatment (F3,20 = 26.18, p<0.0001), time (F5,100 = 16.25, p<0.001) and a significant interaction between drug treatment and time (F15,100 = 3.42, p<0.001). Post-hoc analysis indicated a significant effect of amphetamine at various time points. One-way ANOVA indicated that there was a significant effect of drug treatment (F3,23 = 26.18, p<0.0001) on total locomotor activity summed over 30 min. Further post-hoc analysis revealed a significant increase in locomotor activity after amphetamine (p<0.001), a significant decrease after eticlopride (p<0.05), but no difference after SKF82958 compared to a saline injection. These drugs had similar effects in Leu9′Ala mice (Fig. 4c and d, a significant main effect of drug treatment, F3,20 = 9.98, p<0.001 and time, F5,100 = 6.94, p<0.001). There was also a significant effect of drug treatment when analyzing total locomotor activity over 30 min (Fig. 4d) (F3, 23 = 9.781, p<0.001, One-Way ANOVA) and post-hoc analysis revealed amphetamine significantly increased locomotor activity (p<0.01), while eticlopride decreased locomotor activity (p < 0.05). Effects of DA signaling did not differ between genotypes (two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of drug treatment (F3,40 = 22.66, p<0.0001) but not genotype nor a significant interaction). Taken together these data indicate that prevention of DHβE-induced hypolocomotion in Leu9′Ala mice was not an artifact of baseline hypersensitivity to DA signaling compounds in these animals.

Figure 3.

Pharmacologically targeting DAergic signaling prevents DHβE-induced hypolocomotion in Leu9’Ala mice. a) Homozygous Leu9’Ala mice were placed into novel cages 90 min after administration of DHβE (1 mg/kg, i.p.) after preinjection of saline (SAL, 1 mg/kg; i.p.; n=4), SKF-38393 (SKF, 1 mg/kg, i.p., n=4), eticlopride (ETIC, 1 mg/kg, i.p., n=4), or amphetamine (AMPH, 5 mg/kg, i.p., n=4) and activity was measured for 30 min. Each data point represents the 5 min sum of ambulation at a given time point. b) Averaged 30 min sum of activity was quantified. c) Homozygous Leu9’Ala mice were challenged with DHβE (1 mg/kg, i.p.) followed by a saline (n = 4) or amphetamine (5 mg/kg, i.p., n = 4) injection 15 min later. Mice were placed into activity cages 90 min after the DHβE injection when motor deficits were at their peak. d) Averaged 30 min sum of activity was quantified. *p<0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

DAergic signaling is not altered in Leu9’Ala mice compared to WT mice. Locomotor activity was measure 90 minutes after administration of saline (i.p., n=6), SKF (1 mg/kg, i.p., n=6), ETIC (1 mg/kg, i.p., n=6), and AMPH (5 mg/kg, i.p., n=6) in a) WT and c) Leu9’Ala. Averaged total ambulation for b) WT and d) Leu9’Ala mice after challenge of drugs from panel a and c, respectively as in Figure 3. *p<0.05 and ***p<0.001

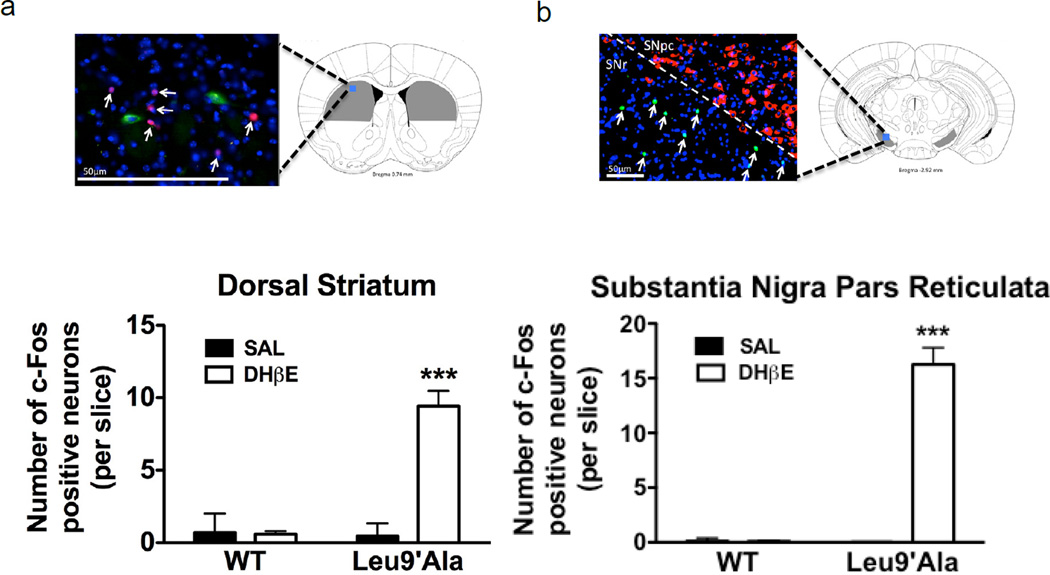

Targeting DA receptor signaling through pharmacology was able to fully or partially alleviate DHβE-induced hypolocomotion in Leu9′Ala mice, suggesting a role for the direct and indirect basal ganglia pathways. To test this hypothesis, we used immunohistochemistry to examine c-Fos expression as a marker for neuronal activation in the dorsal ST (Fig. 5a) and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) (Fig. 5b) of WT and Leu9′Ala mice in response to DHβE. For this experiment, WT and Leu9′Ala mice were challenged with saline (i.p.) or DHβE (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and the dorsal ST was immunolabled for c-Fos (a transcription factor and marker of neuronal activation (Cole et al., 1989), red), ChAT (cholinergic acetyltransferase to identify cholinergic neurons, green) and the nucleic acid stain, DAPI (blue). The SNr was stained for c-Fos (green), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, to identify DAergic neurons in the SN pars compacta, red), and DAPI (blue). Figure 5a and b depict micrographs illustrating c-Fos expression after DHβE injection in Leu9′Ala Mice. The total number of c-Fos immuno-positive neurons was counted in each brain region and analyzed by a two-way ANOVA. In the dorsal ST (Fig. 4a), there was a significant effect of drug treatment (F1,108 =20.68, p<0.001), genotype (F1,108 = 19.46, p<0.001), and a significant interaction between drug treatment and genotype (F1,108 = 20.78, p<0.001). Post-hoc analysis indicated that there was a significant increase of c-Fos immuno-positive neurons in the dorsal ST in Leu9′Ala mice after DHβE (p<0.001) compared to WT. In the SNr there was a significant effect of drug treatment (F1,52 = 31.44, p<0.001), genotype (F1,52 = 30.88, p<0.001), and a significant interaction between drug treatment and genotype (F1,52 = 31.44, p<0.001). Post-hoc analysis indicated that there was a significant increase of c-Fos immuno-positive neurons in the dorsal ST in Leu9′Ala mice after DHβE (p<0.001) compared to WT. c-Fos expression did not colocalize with ChAT immuno-positive (i.e. cholinergic) neurons in ST or TH immune-positive neurons in SNpc indicating that neurons activated by DHβE were likely GABAergic. DHβE did not significantly increase c-Fos expression in WT mice compared to saline in either brain region. Together these data indicate that there is activation of neurons within the motor pathway, specifically of the indirect pathway which controls/reduces movement in Leu9′Ala mice challenged with DHβE, indicated by activation of both dorsal ST and SNr (Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011).

Figure 5.

Neuronal activation by DHβE in the dorsal ST and SNr. WT and homozygous Leu9’Ala were perfused 150 minutes after a challenge of saline (i.p.) or DHβE (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and coronal sections (20 µm thick) from the dorsal ST or SNr were isolated and immunolabeled to detect c-Fos and ChAT expression (ST) or TH expression (SNr). a) Top, representative brain atlas picture of illustrating ST region analyzed. An immuno-labeled coronal section from Leu9’Ala mice after injection with DHβE depicting c-Fos (red) and ChAT (green) expression is shown. DAPI stained nuclei are labeled blue. Bottom, number of c-Fos immuno-positive neurons/slice in WT and Leu9’Ala mice after saline or DHβE injection (3 mice/ treatment, 10 slices/mouse). b) Top, representative brain atlas picture of illustrating SNr region analyzed. An immunolabeled coronal section from Leu9’Ala mice after injection with DHβE depicting c-Fos (green) and TH (red) expression is shown. DAPI stained nuclei are labeled blue, c) Bottom, quantification of c-Fos immuno-positive neurons in WT and Leu9’Ala after saline or DHβE (3 mice/ treatment, 10 slices/mouse). ***p<0.001

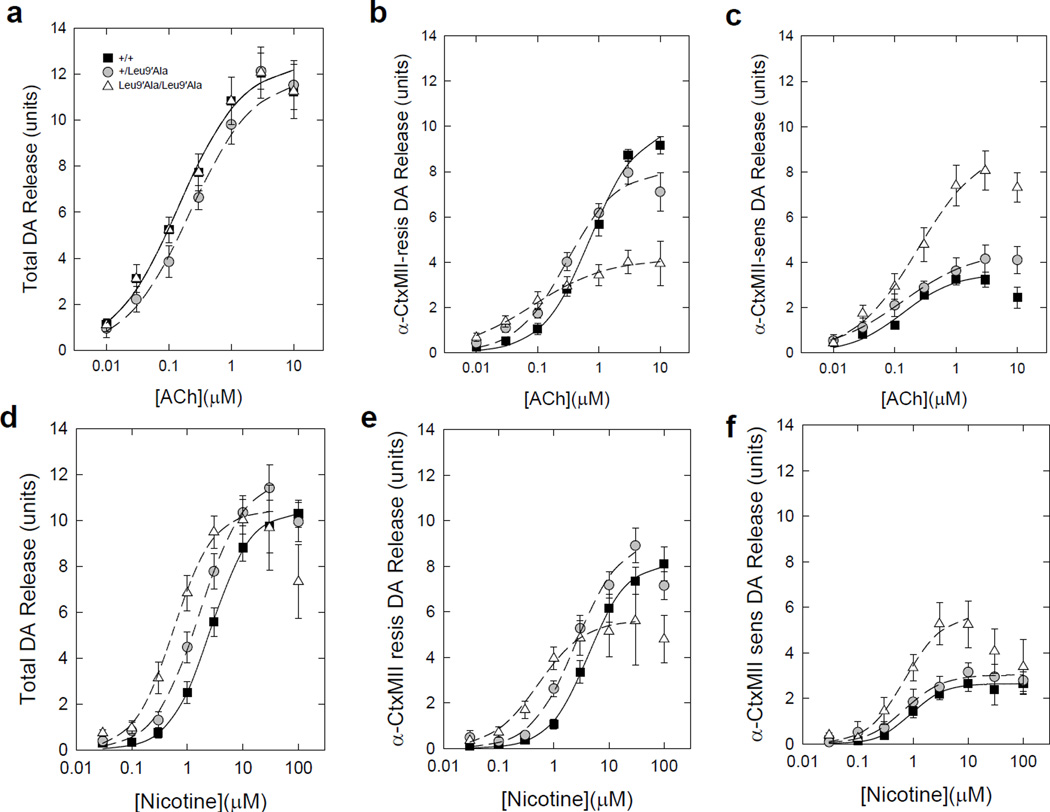

To test the hypothesis that DA release in ST from Leu9′Ala mice is more sensitive to nicotinic agonists compared to WT, we compared ACh-evoked and nicotine-evoked DA release from ST synaptosomes of all three genotypes. Both ACh- and nicotine-stimulated DA release from striatal synaptosomes was concentration-dependent in all three genotypes (Fig. 6). The total concentration-response relationship for ACh-mediated DA release in Leu9′Ala heterozygous and homozygous was only slightly changed compared to WT synaptosomes with a small shift to lower EC50 values (Fig. 6a, Tables 1 and 2). A somewhat larger leftward shift was seen in Leu9′Ala heterozygous and homozygous synaptosomes compared to WT using nicotine as agonist (Fig. 6d, Tables 1 and 2). To determine the relative contribution of α4* versus α6* nAChRs on agonist-evoked DA release, we measured release in the presence of a-conotoxin MII (α-CtxMII), an α6* nAChR selective antagonist (Fig. 6b and 6e). The α-CtxMII-resistant fraction of DA release (mediated by α4β2*-nAChR) was more sensitive to both ACh and nicotine in heterozygous and homozygous Leu9′Ala synaptosomes compared to those from WT mice (Fig. 6b, 6e and Table 1) and maximum release was significantly decreased (Figure 6b, 6e and Table 2). In contrast, the α-CtxMII-sensitive component of DA release (mediated by α6β2*-nAChR) in Leu9′Ala homozygous synaptosomes was not significantly more sensitive to either agonist compared to heterozygous or WT synaptosomes (Fig. 6c, 6f and Table 1). However, Rmax was significantly increased for the α-CtxMII-sensitive component of nicotine stimulated DA release (Fig. 6c, 6f and Table 2). Together, these data indicate that α4(non-α6)* nAChRs in striatal synaptosomes are hypersensitive to agonist in Leu9′Ala heterozygous and homozygous mice.

Figure 6.

Concentration response curves for ACh- and nicotine-stimulated [3H]-DA release from striatal synaptosomes. a) Total ACh-stimulated [3H]-DA release, b) α4β2*-nAChR mediated [3H]-DA release measured in the presence of α-CtxMII (50 nM) and c) α6β2*-nAChR-mediated [3H]-DA release determined by difference (a – b). Data represent means ± sem for n=9 +/+, n=8 +/Leu9′Ala and n=10 Leu9′Ala/Leu9′Ala mice. d–f) Analogous curves for nicotine-stimulated response. Data represent means ± sem for n=8 mice each genotype.

Table 1.

Comparison of EC50 values for DA release

| Genotype | EC50 (mM) for Total DA release |

EC50 (mM) for α4β2-mediated α-CtxMII- resistant |

EC50 (mM) for α6β2-mediated α-CtxMII-sensitive |

|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ ACh | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 0.72 ± 0.11 | 0.14 ± 0.04 |

| +/Leu9′Ala ACh | 0.22 ± 0.07 * | 0.30 ± 0.06 * | 0.13 ± 0.11 |

| Leu9′Ala/Leu9′Ala ACh | 0.14 ± 0.05 * | 0.08 ± 0.05 *+ | 0.24 ± 0.15 |

| +/+ Nic | 2.59 ± 0.13 | 4.16 ± 0.33 | 0.91 ± 0.12 |

| +/Leu9′Ala Nic | 1.66 ± 0.15 * | 1.74 ± 0.36 * | 0.71 ± 0.16 |

| Leu9′Ala/Leu9′Ala Nic | 0.57 ± 0.10 *+ | 0.52 ± 0.12 *+ | 0.73 ± 0.24 |

Significantly different from +/+

Significantly different from +/Leu9′Ala

Table 2.

Comparison of Rmax values for ACh and nicotine

| Genotype | Rmax (units) Total DA release |

Rmax (units) α4β2-mediated α-CtxMII- resistant |

Rmax (units) α6β2-mediated α-CtxMII-sensitive |

|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ ACh | 12.76 ± 0.56 | 10.76 ± 0.56 | 3.53 ± 0.30 |

| +/Leu9′Ala ACh | 11.94 ± 1.02 | 8.06 ± 0.52 * | 4.55 ± 0.97 |

| Leu9′Ala/Leu9′Ala ACh | 12.51 ± 1.07 | 4.16 ± 0.06 *+ | 9.22 ± 1.68 *+ |

| +/+ Nic | 10.40 ± 0.13 | 8.16 ± 0.19 | 2.65 ± 0.08 |

| +/Leu9′Ala Nic | 11.90 ± 0.33 * | 9.19 ± 0.57 | 3.04 ± 0.13 |

| Leu9′Ala/Leu9′Ala Nic | 10.50 ± 0.50 *+ | 5.66 ± 0.41 *+ | 5.72 ± 0.68 *+ |

Units are (cpm released- baseline cpm)/(baseline cpm).

Significantly different from +/+

Significantly different from +/Leu9′Ala

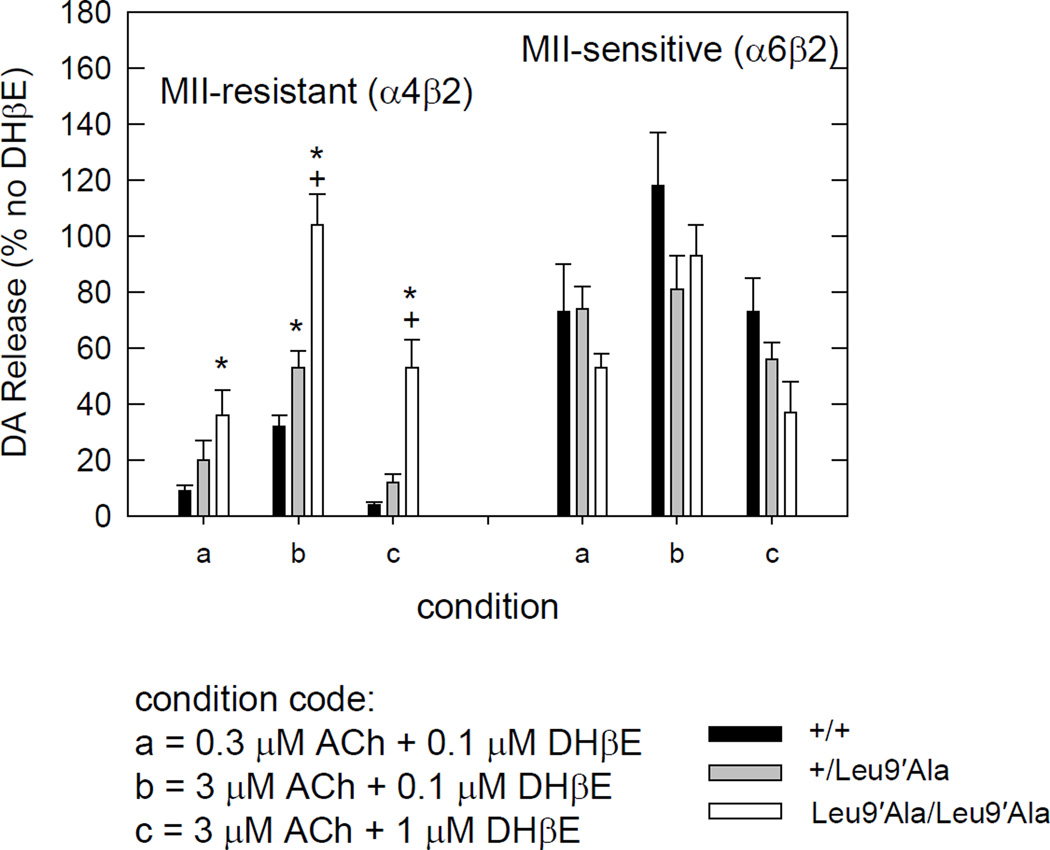

As blockade of α4β2* nAChRs using DHβE elicited a hypolocomotor phenotype in Leu9′Ala mice, we next measured the inhibitory-response relationship for DHβE on agonist evoked DA release in Leu9′Ala and WT synaptosomes (Fig. 7) as well as determined Ki values for each genotype for DHβE inhibition of ACh-evoked release (Table 3). At α4(non-α6)*-nAChRs as well as at α6*-nAChRs, DHβE dose-dependently inhibited DA release evoked by either ACh (Fig. 7) or nicotine (data not shown). Interestingly, evoked DA release at α4(non-α6)* nAChR in Leu9′Ala homozygous synaptosomes was significantly more resistant to DHβE than the WT or heterozygous Leu9’Ala under equivalent agonist activation (Fig. 7 and Table 3). This effect is largely caused by a decrease in EC50 value (∼9-fold) at α4*-nAChR with some increase (∼2-fold) in Ki value for DHbE (Table 3). EC50 values for ACh at α6*-nAChR (Table 1) as well as Ki values for DHβE at α6*-nAChR (Table 3) were unchanged by the α4Leu9′Ala mutation despite the known existence of the α4α6β3β2-nAChR subtype in WT mice in DAergic neurons (Salminen et al., 2004, Salminen et al., 2007).

Figure 7.

Effect of DHβE on ACh-stimulated [3H]-DA release. The α-CtxMII-resistant (α4β2*-nAChR-mediated) response in the homozygous Leu9′Ala is significantly less inhibited by DHβE (* different from WT) under the three conditions tested. The heterozygous Leu9′Ala were different only for condition b. No differences with genotype were seen for the effect of DHβE on the α-CtxMII-sensitive (α6β2*-nAChR mediated) portion of the response. All data expressed as % response in the absence of DHβE. Data represent means ± sem for n=5 +/+, n=4 +/Leu9′Ala and n=3 Leu9′Ala/Leu9′Ala mice.

Table 3.

Comparison of IC50 and Ki values (nM) for DHβE blockade of ACh-stimulated DA release

| Genotype | IC50 (nM) α4β2-mediated α-CtxMII- resistant using 3 µM ACh |

IC50 (nM) α4β2-mediated α-CtxMII- resistant using 0.3 µM ACh |

IC50 (nM) α6β2-mediated α-CtxMII- sensitive using 3 µM ACh |

IC50 (nM) α6β2-mediated α-CtxMII- sensitive using 0.3 µM ACh |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | 60 ± 4 | 11 ± 1 | 1848 ± 848 | 238 ± 169 |

| +/Leu9’Ala | 95 ± 23 | 12 ± 4 | 1175 ± 358 | 180 ± 49 |

| Leu9’Ala/Leu9’Ala | 1175 ± 412 *+ | 68 ± 12 *+ | 714 ± 140 | 118 ± 35 |

| Ki (nM) α4β2-mediated α-CtxMII- resistant using 3 µM ACh |

Ki (nM) α4β2-mediated α-CtxMII- resistant using 0.3 µM ACh |

Ki (nM) α6β2-mediated α-CtxMII- sensitive using 3 µM ACh |

Ki (nM) α6β2-mediated α-CtxMII- sensitive using 0.3 µM ACh |

|

| +/+ | 12 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 83 ± 38 | 77 ± 55 |

| +/Leu9’Ala | 9 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | 42 ± 13 | 49 ± 13 |

| Leu9Ala/Leu9Ala | 31 ± 11 *+ | 14 ± 3 *+ | 53 ± 10 | 39 ± 12 |

significantly different from +/+.

significantly different from +/Leu9′Ala.

Notes: Data collected at 3 µM ACh from 5 WT, 4 HET, 2 HOM mice and at 0.3 uM ACh from 5 WT, 4 HET, 3 HOM mice. For each, 4–5 concentrations of DHβE were assayed, 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 µM with and without 50 nM αCtxMII. Data was curve fit from all individual points for each ACh concentration using the single exponential decay equation: f=a*exp(-b*x), where a=uninhibited release, b=decay constant and 0.693/b=IC50 value. The Ki values were calculated from the equation: Ki=IC50/(1+[ACh]/EC50) where EC50 values are taken from Table 1. By ANOVA, using all determinations of Ki, the resistant Ki for mutant is significantly different than WT.

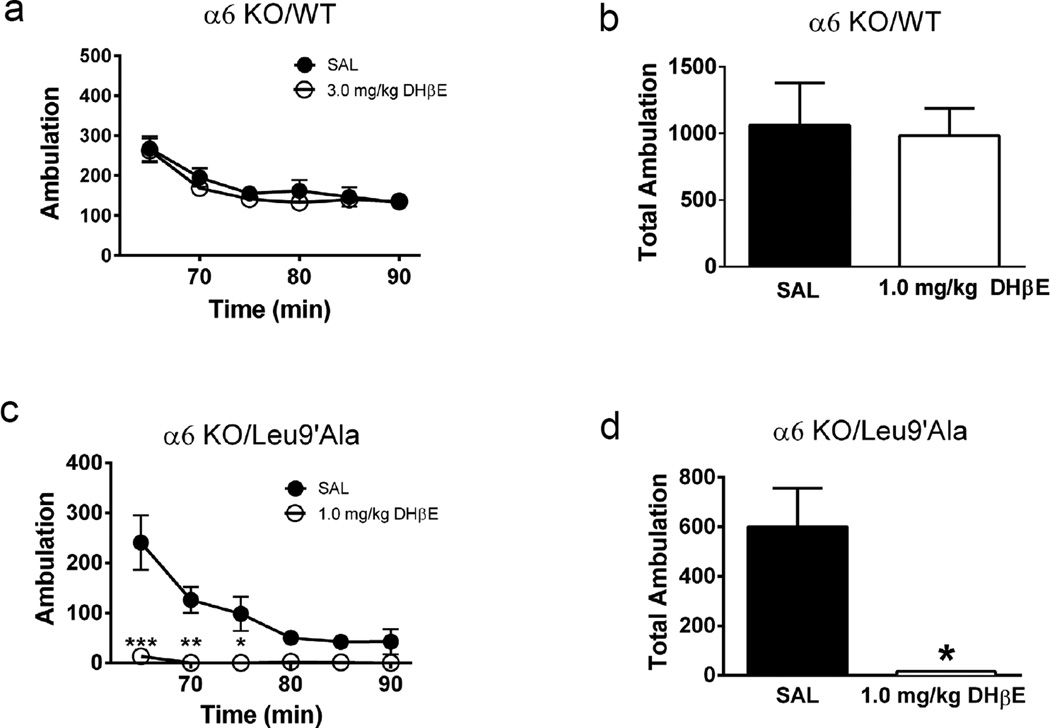

To determine the contribution of α6*-nAChRs to the DHβE-induced phenotype in Leu9′Ala mice, we crossed Leu9′Ala mice to α6 KO animals and measured locomotor responses after antagonist treatment (Fig. 8). In α6 KO mice on an a4 WT background, DHβE did not significantly modulate activity compared to saline (Figure 8a, b). Interestingly, DHβE significantly reduced locomotor activity in Leu9′Ala homozygous mice on an α6 KO background compared to saline and resulted in a motor phenotype indistinguishable from Leu9′Ala mice on a WT background (Fig. 8b, c).

Figure 8.

α4(non-α6)β2* nAChRs mediate effect of DHβE in Leu9′Ala mice. a) α6KO/WT mice were placed into novel cages 60 min after saline or DHβE challenge (1 mg/kg, i.p) and locomotor activity was measured for 30 minutes. Each data point represents the 5 min sum of ambulatory activity. b) Average summed ambulation over 30 min from panel a. c) α6KO/Leu9′Ala mice were placed into novel cages 60 min after saline or DHβE challenge (1 mg/kg, i.p) and locomotor activity was measured for 30 minutes. Each data point represents the 5 min sum of ambulatory activity. b) Bar graphs represent averaged total ambulation during 30 min of locomotor activity in WT mice measured in panel a. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001.

4. Discussion

4.1. Hypersensitive α4* nAChRs do not affect basal levels of locomotor activity

Previously, hyperactivity was reported in a BAC transgenic mouse line expressing hypersensitive α6* nAChRs, suggesting a functional role for this receptor subtype in baseline motor behavior (Drenan et al., 2008b). Hyperactivity in this mouse line was also dependent on expression of the α4 subunit as crossing the α6 hypersensitive line to an α4 KO mouse line abolished locomotor hyperactivity (Drenan et al., 2010). Interestingly, we observed no significant differences in baseline locomotor activity between Leu9′Ala and WT mice. Recently, Cohen et. al. reported hyperactivity in BAC α6* nAChRs was a consequence of α6* L9′S nAChR subunit copy number (Cohen et al., 2012). Mice with lower copy numbers were not hyperactive compared to those with higher copy numbers. Since Leu9′Ala α4 mice were generated via homologous recombination and only express two copies of the Leu9′Ala α4 nAChR subunit (Tapper et al., 2004), it is possible that hyperactivity would be observed in mice expressing additional copies of the mutant nAChR subunit gene. Alternatively, compensation may account for the lack of hyperactivity. Leu9′Ala mice developed with α4* nAChRs hypersensitive to ACh, therefore there may be compensatory nAChR receptor expression, replacement of nAChR subunits, or altered DA receptor expression. Indeed, α4* nAChR activity is down-regulated in homozygous Leu9′Ala thalamus and cortical synaptosomes compared to WT (Fonck et al., 2005). In addition, expression of α6* nAChRs is limited to Daergic nerve terminals (Drenan et al., 2008a); whereas α4* nAChRs are widely expressed in DAergic, GABAergic, and glutamatergic neurons within the nigrostriatal pathway (Champtiaux et al., 2003, Marubio et al., 2003, Wooltorton et al., 2003, Xiao et al., 2009). Lack of hyperactivity may be a consequence of α4* nAChR activity in non-DAergic neurons.

4.2. Antagonism of hypersensitive α4* nAChRs leads to motor deficits

Antagonism of α4* nAChRs in Leu9′Ala mice evoked robust, reversible parkinsonian-like symptoms characterized by hypoactivity, akinesia, catalepsy, and tremor. These symptoms have been previously shown to be associated with DA depletion. Therefore we hypothesize that the abnormal motor symptoms observed after blocking hypersensitive α4* nAChRs are an effect of low levels of DA in dorsal ST. Although absolute confirmation of our hypothesis requires measuring DA release in striatum in vivo, DHβE induced c-Fos expression in Leu9′Ala dorsal ST and SNpr suggests inactivation of the direct motor pathway and activation of the indirect motor pathway. Indeed, the motor phenotype was alleviated by 1) increasing DA release using amphetamine, 2) by increasing direct motor pathway activation directly through D1R agonism, or 3) by antagonizing D2Rs, thereby redirecting available DA to activate the direct pathway. DHβE had no measureable behavioral effect in WT mice potentially because blockade of WT α4* nAChRs may not reduce striatal DA concentrations sufficiently low enough to induce a measurable motor phenotype.

4.3. Effect of DHβE is independent of α6 subunit incorporation

Although α4* and α6* nAChRs are expressed in DAergic nerve terminals in striatum, their functional roles are not equal in this region. DA release in the ventral striatum, associated with reward based behaviors, is preferentially modulated by α6* and α4α6* nAChRs versus α4(non-α6)* nAChRs which preferentially modulate DA release in the dorsal ST, associated with movement (Salminen et al., 2007, Drenan et al., 2008b, Exley et al., 2008, Exley et al., 2011, Exley et al., 2012). Approximately 25 to 30% of agonist evoked [3H]dopamine release from dorsal ST synaptosomes is mediated by α6* nAChRs resulting in a potentially more robust role for α4* nAChRs in modulating dorsal ST DA release (Salminen et al., 2004). In addition, approximately 50 to 60% of terminally expressed α6* nAChRs also contain an α4 subunit, which increases the receptors’ sensitivity to ACh (Champtiaux et al., 2003, Marubio et al., 2003, Salminen et al., 2004, Salminen et al., 2007). Interestingly, the dose response relationship for agonist induced DA release in striatal synaptosomes was shifted to the left in Leu9′Ala mice compared to WT only for the α-CtxMII insensitive nAChR fraction indicating that α4(non-α6)* nAChRs were hypersensitive to agonist; whereas Rmax was increased in the α-CtxMII sensitive fraction indicating a compensatory increase in α6* nAChRs in Leu9′Ala synaptosomes. Knocking out the α6 subunit in hypersensitive α4* nAChR Leu9′Ala mice had no effect on the motor phenotype induced by DHβE suggesting that observed behaviors are caused solely by antagonism of α4(non-α6)* nAChRs. It was recently reported that regulation of DA release probability in the dorsal ST is dominated by α4α5* nAChRs and that incorporation of α5 is critical for functioning of DA release from terminal expressed α4* nAChRs (Exley et al., 2012). Incorporation of the α5 subunit into α4* nAChRs increases agonist sensitivity and also increases permeability to Ca++ (Ramirez-Latorre et al., 1996, Tapia et al., 2007) In striatal synaptosome preparations, α4α5* nAChRs are responsible for ∼70% DA release (Salminen et al., 2004). Additionally, these receptors are more resistant to desensitization (Grady et al., 2012). Thus it is likely that the DHβE-sensitive nAChRs responsible for the abnormal motor phenotype in Leu9′Ala mice also contain the α5 subunit. These receptors may regulate basal DA concentrations in dorsal ST.

4.4. Implications of nAChRs mediated DA release

The relationship between cholinergic and DAergic signaling in the striatum is complex. Cholinergic neurons are tonically active and pauses in their activity coincide with changes from a phasic to bursting activity in DA neurons which increase DA release for neuronal signaling encoding messages for reward, learning, and motor behaviors (Rice et al., 2011). Depleting endogenous ACh decreases electrically evoked DA release by 90%, highlighting the balance of ACh and DA (Zhou et al., 2001). Additionally, synchronous cholinergic activation can increase DA release via terminal nAChRs; a process independent of neuronal activity (Threlfell et al., 2012). In WT mice, DHβE blocked this increase in DA release revealing that α4β2* nAChRs mediate this response. Our model suggests that α4(non-α6)* nAChRs play a significant role in maintaining DA levels for normal movement behavior which may be, in part, regulated by this uncoupled terminal DA release. While the DHβE-induced phenotype in Leu9′Ala mice observed in our study is likely exaggerated due to the agonist hypersensitivity of α4* nAChRs in this mouse line, it nevertheless indicates the importance of these receptors on motor function. Motor output in normal functioning basal ganglia may not be affected by antagonism of these receptors most likely due to redundancy of DA modulatory mechanisms. However, under pathological conditions when a substantial number of DA neurons have degenerated, such as in Parkinson’s disease, targeting these receptors may have a larger impact on motor deficits and may be ideal candidates for therapeutic drugs.

Much like the phenotype described here, we previously reported that Leu9′Ala mice treated with a DA D2 receptor agonist, quinpirole, also develop reversible akinesia, rigidity, catalepsy, and tremor, (Zhao-Shea et al., 2010). Here we show that directly blocking α4* nAChRs in Leu9′Ala leads to a more severe phenotype. More precisely, quinpirole-treated Leu9′Ala homozygrous mice exhibit most closely resemble DHβE-treated Leu9′Ala heterozygous mice (data not shown); whereas DHβE-treated Leu9’Ala homozygous mice hypolocomotor dysfunction is more severe. Thus, it is possible that a functional interaction between D2Rs and α4* nAChRs on DA terminals occurs such that activation of D2Rs inhibits α4* nAChRs, potentially working in concert as a mechanism to regulate striatal DA levels (Quarta et al., 2006).

It is also possible these Leu9’Ala mice have altered connectivity of GABA interneurons that control activity of the direct and indirect pathways similar to that shown under low DA conditions, where 6-OHDA treatment and subsequent DA depletion led to an increase in connections between fast-spiking interneurons and indirect pathway neurons (Gittis et al., 2011, Gittis and Kreitzer, 2012). Such a change could alter the importance of ACh levels controlled by DA D2 receptors on cholinergic interneurons as well as activation of nAChRs on GABA interneurons. The result could be activation of indirect pathway neurons relative to the direct pathway upon decrease of ACh release or block of α4b2 nAChR.

We have shown that antagonism of hypersensitive Leu9′Ala α4* nAChRs in mice induces a robust, reversible motor phenotype, which can be prevented by targeting the DAergic system. α4(non-α6)* nAChRs play a major role in this response suggesting that these receptors may be critical for maintaining DA levels necessary for normal motor behavior. Together these data indicate α4(non-α6)* nAChRs in dorsal ST may represent therapeutic candidates for alleviating motor dysfunction.

Highlights.

-

-

Motor behavior was analyzed in agonist-hypersensitive mutant α4 nAChR knock-in mice.

-

-

Blocking α4* nAChRs elicited akinesia, rigidity, and tremor in these mice.

-

-

Motor impairment was prevented by nicotine and dopamine agonists

-

-

hypersensitive nAChRs on DA nerve terminals contained α4 but not α6 subunits

-

-

α4(non-α6) nAChRs in dorsal striatum modulate dopamine-related motor behaviors

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Bruce N. Cohen and Paul D. Gardner for helpful discussions and Dr. J. Michael McIntosh for α-conotoxin MII. This study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke award number NS059586 (ART), National Institute of Drug Abuse award numbers DA001394 (MJM), DA012242 (MJM) and DA019663 (MJM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Gotti C, Cordero-Erausquin M, David DJ, Przybylski C, Lena C, Clementi F, Moretti M, Rossi FM, Le Novere N, McIntosh JM, Gardier AM, Changeux JP. Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7820–7829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07820.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Han ZY, Bessis A, Rossi FM, Zoli M, Marubio L, McIntosh JM, Changeux JP. Distribution and pharmacology of alpha 6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors analyzed with mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1208–1217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01208.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen BN, Mackey ED, Grady SR, McKinney S, Patzlaff NE, Wageman CR, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ, Lester HA, Drenan RM. Nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms causing elevated dopamine release and abnormal locomotor behavior. Neuroscience. 2012;200:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole AJ, Saffen DW, Baraban JM, Worley PF. Rapid increase of an immediate early gene messenger RNA in hippocampal neurons by synaptic NMDA receptor activation. Nature. 1989;340:474–476. doi: 10.1038/340474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Grady SR, Steele AD, McKinney S, Patzlaff NE, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ, Miwa JM, Lester HA. Cholinergic modulation of locomotion and striatal dopamine release is mediated by alpha6alpha4* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9877–9889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2056-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, McClure-Begley T, McKinney S, Miwa JM, Bupp S, Heintz N, McIntosh JM, Bencherif M, Marks MJ, Lester HA. In vivo activation of midbrain dopamine neurons via sensitized, high-affinity alpha6* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuron. 2008a;60:123–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, McClure-Begley T, McKinney S, Miwa JM, Bupp S, Heintz N, McIntosh JM, Bencherif M, Marks MJ, Lester HA. In vivo activation of midbrain dopamine neurons via sensitized, high-affinity alpha 6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuron. 2008b;60:123–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Lester HA. Insights into the Neurobiology of the Nicotinic Cholinergic System and Nicotine Addiction from Mice Expressing Nicotinic Receptors Harboring Gain-of-Function Mutations. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:869–879. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.004671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwoskin LP, Wooters TE, Sumithran SP, Siripurapu KB, Joyce BM, Lockman PR, Manda VK, Ayers JT, Zhang Z, Deaciuc AG, McIntosh JM, Crooks PA, Bardo MT. N,N’-Alkane-diyl-bis-3-picoliniums as nicotinic receptor antagonists: inhibition of nicotine-evoked dopamine release and hyperactivity. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2008;326:563–576. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.136630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exley R, Clements MA, Hartung H, McIntosh JM, Cragg SJ. Alpha6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors dominate the nicotine control of dopamine neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2158–2166. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exley R, Maubourguet N, David V, Eddine R, Evrard A, Pons S, Marti F, Threlfell S, Cazala P, McIntosh JM, Changeux JP, Maskos U, Cragg SJ, Faure P. Distinct contributions of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha4 and subunit alpha6 to the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:7577–7582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exley R, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ, Maskos U, Cragg SJ. Striatal alpha5 nicotinic receptor subunit regulates dopamine transmission in dorsal striatum. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:2352–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4985-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonck C, Cohen BN, Nashmi R, Whiteaker P, Wagenaar DA, Rodrigues-Pinguet N, Deshpande P, McKinney S, Kwoh S, Munoz J, Labarca C, Collins AC, Marks MJ, Lester HA. Novel seizure phenotype and sleep disruptions in knock-in mice with hypersensitive alpha 4* nicotinic receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11396–11411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3597-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Surmeier DJ. Modulation of striatal projection systems by dopamine. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:441–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittis AH, Kreitzer AC. Striatal microcircuitry and movement disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittis AH, Leventhal DK, Fensterheim BA, Pettibone JR, Berke JD, Kreitzer AC. Selective inhibition of striatal fast-spiking interneurons causes dyskinesias. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15727–15731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3875-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Guiducci S, Tedesco V, Corbioli S, Zanetti L, Moretti M, Zanardi A, Rimondini R, Mugnaini M, Clementi F, Chiamulera C, Zoli M. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the mesolimbic pathway: primary role of ventral tegmental area alpha6beta2* receptors in mediating systemic nicotine effects on dopamine release, locomotion, and reinforcement. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5311–5325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5095-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Salminen O, Laverty DC, Whiteaker P, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, Marks MJ. The subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on dopaminergic terminals of mouse striatum. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1235–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Wageman CR, Patzlaff NE, Marks MJ. Low concentrations of nicotine differentially desensitize nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that include alpha5 or alpha6 subunits and that mediate synaptosomal neurotransmitter release. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1935–1943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KJ, McIntosh JM, Brunzell DH, Sanjakdar SS, Damaj MI. The role of alpha6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in nicotine reward and withdrawal. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:547–554. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.155457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester HA, Fonck C, Tapper AR, McKinney S, Damaj MI, Balogh S, Owens J, Wehner JM, Collins AC, Labarca C. Hypersensitive knockin mouse strains identify receptors and pathways for nicotine action. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2003;6:633–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin I, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Recent Advances in the Genetics of Parkinsons Disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2011;12:301–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082410-101440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marubio LM, Gardier AM, Durier S, David D, Klink R, Arroyo-Jimenez MM, McIntosh JM, Rossi F, Champtiaux N, Zoli M, Changeux JP. Effects of nicotine in the dopaminergic system of mice lacking the alpha4 subunit of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1329–1337. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Quarta D, Ciruela F, Patkar K, Borycz J, Solinas M, Lluis C, Franco R, Wise RA, Goldberg SR, Hope BT, Woods AS, Ferre S. Heteromeric Nicotinic Acetylcholine-Dopamine Autoreceptor Complexes Modulate Striatal Dopamine Release. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, McIntosh JM. Striatal alpha6* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: potential targets for Parkinson’s disease therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:481–489. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.094375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Latorre J, Yu CR, Qu X, Perin F, Karlin A, Role L. Functional contributions of alpha5 subunit to neuronal acetylcholine receptor channels. Nature. 1996;380:347–351. doi: 10.1038/380347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME, Patel JC, Cragg SJ. Dopamine release in the basal ganglia. Neuroscience. 2011;198:112–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SA, Wong JY, Clifford JJ, Kinsella A, Massalas JS, Horne MK, Scheffer IE, Kola I, Waddington JL, Berkovic SF, Drago J. Phenotypic characterization of an alpha 4 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit knock-out mouse. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6431–6441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06431.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Drapeau JA, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, Marks MJ, Grady SR. Pharmacology of alpha-conotoxin MII-sensitive subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors isolated by breeding of null mutant mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1563–1571. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.031492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Murphy KL, McIntosh JM, Drago J, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Grady SR. Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1526–1535. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Dani JA. Dopamine enables in vivo synaptic plasticity associated with the addictive drug nicotine. Neuron. 2009;63:673–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia L, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom J. Ca2+ permeability of the (alpha4)3(beta2)2 stoichiometry greatly exceeds that of (alpha4)2(beta2)3 human acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:769–776. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Nashmi R, Schwarz J, Deshpande P, Labarca C, Whiteaker P, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Lester HA. Nicotine activation of alpha4* receptors: sufficient for reward, tolerance, and sensitization. Science. 2004;306:1029–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.1099420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfell S, Lalic T, Platt NJ, Jennings KA, Deisseroth K, Cragg SJ. Striatal dopamine release is triggered by synchronized activity in cholinergic interneurons. Neuron. 2012;75:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooltorton JR, Pidoplichko VI, Broide RS, Dani JA. Differential desensitization and distribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in midbrain dopamine areas. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3176–3185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03176.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Nashmi R, McKinney S, Cai H, McIntosh JM, Lester HA. Chronic nicotine selectively enhances alpha4beta2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nigrostriatal dopamine pathway. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12428–12439. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2939-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Doyon WM, Clark JJ, Phillips PE, Dani JA. Controls of tonic and phasic dopamine transmission in the dorsal and ventral striatum. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:396–404. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.056317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao-Shea R, Cohen BN, Just H, McClure-Begley T, Whiteaker P, Grady SR, Salminen O, Gardner PD, Lester HA, Tapper AR. Dopamine D2-receptor activation elicits akinesia, rigidity, catalepsy, and tremor in mice expressing hypersensitive {alpha}4 nicotinic receptors via a cholinergic-dependent mechanism. FASEB J. 2010;24:49–57. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-137034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Liang Y, Dani JA. Endogenous nicotinic cholinergic activity regulates dopamine release in the striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1224–1229. doi: 10.1038/nn769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]