Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the association between severity of cerebral palsy (CP) and growth to 6 to 7 years of age among children with moderate to severe (Mod/Sev) hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE). It was hypothesized that children with Mod/Sev CP would have poorer growth, lower cognitive scores, and increased rehospitalization rates compared with children with no CP (No CP).

METHODS:

Among 115 of 122 surviving children followed in the hypothermia trial for neonatal HIE, growth parameters and neurodevelopmental status at 18 to 22 months and 6 to 7 years were available. Group comparisons (Mod/Sev CP and No CP) with unadjusted and adjusted analyses for growth <10th percentile and z scores by using Fisher’s exact tests and regression modeling were conducted.

RESULTS:

Children with Mod/Sev CP had high rates of slow growth and cognitive and motor impairment and rehospitalizations at 18 to 22 months and 6 to 7 years. At 6 to 7 years of age, children with Mod/Sev CP had increased rates of growth parameters <10th percentile compared with those with No CP (weight, 57% vs 3%; height, 70% vs 2%; and head circumference, 82% vs 13%; P < .0001). Increasing severity of slow growth was associated with increasing age (P < .04 for weight, P < .001 for length, and P < .0001 for head circumference). Gastrostomy feeds were associated with better growth.

CONCLUSIONS:

Term children with HIE who develop Mod/Sev CP have high and increasing rates of growth <10th percentile by 6 to 7 years of age. These findings support the need for close medical and nutrition management of children with HIE who develop CP.

Keywords: encephalopathy, hypoxia-ischemia, hypothermia, cerebral palsy, growth

What’s Known on This Subject:

Surviving infants with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) treated with hypothermia have decreased rates of CP in childhood. CP is associated with increased risk of slow growth.

What This Study Adds:

Term children with HIE who develop moderate/severe CP are at high risk of progressive impaired growth, high rates of cognitive impairment, and rehospitalizations from infancy to school age. Gastrostomy tube placement to facilitate feeds is protective of slow growth.

Infants who experience moderate or severe hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) are at increased risk of neurodevelopmental disability and moderate to severe (Mod/Sev) cerebral palsy (CP).1–8 Slow growth is more common in children with Mod/Sev CP.9,10 Decreased growth velocity in children with CP may be related to decreased oromotor coordination with suboptimal nutritional intake secondary to impaired chewing and swallowing, recurrent aspiration, chronic reflux, inadequate provision of required nutritional intake, increased caloric expenditure due to the excessive muscle contraction in spasticity for children with ambulatory CP, and the possibility of growth hormone deficiency.10–18 In addition, comorbidities of CP, including gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration, are associated with slow growth and increased risk of rehospitalization.19–23 Vigilance regarding growth of children with feeding difficulties goes beyond the concern of body size alone. Linear growth is correlated with head/brain growth and subsequent neurodevelopmental outcome in infants and young children.24 In addition, inadequate nutritional intake is associated with weakness of respiratory musculature, impaired cough reflex, and pneumonia.25 Growth is an excellent indicator of the overall health of children and there are currently no data available on the growth outcomes of Mod/Sev HIE survivors in the era of hypothermia therapy.3,7 The over-arching goal of this secondary analysis is to use data collected from birth to 6 to 7 years within a cohort of term Mod/Sev HIE survivors with Mod/Sev CP or without CP (No CP) to examine growth, cognitive development, and rehospitalization rates.

The specific aims of this study were (1) to compare the longitudinal weight (WT), head circumference (HC), and length (LT) or height (HT) measurements, percentiles, and z scores for the 2 study groups from birth to 6 to 7 years of age, and (2) to identify factors protective of and associated with slow growth. We hypothesized that children with Mod/Sev CP versus those with No CP would have slower growth trajectories between birth and 6 to 7 years; lower WT, HT, and HC percentiles; and lower z scores at 6 to 7 years. Our second hypothesis was that slower growth would be associated with lower cognitive and motor scores and increased rates of rehospitalization.

Methods

The study was a secondary analysis of prospectively collected data from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network (NRN) Whole Body Cooling trial for neonatal HIE conducted between July 2000 and May 2003.8 Inclusion criteria for the trial included a gestational age of ≥36 weeks, specific physiologic and/or clinical criteria, and the presence of Mod/Sev encephalopathy. The participants in this secondary analysis were the school-aged survivors evaluated at 18 to 22 months and 6 to 7 years with growth data at birth discharge, 18 to 22 months, and 6 to 7 years.7 Detailed demographic information and medical history were obtained at follow-up.

Growth Parameters

WT was obtained by using a horizontal scale at birth, discharge, and 18 to 22 months, and an upright scale at 6 to 7 years. Standard procedures were used.7 Recumbent LT was used at birth, discharge, and 18 to 22 months and upright stature at 6 to 7 years with a permanently affixed stadiometer or upright scale. Horizontal measurement was obtained with a stadiometer for children who were unable to stand. The World Health Organization growth standards26 were used to determine percentiles, velocities, and z scores at birth, discharge, 18 to 22 months, and at 6 to 7 years; the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts27 were used at 6 to 7 years.

Neurodevelopmental Assessments

Comprehensive assessments of neurologic status and development were obtained at 18 to 22 months and 6 to 7 years of age.7 Examiners were trained annually to reliability on all evaluations, and were masked to the intervention. At 18 to 22 months, children were assessed with the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II28 and a Mental Developmental Index (MDI) and Psychomotor Development Index (PDI) were calculated. The Bayley has a mean ± SD score of 100 ± 15. A score <70 is 2 SD below the mean and a score <50 is 3 SD below the mean. Intelligence at 6 to 7 years was assessed with the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence III29 for children up to age 7 years 3 months and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children IV30 for children older than 7 years 3 months or Spanish speaking. These tests derive a full-scale IQ with a mean ± SD of 100 ± 15. A score <70 is 2 SD below the mean and a score <55 is 3 SD below the mean.

CP was defined as a nonprogressive central nervous system disorder with abnormal muscle tone in at least 1 extremity and abnormal control of movement and posture that interfere with age-appropriate activities. Severity of CP was classified by using the gross motor function classification system (GMFCS).31 Mod/Sev CP was defined as GMFCS levels V (n = 16), IV (n = 2), III (n = 4), and II (n = 1). There were no children with mild CP defined as GMFCS level I. The No CP group was defined as any child with no CP. At each visit, parents were queried regarding number of rehospitalizations. Hospitalizations reported for time 1 occurred between discharge and 18 months and for time 2 were cumulative between discharge and 6 to 7 years.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating NICHD NRN sites and parental consent was obtained.

Statistical Analyses

Data were collected at participating NICHD NRN sites and were transmitted to Research Triangle Institute, the data coordinating center (DCC), which analyzed the data. Birth and hospital data were combined with data from the 2 follow-up assessments. Preliminary unadjusted comparisons were made by using t tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.

The specific aims and hypotheses were examined by using the following parallel approaches. For specific aim 1, longitudinal analysis of growth trajectories over time was performed for the 4 assessment time points: birth, discharge, 18 to 22 months, and 6 to 7 years. Separate longitudinal models accounting for repeated measures were developed for each growth parameter, which were treated as continuous variables/outcomes. Factors of principal interest, such as Mod/Sev CP, were entered into these models as time-varying covariates assessed separately at 18 months and 6 to 7 years. Other time-varying factors included in the models were age, public insurance, gastrostomy, and rehospitalization (the latter 3 were assessed only at 18 months and 6 to 7 years). Models also adjusted for interaction between CP and age (to allow for changes in effect of CP over time), treatment group (hypothermia or control), level of encephalopathy at random assignment (moderate or severe), gender, and birth weight (except in the model for WT).

For specific aim 2, multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the independent predictors of suboptimal growth (WT, HT, and HC below the 10th percentile) at 6 to 7 years of age. Factors of principal interest (eg, Mod/Sev CP, treatment group, level of HIE) and other covariates were added to the logistic regression models in a sequential manner, in a series of 3 time-oriented models. The first model consisted of neonatal covariates (gender, birth weight, cooling, and level of HIE), the second model added information at 18 to 22 months (Mod/Sev CP at 18 to 22 months: public health insurance between discharge and 18 to 22 months, rehospitalization from discharge to 18 to 22 months, and gastrostomy feedings at 18 to 22 months), and the third model replaced the 18- to 22-month variables with 6- to 7-year versions of those variables. Center was entered as a random effect in all of the logistic regression models.

Given the sample size and the number of covariates that were deemed necessary to adjust for, we used stepwise backward selection in both the longitudinal and logistic regression models to develop a relatively parsimonious model for each outcome, by using a P value cutoff of .15 to eliminate covariates from the final models that were not significantly related to the outcome in the presence of other covariates.

Results

Derivation of Study Cohort

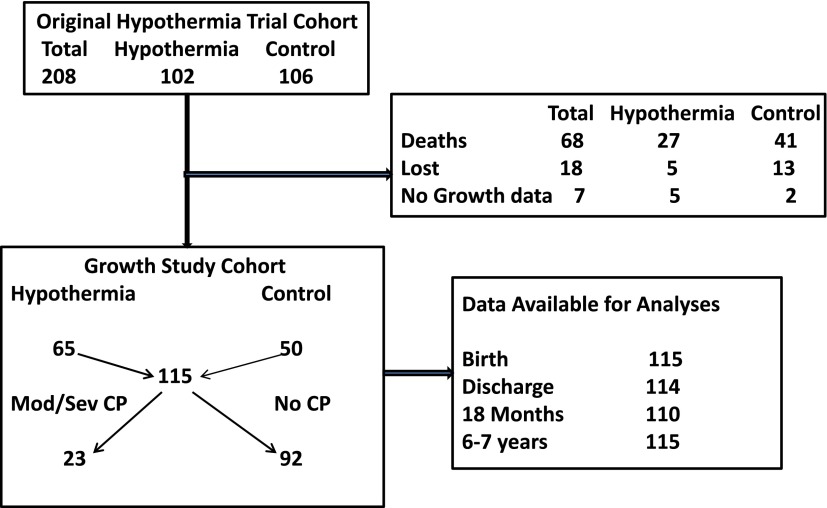

Subjects were the surviving children of the NRN whole-body cooling trial7,8 who were assessed at both 18 to 22 months and 6 to 7 years of age. Growth parameters were available for 65 of 70 children treated with hypothermia and 50 of 52 children in the control group (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study cohort.

The study cohort (n = 115) was compared with the cohort that was lost to follow-up or had no growth parameters (n = 25) on multiple maternal and infant characteristics (data not shown). The only significant group difference identified was percentage with intrapartum fetal heart rate decelerations (growth cohort [73%] versus survivors with no growth data [92%]; P = .04).

Cohort Characteristics

The cohort included 23 children with Mod/Sev CP and 92 children with No CP in the comparison group. Children with Mod/Sev CP were more likely to have had severe encephalopathy (P = .009); more days of ventilation (P = .053); require postdischarge oxygen (P = .007), gavage feeding (P = .002), or gastrostomy feeding (P = .03); and receive anticonvulsant medication (P = .001) (Table 1). At 18 to 22 months among the Mod/Sev children, 3 continued to require oxygen treatment, the number with a gastrostomy had risen to 10 (45%), and only 14% were reported to independently feed themselves compared with 95% with No CP; P < .0001. They were more likely to have had a rehospitalization compared with the No CP children (59% vs 25%; P = .004). Reasons for individual hospitalizations were often multiple. Three (23%) included intractable seizures and 7 (54%) were for either gastrostomy or fundoplication procedure or both. Children with Mod/Sev CP had high rates of severe motor and cognitive impairment with 87% having a Bayley II MDI and Bayley II PDI <50.

TABLE 1.

Neonatal, Postdischarge, 18- to 22-Month, and 6- to 7-Year Characteristics of the Cohort

| Characteristic | Mod/Sev CP Yes | No CP | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 23 | 92 | |

| Prenatal care, n (%) | 21 (91) | 87 (95) | .63 |

| Medicaid, 18 mo, n (%) | 15 (68) | 43 (47) | .10 |

| Medicaid, 7 y, n (%) | 18 (78) | 50 (54) | .06 |

| Maternal education <12 y, birth, n (%) | 4 (24) | 27 (39) | .28 |

| Level of encephalopathy moderate, n (%) | 13 (57) | 77 (84) | .009 |

| Level of encephalopathy severe, n (%) | 10 (43) | 15 (16) | |

| Cooled, n (%) | 9 (39) | 56 (61) | .10 |

| Gestational age, M±SD | 38.4 ± 1.75 | 39.0 ± 1.53 | .08 |

| Small for gestational age, n (%) | 2 (9) | 11 (12) | .99 |

| Days ventilation, M±SD | 7.74 ± 7.99 | 4.23 ± 4.44 | .053 |

| Days hospitalization, M±SD | 20.6 ± 11.6 | 17.0 ± 15.4 | .30 |

| Home therapy prescribed at discharge, n (%) | |||

| Oxygen | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | .007 |

| Gavage tube feeding | 6 (27) | 3 (3) | .002 |

| Gastrostomy feeding | 4 (18) | 3 (3) | .03 |

| Anticonvulsant medication | 16 (73) | 29 (33) | .001 |

| 18–22 mo, n (%) | |||

| Oxygen | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | .007 |

| Gastrostomy feeding | 10 (45) | 1 (1) | <.0001 |

| Independently feeds self | 3 (14) | 86 (95) | <.0001 |

| Rehospitalization by 18–22 mo | 13(59) | 23(25) | .004 |

| Mod/Sev CP | 22 (96) | 0 (0) | <.0001 |

| Bayley PDI <70 | 22 (96) | 6 (7) | <.0001 |

| Bayley PDI <50 | 20 (87) | 3 (3) | <.0001 |

| Bayley MDI <70 | 22 (96) | 7 (8) | <.0001 |

| Bayley MDI <50 | 20 (87) | 0 (0) | <.0001 |

| 6–7 y, n (%) | |||

| Gastrostomy feeding | 12 (52) | 0 (0) | <.0001 |

| Physical therapy | 20 (87) | 6 (7) | <.0001 |

| Occupational therapy | 19 (83) | 8 (9) | <.0001 |

| Rehospitalization by 6–7 y | 18 (78) | 23 (25) | <.0001 |

| Wechsler Full Scale IQ <70 | 22 (96) | 9 (10) | <.0001 |

| Wechsler Full Scale IQ <55 | 20 (87) | 2 (2) | <.0001 |

P values from Fisher’s exact test or t test (GA, days ventilation, days hospitalization).

At 6 to 7 years, the percentage of children in the Mod/Sev group with gastrostomy feeds had risen to 52%. They were more likely to be receiving physical therapy (87% vs 7%; P < .0001) and occupational therapy (83% vs 9%; P < .0001) than the No CP group. The rehospitalization rate continued to be higher for Mod/Sev CP versus No CP (18 [78%] vs 23 [25%]; P < .0001). More than 1 reason was often given for the hospitalization; most frequent for the children with Mod/Sev CP were pneumonia (61%), surgery/tendon releases (56%), reflux/dehydration (44%), seizures (56%), and failure to thrive (22%). The percentage of children with Mod/Sev CP and severe cognitive impairment (IQ <55) was 87%.

Primary Analyses: Growth Characteristics

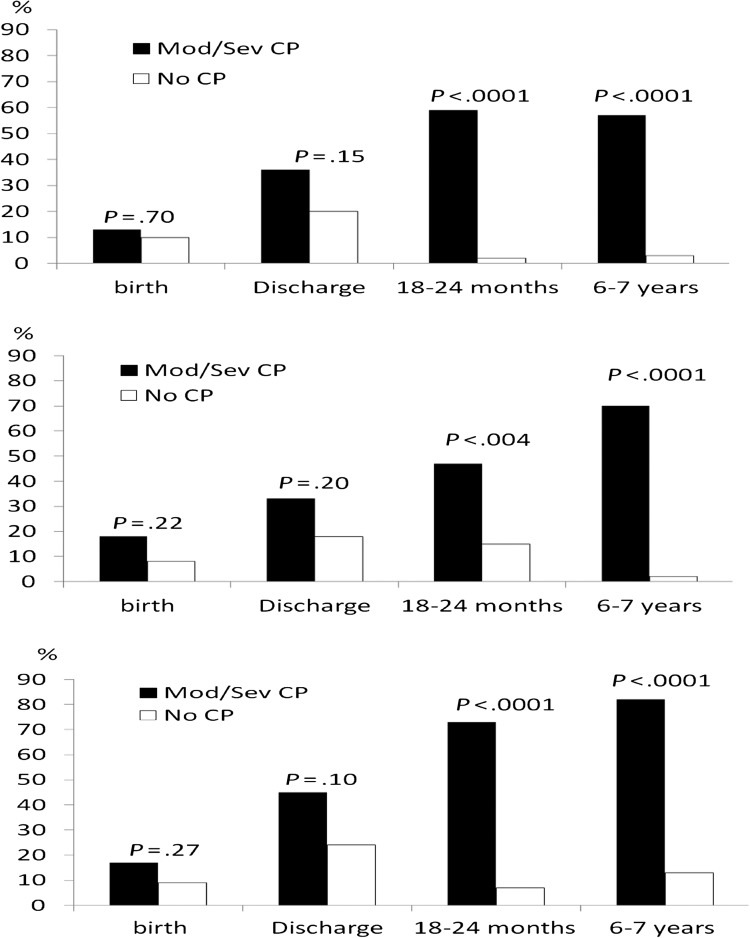

Growth characteristics are shown in Table 2. Children with Mod/Sev CP versus No CP were more likely to have lower WT, LT, and HC z scores and measurements <10th percentile by 18 to 22 months. Rates of HC <10th percentile increased for children with Mod/Sev CP from 45% to 73% to 82% between discharge and 6 and 7 years. The associations of Mod/Sev CP with increasing rates of growth parameters <10th percentile at each evaluation are shown in Fig 2. Additional data not shown in Table 2 were obtained for extreme severity of weight restriction (WT z score <−3) for children with Mod/Sev CP (0%, 9%, 14%, and 24%) versus those with No CP (0%, 2%, 0%, and 0%), respectively, at birth, discharge, 18 to 22 months (P = .007), and 6 to 7 years (P = .0001)

TABLE 2.

Growth Parameters at Birth, Discharge, 18 to 22 Months, and 6 to 7 Years

| Characteristic | Mod/Sev CP Yes | No CP | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 23 | 92 | |

| Birth | |||

| WT, M±SD | 3.29 ± 0.54 | 3.41 ± 0.63 | .38 |

| WT <10th% | 3 (13%) | 9 (10%) | .70 |

| WT z score, M±SD | −0.05 ± 1.14 | 0.17 ± 1.28 | .45 |

| LT, M±SD | 50.5 ± 3.68 | 50.9 ± 2.81 | .54 |

| LT <10th% | 4 (18%) | 7 (8%) | .22 |

| LT z score, M±SD | 0.54 ± 1.89 | 0.71 ± 1.50 | .65 |

| HC, M±SD | 33.9 ± 1.43 | 34.3 ± 1.50 | .36 |

| HC <10th% | 4 (17%) | 8 (9%) | .27 |

| HC z score, M±SD | −0.15 ± 1.17 | 0.04 ± 1.21 | .49 |

| Discharge | |||

| WT, M±SD | 3.48 ± 0.64 | 3.62 ± 0.77 | .42 |

| WT <10th% | 8 (36%) | 18 (20%) | .15 |

| WT z score, M±SD | −0.86 ± 1.31 | −0.40 ± 1.21 | .11 |

| LT, M±SD | 51.5 ± 3.44 | 52.3 ± 3.43 | .39 |

| LT <10th% | 6 (33%) | 15 (18%) | .20 |

| LT z score, M±SD | −0.52 ± 1.82 | −0.001 ± 1.46 | .19 |

| HC, M±SD | 34.9 ± 1.63 | 35.3 ± 1.98 | .43 |

| HC <10th% | 9 (45%) | 21 (24%) | .10 |

| HC z score, M±SD | −1.00 ± 1.63 | −0.42 ± 1.43 | .12 |

| 18–22 mo | |||

| WT, M±SD | 9.54 ± 1.97 | 11.8 ± 1.62 | <.0001 |

| WT <10th% | 13 (59%) | 2 (2%) | <.0001 |

| WT z score, M±SD | −1.48 ± 1.36 | 0.47 ± 0.95 | <.0001 |

| LT, M±SD | 80.2 ± 5.84 | 82.7 ± 3.77 | .10 |

| LT <10th% | 9 (47%) | 13 (15%) | .004 |

| LT z score, M±SD | −1.53 ± 1.42 | −0.30 ± 1.08 | <.0001 |

| HC, M±SD | 44.3 ± 2.21 | 47.7 ± 1.63 | <.0001 |

| HC <10th% | 16 (73%) | 6 (7%) | <.0001 |

| HC z score, M±SD | −2.04 ± 1.87 | 0.37 ± 1.09 | <.0001 |

| 6–7 y | |||

| WT, M±SD | 20.5 ± 6.48 | 25.5 ± 5.50 | .0004 |

| WT <10th% | 12 (57%) | 3 (3%) | <.0001 |

| WT z score, M±SD | −1.25 ± 1.84 | 0.54 ± 1.05 | .0003 |

| LT, M±SD | 113.4 ± 8.73 | 121.6 ± 6.05 | .0005 |

| LT <10th% | 14 (70%) | 2 (2%) | <.0001 |

| LT z score, M±SD | −1.52 ± 1.68 | 0.23 ± 1.01 | .0002 |

| HC, M±SD | 47.8 ± 2.77 | 51.9 ± 1.72 | <.0001 |

| HC <10th% | 18 (82%) | 12 (13%) | <.0001 |

P values are from t test or Fisher’s exact test (<10th percentile). Data for measurements and z scores are presented as mean ± SD, and parameter <10th percentile.

FIGURE 2.

Association of Mod/Sev CP at 6 to 7 years with WT, LT/HT, and HC <10th percentile.

Secondary Analyses

Time-oriented logistic regression models to predict WT, HT, and HC <10th percentile at 6 to 7 years are shown in Table 3. Models were adjusted for treatment group (hypothermia versus none), gender, birth weight, level of HIE, type of health insurance, rehospitalization, gastrostomy, and Mod/Sev CP. In the model with only neonatal risk factors, greater severity of level of HIE contributed to higher rate of WT, LT, and HC <10th percentile at 6 to 7 years. In the models incorporating information obtained at 18 to 22 months and 6 to 7 years, Mod/Sev CP was the strongest predictor of WT, HT, and HC below the 10th percentile. In the 18- to 22-month model, rehospitalization was associated with almost 10 times greater risk of HC <10th percentile (odds ratio [OR] = 9.46; confidence interval [CI] = 2.02–44.30; P = .009). In the model incorporating 6- to 7-year follow-up information, rehospitalization at 6 to 7 years was significantly associated with an HC <10th percentile (OR = 4.99; CI = 1.23–20.20; P = .03). Backward covariate selection removed level of HIE from most models, and even when retained it was not statistically significant (P ≥ .1).

TABLE 3.

Logistic Regressions to Predict Growth <10th Percentile at 6 to 7 Years of Age

| Predictors | WT <10th% | LT <10th% | HC <10th% | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Neonatal model | |||||||||

| Severe level of HIE | 3.98 | 1.07–14.8 | .04 | 7.42 | 1.83–30.1 | .01 | 3.94 | 1.31–11.8 | .02 |

| 18-mo model | |||||||||

| Mod/Sev CP at 18 mo | 120 | 12.6– >999 | .001 | 50.9 | 7.03–369 | .002 | 51.8 | 6.99–383 | .002 |

| Rehospitalization at 18 mo | Removed † | .84 | Removed † | .82 | 9.46 | 2.02–44.3 | .009 | ||

| 6–7 y model | |||||||||

| Mod/Sev CP at 6–7 y | 129 | 12.9– >999 | .001 | 525 | 13.5– >999 | .004 | 27.6 | 4.60–165 | .002 |

| Rehospitalization at 6–7 y | Removed † | .27 | Removed † | .62 | 4.99 | 1.23–2.2 | .03 | ||

Backward selection was used to remove non-significant variables from the model (P <.15 to remain in the model). This was not applied to treatment group.

Table 4 shows the longitudinal modeling conducted for growth z scores to examine increasing age effects on severity of growth restriction. In all of the models, Mod/Sev CP had a significant negative effect in predicting WT, LT/HT, and HC z score at 6 to 7 years (all P < .0001), with the adjusted mean difference in the z score between infants with Mod/Sev CP and No CP >−1.0. Higher birth weight was significantly associated with more optimal LT/HT and HC z scores, which increased by 0.96 and 0.90, respectively, for each kilogram increase in birth weight (both P < .0001); use of a gastrostomy was associated with better growth of WT and LT but not head growth.

TABLE 4.

Longitudinal Models to Predict Growth z Scores Over Time

| Predictors | β Estimatea | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT z score over time, birth to 6–7 y | |||

| Age, per 100 d | 0.01 | 0.003 to 0.03 | .02 |

| Mod/Sev CPb | −1.40 | −1.98 to −0.83 | <.0001 |

| Gastrostomyb | 0.87 | 0.12 to 1.63 | .02 |

| LT/HT z score over time, birth to 6–7 y | |||

| Birth weight | 0.96 | 0.74 to 1.17 | <.0001 |

| Time-varying covariates | |||

| Age, per 100 d | −0.01 | −0.03 to −0.0008 | .04 |

| Mod/Sev CPb | −1.08 | −1.51 to −0.64 | <.0001 |

| Rehospitalizationb | −0.30 | −0.62 to 0.01 | .06 |

| Gastrostomyb | 0.96 | 0.46 to 1.46 | .0002 |

| HC z score over time, birth to 18−22 mo | |||

| Birth weight | 0.90 | 0.64 to 1.17 | <.0001 |

| Time-varying covariates | |||

| Mod/Sev CPb | −1.03 | −1.45 to −0.60 | <.0001 |

For binary covariates, βs represent the adjusted mean difference between the 2 levels of the covariate; for continuous covariates (eg, birth weight), they represent the adjusted mean difference in the growth z score per unit change in the associated covariate.

For measurements at birth and discharge, data at 18 months are used for these time-varying variables.

Statistical interactions were tested between Mod/Sev CP and age on z scores for WT, HT, and HC, as shown in Table 5. These models allow for the effect of Mod/Sev CP to change over time, and, conversely, for the effect of age to be different for the 2 study groups, which is a pattern suggested by Fig 2. The interaction between age and CP was significant for WT (P = .001), LT (P = .002), and HC (P = .0001). Children with Mod/Sev CP had z scores that deviated farther from the mean of the reference population with increasing age, indicating greater severity of growth restriction over time. In contrast, children with No CP had evidence of catch-up growth.

TABLE 5.

Longitudinal Regression Models with Ageb CP Interactions

| Predictors | β Estimatea | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal model to predict WT z score over time, birth to 6–7 y | |||

| Neonatal variables | |||

| Treatment group: hypothermia | 0.15 | −0.16 to 0.46 | .33 |

| Time-varying covariates | |||

| Age, per 100 d | 0.02 | 0.01 to 0.04 | <.0001 |

| Mod/Sev CPb | −0.98 | −1.65 to −0.32 | .004 |

| Gastrostomyb | 0.94 | 0.23 to 1.66 | .01 |

| Ageb CP interaction | −0.05 | −0.09 to −0.02 | .001 |

| Effect of age: No CP | 0.02 | 0.01 to 0.04 | <.0001 |

| Effect of age: Mod/Sev CP | −0.03 | −0.06 to 0.001 | .059 |

| Effect of Mod/Sev CP: 20 mo | −1.31 | −1.90 to −0.72 | <.0001 |

| Effect of Mod/Sev CP: 6.5 y | −2.26 | −2.98 to −1.54 | <.0001 |

| Longitudinal model to predict LT/HT z score over time, birth to 6–7 y | |||

| Neonatal variables | |||

| Treatment group: hypothermia | −0.04 | −0.32 to 0.24 | .79 |

| Birth weight | 0.95 | 0.73 to 1.17 | <.0001 |

| Time-varying covariates | |||

| Age, per 100 d | −0.003 | −0.02 to 0.009 | .62 |

| Mod/Sev CPb | −0.60 | −1.22 to 0.03 | .06 |

| Public insuranceb | −0.18 | −0.43 to 0.08 | .17 |

| Rehospitalizationb | −0.26 | −0.58 to 0.06 | .11 |

| Gastrostomyb | 0.95 | 0.39 to 1.51 | .0009 |

| Ageb CP interaction | −0.06 | −0.09 to −0.02 | .002 |

| Effect of age: No CP | −0.003 | −0.02 to 0.009 | .62 |

| Effect of age: CP | −0.06 | −0.10 to −0.03 | .0005 |

| Effect of Mod/Sev CP: 20 mo | −0.95 | −1.45 to −0.45 | .0002 |

| Effect of Mod/Sev CP: 6.5 y | −1.97 | −2.59 to −1.35 | <00001 |

| Longitudinal model to predict HC z score over time (birth to 18–22 mo) | |||

| Neonatal variables | |||

| Treatment group: hypothermia | −0.04 | −0.39 to 0.32 | .83 |

| Birth weight | 0.90 | 0.63 to 1.16 | <.0001 |

| Time-varying covariates | |||

| Age, per 100 d | 0.09 | 0.05 to 0.13 | <.0001 |

| Mod/Sev CPb | −0.21 | −0.70 to 0.27 | .39 |

| Rehospitalizationb | −0.33 | −0.69 to 0.03 | .08 |

| Ageb CP interaction | −0.35 | −0.45 to −0.25 | <.0001 |

| Effect of age: No CP | 0.09 | 0.05 to 0.13 | <.0001 |

| Effect of age: Mod/Sev CP | −0.26 | −0.35 to −0.17 | <.0001 |

| Effect of Mod/Sev CP: 20 mo | −2.33 | −2.90 to −1.77 | <.0001 |

| Effect of Mod/Sev CP: 6.5 y | −8.46 | −10.63 to −6.29 | <.0001 |

For binary covariates, βs represent the adjusted mean difference between the 2 levels of the covariate; for continuous covariates (eg, birth weight), they represent the adjusted mean difference in the growth z score per unit change in the associated covariate.

For measurements at birth and discharge, data at 18 months are used for these time-varying variables.

The significant interaction between Mod/Sev CP and age prompted us to conduct a subgroup analysis among only the children with Mod/Sev CP. When the longitudinal regression model was run for the subset with Mod/Sev CP (Table 6), gastrostomy was beneficial for WT z score (adjusted mean difference in z score = 1.02; P = .006), and the hypothermia treatment group was beneficial for LT/HT z score (adjusted mean difference in z score = 0.63; P = .01).

TABLE 6.

Longitudinal Regression Models to Predict 6- to 7-Year Growth z Scores Only Among Infants With Mod/Sev CP

| Variable | WT | LT/HT | HC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P Value | β | P Value | β | P Value | |

| Age, per 100 d | −0.03 | .04 | −0. 06 | .001 | −0.26 | <.0001 |

| Gastrostomy | 1.02 | .006 | Removed from modela | Removed from modela | ||

| Treatment group | −0.03 | .92 | 0.63 | .01 | 0.11 | .81 |

| Rehospitalization | Removed from modela | Removed from modela | −0.76 | .04 | ||

| Birth weight | N/A | 2.33 | <.0001 | 1.72 | <.0001 | |

| Gender | Removed from modela | Removed from modela | −0.82 | .07 | ||

Insurance and level of HIE were also removed from all 3 models.

Discussion

This study cohort represents a select homogeneous group of children who were diagnosed with Mod/Sev HIE by using strict criteria with follow-up conducted by examiners trained to reliability in all components of the assessment. Our findings supported our hypothesis that term children with Mod/Sev HIE who develop Mod/Sev CP have significantly slower growth and increasing severity of suboptimal growth between birth and 6 to 7 years compared with children with No CP. This is consistent with other reports showing trajectories of increasing rate and severity of growth failure for children with Mod/Sev CP.9,10,13,16,17 Infant and child characteristics provide insight into factors associated with slow growth. During the neonatal hospitalization, infants in the ModSev CP group had greater illness severity reflected by level of HIE and longer duration of ventilatory support. At discharge, they had high rates of medical needs, including continued oxygen requirement, gavage or gastrostomy feeds, and anticonvulsant medications.

Rehospitalization rate was high for the Mod/Sev group at both 18 months (59%) and 6 to 7 years (78%) and was independently associated with HC <10th percentile in both 18- to 22-month and 6- to 7-year regression models. Our findings suggest that increased rates of comorbidities contributed to rehospitalization. At 18 months, 23% of hospitalizations were for intractable seizures, and 54% were for surgery to address persistent feeding/nutrition abnormalities. Hospitalizations at 6 to 7 years (pneumonia [56%], reflux/dehydration [44%], and failure to thrive [22%]) may all be related to feeding issues and possible aspiration. The high rate of surgical procedures, including tendon releases, suggests high rates of spasticity. The relationship between feeding difficulties, aspiration, and poor growth with severe motor impairments has been previously reported.32,33

Feeding and respiratory difficulties resulting in rehospitalization were reported at both follow-up visits. After discharge, an additional 8 children had gastrostomy and 5 had fundoplication surgery. Families may be reluctant to accept the surgical intervention until growth restriction is severe or until aspiration becomes a concern. Our findings confirm the importance of gastrostomy feeds to support nutritional intake and growth for children with Mod/Sev CP. This is consistent with the study of gastrostomy placement among children with CP by Sullivan et al34 in which they showed clinically significant increases in WT 12 months after gastrostomy placement.

Because in the main trial hypothermia treatment was associated with a decreased rate of Mod/Sev disability among surviving infants, we included hypothermia in our regression models. In the model restricted to only the children with Mod/Sev CP, hypothermia was associated with a 0.63 increase in z score for HT at ages 6 to 7. Because this was identified in a single regression model, the significance of the finding remains unclear.

Neurocognitive outcomes of the children with Mod/Sev CP were poor, with high rates of severe cognitive (87%) and motor impairment (87%) at both 18 months and at 6 to 7 years, and high rates of hospitalizations for seizure management and surgical procedures related to CP. These severe neurologic and cognitive impairments suggest this population of term Mod/Sev HIE survivors with Mod/Sev CP is a vulnerable population. The areas of brain injury noted in the infants with Mod/Sev encephalopathy have recently been described in the Total Body Hypothermia, NICHD, and Infant Cooling Evaluation trials, respectively.35–37 Areas of injury include the basal ganglia, thalamus, anterior and posterior internal capsule, white matter cortical areas, and watershed areas of infarction.

Strengths of our study include longitudinal data from newborn to 6 to 7 years on term HIE infants who participated in a randomized trial. Limitations include lack of nutritional intake data, missing growth data on 7 children, secondary analysis not powered to evaluate growth outcomes, and use of a standard protocol for assessing linear growth. Segmental measurements of extremities have been found to be more reliable in obtaining accurate linear measurements for children with severe CP and contractures.38,39 Finally, the infants who were randomly assigned to the control group had a higher mortality rate,7 hence information on the surviving infants may be subject to bias.

Our study provides evidence of early and progressive growth failure among term infants with Mod/Sev HIE who develop Mod/Sev CP. Placement of a gastrostomy was beneficial for growth, suggesting that earlier intervention for feeding difficulties in this population may provide added benefit.19–23 The combination of Mod/Sev CP, poor growth, associated comorbidities, and increased use of health care presents a significant public health problem. In 2006, children with neurologic impairment in the United States accounted for 29% (US$12.0 billion) of hospital charges within children’s hospitals.40 Our findings support the need for close medical and nutritional management of children with HIE who are diagnosed with CP.

Acknowledgments

Data collected at participating sites of the NICHD NRN were transmitted to RTI International, the DCC for the network, which stored, managed, and analyzed the data for this study. On behalf of the NRN, Dr Das (DCC Principal Investigator) and Mr McDonald (DCC Statistician) had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. The following investigators, in addition to those listed as authors, participated in this study:

NRN Extended Hypothermia Follow-up Subcommittee: Seetha Shankaran, chair, Richard A. Ehrenkranz, Susan R. Hintz, Athina Pappas, Jon E. Tyson, Betty R. Vohr, Kimberly Yolton, Abhik Das, Rosemary D. Higgins, Rebecca Bara.

NRN Steering Committee Chairs: Alan H. Jobe, MD, PhD, University of Cincinnati (2003–2006); Michael S. Caplan, MD, University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine (2006–present).

Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (U10 HD27904): Theresa M. Leach, MEd, CAES; William Oh, MD; Angelita M. Hensman, RN, BSN; Lucy Noel; Victoria E. Watson, MS, CAS.

Case Western Reserve University, Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital (U10 HD21364, M01 RR80): Michele C. Walsh, MD, MS; Avroy A. Fanaroff, MD; Deanne E. Wilson-Costello, MD; Nancy Bass, MD; Harriet G. Friedman, MA; Nancy S. Newman, BA, RN; Bonnie S. Siner, RN.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and University of Cincinnati Hospital (U10 HD27853, M01 RR8084): Kurt Schibler, MD; Edward F. Donovan, MD; Kimberly Yolton, PhD; Kate Bridges, MD; Jean J. Steichen, MD; Barbara Alexander, RN; Cathy Grisby, BSN, CCRC; Holly L. Mincey, RN, BSN; Jody Hessling, RN; Teresa L. Gratton, PA.

Duke University School of Medicine, University Hospital, Alamance Regional Medical Center, and Durham Regional Hospital (U10 HD40492, M01 RR30): Ronald N. Goldberg, MD; C. Michael Cotten, MD, MHS; Ricki F. Goldstein, MD; Kathryn E. Gustafson, PhD; Kathy J. Auten, MSHS; Katherine A. Foy, RN; Kimberley A. Fisher, PhD, FNP-BC, IBCLC; Sandy Grimes, RN, BSN; Melody B. Lohmeyer, RN, MSN.

Emory University, Grady Memorial Hospital, and Emory University Hospital Midtown (U10 HD27851, M01 RR39): Barbara J. Stoll, MD; David P. Carlton, MD; Lucky Jain, MD; Ira Adams-Chapman, MD; Ann M. Blackwelder, RNC, BS, MS; Ellen C. Hale, RN, BS, CCRC; Sobha Fritz, PhD.

NICHD: Linda L. Wright, MD; Elizabeth M. McClure, MEd; Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.

Indiana University, University Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Riley Hospital for Children, and Wishard Health Services (U10 HD27856, M01 RR750): Brenda B. Poindexter, MD, MS; James A. Lemons, MD; Anna M. Dusick, MD, FAAP; Diana D. Appel, RN, BSN; Jessica Bissey, PsyD, HSPP; Dianne E. Herron, RN; Lucy C. Miller, RN, BSN, CCRC; Leslie Richard, RN; Leslie Dawn Wilson, BSN, CCRC.

RTI International (U10 HD36790): W. Kenneth Poole, PhD; Jeanette O’Donnell Auman, BS; Margaret Cunningham, BS; Jane Hammond, PhD; Betty K. Hastings; Jamie E. Newman, PhD, MPH; Carolyn M. Petrie Huitema, MS; Scott E. Schaefer, MS; Kristin M. Zaterka-Baxter, RN, BSN.

Stanford University and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (U10 HD27880, M01 RR70): Krisa P. Van Meurs, MD; Susan R. Hintz, MD, MS Epi; David K. Stevenson, MD; M. Bethany Ball, BS, CCRC; Maria Elena DeAnda, PhD.

University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System and Children’s Hospital of Alabama (U10 HD34216, M01 RR32): Waldemar A. Carlo, MD; Namasivayam Ambalavanan, MD; Myriam Peralta-Carcelen, MD, MPH; Kathleen G. Nelson, MD; Monica V. Collins, RN, BSN, MAEd; Shirley S. Cosby, RN, BSN; Vivien A. Phillips, RN, BSN; Laurie Lou Smith, EdS, NCSP.

University of California-San Diego Medical Center and Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women (U10 HD40461): Neil N. Finer, MD; David Kaegi, MD; Maynard R. Rasmussen, MD; Yvonne E. Vaucher, MD, MPH; Martha G. Fuller, RN, MSN; Kathy Arnell, RNC; Chris Henderson, RCP, CRTT; Wade Rich, BSHS, RRT.

University of Miami Holtz Children’s Hospital (U10 HD21397, M01 RR16587): Shahnaz Duara, MD; Charles R. Bauer, MD; Sylvia Hiriart-Fajardo, MD; Mary Allison, RN; Maria Calejo, MS; Ruth Everett-Thomas, RN, MSN; Silvia M. Frade Eguaras, MA; Susan Gauthier, BA.

University of Rochester Medical Center, Golisano Children’s Hospital (U10 HD40521, M01 RR44): Dale L. Phelps, MD; Gary J. Myers, MD; Ronnie Guillet, MD, PhD; Diane Hust, MS, RN, CS; Linda J. Reubens, RN, CCRC.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Parkland Health & Hospital System, and Children’s Medical Center Dallas (U10 HD40689, M01 RR633): Pablo J. Sánchez, MD; R. Sue Broyles, MD; Abbot R. Laptook, MD; Charles R. Rosenfeld, MD; Walid A. Salhab, MD; Roy J. Heyne, MD; Cathy Boatman, MS, CIMI; Cristin Dooley, PhD, LSSP; Gaynelle Hensley, RN; Jackie F. Hickman, RN; Melissa H. Leps, RN; Susie Madison, RN; Nancy A. Miller, RN; Janet S. Morgan, RN; Lizette E. Torres, RN; Alicia Guzman.

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Medical School, Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, and Lyndon Baines Johnson General Hospital/Harris County Hospital District (U10 HD21373, M01 RR2588): Jon E. Tyson, MD, MPH; Kathleen A. Kennedy, MD, MPH; Esther G. Akpa, RN, BSN; Claudia I. Franco, RN, BSN; Anna E. Lis, RN, BSN; Georgia E. McDavid, RN; Patti L. Pierce Tate, RCP; Nora I. Alaniz, BS; Magda Cedillo; Susan Dieterich, PhD; Patricia W. Evans, MD; Charles Green, PhD; Margarita Jiminez, MD; Terri Major-Kincade, MD, MPH; Brenda H. Morris, MD; M. Layne Poundstone, RN, BSN; Stacey Reddoch, BA; Saba Siddiki, MD; Maegan C. Simmons, RN; Laura L. Whitely, MD; Sharon L. Wright, MT.

Wayne State University, Hutzel Women’s Hospital, and Children’s Hospital of Michigan (U10 HD21385): Athina Pappas, MD; Yvette R. Johnson, MD, MPH; Rebecca Bara, RN, BSN; Laura A. Goldston, MA; Geraldine Muran, RN, BSN; Deborah Kennedy, RN, BSN; Patrick J. Pruitt, BS.

Yale University, Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital (U10 HD27871, M01 RR125, UL1 RR24139): Patricia Gettner, RN; Monica Konstantino, RN, BSN; JoAnn Poulsen, RN; Elaine Romano, MSN; Joanne Williams, RN, BSN; Susan DeLancy, MA, CAS.

Department of Pediatrics, Women & Infants Hospital, Brown University, Providence, RI

Statistics and Epidemiology Unit, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC

Department of Pediatrics, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Department of Pediatrics, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD

Statistics and Epidemiology Unit, RTI International, Rockville, MD

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- CP

cerebral palsy

- DCC

data coordinating center

- GMFCS

gross motor function classification system

- HC

head circumference

- HIE

hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

- HT

height

- LT

length

- MDI

Mental Developmental Index

- Mod/Sev

moderate to severe

- NICHD

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- NRN

Neonatal Research Network

- OR

odds ratio

- PDI

Psychomotor Development Index

- WT

weight

Footnotes

Dr Vohr conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the original manuscript, and approved the final manuscript before it was submitted; Drs Stephens, Ehrenkranz, Shankaran, Higgins, Pappas and Hintz reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted; and Mr McDonald and Dr Das carried out the data analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00005772).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: The National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network’s Whole-Body Hypothermia Trial and its 6–7 Year School-age Follow-up (recruitment July 2000 through May 2003; follow-up July 2006 through May 2010). Funded by the National Institutes of Health.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.de Vries LS, Jongmans MJ. Long-term outcome after neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010;95(3):F220–F224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez FF, Miller SP. Does perinatal asphyxia impair cognitive function without cerebral palsy? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91(6):F454–F459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guillet R, Edwards AD, Thoresen M, et al. CoolCap Trial Group . Seven- to eight-year follow-up of the CoolCap trial of head cooling for neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatr Res. 2012;71(2):205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marlow N, Rose AS, Rands CE, Draper ES. Neuropsychological and educational problems at school age associated with neonatal encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90(5):F380–F387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson CMT. Long-term follow-up of term infants with perinatal asphyxia. In: Stevenson DK, Sunshine P, Benitz, WE eds. Fetal and Neonatal Brain Injury. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankaran S, Woldt E, Koepke T, Bedard MP, Nandyal R. Acute neonatal morbidity and long-term central nervous system sequelae of perinatal asphyxia in term infants. Early Hum Dev. 1991;25(2):135–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankaran S, Pappas A, McDonald SA, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network . Childhood outcomes after hypothermia for neonatal encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2085–2092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1574–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell KL, Boyd RN, Tweedy SM, Weir KA, Stevenson RD, Davies PS. A prospective, longitudinal study of growth, nutrition and sedentary behaviour in young children with cerebral palsy. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson RD, Conaway M, Chumlea WC, et al. North American Growth in Cerebral Palsy Study . Growth and health in children with moderate-to-severe cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):1010–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fung EB, Samson-Fang L, Stallings VA, et al. Feeding dysfunction is associated with poor growth and health status in children with cerebral palsy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(3):361–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemingway C, McGrogan J, Freeman JM. Energy requirements of spasticity. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43(4):277–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krick J, Murphy-Miller P, Zeger S, Wright E. Pattern of growth in children with cerebral palsy. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96(7):680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reilly S, Skuse D. Characteristics and management of feeding problems of young children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992;34(5):379–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shim ML, Moshang T, Jr, Oppenheim WL, Cohen P. Is treatment with growth hormone effective in children with cerebral palsy? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(8):569–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevenson RD, Hayes RP, Cater LV, Blackman JA. Clinical correlates of linear growth in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1994;36(2):135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevenson RD, Roberts CD, Vogtle L. The effects of non-nutritional factors on growth in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1995;37(2):124–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stallings VA, Zemel BS, Davies JC, Cronk CE, Charney EB. Energy expenditure of children and adolescents with severe disabilities: a cerebral palsy model. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(4):627–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reyes AL, Cash AJ, Green SH, Booth IW. Gastrooesophageal reflux in children with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 1993;19(2):109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustafsson PM, Tibbling L. Gastro-oesophageal reflux and oesophageal dysfunction in children and adolescents with brain damage. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83(10):1081–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis D, Khoshoo V, Pencharz PB, Golladay ES. Impact of nutritional rehabilitation on gastroesophageal reflux in neurologically impaired children. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29(2):167–169, discussion 169–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samson-Fang L, Fung E, Stallings VA, et al. Relationship of nutritional status to health and societal participation in children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr. 2002;141(5):637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liptak GS, O’Donnell M, Conaway M, et al. Health status of children with moderate to severe cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43(6):364–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramel SE, Demerath EW, Gray HL, Younge N, Boys C, Georgieff MK. The relationship of poor linear growth velocity with neonatal illness and two-year neurodevelopment in preterm infants. Neonatology. 2012;102(1):19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly SM, Rosa A, Field S, Coughlin M, Shizgal HM, Macklem PT. Inspiratory muscle strength and body composition in patients receiving total parenteral nutrition therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;130(1):33–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Onis M, Garza C, Onyango AW, Rolland-Cachera MF, le Comité de nutrition de la Société française de pédiatrie . WHO growth standards for infants and young children [in French]. Arch Pediatr. 2009;16(1):47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):45–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wechsler D. Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-III. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wechsler D. The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 4th ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palisano RJ, Cameron D, Rosenbaum PL, Walter SD, Russell D. Stability of the gross motor function classification system. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(6):424–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrew MJ, Parr JR, Sullivan PB. Feeding difficulties in children with cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2012;97(6):222–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirrett PL, Riski JE, Glascott J, Johnson V. Videofluoroscopic assessment of dysphagia in children with severe spastic cerebral palsy. Dysphagia. 1994;9(3):174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan PB, Juszczak E, Bachlet AM, et al. Gastrostomy tube feeding in children with cerebral palsy: a prospective, longitudinal study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47(2):77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shankaran S, Barnes PD, Hintz SR, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Brain injury following trial of hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97(6):F398–F404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheong JL, Coleman L, Hunt RW, et al. Infant Cooling Evaluation Collaboration . Prognostic utility of magnetic resonance imaging in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: substudy of a randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(7):634–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutherford M, Ramenghi LA, Edwards AD, et al. Assessment of brain tissue injury after moderate hypothermia in neonates with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy: a nested substudy of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(1):39–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevenson RD. Measurement of growth in children with developmental disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1996;38(9):855–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chumlea WC, Guo SS, Steinbaugh ML. Prediction of stature from knee height for black and white adults and children with application to mobility-impaired or handicapped persons. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:1385–1388, 1391; quiz 1389–1390 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Berry JG, Poduri A, Bonkowsky JL, et al. Trends in resource utilization by children with neurological impairment in the United States inpatient health care system: a repeat cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2012;9(1):e1001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]