Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Over the past decades, increased knowledge about childhood abuse and trauma have prompted changes in child welfare policy, and practice that may have affected the out-of-home (OOH) care population. However, little is known about recent national trends in child maltreatment, OOH placement, or characteristics of children in OOH care. The objective of this study was to examine trends in child maltreatment and characteristics of children in OOH care.

METHODS:

We analyzed 2 federal administrative databases to identify and characterize US children who were maltreated (National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System) or in OOH care (Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System). We assessed trends between 2000 and 2010.

RESULTS:

The number of suspected maltreatment cases increased 17% from 2000 to 2010, yet the number of substantiated cases decreased 7% and the number of children in OOH care decreased 25%. Despite the decrease in OOH placements, we found a 19% increase in the number of children who entered OOH care because of maltreatment (vs other causes), a 36% increase in the number of children with multiple (vs single) types of maltreatment, and a 60% increase in the number of children in OOH care identified as emotionally disturbed.

CONCLUSIONS:

From 2000 to 2010, fewer suspected cases of maltreatment were substantiated, despite increased investigations, and fewer maltreated children were placed in OOH care. These changes may have led to a smaller but more complex OOH care population with substantial previous trauma and emotional problems.

Keywords: foster care, mental health, maltreatment, child welfare, children

What’s Known on This Subject:

Over the past decade, child welfare has focused on permanency for children through policy changes intended to reduce OOH placements. Yet little is known about recent trends in child maltreatment or children in OOH care.

What This Study Adds:

Despite increased maltreatment investigations from 2000 through 2010, the population of children in OOH placements declined, while experiencing greater prior trauma and current emotional disturbance. These changes may have resulted in a smaller but more complex OOH population.

The last decade of the twentieth century saw an unprecedented increase in the daily census of children in out-of-home (OOH) placements, from ∼400 000 at the end of the fiscal year 1990 to ∼568 000 in 1999.1 These numbers have since decreased. Societal factors, such as the crack/cocaine epidemic and reduced benefits to needy families through welfare reform, led to the initial rise,2 and a number of forces, including legislation affecting child welfare, contributed to the subsequent decline.

Simultaneously, child development research enhanced our understanding of the short- and long-term impacts of child maltreatment,3–5 and studies confirmed the powerful positive influence of caregiver attachment and childhood security on physiologic and psychological development.6–8 This expansion in knowledge, together with the fiscal pressures posed by the growing OOH care population, resulted in an increased focus on the health, safety, and well-being of the OOH care population. Federal Legislation enacted in 1997 (ASFA, P.L. 105-89) required states to reduce children’s time in OOH care by expediting reunification with birth parents or facilitating adoption when reunification was not safe or possible. Child welfare also increased formal placements with kinship caregivers in lieu of more traditional nonrelative foster care and began to restructure the investigative process with the goal of enhancing family supports by providing services that may prevent placement.9 Thus, both expanding knowledge and financial pressures may have contributed to major changes in the OOH care population.

Despite the advances in knowledge and important new policies and systems changes, there has been limited analysis of national trends in child maltreatment, OOH placements, and characteristics of the OOH care population since 2000. We hypothesized that the policies intended to reduce the OOH population may have prevented OOH placements, particularly among lower-risk families, resulting in a smaller population of children in OOH care yet one with more complex needs.10 We reviewed existing national child welfare data for an 11-year period (2000–2010) to evaluate (1) the prevalence and trends in maltreatment and OOH care, (2) demographic and socioenvironmental characteristics of children in OOH care and changes in these factors since 2000, and (3) the severity of needs of the OOH care population by studying the number of types of maltreatment before placement and the proportion of children in OOH care with emotional disturbance.

Methods

The University of Rochester Institutional Review Board approved this study for exempt status.

Study Design

We analyzed 2 national-level data sets to derive the number and status of suspected child maltreatment cases and the number and characteristics of OOH care placements.

Data Sources

The National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) data set contains state-specific information, grouped annually by fiscal year, on all reports of child maltreatment in each state and 2 territories, Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico. To evaluate trends in child maltreatment, we analyzed annual releases of NCANDS data from the Administration on Children, Youth and Families for 2000 and 2010.11 We used these data to evaluate trends and case outcomes. Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) contains semiannual data, compiled and grouped by fiscal year, that all states and territories are federally mandated to submit on every child in OOH care.12 We examined AFCARS data for children who were in OOH care on or before September 30 for fiscal years 2000 through 2010 and evaluated trends, severity of maltreatment, and emotional problems among children in OOH care.

Measures

We analyzed child maltreatment reports from NCANDS data to derive rates of maltreatment for children from birth to 18 years of age. For years 2000 through 2010, we examined rates of suspected maltreatment (referred and deemed eligible for investigation). For suspected maltreatment that was investigated, we examined 3 available outcomes: (1) substantiated maltreatment, (2) indicated maltreatment (inadequate evidence to support suspicions), and (3) unsubstantiated maltreatment (little or no evidence of maltreatment). We also examined cases of suspected maltreatment that used an alternative response to investigation (voluntary agreement to child protective services, often with no victim indicated). Finally, we examined the number of children who remained in-home with services (preventive or post–child welfare response), and the number of those children with postresponse services who were categorized as maltreated (substantiated abuse) or nonvictims (unsubstantiated abuse or alternative response).

Prevalence estimates for children in OOH care are available in the AFCARS data set. We evaluated 3 variables:

Demographic characteristics: age 0 to 21 (several states extend foster care beyond 18 years), race/ethnicity (black, white, Hispanic, biracial, other), gender.

Placement characteristics: placement type (foster care, formal kinship care, institution, group home, preadoptive home, independent living), number of placement changes (within the most recent placement episode), placement duration (from the most recent placement date until discharge date), and placement outcome/exit reason (guardianship, adoption, reunification, relative care, emancipation, agency change, runaway, child death). Consistent with previous research,13 we refer to the first 4 outcomes as “positive exits” because these are desirable permanency outcomes in child welfare.

OOH case characteristics: Maltreatment before placement (vs “other” reasons including parental death or incarceration, child disability, etc); multiple maltreatment number of different maltreatment types before placement, such as physical and sexual abuse); emotional disturbance (child has a clinical diagnosis made by a qualified professional). We considered multiple maltreatment as a proxy for the burden of childhood trauma.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to report the prevalence and patterns of maltreatment, OOH placements, and demographic and socioenvironmental factors for children in OOH care. We used an incident rate ratio (IRR) to examine the relative change in annual and cross-decade trends in data. Analysis using IRR with these data requires state-level comparison; subcategories for which responses are not recorded from every state each year show the percent relative change for the entire population but not the IRR. Given the large sample size, P values should be interpreted with caution.

Results

The Prevalence and Trends in Maltreatment and OOH Care Between 2000 and 2010

In 2000, the number of maltreatment reports eligible for investigation (suspected maltreatment) was 2 938 681. By 2010, this number increased by 595 820 cases to 3 534 501, reflecting a 20% increase across the decade (IRR 1.20; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.17–1.17).

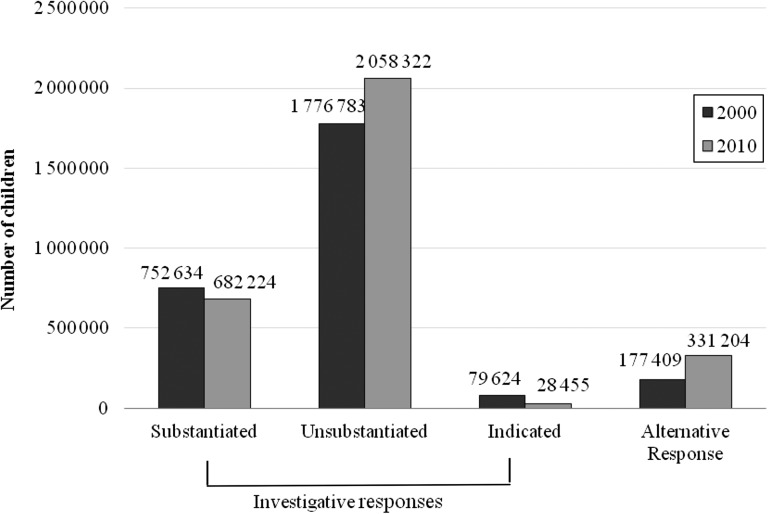

Among cases that received formal investigation across the decade (Fig 1), substantiation decreased by 70 410 (9%), unsubstantiated cases increased by 281 539 (16%), and the use of “indicated” (inadequate evidence to support suspicions) as a case outcome all but disappeared, decreasing by 51 169 (64%). There was an 87% increase (153 798 more cases) in the use of alternative response to investigation (7 additional states used this approach across the decade). As substantiated cases decreased across the decade, the number of children who remained in-home with preventive or postresponse (remedial) services increased 12% and 15%, respectively. Among those children who received services after a child welfare response, 24% fewer were categorized as maltreated and 63% more as “nonvictims.” Thus, although the number of cases deemed eligible for investigation increased between 2000 and 2010, more of these cases were offered an alternative approach to investigation. Simultaneously, fewer investigated cases were deemed substantiated and few were deemed “indicated,” whereas more children remained in-home with services.

FIGURE 1.

Child maltreatment in the United States: 2000 to 2010. Data on child maltreatment case outcomes were missing from Maryland, North Dakota, and Puerto Rico in 2000; these locations were omitted from the analysis in 2010. Total number of reports eligible for investigation was 2 938 681 in 2000 and 3 534 501 in 2010.

During this time period, fewer children were entering and exiting OOH placements (Table 1). The rate at which children were newly placed in OOH care declined 11% between 2000 and 2010. There was also a large exodus of children from OOH care between 2002 and 2008. Consequently, there was a marked decline in the number of children in OOH care. On September 30, 2010, 135 878 fewer children were in OOH placements than on the same date in 2000, representing a 25% decrease in OOH placements. The marked decline in the numbers of children in OOH care reflects both the reduction in annual placements and the large exodus that occurred from 2002 through 2008.

TABLE 1.

OOH Care in the United States: 2000–2010

| Fiscal year | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Total N in OOH care within the year | 811 855 | 813 817 | 801 481 | 788 183 | 788 437 | 797 925 | 800 374 | 783 501 | 748 571 | 700 040 | 662 540 |

| Entered OOH Care | 287 285 | 296 251 | 295 097 | 289 415 | 298 087 | 307 173 | 304 837 | 293 140 | 274 026 | 255 418 | 254 375 |

| Exited OOH Care | 267 483 | 269 176 | 278 485 | 278 443 | 280 669 | 287 074 | 295 027 | 294 753 | 288 150 | 276 266 | 254 114 |

| In OOH Care on September 30 | 544 303 | 544 614 | 522 686 | 509 713 | 507 605 | 510 699 | 505 340 | 488 744 | 460 416 | 423 773 | 408 425 |

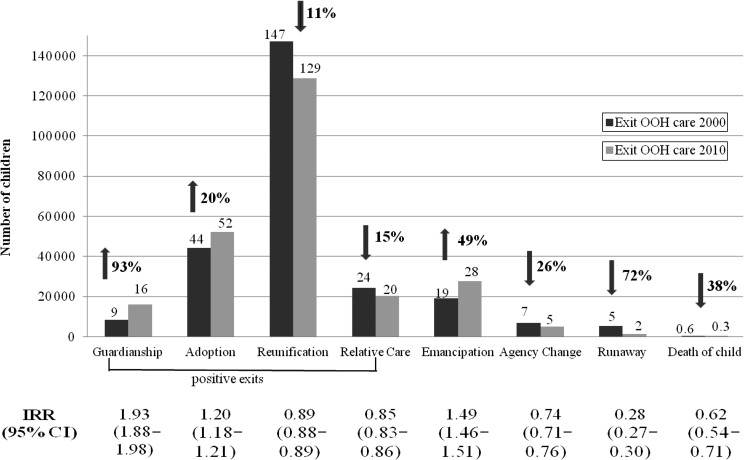

Figure 2 displays all the possible types of placement outcomes for children who exited OOH care. Positive exits (permanency) included the 7672 (93%) more children with established guardianship (left child welfare; legally supported by a relative or alternate caregiver) and the 7937 (20%) more children who were adopted. In contrast, 18 389 (11%) fewer children reunified with a birth parent, and 4021 (15%) fewer children were placed permanently with a relative who did not have guardianship (informal kinship care). Among what may be categorized as neutral or negative placement outcomes, we found an increase in those who emancipated out of foster care (no further child welfare services or support), and reductions in children who left care because of a change in agency, ran away, and died while in OOH care (Fig 2). Thus, more children achieved permanency through adoption and guardianship but fewer through reunification with parent or informally with extended family.

FIGURE 2.

Relative change in the reasons for exiting OOH Care: 2000–2010. Data labels represent numbers in thousands.

Demographic and Socioenvironmental Characteristics of Children in OOH Care and Changes in These Factors Since 2000

Demographic characteristics of children in OOH care remained similar across the decade except for a shift in racial/ethnic makeup. Among the 408 425 children in OOH care on September 30, 2010, the mean age was 8.9 years (6.0 SD), and 48% were female (Table 2). Children in 2000 were, on average, slightly older (9.6 years, 5.6 SD; P < .001), whereas adolescents aged 11 to <18 comprised the greatest proportion in both 2000 and 2010 (∼40%). Across the decade, the population of African American children in OOH care decreased 28% (IRR 0.72, 95% CI 0.71–0.72), whereas the population of Hispanic children increased 38% (IRR 1.38, 95% CI 1.36–1.39). In both 2000 and 2010, approximately half of children in OOH care were living in nonrelative family foster homes, and approximately one-quarter resided in formal kinship care.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Children in OOH Care: 2000–2010

| Characteristic | In OOH care, n (%) | IRR (CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2010 | |||

| N = 544 303 (%) | N = 408 425 (%) | |||

| Entered OOH Carea | 287 285 | 254 375 | 0.89 | — |

| Reenter OOH care with placement historyb | 57 656 (20) | 50 327 (20) | 0.98 (0.97–1.00) | .005 |

| Exit OOH carea | 267 483 | 254 114 | 0.95 | — |

| Female | 259 036 (48) | 193 998 (48) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | .32 |

| Age (y), Mean (SD)c | 9.6 (5.6 SD) | 8.9 (6.0 SD) | — | <.001 |

| 0–<3 | 74 640 (15) | 83 759 (21) | 1.41 (1.40–1.42) | <.001 |

| 3–<6 | 71 925 (14) | 66 096 (16) | 1.16 (1.15–1.17) | <.001 |

| 6–<11 | 125 862 (24) | 80 651 (20) | 0.81 (0.80–0.81) | <.001 |

| 11–<15 | 112 750 (22) | 68 921 (17) | 0.77 (0.76–0.78) | <.001 |

| 15–<18 | 105 243 (20) | 91 663 (22) | 1.10 (1.09–1.10) | <.001 |

| ≥18 | 23 422 (5) | 17 303 (4) | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | <.001 |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 206 235 (41) | 117 610 (29) | 0.72 (0.71–0.72) | <.001 |

| White | 197 094 (39) | 165 135 (41) | 1.06 (1.05–1.06) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 77 544 (15) | 84 727 (21) | 1.38 (1.36–1.39) | <.001 |

| Multiracial | 7458 (1) | 21 752 (5) | 3.68 (3.58–3.77) | <.001 |

| Other | 16 010 (3) | 11 026 (3) | 0.87 (0.85–0.89) | <.001 |

| Placement durationc | 32.4 (34.9SD) | 25.5(32.0SD) | — | <.001 |

| Total placements (during the current removal episode) Mean (SD)c | 2.9 (3.0 SD) | 3.1 (3.5 SD) | — | <.001 |

| Maltreatment before careb (total n) | ||||

| 0 | 135 240 (28) | 65 133 (17) | 0.62 (0.62–0.63) | <.001 |

| 1 | 244 300 (50) | 204 665 (54) | 1.08 (1.08–1.09) | <.001 |

| 2 | 82 929 (17) | 89 449 (24) | 1.39 (1.38–1.40) | <.001 |

| 3 | 17 869 (4) | 17 437 (5) | 1.26 (1.23–1.29) | <.001 |

| 4 | 4797 (1) | 2386 (1) | 0.64 (0.61–0.67) | <.001 |

| 5 | 4563 (1) | 60 (0) | 0.02 (0.01–0.02) | <.001 |

| Emotional disturbance | 51 695 (11) | 61 771 (17) | 1.60 (1.58–1.62) | <.001 |

P values were not calculated on values representing the total population.

Among children newly entering care within the fiscal year.

Incident rate ratio (IRR) not calculated for mean values.

Among children who exited care, the mean length of stay decreased from 32.4 months (SD 34.9) in 2000 to 25.5 months (SD 32.0) in 2010 (P < .001). The mean number of placement changes children experienced while in OOH care increased slightly, from 2.9 (3.0 SD) changes in 2000 to 3.1 (3.5 SD) in 2010 (P < .001).

Number of Types of Maltreatment Before Placement and Child Emotional Disturbance

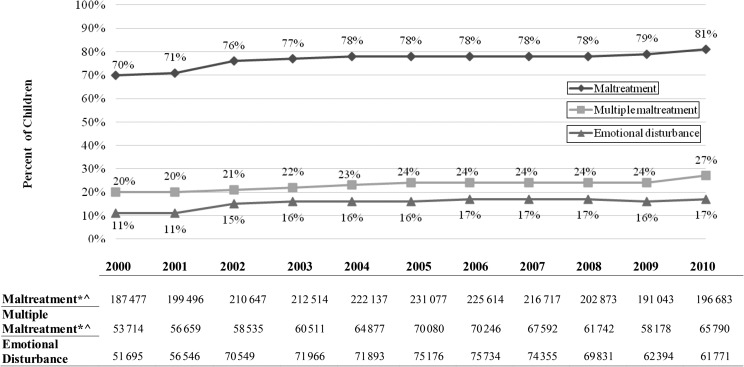

The number and relative percentage of children entering OOH care because of maltreatment increased by 17% (IRR 1.17, 95% CI 1.16–1.17) across the decade, from 187 477 (70%) in 2000 to 196 683 (82%) in 2010 (Fig 3). Similarly, the number of children who experienced multiple maltreatment before entry increased by more than one-third (IRR 1.36, 95% CI 1.35–1.37) from 53 714 (20%) in 2000 to 65 790 (27%) in 2010. We examined this trend by placement type (Table 3) and found increases in preplacement multiple maltreatment from 2000 to 2010 among children placed in formal kin care (31% increase), foster care (34% increase), group homes (38% increase), and institutional settings (29% increase), whereas there was no change among children placed in independent living and a 14% decrease among children placed in preadoptive homes. Thus, children placed in OOH care in 2010 appeared to have a greater burden of previous maltreatment experiences than those placed in 2000. Children in preadoptive placements had a lower rate of previous maltreatment across the decade.

FIGURE 3.

Number and relative percent of maltreatment and emotional disturbance among children in OHO Care. *Data from Alaska and New York were omitted from analysis because >20% of values were missing. ^Among children newly entering care within the fiscal year.

TABLE 3.

Trends in Multiple Maltreatment and Emotional Disturbance by Placement Type: 2000–2010

| Multiple Maltreatment | Emotional Disturbance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2010 | IRR | 2000 | 2010 | IRR | |

| n (%) | n (%) | (95% CI) | n (%) | n (%) | (95% CI) | |

| Preadoptive | 936 (30) | 449 (26) | 0.86 (0.79–0.96) | 195 (6) | 153 (10) | 1.54 (1.26–1.89) |

| Formal kin care | 15 305 (26) | 23 895 (34) | 1.31 (1.29–1.34) | 1496 (3) | 2625 (4) | 1.55 (1.45–1.65) |

| Foster care | 25 638 (20) | 30 052 (27) | 1.34 (1.32–1.36) | 6471 (5) | 7305 (7) | 1.33 (1.29–1.37) |

| Group home | 2577 (10) | 2163 (13) | 1.38 (1.31–1.46) | 2557 (10) | 3403 (23) | 2.40 (2.29–2.51) |

| Institution | 3930 (10) | 2977 (13) | 1.29 (1.24–1.35) | 5179 (15) | 4746 (25) | 1.64 (1.58–1.70) |

| Independent living | 163 (16) | 103 (16) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 116 (12) | 100 (17) | 1.44 (1.12–1.84) |

Finally, we examined the prevalence of children in OOH care with emotional disturbance (Fig 3). Despite the overall decrease in the number of children in OOH placements, both the number and the rate of children in OOH care with reported emotional disturbance increased by 60% (IRR 1.60, 95% CI 1.58–1.62) across the decade, from 11% (n = 51 695) in 2000 to 17% (n = 61 770) in 2010. We found increases in emotional disturbance across all placement types, with children placed in group homes experiencing the greatest increase (140% increase) from 2000 (10%) to 2010 (23%).

Discussion

Our study examined national trends in child welfare from 2000 through 2010. We found that although the number of investigated referrals for suspected child maltreatment increased over 11 years, there was a surprising decrease in substantiated maltreatment and an even greater decline in the total number of children in OOH care, because fewer children entered foster care, and the use of alternative permanency options (adoption and guardianship) increased. Also, there was an increase in the numbers of children with multiple forms of maltreatment before placement and those diagnosed as having emotional disturbance. Our data indicate, therefore, that the child welfare system is now caring for fewer children but for larger numbers with complex trauma histories and emotional and mental health needs.

Potential Explanations for Trends in Maltreatment and OOH Care

Preventive Efforts

The decline in suspected cases of maltreatment and OOH placements occurred after 2 decades of increasing placements. Shifts in child welfare policy and practice reflected the explosion in scientific knowledge about the impact of childhood trauma on physical, cognitive, and behavioral development,14–17 and the important role the attachment relationship has in long-term social, health and mental health outcomes.18–20 Child advocates used this information to lobby for major legislation to promote stability and permanency requiring states to (1) expedite termination of parental rights when necessary and provide enhanced support to encourage foster parents to adopt (Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997; ASFA, P.L. 105-89) and (2) increase supports and resources for kinship care and adoption and promote guardianship as an alternative when reunification and adoption are not feasible (Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008; FC, P.L. 110-351). Adoptions increased beginning a few years after ASFA was enacted. Although the latter legislation occurred toward the end of the decade, it reflected major changes in policy and practice already underway. Some jurisdictions began reserving formal child protective investigation for the highest risk cases while providing a voluntary intervention, alternative resources, to families considered lower risk.9 Child welfare also expanded in-home services intended to prevent OOH placement, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network advocated and provided support for integrated, trauma-informed systems in child welfare and evidence-based interventions for children who had experienced trauma.21

We postulate that these changes in policy and practice contributed to the decrease in substantiated maltreatment and to the even greater decrease in the number of children in OOH placements from 2000 to 2010. We cannot, however, link specific policy or practice changes with changing trends in OOH care, and we do not know if children who remained home continued to experience adversity. We are also unable to directly connect these changes with the increased trauma experienced by children entering OOH care. Nevertheless, although there may be other explanations for these trends (such as an overburdened child welfare system with resource restrictions), our findings are highly suggestive that shifts in child welfare policy and practice resulted in a smaller, more complex OOH care population.

Trends in the Severity of Needs of the OOH Care Population

Our findings suggest that the OOH care population is even more complex than a decade earlier; although there are fewer children in OOH care, a higher proportion of them appear to have a greater history of trauma and more complex needs. Indeed, our data may underestimate the health burden of the OOH population because the information available in these data sets is limited. For example, other studies reported that 36% to >70% of children in OOH care have a mental health problem.22–24

To meet the needs of the increasingly fragile and traumatized OOH population, additional policy and practice change intended to strengthen OOH care systems may be necessary. OOH caregivers are often the primary therapeutic agents for children in OOH care,10 yet many feel unqualified for this role when children have severe emotional problems.25 Enhanced training for OOH caregivers seems to improve mental health outcomes among these children.26,27 Thus, providers who are educated and supported may help alleviate the mental health burden of children in OOH care.

Outcomes of Children Remaining at Home

The small reduction in substantiated cases was disproportionate to the larger reduction in the OOH care population, suggesting that more maltreated children remained at home after adjudication. Although these trends resulted from focused efforts to prevent OOH placement, some evidence indicates that stable long-term placement in foster care can have positive effects on development28,29 and that children returning home after being in foster care have worse behavioral outcomes than children remaining in foster care.30,31 More detailed information is needed about the outcomes of children who remain at home.

Strengths and Limitations

The data provide us with information on the population of US children who were maltreated or in OOH care during the period of this study, allowing for accurate description of population trends and characteristics. The primary limitation of this study is the use of administrative data, which may have inconsistencies in data collection methods and limited data elements of interest. Although our data showed that more children entered than exited OOH care annually as the total number of children in OOH care declined, this reflects a quirk in data collection because the numbers of children entering and leaving care did not represent an unduplicated count, whereas the number of children in OOH care did. Second, AFCARS used nonstandardized measures of emotional disturbance, and this database lacks detailed information about the mental health of the children. Third, we do not know how much of the increased trends seen reflect improved identification of maltreatment and emotional issues. Finally, data on maltreatment did not include information from all states.

Conclusions

Despite a substantial increase in the number of child welfare investigations over the past decade, the rate and number of substantiated maltreatment and foster care placement declined, whereas use of alternative permanency options increased (adoption and guardianship). These changes appear to have resulted in a smaller but more complex population of children in OOH care who have greater trauma histories and current emotional disturbance than the OOH care population of the past. Studies are needed to more clearly delineate optimal care for this high-risk OOH population and to assess the impact of these major trends on the child welfare population.

Acknowledgments

The data (and tabulations) used in this publication were made available in part by the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York. The data from the Substantiation of Child Abuse and Neglect Reports Project were originally collected by John Doris and John Eckenrode. Funding support for preparing the data for public distribution was provided by a contract (90-CA-1370) between the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect and Cornell University. Neither the collector of the original data, funding agency, nor the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect bears any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

We acknowledge Constance D. Baldwin, PhD, for her contribution to the writing of this manuscript.

Glossary

- AFCARS

Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System

- CI

confidence interval

- IRR

incident rate ratio

- NCANDS

National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System

- OOH

out of home

Footnotes

Dr Conn conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated the data approvals and maintenance, and drafted the initial manuscript; Dr M. Szilagyi participated in the study conceptualization and design and critically reviewed the manuscript; Dr Franke participated in the study design and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Albertin participated in the study design and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Mr Blumkin carried out the statistical analysis and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr P Szilagyi conceptualized the study, participated in the study design, and critically reviewed the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

This work was presented in part at the 2012 American Academy of Pediatrics Presidential Plenary Session of the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: All phases of this study were supported by a National Institutes of Health T32 training grant (0258-3627/HHSN275201100002C). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.U.S. House of Representatives. 2000 Green Book: Overview of entitlement programs. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000. Available at: www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-CPRT-106WPRT61710/pdf/GPO-CPRT-106WPRT61710-1.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swann CA, Sylvester MS. The foster care crisis: what caused caseloads to grow? Demography. 2006;43(2):309–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Clark DB, et al. A.E. Bennett Research Award. Developmental traumatology Part II: Brain development. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45(10):1271–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galvin MR, Stilwell BM, Shekhar A, Kopta SM, Goldfarb SM. Maltreatment, conscience functioning and dopamine β hydroxylase in emotionally disturbed boys. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21(1):83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollak S, Cicchetti D, Klorman R. Stress, memory, and emotion: developmental considerations from the study of child maltreatment. Dev Psychopathol. 1998;10(4):811–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen JP, Hauser ST, Borman-Spurrell E. Attachment theory as a framework for understanding sequelae of severe adolescent psychopathology: an 11-year follow-up study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(2):254–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobsen T, Edelstein W, Hofmann VA. A longitudinal study of the relation between representations of attachment in childhood and cognitive functioning in childhood and adolescence. Dev Psychol. 1994;30(1):112–124 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyons-Ruth K, Easterbrooks MA, Cibelli CD. Infant attachment strategies, infant mental lag, and maternal depressive symptoms: predictors of internalizing and externalizing problems at age 7. Dev Psychol. 1997;33(4):681–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldfogel J. Rethinking the paradigm for child protection. Future Child. 1998;8(1):104–119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orme JG, Buehler C. Foster family characteristics and behavioral and emotional problems of foster children: A narrative review. Fam Relat. 2001;50(1):3–15 [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment Reports. 2000–2010. Available at: www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment. Accessed August 20, 2013

- 12.National Child Abuse and Neglect Data Archive. Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS): User’s Guide and Codebook for Fiscal Years 2000 to present. Ithaca, NY: National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price JM, Chamberlain P, Landsverk J, Reid JB, Leve LD, Laurent H. Effects of a foster parent training intervention on placement changes of children in foster care. Child Maltreat. 2008;13(1):64–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Chernoff R, Combs-Orme T, Risley-Curtiss C, Heisler A. Assessing the health status of children entering foster care. Pediatrics. 1994;93(4):594–601 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clausen JM, Landsverk J, Ganger W, Chadwick D, Litrownik A. Mental health problems of children in foster care. J Child Fam Stud. 1998;7(3):283–296 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halfon N, Berkowitz G, Klee L. Mental health service utilization by children in foster care in California. Pediatrics. 1992;89(6 pt 2):1238–1244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Hara MT, Church CC, Blatt SD. Home-based developmental screening of children in foster care. Pediatr Nurs. 1998;24(2):113–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szilagyi M. The hand on the door. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(2):105–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumaret A-C, Coppel-Batsch M, Couraud S. Adult outcome of children reared for long-term periods in foster families. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21(10):911–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor NS, Siegfried C. Helping children in the child welfare system heal from trauma: A systems integration approach. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Available at: www.nctsn.org/nctsn_assets/pdfs/promising_practices/A_Systems_Integration_Approach.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oswald SH, Heil K, Goldbeck L. History of maltreatment and mental health problems in foster children: a review of the literature. J Pediatr Psychol. 35(5):462–472 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Jee SH, Conn A-M, Szilagyi PG, Blumkin A, Baldwin CD, Szilagyi MA. Identification of social-emotional problems among young children in foster care. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(12):1351–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Wagner HR, et al. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: a national survey. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):960–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buehler C, Rhodes KW, Orme JG, Cuddeback G. The potential for successful family foster care: conceptualizing competency domains for foster parents. Child Welfare. 2006;85(3):523–558 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conn AM. Examining the Relationship Between Parenting Style, the Home Environment, and Placement Stability for Children in Foster Care [doctoral dissertation]: Psychology, Capella University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simms MD, Horwitz SM. Foster home environments: a preliminary report. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1996;17(3):170–175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horwitz SM, Balestracci KM, Simms MD. Foster care placement improves children’s functioning. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(11):1255–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLaughlin KA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA. Attachment security as a mechanism linking foster care placement to improved mental health outcomes in previously institutionalized children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):46–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellamy JL. Behavioral problems following reunification of children in long term foster care. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2008;30(2):216–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taussig HN, Clyman RB, Landsverk J. Children who return home from foster care: a 6-year prospective study of behavioral health outcomes in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):E10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]