Abstract

Elevated numbers of activated platelets circulate in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases including atherosclerosis and coronary disease. Activated platelets can activate the complement system. Although complement activation is essential for immune responses and removal of spent cells from circulation, it also contributes to inflammation and thrombosis, especially in patients with defective complement regulation. Pro-inflammatory activated leukocytes, which interact directly with platelets in response to vascular injury, are among the main sources of properdin, a positive regulator of the alternative pathway. The role of properdin in complement activation on stimulated platelets is unknown. Here, the data show that physiological forms of human properdin bind directly to human platelets after activation by strong agonists, in the absence of C3, and non-proportionally to surface CD62P expression. Activation of the alternative pathway on activated platelets occurs when properdin is on the surface and recruits C3b or C3(H2O) to form C3b,Bb or a novel cell-bound C3 convertase [C3(H2O),Bb], which is normally present only in the fluid phase. Alternatively, properdin can be recruited by C3(H2O) on the platelet surface, promoting complement activation. Inhibition of factor H-mediated cell surface complement regulation significantly increases complement deposition on activated platelets with surface properdin. Finally, properdin released by activated neutrophils binds to activated platelets. Altogether, these data suggest novel molecular mechanisms for alternative pathway activation on stimulated platelets that may contribute to localization of inflammation at sites of vascular injury and thrombosis.

Keywords: complement, properdin, platelet, C3, alternative pathway

Introduction

Platelets are small and anucleate circulating particles that derive from bone marrow megakaryocytes. These cells play a central role in hemostasis, inflammation and also in diseaserelated thrombosis, as they are the first circulating blood cells that, upon activation, rapidly adhere to tissue, to leukocytes (recruitment), and to one another, in response to vascular injury (1, 2). However, excessive or inadvertent platelet activation is common at sites of endothelial damage, underlying many cardiovascular disorders, such as myocardial infarction, unstable angina, and stroke (3). Patients with chronic inflammatory conditions such as unstable atherosclerosis, hypercholesterolemia, and coronary disease have a higher number of activated platelets (4, 5) and platelet/leukocyte aggregates (6) circulating in the blood.

Stimulated platelets activate the complement system on or near their surface (7–12). In general, normal inflammatory processes require complement activation for an effective immune response, as well as for efficient removal of spent cells from circulation. In pathological acute and chronic inflammatory diseases (i.e. systemic lupus erythematosus, cancer, atherosclerosis, ischemia/reperfusion injury, neuroinflammation, among others), excessive complement activation contributes to tissue damage and leads to elevated release of pro-inflammatory by-products (i.e. C5a, C3a) and C5b-9 end product (MAC) (13), which in turn participate in leukocyte recruitment, vascular inflammation, platelet activation, and thrombosis (14, 15). Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms by which complement activates on stimulated platelets becomes essential for understanding its role in platelet-mediated physiology and disease pathogenesis. Both the classical (7) and the alternative pathways (9) have been shown to activate on the platelet surface, despite the presence of complement regulatory proteins. In addition, individuals with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) or atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), diseases in which the activity of one or more complement regulatory proteins (i.e. factor H, CD59, CD55, CD46) is impaired (16, 17), have exacerbated complement activation on their platelets (18, 19). However, recent studies indicate that complement activates in the microenvironment surrounding the stimulated platelet upon release of chondroitin sulfate A (10), but not on the platelet surface, when complement regulation is intact (11). Therefore, the mechanisms by which complement activates on stimulated platelets remain controversial.

The alternative pathway of complement represents a true safeguard system of the human host and is initiated in the fluid phase by the spontaneous hydrolysis of the thioester bond in C3 to produce C3(H2O), which is functionally and structurally similar to C3b (20) (tickover theory; reviewed in (21)). Binding of factor B to C3(H2O) in the presence of factor D allows the generation of an unstable fluid-phase C3 convertase (C3(H2O),Bb), which has the ability to digest C3 to generate C3b fragments (22). The C3b fragments can then bind to any nearby surface with exposed amino or hydroxyl groups (23). Factor B can then bind to this membrane-bound C3b and be cleaved by factor D, to generate the membrane-bound alternative pathway C3 convertase (C3b,Bb) (24). Properdin, the only known positive regulator of the alternative pathway, stabilizes the C3b,Bb complex, increasing its half life by 5 to 10 fold (25), making possible the efficient amplification of C3b deposition on target surfaces (24). Del Conde et al. (9) have shown that C3b binds directly to activated platelets by using P-selectin (CD62P) as a receptor, and proposed this as a mechanism by which alternative pathway activation occurs on the surface of activated platelets. On the other hand, Hamad et al. (11) detected binding of only C3(H2O) to stimulated platelets, which was not the result of proteolytic cleavage of C3 or alternative pathway complement activation.

Properdin is found in plasma at a concentration of 4–25 µg/ml (26). It is mainly produced by leukocytes, including monocytes (27), T cells (28), and neutrophils (29). These cells release properdin upon stimulation with TNF-α, PMA, C5a and fMLP, and may significantly increase the local concentration of properdin, especially at sites of inflammation (reviewed in (30, 31)). Shear-stressed endothelial cells can also produce properdin (32). The 53 kDa properdin monomers associate in a head to tail manner, generating dimeric (P2), trimeric (P3) and tetrameric (P4) physiological forms of properdin that are present in plasma in a ratio of 26:54:20 ((33); reviewed in (31)). Recently, we and others have reported that properdin, besides stabilizing the alternative pathway convertases, acts as a highly selective pattern recognition molecule by binding directly to certain surfaces (i.e. apoptotic and necrotic cells (34–37) and Chlamydia pneumoniae (38)), and serving as a platform for de novo C3b,Bb assembly (reviewed in (31)). In this study we have investigated the role of properdin in complement activation on platelets, because among the main sources of properdin are activated granulocytes and monocytes that (a) interact with platelets during inflammatory and thrombotic syndromes (forming platelet/leukocyte aggregates) (reviewed in (39)) and (b) are present in increased numbers at sites of physiological and pathological inflammation where platelets and complement play essential roles.

Here, our data shows that alternative pathway complement activation on activated platelets occurs when properdin is bound to stimulated, but not resting, platelets. Properdin binds to activated platelets in a manner that is not proportional to CD62P surface exposure, the level of binding varies depending on the platelet agonist used, and does not require the presence of C3 fragments on the platelet surface. The platelet-bound properdin recruits C3(H2O) and/or C3b to the surface of activated platelets and forms a novel cell-bound C3(H2O) convertase [C3(H2O),Bb] or C3b,Bb. Moreover, C3(H2O) on the platelet surface can also initiate complement activation by recruiting properdin and factor B. Finally, properdin freshly secreted by stimulated polymorphonuclear leukocytes binds to activated platelets. Our results define a novel molecular mechanism by which the alternative pathway of complement activates on stimulated platelets that is mediated by the physiological forms of properdin and C3(H2O).

Materials and Methods

Buffers

The buffers used were: citrate buffer (9.35 mM Na3Citrate, 4.75 mM Citric acid, 17.35 mM Dextrose, 145 mM NaCl, pH 6.5); Tyrode’s buffer (136.9 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 983.8 µM MgCl2 6H2O, 3.2 mM Na2HPO4, 3.5 mM HEPES, 0.35% BSA, 5.5 mM Dextrose, 2 mM CaCl2; pH 7.4); Tyrode/PGE/Hep buffer (Tyrode’s buffer containing 1µM Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) and 2 IU/mL Heparin); GVB= (5mM veronal, 145mM NaCl, 0.004% NaN3, 0.1% Gelatin); Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 140 mM NaCl, 0.02% NaN3, pH 7.4); Mono S buffer A (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.0); Mono S buffer B (50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 6.0); Mg-EGTA buffer stock (0.1 M MgCl2, 0.1 M EGTA, pH 7.3).

Antibodies

The following murine monoclonal antibodies were used in this study: IgG1 anti-human properdin (#1; Quidel), IgG1 isotype control (eBioscience), IgG1 anti-human C3/C3b (Cedarlane), PE-conjugated IgG1 anti-human C3/C3b (Cedarlane), APC-conjugated IgG1 anti-human CD42b (Biolegend), PE/Cy5-conjugated IgG1 anti-human CD62P (Biologend), IgG2a anti-human C5b-9 neo-epitope (Dako), IgG2a anti-human factor Bb neoantigen (Abd Serotec), AF488-conjugated IgG1 anti-human CD11b (Biolegend), and PE-conjugated IgG2a anti-human CD16b (Biolegend). The following polyclonal antibodies were used: AF488-conjugated goat anti-mouse polyclonal IgG (Invitrogen), F(ab’)2 polyclonal goat anti-C3b IgG (LifeSpan BioSciences).

Serum and complement proteins

Purification of properdin (34) and C3 (40), and the generation of C3b (41) were carried out as previously described in the cited references. Properdin-depleted serum, normal human serum (NHS), factor D, and factor B were purchased from CompTech.

Separation of physiological forms of properdin

Physiological polymeric forms of properdin (P2-P4) were separated from non-physiological aggregated forms (Pn) by gel filtration chromatography. The Pn forms are known to accumulate after prolonged storage and freeze/thaw cycles and induce non-specific complement activation in solution (33) and on certain surfaces ((34); reviewed in (31)). Briefly, pure properdin (5 mg) was loaded onto a Phenomenex Bio Sep-Sec-S4000 column (600 × 7.8 mm) with a guard column (75 × 7.8 mm), and eluted at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min in PBS. Purified, physiological forms of properdin were stored at 4°C and used within two weeks of separation, as previously described (33, 34).

Platelet isolation and activation

Human platelets were isolated via venipuncture from the blood of healthy donors. The Institutional Review Board from the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences approved protocols, and written informed consent was obtained from all donors, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Blood was drawn into ACD tubes (BD Vacutainer) and platelet rich plasma was separated by centrifugation at 200g for 15 min at room temperature (RT) with no brake. The platelet rich plasma was collected and platelets were washed twice using citrate buffer at 440g for 10 min at RT. Platelets were resuspended to a final concentration of 1×108 cells/ml in Tyrode’s buffer. Agonists used to activate the platelets included thrombin (Sigma) at 1 IU/ml (or varying doses as specified in the figure legends), arachidonic acid (Chronolog) at 1 mM (or varying doses as specified in the figure legends), or ADP (Sigma) at 20 µM for 30 min at 37°C. The platelets were then washed once with Tyrode/PGE/Hep buffer (to prevent further platelet activation and aggregation) by centrifuging at 2000g for 10 min at RT. To assess platelet activation, expression of CD62P (using PE/Cy5-mouse IgG anti-human CD62P) was detected on CD42b+ (APC-mouse IgG anti-human CD42b) platelets. Finally, platelets were washed and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C, prior to acquisition using BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). A minimum of 10,000 events per sample were acquired and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software version 7.6.5.

Measurement of properdin binding to platelets

Non-activated, thrombin-activated, arachidonic acid-activated, or ADP-activated platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated with properdin P2-P4 forms (0–25 µg/ml) in Tyrode/PGE/Hep for 1 hour at RT. Platelets were washed twice with Tyrode/PGE/Hep by centrifuging at 2000g for 10 min at RT. Binding of properdin was assessed by flow cytometry using an anti-properdin monoclonal antibody, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. After washing, platelets were stained with APC-mouse anti-human CD42b and with PE/Cy5-mouse anti-human CD62P. Finally, platelets were washed, fixed, and the data were acquired and analyzed as described in the previous section. In some experiments, properdin was added to the activated platelets or to C3b-coated sheep erythrocytes (ESC3b; control) in the presence of F(ab’)2 polyclonal goat anti-C3b antibodies.

Measurement of alternative pathway complement activation on platelets (C3b and C5b-9 deposition)

Non-activated, thrombin-activated, or arachidonic acid-activated platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated in the absence or presence of properdin. Washed platelets were then incubated with properdin-depleted serum (60%) for various time points at 37°C. In separate experiments, platelets were used at 2×106 platelets/100 µl and were incubated with the properdin-depleted serum as described above, but in the presence of 25 µM rH19–20, a competitive inhibitor of factor H-mediated cell surface regulation (17, 42–45). In all experiments, platelets were incubated with serum in the presence of 5 mM Mg-EGTA to selectively measure complement activation by the alternative pathway. Negative controls were incubated with serum in presence of 10 mM EDTA to inhibit complement activation. Complement activation was stopped by washing samples with cold Tyrode’s buffer containing 10 mM EDTA. Deposition of C3b was detected using PE-anti C3/C3b or an unlabeled anti-C3b monoclonal antibody followed by AF488-goat anti-mouse IgG. Similarly, C5b-9 was detected using anti-C5b-9 neo-epitope antibody followed by AF488-goat anti-mouse IgG. The platelets were stained with APC-mouse anti-human CD42b and PE/Cy5-mouse anti-human CD62P and analyzed as described above.

Separation of C3 and C3(H2O)

C3(H2O) was separated from C3 by cation exchange chromatography as described previously (40). Briefly, C3 was incubated at 37°C for 2 hours to convert intermediate/inactive forms of C3 to C3(H2O). The sample was diluted with Mono S buffer A and loaded onto a 1 ml Mono S column. The column was washed with buffer A, and eluted using a 20 ml salt gradient (0–100%) of buffer B at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Purified C3 and C3(H2O) were dialyzed against PBS, stored at 4°C and used within two weeks of separation.

Measurement of recruitment to the platelet surface of C3 components by properdin and of properdin by C3(H2O)

Non-activated, thrombin-activated, or arachidonic acid-activated platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated with or without properdin (25 µg/ml) in Tyrode/PGE/Hep for 1 hour at RT. Platelets were washed twice with Tyrode/PGE/Hep and then incubated with C3, C3b, or C3(H2O) (100 µg/ml), or, in the case of thrombin-activated platelets, with varying concentrations of C3(H2O) (0–100 µg/ml). Binding of C3 components was assessed by flow cytometry using an anti-C3 monoclonal antibody, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. Alternatively, the activated platelets were incubated with C3(H2O) (100 µg/ml) first, followed by washing and subsequent incubation with P3 (0–25 µg/ml). Binding of properdin was assessed by flow cytometry as described above.

Measurement of C3 convertase [C3(H2O),Bb and C3b,Bb] formation on platelets

Thrombin-activated or arachidonic acid-activated platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated with one of the following for 1 hour at RT: (a) Tyrode’s buffer alone, (b) properdin (25 µg/ml), (c) C3(H2O) (50 or 100 µg/ml), (d) C3b (50 or 100 µg/ml), or (e) first with properdin, followed by washing, and then C3(H2O) or C3b (1 hour each). Alternatively, C3(H2O) or C3b was added first, followed by washing and then properdin (1 hour each). After washing, the ability to form Bb was assessed by resuspending the pellet in 100µl of factor D (2 µg/ml) along with factor B (80 µg/ml) for 30 min at RT. The formation of Bb was assessed by flow cytometry using anti-human complement factor Bb neo-epitope monoclonal antibody followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. The platelets were then stained with APC-mouse anti-human CD42b and PE/Cy5-mouse anti-human CD62P and analyzed as described in the preceding section.

PMN isolation, activation, and assessment of properdin binding to stimulated platelets

Fresh blood was drawn from healthy volunteers into EDTA tubes (BD Vacutainer). Polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells were isolated by using a Polymorphprep™ gradient (Axis-Shield PoC AS) following manufacturer’s instructions (>90% pure PMN). PMN cells (2.5×107 cells/ml), in HBSS+2 (Gibco) + 0.2% BSA, were activated using phorbol 12 myristate 13 acetate (PMA; 10 ng/ml) (Enzo Life Sciences) for 30 min at 37°C, as previously described (29). The supernatant was collected after centrifuging the cells at 600g for 10 min at 4°C and centrifuged again at 13,000g for 10 min to remove cell debris. HALT protease inhibitor (Thermo Scientific) was added (1:100) to the supernatant. Activation of PMN was verified by flow cytometry by double-gating on FSC and SSC for PMN cells and on CD16b positive cells, and measuring levels of CD11b on the gated population. Supernatant (50 µl) of PMA-activated neutrophils was incubated with non-activated or thrombin-activated (1 U/ml) platelets (2×106) in a final reaction volume of 100 µl containing 10 mM EDTA to avoid complement activation in the supernatant. Binding of properdin was assessed by flow cytometry using an anti-properdin monoclonal antibody or an IgG1 isotype control, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. After washing, platelets were stained with APC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD42b to gate on the platelet population, as well as with PE/Cy5-mouse anti-human CD62P to assess platelet activation and analyzed as described above.

Statistics

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 4.0 software. Unpaired Student’s t tests were used to assess the statistical significance of the difference between the groups assessed for properdin binding, CD62P expression, or C3b or C5–9 deposition. One way analysis of variance Dunnett’s Multiple comparison test was used when comparing all the conditions of resting and thrombin-stimulated platelets incubated with different C3 components (C3, C3(H2O), C3b) in the presence or absence of properdin. Unpaired Student’s t tests were used to determine significance of differences in binding of C3 components to arachidonic acid-activated platelets (with or without properdin). Two way analysis of variance-Bonferroni’s posttest was applied to determine statistical significance of whether properdin recruits C3(H2O) to the surface of activated platelets, or vice versa, at different C3(H2O) or properdin concentrations, respectively.

Results

The physiological forms of properdin bind to activated, but not resting, platelets

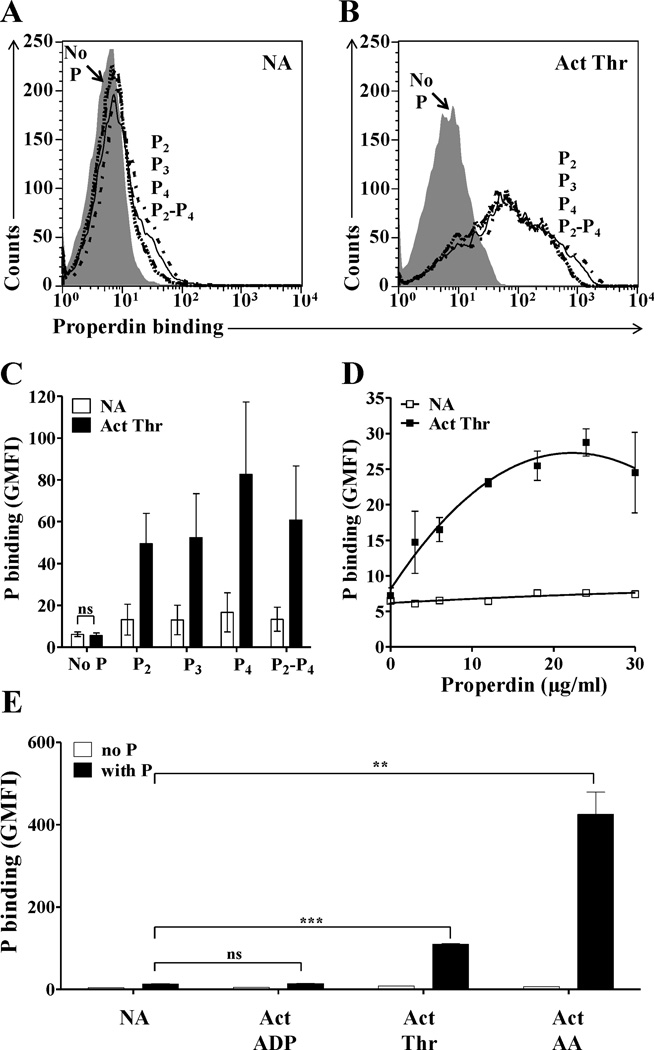

Various studies suggest that properdin selectively recognizes certain surfaces, such as apoptotic or necrotic cells and pathogens (31, 34, 35, 37, 38, 46) leading to de novo convertase assembly and alternative pathway complement activation. Considering the importance of the complement system activation in vascular inflammation, thrombosis, and thrombocytopenia, we examined the ability of properdin to bind platelets. Properdin subjected to prolonged storage and/or freeze/thaw cycles is known to accumulate non-physiological, high molecular weight aggregates (Pn) (33, 47) that can consume complement in solution (33) and bind non-specifically to surfaces (34, 48); reviewed in (31)). Therefore, the native physiological forms of properdin (P2, P3 and P4) were separated from the non-physiological forms (Pn) by gel filtration chromatography, as previously described (34). We tested the binding of the physiological forms of properdin to washed non-activated (Fig. 1A) and thrombin-activated platelets (Fig. 1B), and the data indicate that P2, P3 and P4 bind only to activated platelets (Fig. 1B–C) in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 1D). Unseparated properdin, which has non-physiological Pn forms, bound to both non-activated and activated platelets (Fig. S1), confirming the importance of eliminating the Pn forms from the raw preparation before testing.

FIGURE 1.

Analysis of binding of physiological forms of properdin to activated platelets stimulated by different agonists. Non-activated (NA) (A) or thrombin-activated (Act Thr) (B) platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated in the presence or absence of 25 µg/ml of P2, P3, P4 or P2-P4 pool (in a ratio of 1:2:1) for 30 min at RT in Tyrode/PGE/Hep buffer. Platelets were washed and binding of properdin was assessed by FACS using an anti-properdin monoclonal antibody, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. (C) Graphical representation of properdin binding to thrombin-activated platelets, as determined in A and B, and expressed as means and standard deviations (SD) of triplicate geoMean fluorescence intensity (GMFI) values. (D) Dose dependent binding curve of properdin (0–30 µg/ml) to NA and thrombin-activated platelets. (E) Binding of properdin (25 µg/ml) to NA platelets and to platelets activated with ADP (20µM), thrombin (1 IU/ml) or arachidonic acid (1mM). For all experiments, APC-labeled anti-CD42b monoclonal antibody was used to gate on the platelet population. Statistical significance was assessed by determining the p-value using an unpaired t-test (p<0.01(**) and p<0.001(***)). In (C) the differences between the ability of properdin to bind to activated platelets versus non activated platelets were all significant (p<0.05). Results are representative of 3 separate experiments shown as means and standard deviations of triplicate observations.

The level of properdin binding to platelets depends on the agonist, but is not proportional to the level of exposure of P-selectin (CD62P)

The extent to which stimulated platelets activate complement on or near their surface, when exposed to plasma or serum, is higher on platelets stimulated with strong agonists versus weak agonists (7, 8). Therefore, we sought to determine whether platelets activated by different agonists would preserve the ability to bind properdin. Platelets were activated with thrombin, arachidonic acid (strong agonists), or ADP (weak agonist), and compared in their ability to bind properdin. The data in Fig. 1E show that the binding of properdin to platelets stimulated with arachidonic acid is ~4-fold higher than thrombin-stimulated platelets, while no binding of properdin was detected to ADP-activated platelets. Thus, in Fig. 1, the use of thrombin-activated platelets allowed more stringent conditions for assessing significance of properdin binding, because these platelets bind notably less properdin than arachidonic acid activated platelets.

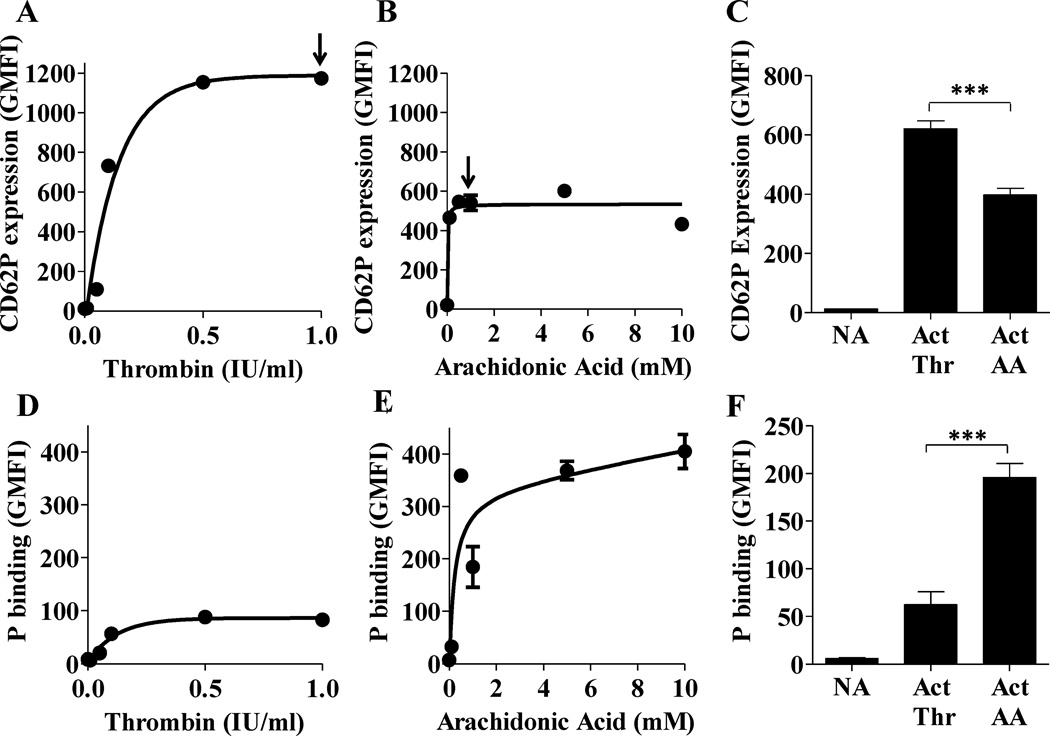

It has been shown that alternative pathway complement activation on platelets requires CD62P (9). The maximum CD62P levels on thrombin- and arachidonic acid- activated platelets were achieved with <1 U/ml or <1 mM, respectively (Figs. 2A–B, indicated by arrow). As expected, platelet activation, as measured by exposure of CD62P, varied between the different stimuli (thrombin > arachidonic acid; Fig. 2A–C). Interestingly, although the maximum level of CD62P expression is significantly higher (~1.5–2 fold) on platelets stimulated with thrombin (Figs. 2A,C) versus arachidonic acid (Fig. 2B–C), the binding of properdin to the arachidonic acid-activated platelets (Fig. 2E–F) is significantly higher (~3 fold) than to the thrombin-activated group (Fig. 2D,F). Altogether, these data suggest that the binding of properdin to activated platelets depends on the mode of stimulation, but is not directly proportional to the level of CD62P exposed on activated platelets.

FIGURE 2.

The binding of properdin to activated platelets is not proportional to CD62P levels on the platelet surface. Platelets were activated using thrombin (Thr) (0–1 IU/ml in (A) and (D); 1 IU/ml in (C) and (F)) or arachidonic acid (AA) (0–10 mM in (B) and (E); 1 mM in (C) and (F)). Non-activated (NA) or activated (Act) platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated in the presence of 25 µg/ml of P3 for 60 min at RT. (D)(F), Binding of properdin was assessed by FACS using an anti-properdin monoclonal antibody, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. (A)(C), Platelet activation was assessed by using PE/Cy5 labeled anti-CD62P monoclonal antibody. The arrows in (A) and (B) represent the dose of activator, used in (C) and (F), where maximal CD62P expression was achieved. An APC-labeled anti-CD42b monoclonal antibody was used to gate on platelets. The data are representative of two independent experiments shown as means and standard deviations. Statistical significance was assessed by determining the p-value using an unpaired t-test (p<0.001(***).

We also determined if native properdin can directly activate platelets. Incubating the resting platelets with properdin during the activation step does not result in an increase in expression of CD62P or gpIIbIIIa, or annexin V binding on the platelet surface (Fig. S2). Properdin cannot act as a co-stimulator either, because when the resting platelets were incubated with submaximum doses of thrombin or arachidonic acid in the presence of properdin, there was no increase in expression of CD62P or gpIIbIIIa, or annexin V binding beyond the level achieved using thrombin or arachidonic acid alone (not shown).

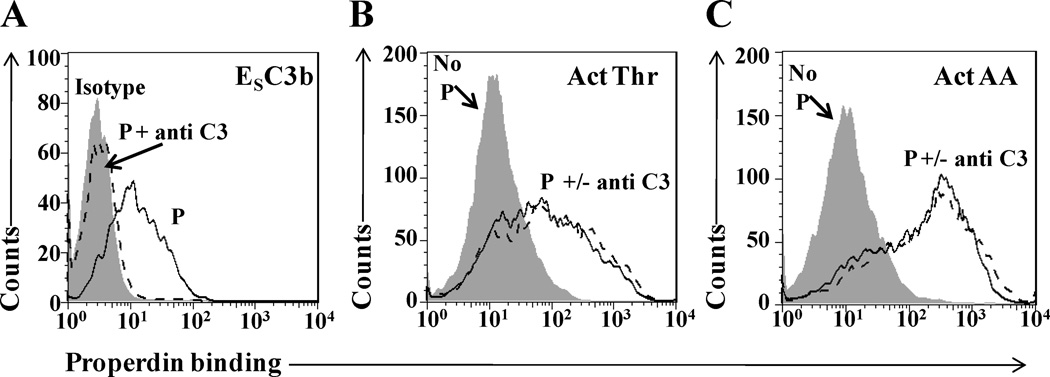

Properdin binding to activated platelets does not require previous C3 fragment deposition on the platelets

Complement C3 is present in platelets (9) and its spontaneously hydrolyzed form (C3(H2O)), as well as its C3b fragment, have been shown to bind to platelets (9, 11) and to properdin (49, 50). In order to determine if properdin was binding through C3 components on the platelets, we assessed whether the binding of properdin could be inhibited by polyclonal F(ab’)2 anti-C3 antibodies. Fig. 3A shows that 10 µg/ml of the antibody completely inhibited the binding of properdin to C3b-opsonized sheep erythrocytes. On the contrary, not even 10-fold more (100 µg/ml) of the same antibody was able to inhibit the binding of P2–4 to thrombin- or arachidonic acid-activated platelets (Fig. 3B–C). In addition, neither C3 components nor properdin were detected on the surface of washed thrombin- or arachidonic acid-activated platelets by flow cytometry (Fig. S3). These data indicate that the physiological forms of properdin bind selectively to activated platelets, independently from C3.

FIGURE 3.

The binding of properdin to platelets is not mediated by C3. (A) C3b coated sheep erythrocytes (ESC3b) (5×106 ESC3bs/100 µl) in GVB= were incubated with or without 10 µg/ml anti-C3 polyclonal antibody for 15 min at 4°C. Without washing, P2-P4 (10 µg/ml) were added to the cells and incubated further for 1 h at 4°C. Cells were washed and properdin binding was detected using an anti-properdin monoclonal antibody or an IgG1 isotype control, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. Thrombin activated (Thr-Act) (B) or arachidonic acid activated (AA-Act) (C) platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated with or without 100 µg/ml anti-C3 polyclonal antibody for 30 min at RT. Without washing, P2-P4 (10 µg/ml) were added to the cells and incubated further for 30 min at RT. Platelets incubated without anti-C3 and without P2-P4 were used as a negative control. Platelets were washed and binding of properdin was assessed using an anti-properdin monoclonal antibody, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. An APC-labeled anti-CD42b monoclonal antibody was used to gate on the platelet population.

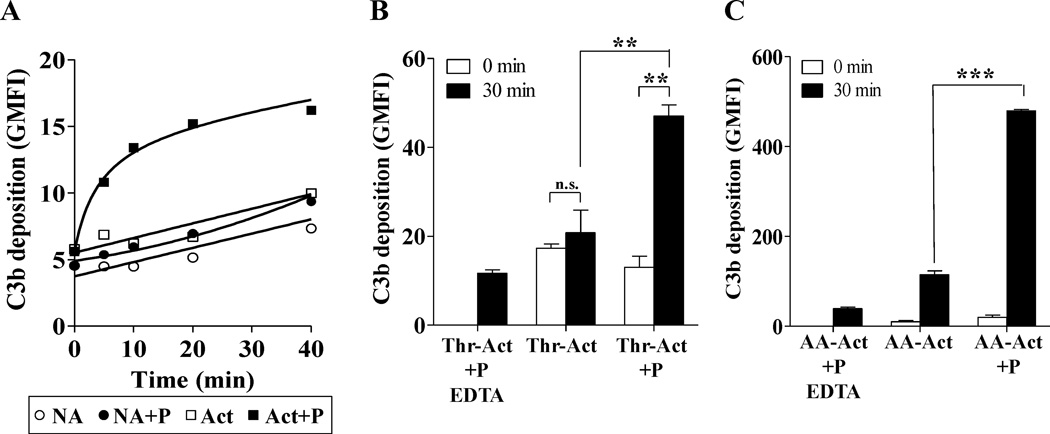

Properdin bound to stimulated platelets promotes complement activation on the platelet surface

In order to determine functional consequences of the interaction between properdin and stimulated platelets, we investigated whether physiological forms of properdin that are bound to activated platelets have the ability to promote complement activation. Washed, non-activated and thrombin- or arachidonic acid-activated platelets were incubated in the presence or absence of purified properdin (P3 forms). Platelets were then washed and exposed to properdin-depleted serum in order to study alternative pathway activation mediated only by properdin bound to the activated platelets. Figure 4A shows that rapid C3b deposition occurs on activated platelets pre-incubated with properdin in as early as 5 min compared to activated platelets alone, non-activated platelets or non-activated platelets pre-incubated with properdin. Maximum C3b deposition on properdin-bound activated platelets was observed after 20 min. Activated platelets with properdin on their surface induced ~2.2-fold increase in C3b deposition versus activated platelets alone, at 30 minutes (Fig. 4B). Only the group of thrombin-activated platelets with properdin on their surface induced significant C3b deposition when exposed to P-depleted serum for 30 minutes, versus zero minutes (Fig. 4B). Moreover, we observed that C3b deposition was ~10-fold higher on arachidonic acid (1mM)-stimulated platelets with properdin on their surface (Fig. 4C), when compared to the thrombin-activated platelets with surface-bound properdin (Fig. 4B; right bars). Arachidonic acid-activated platelets without properdin on their surface induced C3b deposition, although ~4-fold less than platelets with properdin on their surface (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that alternative pathway activation on stimulated platelets is greatly enhanced when properdin is bound to the platelet surface, even when complement regulatory functions on the platelets are normal.

FIGURE 4.

Properdin promotes complement activation on the surface of activated platelets. Non-Activated (NA), thrombin activated (Thr-Act) or arachidonic acid activated (AA-Act) platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated in the presence or absence of P3 or P2–4 (25 µg/ml) for 60 min at RT. Platelets were then washed and incubated with 60% properdin-depleted serum in presence of Mg-EGTA at 37°C for various time points in (A) or 30 min in (B) and (C). Deposition of C3b on the surface of platelets was assessed using a PE-labeled anti-C3 monoclonal antibody in (A) or unlabelled anti-C3/C3b monoclonal antibody followed by AF488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG in (B) and (C). An APC-labeled anti-CD42b monoclonal antibody was used to gate on the platelet population. As controls, platelets (in the presence or absence of properdin) were incubated with 60% properdin-depleted serum in EDTA (10mM). In (A), the EDTA controls gave an average GMFI of 5.3±0.69 at 40 min (not shown in graph). The graphs show one representative experiment of three independent experiments. Each bar in (B) and (C) represents the mean and standard deviation of triplicate observations. Statistical significance was assessed by determining the p-value using an unpaired t-test (p<0.01(**); p<0.001 (***)).

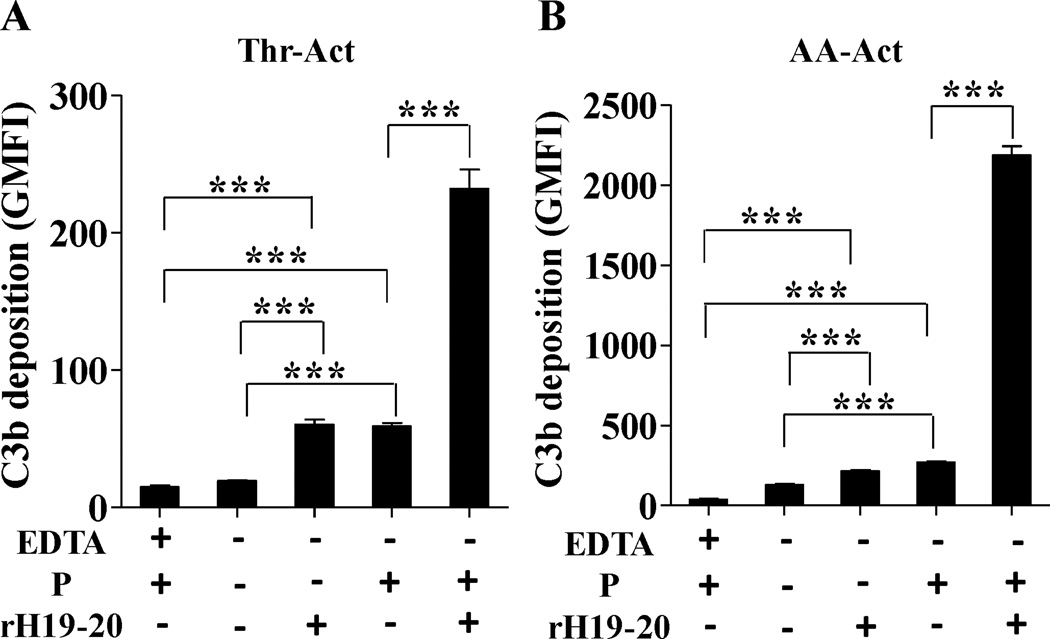

Inhibition of factor H-mediated cell surface protection enhances properdin-mediated complement activation on platelets

In order to determine if impairing complement regulation on platelets enhances properdin-mediated complement activation, we used a competitive inhibitor of factor H cell surface complement regulation known as rH19–20 (17, 42–45). This inhibitor is a recombinant protein consisting of domains 19–20 of factor H that competes with full-length factor H for binding to cell surface C3b and polyanions, inhibiting the ability of factor H to protect cell surfaces, without affecting fluid phase complement regulation (42). Factor H can bind activated platelets (51, 52). Mutations in the C-terminus of factor H impair the efficient binding of factor H to cell surfaces and have been associated with deposition of complement on the platelet surface in patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, which can result in thrombosis and thrombocytopenia (18). Thus, we examined the effect of inhibiting factor H regulation on the platelet surface during properdin-mediated complement activation on platelets. The data in Figure 5 indicate that inhibiting factor H complement regulation using rH19–20 on thrombin- or arachidonic acid-activated platelets with properdin increases C3b deposition by ~4-fold (thrombin-activated; Fig. 5A) and ~8-fold (arachidonic acid-activated; Fig. 5B) when compared to activated platelets with properdin, but without rH19–20. Inhibiting factor H complement regulation in the absence of properdin induces significant C3b deposition as compared to the EDTA control. This increase is similar to the C3b deposition that occurs when the platelets have properdin on their surface and factor H regulation has not been inhibited.

FIGURE 5.

Properdin-mediated complement activation is exacerbated when cell surface protection by factor H is inhibited. Thrombin-activated (Thr-Act; (A)) or arachidonic acid-activated (AA-Act; (B)) (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated in the presence or absence of P2-P4 (25 µg/ml) for 60 min at RT. Platelets were then washed and incubated with 60% properdin-depleted serum in presence of Mg-EGTA with or without rH19–20 (25µM) at 37°C for 30 min. Deposition of C3b on the surface of platelets was assessed using an unlabelled anti-C3/C3b monoclonal antibody followed by AF488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. An APC-labeled anti-CD42b monoclonal antibody was used to gate on the platelet population. As controls, platelets (in the presence of properdin) were incubated with 60% properdin depleted serum in EDTA (10mM). The graphs show one representative experiment of two independent experiments. Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of triplicate observations. Statistical significance was assessed by determining the p-value using an unpaired t-test (p<0.001 (***)).

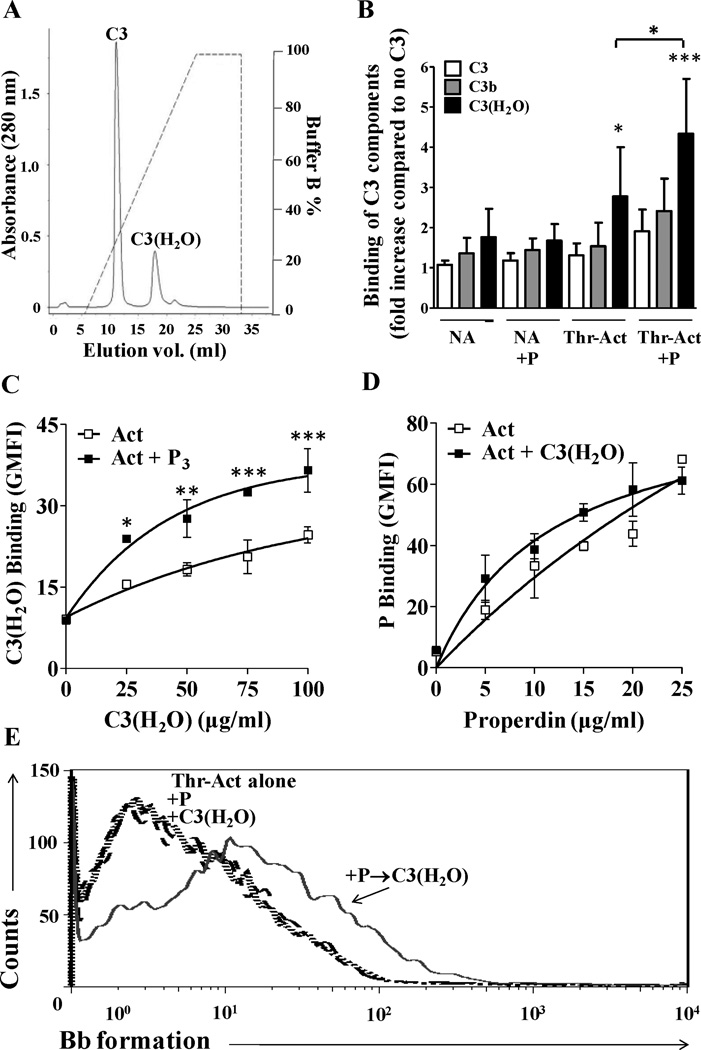

Properdin recruits C3 components to the surface of activated platelets leading to functional C3 convertase formation

We next sought to define the molecular mechanisms involved in properdin-mediated complement activation on stimulated platelets. Properdin can bind to C3b (25) and C3(H2O) (49, 50), which are structurally similar. We therefore analyzed the ability of the properdin that is bound to the activated platelet to recruit C3b and C3(H2O) to the platelet surface, as a potential first step in convertase formation (Figs. 6 and 7). It has been proposed that C3b binds directly to activated platelets via CD62P (9). Nevertheless, Hamad et al., by using antibodies against a neo epitope found on C3(H2O), detected binding of C3(H2O), but not of C3b or non-activated C3, to activated platelets (11). Figure 6A shows the separation of C3(H2O) from C3 by ion-exchange chromatography. The data in Figure 6B, using thrombin-activated platelets, confirm that C3 and C3b do not significantly bind directly to resting or thrombin-activated platelets, and that C3 and C3b do not bind even when properdin is present on the platelet surface. On the other hand, C3(H2O) binds significantly to activated platelets without (p<0.05) and with (p<0.001) properdin on their surface (Fig. 6B). Moreover, properdin that is bound directly to activated platelets recruits ~1.5-fold more C3(H2O) to the platelet surface when compared to activated platelets alone (Fig. 6C). On the contrary, the C3(H2O) that is bound directly to activated platelets (Fig. 6B) is not able to recruit more properdin than the activated platelets without C3(H2O) (Fig. 6D).

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of binding of C3, C3b and C3(H2O) to thrombin-activated platelets with or without properdin on their surface, and the ability to form a functional convertase. (A) C3 was separated from C3(H2O) by cation exchange chromatography as described in the Methods section. (B) Non activated (NA) or thrombin-activated (Thr-Act) platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated in the presence or absence of P3 (25µg/ml) for 30 min at RT, washed and then incubated without or with C3, C3(H2O) or C3b (100µg/ml) at RT for 1 h. Binding of C3 forms was assessed by FACS using an anti-C3/C3b monoclonal antibody followed by AF488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. APC-labeled anti CD42b antibody was used to gate on platelets. Binding of C3, C3b, and C3(H2O) to each group of platelets (NA, NA+P, Thr-Act, Thr-Act+P) was normalized to the GMFI of each respective group incubated without any C3 components. The results represent the mean and SDs of seven independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out comparing all columns of NA conditions to the NA + C3 group, and all columns of Act conditions to the Act + C3 group by one way analysis of variance-Dunnett’s Multiple comparison test. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: p<0.05(*), p<0.001(***). An unpaired student’s t test was used to evaluate the statistical significance between the binding of C3(H2O) to the Act versus the Act-P group (p<0.05(*)). (C) Properdin recruits C3(H2O) to the surface of activated platelets. Thrombin-activated (Act) platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated in the presence or absence of P3 (25 µg/ml) for 30 min at RT. Platelets were then washed and incubated with increasing doses of C3(H2O) (0–100 µg/ml) at RT for 1 h. Binding of C3(H2O) was assessed by FACS as described in (B). (D) C3(H2O) does not recruit properdin to the surface of activated platelets. Thrombin activated (Act) platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated in the presence or absence C3(H2O) (100 µg/ml) at RT for 60 min. Platelets were then washed and incubated with increasing doses of properdin (0–25 µg/ml) at RT for 60 min. Properdin binding was assessed using an anti-properdin monoclonal antibody followed by AF488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. APC-labeled anti CD42b antibody was used to gate on the platelet population. Each graph (C) and (D) is representative of two independent experiments shown as means and SDs. Statistical analysis (p<0.05(*), p<0.01(**), p<0.001(***)) was performed by using two way analysis of variance-Bonferroni’s posttest. All data without a p-value were non-significant. (E) Properdin bound to activated platelets promotes the formation of C3(H2O),Bb convertase on the surface of platelets. Thrombin-activated (Thr-Act) platelets were incubated in the presence of P3 (25 µg/ml) or C3(H2O) (100 µg/ml), or sequentially with both (P3→C3(H2O)) or with neither for 60 min each at RT in Tyrode’s buffer. Platelets were then washed and incubated in the presence of factor B (80 µg/ml) and factor D (2 µg/ml) for 30 min at RT in Tyrode’s buffer. Formation of Bb on activated platelets was assessed by using an anti-Bb neo-epitope monoclonal antibody, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488 F(ab’)2 goat conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. APC-labeled anti-CD42b antibody was used to gate on platelets. One representative experiment of three separately performed experiments are shown.

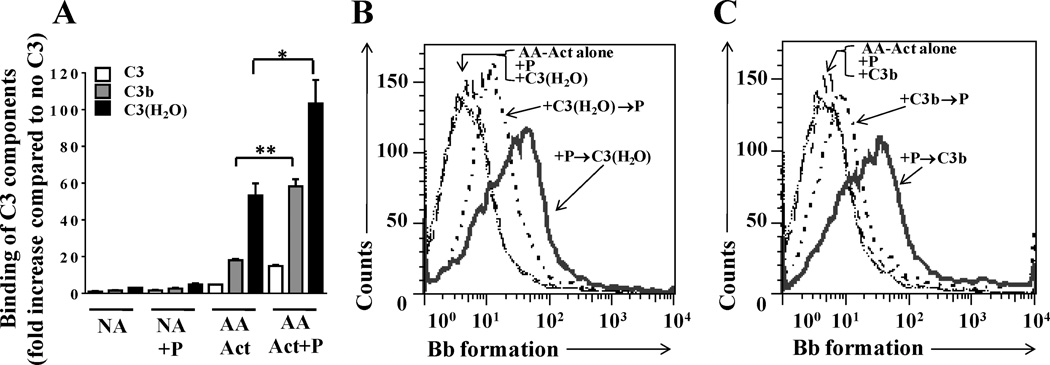

FIGURE 7.

Analysis of binding of C3, C3b and C3(H2O) to arachidonic acid-activated platelets with or without properdin on their surface, and the ability to form a functional convertase. (A) Non activated (NA) or arachidonic acid-activated (AA-Act) platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated in the presence or absence of P2–4 (25µg/ml) for 30 min at RT, washed and then incubated with C3, C3(H2O) or C3b (50µg/ml) at RT for 1 h. Binding of C3 forms was assessed by FACS using an anti-C3/C3b monoclonal antibody followed by AF488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. APC-labeled anti CD42b antibody was used to gate on platelets. Binding of C3, C3b, and C3(H2O) to platelets was normalized to the GMFI observed for each group incubated without any C3 components. The results show one representative experiment of two independent experiments. An unpaired student’s t test was used to evaluate the statistical significance between the binding of C3(H2O) to the Act versus the Act-P group (p<0.05(*), p<0.01 (**), unpaired Student t test). (B) Arachidonic acid-activated platelets were incubated in the presence of P2-P4 (25 µg/ml), C3(H2O) (100 µg/ml) or sequentially with both (P→C3(H2O) or C3(H2O)→P) or neither for 60 min each at RT in Tyrode’s buffer. (C) Arachidonic acid-activated platelets were incubated in the presence of P2-P4 (25 µg/ml), C3b (100 µg/ml) or sequentially with both (P→C3b or C3b→P) or neither for 60 min each at RT in Tyrode’s buffer. Platelets were then washed and incubated in the presence of factor B (80 µg/ml) and factor D (2 µg/ml) for 30 min at RT in Tyrode’s buffer. Formation of Bb on activated platelets was assessed by using an anti-Bb neo-epitope monoclonal antibody, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488 F(ab’)2 goat conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. APC-labeled anti-CD42b antibody was used to gate on platelets. One representative experiment of two separately performed experiments are shown.

In order to determine whether the platelet-bound properdin and C3(H2O) (recruited by properdin) can interact with factors B and D to generate a C3 convertase, thrombin-activated platelets were incubated with either (a) buffer, (b) properdin, (c) C3(H2O), or (d) properdin followed by washing and then C3(H2O). A group with C3(H2O) first followed by properdin was not included, as C3(H2O) does not recruit properdin to the platelet surface. After washing the cells, factors B and D were added to the groups of platelets mentioned above and the formation of Bb, due to proteolytic cleavage by factor D, was assessed by flow cytometry using an anti-Bb neoepitope antibody (Fig. 6E). Although platelets bind C3(H2O) directly (Fig. 6B), formation of Bb was detected only on the surface of thrombin-activated platelets where C3(H2O) was additionally recruited to the surface by properdin (Fig. 6E).

When analyzing arachidonic acid-activated platelets (Fig. 7), both C3(H2O) and C3b bind significantly to activated platelets without and with properdin on their surface (Fig. 7A). Properdin bound to activated platelets recruits ~3-fold more C3b (p<0.01) and ~2-fold more C3(H2O) (p<0.05) to the platelet surface when compared to activated platelets alone. We next assessed the ability of platelet-bound properdin, C3b, and C3(H2O) to generate C3 convertases. Formation of Bb was detected on the surface of arachidonic acid-activated platelets where C3(H2O) (Fig. 7B, solid line) or C3b (Fig. 7C, solid line) was recruited to the surface by properdin. When platelets first received C3(H2O) or C3b, convertase formation occurred only after properdin had been recruited (Fig. 7B–C, dotted lines). Altogether, these data indicate that on thrombin-activated platelets, only the recruitment of C3(H2O) by properdin leads to de novo formation of novel cell-bound [C3(H2O),Bb] convertases, while in the case of arachidonic acid-activated platelets, recruitment of both C3(H2O) and C3b by properdin leads to convertase formation. Moreover, C3(H2O) that is bound directly to arachidonic acid-activated platelets can form, albeit to a lesser extent, novel convertases that require the recruitment of properdin for convertase stabilization, facilitating convertase detection (Fig. 7B, dotted line).

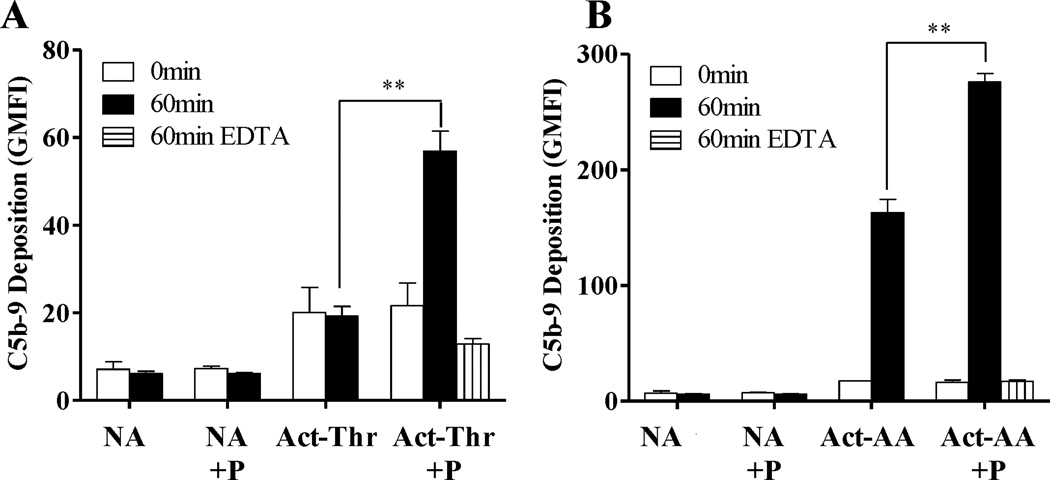

Properdin bound to activated platelets leads to C9 deposition

Deposition of C3b on host cell surfaces may not necessarily cause complement to progress to its terminal stage (formation of membrane attack complex; C5b-9; MAC) as host cell surfaces are protected by membrane-bound and fluid-phase complement regulatory proteins. Platelets have surface-bound CD55, CD46, CD35 and CD59 (53, 54), and are able to bind factor H (51). Thus, we investigated whether properdin-mediated complement activation on the surface of platelets leads to formation of the MAC (Fig. 8) in spite of complement regulation. Washed non-activated, thrombin-activated or arachidonic acid-activated platelets were incubated in the presence or absence of properdin and exposed to properdin-depleted serum for 60 min. C5b-9 deposition on the platelets was measured using an antibody specific for a neo epitope on C9 that is exposed only when C9 is incorporated into the MAC. Only the thrombin-activated platelets that had been pre-incubated with properdin showed an increase in C5b-9 deposition (~2.9-fold increase at 60 min) as compared to activated platelets alone, non-activated platelets or non-activated platelets pre-incubated with properdin (Fig. 8A). In the case of arachidonic acid-activated platelets, MAC deposition was observed on activated platelets without properdin on their surface, and a ~1.6-fold increase was observed on platelets with properdin on their surface (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Properdin promotes formation of C5b-9 complexes on the surface of activated platelets. Non-Activated (NA), thrombin-activated (Act-Thr) (A) or arachidonic acid-activated (Act-AA) (B) platelets (2×106 platelets/100 µl) were incubated in the presence or absence of P2–4 or P3 (25 µg/ml) for 60 min at RT. Platelets were then washed and incubated with 60% properdin-depleted serum in the presence of Mg-EGTA at 37°C for 0 or 60 min (or with EDTA at 37°C for 60 minutes only as a control). Deposition of C5b-9 complexes was assessed using an anti-C5b-9 neo-epitope monoclonal antibody followed by AF488 conjugated anti-mouse IgG. An APC-labeled anti-CD42b monoclonal antibody was used to gate on platelets. The results are representative of two separate experiments shown as means and SDs of triplicate observations. Statistical significance was assessed by determining the p-value using an unpaired t-test (p<0.005 (**)).

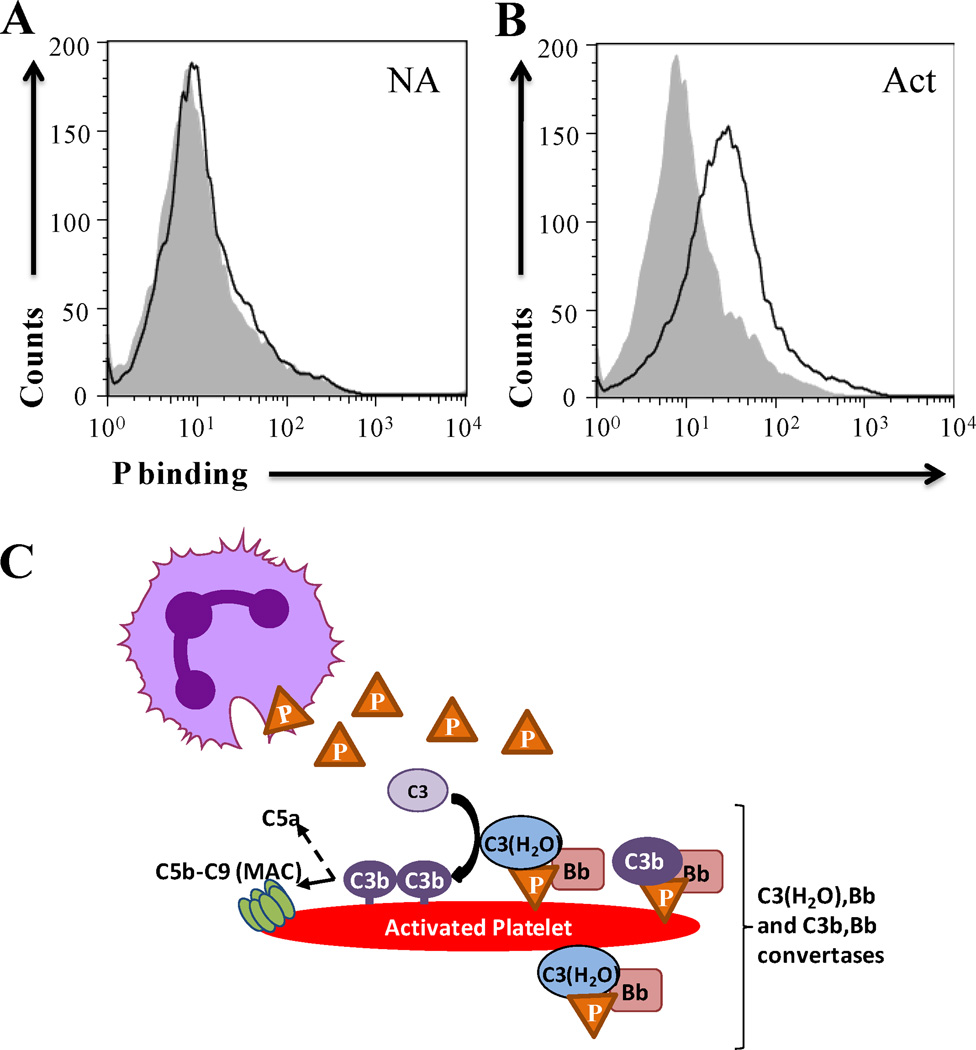

Properdin produced by activated neutrophils binds to activated platelets

It has been previously shown that serum inhibits binding of properdin to surfaces (34, 35). In agreement with this, properdin binding to platelets was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by NHS (Fig. S4). This suggests that properdin binding to activated platelets may occur only when properdin is readily available to activated platelets in the microenvironment and that properdin-mediated complement activation is tightly controlled.

Neutrophils release properdin upon activation by various inflammatory stimuli such as PMA, fMLP, C5a and TNF-α (29), and unfractionated properdin also interacts directly with platelets (platelet/leukocyte aggregates) (55), which may increase the local concentration of properdin in a pro-inflammatory microenvironment. In order to determine whether properdin derived from the activated neutrophil supernatants binds to platelets, supernatants from PMA-activated neutrophils were incubated with non-activated and thrombin-activated platelets (that bind significantly less pure properdin than arachidonic-acid-activated platelets). The activated platelets themselves do not have properdin on their surface (Fig. S3). As shown in Figure 9A–B, the properdin in the neutrophil supernatant bound only to activated platelets. C3 from activated neutrophil supernatants did not bind to the platelets (not shown), indicating that the binding of neutrophil-derived properdin to the platelets occurred independently from C3.

FIGURE 9.

Properdin released by activated neutrophils binds to activated platelets. (A) Non-activated (NA) or (B) thrombin-activated (Act) platelets were incubated with supernatant from PMA-activated neutrophils for 60 min at RT in Tyrode’s buffer with 10 mM EDTA. Platelets were washed and binding of properdin was assessed by FACS using anti-properdin antibody (dark line), followed by an Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. IgG1 monoclonal antibody was used as isotype control (grey filled). APC-labeled anti-CD42b antibody was used to gate on platelets. One representative experiment of two separately performed experiments is shown. (C) Model: Properdin-mediated complement activation on activated platelets. Properdin (orange triangles) released by PMN binds to activated platelets and can recruit C3(H2O) (thrombin-activated platelets) or both C3(H2O) and C3b (arachidonic acid-activated platelets) to stimulated platelets, allowing the formation of a novel cell bound C3(H2O),Bb or a C3b,Bb convertase. C3(H2O) can also bind to stimulated platelets and in the presence of properdin can promote C3(H2O),Bb convertase formation. These events can then lead to alternative pathway complement activation (as shown by C3b and MAC deposition) on the platelet surface.

Discussion

Our studies reveal that the physiological forms of properdin bind to stimulated platelets, but not to resting platelets, in a manner that is not proportional to P-selectin exposure, leading to the formation of a novel C3 convertase (P-C3(H2O),Bb) on its surface, and allowing the activation of the alternative pathway of the complement system. In addition, C3(H2O) can also initiate activation of complement, as long as properdin is present to stabilize the convertases. The data also show that properdin released by neutrophils binds activated platelets, and collectively suggest that properdin is essential for alternative pathway activation to proceed on activated platelets.

Our results show that physiological forms of properdin bind to platelets that have been activated by strong agonists (Fig. 1E), but not to non-activated platelets (Fig. 1 A–C), in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 1D). Thrombin activates platelets via PAR receptors by pathways dependent on phospholipase C and/or phospholipase A2, the latter of which includes the arachidonic acid transformation pathway. The arachidonic acid pathway bypasses the need for agonist receptors and activates platelets via the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway by using thromboxane synthase to produce platelet agonist thromboxane A2 (56). Aside from platelets, neighboring activated cells such as leukocytes and endothelial cells also express COX isoenzymes (57), which could further contribute to platelet activation. It has been previously shown that inhibitors of COX lead to the inhibition of complement-enhanced platelet aggregation and release of serotonin (58–63). Platelets activated by weak agonists such as ADP and epinephrine support less complement activation than platelets activated by thrombin or arachidonic acid (8). The capacity of platelets to activate complement on their surface when exposed to plasma or serum is proportional to the extent of platelet activation (8) and alternative pathway activation has been shown to occur due to the binding of C3b to activated platelets via P-selectin (CD62P) (9). In this study, our data show that arachidonic acid-stimulated platelets induced significantly lower overall exposure of P-selectin compared with thrombin-activated platelets (Figs. 2A–C). Nevertheless, properdin binding was ~3–4 fold higher (Figs. 2D–F) and C3b deposition was ~10-fold higher (Fig. 4B,C) on the arachidonic acid-stimulated platelets, when compared to thrombin-activated platelets at maximal platelet P-selectin expression for both agonists. Our data show that, unlike the C3b/P-selectin mechanism for alternative pathway complement activation described by del Conde et al. (9), properdin binding to activated platelets and C3b deposition are not proportional to the expression of CD62P. Thus, properdin binding may depend on agonist-specific varying exposure of cell surface marker(s) on the platelets. In agreement with this notion, proteomic expression on platelets has been shown to vary depending on the platelet agonist used (64).

Importantly, we show that properdin does not rely on C3 fragment deposition on the platelet for binding (Fig. 3). Properdin is a highly positively charged protein (isoelectricpoint >9.5) that can interact with certain surfaces directly by recognizing glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains of surface proteoglycans (35, 65). Candidate sulfated GAGs shown to interact with properdin include heparin (66), heparan sulfate (35, 65), dextran sulfate (67), fucoidan (67), and chondroitin sulfate (35). Interestingly, chondroitin sulfate A, which is released by platelets and found on the platelet surface upon activation (68, 69), enhances the binding of properdin to the activated platelets (not shown). Other ligands for properdin on cells include DNA on late apoptotic and necrotic cells (37), and bacterial LPS and lipooligosaccharide (70). Thus, all cell surface molecules (identified to date), shown to interact directly with properdin on cells, are negatively charged. Efforts to define the GAGs involved in properdin binding to the platelet surface are currently under way in our laboratory.

Recently, Hamad et al. (11) showed, using specific antibodies, that the C3 that binds to platelets consists mainly of C3(H2O), with no C3b present. Because C3(H2O) is generated in the fluid phase of blood by the spontaneous hydrolysis of the thioester bond in C3, the C3(H2O) that was bound to the platelet was non-proteolitically activated (11). In agreement with these results, our data with thrombin-activated platelets show that purified C3(H2O) indeed binds to activated platelets while C3b binding cannot be detected (Fig. 6B). Platelet-bound C3(H2O) (Fig. 6) does not lead to the formation of a C3 convertase on the thrombin-activated platelet surface when exposed to factors B and D (Fig. 6E). On the other hand, properdin, by recruiting C3(H2O) (Fig. 6C) to the surface of activated platelets, allows the formation of a novel cell bound C3(H2O),Bb convertase in the presence of factors B and D (Fig. 6E), which can lead to the activation of the alternative pathway as measured by C3b and C9 deposition (Figs. 4 and 8). It is likely that platelet-bound properdin, aside from acting as an initiating point for alternative pathway activation on the platelets, is also stabilizing the newly formed convertase, facilitating detection of the convertase in our experimental system by making it more resistant to decay versus the platelets without properdin on their surface.

Interestingly, the results with arachidonic-acid activated platelets (Fig. 7), which were not assessed in the previous study (11), indicate that activated platelets bind detectable levels of C3b in addition to C3(H2O) (Fig. 7A). Aside from the C3(H2O) that is available due to C3 tickover (reviewed in (21)), Nilsson and Nilsson-Ekdahl have hypothesized that the rate of hydrolysis of C3 to C3(H2O) may be accelerated by the interaction of C3 with certain biological surfaces, such as platelets (71) and that this C3(H2O) may serve as an initiating molecule of the alternative pathway (71). As mentioned, C3(H2O) no longer has a reactive thioester for interacting covalently with cell surfaces, and is normally found forming part of fluid phase C3 convertases for initiating the alternative pathway. However, Fig. 7B shows that C3(H2O) bound to arachidonic acid-activated platelets can in fact lead to the formation of a novel cell-bound convertase, which can only be detected if properdin is present to stabilize the convertase (Fig. 7C, dotted line). Although we did not detect direct binding of whole C3 to thrombin-activated platelets, and only minimal binding of C3 to arachidonic acid-activated platelets, increased availability of C3(H2O) may be triggered by contact activation of C3 on gas bubbles, such as those that occur in cardiopulmonary devices and in decompression sickness (reviewed in (71)), potentially contributing to complement activation on platelets.

It is not known why C3(H2O) binds more than C3b to the activated platelets and to properdin on the platelets (Figs. 6–7), despite being components that are structurally and functionally similar (20). CR2 (CD21; C3d/iC3b receptor) may be a receptor for C3(H2O) on B lymphocytes (50), and CR2 has been identified on the surface of platelets (72). It is also possible that the C3a region that is present in C3(H2O), but not in C3b, may contain a site important for interacting with activated platelets. The interacting region between C3 (1402–1435aa) and properdin (TSR-5) has been previously determined (73). To our knowledge, our data indicate for the first time that additional recruitment of C3(H2O) by properdin, on activated platelets, leads to de novo formation of cell bound [C3(H2O),Bb] convertases. These results suggest that properdin on the platelet surface may act as a second contact point for C3(H2O) increasing its avidity for activated platelets and allowing C3(H2O) to form a novel functional C3 convertase [C3(H2O),Bb].

Our data shows that alternative pathway activation proceeds when properdin is bound to the surface of activated platelets, as measured by C3b (Fig. 4) and C5b-9 deposition (Fig. 8) after exposing the platelets to properdin-depleted serum. NHS was used in separate experiments as a serum control that has undergone less post-extraction processing than the depleted sera and the results were similar (not shown). This complement activation occurs even when complement regulation on the platelets is normal (i.e. normal membrane-bound and fluid phase complement regulatory proteins). However, C3b deposition is significantly enhanced when cell surface protection by factor H is blocked, especially on activated platelets that have properdin on their surface (Fig. 5). Clinical data suggests that enhanced platelet-associated complement activation correlates with increased thrombotic events in patients with aHUS (18, 74) due to mutations in the C-terminus of factor H that impair cell surface protection (75), and properdin-mediated complement activation may contribute to these phenomena.

Properdin derived from PMN cells binds to activated platelets (Fig. 9A–B). Under physiological inflammatory conditions and normal complement regulation, properdin may direct low level complement activation on activated platelets, and contribute to opsonizing spent platelets for removal. Serum inhibits the ability of properdin to bind to activated platelets in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S4). It is possible that properdin that is freshly secreted by different cell types (27, 29, 32) and does not quickly encounter a nearby platelet surface to bind, will eventually lose its ability to bind to surfaces directly once it comes in contact with serum. This regulation would prevent unwanted properdin-mediated complement damage at more distant/bystander cell surfaces while keeping the conventional function of stabilizing the C3 and C5 convertases of the alternative pathway intact. As mentioned, properdin binds DNA and sulfated glucoconjugates. Thus, fluid phase forms of DNA (76) or glycoproteins could potentially serve as regulators of properdin/surface interactions once properdin has left the microenvironment of the cells producing it (i.e. neutrophils).

Complement also plays a role in tissue damage in many inflammatory diseases that are associated with increased platelet activation and coagulopathies that are not directly associated with defects in complement regulation (i.e. cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, sepsis, among others) (13). Thus, it is possible that in vascular injury, the local inflammatory leukocytes may readily produce properdin (27–30, 32, 77). This properdin would be available to platelets at high concentrations in the local microenvironment as they become activated by the damaged endothelium and interact with leukocytes (forming platelet/leukocyte aggregates (55)), potentially contributing to complement-mediated disease pathogenesis. In agreement with this notion, Ruef et al. (78) showed that pure, unfractionated properdin (with non-physiological polymers), when added to whole blood, increases the formation of platelet/leukocyte aggregates. In addition, properdin-mediated complement activation (by inducing formation of MAC, and release of C3a and C5a) may stimulate degranulation and activation of other resting platelets (14, 15). Moreover, the properdin-induced complement activation on platelets significantly increases when cell surface protection by factor H is inhibited using a competitive inhibitor (Fig. 5). Thus, this properdin-mediated mechanism may be exacerbated in diseases where complement regulation is compromised (i.e. PNH, aHUS) (18, 19).

The data collectively indicate a new mechanism of alternative pathway activation on stimulated platelets that is not proportional to the expression of CD62P, is initiated by properdin, and requires the recruitment of C3(H2O) or C3b for the formation of a novel initiating cell-bound C3 convertase [P-C3(H2O),Bb] or of [P-C3b,Bb] (Fig. 9C; Model). C3(H2O) can also initiate convertase formation, but requires properdin for stabilization. These mechanisms may depend on the availability of properdin in the local pro-inflammatory microenvironment and contribute to complement activation in physiological inflammation as well as to complement-mediated tissue damage in inflammatory diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Laci Bloomfield for excellent technical support and Dr. Michael Pangburn and Dr. Ellinor Peerschke for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- MAC

membrane attack complex

- PNH

paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- aHUS

atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome

- P2

dimeric forms of properdin

- P3

trimeric forms of properdin

- P4

tetrameric forms of properdin

- Pn

non-physiological aggregated forms of properdin

- Tyrode/PGE/Hep buffer

Tyrode’s buffer containing Prostaglandin E1 and Heparin

- GVB

gelatin veronal buffer without calcium and magnesium

- NHS

normal human serum

- RT

room temperature

- ESC3b

C3b–coated sheep erythrocytes

- PMN

polymorphonuclear cell

- rH19–20

recombinant protein consisting of domains 19–20 of factor H

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- NA

Non-activated

- Act

Activated

- Thr

Thrombin

- AA

Arachidonic acid

- GMFI

geomean fluorescence intensity

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interests

This work has been supported by National Institutes of Health 1P30HL101317-01, American Heart Association 12GRNT10240003 and University of Toledo DeArce-Koch Memorial Endowment Fund (V.P.F.).

References

- 1.Semple JW, Freedman J. Platelets and innate immunity. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67:499–511. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brass L. In the shadow of the thrombus. Nat. Med. 2009;15:607–608. doi: 10.1038/nm0609-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quinn M. Platelet Physiology. In: Quinn M, Fitzgerald D, editors. Platelet Function: Assesment, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2010. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trip MD, Cats VM, van Capelle FJ, Vreeken J. Platelet hyperreactivity and prognosis in survivors of myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990;322:1549–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005313222201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Zanten GH, de GS, Slootweg PJ, Heijnen HF, Connolly TM, de Groot PG, Sixma JJ. Increased platelet deposition on atherosclerotic coronary arteries. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;93:615–632. doi: 10.1172/JCI117014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furman MI, Benoit SE, Barnard MR, Valeri CR, Borbone ML, Becker RC, Hechtman HB, Michelson AD. Increased platelet reactivity and circulating monocyte-platelet aggregates in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998;31:352–358. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peerschke EI, Yin W, Grigg SE, Ghebrehiwet B. Blood platelets activate the classical pathway of human complement. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4:2035–2042. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peerschke EI, Yin W, Ghebrehiwet B. Complement activation on platelets: implications for vascular inflammation and thrombosis. Mol. Immunol. 2010;47:2170–2175. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Conde I, Cruz MA, Zhang H, Lopez JA, Afshar-Kharghan V. Platelet activation leads to activation and propagation of the complement system. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:871–879. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamad OA, Ekdahl KN, Nilsson PH, Andersson J, Magotti P, Lambris JD, Nilsson B. Complement activation triggered by chondroitin sulfate released by thrombin receptor-activated platelets. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2008;6:1413–1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamad OA, Nilsson PH, Wouters D, Lambris JD, Ekdahl KN, Nilsson B. Complement component C3 binds to activated normal platelets without preceding proteolytic activation and promotes binding to complement receptor 1. J. Immunol. 2010;184:2686–2692. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peerschke EI, Yin W, Alpert DR, Roubey RA, Salmon JE, Ghebrehiwet B. Serum complement activation on heterologous platelets is associated with arterial thrombosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid antibodies. Lupus. 2009;18:530–538. doi: 10.1177/0961203308099974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:785–797. doi: 10.1038/ni.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiedmer T, Esmon CT, Sims PJ. Complement proteins C5b-9 stimulate procoagulant activity through platelet prothrombinase. Blood. 1986;68:875–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polley MJ, Nachman RL. Human platelet activation by C3a and C3a des-arg. J. Exp. Med. 1983;158:603–615. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.2.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerr H, Richards A. Complement-mediated injury and protection of endothelium: lessons from atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Immunobiology. 2012;217:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferreira VP, Pangburn MK. Factor H mediated cell surface protection from complement is critical for the survival of PNH erythrocytes. Blood. 2007;110:2190–2192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stahl AL, Vaziri-Sani F, Heinen S, Kristoffersson AC, Gydell KH, Raafat R, Gutierrez A, Beringer O, Zipfel PF, Karpman D. Factor H dysfunction in patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome contributes to complement deposition on platelets and their activation. Blood. 2008;111:5307–5315. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devine DV, Siegel RS, Rosse WF. Interactions of the platelets in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria with complement. Relationship to defects in the regulation of complement and to platelet survival in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 1987;79:131–137. doi: 10.1172/JCI112773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pangburn MK, Schreiber RD, Muller-Eberhard HJ. Formation of the initial C3 convertase of the alternative complement pathway. Acquisition of C3b-like activities by spontaneous hydrolysis of the putative thioester. J. Exp. Med. 1981;154:856–867. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.3.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lachmann PJ. The amplification loop of the complement pathways. Adv. Immunol. 2009;104:115–149. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)04004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pangburn MK, Morrison DC, Schreiber RD, Muller-Eberhard HJ. Activation of the alternative complement pathway: recognition of surface structures on activators by bound C3b. J. Immunol. 1980;124:977–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahu A, Kozel TR, Pangburn MK. Specificity of the thioester-containing reactive site of human C3 and its significance to complement activation. Biochem. J. 1994;302:429–436. doi: 10.1042/bj3020429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller-Eberhard HJ, Gotze O. C3 proactivator convertase and its mode of action. J. Exp. Med. 1972;135:1003–1008. doi: 10.1084/jem.135.4.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fearon DT, Austen KF. Properdin: Binding to C3b and stabilization of the C3b-dependent C3 convertase. J. Exp. Med. 1975;142:856–863. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.4.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nolan KF, Reid KB. Properdin. Methods Enzymol. 1993;223:35–46. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)23036-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whaley K. Biosynthesis of the complement components and the regulatory proteins of the alternative complement pathway by human peripheral blood monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1980;151:501–516. doi: 10.1084/jem.151.3.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwaeble W, Dippold WG, Schafer MK, Pohla H, Jonas D, Luttig B, Weihe E, Huemer HP, Dierich MP, Reid KB. Properdin, a positive regulator of complement activation, is expressed in human T cell lines and peripheral blood T cells. J. Immunol. 1993;151:2521–2528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wirthmueller U, Dewald B, Thelen M, Schafer MK, Stover C, Whaley K, North J, Eggleton P, Reid KB, Schwaeble WJ. Properdin, a positive regulator of complement activation, is released from secondary granules of stimulated peripheral blood neutrophils. J. Immunol. 1997;158:4444–4451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwaeble WJ, Reid KB. Does properdin crosslink the cellular and the humoral immune response? Immunol. Today. 1999;20:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01376-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cortes C, Ohtola JA, Saggu G, Ferreira VP. Local release of properdin in the cellular microenvironment: role in pattern recognition and amplification of the alternative pathway of complement. Front Immunol. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00412. article 412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bongrazio M, Pries AR, Zakrzewicz A. The endothelium as physiological source of properdin: role of wall shear stress. Mol. Immunol. 2003;39:669–675. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pangburn MK. Analysis of the natural polymeric forms of human properdin and their functions in complement activation. J. Immunol. 1989;142:202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferreira VP, Cortes C, Pangburn MK. Native polymeric forms of properdin selectively bind to targets and promote activation of the alternative pathway of complement. Immunobiology. 2010;215:932–940. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kemper C, Mitchell LM, Zhang L, Hourcade DE. The complement protein properdin binds apoptotic T cells and promotes complement activation and phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:9023–9028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801015105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaarkeuken H, Siezenga MA, Zuidwijk K, van KC, Rabelink TJ, Daha MR, Berger SP. Complement activation by tubular cells is mediated by properdin binding. Am. J. Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1397–F1403. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90313.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu W, Berger SP, Trouw LA, de Boer HC, Schlagwein N, Mutsaers C, Daha MR, van KC. Properdin binds to late apoptotic and necrotic cells independently of c3b and regulates alternative pathway complement activation. J. Immunol. 2008;180:7613–7621. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cortes C, Ferreira VP, Pangburn MK. Native properdin binds to Chlamydia pneumoniae and promotes complement activation. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:724–731. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00980-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnard MR, Krueger LA, Frelinger AL, III, Furman MI, Michelson AD. Whole blood analysis of leukocyte-platelet aggregates. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. Chapter. 2003;6:6.15.1–6.15.8. doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy0615s24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pangburn MK. A fluorimetric assay for native C3. The hemolytically active form of the third component of human complement. J. Immunol. Methods. 1987;102:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(87)80003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rawal N, Pangburn MK. C5 convertase of the alternative pathway of complement. Kinetic analysis of the free and surface-bound forms of the enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16828–16835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreira VP, Herbert AP, Hocking HG, Barlow PN, Pangburn MK. Critical role of the C-terminal domains of factor H in regulating complement activation at cell surfaces. J. Immunol. 2006;177:6308–6316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Renner B, Ferreira VP, Cortes C, Goldberg R, Ljubanovic D, Pangburn MK, Pickering MC, Tomlinson S, Holland-Neidermyer A, Strassheim D, Holers VM, Thurman JM. Binding of factor H to tubular epithelial cells limits interstitial complement activation in ischemic injury. Kidney Int. 2011;80:165–173. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeda K, Thurman JM, Tomlinson S, Okamoto M, Shiraishi Y, Ferreira VP, Cortes C, Pangburn MK, Holers VM, Gelfand EW. The critical role of complement alternative pathway regulator factor H in allergen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation. J. Immunol. 2012;188:661–667. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banda NK, Mehta G, Ferreira VP, Cortes C, Pickering MC, Pangburn MK, Arend WP, Holers VM. Essential Role of Surface-Bound Complement Factor H in Controlling Immune Complex-Induced Arthritis. J. Immunol. 2013;190 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spitzer D, Mitchell LM, Atkinson JP, Hourcade DE. Properdin can initiate complement activation by binding specific target surfaces and providing a platform for de novo convertase assembly. J. Immunol. 2007;179:2600–2608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farries TC, Finch JT, Lachmann PJ, Harrison RA. Resolution and analysis of 'native' and 'activated' properdin. Biochem. J. 1987;243:507–517. doi: 10.1042/bj2430507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agarwal S, Ferreira VP, Cortes C, Pangburn MK, Rice PA, Ram S. An evaluation of the role of properdin in alternative pathway activation on Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Immunol. 2010;185:507–516. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pangburn MK, Muller-Eberhard HJ. Relation of a putative thioester bond in C3 to activation of the alternative pathway and the binding of C3b to biological targets of complement. J. Exp. Med. 1980;152:1102–1114. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.4.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwendinger MG, Spruth M, Schoch J, Dierich MP, Prodinger WM. A novel mechanism of alternative pathway complement activation accounts for the deposition of C3 fragments on CR2-expressing homologous cells. J. Immunol. 1997;158:5455–5463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaziri-Sani F, Hellwage J, Zipfel PF, Sjoholm AG, Iancu R, Karpman D. Factor H binds to washed human platelets. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;3:154–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mnjoyan Z, Li J, Afshar-Kharghan V. Factor H binds to platelet integrin alphaIIbbeta3. Platelets. 2008;19:512–519. doi: 10.1080/09537100802238494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan BP. Isolation and characterization of the complement-inhibiting protein CD59 antigen from platelet membranes. Biochem. J. 1992;282(Pt 2):409–413. doi: 10.1042/bj2820409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nicholson-Weller A, Spicer DB, Austen KF. Deficiency of the complement regulatory protein, "decay-accelerating factor", on membranes of granulocytes, monocytes and platelets in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985;312:1091–1096. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198504253121704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Michelson AD, Barnard MR, Krueger LA, Frelinger AL, III, Furman MI. Flow Cytometry. In: Michelson AD, editor. Platelets. New York: Academic Press/Elsevier Science; 2002. pp. 297–315. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rocca B, Patrono C. Prostanoid generation in platelet function: assessment and clinical relevance. In: Quinn M, Fitzgerald D, editors. Platelet Function: Assesment, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2005. pp. 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maclouf J, Folco G, Patrono C. Eicosanoids and iso-eicosanoids: constitutive, inducible and transcellular biosynthesis in vascular disease. Thromb. Haemost. 1998;79:691–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Polley MJ, Nachman RL. Human complement in thrombin-mediated platelet function: uptake of the C5b-9 complex. J. Exp. Med. 1979;150:633–645. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.3.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Polley MJ, Nachman RL, Weksler BB. Human complement in the arachidonic acid transformation pathway in platelets. J. Exp. Med. 1981;153:257–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Broijersen A, Karpe F, Hamsten A, Goodall AH, Hjemdahl P. Alimentary lipemia enhances the membrane expression of platelet P-selectin without affecting other markers of platelet activation. Atherosclerosis. 1998;137:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Broijersen A, Hamsten A, Eriksson M, Angelin B, Hjemdahl P. Platelet activity in vivo in hyperlipoproteinemia--importance of combined hyperlipidemia. Thromb. Haemost. 1998;79:268–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Furman MI, Barnard MR, Krueger LA, Fox ML, Shilale EA, Lessard DM, Marchese P, Frelinger AL, III, Goldberg RJ, Michelson AD. Circulating monocyte-platelet aggregates are an early marker of acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001;38:1002–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]