Abstract

The mammalian gastrointestinal tract contains a large and diverse population of commensal bacteria and is also one of the primary sites of exposure to pathogens. How the immune system perceives commensals in the context of mucosal infection is unclear. Here we show that during a gastrointestinal infection, tolerance to commensals is lost and microbiota-specific T cells are activated and differentiate to inflammatory effector cells. Furthermore, these T cells go on to form memory cells that are phenotypically and functionally consistent with pathogen-specific T cells. Our results suggest that during a gastrointestinal infection, the immune response to commensals parallels the immune response against pathogenic microbes and that adaptive responses against commensals are an integral component of mucosal immunity.

The intestinal microbiome is essential to multiple aspects of host physiology (1). Recent studies have estimated that the human microbiome contains ~3×106 distinct genes each of which may possess multiple antigens (2). Regulating immune responses to this extraordinarily diverse set of antigens is a formidable task because commensals also express inflammatory Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) that could potentially activate the host immune response (3). To limit contact with the commensal microbiota, the gut is compartmentalized and contains various innate and adaptive mechanisms that prevent adaptive immune responses against food and commensal antigens (4–6). Maintaining immune tolerance to commensal–derived antigens in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is critical because activated CD4 T cells have been strongly associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) (7, 8).

The gastrointestinal tract is a common site of infection and whether the immune system discriminates commensals from pathogens is unclear. The pro-inflammatory properties of the microbiota can directly contribute to the induction of immune responses and pathogenesis of mucosal infection (9–11). Whether acute GI infection also leads to priming of adaptive immune responses against commensals has not been addressed. To investigate the fate of immune responses to commensal bacteria following infection, we utilized Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii). Upon oral infection, T. gondii expands systemically in the spleen and locally in the small intestine lamina propria (siLP) where it induces significant immunopathology that is associated with a Th1 immune response and a reduction in regulatory T cells (Tregs) (Fig. 1A and S1)(12). After day 9 p.i., the immune response controls the infection and parasite burden declines in all tissues except the CNS and skeletal muscle, where T. gondii are encysted in an inactive state (Fig. 1A) (13). Oral T. gondii infection also leads to an increased association between the commensal bacteria and the intestinal epithelium (Fig. 1B) (10). Moreover, bacteria escape the gut and translocate to the mesenteric lymph nodes, liver and spleen (Fig. 1C). As a result of bacterial translocation and impaired immune regulation, we postulated that immune ignorance of the microbiota may be lost during T. gondii infection.

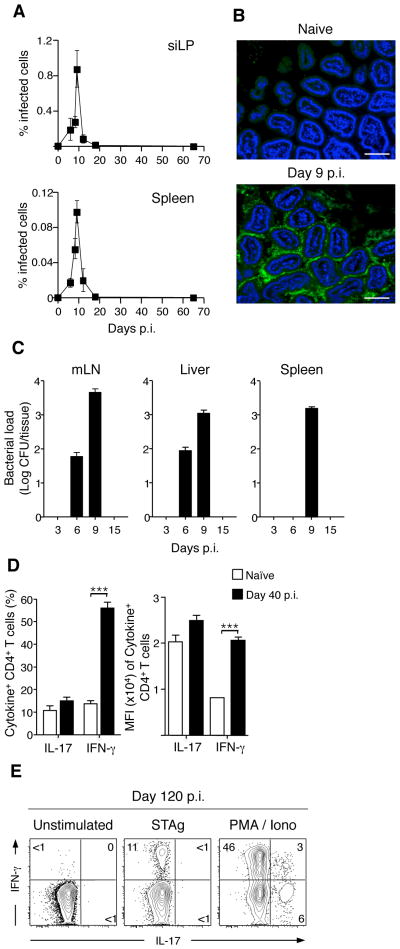

Figure 1. T. gondii infection leads to transient bacterial translocation but persistent lamina propria Th1 T cell responses.

(A) C57Bl/6 mice were infected orally with 15 cysts of RFP-expressing T. gondii. At the times indicated p.i., siLP and spleen were isolated and the percent of cells infected measured via flow cytometric analysis of RFP+ cells; N=1–8, n=3–15 mice per timepoint. (B) Small intestinal samples were isolated from naïve and day 9 T. gondii infected mice. Intestinal samples were then fixed, sectioned, counter-stained with DAPI and hybridized for FISH with a fluorescent probe specific to eubacterial 16S chromosomal sequences. Scale bar indicates 25 μM; N=7 (C) Counts of bacterial colonies cultured from spleen, mesenteric LN (mesLN) and liver at time points indicated post T. gondii infection; N=3, n=3–4 mice per timepoint. (D) Lymphocytes were prepared from the siLP of naïve or day 40 infected mice, stimulated with PMA/ionomycin and stained intracellularly for IFN-γ and IL-17. Bar graph shows the percent (Left) or the Mean Fluorescence Intensity (Right) of CD4+ cells expressing IFN-γ or IL-17. Shown is a representative example of three separate experiments; n=4–6 mice per experiment. (E) CD4 T cells were purified from the siLP by flow cytometry and co-cultured with bone-marrow derived DCs pre-loaded with Soluble T. gondii Antigen (STAg) or activated with PMA/ionomycin for 3.5 hours. Stimulated cells were stained intracellularly for IFN-γ and IL-17 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown is one of two experiments. Flow cytometry of CD4 cells is gated Live TCRβ+ CD4+ Foxp3−. Graphs show mean +/− SEM. ***p<0.001.

Although the gut heals after clearance of T. gondii, the siLP harbored a significantly higher frequency of interferon-γ (IFN- γ+) CD4 T cells compared to naïve mice, whereas the frequency of IL-17A expressing T cells remained unchanged (Fig. 1D). As expected, a fraction of these cells (~10% of CD4 T cells) were T. gondii-specific (Fig. 1E). However, CD4 T cells making IFN-γ in response to non-specific stimulation far outnumbered those responding to T. gondii-derived antigens (~45% of CD4 T cells) implying that a significant proportion of these cells may be specific to commensal bacteria (Fig. 1E).

To circumvent the diversity of commensal antigens, we utilized a TCR transgenic mouse specific to a commensal-derived flagellin (CBir1 Tg), expressed by a subset of the Clostridium XIVa cluster of bacteria (CBir1) (Fig. S2) (14, 15). Importantly, CBir1 is clinically relevant because antibodies to CBir1 flagellin are associated with Crohn’s disease (16). Because of the segregation imposed by the mucosal firewall, splenic T cells from CBir1 Tg mice remain largely naïve (Fig. S3)(15). Remarkably, upon transfer into T. gondii infected hosts CBir1 Tg T cells proliferated extensively, whereas T cells transferred into uninfected hosts remained undivided (Fig. 2A and B). Thus, T cells specific to commensal-derived antigens proliferate during a heterologous GI infection.

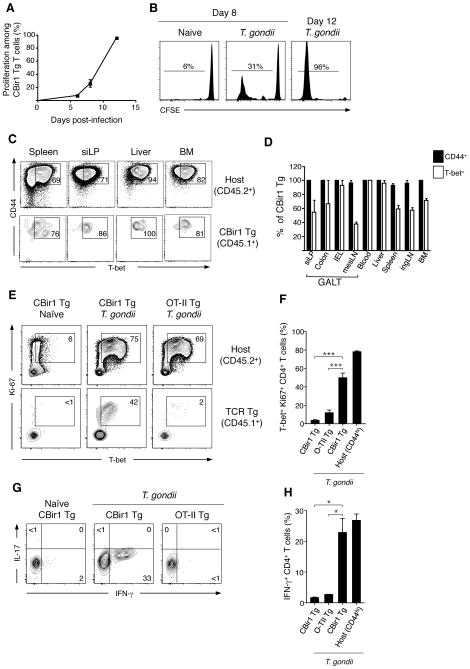

Figure 2. Gastrointestinal infection leads to the activation and Th1 differentiation of microbiota-specific T cells.

(A and B) 105 CBir1 Tg (CD45.1) T cells were labeled with CFSE and transferred into congenic (CD45.2) hosts that were subsequently infected orally with 15 cysts of T. gondii. At 6, 8 or 12 days p.i. splenocytes were isolated and the dilution of CFSE on CBir1 Tg T cells (Live TCRβ+ CD4+ CD45.1+) assessed by flow cytometry; N=1, n=3–4 mice per time point. (C) 7.5×104 CBir1 Tg (CD45.1) T cells were transferred into congenic (CD45.2) hosts that were subsequently infected orally with 15 cysts of T. gondii. Eighteen days p.i., single cell suspensions were prepared from the spleen, ingLN, mesLN, bone marrow, liver, peripheral blood, siLP, IEL and colon and stained intracellularly for flow cytometry. Contour plots show expression of CD44 and T-bet amongst CBir1 Tg (CD45.1) CD4 T cells (bottom row) and host CD4+ T cells (D) Bar graph showing the frequency of CBir1 Tg T cells from (C) expressing CD44 (black bars) and Tbet (white bars); N=1–8, n=3 mice. (E) 7.5×104 CBir1 Tg (CD45.1) or OTII T cells were transferred into congenic (CD45.2) hosts that were subsequently infected orally with 15 cysts of T. gondii or left naïve. Eight days p.i. splenocytes were isolated and stained intracellularly for flow cytometry. Flow cytometric analysis of T-bet and Ki67 in CBir1 Tg or OTII TCR Tg (bottom row) and host CD44hi CD4 T cells (top row). Shown is a representative example of eight separate experiments. (F) Quantification of (E). (G) Splenocytes from (E) were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin, stained intracellularly for IFN-γ and IL-17 and analyzed by flow cytometry. (H) Quantification of (G). Data is representative of three separate experiments. All flow cytometry plots in this figure are gated on Live TCRβ+ CD4+ Foxp3−. Graphs show mean +/- SEM *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

We next addressed whether commensal-specific T cells would differentiate to become effector cells during gastrointestinal infection. Strikingly, after T. gondii infection, CBir1 Tg T cells on WT or Rag−/− background differentiated towards a Th1 phenotype, as demonstrated by the expression of the canonical transcription factor T-bet (Fig. 2C,D and S4). On the other hand, ovalbumin-specific OTII TCR transgenic cells transferred into T. gondii infected mice remained naïve and CBir1 Tg T cells did not respond to direct stimulation with T. gondii antigens indicating that CBir1 Tg T cell responses rely on cognate antigen recognition (Fig. 2E,F and S5). Activated commensal-specific T cells produced IFN-γ in response to ex vivo stimulation and were observed in all tissues examined indicating that anti-commensal T cell responses are systemic and functional (Fig. 2C,D,G,H and S6). Taken together, our data show that during GI infection CD4 T cell ignorance of commensal antigens is lost, and microbiota-specific T cells respond in a manner comparable to pathogen-specific T cells.

Under homeostatic conditions, the commensal microbiota can drive the differentiation of Tregs and Th17 cells (11, 17–21). Interestingly, CBir1 Tg T cells did not induce the expression of IL-17A or the transcription factors Rorγt or Foxp3 during T. gondii infection (Fig. 2G and 3D) indicating that microbiota-specific T cells are differentiating according to signals provided by the inflammatory milieu that are not typically present at steady-state. Supporting this hypothesis, we found that CBir1 Tg T cells activated during chemical disruption of the GI tract by Dextran Sodium Sulfate (DSS), did not up-regulate T-bet but instead expressed Rorγt (Fig. S7).

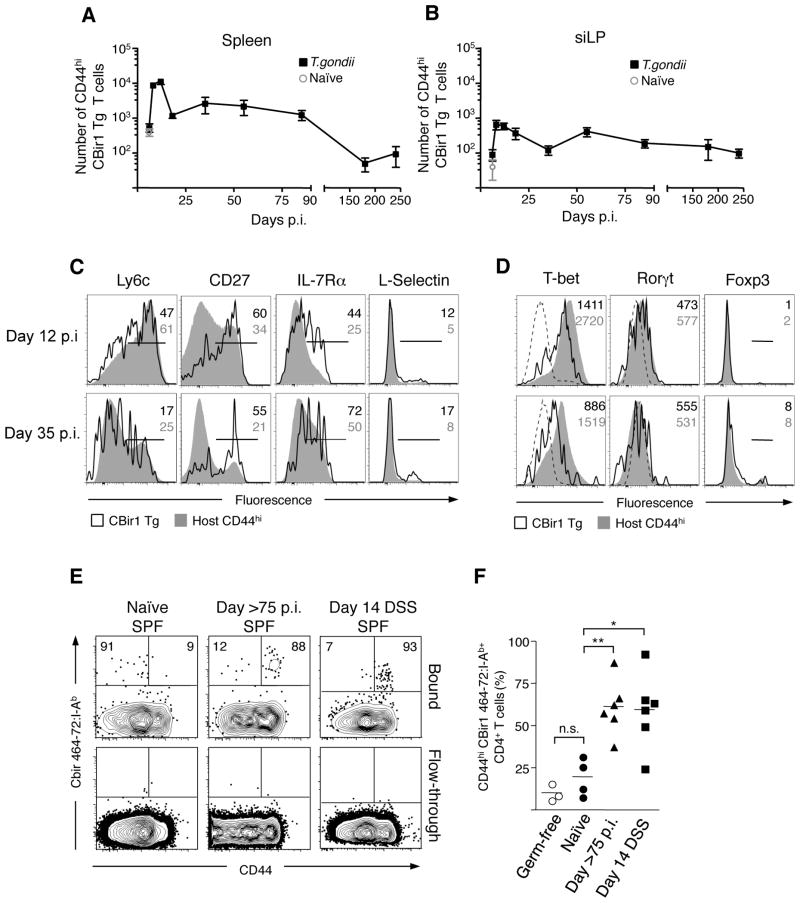

Figure 3. Gastrointestinal infection induces microbiota-specific memory CD4 T cells.

(A and B) 7.5×104 CBir1 Tg (CD45.1) T cells were transferred into congenic (CD45.2) hosts that were subsequently infected orally with 15 cysts of T. gondii. At the days indicated, splenocytes (A) and siLP cells (B) were isolated and the number of CD44hi CBir1 Tg T cells (black squares) in each tissue was assessed by flow cytometry. Open grey circle shows the number of CD44hi CBir1 Tg T cells in naïve mice eight days after transfer of CBir1 Tg T cells; N=1–8, n=3–15 mice per timepoint (C) Flow cytometric analysis of surface marker phenotype of transferred CBir1 Tg T cells (CD45.1) (black line) and host CD44hi T cells (CD45.2) (grey filled) at day 12 and day 35 p.i. isolated from the spleen (D) Expression of transcription factors in CBir1 Tg T cells (CD45.1) (black line) and host CD44hi T cells (CD45.2) (grey filled) at day 12 and day 35 p.i. isolated from the spleen. Histograms in (C) and (D) are gated on Live TCRβ+ CD4+; Data shown is representative of three separate experiments (E) Flow cytometric analysis of CBir464- 72:I-Ab tetramer binding populations from the total secondary lymphoid tissue in naïve, >day 75 T. gondii infected and DSS-treated mice. The top row depicts the population bound during tetramer-specific separation; the bottom row shows the non-binding column flow-through to show specificity. Plots are gated on DAPI− NK1.1− F4/80− CD11c− CD11b− B220− CD3+ CD4+. (F) Bar graph shows the percent CD44hi of CBir464–72:I-Ab tetramer binding cells in germ-free (open circles), naïve (circles), infected (triangles) and DSS-treated (squares) mice. Data from (E) are representative of three experiments. Graphs show mean +/− SEM *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Immunological memory is a cardinal property of the adaptive immune system allowing for long- term protection against re-infection. During acute infections, Th1 T cell responses persist after the clearance of the pathogen but slowly decay over time (22, 23). Whether microbiota-specific effector T cells persist as memory cells is a critical question. Assessment of CBir1 Tg T cell response revealed that the number of effector (CD44hi) CBir1 Tg T cells expanded approximately ten fold from day 6 to the peak of the anti-microbiota response at day 12 p.i. in both the spleen and siLP (Fig 3A and B). In accordance with what has been observed for pathogen-specific CD4 T cell responses, CBir1 Tg T cells contracted significantly after day 12 of infection (Fig 3A and B) (22, 23). However, small populations of CD44hi CBir1 Tg T cells can be identified from both the spleen and lamina propria up to 240 days after infection, indicating that microbiota-specific cells generated in the context of heterologous GI infection have the potential for long term survival (Fig. 3A and B). Th1 CD4 T cells with increased potential to survive and form memory can be separated from terminally differentiated cells by the characteristic expression of CD27 and low expression of Ly6c and T-bet (23–25). Strikingly commensal-specific T cells largely differentiate to a phenotype consistent with long-lived Th1 memory T cells (Fig. 3C and D). Critically, survival of memory CBir1 Tg cells was not the consequence of continuous antigen exposure as naïve CBir1 Tg T cells transferred into mice 90 days p.i. with T. gondii did not respond (Fig. S8). In order to control for possible artifacts associated with the transfer of transgenic T cells, we examined the endogenous anti-CBir1 flagellin response via an MHC class II multimer (26, 27). In agreement with our T cell transfer studies, the majority of CBir1 multimer positive cells in specific pathogen free and germ free mice were naïve (CD44lo) (Fig. 3E and F). In contrast, 75 days post T. gondii infection, the majority of CBir1 specific cells displayed an activated (CD44hi) phenotype, indicating that the endogenous population of CBir1-specific cells is activated after GI infection and survives long-term as memory cells (Fig. 3E,F and S9). In accordance with results obtained with transferred CBir1 Tg T cells, CD44hi CBir1 tetramer specific cells expressed lower levels of Ly6c and increased amounts of CD27 than T. gondii-specific cells from the same time point of infection (Fig. S10). The majority of CBir1-specific T cells was also activated in mice treated with DSS, highlighting the importance of GI tract integrity in maintenance of CD4 T cell ignorance to commensal antigens (Fig. 3E and F). Therefore, commensal-specific T cells activated during GI infection survive long-term and persist in extra-lymphoid tissue in a manner consistent with pathogen-specific memory cells.

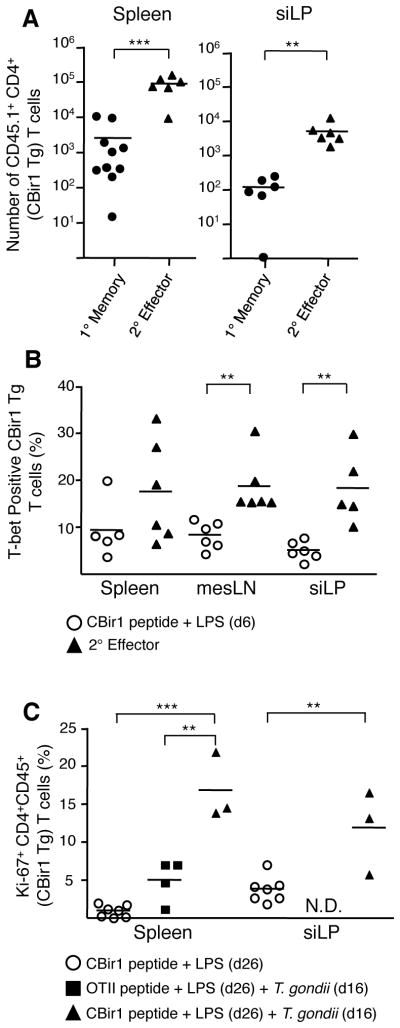

A fundamental property of memory T cells is the ability to proliferate rapidly and elicit effector functions in response to secondary challenge. Indeed, CBir1 Tg T cells were able to rapidly make IFN-γ and IL-2 in response to stimulation with specific peptide 75 days p.i. (Fig. S11). To test whether persisting commensal-specific T cells also maintain proliferative potential, we infected mice carrying CBir1 Tg T cells, then re-challenged the mice with CBir1 peptide 35 days later. Prior to peptide challenge, CBir1 Tg T cells were uniformly activated (Fig. S12). Memory CBir1 Tg T cells proliferated after antigen-specific challenge and accumulated in both the spleen and siLP (respectively 34 and 42 fold expansion) (Fig. 4A). In comparison to naïve CBir1 Tg T cells after activation with peptide and LPS, memory CBir1 Tg T cells maintained a significant level of expression of T-bet and had notably reduced expression of IL-7Rα (Fig. 4B and S13). Therefore, after recall, commensal-specific memory cells have a phenotype distinct from primary effectors and associated with their previous polarization. We next tested whether an established commensal-specific T cell population could be re-activated by gastrointestinal infection. To address this point, we activated naïve CBir1 Tg T cells in vivo with peptide and LPS, waited for the primary immune response to subside and then infected mice with T. gondii. Notably, secondary infection induced proliferation of a fraction of CBir1 Tg T cells, in both the siLP and spleen as indicated by expression of Ki67 (Fig. 4C). Thus, activated commensal-specific T cells can proliferate in response to infectious re-challenge.

Figure 4. Microbiota-specific memory T cell are functional and can be re-activated by gastrointestinal infection.

(A) 7.5×104 CBir1 Tg (CD45.1) T cells were transferred into congenic (CD45.2) hosts that were subsequently infected orally with 15 cysts of T. gondii. 35 days p.i. with T. gondii mice carrying CBir1 Tg T cells were injected with CBir1 peptide and LPS. Numbers of CBir1 Tg T cells (CD45.1) in the spleen and siLP at day 35 (1° memory) or six days post stimulation with CBir peptide and LPS (2° effector). Shown is a composite of three experiments. (B) Either naïve hosts carrying ~104 naïve CBir1 Tg T cells (open circles) or day 35 (1° memory) T. gondii infected mice (black triangles) were injected with CBir peptide and LPS as in (A). Six days post-injection splenocytes were isolated and stained intracellularly for T-bet. Data shown is representative of three experiments. (C) Naïve hosts carrying ~104 naïve CBir1 Tg or OTII Tg T cells were injected with peptide and LPS. Ten days post-immunization these mice were infected with 15 cysts T. gondii. Percent Ki67+ CBir1 Tg T cells isolated from the spleen and siLP from mice 16 days post-infection (26 days post-immunization). Data shown are representative of 3 separate experiments. CBir1 Tg T cells are gated Live TCRβ+ CD4+ Foxp3− CD45.1+. Graphs show mean +/− SEM **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

The GI tract represents a major site of exposure to pathogens and our results indicate these pathogenic exposures may lead to long-lived anti-commensal immunity (28, 29). In support of this hypothesis, healthy human serum contains antibodies specific to the intestinal microbiota (30). Therefore, due to the comparative abundance of commensal antigens, a fraction of the memory CD4 T cell population induced in response to GI infection is likely composed of various commensal-specific clones that together may constitute a substantial population. Further, our results suggest that primary immune responses to GI infections occur in the context of broader secondary responses against commensals. Several genes involved in sustaining the intestinal barrier and CD4 function have been associated with IBD and in the context of such mutations, regulation of activated commensal-specific T cells could be jeopardized leading to immunopathology (7). Indeed, GI barrier dysfunction and infection have been shown to synergize to induce IBD in ATG16L1 hypomorph mice (31). As bacteria colonize all pathogen entryways, such as the skin, lung and GI Tract, our findings raise the question of whether immunity and inflammation at barrier sites is generally controlled by responses to commensals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (TWH, LMD, NB, MJM and YB), CNPq-Brazil (LMD), NIH grants DK071176 and DK64400 (COE) and The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Career Development Award (CLM). The authors would like to thank Drs. A. Poholek, S. Kaech, N. Peters and the members of the Belkaid Lab for critical discussion and reading of the manuscript; the NIH Tetramer Core Facility for the T. gondii Me49 hypothetical protein tetramers; C. Eigsti, T. Moyer, E. Stregevsky, K. Holmes and the NIAID Flow Cytometry Core for assistance with sorting; Dr. L. Koo and the NIAID Microscopy Core for assistance with 16S FISH images; and the NIAID Protein Biochemistry Core for CBir1 peptide. We thank the University of Alabama-Birmingham for sharing the CBir1 Tg mice by MTA. The data reported in this paper are tabulated in the main text and in the supplementary materials.

Footnotes

This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Science. This version has not undergone final editing. Please refer to the complete version of record at http://www.sciencemag.org/. The manuscript may not be reproduced or used in any manner that does not fall within the fair use provisions of the Copyright Act without the prior, written permission of AAAS.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kau AL, Ahern PP, Griffin NW, Goodman AL, Gordon JI. Nature. Jun 16;474:327. doi: 10.1038/nature10213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qin J, et al. Nature. Mar 4;464:59. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Nat Immunol. 2004 Oct;5:987. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macpherson AJ, Slack E, Geuking MB, McCoy KD. Semin Immunopathol. 2009 Jul;31:145. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macpherson AJ, Uhr T. Science. 2004 Mar 12;303:1662. doi: 10.1126/science.1091334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slack E, et al. Science. 2009 Jul 31;325:617. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franke A, et al. Nat Genet. Dec;42:1118. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Annu Rev Immunol. Mar;28:573. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson A, Pifer R, Behrendt CL, Hooper LV, Yarovinsky F. Cell Host Microbe. 2009 Aug 20;6:187. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heimesaat MM, et al. J Immunol. 2006 Dec 15;177:8785. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivanov, et al. Cell. 2009 Oct 30;139:485. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oldenhove G, et al. Immunity. 2009 Nov 20;31:772. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munoz M, Liesenfeld O, Heimesaat MM. Immunol Rev. Mar;240:269. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duck LW, et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007 Oct;13:1191. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, Elson CO. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Nov 17;106:19256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812681106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lodes MJ, et al. J Clin Invest. 2004 May;113:1296. doi: 10.1172/JCI20295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atarashi K, et al. Science. Jan 21;331:337. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, et al. Immunity. 2009 Oct 16;31:677. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geuking MB, et al. Immunity. May 27;34:794. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lathrop SK, et al. Nature. Oct 13;478:250. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lochner M, et al. J Immunol. Feb 1;186:1531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrington LE, Janowski KM, Oliver JR, Zajac AJ, Weaver CT. Nature. 2008 Mar 20;452:356. doi: 10.1038/nature06672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pepper M, et al. Nat Immunol. Jan;11:83. doi: 10.1038/ni.1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall HD, et al. Immunity. Oct 28;35:633. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Eur J Immunol. 2009 Aug;39:2076. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moon JJ, et al. Immunity. 2007 Aug;27:203. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hataye J, Moon JJ, Khoruts A, Reilly C, Jenkins MK. Science. 2006 Apr 7;312:114. doi: 10.1126/science.1124228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosek M, Bern C, Guerrant RL. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vernacchio L, et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Jan;25:2. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000214961.90326.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haas A, et al. Gut. Nov;60:1506. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cadwell K, et al. Cell. Jun 25;141:1135. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.