Abstract

Objective

Methamphetamine use has become a growing problem in a number of countries over the past two decades, but has only recently emerged in South Africa. This study investigated the prevalence of methamphetamine use among high-school students in Cape Town and whether students reporting methamphetamine use were more likely to be at risk for mental health and aggressive behavior problems.

Method

A cross-sectional survey of 15 randomly selected high-schools in Cape Town, of 1561 male and female grade 8–10 students (mean age 14.9), was conducted using the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (POSIT) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

Results

Findings indicated that 9% of the students had tried methamphetamine at least once. Ordinal logistic regression analyses showed that methamphetamine use in the past year was significantly associated with higher aggressive behavior scores (OR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.04–3.15, p < 0.05), mental health risk scores (OR = 2.04, 95% CI: 1.26–3.31, p < 0.01) and depression scores (OR = 2.65, 95% CI: 1.64–4.28, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Methamphetamine use has become a serious problem in Cape Town, particularly among adolescents. Screening adolescents in school settings for methamphetamine use and behavior problems may be useful in identifying youth at risk for substance misuse, providing an opportunity for early intervention. These findings have implications for other parts of the world where methamphetamine use may be occurring at younger ages and highlight the importance of looking at co-morbid issues related to methamphetamine use.

Keywords: Adolescents, methamphetamine use, aggression, mental health, South Africa

1. Introduction

Methamphetamine use has been documented as a serious cause for concern in a number of countries, including the Czech Republic, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Thailand and some parts of the United States. Traditionally, levels of methamphetamine (and other amphetamine) use have been low in Africa (United Nations Office on Drugs & Crime, 2008). However, data collected from drug treatment centers in Cape Town began to show significant numbers of patients reporting methamphetamine use in 2004. This grew exponentially in subsequent years, reaching a peak in 2006, when 72% of adolescent patients admitted for substance abuse or dependence counseling in Cape Town reported methamphetamine as a primary or secondary drug problem (Pluddemann et al., 2008a).

The identification of an emerging methamphetamine problem among adolescents in Cape Town, based on drug treatment data, prompted the need for population-based surveys to determine both the extent of this problem as well as to begin to investigate associated health consequences. Use mostly involved smoking crystalline methamphetamine. Smoking crystalline methamphetamine has been associated with high levels of harm (Topp et al., 2002). The most salient harms associated with methamphetamine use are mental health problems, including psychosis, depression, anxiety and violent behaviors (Darke, Kaye, McKetin, & Duflou, 2008). Few studies have reported on these problems in adolescent populations. A study among male and female adolescents in the pacific islands found that those who used methamphetamine were significantly more likely to participate in aggressive behaviors (Pinhey & Wells, 2007). Another study among a general population of adolescents was from the 2002 US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which found that adolescents who reported past-year mental health treatment utilization were 1.66 times more likely than adolescents who did not seek mental health treatment to report past-year MA use (Herman-Stahl, Krebs, Kroutil, & Heller, 2006).

The aim of the present study was to examine the relationship between methamphetamine use and mental health and aggression among adolescents. Furthermore, the present study aimed to expand on a still fairly limited body of research globally on the effects and consequences of methamphetamine use by adolescents. To our knowledge, it is also the first study investigating methamphetamine use and mental health problems and aggressive behavior in Africa. The authors feel it is very important to establish the above mentioned associations in ‘new and different’ contexts, particularly in contexts already affected by extreme poverty and other ‘social stressors’. The authors propose that the cohort in the present study is in fact unique, in terms of age (i.e. the high prevalence of methamphetamine use in 15 year-olds on average) and socio-political climate (i.e. young persons growing up in a rapidly changing society fairly recently coming out of a repressive historical past).

2. METHODS

2.1 Design and sampling strategy

The school population was all high schools (N=54) in the South Educational District, one of four education management districts in the city of Cape Town. Fifteen schools were randomly selected from this population, such that the probability of selection was directly proportional to the number of students in the school. This district was believed to be the most affected by methamphetamine use, based on treatment demand data and newspaper and other anecdotal reports. Subsequently one class of approximately 30 students was randomly selected from each of grades 8 (majority aged 12–14), 9 (majority aged 14–15 and 10 (majority aged 15–17). Data were collected in July and August 2006.

2.2 Procedures

Questionnaires were administered by trained staff in a standardized way in a classroom setting without the presence of school staff. Students were seated in such a way as to preserve confidentiality. Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) were used to administer the questionnaires and students were able to choose from one of three major local languages (English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa). PDAs have been used in a number of local studies and have been found to be very effective (Jaspan et al., 2007; Seebregts et al., 2009).

Each student provided informed assent. Parents were informed of the study by letter and given the opportunity to withdraw their child from the study. Very few parents withdrew their children from the study and very few students refused to participate. Of over 1600 students approached to participate, only 50 refused or were withdrawn from the study. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the University of Cape Town’s Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee.

2.3 Measures

The questionnaire included basic demographics, substance use history, the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (POSIT) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). In order to obtain an impression of the socio-economic status (SES) of the learners, a question asking learners to describe their ‘living circumstances’ by selecting one of five categories was used. The options were: ‘We don’t have enough money for food’, ‘We have enough money for food, but not clothes’, ‘We have enough money for food and clothes, but are short of other things’, ‘We have the most important things, but few luxuries’, and ‘We have money for luxury goods and extra things’. A question relating to what type of home/dwelling they lived in was also asked. Substance use measures covered tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, methaqualone, cocaine, heroin, ecstasy and methamphetamine. For each of these substances students were asked whether they had ever tried them, and whether they had used them in the past 12 months, past 30 days, and past seven days.

The POSIT (Rahdert, 1991) consists of 139 yes/no questions which are sub-divided into 10 sub-scales. The current study used data from the mental health scale (22 items) and the aggressive behavior/delinquency scale (16 items). A few minor linguistic adjustments were made to the POSIT questions in accordance with South African English and the questions were piloted with students, and then translated and back translated into both Afrikaans and isiXhosa (the two common local languages). Reliability analysis on data collected in the present study showed good Cronbach’s alpha values (above 0.7) for both the mental health scale (0.80) and the aggressive behavior/delinquency scale (0.75).

These sub-scales are scored in terms of three categories: low risk, middle risk and high risk, indicating potential risk for problems in these domains.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to screen for symptoms of depression (Beck et al., 1996). The BDI has been used and found to be reliable in a number of international contexts, including in local studies (Kagee, 2008). Kagee found an internal reliability of 0.85 as measured by Cronbach’s alpha. A second study by Ward et al. on the reliability of the BDI found good test-retest reliability using Cohen’s kappa and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 (Ward et al., 2003). The present study’s data indicated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91.

2.4 Data analysis

Data was analysed using SPSS 16.0 and STATA 10. For the calculation of the substance use prevalence confidence intervals we took the study design (clustering at school level) into account in STATA’s survey analysis settings. Chi-square tests were used for basic comparisons. As a tool to try to address the issue around the use of multiple substances by participants, we used Multiple Correspondence Analysis. In correspondence analysis (Greenacre, 2007) an attempt is made to find a low dimensional graphical representation of the association between the rows and columns of a contingency table. It is an exploratory multivariate technique that converts frequency table data into graphical displays in which rows and columns are depicted as points. Much of the value of correspondence analysis relates to its multivariate treatment of data through the simultaneous consideration of multiple categorical variables. The multivariate nature of correspondence analysis can reveal relationships that would not be detected in a series of pair wise comparisons of variables. Correspondence analysis also helps to show how variables are related, not merely that a relationship exists. The graphical display can help in detecting structural relationships among variable categories. A relationship is generally indicated between variables that appear in the same region of space. However points on the plot clustered around the origin remain unresolved in the analysis. While recognizing the relative rarity, and perhaps therefore unfamiliarity of multiple correspondence analysis to a number of readers, the authors have nevertheless decided to include it in this manuscript, as we feel Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) is one of few robust techniques which can assist in analysis of this type of categorical data, which is very common in social sciences research.

Ordinal logistic regression was performed to establish the size and significance of the association between methamphetamine use and mental health indices, after adjusting for confounders. The outcome variables in these regressions were risk categories on the POSIT mental health and aggressive behavior/delinquency scales (low risk, middle risk, high risk) and the BDI risk categories (none, medium and high). Methamphetamine use (past year use) was the main predictor variable in these analyses, and adjustment was made for factors that were shown to be related to both methamphetamine use and mental health indices in the correspondence analysis and where tests of association were significant (p < 0.05). We also tested our models for the assumption of proportional odds using generalized ordinal logistic models (gologit in STATA) and all p-values were greater than 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

The final sample comprised 1561 students, with slightly more females (53%) than males. The majority identified themselves as ‘Coloured’ (76%), with 43% reporting Afrikaans as their home language and 38% English. [Note: The terms “white”, “black”, and “Coloured”, became entrenched in the apartheid era. They refer to demographic markers and do not signify inherent characteristics. They refer to people of European, African and mixed (African, European and/or Asian) ancestry, respectively. These markers were chosen for their historical significance. Their continued use in South Africa is important for monitoring improvements in health and socio-economic disparities, identifying vulnerable sections of the population, and planning effective prevention and intervention programs.] The mean age of the students was 14.9 years (SD = 1.36). The ages ranged from 12 to 20 years. Based on the SES, almost 75% of the students came from lower to middle income households (i.e. they chose one of the first four options of the SES question). Most however lived in a brick house or apartment (69%), while 10% lived in a “shack” (a roughly constructed dwelling, sometimes from wood, corrugated iron or other ‘waste’ or scrap building material), and 12% lived in a “Wendy house” (a small home made from wood, often built in the yard of another (brick) home, sometimes used for sub-letting).

3.2 Substance use

Table 1 shows the proportions of students reporting the use of various substances, from ‘life-time use’ (“Have you ever tried substance?”) to use of the substance in the past seven days. The Table shows that tobacco use was most common, followed by alcohol and cannabis. Almost 9% of the students had tried methamphetamine at least once, while 3% or less had tried Mandrax (methaqualone), cocaine, Ecstasy or heroin. Reported substance use in the past seven days was generally low, except for tobacco. Tobacco and alcohol use proportions were very similar for male and female students. Male students were, however, more likely to have tried cannabis (29.3%) than female students (20.8%). These differences also held for more recent cannabis use. Males were also slightly more likely to have tried Mandrax, cocaine or crack, Ecstasy or heroin than females. Ten percent of the male students had tried methamphetamine at least once compared with 8% of the female students. However the proportion of males who had tried methamphetamine in the past 12 months (6.4%) was almost twice the proportion for the females (3.3%).

Table 1.

Self-reported drug use (N = 1561)

| Lifetime % 95% CI | Past 12 months % 95% CI | Past 30 days % 95% CI | Past 7 days % 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco | 60.2 (53.2–67.1) | 33.0 (27.2–38.8) | 27.2 (21.6–32.8) | 25.4 (20.6–30.2) |

| Alcohol | 54.1 (48.8–59.3) | 22.0 (15.3–28.7) | 12.5 (9.0–16.0) | 7.1 (5.0–9.2) |

| Cannabis | 24.8 (20.9–28.7) | 12.9 (10.3–15.4) | 7.7 (6.1–9.3) | 6.4 (4.9–7.9) |

| Methamphetamine | 8.8 (6.2–11.4) | 4.7 (3.1–6.4) | 2.8 (1.6–3.9) | 1.8 (1.0–2.6) |

| Mandrax(methaqualone) | 2.6 (1.8–3.3) | 1.1 (0.4–1.71) | 0.6 (0.1–1.0) | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) |

| Cocaine/crack | 2.5 (1.5–3.5) | 1.3 (0.6–2.0) | 0.5 (0.1–0.9) | 0.6 (0.1–1.0) |

| Ecstasy | 3.2 (2.2–4.2) | 1.2 (0.7–1.7) | 0.6 (0.2–1.0) | 0.5 (0.1–0.9) |

| Heroin | 2.2 1.6–2.9 |

1.0 0.6–1.5 |

0.6 0.2–1.0 |

0.4 0.1–0.8 |

3.3 Methamphetamine and POSIT scores

Table 2 compares three groups of students on the two subscales of the POSIT: students who have never used methamphetamine, students who have used methamphetamine, but not in the past 12 months, and students who have used methamphetamine in the past 12 months. Students who reported having used methamphetamine in the past 12 months had the highest proportions in the ‘high risk’ categories. Chi-square tests for the POSIT subscales were significant across columns at p < 0.001, indicating significant differences.

Table 2.

POSIT subscale category scores for various groups of students by methamphetamine use (%)

| Non-meth. users (n=1424) | Life-time meth. users (n=63) | Past year meth. users (n=74) | Chi-squarea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health | ||||

| Low risk | 39.4 | 27.0 | 14.9 | 28.6 |

| Middle risk | 41.7 | 44.4 | 47.3 | df = 4 |

| High risk | 18.9 | 28.6 | 37.8 | p < 0.001 |

| Aggressive behavior/delinquency | ||||

| Low risk | 28.3 | 12.7 | 6.8 | 56.6 |

| Middle risk | 64.1 | 69.8 | 64.9 | df = 4 |

| High risk | 7.6 | 17.5 | 28.4 | p < 0.001 |

For comparison across the categories of methamphetamine use/non-use

Note: This Table compares three groups of students on the two subscales of the POSIT: students who have never used methamphetamine, students who have used methamphetamine, but not in the past 12 months, and students who have used methamphetamine in the past 12 months.

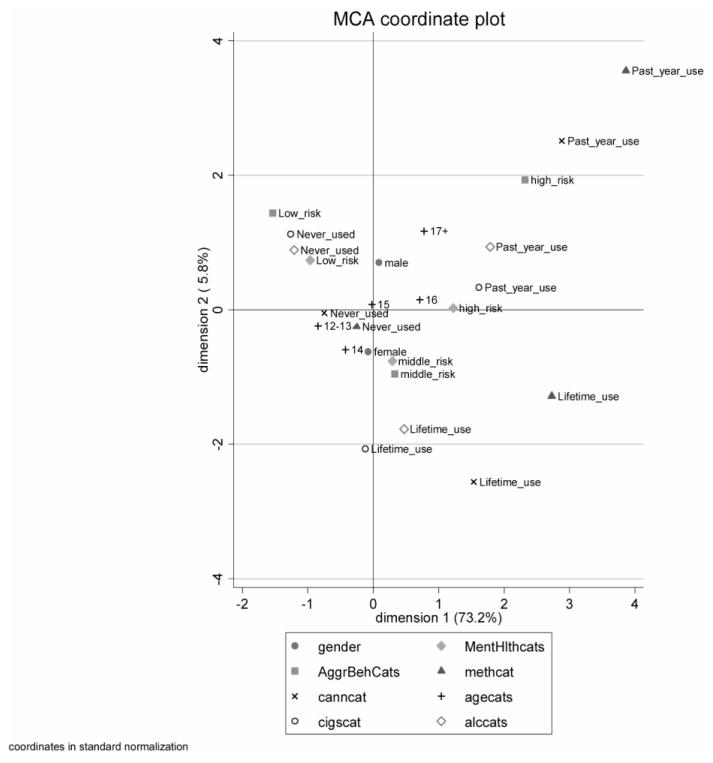

The Multiple Correspondence Analysis (for included variables see Figure 1) indicated an association between methamphetamine use and both aggression and poor mental health. Methamphetamine use was also closely associated with cannabis use, and the use of both substances was associated with ‘high risk’ scores on the POSIT aggressive behavior scale and the Mental Health Scale. The use of tobacco and alcohol in the past 12 months also appeared to be associated with these variables (all appeared in a proximal region of space on the MCA graph, especially on Dimension 1, indicating an association: Figure 1), as did being older (16 or older). On dimension 1 (which accounted for 73% of the Chi-square information in the analysis), life-time use of cannabis and methamphetamine also appeared to be associated with high risk scores on the aggression and mental health scales.

Figure 1.

Multiple correspondence analysis co-ordinate plot for selected variables (N=1536) [Note: Some co-ordinates have been graphically shifted slightly to enhance legibility] [cigscat=Tobacco use categories (Life-time use = not used in the past year), alccats=Alcohol use categories, canncat=Cannabis use categories, methcat=Methamphetamine use categories, MentHlthcats=mental health risk scale categories, AggrBehcats=aggressive behavior risk scale categories, Agecats=age categories (i.e. 12–13, 14, 15, 16, 17+)]

In order to confirm the significance of these associations, and estimate the size of these effects after adjusting for potential confounders, an ordinal logistic regression was undertaken. Using the risk categories on the aggressive behavior/delinquency scale as the outcome variable (low, middle and high), we tested whether methamphetamine use was associated with aggression, adjusting for cannabis, alcohol and tobacco use in the past 12 months. In this model, past year methamphetamine use almost doubled the odds of being in a higher risk category for aggression (adjusted OR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.04–3.15, p < 0.05). (Age and gender were also considered as possible confounders of aggression but were not found to be related to the POSIT aggression scale.) In a similar model, methamphetamine use in the past year was a significantly associated with being in a higher mental health risk category (adjusted OR = 2.04, 95% CI: 1.26–3.31, p < 0.01). In this model we adjusted for age (in four categories: 12–14 years, 15 years, 16 years and 17+ years) and gender, in addition to cannabis, alcohol and tobacco use in the past 12 months, as these variables were found to be related to both methamphetamine use and mental health risk scores.

3.4 Methamphetamine use and depression

Table 3 compares students’scores on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) categories. The table shows that higher proportions of students who had tried methamphetamine had scores in the ‘borderline clinical depression’ to ‘severe depression’ categories compared with those who had never tried methamphetamine. Comparing the ‘raw scores’ on the BDI of students who had never tried methamphetamine with students who had tried methamphetamine with a Mann-Whitney U test showed significant differences (Z = −3.364, p < 0.01), with methamphetamine users more likely to have high BDI scores.

Table 3.

Beck Depression Inventory categories for students who have tried methamphetamine versus students who have not

| Never tried meth (n=1424) % | Life-time meth users (n=137) % | |

|---|---|---|

| None | 9.5 | 7.3 |

| Normal ups/downs | 47.3 | 33.6 |

| Mild mood disturbance | 14.0 | 15.3 |

| Borderline clinical depression | 6.4 | 10.9 |

| Moderate depression | 12.6 | 18.2 |

| Severe depression | 7.1 | 10.9 |

| Extreme depression | 3.1 | 3.6 |

| Methamphetamine use by collapsed BDI categories | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Life-time meth use (n=63)a | Past year use (n=74) | ||

| None | 56.8 | 54.0 | 29.7 |

| Medium | 20.4 | 25.4 | 27.0 |

| High | 22.8 | 20.6 | 43.2 |

Used methamphetamine, but not in past 12 months

In order to simplify the categories of the BDI, the seven categories of the BDI were collapsed into three groups: students in the ‘none’ or ‘normal ups and downs’ range (none), students with ‘mild mood disturbance’ or ‘borderline clinical depression’ (medium), and students who scored from ‘moderate depression’ to ‘extreme depression’ (high). Students were also grouped into three categories of methamphetamine use: 1) never used, 2) used methamphetamine but not in the past 12 months, and 3) used methamphetamine in the past 12 months. Table 3 shows that students who had used methamphetamine in the past year were more likely to be in the ‘high’ BDI category than the other two groups of students. A Chi-square test comparing ‘life-time’ and ‘past year’ users showed a significant difference between these groups (χ2 = 10.22, df = 2, p < 0.01). A comparison, using a Chi-square, test between those who had never used and ‘life-time’ users was not significant.

As a Multiple Correspondence Analysis plot using the three BDI categories was less clear to interpret (graph not shown), we again used ordinal logistic regression. An ordinal logistic regression model, using the newly created three categories for the BDI indicated methamphetamine use in the past year as a significant indicator of being in a higher depression category (OR = 2.65, 95% CI: 1.64–4.28, p < 0.001), adjusting for cannabis use in the past 12 months and age category (based on Chi-square tests for associations). Alcohol and tobacco use in the past year and gender were not found to be associated with BDI scores and were hence not included as covariates.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study indicate substantial use of methamphetamine among students in Cape Town high schools. The life-time prevalence of 9% found in this study is cause for concern and supports data collected from substance abuse treatment centres in the city. The prevalence was slightly higher than the life-time prevalence of 8% found in a 2003 U.S. national high-school survey (Springer et al., 2007). However the prevalence was slightly lower than was found in a study conducted among high school students in Cape Town a year earlier (12%) (Pluddemann et al., 2008b). The sample in that study was drawn from all schools in the city, perhaps indicating the problem to be more widespread than was thought to be the case, but also indicating the possibility of a reduction in use from 2005 to 2006. The past year prevalence found in the present study of 4.7% was comparable to the 4.2% (past year amphetamine use for 12–17 year-olds) found in a national survey of schools in Australia in 2005 (White & Hayman, 2006), a country with one of the highest reported methamphetamine prevalence figures in the world (UNODC, 2008).

Our findings indicated some significant associations between recent methamphetamine use and certain mental health problems (including depression) and aggressive behavior. Students who have used methamphetamine recently (or more regularly) appear to be at greatest risk for potential mental health problems and higher levels of aggressive behavior.

The findings regarding the association between aggressive behavior and methamphetamine use support those of other studies, although most previous studies refer specifically to ‘violent behavior’ and were conducted in adult samples (Baskin-Sommers & Sommers, 2006; Hall et al., 1996; Iritani et al., 2007). While the finding does indicate an association, it also raises questions similar to those posed by Tyner and Fremouw, in a critical review of the relationship between methamphetamine use and violence (Tyner & Fremouw, 2008). These questions relate to whether methamphetamine is a direct cause of aggression and violence, or whether certain circumstances around the use of the drug may lead to aggression or violence. Some of these circumstances are discussed in a review by Dawe et al. (in press), and include, for example, the role sleep deprivation (commonly induced by methamphetamine use) may play in increased aggression. Another point made in this review is that amphetamine use is associated with increased positive symptoms of psychosis, particularly paranoia, that contribute to a perception of the environment as a hostile, threatening place, another potential catalyst for aggression.

Findings regarding the association between methamphetamine use and mental health problems also support those of a number of previous studies, although many of these studies have recruited samples in drug treatment settings, where underlying co-morbidity may be more prevalent, perhaps complicating the interpretation of some of these findings (Baker et al., 2004; Grant et al., 2007; Rawson et al., 2005). One of the few other studies among a general population of adolescents was from the 2002 US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which found that adolescents who reported past-year mental health treatment utilization were 1.66 times more than adolescents who did not seek mental health treatment to report past-year methamphetamine use (Herman-Stahl et al., 2006). While the Mental Health risk scale of the POSIT consists of a fairly broad range of questions relating to various mental health issues, it provides a useful indication of potential mental health problems.

Methamphetamine use in the past year was also a significant indicator of a higher depression score on the BDI, again confirming previous findings on the association between methamphetamine use and depression ( London et al., 2004; Looby & Earleywine, 2007; Newton et al., 2004). Again, the samples in these studies mostly represented older individuals (over 25 years) or individuals in drug treatment settings. The present findings indicate associations between methamphetamine use and depression in a fairly ‘early stage of use’ and among a relatively young age group–certainly an issue of concern given the critical stage of development adolescents are in.

The limitations of the present study include that it was cross-sectional, with no mental health and behavior histories of the participants forming part of the analyses. Larger cohort studies are necessary to determine the causal pathways of methamphetamine use on mental health and aggressive behavior more clearly. A number of the other POSIT sub-scales did not yield good reliability scores in our setting and may need to be revised for use outside the U.S. The Mental Health and Aggressive Behavior scales however showed encouraging reliability in our setting. Future studies may benefit from utilizing more differential data on frequency of methamphetamine use, although sample sizes may need to be increased along with this to enable analysis by frequency of use. The data collected on SES also did not follow expected patterns, when correlated with methamphetamine use, and was therefore not included in the analysis models. (Students in a higher SES group appeared slightly more likely to have used methamphetamine in the past year, although a Chi-square test did not show this as significant). While the authors believe that SES was not a key factor in the investigated associations, a more detailed approach to ascertain participants SES may have been beneficial.

The findings of the present study indicate high levels of methamphetamine use among school-attending adolescents in Cape Town, and indicate potential mental health and aggressive behavior problems among those who report recent use. The study is, to our knowledge, the first to confirm these associations in a context of extreme poverty and strenuous social circumstances. Many of the adolescents surveyed live in areas with high levels of unemployment (over 30%), overcrowded housing, and particularly crime (including violent crime, such as murder, rape and child abuse). We therefore feel that this study has made a unique contribution by indicating that even in contexts where adolescents may already be severely ‘disadvantaged’, methamphetamine appears to contribute significantly to even poorer prospects for the adolescents that use it regularly (or recently). The authors contend that the cohort in the present study was unique, in terms of age (i.e. the high prevalence of methamphetamine use in 15 year-olds on average) and socio-political climate (i.e. young persons growing up in a rapidly changing society fairly recently coming out of a repressive historical past).

Screening adolescents in school settings for these mental health and behavior problems may be useful in identifying youth at risk for substance misuse, providing an opportunity for early intervention. These findings also have implications for other parts of the world where methamphetamine use may be occurring at younger ages and highlight the importance of looking at co-morbid issues related to methamphetamine use. The findings also indicate that in South Africa (and other countries including the USA), the policy of education authorities to reduce the psychological services support available to high-schools may need to be revised, as a need for these is clearly indicated, perhaps particularly with a drug like methamphetamine. This recommendation may well also apply to education policies in many other countries and the critical examination of these policies may serve in improving the prevention of drug abuse among high-school students.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) under grant number RO1 DA11609, via a subcontract through Research Triangle Institute (RTI) in North Carolina, USA. The interpretations and conclusions do not represent the position of NIDA or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of all the field workers who assisted in the data collection, the principals and teachers of the participating schools for their co-operation, Dr Chris Seebregts and his colleagues for their support with the PDA technology, and all the students who so willingly participated in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors have materially participated in the research and/or manuscript preparation. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Author AP was the principal investigator of the study and primarily responsible for the drafting of the manuscript. Authors AF, RM and CP were involved in the design of the study, revisions of the manuscript, and supervision of the study throughout. Authors CP and CL assisted with statistical analysis and guidance on methods of analysis.

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Baker A, Lee NK, Claire M, Lewin TJ, Grant T, Pohlman S, Saunders JB, Kay-Lambkin F, Constable P, Jenner L, Carr VJ. Drug use patterns and mental health of regular amphetamine users during a reported ‘heroin drought’. Addiction. 2004;99:875–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Sommers A, Sommers I. Methamphetamine use and violence among young adults. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2006;34:661–674. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. BDI-II manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J. Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27:253–62. doi: 10.1080/09595230801923702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Davis P, Lapworth K, McKetin R. Mechanisms underlying aggressive and hostile behavior in amphetamine users. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2009;22:269–273. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832a1dd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KM, Kelley SS, Agrawal S, Meza JL, Meyer JR, Romberger DJ. Methamphetamine use in rural Midwesterners. American Journal on Addictions. 2007;16:79–84. doi: 10.1080/10550490601184159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenacre M. Interdisciplinary Statistics: Correspondence Analysis in Practice. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Hando J, Darke S, Ross J. Psychological morbidity and route of administration among amphetamine users in Sydney, Australia. Addiction. 1996;91:81–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9118110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Stahl M, Krebs CP, Kroutil LA, Heller DC. Risk and protective factors for nonmedical use of prescription stimulants and methamphetamine among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iritani BJ, Hallfors DD, Bauer DJ. Crystal methamphetamine use among young adults in the USA. Addiction. 2007;102:1102–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspan H, Flisher AJ, Mathews C, Seebregts C, Berwick JR, Wood R, Bekker LG. Methods for collecting sexual behavior information from South African adolescents - a comparison of paper versus personal digital assistant questionnaires. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagee A. Symptoms of depression and anxiety among a sample of South African patients living with a chronic illness. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13:547–555. doi: 10.1177/1359105308088527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London ED, Simon SL, Berman SM, Mandelkern MA, Lichtman AM, Bramen J, Shinn AK, Miotto K, Learn J, Dong Y, Matochik JA, Kurina V, Newton T, Woods R, Rawson R, Ling W. Mood disturbances and regional cerebral metabolic abnormalities in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:73–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looby A, Earleywine M. The impact of methamphetamine use on subjective well-being in an Internet survey: preliminary findings. Human Psychopharmacology. 2007;22:167–172. doi: 10.1002/hup.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton TF, Kalechstein AD, Duran S, Vansluis N, Ling W. Methamphetamine abstinence syndrome: preliminary findings. American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13:248–255. doi: 10.1080/10550490490459915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhey TK, Wells NR. Asian-Pacific islander adolescent methamphetamine use: Does ‘Ice’ increase aggression and sexual risk? Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:1801–1809. doi: 10.1080/10826080701205448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluddemann A, Flisher AJ, Mathews C, Carney T, Lombard C. Adolescent methamphetamine use and sexual risk behavior in secondary school students in Cape Town, South Africa. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008b;27:687–692. doi: 10.1080/09595230802245253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluddemann A, Myers BJ, Parry CD. Surge in treatment admissions related to methamphetamine use in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for public health. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008a;27:185–189. doi: 10.1080/09595230701829363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahdert ER. The Adolescent Assessment/Referral System Manual. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Gonzalez R, Obert JL, McCann MJ, Brethen P. Methamphetamine use among treatment-seeking adolescents in Southern California: participant characteristics and treatment response. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seebregts CJ, Zwarenstein M, Mathews C, Fairall L, Flisher AJ, Seebregts C, Mukoma W, Klepp KI. Handheld computers for survey and trial data collection in resource-poor settings: Development and evaluation of PDACT, a Palmtrade mark Pilot interviewing system. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2009 Jan 19; doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer A, Peters R, Shegog R, White D, Kelder S. Methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors in U.S. high school students: Findings from a national risk behavior survey. Prevention Science. 2007;8:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp L, Degenhardt L, Kaye S, Darke S. The emergence of potent forms of methamphetamine in Sydney, Australia: a case study of the IDRS as a strategic early warning system. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2002;21:341–348. doi: 10.1080/0959523021000023199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyner EA, Fremouw WJ. The relation of methamphetamine use and violence: A critical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:285–297. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ward CL, Flisher AJ, Zissis C, Muller M, Lombard C. Reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory and the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale in a sample of South African adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2003;15:73–75. doi: 10.2989/17280580309486550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White V, Hayman J. Australian Government; 2006. [Accessed 19 March 2009]. Australian secondary school students’ use of over-the counter and illicit substances in 2005. http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/publishing.nsf/Content/mono60. [Google Scholar]