Abstract

Context:

Quadriceps and hamstrings weakness occurs frequently after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury and reconstruction. Evidence suggests that knee injury may precipitate hip and ankle muscle weakness, but few data support this contention after ACL injury and reconstruction.

Objective:

To determine if hip, knee, and ankle muscle weakness present after ACL injury and after rehabilitation for ACL reconstruction.

Design:

Case-control study.

Setting:

University research laboratory.

Patients or Other Participants:

Fifteen individuals with ACL injury (8 males, 7 females; age = 20.27 ± 5.38 years, height = 1.75 ± 0.10 m, mass = 74.39 ± 13.26 kg) and 15 control individuals (7 men, 8 women; age = 24.73 ± 3.37 years, height = 1.75 ± 0.09 m, mass = 73.25 ± 13.48 kg).

Intervention(s):

Bilateral concentric strength was assessed at 60°/s on an isokinetic dynamometer. The participants with ACL injury were tested preoperatively and 6 months postoperatively. Control participants were tested on 1 occasion.

Main Outcome Measures:

Hip-flexor, -extensor, -abductor, and -adductor; knee-extensor and -flexor; and ankle–plantar-flexor and -dorsiflexor strength (Nm/kg).

Results:

The ACL-injured participants demonstrated greater hip-extensor (percentage difference = 19.7, F1,14 = 7.28, P = .02) and -adductor (percentage difference = 16.3, F1,14 = 6.15, P = .03) weakness preoperatively than postoperatively, regardless of limb, and greater postoperative hip-adductor strength (percentage difference = 29.0, F1,28 = 10.66, P = .003) than control participants. Knee-extensor and -flexor strength were lower in the injured than in the uninjured limb preoperatively and postoperatively (extensor percentage difference = 34.6 preoperatively and 32.6 postoperatively, t14 range = −4.59 to −4.23, P ≤ .001; flexor percentage difference = 30.6 preoperatively and 10.6 postoperatively, t14 range = −6.05 to −3.24, P < .05) with greater knee-flexor (percentage difference = 25.3, t14 = −4.65, P < .001) weakness preoperatively in the injured limb of ACL-injured participants. The ACL-injured participants had less injured limb knee-extensor (percentage difference = 32.0, t28 = −2.84, P = .008) and -flexor (percentage difference = 24.0, t28 = −2.44, P = .02) strength preoperatively but not postoperatively (extensor: t28 = −1.79, P = .08; flexor: t28 = 0.57, P = .58) than control participants. Ankle–plantar-flexor weakness was greater preoperatively than postoperatively in the ACL-injured limb (percentage difference = 31.9, t14 = −3.20, P = .006).

Conclusions:

The ACL-injured participants presented with hip-extensor, -adductor, and ankle–plantar-flexor weakness that appeared to be countered during postoperative rehabilitation. Our results confirmed previous findings suggesting greater knee-extensor and -flexor weakness postoperatively in the injured limb than the uninjured limb. The knee extensors and flexors are important dynamic stabilizers; weakness in these muscles could impair knee joint stability. Improving rehabilitation strategies to better target this lingering weakness seems imperative.

Key Words: isokinetic exercises, knee, weakness

Key Points.

Quadriceps and hamstrings weakness in the injured limb persisted when individuals returned to activity after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Determining the cause of and developing more effective strategies to address quadriceps and hamstrings weakness are important.

Ankle–plantar-flexor weakness was present preoperatively in the injured limb but was effectively addressed with rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

The hip extensors and adductors were stronger postoperatively than preoperatively, suggesting that postoperative strength gains were made with rehabilitation.

Traumatic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury occurs frequently during athletic activity, precipitating numerous immediate and long-term consequences, such as pain, disability, and ultimately joint degeneration.1 Lower extremity muscle weakness, particularly in the quadriceps and hamstrings, also is reported commonly after ACL injury and reconstruction, often lingering well beyond the postoperative rehabilitation period.2,3

Quadriceps strength deficits in the injured limb reportedly range from 5% to 40%2–10 and have been noted as long as 7 years after surgery.3 Hamstrings strength deficits in the injured limb have been reported to range from 9% to 27%2,3,5,8,9,11 and have been reported 3 years after surgery.5 Similarly, quadriceps and hamstrings strength deficits in the uninjured limbs of patients who have had ACL reconstruction have been reported to be 21% and 14%, respectively, 3 years after surgical repair.5

Less often considered is the strength of the hip and triceps surae musculature. Clinical observation and emerging evidence8 have suggested that strength within these muscle groups may be influenced negatively by the injury and reconstruction processes. Jaramillo et al12 reported hip-flexor and -extensor and hip-abductor and -adductor weakness after knee surgery, but their results were not limited to a population that had ACL reconstruction. The presence of both hip-flexor8 and -adductor13 weakness has been confirmed after ACL reconstruction. Hip-flexor weakness has been reported 2 years after surgery in the injured compared with the uninjured limb.8 Persistent quadriceps weakness may have contributed to hip-flexor weakness, given the biarticular nature of the rectus femoris. Hiemstra et al13 reported hip-adductor weakness after semitendinosus and gracilis autograft reconstruction and suggested that donor site morbidity and neurologic alterations may have contributed to the resultant weakness. At the ankle, Karanikas et al8 noted no differences bilaterally in isokinetic ankle–plantar-flexor strength between 3 and 6 months or between 6 and 12 months after surgery; however, researchers using ultrasound to assess calf muscle thickness have demonstrated preoperative to postoperative reductions in muscle thickness after traditional rehabilitation,14 which indicates calf muscle atrophy and, likely, weakness.

Considering the importance of muscle strength for controlling lower limb dynamic stability15,16 and considering that long-term sequelae, such as osteoarthritis, have been proposed to result from lingering muscle weakness,17 confirming and quantifying the presence of lower extremity muscle weakness seems imperative so that strategies to counter it can be better implemented within rehabilitation protocols. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to determine if weakness was present in the hip-, knee-, and ankle-flexor and -extensor musculature and the hip abductors and adductors after ACL injury and after ACL reconstruction and postoperative rehabilitation. We hypothesized that participants would demonstrate weakness preoperatively and postoperatively within the (1) hip-flexor, -extensor, and -abductor muscle groups; (2) knee flexors and extensors; and (3) ankle–plantar-flexor and -dorsiflexor musculature. We believed these deficits would be present in the injured but not in the uninjured limb of the ACL-injured participants or in the test limb of the control participants.

METHODS

Participants

Fifteen individuals with ACL injury (8 males, 7 females; age = 20.27 ± 5.38 years, height = 1.75 ± 0.10 m, mass = 74.39 ± 13.26 kg) and 15 control participants (7 men, 8 women; age = 24.73 ± 3.37 years, height = 1.75 ± 0.09 m, mass = 73.25 ± 13.48 kg) were included in this study. Control participants were age matched (±2 years) and activity matched (±1 point on the Tegner physical activity scale18) to the participants in the ACL-injured group. Control participants were included because we could not guarantee that the uninjured limbs of participants with ACL injury were not affected by the injury and reconstruction processes. A power analysis based on pilot data collected in our laboratory on individuals who had ACL reconstruction revealed that 13 participants per group would be needed to achieve quadriceps and hamstrings isokinetic strength differences between the injured and uninjured limbs with 80% statistical power and an α level of .05.

Potential participants had to have sustained a complete ACL rupture during athletic activity and to have received a diagnosis of ACL rupture from a physician within 1 month of sustaining the injury. Individuals were excluded if they (1) had a history of surgery to either knee, (2) had a previous partial ACL tear, (3) had other ligamentous damage concurrent with ACL injury, or (4) were not scheduled for ipsilateral ACL reconstruction with bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) autograft. Pregnant females also were excluded. Potential participants for the control group were further excluded if they had a history of any lower extremity surgery or had injured the lower extremity in the 6 months before the study. Six surgeons from 1 sports medicine clinic performed all ACL reconstructions using a standardized patellar tendon autograft procedure. The rehabilitation completed by all ACL-injured participants in this study was performed at 1 outpatient clinic and was a standard rehabilitation protocol conducted 2 to 3 times per week. Rehabilitation began during the first postoperative week and concluded during the 12th through 16th postoperative weeks, depending on the individual's progression. Rehabilitation emphasized knee range of motion, muscle strengthening, and functional exercises (Appendix). Any preoperative rehabilitation performed emphasized restoring knee range of motion. All participants provided written informed consent, and the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan Medical School approved the study.

Strength-Testing Procedures

The ACL-injured participants reported for testing on 2 occasions: preoperatively (mean days postinjury = 68.6, range = 15–311) and upon clearance for return to activity postoperatively (mean days after surgery = 212.5, range = 157–220). Control participants reported for testing on 1 occasion only. One examiner (A.C.T.) performed all strength assessments. Concentric strength was assessed bilaterally for each muscle group on an isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex System 3; Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, NY) and was recorded using a custom-written Labview program (version 8.5; National Instruments Corporation, Austin, TX). Strength was tested at 60°/s, which is a common angular velocity for assessing strength before and after ACL reconstruction.8,10,11,19 Three maximal voluntary concentric contractions were performed for each muscle group tested. The peak value over those 3 repetitions was normalized to participant body mass (kg) and used to quantify strength (Nm/kg). Spoken encouragement was provided throughout testing to help elicit each participant's maximal effort. Testing order (limb and muscle group) was counterbalanced before participant enrollment.

Hip Strength

For all hip-strength measurements, the mechanical axis of the dynamometer was aligned with the greater trochanter of the limb being tested, and the distal femur was strapped to the arm of the dynamometer. Specifically, for assessment of hip-flexor and -extensor strength, participants stood facing away from the back of the dynamometer chair (Figure 1).20 For assessment of hip abduction and adduction, participants were positioned side lying on the dynamometer chair with the hip in a neutral position (Figure 2). Participants were instructed to keep the trunk as still as possible, and they were instructed to abduct or adduct the hip and not to rotate, flex, or extend it. The full available range of motion was used for strength assessment for both muscle groups during testing.

Figure 1. .

Participant positioning for hip-flexor and -extensor strength testing.

Figure 2. .

Participant positioning for hip-abductor and -adductor strength testing.

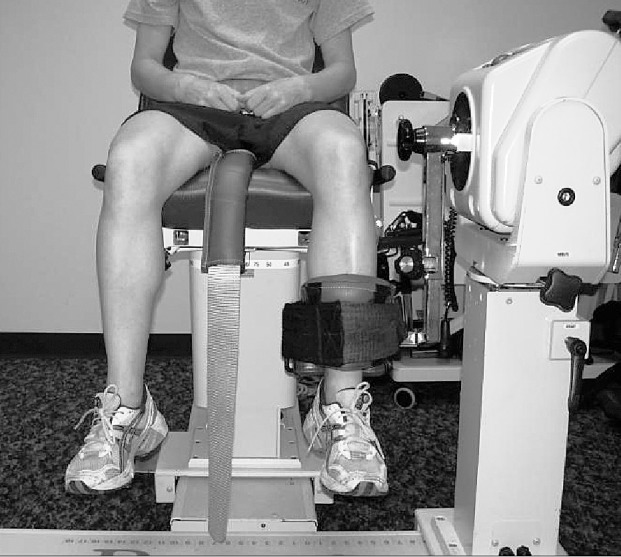

Knee Strength

For knee flexion and extension, participants were seated on the dynamometer chair with the hip flexed to 85°.2 The mechanical axis of the dynamometer was aligned with the lateral aspect of the knee-joint center of the limb being tested, and the distal shank was strapped to the arm of the dynamometer (Figure 3). A stabilization strap was placed over the pelvis. Participants were instructed to move the knee from 0° to 100° of flexion during testing.2 If participants lacked full extension, they were instructed to move through the full available range of motion during testing.

Figure 3. .

Participant positioning for knee-flexor and -extensor strength testing.

Ankle Strength

Ankle–plantar-flexor and -dorsiflexor strength were assessed with participants positioned supine on the dynamometer chair with the knee flexed to approximately 15° (Figure 4).21 This position was chosen to avoid discomfort at full knee extension but still to target the gastrocnemius muscle as much as possible. The mechanical axis of the dynamometer was aligned with the lateral malleolus of the limb being tested, and the foot was strapped to the foot-plate attachment of the dynamometer. The full available range of motion was used for strength assessment.

Figure 4. .

Participant positioning for ankle–plantar-flexor and -dorsiflexor strength testing.

Statistical Analyses

The dependent variables used for analysis were strength (Nm/kg) of each muscle group (hip flexors and extensors and hip abductors and adductors, knee flexors and extensors, ankle plantar flexors and dorsiflexors). The independent variables were limb (injured and uninjured for the ACL-injured group and test and contralateral [randomly determined] for the control participants), group (ACL injured, control), and time (preoperatively, postoperatively). We used 2 × 2 repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to examine the dependent variables in the ACL-injured group between limbs and over time. In addition, limb × group ANOVAs were performed to compare the dependent variables between the ACL-injured and control groups. Separate limb × group analyses were performed for the preoperative and postoperative time points because the control participants were tested at only a single time point. The α level was set a priori at equal to or less than .05. Sidak multiple-comparisons procedures and paired t tests were used for all post hoc analyses. Effect sizes and their associated confidence intervals were calculated in Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) using the Cohen d.22 For all other analyses, SPSS (version 17.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) was used.

RESULTS

Hip Strength

ACL-Injured Group Only

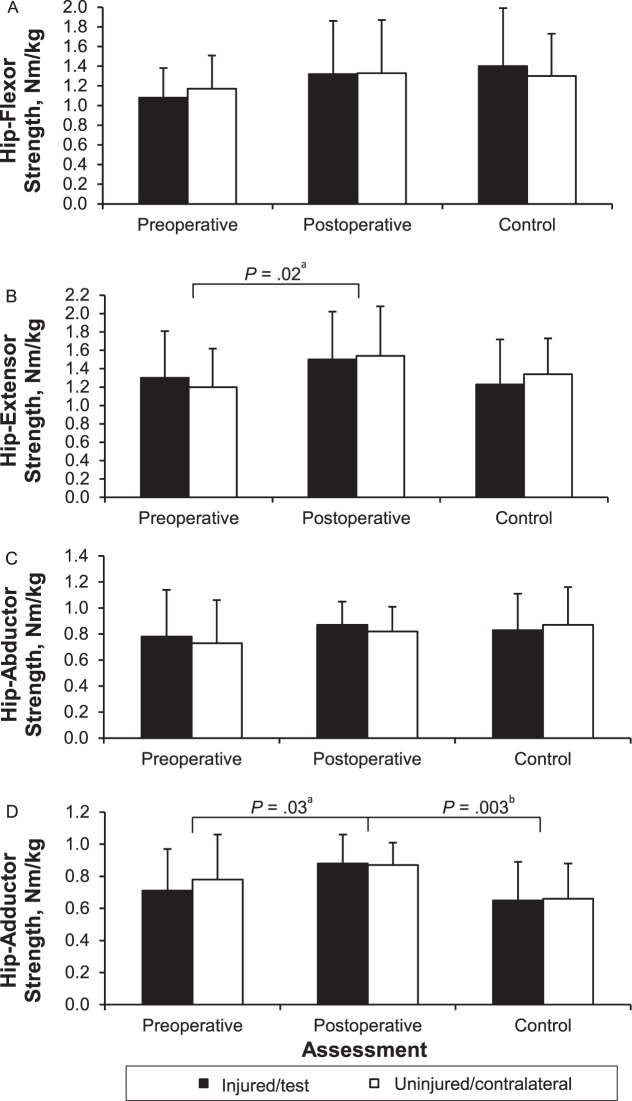

When both limbs were considered together, the hip-extensor (percentage difference = 19.7, F1,14 = 7.28, P = .02) and -adductor (percentage difference = 16.3, F1,14 = 6.15, P = .03) muscle groups were stronger postoperatively than preoperatively. No differences in hip-flexor (F1,14 = 3.211, P = .10) or -abductor (F1,14 = 1.93, P = .19) strength were found. Furthermore, hip-muscle strength was not different between limbs regardless of time (flexors: F1,14 = 1.23, P = .29; extensors: F1,14 = 0.20, P = .66; abductors: F1,14 = 1.44, P = .25; adductors: F1,14 = 0.80, P = .39). When limbs were compared across time for the ACL-injured group, no differences were revealed (flexors: F1,14 = 0.66, P = .43; extensors: F1,14 = 1.15, P = .30; abductors: F1,14 = 0.02, P = .88; adductors: F1,14 = 2.40, P = .14) (Figure 5A through D).

Figure 5. .

Hip-flexor, A, -extensor, B, -abductor, C, and -adductor, D, strength data for participants with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury and control participants. Data are means ± SDs. a Indicates main effect for time. b Indicates strength differences between the ACL-injured and control participants.

ACL-Injured Versus Control Group

No limb × group interactions were present for any hip muscle group preoperatively (flexors: F1,28 = 2.20, P = .15; extensors: F1,28 = 1.77, P = .19; abductors: F1,28 = 1.11, P = .30; adductors: F1,28 = 1.14, P = .29) or postoperatively (flexors: F1,28 = 0.85, P = .37; extensors: F1,28 = 0.18, P = .68; abductors: F1,28 = 2.84, P = .10; adductors: F1,28 = 0.08, P = .77). Preoperatively, hip strength was not different between groups when both limbs were considered together (flexors: F1,28 = 2.60, P = .12; extensors: F1,28 = 0.08, P = .78; abductors: F1,28 = 0.83, P = .37; adductors: F1,28 = 1.10, P = .30); however, postoperatively, hip-adductor strength was greater in participants with ACL reconstruction than in control participants (percentage difference = 29.0, F1,28 = 10.66, P = .003). No other postoperative strength differences presented between groups (flexors: F1,28 = 0.03, P = .87; extensors: F1,28 = 2.04, P = .17; abductors: F1,28 = 0.01, P = .91). Hip strength also was not different between limbs preoperatively (flexors: F1,28 = 0.01, P = .95; extensors: F1,28 < 0.001, P = .99; abductors: F1,28 < 0.001, P = .99; adductors: F1,28 = 1.96, P = .17) or postoperatively (flexors: F1,28 = 0.44, P = .51; extensors: F1,28 = 1.07, P = .31; abductors: F1,28 = 0.03, P = .87; adductors: F1,28 = 0.01, P = .92).

Knee Strength

ACL-Injured Group

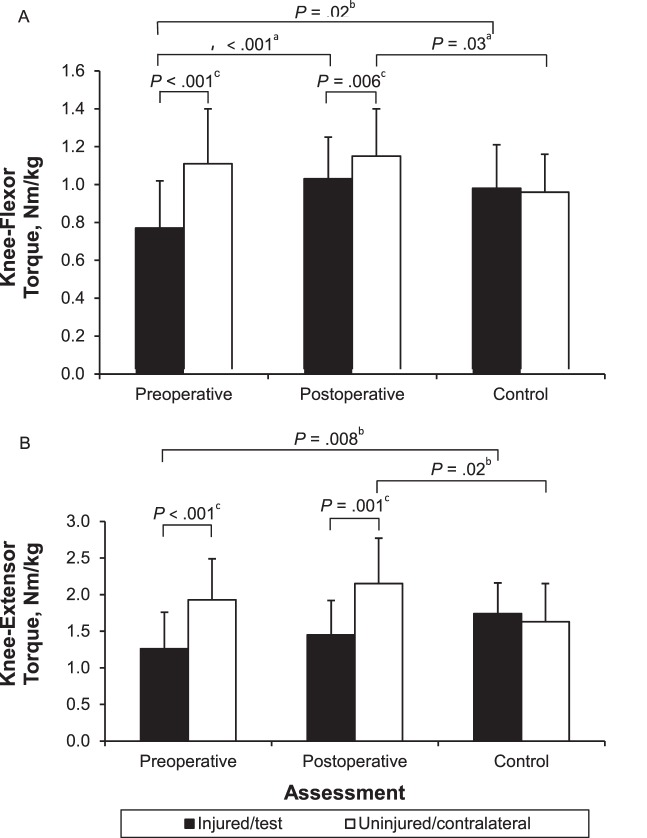

We found a time × limb interaction for the knee flexors (F1,14 = 10.27, P = .006) but not for the extensors (F1,14 = 0.04, P = .84) (Figure 6A and B). Post hoc testing revealed that knee-flexor strength was less preoperatively than postoperatively in the injured limb (percentage difference = 25.3, t14 = −4.65, P < .001) but not the uninjured limb (t14 = −0.45, P = .66). In addition, the injured limb was weaker than the uninjured limb preoperatively (percentage difference = 30.6, t14 = −6.05, P < .001) and postoperatively (percentage difference = 10.6, t14 = −3.24, P = .006).

Figure 6. .

Knee-flexor, A, and -extensor, B, strength data for participants with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury and control participants. Data are means ± SDs. a Indicates main effect for time. b Indicates strength differences between the ACL-injured and control participants. c Indicates main effect for limb.

ACL-Injured Versus Control Group

We found limb × group interactions preoperatively and postoperatively for both the knee extensors (preoperative: F1,28 = 13.16, P = .001; postoperative: F1,28 = 12.18, P = .002) and knee flexors (preoperative: F1,28 = 31.22, P < .001; postoperative: F1,28 = 8.49, P = .007). For preoperative knee-extensor strength, the post hoc analyses revealed greater weakness in the injured than the test limb (percentage difference = 32.0, t28 = −2.84, P = .008) but no difference between the uninjured and contralateral limbs (t28 = 1.52, P = .14). Furthermore, knee-extensor strength in the injured limb was less than that in the uninjured limb (percentage difference = 34.6, t14 = −4.59, P < .001). Control participants did not demonstrate knee-extensor strength differences between limbs (t14 = 0.67, P = .52). Post hoc analyses for preoperative knee-flexor strength similarly revealed greater weakness in the injured limb of the ACL-injured group than the test limb of the control group (percentage difference = 24.0, t28 = −2.44, P = .02) but no difference between the uninjured limb of the ACL-injured group and the contralateral limb of the control group (t28 = 1.64, P = .11). Control participants did not demonstrate knee-flexor strength differences between limbs (t14 = 0.70, P = .50).

For postoperative knee-extensor strength, post hoc analyses demonstrated that the uninjured limb of participants in the ACL-injured group was stronger than the contralateral limb of control participants (percentage difference = 27.5, t28 = 2.50, P = .02). We found no differences between strength in the injured and test limbs (t28 = −1.79, P = .08). Furthermore, knee-extensor strength was less in the injured than in the uninjured limb (percentage difference = 32.6, t14 = −4.23, P = .001) of the ACL-injured group. Postoperatively, the knee flexors similarly demonstrated greater strength in the uninjured than the contralateral limb (percentage difference = 18.0, t28 = 2.30, P = .03) but no differences between the injured and test limbs (t28 = 0.57, P = .58).

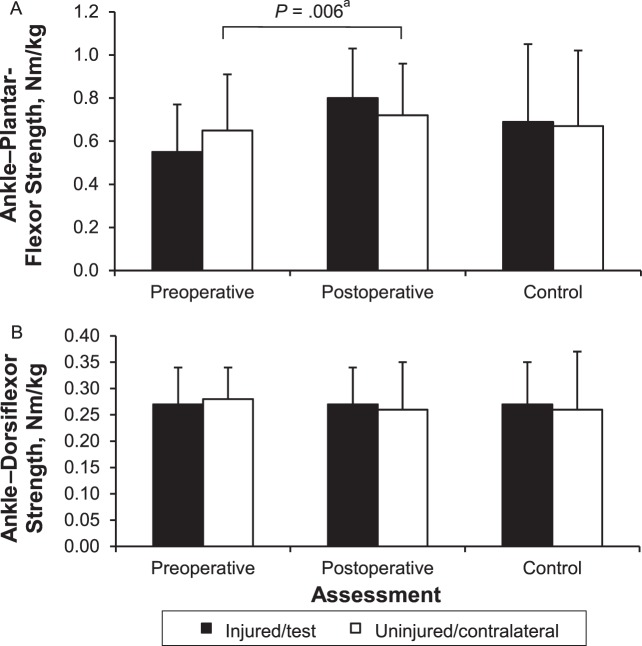

Ankle Strength

ACL-Injured Group

We found a limb × time interaction for the ankle plantar flexors (F1,14 = 9.09, P = .009) but not the dorsiflexors (F1,14 = 0.37, P = .55) (Figure 7A and B). Post hoc analyses revealed that the plantar flexors of the injured limb were weaker preoperatively than postoperatively (percentage difference = 31.9, t14 = −3.20, P = .006), but no differences were noted for the uninjured limb between the preoperative and postoperative time points (t14 = −0.80, P = .44). Furthermore, we found no differences between limbs for plantar-flexor strength preoperatively (t14 = −2.06, P = .06) or postoperatively (t14 = 1.95, P = .07).

Figure 7. .

Ankle–plantar-flexor, A, and -dorsiflexor, B, strength data for participants with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury and control participants. Data are means ± SDs. a Indicates main effect for time.

ACL-Injured Versus Control Group

We found no limb × group interactions preoperatively (plantar flexors: F1,28 = 3.00, P = .09; dorsiflexors: F1,28 = 0.41, P = .53) or postoperatively (plantar flexors: F1,28 = 0.68, P = .42; dorsiflexors: F1,28 = 0.02, P = .89) for either muscle group. Furthermore, we found no strength differences between groups preoperatively (plantar flexors: F1,28 = 0.60, P = .45; dorsiflexors: F1,28 = 0.23, P = .66) or postoperatively (plantar flexors: F1,28 = 0.58, P = .45; dorsiflexors: F1,28 = 0.01, P = .92). Finally, no strength differences were detected between limbs for either muscle group preoperatively (plantar flexors: F1,28 = 1.14, P = .30; dorsiflexors: F1,28 = 0.01, P = .92) or postoperatively (plantar flexors: F1,28 = 2.39, P = .13; dorsiflexors: F1,28 = 0.33, P = .57).

DISCUSSION

Quadriceps and hamstrings weakness are prevalent after ACL injury and subsequent reconstruction. Although clinical observation has suggested weakness also arises in the musculature crossing the hip and ankle joints, few data are available to confirm this contention.8,13 Given that lower extremity muscle weakness may influence dynamic lower extremity control, determining which muscles are weak is imperative so that rehabilitation strategies can be used to target the affected tissues. We sought to confirm and quantify the presence of lower extremity muscle weakness after ACL injury and reconstruction.

Hip Strength

We hypothesized that after ACL injury and reconstruction, weakness would present in the hip flexors and extensors. The absence of greater hip-flexor weakness in the injured than the uninjured limb of the ACL-injured group disagreed with the findings of Karanikas et al,8 who suggested that hip-flexor weakness presents up to 1 year after ACL reconstruction. Differences in strength-assessment technique may contribute to discrepancies between our findings and those reported previously. Karanikas et al8 tested participants in the supine position, whereas we tested our participants in standing position; however, both positions allowed for similar stabilization of the trunk. In addition, they did not normalize hip-flexor strength values to participant body mass8; doing so may eliminate side-to-side differences in hip-flexor strength. However, future research seems necessary to clarify the role of ACL reconstruction in hip-flexor strength. The ACL-injured group did not demonstrate hip-extensor strength differences between limbs over time. The ACL-injured group also demonstrated hip-extensor strength that was similar to that of healthy individuals before and after surgical repair. Furthermore, when the injured and uninjured limbs were considered together, hip-extensor strength was greater postoperatively than preoperatively, which may be because of postoperative rehabilitation. Collectively, these results suggest that hip-extensor strength is not affected by the injury and reconstruction processes. This finding agrees with previous findings indicating no postoperative differences in hip-extensor strength between limbs8,13 or when compared with the limbs of healthy individuals.13

Our participants did not demonstrate hip-abductor weakness, which was unexpected. Previous research in animal models has indicated that the rectus femoris sends heteronymous neural projections to its hip synergists (ie, sartorius).23 Muscles connected heteronymously may project impairments onto one another, suggesting that strength impairments within the rectus femoris could yield similar impairments within the hip abductors. When examining hip-abductor strength after knee surgery, Jaramillo et al12 indicated weakness within this muscle group; however, they tested strength in the immediate postoperative period, and testing was not limited to those receiving ACL reconstruction, making direct comparisons difficult. Nonetheless, our results seem to suggest that neither ACL injury nor surgical reconstruction negatively influences strength within the hip-abductor muscle group.

Our participants did not demonstrate postoperative hip-adductor weakness and actually presented with greater postoperative strength when the injured and uninjured limbs were considered together. The finding of the absence of hip-adductor weakness disagrees with the results of Hiemstra et al,13 who noted hip-adductor strength deficits after ACL reconstruction with semitendinosus-gracilis autograft. Donor site morbidity likely explains the hip-adductor–muscle weakness in that study and likely also accounts for the difference between our results and those of Hiemstra et al.13

Knee Strength

In accordance with previous findings,3,19 the ACL-injured group demonstrated differences between preoperative and postoperative knee-extensor and -flexor strength. Furthermore, the ACL-injured group demonstrated bilateral differences in knee-extensor and -flexor strength. Specifically, when compared with the uninjured limb, the injured leg displayed strength deficits of 33% in the knee extensors and 10% in the knee flexors. Previously reported knee-extensor and -flexor strength deficits vary, ranging from 5% to 40%2–10 and 9% to 27%,2,3,5,8,9,11 respectively. The presence of greater knee-extensor and -flexor weakness in the injured than in the uninjured limb in our participants seems to confirm that current rehabilitation strategies do not fully restore strength by the time that individuals return to activity. Traditional rehabilitation often dictates that individuals are discharged from supervised care between 3 and 4 months after surgery, but our participants received postoperative rehabilitation for an average of 7 months. This longer rehabilitation does not appear to be sufficient time to restore flexor strength. Perhaps longer postoperative rehabilitation programs are necessary to restore strength before an individual returns to activity. Furthermore, return-to-participation decisions may need to include isokinetic knee-extensor and -flexor strength assessments, because the deficits that our participants displayed seem to be quite large for individuals returning to demanding activity.

Rehabilitation beyond 3 to 4 months after surgery may be beneficial, but until the cause of these deficits is known, effectively countering them will be difficult even with extended rehabilitation. Factors such as knee-extensor central activation failure,24 atrophy,25 detraining,5 and incomplete rehabilitation5 have been suggested to contribute to persistent knee-extensor and -flexor weakness after postreconstruction ACL rehabilitation. Data from experimental effusion models and from patients with ACL injury suggest that knee joint trauma may contribute to ongoing weakness.26–28 This arthrogenic muscle inhibition results in the inability to completely contract affected muscles because inhibitory signals are transmitted to the muscle's α-motoneuron pool.29 After ACL injury, the inhibitory stimulus may originate from joint pain,30 damage,31 and effusion.31

As the knee extensors and flexors cross the knee joint, weakness within these muscles may directly alter tibiofemoral biomechanics, possibly contributing to joint degeneration. In fact, knee-extensor weakness is suggested to limit its ability to absorb energy on weight bearing, which precipitates increased articular cartilage loading and thus may yield joint degeneration.32 Furthermore, knee-flexor strength deficits that are present when individuals return to full activity also may be hazardous because the knee flexors restrain anterior tibial translation, a known contributor to ACL injury.33 Given these potentially hazardous consequences of knee-extensor and -flexor weakness, countering the underlying cause of this weakness seems imperative. Researchers studying the removal of artificially induced knee-extensor muscle inhibition have suggested that cryotherapy34 and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation34 may be useful adjuncts to traditional rehabilitation. Furthermore, the use of neuromuscular electrical nerve stimulation has been explored,35,36 but the duration of strength benefits from this treatment remains unknown. Future research into the benefits of each of these treatments within postoperative ACL rehabilitation seems warranted.

The ACL-injured participants had weaker knee extensors and flexors in the injured limb preoperatively than the control group. We also found a trend toward differences in postoperative knee-extensor strength (P = .08, Cohen d = 0.69), indicating knee-extensor weakness in this group may not be sufficiently countered postoperatively when compared with healthy individuals. The results of previous studies in which strength was compared in healthy individuals and those who had undergone ACL reconstruction are conflicting. Konishi and Fukubayashi11 did not establish a difference in knee-flexor torque per unit volume between the injured limb 12 months after ACL reconstruction and the control participants. However, Hiemstra et al5 demonstrated differences in knee-extensor and knee-flexor strength between individuals at an average of 40 months after ACL reconstruction and control participants. The reason for the discrepancies in these findings is unclear, but differences in normalization method (ie, normalizing strength to body mass versus muscle volume), time since reconstruction, and graft type may play roles. The conflicting results suggest the need for future research to clarify the relationship between strength in individuals with ACL reconstruction and strength in healthy people.

Ankle Strength

The ACL-injured group demonstrated greater ankle–plantar-flexor weakness in the injured limb preoperatively than postoperatively and a trend toward greater weakness in the injured than in the uninjured limb preoperatively (P = .06; Cohen d = 0.31). Recently, Karanikas et al8 reported that ankle–plantar-flexor strength was not influenced at any postoperative time point assessed in their study (3–6, 6–9, or 9–12 months postoperatively), suggesting that the restoration of plantar-flexor strength may occur early during rehabilitation. The postoperative improvement in ankle–plantar-flexor strength in our participants agrees with these findings. With the gastrocnemius crossing the knee joint, the preoperative plantar-flexor weakness in our ACL-injured participants may have been a direct consequence of the ACL injury. In addition, the gastrocnemius is connected neurally to the quadriceps,37,38 and altered strength and neuromuscular activity within the quadriceps after ACL injury could potentiate gastrocnemius weakness.37,38 Disuse atrophy of the gastrocnemius may have contributed further to the preoperative weakness demonstrated by our participants.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. Specifically, the range of time that elapsed between ACL injury and preoperative testing was large (15–311 days). In participants tested earlier after injury, pain and swelling may have influenced strength outcomes, whereas participants tested later after surgery may not have been affected by these symptoms. Furthermore, reliability data were not available for our strength measures. However, all strength assessments (preoperative, postoperative, control) were performed by 1 examiner using standardized procedures to minimize variability during testing. Similar procedures have yielded high reliability.39

An additional limitation is that we tested control participants on only 1 occasion, so we cannot be certain that changes in strength were not due to repeat testing. However, we believed including a control group was important because we could not guarantee that the uninjured limb was not affected by the ACL injury and reconstruction processes. The ACL-injured group demonstrated greater strength in the uninjured limb than was seen in the contralateral limb in the control group postoperatively. This difference was not present preoperatively, suggesting that rehabilitation influenced uninjured limb strength. Strength in the uninjured limb changing preoperatively to postoperatively provides a moving target by which to track strength of the injured limb over time. Thus, a more accurate determination of strength gains over time may be made by comparing people with ACL injury and healthy individuals. However, in future studies, researchers also would benefit from including bilateral data on injured individuals to lend insight into strength asymmetries after injury or reconstruction.

CONCLUSIONS

Quadriceps and hamstrings weakness in the injured limb persisted when individuals returned to activity after ACL reconstruction. Given that these muscles directly contribute to safe lower extremity dynamic stability when individuals return to full activity after injury, determining the precise cause of and developing more effective strategies to counter this weakness appears vital. In addition, ankle–plantar-flexor weakness presented in the injured limb preoperatively, but current rehabilitation strategies seemed to effectively counter this weakness after ACL reconstruction. Finally, the hip extensors and adductors were stronger postoperatively, suggesting that current rehabilitation strategies allow for postoperative strength gains within these muscle groups.

Appendix. .

Postoperative Rehabilitation Guidelines for All Participants Undergoing Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

| Exercise |

Week |

||||

| 1a |

2–6b |

7–11 |

12–15 |

16 |

|

| Range of motion | Heel slides | To previous exercises add the following: | Continue previous exercises as necessary | Continue previous exercises as necessary | Continue previous exercises as necessary |

| Active-assistive range of motion (90°–40°) | Bicycle | ||||

| Passive range of motion (40°–0°) | |||||

| Patellar mobilization | |||||

| Flexibility | Hamstrings stretch | Hamstrings stretch | Hamstrings stretch | Hamstrings stretch | Hamstrings stretch |

| Calf stretch | Calf stretch | Calf stretch | Calf stretch | Calf stretch | |

| Progressive resistance exercises | Quadriceps sets | To previous exercises add the following: | To previous exercises add the following: | To previous exercises add the following: | To previous exercises add the following: |

| Straight-leg raise | Hamstrings curls | Eccentric hamstrings | Eccentric hamstrings | Eccentric hamstrings | |

| Hip abduction and adduction | Hip flexion and extension | ||||

| Ankle pumps | Isotonic hip abduction and adduction | ||||

| Knee extension | |||||

| Closed kinetic chain exercises | Standing knee extensions | To previous exercises, add the following: | To previous exercises, add the following: | To previous exercises, add the following: | To previous exercises, add the following: |

| Bilateral mini squats | Standing bilateral ankle platform system | Fitter | Side shuffling | Sport-specific training | |

| Calf raises | Leg press | Walking lunges | Rope jumping | ||

| Stair-climbing machine | Slide board | Plyometrics | |||

| Step ups | Mini trampoline | ||||

| Single-leg squats | Retro treadmill | ||||

| Proprioception and balance | Not applicable | Single-leg balance | Continue previous exercises and progress as necessary | Continue previous exercises and progress as necessary | Continue previous exercises and progress as necessary |

| Wobble board | |||||

| Rebounder | |||||

| Plyoball | |||||

| Grid exercises | |||||

Indicates 0%–25% weight bearing.

Indicates progress to full weight bearing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by research grant number 1 K08 AR05315201A2 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/National Institutes of Health (Dr Palmieri-Smith).

REFERENCES

- 1.Lohmander LS, Ostenberg A, Englund M, Roos H. High prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, pain, and functional limitations in female soccer players twelve years after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(10):3145–3152. doi: 10.1002/art.20589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Jong SN, van Caspel DR, van Haeff MJ, Saris DB. Functional assessment and muscle strength before and after reconstruction of chronic anterior cruciate ligament lesions. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.08.024. 28.e1–28.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasuda K, Ohkoshi Y, Tanabe Y, Kaneda K. Muscle weakness after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using patellar and quadriceps tendons. Bull Hosp Jt Dis Orthop Inst. 1991;51(2):175–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drechsler WI, Cramp MC, Scott OM. Changes in muscle strength and EMG median frequency after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;98(6):613–623. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiemstra LA, Webber S, MacDonald PB, Kriellaars DJ. Contralateral limb strength deficits after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using a hamstring tendon graft. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2007;22(5):543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattacola CG, Perrin DH, Gansneder BM, Gieck JH, Saliba EN, McCue FC., III Strength, functional outcome, and postural stability after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athl Train. 2002;37(3):262–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moisala AS, Jarvela T, Kannus P, Jarvinen M. Muscle strength evaluations after ACL reconstruction. Int J Sports Med. 2007;28(10):868–872. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-964912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karanikas K, Arampatzis A, Bruggemann GP. Motor task and muscle strength followed different adaptation patterns after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;45(1):37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aune AK, Holm I, Risberg MA, Jensen HK, Steen H. Four-strand hamstring tendon autograft compared with patellar tendon-bone autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized study with two-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(6):722–728. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290060901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konishi Y, Ikeda K, Nishino A, Sunaga M, Aihara Y, Fukubayashi T. Relationship between quadriceps femoris muscle volume and muscle torque after anterior cruciate ligament repair. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;17(6):656–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konishi Y, Fukubayashi T. Relationship between muscle volume and muscle torque of the hamstrings after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(1):101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaramillo J, Worrell TW, Ingersoll CD. Hip isometric strength following knee surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;20(3):160–165. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1994.20.3.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiemstra LA, Gofton WT, Kriellaars DJ. Hip strength following hamstring tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15(3):180–182. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000157795.93004.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasegawa S, Kobayashi M, Arai R, Tamaki A, Nakamura T, Moritani T. Effect of early implementation of electrical muscle stimulation to prevent muscle atrophy and weakness in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2011;21(4):622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Besier TF, Lloyd DG, Ackland TR. Muscle activation strategies at the knee during running and cutting maneuvers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(1):119–127. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200301000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schipplein OD, Andriacchi TP. Interaction between active and passive knee stabilizers during level walking. J Orthop Res. 1991;9(1):113–119. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suter E, Herzog W. Does muscle inhibition after knee injury increase the risk of osteoarthritis? Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28(1):15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tegner Y, Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;198:43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keays SL, Bullock-Saxton J, Keays AC, Newcombe P. Muscle strength and function before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using semitendonosus and gracilis. Knee. 2001;8(3):229–234. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0160(01)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbic S, Brouwer B. Test position and hip strength in healthy adults and people with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(4):784–787. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perry J, Easterday CS, Antonelli DJ. Surface versus intramuscular electrodes for electromyography of superficial and deep muscles. Phys Ther. 1981;61(1):7–15. doi: 10.1093/ptj/61.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Academic Press;; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MT, O'Donovan MJ. Organization of hindlimb muscle afferent projections to lumbosacral motoneurons in the chick embryo. J Neurosci. 1991;11(8):2564–2573. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-08-02564.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urbach D, Nebelung W, Becker R, Awiszus F. Effects of reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament on voluntary activation of quadriceps femoris: a prospective twitch interpolation study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(8):1104–1110. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b8.11618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young A. Current issues in arthrogenous inhibition. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52(11):829–834. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.11.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopkins JT, Ingersoll CD, Krause BA, Edwards JE, Cordova ML. Effect of knee joint effusion on quadriceps and soleus motoneuron pool excitability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(1):123–126. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200101000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chmielewski TL, Stackhouse S, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A prospective analysis of incidence and severity of quadriceps inhibition in a consecutive sample of 100 patients with complete acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(5):925–930. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urbach D, Nebelung W, Weiler HT, Awiszus F. Bilateral deficit of voluntary quadriceps muscle activation after unilateral ACL tear. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(12):1691–1696. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199912000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stokes M, Young A. The contribution of reflex inhibition to arthrogenous muscle weakness. Clin Sci (Lond) 1984;67(1):7–14. doi: 10.1042/cs0670007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arvidsson I, Eriksson E, Knutsson E, Arner S. Reduction of pain inhibition on voluntary muscle activation by epidural analgesia. Orthopedics. 1986;9(10):1415–1419. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19861001-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shakespeare DT, Stokes M, Sherman KP, Young A. Reflex inhibition of the quadriceps after meniscectomy: lack of association with pain. Clin Physiol. 1985;5(2):137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1985.tb00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radin EL, Yang KH, Riegger C, Kish VL, O'Connor JJ. Relationship between lower limb dynamics and knee joint pain. J Orthop Res. 1991;9(3):398–405. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeMorat G, Weinhold P, Blackburn T, Chudik S, Garrett W. Aggressive quadriceps loading can induce noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(2):477–483. doi: 10.1177/0363546503258928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hopkins J, Ingersoll CD, Edwards J, Klootwyk TE. Cryotherapy and transcutaneous electric neuromuscular stimulation decrease arthrogenic muscle inhibition of the vastus medialis after knee joint effusion. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):25–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitzgerald GK, Piva SR, Irrgang JJ. A modified neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocol for quadriceps strength training following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(9):492–501. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2003.33.9.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snyder-Mackler L, Delitto A, Stralka SW, Bailey SL. Use of electrical stimulation to enhance recovery of quadriceps femoris muscle force production in patients following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther. 1994;74(10):901–907. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.10.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meunier S, Pierrot-Deseilligny E, Simonetta M. Pattern of monosynaptic heteronymous Ia connections in the human lower limb. Exp Brain Res. 1993;96(3):534–544. doi: 10.1007/BF00234121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pierrot-Deseilligny E, Morin C, Bergego C, Tankov N. Pattern of group I fibre projections from ankle flexor and extensor muscles in man. Exp Brain Res. 1981;42((3–4)):337–350. doi: 10.1007/BF00237499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brosky JA, Jr, Nitz AJ, Malone TR, Caborn DN, Rayens MK. Intrarater reliability of selected clinical outcome measures following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29(1):39–48. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1999.29.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]