Abstract

Context:

Researchers studying work–life balance have examined policy development and implementation to create a family-friendly work environment from an individualistic perspective rather than from a cohort of employees working under the same supervisor.

Objective:

To investigate what factors influence work–life balance within the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I clinical setting from the perspective of an athletic training staff.

Design:

Qualitative study.

Setting:

Web-based management system.

Patients or Other Participants:

Eight athletic trainers (5 men, 3 women; age = 38 ± 7 years) in the NCAA Division I setting.

Data Collection and Analysis:

Participants responded to a series of questions by journaling their thoughts and experiences. We included data-source triangulation, multiple-analyst triangulation, and peer review to establish data credibility. We analyzed the data via a grounded theory approach.

Results:

Three themes emerged from the data. Family-oriented and supportive work environment was described as a workplace that fosters and encourages work–life balance through professionally and personally shared goals. Nonwork outlets included activities, such as exercise and personal hobbies, that provide time away from the role of the athletic trainer. Individualistic strategies reflected that although the athletic training staff must work together and support one another, each staff member must have his or her own personal strategies to manage personal and professional responsibilities.

Conclusions:

The foundation for a successful work environment in the NCAA Division I clinical setting potentially can center on the management style of the supervisor, especially one who promotes teamwork among his or her staff members. Although a family-friendly work environment is necessary for work–life balance, each member of the athletic training staff must have personal strategies in place to fully achieve a balance.

Key Words: quality of life, support network, rejuvenation

Key Points.

Athletic trainers who create a balance between their personal and professional lives must recognize the personal strategies that work best for their work responsibilities and family and personal needs.

A workplace that encourages and accepts a teamwork environment and has a supervisor who advocates for his or her employees; values personal and family time; and promotes a flexible, reasonable workload for each staff member is important for work–life balance.

Many factors influence an individual's perceptions of quality of life, but often the time available for personal interests, obligations, and rejuvenation positively or negatively mediates the overall assessment. The extensive time commitment associated with meeting the job responsibilities for an athletic trainer (AT) often has been cited as a negative aspect of the profession and has been linked to concerns with work–life balance.1–4 Moreover, demanding work schedules, including long hours spent at work, have been connected to job burnout4,5 and job turnover.6 Furthermore, the organizational structure of the workplace, among other factors such as job characteristics, personal values, and sex ideology,7,8 has been identified as a potential proponent of work–life balance for the employee.7–9 More specifically, organizations that have more family-friendly policies in place, such as flextime and on-site child care, can better meet the personal and domestic needs of their employees, reducing the possibility of conflict between those different roles.9

Long work hours are seemingly the major catalyst for students enrolled in athletic training educational programs10,11 and certified ATs to consider a position or career change,4,6 as well as a major precipitating factor leading to burnout and work–life balance concerns.2,4 In studies by Dodge et al11 and Mazerolle et al,10 limited time for family and parenting was a mechanism for many athletic training students to drop out of their undergraduate studies in athletic training to pursue more family-friendly careers. This finding is consistent with the findings of other researchers who have examined ATs employed at the collegiate level and have reported female ATs leave their positions to have more time to meet their family needs.6,12 Recognizing the critical link among work hours, work–life balance, and retention, many athletic training scholars have investigated ways to improve the quality of life for the AT. Time away from the role of the AT has been found to be pivotal in helping promote professional commitment and personal rejuvenation, thus increasing the individual's commitment to his or her organization.13

In an investigation of the practices used by ATs employed within the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I clinical setting, Mazerolle et al2 discovered that coworker support, teamwork, and prioritization of both work and personal responsibilities were most successful in creating time away from the job. Support networks and job sharing among coworkers also have been shown to help the female AT remain in the Division I clinical setting12 because these strategies allow the fulfillment of both professional duties and home-life obligations, including parenting, attending to personal interests, and completing household duties. Establishing a family-friendly work environment through organizational policies (eg, job sharing and flexible work schedules) is a critical link in promoting a balance between the work and life of the employee,9 yet few researchers have examined the organizational infrastructure from a holistic perspective. In other words, researchers have examined policy development and implementation from an individualistic perspective rather than from a cohort of employees working under the same supervisor. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to investigate what factors influence work–life balance within the Division I clinical setting from the perspective of an athletic training staff. Information gathered from this investigation may help other athletic training staffs develop similar policies to promote work–life balance and possibly illustrate ways to help socialize staff members into the workplace, which can help promote work–life balance.

METHODS

Case Study Design

We used a descriptive, single-case study design14,15 to examine the role organizational structure and culture can play in the efforts of an AT working at the Division I clinical setting to find a balance between his or her professional and personal lives. The relevant literature within athletic training is rich,2–6,12 particularly in the Division I clinical setting. However, the data often are presented from an individualistic perspective, yet coworker relationships and supervisor support have been linked to the fulfillment of work–life balance. Gaining the perspective of a group of ATs working within the same athletic training department can highlight shared experiences and also provide insight into the cohesion that can occur among employees. Selecting this type of methodologic design helped us gain a holistic14 evaluation of the real-life experiences of the AT currently working in the Division I setting16 as it pertains to workplace relationships and its effect on retention and quality of life. Although not considered to be a traditional mode of data collection in the health sciences, case study designs have provided educational researchers with quality information about student-to-teacher interactions, programmatic changes, and school dynamics.15 Therefore, this research design could provide valuable insight into the workplace dynamics among administrators, supervisors, coworkers, and coaches. These dynamics and how they affect the quality of life for the AT are a perspective that has not been investigated.

Participant Sampling

As with case study designs and other qualitative methods, our sampling was purposeful14,15,17 and done via convenience, criterion, and snowball sampling.18 We wanted to gain an understanding of the relationships that exist within the athletic training department as they relate to quality of life and retention within the Division I clinical setting; therefore, our defining characteristic for study inclusion was full-time employment within the same athletic training staff at 1 Division I university. We purposely selected a particular university, which we refer to hereafter as ABC University.

One member of ABC University's full-time staff served as the university's liaison and as both the convenience and snowball sample for recruitment of other members of the staff. Before data-collection procedures, the liaison, who also participated in the research study, discussed the research agenda among the staff members to gain their interest in participating and communicated between the researchers and the staff members to aid in recruitment. All full-time members of ABC University's athletic training staff were invited to participate in our study. We excluded any part-time employees, such as intern or graduate assistant ATs, because we viewed their positions as temporary and wanted to gain the perspectives of long-term staff members.

We selected ABC University for 2 reasons: (1) one of their staff members has been involved as a participant with this line of research and has shared her success in work–life balance based largely on her work environment, thus sparking the idea for our study, and (2) the athletic training staff has experienced limited turnover, as determined by the length of employment at ABC University (11 ± 6 years). This is highly unique in the collegiate athletic training arena; therefore, insight from these staff members can be useful in promoting retention, job satisfaction, and work–life balance for the AT. Case study designs need to be bounded by time or by experiences shared by a group of people15,17; in this case, our participants were bounded by their employment at the same university and with similar job responsibilities as a typical collegiate AT and reflected on the day-to-day interactions (time) that influenced their work–life balancing abilities.

Participants

A total of 8 ATs (5 men, 3 women; age = 38 ± 7 years), 1 of whom was the head AT, volunteered to participate. The participants represented all full-time staff members at ABC University. On average, each member had been certified for 16 ± 6 years and had been employed at ABC University for 11 ± 6 years. The Table provides individual data for each AT. Informed consent was implied by completion of the study, and the study was approved by the University of Connecticut–Storrs Institutional Review Board.

Data-Collection Procedures

We developed 2 separate questionnaires based on our study's purpose and the existing literature (Appendixes 1 and 2). Several of our questions had been used by researchers investigating work–life balance in the collegiate setting.2–4 The only difference between the instruments was the role the AT played in the workplace (ie, supervisor versus employee). We divided the instrument into 2 parts: (1) initial demographic information and (2) a series of open-ended questions that investigated the organizational structure, workplace policies, and personal strategies used to promote work–life balance. We shared the questionnaire with the liaison from ABC University to ensure the content was accurate, reflective of the research agenda, and presented clearly to the participant. No changes were made to the document.

Seven of the 8 members of the athletic training staff received an individual e-mail from 1 researcher (A.G.) with the link to the Web-based survey questionnaire, which was accessible via SurveyMonkey.com (SurveyMonkey.com, LLC, Palo Alto, CA). The 1 member of the athletic training staff who did not receive the e-mail had agreed before data collection to complete the interview via telephone; this was done for clarity purposes and to ensure consistency with responses generated via the Web-based questioning. Web-based data collection is growing in popularity with researchers in athletic training,1,2,10 particularly for in-depth interviewing and journaling, because the method circumvents many of the difficulties presented by in-person or telephone interviewing, such as time, cost, and access to research participants.19 Furthermore, our decision to use a journaling method for response was purposeful because it allowed the participant to reflect on his or her responses without having to make a quick response, which would be required during a telephone or in-person interview. Although not all participants may be fluent writers, this method of data collection has provided rich data and was beneficial in recruitment because it allows for increased anonymity and increased time to complete the research process for the participant.19 In the e-mail, each participant was instructed to click on the link to the survey and answer each question by journaling his or her response in the space provided. The questionnaire was linked uniquely to each participant's e-mail address; therefore, they were allowed to save their responses and return to the questionnaire if they needed more time. The average time for completing the questionnaire was 20 minutes.

Data Triangulation

Several basic elements must be incorporated in a qualitative study to enhance its overall quality. Specifically for a case study design, using a purposeful sampling technique and triangulating the data by data source, analyst, or method is important.14,17,18,20 Furthermore, Creswell18 advocated for the use of at least 2 methods to secure data trustworthiness, so we opted to capitalize on data-source triangulation, multiple-analyst triangulation, and peer review. Data-source triangulation was completed by interviewing different stakeholders within the athletic training staff at ABC University, including the entire staff and those in supervisory roles (head and associate ATs). Multiple-analyst triangulation involved 2 researchers (S.M.M. and A.G.) independently evaluating and coding the data to reach a mutual agreement of the findings of our study. The peer review was performed when the data-analysis steps were completed. The peer was a qualitative researcher who had more than 20 years of experience with both qualitative methods and a strong understanding of organizational structure, athletic training, and quality-of-life issues.

Data Analysis

We analyzed the data independently and initially followed both grounded theory and iterative processes outlined by several researchers. Both of us have strong research knowledge regarding work–life balance, retention factors, and qualitative methods.18,20,21 The transcripts, which were cut and pasted into Word 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) documents from the Web site, originally were evaluated in a holistic approach, making very general observations and comments. On subsequent readings, specific incidents and commonalities were labeled to represent their meanings within the transcripts. The research agenda and questions helped guide data analysis by providing structure and purpose to the analysis. After we performed the initial coding procedures, labels were appraised and like units of data were organized into a conceptual model.

RESULTS

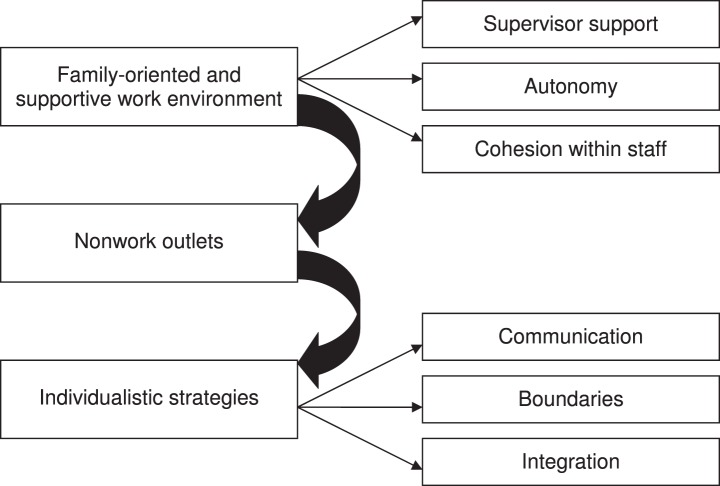

Three themes emerged from the data: family-oriented and supportive work environment, nonwork outlets, and individualistic strategies. The Figure illustrates the relationship of each emergent theme to fulfillment of work–life balance in this particular collegiate setting. We discuss each theme and provide supporting quotations from the participants.

Family-Oriented and Supportive Work Environment

The emergent theme family-oriented and supportive work environment is described as a workplace that fosters and encourages work–life balance through shared goals both professionally and personally. Within this cohort of ATs, the family-oriented environment was established by a combination of factors, including a supervisor (head AT) who promoted and lived a balanced lifestyle; a head AT who also supported autonomy within his sports medicine staff; and a supportive, collective group of ATs who believed in teamwork and job sharing.

Each staff member was instructed to reflect on the role his or her head AT played in work–life balance. Staff member 5 articulated what every member of the athletic training staff believed, “He [our head AT] is the epitome of work–life balancing. He doesn't suggest it but demands it.” Staff member 2 also commented,

I think a great boss and great colleagues influence my ability to have a life outside of the [athletic training] room. . . . He [our head AT] wants everyone to have a life outside of the [athletic training] training room—family, hobbies, etc. This is so important for us to hear as a staff.

The importance of taking time off and away from the duties of an AT was evident throughout the data and supported by each member of the staff. Several times, the head AT mentioned the importance of providing time away from the job to help keep his staff refreshed and committed. He shared this reflection,

Well, I think you have to tell them in the beginning it's okay to take some time off. It's okay to do so . . . I think sometimes [ATs] feel like they have to be there every day. [It is important] to take time off. . . . So, I think what you try to teach them [as a supervisor] is that it is OK, it's OK to take time off, it is OK to attend some family functions. I think it takes the pressure off of them [to hear that encouragement], to kind of keep them balanced also, that they don't have to feel like it is an “all or nothing” type of deal.

Another aspect of the head AT's work–life balance philosophy was his management style, which promoted autonomy among members of his staff particularly related to their fulfillment of work responsibilities and schedule. Staff member 6 said, “[He is] highly supportive on having a life outside of athletics. He lets us make our own decisions and schedule.” Many participants discussed the concept of management style and how having a head AT who was not a micromanager helped the members of the athletic training staff believe they were empowered and able to meet their professional and personal responsibilities. Staff member 7 described the head AT as follows:

He is also not a micromanager. In fact, he wants us to be in charge of whatever area we feel like we excel in. I would say that each of us has an area of medicine or health that we have a sincere interest in, and we are in charge of that duty. We feel empowered not powerless.

In a later entry, staff member 7 shared more information regarding the head AT and the success of their staff:

Where many of us [on our staff] had aspirations of being directors [head ATs] of our own programs, this set up [organizational structure] has given us each a great deal of autonomy, and I would say most of us feel as if we are in charge of our areas . . . take responsibility for them when they aren't going well and are praised for them when they are.

She further illustrated that the head AT continued to preach and live by his own work–life balance philosophy, which allowed her and her coworkers to buy into the concept. She stated,

For the last 20 years, I have heard him say ‘go on, get out of here' and have always heard him preach that having a life outside of athletic training is so important. I guess you hear that enough, you start believing it!

The support and work–life balance philosophy of the head AT was supported by the athletic administration. Staff member 3 articulated this by writing, “They are big supporters of the AT [athletic training] staff. The administration has been a huge reason why we are able to achieve the work–life balance that we seek.”

A cohesive work environment shared by the entire athletic training staff was also a constant point that each participant made. The head AT was the first to highlight this concept of teamwork and support. He stated, “Everybody's got each other's back.” Staff member 3 also reflected,

My coworkers are critical in obtaining work–life balance because we need to have each others' backs. We take turns covering different aspects of our jobs. We try to minimize times when we all have to be there.

Sharing the load or responsibilities was discussed as the major catalyst for this group to enjoy the benefits of a more suitable work schedule. For example, consider the comments of staff member 5 about additional time during the holidays,

We are a team here . . . we all agree that we work hard enough that we need to work smarter not harder. We try [to] cover for each other. For example . . . at Christmas time if I want one more day to be with my family in [a midwestern state], then my men's basketball AT has to be here already; he may cover me. We are a team.

Another staff member, who did not have children, discussed helping out her colleagues who did have children as a means to help them meet their parenting responsibilities. She stated,

We all help each other out a lot. Everyone works really hard, but sometimes we do work together to cover things so that we do not get overworked, which can easily happen. Most of my coworkers have kids, so I usually try and help them cover stuff so they can have more family time.

Staff member 3 was able to summarize the work environment for ABC University:

[We are a successful staff] because everyone has a role and knows their role. No one is trying to get over on anyone else, and there is no backstabbing. We have good people who respect everyone else. We have an excellent leader who promotes a work–life balance.

Nonwork Outlets

All participants discussed the importance of having interests and hobbies that provided stress relief and time away from the role of the collegiate AT as essential in creating a work–life balance. When asked what personal strategies are necessary to promote balance, staff member 3 stated, “Having outside interests is encouraged.” This was confirmed by the head AT, who discussed the importance of having outlets to relieve stress and get away from the daily grind of the job. He said, “I think having outside interests is one [way to create a balance].” He clarified his thoughts regarding time away, “[I] tell them to have other interests than just [athletic training] because I think it keeps you ‘not stale.'” Staff member 1 shared a similar means to find a balance in life, “having outside hobbies/interest[s] such [as] golf, home remodeling, pets.” Exercise and a social support network outside the workplace were also factors discussed as nonwork outlets to provide a balanced lifestyle. Staff member 7 discussed working out as a key ingredient for her:

I find it very important to get some kind of daily exercise. It gives me the time I need to clear my mind and sometimes brainstorm and think through work-related problems I am facing.

Staff member 2 concisely summed up her 3 main strategies to promote a balanced lifestyle: “I like to work out, get good sleep, make friends outside of the workplace.” Having a life beyond the role of an AT was an important aspect in the work–life balance paradigm, but more important for this cohort was the acceptance by the head AT and staff of this necessity. Staff member 5 highlighted this need: “We [the staff members] have a life outside of here [the athletic training room] and we [all] respect that.” Another important aspect of having nonwork outlets is maintaining a separation between the roles. Staff member 1 highlighted this when asked what advice he gives his undergraduate and graduate students: “Spend time with family and friends and do not discuss work when doing so.” The mindset of having nonwork outlets not only was modeled by the head AT and this group of full-time staff ATs but also was encouraged to the graduate assistants and undergraduate students. Staff member 5 wrote,

We really emphasize here that you need a life outside of the [athletic training] room. I always try to make sure my kids are getting away if they don't need to be here. . . . I excuse them for personal events from time to time, as I realize that those things are important.

Finding time away from the athletic training room and the daily grind of athletic health care was an important concept discussed as a means to promote rejuvenation, professional commitment, and work–life balance.

Individualistic Strategies

The emergent theme of individualistic strategies reflects that although the members of the AT staff must work together and support one another, each staff member must have his or her own personal strategies to manage personal and professional responsibilities. This was reflective of marital status; family status; sport and administrative assignments; and personal beliefs, values, and interests. The strategies discussed among this group of ATs included preparation, communication, boundaries, integration, professional commitment, and motivation. Several ATs mentioned being prepared for each day by prioritizing daily responsibilities and using time-management skills to be as efficient as possible within the workplace so they could have more time for family and personal obligations. Staff member 6 shared, “Time management, preparing early to finish on time [helps me stay on task].” Expanding his thoughts, he said, “Time management and scheduling treatments/rehab[ilitation]s around my schedule to maximize time at home and with family.” The use of a to-do list for the day also was mentioned as a way to establish a balance. The head AT shared, “I think it's important to have a priority list which you have planned that week.” Another factor helpful in creating a balanced lifestyle for this cohort was communication, particularly with family and personal needs. Staff member 6 was frank regarding making the time needed. He stated, “Make your athletes adhere to YOUR schedule, not theirs. Communicate your personal needs to staff and coaches.” In a similar sentiment regarding schedules and patient care, staff member 1 noted,

While coaches do not agree, athletics are not life or death. Don't kill yourself trying to take care of an athlete 24/7. Sometimes, less is more; therefore, keep a balance between your work life and your personal life.

The head AT discussed the importance of open communication among staff members to help promote balance by creating a job-sharing environment. He stated, “It's about how can they communicate. I think our communication is very unique also with our monthly meetings and it's an open forum [for schedule discussions].”

Another strategy, integration, was mentioned by staff member 7 as a means to spend more time with her children or to meet a conflict in scheduling, such as with day care or her spouse. She shared,

My kids are old enough now to come to the [athletic training] room regularly and “help.” He [my head AT] sees my kids as added value, not more baggage. It is a guarantee that while my hours are flexible, I pack in nothing but quality when I am there and continue to take care of business after hours as well. I never feel like I [am] shortchanging anyone.

Staff member 7 also discussed the importance of mentorship as a means to help her promote a balanced lifestyle and to “pay it forward.” In addition, it was a means to maintain her professional commitment and motivation. She discussed,

I always thought it was important for my AT [athletic training] students to see me interact with my kids so that they understand that you can have both. The first 10 years of being in AT [athletic training], I never saw anybody with kids in the [athletic training] room. . . . I also think it is important to be a good example for how to lead a healthy lifestyle. Eating well and exercising are important to the health and wellness of my family and workplace. . . . I think this way of life is contagious, and my students often take up some fitness program to stay well too. Again, it gives them a strategy they can use later on that will help them deal with issues of burnout.

Not all members of the athletic training staff capitalized on the same life-balancing strategies, but all discussed their personal ways to find a balance. They were quick to point out the importance of having interests beyond their roles as ATs; however, other methods previously presented were also necessary to help them achieve that balance.

DISCUSSION

The workplace environment and established organizational policies, particularly administrative and supervisor support, flexible work schedules, and support networks, have been identified as helpful in promoting work–life balance for the working professional, including the AT. Despite this knowledge, many investigators have focused on the perspective of the individual employee rather than that of a cohort of working professionals who share the same job roles and responsibilities. Our results parallel those of other researchers and illustrate the importance of teamwork, support networks, and the role the supervisor can play in fulfilling work–life balance.1,2,6 The foundation for a successful work environment at ABC University, which boosts job satisfaction, retention, and work–life balance, certainly was influenced by the management style of the supervisor, who modeled the behaviors he expected of his staff members. Moreover, the members of the athletic training staff were successful because they felt rejuvenated, enjoyed their jobs, and believed they were supported at all levels of the administration. However, the data also highlight the need for individualistic plans for fulfillment of work–life balance, outside interests, and hobbies to promote a balanced lifestyle. Overall, a workplace environment that can provide ATs autonomy to control their work schedules and attend to their personal and family matters is one that also supports job satisfaction and retention. Moreover, the professional autonomy that the head AT provided likely influenced the long-term tenure of the athletic training staff members at ABC University.

Family-Oriented and Supportive Work Environment

As in previous research, support from supervisors was found to be an important factor facilitating work–life balance for this group of ATs.1,2 Moreover, it appeared to positively influence the decision for the AT to remain in his or her work environment because he or she can fulfill all professional and personal responsibilities. Supervisors, managers, and organizational leaders can play the role of gatekeeper for upholding work and life initiatives that the organization establishes and can be the people responsible for creating and implementing policies to help the staff members meet personal and family needs. The head AT at ABC University valued not only the contributions of his staff members to the workplace but also their responsibilities to their families. He demonstrated this appreciation by giving them the flexibility and autonomy to develop their own work schedules to meet their professional and personal responsibilities. Flexibility in work schedules has been a popular organizational policy afforded to working professionals,9 particularly women, to meet both work and home responsibilities. The concept allows them to address multiple roles within the day and, in the case of unplanned events, enables them to manage such events without stress. The staff members' experiences at ABC University were positive largely because of their supervisor's work–life balance philosophy. Although this feature has been deemed important in the Division I clinical setting,2 it plausibly may not be the norm for all Division I ATs. Recently, Goodman et al6 found workplace conflicts (ie, inability to achieve work–life balance, lack of perceived support from supervisors) to be major attrition factors among Division I female ATs.

Female coaches at the Division I level have discussed autonomy in the workplace, similar to what was provided to the ATs at ABC University, as indispensable to their abilities to be good parents and successful coaches despite the 40-hour or longer workweek.8 Essentially, the autonomy over one's work schedule can help the employee feel empowered and in control when addressing the dynamic nature of both family and athletic schedules, because both can have unforeseen changes and are demanding at times. Professional autonomy over both job performance and certain scheduling aspects also has been documented as an important retention factor for the Division I AT.6

Social support, especially coworker support, also has been shown to be a factor in retention6 for the AT in addition to an effective way to achieve work–life balance.22 As mentioned, flexibility with work schedules is an important policy to help the working parent,9 and collegial support can help foster flexibility with work schedules. As in previous research,2,23 the participants discussed helping their peers when a family emergency arose or when practice times changed and a colleague had a previous engagement at home. Coworker support should not be exclusive to the working parent but should be available to any AT who is trying to manage the long work hours associated with athletic training in the collegiate setting.3,5 Employees who believe they are supported by their peers and supervisors are more committed to their positions,9 which is something that could strongly influence patient care. Furthermore, employees who believe they are supported by their organizations are more satisfied both personally and professionally, which is an important retention factor.9 This was certainly the case for this athletic training staff because the average time of employment at ABC University was 11 ± 6 years.

Nonwork Outlets

Time away from the role of AT is important not only to fulfill work–life balance but also to help promote professional commitment. Common recommendations for allowing time away from the role include personal hobbies, leisure time, and exercise,1,2,13 which were suggestions made by our participants. Interestingly, the time spent on personal outside interests rejuvenates the AT, allowing ATs to feel more professionally committed and ready to tackle their responsibilities at work and home. Although time away from the role of the AT has been discussed in previous research,13,22 this group of ATs appeared to stress the importance of exercise and healthy lifestyle practices as means to achieve and promote life balance. Exercise not only benefited them physically but also provided a much-needed mental break from their roles as ATs, parents, and spouses. Athletic trainers are notorious for working long hours and putting other people's needs before their own. Therefore, taking time (eg, before work, during lunch, between treatments or practices) to incorporate an adequate workout to relieve stress from the day is important to them. Recent data have indicated that although ATs are active, they do not meet the professional recommendations set forth by the American College of Sports Medicine to exercise for 30 minutes at least 5 days per week.24 Most importantly, ATs need to practice and promote healthy exercise and eating habits not only to maintain or improve their own quality of life but also to display another positive influence for the athletic training students and graduate assistant ATs they mentor.

A healthy lifestyle also encompasses social support networks, which include friends and family who are separate from the workplace. Although teamwork within the workplace is important for work–life balance, having outlets outside of the workplace is necessary too because these outlets allow the AT to clear his or her mind and find a respite from job stressors. The concept of separation is also an important personal work–life balance strategy that the AT uses.2,22 Creating clear lines between the responsibilities can help the AT avoid thinking about or addressing the stresses of the job while spending time with friends or family. By separating them, the AT can enjoy the time spent in each domain without feeling overwhelmed or consumed by the other. Furthermore, support received from the AT's social support group also will help him or her have a sense of work–life balance; spousal and family support often has been cited as beneficial in achieving work–life balance at the collegiate setting.2,6,12

Individualistic Strategies

Fulfillment of work–life balance appears to result from a combination of a cohesive, family-friendly work environment that includes a supportive supervisor and personal strategies to address individual family and personal needs. The members of the athletic training staff at ABC University quickly pointed out that they worked in a very supportive, family-oriented environment, which was the foundation of their success, but recognized that each staff member had his or her own outside interests and family needs. work–life imbalance has been shown to affect ATs regardless of their marital and family status.3 Moreover, personal values and interests have been found to mediate the conflicts experienced between work and home life,7,8 thus highlighting the need for each individual to have a personalized plan for fulfilling his or her roles at work and home and for having time away from each role. Corroborating previous research, this cohort of ATs used time-management skills; established professional boundaries; and, when necessary, capitalized on integration to help meet child care responsibilities.1,2,22 Creating a work schedule that establishes boundaries, such as set treatment times, times for telephone calls and texts, and time to complete administrative paperwork, can help the AT maintain a reasonable workload that limits interference and conflicts with personal and family responsibilities. Professional boundaries also provide the AT with ownership over his or her job responsibilities and work schedule, a previously identified factor in fulfillment of work–life balance.2

Creating a family-friendly work environment begins with developing policies that help the working parent adapt to and meet the needs of both his or her workplace and parenting roles. Integration is a policy that has emerged within the athletic training clinical setting and can be helpful.2,12,23 Although the concepts appear to favor the working parent, they have implications for the AT regardless of family status because periods of downtime during the day often can be used for personal activities, such as working out, running errands, or meeting a friend or family member for lunch. The autonomy afforded to the members of ABC University's athletic training staff by the head AT allowed them to capitalize on this notion of integration during the workday, thus contributing positively to their work–life balance.

ABC University's head AT served as a strong role model for his staff not only by supporting work–life balance but also by following his own policies. The concept of role modeling also was mentioned by a female staff member as important in helping her students develop professionally. Although never linked to retention or work–life balance, mentorship anecdotally could be a strong strategy used to promote healthy work and lifestyle habits among young ATs. Mentorship has been cited as a critical socializing agent to help young professionals develop the skills, values, and attitudes associated with their work roles25,26; therefore, we could hypothesize that promoting a work–life balance culture can be learned through mentorship. Mentorship and positive role modeling was found to help mediate the occurrence of sex bias in the workplace because appropriate professional behaviors and management strategies can be demonstrated, providing a realistic, teachable moment27 that reinforces suitable actions when addressing conflict. Therefore, it is plausible to reason that if a young AT can witness successful work–life balance strategies at both the personal and organizational levels, he or she will continue to promote and use them throughout his or her career. For example, consider the female staff member who discussed modeling healthy behaviors and managing her family and work responsibilities. She can educate her students about the lifestyle associated with the collegiate AT, which often includes working 40 or more hours per week while successfully balancing 2 children, a spouse, a home, and a full workload. She personally uses the strategy of integration to help meet home and personal obligations that include being home for dinner each night despite still having more work responsibilities (eg, responding to e-mails, telephone calls, and other business) to complete at night while at home with her family. Professional modeling, especially for female students and young professionals, may be an important key to helping retain ATs at the collegiate level while they attempt to find a balance professionally and personally.

Mentoring and role modeling are components of the professional socialization process for the working employee and help introduce the roles and expectations associated with his or her role.28 Our results plausibly highlight the success of a more informal socialization process, which offers more on-the-job learning rather than a structured orientation to workplace expectations. The members of the athletic training staff developed an appreciation of the workplace environment, which offered flexibility with work schedules, teamwork, and supervisor support. This environment effectively helped the members of the athletic training staff achieve work–life balance, as indicated by their responses to the open-ended questions.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study has limitations. The data presented reflect the opinions and experiences of only 1 sports medicine staff. Although our data-collection procedures were purposeful to aid in answering the research questions and steps were taken to ensure data credibility, the data represent only 1 athletic training department among several hundred. Future researchers should try to gain the perspectives of other athletic training departments, including those that are not at the Division I level. We capitalized on Web-based journaling as a means to collect data instead of using telephone or in-person interviews. Although this method is trustworthy and increasingly popular, we could not follow up on the participants' responses to questions to gain additional information or clarify responses. Researchers have used this form of data collection, and we are confident in the clarity of the questions posed; in future inquiries, researchers can employ other methods to collect data. In future investigations, researchers must take a closer look at the role of the supervisor and the fulfillment of work–life balance. This factor, among several, appeared to be the most important for this cohort of ATs to enjoy a balanced lifestyle despite working in a demanding environment. Moreover, future researchers may evaluate the role of effective socialization into the workplace as a means to promote work–life balance. Informal and formal socialization processes have been found to mediate an AT's learning of on-the-job skills, values, and expectations but have not been evaluated in the role of fulfilling work–life balance.

CONCLUSIONS

Work–life balance has become a central focus for working Americans,29 including ATs, who often work longer days and more than 40 hours per week.2,3 Athletic trainers who create a balance between their personal and professional lives must recognize the personal strategies that will work best for their family needs (eg, a daily to-do list); must have strong communication among coworkers, supervisors, and spouses; and must create time away from the workplace to rejuvenate. Also important to the fulfillment of work–life balance is to find a workplace that encourages and accepts a teamwork environment and has a supervisor who is an advocate for his or her employees in terms of work-related responsibilities (ie, pay, autonomy); values personal and family time; and is willing to promote a flexible, reasonable workload for each staff member regardless of his or her marital or family status. The results generated in our study and by other researchers in the Division I clinical setting show that work–life balance is plausible largely because of preparation, boundaries, and the development of support networks in and out of the workplace.

Figure. .

Factors influencing work–life balance at the organizational level.

Table. .

Individual Demographic Data of the Sports Medicine Staff at ABC University

| Name |

Sex |

Age, y |

Experience, y |

Time at University, y |

Marital Status |

Family |

Travela |

| Supervisor 1 | Male | 47 | 25 | 15 | Married | 2 children | Yes |

| Staff 1 | Male | 39 | 17 | 15 | Single | No | Yes |

| Staff 2 | Female | 30 | 7 | 5 | Significant other | No | Yes |

| Staff 3 | Male | 46 | 21 | 15 | Married | No | Yes |

| Staff 4 | Male | 39 | 17 | 9 | Married | 2 children | Yes |

| Staff 5 | Female | 32 | 11 | 11 | Married | 1 child | Yes |

| Staff 6 | Male | 31 | 9 | 1 | Married | 1 child | Yes |

| Staff 7 | Female | 41 | 19 | 14 | Married | 2 children | Yes |

Indicates travel associated with the full-time position.

Appendix 1. .

Staff Member Questionnairea

| 1. Can you describe your work place environment as it pertains to your quality of life? |

| 2. What factors influence work–life balancing for you? |

| 3. What personal strategies do you use to promote a balance? |

| 4. What strategies do you rely upon to help the ATs you oversee find a balance? |

| 5. Describe the role your co-workers play in life balancing in your current position? |

| 6. What do you enjoy most about your current position? |

| 7. What potential obstacles/challenges do you come across in your current position and how do you negotiate them? |

| 8. What is your supervisor's philosophy regarding work–life balancing? |

| 9. Describe your administration's support of the athletic training staff. |

| 10. Describe your working relationship with your coaches. |

| 11. What do you do to stay professionally motivated? |

Appendix 2. .

Supervisor Questionnairea

| 1. What is your personal work–life balancing philosophy? |

| 2. What factors influence work–life balancing for you? |

| 3. What strategies do you use personally to promote a balanced life? |

| 4. What strategies do you rely upon to help your staff find a balance? |

| 5. How do you think your staff would describe the working environment as it currently stands? |

| 6. What do you enjoy most about your current position? |

| 7. What potential obstacles/challenges do you come across in your current position and how do you negotiate them? |

| 8. What is your supervisor's philosophy regarding work–life balancing? |

| 9. Describe your administration's support of the athletic training staff. |

| 10. Describe your working relationship with the coaches you work with. |

| 11. What do you do to stay professionally motivated? |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the athletic training staff at ABC University for their eagerness, willingness, and support on this research project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pitney WA, Mazerolle SM, Pagnotta KD. Work-family conflict among athletic trainers in the secondary school setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):185–193. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Pagnotta KD. Assessing strategies to manage work and life balance of certified athletic trainers working in the Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):194–205. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in national collegiate athletic association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):513–522. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ, Burton L. Work-family conflict, part II: job and life satisfaction in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):505–512. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitney WA. Organizational influences and quality-of-life issues during the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman A, Mensch JM, Jay M, French KE, Mitchell MF, Fritz SL. Retention and attrition factors for female certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting. J Athl Train. 2010;45(3):287–298. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon MA, Bruening JE. Work-family conflict in coaching I: a top-down perspective. J Sport Manag. 2007;21(3):377–406. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon MA, Bruening JE. Perspectives on work-family conflict in sport: an integrated approach. Sport Manag Rev. 2005;8(3):227–253. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon MA, Sagas M. The relationship between organizational support, work-family conflict, and the job-life satisfaction of university coaches. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2007;78(3):236–247. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2007.10599421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazerolle SM, Gavin KE, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Burton L. Undergraduate athletic training students' influences on career decisions after graduation. J Athl Train. 2012;47(6):679–693. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.5.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodge TM, Mitchell MF, Mensch JM. Student retention in athletic training education programs. J Athl Train. 2009;44(2):197–207. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. ATs with children: finding balance in the collegiate practice setting. Int J Athl Ther Today. 2011;16(3):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitney WA. A qualitative examination of professional role commitment among athletic trainers working in the secondary school setting. J Athl Train. 2010;45(2):198–204. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baxter P, Jack S. Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual Rep. 2008;13(4):544–549. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merriam SB. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1998. pp. 44–71. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;; 2003. pp. 19–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amis J. The art of interviewing for case study research. In: Andrews DL, Mason DS, Silk ML, editors. Qualitative Methods in Sports Studies. Oxford, UK: Berg Publishers;; 2005. pp. 104–138. In. eds. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;; 1998. pp. 201–202. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meho LI. E-mail interviewing in qualitative research: a methodological discussion. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 2006;57(10):1284–1295. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. pp. 176–177. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage;; 1990. pp. 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Goodman A. Strategies for athletic trainers to find a balanced lifestyle across clinical settings. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2012;17(3):7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE. Work-family conflict, part II: how athletic trainers can ease it. Athl Ther Today. 2006;11(6):47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groth JJ, Ayers SF, Miller MG, Arbogast WD. Self-reported health and fitness habits of certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(6):617–623. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitney WA, Ilsley P, Rintala J. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Division I context. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitney WA, Ehlers GG, Walker S. A descriptive study of athletic training students' perceptions of effective mentoring roles. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract. 2006;4(2):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazerolle SM, Borland JF, Burton LJ. The professional socialization of college female athletic trainers: navigating experiences of gender bias. J Athl Train. 2012;47(6):694–703. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.6.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitney WA. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in high school settings: a grounded theory investigation. J Athl Train. 2002;37(3):286–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams JC, Boushey H. Center for American Progress, Center for WorkLife Law. The three faces of work-family conflict: the poor, the professionals, and the missing middle. 2011 http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2010/01/pdf/threefaces.pdf. Accessed July 15. [Google Scholar]