Abstract

Dysfunctional telomeres limit cellular proliferative capacity by activating the p53-p21– and p16INK4a-Rb–dependent DNA damage responses (DDRs). The p16INK4a tumor suppressor accumulates in aging tissues, is a biomarker for cellular senescence, and limits stem cell function in vivo. While the activation of a p53-dependent DDR by dysfunctional telomeres has been well documented in human cells and mouse models, the role for p16INK4a in response to telomere dysfunction remains unclear. Here, we generated protection of telomeres 1b p16–/– mice (Pot1bΔ/Δ;p16–/–) to address the function of p16INK4a in the setting of telomere dysfunction in vivo. We found that deletion of p16INK4a accelerated organ impairment and observed functional defects in highly proliferative organs, including the hematopoietic system, small intestine, and testes. Pot1bΔ/Δ;p16–/– hematopoietic cells exhibited increased telomere loss, increased chromosomal fusions, and telomere replication defects. p16INK4a deletion enhanced the activation of the ATR-dependent DDR in Pot1bΔ/Δ hematopoietic cells, leading to p53 stabilization, increased p21-dependent cell cycle arrest, and elevated p53-dependent apoptosis. In contrast to p16INK4a, deletion of p21 did not activate ATR, rescued proliferative defects in Pot1bΔ/Δ hematopoietic cells, and significantly increased organismal lifespan. Our results provide experimental evidence that p16INK4a exerts protective functions in proliferative cells bearing dysfunctional telomeres.

Introduction

Telomeres, protein-DNA complexes that cap the ends of chromosomes, play important roles in preventing the activation of DNA damage checkpoints that induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (1). Immediately after DNA replication, leading-strand telomeres are blunt ended, while lagging-strand telomeres possess a 3′ single-stranded (ss) TTAGGG overhang due to the inability of DNA polymerase α to completely replicate the very ends of the lagging-strand telomeres. In somatic cells, this “end replication problem” results in progressive telomere attrition, leading to telomere dysfunction and the activation of a potent DNA damage response (DDR) that are deleterious to cellular homeostasis. Stem and progenitor cells solve this problem by expressing telomerase, a specialized ribonucleoprotein complex that includes an RNA template (termed TERC) and a reverse transcriptase catalytic subunit (TERT), both essential for telomere elongation. In addition to telomerase, maintenance of telomere function requires the shelterin complex, a set of six proteins required to protect telomeres from inappropriately activating DNA damage checkpoints (2, 3). Three sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins are recruited to chromosomal ends: the duplex telomere–binding proteins TRF1 and TRF2 and the ss telomere DNA–binding protein protection of telomere 1 (POT1). POT1 forms a heterodimer with TPP1, and in turn, TPP1 tethers POT1 to TRF1 and TRF2 through TIN2. Dysfunctional telomeres arising from mutations in telomerase or TIN2 initiate proliferative defects in stem cells, resulting in the onset of human BM failure diseases including dyskeratosis congenita, aplastic anemia, and myelodysplastic syndromes (4–7).

The shelterin complex functions to prevent activation of the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex, which senses dysfunctional telomeres as double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) to activate the ATM protein kinase (8, 9). In addition, localization of the ss DNA–binding protein RPA to dysfunctional telomeres in turn recruits ATR, resulting in the phosphorylation of downstream kinases including CHK1 (10, 11). Mammalian telomeres possess distinct DDR repression mechanisms, with TRF2 required to block ATM-dependent damage signaling, while POT1 prevents the activation of ATR at telomeres (8, 9, 12–16). The mouse genome encodes two POT1 proteins, POT1a and POT1b, each with distinct protective functions at telomeres (17–19). Both POT1a and POT1b repress the ATR-dependent DDR at telomeres, while POT1b is also required to block nuclease access to the telomeric 5′ C-strand to orchestrate the formation of newly synthesized ss telomeric G-overhangs (13, 16, 20–22).

Shelterin is also required to prevent the aberrant repair of dysfunctional telomeres. Telomeres undergo end-to-end fusions via the classic nonhomologous end-joining (C-NHEJ) pathway in the absence of TRF2, while telomeres devoid of TPP1-POT1a/b are repaired by the alternative-NHEJ (A-NHEJ) pathway (23). Removal of shelterin components or progressive telomere attrition results in telomere dysfunction, and in this setting the tumor suppressor p53 initiates robust checkpoint responses. Activation of ATM/ATR by dysfunctional telomeres stimulates p53 and induces its downstream target, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN1A/ p21WAF1/CIP1 (p21), leading to G1 cell cycle arrest (24–26). In mouse models, activation of this cell cycle arrest/cellular senescence program potently suppresses tumor initiation and progression in vivo (27, 28). Similarly, telomere dysfunction due to the deletion of Pot1b in primitive murine hematopoietic cells initiates a p53-dependent apoptotic response that compromises cellular proliferation (29, 30). These studies highlight the importance of p53 status in dictating cellular responses to telomere dysfunction, which involve either entry into p53-dependent apoptosis or cellular senescence with progression to proliferative organ failure, or increased clonal selection of genomically aberrant cells and acquisition of an unstable genome, leading to the onset of malignancy (31–33).

While a robust link exists between telomere dysfunction and the activation of a p53-dependent DDR to repress aberrant cellular proliferation, how dysfunctional telomeres impact the Rb pathway remains unclear. In human cells, critically shortened telomeres have been associated with the induction of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a, resulting in the disruption of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 binding to D-type cyclins, Rb hypophosphorylation, and the activation of Rb checkpoint functions to elicit cellular senescence (34, 35). In mice, activation of p16INK4a in response to age-related cellular stresses results in the progressive impairment of some self-renewing tissues including stem cells, while deletion of p16INK4a enhances cellular survival as well as self-renewal potential (36–39). These results suggest that one mechanism underlying p16INK4a-mediated cellular impairments in hematopoietic stem cells might be due to p16INK4a upregulation by chronic DNA damage resulting from progressive telomere dysfunction that limits stem cell self-renewal capacity (40). In addition, accelerated clearance of p16INK4a-positive senescent cells in various mouse tissues reduces age-related pathologies, suggesting that the accumulation of p16INK4a-positive cells directly contributes to tissue degeneration (41). Disruption of the INK4a locus (encoding both p16INK4a and p19Arf) in the presence of critically shortened telomeres results in reduced tumor incidence in a p53-dependent manner without grossly affecting organ degenerative phenotypes, suggesting that p16INK4a and p19Arf are not required to activate DNA damage checkpoints in the setting of telomere attrition (42). However, since p16INK4a was deleted together with p19Arf in this experimental system, the in vivo impact of p16INK4a by itself in the setting of telomere dysfunction remains unknown.

In this study, we generated Pot1bΔ/Δ;p16INK4a–/– mice to address the in vivo impact of deleting p16INK4a in the setting of telomere uncapping due to POT1b deletion. Surprisingly, we found that deletion of p16INK4a significantly modulated the effects of telomere dysfunction in several tissues including the hematopoietic system, small intestine, and testes. These data suggest an unanticipated role for p16INK4a in the ATR-dependent DDR resulting from telomere dysfunction due to Pot1b deletion.

Results

Loss of p16INK4a exacerbates cellular proliferative defects observed in Pot1bΔ/Δ mice.

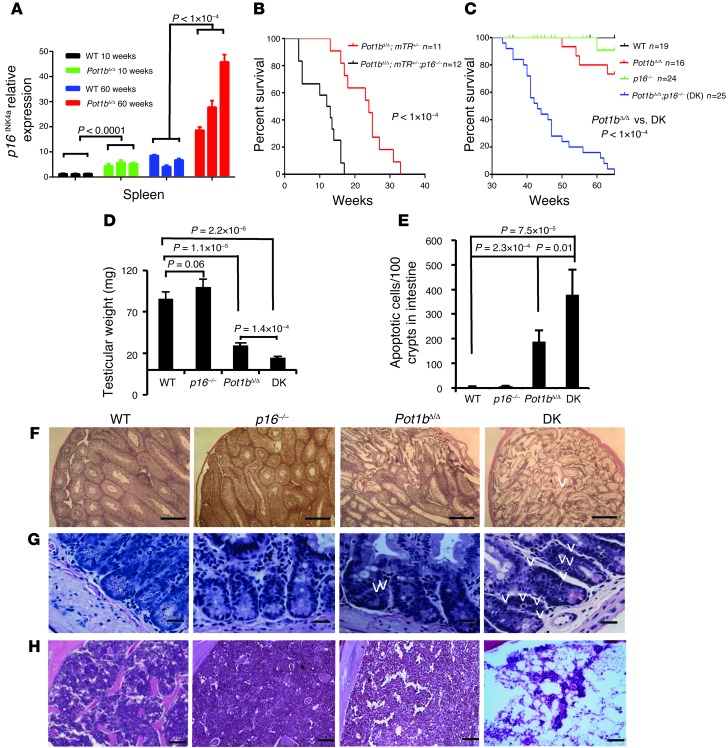

We have previously shown that deletion of the shelterin component POT1b in the setting of telomerase haploinsufficiency (Pot1bΔ/Δ;mTerc+/– mice) results in rapid telomere shortening, initiating a DDR that culminates in the proliferative failure of primitive hematopoietic cells (29, 30). In mice, p16INK4a expression increased with advancing age, correlating with a decline in the replicative capacity of several self-renewing compartments (36–39). In addition, p16INK4a expression was induced in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) possessing dysfunctional telomeres (43). We therefore postulated that p16INK4a expression might be induced in proliferating tissues by dysfunctional telomeres due to the absence of Pot1b. To test this hypothesis, we used real-time PCR analysis to monitor p16INK4a expression in spleens from 10- and 60-week-old WT and Pot1bΔ/Δ mice. Compared with their age-matched WT littermates, p16INK4a expression increased approximately 5-fold in 10-week-old Pot1bΔ/Δ mice (5.29 ± 1.13 for Pot1bΔ/Δ vs. 1.25 ± 0.16 for WT, P < 1.0 × 10–4) (Figure 1A). A similar increase in p16INK4a expression was observed in 60-week-old Pot1bΔ/Δ spleens (30.76 ± 12.12 for Pot1bΔ/Δ vs. 6.47 ± 2.00 WT, P < 1.0 × 10–4) (Figure 1A). Since the replicative capacity of certain cellular compartments in aged mice significantly improves when p16INK4a expression is abrogated (36–39), we asked whether the elimination of p16INK4a expression in Pot1bΔ/Δ;mTerc+/– mice could ameliorate the observed proliferative defects in the hematopoietic system. We crossed p16INK4a–/– (termed p16–/–) mice with Pot1bΔ/Δ;mTerc+/– mice to generate Pot1bΔ/Δ;mTerc+/–;p16–/– mice. To our surprise, these mice succumbed to fatal BM failure at an even earlier age than the Pot1bΔ/Δ;mTerc+/– mice: the median survival time for Pot1bΔ/Δ;mTerc+/–;p16–/– mice was 12.5 weeks compared with 24 weeks for Pot1bΔ/Δ;mTR+/– mice (Figure 1B). Deletion of p16INK4a also significantly shortened the lifespan of Pot1bΔ/Δ mice with normal telomerase levels (median age of ~65 weeks for Pot1bΔ/Δ mice compared with ~43 weeks for Pot1bΔ/Δ;p16–/– double-knockout [DK] animals) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Loss of p16INK4a accelerates premature aging phenotypes in Pot1bΔ/Δ;mTR+/– and Pot1bΔ/Δ mice.

(A) Real-time PCR quantification of p16INK4a mRNA expression levels in young (10-week-old) and old (60-week-old) WT and Pot1b-null mouse spleens. Three individual samples were analyzed per genotype, and each experiment was repeated in triplicate. Error bars represent the SEM. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of Pot1bΔ/Δ;mTR+/– and Pot1bΔ/Δ;mTR+/;p16–/– mice. A log-rank test was used to calculate statistical significance. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing the survival percentage of mice of the indicated genotypes as a function of age. All groups of mice were monitored for a minimum of 65 weeks and sacrificed when moribund. A log-rank test was used to calculate statistical significance. (D) Testicular weights from mice of the indicated genotypes. Each genotype includes testes from a minimum of 4 mice. Error bars represent the SEM. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. (E) Quantification of the number of apoptotic cells in basal crypts of small intestines isolated from WT, p16–/–, Pot1bΔ/Δ, and DK mice. Error bars represent the SEM. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. Representative H&E-stained histological sections of testes (F), small intestine (G), and BM (H) isolated from 40- to 45-week-old mice of the indicated genotypes. Original magnification, ×4 for testes and ×40 for intestines and BM. Arrowheads point to apoptotic intestinal cells.

Examination of highly proliferative organs revealed that compared with 40- to 45-week-old WT animals, both the size and weight of age-matched DK testes were significantly reduced, although this weight loss was not observed in the testes of p16INK4a mice. Further analysis showed that although the weights of Pot1b-null testes were also decreased, DK testes experienced even greater weight reduction (Figure 1D and Supplemental Figure 1A; supplemental material available online with this article; doi: 10.1172/JCI69574DS1). Histological analysis revealed that these testes displayed a complete absence of spermatogenesis in all seminiferous tubules examined, while in Pot1b-null testes, 30%–40% of tubules still contained germ cells at various developmental stages (Figure 1F). H&E and TUNEL staining revealed that compared with WT mice, both Pot1bΔ/Δ and DK mice had significant increases in the number of apoptotic cells in the intestinal crypt epithelia. However, DK mice displayed a 2-fold increase in apoptotic cells compared with Pot1bΔ/Δ mice (Figure 1, E and G, and Supplemental Figure 1B). Analysis of peripheral bleeds revealed that while all 40- to 45-week-old WT and p16–/– mice displayed normal wbc counts, age-matched DK mice displayed very low wbc counts, significantly lower than those observed for Pot1bΔ/Δ mice (1.6 ± 0.5 × 103/μl for DK vs. 7.5 ± 0.5 × 103/μl for Pot1bΔ/Δ mice) (Supplemental Figure 1C). Histological examination of femurs revealed that at 40 to 45 weeks of age, both WT and Pot1b-null BM appeared largely normal, with trilineage hematopoiesis (Figure 1H). In contrast, all DK mice examined exhibited increased BM hypocellularity, with 3 of 5 mice progressing to complete BM failure (Figure 1H). Taken together, these results suggest that in the absence of Pot1b, the loss of p16INK4a potently exacerbated proliferative defects in tissues with high rates of cellular turnover, likely contributing to increased mortality.

Increased proliferative defects in DK hematopoietic cells.

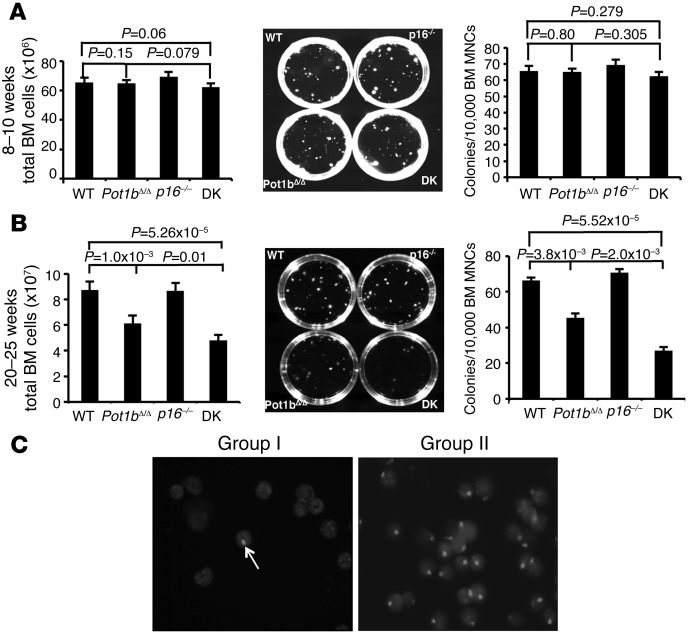

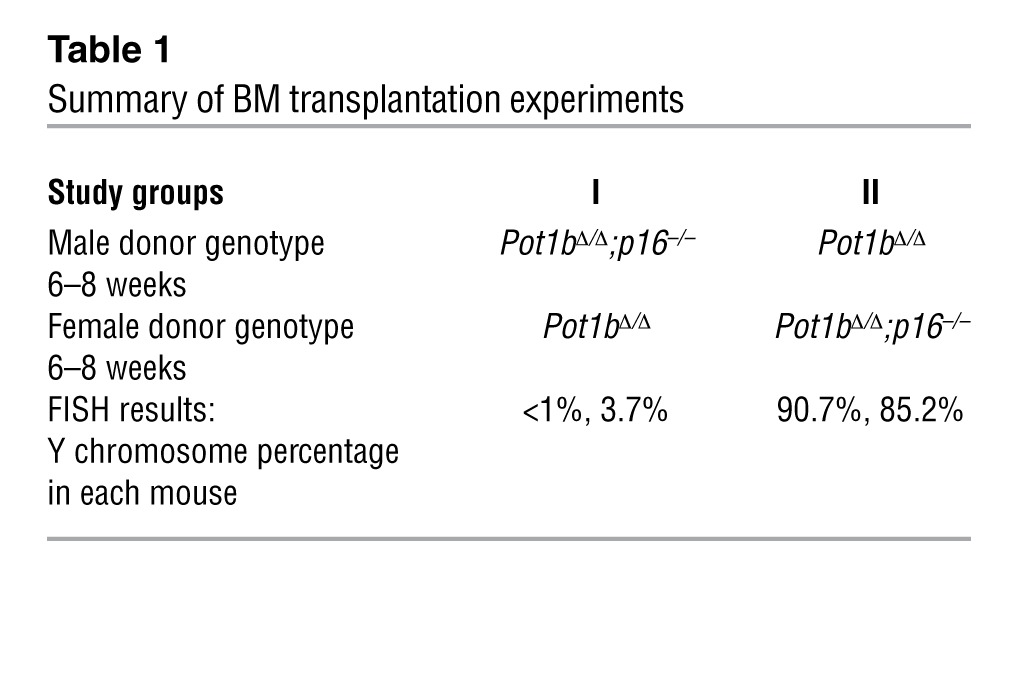

To explore further the mechanisms underlying the accelerated BM failure phenotype observed in DK mice, we examined BM from mouse cohorts at 8 to 10 and 20 to 25 weeks of age. BM cellularity and colony-forming units (CFUs) were similar in WT, Pot1bΔ/Δ, and DK mice at 8 to 10 weeks of age (Figure 2A). However, by 20 to 25 weeks of age, the total nucleated cell count in DK BM was significantly decreased (Figure 2B). Consistent with these results, DK BM cells also displayed a decreased number of CFUs, demonstrating a defect in the proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells (Figure 2B). To determine whether the accelerated loss of DK BM proliferative capacity was cell intrinsic or due to the BM microenvironment, we performed 1:1 competitive BM transplantation, in which whole BM (WBM) cells from a 6- to 8-week-old male DK donor were mixed with age-matched female Pot1bΔ/Δ WBM and then injected into lethally irradiated SCID mice. The converse experiment was also performed, in which WBM cells derived from male Pot1bΔ/Δ mice were mixed with female DK donor WBM cells (Figure 2C and Table 1). Three months after stable BM engraftment, FISH was used to quantify the number of Y chromosomes present in the reconstituted BM compartment. In 4 of 4 recipients, WBM cells from Pot1bΔ/Δ donors, irrespective of sex, always outcompeted WBM cells derived from DK mice (Figure 2C and Table 1). This result suggests an intrinsic defect of hematopoiesis in DK mice. Rather than improving hematopoietic function, the deletion of p16INK4a instead accelerated the loss of BM proliferative capacity in Pot1bΔ/Δ mice, leading to progressive BM failure and early death.

Figure 2. Increased proliferative defects in DK hematopoietic cells.

(A) Quantification of total nucleated BM cells isolated from mice of the indicated genotypes (left panel), representative images from BM mononuclear cell colony-forming assays (CFAs) in M3434 media (middle panel) and quantification of CFAs from mice of the indicated genotypes at 8 to 10 weeks of age (right panel). Each genotype consists of cells isolated from a minimum of 4 mice. Error bars represent the SEM. (B) Same as A, except cells were isolated from mice of the indicated genotypes at 20 to 25 weeks of age. Error bars represent the SEM. (C) Representative Y chromosome–specific probe FISH images of BM transplantation experiments. Arrow points to labeled Y chromosome (gray); DAPI-stained cell nuclei. For A and B, a two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance.

Table 1.

Summary of BM transplantation experiments

Increased depletion of LK/LSK cells in DK mice.

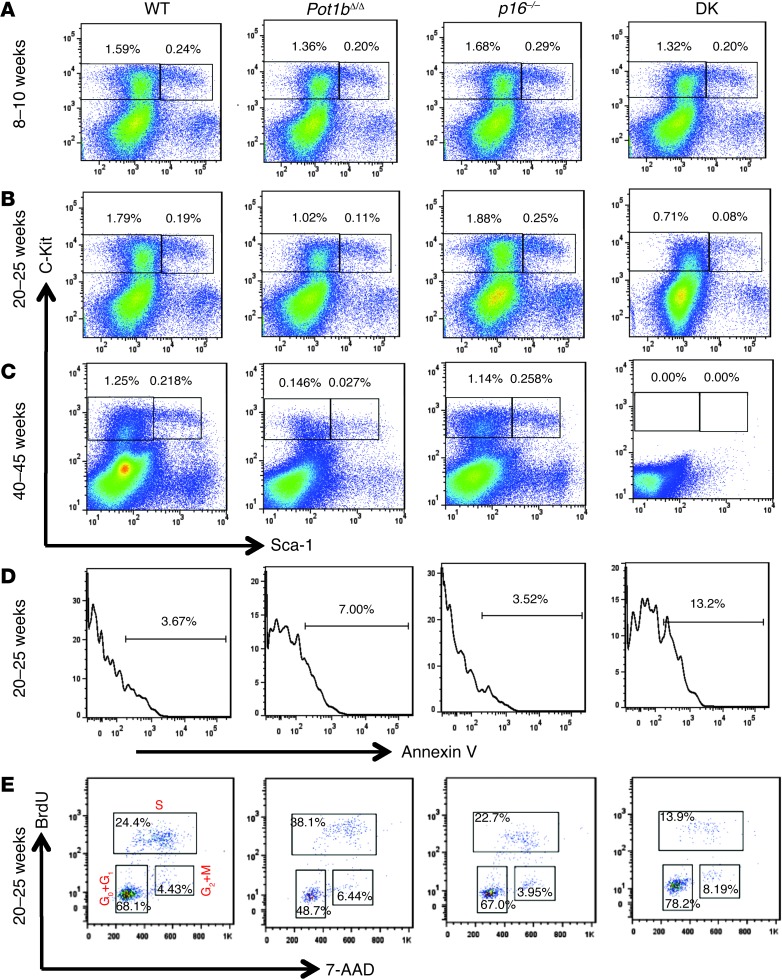

To investigate whether the BM proliferative defect was due to the progressive loss of primitive hematopoietic cell populations, we examined Lin–, Sca-1+, c-Kit+ (LSK) cells, a population enriched in hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitors, and Lin–, Sca-1–, c-Kit+ (LK) cells, a population enriched in hematopoietic progenitor cells, in 8- to 10-, 20- to 25-, and 40- to 45-week-old WT, Pot1bΔ/Δ;p16–/–, and DK mice. FACS analysis revealed normal levels of LK and LSK cells in WT and p16–/– mice of all ages, as well as in 8- to 10-week-old DK and Pot1b-null mice (Figure 3A). While the loss of LK and LSK populations was observed in both Pot1bΔ/Δ and DK mice by 20 to 25 weeks of age, DK mice displayed more severe depletion of LK/LSK cells (0.19% LSK and 1.79% LK for WT; 0.08% LSK and 0.71% LK for DK; and 0.11% LSK and 1.02% LK for Pot1bΔ/Δ BM) (Figure 3B). By 40 to 45 weeks, both LSK and LK populations were completely depleted in DK mice, while age-matched Pot1bΔ/Δ mice still retained some LSK (0.027%) and LK (0.146%) cells (Figure 3C). Compared with 20- to 25-week-old Pot1bΔ/Δ mice, LSK cells isolated from DK mice also exhibited increased annexin V staining, documenting increased apoptosis in the primitive hematopoietic cells (Figure 3D). Finally, BrdU labeling of LSK cells isolated from 20- to 25-week-old mice revealed that 24.4% of WT cells and 38.1% of Pot1b-null LSK cells were in the S phase, compared with only 13.9% for DK LSK cells. In addition, 78.2% of DK LSK cells accumulated in the G0/G1 phases of the cell cycle (Figure 3E). These results suggest that LK and LSK cells are depleted in DK mice as a result of increased apoptosis and cell cycle arrest.

Figure 3. Increased loss of BM cells in aging Pot1bΔ/Δ;p16–/– mice.

Representative FACS analysis of multilineage-negative cell populations derived from the BM of mice of the indicated genotypes at 8 to 10 weeks of age (A), 20 to 25 weeks of age (B), and 40 to 45 weeks of age (C). Numbers are the percentage of LSK and LK cells in total BM. Each genotype comprises a minimum of 4 mice. (D) Representative histograms showing annexin V profiles of LSK cells isolated from the BM of 20- to 25-week-old mice of the indicated genotypes. Each genotype includes cells from a minimum of 3 mice. (E) Cell cycle status of 20- to 25-week-old BrdU-labeled mouse LSK cells. A representative FACS plot from experiments with at least 3 mice of each indicated genotype is shown.

Elevated telomere dysfunction in DK hematopoietic cells.

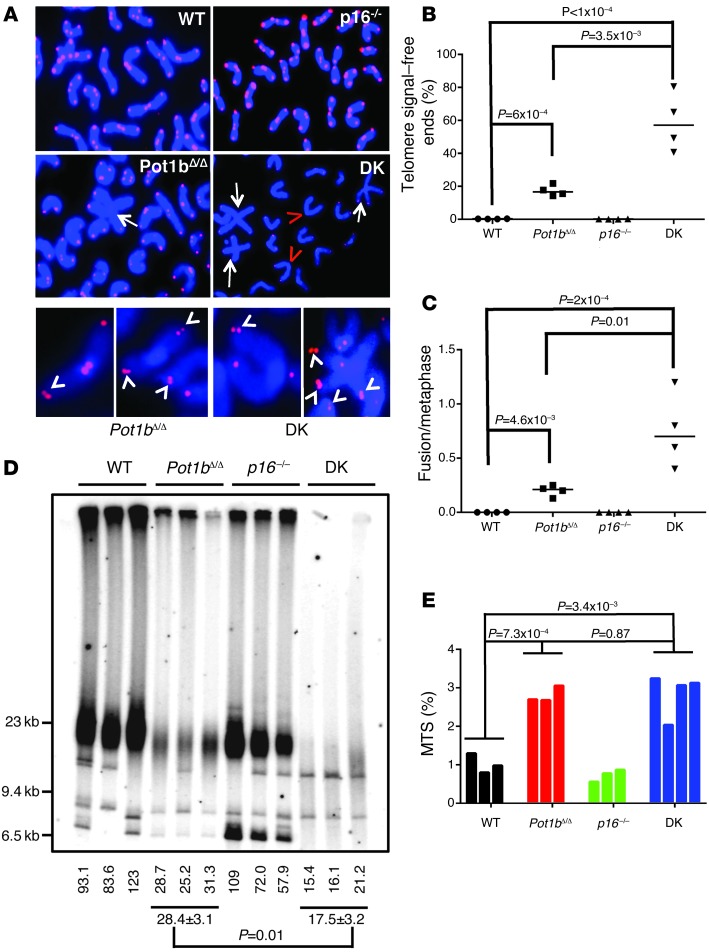

We postulated that the increased apoptosis and cell cycle arrest phenotypes observed in 40- to 45-week-old DK LK/LSK cells were likely due to progressive telomere dysfunction following Pot1b deletion (30). Compared with age-matched WT BM cells, telomere FISH analysis of 40- to 45-week-old DK BM cells revealed a significant increase in the number of chromosomal ends without telomeric signals (signal-free ends: 0.27% ± 0.04% for WT, 58.88% ± 8.79% for DK, and 17.35% ± 1.65% for Pot1bΔ/Δ cells) (Figure 4, A and B). In addition, compared with WT and Pot1bΔ/Δ-null cells, a significantly increased number of end-to-end chromosome fusions was observed in aged DK cells (Figure 4, A and C). Telomere restriction fragment length (TRF) Southern blot analysis of splenocyte DNAs isolated from 40- to 45-week-old WT, p16–/–;Pot1bΔ/Δ, and DK mice confirmed that compared with WT and Pot1bΔ/Δ cells, DK cells possessed significantly shortened, almost undetectable, telomere signals (Figure 4D). Telomeres lengths were comparable in 20- to 25-week-old DK and Pot1bΔ/Δ cells, suggesting that compared with Pot1bΔ/Δ splenocytes, aged DK cells experienced elevated telomere shortening with increasing age (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3). However, in quiescent liver cells, telomere lengths in DK and Pot1bΔ/Δ cells were comparable (Supplemental Figure 4). One mechanism for accelerated telomere loss is through increased cellular proliferation. To test the hypothesis that increased proliferation in DK cells contributed to increased telomere shortening, we used BrdU incorporation to monitor the cell cycle profiles of LK and LSK hematopoietic cells isolated from young (4- to 5-week-old) WT, Pot1bΔ/Δ;p16–/–, and DK mice. The cell cycle profiles in DK cells were not significantly different from those of WT, Pot1bΔ/Δ, or p16–/– cells, indicating that DK cells did not proliferate rapidly to exhaust their telomere reserves (Supplemental Figure 5A). Instead, we found that 40- to 45-week-old DK cells possess approximately 2.8 times more multiple telomere signals (MTSs) than WT cells (2.81 ± 0.21 MTSs in DK cells vs. 1.02 ± 0.25 in WT cells) (Figure 4, A and E). MTSs are indicative of fragile telomeres arising from replication fork stalling on repetitive telomere sequences (44–46). An increased number of stalled replication forks at telomeres promotes telomere-telomere recombination, resulting in rapid telomere loss (46). Although there was no statistically significant increase in the number of MTSs observed in DK BM cells compared with Pot1bΔ/Δ cells, the substantially increased number of telomere-free ends observed in DK cells suggests that the number of MTSs scored in DK cells was actually a gross underrepresentation.

Figure 4. Severe telomere dysfunction in Pot1bΔ/Δ;p16–/– hematopoietic cells.

(A) Telomere FISH analysis on metaphase chromosome spreads of BM cells of the indicated genotypes using Tam-OO-(CCCTAA)4 telomere PNA (red) and DAPI (blue). A minimum of 50 metaphases were analyzed per genotype. Arrows indicate fused chromosomes; red arrowheads indicate signal-free ends. Bottom panels show examples of the fragile telomere phenotype observed in 40- to 45-week-old Pot1bΔ/Δ and DK mouse BM cells. White arrowheads point to fragile telomeres. (B) Quantification of the number of telomere signal–free ends found in BM metaphases isolated from mice of the indicated genotypes. n = 4 for each genotype examined. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. (C) Quantification of the number of chromosome fusions in BM metaphases isolated from mice of the indicated genotypes. n = 4 for each genotype examined. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. (D) Telomere length determination in 40- to 45-week-old mouse spleen cells. HinfI/RsaI digested splenocyte genomic DNA of the indicated genotypes was hybridized under denatured conditions with a 32P-labeled [CCCTAA]4-oligo to detect total telomere DNA. Telomere signal intensity (percentage) was quantified by setting WT total telomere DNA as 100%. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. (E) Quantification of fragile telomeres observed in BM cells of the indicated genotypes. A total of 50 metaphases were scored for each mouse, and quantification of MTSs from metaphases isolated from individual animals is shown. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance.

Activation of an ATR-dependent DDR and p53-dependent DDR in DK cells.

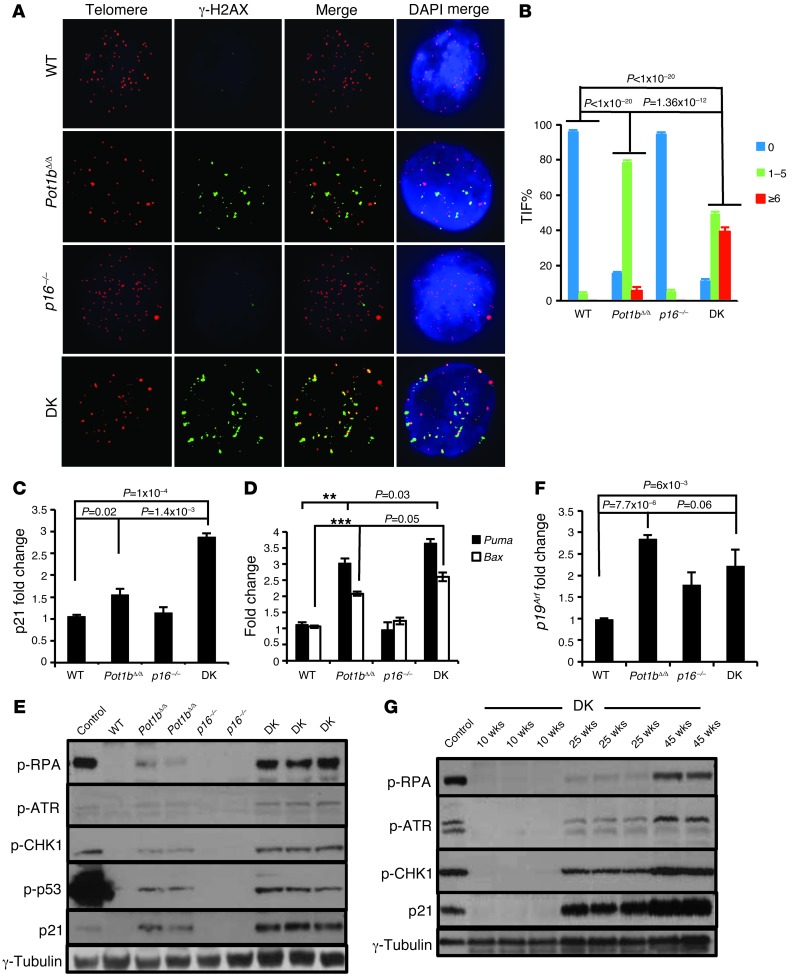

We used the dysfunctional telomere–induced foci (TIF) assay to quantitatively determine the number of dysfunctional telomeres present by scoring for the association of DNA damage proteins with telomeres. The DNA damage protein γ-H2AX did not associate appreciably with telomeres in 20- to 25-week-old WT or p16–/– LSK cells, with less than 10% of these LSK cells displaying 1–5 TIF per genotype (3.0% TIF in WT and 5.33% TIF in p16–/– cells). In contrast, Pot1bΔ/Δ LSK cells displayed 1–5 TIF in 78 ± 3% cells, with 5.33 ± 3% cells possessing more than 6 TIF (Figure 5, A and B). DK LSK cells exhibited significantly more dysfunctional telomeres compared with Pot1bΔ/Δ cells, with 1–5 TIF observed in 49.5 ± 2.6% cells and more than 6 TIF observed in 39.2 ± 2.5% cells (Figure 5, A and B). Since a G0/G1 cell cycle arrest phenotype was prominent in DK LSK cells, we next examined the expression of p21 in these cells. DK LSK cells displayed a significant increase in p21 expression (2.9 ± 0.13-fold compared with WT cells, and 1.4 ± 0.14-fold compared with Pot1bΔ/Δ cells) (Figure 5C), as well as increased p21 protein levels by Western analysis (Figure 5, E and G). The increased p21 levels correlated well with the increased number of SA-β-galactosidase–positive splenocytes, suggestive of elevated cellular senescence in DK cells (Supplemental Figure 5, B and C). We next determined the expression levels of Puma and Bax, genes involved in p53-dependent apoptosis, in DK LSK cells. Compared with Pot1bΔ/Δ LSK cells, DK LSK cells displayed significantly increased Puma and Bax expression (Figure 5D). Taken together, our data suggest that dysfunctional telomere–initiated p53-dependent cellular senescence and apoptosis directly contributes to the proliferative failure observed in DK LSK cells.

Figure 5. Elevated ATR-dependent DDR and p53 stabilization in Pot1bΔ/Δ;p16–/– mice.

(A) Representative TIF images of LSK cells from mice of the indicated genotypes. Cells were stained with anti–γ-H2Ax antibody (green), the PNA telomere probe Tam-OO-(CCCTAA)4 (red), and DAPI (blue). A minimum of three 20- to 25-week-old mice per genotype were used in all analyses. (B) Quantification of the percentage of cells with γ-H2AX–positive TIF in LSK cells of the indicated genotypes. A total of 150 nuclei were scored per genotype. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. Error bars represent the SEM. (C and D) Representative real-time PCR quantification of mRNA expression levels of p21 (C) and Puma and Bax (D) in sorted LSK cells from 20- to 25-week-old mice of the indicated genotypes. Each experiment was repeated in triplicate. P < 0.01 for both ** and ***. Error bars represent the SEM. (E) Immunoblot analysis for p-RPA, p-ATR, p-CHK1, p-p53, and p21 levels in 40- to 45-week-old spleens from mice of the indicated genotypes. Aphidicolin-treated cells were used as positive controls, and γ-tubulin served as a loading control. (F) Real-time PCR quantification of p19Arf expression levels of sorted LSK cells from mice of the indicated genotypes. Each experiment was repeated in triplicate. Error bars represent the SEM, and a two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. (G) Immunoblot analysis for p-RPA, p-ATR, p-CHK1, and p21 levels in DK mouse spleens of the indicated ages. γ-Tubulin served as a loading control.

The increased number of MTSs observed in aged DK BM cells suggests the presence of stalled replication forks at or near telomeres. Stalled replication forks not only promote rapid telomere loss, but can lead to the formation of ss DNA that activates an ATR-dependent DDR, resulting in cell cycle arrest and proliferative defects (44, 46). While the deletion of Pot1b by itself activates an ATR-dependent DDR, this response was not robust in vivo due to the presence of endogenous POT1a (13, 20). To test the hypothesize that the deletion of p16INK4a in 40- to 45-week-old Pot1b-null hematopoietic cells augmented the ATR-dependent DDR pathway, we monitored the levels in splenocytes of replication protein A (RPA), which localizes to ss DNA associated with stalled replication forks and signals the ATR-CHK1–dependent DDR pathway (47). We found a robust increase in phosphorylated (p-) RPA, ATR, and CHK1 expression in DK splenocytes, but not in age-matched p16–/– and WT cells (Figure 5E and Supplemental Figure 6A). Since p-ATR and p-CHK1 levels were only slightly elevated in age-matched Pot1bΔ/Δ splenocytes, our results suggest that deleting both p16INK4a and Pot1b in highly proliferative cells exacerbated the ATR-dependent DDR. Importantly, ATR activation resulted in increased p53 phosphorylation in DK (and to a lesser extent in Pot1bΔ/Δ) cells (Figure 5E and Supplemental Figure 6A), with only a modest increase in p53 transcription (Supplemental Figure 6B), suggesting that the p21-dependent cell cycle arrest and elevated apoptosis observed in these cells is primarily due to posttranslational activation of p53 (48). The activation of p53 was not accompanied by increased p19Arf (Figure 5F). Finally, we found that the level of p-ATR, p-CHK1, p-RPA, and p21 expression in DK splenocytes increased only with advancing age, with robust expression of these checkpoint proteins prominent only after 25 weeks of age (Figure 5G and Supplemental Figure 6C). Taken together, our data suggest that the ATR-dependent DDR is upregulated in DK cells, resulting in the activation of p53 and its downstream checkpoint responses that cause the acceleration of proliferative defects in the hematopoietic system. p16INK4a thus plays an important role in protecting proliferating tissues from an ATR checkpoint response emanating from uncapped telomeres devoid of POT1b.

Deletion of p21 rescues cellular proliferative defects in Pot1bΔ/Δ mice.

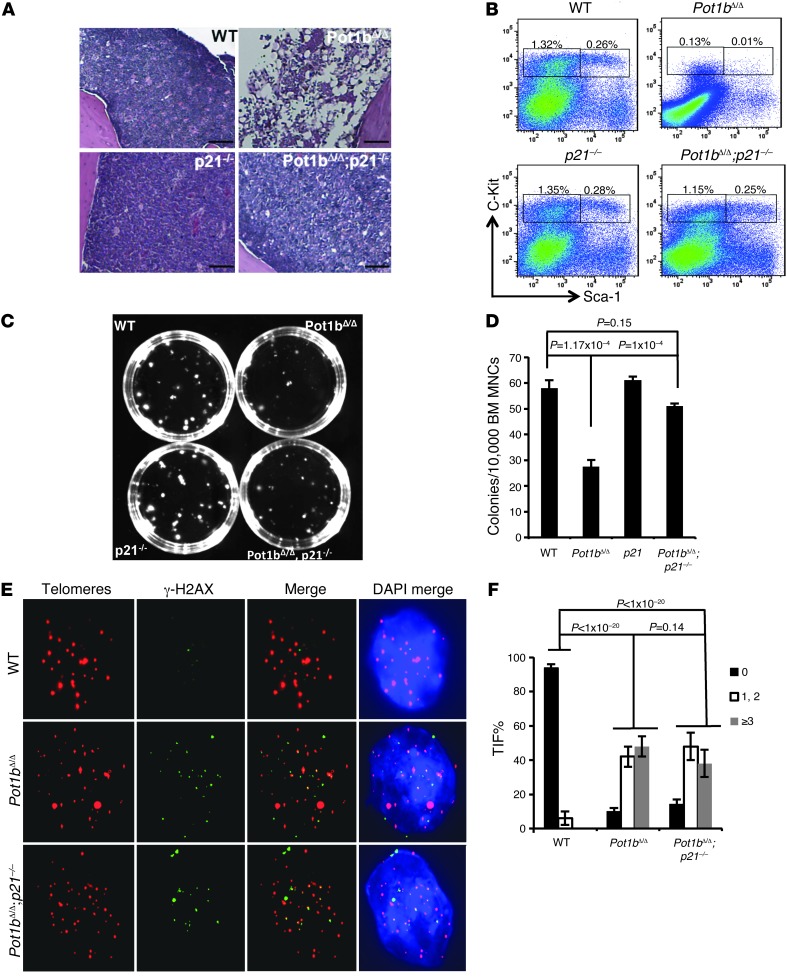

Since the loss of LK/LSK proliferative capacity in both Pot1bΔ/Δ and DK mice was accompanied by increased p21 expression, we hypothesized that deletion of p21 might ameliorate the cell cycle arrest phenotypes observed in Pot1b-deleted cells. While we attempted to generate Pot1bΔ/Δ;p16–/–;p21–/– mice to test this hypothesis, for unknown reasons we were unable to obtain triple-KO animals. Instead, we generated aged Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– mouse cohorts to explore the impact of p21 deletion on highly proliferative cells in the absence of Pot1b. Even at 70 to 80 weeks of age, all Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– mice displayed normocellular BM with trilineage hematopoiesis, indistinguishable from age-matched WT mice. In contrast, by this age, all Pot1bΔ/Δ mice displayed BM hypocellularity, with several progressing to BM failure (Figure 6A and data not shown). FACS analysis revealed that the percentage of LSK cells in 70- to 80-week-old mouse Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– BM was similar to that found in same-age WT BM (0.26% for WT vs. 0.25% for Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– cells), a significant improvement compared with BM from age-matched Pot1bΔ/Δ mice (Figure 6B). A similar result was observed in a colony-forming assay (58 ± 3 CFUs for WT, 51 ± 1 CFUs for Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/–, and 27.6 ± 2.5 CFUs for Pot1bΔ/Δ BM) (Figure 6, C and D). The TIF assay revealed that the DDRs remained elevated in Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– LSK cells at levels similar to those observed in Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21+/+ cells, but were significantly lower than the levels observed in DK cells (compare Figure 5B with Figure 6, E and F). The p53-dependent apoptotic response was not abrogated in Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21+/+ cells (Supplemental Figure 7). These data suggest that p21 activation and its function in replicative senescence/cell cycle arrest are primarily responsible for the proliferative defects observed in Pot1bΔ/Δ (and by inference in DK) LK/LSK cells. While telomeres still remained dysfunctional in Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– mice, the deletion of p21 greatly improved the proliferative capacity of Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– hematopoietic cells.

Figure 6. Deletion of p21 rescues the proliferative defects of Pot1bΔ/Δ hematopoietic cells.

(A) BM morphology in femurs isolated from 70- to 80-week-old mice of the indicated genotypes. Original magnification, ×10. (B) Representative FACS analysis of a multilineage-negative population in total BM isolated from 70- to 80-week-old mice of the indicated genotypes. Numbers are the percentage of LSK and LK cells in total BM. Each group represents a minimum of 4 mice. (C) Representative images of CFUs from BM MNCs of the indicated genotypes. (D) Quantification of CFUs. n = 4 mice per genotype. Error bars represent the SEM, and a two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. (E) Representative TIF images of LSK cells of the indicated genotypes. Cells were stained with anti–γ-H2Ax antibody (green), PNA probe Tam-OO-(CCCTAA)4 (red), and DAPI (blue). Cells derived from a minimum of three 40- to 45-week-old mice per genotype were used in each experiment. (F) Quantification of the percentage of cells with γ-H2AX–positive TIF in LSK cells of the indicated genotypes. A total of 150 nuclei were scored per genotype. Error bars represent the SEM, and a two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance.

Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– cells exhibit a stable genome without activating an ATR-dependent DDR.

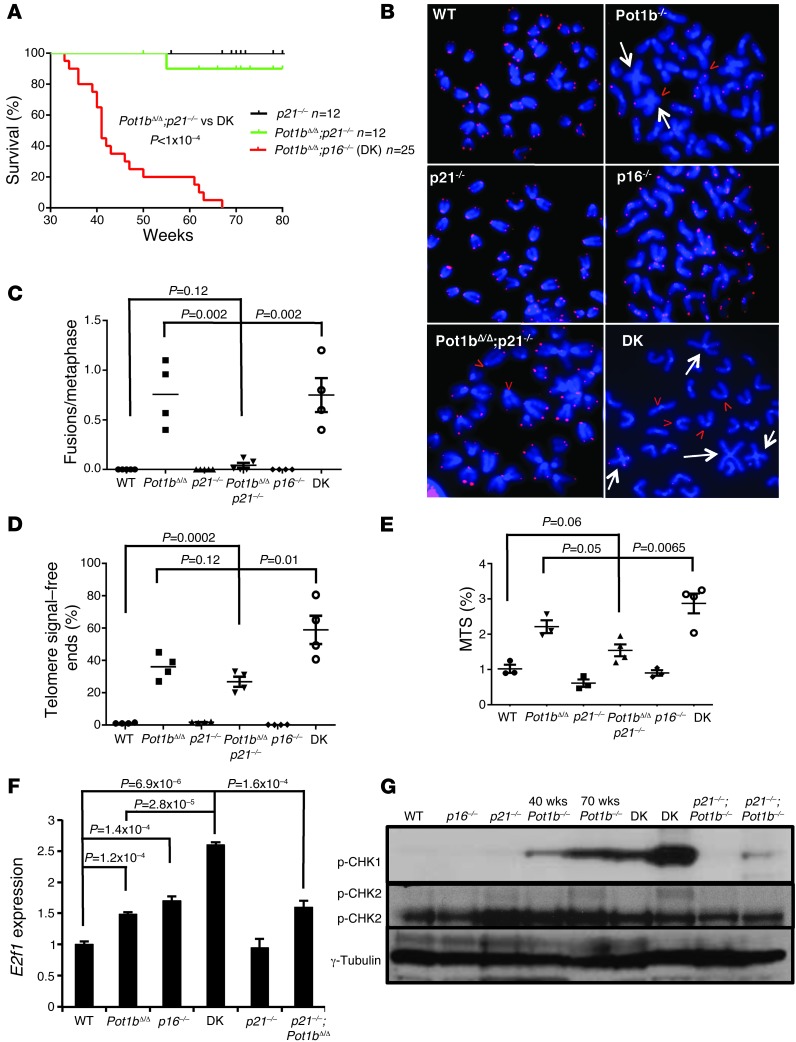

The restoration of cellular proliferative functions in Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– cells contrasts sharply with the proliferative defects observed in DK cells and suggests that in the setting of uncapped telomeres, p16INK4a functions to protect proliferative tissues, while p21 expression limits cellular proliferation. To further examine the differences between p16INK4a- and p21-dependent checkpoint responses in the absence of Pot1b, we first compared the lifespan of DK and Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– mice. While DK mice exhibited a median lifespan of 42 weeks, and all perished by 68 weeks, 90% of all Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– mice were alive at 80 weeks (Figure 7A). In contrast to DK splenocytes, Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– splenocytes exhibited minimal end-to-end chromosome fusions, significantly fewer telomere signal–free chromosome ends, a significantly reduced number of MTSs and decreased E2F1 expression (Figure 7, B–F). These results are in accord with the reduced level of TIF observed in Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– LSK cells (Figure 6E). Since the activation of an ATR-dependent DDR and downstream p53-dependent checkpoints negatively impacted the proliferative capacity of DK hematopoietic cells, we monitored ATR checkpoint activation in Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– splenocytes. We found robust p-CHK1 expression in 40- to 45-week-old DK cells, while p-CHK1 was not detected in age-matched Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– splenocytes and was present only at low levels in 85-week-old Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– splenocytes (Figure 7G). p-ATM was not detected in DK or other cells devoid of Pot1b, confirming that Pot1b deletion preferentially activates an ATR-dependent DDR (Figure 7G and ref. 13). We also monitored the level of E2f1 expression in DK splenocytes, since activation of the E2F1 pathway in the absence of p16INK4a has been shown to promote the formation of stalled and collapsed replication forks, leading to the generation of DSBs (49). RT-PCR revealed that E2f1 transcripts were 2.5-fold higher in DK splenocytes than in WT or Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– splenocytes (Figure 7F). Taken together, these results suggest that in DK splenocytes, the deletion of p16INK4a promotes enhanced activation of an ATR-dependent DDR, augmenting the activation of p53- and p21-dependent checkpoint responses to suppress cellular proliferation. In contrast, ATR activation and chromosomal aberrations were both negligible in Pot1bΔ/Δ; p21–/– splenocytes, therefore minimally impacting their proliferative capacity.

Figure 7. Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– mice exhibit increased lifespan and a stable genome with minimal ATR activation.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– and DK mice. A log-rank test was used to calculate statistical significance. (B) Telomere PNA-FISH revealed end-to-end chromosome fusions (white arrows) and telomere signal–free ends (red arrowheads) from BM metaphase spreads of the indicated genotypes. (C) Quantification of the number of chromosome fusions per metaphase in A. (D) Quantification of telomere signal–free chromosome ends in A. For both C and D, a total of 50 metaphases were scored per mouse, and a minimum of 4 mice were used per genotype. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. (E) Quantification of MTSs observed in BM metaphases from mice of the indicated genotypes. A total of 50 metaphases were scored per mouse, and a minimum of 4 mice were used per genotype. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. (F) Real-time PCR of E2f1 mRNA expression levels in spleens of the indicated genotypes. Each experiment was repeated in triplicate. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to calculate statistical significance. (G) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated CHK1 and CHK2 levels in spleens from mice of the indicated genotypes. γ-Tubulin served as a loading control. The ages of the mice from which the spleens were harvested are indicated.

Discussion

The accumulation of p16INK4a in tissues and stem cells results in decreased proliferative capacity and is a biomarker for cellular senescence (36–39, 50, 51). The elimination of p16INK4a-expressing cells is associated with a reduction in certain age-related phenotypes in a murine progeroid model, suggesting that interventions to eliminate senescent cells by modulating p16INK4a function might represent a viable therapeutic option to combat age-related diseases (41). Unexpectedly, however, this report shows that deletion of p16INK4a not only failed to rescue the aging phenotypes observed in aged Pot1bΔ/Δ mice possessing dysfunctional telomeres, but instead accelerated organ impairment. Compared with WT, p16INK4a–/–, and Pot1bΔ/Δ mice, DK mice displayed a significantly shortened median lifespan with increased functional defects in highly proliferative organs, including the hematopoietic system, small intestine, and testes. We found that the ATR-dependent DDR is robustly activated in DK hematopoietic cells, resulting in p53 stabilization, increased p21-dependent cell cycle arrest, and elevated p53-dependent apoptosis. This enhanced p53-dependent DDR severely compromised the proliferative capacity of DK LK/LSK cells, resulting in failure to reconstitute the BM of lethally irradiated recipients. These results indicate that p16INK4a plays important protective functions in proliferative cells with dysfunctional telomeres. Such a genome-protection role of the CDKN2a locus has been suggested in other age-related contexts (52).

Both the p16INK4a and p53/p21 pathways are involved in the activation of cellular senescence. p16INK4a is a potent inhibitor of the kinase activities of CDK4/6, resulting in Rb hypophosphorylation, binding to E2F1, the initiation of cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase, and the onset of cellular senescence (53–55). Since POT1b plays an important role in repressing an ATR-dependent DDR at telomeres (12, 13, 20, 29), we postulate that the deletion of p16INK4a further augmented ATR activation in aging DK cells. This notion is supported by our findings that (a) profound proliferative defects in DK LSK/LK cells were observed only in aged DK mice with progressively shortened telomeres, and (b) effectors of the ATR pathway, including phosphorylated ATR, RPA, and CHK1, were all upregulated in DK splenocytes but not in age-matched Pot1bΔ/Δ splenocytes. Augmentation of the ATR-dependent DDR in DK cells likely stems from the dual activation of this pathway by telomeres devoid of POT1b and through the activation of E2F1 in the absence of p16INK4a (Figure 7, F and G). Abnormal activation of E2F1 results in the formation of stalled and collapsed replication forks, which can activate ATR (49). Telomeres devoid of TRF1 also result in the formation of stalled forks and the activation of an ATR-dependent DDR (22). Elevated replication fork stalling at telomeres, manifested as an increased number of MTSs, was prominent in DK cells, suggesting that POT1b also plays a role in telomere replication (Figure 5). The cooperative activation of the ATR-dependent DDR results in p53 stabilization and activation of p53-dependent downstream checkpoint responses in proliferative DK cells (Supplemental Figure 8). In response to DNA damage, E2F1 has also been shown to activate Puma transcription (56, 57), suggesting the possibility of cooperative activation of p53-dependent apoptotic responses by uncapped telomeres and E2F1 in DK cells (Figure 5D).

Stimulation of the p53/p21-dependent cellular senescence pathway by dysfunctional telomeres and damaged DNA has been shown to be an important tumor suppressive mechanism in vivo (27, 28, 58, 59) and could arise as a consequence of p53 stabilization by various genotoxic stressors (60, 61). In our study, upregulation of the p53/p21-dependent senescence program by dysfunctional telomeres, not p53-dependent apoptosis, appeared to be instrumental in ushering the proliferative arrest phenotypes observed in DK cells, since deletion of p21 functionally rescued in vivo proliferative detects in Pot1bΔ/Δ;p21–/– mice (Figures 6 and 7). Since p21 inhibits CDKs, activates Rb, and represses E2F1 function (62), we postulate that deletion of p21 attenuates both p53- and Rb-mediated cellular senescence programs in addition to the DNA checkpoint responses induced by E2F1. In agreement with a previous study (63), our observation highlights the importance of the p53/p21 cellular senescence pathway in limiting the proliferative capacities of cells bearing dysfunctional telomeres. Importantly, stabilization of p53 by dysfunctional telomeres in DK cells was not due to p19Arf upregulation, since the level of p19Arf transcripts did not increase in aged DK cells.

A previous report revealed that p16–/– MEFs expressing the dominant-negative allele TRF2ΔBΔM experienced growth arrest with a p53-dependent, but a p16INK4a-independent, senescence morphology (43). These authors suggest that in contrast to human cells, the p16INK4a/Rb pathway in mouse cells is not responsive to dysfunctional telomeres. Our findings clearly show the detrimental effects that loss of p16INK4a function exerts on proliferative mouse cells bearing dysfunctional telomeres in vivo. We speculate that the inability to detect a senescent phenotype in p16–/– MEFs following TRF2 depletion could be due to (a) the differential sensitivities of p16–/– MEFs versus p16INK4a–/– proliferative primary tissues to dysfunctional telomere–induced DDR; (b) to the distinct cellular responses to the DDR elicited by acute (TRF2ΔBΔM overexpression in MEFs) versus chronic (Pot1b deletion in DK cells) telomere dysfunction; and (c) to the distinct ATM-dependent DDR activated by the removal of TRF2 versus an ATR-dependent DDR following Pot1b deletion (8, 14, 23). Our studies thus highlight the importance of proper genetic and cellular context in interpreting physiological responses of p16INK4a deletion in the setting of telomere dysfunction.

Methods

Mice.

The Pot1bΔ/Δ and p16INK4a–/– mice were generated as described previously (29, 64). All mice were maintained according to the IACUC-approved protocols of Yale University. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 5.01 software (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Histology and TUNEL assays.

Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, paraffin embedded, sectioned at 5-μm thickness, and stained with H&E. The TUNEL assay was performed using the ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Chemicon) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Competitive BM transplantation.

Because our mouse cohorts were kept in a mixed genetic background, competitive BM transplantations were performed using irradiated SCID recipients. Nucleated cells isolated from BM were prepared as described (30), with male and female donor cells mixed together at a ratio of 1:1. Mixed cells (1 × 107) were injected through the tail vein into 5.0-Gy-irradiated SCID recipient mice. Irradiated, uninjected control mice were used in every experiment, and these mice died within 10 days after irradiation. To assess the degree of reconstitution, BM cells from recipient mice were analyzed by FISH using a Y chromosome probe 3 months after transplantation (30).

Flow cytometric analysis and complete blood count.

Total BM cells (1 × 107) were centrifuged and resuspended in 200 μl of HBSS+ (Invitrogen). Cells were stained for 15 minutes with a cocktail of antibodies including nine lineage markers: Ter-119, CD3, CD4, CD8, B220, CD19, IL-7Rα, GR-1, and Mac-1 (eBioscience) conjugated with APC-Cy-7 (47-4317; eBioscience). The cocktail also contained anti–Sca-1-PE (12-5981) and anti–c-Kit-APC (both from eBioscience). After staining, cells were washed, resuspended in HBSS+, and analyzed by flow cytometry (LSRII; BD). LSK populations were selected based on low or negative expression of the mature lineage markers and dual-positive expression for Sca-1 and c-Kit. To determine the proliferative status of LSK cells, BrdU was i.p. injected into mice at a dose of 150 mg/kg body weight 2 hours before euthanization. Analysis of BrdU incorporation was performed using the FITC BrdU Flow Kit (BD). To quantitatively determine the percentage of cells that were actively undergoing apoptosis, the Annexin V-PE Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen) was used. Automated complete blood counts were performed using a Hemavet 850FS (Drew Scientific).

Isolation of total BM cells and colony-forming assay.

Hindlimb bones were dissected, and the marrow was flushed through a 21-gauge needle into HBSS+, 2% FBS (Invitrogen), and 10 mM HEPES. The cells were passed through a 25-gauge needle twice and filtered (45-μm filter) to ensure a single-cell suspension. Nucleated cells were counted manually after the lysis of rbcs with 3% acetic acid in methylene blue (STEMCELL Technologies). For the colony-forming assay, 1 × 104 BM mononucleated cells (BM MNCs) were cultured in 35-mm dishes containing MethoCult 3434 (STEMCELL Technologies) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The colonies were counted on day 12.

Microscopy.

Metaphase chromosomes from BM were prepared 1–2 hours after colcemide treatment, as previously described (17), and subjected to Giemsa staining and/or telomere peptide nucleic acid (PNA) FISH staining to label telomeres. Depending on the quality of metaphase spreads, 20–50 metaphases from each sample were analyzed in detail. TIF analysis was performed as previously described to quantitate dysfunctional telomeres in LSK cells (17).

RT-coupled real-time PCR.

Total RNA was prepared using QIAGEN’s RNeasy Micro kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For first-strand cDNA synthesis, 1 μg of total RNA, 20 pmol of Oligo (dT)12–18, and 200 units of SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) were mixed in a final volume of 20 μl. Synthesized cDNA (1 μl) was added to a 20-μl PCR mixture containing TaqMan Gene Expression Assay primers (Applied Biosystems) and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix. Each sample was amplified in triplicate. PCR consisted of 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, annealing, and amplification at 60°C for 60 seconds in an ABI7900HT Sequence Detection System machine (Applied Biosystems). The specific primers for the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay primers were as follows: PUMA: Mm00519268_m1; BAX: Mm00432050_m1; p21:Mm00432448_ml; p53: Mm00519571_ml; E2F1: Mm00432936_ml. 18S rRNA primers (4319413E or Mm00519571_ml) were used as internal controls.

Western blot analysis.

The antibodies used for Western blot analysis were as follows: phosphor-p53(Ser15) (Cell Signaling Technology; 1:500); phosphor-ATR (Cell Signaling Technology; 1:500); phosphor-CHK1 (Cell Signaling Technology; 1:500), phosphor-CHK2 (BD Transduction Laboratories; 1:500), phosphor-PRA32 (Bethyl; 1:1,000), anti-mouse p21 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., 1:500), and phorsphor-Rb (BD Pharmingen; 1:500). Anti-mouse γ-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich; 1:10,000) was used as a loading control.

TRF Southern blotting.

Total genomic DNA (5–10 μg) was separated by pulse-field gel electrophoresis (BioRad). The gels were dried at 50°C, prehybridized at 58°C in Church mix (0.5 M NaH2PO4, pH 7.2, 7% SDS), and hybridized with γ-32P-(CCCTAAA)4 oligonucleotide probes at 58°C overnight. Gels were washed with 4XSSC and 0.1% SDS buffer at 55°C and exposed to phosphorimager screens. After in-gel hybridization for the G-overhang under native conditions, the gels were denatured with 0.5 N NaOH, 1.5 M NaCl solution and neutralized with 3 M NaCl, 0.5 M Tris-Cl, pH 7.0, then reprobed with (TTTAGGG)4 oligonucleotide probes to detect total telomere DNA. To determine the relative G-overhang signals, the signal intensity for each lane was scanned with Typhoon (GE Healthcare) and quantified by ImageQuant (GE Healthcare) before and after denaturation. The G-overhang signal was normalized to total telomeric DNA and compared between samples.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software, version 5.01 (GraphPad Software Inc.), and all data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Datasets were compared using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed using the log-rank test. P values of 0.05 or less were considered significant.

Study approval.

The animal care and use program at Yale University maintains full accreditation from the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) and complies with U.S. Animal Welfare Regulations, the National Research Council (NRC) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Yale University has an approved Animal Welfare Assurance (A3230-01) on file with the NIH Office for Protection from Research Risks. The Assurance was approved May 16, 2007. Our mouse personnel have multiple years of experience working with mice. Our veterinarian Peter Smith is always available should health concerns arise. The animal protocols have been approved by the animal care and use program of Yale University (2010-11358) for 3 years and are renewed annually.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank M.J. You (The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA) and Marcus Bosenberg (Yale University School of Medicine) for analysis of pathology samples. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (RO1 CA129037, to S. Chang, and RO1 AG024379, to N. Sharpless).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Note regarding evaluation of this manuscript: Manuscripts authored by scientists associated with Duke University, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Duke-NUS, and the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute are handled not by members of the editorial board but rather by the science editors, who consult with selected external editors and reviewers.

Citation for this article: J Clin Invest. 2013;123(10):4489–4501. doi:10.1172/JCI69574.

References

- 1.O’Sullivan RJ, Karlseder J. Telomeres: protecting chromosomes against genome instability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;11(3):171–181. doi: 10.1038/nrm2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palm W, de Lange T. How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:301–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan SS, Chang S. Defending the end zone: studying the players involved in protecting chromosome ends. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(17):3773–3778. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boultwood J, et al. Telomere length in myelodysplastic syndromes. Am J Hematol. 1997;56(4):266–271. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199712)56:4<266::AID-AJH12>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere maintenance and human bone marrow failure. Blood. 2008;111(9):4446–4455. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-019729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savage SA, Giri N, Baerlocher GM, Orr N, Lansdorp PM, Alter BP. TINF2, a component of the shelterin telomere protection complex, is mutated in dyskeratosis congenita. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(2):501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walne AJ, Vulliamy T, Beswick R, Kirwan M, Dokal I. TINF2 mutations result in very short telomeres: analysis of a large cohort of patients with dyskeratosis congenita and related bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood. 2008;112(9):3594–3600. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-153445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng Y, Guo X, Ferguson DO, Chang S. Multiple roles for MRE11 at uncapped telomeres. Nature. 2009;460(7257):914–918. doi: 10.1038/nature08196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimitrova N, de Lange T. Cell cycle-dependent role of MRN at dysfunctional telomeres: ATM signaling-dependent induction of nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) in G1 and resection-mediated inhibition of NHEJ in G2. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(20):5552–5563. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00476-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortez D, Guntuku S, Qin J, Elledge SJ. ATR and ATRIP: partners in checkpoint signaling. Science. 2001;294(5547):1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1065521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abraham RT. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 2001;15(17):2177–2196. doi: 10.1101/gad.914401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denchi EL, de Lange T. Protection of telomeres through independent control of ATM and ATR by TRF2 and POT1. Nature. 2007;448(7157):1068–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature06065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo X, et al. Dysfunctional telomeres activate an ATM-ATR-dependent DNA damage response to suppress tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 2007;26(22):4709–4719. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimitrova N, de Lange T. Cell cycle-dependent role of MRN at dysfunctional telomeres: ATM signaling-dependent induction of nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) in G1 and resection-mediated inhibition of NHEJ in G2. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(20):5552–5563. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00476-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rai R, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Rnf8 stabilizes Tpp1 to promote telomere end protection. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(12):1400–4007. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn RL, et al. TERRA and hnRNPA1 orchestrate an RPA-to-POT1 switch on telomeric single-stranded DNA. Nature. 2011;471(7339):532–536. doi: 10.1038/nature09772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu L, et al. Pot1 deficiency initiates DNA damage checkpoint activation and aberrant homologous recombination at telomeres. Cell. 2006;126(1):49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palm W, Hockemeyer D, Kibe T, de Lange T. Functional dissection of human and mouse POT1 proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(2):471–482. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01352-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He H, et al. POT1b protects telomeres from end-to-end chromosomal fusions and aberrant homologous recombination. EMBO J. 2006;25(21):5180–5190. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kibe T, Osawa GA, Keegan CE, de Lange T. Telomere protection by TPP1 is mediated by POT1a and POT1b. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(4):1059–1066. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01498-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam YC, et al. SNMIB/Apollo protects leading-strand telomeres against NHEJ-mediated repair. EMBO J. 2010;29(13):2230–2241. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu P, Takai H, de Lange T. Telomeric 3′ overhangs derive from resection by Exo1 and Apollo and fill-in by POT1b-associated CST. Cell. 2012;150(1):39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rai R, et al. The function of classical and alternative non-homologous end-joining pathways in the fusion of dysfunctional telomeres. EMBO J. 2010;29(15):2598–2610. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown JP, Wei W, Sedivy JM. Bypass of senescence after disruption of p21CIP1/WAF1 gene in normal diploid human fibroblasts. Science. 1997;277(5327):831–834. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.d’Adda di Fagagna F, et al. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature. 2003;426(6963):194–198. doi: 10.1038/nature02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herbig U, Jobling WA, Chen BP, Chen DJ, Sedivy JM. Telomere shortening triggers senescence of human cells through a pathway involving ATM, p53, and p21(CIP1), but not p16(INK4a). Mol Cell. 2004;14(4):501–513. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cosme-Blanco W, et al. Telomere dysfunction suppresses spontaneous tumorigenesis in vivo by initiating p53-dependent cellular senescence. EMBO Rep. 2007;8(5):497–503. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldser DM, Greider CW. Short telomeres limit tumor progression in vivo by inducing senescence. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(5):461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He H, et al. Pot1b deletion and telomerase haploinsufficiency in mice initiate an ATR-dependent DNA damage response and elicit phenotypes resembling dyskeratosis congenita. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(1):229–240. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01400-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Shen MF, Chang S. Essential roles for Pot1b in HSC self-renewal and survival. Blood. 2011;118(23):6068–6077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-361527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng Y, Chan SS, Chang S. Telomere dysfunction and tumour suppression: the senescence connection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(6):450–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudolph KL, et al. Longevity, stress response, and cancer in aging telomerase-deficient mice. Cell. 1999;96(5):701–712. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Artandi SE, et al. Telomere dysfunction promotes non-reciprocal translocations and epithelial cancers in mice. Nature. 2000;406(6796):641–645. doi: 10.1038/35020592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shay JW, Pereira-Smith OM, Wright WE. A role for both RB and p53 in the regulation of human cellular senescence. Exp Cell Res. 1991;196(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobs JJ, de Lange T. Significant role for p16INK4a in p53-independent telomere-directed senescence. Curr Biol. 2004;14(24):2302–2308. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janzen V, et al. Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a. Nature. 2006;443(7110):421–426. doi: 10.1038/nature05159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishnamurthy J, et al. p16INK4a induces an age-dependent decline in islet regenerative potential. Nature. 2006;443(7110):453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature05092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molofsky AV, et al. Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature. 2006;443(7110):448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature05091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, et al. Expression of p16(INK4a) prevents cancer and promotes aging in lymphocytes. Blood. 2011;117(12):3257–3267. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-304402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito K, et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by ATM is required for self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2004;431(7011):997–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature02989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker DJ, et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479(7372):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khoo CM, Carrasco DR, Bosenberg MW, Paik JH, Depinho RA. Ink4a/Arf tumor suppressor does not modulate the degenerative conditions or tumor spectrum of the telomerase-deficient mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(10):3931–3936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700093104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. Different telomere damage signaling pathways in human and mouse cells. EMBO J. 2002;21(16):4338–4348. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sfeir A, et al. Mammalian telomeres resemble fragile sites and require TRF1 for efficient replication. Cell. 2009;138(1):90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez P, et al. Increased telomere fragility and fusions resulting from TRF1 deficiency lead to degenerative pathologies and increased cancer in mice. Genes Dev. 2009;23(17):2060–2075. doi: 10.1101/gad.543509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gu P, et al. CTC1 deletion results in defective telomere replication, leading to catastrophic telomere loss and stem cell exhaustion. EMBO J. 2012;31(10):2309–2321. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bartkova J, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature. 2006;444(7119):633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature05268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lakin ND, Jackson SP. Regulation of p53 in response to DNA damage. Oncogene. 1999;18(53):7644–7655. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bester AC, et al. Nucleotide deficiency promotes genomic instability in early stages of cancer development. Cell. 2011;145(3):435–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krishnamurthy J, et al. Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(9):1299–1307. doi: 10.1172/JCI22475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burd CE, et al. Monitoring tumorigenesis and senescence in vivo with a p16(INK4a)-luciferase model. Cell. 2013;152(1–2):340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matheu A, et al. Anti-aging activity of the Ink4/Arf locus. Aging Cell. 2009;8(2):152–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lukas J, et al. Retinoblastoma-protein-dependent cell-cycle inhibition by the tumour suppressor p16. Nature. 1995;375(6531):503–506. doi: 10.1038/375503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Medema RH, Herrera RE, Lam F, Weinberg RA. Growth suppression by p16ink4 requires functional retinoblastoma protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(14):6289–6293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Serrano M, Lee H, Chin L, Cordon-Cardo C, Beach D, DePinho RA. Role of the INK4a locus in tumor suppression and cell mortality. Cell. 1996;85(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81079-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carnevale J, Palander O, Seifried LA, Dick FA. DNA damage signals through differentially modified E2F1 molecules to induce apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(5):900–912. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06286-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hershko T, Ginsberg D. Up-regulation of Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3)-only proteins by E2F1 mediates apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(10):8627–8634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Braig M, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence as an initial barrier in lymphoma development. Nature. 2005;436(7051):660–665. doi: 10.1038/nature03841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michaloglou C, et al. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436(7051):720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature03890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sherr CJ, McCormick F. The RB and p53 pathways in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(2):103–112. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suh YA, et al. Multiple stress signals activate mutant p53 in vivo. Cancer Res. 2011;71(23):7168–7175. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim WY, Sharpless NE. The regulation of INK4/ARF in cancer and aging. Cell. 2006;127(2):265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Choudhury AR, et al. Cdkn1a deletion improves stem cell function and lifespan of mice with dysfunctional telomeres without accelerating cancer formation. Nat Genet. 2007;39(1):99–105. doi: 10.1038/ng1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharpless NE, et al. Loss of p16Ink4a with retention of p19Arf predisposes mice to tumorigenesis. Nature. 2001;413(6851):86–91. doi: 10.1038/35092592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.