Abstract

The aim of this study was determine the effectiveness of a mindfulness-based stress-reduction (MBSR) program on quality of life (QOL) and psychosocial outcomes in women with early-stage breast cancer, using a three-arm randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT). This RCT consisting of 172 women, aged 20–65 with stage I or II breast cancer consisted of the 8-week MBSR, which was compared to a nutrition education program (NEP) and usual supportive care (UC). Follow-up was performed at three post-intervention points: 4 months, 1, and 2 years. Standardized, validated self-administered questionnaires were adopted to assess psychosocial variables. Statistical analysis included descriptive and regression analyses incorporating both intention-to-treat and post hoc multivariable approaches of the 163 women with complete data at baseline, those who were randomized to MBSR experienced a significant improvement in the primary measures of QOL and coping outcomes compared to the NEP, UC, or both, including the spirituality subscale of the FACT-B as well as dealing with illness scale increases in active behavioral coping and active cognitive coping. Secondary outcome improvements resulting in significant between-group contrasts favoring the MBSR group at 4 months included meaningfulness, depression, paranoid ideation, hostility, anxiety, unhappiness, and emotional control. Results tended to decline at 12 months and even more at 24 months, though at all times, they were as robust in women with lower expectation of effect as in those with higher expectation. The MBSR intervention appears to benefit psychosocial adjustment in cancer patients, over and above the effects of usual care or a credible control condition. The universality of effects across levels of expectation indicates a potential to utilize this stress reduction approach as complementary therapy in oncologic practice.

Keywords: Mindfulness-based stress reduction program, Quality of life, Psychosocial factors, Expectancy, Breast cancer psychosocial intervention

Introduction

Emotional challenges facing women coping with the diagnosis and the treatment of breast cancer and the effect of such emotions on quality of life (QOL) have been well described [1–3]. Thus, a stress-management intervention makes sense in assisting women who are suffering from this illness. Various studies have shown benefit with an mindfulness-based stress-reduction (MBSR) intervention for depression [4], anxiety [5], and chronic pain [6], all of which are relevant in dealing with breast cancer.

The argument has been made that for the field to progress, it is essential to identify specific intervention–outcome associations and to identify where in the process from diagnosis through treatment and post-treatment recovery such effects can be expected [7]. Interventions for early-stage breast cancer patients have frequently combined elements of education/information, social and emotional support, stress management techniques, problem-solving, and other cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques [8–11]. More recently, interventions using MBSR also have been tested in cancer patients [12]. Such broad-based interventions may be important in addressing the diversity of problems noted above. However, to move psychosocial intervention research forward, it also seems important to distinguish intervention outcomes specific to a particular approach versus more non-specific effects of information or contact time with professionals.

To the best of our knowledge, only four breast cancer studies used a stress management approach with a randomized controlled design. Lengacher et al. [13, 14] compared an abbreviated MBSR intervention to a 6-week wait-list control group with 6 weeks of follow-up in stage I–III breast cancer patients and found significant benefit for QOL measures of physical functioning, depression, trait anxiety, and fear of recurrence. Shapiro et al. [15] looked at sleep quality with an MBSR intervention compared to a “free choice” usual care control and follow-up to 9 months; the results were an improvement in sleep quality, but not efficiency. However, the study participants were inadvertently informed of their group assignment before baseline data collection, and a quasi-experimental design was used. After an initial 3-month follow-up study, Antoni et al. [16–18] used a 10-week cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention compared to a one-day version with follow-up over 1 year and found decreased intrusive thoughts, anxiety, and emotional distress. In summary, these studies were limited using a wait-list control, lack of attention control for non-specific therapist effects, short follow-up, and inadvertently revealing study group assignment before baseline data collection.

The current study was designed to overcome the limitations of previous studies in testing the psychosocial and QOL outcomes using a short-duration MBSR-based program in women with early-stage (stage I or II) breast cancer. Subjects participated in the University of Massachusetts MBSR, which has formed the basis of the field of mindfulness-based stress reduction interventions [5, 6, 19–22]. MBSR was delivered in this randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT) by comparing MBSR to two control conditions: (1) a conventional usual care (UC) condition; and (2) a group nutrition education program (NEP) designed to be equivalent to the MBSR in terms of non-specific aspects of attention; with respect to contact time, elements of group support, and general credibility regarding potentially improving health outcomes. A credible active control condition is important, as it allows us to examine the specific effects of MBSR, as distinct from non-specific effects of increased attention.

Methods

The Breast Research Initiative for DetermininG Effective Strategies for coping with breast cancer (BRIDGES) study was a randomized clinical trial of 172 women diagnosed with breast cancer enrolled from four practice sites: The University and Memorial Hospital Campuses of the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center [(UMMC)—now named UMass Memorial Health Care (UMMHC)], Worcester, Mass; Fallon Community Health Plan, Worcester, Mass; and Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI). The Institutional Review Board of each participating institution reviewed and approved the protocol and assessment procedures and the Institutional Review Board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School approved all the recruitment and measurement procedures.

Eligibility

Women eligible to be in this study had newly diagnosed (within the past 2 years) stage I or II cancer of the breast; were between 20 and 65 years of age; were capable of understanding informed consent in English; planned to maintain residence in the study area for at least 2 years following recruitment; were Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0, 1, or 2 (i.e., able to function normally >50% of the time); were willing to accept randomization; and had a working home telephone and were willing to be contacted. Specific exclusion criteria included a previous diagnosis of cancer in the past 5 years, except non-melanoma skin cancer; current chronic substance abuse (either drug or alcohol); and past or present psychiatric or neurologic disorder that would preclude or severely limit participation in the study.

Description of the randomization conditions

Once enrolled, women were randomized into one of the three study conditions: MBSR, NEP, or UC. Women were block randomized by stage of disease (I or II), by age (±5 years) within menopausal group, and by institution.

The MBSR is a psychosocial intervention taught by highly trained instructors who are mental health clinicians and long-term meditation practitioners, which involves training in meditation and yoga [20]. Mindfulness can be defined as the practice of purposefully non-judgmentally paying attention in the present moment [20]. MBSR includes elements consistent with cognitive–behavioral therapy, group support, experiential focus, and a strong educational orientation.

As delivered in BRIDGES, the MBSR [20] consisted of three parts: (1) an introductory meeting for BRIDGES-only participants; (2) the 8-week standard MBSR intervention given to a heterogeneous group of patients with a variety of medical/psychiatric disorders, consisting of seven weekly 2.5 to 3.5-hour sessions and one 7.5 hour intensive silent retreat session in the 6th week; and (3) three monthly 2-hour sessions for BRIDGES-only participants following completion of the MBSR, focused on support, sharing and practice.

The NEP was a group nutrition education intervention, involving education and group meal cooking, focused on dietary change, i.e., a low-fat diet, using principles of social cognitive theory [23–26] and patient-centered counseling [27, 28]. The NEP was led by registered dietitians, and contained none of the key elements of MBSR except group support. Both interventions were matched for total contact time and homework commitments. Women randomized to UC received no formal intervention, but were allowed to participate in activities of their choice other than MBSR or the NEP. They received monthly phone calls to provide support and discover what other activities, if any, in which the women chose to participate. The MBSR and NEP interventions were delivered at a single site in Worcester, MA.

Measures

Data used in this report were obtained from self-assessment questionnaires, medical chart review, and anthropometric measurement. Information was obtained on study participants at four points: recruitment into the study (baseline); after completion of the interventions (4 months from beginning the intervention); at 12 months, and 24 months from beginning the intervention.

Psychological variables were assessed using standardized and validated self-administered questionnaires. The primary outcomes were (1) cancer-specific QOL, as measured by the breast cancer version of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-B) [29–32], using the overall scores and additional spirituality items; and (2) coping mechanisms, measured by the Dealing with Illness questionnaire [33]. This coping measure has been used with both cancer and AIDS patients and focuses on three broad dimensions of coping strategies: (a) active behavioral coping; (b) active cognitive coping; and (c) avoidance coping.

Secondary outcomes were more specific measures of emotional distress, as well as personality and coping dimensions. Indices of distress included the following:

Depressive symptoms, measured by the Beck Depression Inventory-I (BDI) [34], a widely-used 21-item self-report questionnaire with a range of 0–60. Scores in the range of 10–18 are generally seen as indicating mild depressive symptoms, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.

Anxiety symptoms, measured by the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [35]. This 21-item self-report inventory measures the presence and severity of anxiety symptoms. Scores range from 0 to 60, with scores indicating mild anxiety occurring in the range of 9–15, and higher levels with higher scores.

General distress, measured by the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) [36]. This measure has a General Severity Index (GSI), as well as ten symptom scales, including depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoia, and phobic anxiety.

Coping, subjective social support, and personality dimensions were measured by the following questionnaires.

Self-esteem: The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [37] is a widely used ten-item measure of self-esteem. Scores range from 0 to 30, with scores below 15 indicative of lower self-esteem.

Subjective social support was measured using the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale [38], which measures the extent to which people believe they have support and feel understood.

Cancer-specific coping and emotional responses were measured by the short form of the Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale (Mini-MAC) [39]. This questionnaire has often been used in cancer patients and measures five specific subscales of helpless–hopeless, anxious preoccupation, fighting spirit, avoidance, and fatalism responses to cancer.

Resilience in the face of adversity and stress were measured by the 13-item Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC) [40–42]. This measure has been predictive of improved outcomes over time in terms of health and general well-being. The two subscales measure meaningfulness and comprehensibility.

Degree of emotional control was measured by the Courtauld Emotional Control Scale (CEC) [43, 44]. This 21-item self-report questionnaire measures the extent of emotional control in patients with health problems. The total score ranges from 21 to 84, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of emotional control or emotional suppression. Subscales measure the extent to which an effort is made to suppress feelings of anger, anxiousness, or unhappiness.

To estimate compliance, adherence questions were asked to the MBSR group in class as well, and during unscheduled phone calls at 6 weeks and 10 months. To assess general expectancy, each participant was asked to complete a questionnaire regarding expectation of the anticipated helpfulness of the study arm into which she was randomized. The summary score was normally distributed, allowing classification of subjects above the mean to be classified as having high expectation and below the mean as having low expectation.

Hypotheses

As noted above, a wide range of psychosocial and QOL outcome variables were used to attempt to capture the specific effects of MBSR as compared to adopted the UC and active (NEP) control conditions. For the primary outcomes, it was hypothesized as follows:

QOL scores (FACT-B indices, including the expanded spirituality scale) would be higher than in either of the control conditions; and

-

Coping skills would be higher in the MBSR group than in both controls, except in the area of active behavioral coping, for which both in the NEP and MBSR groups would be higher than the UC group. This latter prediction is based on the fact that through the NEP intervention, participants are provided with a specific behavioral approach (changes in diet) to actively cope with their breast cancer.

Regarding the secondary outcomes, it was hypothesized as follows:

Indices of emotional distress (anxiety, depression, overall distress and specific SCL-90-R indices of distress) would be lower in the MBSR than in either of the control conditions at post-treatment. Likewise, indices of emotional acceptance CEC were predicted to favor the MBSR group, as nonjudgmental acceptance of emotional and physical sensations is a key tenet of mindfulness-based interventions.

Variables related to personal growth or spirituality would be higher in the MBSR than in the two control conditions. This includes the spirituality scale of the FACT-B noted above and the scales of the SOC.

Statistical methods

Outcome variables were measured on a continuous scale. Univariate statistics were performed to check for adherence to the assumptions of normality and equal variance, as well as for the detection of outliers. To test the effectiveness of randomization, χ2 analyses were conducted on the categorical variables (e.g., demographics), and t tests were performed on the continuous variables.

It was noted that there was a difference between the date of enrollment into the study (recorded as baseline) and the actual start date of the trial. An adjusted baseline-start date was created as a calculation of the 4-month anthropometric measurement date minus 4 months. The adjusted date was used to determine temporal relationships and to control for time-related dependency in analyses.

Because this was designed as an RCT, we conducted an intention-to-treat analysis before examining the more complex associations in these data. Assuming 50 subjects per randomization group and adjusting for the baseline level of the outcome measure (QOL from the FACT-B), there was 83% power (to detect a difference of 2.5 on a 28-point scale) in the functional dimension, 99% power for the social dimensions, and 92% power to detect a 7.5-point difference (on a 112-point scale) in overall QOL. In general, statistical power was >80% for all other dimensions of interest, including coping methods and strategies and SOC.

Analyses were conducted for each of the 43 dependent variables using PROC MIXED. This method of linear regression allows fitting both fixed and random effects. Analyses were conducted using both intention-to-treat (ITT), which only takes into account whether or not a subject was randomized, and post-hoc analyses in which models were fit that included information on covariates from subjects who provided data at each measurement point. Data reported for 4-month, 1- and 2-year outcomes are the least-squares means (i.e., the multivariable-adjusted mean values) obtained from the model. In the models, treatment group was fit as a categorical variable, and the baseline value of the dependent variable was fit to control for important between-group differences. Potential confounding factors were controlled by fitting covariates as fixed effects in each regression model.

Initial regression models were run both with and without outliers (i.e., >3 times the standard deviation from the mean), as it was unknown whether the extreme value was an error versus a meaningful measure of the given psychosocial factor (e.g., a subject with true depression). Unless a significant departure was detected, outliers were included in the analysis.

Stratified models were fit for subsets of the data based on baseline levels of expectation. Finally, analyses were conducted within the intervention groups to examine relationships with class attendance.

Results

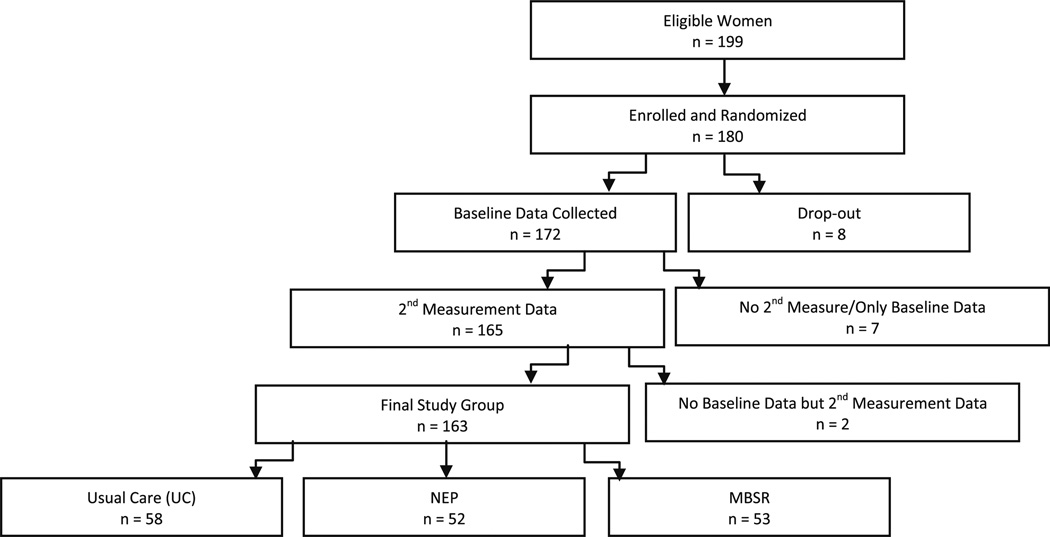

One hundred ninety-nine women were eligible for the study: 180 (91%) enrolled and were randomized. Before data collection, 8 women left the study, and of the remaining 172, 165 provided at least one additional measurement (i.e., obtained at least one 4-month, 1-year, or 2-year time point). Of these 165 women, two did not have baseline data for any of the psychosocial factors analyzed in this article. Thus, the analytic sample consisted of 163 subjects (Fig. 1). If a participant’s baseline data were absent for a particular psychosocial factor, then the subject was eliminated from the analysis for that factor.

Fig. 1.

BRIDGES study flow chart of study enrollment, randomization, and follow-up

The mean age was 49.8 ± 8.4 years, and there was no difference in age by randomization condition. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics presented by intervention group. Exploratory analyses of demographic and medical factors determined success in study randomization, with no significant differences between intervention groups. Figure 1 shows levels of completion for all stages of study completion.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in the BRIDGES study by intervention group (n = 163)

| Variable | UC |

NEP |

MBSR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 58) |

(n = 52) |

(n = 53) |

||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Education | ||||||

| High school or less | 15 | 26 | 13 | 25 | 9 | 17 |

| Some college | 16 | 28 | 22 | 42 | 21 | 39 |

| Bachelor degree | 10 | 17 | 7 | 14 | 11 | 21 |

| Graduate school | 17 | 29 | 10 | 19 | 12 | 23 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 15 | 26 | 16 | 31 | 14 | 26 |

| Stable union | 43 | 74 | 35 | 69 | 39 | 74 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 56 | 97 | 48 | 92 | 51 | 96 |

| Other | 2 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

| Employment status | ||||||

| No | 14 | 24 | 8 | 15 | 10 | 19 |

| Part-time | 10 | 17 | 10 | 19 | 14 | 26 |

| Full-time | 34 | 59 | 34 | 65 | 29 | 55 |

| Menopausal status | ||||||

| Premenopausal | 18 | 31 | 21 | 40 | 20 | 38 |

| Postmenopausal | 40 | 69 | 31 | 60 | 33 | 62 |

| Stage of disease | ||||||

| Stage I | 30 | 52 | 31 | 60 | 29 | 55 |

| Stage II | 28 | 48 | 21 | 40 | 24 | 45 |

| ER status | ||||||

| Positive | 34 | 65 | 35 | 76 | 37 | 82 |

| Negative | 18 | 35 | 11 | 24 | 8 | 18 |

| Tamoxifen use | ||||||

| Yes | 22 | 39 | 19 | 38 | 27 | 56 |

| No | 34 | 61 | 31 | 62 | 21 | 44 |

| Chemotherapy use | ||||||

| None | 24 | 46 | 20 | 42 | 22 | 47 |

| Before the study | 21 | 40 | 23 | 48 | 18 | 38 |

| During the study | 7 | 13 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 15 |

| Radiation before study | ||||||

| None | 11 | 19 | 14 | 29 | 14 | 28 |

| Before the study | 32 | 56 | 21 | 43 | 24 | 48 |

| During the study | 14 | 25 | 14 | 29 | 12 | 24 |

| Time since diagnosis | ||||||

| 0–6 months | 20 | 35 | 12 | 26 | 14 | 27 |

| 7–12 months | 13 | 23 | 14 | 30 | 16 | 31 |

| 12+ months | 24 | 42 | 21 | 45 | 21 | 41 |

Because of our very high rates of study completion, ITT and post-hoc analyses (Table 2) produced essentially similar results. These were the only differences observed in the ITT analyses: (1) a significant difference between MBSR and NEP at the 2-year point (P = 0.04) on active cognitive coping; and (2) the difference between MBSR and NEP at the 4-month point on SCL-90-R-Depression became marginally significant (P = 0.06 as opposed to P = 0.05 in the multivariable model). Table 2 presents comparisons of major study outcomes that differ significantly across intervention/control groups. At 4 months, patients in the MBSR intervention group had significantly greater overall improvement than UC and NEP controls on a number of outcomes (Online Resource 1). In terms of primary outcome measures, MBSR participants had improvements from baseline in the spirituality subscale of the FACT-B, resulting in large differences from both the UC and NEP, and exhibited more active cognitive coping (in comparison to UC), with trends toward more active behavioral coping (in comparison to UC) and less avoidance coping (in comparison to NEP). Other between-group contrasts that emerged as marginally or significantly better in the MBSR group at 4 months included: depression and unhappiness (in comparison to NEP); paranoid ideation and anger (in comparison to UC); and hostility, meaningfulness, anxiety, and emotional control (in comparison to both).

Table 2.

Description of significant (P ≤ 0.05) and marginally significant (0.05< P ≤ 0.10) MBSR outcomes by intervention/control group comparison

| 4-Months | 12-Months | 24-Months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FACTa-Spirituality | MBSR (8.9 ± 0.3) | MBSR (8.8 ± 0.3) | |

| UC (7.6 ± 0.3) | NEP (7.6 ± 0.4) | ||

| NEP (7.3 ± 0.4) | |||

| DWIb-Active behavioral coping | MBSR (62.5 ± 1.3) | MBSR (62.4 ± 1.3) | |

| UC (59.2 ± 1.2)‖ | UC (56.8 ± 1.3) | ||

| DWI-Active cognitive coping | MBSR (63.5 ± 1.1) | ||

| UC (59.2 ± 1.0) | |||

| DWI-Avoidance coping | MBSR (25.9 ± 0.8) | ||

| NEP (28.1 ± 0.8)‖ | |||

| SCL-90c-Depression | MBSR (0.41 ± 0.07) | ||

| NEP (0.61 ± 0.07) | |||

| SCL-90-Hostility | MBSR (0.14 ± 0.05) | ||

| UC (0.33 ± 0.05) | |||

| NEP (0.29 ± 0.05) | |||

| SCL-90-Paranoid ideation | MBSR (0.15 ± 0.05) | ||

| UC (0.30 ± 0.05) | |||

| SOCd-Comprehensibility | MBSR (51.2 ± 1.4) | ||

| UC (55.5 ± 1.3) | |||

| SOC-Meaningfulness | MBSR (46.8 ± 1.0) | ||

| UC (43.7 ± 1.0) | |||

| NEP (43.5 ± 1.1) | |||

| CECe-Anger | MBSR (13.9 ± 0.5) | ||

| UC (15.2 ± 0.5)‖ | |||

| CEC-Anxiety | MBSR (13.9 ± 0.6) | MBSR (14.8 ± 0.6) | |

| UC (16.0 ± 0.6) | UC (± 0.6) | ||

| NEP (16.2 ± 0.6) | |||

| CEC-Unhappiness | MBSR (13.7 ± 0.6) | MBSR (13.6 ± 0.6) | |

| NEP (15.5 ± 0.6) | UC (15.6 ± 0.6) | ||

| CEC-Total control | MBSR (41.5 ± 1.5) | MBSR (42.5 ± 1.5) | |

| UC (46.4 ± 1.4) | UC (47.1 ± 1.5) | ||

| NEP (46.8 ± 1.5) |

All are significant except those indicated by ‖ which are marginally significant

FACT breast cancer version of the functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT-B) [29–32], including additional spirituality items

DWI dealing with illness questionnaire [33]

SCL-90 symptom checklist-90-Revised [36]

Marginally significant (i.e., 0.05< P ≤ 0.10)

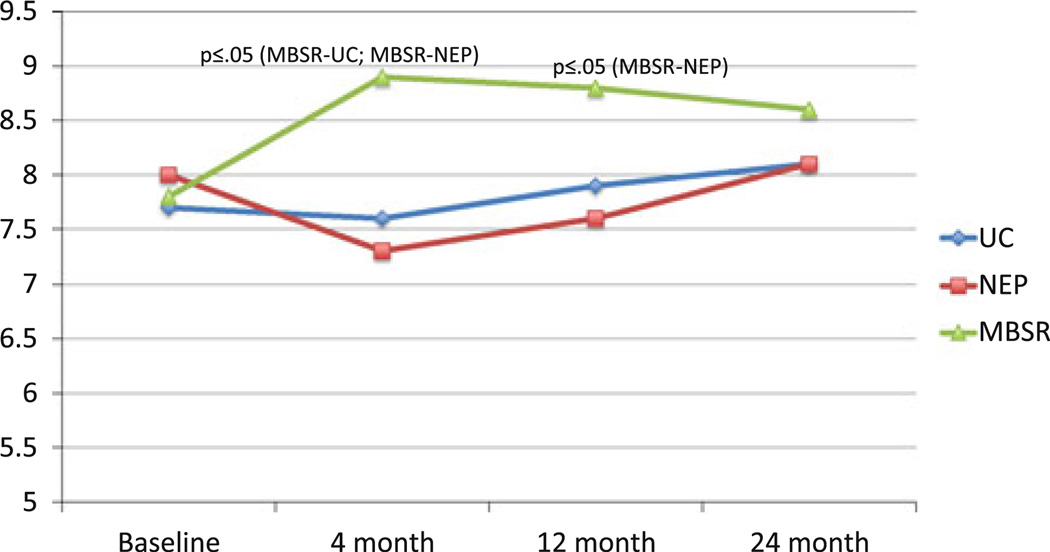

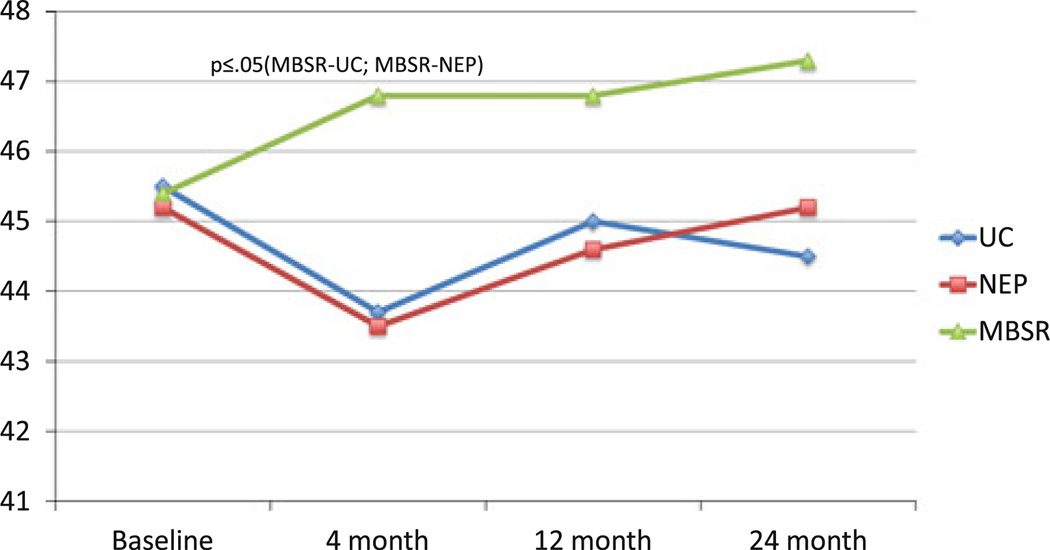

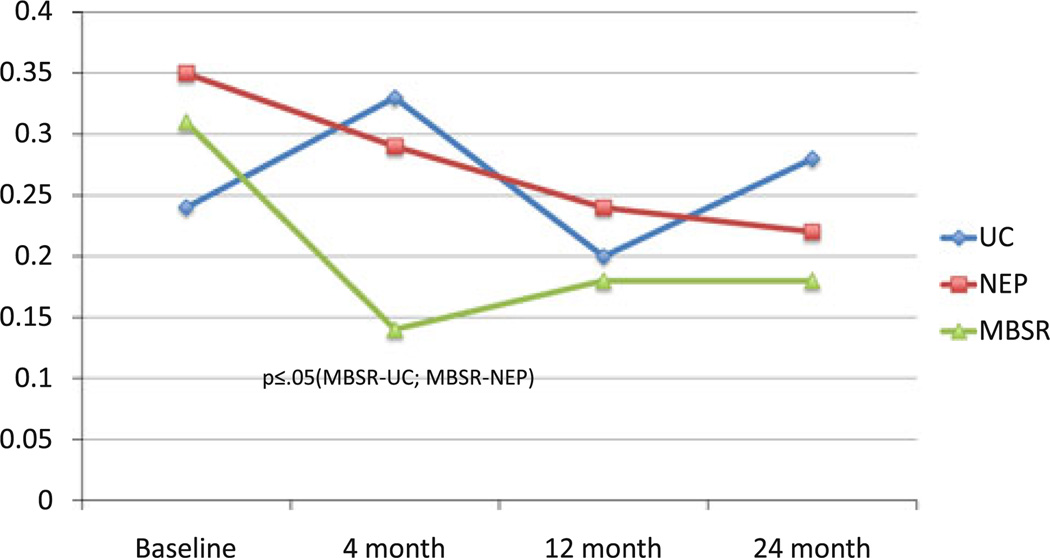

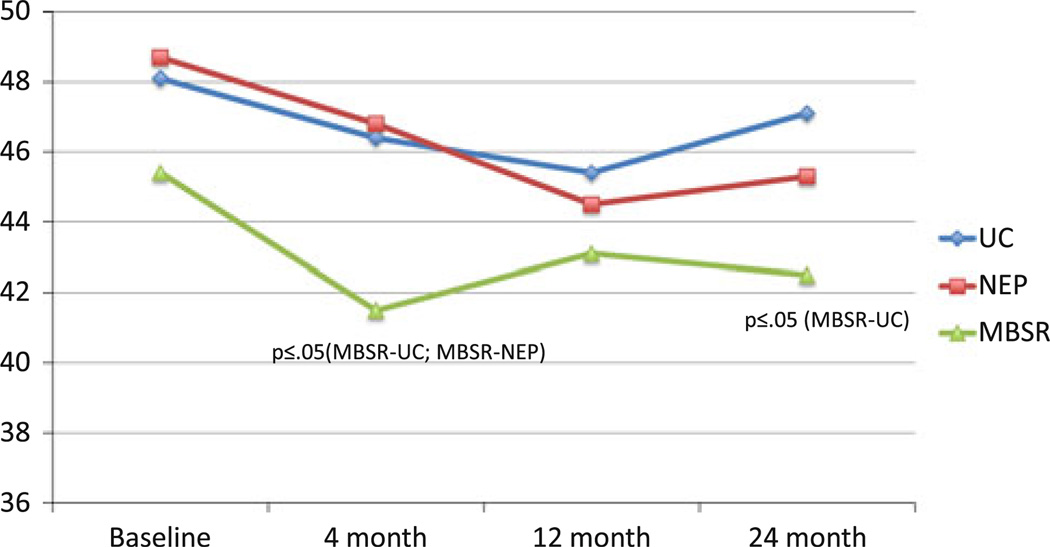

Though similar to what was observed at 4 months, at 12 months (Table 2), active behavioral coping scores decreased in UC, which resulted in an even larger significant difference compared to MBSR. At 12 months, the following were no longer significant: active cognitive coping, depression, hostility, paranoid ideation, meaningfulness, anxiety, unhappiness, and control. At 24 months, the differences were further attenuated, with the exception of patients in the MBSR intervention group having significantly better scores than UC subjects on the CEC Scale for unhappiness, anxiety, and overall emotional control. Salient results are depicted graphically in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5.

Fig. 2.

Mean FACT-B spirituality: group × time

Fig. 3.

Mean SOC meaningfulness: group × time

Fig. 4.

Mean SCL-90-R hostility: group × time

Fig. 5.

Mean CEC total emotional control: group × time

Across the different measurement scales, significant associations due to improvements in the MBSR group were most often seen at 4-months (immediately following program completion), and with the exception of spirituality, significant results at any time period were not maintained at 12 months. Overall, there was improvement in the MBSR group for the majority of the psychosocial variables, even though the changes may not have been large enough to produce a significant between-group relationship given the sample size limitations of the study.

Unlike what we had shown previously in the NEP group [45], results in the women with lower-than-average expectation of benefit were identical to those with higher-than-average expectancy (results not tabulated). Congruent with this result, when we stratified compliance data into four categories, from poor to excellent compliance, we found no association between class participation and level of expectancy for study groups.

Discussion

The BRIDGES results suggest that for early-stage breast cancer patients, benefits of an MBSR program include the ability to enhance acceptance (vs. avoidance or suppression) of emotional states; to reduce some, but not all, feelings of distress, such as depression, hostility, and alienation; to improve coping mechanisms and promote a more balanced regulation of emotional control; and to facilitate an increased sense of meaning and spirituality in relation to self, personal health, and recovery factors.

The results indicate that the NEP group produced improved levels of active-behavioral and cognitive coping that were not significantly different from the MBSR, and both were different from the UC group. The active-cognitive coping was contrary to our prediction, though the parallel with active-behavioral coping was hypothesized. It makes sense that a nutrition program could lead to improvements in active coping, as the knowledge and skills provided are potentially powerful tools to assist the breast cancer survivor. SCL-90-R Paranoid Ideation scores also were improved over the UC group and were no different from the MBSR. It seems that the social support and shared experiences from meeting weekly with other women with breast cancer has the effect of overcoming feelings of alienation. There is good evidence that the NEP was a highly credible intervention, in that the women lost an average of more than 2 kg, compared to no change in either the MBSR or UC groups [45].

The indices for which the MBSR was uniquely effective are those related to reducing hostility, promoting more acceptance of emotions and less need to control them, and promoting an enhanced sense of spirituality and meaningfulness in the wake of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. These are consistent with the results found in the other randomized MBSR/stress management breast cancer studies, though these had shorter follow-up and no attention control [13, 14, 16–18].

It is interesting that some of the beneficial psychosocial effects of the MBSR intervention were not sustained beyond the immediate post-treatment interval. It could mean that this intervention simply has relatively short-term impact, as noted in one meta-analysis [46]. However, there are possible alternative interpretations. One issue is that many of our measures are focused on general distress, which in previous research has been shown to decline on its own in the year or two after cancer treatment, at least in the absence of a disease recurrence [47]. It also is true that the baseline mean levels of distress are well below any clinical cutoffs for depression and anxiety, as we did not screen specifically to include only those breast cancer patients with high distress; and, as has previously been noted [48–50], this creates a “floor” effect that makes it difficult to show significant treatment effects. Had we included measurement scales of more cancer-specific worry, discrete distress may have been enduring, possibly showing a difference over a longer period of time. Overall, it appeared that, while emotional distress generally decreased over time in all groups, the women in the MBSR group reported their distress decreased more quickly (at the 4-month interval, rather than a year or two later). In addition, the most enduring effects were in the area of spirituality, the kind of longer-term shift in viewpoint that one would expect from an MBSR intervention, as seen in “growth through adversity” measures that have more recently been developed. Additional support for this possible interpretation is seen in the effects in acceptance of emotional states (several of the CEC subscales and total), with advantages of the MBSR intervention enduring into the 2-year follow-up.

The issue of whether the statistically significant findings are clinically significant is somewhat difficult to address. Clearly, the distress measures for which clinical norms exist (SCL-90-R) indicate that the overall group means were well below any clinical cutoffs, a phenomenon seen in other samples of women with breast cancer [51]. On the other hand, even with the low baseline distress levels, women in the MBSR group on average dropped their distress scores by nearly half on depression and by more than half on hostility. There are no meaningful clinical cutoffs on the coping, spirituality, and emotional control measures, but the changes in these measures in the MBSR (or their advantage over the controls) considerably exceeded (sometimes by many-fold) the standard deviation of those measures in this sample at baseline.

Previous analysis of the NEP intervention showed that participants anticipating high potential benefits experienced better outcomes [45]. The NEP group results continued to exhibit a correlation with outcome and expectancy in this analysis; in contrast, expectancy level did not influence the outcomes of the MBSR intervention. This finding has promising implications for wide applicability in clinical practice because even if a patient might be doubtful of the benefits of stress reduction techniques, a strong potential for positive psychosocial outcome still exists. It also serves to reinforce the validity of the study’s findings, arguing against the likelihood that the MBSR’s treatment effects are attributable to a halo-effect of positive expectancy.

A major strength of our study is that it addresses the limitations of previous studies [12] by means of a randomized controlled design with two control groups, one for usual care and one for social support as well as attention. Also, follow-up extends longer than any previous study. Clearly, the NEP provided some active beneficial components in addition to group support and attention, namely, a very specific behavioral-coping approach for making dietary changes, which showed up as significant in comparison with the UC group (principally in active-behavioral coping and alienation) and which were not different from the MBSR. The three-group comparison allows us to isolate several effects that appear to be specific to the MBSR intervention: increases in spirituality (FACT-B) and acceptance of emotional states (CEC), both of which are issues specifically targeted by MBSR that appear to be relatively enduring over the 2-year follow-up; and increased active cognitive coping and reductions in symptoms of depression and hostility, primarily in the more immediate post-treatment interval. We also assessed expectations about the likely helpfulness of benefit from the intervention. The impact of such expectation, as a potential effect modifier in these intervention trials, has rarely been evaluated. Other benefits of the study included the wide range of psychosocial variables and the expanded control for potential confounding factors.

One limitation of this study included patient demographics and restricted generalization of results from this largely middle-class sample of women with a reasonable spread of education level, but with very little ethnic diversity. Another limitation was the utilization of multiple statistical tests. We do note that, however, >5% of results favoring the MBSR were significant at the nominal type-I (α) error rate of 0.05. Most of the data, and virtually all of the psychosocial measures, are obtained from self-assessment questionnaires rather than clinician ratings, and vital status data are not available for long-term survival analysis. Finally, because several different elements, such as meditation, yoga, psycho-educational materials, and group discussion, were used in the MBSR intervention, it is not possible to identify the “key” factors responsible for benefit; the intervention has to be evaluated as a whole.

The study demonstrates several potential benefits of MBSR practices for women with early-stage breast cancer. First, the study provided continued evidence that mindfulness practices contribute to better QOL in breast cancer patients, at least during the initial stages of diagnosis and treatment. Some studies indicate that better QOL has been associated with better survival rates in cancer patients because of lower levels of disease recurrence [52, 53], which underscores the relevance of our findings. Second, our study demonstrates the emotional benefits of a psychosocial intervention in comparison to an educational group program. Third, subjects responded equally well to the mindfulness intervention regardless of expectation of benefit at the time of enrollment. This finding indicates that such MBSR interventions are helpful independent of expectation of benefit, and therefore may be more generalizable in that regard.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The BRIDGES Study was funded by grant DAMD17-94-J-4475 from the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command. Dr. Massion was supported by a Career Development Award, grant # DAMD17-94-J-4261 from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command. Dr. He´bert was supported by the Established Investigator Award in Cancer Prevention and Control K05 CA136975 from the Cancer Training Branch of the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1738-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Virginia P. Henderson, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, University of South Carolina, 3209 Colonial Drive, Columbia, SC 29203, USA Cancer Prevention & Control Program, University of South Carolina, 915 Greene Street, Suite 241-2, Columbia, SC 29208, USA.

Lynn Clemow, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, PH Room 9 Center 622 West 168th St, New York, NY 10032, USA.

Ann O. Massion, Department of Psychiatry, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Tucker Rd. NE, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA Behavioral Health Care Line, New Mexico VA Health Care System, 1501 San Pedro Dr. SE, Albuquerque, NM 87108-51545, USA.

Thomas G. Hurley, Cancer Prevention & Control Program, University of South Carolina, 915 Greene Street, Suite 241-2, Columbia, SC 29208, USA Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, 915 Greene Street, Suite 241, Columbia, SC 29208, USA.

Susan Druker, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 55 Lake Avenue North S1-859, Worcester, MA 01655-0002, USA.

James R. Hébert, Email: jhebert@mailbox.sc.edu, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, University of South Carolina, 3209 Colonial Drive, Columbia, SC 29203, USA; Cancer Prevention & Control Program, University of South Carolina, 915 Greene Street, Suite 241-2, Columbia, SC 29208, USA; Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, 915 Greene Street, Suite 241, Columbia, SC 29208, USA.

References

- 1.Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:32–63. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van’t Spijker A, Trijsburg RW, Duivenvoorden HJ. Psychological sequelae of cancer diagnosis: a metaanalytical review of 58 studies after 1980. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:280–293. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heim E, Valach L, Sheffner L. Coping and psychosocial adaptation: longitudinal effects overtime and stages in breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:408–418. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199707000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teasdale J, Segal Z, Williams J. How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfullness) training help? An information-processing analysis. J Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:25–39. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)e0011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kabat-Zinn J, Massion AO, Kristeller J, Peterson LG, Fletcher KE, Pbert L, Lenderking WR, Santorelli SF. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:936–943. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney V. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J Behav Med. 1985;8:163–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00845519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanton A. How and for whom? Asking questions about the utility of psychosocial interventions for individuals diagnosed with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):4818–4820. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyer A, Knapp-Oliver SK, Sohl SJ, Schnieder S, Floyd AH. Lessons to be learned from 25 years of research investigating psychosocial interventions for cancer patients. Cancer J. 2009;15(5):345–351. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181bf51fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moyer A, Sohl SJ, Knapp-Oliver SK, Schneider S. Characteristics and methodological quality of 25 years of research investigating psychosocial interventions for cancer patients. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35(5):475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newell SA, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ. Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: overview and recommendations for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(8):558–584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tatrow K, Montgomery GH. Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques for distress and pain in breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2006;29(1):17–27. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ledesma D, Kumano H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cancer: a meta-analysis. Psycho-oncology. 2009;18(6):571–579. doi: 10.1002/pon.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lengacher CA, Johnson-Mallard V, Post-White J, Moscoso MS, Jacobsen PB, Klein TW, Widen RH, Fitzgerald SG, Shelton MM, Barta M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for survivors of breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(12):1261–1272. doi: 10.1002/pon.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Post-White J, Moscoso MS, Shelton MM, Barta M, Le N, Budhrani P. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in post-treatment breast cancer. J Behav Med. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro SL, Bootzin RR, Figueredo AJ, Lopez AM, Schwartz GE. The efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction in the treatment of sleep disturbance in women with breast cancer: an exploratory study. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(1):85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, Yount SE, McGregor BA, Arena PL, Harris SD, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2001;20(1):20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Kazi A, Wimberly SR, Sifre T, Urcuyo KR, Phillips K, Gluck S, Carver CS. How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(6):1143–1152. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antoni MH, Wimberly SR, Lechner SC, Kazi A, Sifre T, Urcuyo KR, Phillips K, Smith RG, Petronis VM, Guellati S, et al. Reduction of cancer-specific thought intrusions and anxiety symptoms with a stress management intervention among women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1791–1797. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioural medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delacorte; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabat-Zinn J, Chapman-Waldrop A. Compliance with an outpatient stress reduction program: rates and predictors of completion. J Behav Med. 1988;11:333–352. doi: 10.1007/BF00844934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R, Sellers W. Four year follow-up of a meditation-based program for the self-regulation of chronic pain: treatment outcomes and compliance. Clin J Pain. 1987;2:159–173. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandura A. Social foundation of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A. Self efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman & Co; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A, O’Leary A, Taylor CB, Gauthier J, Gossard D. Perceived self-efficacy and pain control: opioid and nonopioid mechanisms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53:563–571. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ockene JK, Ockene IS, Quirk ME, Hebert JR, Saperia GM, Luippold RS, Merriam PA, Ellis S. Physician training for patient-centered nutrition counseling in a lipid intervention trial. Prev Med. 1995;24:563–570. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosal MC, Ebbeling CB, Lofgren I, Ockene JK, Ockene IS, Hebert JR. Facilitating dietary change: the patient-centered counseling model. J Am Dietet Assoc. 2001;101:332–341. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cella DF, Lee-Riordan D, Silberman M. Quality of life in advanced cancer: three new disease-specific measures. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1989;8:315. Abst. 1225. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cella DF, Tulsky DS. Measuring quality of life today: methodological aspects. Oncology. 1990;4(5):29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J. The functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT) Scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cella DF. Manual - functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT) scales: available from David F. Cella, Ph.D., Division of Psychosocial Oncology, Rush Cancer Center, 1725. Chicago: W. Harrison; 1992. I 60612. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Namir S, Wolcott DL, Fawzy FI, Alumbaugh MJ. Coping with AIDS: psychological and health implications. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1987;17:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Clin Consult Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R (revised version manual-1) Baltimore: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell D, Peplau L, Cutrona C. The revised UCLA loneliness scale: concurrent and discriminative validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39:472–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watson M, Greer S, Young J, Inayat Q, Burgess C, Robertson B. Development of a questionnaire measure of adjustment to cancer: the MAC scale. Psychol Med. 1988;18:203–209. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700002026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:725–733. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antonovsky A. Pathways leading to successful coping and health. In: Rosenbaum M, editor. Learned resourcefulness. New York: Springer; 1990. p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson M, Greer S. A manual for the courtauld emotional control scale (CECS) Downs Road, Sutton, Surrey SM2 5PT, England: Cancer Research Campaign Psychological Medicine Research Group, The Royal Marsden Hospital; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson M, Greer S. Development of a questionnaire measure of emotional control. J Psychosom Res. 1983;27(4):299–305. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(83)90052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hebert JR, Ebbeling CB, Hurley TG, Ma Y, Clemow L, Olendzki BC, Saal N, Ockene JK. Change in women’s diet and body mass following intensive intervention in early-stage breast cancer. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:421–431. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(1):13–34. doi: 10.2190/EUFN-RV1K-Y3TR-FK0L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knobf MT. Clinical update: psychosocial responses in breast cancer survivors. Sem Oncol Nurs. 2011;27(3):e1–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coyne JC, Lepore SJ, Palmer SC. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: evidence is weaker than it first looks. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32(2):104–110. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3202_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linden W, Satin JR. Avoidable pitfalls in behavioral medicine outcome research. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(2):143–147. doi: 10.1007/BF02879895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheard T, Maguire P. The effect of psychological interventions on anxiety and depression in cancer patients: results of two meta-analyses. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(11):1770–1780. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coyne JC, Palmer SC, Shapiro PJ, Thompson R, DeMichele A. Distress, psychiatric morbidity, and prescriptions for psychotropic medication in a breast cancer waiting room sample. Gen Hospital Psychiatry. 2004;26(2):121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gruber BL, Hersh SP, Hall NRS, Waletzky LR, Kunz JF, Carpenter JK, Kverno KS, Weiss SM. Immunological responses of breast cancer patients to behavioral interventions. Biofeedback Self Regul. 1993;18(1):1–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00999510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greer S, Morris T, Pettingale KW, Haybittle JL. Psychological response to breast cancer and 15-year outcome. Lancet. 1990;1:49–50. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watson M. Psychosocial intervention with cancer patients: a review. Psychol Med. 1983;13:839–846. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700051552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.