Background: Osteocalcin (OC) and matrix Gla protein (MGP) are evolutionarily related proteins present in bone matrix.

Results: Sturgeon OC exhibits structural and expression/accumulation features similar to MGP.

Conclusion: Data support the hypothesis that OC originated from MGP, and sturgeon protein represents an ancestral form of OC.

Significance: This work provides new insights into the evolution of bone Gla proteins and vertebrate bone tissue.

Keywords: Animal Models, Bone, Cartilage, Evolution, Extracellular Matrix Proteins, Matrix Gla Protein, Osteocalcin, Vitamin K-dependent Proteins

Abstract

Osteocalcin (OC) and matrix Gla protein (MGP) are considered evolutionarily related because they share key structural features, although they have been described to exert different functions. In this work, we report the identification and characterization of both OC and MGP from the Adriatic sturgeon, a ray-finned fish characterized by a slow evolution and the retention of many ancestral features. Sturgeon MGP shows a primary structure, post-translation modifications, and patterns of mRNA/protein distribution and accumulation typical of known MGPs, and it contains seven possible Gla residues that would make the sturgeon protein the most γ-carboxylated among known MGPs. In contrast, sturgeon OC was found to present a hybrid structure. Indeed, although exhibiting protein domains typical of known OCs, it also contains structural features usually found in MGPs (e.g. a putative phosphorylated propeptide). Moreover, patterns of OC gene expression and protein accumulation overlap with those reported for MGP; OC was detected in bone cells and mineralized structures but also in soft and cartilaginous tissues. We propose that, in a context of a reduced rate of evolution, sturgeon OC has retained structural features of the ancestral protein that emerged millions of years ago from the duplication of an ancient MGP gene and may exhibit intermediate functional features.

Introduction

Osteocalcin (OC),3 also known as bone Gla protein, and matrix Gla protein (MGP) are characterized by the presence of Gla residues resulting from the post-translational vitamin K-dependent γ-carboxylation of specific glutamates, which confer on these proteins their ability to bind calcium and calcium/phosphate crystals, such as hydroxyapatite (1–4). OC is a small secreted protein of 5–6 kDa synthesized as a prepropeptide, originally isolated from organic matrix of bovine bone (5) and considered specific for vertebrate calcified structures, where it is secreted mainly by osteoblasts and odontoblasts. Depending on the species, OC contains 3–4 Gla residues located within a conserved domain in the central part of the mature protein (6, 7). It has been proposed that OC has a pivotal role in controlling tissue mineralization mechanisms (8–10), and Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy studies have shown that OC is required for the correct maturation of hydroxyapatite in mammalian bone (8). More recently, it has also been proposed that the undercarboxylated form of OC may function as a hormone and be involved in regulating glucose metabolism and fat mass as well as murine and human fertility (11–13).

MGP is a 10-kDa secreted protein containing a phosphorylated domain, a γ-glutamyl carboxylase recognition site, and 4–5 Gla residues; it was originally purified from the organic matrix of mammalian bone (2) and later identified in the organic matrix of bone and calcified cartilage from other mammals (14–16), an amphibian (17), and bony and cartilaginous fish (18, 19). It is produced and secreted mainly by vascular smooth muscle cells (20) and chondrocytes (21) and significantly accumulated in bone, cartilage, tooth cementum, and soft tissues, such as kidney, respiratory system, and heart (2, 14, 17, 19, 22–24). Although the molecular mechanism of MGP action remains poorly understood, numerous studies have reported a major role in the inhibition of soft tissue calcification. The spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking MGP (25) and phenotype rescue after restoration of MGP expression (26), together with abnormal cartilage and artery calcification in patients with loss-of-function mutations in the MGP gene (27), are evidence suggesting a role in the prevention of ectopic mineralization. In addition to the 4–5 Gla residues believed to be important in binding Ca2+ and calcium crystals, MGP contains phosphorylated serine residues that may further regulate its activity, and it was shown that both γ-carboxylation and serine phosphorylation contribute to MGP function as a calcification inhibitor (3).

Although the two proteins share several structural motifs, they have different functions and play different roles in tissue mineralization (26). Based on evident similarities in protein structure and gene organization, OC and MGP have been considered to be evolutionarily related; a current hypothesis is that the OC gene appeared from a duplication of an ancestral MGP gene that may have occurred ∼380 million years ago (before the branching of cartilaginous fish). The duplicated gene would have diverged throughout vertebrate evolution to give the modern OC gene described in the literature. It has also been speculated that the appearance of MGP and OC would be concomitant or followed by the emergence of cartilage and bone structures, respectively (7).

With more than 32,000 species, fish form the most diverse group of vertebrates; they appeared ∼395 million years ago, and lobe-finned fish are considered to be the ancestors of all terrestrial vertebrates. Fish, in particular ray-finned fish, have been shown to be suitable models not only to study OC and MGP proteins but also to provide key insights contributing to understanding of how these proteins and calcified tissues have evolved (7, 19, 28, 29). Among ray-finned fish, the Chondrostei (Acipenseriformes (e.g. sturgeons) and Polypteriformes (e.g. bichirs)) occupy a specific position; their endoskeleton is primarily cartilaginous, whereas their exoskeleton is composed of bony plates. They represent one of the oldest groups of bony fish and have undergone an exceptionally slow evolution. It has been proposed that their skeleton would represent the ancestral state of the vertebrate skeleton (30). Based on this proposition, we speculated that mineral-binding Gla proteins from Chondrostei, in particular osteocalcin, may have also undergone a slow rate of evolution and thus resemble the ancestral form of vertebrate proteins. We isolated MGP and osteocalcin from mineralized tissues of the Adriatic sturgeon Acipenser naccarii and determined their primary protein structure, patterns of gene expression, and sites of protein accumulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Biological Material

Specimens of A. naccarii (Adriatic sturgeon), kindly supplied by Aquaculture Rio Frio (Granada, Spain), were kept until used at 20–22 °C in a closed circuit equipped with a biological filter and a natural photoperiod. Frozen branchial arches from adult sturgeons were also obtained from Aquaculture Rio Frio.

Collection of Mineralized Tissues

Branchial arches and ganoid plates were freed from adhering soft tissues, extensively washed in distilled water and then acetone (Merck), air-dried, and ground to powder in a mortar. Powder was washed three times with a 10-fold excess of 6 m guanidine HCl (Sigma), washed extensively with water and acetone, and air-dried.

Extraction of Mineral-bound Proteins

Mineral-bound proteins were extracted from ganoid plates and branchial arches using a 10-fold excess of 10% (v/v) formic acid for 4 h at 4 °C as described previously (17). Extracted proteins were separated from the insoluble collagenous matrix by filtration through filter paper and then dialyzed at 4 °C against 50 mm HCl using 3,500 molecular weight tubing (Spectra/Por 3, Spectrum). Dialysis solution was changed twice a day for 2 days, and then extract was freeze-dried; dissolved in 6 m guanidine HCl, 0.1 m Tris, pH 9; and further dialyzed against 5 mm ammonium bicarbonate.

Purification of Branchial Arch Soluble Proteins

Soluble desalted protein extracts collected after ammonium bicarbonate dialysis were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the protein profile was revealed by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB; Bio-Rad) and a Gla-specific stain (DBS; Sigma-Aldrich) as described (19). Protein extracts from branchial arches were further purified by ionic exchange in a 1-ml RESOURCETM Q column (GE Healthcare). Bound proteins were eluted with a continuous gradient of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8) and 0.5 m NaCl. The resulting peak fractions were dialyzed against 5 mm ammonium bicarbonate and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and pure protein was identified by N-terminal sequencing analysis using an Applied Biosystems model 494 sequencer equipped with an on-line high performance liquid chromatograph for separation and detection of phenylthiohydantoin (PTH)-derivatives.

Purification of Branchial Arch Insoluble Proteins

Insoluble protein extracts from branchial arches and ganoid plates, collected after dialysis with 5 mm ammonium bicarbonate, were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and their protein profile was revealed by staining with CBB and DBS. Gla-containing proteins were further purified by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) from a branchial arch preparation (31), transferred to PVDF membranes, and identified by N-terminal sequencing as described above.

Western and Dot Blot Analysis

Aliquots of total protein were fractionated by SDS-PAGE on a 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide precast gel containing 0.1% SDS (NuPage, Invitrogen), stained with CBB and DBS as described previously (19, 31), and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences). OC and MGP proteins were detected by incubating blots overnight with the primary polyclonal antibodies against meagre Argyrosomus regius OC (ArOC) and ArMGP or against shark Galeorhinus galeus MGP (GgMGP) (28) diluted 1:100 in 5% (w/v) nonfat dried milk powder in TBST (15 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 8). Proteins phosphorylated on serine residues were detected using a specific anti-phosphoserine rabbit polyclonal antibody (Invitrogen). Alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG or peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Sigma) diluted 1:30,000 in TBST were used as secondary antibodies. Visualization of immunoreactive bands was achieved using nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphatase substrate solution (Calbiochem) as described (19, 32) or the Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Plus kit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

RNA and DNA Preparation

Total RNA was extracted from adult sturgeon tissues (including bone, cartilage, and major soft tissues) as described previously (31). RNA integrity was checked by agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis, and concentration was determined by spectrophotometry at 260 nm. Sturgeon genomic DNA was extracted from muscle as described previously (31).

cDNA Cloning

Based on alignments of known OC sequences and on the N-terminal sequence of sturgeon MGP protein, degenerated forward primers OC_1F and MGP_1F were designed and used in combination with the universal adapter primer to PCR-amplify the 3′-end of sturgeon OC and MGP cDNAs from ganoid plates and branchial arch reverse-transcribed RNA (using MMLV-RT; Invitrogen), respectively. The 5′-ends of those cDNAs were amplified by RACE-PCR using specific reverse primers OC_1R and MGP_1R and a sturgeon Marathon cDNA library (Clontech) prepared previously (31). Sequences of all PCR primers used in this study are presented in Table 1. All PCR products were cloned into pCRIITOPO (Invitrogen) and sequenced on both strands.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for PCR and qPCR amplifications

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| cDNA cloning | |

| OC_1F | GATGGAYGCYGCCTACACSRCCTACTA |

| OC_1R | CGGGGATTGGTCCGAAGTGTTTTTGATA |

| MGP_1F | GAYGARTCNTTYGAYTCNGGNGARGAY |

| MGP_1R | GCTCTTGTACCGTTCCATTAACCTCTCAT |

| Gene cloning | |

| OC_2F | CGAGAGAGACAGAGAAGACACTAGA |

| OC_2R | TGCGAGATTTACTGGAGCAAAAGTC |

| OC_3F | CTCCTCTCCCTCATCACCCTCGCTCTG |

| OC_4R | CAGCCACTGACTCACTGTGTGACCCTG |

| qPCR | |

| OC_RT1F | TCTGACGCTGTTTTGCTCCAGTAAATCTCG |

| OC_RT1R | CGTTTCAGGGAAAATACCCAAAAGCAATA |

| MGP_RT1F | TTTATGAATCCCTACAGTGCGAACTCCT |

| MGP_RT1R | GTAGCGACGGGCGAAGCGGTCA |

| GAPDH_RT1F | TCTGACTTCAATGGAGACACCCGCT |

| GAPDH_RT1R | CACGAGGTCCACGACTCTGTTGCTGTA |

| HPRTI_RT1F | TGAAGAGCCCTGACCACGCCGA |

| HPRTI_RT1R | CGTGCCACCAAGAAACAGCAAATACAA |

In Silico Analysis

Deduced amino acid sequences were aligned using M-Coffee multiple-sequence alignment software (33), and manual adjustments were made to improve alignments. Signal peptides and phosphorylation sites were predicted using SignalP version 3.0 (34) and NetPhos version 2.0 (35), respectively.

Gene Cloning

The sturgeon OC gene was PCR-amplified from GenomeWalker libraries prepared as suggested by the manufacturer (Clontech) or from genomic DNA using gene-specific primers designed based on cDNA sequence and intronic sequences as they became available. Fragments, including partial exon 1 and intron 1 and partial intron 3 and exon 4, were amplified from GenomeWalker libraries StuI and PvuII using OC_2F and OC_2R specific primers and AP1, respectively. The overlapping fragment between exon 1 and intron 3 was obtained using genomic DNA as template and primers OC_3F and OC_4R.

Measurement of Relative Gene Expression by Quantitative Real-time PCR

One microgram of total RNA was treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega) and reverse-transcribed at 37 °C with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), using either gene-specific reverse primers or universal dT adapter. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using the iCycler iQ apparatus (Bio-Rad) and primer sets OC_RT1F/OC_RT1R to amplify sturgeon OC, GAPDH_RT1F/GAPDH_RT1R to amplify sturgeon GAPDH, HPRTI_RT1F/HPRTI_RT1R to amplify sturgeon HPRTI, and MGP_RT1F/MGP_RT1R to amplify sturgeon MGP. PCRs, set up in duplicates, were as follows: 2 μl of RT diluted 1:10, 8 μl of primer mix (final concentration of each primer was 0.2 μm) and 10 μl of Absolute QPCR SYBR Green fluorescein mix (ABgene). PCRs were submitted to an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 15 min and 55 cycles of amplification (one cycle was 30 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 68 °C). Fluorescence was measured at the end of each extension cycle in the FAM-490 channel. Levels of gene expression were calculated using the comparative method (ΔΔCt) and normalized using gene expression levels of GAPDH or HPRTI housekeeping genes. qPCR values are presented as the mean of triplicates ± S.D. Sequences of all qPCR primers used in this study are presented in Table 1.

Histological Sample Preparation

Samples were collected as described previously (31) and included either in paraffin or in Historesin Plus (Leica Microsystems). Routine staining methods using Harris hematoxylin-eosin (CI 75290, Sigma) and Alcian Blue 8GX (CI 74240, Sigma), pH 2.5, were carried out in adjacent sections. Mineral deposits were detected through von Kossa's and Alizarin red S staining (23).

In Situ Hybridization

A 725-bp fragment of sturgeon OC cDNA (spanning from nucleotide 468 to the 3′-end) cloned into pCRII-TOPO was either linearized with ApaI and transcribed with SP6 RNA polymerase to generate antisense riboprobe or linearized with HindIII and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase to generate sense riboprobe. Both probes were labeled with digoxigenin using RNA labeling kit (Roche Applied Science). Sections were digested with 40 μg/ml proteinase K (Sigma) in 1× PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma) for 45 min and hybridized at 68 °C overnight. Hybridization and signal detection were performed as described previously (31, 32). Negative controls were performed with sense probes.

Immunolocalization

Immunohistochemical staining experiments were performed using paraffin- and HistoResin Plus-embedded tissue sections as described previously (19, 32). Briefly, the endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 in Coon's buffer (0.1 m Veronal, 0.15 m NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100) for 15 min, and nonspecific antibody binding was blocked with 0.5% (w/v) BSA. Incubation with affinity-purified polyclonal ArOC primary antibody (28), diluted 1:100, and anti-serum GgMGP antibody (28), diluted 1:250, was performed overnight in a humidified chamber at room temperature. Peroxidase activity was detected using peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Sigma) and 0.025% 3,3-diaminobenzidine (Sigma) as described previously (19, 32). Immunofluorescence was detected using a procedure similar to that described above, where incubation with FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Sigma) was done in a humidified dark chamber. For negative controls, primary antibody was replaced with both normal rabbit serum and BSA in Coon's buffer.

RESULTS

Identification of an Osteocalcin with MGP Features in Adriatic Sturgeon

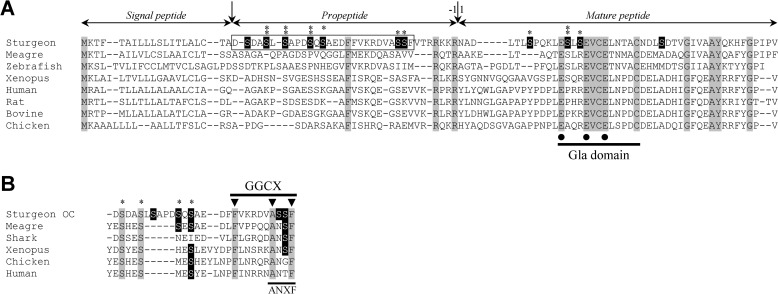

The sturgeon osteocalcin cDNA was obtained through a combination of standard PCR and RACE-PCR amplifications. The longest transcript spanned 1,192 bp (accession number EF413584) and contained a 303-bp open reading frame encoding a 100-aa peptide with high similarity with OC already characterized in other species (Fig. 1A). Analysis of deduced amino acid sequence revealed (i) a 20-aa signal peptide, (ii) a 34-aa propeptide containing a putative recognition site for γ-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX) and a furin-like cleavage motif (RKKR), and (iii) a 46-aa mature protein containing three glutamic acids at sites known to be γ-carboxylated in other OCs and two cysteine residues essential to the formation of a disulfide bond (Fig. 1A and Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the N terminus of sturgeon OC did not align very well with that of other OCs, and numerous serine residues (11 residues) occurred within the propeptides and mature peptides; nine of them were predicted to be phosphorylated, in particular those at positions 25, 27, 31, 33, and 67, which had a score above 0.96 (Fig. 1A). Serine phosphorylation is a key feature of MGP, and we decided to further investigate this striking similarity. Alignment of the sturgeon OC propeptide with the N terminus of vertebrate MGP (Fig. 1B) revealed that four of these putative phosphoserines aligned with serines previously shown to be phosphorylated in MGP proteins (14, 17). A motif sharing some homology with the MGP-specific ANXF cleavage site was also identified within the propeptide of sturgeon OC, upstream of the OC-specific RKKR furin cleavage site (Figs. 1B and 2A). Altogether, these observations show that the protein deduced from sturgeon OC cDNA combines domains and motifs present in both MGP and OC proteins (Fig. 2A), which can eventually originate (i) a typical OC if the propeptide is cleaved by the furin-like enzyme or (ii) an MGP/OC hybrid protein if the protein precursor is only cleaved at the signal peptide cleavage site.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of the Adriatic sturgeon OC sequence with other known OCs (A) and with the N terminus of known MGPs (B). A, OC sequences from ray-finned fish (sturgeon, meagre, and zebrafish), amphibian (Xenopus), mammals (human, rat, and bovine), and bird (chicken) were aligned using M-Coffee. The first amino acid of predicted mature peptide is numbered as 1. Residues 100% conserved are highlighted in gray and serine residues in sturgeon OC are highlighted in black. Asterisks indicate predicted phosphorylation sites, and those marked with double asterisks have a probability score above 0.96. Black dots indicate 100% conserved Gla residues. Vertical arrows indicate cleavage sites after signal peptide and propeptide. GenBankTM accession numbers for OC sequences are as follows: AF459030 (meagre A. regius); AY178836 (zebrafish, D. rerio); AF055576 (X. laevis); NP954642 (human, H. sapiens); NP038200 (Norway rat, Rattus norvegicus); NP776674 (bovine, Bos taurus); NM205387 (chicken, G. gallus). B, partial propeptide sequence of sturgeon OC (rectangle in A) was aligned with N-terminal sequences of known MGPs using M-Coffee. Residues 100% conserved are highlighted in gray, and serine residues in sturgeon and partially conserved in other species are highlighted in black. Asterisks indicate phosphorylation sites reported in MGP. ANXF, the MGP proteolytic cleavage site. Black arrowheads, amino acids known to be essential for γ-glutamyl carboxylase binding (GGCX). GenBankTM accession numbers for MGP sequences are as follows: AF334473 (meagre, A. regius); P56620 (blue shark G. galeus); AF055588 (X. laevis); Y13903 (chicken, G. gallus); BC005272 (human, H. sapiens).

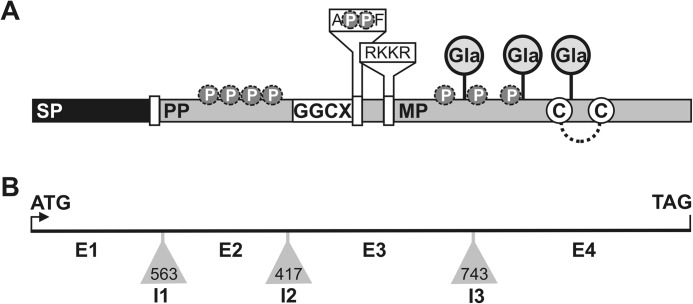

FIGURE 2.

Structural organization of Adriatic sturgeon OC protein (A) and gene (B). A, cDNA-deduced OC sequence. SP, signal peptide; PP, propeptide; MP, mature protein. Circled P, phosphorylation sites predicted by NetPhos version 2.0; circled Gla, putative γ-carboxyglutamic acid residues; dashed line, intramolecular disulfide bond; circled C, conserved cysteine residues; GGCX, γ-glutamyl carboxylase recognition site; RKKR, furin-like proteolytic cleavage site; APPF, motif similar to MGP-specific proteolytic cleavage site ANXF, where PP corresponds to putative phosphorylated serine residues in sturgeon OC. B, organization of OC gene (between initiation (ATG) and termination (TAG) codons). Exons 1–4 (E1–E4) are represented by solid lines, and introns 1–3 (I1–I3) are shown by gray triangles (intron size (bp) is indicated inside each triangle).

The sturgeon OC gene was later cloned through a combination of gene walking and genomic PCRs (accession number EF413587). It exhibited a structure identical to other OC genes with four coding exons and three introns inserted in phase 1 (introns 1 and 2) and phase 2 (intron 3). Following the typical pattern of OC genes, (i) exon 1 encodes the signal peptide and its cleavage site; (ii) exon 2 encodes part of the propeptide; (iii) exon 3 encodes the remaining propeptide, containing the GGCX recognition and furin-like cleavage sites, and part of the mature protein, containing one Gla residue; and (iv) exon 4 encodes the remaining mature protein, containing two Gla residues and the two conserved cysteines (Fig. 2B). Although these structural data are indicative of an OC gene, this is not conclusive because OC and MGP genes exhibit a very similar molecular structure (e.g. similar phase of introns and length of exons) (7), only differing in the presence of an extra intron and exon positioned in the 5′-UTR of fish and amphibian MGP genes (36, 37). The absence, in the sturgeon OC gene, of these extra sequences typical of all fish MGP genes analyzed to date further indicates that this is indeed the sturgeon OC gene.

Identification of Sturgeon Calcified Skeletal Structures

Histomorphological characterization of ganoid plates (GP) (Fig. 3A), branchial arches (BA) (Fig. 3B), and vertebra (Fig. 3C) tissues was performed through routine hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), von Kossa, Alizarin red, and Alcian blue staining procedures. H&E staining of GP sections revealed the presence of osteocyte-like cells (Oc) (Fig. 3A, 1) entrapped within a calcified matrix, as demonstrated by positive staining with von Kossa (Fig. 3A, 2) and Alizarin red (Fig. 3A, 3), and the periosteum (Pt) surrounding the mineralized matrix (Fig. 3A, 1), which was positively stained with Alcian blue (Fig. 3A, 4) and negatively stained with von Kossa (Fig. 3A, 2). In BA, calcification was only detected associated with the gill rakers (Fig. 3B, 1 and 2), whereas mature chondrocytes (MC) were found enclosed in a cell-rich hyaline cartilage at the basis of BA filaments (Fig. 3B, 3) positively stained with Alcian blue (Fig. 3B, 4) and negatively stained with both von Kossa and Alizarin red (results not shown). Identified sturgeon vertebra structures were dorsal and ventral cartilages (hyaline cartilage; HC), a thick notochord sheath (NS), the spinal cord (SC), and the perichondrium (Pc) (Fig. 3C, 1). Hyaline cartilage was found to be composed of mature chondrocytes immersed in a homogeneously hyaline cartilage, positively stained with Alcian blue (Fig. 3C, 2), surrounded by immature chondrocytes and the perichondrium (results not shown). The vertebral centra were found to be entirely cartilaginous without positive staining with either von Kossa or Alizarin red (results not shown).

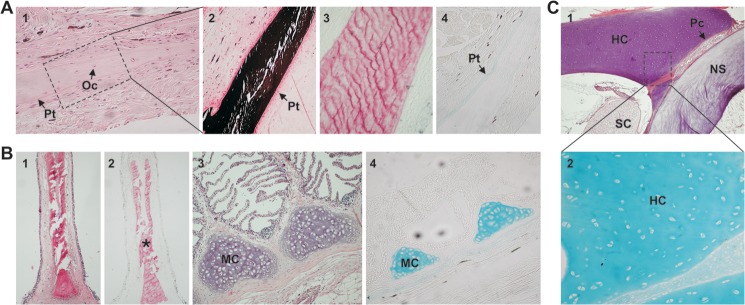

FIGURE 3.

Detection of mineralized/non-mineralized structures in skeletal tissues of a young adult sturgeon. A, histological characterization of ganoid plate sections through staining with hematoxylin-eosin (1), von Kossa (2), Alizarin red (3), and Alcian blue (4). Oc, osteocytes; Pt, periosteum. B, histological characterization of branchial arch sections through staining with hematoxylin-eosin (1 and 3), Alizarin red (2), and Alcian blue (4). MC, mature chondrocytes. *, mineralized matrix of gill rakers. C, histological characterization of vertebra sections through staining with hematoxylin-eosin (1) and Alcian blue (2). HC, hyaline cartilage; Pc, perichondrium; SC, spinal cord; NS, notochord sheath. Magnification is ×10 in A (1) and B (3 and 4); ×20 in A (2–4), B (1 and 2), and C (2); and ×5 in C (1).

Identification of Sturgeon OC Protein in the Mineral Phase of Skeletal Tissues

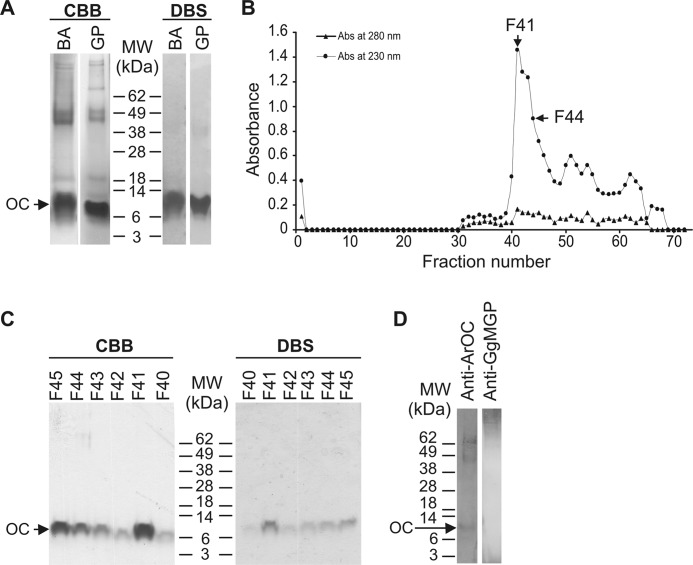

To further determine which protein(s) related to the sturgeon OC gene would accumulate in the mineral phase of sturgeon skeletal tissues, matrix proteins of sturgeon calcified cartilage and bone were acid-extracted from branchial arches and ganoid plates, respectively. Dialysis of acid extracts against ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8) originated a soluble and an insoluble protein extract. Although OC-related peptides were expected to be present in the ammonium bicarbonate-soluble extract (OC is highly soluble in water at neutral pH), MGP-related peptides usually precipitate from the ammonium bicarbonate solution because they are poorly soluble in aqueous solutions at pH 7–8. Protein extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the presence of Gla-containing proteins was evaluated through DBS staining. The migration profile of soluble extracts from BA and GP were similar and exhibited a major protein band positive for DBS and with an apparent molecular mass of ∼10 kDa (Fig. 4A). In order to remove high and low molecular weight contaminants, branchial arch soluble extract was further purified through ionic exchange chromatography over a RESOURCE Q column. Chromatogram profile revealed the presence of a major peak eluting at fractions 39–49 (Fig. 4B), which were dialyzed against ammonium bicarbonate and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. A single protein band of 10 kDa positive for DBS was detected in all fractions (Fig. 4C), confirming the successful purification of a Gla-containing protein. N-terminal sequence of the protein present in fraction 44 was determined, and the first 19 aa were identified as NADLTLSPQKLXSLSXVXX (no PTH-derivatives were detected at positions 12, 16, 18, and 19). This sequence was in total agreement with the protein sequence deduced from sturgeon OC cDNA and indicated a proteolytic cleavage at the furin-like site (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, DBS staining of purified protein and the absence of identifiable PTH-derivatives at positions 12, 16, and 19, which are Glu residues in the cDNA-deduced protein, strongly suggested the presence of Gla residues at these positions in sturgeon osteocalcin. The absence of an identifiable PTH-derivative at position 18 further confirmed the presence of the cysteine residue previously found at this position in cDNA-deduced protein.

FIGURE 4.

Extraction (A), purification (B and C), and characterization (D) of Adriatic sturgeon OC from the mineral phase of adult calcified tissues. A, protein profile of crude soluble extracts of the mineral phase of sturgeon BA and GP and detection of Gla-containing proteins revealed through CBB and DBS staining, respectively. B, purification of proteins present in BA soluble extract through ion exchange chromatography performed over a RESOURCE Q column. The protein profile was obtained by measuring absorbance (Abs) of effluent fractions at 280 nm (black triangles) and 230 nm (black circles). C, protein profile of ion exchange chromatography fractions revealed through CBB and DBS staining. D, Western blot analysis of proteins present in branchial arch soluble extract using anti-ArOC and anti-GgMGP antibodies. Arrows, OC migration position. The profile of SeeBlue prestained molecular weight marker (MW) is indicated beside the gel pictures.

Polyclonal antibodies against ArOC and against GgMGP (28) were tested for cross-reactivity with sturgeon OC through Western blotting of soluble extracts. An immunoreactive band with an apparent molecular mass of ∼10 kDa was detected in branchial arch soluble extract by anti-ArOC antibody (Fig. 4D), whereas anti-GgMGP antibody did not recognize any band (Fig. 4D), indicating the absence of MGP in this soluble extract and confirming antibody specificity. In addition, dot blot analysis of the ionic exchange chromatography fraction 44, previously identified as OC by N-terminal sequence analysis, showed a positive signal with anti-ArOC (results not shown), further confirming the osteocalcin identity of sturgeon soluble protein.

Identification of Sturgeon MGP Characterized by a High Gla Content

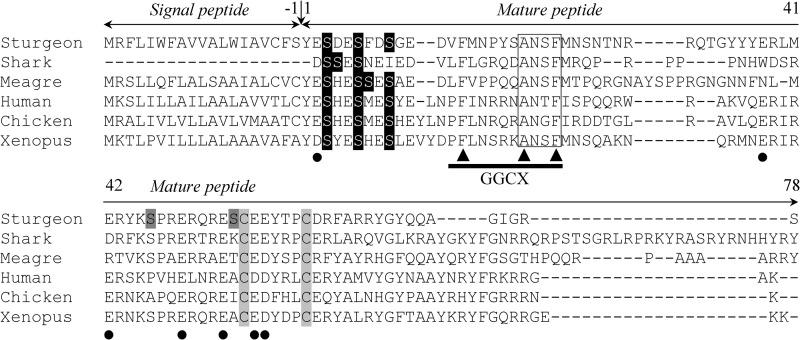

The insoluble fraction of branchial arch acid extracts, shown previously to contain the Gla-rich protein (GRP) (31), was further purified through a combination of RP-HPLC and gel filtration chromatography and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Although GRP represents the major insoluble protein and exhibits the strongest DBS staining, a second protein with a reddish coloration by DBS and an apparent molecular mass of 14 kDa was also detected (31). The N-terminal sequence of the protein present in RP-HPLC fraction 54, according to the protein profile previously published (31), was determined as YXSDESFDSGEDVFMNPYSANSFMN (no PTH-derivative was detected at position 2) and found to be similar to known MGP sequences (Fig. 5). A 14-kDa protein with a similar behavior was also detected in the insoluble extract from ganoid plates (Fig. 6A). It was more abundant in this bone-derived extract than in the previously characterized cartilage-derived extract (i.e. from branchial arches). The MGP nature of this protein was further confirmed by Western blot using anti-ArMGP and anti-GgMGP polyclonal antibodies and using MGP-containing RP-HPLC fraction 54 as a positive control. Although anti-ArMGP antibody was able to recognize MGP from RP-HPLC fraction 54, immunoreactive signal was faint and almost undetectable in insoluble crude extracts of both branchial arches (Fig. 6B) and ganoid plates (results not shown). On the contrary, anti-GgMGP antibody strongly immunoreacted with the 14-kDa protein (Fig. 6C), thus confirming the presence of MGP also in the ganoid plates. These results also showed that sturgeon MGP epitopes were better recognized by GgMGP antibody. Anti-ArOC antibody failed to detect MGP protein in branchial arch insoluble extract and RP-HPLC fraction 54 (results not shown), again showing the absence of cross-reactivity among the different Gla-containing proteins with the antibodies used and confirming their specificity. The phosphorylation status of sturgeon MGP was investigated by Western blot using an anti-phosphoserine antibody. A strong immunoreactive band corresponding to a protein of ∼14 kDa was observed in branchial arch insoluble extract (Fig. 6D), suggesting that sturgeon MGP is indeed phosphorylated. However, because serine residues at positions 3, 6, and 9, known to be phosphorylated in other species, did not give blanks in N-terminal sequence of sturgeon MGP protein, they may be only partially phosphorylated, as determined previously for meagre MGP (19). The cDNA of sturgeon MGP was later cloned through a combination of RT- and RACE-PCR amplifications using degenerated primers designed from the N-terminal sequence previously determined. The longest transcript spanned 663 bp and contained an open reading frame of 294 bp encoding a polypeptide of 97 aa (accession number HM182000). The deduced protein sequence was in full agreement with the N-terminal sequence of the mature protein purified through RP-HPLC, and its comparison with sequences in the GenBankTM database confirmed its identity as sturgeon MGP (Fig. 5). In silico analysis of MGP precursor revealed a signal peptide of 19 aa and a mature protein of 78 aa, which contains (i) five putative phosphorylated serine residues, (ii) a putative GGCX docking site, (iii) a ANSF motif, and (iv) seven possible Gla and two Cys residues (Fig. 5). Phosphorylation sites were predicted based on homology with other MGP proteins and using NetPhos version 2.0 (Fig. 5). Putative phosphoserines located in the N terminus correspond to the three serine residues previously shown to be phosphorylated in meagre MGP and conserved in most known MGP. However, the phosphorylation of serine residues in the core of the Gla domain (positions 46 and 54 in sturgeon mature MGP) has never been reported before. The stronger immunoreaction of sturgeon MGP to anti-phosphoserine antibodies (Fig. 6D), when compared with the signal obtained for meagre MGP (using a comparable amount of protein; results not shown), could indicate that these two serine residues are also phosphorylated in sturgeon protein. The absence of a PTH-derivative at position 2 of the N-terminal sequence, where a Glu residue is present in the cDNA-deduced protein sequence, may indicate the presence of a Gla residue at this position in sturgeon MGP. Furthermore, an additional six Glu residues were found in sturgeon MGP at the positions of confirmed Gla residues in other vertebrate MGPs (e.g. Homo sapiens, Gallus gallus, Xenopus laevis, Argyrosomus regius and Galeorhinus galeus; Fig. 5). These results, combined with the atypical intense coloration obtained for sturgeon MGP after DBS staining (reddish coloration), suggest a high γ-carboxylation status with seven possible Gla residues, which, if confirmed, would make sturgeon protein the most γ-carboxylated MGP.

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of sturgeon MGP sequence with other known MGPs. MGP sequences from cartilaginous fish (blue shark), teleost fish (meagre), mammal (human), bird (chicken), and amphibian (Xenopus) were aligned using M-Coffee. Numbering is indicated according to the first amino acid of the mature peptide. Serine residues known to be phosphorylated in other species are highlighted in black; serine residues predicted to be phosphorylated in sturgeon MGP are highlighted in dark gray. Conserved cysteines are highlighted in light gray. Vertical arrow, cleavage site after signal peptide; white box, ANXF sequence; black arrowheads, amino acids known to be essential for γ-glutamyl carboxylase binding (GGCX); black dots, Glu residues known to be γ-carboxylated. GenBankTM accession numbers for MGP sequences are as follows: P56620 (blue shark, G. galeus); AF334473 (meagre, A. regius); BC005272 (human, H. sapiens); Y13903 (chicken, G. gallus); AF055588 (X. laevis).

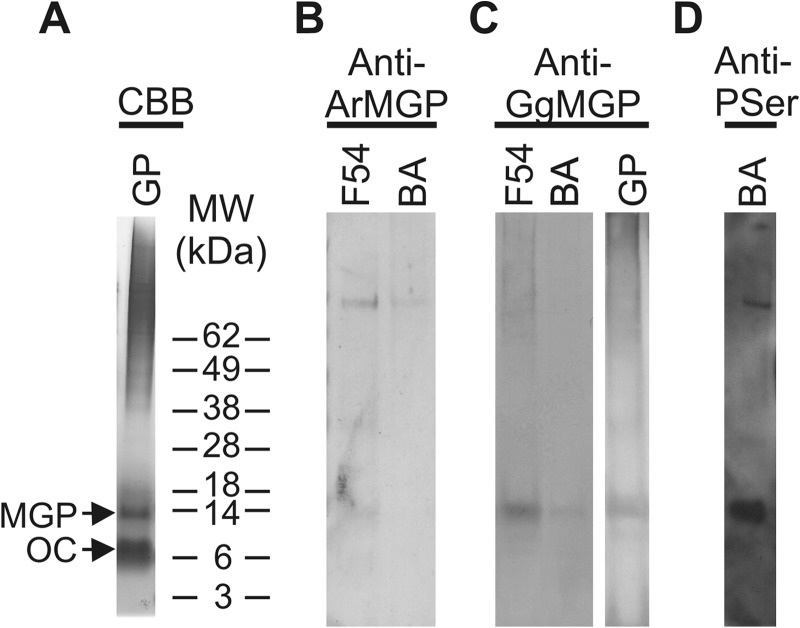

FIGURE 6.

Identification (A), detection (B and C), and characterization (D) of Adriatic sturgeon MGP from insoluble protein extracts. A, protein profile of the insoluble extract of the mineral phase of sturgeon GP revealed by CBB staining. B–D, Western blot analysis of proteins present in BA and GP insoluble extracts using anti-ArMGP (B), anti-GgMGP (C), and anti-phosphoserine (Anti-PSer) (D) antibodies. F54, RP-HPLC MGP-containing fraction 54 used as positive control. Arrows indicate the migration position of identified MGP and OC. The profile of SeeBlue prestained molecular weight marker (MW) is indicated beside the gel pictures.

Overlapping Patterns of Expression for Sturgeon OC and MGP Genes

Levels of OC and MGP gene expression were determined by qPCR in a variety of adult sturgeon tissues, including soft, cartilaginous, and bony tissues. MGP presented a typical tissue distribution, with the highest levels of gene expression found in cartilaginous tissues and a significant expression in heart, although it also showed an atypical expression in bony tissues possibly due to the presence of bone-associated cartilage tissue (Fig. 7). The OC transcript was detected in all 17 tissues analyzed, with the highest levels in bony tissues, as previously observed in mammals (10, 38, 39), an amphibian (40), and teleost fishes (19, 23, 29), but also with significant levels in cartilaginous and soft tissues (Fig. 8A). Because OC is considered a bone-specific protein, produced by osteoblasts in bone and odontoblasts in teeth (6, 9, 19, 23, 38, 29), the presence of the sturgeon transcript in soft and cartilage-containing tissues was surprising although in accordance with the high quantity of protein extracted from branchial arches. A similar tissue distribution was obtained when a second housekeeping gene (i.e. GAPDH) was used to normalize OC gene expression (results not shown). To further investigate the atypical pattern of OC gene expression in adult tissues and establish the identity of OC-expressing cells in sturgeon tissues, in situ hybridization was performed in sections from soft, cartilage, and bone sturgeon tissues (Fig. 8B). In mineralized structures, OC mRNA was strongly detected in the osteoblast-like cells in the periosteum (arrows), forming the surrounding lining cells of bone, in ganoid plates (Fig. 8B, 1), in segmented ray fins (Fig. 8B, 2), and in gill rakers (Fig. 8B, 3). Although with less intensity, OC mRNA was also detected in osteocyte-like cells of sturgeon cellular bone (i.e. ganoid plates (results not shown) and ray fins (Fig. 8B, 2, asterisk)). In cartilage-containing tissues (e.g. branchial arches and vertebra), OC mRNA was found essentially in mature chondrocytes of the cartilaginous matrix forming the branchial arches (Fig. 8B, 4) and sporadically in some immature chondrocytes adjacent to the perichondrium of vertebra, which surrounds the cartilaginous matrix (results not shown). In both branchial arches and vertebra, OC mRNA was detected in the vascular smooth muscle cells of small blood vessels and capillaries (results not shown). In heart sections, OC mRNA was strongly detected in the cardiac muscle fibers of the ventricle (Fig. 8B, 5) and in the vascular smooth muscle cells of arteries (Fig. 8B, 6). No signal was observed in negative controls performed with sense riboprobe (results not shown).

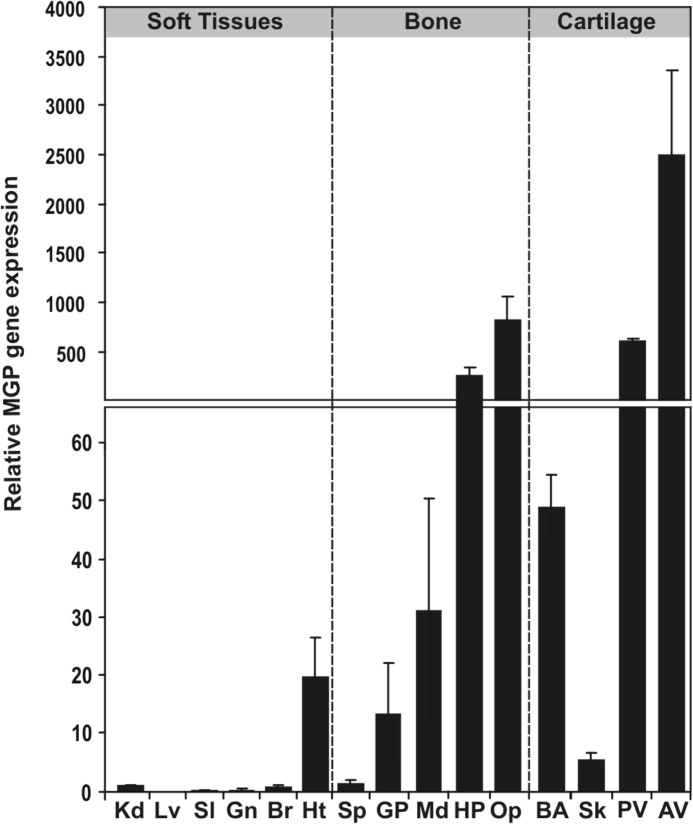

FIGURE 7.

Levels of MGP gene expression in adult Adriatic sturgeon tissues. Levels of gene expression were determined by real-time qPCR in adult soft, bone, and cartilage-containing tissues and normalized using HPRTI. The level in kidney (Kd) was used as a reference and set to 1. Lv, liver; Sl, spleen; Gn, gonads; Br, brain; Ht, heart; Sp, spine; Md, mandibula; HP, head plate; Op, operculum; Sk, skull; PV, posterior vertebra; AV, anterior vertebra. Values are the mean of three replicates and are indicated with S.D. (error bars).

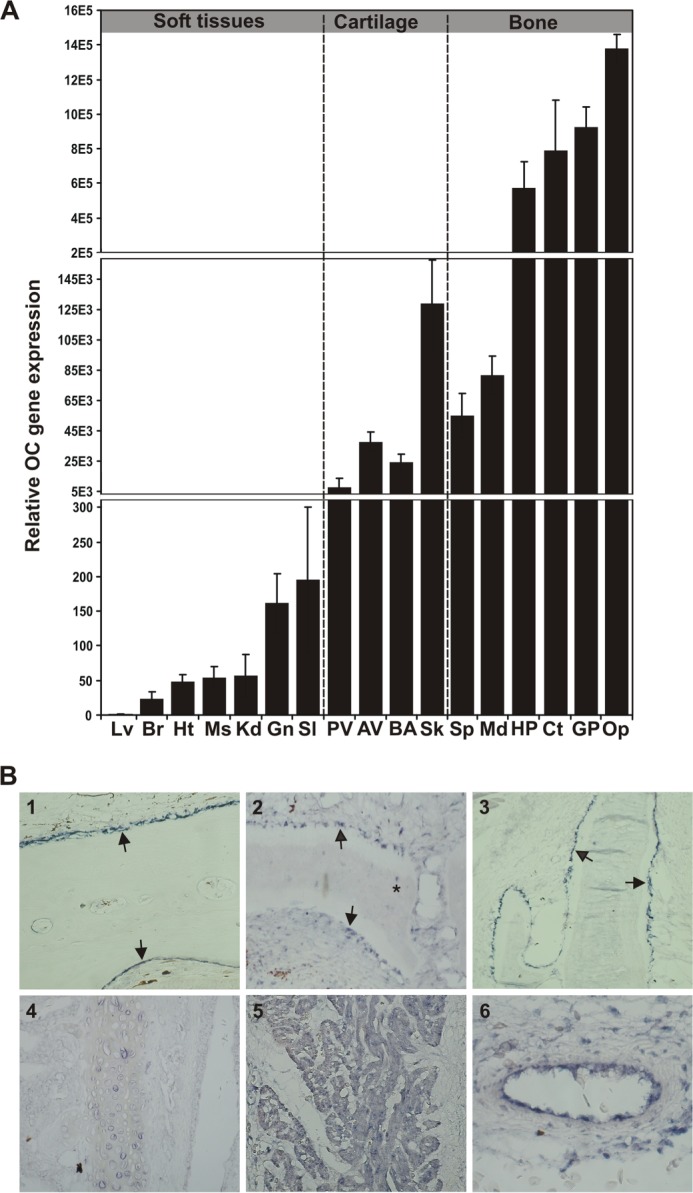

FIGURE 8.

Levels (A) and sites (B) of OC gene expression in adult Adriatic sturgeon tissues. A, levels of gene expression were determined by real-time qPCR in adult soft, bone, and cartilage-containing tissues and normalized using HPRTI. The level in liver (Lv) was used as a reference and set to 1. Br, brain; Ht, heart; Ms, muscle; Kd, kidney; Gn, gonads; Sl, spleen; PV, posterior vertebra; AV, anterior vertebra; Sk, skull; Sp, spine; Md, mandibula; HP, head plate; Ct, cleithrum; Op, operculum. Values are the mean of three replicates and are indicated with S.D. (error bars). B, sites of gene expression determined by in situ hybridization in ganoid plate (1), ray fin (2), branchial arches (3 and 4), and heart (5 and 6). The arrows indicate the periosteum surrounding the mineralized matrix in ganoid plates, ray fin, and gill rakers. *, osteocyte-like cell. Magnification is ×10 in 1–5 and ×20 in 6.

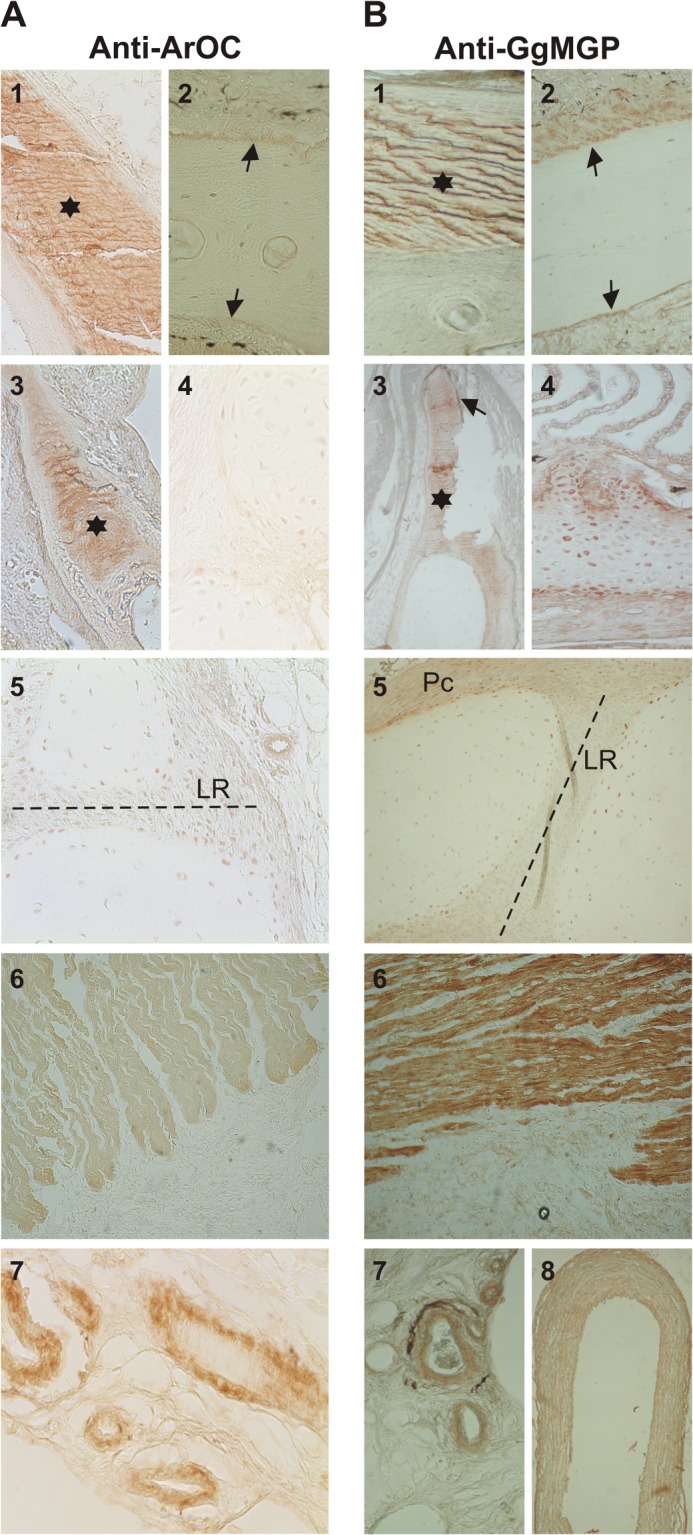

Distinct Patterns of Accumulation for Sturgeon OC and MGP Proteins

Anti-ArOC and anti-GgMGP antibodies, previously validated by Western blot, were used to determine the sites of OC and MGP protein accumulation, respectively, by immunohistochemistry in bone, in cartilage-containing tissues, and also in the heart (Fig. 9). Although OC was found highly accumulated in the mineralized extracellular bone matrix of ganoid plates (Fig. 9A, 1), it was weakly accumulated in the lining cells of the periosteum surrounding the bone mineralized matrix (Fig. 9A, 2). In contrast, MGP was preferably accumulated in the lining cells of the periosteum (Fig. 9B, 2), although positive staining was also detected in the mineralized matrix (Fig. 9B, 1). Similar results were obtained by immunofluorescence, using FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody and ArMGP as the primary antibody for MGP detection (data not shown). A similar staining pattern was obtained in the gill rakers, where the mineralized matrix preferentially accumulated OC (Fig. 9A, 3), whereas MGP was mainly detected associated with the cells forming the mineralization front surrounding the bone matrix (Fig. 9B, 3), which showed no staining for OC (Fig. 9A, 3). In the cartilage of branchial filaments, OC was barely detected (Fig. 9A, 4), whereas MGP was strongly associated with the mature and proliferative chondrocytes and with the undifferentiated chondrocytes of the perichondrium (Fig. 9B, 4). In sturgeon vertebra, OC was barely detected in the fibroblast-like cells of the cartilage ligament region and in the differentiated chondrocytes surrounding the cartilage (Fig. 9A, 5) and adjacent to the perichondrium (results not shown). In contrast, MGP was preferentially and strongly detected in the perichondrium region and in the chondrocytes surrounding the cartilage and adjacent to the perichondrium, whereas the fibroblast cells of the ligaments were barely stained (Fig. 9B, 5). Interestingly, cardiomyocytes of the ventricle cardiac fibers were positive for both OC (Fig. 9A, 6) and MGP (Fig. 9B, 6), although MGP exhibited a higher accumulation. Finally, both proteins were strongly accumulated in blood vessels of vertebra (Fig. 9, A (7) and B (7)) and branchial arches (Fig. 9B, 8). Negative controls were performed by omitting the primary antibody in the case of the affinity-purified anti-ArOC and by substituting the primary antibodies with normal rabbit serum when anti-GgMGP was used.

FIGURE 9.

Sites of OC (A) and MGP (B) protein accumulation in Adriatic sturgeon skeletal tissues. Protein immunolocalization with anti-ArOC and anti-GgMGP antibodies was performed in tissue sections prepared from non-demineralized (A (1) and B (1)) and demineralized (A (2) and B (2)) ganoid plates, branchial arches (A (3 and 4) and B (3 and 4)), vertebra (A (5) and B (5)), heart (A (6) and B (6)), and blood vessels from vertebra (A (7) and B (7)) and branchial arches (B (8)). Asterisks, mineralized bone matrix; arrows, periosteum surrounding bone matrix. LR, ligament region of cartilage in vertebra; Pc, perichondrium. Magnification is ×10 (A (5 and 6) and B (5 and 6)) and ×20 (A (1–4 and 7) and B (1–4, 7, and 8)).

DISCUSSION

We report here the identification and characterization of the mineral-binding Gla-containing proteins, OC and MGP, in the calcified cartilage and bone of Adriatic sturgeon and present biological data corroborating the previously proposed hypothesis of an evolutionary relationship between both proteins.

Sturgeon MGP behaves as other MGP proteins, exhibiting similar primary structure, post-translation modifications (phosphorylation and γ-carboxylation), and patterns of mRNA and protein distribution. Evidence was collected indicating the presence of seven Gla residues in sturgeon MGP, which, if confirmed, will be the most densely γ-carboxylated MGP in vertebrates. Similarly, sturgeon GRP was recently shown to be the most densely γ-carboxylated GRP in vertebrates, with 16 Gla residues (31). These findings suggest the presence of a highly efficient γ-carboxylation system in sturgeon, which could be related to the cartilaginous nature of its internal skeleton and the need for more efficient mechanisms to control mineralization. In this aspect, it would be interesting to determine whether the activity of sturgeon γ-glutamyl carboxylase is also above the levels usually observed in similar tissues in other organisms.

On the contrary, sturgeon OC does not behave as other OC proteins, accumulating in both the mineral phase of bone and calcified cartilage. Evidence was collected indicating the presence of motifs and residues characteristic of MGP proteins in the sturgeon OC propeptide, in particular the presence of several putative phosphorylated serines arranged in a domain similar to that observed in MGP but not to that reported in the propeptide of a fish-specific osteocalcin isoform (OC2) (41). The furin-cleaved peptide, and not the propeptide, was purified from sturgeon calcified matrix, suggesting that the mineral-binding sturgeon OC is a typical post-translationally processed OC protein lacking the putative phosphorylated domain. Although furin cleavage preferentially occurs intracellularly in the trans-Golgi network within the secretory pathway (42–44), it can also take place (i) at the cell surface (42) or (ii) within the extracellular compartment (42), as happens in the activation of the BMP antagonist nodal during mammalian antero-posterior axis formation (45). The fate of the OC propeptide is controversial. Although some studies have suggested that it remains in the cell and is not co-secreted with the mature peptide (46), others have shown that the OC propeptide is present in blood serum and could be used as a marker for osteoblastic function (47). Although both OC and GRP were shown to be processed at the polybasic RXXR furin cleavage site, showing that this enzyme is present and active in sturgeon, the possibility that the propeptide, which is likely to be phosphorylated, does exist in the extracellular matrix is conceivable and in concordance with what was observed for the human OC propeptide, shown to be co-secreted with the mature protein (47). The existence of a proteolytic processing in MGP at the highly conserved ANSF motif (7) has been suggested based on the detection of corresponding fragments in MGP preparations from mammals, sharks4 and a teleost fish (19). The propeptide of sturgeon OC would be very similar to the N-terminal fragment of MGP processed at the ANSF site, which must be present in the extracellular matrix because the complete mature MGP protein is detected bound to the mineral phase. The fate of this phosphorylated MGP fragment is unknown as well as its putative function, but we propose a similar fate for the sturgeon OC propeptide, although further studies aiming at understanding the localization and biochemical characteristics of this peptide are required. In addition, three putative phosphorylated serine residues are predicted within the mature OC protein, which would confer a new embodiment to the protein and a new dimension to its putative function. It has been demonstrated that OC and MGP, despite structural similarities, do not share the same function and that OC, despite a Gla domain, cannot act as a calcification inhibitor of extracellular matrix calcification in vivo as does MGP (26). It was also demonstrated that a phosphorylated domain is necessary to MGP antimineralization activity and that this domain, absent in OC, functions in synergy with the Gla domain to contribute to MGP function (3). It is conceivable that an osteocalcin exhibiting a phosphorylated domain, such as sturgeon OC, would function as a calcification inhibitor, overlapping with MGP function, and thus also be found at sites of MGP gene expression and protein accumulation. Indeed, sturgeon OC was not only expressed by osteoblasts, as expected for an osteocalcin, but also by chondrocytes, cardiomyocytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells, which are cells normally expressing MGP mRNA (14, 23, 48, 49). Similarly, mature protein accumulated not only in the mineralized matrix of bone but also in cartilaginous cells, heart, and blood vessels, which are typical sites of MGP accumulation (14, 24). We have previously developed vertebra- and branchial arch-derived cell cultures from sturgeon (50) and have observed that these cells do not produce a mineralized extracellular matrix when treated with a mineralogenic culture medium. Interestingly, the levels of osteocalcin significantly increase upon mineralogenic treatment in vertebra-derived cells, suggesting a response to mineralization stimuli, possibly associated with a need to control mineralization events.

Sturgeons are considered as being among the most ancient actinopterygian fishes (51) and to have undergone remarkably little morphological change, indicating that their evolution has been exceptionally slow with a significant slower rate of molecular change than observed for most fish (52). The discovery, in Adriatic sturgeon, of a typical OC protein that has retained MGP features is consistent with the current theory that both OC and MGP share a common ancestral entity, with OC originating, through gene duplication and subsequent sequence divergence, from an ancestral MGP gene (7). We propose that sturgeon hybrid protein represents an ancestral form of OC, with features close to the protein that originated from the gene duplication event that reportedly occurred 380 million years ago. For the same reasons, we also propose that sturgeon MGP may be very close to the protein ancestral to most ray-finned fish, and the presence of numerous putative γ-carboxylation sites in sturgeon MGP at positions known to be carboxylated in other fish MGPs further supports this hypothesis. The presence of more carboxylation sites in sturgeon proteins (i.e. MGP and GRP) also suggests that overall carboxylation of Gla proteins has probably decreased throughout the evolution of ray-finned fish. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first work providing clear biological evidence pointing toward the evolutionary relationship between OC and MGP proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. P. Gavaia (Center of Marine Sciences (CCMAR)) for help with the sturgeon biology and animal handling and Dr. A. Domezain (Aquaculture Rio Frio) for providing the biological material used in this study.

This work was supported in part by grant POCTI/MAR/57921/2004 from the Portuguese Science and Technology Foundation (including funds from Fundo Europeu De Desenvolvimento Regional (FEDER) (Portugal) and National Funding) and by Center of Marine Sciences (CCMAR) funding.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) EF413584, EF413587, and HM182000.

P. A. Price, unpublished results.

- OC

- osteocalcin

- MGP

- matrix Gla protein

- CBB

- Coomassie Brilliant Blue

- PTH

- phenylthiohydantoin

- RP-HPLC

- reverse phase HPLC

- Ar OC and ArMGP

- A. regius OC and MGP, respectively

- GgMGP

- G. galeus MGP

- RACE

- rapid amplification of cDNA ends, quantitative real-time PCR

- aa

- amino acid(s)

- GP

- ganoid plate(s)

- BA

- branchial arch(es)

- GRP

- Gla-rich protein

- DBS

- 4-diazobenzene sulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cranenburg E. C., Schurgers L. J., Vermeer C. (2007) Vitamin K. The coagulation vitamin that became omnipotent. Thromb. Haemost. 98, 120–125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Price P. A., Urist M. R., Otawara Y. (1983) Matrix Gla protein, a new γ-carboxyglutamic acid-containing protein which is associated with the organic matrix of bone. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 117, 765–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schurgers L. J., Spronk H. M., Skepper J. N., Hackeng T. M., Shanahan C. M., Vermeer C., Weissberg P. L., Proudfoot D. (2007) Post-translational modifications regulate matrix Gla protein function. Importance for inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. J. Thromb. Haemost. 5, 2503–2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shearer M. J., Newman P. (2008) Metabolism and cell biology of vitamin K. Thromb. Haemost. 100, 530–547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Price P. A., Poser J. W., Raman N. (1976) Primary structure of the γ-carboxyglutamic acid-containing protein from bovine bone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 73, 3374–3375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cancela M. L., Williamson M. K., Price P. A. (1995) Amino-acid sequence of bone Gla protein from the African clawed toad Xenopus laevis and the fish Sparus aurata. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 46, 419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laizé V., Martel P., Viegas C. S., Price P. A., Cancela M. L. (2005) Evolution of matrix and bone γ-carboxyglutamic acid proteins in vertebrates. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26659–26668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boskey A. L., Gadaleta S., Gundberg C., Doty S. B., Ducy P., Karsenty G. (1998) Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopic analysis of bones of osteocalcin-deficient mice provides insight into the function of osteocalcin. Bone 23, 187–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hauschka P. V., Wians F. H., Jr. (1989) Osteocalcin-hydroxyapatite interaction in the extracellular organic matrix of bone. Anat. Rec. 224, 180–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Price P. A. (1985) Vitamin K-dependent formation of bone Gla protein (osteocalcin) and its function. Vitam. Horm. 42, 65–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hinoi E., Gao N., Jung D. Y., Yadav V., Yoshizawa T., Kajimura D., Myers M. G., Jr., Chua S. C., Jr., Wang Q., Kim J. K., Kaestner K. H., Karsenty G. (2009) An osteoblast-dependent mechanism contributes to the leptin regulation of insulin secretion. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1173, E20–E30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karsenty G., Ferron M. (2012) The contribution of bone to whole-organism physiology. Nature 481, 314–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oury F., Ferron M., Huizhen W., Confavreux C., Xu L., Lacombe J., Srinivas P., Chamouni A., Lugani F., Lejeune H., Kumar T. R., Plotton I., Karsenty G. (2013) Osteocalcin regulates murine and human fertility through a pancreas-bone-testis axis. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 2421–2433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hale J. E., Fraser J. D., Price P. A. (1988) The identification of matrix Gla protein in cartilage. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 5820–5824 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Otawara Y., Price P. A. (1986) Developmental appearance of matrix GLA protein during calcification in the rat. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 10828–10832 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Price P. A., Rice J. S., Williamson M. K. (1994) Conserved phosphorylation of serines in the Ser-X-Glu/Ser(P) sequences of the vitamin K-dependent matrix Gla protein from shark, lamb, rat, cow, and human. Protein Sci. 3, 822–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cancela M. L., Ohresser M. C., Reia J. P., Viegas C. S., Williamson M. K., Price P. A. (2001) Matrix Gla protein in Xenopus laevis. Molecular cloning, tissue distribution, and evolutionary considerations. J. Bone Miner. Res. 16, 1611–1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rice J. S., Williamson M. K., Price P. A. (1994) Isolation and sequence of the vitamin K-dependent matrix Gla protein from the calcified cartilage of the soupfin shark. J. Bone Miner. Res. 9, 567–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simes D. C., Williamson M. K., Ortiz-Delgado J. B., Viegas C. S., Cancela M. L., Price P. A. (2003) Purification of matrix Gla protein from a marine teleost fish, Argyrosomus regius. Calcified cartilage and not bone as the primary site of MGP accumulation in fish. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 244–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Proudfoot D., Skepper J. N., Shanahan C. M., Weissberg P. L. (1998) Calcification of human vascular cells in vitro is correlated with high levels of matrix Gla protein and low levels of osteopontin expression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 18, 379–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yagami K., Suh J. Y., Enomoto-Iwamoto M., Koyama E., Abrams W. R., Shapiro I. M., Pacifici M., Iwamoto M. (1999) Matrix GLA protein is a developmental regulator of chondrocyte mineralization and, when constitutively expressed, blocks endochondral and intramembranous ossification in the limb. J. Cell Biol. 147, 1097–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hashimoto F., Kobayashi Y., Kobayashi E. T., Sakai E., Kobayashi K., Shibata M., Kato Y., Sakai H. (2001) Expression and localization of MGP in rat tooth cementum. Arch. Oral Biol. 46, 585–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ortiz-Delgado J. B., Simes D. C., Gavaia P., Sarasquete C., Cancela M. L. (2005) Osteocalcin and matrix GLA protein in developing teleost teeth. Identification of sites of mRNA and protein accumulation at single cell resolution. Histochem. Cell Biol. 124, 123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schurgers L. J., Cranenburg E. C., Vermeer C. (2008) Matrix Gla-protein. The calcification inhibitor in need of vitamin K. Thromb. Haemost. 100, 593–603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luo G., Ducy P., McKee M. D., Pinero G. J., Loyer E., Behringer R. R., Karsenty G. (1997) Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature 386, 78–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murshed M., Schinke T., McKee M. D., Karsenty G. (2004) Extracellular matrix mineralization is regulated locally. Different roles of two Gla-containing proteins. J. Cell Biol. 165, 625–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hur D. J., Raymond G. V., Kahler S. G., Riegert-Johnson D. L., Cohen B. A., Boyadjiev S. A. (2005) A novel MGP mutation in a consanguineous family. Review of the clinical and molecular characteristics of Keutel syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 135, 36–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Simes D. C., Williamson M. K., Schaff B. J., Gavaia P. J., Ingleton P. M., Price P. A., Cancela M. L. (2004) Characterization of osteocalcin (BGP) and matrix Gla protein (MGP) fish specific antibodies. Validation for immunodetection studies in lower vertebrates. Calcif. Tissue Int. 74, 170–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pinto J. P., Ohresser M. C., Cancela M. L. (2001) Cloning of the bone Gla protein gene from the teleost fish Sparus aurata. Evidence for overall conservation in gene organization and bone-specific expression from fish to man. Gene 270, 77–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hall B. K. (2005) Bones and Cartilage: Developmental and Evolutionary Skeletal Biology, Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 31. Viegas C. S., Simes D. C., Laizé V., Williamson M. K., Price P. A., Cancela M. L. (2008) Gla-rich protein (GRP), a new vitamin K-dependent protein identified from sturgeon cartilage and highly conserved in vertebrates. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 36655–36664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Viegas C. S., Cavaco S., Neves P. L., Ferreira A., João A., Williamson M. K., Price P. A., Cancela M. L., Simes D. C. (2009) Gla-rich protein is a novel vitamin K-dependent protein present in serum that accumulates at sites of pathological calcifications. Am. J. Pathol. 175, 2288–2298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wallace I. M., O'Sullivan O., Higgins D. G., Notredame C. (2006) M-Coffee. Combining multiple sequence alignment methods with T-Coffee. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 1692–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bendtsen J. D., Nielsen H., von Heijne G., Brunak S. (2004) Improved prediction of signal peptides. SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340, 783–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blom N., Gammeltoft S., Brunak S. (1999) Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J. Mol. Biol. 294, 1351–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Conceição N., Silva A. C., Fidalgo J., Belo J. A., Cancela M. L. (2005) Identification of alternative promoter usage for the matrix Gla protein gene. Evidence for differential expression during early development in Xenopus laevis. FEBS J. 272, 1501–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Conceição N., Laizé V., Simões B., Pombinho A. R., Cancela M. L. (2008) Retinoic acid is a negative regulator of matrix Gla protein gene expression in teleost fish Sparus aurata. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1779, 28–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hauschka P. V., Lian J. B., Cole D. E., Gundberg C. M. (1989) Osteocalcin and matrix Gla protein. Vitamin K-dependent proteins in bone. Physiol. Rev. 69, 990–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lian J. B., Hauschka P. V., Gallop P. M. (1978) Properties and synthesis of a vitamin K-dependent calcium-binding protein in bone. Fed. Proc. 37, 2615–2620 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Viegas C. S., Pinto J. P., Conceição N., Simes D. C., Cancela M. L. (2002) Cloning and characterization of the cDNA and gene encoding Xenopus laevis osteocalcin. Gene 289, 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Laizé V., Viegas C. S., Price P. A., Cancela M. L. (2006) Identification of an osteocalcin isoform in fish with a large acidic prodomain. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15037–15043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Seidah N. G., Prat A. (2002) Precursor convertases in the secretory pathway, cytosol and extracellular milieu. Essays Biochem. 38, 79–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thomas G. (2002) Furin at the cutting edge. From protein traffic to embryogenesis and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 753–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thomas J. T., Prakash D., Weih K., Moos M., Jr. (2006) CDMP1/GDF5 has specific processing requirements that restrict its action to joint surfaces. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26725–26733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Beck S., Le Good J. A., Guzman M., Ben Haim N., Roy K., Beermann F., Constam D. B. (2002) Extraembryonic proteases regulate Nodal signalling during gastrulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 981–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gundberg C. M., Clough M. E. (1992) The osteocalcin propeptide is not secreted in vivo or in vitro. J. Bone Miner. Res. 7, 73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hosoda K., Kanzaki S., Eguchi H., Kiyoki M., Yamaji T., Koshihara Y., Shiraki M., Seino Y. (1993) Secretion of osteocalcin and its propeptide from human osteoblastic cells. Dissociation of the secretory patterns of osteocalcin and its propeptide. J. Bone Miner. Res. 8, 553–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fraser J. D., Price P. A. (1988) Lung, heart, and kidney express high levels of mRNA for the vitamin K-dependent matrix Gla protein. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 11033–11036 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shanahan C. M., Weissberg P. L., Metcalfe J. C. (1993) Isolation of gene markers of differentiated and proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 73, 193–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Viegas C. S. B., Conceição N., Fazenda C., Simes D. C., Cancela M. L. (2010) Expression of Gla-rich protein (GRP) in newly developed cartilage-derived cell cultures from sturgeon (Acipenser naccarii). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 26, 214–218 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deleted in proof [Google Scholar]

- 52. Krieger J., Fuerst P. A. (2002) Evidence for a slowed rate of molecular evolution in the order Acipenseriformes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 891–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]