Background: Avibactam is a β-lactamase inhibitor with a broad spectrum of activity.

Results: Kinetic parameters of inhibition as well as acyl enzyme stability are reported against six clinically relevant enzymes.

Conclusion: Inhibition efficiency is highest against class A, then class C, and then class D.

Significance: These base-line inhibition values across enzyme classes provide the foundation for future structural and mechanistic enzymology experiments.

Keywords: Antibiotics, Drug Discovery, Enzyme Inhibitors, Enzyme Kinetics, Mass Spectrometry (MS)

Abstract

Avibactam is a non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor with a spectrum of activity that includes β-lactamase enzymes of classes A, C, and selected D examples. In this work acylation and deacylation rates were measured against the clinically important enzymes CTX-M-15, KPC-2, Enterobacter cloacae AmpC, Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpC, OXA-10, and OXA-48. The efficiency of acylation (k2/Ki) varied across the enzyme spectrum, from 1.1 × 101 m−1s−1 for OXA-10 to 1.0 × 105 for CTX-M-15. Inhibition of OXA-10 was shown to follow the covalent reversible mechanism, and the acylated OXA-10 displayed the longest residence time for deacylation, with a half-life of greater than 5 days. Across multiple enzymes, acyl enzyme stability was assessed by mass spectrometry. These inhibited enzyme forms were stable to rearrangement or hydrolysis, with the exception of KPC-2. KPC-2 displayed a slow hydrolytic route that involved fragmentation of the acyl-avibactam complex. The identity of released degradation products was investigated, and a possible mechanism for the slow deacylation from KPC-2 is proposed.

Introduction

The β-lactam class of antibacterial agents is a mainstay of the treatment of infections caused by Gram-negative bacterial pathogens (1). However, the clinical utility of β-lactams is diminished by β-lactamase enzymes that hydrolyze them. As successive generations of β-lactams have been introduced into clinical use, new β-lactamase enzymes have emerged that have blunted their efficacy (2–4).

β-Lactamase enzymes can be classified according to several schemes. In the Ambler nomenclature (5), class A, C, and D enzymes employ a serine residue as the nucleophilic species to attack the lactam carbonyl, forming an acyl enzyme intermediate before hydrolysis. The class B group are metalloenzymes that employ zinc ions to coordinate the β-lactam substrate for direct hydrolytic attack by water. Among the serine enzymes, classes A, C, and D are further distinguished by architectural and mechanistic differences in amino acid residues employed for acylation and deacylation (6).

Pairing a β-lactam with a β-lactamase inhibitor (BLI)2 is an effective strategy to combat β-lactam resistance; however, the span of coverage of the inhibitor determines the breadth of antibacterial activity of the β-lactam/BLI drug combination. Currently, only three BLIs are in clinical use: clavulanic acid, tazobactam, and sulbactam. The spectrum of coverage of these inhibitors is limited largely to class A enzymes, and as a result their β-lactam combinations are liable to resistance from expression of class C and class D enzymes (7–9).

Avibactam is the first example of a class of BLI that possesses a broader spectrum of activity than currently employed BLIs (8, 10). Avibactam is in phase III clinical development in combination with the third-generation cephalosporin ceftazidime (11). The addition of avibactam to ceftazidime has been shown to restore antibacterial activity against strains that express a wide range of β-lactamase enzymes of classes A, C, and some class D (12–14). Whereas a large number of bacterial strains have been profiled for antibacterial activity, the number and diversity of β-lactamase enzymes for which avibactam inhibition has been characterized is small (15–19).

In this work the inhibitory properties of avibactam were measured across a wide variety of enzymes selected for their clinical relevance. Of the class A enzymes two enzymes were profiled: the widely disseminated extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-15 (20) and KPC-2 (21), a carbapenemase capable of hydrolyzing penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems. Within class C the enzymes were chosen to represent Enterobacteriaceae with the AmpC from Enterobacter cloacae and the non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli with the AmpC from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The class D enzymes were represented by OXA-10, one of the most prevalent OXA enzymes in P. aeruginosa (22), and OXA-48, a carbapenemase OXA that has achieved notoriety due to its contribution to multi-drug resistance in a family of pathogens labeled CRE (carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae) (23).

Biochemical and biophysical studies have provided the basis for mechanistic understanding of β-lactam/BLI interactions from a wide variety of inhibitors and enzymes. High resolution x-ray structures exist for each of the enzymes employed in this work, including avibactam bound to CTX-M-15 and P. aeruginosa AmpC (24). This study provides a base-line view of avibactam inhibition across β-lactamase classes upon which to build deeper structure-function relationships.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA Manipulations and Plasmid Construction

Plasmid DNA purification, PCR product purification, and gel extraction were performed using the PureYield Plasmid Midiprep System (Promega, Madison, WI), QuickStepTM 2 PCR Purification kit (EdgeBio, Gaithersburg, MD), and Rapid Gel Extraction Kit (Marligen Biosciences, Ijamsville, MD), respectively. Restriction enzymes and rAPid alkaline phosphatase were purchased from (Roche Applied Science). Primers for PCR DNA amplification and for site-directed mutagenesis were purchased from Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL). All PCRs were performed with High Fidelity PCR Master (Roche Applied Science) or Platinum PCR Supermix High Fidelity (Invitrogen) using reaction conditions specified by the manufacturer. All ligation reactions were performed using the Rapid DNA ligation Kit (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

The plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. The PCR primers are listed in Table 2. To construct pJT763, the blaKPC-2 gene was amplified from pBBR1MCS2-KPC-2 with KPC-2-F-NdeI and KPC-2-R-SalI primers, then cloned into pET-29 and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α-T1R chemically competent cells (Invitrogen). The plasmid pJT1196, a plasmid for expression of E. cloacae P99 AmpC, was constructed by amplifying the gene from pBBR1MCS2-P99 using P99-F-NdeI and P99-R-SalI primers, then cloning into pET-30a and transforming into E. coli DH5α-T1R cells. The OXA-10 expression plasmid, pJT738, was constructed by replacing the native signal sequence with pelB during PCR. The gene blaOXA-10 was amplified from pLBII-OXA-10 using OXA-10-pelB-F-NdeI and OXA-10-R-SalI primers, cloned into pET-29a, and transformed into E. coli DH5α-T1R cells. The plasmid pJT762, an OXA-48 expression plasmid, was constructed in a similar fashion as OXA-10 described above. Here, the primers OXA-48-pelB-F-NdeI and OXA-48-R-SalI were used to amplify blaOXA-48 with a pelB signal sequence using pET-9-OXA-48 as a template. All transformants were verified by PCR, restriction endonuclease digestion, and sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this work

| Plasmid | Use | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pET-29a-CTX-M-15 | CTX-M-15 expression | Novexel (16) |

| pBBR1MCS2-KPC-2 | Broad-host range plasmid (36) with KPC-2 | Novexel |

| pBBR1MCS2-P99 | Broad-host range plasmid with P99 | Novexel |

| pET-9a-AmpC | P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC expression | Provided by J. D. Docquier |

| pLBII-OXA-10 | pBC-SK derivative with OXA-10 | Provided by J. D. Docquier (39) |

| pET-9a-OXA-48 | OXA-48 expression | Provided by J. D. Docquier |

| pJT763 | KPC-2 expression | This study |

| pJT1196 | E. cloacae P99 AmpC expression | This study |

| pJT738 | pelB-OXA-10 expression | This study |

| pJT762 | pelB-OXA-48 expression | This study |

| pET-30a | T7-based expression | EMD-Millipore |

| pET-29a | T7-based expression | EMD-Millipore |

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this work (restriction sites are italicized and underlined)

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| KPC-2-F-NdeI | GGATCGCATATGTCACTGTATCGCCGTCT |

| KPC-2-R-SalI | GGTATTGTCGACTTACTGCCCGTTGACGCCCAATCC |

| P99-F-NdeI | GGATCGCATATGATGAGAAAATCCCTT |

| P99-R-SalI | GTGATTGTCGACTTACTGTAGCGCCTCGAGGATATGGTA |

| OXA-10-pelB-F-NdeI | GATATTCATATGAAATACCTGCTGCCGACCGCTGCTGCTGGTCTGCTGCTCCTCGCTGCCCAGCCGGCGATGGCCTCAATTACAGAAAATACGTCT |

| OXA-10-R-SalI | GGACTGGTCGACTTAGCCACCAATGATGCCCT |

| OXA-48-pelB-F-NdeI | GAACATCATATGAAATACCTGCTGCCGACCGCTGCTGCTGGTCTGCTGCTCCTCGCTGCCCAGCCGGCGATGGCCATGAAGGAATGGCAAGAAAACAAAGTTGG |

| OXA-48-R-SalI | GGGCCGGGTCGACTTAGGGAATAATTTTTTCCTGTTTGAGCA |

Protein Purification

TEM-1 was cloned and purified as described previously (18).

CTX-M-15

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells transformed with plasmid pET-29a-CTX-M-15 were inoculated into LB medium with 50 μg/ml kanamycin at A600 0.3, incubated at RT for 3 h, induced with 0.01 mm IPTG at A600 0.8, incubated for 24 h at RT, harvested at A600 2.1 by centrifugation, and frozen at −80 °C. Cell paste from 4 liters of culture expressing CTX-M-15 was resuspended in 75 ml of buffer containing 20 mm MES (pH 5.0) and passed through a French press at 4 °C twice at 18,000 p.s.i. The extract was centrifuged in a Beckman JA-12 rotor at 11,000 rpm (8260 × g) for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was applied to a 20-ml GE Healthcare Life Sciences SP column equilibrated with the same buffer at a flow rate of 3 ml/min. The column was washed with the same buffer until the 280-nm absorbance returned to base line, then eluted with a 10-column-volume linear gradient of 0–0.5 m NaCl in the same buffer. Fractions containing CTX-M-15, based on SDS-PAGE, were pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal ultra filtration units. The concentrated protein was applied to a 300-ml HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.3), 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol at 2 ml/min. Fractions containing CTX-M-15 were pooled, concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal ultrafiltration units to final concentration of 8.9 mg/ml.

KPC-2

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells transformed with plasmid pJT763 were inoculated into LB medium with 50 μg/ml kanamycin at A600 0.1, incubated at RT for 4.3 h, induced with 0.01 mm IPTG at A600 0.45, incubated for 18 h at RT, harvested at A600 3.2 by centrifugation, and frozen at −80 °C. Cell paste from 2 liters of culture expressing KPC-2 was resuspended in 75 ml of buffer containing 20 mm MES (pH 5.5) and then purified as above with the omission of glycerol from the Superdex column. Fractions containing KPC-2 were pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal ultrafiltration units to a final concentration of 6 mg/ml.

E. cloacae P99 AmpC

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells transformed with plasmid pJT1196 were inoculated into LB medium with 50 mg/ml kanamycin at A600 0.1, incubated at 30 °C for 3 h, induced with 0.02 mm IPTG at A600 0.66, incubated for 22 h at 18 °C, harvested at A600 4.2 by centrifugation, and frozen at −80 °C. Cell paste from 2 liters of culture expressing E. cloacae P99 AmpC was resuspended in 35 ml of buffer containing 20 mm MES (pH 5.0), and purified as above for KPC-2. Fractions containing E. cloacae P99 AmpC were pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal ultrafiltration units to a final concentration of 4.0 mg/ml.

P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells transformed with plasmid pET-9a-AmpC were inoculated into LB medium plus 0.5% glucose with 50 μg/ml kanamycin at A600 0.1, incubated at RT for 6 h, induced with 0.01 mm IPTG at A600 0.5, incubated for 18 h at RT, harvested at A600 4.2 by centrifugation, and frozen at −80 °C. Cell paste from 2 liters of culture expressing P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC was resuspended in 35 ml of buffer containing 20 mm MES (pH 5.0), and purified as above for CTX-M-15. Fractions containing P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC were pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal ultrafiltration units to final concentration of 10 mg/ml.

OXA-10

E. coli BL21(DE3)STAR cells transformed with plasmid pJT738 were inoculated into LB medium with 50 mg/ml kanamycin at A600 0.1, incubated at RT for 5 h, induced with 0.01 mm IPTG at A600 0.6, incubated for 20 h at RT, harvested at A600 2.96 by centrifugation, and frozen at −80 °C. Cell paste from 2 liters of culture expressing OXA-10 was resuspended in 75 ml of buffer containing 20 mm MES (pH 6.0) and purified as above for CTX-M-15. Fractions containing OXA-10 were pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal ultrafiltration units to final concentration of 5.2 mg/ml.

OXA-48

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells transformed with plasmid pJT762 were inoculated into LB medium with 50 mg/ml kanamycin at A600 0.1, incubated at RT for 4 h, induced with 0.01 mm IPTG at A600 0.62, incubated for 18 h at RT, harvested at A600 3.2 by centrifugation, and frozen at −80 °C. Cell paste from 2 liters of culture expressing OXA-48 was resuspended in 75 ml of buffer containing 20 mm triethanolamine (pH 5.5) and purified as above for CTX-M-15. Fractions containing OXA-48 were pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal ultrafiltration units to a final concentration of 7.6 mg/ml.

All purified proteins were verified to be >95% pure as assessed by SDS-PAGE gels. β-Lactamase identities were confirmed by comparing measured masses by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry to the signal sequence-cleaved protein sequences found in the β-lactamase database (Lahey Clinic (http://www.lahey.org/Studies/)) for class A and D enzymes. E. cloacae P99 AmpC and P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC were matched to UniProt sequences P05364 and P24735, respectively.

Enzyme Assays

Nitrocefin was purchased from Acme Bioscience, Inc. Acylation experiments were carried out at 37 °C in 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) as described previously (18) using a Cary 400 Bio UV-visual spectrophotometer (Varian, Inc.) outfitted with a temperature controller. The assays for OXA enzymes were performed under identical conditions but with the addition of 50 mm NaHCO3. Enzyme concentrations were adjusted so as to yield the following final concentrations in a 1-ml stirred cuvette: 0.08 nm CTX-M-15, 0.08 nm KPC-2, 0.028 nm E. cloacae P99 AmpC, 0.04 nm P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC, 0.06 nm OXA-10, and 0.02 nm OXA-48. The maximum concentration of avibactam in the on-rate assays was 5 μm with CTX-M-15, 25 μm with KPC-2, 50 μm with E. cloacae P99 AmpC, 37.5 μm with P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC, 10 mm with OXA-10, and 100 μm with OXA-48.

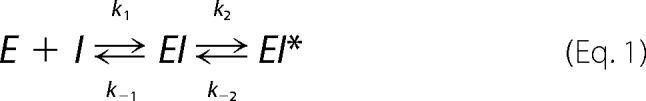

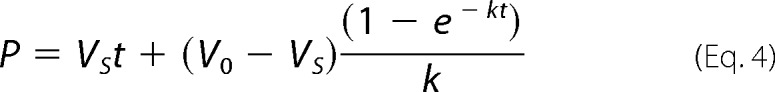

Data were fit to a two-step, reversible inhibition model,

|

where

|

and

|

Time courses were fit to Equation 4 to obtain the pseudo first-order rate constant for enzyme inactivation, kobs (25).

|

Equation 5 was used to derive k2/Ki, the second-order rate constant for enzyme acylation.

|

The reported values includes an adjustment for the (1 + S/Km) term to account for the nitrocefin substrate concentration, 200 μm relative to the nitrocefin Km values of 40 μm for CTX-M-15, 40 μm for KPC-2, 100 μm for E. cloacae P99 AmpC, 200 μm for P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC, 20 μm for OXA-10, 100 μm for OXA-48. Error values reported are the standard errors of the fit.

Deacylation (off-rate) experiments were carried out at 37 °C using a jump dilution method followed with a continuous assay to monitor activity regain, as described previously (18). Enzymes were inactivated by avibactam using the following concentrations: 1 μm CTX-M-15 with 5 μm avibactam, 2 μm KPC-2 with 10 μm avibactam, 0.5 μm E. cloacae P99 AmpC with 5 μm avibactam, 1 μm P. aeruginosa AmpC with 100 μm avibactam, 48 μm OXA-10 with 1 mm avibactam, and 7 μm OXA-48 with 10 μm avibactam. A 4400-fold dilution was performed on inactivation mixtures containing CTX-M-15, KPC-2, and P99 AmpC. The inactivation mixture with P. aeruginosa AmpC was diluted 8900-fold. OXA-10 and OXA-48 inactivation mixtures were diluted 200,000- and 160,000-fold, respectively. For the class A and C enzymes, enzyme activity was assayed by a continuous absorbance A490 read after adding 20 μl of diluted inactivation mixtures to 180 μl of 200 μm nitrocefin in the presence or absence of avibactam. For OXA-10 and OXA-48, discontinuous sampling from the diluted mixture was employed over the course of 5 days for OXA-10 and 3 days for OXA-48. The samples were measured for % inhibition, and the off-rate was calculated using an equation for single exponential decay (26). Error values reported are 2 S.D. from the mean.

Acyl enzyme Stability

1 μm enzyme was incubated with 5 μm avibactam in phosphate buffer at 37 °C for 5 min or 3 h until the enzyme was fully acylated. The excess compound was then removed by ultrafiltration using a 5-kDa MWCO centrifugation unit (Ultrafree-0.5, Millipore, Bedford MA). A 200-μl aliquot of the reaction was placed in the unit and centrifuged at 7800 × g for 8 min at 4 °C. Two subsequent wash steps were performed, each consisting of the addition of an aliquot of buffer (180 μl) to the retentate and centrifugation (7800 × g) for 8 min at 4 °C. The final retentate was collected and brought to 200 μl. To monitor the stability of the acylated enzyme, the resultant 1 μm acyl enzyme product was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C followed by analysis by direct infusion ESI-MS (QStar Pulsar i, AB-Sciex, Concord, Ontario, Canada) equipped with a Turbo Ion Spray source. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion mode and was tuned to a declustering potential of 30 V to minimize the appearance of in-source loss of 80 Da from avibactam-enzyme covalent complexes. Samples were desalted using a Michrom Macrotrap cartridge using a buffer consisting of 5% methanol, 0.1% formic acid, and then eluted directly from the cartridge into the mass spectrometer with 90% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid.

OXA-10 Acylation and Deacylation Time Course

For the acylation time course of OXA-10, 1 μm OXA-10 was incubated with 5 μm avibactam in 100 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 50 mm sodium bicarbonate at 37 °C (27) for several hours. The reaction was sampled at different time points during this period, then either snap-frozen on dry ice if analyzed later or immediately analyzed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI)-MS. After 100% acylation was achieved, the excess avibactam in the acyl enzyme reaction was removed by ultrafiltration essentially as described above with the addition of a third wash step. The 1 μm OXA-10 acyl enzyme was then incubated for up to several days at 37 °C. Aliquots were taken at different time points during this period of time and analyzed by ESI-MS.

OXA-10 Acyl Exchange with TEM-1

To monitor acyl exchange of avibactam from OXA-10, a 5 μm sample of OXA-10 acyl enzyme was prepared by incubation in the presence of 25 μm avibactam. After a 20-min reaction at 37 °C, excess avibactam was removed by ultrafiltration as described above. An aliquot of the OXA-10 acyl enzyme was combined with TEM-1 and sodium bicarbonate to reach final enzyme concentrations of 5 μm and bicarbonate concentration of 10 mm. The intact protein composition of the mixture was monitored by direct infusion ESI-MS.

KPC-2 Hydrolysis of Avibactam

To closely monitor the time course of protein species produced from degradation of the KPC-2 acyl enzyme, a timed, 37 °C LC-MS experiment was performed. A 1 μm sample of KPC-2 acyl enzyme was prepared with the aid of ultrafiltration as described above and placed in a 37 °C autosampler tray. This complex was analyzed by HPLC-ESI-MS using an AB-Sciex 5600 mass spectrometer interfaced to a Shimadzu LC-20AD chromatography system. Samples were injected onto an Agilent Poroshell 300SB-C8 75 × 2.1-mm, 5-μm column. The HPLC method used a reverse-phase buffer system consisting of 0.1% formic acid in water (Buffer A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (Buffer B). The HPLC method used a 2.5-min gradient from 5 to 95% Buffer B with a 1-min hold at 95% before returning to 5% Buffer B for equilibration. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion, intact protein mode with a source temperature of 500 °C, declustering potential of 20 V, and a spray voltage of 400 V using a Turbo Ion Spray source. The avibactam-KPC-2 sample was held at 37 °C in an autosampler vial for the duration of the experiment. Aliquots of 2 μl were injected at measured times using recorded autosampler injection time over a 32-h period after the 1 μm sample was thawed from dry ice. Peak areas for several protein species were determined after spectrum deconvolution using Analyst TF (Version 1.6) software.

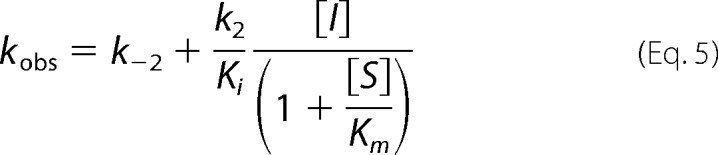

Synthesis of Isotopically Labeled Avibactam

Isotopically labeled versions of avibactam were prepared by Onyx Scientific Ltd. One version contained the 13C label in the C7 urea position, and the other contained 13C atoms in the piperidine and amide positions and 15N at N1 (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Structures of avibactam (1), avibactam 13C-labeled in the urea (2), and avibactam 13C-labeled at five carbon positions and 15N labeled at the N1 position (3).

NMR Methods

13C NMR spectra of isotopically labeled avibactam compounds were acquired at 37 °C on a 600-MHz NMR instrument with a Bruker AVANCE III console and a triple resonance cryogenic probe. For a typical proton-decoupled 13C NMR experiment, signal acquisition employed a 30° pulse angle, and the data were collected with a sweep width of 36,057 Hz, 32,000 data points, and 2 s for the relaxation delay. 4096 scans were recorded for each experiment, which resulted in ∼3 h per spectrum. The data were multiplied by an exponential function (line broadening 3 Hz) before Fourier transformation. The NMR samples were prepared by adding 400 μm isotopically labeled avibactam to 400 μm KPC-2 in 100 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) supplemented with 5% D2O.

High Resolution Mass Spectrometry

400 μm KPC-2 was added to 300 μm avibactam in 100 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 h. The protein was removed by ultrafiltration before LC-MS analysis. Mass analysis was performed on an LTQ Orbitrap Hybrid FT mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to Accela LC (Thermo) and CTC autosampler (Thermo). A Hypersil GOLD AQ 3-mm column (Thermo), 50-mm length, 3-μm particle size was used for the separation. The mobile phase was 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and in acetonitrile (B), and the flow rate was 400 μl/min. MS scans were performed in the positive ion mode, m/z range 50–400 at a resolution of 30,000. Internal calibration was used for the accurate mass measurement.

RESULTS

Acylation Kinetics against Class A, C, and D β-Lactamases

Using a spectrophotometric assay and the reporter substrate nitrocefin, the kinetic constants for avibactam acylation and deacylation were measured for the enzymes CTX-M-15, KPC-2, E. cloacae P99 AmpC, P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC, OXA-10, and OXA-48 (Table 3). As was the case for TEM-1 (18), for these additional enzymes the plots of kobs versus avibactam concentration remained linear for avibactam concentrations up to the highest concentration tested. Because saturation could not be demonstrated, the second-order rate constants for acylation are reported.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic values for the acylation and deacylation parameters of avibactam against classes A, C, and D enzymes

Acylation on rates and deacylation off rates were measured using reporter assays detecting nitrocefin turnover. Kd values are calculated from the off and on rates.

| Parameter | TEM-1a | CTX-M-15 | KPC-2 | E. cloacae P99 AmpC | P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC | OXA-10 | OXA-48 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acylation k2/Ki (M−1s−1) | 1.6 ± 0.1 × 105 | 1.3 ± 0.1 × 105 | 1.3 ± 0.1 × 104 | 5.1 ± 0.1 × 103 | 2.9 ± 0.1 × 103 | 1.1 ± 0.1 × 101 | 1.4 ± 0.1 × 103 |

| Deacylation koff (s−1) | 8 ± 4 × 10−4 | 3 ± 1 × 10−4 | 1.4 ± 0.1 × 10−4 | 3.8 ± 0.2 × 10−5 | 1.9 ± 0.6 × 10−3 | <1.6 × 10−6 | 1.2 ± 0.4 × 10−5 |

| Deacylation t½ (min) | 16 ± 8 | 40 ± 10 | 82 ± 6 | 300 ± 20 | 6 ± 2 | >7200 | 1000 ± 300 |

| Kd (μm) | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.66 | <0.15 | 0.009 |

a Data were from Ref. 18.

Within the class A enzymes, the extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-15 was acylated with high efficiency, on the order of 105 m−1s−1, which was similar to the efficiency measured for TEM-1. However, the inhibition efficiency against the carbapenemase KPC-2 was ∼10-fold weaker than CTX-M-15 and TEM-1. Within the class C exemplars, acylating activity was similar between E. cloacae P99 AmpC and P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC; for both enzymes the acylation efficiency exceeded 103 m−1s−1. Inhibition of the class D enzymes exhibited the most intra-class diversity. The acylation rate of avibactam against OXA-48 was similar to the class C enzymes, whereas the OXA-10 inhibition rate of 101 m−1s−1 was 100-fold lower than the class C enzymes in this panel and ∼10,000-fold lower than the class A enzymes.

Deacylation Kinetics for Avibactam against Class A, C, and D β-Lactamases

The deacylation rates of avibactam in this enzyme panel also varied across β-lactamase classes. In the class A enzymes, CTX-M-15 and KPC-2, with half-lives for enzyme activity recovery of 40 and 82 min, respectively, were similar to each other and also to TEM-1. In the class C enzymes, for P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC the off-rate was ∼50-fold faster than E. cloacae P99 AmpC, resulting in half-lives of 6 and 300 min, respectively. The class D enzymes displayed slower off-rates than the class A and C enzymes. Between the two OXA enzymes, the rate of deacylation from OXA-10 was the slowest, with a half-life for enzyme recovery of >5 days. This off-rate is nearly 10-fold slower than OXA-48 and 1000-fold slower than TEM-1, CTX-M-15, or P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC.

Acyl Enzyme Stability

The identity and stability of the avibactam acyl enzymes was assessed by characterization of the enzyme-inhibitor complexes by ESI-MS. In these assays the enzymes were incubated with a 5:1 molar excess of avibactam for either 5 min or 24 h. Excess compound was removed by ultrafiltration before gathering the mass spectra of acyl enzyme species.

With all of the enzymes, the 5-min incubation time yielded mass increases that were consistent with stoichiometric acylation by avibactam, presumably through a carbamoyl linkage to the enzyme active site serine residues (Table 4). After incubation for 24 h, the acyl enzyme form of CTX-M-15 remained fully acylated, and the E. cloacae P99 AmpC was 93% acylated.

TABLE 4.

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) analysis of acylated avibactam-enzyme complexes

Acyl enzymes were prepared by incubation of 1 μm enzyme with 5 μm avibactam at 37 °C and removal of free compound by ultrafiltration.

| Enzyme | % Acylated after 5 min of incubation | % Acylated after 24 h of incubation |

|---|---|---|

| TEM-1 | 100 | 100 |

| CTX-M-15 | 100 | 100a |

| KPC-2 | 100 | 10 |

| E. cloacae P99 AmpC | 100 | 93 |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC | 100 | 71 |

| OXA-10 | 24b | 91 |

| OXA-48 | 100 | 97 |

a CTX-M-15 displayed loss of 17 Da due to the pyro-Glu formation at N terminus (38).

b OXA-10 reached 100% acylation after 3 h.

The P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC enzyme was substantially less than fully acylated (71%) after 24 h of incubation with avibactam. The reason for the decrease in % acylation can be traced to the experimental conditions and magnitudes of the binding constant. The relatively high Kd for avibactam binding to P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC (0.5 μm) and its fast off-rate (Table 3) permit equilibrium across the Kd, which manifests at 24 h as partially acylated enzyme. Unlike the deacylation experiment wherein a large dilution was employed to minimize inhibitor rebinding, the 24-h enzyme acylation data listed in Table 4 were conducted under conditions where inhibitor rebinding is possible.

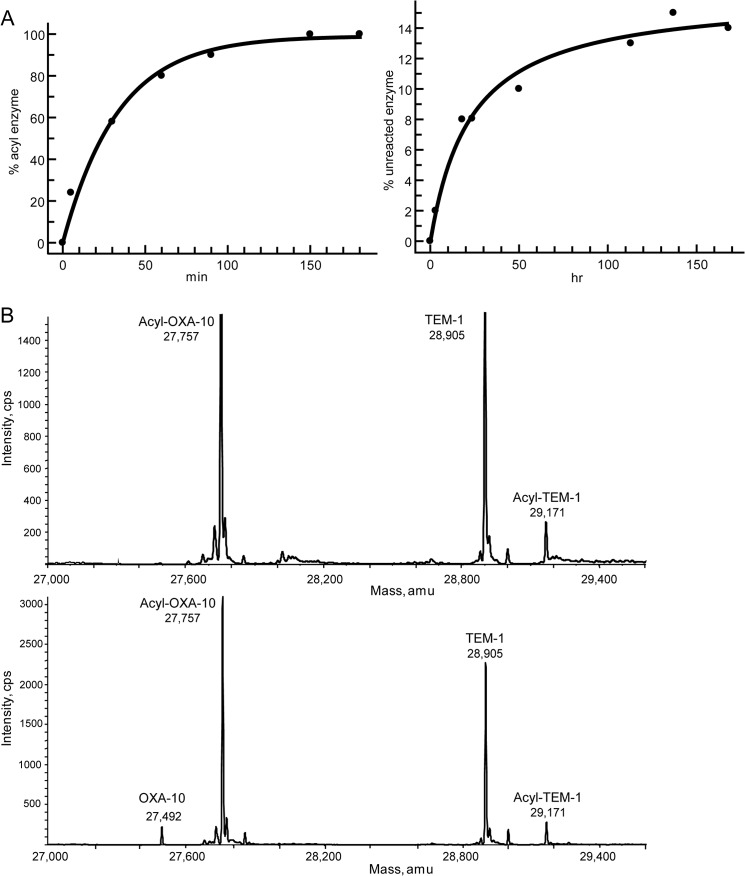

Within the OXA enzymes OXA-48 remained fully acylated at 24 h, whereas OXA-10 displayed 91% acyl enzyme. For OXA-10, however, the off-rate for deacylation is so slow that 24 h is not long enough to reach equilibrium. To illustrate this point, an acylation time course and a deacylation time course were performed with OXA-10. As seen in Fig. 2, the acylation of 1 μm OXA-10 by 5 μm avibactam reached completion after 2.5 h. Deacylation was monitored for 1 week and appeared to reach equilibrium after 7 days of incubation.

FIGURE 2.

A, acylation (left) and deacylation (right) time courses for avibactam reacting with OXA-10. B, acyl enzyme exchange from acyl-OXA-10 to TEM-1. Top, ESI-MS spectrum of acyl-OXA-10 incubated with TEM-1 for 25 h without bicarbonate. The appearance of acyl-TEM-1 in this spectrum may result from free avibactam present in the acyl-OXA-10 sample. Bottom, ESI-MS spectrum of acyl-OXA-10 incubated with TEM-1 for 25 h in the presence of 10 mm sodium bicarbonate.

OXA-10 Inhibition Follows a Slow Reversible Mechanism

The extremely slow off-rate of avibactam from OXA-10 prompted a test of whether the released compound was intact avibactam. We previously employed an acyl enzyme exchange experiment to assess this property (18). A similar experiment was designed with acyl-OXA-10 as the donor enzyme and again employing TEM-1 as the acceptor. To increase the initial fraction of acylated enzyme, in this experiment 5 μm OXA-10 and 25 μm avibactam were employed before excess inhibitor removal. As shown in Fig. 2, in the absence of the OXA-10 activator bicarbonate, incubation of acyl-OXA-10 with TEM-1 did not produce any additional acyl-TEM-1 or OXA-10. In the presence of bicarbonate, however, OXA-10 was produced, and the small amount of avibactam released from acyl-OXA-10 after 25 h was capable of acylating TEM-1, providing direct evidence that avibactam inhibition of OXA-10 is reversible. Even though this process is kinetically reversible, the extremely slow off-rate, with a projected half-life for recovery of >5 days, means that OXA-10 inhibition is essentially irreversible once the acyl enzyme has been achieved.

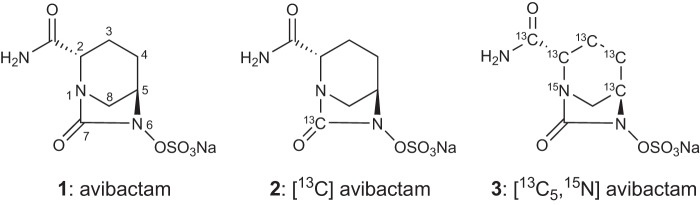

KPC-2 Deacylation Involves a Slow, Hydrolytic Pathway

In the mass spectrometry analysis, the KPC-2 acyl enzyme appeared to be nearly completely deacylated after 24 h. This was unexpected because other enzymes with similar avibactam Kd and off-rates remained acylated. An explanation for these findings is a slow hydrolytic pathway of deacylation from acyl-KPC-2, and to investigate this possibility, the time course of acyl enzyme decay was followed by ESI-MS from 0 to 30 h.

As seen in Fig. 3, in addition to the unreacted and acyl enzyme peaks, two new peaks appeared during the time course. These peaks correspond to the fully acylated enzyme that has lost 79 Da (acyl-79) and 98 Da (acyl-98). The changes in relative fractions of these peaks were plotted over the time course. From this plot, both of these acylated species with mass loss appear to be precursors to the fully deacylated enzyme.

FIGURE 3.

Time course of deacylation from KPC-2 followed by ESI-MS. A, excerpted time points displaying conversion of acyl-KPC-2 to unacylated KPC-2 and appearance of acyl-98 and acyl-79 peaks. B, plot of the relative fractions of KPC-2 and the three acylated forms over 32 h of incubation at 37 °C.

It is important to note that the acyl-79 peak has been seen with mass spectrometry analysis of avibactam attached to other β-lactamases (16, 17); however, in those cases the presence of the acyl-79 peak appeared to be dependent on the electrospray ionization conditions. Indeed in our analysis of the enzymes in this study, the proportion of acyl-79 species could be reduced by reducing the declustering potential from 80 to 30 V (data not shown), but importantly the percentage of acyl-79 did not change over time in comparing 5-min to 24-h incubations with CTX-M-15, the two AmpCs, and the two OXA enzymes. For the KPC-2 acyl enzyme, however, the appearance and intensity of the acyl-79 species was time-dependent, and this kinetic pattern of appearance and disappearance suggests that it is not a mass spectrometry analysis artifact.

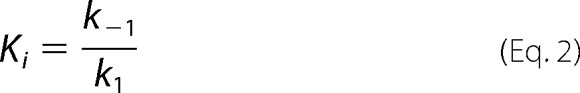

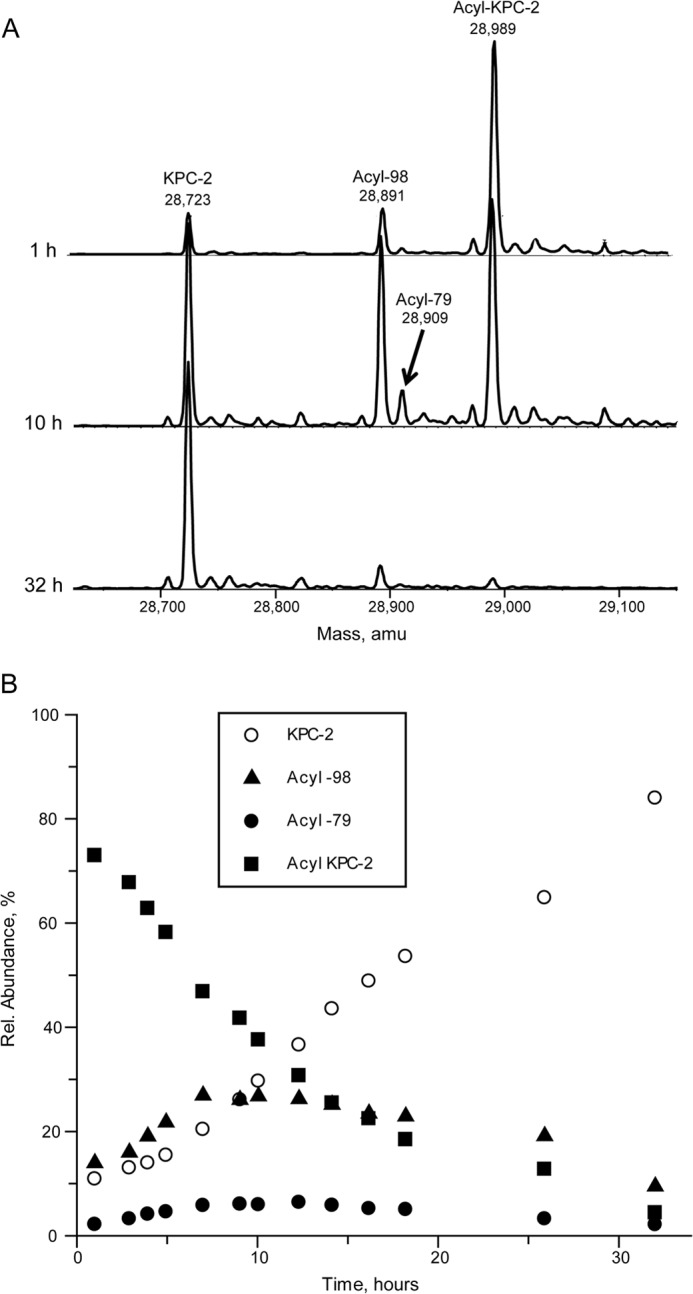

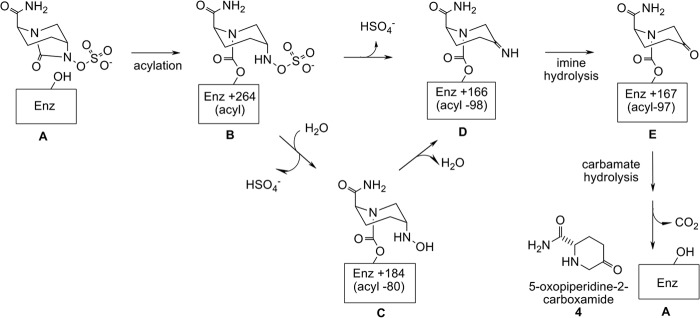

Reconciling the time-dependent mass losses with the chemical structure of the acylated, ring-opened form of avibactam localized the fragmentation to the sulfactam moiety (Fig. 4). Hydrolysis at the sulfactam O-S bond would convert the sulfactam to the hydroxylamine, resulting in an acyl-80 enzyme species (species C, Fig. 4). For the MS instrumentation employed in this analysis a discrepancy of 1 Da is within instrument error, and thus the acyl-79 peaks observed may in fact be acyl-80. Dehydration of the hydroxylamine from acyl-80 species C would produce the imine (species D, Fig. 4), resulting in an additional 18 Da loss that would appear as an acyl-98 MS peak. From the enzyme-bound imine species, several further transformations are conceivable either on or off of the enzyme. Fig. 4 shows one potential route where the imine group is hydrolyzed on the enzyme to the ketone and then released from the enzyme through hydrolysis of the carbamoyl tether to then undergo spontaneous decarboxylation to produce the ketopiperidine compound 4.

FIGURE 4.

Structures of acyl enzyme intermediates and avibactam modifications based on the species seen in the deacylation time course. The mass of enzyme (A) is increased by 264 Da upon acylation by avibactam (B). Hydrolytic loss of SO3 would produce the hydroxylamine and acyl-80 species (C) from which loss of water would produce the imine and acyl-98 species (D). Imine hydrolysis would produce the carbonyl and acyl-97 species (E). Hydrolysis of the carbamate linkage and subsequent decarboxylation would regenerate enzyme A and produce compound 4.

Identity of Avibactam Deacylation Products

The identity of the released and presumably fragmented form of avibactam was interrogated by NMR and high resolution mass spectrometry. For the NMR work isotopically labeled versions of avibactam were employed; one with a 13C at the urea carbonyl and one with 13C incorporated into the piperidine (Fig. 1).

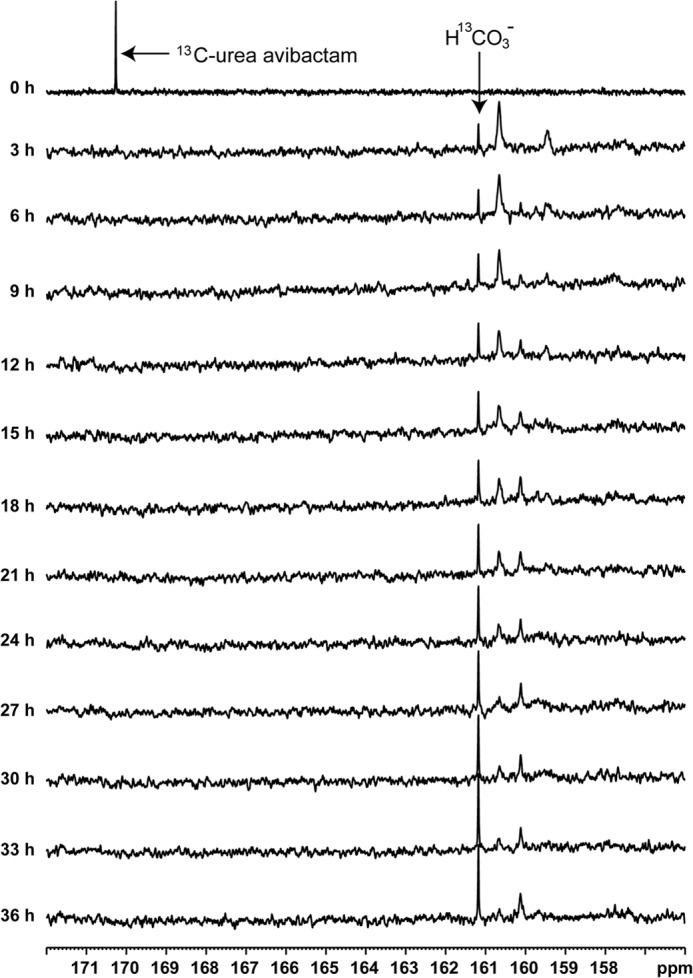

[13C]Urea avibactam in buffer alone displayed a singlet at 170 ppm. In the first 13C spectrum, after [13C]urea avibactam was mixed with an equimolar amount of KPC-2, the peak at 170 ppm disappeared and 3 new peaks were observed (Table 5 and Fig. 5). A sharp peak at 161.2 ppm is assigned as the resonance from bicarbonate (27), which results from spontaneous, presumably uncatalyzed hydrolysis of avibactam. The two other broad peaks at 160.7 and 159.5 ppm that appear upon acylation are tentatively assigned to the signals from acylated avibactam covalently attached to KPC-2. One possible explanation for the dual broad peaks is that one of these two peaks represents intact avibactam attached to KPC-2, whereas the other is a fragmented form of avibactam, either the acyl-98 or acyl-80 species.

TABLE 5.

13C chemical shifts observed upon incubation of [13C]urea avibactam (compound 2) with KPC-2

NMR spectra from the complete time course are shown in Fig. 5.

| Time | Chemical shift | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h | ppm | ||||

| 0 | 170 | ||||

| 3 | 161.2 | 160.7 | 159.5 | ||

| 12 | 161.2 | 160.7 | 160.1 | 159.5 | |

| 24 | 161.2 | 160.7 | 160.1 | ||

| 36 | 161.2 | 160.1 | |||

FIGURE 5.

13C chemical shifts observed upon incubation of [13C]urea avibactam (compound 2) with KPC-2 at 37 °C. The 0 h spectrum was taken before the addition of KPC-2. Chemical shifts from peaks at excerpted time points are shown in Table 5.

A new [13C]urea signal at 160.1 ppm emerged after the acylated KPC-2 sample had been incubated for 6 h. This signal intensity gradually increased over the 36-h time course, whereas the two peaks at 160.7 and 159.5 ppm dissipated and eventually disappeared. The 160.1 ppm peak is speculated to represent the released and fragmented hydrolysis product.

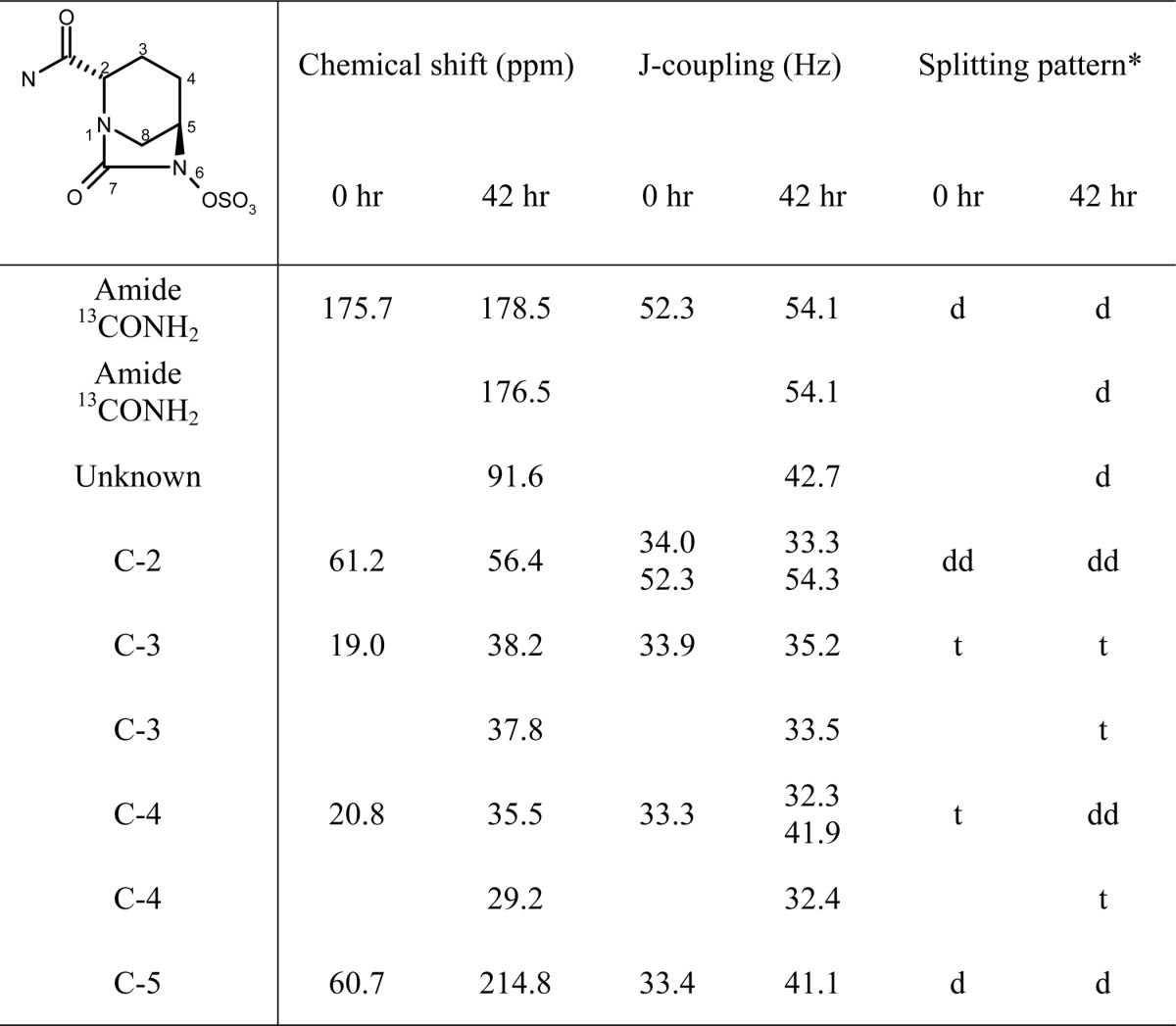

To obtain a more detailed picture of avibactam degradation in the presence of KPC-2, avibactam with five carbons enriched with 13C was synthesized (compound 3, Fig. 1). The assignment of the 13C resonances for the intact [13C5]avibactam (data not shown) was based on their chemical shifts and 13C-13C J-coupling patterns (28). After a 42-h incubation of [13C5]avibactam with KPC-2, the avibactam peaks had disappeared and were replaced by several new peaks (Table 6). Most notably, a new doublet appeared at 214.8 ppm, which is characteristic of a ketone. The splitting pattern of this new peak is consistent with its location at the C5 position. At three of the other labeled carbon positions (C3, C4, and the amide C), two separate peak patterns were seen, which suggests the formation of a second molecule derived from [13C5]avibactam. We were unable to assign a functional group to one of the new peaks, at 91.6 ppm. As a doublet, it is predicted to arise from the C5 position, although the chemical shift is unusually low for an imine or an enol/enamine.

TABLE 6.

13C NMR chemical shifts observed upon incubation of [3C5]avibactam (compound 3) with KPC-2 for 0 and 42 h

*, d, dd, and t stands for doublet, double doublet, and triplet, respectively.

The empiric formula of the ketone product was confirmed by high resolution mass spectrometry with non-isotopically labeled avibactam. An Orbitrap mass spectrometer was employed, which provides a high mass accuracy: 1–2 ppm using internal calibration. With the internal calibration method, the released product of a 30-h KPC-2-avibactam incubation was found to have a measured mass of 143.08147 (M+H)+. This mass matches an element composition of C6H11N2O2 (M+H)+, exact mass 143.08150. Accounting for protonation, the elemental composition of the product is C6H10N2O2, which corresponds to the desulfated and decarboxylated derivative of avibactam, the 5-oxopiperidine-2-carboxamide (compound 4 in Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

In this work, to delineate its spectrum of activity, the inhibition properties of avibactam against six β-lactamase enzymes are presented. Avibactam displayed the most potent activity against the two class A enzymes profiled. The rapid on-rates and moderately slow off-rates result in low nm Kd values for CTX-M-15 and KPC-2. The KPC-2 activity of avibactam is noteworthy because this enzyme is unusual in class A as being uninhibited by clavulanate and tazobactam (29, 30). The strong activity of avibactam against class A enzymes has been reinforced by microbiological profiling, which in addition to the TEM, CTX-M, and KPC enzyme families, have demonstrated excellent restoration of antibacterial activity against strains expressing SME and PER enzymes (31, 32).

The class C enzymes were exemplified by E. cloacae P99 AmpC and P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC in this study. Again, in microbiology profiling, avibactam combinations have displayed restoration of activity against class C-producing strains from Enterobacteriaceae and P. aeruginosa (32, 33). Among the two enzymes profiled here, acylation activity was similar between E. cloacae P99 AmpC and P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC. The P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC Kd of 0.66 μm is still capable of providing a high level of β-lactamase protection, as measured by restoration of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for β-lactam partners with avibactam (32, 34). Because the P. aeruginosa AmpC is chromosomally encoded, different strains carry different isoforms, and in some cases these variant AmpC enzymes display a different hydrolytic capacity from the PAO1 strain AmpC (35). With an altered catalytic profile, in conjunction with increased expression levels it is conceivable that avibactam inhibition may be diminished against certain P. aeruginosa strains possessing AmpC variants. This question could be addressed through profiling P. aeruginosa strains for avibactam MIC restoration in conjunction with inhibition analysis of the variant AmpC enzymes. It is worth noting that in the P. aeruginosa population MIC studies of hundreds of strains, the ceftazidime-avibactam combination has displayed potent MIC restoration, indicating that avibactam retains efficacy against the vast majority of AmpC-containing clinical strains (13, 34).

Compared with classes A and C, the class D OXA enzymes display a greater variation in their substrate profiles toward penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems. The two OXA enzymes profiled in this study exemplify this feature of class D; OXA-10 is a narrow-spectrum enzyme with greatest hydrolytic capacity against penicillins, whereas OXA-48 is a carbapenemase with lesser activity toward penicillins and cephalosporins (22). Whereas both OXA-10 and OXA-48 exhibit potent binding by avibactam at the Kd level, these enzymes exhibit slower reaction kinetics than the others studied. In the case of OXA-48, the on-rate is fast enough to result in a magnitude of k2/Ki inhibition efficiency that is comparable to the class C enzymes. Indeed avibactam has been shown to produce potent MIC restoration against OXA-48 producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (12). For OXA-10, however, the on-rate is so slow as to result in poor inhibition efficiency that is predicted to diminish the restorative effect of avibactam.

In considering the spectrum of microbiology activity of avibactam combinations across OXA enzymes, it is important to recognize the substrate specificity of each OXA enzyme. For example, if avibactam were combined with a good class D substrate, such as piperacillin, then efficacy would be predicted to be compromised against strains producing OXA-10 because of the pairing of a good β-lactam substrate with the weak BLI. Similarly, the combination of a carbapenem with avibactam could suffer against carbapenemase OXAs such as OXA-23, OXA-24, and OXA-58. On the other hand, ceftazidime is a poor substrate for almost all OXA-enzymes, including OXA-10, -23, -24, -40, -48, and -58 (22). Therefore, ceftazidime-avibactam likely retains activity against most OXA-producing strains, although this is more a function of the propensity of ceftazidime to evade OXA hydrolysis than the ability of avibactam to inhibit OXA enzymes. In this context it should be noted that blaOXA-48 frequently occurs together with genes encoding class A β-lactamases that can compromise the activity of ceftazidime in the absence of avibactam (22).

The rationalization of the differences in the kinetic parameters of avibactam inhibition across enzymes with structural determinants in the enzyme active sites is challenging for several reasons. First, there is a limited amount of avibactam-bound x-ray structural data upon which to build hypotheses; currently only the structures of avibactam bound to CTX-M-15, P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC (24), and the Mycobacterium tuberculosis BlaC (17). Second, the structures available are in acylated form and do not provide a view of the precovalent Michaelis complex. Third, the mechanistic details of substrate acylation and deacylation are still being uncovered, especially for class C and D enzymes (6).

Within these limitations, we can begin to rationalize some of the differences observed between class A and class C inhibition profiles using the available structures. The structures reveal two key features relevant to avibactam inhibition; that is, little conformation movement of the avibactam molecule upon ring-opening and minimal conformational differences between the unbound and bound forms of the enzymes. This together suggests that the differences in acylation rates preexist in the pocket attributes, which is mechanistically different from other inhibitors such as clavulanic acid (3, 37), penems (38), and phosphonates (37), where inactivation by the acylating inhibitors results in large rearrangements in either the compound or the protein or both. Thus, the slower acylation rate in class C compared with class A can be explained by the presence of additional loop residues in P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC (residues 314–321) that make the active site less accessible than in class A β-lactamases. As a consequence, in the AmpC enzymes this smaller pocket is predicted to reduce the binding affinity of the encounter complex.

Although we do not know the pre-covalent binding mode, in P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC versus CTX-M-15 the rates of recyclization suggest that pre- and post-covalent binding modes are likely to be similar. If this is the case, the differences in potencies between the two enzymes can be attributed to the fewer number of polar interactions observed in the covalently bound avibactam to P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC than in CTX-M-15. The fast recyclization with reversible ring closure in both classes is likely due to conservation of the closed-ring substrate-like conformation of avibactam upon covalent linkage to the enzyme. Future analysis of the structural differences between P. aeruginosa PAO1 AmpC, CTX-M-15, and class D enzymes will require additional acylated x-ray structures with OXA enzymes. From published structures of OXA enzymes, the observation that in OXA-10 and OXA-48 differences in the β5-β6 active site loops govern carbapenemase activity suggests that these differences also contribute to the differences in avibactam acylation rates (39).

Slow deacylation kinetics resulting in release of intact avibactam were observed for each β-lactamase in this study. For inhibitors with slow off-rates, it is assumed that a transition state must bridge the bound and unbound forms of the enzyme-inhibitor complex. In principle, the slow-off kinetics can result from the stabilization of the bound form or destabilization of the transition state (40). The large number of interactions seen between the protein and inhibitor in the acylated avibactam-bound x-ray structures suggests that the slow kinetics are driven by ground state stabilization; however, detailed mutational investigations and reaction thermodynamic modeling are warranted to support this claim.

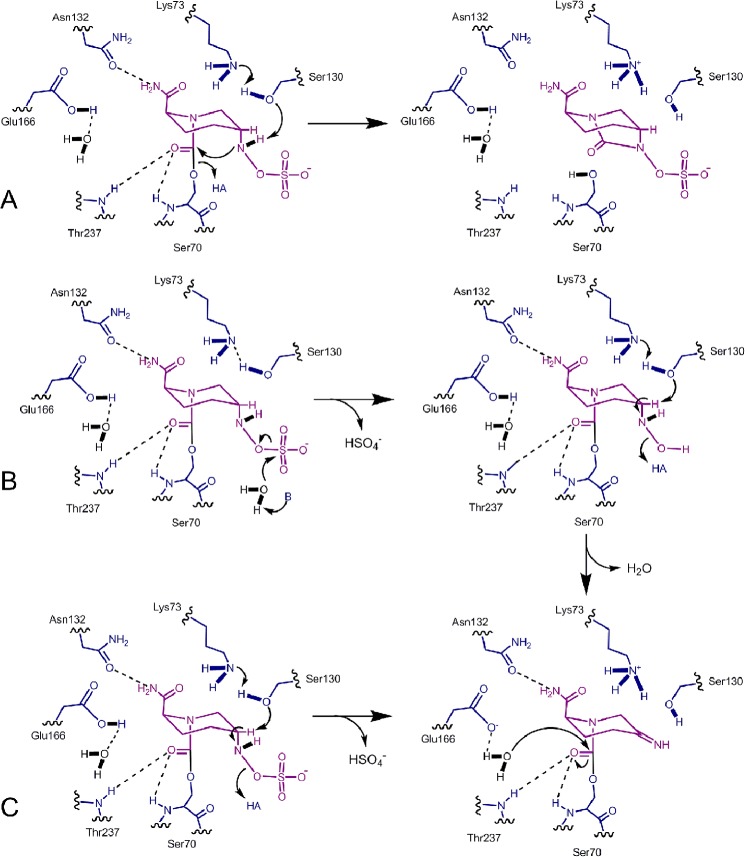

Among the enzymes studied, the KPC-2 enzyme displayed the unique capacity to slowly hydrolyze avibactam. Within the vast number of serine β-lactamases reported, KPC-2 displays one of the widest substrate profiles and the ability to efficiently hydrolyze the BLIs clavulanate and tazobactam (29). In the enzymes that displayed strictly reversible inhibition, as seen in CTX-M-15, the sulfactam nitrogen N6 is able to attack the carbamoyl carbonyl to reform intact avibactam (Fig. 6A). In KPC-2, the ring-closing chemistry occurs; however, it competes with desulfation and a hydrolytic route or routes. The observation of two intermediate acyl enzyme species that form from the fully acylated protein suggest that desulfation proceeds in two steps. Based on the class A CTX-M-15-acylated x-ray structure, a possible mechanism for the slow desulfation and hydrolysis seen in KPC-2 is presented in Fig. 6B. To account for the sulfactam hydrolysis to produce the enzyme-bound hydroxylamine, a water residue is invoked among several that are visible in both the acylated CTX-M-15 and native KPC-2 structures. The location of water residues in KPC-2 has been identified as critical to the enzyme hydrolytic capacity toward clavulanic acid (30). Further refinement of the deacylation mechanism of avibactam from KPC-2 will require acylated x-ray structures.

FIGURE 6.

Possible mechanisms for avibactam deacylation from KPC-2. The protein environment of acylated avibactam is based on the class A CTX-M-15 x-ray structure (PDB code 4HBU). A, the proposed ring-closing deacylation reaction to re-form intact avibactam in class A enzymes. B, proposed mechanism for sulfactam hydrolysis to produce the hydroxylamine avibactam fragment. C, proposed direct β-elimination of sulfate to produce the imine avibactam fragment.

Although the two-step mechanism for KPC-2 hydrolysis is suggested by the observation of the acyl-79 species, it is possible that a one-step direct elimination of the sulfate group is also occurring. A path to the one-step desulfation (Fig. 6C) involves abstraction of the proton on C5 by Ser130, resulting in imine formation by β-elimination of the sulfate group. It has been speculated that the sulfate group is critical for the anchoring of ring-opened avibactam with both the C2 carboxamide and the C5-substituted sulfactam in axial orientations, which contribute to protection against hydrolysis of the carbamoyl linkage. Without the sulfate anchor, the de-sulfo piperidine could then be susceptible to water attack at the carbamoyl enzyme tether, releasing the fragmented avibactam. Hydrolysis of the imine could occur on the enzyme or in solution; in either case spontaneous decarboxylation would result in the ketopiperidine product. The detection of the ketopiperidine product by NMR and high resolution mass spectrometry supports the hypothesis that this product accumulates at equilibrium upon slow release from the enzyme.

It is important to emphasize the extremely slow magnitudes of the KPC-2 deacylation rate, which, being on the order of hours, has minimal impact on the microbiological activity of avibactam β-lactam combinations toward KPC-2- producing bacteria. On the other hand, the observation of a new deacylation pathway for avibactam from one enzyme is relevant to the evolution of avibactam resistance in the diverse pool of β-lactamases found in clinical settings. In this context it is important to understand this mechanism, to uncover why it is peculiar to KPC-2 among the enzymes studied, and to assess the likelihood of new KPC-2 or class A derivatives evolving that possess increased hydrolytic rates.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Kathy MacCormack for DNA sequencing. Nick Bushby coordinated synthesis of isotopically labeled avibactam. Zhiping You aided with the statistical analysis of fitting.

This work is dedicated to Prof. Christopher T. Walsh on the occasion of his retirement.

- BLI

- β-lactamase inhibitor

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- MIC

- minimum inhibitory concentration

- RT

- room temperature.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shahid M., Sobia F., Singh A., Malik A., Khan H. M., Jonas D., Hawkey P. M. (2009) β-Lactams and β-lactamase-inhibitors in current or potential clinical practice. A comprehensive update. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 35, 81–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bebrone C., Lassaux P., Vercheval L., Sohier J. S., Jehaes A., Sauvage E., Galleni M. (2010) Current challenges in antimicrobial chemotherapy. Focus on β-lactamase inhibition. Drugs 70, 651–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Drawz S. M., Bonomo R. A. (2010) Three decades of β-lactamase inhibitors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23, 160–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bush K., Fisher J. F. (2011) Epidemiological expansion, structural studies, and clinical challenges of new β-lactamases from Gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 455–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bush K., Jacoby G. A. (2010) Updated functional classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 969–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fink A. L., Page M. I. (2012) in β-lactamases (Frere J., ed.) p. 161, Nova Science Publishers, New York [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bush K., Macielag M. J. (2010) New β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 20, 1277–1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shlaes D. M. (2013) New β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations in clinical development. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1277, 105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bush K. (2012) Improving known classes of antibiotics. An optimistic approach for the future. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 12, 527–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coleman K. (2011) Diazabicyclooctanes (DBOs). A potent new class of non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 550–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhanel G. G., Lawson C. D., Adam H., Schweizer F., Zelenitsky S., Lagacé-Wiens P. R., Denisuik A., Rubinstein E., Gin A. S., Hoban D. J., Lynch J. P., 3rd, Karlowsky J. A. (2013) Ceftazidime-avibactam. A novel cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor combination. Drugs 73, 159–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aktaş Z., Kayacan C., Oncul O. (2012) In vitro activity of avibactam (NXL104) in combination with β-lactams against Gram-negative bacteria, including OXA-48 β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 39, 86–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levasseur P., Girard A. M., Claudon M., Goossens H., Black M. T., Coleman K., Miossec C. (2012) In vitro antibacterial activity of the ceftazidime-avibactam (NXL104) combination against Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 1606–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dubreuil L. J., Mahieux S., Neut C., Miossec C., Pace J. (2012) Anti-anaerobic activity of a new β-lactamase inhibitor NXL104 in combination with β-lactams and metronidazole. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 39, 500–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bonnefoy A., Dupuis-Hamelin C., Steier V., Delachaume C., Seys C., Stachyra T., Fairley M., Guitton M., Lampilas M. (2004) In vitro activity of AVE1330A, an innovative broad-spectrum non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54, 410–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stachyra T., Péchereau M. C., Bruneau J. M., Claudon M., Frère J. M., Miossec C., Coleman K., Black M. T. (2010) Mechanistic studies of the inactivation of TEM-1 and P99 by NXL104, a novel non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 5132–5138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xu H., Hazra S., Blanchard J. S. (2012) NXL104 irreversibly inhibits the β-lactamase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry 51, 4551–4557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ehmann D. E., Jahić H., Ross P. L., Gu R. F., Hu J., Kern G., Walkup G. K., Fisher S. L. (2012) Avibactam is a covalent, reversible, non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 11663–11668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stachyra T., Levasseur P., Péchereau M. C., Girard A. M., Claudon M., Miossec C., Black M. T. (2009) In vitro activity of the β-lactamase inhibitor NXL104 against KPC-2 carbapenemase and Enterobacteriaceae expressing KPC carbapenemases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64, 326–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bush K. (2013) Proliferation and significance of clinically relevant β-lactamases. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1277, 84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patel G., Bonomo R. A. (2013) “Stormy waters ahead.” Global emergence of carbapenemases. Front. Microbiol. 4, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Poirel L., Naas T., Nordmann P. (2010) Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 24–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gupta N., Limbago B. M., Patel J. B., Kallen A. J. (2011) Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Epidemiology and prevention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 53, 60–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lahiri S. D., Mangani S., Durand-Reville T., Benvenuti M., De Luca F., Sanyal G., Docquier J. D. (2013) Structural insight into potent broad-spectrum inhibition with reversible recyclization mechanism. Avibactam in complex with CTX-M-15 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpC β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 2496–2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morrison J. F., Walsh C. T. (1988) The behavior and significance of slow-binding enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 61, 201–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miles R. W., Tyler P. C., Furneaux R. H., Bagdassarian C. K., Schramm V. L. (1998) One-third-the-sites transition-state inhibitors for purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biochemistry 37, 8615–8621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Golemi D., Maveyraud L., Vakulenko S., Samama J. P., Mobashery S. (2001) Critical involvement of a carbamylated lysine in catalytic function of class D β-lactamases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 14280–14285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Breitmaier E. (1999) Structure Elucidation by NMR in Organic Chemistry, pp. 49–52, John Wiley and Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- 29. Papp-Wallace K. M., Bethel C. R., Distler A. M., Kasuboski C., Taracila M., Bonomo R. A. (2010) Inhibitor resistance in the KPC-2 β-lactamase, a preeminent property of this class A β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 890–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papp-Wallace K. M., Taracila M. A., Smith K. M., Xu Y., Bonomo R. A. (2012) Understanding the molecular determinants of substrate and inhibitor specificities in the carbapenemase KPC-2. Exploring the roles of Arg-220 and Glu-276. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 4428–4438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Livermore D. M., Mushtaq S., Warner M., Zhang J., Maharjan S., Doumith M., Woodford N. (2011) Activities of NXL104 combinations with ceftazidime and aztreonam against carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 390–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mushtaq S., Warner M., Livermore D. M. (2010) In vitro activity of ceftazidime+NXL104 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other non-fermenters. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65, 2376–2381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Livermore D. M., Mushtaq S., Warner M., Miossec C., Woodford N. (2008) NXL104 combinations versus Enterobacteriaceae with CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases and carbapenemases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62, 1053–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Walkty A., DeCorby M., Lagacé-Wiens P. R., Karlowsky J. A., Hoban D. J., Zhanel G. G. (2011) In vitro activity of ceftazidime combined with NXL104 versus Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates obtained from patients in Canadian hospitals (CANWARD 2009 study). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 2992–2994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Drawz S. M., Taracila M., Caselli E., Prati F., Bonomo R. A. (2011) Exploring sequence requirements for C/C carboxylate recognition in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cephalosporinase. Insights into plasticity of the AmpC β-lactamase. Protein Sci. 20, 941–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kovach M. E., Elzer P. H., Hill D. S., Robertson G. T., Farris M. A., Roop R. M., 2nd, Peterson K. M. (1995) Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166, 175–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pratt R. (2012) in β-Lactamases (Frere J., Ed.) Nova Science Publishers, p. 259, New York [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bethel C. R., Taracila M., Shyr T., Thomson J. M., Distler A. M., Hujer K. M., Hujer A. M., Endimiani A., Papp-Wallace K., Bonnet R., Bonomo R. A. (2011) Exploring the inhibition of CTX-M-9 by β-lactamase inhibitors and carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 3465–3475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. De Luca F., Benvenuti M., Carboni F., Pozzi C., Rossolini G. M., Mangani S., Docquier J. D. (2011) Evolution to carbapenem-hydrolyzing activity in noncarbapenemase class D β-lactamase OXA-10 by rational protein design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18424–18429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jencks W. P. (1997) From chemistry to biochemistry to catalysis to movement. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66, 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]