Abstract

There is abundant evidence that dysfunction of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic signaling system is implicated in the pathology of schizophrenia and mood disorders. Less is known about the alterations in protein expression of GABA receptor subunits in brains of subjects with schizophrenia and mood disorders. We have previously demonstrated reduced expression of GABAB receptor subunits 1 and 2 (GABBR1 and GABBR2) in the lateral cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. In the current study, we have expanded these studies to examine the mRNA and protein expression of 12 GABAA subunit proteins (α1, α2, α3, α5, α6, β1, β2, β3, δ, ɛ, γ2 and γ3) in the lateral cerebella from the same set of subjects with schizophrenia (N=9–15), bipolar disorder (N=10–15) and major depression (N=12–15) versus healthy controls (N=10–15). We found significant group effects for protein levels of the α2-, β1- and ɛ-subunits across treatment groups. We also found a significant group effect for mRNA levels of the α1-subunit across treatment groups. New avenues for treatment, such as the use of neurosteroids to promote GABA modulation, could potentially ameliorate GABAergic dysfunction in these disorders.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, GABRα2, GABRβ1, GABRɛ, major depression, schizophrenia

Introduction

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain and regulates multiple processes during the brain development. Approximately 20% of all central nervous system neurons are GABAergic.1 Hypofunction of the GABAergic signaling system has been hypothesized to contribute to the pathologies of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.2, 3, 4, 5 Multiple laboratories have demonstrated a number of dysfunctions of the GABAergic signaling system in these disorders, including: (1) altered expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 kDa proteins,6, 7, 8 the enzymes that convert glutamate to GABA; (2) microarray results that have demonstrated increased mRNA for a number of GABA(A) (GABAA) receptor subunits in prefrontal cortex (PFC) of subjects with schizophrenia;9, 10, 11 and (3) gene association studies that link GABA receptor subunits to schizophrenia and mood disorders.12, 13, 14

Structural and functional abnormalities of the cerebellum have been described for schizophrenia, depression and bipolar disorder, including reduced cerebellar volumes.15, 16, 17 Reduced cerebellar activation has also been observed in functional imaging studies of subjects with these disorders.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 There is abundant evidence that the cerebellum has roles in cognition and emotion.15,20,24 Circuits connecting the cerebellum with other brain regions, such as the cortico-thalamic-cerebellar-cortical circuit, which may monitor execution of mental activity, have also shown disruption in schizophrenia.24, 25, 26, 27

There is also evidence of GABAergic hypofunction in the cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia and mood disorders.6 Glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 kDa proteins have been shown to be reduced in the lateral cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.6 In the granule cell layer of the cerebellum, Bullock et al.28 found reduced mRNA for glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 kDa along with increased expression of mRNA for GABAA receptor α6- and δ-subunits. Finally, reduced protein expression of GABAB receptor subunits 1 and 2 (GABBR1 and GABBR2) has been observed in the lateral cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression.29

Although there have been some mRNA studies of GABAA receptor expression in subjects with schizophrenia,28, 30, 31, 32, 33 there is a paucity of data regarding GABAA receptor protein expression in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Here we expand our previous work on the GABAergic signaling system in these disorders to investigate protein expression of 12 additional GABAA receptor subunits: GABRα1, GABRα2, GABRα3, GABRα5, GABRα6, GABRβ1, GABRβ2, GABRβ3, GABRδ, GABRɛ, GABRγ2 and GABRγ3. On the basis of our finding of significantly reduced GABAB receptor subunits in the lateral cerebella,29 we hypothesized that we would observe reduced expression of multiple GABAA receptor subunits in the same brain region of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression.

Materials and Methods

Brain procurement

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota School of Medicine has approved this study. Post-mortem cerebella (lateral posterior lobe) were obtained from the Stanley Foundation Neuropathology Consortium under approved ethical guidelines. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition diagnoses were established before death by neurologists and psychiatrists by using information from all available medical records and from family interviews. Details regarding the subject selection, demographics, diagnostic process and tissue processing were collected by the Stanley Medical Research Foundation. The collection consisted of 9–15 subjects with schizophrenia, 10–15 subjects with bipolar disorder, 12–15 with major depression without psychotic features and 10–15 normal controls (Table 1). All groups were matched for age, sex, race, post-mortem interval and hemispheric side (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic information for the four diagnostic groups.

| Bipolar | Depression | Control | Schizophrenia | F or χ2-test | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.33 (11.72) | 46.53 (9.31) | 48.07 (10.66) | 44.53 (13.11) | 0.73 | 0.54 |

| Sex | 6 F, 9 M | 6 F, 9 M | 6 F, 9 M | 6 F, 9 M | 0 | 1.0 |

| Race | 14 W, 1 B | 15 W | 14 W, 1 B | 12 W, 3 A | 14.7 | 0.10 |

| PMI | 32.53 (16.12) | 27.47 (10.73) | 23.73 (9.95) | 33.67 (14.62) | 1.85 | 0.15 |

| pH | 6.18 (0.23) | 6.18 (0.22) | 6.27 (0.24) | 6.16 (0.26) | 0.60 | 0.62 |

| Side of brain | 7 L, 8 R | 9 L, 6 R | 7 L, 8 R | 9 L, 6 R | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| Brain weight | 1441.2 (171.5) | 1462 (142.1) | 1501 (164.1) | 1471.7 (108.2) | 0.42 | 0.74 |

| Family history | 0.93 (0.8) | 0.73 (0.46) | 0.13 (0.52) | 1.13 (0.83) | 29.84 | 0.0001 |

| Suicidal death | 9 (5 Violent) | 9 (4 Violent) | 0 | 6 (2 Violent) | 15.9 | 0.014 |

| Drug/alcohol history | 0.8 (0.77) | 0.4 (0.63) | 0.33 (0.72) | 0.53 (0.74) | 6.42 | 0.38 |

| Age of onset | 21.47 (8.35) | 33.93 (13.29) | — | 23.2 (7.96) | 3.61 | 0.001 |

| Duration | 20.13 (9.67) | 12.67 (11.06) | — | 21.67 (11.24) | 0.034 | 0.86 |

| Severity of substance abuse | 1.93 (1.98) | 1.07 (1.98) | 0.13 (0.52) | 1.20 (1.86) | 2.82 | 0.046 |

| Severity of alcohol abuse | 2.27 (1.98) | 1.8 (2.01) | 1.07 (1.03) | 1.47 (1.59) | 1.34 | 0.27 |

| Fluphenazine (lifetime) | 20,826.67 (24,015.96) | — | — | 52,266.67 (62,061.57) | 3.35 | 0.078 |

| Alcohol dependence | 13.3% | 13.3% | 0% | 0% | 4.29 | 0.23 |

| Alcohol abuse | 6.7% | 6.7% | 0% | 0% | 1.05 | 0.79 |

| Substance dependence | 6.7% | 0% | 0% | 6.7% | 2.07 | 0.56 |

| Substance abuse | 20.0% | 6.7% | 0% | 6.7% | 4.15 | 0.25 |

| Antidepressant use | 53.3% | 60.0% | 0% | 33.3% | 14.1 | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: A, Asian; B, Black; F, female; L, left; M, male; PMI, postmortem interval; R, right; W, Whites.

Rating scale for drug/alcohol history: 0, never; 1, current; 2, past. Rating scale for severity of substance abuse: 0, little/none; 1, social; 2, moderate use/past; 3, moderate use/present; 4, heavy use/past; 5, heavy use/present. Rating scale for severity of alcohol abuse: 0, little/none; 1, social (one to two drinks per day); 2, moderate use/past; 3, moderate use/present; 4, heavy use/past; 5, heavy use/present.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and western blotting

Brain tissue was prepared as previously described.29, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 Thirty micrograms of the lateral cerebellum was used per lane. For all experiments, we used 10% resolving gels and 5% stacking gels. To minimize interblot variability, we included samples from subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression and healthy controls on each gel, and all samples were run in duplicate. Samples were electrophoresed for 15 min at 75 V, followed by 60 min at 150 V. Samples were then electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes for 2 h at 300 mAmp at 4 °C. Blots were blocked with 0.2% I-Block (Tropix, Bedford, MA, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 0.3% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature followed by an overnight incubation in primary antibodies at 4 °C. The primary antibodies used were anti-GABRα1 (06–868; Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA; 1:1000), anti-GABRα2 (GAA21; Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX, USA; 1:500), anti-GABRα3 (GAA31; Alpha Diagnostic International; 1:1000), anti-GABRα5 (AB10098; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA; 1:500), anti-GABRα6 (AB5610; Millipore; 1:250), anti-GABRβ1 (AB9680; Millipore; 1:500), anti-GABRβ2 (AB5561; Millipore; 1:500), anti-GABRβ3 (ab98968; Abcam; 1:5000), anti-GABRδ (AB37396; Abcam; 1:500), anti-GABRɛ (ab35971; Abcam; 1:1000), anti-GABRγ2 (NB-300-192; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA; 1:500), anti-GABRγ3 (NB100-56662; Novus Biologicals; 1:500), anti-neuronal specific enolase (NSE) (ab16808; Abcam; 1:2000) and anti-β actin (A5441; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA; 1:5000). Following primary antibody incubation, blots were washed for 30 min in phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 0.3% Tween 20 for 30 min at room temperature, and were subsequently incubated in the proper secondary antibodies. Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit IgG (A9169; Sigma Aldrich; 1:80 000) or goat anti-mouse IgG (A9044; Sigma Aldrich; 1:80 000). Blots were probed together (three to four gels per experiment). Following secondary antibody incubation, blots were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 0.3% Tween 20 for 15 min each. The immune complexes were then visualized using the ECL Plus detection system (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and exposed to CL-Xposure film (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). The molecular weights of ∼58 kDa (GABRβ3, upper band), 56 kDa (GABRβ3 lower band), 55 kDa (GABRα3, GABRβ1), 52 kDa (GABRα5, GABRβ2), 51 kDa (GABRα1, GABRα2, GABRδ, GABRγ3), 50 kDa (GABRα6), 46 kDa (NSE), 45 kDa (GABRɛ, GABRγ2) and 42 kDa (β-actin) immunoreactive bands were quantified with background subtraction using a Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) densitometer and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The molecular weight of GABRβ3 has been reported previously as anywhere from 52 kDa to 58 kDa.34, 35, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Using Abcam antibody ab98968, we obtained a doublet of 56 kDa and 58 kDa, similar to results obtained by Bureau and Olsen40 who identified a doublet of 55 kDa and 58 kDa. For this study, we decided to measure both bands. Sample densities were analyzed, blind to nature of diagnosis. Results obtained are based on at least two independent experiments.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed as previously described.37 Raw data were analyzed as previously described,37 using the Sequence Detection Software RQ Manager (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA), whereas relative quantitation using the comparative threshold cycle (CT method) was performed in a Bioconductor using the ABqPCR package in Microsoft Excel (ABI Technote#2: Relative Gene Expression Quantitation). Calculations were done assuming that 1 delta Ct equals a twofold difference in expression. Significance values were determined using unpaired Student's t-tests. The probe IDs used were as follows: (1) GABRA1 (GABRα1): Hs0068058-m1; (2) GABRA2 (GABRα2): Hs00168069-m1; (3) GABRA3 (GABRα3): Hs00968132_m1; (4) GABRA5 (GABRα5): Hs00181291-m1; (5) GABRA6 (GABRα6): Hs00181301_m1; (6) GABRB1 (GABRβ1): Hs00181306_m1; (7) GABRB2 (GABRβ2): Hs00241451_m1; (8) GABRB3 (GABRβ3): Hs00241459-m1; (9) GABRD (GABRδ): Hs00181309_m1; (10) GABRE (GABRɛ): Hs00608332_m1; (11) GABRG2 (GABRγ2): Hs00168093_m1; (12) GABRG3 (GABRγ3): Hs00264276-m1; (13) β-actin: Hs99999903_m1; and (14) glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase: Hs99999905_m1.

Statistical analysis

All protein measurements for each group were normalized against β-actin and NSE (Tables 2 and 3) and were expressed as ratios. Statistical analysis was performed as previously described,29, 36, 38 with P<0.05 considered significant. Group comparisons were conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Follow-up independent Student's t-tests were then conducted as well. Group differences on possible confounding factors were explored using χ2-tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Where group differences were found, analysis of covariance was used to explore these effects on group differences for continuous variables and factorial ANOVA with interaction terms for categorical variables. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v.17 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Table 2. Western blotting results for GABAA receptor subunits expressed as a ratio of β-actin in the lateral cerebella.

|

ANOVA |

Control |

Schizophrenia |

Bipolar disorder |

Major depression |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral cerebellum | F-test | P-value | Protein | P-value | Protein | P-value | Protein | P-value | Protein | P-value |

| GABRα1/β-actin | 1.46 | NC | 0.331±0.127 | RG | 0.507±0.311 | NC | 0.474±0.266 | NC | 0.486±0.252 | 0.049 |

| GABRα2/β-actin | 3.35 | 0.027 | 0.126±0.083 | RG | 0.370±0.282 | 0.0046 | 0.321±0.273 | 0.017 | 0.271±0.154 | 0.0047 |

| GABRα3/β-actin | 0.46 | NC | 0.196±0.076 | RG | 0.239±0.159 | NC | 0.236±0.161 | NC | 0.193±0.14 | NC |

| GABRα5/β-actin | 2.02 | NC | 0.031±0.02 | RG | 0.063±0.067 | NC | 0.04±0.03 | NC | 0.033±0.018 | NC |

| GABRα6/β-actin | 1.76 | NC | 0.013±0.003 | RG | 0.015±0.007 | 0.23 | 0.016±0.009 | NC | 0.019±0.005 | 0.001 |

| GABRβ1/β-actin | 6.03 | 0.001 | 0.135±0.049 | RG | 0.066±0.031 | 0.0001 | 0.092±0.048 | 0.026 | 0.092±0.047 | 0.023 |

| GABRβ2/β-actin | 1.56 | NC | 0.035±0.013 | RG | 0.030±0.016 | NC | 0.025±0.008 | 0.025 | 0.034±0.016 | NC |

| GABRβ3 (upper) /β-actin | 2.01 | NC | 0.114±0.136 | RG | 0.058±0.063 | NC | 0.152±0.084 | NC | 0.109±0.103 | NC |

| GABRβ3 (lower) /β-actin | 0.77 | NC | 0.57±0.16 | RG | 0.59±0.14 | NC | 0.60±0.19 | NC | 0.50±0.21 | NC |

| GABRδ/β-actin | 0.46 | NC | 0.032±0.017 | RG | 0.034±0.015 | NC | 0.027±0.021 | NC | 0.034±0.017 | NC |

| GABRɛ/β-actin | 8.88 | 0.0001 | 0.015±0.007 | RG | 0.035±0.029 | 0.044 | 0.041±0.018 | 0.0006 | 0.079±0.046 | 0.0003 |

| GABRγ2/β-actin | 0.74 | NC | 0.016±0.008 | RG | 0.015±0.009 | NC | 0.012±0.005 | NC | 0.012±0.006 | NC |

| GABRγ3/β-actin | 1.53 | NC | 0.099±0.052 | RG | 0.114±0.059 | NC | 0.137±0.072 | NC | 0.141±0.055 | 0.047 |

| β-actin | 0.83 | NC | 25.8±2.07 | RG | 25.2±2.07 | NC | 26.9±2.91 | NC | 26.1±4.38 | NC |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; GABAA, γ-aminobutyric acid (A); NC, no change; RG, reference group.

Bold entries are significant P values.

Table 3. Western Blotting Results for GABAA receptor subunits expressed as a ratio of NSE in lateral cerebella.

|

ANOVA |

Control |

Schizophrenia |

Bipolar disorder |

Major depression |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral cerebellum | F-test | P-value | Protein | P-value | Protein | P-value | Protein | P-value | Protein | P-value |

| GABRα1/NSE | 1.19 | NC | 0.45±0.19 | RG | 0.60±0.28 | NC | 0.60±0.28 | NC | 0.56±0.21 | NC |

| GABRα2/NSE | 3.49 | 0.022 | 0.14±0.09 | RG | 0.32±0.19 | 0.0042 | 0.28±0.17 | 0.011 | 0.31±0.19 | 0.0063 |

| GABRα3/NSE | 0.81 | NC | 0.25±0.11 | RG | 0.25±0.17 | NC | 0.29±0.16 | NC | 0.21±0.10 | NC |

| GABRα5/NE | 2.00 | NC | 0.036±0.023 | RG | 0.071±0.076 | NC | 0.043±0.029 | NC | 0.037±0.020 | NC |

| GABRα6/NSE | 1.79 | NC | 0.026±0.007 | RG | 0.037±0.023 | NC | 0.031±0.018 | NC | 0.040±0.011 | 0.0023 |

| GABRβ1/NSE | 4.53 | 0.007 | 0.17±0.07 | RG | 0.084±0.048 | 0.001 | 0.11±0.064 | 0.034 | 0.11±0.066 | 0.03 |

| GABRβ2/NSE | 1.35 | NC | 0.039±0.015 | RG | 0.036±0.020 | NC | 0.028±0.007 | 0.022 | 0.035±0.013 | NC |

| GABRβ3 (upper) /NSE | 1.97 | NC | 0.11±0.13 | RG | 0.063±0.069 | NC | 0.16±0.10 | NC | 0.11±0.098 | NC |

| GABRβ3 (lower) /NSE | 1.80 | NC | 0.63±0.13 | RG | 0.65±0.13 | NC | 0.57±0.11 | NC | 0.55±0.13 | NC |

| GABRδ/NSE | 1.46 | NC | 0.038±0.022 | RG | 0.046±0.026 | NC | 0.028±0.016 | NC | 0.038±0.019 | NC |

| GABRɛ/NSE | 7.26 | 0.001 | 0.017±0.009 | RG | 0.037±0.032 | NC | 0.041±0.017 | 0.0013 | 0.084±0.056 | 0.0012 |

| GABRγ2/NSE | 0.40 | NC | 0.03±0.014 | RG | 0.029±0.018 | NC | 0.024±0.010 | NC | 0.029±0.021 | NC |

| GABRγ3/NSE | 1.33 | NC | 0.12±0.06 | RG | 0.13±0.08 | NC | 0.17±0.11 | NC | 0.16±0.07 | NC |

| NSE | 0.93 | NC | 20.2±2.34 | RG | 20.1±1.67 | NC | 20.2±3.34 | NC | 21.6±2.87 | NC |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; GABAA, γ-aminobutyric acid (A); NC, no change; NSE, neuronal specific enolase; RG, reference group.

Bold entries represent significant P values.

Results

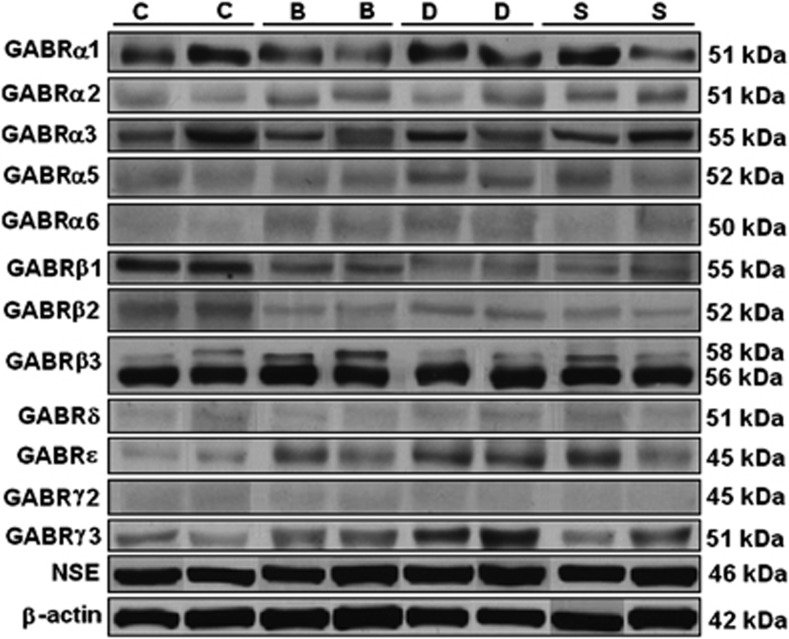

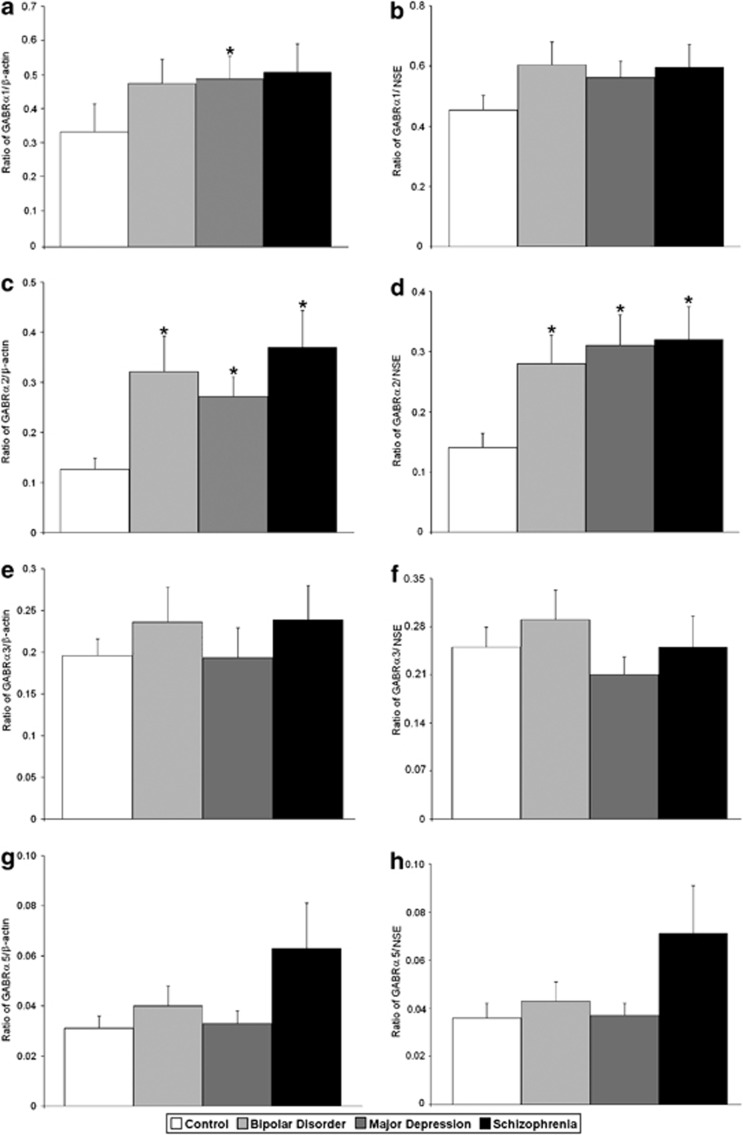

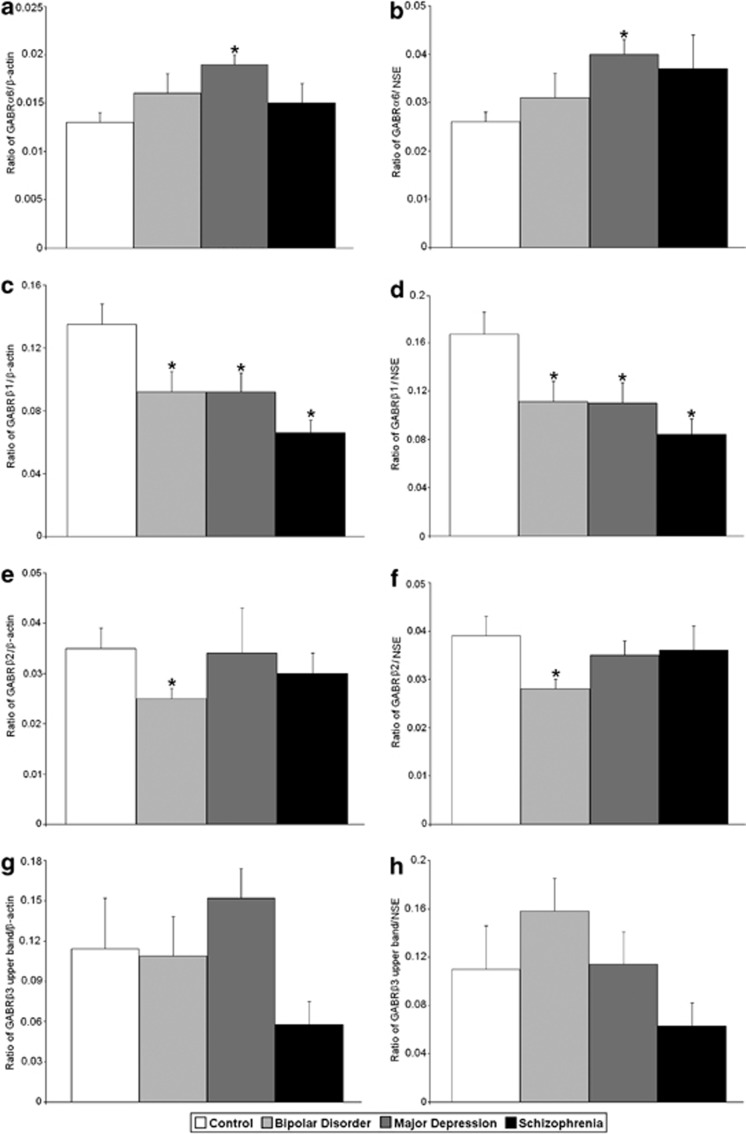

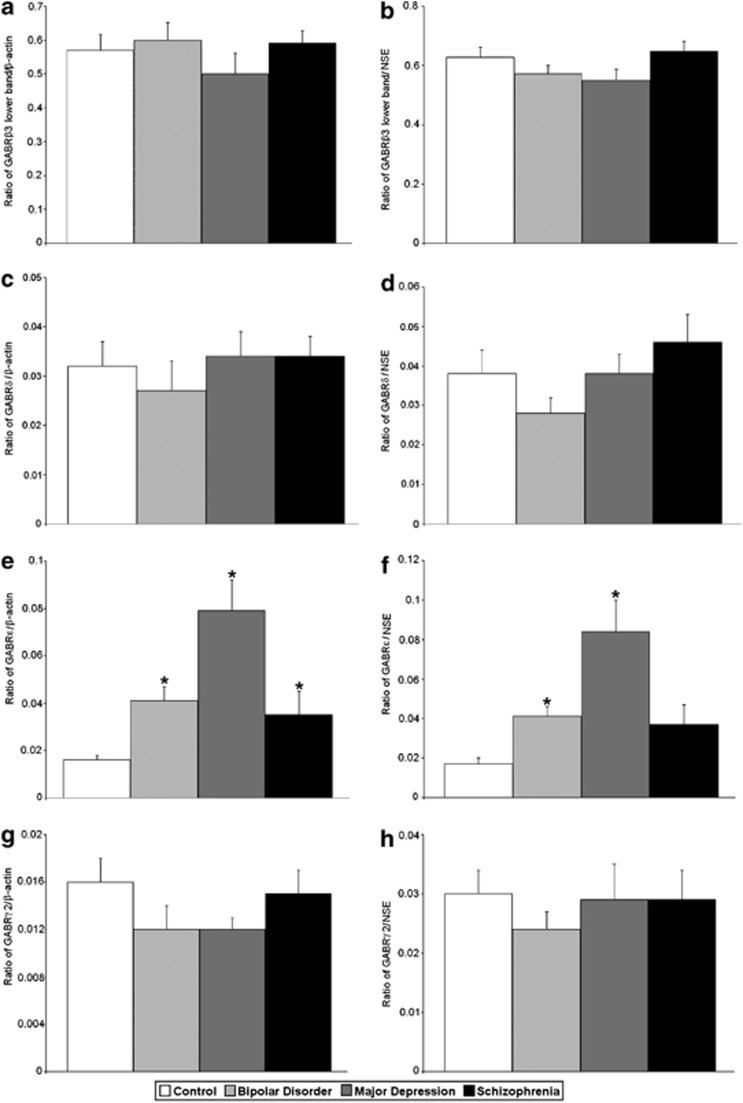

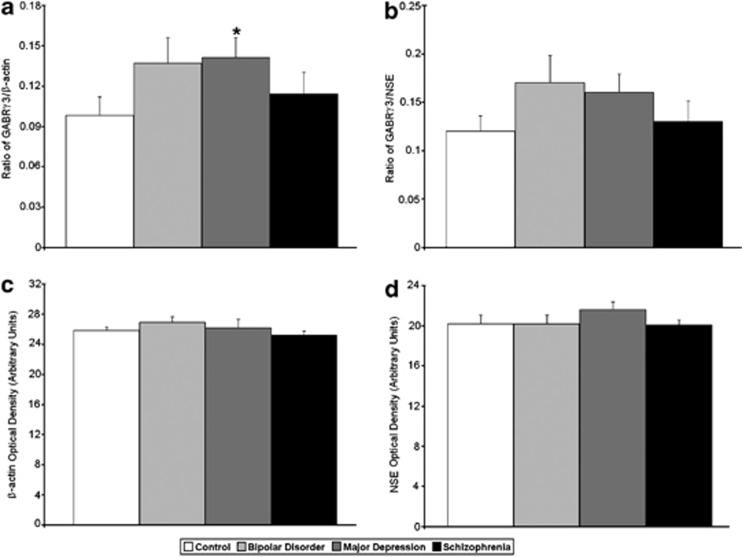

All protein measurements were normalized against β-actin and NSE (Figure 1). ANOVA identified group differences for GABRα2/β-actin (F(3,52)=3.35, P<0.027), GABRα2/NSE (F(3,52)=3.49, P<0.022), GABRβ1/β-actin (F(3,54)=6.03, P<0.001), GABRβ1/NSE (F(3,54)=4.53, P<0.007), GABRɛ/β-actin (F(3,37)=8.88, P<0.0001) and GABRɛ/NSE (F(3,37)=7.26, P<0.001) (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 1, 2, 3, 4). In subjects with schizophrenia, follow-up Student's t-tests found significantly increased expression of GABRα2/β-actin (P<0.0046), GABRα2/NSE (P<0.0042) and GABRɛ/β-actin (P<0.044) (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 1, 2 and 4), and significantly reduced expression of GABRβ1/β-actin (P<0.0001) and GABRβ1/NSE (P<0.001) (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 1 and 3).

Figure 1.

Representative bands for GABRα1, GABRα2, GABRα3, GABRα5, GABRα6, GABRβ1, GABRβ2, GABRβ3, GABRδ, GABRɛ, GABRγ2, GABRγ3, NSE and β-actin in the lateral cerebellum of subjects with schizophrenia and mood disorders.

Figure 2.

Expression of GABRα1/β-actin (a), GABRα1/NSE (b), GABRα2/β-actin (c), GABRα2/NSE (d), GABRα3/β-actin (e), GABRα3/NSE (f), GABRα5/β-actin (g) and GABRα5/NSE (h) in the lateral cerebella of healthy control subjects versus subjects with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Histogram bars shown as mean±s.e., *P<0.05.

Figure 3.

Expression of GABRα6/β-actin (a), GABRα6/NSE (b), GABRβ1/β-actin (c), GABRβ1/NSE (d), GABRβ2/β-actin (e), GABRβ2/NSE (f), GABRβ3 upper band/β-actin (g) and GABRβ3 upper band/NSE (h) in the lateral cerebella of healthy control subjects versus subjects with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Histogram bars shown as mean±s.e., *P<0.05.

Figure 4.

Expression of GABRβ3 lower band/β-actin (a), GABRβ3 lower band/NSE (b), GABRδ/β-actin (c), GABRδ/NSE (d), GABRɛ/β-actin (e), GABRɛ/NSE (f), GABRγ2/β-actin (g) and GABRγ2/NSE (h) in the lateral cerebella of healthy control subjects versus subjects with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Histogram bars shown as mean±s.e., *P<0.05.

In subjects with bipolar disorder, follow-up Student's t-test found significantly increased expression of GABRα2/β-actin (P<0.017), GABRα2/NSE (P<0.011), GABRɛ/β-actin (P<0.0006) and GABRɛ/NSE (P<0.0013) (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 1 and 4), and significantly reduced expression of GABRβ1/β-actin (P<0.026) and GABRβ1/NSE (P<0.034) (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 1 and 3). We also observed significantly reduced expression of GABRβ2/β-actin (P<0.025) and GABRβ2/NSE (P<0.022) in the cerebella of subjects with bipolar disorder (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 1 and 3).

In subjects with major depressive disorder, follow-up Student's t-tests found significantly upregulated expression of GABRα2/β-actin (P<0.0047), GABRα2/NSE (P<0.0063), GABRɛ/β-actin (P<0.0003) and GABRɛ/NSE (P<0.0012) (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 1, 2, and 4), and significantly reduced expression of GABRβ1/β-actin (P<0.023) and GABRβ1/NSE (P<0.03) (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 1 and 3). We found that GABRα1/β-actin expression was significantly increased in the cerebella of subjects with major depression (P<0.049) (Table 2; Figures 1 and 2). In addition, there were significantly increased expression for GABRγ3/β-actin (P<0.047; Table 2; Figures 1 and 5), GABRα6/β-actin (P<0.001) and GABRα6/NSE (P<0.0023) (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 5.

Expression of GABRγ3/β-actin (a), GABRγ3/NSE (b), β-actin (c) and NSE (d) in the lateral cerebella of healthy control subjects versus subjects with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Histogram bars shown as mean±s.e., *P<0.05.

No significant differences were found between diagnostic groups on hemisphere side, ethnicity, history of substance abuse, gender, severity of alcohol abuse, brain weight, post-mortem interval, age, or pH. We did find that subjects with bipolar disorder had significantly higher levels of severity of substance use than did normal controls (P<0.046). We also compared the three diagnostic groups on family history and suicide, and found a significant increased rate of suicide among the psychiatric groups when compared with controls (P<0.0001 and P<0.014, respectively). Age of onset was significantly later (33.9 years) for depressed subjects when compared with schizophrenics (23.2) and bipolar subjects (21.5), (P<0.001). Finally, antidepressant use was significantly different between the four groups (P<0.003). ANOVAs controlling for hemisphere side, ethnicity, history of substance abuse, severity of substance abuse, gender, severity of alcohol abuse, brain weight, post-mortem interval, age or pH found no meaningful or significant impact on the results reported above.

When we controlled for antidepressant use, we lost significance for GABRα2/β-actin in subjects with major depression (P<0.068); GABRβ1/β-actin in subjects with bipolar disorder (P<0.46); GABRβ2/β-actin in subjects with bipolar disorder (P<0.061); GABRγ3/β-actin in subjects with major depression (P<0.25); and GABRβ1/NSE in subjects with major depression (P<0.15) (Supplementary Table 1). However, we found no significant differences between values for individuals taking antidepressants versus those not taking antidepressants within each diagnostic group for GABRα2/β-actin, GABRβ2/β-actin, GABRγ3/β-actin and GABRβ1/NSE (P<0.74, P<0.98, P<0.68; and P<0.76, respectively), suggesting that antidepressant use had no real impact on these measures (Supplementary Table 2). Subjects with bipolar disorder, who took antidepressants, had significantly lower protein levels of GABRβ1/β-actin when compared with subjects with bipolar disorder, who did not take antidepressants (t(12)=2.47, P<0.030), suggesting that in this case antidepressant use was partially responsible for the reduction in GABRβ1/β-actin (Supplementary Table 2). However, the GABRβ1/NSE ratio continued to be significantly lower in the bipolar group (P<0.034) and was not affected by the antidepressant confound.

We found that alcohol dependence, alcohol abuse, substance dependence and substance abuse did not impact any of our data (Table 1). However, as an additional analysis, we removed subjects with alcohol dependence/abuse or subjects with substance dependence/abuse, and reanalyzed the data. When individuals with substance abuse were removed, significance was lost for GABRγ3/β-actin (P<0.072) in subjects with major depression and GABRβ1/NSE (P<0.063) in subjects with bipolar disorder (Supplementary Table 3). When individuals with substance dependence were removed, none of the values lost significance (Supplementary Table 4). When individuals with alcohol abuse were removed, significance was lost for GABRα1/β-actin (P<0.076) and GABRγ3/β-actin (P<0.072) in subjects with major depression and GABRβ1/NSE (P<0.061) in subjects with bipolar disorder (Supplementary Table 5). Finally, when individuals with alcohol dependence were removed, all values for individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder remained significant, whereas in subjects with major depression significance was lost for GABRα1/β-actin (P<0.063), GABRβ1/β-actin (P<0.061), GABRβ1/NSE (P<0.063) and GABRγ3/β-actin (P<0.061) (Supplementary Table 6). However, as none of the above confound effects were significant, the above changes are not deemed meaningful.

We performed quantitative real-time PCR to investigate changes in mRNA for the 12 GABAA receptor subunits (Table 4). ANOVA found a significant group difference for GABRA1 (GABRα1; P<0.012) with significantly reduced mRNA for GABRA1 in the lateral cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia (P<0.011) and major depression (P<0.009; Table 4). In subjects with schizophrenia, we also observed a significant reduction in mRNA for GABRA2 (GABRα2) (P<0.017) and a significant increase in mRNA for GABRB3 (GABRβ3; Table 4) (P<0.044).

Table 4. mRNA expression for 12 GABAA receptor subunits in the lateral cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia and mood disorders.

|

Schizophrenia |

Bipolar disorder |

Major depression |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANOVA | Fold change | P-value | Fold change | P-value | Fold change | P-value | |

| GABRA1 | 0.012 | 0.713 | 0.011 | 0.949 | 0.707 | 0.618 | 0.009 |

| GABRA2 | 0.126 | 0.563 | 0.017 | 0.688 | 0.111 | 0.688 | 0.099 |

| GABRA3 | 0.505 | 0.531 | 0.139 | 0.589 | 0.289 | 0.865 | 0.599 |

| GABRA5 | 0.118 | 0.754 | 0.127 | 1.094 | 0.621 | 0.735 | 0.206 |

| GABRA6 | 0.385 | 0.994 | 0.967 | 0.674 | 0.210 | 0.789 | 0.217 |

| GABRB1 | 0.684 | 0.997 | 0.989 | 0.781 | 0.319 | 0.937 | 0.743 |

| GABRB2 | 0.866 | 1.113 | 0.644 | 0.915 | 0.784 | 1.128 | 0.583 |

| GABRB3 | 0.232 | 1.473 | 0.044 | 1.317 | 0.115 | 1.375 | 0.071 |

| GABRD | 0.233 | 0.678 | 0.051 | 0.602 | 0.101 | 0.887 | 0.632 |

| GABRE | 0.400 | 1.046 | 0.859 | 1.320 | 0.196 | 0.905 | 0.639 |

| GABRG2 | 0.238 | 1.118 | 0.419 | 0.758 | 0.168 | 0.888 | 0.461 |

| GABRG3 | 0.188 | 0.785 | 0.373 | 0.877 | 0.625 | 0.450 | 0.081 |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; C, control; GABAA, γ-aminobutyric acid (A); S, schizophrenia; B, bipolar disorder; D, major depression.

Note: ANOVA based on six comparisons: C versus S, C versus B, C versus D, S versus B, S versus D and B versus D.

Bold entries represent significant fold changes and P values.

Discussion

The salient, significant findings for this work include the following: (1) novel significant increases in protein levels for ɛ- and α2-receptors in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression; (2) novel significant decreases in protein levels for β1-receptor in all three disorders; (3) significant increases in protein levels for α1-, α6- and γ3-receptors in major depression; (4) significant decrease in protein level for β2-receptor in bipolar disorder; (5) significant decrease in mRNA for α2 and increase in β3 in schizophrenia; (6) significant decrease in mRNA for α1 in subjects with schizophrenia and major depression; and (7) absence of any major confound effects on obtained protein and mRNA results, with the exception of antidepressant use on protein levels of GABRβ1/β-actin in subjects with bipolar disorder.

In rat brain, GABRα2 mRNA is distributed in multiple regions, including the neocortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus and cerebellum.44, 45 In the cerebellum, GABRα2 mRNA was identified on Bergman glial cells.44, 45, 46 We identified significantly increased expression of GABRα2 protein in all three groups, whereas subjects with schizophrenia displayed decreased expression of GABRα2 mRNA. The decreased expression of GABRα2 mRNA may indicate a potential feedback loop effect. Consistent with our findings, GABRα2 mRNA and protein has been observed to be upregulated in postsynaptic pyramidal cell membranes in the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) of subjects with schizophrenia.47 It has been hypothesized that this increased expression is a compensatory response to deficits in GABA synthesis in presynaptic chandelier subclass of GABAergic neurons.48 In a recent study of cross-frequency modulation in subjects with schizophrenia versus matched controls, greater ‘aberrant' fronto-temporal modulation observed in patients with schizophrenia was correlated with polymorphisms of the GABRA2 (α2) gene.49 Moreover, recent studies have shown that positive modulators of GABRα2 can improve working memory in a monkey model of schizophrenia50 and in humans.51 However, a separate study found no benefit of the GABRα2-positive modulator MK-0777 for patients with schizophrenia on tests of working memory.52

The GABRα2 gene (GABRA2), which is localized to 4q13–p12,53 has been associated with risk for alcohol dependence54, 55 and drug abuse.56, 57, 58 Although we did not find a significant effect of severity of alcohol abuse, or history of alcohol or substance abuse, we did observe a significant difference for severity of substance abuse in subjects with bipolar disorder. Others have suggested that altered expression of GABRα2 may help explain comorbid substance abuse in subjects with schizophrenia.2 To date, there are no reports of an association between GABRA2 with bipolar disorder or major depression. However, a recent set of experiments comparing GABRA2 heterozygous and homozygous knockout mice with wild–type mice have found that males lacking the α2-subunit displayed depressive symptoms during the forced swimming test, the novelty suppressed-feeding test and the tail suspension test.59 These results have led the authors to conclude that GABAergic inhibition acting through receptors that include the α2-subunit has a potential antidepressant-like effect.59

The gene for GABRɛ clusters at Xq28 (Table 5) with genes for the α3- and θ-subunits.60 mRNA for the ɛ-subunit has been identified in the septum, thalamus, hypothalamus and amygdala in rat brain and was often coexpressed with mRNA for the θ-subunit;61 however, it was not found in the cerebellum.62 GABAA receptors that include GABRɛ have been shown to be insensitive to benzodiazepines63, 64 and overexpression of GABRɛ has shown to result in insensitivity to anesthetics.65 Our finding of increased expression of GABRɛ in the lateral cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder represents the first such protein data on this subunit in these disorders. In addition, the absence of any mRNA changes indicate that the altered receptor protein expression is likely secondary to posttranslation deficits in processing of ɛ-receptors in all three disorders. The altered expression may change the pharmacological properties of GABAA receptors in this region, leading to altered neurotransmission.

Table 5. Summary of mRNA and protein levels for selected GABAA and GABAB receptor subunits in cerebella from subjects with three major psychiatric disorders.

|

Schizophrenia |

Bipolar disorder |

Major depression |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subunit | Chromosomal location | M | P | M | P | M | P |

| GABRα1 | 5q34–q35 | ↓ | NC | NC | NC | ↓ | ↑ |

| GABRα2 | 4q13–p12 | ↓ | ↑ | NC | ↑ | NC | ↑ |

| GABRα3 | Xq28 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| GABRα5 | 15q11.2–q13 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| GABRα6 | 5q31.1–q35 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | ↑ |

| GABRβ1 | 4q13–p12 | NC | ↓ | NC | ↓ | NC | ↓ |

| GABRβ2 | 5q34–q35 | NC | NC | NC | ↓ | NC | NC |

| GABRβ3 | 15q11.2–q13 | ↓ | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| GABRδ | 1p36.3 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| GABRɛ | Xq28 | NC | ↑ | NC | ↑ | NC | ↑ |

| GABRγ2 | 15q31.1–q33.1 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| GABRγ3 | 15q11.2–q13 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | ↑ |

| GABBR11 | 6p21.3 | NC | ↓ | NC | ↓ | NC | ↓ |

| GABBR21 | 6q12–q21 | NC | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | NC | ↓ |

Abbreviations: GABBR1, GABAB receptor subunit 1; GABBR2, GABAB receptor subunit 2; M, mRNA; NC, no change; P, protein.

GABBR1 and GABBR2 data reprinted from Fatemi et al.,29 with permission from Elsevier.

To the best of our knowledge, we are the first laboratory to observe significant reduction of GABRβ1 protein in brains of subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depression. GABRβ1 mRNA localizes to multiple brain regions, with strong expression in the hippocampus of rat, as well as in the amygdala and cerebellar granular cells.45 Previous studies have found no changes in mRNA for GABRβ1 in PFC of subjects with schizophrenia when compared with controls.30, 66 Our observed reduction may signify regional changes in the β1-subunit expression. Moreover, recent genetic studies have implicated GABRB1 (β1) in bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder and major depression.67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72 Finally, GABRB1 has been associated with the risk of alcohol dependence.73, 74 Again, as no mRNA effects were seen, all β1 protein changes may be due to posttranslational processing deficits intracellularly.

GABRA6, the gene that codes for the GABRα6 subunit is localized to 5q31.1–q35.75 In studies from the rat brain, GABRα6 mRNA was found to localize exclusively to the cerebellar granule neurons.44, 76 We observed increased expression of GABRα6/β-actin and GABRα6/NSE protein in the lateral cerebella of subjects with major depression only, with no changes in either schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Polymorphisms of GABRA6 have been shown to have significant associations with mood disorders in females.77 Moreover, a single-nucleotide polymorphism of GABRA6 (rs1992647) has been associated with antidepressant response in a Chinese population sample.78 A study by Petryshen et al.14 associated a variant of GABRA6 with schizophrenia, whereas a separate study found no association.79 Interestingly, a recent study identified a single-nucleotide polymorphism of GABRA6 (rs3219151) that is associated with decreased risk of schizophrenia.80 Thus, significant α6 protein expression in major depression may signify a specific marker for this disorder.

The gene for GABRα1 is located at 5q34–q35.53 The α1-subunit is expressed in a majority of GABAA receptors and has a wide distribution, including the neocortex, hippocampus, globus pallidus, medial septum, thalamus and cerebellum.45 Within the cerebellum, mRNA for the α1-subunit is localized to the stellate/basket cells, Purkinje cells and granule cells.44, 45, 46 We observed a significant decrease in mRNA levels for GABRα1 in the cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia and major depression, whereas we found a significant increase in the GABRα1/β-actin protein in subjects with major depression. Several groups have identified reduced expression of GABRα1 in PFC from subjects with schizophrenia,30, 31, 66 whereas a separate study found no change.81 Glausier and Lewis82 further identified selective reduction of GABRα1 mRNA in pyramidal cells located in layer 3 of the PFC, whereas there was no change in GABRα1 mRNA levels in interneurons in the same layer. Our results are the first to show a similar reduction in the cerebella from subjects with schizophrenia or major depression. A previous study has failed to find a linkage between GABRA1 variants and major depression;83 however, other studies have associated this gene with bipolar disorder84 and schizophrenia.33

The gene that codes for GABRγ3 (GABRG3) localizes to the 15q11.2–q13 site, where it clusters with the genes for GABRα5 (GABRA5) and GABRβ3 (GABRB3).85 mRNA for the γ3-subunit localizes to the cerebellar granule cells, as well as the neocortex, caudate putamen and nucleus accumbens among other regions.44, 45 Although no genetic associations between GABRG3 and schizophrenia and bipolar disorders have been identified, a single-nucleotide polymorphism of GABRG3 (rs2376481) has been linked to female suicide attempters.86 Similar to GABRA2 and GABRB1, GABRG3 may be associated with alcohol dependence.87 Our finding of a significant increase in expression of GABRγ3/β-actin in the lateral cerebella of subjects with major depression is thus novel and potentially interesting in light of γ3 being a potential risk gene for suicide.

The gene for GABRβ2 (GABRB2) is located at 5q34–q35, where it clusters with the genes for GABRα1 (GABRA1) and GABRγ2 (GABRG2).88 The β2-subunit mRNA has been found in the olfactory bulb, neocortex, globus pallidus, thalamus and cerebellar granule cells.44, 45 Recently, GABRB2 has been associated with both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.89, 90, 91 Two novel isoforms of GABRB2, β(2S1) and β(2S2) have also been associated with male subjects with bipolar disorder.89 Moreover, Zhao et al.,89 by using quantitative real-time PCR, found that in post-mortem brain, there was significantly increased mRNA for β(2S1) in the DLPFC of subjects with bipolar disorder and significantly reduced mRNA for β(2S2) in DLPFC of subjects with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. A separate group has also recently observed a reduction in mRNA for the β2-subunit in DLPFC of subjects with schizophrenia.30

As previously mentioned, the gene that codes GABRβ3 (GABRB3) clusters at 15q11.2–q13, with GABRA5 and GABRG3. GABRβ3 mRNA has been found in multiple brain areas, including the olfactory bulb, neocortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus and cerebellum.44, 45 In the cerebellum, mRNA for the β3-subunit has been found in both Purkinje cells and granule cells.44, 46 An association between GABRB3 and schizophrenia has been documented in two recent studies.92, 93 A previous study has shown that mRNA for GABRβ3 is not changed in DLPFC of subjects with schizophrenia.30 However, we found increased mRNA for GABRβ3 in the lateral cerebella from subjects with schizophrenia, suggesting regional differences. Although we did not find any changes in GABRβ3 protein expression, we have previously found reduction of GABRβ3 protein levels in the cerebella of subjects with autism.34, 94

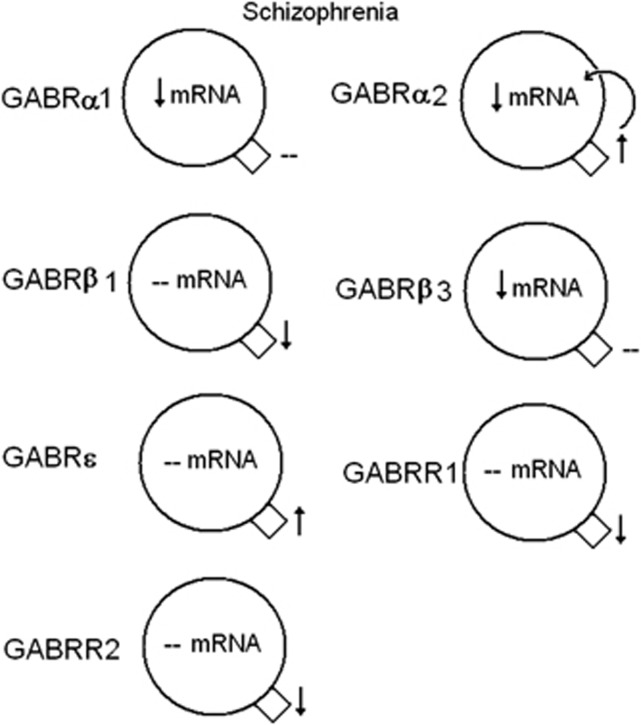

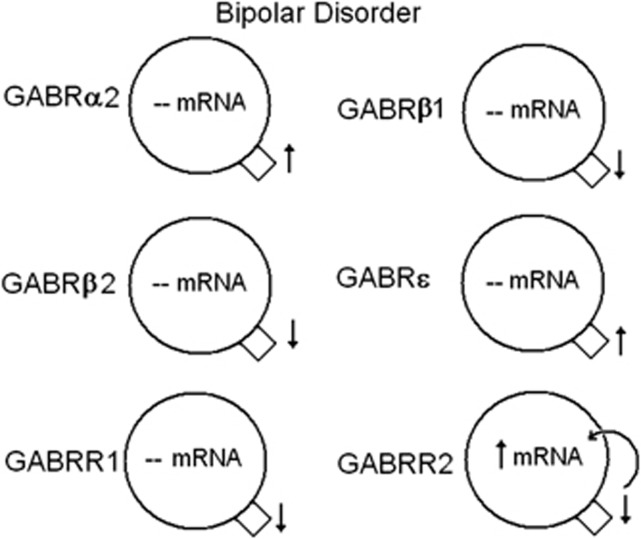

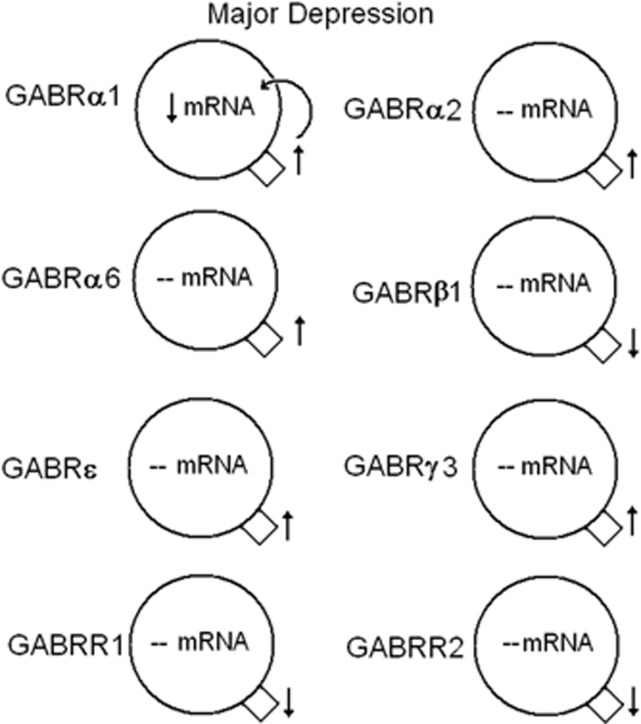

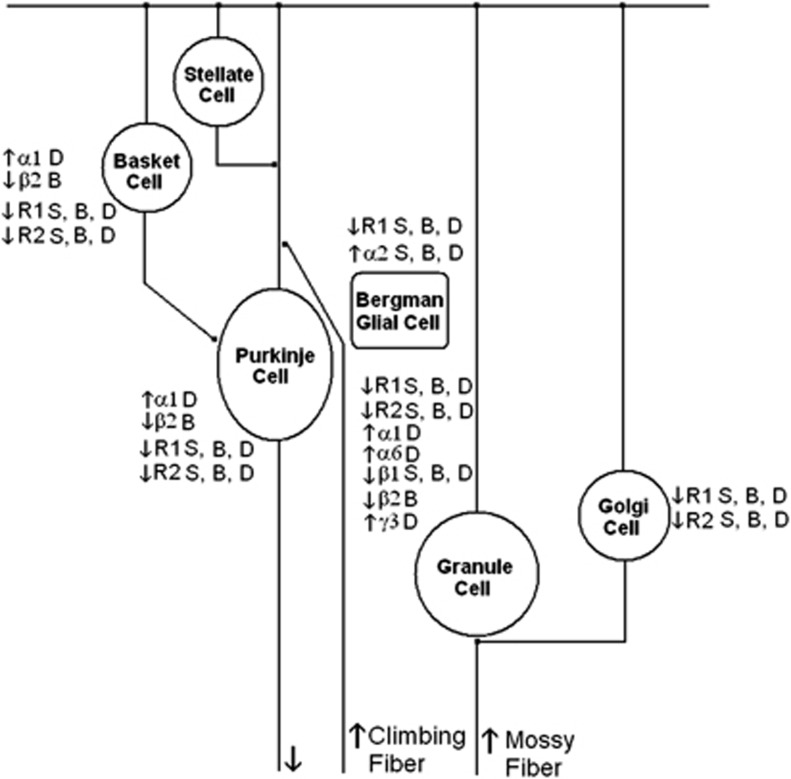

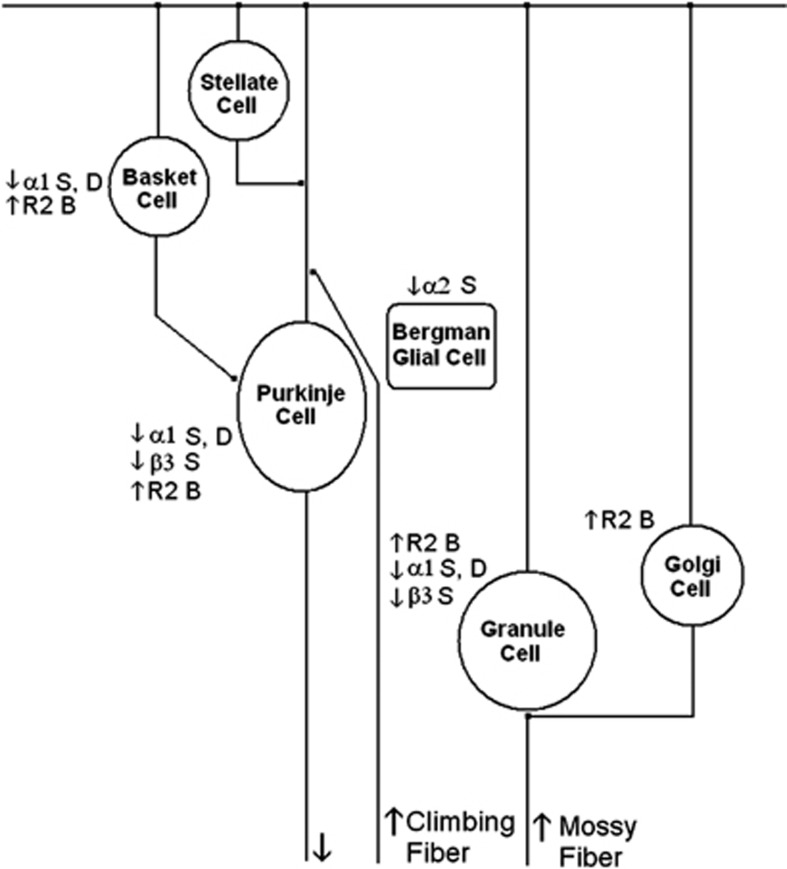

Overall, we observed significant increased expression of α2- and ɛ-subunit protein levels in all three disorders. In addition, we observed decreased protein expression for β1 in all three disorders and α1 mRNA in schizophrenia and major depression. (Figures 6, 7, 8, 9; Table 5). We have previously shown reduced expression of GABBR1 and GABBR2 in the lateral cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression (Table 5; Figures 6, 7, 8, 9, 10).29 With regard to mRNA expression, α- and β-subunits showed reduced expression, whereas GABBR2 displayed increased expression (Figures 6, 7, 8 and 10; Table 5). These changes may result in improper GABAergic transmission, both within the cerebellum and in circuits connecting the cerebellum with other parts of the brain, including the PFC. Functional consequences of impaired GABAergic transmission are likely to include dysregulated states of anxiety, panic and deficits in learning.95, 96, 97 Deficits in GABAB receptor expression may contribute to deficits in information processing in schizophrenia, including abnormalities in prepulse inhibition and P50 suppression.98, 99, 100, 101 Moreover, altered expression of GABAA and GABAB subunits may affect the pharmacological properties of the receptors, altering their ability to respond to drugs, such as anesthetics, benzodiazepines and neurosteroids. Taken together, the changes that were consistent across the three diagnostic groups—GABRα2, GABRβ1, GABRɛ, GABBR1 and GABBR2—may help explain similarities between these disorders.

Figure 6.

Summary of significant mRNA and protein expression for γ-aminobutyric acid A and B (GABAA and GABAB) receptors in the lateral cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia. Increased expression of GABRα2 protein may lead to a negative feedback loop decreasing the mRNA expression. ↑, increased expression; ↓, reduced expression, --, no change. GABAB receptor subunits 1 and 2 (GABBR1 and GABBR2) data reprinted from Fatemi et al.,29 with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 7.

Summary of significant mRNA and protein expression for γ-aminobutyric acid A and B (GABAA and GABAB) receptors in the lateral cerebella of subjects with bipolar disorder. Decreased expression of GABAB receptor subunit 2 (GABRR2) protein may lead to a positive feedback loop increasing the mRNA expression. ↑, increased expression; ↓, reduced expression, --, no change. GABAB receptor subunit 1 (GABBR1) and GABBR2 data reprinted from Fatemi et al.,29 with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 8.

Summary of significant mRNA and protein expression for γ-aminobutyric acid A and B (GABAA and GABAB) receptors in the lateral cerebella of subjects with major depression. Increased expression of GABRα1 protein may lead to a negative feedback loop decreasing the mRNA expression. ↑, increased expression; ↓, reduced expression, --, no change. GABAB receptor subunits 1 and 2 (GABBR1 and GABBR2) data reprinted from Fatemi et al.,29 with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 9.

Altered protein expression of γ-aminobutyric acid A and B (GABAA and GABAB) receptor subunits in various cells of the cerebellar circuitry of subjects with schizophrenia (S), bipolar disorder (B) or major depression (D). R1, GABAB receptor 1; R2, GABAB receptor 2. GABAB receptor subunits 1 and 2 (GABBR1 and GABBR2) data reprinted from Fatemi et al.,29 with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 10.

Altered mRNA expression of γ-aminobutyric acid A (GABAA) receptor subunits in various cells of the cerebellar circuitry of subjects with schizophrenia (S), bipolar disorder (B) or major depression (D). R2, GABAB receptor 2. GABAB receptor subunits 1 and 2 (GABBR1 and GABBR2) data reprinted from Fatemi et al.,29 with permission from Elsevier.

Our findings build upon previous work to examine GABA receptor subunit expression in brains of subjects with psychiatric disorders. Although most of the previously discussed findings are from the PFC,30, 31, 47, 66, 89 less is known of the cerebellum.28, 29 We found no change in mRNA expression for GABRα6 and GABRδ in the cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia, which are in contrast to the findings of Bullock et al.28 who found increased mRNA expression for both subunits. A potential explanation for this discrepancy may be due to the anatomic location of the cerebellar tissue used for both sets of experiments. Bullock et al.28 describe their tissue as being from the lateral cerebellar hemisphere corresponding to crus I of lobule VIIa, whereas ours is described as a ‘lateral posterior lobe'. Just as each subunit has a unique distribution among the cell types in the cerebellum (Figures 9 and 10),44, 45 there may be regional differences in GABA subunit expression throughout the cerebellum.

As targets of several psychotropic agents including benzodiazepines and neurosteroids, GABAA receptors are sites of potential therapeutic intervention. Experiments in rodents have shown that chronic treatment with atypical antipsychotic drugs clozapine and olanzapine result in increased levels of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone to a concentration large enough to stimulate GABAA receptors.102 In a rat model, injection of allopregnanolone into the hippocampus improved prepulse inhibition.103 Pregnenolone, the biosynthetic precursor of allopregnanolone has also been shown to increase concentrations of allopregnanolone in patients with schizophrenia.104 Schizophrenic patients with higher levels of allopregnanolone displayed significantly improved cognition as measured by the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia and significantly improved negative symptoms as measured by Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms.104 Treatment with antidepressants fluoxetine and fluvoxamine has also been shown to increase levels of allopregnanolone in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients diagnosed with major depression.105 Neurosteroid treatment may provide new means of treating GABA deficits in these disorders.

Conclusion

The examination of mRNA and protein levels for 12 GABAA receptor gene families in the lateral cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia and mood disorders showed significant increases in α2-and ɛ-, and decreases in β1-receptor protein expression in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression. In addition, several important alterations were observed in mRNA or protein levels for α1-, α6-, β2-, β3- and γ3-receptor subtypes in some of these disorders. These results, combined with our previous findings of reductions in GABAB receptor subunits, provide further evidence of GABAergic dysfunction in schizophrenia and mood disorders, which could ultimately underlie some of the cognitive, psychotic and mood dysfunctions associated with these disorders. Our findings may also open the door to new, targeted, therapeutic treatments, such as the use of neurosteroids.

Acknowledgments

Grant support by the National Institutes of Mental Health (grant number 1R01MH086000-01A2) to SHF is gratefully acknowledged. SHF is also supported by the Bernstein Endowed Chair in Adult Psychiatry. Tissue samples from the Stanley Medical Research Institute and assistance with demographic information from Dr Edwin Fuller-Torrey and Dr Maree J Webster to SHF is gratefully acknowledged.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Somogyi P, Tamás G, Lujan R, Buhl EH. Salient features of synaptic organization in the cerebral cortex. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;26:113–135. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charych EI, Liu F, Moss SJ, Brandon NJ. GABAA receptors and their associated proteins: Implications in the etiology and treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:481–495. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Burgos G, Fish KN, Lewis DA. GABA neuron alterations, cortical circuit dysfunction and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Neural Plast. 2011;2011:723184. doi: 10.1155/2011/723184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher B, Shen Q, Sahir N. The GABAergic deficit hypothesis of major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:383–406. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möhler H. The GABA system in anxiety and depression and its therapeutic potential. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Stary JM, Earle JA, Araghi-Niknam M, Eagan E. GABAergic dysfunction in schizophrenia and mood disorders as reflected by decreased levels of glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 kDa and Reelin proteins in cerebellum. Schizophr Res. 2005;72:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impagnatiello F, Guidotti AR, Pesold C, Dwivedi Y, Caruncho H, Pisu MG, et al. A decrease of Reelin expression as a putative vulnerability factor in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S, Bernstein HG, Fendrich R, Stauch R, Ketzler B, Dobrowolny H, et al. Increased density of GAD65/67 immunoreactive neurons in the posterior subiculum and parahippocamal gyrus in treated patients with chronic schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12:57–65. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2010.539270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakak Y, Walker JR, Li C, Wong WH, Davis KL, Buxbaum JD, et al. Genome-wide expression analysis reveals dysregulation of myelination-related genes in chronic schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4746–4751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081071198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirnics K, Middleton FA, Marquez A, Lewis DA, Levitt P. Molecular characterization of schizophrenia viewed by microarray analysis of gene expression in prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2000;28:53–67. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vawter MP, Crook JM, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR, Becker KG, et al. Microarray analysis of gene expression in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Schizophr Res. 2002;58:11–20. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo WS, Harano M, Gawlik M, Yu Z, Chen J, Pun FW, et al. GABRB2 association with schizophrenia: commonalities and differences between ethnic groups and clinical subtypes. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:653–660. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou G, Dikeos D, Daskalopoulou E, Karadima G, Avramopoulos D, Contis C, et al. Association between GABA-A receptor alpha 5 subunit gene locus and schizophrenia of a later age of onset. Neuropsychobiology. 2001;43:141–144. doi: 10.1159/000054882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petryshen TL, Middleton FA, Tahl AR, Rockwell GN, Purcell S, Aldinger KA, et al. Genetic investigation of chromosome 5q GABAA receptor subunit genes in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:1057. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldaçara L, Borgio JG, Lacerda AL, Jackowski AP. Cerebellum and psychiatric disorders. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;30:281–289. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462008000300016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konarski JZ, McIntyre RS, Grupp LA, Kennedy SH. Is the cerebellum relevant in the circuitry of neuropsychiatric disorders. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004;30:178–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception II: implications for major psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:515–528. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Wiser AK, Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, et al. Neural basis of novel and well-learned recognition memory in schizophrenia: a positron emission tomography study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;12:219–231. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200104)12:4<219::AID-HBM1017>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Barbadillo L, Pelayo-Terán JM, Rodríguez-Sánchez JM. Neuropsychological functioning and brain structure in schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:325–336. doi: 10.1080/09540260701486647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger S, Seminowicz D, Goldapple K, Kennedy SH, Mayberg HS. State and trait influences on mood regulation in bipolar disorder: blood flow differences with an acute mood challenge. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1274–1283. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotti M, Mayberg HS, McGinnis S, Brannan SL, Jerabek P. Unmasking disease-specific cerebral blood flow abnormalities: mood challenge in patients with remitted unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1830–1840. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber RT, Gruber SA, Cohen BM, Renshaw PF, Sherwood AR, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Cerebellar blood volume in bipolar patients correlates with medication. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:370–376. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KA, Ploghaus A, Cowen PJ, McCleery JM, Goodwin GM, Smith S, et al. Cerebellar responses during anticipation of noxious stimuli in subjects recovered from depression. Functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:411–415. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.5.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeganeh-Doost P, Gruber O, Falkai P, Schmitt A. The role of the cerebellum in schizophrenia: from cognition to molecular pathways. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:71–77. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011001300009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Cizadlo T, Arndt S, Rezai K, Ponto LL, et al. Schizophrenia and cognitive dysmetria: a positron-emission tomography study of dysfunctional prefrontal-thalamic-cerebellar circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9985–9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Fan G, Xu K, Wang F. Changes in cerebellar functional connectivity and anatomical connectivity in schizophrenia: A combined resting-state functional MRI and diffusion tensor imaging study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:1430–1438. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann JD, Pandya DN. Disconnection syndromes of basal ganglia, thalamus, and cerebrocerebellar systems. Cortex. 2008;44:1037–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock WM, Cardon K, Bustillo J, Roberts RC, Perrone-Bizzozero NI. Altered expression of genes involved in GABAergic transmission and neuromodulation of granule cell activity in the cerebellum of schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1594–1603. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Folsom TD, Thuras PD. Deficits in GABA(B) receptor system in schizophrenia and mood disorders: a postmortem study. Schizophr Res. 2011b;128:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneyto M, Abbott A, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Lamina-specific alterations in cortical GABAA receptor subunit expression in schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:999–1011. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Arion D, Unger T, Maldonado-Avilés JG, Morris HM, Volk DW, et al. Alterations in GABA-related transcriptome in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:147–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Avilés JG, Curley AA, Hashimoto T, Morrow AL, Ramsey AJ, O'Donnell P, et al. Altered markers of tonic inhibition in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:450–459. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08101484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuma T, Augood SJ, Arai H, McKenna PJ, Emson PC. Measurement of GABAergic parameters in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia: focus on GABA content, GABA(A) receptor alpha-1 subunit messenger RNA and human GABA transporter-1 (HGAT-1) messenger RNA expression. Neuroscience. 1999;93:441–448. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Thuras PD. GABA(A) receptor downregulation in brains of subjects with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009a;39:233–230. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0646-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Folsom TD, Reutiman TJ, Thuras PD. Expression of GABA(B) receptors is altered in brains of subjects with autism. Cerebellum. 2009b;8:64–69. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0075-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Kneeland RE, Liesch SB, Folsom TD. Fragile X mental retardation protein levels are decreased in major psychiatric disorders. Schizophr Res. 2010a;124:246–247. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Rooney RJ, Patel DH, Thuras PD. mRNA and protein levels for GABAAalpha4, alpha5, beta1, and GABABR1 receptors are altered in brains of subjects with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010b;40:743–750. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0924-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, King DP, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Laurence JA, Lee S, et al. PDE4B polymorphisms and decreased PDE4B expression are associated with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley ST, Foley PF, Innes DJ, Loh el-W, Shen Y, Williams SM, et al. GABA(A) receptor beta isoform protein expression in human alcoholic brain: interaction with genotype. Neurochem Int. 2006;49:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau M, Olsen RW. Multiple distinct subunits of the gamma-aminobutyric acid-A receptor protein show different ligand-binding affinities. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;37:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SU, Heo S, Lubec G. Mass spectrometric analysis of GABAA receptor subtypes and phosphorylations from mouse hippocampus. Proteomics. 2011;11:2171–2181. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarto I, Wabnegger L, Dögl E, Sieghart W. Homologous sites of GABA(A) receptor alpha(1), beta(3) and gamma(2) subunits are important for assembly. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:482–491. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaco RC, Hogart A, LaSalle JM. Epigenetic overlap in autism-spectrum neurodevelopmental disorders: MECP2 deficiency causes reduced expression of UBE3A and GABRB3. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:483–492. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie DJ, Seeburg PH, Wisden W. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. II. Olfactory bulb and cerebellum. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1063–1076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01063.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W, Laurie DJ, Monyer H, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. I. Telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1040–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01040.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W. Structure and distribution of multiple GABAA receptor subunits with special reference to the cerebellum. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;757:506–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb17510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Pierri JN, Fritschy JM, Auh S, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Reciprocal alterations in pre- and postsynaptic inhibitory markers at chandelier cell inputs to pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:1063–1070. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.10.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA. Pharmacological enhancement of cognition in individuals with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:397–398. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen EA, Liu J, Kiehl KA, Gelernter J, Pearlson GD, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, et al. Components of cross-frequency modulation in health and disease. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:59. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castner SA, Arriza JL, Roberts JC, Mrzljak L, Christian EP, Williams GV. Reversal of ketamine-induced working memory impairments by the GABAAalpha2/3 agonist TPA023. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:998–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Cho RY, Carter CS, Eklund K, Forster S, Kelly MA, et al. Subunit-selective modulation of GABA type A receptor neurotransmission and cognition in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1585–1593. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RW, Keefe RS, Lieberman JA, Barch DM, Csernansky JG, Goff DC, et al. A randomized clinical trial of MK-0777 for the treatment of cognitive impairments in people with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckle VJ, Fujita N, Bateson AN, Darlison MG, Barnard EA. Localization of human GABA-A receptor subunit genes to chromosomes 4 and 5. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1989;51:972. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr C, Sander T, Tadic A, Lenzen KP, Anghelescu I, Klawe C, et al. Confirmation of association of the GABRA2 gene with alcohol dependence by subtype-specific analysis. Psychiatr Genet. 2006;16:9–17. doi: 10.1097/01.ypg.0000185027.89816.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyka M, Preuss UW, Hesselbrock V, Zill P, Koller G, Bondy B. GABA-A2 receptor subunit gene (GABRA2) polymorphisms and risk of alcohol dependence. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T, Bierut LJ, Dunne G, Hinrichs AL, et al. Association with GABRA2 with drug dependence in the collaborative study of the genetics of alcoholism sample. Behav Genet. 2006;36:640–650. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA, Hodgkinson CA, Yuan Q, Shen PH, Goldman D, Roy A. The influence of GABRA2, childhood trauma, and their interaction on alcohol, heroin, and cocaine dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philibert RA, Gunter TD, Beach SR, Brody GH, Hollenbeck N, Andersen A, et al. Role of GABRA2 on risk for alcohol, nicotine, and cannabis dependence in the Iowa Adoption Studies. Psychiatr Genet. 2009;19:91–98. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3283208026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollenweider I, Smith KS, Keist R, Rudolph U. Antidepressant-like properties of α2-containing GABA(A) receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2011;217:77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpi ER, Gründer G, Lüddens H. Drug interactions at GABA(A) receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;67:113–159. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moragues N, Ciofi P, Tramu G, Garret M. Localisation of GABA(A) receptor epsilon-subunit in cholinergic and aminergic neurones and evidence for co-distribution with the theta-subunit in rat brain. Neuroscience. 2002;111:657–669. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moragues N, Ciofi P, Lafon P, Odessa MF, Tramu G, Garret M. cDNA cloning and expression of a gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor epsilon-subunit in rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4318–4330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasparov S, Davies KA, Patel UA, Boscan P, Garret M, Paton JF. GABA(A) receptor epsilon-subunit may confer benzodiazepine insensitivity to the caudal aspect of the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat. J Physiol. 2001;536:785–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belujon P, Baufreton J, Grandoso L, Boué-Grabot E, Batten TF, Ugedo L, et al. Inhibitory transmission in locus coeruleus neurons expressing GABAA receptor epsilon subunit has a number of unique properties. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:2312–2325. doi: 10.1152/jn.00227.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SA, Bonnert TP, Cagetti E, Whiting PJ, Wafford KA. Overexpression of the GABA(A) receptor epsilon subunit results in insensitivity to anaesthetics. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:662–668. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbarian S, Huntsman MM, Kim JJ, Tafazzoli A, Potkin SG, Bunney WE, Jr, et al. GABAA receptor subunit gene in human prefrontal cortex: comparison of schizophrenics and controls. Cereb Cortex. 1995;5:550–560. doi: 10.1093/cercor/5.6.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock N, Jones L, Jones IR, Kirov G, Green EK, Grozeva D, et al. Strong genetic evidence for a selective influence of GABAA receptors on a component of the bipolar disorder phenotype. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:146–153. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon H, Sobell J, Heston L, Sommer S, Hoff M, Holik J, et al. Search for mutations in the beta 1 GABAA receptor subunit gene in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet. 1994;54:12–20. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320540105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon H, Hicks AA, Bailey ME, Hoff M, Holik J, Harvey RJ, et al. Analysis of GABAA subunit genes in multiplex pedigrees with manic depression. Psychiatr Genet. 1994;4:185–191. doi: 10.1097/00041444-199400430-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamshere ML, Green EK, Jones IR, Jones L, Moskvina V, Kirov G, et al. Genetic utility of broadly defined bipolar schizoaffective disorder as a diagnostic concept. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:23–29. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.061424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertes DA, Kalsi G, Prescott CA, Kuo PH, Patterson DG, Walsh D, et al. Neurotransmitter and neuromodulator genes associated with a history of depressive symptoms in individuals with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:496–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsian A, Zhang ZH. Human chromosomes 11p15 and 4p12 and alcohol dependence: possible association with GABRB1 gene. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88:533–538. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19991015)88:5<533::aid-ajmg18>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reck BH, Mukhopadhyay N, Tsai HJ, Weeks DE. Analysis of alcohol dependence phenotype in the COGA families using covariates to detect linkage. BMC Genet. 2005;6:S143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-S1-S143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks AA, Bailey ME, Riley BP, Kamphuis W, Siciliano MJ, Johnson KJ, et al. Further evidence for clustering of human GABAA receptor subunit genes: localization of the alpha 6-subunit gene (GABRA6) to distal chromosome 5q by linkage analysis. Genomics. 1994;20:285–288. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W, Korpi ER, Bahn S. The cerebellum: a model system for studying GABAA receptor diversity. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1139–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Watanabe A, Iwayama-Shigeno Y, Yoshikawa T. Evidence of association between gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor genes located on 5q34 and female patients with mood disorders. Neurosci Lett. 349:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu M, Zhang Z, Xu Z, Shi Y, Geng L, Yuan Y, et al. Influence of genetic polymorphisms in the glutamatergic and GABAergic systems and their interactions with environmental stressors on antidepressant response. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:277–288. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Iwata N, Suzuki T, Kitajima T, Yamanouchi Y, Kinoshita Y, et al. Association analysis of chromosome 5 GABAA receptor cluster in Japanese schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Wu CN, Xu J, Feng G, Xing QH, Fu W, et al. Polymorphisms in microRNA target sites influence susceptibility to schizophrenia by altering the binding of miRNAs to their targets. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;S0924-977X:00327–00336. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan CE, Webster MJ, Rothmond DA, Bahn S, Elashoff M, Shannon Weickert C. Prefrontal GABA(A) receptor alpha-subunit expression in normal postnatal human development and schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glausier JR, Lewis DA. Selective pyramidal cell reduction of GABA(A) receptor α1 subunit messenger RNA expression in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2103–2110. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serretti A, Macciardi F, Cusin C, Lattuada E, Lilli R, Di Bella D, et al. GABAA alpha-1 subunit gene not associated with depressive symptomatology in mood disorders. Psychiatr Genet. 1998;8:251–254. doi: 10.1097/00041444-199808040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi Y, Nakayama J, Ishiguro H, Ohtsuki T, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Toyota T, et al. Possible association between a haplotype of the GABA-A receptor alpha-1 subunit gene (GABRA1) and mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:40–45. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger V, Knoll JH, Woolf E, Glatt K, Tyndale RF, DeLorey TM, et al. The gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor gamma 3 subunit gene (GABRG3) is tightly linked to the alpha 5 subunit gene (GABRA5) on human chromosome 15q11-q13 and is transcribed in the same orientation. Genomics. 1995;26:258–264. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Navarro P, Vaquero-Lorenzo C, Blasco-Fontecilla H, Díaz-Hernández M, Gratacòs M, Estivill X, et al. Genetic epistasis in female suicide attempts. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;38:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Edenberg HJ, Xuei X, Goate A, Kuperman S, Schuckit M, et al. Association of GABRG3 with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:4–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000108645.54345.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russek SJ, Farb DH. Mapping of the beta 2 subunit gene (GABRB2) to microdissected human chromosome 5q34-q35 defines a gene cluster for the most abundant GABAA receptor isoform. Genomics. 1994;23:528–533. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Xu Z, Wang F, Chen J, Ng SK, Wong PW, et al. Alternative-splicing in the exon-10 region of the GABA(A) receptor beta(2) subunit gene: relationships between novel isoforms and psychotic disorders. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Tsang SY, Zhao CY, Pun FW, Yu Z, Mei L, et al. GABRB2 in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: disease association, gene expression, and clinical correlations. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:1415–1418. doi: 10.1042/BST0371415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SK, Lo WS, Pun FW, Zhao C, Yu Z, Chen J, et al. A recombination hotspot in schizophrenia-associated region of GABRB2. PLos One. 2010;5:e9547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen SE, Fanous AH, Walsh D, O‘Neill FA, Kendler KS. Polymorphisms in SLC6A4, PAH, GABRB3, and MAOB and modification of psychotic disorder features. Schizophr Res. 2009;109:94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Jayathilake K, Zhao Z, Meltzer HY. Investigating association of four gene regions (GABRB3, MAOB, PAH, and SLC6A4) with five symptoms in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198:202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Folsom TD, Kneeland RE, Liesch SB. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 upregulation in children with autism is associated with underexpression of both Fragile X mental retardation protein and GABAA receptor beta 3 in adults with autism. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2011;294:1635–1645. doi: 10.1002/ar.21299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heulens I, D'Hulst C, Braat S, Rooms L, Kooy RF. Involvement and therapeutic potential of the GABAergic system in the fragile X syndrome. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:2198–2206. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A. Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereospecifically and selectively increase brain neurosteroid content at doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:362–372. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A. SSRIs act as selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs) at low doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler LE, Olincy A, Cawthra EM, McRae KA, Harris JG, Nagamoto HT, et al. Varied effects of atypical neuroleptics on P50 auditory gating in schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1822–1828. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolato M, Frau R, Aru GN, Orrù M, Gessa GL. Baclofen reverses the reduction in prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response induced by dizocilpine, but not by apomorphine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;171:322–330. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolato M, Frau R, Orrù M, Piras AP, Fà M, Tuveri A, et al. Activation of GABA(B) receptors reverses spontaneous gating deficits in juvenile DBA/2J mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;194:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0845-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis ZJ, George TP. Clozapine, GABA(B), and the treatment of resistant schizophrenia. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86:442–446. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx CE, VanDoren MJ, Duncan GE, Lieberman JA, Morrow AL. Olanzapine and clozapine increase the GABAergic neuroactive steroid allopregnanolone in rodents. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbra S, Mòdol L, Pallarès M. Allopregnanolone infused into the dorsal (CA1) hippocampus increases prepulse inhibition of startle response in Wistar rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:581–584. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx CE, Keefe RS, Buchanan RW, Hamer RM, Kilts JD, Bradford DW, et al. Proof-of-concept trial with the neurosteroid pregnenolone targeting cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1885–1903. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzunova V, Sheline Y, Davis JM, Rasmusson A, Uzunov DP, Costa E, et al. Increase in the cerebrospinal fluid content of neurosteroids in patients with unipolar major depression who are receiving fluoxetine or fluvoxamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3239–3244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.