Abstract

A threatening and dangerous neighborhood may produce distressing emotions of anxiety, anger, and depression among the individuals who live there because residents find these neighborhoods subjectively alienating. The author introduces the idea that neighborhood disorder indicates collective threat, which is alienating—shaping perceptions of powerlessness and mistrust. The author presents a theory of trust that posits that mistrust develops in places where resources are scarce and threat is common and among individuals with few resources and who feel powerless to avoid or manage the threat. Perceived powerlessness develops with exposure to uncontrollable, negative conditions such as crime, danger, and threat in one's neighborhood. Thus, neighborhood disorder, common in disadvantaged neighborhoods, influences mistrust directly and indirectly by increasing perceptions of powerlessness among residents, which amplify disorder's effect on mistrust. The very thing needed to protect disadvantaged residents from the negative effects of their environment—a sense of personal control—is eroded by that environment in a process that the author calls structural amplification. Powerlessness and mistrust in turn are distressing, increasing levels of anxiety, anger, and depression.

Keywords: distress, neighborhoods, sense of control, trust

What are the pathways linking neighborhood context to psychological distress? Neighborhood disadvantage and disorder may produce anxiety, anger, and depression among residents (Aneshensel and Sucoff 1996; Hill, Ross, and Angel 2005; Latkin and Curry 2003; Ross 2000; Ross and Mirowsky 2009; Ross, Reynolds, and Geis 2000; Schieman and Meersman 2004; Schulz et al. 2000; Steptoe and Feldman 2001). Subjective alienation may explain why. Subjective alienation is the sense of separation from oneself and others (Fischer 1976; Mirowsky and Ross 2003; Seeman 1983). Theoretically, four types of alienation may explain why neighborhoods influence residents' mental health: perceived powerlessness versus control, mistrust versus trust, social isolation versus support, and normlessness versus normativeness. I focus here on the two types that empirically explain the association—powerlessness and mistrust (Ross and Mirowsky 2009). Of the two major pathways, I further focus on mistrust since less is known about its role as a link between social structure and psychological distress. The effect of neighborhood context on psychological distress exemplifies Pearlin's seminal ideas that the origins of distress are in the social world. Socially structured, persistent, durable everyday life experiences shaped by social stratification, inequality, and disadvantage influence psychological distress (Pearlin 1989; Pearlin et al. 1981).

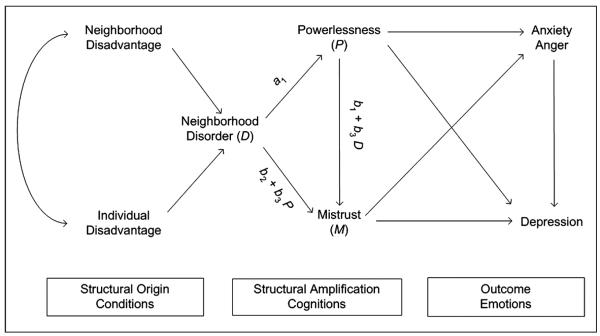

A threatening and dangerous neighborhood may produce anxiety, anger, and depression among the individuals who live there because residents find these neighborhoods subjectively alienating (Ross and Mirowsky 2009). I will introduce the idea that neighborhood disorder indicates collective threat, which is alienating—increasing the sense of powerlessness and mistrust. Powerlessness and mistrust in turn are distressing, increasing levels of anxiety, anger, and depression. Theoretically, subjective alienation forms the bridge in a three-part model of conditions, cognitions, and emotions (Mirowsky and Ross 2003; Ross and Sastry 1999; Seeman 1959, 1983). It is the cognitive bridge between reality and distress. It is the subjective reflection of social conditions of powerlessness, the inability to achieve goals, and the absence of supportive, trusting relationships. These cognitions come from reality. Beliefs about powerlessness and mistrust represent realistic perceptions of social conditions (Mirowsky and Ross 2003).

TRUST AND MISTRUST

Our theory proposes that mistrust develops among individuals with few resources who live in places where resources are scarce and threat is common and who feel powerless to avoid or manage the threat (Ross, Mirowsky, and Pribesh 2001). Neighborhood disadvantage and individual disadvantage describe places and people with few economic and social resources. Neighborhood disorder describes places with high levels of threat. Perceived control versus powerlessness indicates individuals' perceived ability to recognize, prevent, and manage potential harm in threatening environments.

We propose that mistrust emerges in disadvantaged neighborhoods with high levels of disorder among individuals with few resources, who feel powerless to avoid harm. Mistrust is the product of an interaction between person and place, but the place gathers those who are susceptible and intensifies their susceptibility. Specifically, we propose that disadvantaged individuals generally live in disadvantaged neighborhoods where they feel awash in threatening signs of disorder. Among individuals who feel in control of their own lives, neighborhood disadvantage and disorder might produce little mistrust. However, neighborhood disorder impairs residents' ability to cope with its own ill effect by also producing a sense of powerlessness. Neighborhood disorder destroys the sense of control that would otherwise insulate residents from the consequences of disorder. Thus, the very thing needed to protect disadvantaged residents from the negative effects of their environment—a sense of personal control—is eroded by that environment (Ross et al. 2001).

Defining Trust and Mistrust

Like social isolation, mistrust signals social alienation, or a sense of separation from others. The socially isolated individual feels detached from networks of affection, aid, caring, and reciprocity. Mistrust goes beyond a sense of separation from others to one of suspicion of others (Kramer 1999). Mistrust is the cognitive habit of interpreting the intentions and behavior of others as unsupportive, self-seeking, and dishonest. It is an absence of faith in other people based on a belief that they are out for their own good and will exploit or victimize you in pursuit of their goals. Mistrusting individuals believe it is safer to keep their distance from others, and suspicion of other people is the central cognitive component of mistrust. Trust, the opposite of mistrust, is a belief in the integrity of other people. Trusting individuals expect that they can depend on others. They have faith and confidence in other people. Trust and mistrust express inherently social beliefs about relationships with other people. They embody learned, generalized expectations about other people's behaviors that transcend specific relationships and situations (Barber 1983; Mirowsky and Ross 2003; Rotter 1971, 1980).

Although Seeman's (1959) original theory of subjective alienation did not consider mistrust to be one of the core types, we consider mistrust a profound form of social alienation that has gone beyond a perceived separation from others to a suspicion of them (Mirowsky and Ross 2003; Ross and Mirowsky 2003). Although social psychologists originally considered mistrust as an element of authoritarianism, its importance for psychological distress may come from the deep alienation it represents. Our mistrust scale includes questions such as feeling it is not safe to trust anyone, feeling suspicious, and feeling sure everyone is against you.

Trust is important because it allows people to form positive social relationships. Coleman (1990) emphasizes trust as an element of social capital, because trusting social relationships help produce desired outcomes. Trusting individuals are themselves more trustworthy and honest and are less likely to lie and harm others so that they create and maintain environments of trustworthiness: Trusting people enter relationships with the presumption that others can be trusted until they have evidence to the contrary (Rotter 1980). Because trusting individuals can form effective associations with others, the presumption of trust can be an advantageous strategy, despite the fact that expecting people to be trustworthy is risky. People who trust others form personalties and participate in voluntary associations more often than do mistrusting individuals (Brehm and Rahn 1997; Paxton 1999).

However, apart from ours, there is not much research as to whether mistrust is distressing and whether it forms a link between social structural conditions and distress.

THE STRUCTURAL AMPLIFICATION THEORY OF MISTRUST

Scarce Resources, Threat, and Powerlessness

Mistrust and trust imply judgments about the likely risks and benefits posed by interaction. How do people make decisions about interaction when it is uncertain whether other people can be trusted? Our theory specifies that three things should influence the level of trust: scarce resources, threat, and powerlessness. Where the environment seems threatening, among those who feel powerless to avoid or manage the threats, and among those with few resources with which to absorb losses, suspicion and mistrust seem well-founded. Mistrust makes sense where threats abound, particularly for those who feel powerless to prevent harm or cope with the consequences of being victimized or exploited. Furthermore, for people with few resources, the consequences of losing what little one has will be devastating (Mirowsky and Ross 1983; Ross et al. 2001, 2002).

Disorder and Mistrust

Through daily exposure to a threatening environment, where signs of disorder are common, residents may come to learn that other people cannot be trusted. Order is a state of peace, safety, and observance of the law; social control is an act of maintaining this order. On the other end of the continuum, neighborhoods with high levels of disorder present residents with observable signs and cues that social control is weak (Skogan 1990). In these neighborhoods, residents report noise, litter, crime, vandalism, graffiti, people hanging out on the streets, public drinking, run-down and abandoned buildings, drug use, danger, trouble with neighbors, and other incivilities associated with a breakdown of social control (Geis and Ross 1998; Lewis and Salem 1986; Ross 2000; Ross and Mirowsky 1999; Skogan 1990). Even if residents are not directly victimized, these signs indicate a potential for harm. Moreover, they indicate that the people who live around them are not concerned with public order, that residents are not respectful of one another and of each other's property, that the local agents of social control are either unable or unwilling to cope with local problems, and that those in power have probably abandoned them. Here, residents may view those around them with suspicion, as enemies who will harm them rather than as allies who will help them (Ross and Mirowsky 1999, 2001).

Neighborhood disorder indicates the potential for harm. The signs of disorder in one's neighborhood signify collective threat even if this threat is not realized in the personal victimization of any one individual. Individuals in dangerous neighborhoods live every day with the threat of victimization, through which they come to interpret the world and their place in it. Individuals in dangerous neighborhoods are victimized relatively more often than those in safe neighborhoods, yet absolute risk of victimization is low. Individuals in dangerous neighborhoods are not victimized every day—or even very often. We argue that it is the collective threat that shapes cognitive world views of personal powerlessness and mistrust that in turn produces distress. Nonetheless, the reality of actual victimization is probably at least as distressing as subjective alienation, so it is important to take personal victimization into account. Neighborhood disorder increases the risk of victimization, measured as reports of assault, burglary, and robbery, which is distressing, but victimization probably does not account for the association between neighborhood disorder and distress (Ross et al. 2002; Ross and Mirowsky 2009). Collective threat is alienating and distressing even though few people get personally victimized.

Disorder, Powerlessness, and the Structural Amplification of Mistrust

Neighborhood disorder may also reinforce a sense of powerlessness that makes the effect of disorder on mistrust even worse. Perceived powerlessness is the sense that one's own life is shaped by forces outside one's control. Its opposite, the sense of personal control, is the belief that you can and do master, control, and shape your own life. Exposure to uncontrollable, negative events and conditions in the neighborhood in the form of crime, noise, vandalism, graffiti, garbage, fights, and danger promotes and reinforces perceptions of powerlessness (Geis and Ross 1998; Mirowsky and Ross 2003; Ross and Mirowsky 2003). In neighborhoods where social order has broken down, residents often feel powerless to achieve a goal most people desire—to live in a clean, safe environment free from threat, harassment, and danger. Our scale of personal powerlessness versus control balances statements claiming or denying control over good or bad outcomes, like “I can do just about anything I really set my mind to,” on the one hand, or “There is no sense planning a lot—if something good is going to happen it will,” on the other (Mirowsky and Ross 1991, 2003).

The sense of powerlessness reinforced by a threatening environment may amplify the effect of that threat on mistrust, whereas a sense of control would moderate it. At heart, individuals who feel powerless feel awash in a sea of events generated by chance or by powerful others. They feel helpless to avoid undesirable events and outcomes, as well as powerless to bring about desirable ones. Individuals who feel powerless may feel unable to fend off attempts at exploitation, unable to distinguish dangerous persons and situations from benign ones, and unable to recover from mistaken complacency. In contrast, those with a sense of personal control may feel that they can avoid victimization and harm and effectively cope with any consequences of errors in judgment. Neighborhood disorder signals the potential for harm. Some people feel they can avoid harm, or cope with it. Neighborhood disorder might generate little mistrust among individuals who feel in control of their own lives but a great deal among those who feel powerless (Ross et al. 2001).

The Origins of Disorder and Powerlessness in Neighborhood and Individual Disadvantage

The origins of neighborhood disorder are in disadvantaged neighborhoods with high levels of poverty and mother-only households and low levels of college-educated adults and home ownership. Disadvantaged neighborhoods lack economic and social resources that create the conditions under which public order is likely to break down.

Disadvantaged individuals (who often live in disadvantaged neighborhoods) may also lack the personal and household resources that encourage trust. Individuals with low incomes, little education, the unemployed, minorities, young people, or single parents may be less trusting than those with more resources. When individuals have few resources, the dire consequences of mistaken trust make them wary. Those with few resources cannot afford to lose much and need to be vigilant in defense of what little they have.

Disadvantaged individuals lack social and economic resources needed to achieve desired ends, which may also produce a sense of powerlessness. The sense of powerlessness is the learned and generalized expectation that one has little control over meaningful events and circumstances in one's life. As such, it is the cognitive awareness of a discrepancy between one's goals and the resources needed to achieve them (Mirowsky and Ross 2003).

Therefore, individual disadvantage may undermine trust directly and indirectly by way of two paths: Disadvantaged individuals live in disadvantaged neighborhoods where residents report a lot of disorder, and disadvantaged individuals may feel powerless to control their lives, thereby amplifying the mistrust associated with threatening conditions in the neighborhood. Disadvantage sets in motion a process that magnifies mistrust among those with few resources, in an instance of what we call structural amplification (Ross et al. 2001).

Formal Model of Structural Amplification

Structural amplification exists when conditions undermine the personal attributes that otherwise would moderate their undesirable consequences. The situation erodes resistance to its own ill effect. More generally, it exists when a mediator of the association between an objective condition and a subjective belief or feeling also amplifies the association. The mediator of an undesirable effect is also a moderator of that effect.

Mediators link objective social conditions to subjective beliefs and feelings. Mediators are a consequence of an independent variable and a “cause” of a dependent variable. Moderators, or modifiers, modify associations between objective conditions and subjective beliefs or feelings, making the associations between independent and dependent variables stronger or weaker, conditional on their level (Baron and Kenny 1986; Mirowsky 1999). Moderators can be specified by interaction terms (Aiken and West 1991). Moderators sometimes buffer stressful effects, lessening the ill effects of disadvantaged or threatening conditions (Wheaton 1985), but in structural amplification, moderators amplify ill effects, making them worse. Most importantly, in structural amplification, moderators are also linked to social conditions. Here a sense of powerlessness amplifies the association between neighborhood disorder and mistrust, but the perception of powerlessness does not just come out of people's heads without reference to social conditions. A sense of powerlessness is also a consequence of neighborhood disorder. When moderators of the association between a social condition and mistrust result from the condition itself, this produces structural amplification (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model of Structural Amplification

EVIDENCE ON THE PSYCHOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF NEIGHBORHOOD DISORDER

I examined these ideas with my survey of Community, Crime, and Health (CCH), a probability sample of Illinois households with linked census tract information about each respondent's neighborhood, collected in 1995 with a follow-up in 1998 (Ross et al. 2001; Ross and Mirowsky 2009). All models adjust for individual socioeconomic disadvantage, including age, sex, race, marital status, children in the household, employment status, education, income, economic hardship, and urban residence, whenever we examine the influence on neighborhoods on cognitions and emotions. Neighborhood disorder is assessed by the Ross-Mirowsky neighborhood disorder scale, which measures physical and social signs of disorder and order (shown in the appendix). In support of our theory, neighborhood disorder increases mistrust. Moreover, neighborhood disorder produces more mistrust among those who feel powerless to control their lives than among those with a sense of personal control—that is, there is a significant interaction between disorder and powerlessness in the prediction of mistrust. In fact, neighborhood disorder has little effect on mistrust among individuals with a strong sense of personal control. Neighborhood disorder is also associated with the perception that one is powerless to control one's life, and this perception in turn worsens the detrimental effects of neighborhood disorder on trust. Thus, neighborhood disorder increases mistrust directly and indirectly by generating the powerlessness that amplifies disorder's effect on mistrust. Neighborhood disadvantage increases mistrust entirely by way of neighborhood disorder.

Individual disadvantage also influences mistrust. Older people, whites, those with high household incomes, and the well-educated are more trusting than younger persons, nonwhites, those with low incomes, and those with less education. In terms of family status, single parents have the highest levels of mistrust, followed by single people without children, married parents, and married persons without children. In general, individual socioeconomic disadvantage correlates with mistrust, with one exception. Men hold advantaged statuses compared to women, but men are significantly more mistrusting than women.

Individual disadvantage is also associated with perceived powerlessness. People with low incomes, low levels of education, nonwhites, and those who are not married report more personal powerlessness than do people with high incomes, education, whites, and people who are married.

The powerlessness and mistrust that are generated by neighborhood disorder in turn increase psychological distress as measured by depression, anxiety, and anger. Perceived powerlessness is demoralizing and enervating. If one cannot influence conditions and events in one's own life, what hope is there for the future? Powerlessness undermines confidence and reinforces helplessness. In addition to its direct, demoralizing effect, the sense of not being in control of the outcomes in one's life diminishes the will and motivation to solve problems or avoid them. This produces depression. We find that perceived powerlessness correlates more strongly with the passive emotion of depression than with the active and agitated emotions of anxiety and anger, which may result from the attentive and active problem solving associated with a greater sense of control.

Little is known about mistrust and distress. We find, surprisingly, that mistrust's influence on distress is actually somewhat larger than that of powerlessness, and it forms a larger link between neighborhood disorder and distress. Unlike perceived powerlessness, mistrust's association with anxiety and anger is larger than its association with depression

Although not originally conceptualized as subjective alienation, mistrust fits the definition—any form of detachment or separation from oneself or from others. Mistrusting individuals are not simply isolated from other people, they are deeply suspicious of others. Because they think other people are likely to harm them, they feel they cannot depend on others, turn to others when they need help, confide in others, or rely on them. To mistrusting individuals, any social interaction carries risk. This makes mistrust an extremely distressing form of alienation. Suspicion of others reflects a heightened sense of threat, which produces anxiety; and the sense that other people are more likely to harm you than to help you is demoralizing. Mistrust increases both anxiety and depression. As social animals, all humans must live and work around others. Mistrust creates a dilemma. Engaging with others generates anxiety because those others pose threats. Disengaging from others generates depression because of isolation. The dilemma itself also generates depression because of the inescapable punishment one way or the other.

Mistrust may rival powerlessness as a major link between structural disadvantage and distress, especially on the collective or contextual level. In Social Causes of Psychological Distress (Mirowsky and Ross 2003), we concluded that a low sense of control over one's own life creates the primary link between psychological distress and individual disadvantaged social statuses such as low education, low income, economic hardship, unemployment, unstable employment, and poorly paid, tedious, routine, and oppressive jobs. Although perceived powerlessness links individual socioeconomic disadvantage to distress, it is possible that mistrust creates a major link between psychological distress and collective disadvantage. Perceived powerlessness is the cognitive awareness of an inability to achieve individual goals. It is a separation from self—from important outcomes in one's own life. Mistrust represents social alienation—a separation from others. Perhaps neighborhood context is linked to distress by way of social alienation as much or more than alienation from oneself. Social cues of disorder like people hanging out on the streets, drinking or taking drugs, and heightening the sense of danger are cues about other people in one's neighborhood. Even the physical cues of neighborhood disorder like graffiti, vandalism, run-down buildings, and trash on the streets are really cues about the activities of people in one's neighborhood, because people broke the windows or spray-painted the graffiti. The collective threat implied by disorder is created by other people and may lead to the social alienation of mistrust as much or more than to the personal alienation of powerlessness. While this idea is appealing theoretically, and has some support since mistrust forms the largest link between neighborhood disorder and distress, it also implies a larger link between neighborhood disorder and mistrust than between neighborhood disorder and powerlessness. In fact, their standardized effects are about the same. Finally, it is important to remember that disadvantage on the personal and household levels (e.g., low levels of personal education, unemployment, employment at oppressive and routine jobs, and low household income or a great deal of economic hardship in the household) has much larger effects on psychological distress than does the neighborhood in which one lives.

Social Isolation

Thus far I have emphasized the pathways that empirically link neighborhoods to distress—powerlessness and mistrust—and ignored social isolation. This is because empirically, social isolation does not form a pathway between neighborhood disorder and distress. Social isolation does not result from neighborhood disorder, nor does it increase anxiety or anger (although it does increase depression) (Ross and Mirowsky 2009).

Supportive social ties have benefits and costs for psychological well-being. Social support is the individual's perception of having others who care and will help if needed. Social isolation is its opposite. Our measure of social support versus isolation includes emotional and practical support, with questions like: “I have someone I can turn to for support and understanding when things get rough,” “I have someone I can really talk to,” and “I have someone who would help me out with things, like give me a ride, watch the kids or house, or fix something.” Social support grows out of networks of reciprocity. Reciprocal social ties imply mutual obligations that reassure the individuals and thereby help reduce depression, but the reciprocity implies obligations as well as benefits (Schieman 2005). We find trade-offs to social support at every stage of the process. The trade-offs for distress may be highlighted because we adjust for the sense of control and trust, which have positive correlations with support. Consistent with other research, we find that people who are socially isolated have higher levels of depression than those with high levels of support. However, perhaps one of the most surprising findings is that people who are socially isolated—who are not integrated into networks of support, communication, mutual obligations, advice, and caring—have lower levels of anger and anxiety than do people with high levels of social support. This could be due in part to the fact that anger is a social emotion. Anger is typically directed at other people, usually those in one's close network of family, friends, and colleagues (Averill 1983; Ross and Van Willigen 1997; Tavris 1982). People without these ties may simply have fewer people to be angry at. However, there may be more to it than that. For instance, Hughes and Gove (1981) found that there was no psychological advantage to living with others among the nonmarried. They speculate that social integration may involve a psychological tradeoff: “Just as persons may gain substantial satisfaction and personal gratification from family relations, they may also suffer frustration, aggravation, hostility, and anger from being constrained to conform to the obligations necessary to meet socially legitimated demands of others in the household” (Hughes and Gove 1981:71). This speculation is given credence by our results. The mutual obligations, limited freedoms, expectations from others, constraints, demands, and dependence implied by supportive relationships may increase anger and anxiety.

Another unexpected finding also relates to social isolation: Neighborhood disorder reduces perceived social isolation directly, although its indirect effect is positive. Neighborhood disorder increases social isolation by way of mistrust. Disorder increases mistrust, which increases social isolation. People with high levels of mistrust do not form supportive social ties with others. Unexpectedly though, with adjustment for these indirect effects, living in a neighborhood with a lot of disorder is directly associated with more supportive ties with others. All else being equal, disorder is associated with more social ties, but of course, all else is not really equal since disorder decreases trust, which interferes with the formation and maintenance of supportive relationships. On average, disorder decreases trust, but if it does not, trusting individuals could see social ties as a way to cope with danger, trouble, and crime in the neighborhood. It may be that necessity encourages people to create alliances with others; that social ties are a strategy used to deal with adversity. For instance, Schieman (2005) found that neighborhood disadvantage increased social support among elderly black women. Even if these initial findings prove to be incorrect as more research accumulates, it does at least point to the fact that social ties and social order do not necessarily go together.

Normlessness

The final type of subjective alienation that we looked at is normlessness. Like powerlessness, normlessness signals a gap in personal achievement: the cognitive awareness of a gap between one's goals and one's ability to achieve them. Powerlessness is a more profound sense of alienation than is normlessness because normlessness is the perceived gap between goals and legitimate, legal, approved, and normative means, whereas powerlessness is the perceived gap between goals and any available means. A person who feels powerless feels helpless to achieve goals through any means, whereas a person who feels normless thinks that socially unapproved behaviors could be effective in achieving goals (Ross and Mirowsky 1987). Normlessness is the subjective reflection of conditions of structural inconsistency, where access to effective legitimate means is limited. A normless individual believes that most people are honest only because they are afraid of being caught; that in order to get ahead, you have to take everything you can get; and that most people do not always do what is right. Neighborhood disorder is associated with normlessness. In neighborhoods where social control has broken down, people may learn that exemplary, lawful behavior is not common or useful. Despite a large effect of disorder on normlessness, normlessness in turn does not seem to be directly associated with psychological distress. Any appearance of an association appears to be due to the positive association of normlessness with mistrust (Ross and Mirowsky 2009).

Realized Threat and Collective Threat

The collective threat implied by neighborhood disorder is alienating and distressing even when this threat is not realized in personal victimization such as assault, robbery, or burglary.

The likelihood of victimization increases with neighborhood disorder, and victimization in turn is distressing, but victimization is not a major link between neighborhood disorder and distress. It explains only about 10 percent of the association between neighborhood disorder and distress.

Perceived collective threat is associated with anxiety and anger, followed by depression (Hill et al. 2005). We specified a causal sequence in which anxious arousal and anger are followed by depressed lethargy and demoralization (Ross and Mirowsky 2009). This specification fit the data well. Threat and signs of incivility on the streets initiate anger and anxiety, the alarm, arousal, and agitation feelings of “fight-or-flight.” It may be in the long run that chronic exposure to threat also takes its toll in feelings of depression—feeling run-down, demoralized, lethargic, and hopeless about the future.

In a pernicious instance of structural amplification, disadvantage sets in motion a process that magnifies mistrust among those with few resources, who feel powerless to control their own lives. Neighborhood disorder, common in disadvantaged neighborhoods, where disadvantaged individuals live, influences mistrust directly and indirectly by increasing perceptions of powerlessness among residents, which then amplify disorder's effect on mistrust. Mistrust and powerlessness in turn are associated with anxiety, anger, and depression. Powerlessness and mistrust form the major links between neighborhood disorder and distress.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This research was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging: “Reconceptualizing Socioeconomic Status and Health” to Catherine E. Ross (P.I.) R01AG035268 and a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health “Community, Crime and Health across the Life Course” to Catherine E. Ross (p.i.) R01 MH51558.

Biography

Catherine E. Ross is a professor in the Department of Sociology and the Population Research Center at the University of Texas. Her research examines the effects of socioeconomic status, gender, and neighborhoods on physical and mental health, the sense of control versus powerlessness, and health lifestyle. Recent books include Education, Social Status, and Health and the second edition of Social Causes of Psychological Distress, both coauthored with John Mirowsky in 2003. Her current work, funded by NIA, is titled “Reconceptualizing Socioeconomic Status and Health.” Recent publications include “Gender and the Health Benefits of Education,” The Sociological Quarterly (2010), and “The Interaction of Personal and Parental Education on Health,” Social Science & Medicine (2011), both with John Mirowsky.

APPENDIX

Neighborhood Disorder (Ross-Mirowsky Scale 1999)

Physical disorder and order

There is a lot of graffiti in my neighborhood.

My neighborhood is noisy.

Vandalism is common in my neighborhood.

There are a lot of abandoned buildings in my neighborhood.

My neighborhood is clean.

People in my neighborhood take good care of their houses and apartments.

Social disorder and order

There are too many people hanging around on the streets near my home.

There is a lot of crime in my neighborhood.

There is too much drug use in my neighborhood.

There is too much alcohol use in my neighborhood.

I'm always having trouble with my neighbors.

My neighborhood is safe.

All items are scored so that a high score indicates disorder. Disorder items are scored strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), agree (3), and strongly agree (4). Order items are scored in reverse.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this article was presented in receipt of the Leonard I. Pearlin Award for Distinguished Contributions to the Sociological Study of Mental Health at the American Sociological Association annual meeting in Atlanta in August of 2010.

REFERENCES

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel Carol S., Sucoff Clea A. The Neighborhood Context of Adolescent Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:293–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill JR. Studies on Anger and Aggression: Implications for Theories of Emotion. American Psychologist. 1983;38:1145–160. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.38.11.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber B. The Logic and Limits of Trust. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategical, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm John, Rahn Wendy. Individual-Level Evidence for the Causes and Consequences of Social Capital. American Journal of Political Science. 1997;41:999–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman James S. Foundations of Social Theory. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Claude S. The Urban Experience. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Geis Karlyn J., Ross Catherine E. A New Look at Urban Alienation: The Effect of Neighborhood Disorder on Perceived Powerlessness. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1998;61:232–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Terrence D., Ross Catherine E., Angel Ronald J. Neighborhood Disorder, Psychophysiological Distress, and Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:170–86. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Michael M., Gove Walter R. Living Alone, Social Integration, and Mental Health. American Journal of Sociology. 1981;87:48–74. doi: 10.1086/227419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer Roderick M. Trust and Distrust in Organizations: Emerging Perspectives, Enduring Questions. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50:569–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin Carl, Curry Aaron. Stressful Neighborhoods and Depression: A Prospective Study of the Impact of Neighborhood Disorder. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Dan A., Salem Greta. Incivility and the Production of a Social Problem. Transaction; New Brunswick, NJ: 1986. Fear of Crime. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John. Analyzing Associations between Social Circumstances and Mental Health. In: Aneshensel C, Phelan J, editors. Handbook on the Sociology of Mental Health. Kluwer/Plenum; New York: 1999. pp. 105–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. Paranoia and the Structure of Powerlessness. American Sociological Review. 1983;48:228–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. Eliminating Defense and Agreement Bias from Measures of the Sense of Control: A 2 × 2 Index. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1991;54:127–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. Social Causes of Psychological Distress. 2nd ed. Aldine Transaction; New Brunswick, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton Pamela. Is Social Capital Declining in the United States? A Multiple Indicator Assessment. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;105:88–127. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I. The Sociological Study of Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30:241–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I., Menaghan Elizabeth G., Lieberman Morton A., Mullan Joseph T. The Stress Process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E. Neighborhood Disadvantage and Adult Depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:177–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Mirowsky John. Normlessness, Powerlessness, and Trouble with the Law. Criminology. 1987;25:257–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Mirowsky John. Disorder and Decay: The Concept and Measurement of Perceived Neighborhood Disorder. Urban Affairs Review. 1999;34:412–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Mirowsky John. Neighborhood Disadvantage, Disorder, and Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:258–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Mirowsky John. Social Structure and Psychological Functioning: Distress, Perceived Control and Trust. In: DeLamater J, editor. Handbook of Social Psychology. Kluwer-Plenum; New York: 2003. pp. 411–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Mirowsky John. Neighborhood Disorder, Subjective Alienation, and Distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50:49–64. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Mirowsky John, Pribesh Shana. Powerlessness and the Amplification of Threat: Neighborhood Disadvantage, Disorder, and Mistrust. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:568–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Mirowsky John, Pribesh Shana. Disadvantage, Disorder, and Urban Mistrust. City and Community. 2002;1:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Reynolds John R., Geis Karlyn J. The Contingent Meaning of Neighborhood Stability for Residents' Psychological Well-Being. American Sociological Review. 2000;65:581–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Sastry Jaya. The Sense of Personal Control: Social Structural Causes and Emotional Consequences. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. The Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health. Plenum; New York: 1999. pp. 369–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Van Willigen Marieke. Education and the Subjective Quality of Life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:275–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter Julian B. Generalized Expectancies for Interpersonal Trust. American Psychologist. 1971;26:443–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter Julian B. Interpersonal Trust, Trustworthiness, and Gullibility. American Psychologist. 1980;35:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman Scott. Residential Stability and the Social Impact of Neighborhood Disadvantage: A Study of Gender- and Race-Contingent Effects. Social Forces. 2005;83:1031–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman Scott, Meersman Steven C. Neighborhood Problems and Health among Older Adults: Received and Donated Social Support and the Sense of Mastery as Effect Modifiers. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:s89–97. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz Amy, Williams David, Israel Barbara, Becker Adam, Parker Edith, James Sherman, Jackson James. Unfair Treatment, Neighborhood Effects, and Mental Health in the Detroit Metropolitan Area. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:314–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman Melvin. On the Meaning of Alienation. American Sociological Review. 1959;24:783–91. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman Melvin. Alienation Motifs in Contemporary Theorizing: The Hidden Continuity of Classic Themes. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1983;46:171–84. [Google Scholar]

- Skogan Wesley G. Disorder and Decline: Crime and the Spiral of Decay in American Neighborhoods. University of California Press; Berkeley and Los Angeles: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe Andrew, Feldman Pamela. Neighborhood Problems as Sources of Chronic Stress: Development of a Measure of Neighborhood Problems, and Association with Socioeconomic Status and Health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;23:177–85. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2303_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavris C. Anger: The Misunderstood Emotion. Simon & Schuster; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton Blair. Models for the Stress-Buffering Functions of Coping Resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1985;26:352–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]