Abstract

This consensus based national guideline addresses the need for psychological, psychiatric and social assessment, as well as management, in antenatal women with diabetes. It builds upon the earlier Indian guidelines on psychological management of diabetes, and should be considered as an addendum to the parent guideline.

Keywords: Depression, gestational diabetes mellitus, stress

INTRODUCTION

Obstetrics is perhaps the oldest specialty in medical science. Diabetes mellitus has been known to physicians of ancient times as well. It is only in the past half century, however, that the two specialties of ancient origins, have come together to tackle the modern epidemic of pregnancy complicated by diabetes. Though the presence of diabetes in pregnancy was first described in German literature in 1826, and in English texts in 1846, the term “gestational diabetes” was used for the first time just half a century ago.[1]

PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF DIABETES

Particularly, psychosocial aspects of diabetes management have been gaining prominence.[2,3] The Indian national guideline on psychosocial management of diabetes is one of the few national guidelines focusing on psychosocial aspects alone.[4] This broad-based guideline was formulated to provide direction to diabetes care professionals practicing in India, with an abridged form published as a book chapter.[5]

PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF DIABETES IN WOMEN

The published Indian guidelines[4,5] did not focus sufficiently on women with diabetes, which was pointed out by external reviewers from the South Asia Referee Panel. This formed the basis for the current document, considering the evidence which supports the existence of gender gradients in quality of life, well being and adjustment to diabetes.[6,7] Though these aspects of gender-specific diabetes care have been reviewed earlier,[8] this has now been addressed comprehensively by preparing a six- country consensus statement on the South Asian Woman with Diabetes.[9] Within the context of gender-related issues, another multi country Consensus Statement on the South Asian Girl Child with Diabetes is under preparation (Azad K, et al.). Led by Bangladesh, this statement focuses upon the unique needs and concerns of girl children with diabetes.

PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF DIABETES IN PREGNANCY

The psychosocial issues faced by women who are diagnosed to have diabetes in pregnancy, i.e. gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) need to be addressed. Pregnancy is a unique feature of life, in that it is a finite condition. This, and the expected arrival of a new member, encourages the family and community to display empathic and sensitive attitude and behavior toward the antenatal woman. While this is true in many cultures, it is not the case in certain (but certainly not all) South Asian ethnic groups. In a few communities which have an entrenched anti-female bias, the diagnosis of a chronic disease becomes another reason or excuse to discriminate against the woman with diabetes.

The unique psychosocial problems and challenges faced by women experiencing pregnancy have been documented by obstetricians.[10] However, no mention is made of psychosocial complaints specific to pregnant women diagnosed to have diabetes. If it is clearly documented that diabetes is associated with distress,[11] and pregnancy is in itself a stressful condition,[12] it stands to reason that a diabetic pregnancy will be linked with significant stress.

This medical concern becomes even more important, as we understand that maternal exposure to stress, in the form of grief or bereavement, leads not only to maternal ill health, but impacts the health of the unborn fetus, increasing its chances of developing both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.[13,14] Though Western work is available which highlights the existence of significant psychosocial stress, and need for better psychological care for women with pregnancy complicated by diabetes,[15,16,17,18] there is a need to sensitize Indian diabetes care providers to address this aspect of medical praxis.

To tackle this issue, it was decided to prepare a brief document on Psychosocial Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy, as an Addendum to the National Psychosocial Management Guidelines, published in 2013. This Addendum follows the publication of a similar, complementary guideline, specific to the North East region of India.[19]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The current guidelines have been prepared following the same methodology as described in the parent document.[4] Similar grading for evidence base and strength of recommendation is used.[2] Because of paucity of existing literature in this field, strength of recommendation comes from the collective clinical experience of the authors.

This paper has been written by a multidisciplinary group of authors, including endocrinologists, diabetologists obstetricians, psychiatrists, psychologists, and public health specialists. The composition of the writing group reflects the need for care from all these diverse specialties for the woman with diabetes and pregnancy working together as a team. The authors are aware that this document does not cover every aspect of GDM management. The intention certainly is not to repeat advice related to screening, diagnosis, nutritional management, obstetric care, and pharmacological management of glycemia in pregnancy. Rather, this highlights the need for psychosocial assessment, and suggests practical means of psychosocial intervention, in antenatal women with diabetes. In certain cases, the recommendations address postnatal women with diabetes, highlighting the fact that pregnancy cannot be looked at as an isolated event in a woman's life.

This recommendations listed in this addendum have been grouped as General, Psychological, Psychiatric, and Social, following the style used in the national Indian guidelines.[4] These points are in addition to the recommendations made in the parent document, and should be read as being complementary to them. Repetition has been purposely avoided. The terms “diabetes in pregnancy and “GDM” are used interchangeably at times in this paper.

GUIDELINES FOR THE PSYCHOSOCIAL MANAGEMENT OF DIABETES IN PREGNANCY

General: Provision of health care

Recommendation - 1

Team work among various members of the health care team caring for antenatal and postnatal women with diabetes must be strengthened. (Grade A; EL 4).

Recommendation - 2

If feasible, trained and qualified mental health professionals should be included as a part of the diabetes pregnancy care team. (Grade A; EL 2).

Recommendation - 3

All health care providers (HCPs) who deal with antenatal women should be aware of the unique psychosocial stresses that accompany pregnancy complicated by diabetes (Grade A; EL 4).

Psychological assessment

Recommendation - 4

All HCPs who deal with pregnancy complicated by diabetes should be trained in taking at least a brief psychosocial history (Grade A; EL 4).

Recommendation - 5

Paramedical staff such as diabetes nurses, diabetes educators and pharmacists can be utilized, after adequate training, to screen for psychosocial health (Grade A; EL 1).

Recommendation - 6

Every antenatal and postnatal woman with diabetes should be questioned about fears or anxiety related to

Her unborn child's health

Her own health

Her family/social health (Grade A; EL 1).

Psychological care

Recommendation - 7

Every antenatal and postnatal woman with diabetes should be provided psychosocial support and reassurance as a part of routine antenatal care (Grade A; EL 1).

Recommendation - 8

Adequate counseling must precede, and follow, all screening and diagnostic tests, including glucose tolerance tests, and ultrasonographic monitoring (Grade A; EL 4).

Recommendation - 9

Appropriate counseling must accompany insulin prescription. Appropriate insulin technique and site must be explained to all antenatal women with diabetes, in a trimester- specific manner (Grade A; EL 4).

Psychiatric assessment

Recommendation - 10

Each antenatal and postnatal woman with diabetes should be questioned about depression, using either generic instruments such as WHO-5 and Whooley's two questions,[20,21] or condition specific instruments such as the Edinburgh postnatal depression questionnaire and Pregnancy Experiences Scale (PES).[22,23] (Grade A; EL 1).

Psychiatric care

Recommendation - 11

If psychological or psychiatric morbidity is significant, referral to qualified mental health care professionals is indicated (Grade A; EL 2).

Recommendation - 12

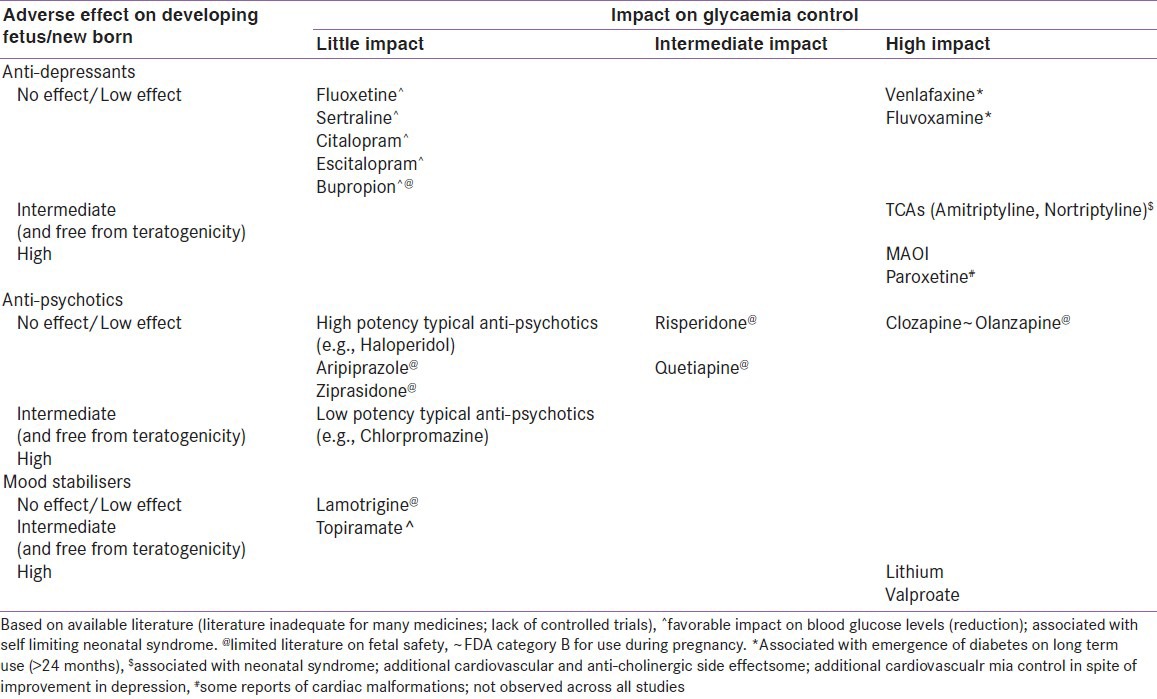

Psychoactive drugs antenatal and postnatal women with diabetes should be chosen with care [Table 1], keeping in mind their (Grade A; EL 2):

Table 1.

Grouping of various psychotropic medications based on fetal safety and impact on glycaemia control

Impact on glycemic control

Teratogenic potential

Behavioural teratogenic potential

Transplacental exposure

Excretion in breast milk.

Social assessment

Recommendation - 13

The attitudes of the family and community toward the diagnosis of diabetes in the antenatal patient should be enquired into (Grade A; EL 4).

Social care

Recommendation - 14

Family members, including husband, mother- in-law, and other significant relatives, should be involved as active partners in providing psychosocial support to the woman with diabetes.[24] (Grade A; EL 2).

Recommendation - 16

Family members should be counseled about the potential deleterious effect of maternal stress on the health of unborn offspring (Grade A; EL 4).

Recommendation - 17

HCPs caring for women with diabetes should play a proactive role in modulating social opinions and attitudes related to gender (Grade A; EL 4).

CONCLUSION

As our understanding of GDM, and its trans-generational impact grows interest in its management is bound to increase. Optimal management of any condition, especially GDM, can be attained only by paying proper attention to, and managing, all aspects of the disease, including psychosocial issues. It is hoped that this document, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the first such attempt in the world, will help us achieve this simple aim: Achieving optimal health and outcomes for all women with GDM, and their unborn offspring.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No

REFERENCES

- 1.Negrato CA, Gomes MB. Historical facts of screening and diagnosing diabetes in pregnancy. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2013:22. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 2.Handelsman Y, Mechanick JI, Blonde L, Grunberger G, Bloomgarden ZT, Bray GA, et al. American association of clinical endocrinology medical guidelines for clinical practice for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:1–53. doi: 10.4158/ep.17.s2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IDF global guidelines for type 2 diabetes. 2005. [Last accessed on 2013 May 25]. Available from: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/IDF%20GGT2D.pdf .

- 4.Kalra S, Sridhar GR, Balhara YS, Sahay RK, Bantwal G, Baruah MP, et al. National recommendations: Psychosocial management of diabetes in India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:376–95. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.111608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National recommendations: Psychosocial management of diabetes in India. [Last accessed on 2013 June 02]. Available from: http://www.apiindia.org/medicine_update_2013/chap46.pdf . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Madhu K, Veena S, Sridhar GR. Gender differences in quality of life among persons with diabetes mellitus in south India. Diabetologia. 1997;40(Suppl 1):2487–632. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sridhar RG, Madhu K, Veena S. Gender differences in well-being among persons with diabetes in India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;50(Suppl 1):S242–p981. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sridhar GR, Madhu K. Stress in the cause and course of diabetes. Int J Diab Dev Countries. 2001;21:112–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajaj S, Jawad F, Islam N, Mahtab H, Bhattarai J, Shrestha D, et al. South Asian women with diabetes: Psychosocial challenges and management: Consensus statement. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:548–62. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.113720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nast I, Bolten M, Meinlschmidt G, Hellhammer DH. How to Measure Prenatal Stress? A systematic review of psychometric instruments to assess psychosocial stress during pregnancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:313–22. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balhara YP. Diabetes and psychiatric disorders. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15:274–83. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.85579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardwell MS. Stress: Pregnancy Considerations. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2013;68:119–29. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31827f2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Olsen J, Vestergaard M, Obel C, Kristensen JK, Virk J. Prenatal exposure to bereavement and type-2 diabetes: A Danish longitudinal population based study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virk J, Li J, Vestergaard M, Obel C, Lu M, Olsen J. Early life disease programming during the preconception and prenatal period: Making the link between stressful life events and type-1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderberg E, Berntorp K, Crang-Svalenius E. Diabetes and pregnancy: Women's opinions about the care provided during the childbearing year. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23:161–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lydon K, Dunne FP, Owens L, Avalos G, Sarma KM, O’Connor C, et al. Psycho stress associated with diabetes during pregnancy: A pilot study. Irish Med J. 2012;105(Suppl 5):S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lapolla A, Di Cianni G, Di Benedetto A, Franzetti I, Napoli A, Sciacca L, et al. Quality of life, wishes, and needs in women with gestational diabetes: Italian DAWN pregnancy study. Int J Endocrinol 2012. 2012:784726. doi: 10.1155/2012/784726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ragland D, Payakachat N, Hays EB, Banken J, Dajani NK, Ott RE. Depression and diabetes: Establishing the pharmacist's role in detecting comorbidity in pregnant women. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2010;50:195–9. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalra S, Baruah MP, Ranabir S, Singh NB, Choudhury AB, Sutradhar S, et al. Guidelines for ethno-centric psychosocial management of diabetes mellitus in India: The north east consensus group statement. J Soc Health Diabetes. 2013;1:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Primack BA. The WHO-5 wellbeing index performed the best in screening for depression in primary care. ACP J Club. 2003;139:50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiPietro JA, Ghera MM, Costigan K, Hawkins M. Measuring the ups and downs of pregnancy stress. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;25:189–201. doi: 10.1080/01674820400017830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sridhar GR, Madhu K. Psychosocial and cultural issues in diabetes mellitus. Curr Sci. 2002;83:1556–64. [Google Scholar]