Abstract

A begomovirus isolate (OY136A) collected from okra plants showing upward leaf curling, vein clearing, vein thickening and yellowing symptoms from Bangalore rural district, Karnataka, India was characterized. The sequence comparisons revealed that, this virus isolate share highest nucleotide identity with isolates of Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus (CLCuBV) (AY705380) (92.8 %) and Okra enation leaf curl virus (81.1–86.2 %). This is well supported by phylogentic analysis showing, close clustering of the virus isolate with CLCuBV. With this data, based on the current taxonomic criteria for the genus Begomovirus, the present virus isolate is classified as a new strain of CLCuBV, for which CLCuBV-[India: Bangalore: okra: 2006] additional descriptor is proposed. The betasatellite (KC608158) associated with the virus is having more than 95 % sequence similarity with the cotton leaf curl betasatellites (CLCuB) available in the GenBank.The recombination analysis suggested, emergence of this new strain of okra infecting begomovirus might have been from the exchange of genetic material between BYVMV and CLCuMuV. The virus was successfully transmitted by whitefly and grafting. The host range of the virus was shown to be very narrow and limited to two species in the family Malvaceae, okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) and hollyhock (Althaea rosea), and four in the family Solanaceae.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13337-013-0141-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Okra, Whitefly, Begomovirus, PCR, Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus, Recombination

Introduction

Begomoviruses are small circular ssDNA plant viruses with distinctive twinned isometric particle morphology belong to the family Geminiviridae. This family has been classified into four genera; Begomovirus, Mastrevirus, Curtovirus and Topocuvirus based on their host range, genome arrangement, and insect vectors [19, 22, 52]. Among these, whitefly (Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius)) transmitted Begomoviruses are the major constraints for the production of many dicotyledonous plants across the globe [2, 9, 55]. These begomoviruses occur mostly in tropical to warm temperate geographical zones and infect a wide range of plant species. However, there are groups of geminiviruses (Mastrevirus) that occur in cold temperate climates.

The genome of the begomoviruses comprised of either a single component (monopartotite), or as two components (bipartite) of ssDNA [29]. DNA components of bipartite begomoviruses are referred as DNA-A and DNA-B which are having approximate size of 2.6 kb each. While, monopartite begomovirus genome contains the homologous DNA-A component of bipartite begomoviruses with approximate size of 2.6 kb. Both the components may require for the infection and symptom modulations in bipartite begomoviruses [51]. Although, there are a few truly monopartite begomoviruses such as Tomato yellow leaf curl virus[35], which has become globally widespread [30], the majority of the monopartite begomoviruses are associated with additional ssDNA molecules known as betasatellites and/or alpasatellites (DNA1) [3].

The component A encodesseveral multifunction proteins involved in rolling circle replication of the genome, gene transcription, cell-to-cell and long-distance movement, suppression of host gene silencing, and encapsidation of the viral genome. Whereas, the proteins encoded by component B are involved in movement of virus within the plant, host range and symptom expression [29, 44]. Betasatellites associated with the monopartite viruses are approximately half the size of their helper begomoviruses and required to induce typical disease symptoms in their original hosts [4, 7, 27]. These satellites depend on their helper virus for replication, movement, encapsidation and vector transmission. Alphasatellites are self-replicating circular ssDNA molecules, depend on the helper virus for movement, encapsidation and vector transmission and play no role in symptom induction [5–7, 32]. However, recently the Rep proteins encoded by some alphasatellites have been shown to have suppressor activity of RNA silencing, suggesting that alphasatellites are involved in overcoming host defenses [36]. In the Old world, both monopartite and bipartite begomoviruses has been identified [52] however, the majority among these is monopartite viruses associated with the additional ssDNA molecules [3].The begomoviruses natives to the New world are bipartite [16, 24, 39].

The spread and occurrence of the diseases caused by begomoviruses depends on the vector whitefly B. tabaci. There is a phenomenon of high proliferation and rapid dissemination of begomoviruses by whitefly with the introduction of the new B biotype by displacing many indigenous biotypes. Because of its broader host range and higher fecundity, virus-transmission efficiency is more [11, 34, 47, 50, 55] and becoming a major constrains for the production of several crops in the India. Apart from this, the emergence of novel viruses due to the recombination of begomoviruses and multiple satellite DNA molecules leading to the production of diverse symptoms and increase in newer host adaptation [13, 48, 55].The abundant number of begomoviruses and the continued reports of new species with the high degree of genetic diversity within species [12, 19, 20, 45] perhaps suggests that, the begomoviruses are subjected to high mutation rate [18] generating highly diverse populations in a short time. The recombination between their ssDNA of begomoviruses might have been boosted the epidemics in all most all the crops [40].

In the present study, we have characterized for the first time the association of distinct monopatite begomovirus related to Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus (CLCuBV) infecting okra in India. This will provide further evidence for the begomovirus recombination to suit to the host adaptation of recombinant begomovirus in Indian subcontinent.

Materials and Methods

Virus source and maintenance of the virus isolate

Nine infected leaf samples from okra plants exhibiting symptoms of upward leaf curling, vein clearing, vein thickening and yellowing (Fig. 1a, b) along with non-symptomatic samples were collected from major okra growing area of Bangalore rural district, Karnataka, India. Out of these two samples showed positive amplification to cotton leaf curl virus in PCR detection carried out using virus specific primers and designated as virus- isolate OY136A. The cultures (each from one sample) of this isolate were established by whitefly transmission and maintained on susceptible okra cultivar (cv. 1685) by periodic transfer as described by Venktaravanappa et al. (2012). Samples from both field infected plants and glasshouse inoculated plants were used for further studies.

Fig. 1.

Okra plant showing yellow vein, vein thickening and upward curling symptoms under natural conditions (a and b). Okra cv. 1685 showing yellow vein symptoms inoculated with field sample by whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) transmission (c)

DNA isolation, PCR amplification, cloning and sequencing of viral genome

Total nucleic acids were extracted from symptomatic plants maintained in glasshouse condition and two field samples (two) along with the non symptomatic plants by CTAB method [17]. Full length genome of virus isolate was amplified by PCR using protocol and primers described by Venkataravanappa et al. [56]. The primers were designed specifically to DNA-A component using BYVMV and other begomoviruses available in GenBank. In order to rule out the mixed infections, these primers were designed with a significant length of sequence overlap (~200 bp). To amplify or detect the presence of DNA-B components from the infected plant sample, the universal degenerate primers were used [6, 43, 56]. Amplification products of begomovirus and beta satellite were cloned into the pTZ57R/T vector (Fermentas, Germany) according to the manufactures instructions. The complete nucleotide sequence of clones were determined by automated DNA sequencer ABI PRISM Betasatellites were amplified using universal primer pair Beta01/Beta023730 (Applied Biosystems) from Anshul Biotechnologies DNA Sequencing facility, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India.

Comparison of sequence and detection of recombination events

The comparison of nucleotide sequence of DNA-A component of isolate (OY136A) from okra was carried out with selected begomovirus sequences retrieved from database (Supplementary Table 1). Sequence identity matrixes for the begomoviruses were generated using Bioedit Sequence Alignment Editor (version 5.0.9) [21] and phylogenetic tree was generated by MEGA 5.0 software [53] using the neighbour joining method with 1,000 bootstrapped replications. The phylogenic evidence for recombination was detected by alignment of selected begomoviruses sequences along with okra isolate with Splits-Tree version 4.3 using the Neighbor-Net method [26]. The method depicts the conflicting phylogenetic signals caused by recombination as cycles within unrooted bifurcating trees. Recombination analysis was carried out using Recombination detection program (RDP), GENECOV, Bootscan, Max Chi, Chimara, Si Scan, 3Seq which are integrated in RDP 3 to detect the recombination break points [33]. Default RDP settings with 0.05 P value cutoff throughout and standard Bonferroni correction were used.

Virus–vector relationship

The virus–vector relationship viz. effect of vector number on the relative efficiency of virus transmission, sex of whitefly and different AAP and IAP were determined. The insects were given access to OY136A virus isolate on okra plants (cv. 1685) maintained under glasshouse in separate whitefly proof cages. Whiteflies with acquisition access given on healthy okra plants were used as control to rule out their contamination with any other viruses. Ten of okra plants were used for each experiment on vector number, acquisition and inoculation access period. In all experiments, AAP and IAP of 24 h are given, expect in determining the AAP and IAP. Ten viruliferous whiteflies per plant were used for transmission except in experiment involved in assessing the effect of number of vectors on transmission efficiency.

The minimum acquisition access period required for virus transmission by whiteflies was determined by giving given set periods (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 min and 1, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 24 h) of AAP on infected okra cv. 1685. Then, 10 flies per healthy susceptible okra plant (separately caged) (cv. 1685) were transferred in each case and 24 h inoculation access period was given. Similarly for determining minimum IAP, 24 h AAP for flies was given, subsequently 10 flies per healthy okra plant were transferred and were allowed with set IAP of (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 min and 1, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 24 h). The effect of vector number on transmission efficiency of virus was assessed by varying the numbers of whiteflies (1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 20 insects per plant) in transmission experiments. The sex based whitefly transmission was carried out using male and female adult whiteflies separately. To know the effect of the age of the plants on virus transmission by vector, fifty okra plants in each age group of 7, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 days after germination were inoculated.

After the specified periods of IAP, in all the experiments inoculated plants were sprayed with 0.01 % imidacloprid (Confidor) for killing the viruliferous whiteflies used for transmission. The test plants were scored for infection by the virus at weekly intervals for the appearance of characteristic YVMD symptoms.

Graft transmission

The infected plants maintained in the glass house were used as a source of scion material for grafting. Ten non-symptomatic okra plants were used as rootstock. Side-veneer grafting was carried out with scions taken from infected plant of the same variety (cv. 1685) which allows to retain the shoot of root stock. The grafted portion was tied with a polythene strip and scion was covered with a polythene bag. The grafted plants were kept in a cool place in the glasshouse for symptom production.

Host range and symptomatology

Healthy seedling of different plant species, belonging to diverse families viz Malvaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Solanaceae and Cucurbitaceae, were grown under insect-free conditions in the glasshouse. Seedlings at the first-leaf stage were transplanted into polythene bags containing mixture of soil and farmyard manure at 2:1 proportion. Individual seedlings were inoculated with 15 viruliferous whiteflies with 24 h of AAP and IAP each and maintained in the glasshouse for symptoms development as described above.

Confirmation of inoculated plants for the presence of virus

Confirmation for the presence of virus in the inoculated plants in all assays/transmission studies were done by dot blot with probe to the putative CP gene of CLCuBV (GU112003). Preparation of DNA probe was employed following a method described by manufacturer (Roche diagnosis, Germany). The nucleic acid of infected samples (5 μl) was heated for 5 min at 100 °C on water bath and incubated at 4 °C before load onto the membrane. After cooling the DNA was applied through on the commercial device (Dot Blot 96 System, Biometra, Germany) directly on the nitrocellulose membrane. Then the membrane was air dried and DNA was cross-linked to the membrane by exposure to ultraviolet light (in a crosslinker device Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, USA) for 3 min. The pre-hybridization, hybridization and detection procedures were carried out according to the protocol given in DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit II (Roche diagnostics). Nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) and X-phosphate based colorimetric detection was used to visualize labeled spots.

Results

Molecular characterization of virus isolate

The symptoms produced on whitefly inoculated okra plants were same as symptoms recorded in the field. All inoculated okra seedlings showed initially yellow vein symptoms, with minimum incubation period of 10–12 days and as the disease progressed, the infected leaves become curled, and giving appearance similar to those observed on the naturally field infected plants (Fig. 1c).

The complete genome of the virus isolate OY136A was amplified as overlapping fragments and sequenced to yield the complete genome sequence from both field and glasshouse samples. Attempts to amplify DNA-B components by PCR using different sets of specific primers were unsuccessful in these samples. Amplification of betasatellite by PCR with a universal abutting primer pair beta0l/beta02 confirmed or provided evidence for the association of virus isolate with the betasatellite. These results suggested that, begomovirus isolate infecting okra under present study is monopartite.

Genome organization and sequence analysis

The complete nucleotide sequence of the virus isolate (OY136A) was determined in both orientations and it was found to be 2,758 nucleotides nts in length. This sequence is available in the database under accession number of GU112003. The sequence contained features typical of other monopartite begomoviruses, with two open reading frames (ORFs) [AV1 (CP), AV2] in virion-sense strand and five ORFs [AC1 (Rep), AC2, AC3, AC4,AC5] in complementary-sense strand, separated by an intergenic region (IR).

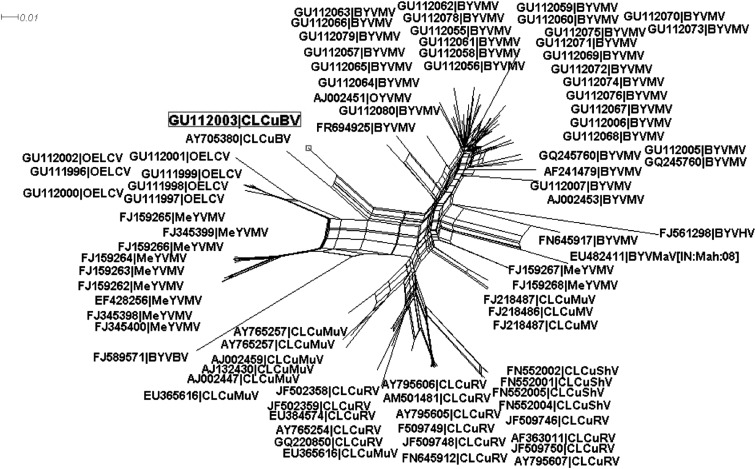

Nucleotide sequence identity of this virus isolate was obtained by comparing with the representative begomoviruses from the database. The results showed the highest level of nucleotide sequence identity (92.8 %) to that of CLCuBV followed by Okra enation leaf curl virus (81.1–86.2 %) (Table 1). This indicates that, the begomovirus (OY136A) under the present study is a strain of CLCuBV (AY705380) based on the currently applicable species demarcation threshold for begomoviruses (89 %) [19]. This result is further supported by phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 2), which clearly indicating clustering or close grouping of the begomovirus (OY136A) with CLCuBV (AY705380) for which a full-length sequence is available in the databases.

Table 1.

Pairwise percent of nucleotide identities between the genomic components and amino acid sequence identities of encoded genes from the Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus [IN: Bangalore: okra: 06] with the components and genes of selected other begomoviruses available in the databases

| Begomovirusa | Complete sequence (percentage NSI) | Intergenic region (percentage NSI) | Gene (percentage amino acid sequence identity) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV2 | CP | Rep | TrAP | REn | AC4 | AC5 | |||

| BYVBV (1)b | 76.3 | 59.5 | 66.9 | 82.0 | 86.5 | 67.3 | 67.9 | 65.0 | 50.0 |

| BYVHV (1) | 74.4 | 57.8 | 71.0 | 93.3 | 77.1 | 58.0 | 72.0 | 50.0 | 61.0 |

| BYVMaV (1) | 78.1 | 53.7 | 75.2 | 92.9 | 81.2 | 84.6 | 84.3 | 23.7 | 64.4 |

| OYVMV (1) | 81.8 | 48.5 | 73.5 | 93.7 | 88.4 | 82.6 | 79.8 | 70.0 | 61.8 |

| CLCuBV (1) | 92.8 | 88.0 | 93.3 | 99.6 | 90.6 | 88.0 | 91.0 | 75.0 | |

| BYVMV (33) | 79.1–86.0 | 49.0–74.9 | 50.4–76.8 | 88.6–93.3 | 82.0–93.6 | 80.6–87.3 | 77.6–85.8 | 42.1–99.0 | 58.4–83.0 |

| CLCuMuV (6) | 80.1–82.6 | 51.2–68.2 | 65.2–76.8 | 80.1–92.9 | 85.0–90.6 | 80.6–82.0 | 58.2–80.5 | 22.5–79.0 | 92.6–93.0 |

| CLCuRV (15) | 79.0–81.3 | 59.1–73.8 | 59.5–76.0 | 84.7–92.9 | 84.2–86.7 | 64.0–81.3 | 64.4–79.8 | 57.1–66.0 | – |

| CLCuShv (4) | 82.3–82.7 | 77.2–76.9 | 61.1–67.7 | 92.1–93.7 | 89.2–91.1 | 80.6–81.3 | 77.6–79.1 | 65.0–68.0 | – |

| OELCuV (7) | 81.1–86.2 | 70.0–70.3 | 85.1–85.9 | 77.1–78.5 | 85.6–95.5 | 85.3–97.3 | 86.5–90.2 | 62.0–81.0 | – |

| MeYVMV (11) | 80.0–84.9 | 64.2–78.6 | 76.0–86.7 | 82.0–92.5 | 85.6–91.1 | 80.6–86.0 | 75.3–83.5 | 56.2–73.5 | 11.7–69.0 |

NSI nucleotide sequence identity

aThe species are indicated as Bhendi yellow vein Bhubhaneswar virus (BYVBhV) [acc. no. FJ589571], Bhendi yellow vein Haryana virus (BYVHaV) [FJ561298], Bhendi yellow vein Maharashtra virus (BYVMaV) [EU482411], Bhendi yellow vein mosaic virus (BYVMV), Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus (CLCuBaV), Cotton leaf curl Multan virus (CLCuMuV), Cotton leaf curl Shahdadpur virus (CLCuShV), Mesta yellow vein mosaic virus (MeYVMV), Okra yellow vein mosaic virus (OYVMV) and Cotton leaf curl Rajasthan virus (CLCuRV). For each column the highest value is underlined

bNumbers in the parenthesis of this column are sequences that particular virus from the databases used for comparisons

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic trees constructed from aligned complete nucleotide sequences of DNA-A components of CLCuBV-[India: Bangalore: okra: 2006] with other begomoviruses using Neighbor-joining algorithm. Horizontal distances are proportional to sequence distances, vertical distances are arbitrary. The trees are unrooted. A bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates was performed and the bootstrap percent values more than 50 are numbered along branches

When individually encoded protein of the virus was compared with other begomoviruses, the ORFV2 and CP showed maximum amino acid identity with CLCuBV (AY705380). In the case of the AC1-encoded Rep protein showed maximum amino acid identity with BYVMV-IN and ORFC2 (TrAP), C3 (REn) and C4 have highest levels of identity with OELCuV-IN. However, for ORFAC5 shared highest amino acid sequence identity with CLCuMuV (Table 1). The intergenic region (IR) is ~290 nts in length and is similar to that of CLCuBV more than 88 % sequence identity and, only 53.7–78.6 % with IRs of other begomoviruses. The IR contains a predicted stem-loop sequence with conserved nonanucleotide sequence (TAATATTAC) in the loop, which is found in the majority of geminiviruses characterized to date and marks the origin of virion-strand DNA replication [25]. Within the intergenic region, incomplete direct repeats of an iteron (GCTCT), Rep binding motif was detected adjacent to the TATA box of the Rep promoter. Rep binds in a sequence-specific fashion to iterated DNA motifs (iterons) functioning as essential elements for virus-specific replication. This type of iteron sequence was found only in CLCuBV. Further, the betasatellite (KC608158) associated with the virus shared more than 95 % nucleotide sequence identity (data not shown) with cotton leaf curl betasatellites (CLCuB) suggesting it as a CLCuB species.

Recombination

Initially the sequences of other begomoviruses infecting malvaceous, solanaceous and cucurbit species retrieved from database were aligned with the sequence of the present isolate described here and constructed a neighbor-network (using the program Splits-Tree version 4.11.3). Such networks are capable of graphically displaying patterns of non-tree-like evolution such as those expected in the presence of recombination (Fig. 3). This has indicated the phylogenetic conflict existing among the analyzed sequences providing evidence for recombination. Based on this information, sequences were subjected to break point analysis know more about recombination pattern using RDP3 with default settings [33]. Analyses showed that BYVMV and CLCuMuV probably contributed with genetic material [DNA fragments of 1–799 nt (P value = 3.973 × 10−26), ~1,800–2,064 nt (P value = 2.522 × 10−21) respectively] (Fig. 4; Table 2) to the emergence of new strain of CLCuBV (OY136A) infecting okra in India.

Fig. 3.

Neighbor-Net generated for the DNA-A component of CLCuBV-[India: Bangalore: okra: 2006] with other begomoviruses has shown significant signals for phylogenic conflict indicating as recombinant virus

Fig. 4.

Recombination analysis of complete genome of-[India: Bangalore: okra: 2006]. The Begomoviruses given are Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus (CLCuBV) and Cotton leaf curl Multan virus (CLCuMV). Sequence of indeterminate origin is indicated as “unknown”. The box below begomovirus genome diagram indicates the approximate position of recombination occurred in the genome of the begomoviruses

Table 2.

Breakpoint analysis of DNA-A components and their putative parental sequences of Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus [IN: Bangalore: okra: 06]

| Break point begin-end | Major parent | Minor parent | P values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDP | GENECOV | Max chi | Chimera | Si scan | 3Seq | |||

| 1–1,799 | BYVMV [IN: Guntur: OY112: 05] GU112005 | BYVMV [IN: Madurai: 00] AF241479 | 1.019 × 10−13 | 4.169 × 10−17 | 1.414 × 10−18 | 6.694 × 10−16 | 3.973 × 10−26 | 2.976 × 10−13 |

| 1,800–2,064 | BYVMV [IN: Karnal: OY80B: 05] GU112077 | CLCuMV [IN: Raj: 07] EU365616 | 9.159 × 10−4 | 1.36 × 10−7 | 6.107 × 10−5 | 2.849 × 10−4 | 2.522 × 10−21 | 1.195 × 10−3 |

Virus–vector relationship

The relationship of CLCuBV (OY136A) with its vector B. tabaci was characterized. It was found to be 100 % transmission efficiency on susceptible okra plant (cv 1685) when 10 flies per plant were used with AAP and IAP of 24 h each. A minimum of two whiteflies per plants was found to be effective for disease transmission (10 %)with a minimum incubation period of 10–12 days to produce typical symptoms under controlled conditions (Supplementary Table 2).However, percent transmission was increased with increase in number of whiteflies and achieved 100 % transmission, when 10 or more whiteflies per plant were used. The adult whiteflies required a minimum 15 min of AAP to acquire the virus and become viruliferous with transmission efficiency of 10 %. As the time of AAP increased, the percent transmission also increased and achieved 100 % transmission, when IAP of 12 h or more are given (Supplementary Table 3)The vector requires a minimum 10 min of IAP to transmit the virus with transmission efficiency of 10 %. As the time of IAP increased, the percent transmission also increased and achieved 100 % transmission, when IAP of 12 h or more are given suggesting the latent period requirement of the virus in the vector.

Investigation into a possible efficiency disparity of virus transmission between males and females revealed that, both sexes of B. tabaci acquired virus from infected okra plants and transmitted the virus to uninfected susceptible okra plants. However, higher of transmission efficiency was recorded with the females (75 %) than the males (50 %) (Supplementary Table 4). Further, study on the age of okra seedlings susceptibility, the young seedlings up to the age of 15 days was found to be highly vulnerable to the virus (Supplementary Table 5). As the age of the test plants increased the per cent transmission decreased (When 20, 25 and 30 days old plants were inoculated; the percentages of transmission were 70.00, 60.00 and 40.00 respectively) suggesting their susceptibility to virus infection decreased with the increase in age. The plants inoculated with the non-viruliferous whiteflies given AAP on healthy okra plants were failed to express the symptoms served as a negative control ruling out the whitefly colony contamination by other viruses in all the above experiments. The virus was successfully transmitted by grafting with transmission efficiency of 65 % and the grafted okra plants showing symptoms of yellow vein mosaic within 20–25 days after grafting.

Host range

The host range of the virus isolate was studied by whitefly inoculation to different plant species belonging to diverse families (Table 3). Of these, five plant species belonging to Solanaceae [N. benthamiana, N. glutinosa. N. tabacum, N. tabacum Cv. Anand, N. tabacum Cv. Jayashree], and two plant species belongingto Malvaceae [okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) and Althaea rosea.] developed symptoms after 10–35 days after inoculation. The infection in these plant species was further confirmed by dot blot hybridization with probe developed to the putative CP gene of CLCuBV (GU112003). The different tobacco species produced mild leaf curling, okra plant produced initially yellow vein mosaic and later the leaves become upward leaf curled and Althaea plants developed mild leaf curl symptoms. This result suggests that, the host range of the virus is limited.

Table 3.

Determination of host range of Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus [IN: Bangalore: okra: 06] by insect transmission

| Plant species | No. of infected/inoculated | Transmission (%) | Days taken for symptom expression/latent period (days) | Symptoms | Reaction to dot blot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family: Solanaceae | |||||

| Nicotiana benthamiana | 20/20 | 100 | 25–30 | Mild leaf curling | ++ |

| N. glutinosa | 19/20 | 95 | 30–35 | Mild leaf curling | ++ |

| N. tabaccum Cv. Anand | 18/20 | 90 | 30–35 | Mild leaf curling | ++ |

| N. tabaccum Cv. Jayashree | 20/20 | 100 | 25–30 | Mild leaf curling | ++ |

| Datura stramonium | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Capsicum annuum L. | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Lycopersicon esculentum | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Family: Malvaceae | |||||

| Malvastrum coromandelianum | 00/20 | NS | – | – | |

| Abelmoschus esculentus L. | 20/20 | + | 10–12 | Yellow vein mosaic | ++ |

| Althaea rosea L. | 20/20 | + | 20–25 | Mild curling of leaves | ++ |

| Gossypium herbaceum L. | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Acalypha indica | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Hibiscus rose-sinensis | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Sida cordifolia | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Gossypium hirsutum | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Family: Euphorbiaceae | |||||

| Crotonbon plandianum | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Euphorbia hirta | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Phyllanthus niruri | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Euphorbia geniculata | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Croton bonplandianum | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Family: Cucurbitaceae | |||||

| Cucurbita moschata | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Cucurbita pepo | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

| Cucumis sativus | 00/20 | NS | – | – | – |

Bemisia tabaci (10–15 number per plant) were used with 24 h each of acquisition and inoculation access periods for inoculation of the test plant species

NS not transmitted

Discussion

Begomoviruses are considered to be the most important viral pathogens on various crops due to their high frequency and the severity of diseases they cause in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world [55]. In India, begomoviruses impose particularly serious constraints for the production of Okra. Over the past decade, epidemics caused by begomoviruses have been attributed to the introduction of B biotype of whitefly resulting in efficient dissemination of begomoviruses to new cultivated hosts by and emergence of new recombinant virus variants from mixed infections [1]. These new viruses induce array of diverse symptom like leaf curling, yellow vein and leaf distortion in the plants they infect, which are most frequent symptoms associated with infections caused by begomoviruses [23, 49, 57].

The begomovirus characterized in the present study, share highest identity with CLCuBV and have genome organization typical to the monopartite begomoviruses reported earlier. The leaf curl disease of cotton is associated with at least seven begomoviruses [28, 31, 32], among them, one is CLCuBV [15]. The cut-off value of 89 % nucleotide sequence identity criteria for demarcating species of begomoviruses have been proposed by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) based on to the large number of characterized begomoviruses [19].The virus isolates displaying more than 90 % nucleotide sequence identity of the DNA-A component were considered as strains rather than different viruses [37]. This indicates that the begomovirus (OY136A) characterized here causing severe yellow vein and upward leaf curling in okra is a strain of CLCuBV, for which we propose the descriptor CLCuBV-[India: Bangalore: okra: 2006]. This suggests that, CLCuBV might have spread into near okra fields from the heavily infected cotton plants present in the kitchen gardens near fields of okra in Bangalore with the help of contaminated whiteflies during transmission and get adapted to the okra by undergoing recombination/reassortment. So far only one report of CLCuBV infecting cotton from India is available [15]. However, the details of virus–vector relation with respect to CLCuBV are not reported till date. This is the first report of CLCuBV infecting okra from the same region.

The recent survey for YVMD in okra fields of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu and PCR detection of collected samples using virus specific primers revealed that the virus is present in both the states (data not shown). However, more prevalent viruses are BYVMV and Bhendi yellow vein India virus (BYVIV).

The interesting thing observed in the genome organization of this virus is, the presence of AC5 region, which is absent in CLCuBV and its next close relative OELCuV suggesting more complex recombination nature in its evolution than the results showing in recombination analyses. Therefore, it may also be possible that CLCuBV might have been present in okra and spilled to cotton. More sampling for CLCuBV in okra and cotton may answer this question. Further, analysis indicated that, this begomovirus shared highest sequence similarities for most of its sequence with begomoviruses causing leaf curl of cotton and yellow mosaic of okra (BYVMV, OELCuV and CLCuMuV). This suggests that, the begomovirus reported here might have been derived through genetic exchanges from related begomoviruses and evolved as a new recombinant begomovirus with inter-specific recombination events and recombination with members of other genera or pseudo-recombination [38]. The phenomenon of mixed infections is extremely important for virus evolution, because mixed infections are the prerequisite for the occurrence of natural recombination events, which may contribute to the appearance of new begomoviruses [38, 46].

The virus was successfully transmitted by whitefly in accordance with other begomoviruses known to date [8, 41]. The minimum AAP for virus was 10 min and the transmission frequency increased with longer AAPs is in agreement with a similar previous reports [14, 41, 54]. The inoculation efficiency was found to be 100 % following an initial AAP of 24 h, indicating that the latent period had been satisfied in 24 h or less, also characteristic of begomoviruses [10, 42]. The transmission efficiency of females are more, may be because of acquisition of more viral particles due to the body size of females which are larger than males.

In conclusion, the expanding diversity of the begomoviruses resulting in emergence of new virus strains and/or species and there subsequent ability to infect new hosts is posing a biggest challenge for disease management. More studies related these phenomena have to be taken up in order keep face with evolution of viruses to address the challenge. Otherwise, these disease complexes may prove serious threat to Indian economy.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by ICAR NETWORK Project on development of diagnostics to emerging plant viruses, Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Government of India, New Delhi.

Contributor Information

C. N. Lakshminarayana Reddy, Email: cnlreddy@gmail.com

M. Krishna Reddy, Email: mkreddy.iihr@gmail.com

References

- 1.Albuquerque LC, Martin DP, Avila AC, Inoue-Nagata AK. Characterization of tomato yellow vein streak virus, a begomovirus from Brazil. Virus Genes. 2010;40:140–147. doi: 10.1007/s11262-009-0426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briddon RW, Markham PG. Cotton leaf curl virus disease. Virus Res. 2000;71:151–159. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(00)00195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briddon RW, Stanley J. Subviral agents associated with plant single-stranded DNA viruses. Virology. 2006;344:198–210. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briddon RW, Bull SE, Amin I, Idris AM, Mansoor S, Bedford ID, Dhawan P, Rishi N, Siwatch SS, Abdel-Salam AM, Brown JK, Zafar Y, Markham PG. Diversity of DNA beta: a satellite molecule associated with some monopartite begomoviruses. Virology. 2003;312:106–121. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briddon RW, Bull SE, Amin I, Mansoor S, Bedford ID, Rishi N, Siwatch SS, Zafar MY, Abdel-Salam AM, Markham PG. Diversity of DNA 1; a satellite-like molecule associated with monopartite begomovirus-DNA β complexes. Virology. 2004;324:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briddon RW, Bull SE, Mansoor S, Amin I, Markham PG. Universal primers for the PCR-mediated amplification of DNA-β: a molecule associated with some monopartite begomoviruses. Mol Biotech. 2002;20:315–318. doi: 10.1385/MB:20:3:315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briddon RW, Mansoor S, Bedford ID, Pinner MS, Saunders K, Stanley J, Zafar Y, Malik KA, Markham PG. Identification of DNA components required for induction of cotton leaf curl disease. Virology. 2001;285:234–243. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briddon RW, Pinner MS, Stanley J, Markham PG. Geminivirus coat protein gene replacement alters insect specificity. Virology. 1990;177:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90462-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JK. The status of Bemisia tabaci (Genn.) as a pest and vector in world agroecosystems. FAO Plant Prot Bull. 1994;42:3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JK, Nelson MR. Host range and vector relationships of cotton leaf crumple virus. Plant Dis. 1987;71:522–524. doi: 10.1094/PD-71-0522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JK, Bird J, Frohlich DR, Russell RC, Bedford ID, Markham PG. The relevance of variability within the Bemisia tabaci species complex to epidemics caused by sub-group–III geminiviruses. In: Gerling D, Mayer RT, editors. Bemisia 1995, Taxonomy, Biology, Damage, Control and Management 77–89. Andover: Intercept Ltd; 1995. pp. 702.

- 12.Bull SE, Briddon RW, Sserubombwe WS, Ngugi K, Markham PG, Stanley J. Genetic diversity and phylogeography of cassava mosaic viruses in Kenya. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:3053–3065. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bull SE, Tsai WS, Briddon RW, Markham PG, Stanley J, Green SK. Diversity of begomovirus DNA β satellites of non-malvaceous plants in east and south east Asia. Arch Virol. 2004;149:1193–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capoor SP, Varma PM. Yellow vein mosaic of H.esculentus L. Indian J Agric Sci. 1950;20:217–230. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chowda Reddy RV, Muniyappa V, Colvin J, Seal S. A new begomovirus isolated from Gossypium barbadense in southern India. Plant Pathol. 2005;54:570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2005.01214.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De La Torre-Almaraz R, Monsalvo-Reyes A, Romero-Rodriguez A, Argüello-Astorga GR, Ambriz-Granados S. A new begomovirus inducing yellow mottle in okra crops in Mexico is related to Sida yellow vein virus. Plant Dis. 2006;90:378. doi: 10.1094/PD-90-0378B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus. 1990;12:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffy S, Holmes EC. Phylogenetic evidence for rapid rates of molecular evolution in the single-stranded DNA begomovirus tomato yellow leaf curl virus. J Virol. 2008;82:957–965. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01929-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fauquet CM, Briddon RW, Brown JK, Moriones E, Stanley J, Zerbini M, Zhou X. Geminivirus strain demarcation and nomenclature. Arch Virol. 2008;153:783–821. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbertson R, Rojas M, Russell D, Maxwell D. Use of the asymmetric polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing to determine genetic variability of bean golden mosaic geminivirus in the Dominican Republic. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2843–2848. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-11-2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanley-Bowdoin L, Settleage SB, Orozco BM, Nagar S, Robertson D. Geminivirus:models for plant DNA replication, transcription, and cell cycle regulation. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1999;18:71–106. doi: 10.1080/07352689991309162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison BD, Robinson DJ. Natural genomic and antigenic variation in whitefly-transmitted geminivirus (Begomoviruses) Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1999;37:369–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.37.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernandez-Zepeda C, Idris AM, Carnevali G, Brown JK, Moreno-Valenzuela OA. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic relationships of two new bipartite begomovirus infecting plants in Yucatan, Mexico. Virus Genes. 2007;35:369–377. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heyraud F, Matzeit V, Kammann M, Schafer S, Schell J, Gronenborn B. Identification of the initiation sequence for viral-strand DNA synthesis of wheat dwarf virus. EMBO J. 1993;12:4445–4452. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jose J, Usha R. Bhendi yellow vein mosaic disease in India is caused by association of a DNA β satellite with a begomovirus. Virology. 2003;305:310–317. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirthi N, Priyadarshini CGP, Sharma P, Maiya SP, Hemalatha V, Sivaraman P, Dhawan P, Rishi N, Savithri HS. Genetic variability of begomoviruses associated with cotton leaf curl disease originating from India. Arch Virol. 2004;149:2047–2057. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazarowitz SG. Geminiviruses:genome structure and gene function. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1992;11:327–349. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lefeuvre P, Martin DP, Harkins G, Lemey P, Gray AJA, Meredith S, Lakay F, Monjane A, Lett J-M, Varsani A, Heydarnejad J. The spread of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus from the Middle East to the world. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001164. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansoor S, Amin I, Iram S, Hussain M, Zafar Y, Malik KA, Briddon RW. Breakdown of resistance in cotton to cotton leaf curl disease in Pakistan. Plant Pathol. 2003;52:784. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2003.00893.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mansoor S, Briddon RW, Bull SE, Bedford ID, Bashir A, Hussain M, Saeed M, Zafar MY, Malik KA, Fauquet CM, Markham PG. Cotton leaf curl disease is associated with multiple monopartite begomoviruses supported by single DNAβ. Arch Virol. 2003;148:1969–1986. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0149-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin DP, Lemey P, Lott M, Vincent M, Posada D, Lefeuvre P. RDP3: a flexible and fast computer program for analyzing recombination. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2462–2463. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morales FJ, Anderson PK. The emergence and dissemination of whitefly-transmitted geminiviruses in Latin America. Arch Virol. 2001;146:415–441. doi: 10.1007/s007050170153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navot N, Pichersky E, Zeidan M, Zamir D, Czosnek H. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus: a whitefly-transmitted geminivirus with a single genomic component. Virology. 1991;185:151–161. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nawaz-ul-Rehman MS, Nahid N, Mansoor S, Briddon RW, Fauquet CM. Post-transcriptional gene silencing suppressor activity of the alpha-Rep of non-pathogenic alphasatellites associated with begomoviruses. Virology. 2010;405:300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Padidam M, Beachy RN, Fauquet CM. Tomato leaf curl geminivirus from India has a bipartite genome and coat protein is not essential for infectivity. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:25–35. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-1-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Padidam M, Sawyer S, Fauquet CM. Possible emergence of new geminiviruses by frequent recombination. Virology. 1999;265:218–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paprotka T, Metzler V, Jeske H. The complete nucleotide sequence of a new bipartite begomovirus from Brazil infecting Abutilon. Arch Virol. 2010;155:813–816. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0647-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pita JS, Fondong VN, Sangare A, Otim-Nape GW, Ogwal S, Fauquet CM. Recombination, pseudorecombination and synergism of geminivirus are determinant keys to the epidemic of severe cassava mosaic disease in Uganda. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:655–665. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-3-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raychaudhuri SP, Nariani TK. Viruses and Mycoplasma diseases of plants in India. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH Publishing company; 1977. pp. 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Retuerma ML, Pableo GO, Price WC. Preliminary study of the transmission of Philippines tomato leaf curls virus Bemisia tabaci Philippines. Phytopathology. 1971;7:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rojas MR, Gilbertson RL, Russel DR, Maxwell DP. Use of degenerate primers in the polymerase chain reaction to detect whitefly-transmitted geminiviruses. Plant Dis. 1993;77:340–347. doi: 10.1094/PD-77-0340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rojas MR, Hagen C, Lucas WJ, Gilbertson RL. Exploiting chinks in the plant’s armor: evolution and emergence of geminiviruses. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2005;43:361–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanz AI, Fraile A, Gallego JM, Malpica JM, Garcia-Arenal F. Genetic variability of natural populations of cotton leaf curl geminivirus, a single-stranded DNA virus. J Mol Evol. 1999;49:672–681. doi: 10.1007/PL00006588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanz AI, Fraile A, Garcia Arenal F, Zhou XP, Robinson DJ, Khalid S, Butt T, Harrison BD. Multiple infection, recombination and genome relationships among begomovirus isolates found in cotton and other plants in Pakistan. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1839–1849. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-7-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sastry KSM, Singh SJ. Effect of yellow vein mosaic virus infection on growth and yield of okra crop. Indian Phytopathol. 1974;27:294–297. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saunders K, Bedford ID, Stanley J. Pathogenicity of a natural recombinant associated with ageratum yellow vein disease: implications for geminivirus evolution and disease aetiology. Virology. 2001;282:8–47. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seal SE, Vandenbosch F, Jeger MJ. Factors influencing begomovirus evolution and their increasing global significance: implications for sustainable control. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2006;25:23–46. doi: 10.1080/07352680500365257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sinha SN, Chakrabarthi AK. Effect of yellow vein mosaic virus infection on okra seed production. Seed Res. 1978;6:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stanley J. Infectivity of the cloned geminivirus genome requires sequences from both DNAs. Nature. 1983;305:643–645. doi: 10.1038/305643a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stanley J, Bisaro DM, Briddon RW, Brown JK, Fauquet CM, Harrison BD, Rybicki EP, Stenger DC. Geminiviridae. In: Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA, editors. Virus taxonomy, VIIIth report of the ICTV. London: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2005. pp. 301–326. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Varma PM. Studies on the relationship of the bhendi yellow vein mosaic virus and vector, the whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) Indian J Agric Sci. 1952;22:75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Varma A, Malathi VG. Emerging geminivirus problems: a serious threat to crop production. Annu App Biol. 2003;142:145–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2003.tb00240.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Venkataravanappa V, Reddy CNL, Jalali S, Krishna Reddy M. Molecular characterization of distinct bipartite begomovirus infecting bhendi (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) in India. Virus Genes. 2012;44:522–535. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0732-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang XY, Xie Y, Zhou XP. Molecular characterization of two distinct begomoviruses in China. Virus Genes. 2004;29:303–309. doi: 10.1007/s11262-004-7432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.