Abstract

Background:

This preliminary publication describes acute temperature effects after manual Khalifa therapy.

Aims:

The goal of this study was to describe temperature distribution and the effects on surface temperature of the knees and feet in patients with completely ruptured anterior cruciate ligament before and immediately after the manual therapy.

Materials and Methods:

Ten male patients were investigated with thermal imaging. An infrared camera operating at a wavelength range of 7.5-13 μm was used. Temperature was analyzed at three locations on both knees and in addition on both feet.

Results:

The study revealed that baseline temperature of the injured knee differed from that of the untreated control knee. After the therapy on the injured knee, the surface temperature was significantly increased on both knees (injured and control). There were no significant changes in the temperature of the feet.

Conclusions:

Further studies using continuous thermal image recording may help to explain the details concerning the temperature distribution.

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament, Khalifa therapy, Knee, Temperature, Thermal imaging

Introduction

Thermic and infrared radiation (IR) is not detectable by the human eye. The energy lies within the region of the electro-magnetic spectrum, which is perceived as being warm. Infrared cameras produce pictures of invisible infrared or heat radiation, thus enabling exact temperature measurements. IR is emitted by all objects at temperatures above absolute zero, and the amount of radiation increases with temperature. Thermography, which is also used in complementary and alternative medicine,[1,2] is accomplished with an IR camera calibrated to display temperature values across an object like the human body. Therefore, thermography allows noncontact measurements of the human body.

As mentioned in a previous publication,[3] manual therapy and acupressure are important medical methods. A special kind of manual therapy is performed by Mohamed Khalifa in Hallein in Austria for more than 30 years.[4,5] His treatment is mainly based on pressure and the application of certain rhythms, and with it he seems to be able to accelerate the self-healing processes of the human body.[4,5] The first scientific publication on this topic has been published recently in the North American Journal of Medical Sciences.[5]

The goal of the present study was to investigate possible acute effects of Khalifa’s therapy on thermal imaging of surface temperature of the knees and feet in patients with a completely ruptured anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).

Materials and Methods

Patients

The patients were informed about the nature of the investigation. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Salzburg, Austria (21-232 11-12 sbg), and registered at clinicaltrials. gov under the ID-no. NCT01762371. All participants provided written informed consent. Ten male patients with a mean age ± SD of 35.9 ± 6.1 years (range: 19-45 years), a height of 177.6 ± 7.2 cm, and a weight of 77.0 ± 7.7 kg were investigated.

Inclusion criteria comprised a unilateral complete rupture of the ACL, verified by magnetic resonance imaging, not preceded by surgical intervention. Patients had to be male, aged between 18 and 49 years, with normal body weight (body mass index [BMI] 18-26). Their exercise level before the accident had to be regular. After the rupture, they had to have experienced at least one giving-way (knee instability), and the knee range-of-motion had to be reduced or inhibited (dysfunction); still, they had to be able to walk 10 m without crutches and stand on one leg. Patients were excluded from the study if they suffered from metabolic disorders like diabetes mellitus or autoimmune diseases.

Two of the patients had a rupture of the left ACL and the remaining eight had a rupture of the right ACL. Three had received the injury when playing soccer, six when skiing, and one when getting out of his car.

Manual therapy

Khalifa therapy [Figure 1a] restores the function of the knee in a natural way. It is described as functional-pathological.[4] In this approach, function is the primary concern, not anatomy. The most important thing is not the ruptured ligament itself, but its function/dysfunction. Khalifa stimulates the self-healing processes in the human body by applying pressure to the skin in different amplitudes that are transformed to frequencies through piezoelectric mechanisms of cell membranes.[6,7,8] Further details are described in recent publications.[4,5]

Figure 1.

A new manual therapy, investigated with infrared thermography. (a) Manual therapy in Hallein, Austria by Mohamed Khalifa. Data acquisition (thermal imaging; (b) and documentation (c) of surface body temperature in Khalifa’s institute. With permission of the depicted persons (two of the authors of the present study)

Evaluation parameters

The temperature measurements in Khalifa’s institute were performed using a Flir i7 (Flir Systems, Wilsonville, USA; Figure 1b and c) infrared camera, which operates at a wavelength range from 7.5 to 13 μm. The focal distance of the IR lens is f = 6.8 mm. The temperature measurement range lies between -20°C and +250°C. Its accuracy lies at ±2% of the reading. Sensitivity is >0.1°C at 30°C, and the infrared resolution is 140 × 140 pixel. The system is ready for use in 15-20 seconds. [Figure 1a-c]

Procedure

Approximately 3 hours before starting the measurement, both legs were shaved. Thermal imaging was performed immediately before and immediately after manual therapy. Pictures were taken of the injured knee, the control knee (which did not receive any intervention), and of both legs together.

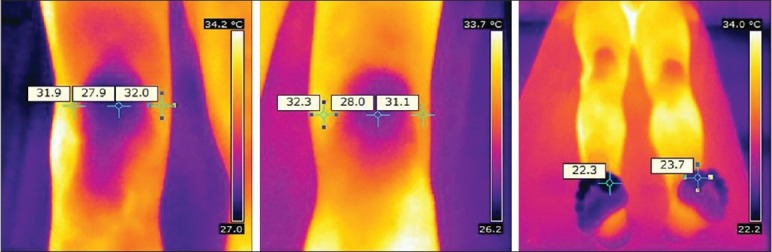

Pictures were analyzed using the software provided with the camera. The temperature was evaluated at three different spots: Anterolateral, frontal, and anteromedial. The measurement spot for assessing the temperature changes on the foot was located at the great toe (left and right, respectively; [Figure 2]).

Figure 2.

Thermal imaging. Regions of interest before manual Khalifa therapy. The different temperature measurement spots (altogether 8) are indicated

All patients were investigated in a supine position under the same conditions. The study was performed as a controlled study. We used the healthy knee for comparison, because it was not possible to investigate a control group (it would not be ethically correct to give the injured patients any treatment at all just for comparison; in contrast, a comparison with a group receiving surgery does not make sense, because it is an invasive procedure and not manual therapy). All temperature measurements were performed at both the knees and feet, the injured/treated one and the healthy/untreated one (control). To avoid potential technical recording artifacts, two thermal images were taken of each position. In addition, a “normal” photo was taken, and environmental temperature was also recorded before and after the treatment.

Statistical analysis

The temperature values of both legs were tested with paired t-test (SigmaPlot 12.0, Systat Software Inc., Chicago, USA). The level of significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

All the 10 patients completed the study, and the measurements could be performed without any technical problems.

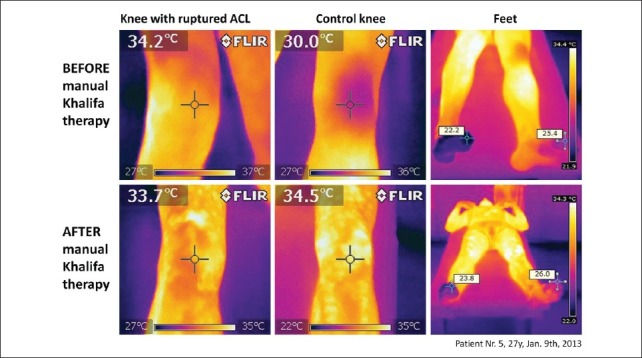

Figure 3 shows a typical example of a 27-year-old patient before and after manual Khalifa therapy [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Thermal images. Note the higher temperature at the injured knee compared with the control knee before treatment, whereas the temperature of the foot on the injured leg is initially lower than of that on the healthy leg (compare color of the toes)

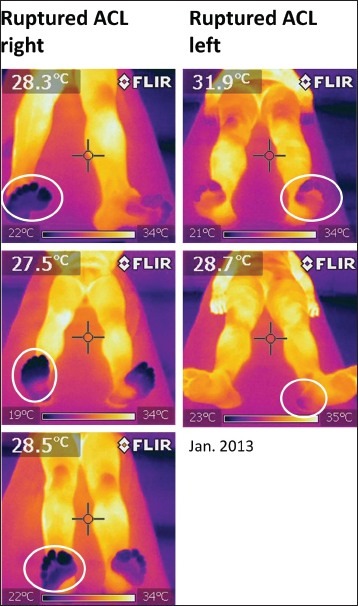

In Figure 4, thermal images of the feet of five different patients are shown. It is interesting that in the majority of the patients the temperature of the foot on the injured side was lower than on the healthy side [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Thermograms. The data of five patients, indicating the lower temperature of the foot on the injured side. In contrast, the temperature was higher at the injured knee than on the healthy knee [compare also Figure 3, Figure 5a and b]

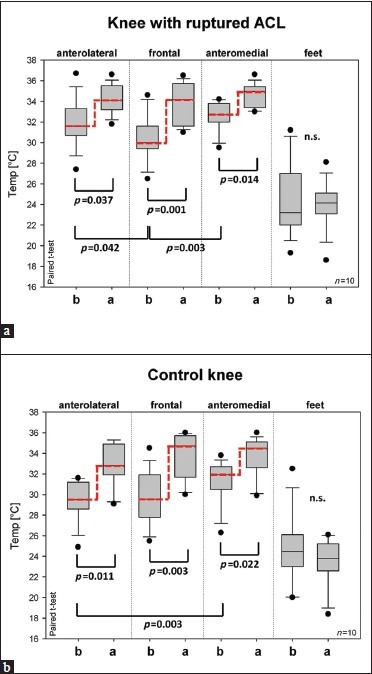

Figure 5a shows the increase of the surface temperature values after manual Khalifa therapy on the injured knee in all the 10 patients. Significant changes were found on the anterolateral (P = 0.037), frontal (P = 0.001), and anteromedial (P = 0.014) region of interest. No significant changes caused by the treatment were found on the feet.

Figure 5.

Changes of body surface temperature in 10 patients before and after manual therapy. Thermal data of injured (a) and control (b) knee. Ends of the boxes: 25th and 75th percentiles with a line at the median, error bars: 10th and 90th percentiles. b … before manual therapy; a … after manual therapy

In addition, it should be noted that there were also significant differences in the baseline values of the anterolateral and frontal (P = 0.042), and the frontal and anteromedial side (P = 0.003) of the injured knee. It was interesting that already the baseline values of the anterolateral side of the injured knee and those of the anterolateral side of the healthy (control) knee showed significant differences (P > 0.001). The same effect could also be seen on the anteromedial side, however, with a lower significance (P = 0.017). After treatment, there was still a significant difference on the anterolateral side (P = 0.022), but not on the anteromedial side.

The temperature changes on the healthy knee are presented in Figure 5b. Again, the different regions of interest in the area of the knee showed significant increases, whereas insignificant changes, even a slight decrease of the median, could be seen on the feet [Figure 5a and b].

In addition to the human body temperature, we also measured environmental temperature before and after treatment. There was a significant (P = 0.014) increase in room temperature (from 24.7 ± 0.8°C to 25.2 ± 0.9°C).

The function of all the 10 injured knees was restored after 60-90 minutes of manual therapy, and the patients were able to walk, run, jump [Figure 6], and bend their knees immediately after the end of the treatment. The functional parameters will be described in studies by other research groups [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Demonstration of the restoration of knee function. Knee function of a patient with a completely ruptured right ACL was completely restored immediately after manual Khalifa therapy

Discussion

The first scientific article concerning the acute effects of manual Khalifa therapy was published recently in the North American Journal of Medical Sciences[5] by our research group and describes first results from near-infrared spectroscopic measurements. The present article describes first results from thermal imaging.

It is well known in scientific literature that manual therapy induces changes on the human body surface, which can be measured by thermography.[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] Holey et al. reported, recently, that skin temperature showed significant increases immediately after connective tissue massage.[9] It is interesting that manual treatment can also induce significant temperature elevations in nonmassaged areas. Sefton et al.[10] in 2010 suggested dynamic infrared thermography as a useful tool to measure changes in peripheral blood flow noninvasively and even without contact in manual therapy research. The results of that study are in accordance with the results of the present study. After Khalifa therapy, we also found significant increases in temperature at the nontreated knee [Figure 5b]. This is not unusual and could be easily explained as physiological and pathophysiological changes of skin temperature also reflecting the function of the autonomic nervous system.[11] However, the changes of skin temperature after manual therapy are not uniform; this is also valid for acupuncture,[12] as shown by our research group. For example, Yeh et al.[13] reported a marked pain relief along with a reduction of skin temperature (about 1°C) of the affected shoulder in two patients after collateral traditional Chinese meridian acupressure therapy. In contrast to these investigations, the 10 patients, in this study, showed significant increases in temperature in the region of interest, both on the treated and also on the nontreated knee. However, it should be mentioned that the quality and quantity of the applied stimuli cannot be compared. Mohamed Khalifa uses only his hands to treat the patients. In literature, one can also find investigations concerning effects of manually assisted mechanical force on cutaneous temperature.[14] Again, using infrared cameras, differences in cutaneous temperature were found between the ipsi- and contralateral side after manually assisted mechanical force producing a chiropractic adjustment in the lumbar spine.[14] In all the studies, the primary reason for temperature changes is not described in detail; most probably it is an increase in microcirculation in deeper structures,[3] but a simple stimulus response or friction should also be taken into account. It should also be mentioned that few studies discussed the influence of environmental temperature. In this study, the room temperature was higher at the end of the treatment, probably because of the great physical effort of the therapist. However, we do not think that our measurement data were influenced by this, because the different regions of interest showed different responses; in one case, the median value even decreased [compare Figure 5b, feet].

A study was designed at the Air Force General Hospital in Beijing to analyze and explore the diagnostic significance of infrared thermography in patients with lumbar intervertebral disc protrusion.[15] Forty-five patients received conservative treatment (manual manipulation), and 65 were in the control group. Statistical analysis showed that the temperature difference between two sides was significantly higher in the patient group than in the control group. The analysis also showed that the temperature difference at the posterior femur area in the patients’ group was significantly correlated to the severity of clinical signs caused by nerve root irritation.[15]

In this study, we could not correlate the severity of the injury with the temperature differences because we had a very homogenous patient collective. It was, however, interesting to note that the patient with the highest degree of injury (complete rupture of the ACL and both collateral ligaments) also showed the highest temperature differences (on the knees and the feet).

In 1985 and 1989, researchers from Russia employed quantitative infrared thermography after manual therapy[16] and in the evaluation of the effectiveness of treating patients with cervical osteochondrosis by manual therapy.[17] In 1994, Walko and Janouschek used thermographic analysis in clinical osteopathic research.[18] Today, infrared thermography is increasingly applicable in sport and sport rehabilitation[19] It is a method that can be easily applied, and is fast and efficient in detecting different kinds of injuries[19] Therefore one can expect its increased use in the future.

Conclusion

The following conclusion can be drawn from this study:

After successful manual Khalifa therapy, the surface temperature values were significantly increased on both the knees (injured and control), with significances being higher on the knee with the ruptured ACL.

Baselines values of the anterolateral and anteromedial side of the injured knee were significantly different from those of the control knee. After treatment, there was still a significant difference on the anterolateral side.

There were no significant changes in temperature of the feet after treatment; however, it was interesting that the temperature of the feet before treatment was always lower on the injured side as compared with the control (healthy) side. The temperature in the region of the knee, in contrast, was always higher on the injured side.

Acknowledgements

This study is a part of the project “Interdisciplinary evaluation of acute effects of the Khalifa therapy in patients with ruptured anterior cruciate ligament in the knee” (project part: Biomedical engineering and analyses focused on NIRS - thermography and Doppler flowmetry). The study was supported by the Forschungsförderungsverein der Erkenntnisse von Mohamed Khalifa and Stronach Medical Group. It is part of the research area Sustainable Health Research at the Medical University of Graz. The authors are especially grateful to Mohamed Khalifa for the perfect cooperation and for treating the ten patients.

Especially we would like to thank Ms. Ingrid Gaischek, MSc (Medical University of Graz), for manuscript preparation and statistical analysis.

The authors would like to thank the following persons who participated in data acquisition in Hallein/Austria (in alphabetic order): Nathalie Alexander, MSc (scientist, Department of Sport Science and Kinesiology, University of Salzburg), Ismene Fertschai, PhD (scientist, Institute for Pathophysiology and Immunology, Medical University of Graz), Larissa Halb, MD (anesthesiologist, University Clinic of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Medical University of Graz), Andreas Kastner, MD (surgeon, General Hospital Linz), Eva Khalifa (organization management, Institute for Manual Medicine, Hallein), Bernhard Puswald, MSc (scientist, Institute of Health Technology and Prevention Research, Human Research), Frank Schreier, MSc (General Manager, Schreier Business Consulting), Hermann Schwameder, MD (Head of the Department of Sport Science and Kinesiology, University of Salzburg), Gerda Strutzenberger, PhD (Senior Scientist, Department of Sport Science and Kinesiology, University of Salzburg)

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Litscher G. Bioengineering assessment of acupuncture, part 1: Thermography. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;34:1–22. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v34.i1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litscher G. Infrared thermography fails to visualize stimulation-induced meridian-like structures. Biomed Eng Online. 2005;4:38. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litscher G, Ofner M, He W, Wang L, Gaischek I. Acupressure at the Meridian Acupoint Xiyangguan (GB33) Influences Near-Infrared Spectroscopic Parameters (Regional Oxygen Saturation) in Deeper Tissue of the Knee in Healthy Volunteers. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:370341. doi: 10.1155/2013/370341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niederführ G. Torn Ligaments? A Slipped Disc? Operations no longer necessary! Norderstedt: Books on Demand; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litscher G, Ofner M, Litscher D. Manual Khalifa therapy in patients with completely ruptured anterior cruciate ligament in the knee: First results from near-infrared spectroscopy. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:320–4. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.112477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vos WK, Bergveld P, Marani E. Low frequency changes in skin surface potentials by skin compression: Experimental results and theories. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2003;111:369–76. doi: 10.3109/13813450312331337621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang P, Su M, Liu Y, Hsu A, Yokota H. Knee loading dynamically alters intramedullary pressure in mouse femora. Bone. 2007;40:538–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bichler E. Mechanomyograms recorded during evoked contractions of single motor units in the rat medial gastrocnemius muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;83:310–9. doi: 10.1007/s004210000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holey LA, Dixon J, Selfe J. An exploratory thermographic investigation of the effects of connective tissue massage on autonomic function. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011;34:457–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sefton JM, Yarar C, Berry JW, Pascoe DD. Therapeutic massage of the neck and shoulders produces changes in peripheral blood flow when assessed with dynamic infrared thermography. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:723–32. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong I, Jun S, Park S, Jung S, Shin T, Yoon H. A research for evaluation on stress change via thermotherapy and massage. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2008;2008:4820–3. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4650292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litscher G, Wang L. Thermographic visualization of changes in peripheral perfusion during acupuncture. Biomed Tech (Berl) 1999;44:129–34. doi: 10.1515/bmte.1999.44.5.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeh CC, Ko SC, Huh BK, Kuo CP, Wu CT, Cherng CH, et al. Shoulder tip pain after laparoscopic surgery analgesia by collateral meridian acupressure (shiatsu) therapy: A report of 2 cases. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31:484–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy RA, Boucher JP, Comtois AS. Effects of a manually assisted mechanical force on cutaneous temperature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31:230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng T, Zhao P, Liang G. Diagnostic significance of topical image of infrared thermograph on the patient with lumbar intervertebral disc herniation-a comparative study on 45 patients and 65 normal control. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 1998;18:527–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diurianova I. Quantitative thermography after manual therapy. Vopr Kurortol Fizioter Lech Fiz Kult. 1985;1:35–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidorenko LV, Koval’ DE. IR thermography in the evaluation of the effectiveness of treating patients with cervical osteochondrosis by manual therapy. Ortop Travmatol Protez. 1989:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walko EJ, Janouschek C. Effects of osteopathic manipulative treatment in patients with cervicothoracic pain: Pilot study using thermography. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1994;94:135–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badza V, Jovanceviæ V, Fratriæ F, Rogliæ G, Sudarov N. Possibilities of thermovision application in sport and sport rehabilitation. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2012;69:904–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]