Abstract

The goal of the current article is to present the results of a randomized pilot investigation of a brief dynamic psychotherapy compared with treatment-as-usual (TAU) in the treatment of moderate-to-severe depression in the community mental health system. Forty patients seeking services for moderate-to-severe depression in the community mental health system were randomized to 12 weeks of psychotherapy, with either a community therapist trained in brief dynamic psychotherapy or a TAU therapist. Results indicated that blind judges could discriminate the dynamic sessions from the TAU sessions on adherence to dynamic interventions. The results indicate moderate-to-large effect sizes in favor of the dynamic psychotherapy over the TAU therapy in the treatment of depression. The Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale-24 showed that 50% of patients treated with dynamic therapy moved into a normative range compared with only 29% of patients treated with TAU.

Keywords: dynamic psychotherapy, effectiveness, adherence, depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a severe and disabling disorder afflicting approximately 17% of individuals across their lifetime (Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, & Walters, 2005) and has been ranked as the fourth greatest public health problem by the World Health Organization (Murray & Lopez, 1996). In addition to pharmacologic interventions, some specific psychotherapeutic interventions (e.g., cognitive therapy, interpersonal therapy) are considered effective in the treatment of MDD (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and have met the stringent criteria laid out by Chambless and Hollon (1998) for being included on the list of empirically supported psychotherapies.

There is also substantial empirical evidence supporting brief psychodynamic psychotherapies, based on exploring relationship issues that contribute to depressive symptomatology, as efficacious treatments for MDD. Reviews by Leichsenring (2001) and Fonagy, Roth, and Higgitt (2005) conclude that dynamically oriented psychotherapies are effective interventions for the treatment of a variety of mental disorders. Although the reviews by Leichsenring (2001) and Fonagy et al. (2005) also suggested that dynamic psychotherapies are effective treatments for MDD, the nature of the bulk of studies reviewed prevents concluding that observed effects for dynamic treatments are not due to nonspecific factors, the passage of time, or confounds such as the presence of different kinds of patients in different treatment groups (Chambless & Hollon, 1998).

The most recent meta-analysis of dynamic psychotherapy for depression (Driessen et al., 2010; Abbass & Driessen, 2010) specifically evaluated 23 studies of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression. This meta-analysis reports large effects for dynamic psychotherapy compared with control conditions and large pre–post effects indicating that dynamic psychotherapy results in significant decreases in depressive symptoms. There was a small effect for other psychotherapies to be more effective than dynamic psychotherapy at treatment termination, but this effect decreases substantially when only studies that used independent assessments of depression were examined. This is an important point because most of the comparison psychotherapies were cognitive–behavioral interventions that used the Beck Depression Inventory as part of the therapeutic intervention as well as including the Beck Depression Inventory as a primary outcome measure. The between-treatment effects at treatment termination are also not evident once only studies of individual therapies were aggregated. Finally, there was no advantage of other psychotherapies over dynamic psychotherapy at treatment follow-up. Like with previous reviews, this meta-analysis included a wide variety of studies, including uncontrolled studies, studies in which assessments weren't blind, and studies that did not specify treatment manuals. In addition, studies of group interventions and individual interventions were collapsed.

We recently reviewed the literature on the efficacy of dynamic psychotherapy to specifically evaluate whether any newer investigations met the strict criteria outlined by Chambless and Hollon (1998) for identifying empirically supported interventions (Connolly Gibbons, Crits-Christoph, & Hearon, 2008). Our review of the research literature evaluating the evidence for the efficacy of dynamically oriented interventions for MDD, identified two randomized controlled studies (de Jonghe, Kook, van Aalst, Dekker, & Peen, 2001; Burnand, Andreoli, Kolatte, Venturini, & Rosset, 2002) that meet the most stringent criteria outlined by Chambless and Hollon (1998) and provide compelling data for the efficacy of dynamic psychotherapy in the treatment of MDD, specifically, in the context of concurrent psychotropic medication usage. Although more high quality randomized controlled trials are needed to definitively add dynamic psychotherapy to the list of evidence-based psychotherapies for MDD, the body of evidence suggests that dynamic psychotherapy demonstrates effects comparable with other evidence-based psychotherapies for MDD.

Substantially less research has focused on the question of what psychotherapeutic interventions are effective in the real world of treatment delivery. To date, the evidence used to validate psychotherapies as empirically supported interventions has focused mainly on well controlled efficacy trials. Few effectiveness trials have been completed that demonstrate the effects of specific psychotherapies for specific disorders in real-world settings. One important setting for evaluating the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions is the community mental health system, a system funded by Medicaid and designed specifically to serve the poor and indigent. Community mental health centers are charged with the responsibility of providing quality treatment to patients in the public sector using limited funds and resources. Although the review of the effects of dynamic psychotherapy conducted by Driessen et al. (2010) included studies of community samples, none of these studies specifically evaluated the effectiveness of dynamic psychotherapy specifically in the community mental health setting using poor and indigent consumers.

Although many have suggested that outcomes in community mental health settings could be improved through the dissemination of empirically supported psychotherapeutic packages established through efficacy studies with outpatient populations treated mostly in university settings (Stirman, Crits-Christoph, & DeRubeis, 2004; Barlow, Levitt, & Bufka, 1999; Chorpita et al., 2002; Henggeler, Schoenwald, & Pickrel, 1995), such efforts face a variety of challenges, including poor response rates to empirically supported psychotherapies in community mental health settings, the cost of training community therapists in these new methods, and resistance from community therapists to adopt new approaches that are discrepant from their preferred style of therapy. A survey of therapists delivering services in community mental health centers (Connolly Gibbons, Crits-Christoph, Narducci, & Schamberger, 2004) indicated that the majority of therapists believed that the existing treatment manuals for empirically supported treatments were too rigid and not relevant to the types of patients treated in the community mental health setting. However, therapists were extremely interested in obtaining further psychotherapeutic training. Further, therapists working in the community mental health setting indicated that they believed relationship problems to be an important reason for current symptoms, and they felt focusing on relationship issues within psychotherapy would be important to alleviate depressive symptoms.

The aforementioned considerations provided the impetus for our modification of an existing manualized dynamic psychotherapy, Supportive Expressive (SE; Luborsky, 1984) Psychotherapy, for use in the community mental health system to treat moderate-to-severe depression. There are many reasons for conducting effectiveness trials of short-term dynamic psychotherapy for MDD in the community mental health system. First, there is substantial evidence based on efficacy trials that short-term dynamic psychotherapy is an effective intervention with effects comparable with other psychotherapeutic interventions. Next, our own survey of therapists working in this setting indicates that the theory and techniques of short-term dynamic psychotherapy are consistent with their values. Finally, there is a substantial research literature specifically supporting the theoretical mechanisms of change in SE psychotherapy (Connolly, Crits-Christoph, Shelton, et al., 1999; Connolly Gibbons et al., 2009). Like many short-term dynamic approaches, SE psychotherapy is based on the theory that interpretations of impairing relationship conflicts allow the patient to gain understanding of these conflicts that leads to symptom alleviation. Research has demonstrated that changes in self-understanding are specific to dynamically oriented psychotherapies (Connolly, Crits-Christoph, Shelton, et al., 1999; Connolly Gibbons et al., 2009) and that such changes predict symptom change, including subsequent symptom course across treatment follow-up (Connolly Gibbons et al., 2009).

The goal of the current manuscript is to present the results of a randomized pilot investigation of SE psychotherapy, specifically modified to meet the demand of the community mental health system, as compared with treatment-as-usual (TAU) for moderate-to-severe depression treated in the community mental health system. Our goals were (a) to describe the intervention as it was adapted specifically for use in the community mental health system, (b) to provide preliminary estimates of the effects of SE psychotherapy compared with TAU on symptom decrease, clinically meaningful change, and treatment retention, (c) to evaluate whether the SE psychotherapy could be discriminated from the TAU treatment on adherence to supportive and expressive techniques, and (d) to evaluate whether use of expressive techniques to address maladaptive interpersonal patterns predicted symptom course.

We hypothesized that SE psychotherapy would result in greater symptom change across 12 weeks of psychotherapy and greater retention in treatment than the psychotherapeutic TAU for depression in the community mental health setting. We further hypothesized that the modified SE psychotherapy could be discriminated from the TAU intervention by blind judges on adherence to expressive relationship–focused techniques. Finally, we hypothesized that adherence to expressive techniques would be predictive of symptom course across psychotherapy.

Method

We conducted a program of treatment development to develop and evaluate the potential of SE psychotherapy in the treatment of moderate-to-severe depression in the community mental health setting. We developed an addendum treatment manual in conjunction with community therapists, conducted training workshops teaching SE psychotherapy in the community clinic, provided intense group supervision to community therapists implementing the treatment with training cases in the community setting, and conducted a pilot randomized trial to compare the effectiveness of SE dynamic psychotherapy with TAU in the treatment of moderate-to-severe depression in the community mental health setting.

Setting: Northwestern Human Services

We partnered with Northwestern Human Services (NHS) to conduct this research program. NHS is a private, nonprofit, community-based corporation that provides mental health, mental retardation, and substance abuse treatment services to children and adults throughout Pennsylvania, primarily serving the publicly funded consumer. The current investigation was conducted at one NHS site in Philadelphia that serves approximately 2100 individuals per year in the outpatient clinic. The population was primarily adult and predominantly African American. Nearly all of the consumers receiving services at NHS are low-income individuals receiving some form of public assistance or other support for medical and behavioral health services. At NHS, the majority of outpatient consumers receive pharmacological management with about one half also participating in psychotherapy. While a formal chart review of the patients in the current study was not conducted with regard to concurrent pharmacological treatment, consistent with the NHS program it is likely that many of the patients in this study were also prescribed psychiatric medication in addition to psychotherapy.

Participants

Psychotherapists

NHS employs approximately 40 master's level therapists, both salaried and fee-for-service, as well as a number of graduate student interns. Medical coverage is provided by three to four full-time and two to three part-time psychiatrists. Eight therapists working at NHS were recruited through advertisement for the current project. Five therapists were recruited specifically for training in the community-friendly SE package and participated in a training workshop and supervised training cases. Therapists were recruited through an advertisement placed in therapist mailboxes. Interested therapists met with the principal investigator of the project and were included in the project if they were already treating adult outpatients at the center and planned to remain employed by the center for at least one year. Once the training phase was complete for the SE treatment condition, three additional therapists were recruited via advertisement at the center to specifically participate as TAU therapists. All therapists had a master's degree in a mental health field. All therapists delivered services as part of this research project at the community site to community consumers. All therapists received a $100 honorarium for every two cases they treated as part of the study and received $25 for attendance at the regular supervision sessions. Therapists in the SE condition received $200 for participation in the initial full day training workshop, and TAU therapists received $50 for the initial orientation meeting.

Patients

All patients who participated in this project were recruited from those seeking outpatient services at NHS. We used a recruitment procedure to identify potential candidates for research without placing additional burden on the community intake clinicians or on treatment consumers. Because it was not feasible to conduct a structured clinical diagnostic interview in the community setting due to financial and time constraints on both community clinicians and consumers, we designed a recruitment procedure to build on the community clinic's established assessment system, supplemented with minimal additional research assessments for the purpose of specifying the sample. We implemented a brief self-report depressive symptom measure, the Quick Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS; Rush et al., 2003), to identify patients with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms, who could be potential candidates for our research program. Studies have shown that a score of 11 or greater on the QIDS is sensitive to a score of 14 or above on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD; Hamilton, 1960).

The intake clinician at NHS examined the QIDS completed by the patient in the waiting area and determined whether the patient was interested in hearing more about the research program. Any patient who scored 11 or above on the QIDS and indicated that he or she was interested in hearing more about the research program was identified by the intake clinician as potentially eligible for the study. The intake clinician completed a brief checklist to identify whether the patient met any of our exclusion criteria and then proceeded with the normal clinic intake procedure. The community intake clinician provided the research team with the names and phone numbers of patients who scored 11 or above on the QIDS, were interested in hearing more about the research, were not referred out for immediate substance or alcohol treatment, were not acutely suicidal, and did not meet criteria for bipolar disorder or any psychotic disorder.

A member of the research staff then contacted potential participants, described the research study, completed a brief telephone screen, and scheduled an in-person baseline evaluation at the patient's convenience at the community mental health center. At the baseline evaluation, a bachelor's level research assistant completed the informed consent with the patient and administered the HAMD (Hamilton, 1960). Any patient who scored ≥14 on the HAMD was randomized to a study therapist and scheduled for his or her first therapy appointment. Any patient who did not meet the HAMD cutoff for inclusion in the research protocol was immediately returned to the original agency intake clinician for assignment to a community clinician.

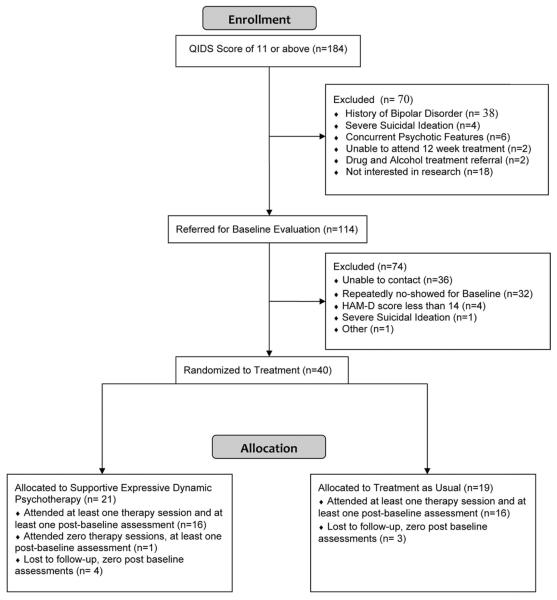

In all, 184 patients attending an intake at the community mental health center met the QIDS cutoff score indicating moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms (Figure 1). Of the 184 patients, 114 were referred to the research team for evaluation and 70 were excluded by the center intake clinician. Of those excluded by the intake clinician, 38 patients were excluded based on a history of bipolar disorder, 4 were actively suicidal and required referral for more intensive assessment and treatment, 6 had concurrent psychotic features, 2 were not available for the 12 weeks of study participation, two required immediate referral to a partial program or drug and alcohol program, and 18 were not interested in referral to research. Of the 114 patients referred to the research team, 36 were not able to be contacted, 32 repeatedly did not show for baseline assessment, 1 was excluded at baseline because she was inadvertently assigned to a nonstudy therapist at the center before the baseline, 4 were excluded at baseline because they did not have greater than a 14 on the HAMD, and 1 was excluded because the subject required immediate referral back to the clinic for suicidal plan, and 40 were randomized to either the SE psychotherapy or TAU. Of the 21 patients randomized to the SE psychotherapy, 16 attended at least one session of psychotherapy and completed at least one postbaseline assessment. Of the 19 patients randomized to TAU, 16 patients attended at least one session and completed at least one postbaseline assessment. One patient in the TAU condition was excluded from analyses because it was discovered that the patient was receiving concurrent psychiatric care and psychotherapy at another site.

Figure 1.

Supportive expressive dynamic psychotherapy versus treatment as usual recruitment flow diagram.

Because our recruitment procedures cast a wide net to minimize research burden on agency staff, we started by evaluating a large number of consumers who were not seeking services at the agency for the treatment of depression. Rather, our initial screening identified all consumers who self-reported any depressive symptoms, including many consumers who were seeking services for psychotic disorders and substance use. Of the consumers excluded from the research by the community intake clinician, most were bipolar, suicidal, or had psychotic symptoms and would not be receiving weekly treatment by the community agency for unipolar depression. Of the patients referred to the research team by the agency intake clinician, most patients who did not make it into the research protocol could not be contacted or repeatedly did not show for appointments. This no show rate for the research is consistent with the no show rate experienced by the community agency treating this population. Therefore, the final sample included in this pilot investigation is representative of the patients that actually receive outpatient psychotherapy for moderate-to-severe depression in the community mental health system.

Treatment

The psychotherapy included in this project consisted of 12 weekly sessions of either our SE dynamic psychotherapy or TAU delivered by community clinicians at the community center. All sessions were scheduled by the patient and therapist, as is typical of therapy delivered at the community mental health agency. All sessions lasted 60 minutes, as is typical of outpatient sessions delivered in the community setting.

SE dynamic psychotherapy for depression in the community mental health setting

A draft of the SE psychotherapy manual for the treatment of depression in the community mental health setting was prepared by the first author of this article and was adapted and modified across a treatment development phase in which therapists working in a community mental health center were trained and intensely supervised. The SE psychotherapy was adapted specifically to meet the needs of therapists and consumers in the community mental health system. We worked across training cases to expand how the supportive and expressive techniques could be used with this population and added additional components to the model to help therapists meet the diverse needs of clients seeking treatment in the community mental health setting.

Expressive relationship–focused component

We adapted the techniques for formulating and interpreting maladaptive relationship patterns first described as part of the supportive-expressive dynamic psychotherapy model (Luborsky, 1984). First, therapists were trained to focus patients to tell 5 to 10 specific stories about problematic interactions the patient had recently with important people in their lives. For each story, therapists explored with the patient what he or she really wanted or needed from the other person, how he or she saw the other person as acting toward him/her, and how he or she responded to the other person. Across stories, the therapist and patient worked to try to understand the patterns that were repetitive across their experiences that were causing the most problems for the patient in his or her current world. Therapists helped patients explore how their current interpersonal responses, although understandable given their past relationship experiences, were incompatible with what they truly wanted from the other people in their lives.

Supportive alliance building component

The alliance building component of this SE package for the treatment of depression in the community mental health setting included additional techniques to help the therapist engage the patient in the therapeutic work. These techniques were adapted from a manual used in an investigation by Crits-Christoph, et al (2006) that examined whether therapists could learn to improve their alliance with patients. We modified and operationalized these alliance fostering techniques specifically to meet the needs of community therapists. Agreement on goals of treatment was accomplished by establishing explicit treatment goals with the patient early in treatment and reviewing these goals regularly. Agreement on the tasks of therapy was fostered through an explicit socialization of the patient during the first two sessions of treatment. The therapist and patient openly discussed the tasks of each participant in the therapeutic process and reviewed the patient's thoughts and feelings about this process.

To build the therapeutic relationship, the therapist reviewed these tasks regularly throughout the treatment to make sure the patient felt comfortable with the treatment progress. Finally, the therapist–patient bond was fostered through a number of techniques, including (a) regular examination of the patient's motivation for treatment, (b) regular monitoring of the patient's involvement in the therapeutic process, (c) maintenance of an empathic stance indicated by use of “we” in discussions of therapy tasks and goals, (d) use of a conversational style, (e) repeated acknowledgment that the patient is being heard, (f) use of facial expressions to exhibit interest and respect, (g) regularly noting any positive change accomplished by the patient, and (h) high frequency use of reflective clarifications. In addition, ruptures to the bond were monitored as evidenced by verbal and nonverbal distancing by the patient. In cases of alliance rupture, the therapist was trained to help the patient express his or her feelings and to provide an accepting climate for such discussion.

Socialization-focused component

This SE psychotherapy started by providing a strong socialization component to motivate clients to make a commitment to trying 12 sessions of psychotherapy as well as enhancing their expectations of what therapy has to offer. Multiple psychotherapeutic packages, including Luborsky's (1984) supportive-expressive psychotherapy, have included guidelines for socializing patients to psychotherapy. Luborsky (1984) identified four steps in the socialization process: (a) setting the goals for treatment, (b) explaining the treatment process to the patient, (c) making practical arrangements for treatment such as scheduling the time and length of sessions, and (d) explaining what the therapist's role will be. Book (1997) expanded on the techniques for socializing patients to short-term psychotherapy. He incorporated (a) an introduction to review why the patient has been referred for psychotherapy, (b) the presentation of the relationship model, (c) education regarding how therapy can be helpful, (d) an explanation of the need to focus psychotherapy, and (e) a detailed discussion of the patient's and therapist's tasks in treatment. Given the high attrition rate in the community mental health system, we implemented an explicit socialization interview, adapted from the guidelines discussed by Luborsky (1984) and Book (1997), in the first session. Our goal was to provide overt “ground rules” for treatment, explore any patient doubts about the usefulness of treatment, explain the therapeutic focus on relationship patterns, and motivate the patient to believe that change is possible.

Education-focused component

Our community therapists believed that it was important to integrate educational techniques into the SE package to be successful in this community setting. There is a comprehensive research literature demonstrating the efficacy of psychoeducational interventions in the treatment of schizophrenia (McFarlane, Dixon, Lukens, & Lucksted, 2003) and bipolar disorder (Colom et al., 2003; Reinares et al., 2008). Reviews of these family psychoeducational programs (Murray-Swank & Dixon, 2004; Miklowitz & Hooley, 1998) describe the main interventions as consisting of techniques to empower the patient to be an active participant in his or her treatment, to increase awareness of the nature of the disorder and available treatments, to focus the patient on the necessity to adhere to the treatment, and techniques to increase knowledge and coping skills. Problem-solving psychotherapies, focused on helping patients identify problems and implement solutions, have also been developed and evaluated in the treatment of depressive symptoms. A comprehensive review of the literature on problem-solving therapy (Gellis & Kenaley, 2008) indicates mixed results for problem-solving therapy alone in the treatment of depression, but it suggests that problem-solving psychotherapy in conjunction with antidepressant medication treatment is effective in the treatment of depression.

Building on the psychoeducational literature, as well as the literature on problem-solving therapy, we developed the educational component to help community therapists address the educational needs of their patients within the context of SE dynamic psychotherapy for depression in the community mental health setting. The therapist was instructed to help the patient attain the necessary information needed to avoid further life crises while maintaining a focus on the treatment of depressive symptoms. The therapist was encouraged to acknowledge that these legal, medical, and family crises were real and in need of immediate attention without detracting from the discussion of relationship conflicts. During the first few sessions, the therapist focused on those life factors that were likely to inhibit the client's ability to complete a course of psychotherapy for depression. The therapist worked with the patient to figure out how to contact the legal, medical, and social services necessary to deal with these life problems. Once current life stressors were stabilized, the therapists were trained to take each life stressor and return to an exploration of the relationship patterns that contributed to the problems.

Cultural sensitivity component

A cultural sensitivity component was included to provide guidance to help therapists explore and work with cultural influences on the therapeutic work. Cultural sensitivity is a concept that has become increasingly important in psychotherapy research and practice. In response to the growing ethnic minority population and the increased demand for psychological services among minority clients, many therapists and researchers have attempted to identify competencies and guidelines for providing culturally sensitive approaches to treatment. Our review of the literature suggests four broad concepts of cultural sensitivity that can aid therapists in modifying therapies to specifically address culture and its role in the therapeutic process (Arredondo et al., 1996; Lopez et al., 1989; Sue, 1998; Sue et al., 1982; Sue & Sue, 1990; Zayas, Torres, Malcolm, & DesRosiers, 1996).

First, it is crucial for therapists to have an awareness of the influence of their own cultural background and how their own feelings, values, and beliefs about ethnic minorities can impact treatment. Second, it is also important that therapists are familiar with the ethnic minority group that they will be treating in therapy. Therapists should develop some level of understanding about the client's culture, norms, values, family, social structure, and gender roles. Third, because it is likely that therapists and ethnic minority clients may differ in terms of life experiences, therapists should acknowledge and explore those existing differences. Through exploration, therapists can increase their awareness of the influence of cultural factors while also developing a level of comfort and respect for the differences that are present. The last component emphasizes therapists' abilities to distinguish between what is normal versus impaired within the client's ethnocultural context. We adapted the manual by White, Connolly Gibbons, and Schamberger (2006) that operationalizes techniques for addressing these components of cultural sensitivity within SE psychotherapy.

Treatment-as-usual

Therapists in the TAU condition were asked to deliver 12 sessions of psychotherapy, using the approach they would normally use to target MDD in a community mental health setting. In our survey of therapists' training and beliefs (Connolly Gibbons et al., 2004), the therapists reported very little previous exposure to empirically supported psychotherapies. The therapists reported that they used some cognitive- and relationship-focused interventions, but few therapists reported any formal training in specific evidence-based techniques.

Clinical Supervision

Five therapists were trained in our SE psychotherapy package by participating in a 1-day workshop to introduce them to the treatment components, including a review of the background and main techniques of each component. The therapists then treated three training cases each with 12 sessions of the treatment while receiving one hour of weekly group supervision conducted by the first author of this article. We worked in conjunction with the community therapists to modify the treatment manual to best meet the training needs of therapists working in the community. We worked together to specify how the treatment components could be implemented flexibly in the community setting. We further developed the intervention techniques, including examples provided in the treatment manual, across the training cases.

During the randomized trial, all therapists received one hour of monthly group supervision across the two years of the randomized phase. The therapists in the SE condition met in a group format monthly with the first author of this article. To equate the treatment conditions on supervision time, the TAU therapists also met monthly for peer supervision. The therapists in the TAU condition were instructed to use the supervision hour to discuss their current research cases and provide each other with peer feedback on strategies for working with their cases.

Outcome Assessments

Overview

The assessment battery was designed to put the minimum burden on community consumers of service for depression. All patients completed the QIDS at intake to the clinic to screen them for eligibility for referral to the study. The HAMD and a brief self-report symptom inventory, the Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-24; Eisen, Normand, Belanger, Spiro, & Esch, 2004), was completed at baseline and at monthly intervals during the treatment. The BASIS-24 was also completed before each session. The QIDS is a 16-item self-report measure designed to assess the severity of depressive symptoms using the criterion symptoms designated by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition. The QIDS demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = .86) in patients with chronic major depression (Rush et al., 2003). In the same sample, total scores on the QIDS were highly correlated (r = .81) with the 17-item HAMD. All assessments were scheduled at the patient's convenience (often in conjunction with a scheduled psychotherapy appointment) and were conducted at the community agency. Patients were reimbursed $25 for completing the baseline assessment, $30 for the monthly assessments, and $5 at each treatment session for completion of the BASIS-24. All payments were made in the form of gift cards to local convenience stores.

The HAMD (Hamilton, 1960)

The HAMD is a widely used inventory for evaluating the severity of common symptoms of depression. The 24-item version of the HAMD was completed by trained bachelor's level research assistants using the Structured Interview Guide to enhance reliability (Williams, 1988). Using the structured interview guide, Williams reported good interjudge reliability for a test–retest assessment of the 17-item score (ρI = .81).

The BASIS-24 (Eisen et al., 2004)

All patients completed the BASIS-24 before each outpatient session as part of routine NHS clinical practice. The BASIS-24 is a 24-item, self-report inventory designed to measure mental health status from the consumer's point of view. The items cover six domains, including depression/functioning, interpersonal relationships, psychotic symptoms, alcohol/drug use, and emotional lability. The measure has demonstrated acceptable test–retest reliability and internal consistency as well as good construct and discriminate validity (Eisen et al., 2004). Further studies have supported the reliability, concurrent validity, and sensitivity of the BASIS-24 in Whites, African Americans, and Latinos (Eisen, Gerene, Ranganathan, Esch, & Idieulla, 2006).

Assessment of Adherence/Competence

We adapted an adherence scale for the SE treatment from the Penn Adherence/Competence Scale for SE Dynamic Psychotherapy (PACS-SE) developed by Barber and Crits-Christoph (1996). The original PACS-SE consists of 45 items designed to assess the basic supportive and expressive techniques of SE psychotherapy. Each item is rated for adherence on a 7-point Likert scale designed to assess the frequency of the techniques ranging from “not at all” to “very much.” For the current project, we selected and modified 6 items from the supportive interventions subscale and 7 items from the expressive interventions subscale to represent the techniques targeted in this modified SE psychotherapy for depression in the community mental health settings. A copy of the adherence measure is provided in the appendix.

Three bachelors level research assistants, blind to the study hypotheses and treatment conditions, completed the adherence ratings. Session 3, or the next closest session, was scored for each patient. The judges were first trained by the first author of this manuscript. The judges first participated in a meeting to review the SE model of psychotherapy and to review each item of the adherence measure. The judges and trainer then each independently rated a practice session by listening to the complete session and completing each of the 14 adherence items. The judges and trainer then met to review ratings. This procedure was then repeated with a second training session. The judges then independently scored 50% of the patient sessions, met for one recalibration session to review ratings with the trainer, and then independently completed the rest of the patient sessions. All three judges independently rated all sessions.

Data Analysis

All analyses were based on a modified intent-to-treat sample including all patients randomized to treatment who attended at least one treatment session and one postbaseline assessment. The primary outcome measures for the current analyses included the BASIS-24 total score, the BASIS-24 depression subscale score, and the HAMD 17-item score. We evaluated symptom change across the treatment conditions using hierarchical linear models. Each model was computed assuming both a random intercept and random slope. For the BASIS-24 models, all available data from sessions and monthly assessments was included. For analysis of the HAMD, all available data from the baseline, month 1, month 2, and month 3 assessments was included. There was a window of plus or minus two weeks for the collection of monthly assessment data. There were cases in which the last monthly assessment occurred beyond the 2-week window, and there were session measures collected beyond the month-3 assessment. The current analyses excluded assessment data collected outside the 2-week window of the month-3 assessment in order to ensure that the slope estimates were not distorted. Time was operationalized as the log of the number of days from treatment baseline to each assessment.

All analyses included age, marital status, race, and gender as covariates. Marital status was included as a dichotomous variable representing those who were married or cohabiting versus not, and race represented Caucasians versus African Americans. Due to the small sample size for this pilot investigation, we also computed effect sizes comparing the slopes of change across the two treatment groups using Cohen's d.

To evaluate clinically meaningful change, we computed the percent of patients in each treatment group who achieved reliable change, the percent who moved from a dysfunctional range to a normative range, and the percent who had both reliable change and moved into a normative range as measured by the HAMD and the BASIS-24 (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). For the computation of reliable change, the reliability of each measure was estimated from the endpoint ratings since intake ratings were specifically restricted by our inclusion criteria. Movement into the normative range was computed using criterion C described by Jacobson and Truax (1991). Computations for the HAMD were based on the normative mean and standard deviation estimated by Grundy, Lambert, and Grundy (1996). Computations for the BASIS-24 were based on the normative mean and standard deviation provided by the Mental Health Services Evaluation Department of McLean Hospital (S. Eisen, personal communication, January 16, 2012). We also report the percentage of patients in each treatment group demonstrating clinical deterioration, defined as patients whose scores on each measure increased by the reliable change index.

Given the small sample size of this pilot investigation, exploratory analyses were conducted as a preliminary step in examining the relation between adherence to techniques of SE psychotherapy and treatment outcome. Hierarchical linear models were used to predict symptom measures from adherence measures, demographic variables, the log of the number of days from baseline to each assessment, and the interaction of the adherence measure and the log of the number of days. Adherence to supportive techniques and adherence to expressive techniques were evaluated in separate analyses. We examined the significance of the adherence by time interaction in each analysis to assess the relation between adherence and symptom slope. To derive an effect size for the relation between adherence and change in symptoms, we calculated a partial r using the Cohen's d to r transformation derived from the Cohen's d estimate from the F test for mixed effects model. Cohen's d is calculated as, with the d to r transformation as , where F is the F test statistic for the test for differences in slopes dependent on adherence in a multilevel design (Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1991; Verbeke & Molenberghs, 2000).

Results

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1 for both the randomized sample and the modified intent-to-treat sample included in all analyses. Eighty-seven percent of patients were female, 19% were married or cohabiting, and 84% were African American; the mean age was 41 years (SD = 9.9). Patients had on average 11.8 years of education (SD = 2.0), and 65% were unemployed.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Randomized sample |

Intent-to-treat sample |

Intent-to-treat SE |

Intent-to-treat TAU |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n = 40 | n = 31 | n = 16 | n = 15 |

| Gender, % | ||||

| Female | 90 | 87 | 93 | 80 |

| Marital status, % | ||||

| Single | 46.2 | 48.4 | 37.5 | 60.0 |

| Married/cohabitating | 20.5 | 19.4 | 25.0 | 13.3 |

| Divorced | 23.1 | 22.6 | 31.3 | 13.3 |

| Separated | 5.1 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 13.3 |

| Widowed | 5.1 | 3.2 | 6.3 | 0.0 |

| Ethnicity, % | ||||

| Hispanics | 7.7 | 9.7 | 12.5 | 6.7 |

| Race, % | ||||

| Black | 84.6 | 83.9 | 75.0 | 93.3 |

| Caucasian | 15.4 | 16.1 | 25.0 | 6.7 |

| Employment, % | ||||

| Employed full-time | 10.5 | 6.5 | 12.5 | 0.0 |

| Employed part-time | 13.2 | 16.1 | 25.0 | 6.7 |

| Homemaker | 7.9 | 9.7 | 12.5 | 6.7 |

| Unemployed | 65.8 | 64.5 | 43.7 | 86.6 |

| Student | 2.6 | 3.2 | 6.3 | 0.0 |

| Education, years M (SD) | 11.90 (1.86) | 11.81 (2.04) | 11.88 (2.50) | 11.73 (1.49) |

| Age, years M (SD) | 40.79 (10.35) | 41.23 (9.92) | 41.44 (8.90) | 41.00 (11.23) |

Note. SE = supportive expressive psychotherapy condition; TAU = treatment-as-usual condition.

Patients were included in this trial if they received a score of 11 or above on the QIDS and a score of 14 or above on the HAMD 17-item score. Descriptive statistics for all measures are included for each assessment point by treatment in Table 2. The average score on the HAMD across the sample at baseline was 21 (SD = 4.4). Primary diagnoses based on the community clinicians' intake evaluation included MDD (74%), depressive disorder not otherwise specified (10%), posttraumatic stress disorder (10%), adjustment disorder (3%), and dysthymic disorder (3%).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for All Assessments by Treatment by Time Point

| Assessment | Baseline | Session 3 | Month 1 | Month 2 | Month 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASIS-24 depression | |||||

| SE, M (SD) | 2.74 (0.85) | — | 2.05 (1.06) | 2.08 (0.96) | 1.97 (0.68) |

| n | 16 | — | 15 | 14 | 16 |

| TAU, M (SD) | 2.28 (0.74) | — | 1.89 (0.99) | 1.99 (1.12) | 1.86 (0.94) |

| n | 15 | — | 14 | 13 | 13 |

| BASIS-24 total Score | |||||

| SE, M (SD) | 1.47 (0.40) | — | 1.24 (0.47) | 1.27 (0.50) | 1.25 (0.48) |

| n | 16 | — | 15 | 14 | 16 |

| TAU, M (SD) | 1.46 (0.34) | — | 1.32 (0.45) | 1.45 (0.63) | 1.30 (0.58) |

| n | 15 | — | 14 | 13 | 13 |

| HAMD, 17 item | |||||

| SE, M (SD) | 23.0 (4.73) | — | 17.0 (5.69) | 16.6 (6.01) | 16.6 (6.50) |

| n | 16 | — | 15 | 14 | 16 |

| TAU, M (SD) | 19.7 (3.40) | — | 17.5 (6.37) | 15.31 (6.45) | 15.8 (7.62) |

| n | 15 | — | 14 | 13 | 13 |

| Adherence supportive | |||||

| SE, M (SD) | — | 3.57 (0.73) | — | — | — |

| n | — | 16 | — | — | — |

| TAU, M (SD) | — | 3.82 (0.56) | — | — | — |

| n | — | 14 | — | — | — |

| Adherence expressive | |||||

| SE, M (SD) | — | 2.60 (0.68) | — | — | — |

| n | — | 16 | — | — | — |

| TAU, M (SD) | — | 1.77 (0.67) | — | — | — |

| n | — | 14 | — | — | — |

Note. SE = supportive expressive psychotherapy condition; TAU = treatment-as-usual condition.

Symptom Change Across Treatment

The results of the hierarchical linear models are presented in Table 3. There was statistically significant change over time on the HAMD (f(1,38.17) = 23.26, p < .001) and the BASIS-24 depression score (f(1,41.17) = 16.45, p < .001) but no significant change on the BASIS-24 total score (f(1,33.88) = 1.76, p = .193). There was also a significant interaction between treatment and time for symptom change as measured by the BASIS-24 depression score (f(1,41.20) = 10.54, p = .002) and a trend for a significant interaction on the HAMD (f(1,38.23) = 2.99, p = .092) and BASIS-24 total score (f(1,33.87) = 3.36, p = .076) indicating greater symptom change across the SE condition compared with the TAU condition. Effect sizes demonstrated a large benefit for the SE psychotherapy versus the TAU group on the BASIS-24 depression score (Cohen's d = 2.02), the BASIS-24 total score (Cohen's d = .83) and the HAMD (d = 1.16).

Table 3.

Hierarchical Linear Models Assessing the Relation of Treatment Group to Slope of Symptom Change, Controlling for Demographic Variables

| Factor | BASIS-24 depression | BASIS-24 total | HAMD 17 item |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | |||

| Gender | F(1,24.29) = 9.15, p = .006 | F(1,25.00) = 5.15, p = .032 | F(1,22.96) = 6.49, p = .018 |

| Age | F(1,22.33) = 0.01, p = .976 | F(1,24.99)= 1.12, p = .299 | F(1,23.16) = 0.58, p = .455 |

| Marital | F(1,25.10) = 2.68, p = .114 | F(1,25.64) = 0.16, p = .695 | F(1,23.10) = 0.27, p = .607 |

| Race | F(1,24.11) = 6.69, p = .016 | F(1,24.87) = 3.45, p = .076 | F(1,23.94) = 3.83, p = .062 |

| Main effects | |||

| Treatment | F(1,36.90) = 0.76, p = .389 | F(1,30.42) = 0.35, p = .557 | F(1,34.35) = 0.80, p = .377 |

| Log of number of days | F(1,41.17) = 16.45, p < .001 | F(1,33.88) = 1.76, p = .193 | F(1,38.17) = 23.26, p < .001 |

| Interaction effects | |||

| Treatment × days | F(1,41.20) = 10.54, p = .002 | F(1,33.87) = 3.36, p = .076 | F(1,38.23) = 2.99, p = .092 |

Clinically Meaningful Change

Based on the criterion outlined by Jacobson and Truax (1991), an alpha coefficient of .75 with an intake standard deviation of 4.44 for the HAMD results in a reliable change index of 6.16 points. As measured by the HAMD, 50% of patients treated in SE psychotherapy and 21% of patients treated with TAU had reliable change (χ2(1) = 2.63, p = .105). Forty-four percent of patients treated in SE and 36% of TAU patients moved from a dysfunctional range to a normative range across treatment (χ2(1) = 0.20, p = .654), whereas 31% of SE patients and 21% of TAU patients demonstrated both reliable change and movement into the normative range (χ2(1) = 0.37, p = .544). No patients in either treatment condition demonstrated clinical deterioration as measured by the HAMD.

As measured by the BASIS-24, 31% of patients treated in SE psychotherapy and 14% of patients treated with TAU had reliable change (χ2(1) = 1.20, p = .273). Fifty percent of patients treated in SE and 29% of TAU patient moved from a dysfunctional range to a normative range across treatment (χ2(1) = 1.43, p = .232), whereas 31% of SE patients and 14% of TAU patients demonstrated both reliable change and moved into a normative range (χ2(1) = 1.20, p = .273). No patients in SE and 7% of TAU patients demonstrated clinical deterioration as measured by the BASIS-24 (χ2(1) = 1.18, p = .277).

Comparison of Treatment Retention

There were no significant differences between treatments in the number of sessions attended, t(30) = 1.19, p = .244. Patients in the SE psychotherapy condition attended on average 7.4 (SD = 2.5) sessions of treatment compared with 6.6 (SD = 2.7) sessions in the TAU condition. The median number of sessions attended by each treatment group was 7.0, and the modal number of sessions attended by both treatments was 5.0. Attrition from treatment was similar across both treatment groups. The minimum number of sessions was 3 in the SE psychotherapy condition and 2 in the TAU group. In the SE condition, 6.25% of patients attended only 2 to 3 sessions, 56.25% attended between 5 and 8 sessions, and 37.50% attended between 9 and 12 sessions. In the TAU condition, 13.33% of patients attended between 2 and 3 sessions, 66.67% attended between 5 and 8 sessions, and 20.00% attended between 9 and 12 sessions.

Comparison of Treatments on Adherence

The interjudge reliability for 3 judges pooled (Intraclass Correlation(3,3)) was .65 for the supportive interventions subscale and .74 for the expressive interventions subscale. The supportive interventions and expressive interventions subscales demonstrated good internal consistency (α= .78 and .92, respectively).

The treatment groups were not significantly discriminated by the supportive interventions subscale, t(28) = −1.03, p = .311. There was a significant difference between conditions on the use of expressive interventions, t(28) = 3.37, p = .002, d = 1.24, with the relationship-focused therapists using significantly more expressive techniques than the TAU therapists.

Relation of Adherence to Symptom Course

There was a significant interaction between adherence to expressive techniques at Session 3 and time on the BASIS-24 depression score (f(1,37.42) = 10.67, p = .002, rp = .47) and the BASIS-24 total score (f(1,32.25) = 5.29, p = .028, rp = .38), but no significant interaction for HAMD scores (f(1,37.37) = 0.72, p = .400, rp = .14). The interaction between adherence to supportive techniques at Session 3 did not significantly interact with time on the BASIS-24 depression score (f(1,34.39) = 1.63, p = .211), the BASIS-24 total score (f(1,29.60) = 0.88, p = .356), or the HAMD 17-item score (f(1,35.49) = 1.10, p = .301).

To better understand the relation between adherence to expressive techniques and symptom slope, we replicated the hierarchical linear model predicting symptom slope on the BASIS-24 depression score from the adherence to expressive techniques subscale, using each of the expressive techniques items. The partial correlations for these exploratory analyses predicting symptom slope from each expressive techniques item ranged from 0.27 to 0.54 suggesting that each of the expressive techniques encompassed in the expressive techniques scale is an important intervention in helping patients achieve symptom reduction. Two items were statistically significant at p < .01 in predicting symptom slope on the BASIS-24 depression scale, including item 9 that included techniques that helped the patient explore their maladaptive responses toward others (f(1,35.18) = 9.52, p = .004, rp = .46) and item 10 that included techniques to help the patient explore how interpersonal patterns are repetitive across relationships (f(1,35.49) = 15.17, p < .001, rp = .54). Three additional expressive techniques items were significant at p < .05, including item 7 that included techniques to help elicit interpersonal stories from patients (f(1,36.70) = 4.27, p = .046, rp = .32), item 8 that included techniques to explore the patients perceived responses of others (f(1,39.21) = 4.21, p = .047, rp = .40), and item 11 that included techniques to help patients explore the historical origins of their current relationship patterns(f(1,37.18) = 4.96, p = .032, rp = .34).

Discussion

The results of this pilot randomized effectiveness trial indicate that short-term focused dynamic psychotherapy has great promise as an intervention for depression in the community mental health setting. Patients treated by community clinicians trained in SE psychotherapy had greater improvement in symptoms of depression than patients treated in the community TAU condition. Although the effect in this small pilot study only reached statistical significance on the self-report measure of depression, the large effect sizes across multiple outcome measures indicate that dynamic psychotherapy might be an effective intervention for depression. These effects are consistent with the review by Driessen et al. (2010), which reported an average Cohen's d of 0.69 for the comparison of dynamic treatment with control conditions. In comparison, a recently published fully-powered comparison of cognitive therapy to TAU for depression specifically in the community mental health system reported a Cohen's d of .59 in favor of the cognitive therapy (Simons et al., 2010) compared with effect sizes ranging from .83 to 2.02 for the slopes of change reported in the current pilot investigation.

An examination of the means and standard deviations for the symptom assessments across time points (Table 2) indicates that there were baseline differences in depression in the treatment groups with the TAU group beginning treatment with lower depressive symptoms. The hierarchical linear models revealed an advantage in symptom reduction across treatment for the SE condition, but an examination of the means for the measures of depression indicate that the treatments wound up at similar points by the end of treatment but that SE psychotherapy had a greater slope of change. We assume that the SE condition would show a similar advantage in symptom reduction across the full range of pretreatment depression levels, especially given that the measure of general psychiatric distress (the BASIS-24 total score) also showed an advantage for SE over the TAU condition. However, because the sample size was small, a fully powered trial would be necessary to reliably estimate the symptom slopes and control for baseline levels.

Our assessment of clinically meaningful change also indicated an advantage for the dynamic psychotherapy compared with the TAU condition, with 50% of SE patients and 21% of TAU patients demonstrating reliable change on the HAMD across treatment, and 44% of SE patients and 36% of TAU patients demonstrating movement into a normative range of functioning on the HAMD. On the BASIS-24, 50% of SE patients and only 29% of TAU patients demonstrated movement into the normative range of functioning across 12 weeks of study treatment. Although these response rates may seem low for both treatment groups, these results should be understood in the context of this effectiveness trial. The patients treated at community mental health centers and included in the current study are poor and indigent with extreme stress and instability in their lives. Treatment attendance is often sporadic with many life stressors often interfering in the progress of psychotherapy. Response rates for psychotherapy reported in the best done efficacy trials still reach only 40% to 60% (DeRubeis et al., 2005; Bielski, Ventura, & Chang, 2004; Keller et al., 2000) and in public sector clients, response rates for pharmacological treatments for MDD are estimated to be <30% (Rush et al., 2004). The response rates in our pilot investigation are in line with what would be expected in this community mental health sample.

The SE treatment did not result in greater treatment retention than the TAU with both treatments averaging only 6 to 7 sessions of treatment received. Again, this attendance seems poor in comparison with the percentage of completers seen in efficacy trials. However, the number of sessions attended in this study was in line with the average number of sessions attended by patients receiving outpatient services at these community mental health centers. Our goal was to include an explicit socialization to treatment in the first session to improve treatment retention. Future research will need to evaluate the factors that contribute to treatment attrition in this population and improve techniques for motivating consumers to commit to services.

The brief treatment attendance on average also could have a significant impact on the estimate of the effects of the treatment. It is possible that either treatment intervention could demonstrate larger effects and better response rates in settings where treatment attendance was maximized. The effects reported in the current study generalize to what might be expected in settings such as this community mental health setting where attrition rates are high. Even in this setting, a larger trial would be necessary to fully examine the relation between dose of treatment and response.

Analyses of treatment adherence also demonstrate that the SE psychotherapy could be significantly discriminated from TAU on adherence to the expressive relationship–focused techniques. These results suggest that the training was effective in helping community therapists use interventions to help patients unpack their maladaptive relationship patterns. Future studies should confirm that this difference in adherence to interpretive techniques between the treatments was due to the specific training in SE therapy. There was no significant difference between treatment groups on the use of supportive techniques. This result is consistent with our experience working with therapists employed in the community mental health system. These therapists often focus treatment on a collaborative supportive working relationship but are not trained in specific techniques to address maladaptive interpersonal patterns.

Finally, exploratory analyses indicated that adherence to expressive techniques across the treatment groups was significantly related to symptom slope as measured by the BASIS-24. These results suggest the possibility that use of expressive interventions results in symptom alleviation across psychotherapy (Also see Barber, Crits-Christoph, & Luborsky, 1996; Gaston, Thompson, Gallagher, Cournoyer, & Gagnon, 1998; Hilsenroth, Ackerman, Blagys, Baity, & Mooney, 2003). An examination of the individual items that predicted a decrease in depressive symptoms indicates that within dynamic psychotherapy, it is extremely important to help patients unpack their own maladaptive behaviors toward other people in their worlds and understand the repetitive nature of their patterns across relationships. The item analyses further suggest that therapists should help patients focus on describing specific relationship experiences, exploring their stereotypic ways of perceiving other peoples' responses toward them, and exploring with patients the historical origins of their relationship patterns.

Of course this pilot investigation was only able to explore covariation of adherence to expressive techniques assessed at Session 3 with symptom slope assessed from baseline to month-3 assessment. It is possible that early symptom change, which is often highly associated with final outcome, led to better adherence. Thus, this and other “third variables” might explain the obtained correlation between adherence and outcome. However, previous investigations (Barber, Connolly, Crits-Christoph, Gladis, & Siqueland, 2000) suggest that process-outcome correlations are not simply due to early symptom improvement. Future research using fully powered samples will be needed to unpack the temporal course of the relation between intervention adherence and symptom course across psychotherapy.

Although this pilot study did not allow for an independent structured interview to obtain formal diagnoses for study entry, all patients included in the study first met the self-report QIDS cutoff that has been shown to represent a score of 14 or above on the HAMD 17-item score and received at least a 14 on the independent HAMD evaluation. In addition, the majority of patients (74%) received a diagnosis of MDD from the intake clinician at the community mental health center. We included an additional 10% of patients who received a diagnosis of depressive disorder not otherwise specified because this diagnosis is often given in the community mental health setting in cases that report significant depressive symptomatology but are unclear about the length of time that symptoms have been experienced. In addition, our sample consisted of an additional 16% of patients who were not given a depression diagnosis by the community intake clinician but rather were given primary diagnoses including posttraumatic stress disorder, adjustment disorder, and dysthymia. Because these were not standardized diagnostic assessments, the reliability of the clinical diagnoses cannot be calculated. Since the majority of patients were diagnosed at intake with MDD and the baseline HAMD scores averaged 21, these results appear likely to generalize to the treatment of moderate-to-severe depression, and most likely to MDD, as diagnosed in the community mental health setting.

This pilot investigation has multiple limitations. First, effect sizes calculated using small samples may be relatively less reliable estimates of the true effect sizes. Although there was a statistically significant treatment by time effect for symptom change on the BASIS-24 depression score and treatment effect sizes were large across multiple outcome measures, it is possible that the small sample size led to an unreliable estimate of the effect. Another limitation was that the first author of the manuscript was also the clinical supervisor for the SE psychotherapy condition. Ideally, the expert clinical supervisors would be independent of the investigative team. Otherwise, it is possible that researcher allegiance could influence the expectations and confidence of the therapy providers which alone may influence treatment outcome over and above the effects of specific interventions. Finally, the HAMD ratings were conducted by trained bachelor's level research assistants who were not necessarily blind to time in treatment or treatment condition. Although the research assistants were not aware of the specific research hypotheses, it is possible that their ratings were influenced by the allegiance of the research team. It should be noted that the treatment effect sizes evident on the HAMD ratings were consistent with the effect sizes of the self-report depression measure.

Another limitation is that therapists were recruited separately for the two interventions. Therapists interested in further training were recruited for the SE training phase while therapists for the TAU were not recruited until we were ready to randomize patients. It is possible that other systematic differences between the therapist groups accounted for the effects demonstrated here. However, the fact that the treatments could be discriminated by blind adherence judges and the fact that adherence to expressive techniques predicted symptom course suggest that the effects demonstrated in this project were a result of the dynamic interventions. Further research with large samples of patients and therapists would be necessary to confirm the treatment effects.

We also provided monetary reimbursement to both patients and therapists. It is possible that payment to patients influenced their attendance at the psychotherapy sessions, although attendance for this study was similar to what is typical of outpatients at this setting. It is also possible that payment to therapists influenced study results. Although we attempted to balance payments to therapists across treatment groups, therapists in the SE group were paid honorariums for study patients treated and supervision sessions attended across both the training and randomization phases, whereas TAU therapists received payments across the randomization phase only. It is possible that differences in total compensation resulted in differences in allegiance that could influence study effects.

Finally, our adherence ratings were limited by a focus on supportive and expressive techniques only. As we adapted this treatment for use in the community mental health system, we included additional components to help this treatment succeed in this setting. This small pilot investigation was not able to parse out the effectiveness of these additional treatment components but rather evaluated only the effects of the package as a whole. In addition, our adherence ratings based on audio recordings may have not captured the subtle effects of interventions.

Despite the pilot study status of the current investigation, the results indicate that short-term dynamic psychotherapies should be further evaluated as treatments for MDD. These results indicate that a modified version of SE psychotherapy may be an especially important intervention in the treatment of MDD in the community mental health setting. Our survey of therapists working in the community indicated that relationship-focused techniques were consistent with therapists' theories of depression causality and treatment effectiveness, and these adherence results further support that therapists can learn to effectively implement the interventions focused on helping patients learn about their maladaptive relationship patterns.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health Career Development Award K01-MH63149 and Infrastructure Development Award R24-MH070698.

Appendix

Adherence Scale for Community Friendly Supportive-Expressive Psychotherapy

Please rate the therapy session using the following scale:

Rate how much the therapist engaged in the described intervention (amount) on the blank on the left side of the item using the following 7 point scale.

![]()

Supportive Techniques

-

1.

The therapist explicitly refers to the collaborative effort, using “we” or “let's” to refer to work with the patient.

-

2.

The Therapist Maintains a Relatively High Level of Comments in the Session.

-

3.

The therapist comments positively about patient improvements or successes. For example: “You have noticed something important and you've been able to make some good changes in …”

-

4.

the Therapist Conveys a Sense of Respect, Understanding and Acceptance to the Patient.

-

5.

the Therapist Conveys a Sense of Liking the Patient.

-

6.

The therapist communicates a realistically hopeful attitude that the treatment goals are likely to be achieved.

Expressive Techniques

-

7.

Therapist Elicits and/or Attends to the Patient's Stories of Specific Interactions With Other People.

-

8.

The therapist explores how the patient perceived the other person's reactions toward the patient, including actions the other person took and feelings the other person expressed.

-

9.

The therapist explores the patient's own response to the other person, including what the patient actually did and how the patient felt.

-

10.

The therapist addresses how the patient's wish and response patterns are repetitive across relationship stories.

-

11.

The therapist explores past relationship experiences that might be related to the wish and response patterns in current relationships.

-

12.

The therapist helps the patient to understand what s/he implicitly and explicitly wants or needs from other people.

-

13.

The therapist relates the patient's main wish to the patient's perceived response of other and his or her own response of self.

References

- Abbass A, Driessen E. The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: A summary of recent findings. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 2010;121:398–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01526.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (rev.) The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo P, Topreck R, Brown S, Jones J, Locke D, Sanchez J, Stadler H. Operationalization of the multicultural counseling competencies. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 1996;24:42–78. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.1996.tb00288.x. [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, Connolly MB, Crits-Christoph P, Gladis L, Siqueland L. Alliance predicts patients' outcome beyond in-treatment change in symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1027–1032. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1027. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, Crits-Christoph P. Development of a therapist adherence/competence rating scale for supportive-expressive dynamic psychotherapy: A preliminary report. Psychotherapy Research. 1996;6:81–94. doi: 10.1080/10503309612331331608. doi:10.1080/10503309612331331608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber J, Crits-Christoph P, Luborsky L. Effects of therapist adherence and competence on patient outcome in brief dynamic therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:619–622. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Levitt J, Bufka LF. The dissemination of empirically supported treatments: A view to the future. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:S147–S162. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielski RJ, Ventura D, Chang CC. A double-blind comparison of escitalopram and venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:1190–1196. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0906. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Book HE. How to practice brief psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Burnand Y, Andreoli A, Kolatte E, Venturini A, Rosset N. Psychodynamic psychotherapy and clomipramine in the treatment of major depression. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:585–590. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.5.585. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Yim LM, Donkervoet JC, Arensdorf A, Amundsen MJ, McGee C, Morelli P. Toward large-scaled implementation of empirically supported treatments for children: A review and observations by the Hawaii Empirical Basis to Services Task Force. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:165–190. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2002.tb00504.x. [Google Scholar]

- Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinareas M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Corominas J. A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:402–407. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.402. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly MB, Crits-Christoph P, Shappell S, Barber JP, Luborsky L, Shaffer C. The relation of transference interpretations to outcome in the early sessions of brief supportive-expressive psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research. 1999;9:485–495. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly Gibbons MB, Crits-Christoph P, Barber JP, Wiltsey-Stirman S, Gallop R, Goldstein LA, Ring-Kurtz S. Unique and common mechanisms of change across cognitive and dynamic psychotherapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:801–813. doi: 10.1037/a0016596. doi:10.1037/a0016596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly Gibbons MB, Crits-Christoph P, Hearon B. The empirical status of psychodynamic therapies. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:93–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141252. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly Gibbons MB, Crits-Christoph P, Narducci J, Schamberger M. A survey of therapist training and beliefs about research in community mental health centers. Poster presented at the Society for Psychotherapy Research annual conference; Rome, Italy. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Connolly Gibbons MB, Crits-Christoph K, Narducci J, Schamberger M, Gallop R. Can therapists be trained to improve their alliances? A pilot study of alliance-fostering therapy. Psychotherapy Research. 2006;13:268–281. doi:10.1080/10503300500268557. [Google Scholar]

- de Jonghe F, Kool S, van Aalst G, Dekker J, Peen J. Combining psychotherapy and antidepressants in the treatment of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;64:217–229. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00259-7. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Young PR, Salomon RM, Gallop R. Cognitive therapy vs. medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:409–416. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen E, Cuijpers P, de Maat SCM, Abbass AA, de Jonghe F, Dekker JJM. The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.010. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen SV, Gerene M, Ranganathan G, Esch D, Idieulla T. Reliability and validity of the BASIS-24 Mental Health Survey for whites, African Americans, and Latinos. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2006;33:304–323. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9025-3. doi:10.1007/s11414-006-9025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen SV, Normand SL, Belanger AJ, Spiro A, Esch D. The Revised Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-R) Medical Care. 2004;42:1230–1241. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00010. doi:10.1097/00005650-200412000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Roth A, Higgitt A. Psychodynamic psychotherapies: Evidence-based practice and clinical wisdom. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic. 2005;69:1–58. doi: 10.1521/bumc.69.1.1.62267. doi:10.1521/bumc.69.1.1.62267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston L, Thompson L, Gallagher D, Cournoyer L, Gagnon R. Alliance, technique, and their interactions in predicting outcome of behavioral, cognitive, and brief dynamic therapy. Psychotherapy Research. 1998;8:190–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gellis ZD, Kenaley B. Problem-solving therapy for depres sion in adults: A systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice. 2008;18:117–131. doi:10.1177/1049731507301277. [Google Scholar]

- Grundy CT, Lambert MJ, Grundy EM. Assessing clinical significance: Application to the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Journal of Mental Health. 1996;5:25–34. doi:10.1080/09638239650037162. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, & Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. doi:10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Pickrel SG. Multisystemic therapy: Bridging the gap between university- and community-based treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:709–717. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.709. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.63.5.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilsenroth M, Ackerman S, Blagys M, Baity M, Mooney M. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: An evaluation of statistical, clinically significant, and technique specific change. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191:349–357. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000071582.11781.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. doi:10.1037/ 0022-006X.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, Arnow B, Dunner DL, Greenberg AJ, Zajecka J. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:1462–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422001. doi:10.1056/NEJM200005183422001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distribution of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring F. Comparative effects of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy in depression: A meta-analytic approach. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:401–419. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00057-4. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López SR, Grover KP, Holland D, Johnson MJ, Kain CD, Kanel K, Rhyne MC. Development of culturally sensitive psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1989;20:369–376. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.20.6.369. [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky L. Principles of psychoanalytic psychotherapy: A manual for supportive-expressive treatment. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane WR, Dixon L, Lukens E, Lucksted A. Family psychoeducation and schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2003;29:223–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01202.x. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Hooley JM. Developing family psychoeducational treatments for patients with bipolar and other severe psychiatric disorders: A pathway from basic research to clinical trials. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1998;24:419–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1998.tb01098.x. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1998.tb01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy – Lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science. 1996;274:740–743. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.740. doi:10.1126/science.274.5288.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]