Abstract

Objective

To track the trend of the ability of U.S. nursing homes to provide on-site mental health services after the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) mandated mental illness detection and treatment for nursing home patients, and to determine cross-sectional correlates of service availability and models of services.

Methods

Retrospective analyses of the 1995-2004 National Nursing Home Surveys (NNHS) periodically conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Longitudinal trend of mental health service provision was analyzed for all and subgroups of facilities. Multivariate regression determined facility and geographic correlates in 2004.

Results

Representing the nation’s approximately 17,000 nursing homes, the NNHS suggested that roughly 80% of facilities provided on-site mental health services each year and over time. In 2004, roughly a quarter of all facilities provided each model of services – regular (25%), on call (28%), or both regular and on call (24%) services – with the remaining 23% facilities providing no on-site mental health services. Multivariate analyses found that largest facilities (≥200 beds) were more able to serve the mentally ill (odds ratio=3.80, p=.024) than small facilities (<100 beds); facilities with mass coverage by Medicare/Medicaid programs, in the northeast region, or in metropolitan areas were more likely than their counterparts to provide on-site services. Similar correlates were found for alternative service models available.

Conclusions

The overall availability of nursing home-based mental health services did not improve over time during the post-OBRA era. Service availability is more problematic for certain facilities such as small or rural ones. Financial, regulatory, and system-level efforts are needed to address this issue.

Keywords: nursing home, mental health services, OBRA, NNHS

INTRODUCTION

The approximately 17,000 nursing homes in the United States provide care to over 1.6 million persons annually. Studies have reported that between 60 and 90 percent of nursing home residents have diagnosable mental disorders (including dementia) (1-3). Despite the high prevalence of mental disorders among nursing home residents and their pressing need for adequate mental health care, it is often the case that nursing homes lack the essential expertise, commitment, and financial incentives to ensure appropriate detection and treatment of mental disorders (4). The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1987 required nursing homes to perform preadmission screening and annual resident review to ensure that mentally-ill persons are not inappropriately admitted to nursing homes, and that mentally-ill residents who were appropriately placed receive necessary mental health services (5,6). Nevertheless, evidence suggests that the level of mental health care received by residents with mental disorders was still far below their actual needs after OBRA 1987 was implemented in the early 1990s (7-10). In a detailed chart review of over 2000 Maryland nursing home residents in 1995, Fenton and colleagues found that only 20 percent of residents had a psychiatric consultation within 90 days of admission (9).

Enhancing the ability and incentives of nursing homes to supply mental health services is a key component of steps to address this apparent discrepancy. Studies have suggested that on-site mental health services provided to nursing home residents resulted in improved clinical outcomes and reduced acute resource utilizations (11,12). However, the function of the nursing home and its care and staff structures have been historically focused on the management of chronic medical conditions and functional disabilities, rather than psychiatric and behavioral abnormalities (8). As a result, expansion of nursing home service lines in response to the requirement of OBRA 1987 may take place slowly or barely take place, and is expected to depend on intrinsic facility characteristics. Until now, however, no studies have described the longitudinal change of nursing homes in their ability to provide mental health services during the post-OBRA era.

This study was designed to track the historical trend of provision of mental health services in U.S. nursing homes, based on the periodically conducted National Nursing Home Surveys between 1995 and 2004. Using the most recent data of 2004, this study further determined nursing home characteristics that may affect the ability to provide on-site mental health services and models of services.

METHODS

Data sources

This study obtained the public use, facility files of the 1995, 1997, 1999 and 2004 National Nursing Home Surveys (NHHS), which include cross sectional and nationally representative samples of US nursing homes collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Details of survey methodologies can be found in the NNHS website (13) and the relevant reports thereof. Briefly, the sampling frame of each year’s NNHS consisted of all nursing homes that were certified by Medicare and/or Medicaid or not certified but licensed by individual states. In each year the survey involved a stratified 2-stage probability design where the selection of nursing homes in the first stage was stratified by bed size, certification status, and/or other facility characteristics; nursing homes were finally selected with the probability proportional to bed size. The probability sampling, together with rigorous data collection protocols and data editing mechanisms, ensures that each survey contained a nationally representative sample of nursing homes, including their services, staff, and residents (14-17).

In each survey, specifically-trained field interviewers collected facility data through personal interviews with nursing home administrators. Completed questionnaires were entered into a computer database by data specialists from the CDC, and extensive editing was conducted to assure that all responses were accurate, logical, and complete. The number of nursing homes included in the sample was 1409 in the 1995 NNHS, 1406 in the 1997 NNHS, 1423 in the 1999 NNHS, and 1174 in the 2004 NNHS (see Table 1), with the annual response rate ranging between 81% and 95%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of U.S. nursing homes, 1995-2004

| Characteristic | 1995 | 1997 | 1999 | 2004 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of nursing homes in the sample | 1,409 | 1,406 | 1,423 | 1,174 |

| Provision of on-site mental health services, % | 74.8 | 81.1 | 79.5 | 77.7 |

| Regular only | -- | -- | -- | 25.1 |

| On call only | -- | -- | -- | 24.2 |

| Both regular and on call | -- | -- | -- | 28.4 |

| Chain affiliation, % | 55.0 | 56.4 | 59.9 | 54.2 |

| Non-profit, % | 34.4 | 32.7 | 33.5 | 38.4 |

| Bed size, % | ||||

| <50 | 6.8 | 13.1 | 11.6 | 14.0 |

| 50-99 | 25.9 | 37.2 | 38.8 | 37.7 |

| 100-199 | 45.9 | 42.1 | 41.6 | 42.0 |

| ≥200 | 21.4 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 6.3 |

| Percent of Medicare residents, % | ||||

| <10% | -- | -- | -- | 52.7 |

| 10-19% | -- | -- | -- | 32.4 |

| ≥20% | -- | -- | -- | 14.9 |

| Percent of Medicaid residents, % | ||||

| <20% | -- | -- | -- | 9.4 |

| 20-39% | -- | -- | -- | 7.6 |

| 40-59% | -- | -- | -- | 20.7 |

| 60-79% | -- | -- | -- | 40.7 |

| ≥80% | -- | -- | -- | 21.6 |

| Accredited by JACHO, CARF, and/or CCAC, % | -- | -- | -- | 15.1 |

| Census region, % | ||||

| Northeast | -- | -- | -- | 17.1 |

| Midwest | -- | -- | -- | 32.7 |

| South | -- | -- | -- | 33.7 |

| West | -- | -- | -- | 16.5 |

| Located in an MSA, % | 69.1 | 61.4 | 61.3 | 68.2 |

JACHO= Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations;

CARF=Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities;

CCAC= Continuing Care Accreditation Commission;

MSA=metropolitan statistical area.

Variables

The NNHS collected a useful set of nursing home characteristics each year with the latest survey of 2004 containing more abundant information. Each survey asked the question whether or not mental health services were provided in the nursing home (the outcome variable of interest). Other facility variables collected in all surveys included whether the nursing home was chain affiliated, the profit status of the facility (for profit or nonprofit), bed size (categorized as <50, 50-99, 100-199, and ≥200), and whether it was located in a metropolitan statistical area (MSA). For nursing homes that did provide on-site mental health services, the 2004 survey further asked whether the services were available regularly (or at routinely scheduled times), in an on call manner (or as needed), or in both regular and on call manners. Additional facility variables collected in the 2004 survey were percent of Medicare residents (categorized as <10%, 10-19%, and ≥20%); percent of Medicaid residents (<20%, 20-39%, 40-59%, 60-79%, and ≥80%); whether the nursing home was accredited by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JACHO), Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF), and/or Continuing Care Accreditation Commission (CCAC); and census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West).

Statistical Analyses

The study first performed univariate analyses of each cross sectional sample to summarize nursing home characteristics. Stratified analyses were further performed to track over time the percent of nursing homes that provided on-site mental health services, by (1) profit status, (2) chain affiliation status, (3) bed size category, and (4) location in an MSA or not. Because the CDC did not release sample weights for the 1995 facility data which would have allowed for population extrapolation, statistics of these analyses represented sample estimates. Sensitivity analyses were performed that took into account for the complex sampling design of the data in years other than 1995. Given the large sample of facilities in each year and the fact that the sampling process likely affected the estimated standard errors but not point estimates, the results in the sensitivity analyses (ie, cross-sectional estimates and trend over time) remained similar and therefore were not reported here.

Multivariate analyses were subsequently performed focusing on the 2004 data. First, the study estimated a binary logistic regression model of on-site availability (yes/no) of mental health services as a function of the intrinsic nursing home characteristics described before (bed size collapsed into 3 categories: <100, 100-199, and ≥200; and percent of Medicaid residents collapsed into ≥20% or not). Additionally, a multinomial logistic regression model was estimated to determine the independent associations of nursing home characteristics with the likelihood of having a particular model of mental health care – regular, on call, or both regular and on call. Nursing homes with each type of services were compared to the group of nursing homes that did not provide on-site mental health services.

In order to account for the complex sampling methodologies in 2004 including stratification, clustering, and weighting, both regression models were estimated using the survey estimation routines contained in STATA version 8.0, Special Edition (Stata Co., College Station, TX). The study reported odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values estimated from the regression. This funded project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Irvine.

RESULTS

Trends over time

The percent of nursing homes that provided on-site mental health services to their residents was 75% in 1995, 81% in 1997, 80% in 1999, and 78% in 2004 (Table 1). In 2004, approximately 25% of all nursing homes provided regular mental health services, 24% provided on call services, and 28% provided both regular and on call services.

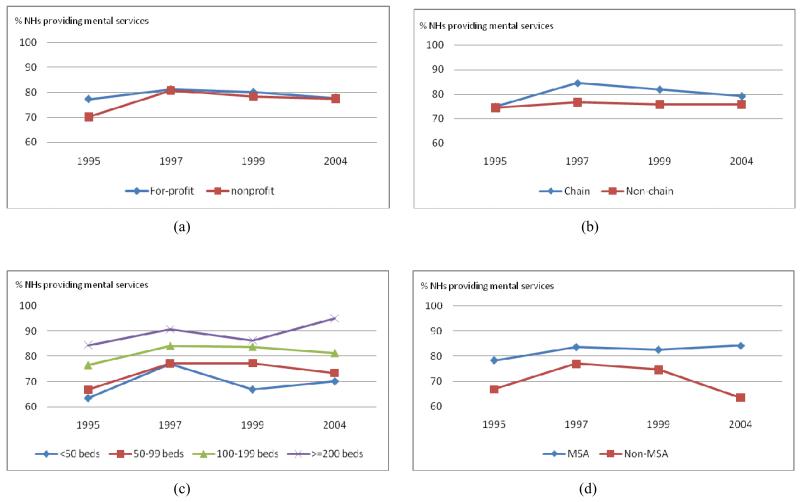

Table 1 also shows that between 1995 and 2004, approximately 50 to 60 percent of nursing homes were chain affiliated, over 30% were nonprofit, and over 60% were located in an MSA. Although 21% of nursing homes had over 200 beds in 1995, this number declined to less than 10% thereafter. Figure 1–panels (a) and (b) show that over the period of 1995-2004, for profit facilities were more likely than nonprofit facilities to supply on-site mental health serves, and chain affiliated facilities were more likely than non-chain affiliated facilities to provide mental health services, although group differences were not substantial in both cases (ie, <10%), and the longitudinal trend for each type of facilities was flat.

Figure 1.

Percentage of U.S. nursing homes (NHs) providing on-site mental health services, 1995-2004: by (a) profit status, (b) chain affiliation, (c) bed size, and (d) location in a metropolitan statistical area (MSA).

On the other hand, larger facilities and facilities in an MSA were more likely than their counterparts to provide on-site mental health services (panels (c) and (d) of Figure 1). Comparing facilities with ≥200 beds to facilities with <50 beds, the analysis found that the differences were 21% in 1995 (85% versus 64%), 14% in 1997 (91% versus 77%), 19% in 1999 (86% versus 67%), and 25% in 2004 (95% versus 70%). Compared to non-MSA facilities, the increased rate of providing on-site mental health services for MSA facilities was 11% in 1995 (78% versus 67%), 7% in 1997 (84% versus 77%), 8% in 1999 (83% versus 75%), and 21% in 2004 (84% versus 63%), the enlarged difference in 2004 resulting mainly from the reduced proportion of non-MSA facilities providing mental health services from 1999 to 2004.

Nursing home characteristics associated with provision of mental health services

In 2004, several facility characteristics were found to be independently associated with the on-site availability of mental health services and models of services. Table 2 shows that in the analyses of overall availability (yes/no), the odds ratio (OR) was 3.80 (p=.024) for largest facilities (≥200 beds) relative to small facilities (<100 beds), 1.53 (p=.015) for facilities having 10-19% Medicare residents relative to facilities with <10% Medicare residents, 2.22 (p=.005) for facilities with ≥20% Medicaid residents versus otherwise, and 2.60 (p=.000) for MSA versus non-MSA facilities. Compared to facilities in the northeast, the ORs for facilities in other regions were approximately .20 – .30 (p≤.001 for all cases), suggesting substantially reduced service capacities in these regions.

Table 2.

Multivariate predictors of provision of mental health services in U.S. nursing homes, 2004

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain affiliation | 1.15 | .85-1.55 | .360 |

| Non-profit | 1.14 | .82-1.59 | .440 |

| Bed size | |||

| <100 | Reference | ||

| 100-199 | 1.24 | .89-1.71 | .200 |

| ≥200 | 3.80 | 1.19-12.10 | .024 |

| Percent of Medicare residents | |||

| <10% | Reference | ||

| 10-19% | 1.53 | 1.09-2.16 | .015 |

| ≥20% | 1.47 | .89-2.41 | .131 |

| Percent of Medicaid residents≥20% | 2.22 | 1.28-3.84 | .005 |

| Accredited by JACHO, CARF, and/or CCAC | 1.53 | .89-2.64 | .122 |

| Census region | |||

| Northeast | Reference | ||

| Midwest | .27 | .13-.57 | .001 |

| South | .17 | .08-.36 | .000 |

| West | .21 | .09-.46 | .000 |

| Located in an MSA | 2.60 | 1.94-3.50 | .000 |

95% CI=95% Confidence Interval;

JACHO= Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations;

CARF=Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities;

CCAC= Continuing Care Accreditation Commission;

MSA=metropolitan statistical area.

In the analyses of available service models (Table 3), bed size, Medicare and Medicaid populations, census region, and MSA status were still found to be significant predicators. Most prominently, facilities with ≥200 beds were over 4 times as likely as facilities with <100 beds to provide regular or both regularly and on call mental health services; facilities with ≥20% Medicaid residents were 3 to 4 times as likely as other facilities to provide regular or both regular and on-call services; and compared to facilities in the northeast, facilities in other regions were 10 to 30 percent as likely to provide any models of services.

Table 3.

Multivariate predicators of mental health service models in U.S. nursing homes, 2004

| Regular only |

On call only |

Regular & on-call |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Chain affiliation | 1.16 | .80-1.68 | .440 | 1.14 | .78-1.66 | .513 | 1.17 | .82-1.67 | .397 |

| Non-profit | 1.00 | .67-1.49 | .992 | 1.42 | .94-2.13 | .096 | 1.04 | .70-1.53 | .861 |

| Bed size | |||||||||

| <100 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 100-199 | 1.32 | .89-1.95 | .174 | .94 | .63-1.40 | .764 | 1.50 | 1.03-2.18 | .034 |

| ≥200 | 4.26 | 1.27-14.26 | .019 | 2.54 | .70-9.28 | .158 | 4.74 | 1.43-15.71 | .011 |

| Percent of Medicare residents | |||||||||

| <10% | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 10-19% | 1.70 | 1.12-2.56 | .012 | 1.56 | 1.01-2.39 | .043 | 1.33 | .89-1.97 | .160 |

| ≥20% | 1.52 | .85-2.72 | .159 | 1.81 | 1.01-3.23 | .046 | 1.06 | .58-1.95 | .845 |

|

Percent of Medicaid

residents≥20% |

3.59 | 1.72-7.49 | .001 | 1.41 | .76-2.60 | .276 | 3.36 | 1.59-7.13 | .002 |

|

Accredited by JACHO, CARF,

and/or CCAC |

1.43 | .77-2.65 | .261 | 1.64 | .90-2.98 | .104 | 1.44 | .78-2.68 | .245 |

| Census region | |||||||||

| Northeast | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Midwest | .26 | .12-.57 | .001 | .28 | .12-.63 | .002 | .28 | .13-.60 | .001 |

| South | .19 | .08-.41 | .000 | .21 | .09-.47 | .000 | .14 | .06-.30 | .000 |

| West | .12 | .05-.30 | .000 | .38 | .16-.90 | .028 | .15 | .06-.36 | .000 |

| Located in an MSA | 2.77 | 1.93-3.97 | .000 | 2.64 | 1.81-3.84 | .000 | 2.45 | 1.72-3.50 | .000 |

OR=Odds Ratio;

95% CI=95% Confidence Interval;

JACHO= Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations;

CARF=Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities;

CCAC= Continuing Care Accreditation Commission;

MSA=metropolitan statistical area.

DISCUSSION

This study based on nationally representative surveys of U.S. nursing homes reveals that over the decade (1995-2004) after OBRA 1987 was implemented, approximately 80 percent of nursing homes provided on-site mental health services. Overall service availability in nursing homes did not change over time, and facilities in non-metropolitan areas showed a recent decline from 1999 to 2004. Facility characteristics including bed size, Medicare and Medicaid census, and location in an MSA were positively associated with on-site provision of mental health services, while location in regions other than the northeast predicted a substantial reduction in both overall service availability and specific models of services (ie, regular, on call, or both regular and on call services).

Although OBRA 1987 intended to provide new protections for nursing home residents and those with mental disorders, analyses in this study suggest that a number of over 3000 nursing homes (ie, 20% nationally) did not seem to be able to serve appropriately the mentally ill. In addition, as it largely manifested in 2004, expansion in nursing home care to serve the unique need of the mentally ill tended to be more difficult for such facilities as smaller ones, those without mass coverage by federal and state programs, and those in rural areas. In addition to the stipulations contained in OBRA 1987, a number of relevant regulatory requirements, reimbursement policies, and quality assurance efforts (discussed below) were initiated during the study period. However, the relatively stable numbers of nursing homes without on-site service capacities over time suggest that these initiatives may have little impact on the overall access to mental health care for nursing home residents.

Indeed, policies and initiatives over this period may be inconsistent and create disincentives for nursing homes to supply on-site mental health care. For example, during the initial implementation stage of OBRA 1987 in the early 1990s, Medicare benefits were expanded to cover mental health services delivered in nursing homes by clinical psychologists and social workers. However, Medicare expenditures for nursing home-based mental health services tripled in subsequent years and concerns arose that residents may receive unjustified treatments that are not beneficial to their mental disorders (18). As a result, the Medicare suspended independent reimbursement to nursing homes for mental health services provided by social workers as of 1999 (19). In addition, the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 repealed federal standards for state Medicaid programs to reimburse nursing home care and allowed individual states to set their own rates. The overall low rate of Medicaid payment, and particularly the much lower rates set by states experiencing budget cuts (20,21), may not ensure appropriate nursing home care or access to specialized care by mentally-ill residents.

According to federal mandates nursing homes subject to annual scrutiny by state surveyors, who – through on-site inspections, interviews with representative nursing staff and residents, and selected medical record reviews – identify deficiencies in care, including mental health care, and mandate corrections and possible sanctions for identified deficiencies (22). However, widespread concerns exist about whether state inspections can ensure appropriate nursing home care (23,24), and weaknesses of state oversights on mental health services in nursing homes have been repeatedly reported by the federal Office of the Inspector General (OIG) (25,26). In responses to these OIG reports, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) recently called for improved survey and certification process targeted at mentally-ill residents (27). However, the impact of this and other efforts of state inspections on ensuring better access to mental healthcare is yet to be evaluated.

The Medicare and many private insurance programs do not provide for parity in mental healthcare coverage. For example, Medicare-covered psychosocial services in nursing homes require a 50% copayment rather than the regular 20% copayment for medical and surgical care, which tends to impede nursing home residents’ access to essential behavioral treatments. The facts that private insurers may have more restrictive plan policies and that the Medicaid provides second-parity coverage for out-of-pocket expenses may explain the findings that nursing homes catering for a higher number of publicly-insured residents were more likely to provide on-site mental health services.

Nevertheless, the overall inadequate coverage for mental healthcare in nursing homes by the Medicare and Medicaid programs, which together account for the majority of nursing home payments, discourages specialty mental health providers to serve the mentally ill. For example, a survey of approximately 900 nursing directors in 6 states found that the availability of psychiatric consultations to nursing homes was deemed to be inadequate by a half of nursing directors, and that non-pharmacologic management and behavioral interventions, which tended to be uncovered or ill-reimbursed, were largely overlooked by consulting specialists (8). As a further note, the gross shortfall of geriatric psychiatrists and other professionals (28) tend to worsen the substantial unmet needs for specialist care by mentally-ill residents, especially those residing in small or rural facilities, and facilities in certain regions (8).

Further analyses of service models in this study suggested that in 2004, approximately a quarter of all nursing homes provided each type of services – regular (25%), both regular and on call (24%), or only on call (28%) services –with the remaining 23% facilities providing no on-site mental health services. This suggests that the ability to ensure adequate mental health services is also likely to vary among those facilities that do provide such services. Bartels and colleagues (12) reviewed relevant literature on models of on-site mental health services in nursing homes, and found that the traditional consultation-liaison service on a one-time, on call basis tended to be least effective in improving clinical outcomes and reducing acute care utilizations, such as hospitalizations. They concluded that the routine presence of mental health specialists combined with a multidisciplinary team is a preferred model of delivering mental health care in nursing homes. Nevertheless, it is often the case that nursing homes cannot arrange formal contracts with consultant psychiatrists to ensure their routine availability (8). Therefore, additional efforts are needed to remove the financial, institutional, and system-level barriers to obtaining routine specialist care for mentally-ill nursing home residents.

This study has several limitations. First, although the analyses were based on well-conducted, nationally representative surveys of U.S. nursing homes, the CDC did not release more complete information on nursing home characteristics in the public-use data, which prevented this study from performing fuller analyses of both the historical trend and cross-sectional correlates of service availability. Future research is needed to investigate other facility, geographic, and policy factors that affect the provision of appropriate mental health services in nursing homes. Second, non-responding nursing homes in the survey may bias the results of the findings. However, given the large sample and high response rate in each survey, response bias may not be an important issue.

A third limitation is that although this study analyzed the availability and, when available, models of mental health services in nursing homes, detailed information on the actual care received by mentally-ill residents, or its adequacy and quality, was not available. The public-use NNHS data do not include unique facility and resident identifiers that would allow us to identify residents in the sampled nursing homes and evaluate their actual needs for mental health care and actual care received. However, given the high prevalence of mental illnesses among nursing home residents (1-3), the finding of this study that a large number of nursing homes did not provide appropriate on-site mental health services suggested a significant policy and practice issue. Finally, analyses of this study spanned the decade of 1995-2004 and found that the overall availability of nursing home-based mental health services did not improve over this period. Further studies are needed to determine whether it is still the case in more recent years.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests the constant inability of over 3000 nursing homes in the nation to provide on-site mental health services, which corroborates earlier evidence that a substantial number of mentally-ill residents did not have adequate access to needed services during the post-OBRA era (7-10). The findings also suggest that this lasting deficit in mental health care access may be more pronounced for smaller or rural facilities, facilities in regions other than the northeast, and facilities serving a small number of publicly-insured residents. It is imperative that governments, regulators, policy makers, and healthcare professionals work together to craft supportive mechanisms that can expand the availability of essential mental health services in nursing homes.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: Funded by the National Institute on Aging under the grant R01AG032264.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests: no conflicts of interest for the author.

REFERENCE

- 1.Mechanic D, McAlpine DD. Use of nursing homes in the care of persons with severe mental illness: 1985 to 1995. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51(3):354–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reichman WE, Katz PR. Psychiatric care in the nursing home. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Streim JE, Oslin D, Katz IR, et al. Lessons from geriatric psychiatry in the long-term care setting. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1997;68(3):281–307. doi: 10.1023/a:1025440408223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ickowicz E. The American Geriatrics Society and American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry recommendations for policies in support of quality mental health care in U.S. nursing homes. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2003;51(9):1299–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.HCFA Medicare and Medicaid programs; preadmission screening and annual resident review. Final rule with comment period. Federal Register. 1992;57(230):56450–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.HCFA Medicare and Medicaid; requirements for long term care facilities. Final rule. Federal Register. 1991;56(187):48826–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linkins KW, Lucca AM, Housman M, et al. Use of PASRR programs to assess serious mental illness and service access in nursing homes. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(3):325–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichman WE, Coyne AC, Borson S, et al. Psychiatric consultation in the nursing home. A survey of six states. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1998;6(4):320–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenton Fenton J, Raskin A, Gruber-Baldini AL, et al. Some predictors of psychiatric consultation in nursing home residents. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shea DG, Russo PA, Smyer MA. Use of mental health services by persons with a mental illness in nursing facilities: initial impacts of OBRA87. Journal of Aging & Health. 2000;12(4):560–78. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith M, Mitchell S, Buckwalter KC, et al. Geropsychiatric nursing consultation: a valuable resource in rural long-term care. Archieves of Psychiatric Nursing. 1994;8(4):272–9. doi: 10.1016/0883-9417(94)90069-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartels SJ, Moak GS, Dums AR. Models of mental health services in nursing homes: a review of the literature. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(11):1390–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Nursing Home Survey (NNHS) Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nnhs.htm.

- 14.Gabrel C, Jones A. The National Nursing Home Survey: 1995 summary. Vital and Health Statistics. 2000;13(146):1–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabrel CS, Jones A. The National Nursing Home Survey: 1997 summary. Vital and Health Statistics. 2000;13(147):1–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones A. The National Nursing Home Survey: 1999 summary. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics. 2002;13(152) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, et al. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 overview. Vital and Health Statistics. 2009;13(167):1–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mental health services in nursing facilities . US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General; May, 1996. Pub OEI-02-91-00860. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Streim JE, Beckwith EW, Arapakos D, et al. Regulatory oversight, payment policy, and quality improvement in mental health care in nursing homes. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(11):1414–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grabowski DC. Medicaid reimbursement and the quality of nursing home care. Journal of Health Economics. 2001;20(4):549–69. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grabowski DC, Angelelli JJ, Mor V. Medicaid payment and risk-adjusted nursing home quality measures. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2004;23(5):243–52. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.5.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrington C, Carrillo H. The regulation and enforcement of federal nursing home standards, 1991-1997. Medical Care Research and Review. 1999;56(4):471–94. doi: 10.1177/107755879905600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.General Accounting Office . Nursing home quality: Prevalence of serious problems, while declining, reinforces importance of enhanced oversight. Washington, D.C.: 2003. Publication No. GAO-03-561. [Google Scholar]

- 24.IOM: Institute of Medicine . Improving the quality of care in nursing homes. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Younger nursing facility residents with mental illness: Preadmission screening and resident review (PASRR) implementation and oversight. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General; Jan, 2001. Pub OEI-05-99-00700. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levinson DR. Preadmission screening and resident review for younger nursing facility residents with serious mental illness. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General; 2007. Pub OEI-05-05-00220. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Pre-Admission Screening and Resident Review (PASRR) and the Nursing Home Survey Process. Sep, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juul D, Scheiber SC. Subspecialty certification in geriatric psychiatry. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11(3):351–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]