Abstract

The feasibility of transcranial passive acoustic mapping with hemispherical sparse arrays (30 cm diameter, 16 to 1372 elements, 2.48 mm receiver diameter) using CT-based aberration corrections was investigated via numerical simulations. A multi-layered ray acoustic transcranial ultrasound propagation model based on CT-derived skull morphology was developed. By incorporating skull-specific aberration corrections into a conventional passive beamforming algorithm (Norton and Won 2000 IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 38 1337–43), simulated acoustic source fields representing the emissions from acoustically-stimulated microbubbles were spatially mapped through three digitized human skulls, with the transskull reconstructions closely matching the water-path control images. Image quality was quantified based on main lobe beamwidths, peak sidelobe ratio, and image signal-to-noise ratio. The effects on the resulting image quality of the source’s emission frequency and location within the skull cavity, the array sparsity and element configuration, the receiver element sensitivity, and the specific skull morphology were all investigated. The system’s resolution capabilities were also estimated for various degrees of array sparsity. Passive imaging of acoustic sources through an intact skull was shown possible with sparse hemispherical imaging arrays. This technique may be useful for the monitoring and control of transcranial focused ultrasound (FUS) treatments, particularly non-thermal, cavitation-mediated applications such as FUS-induced blood-brain barrier disruption or sonothrombolysis, for which no real-time monitoring technique currently exists.

1. Introduction

Focused ultrasound (FUS) therapy shows great potential in a number of transcranial applications, including thermal ablation for brain tumor therapy (Hynynen & Clement 2007, McDannold et al. 2010) and the treatment of functional brain disorders such as chronic pain (Martin et al. 2009, Jeanmonod et al. 2012) and essential tremor (Elias et al. 2011, Lipsman et al. 2013), sonothrombolysis for stroke treatment (Alexandrov et al. 2004, Culp et al. 2011, Medel et al. 2009, Burgess et al. 2012), and blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption for targeted drug and gene delivery (Hynynen et al. 2001, Choi et al. 2007, McDannold et al. 2012, Chen et al. 2010, Huang et al. 2012). The use of FUS is particularly attractive for brain therapy as it is non-ionizing, can be applied non-invasively, and can be used to deliver unlimited retreatment sessions over time. In practice however, the use of ultrasound (US) in the brain is limited by the skull bone, which presents unique challenges for transcranial therapy.

The human skull is a complex structure possessing a large degree of heterogeneity that manifests itself through spatial variations in skull thickness, density, and shape. The skull’s acoustical properties also vary spatially due to their dependance on bone density (Clement & Hynynen 2002b, Connor et al. 2002, Pichardo et al. 2011). As a result, sound waves undergo location-specific phase shifts as they pass through the skull, leading to a defocusing of the beam. Further distortion exists due to the propagation of shear waves in bone, generated through acoustic mode conversion (Clement et al. 2004), which travel at different speeds than longitudinal waves (White et al. 2006). Apart from acting as a defocusing lens, the skull also has a very high insertion loss due to the effects of specular reflections and attenuation (Fry & Barger 1978). During transcranial FUS treatments, these factors can cause unwanted distortions in the location and shape of the therapeutic focus, along with a reduction in focal intensity (Sun & Hynynen 1998).

The aberrations of the US field induced by the skull bone can be overcome through the use of a large-aperture phased array transducer (Clement, Sun, Giesecke & Hynynen 2000). Multi-channel driving electronics (Daum et al. 1998) allow each element in the array to be driven independently, and with an appropriate choice of driving signals the effects of the skull can be negated and precise transcranial focusing can be achieved (Thomas & Fink 1996, Hynynen & Jolesz 1998). The use of large-scale, hemispherical phased arrays allows for small focal volumes with large gains (Sun & Hynynen 1999), and geometrically minimizes the unwanted effects of skull heating (Clement, White & Hynynen 2000) and standing waves (Song et al. 2012).

A number of methods for calculating array element driving signals for transcranial focusing have been proposed, including time delay (i.e. phase conjugation for harmonic signals) (Smith et al. 1986, Hynynen & Jolesz 1998, Clement, Sun, Giesecke & Hynynen 2000) combined with amplitude or inverse amplitude correction (White et al. 2005), as well as time-reversal (Thomas & Fink 1996, Fink et al. 2003) and inverse-filter (Tanter et al. 2000, Tanter et al. 2001, Aubry et al. 2001) techniques. Although these methods initially required the placement of an invasive transducer at the desired focus (Smith et al. 1986, Hynynen & Jolesz 1998, Thomas & Fink 1996), more recently it has been demonstrated that numerical US propagation models based on skull morphology obtained from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Hynynen & Sun 1999) or computed tomography (CT) (Aubry et al. 2003, Clement & Hynynen 2002a) scans of the head can be employed to predict the aberration corrections non-invasively. Simulation-based transskull focusing using pre-operative CT scans (Clement & Hynynen 2002a) has been successfully applied in clinical studies (Martin et al. 2009, McDannold et al. 2010, Jeanmonod et al. 2012).

Transcranial FUS therapy is currently guided by MRI, as it allows for precise targeting, temperature monitoring during thermal-based therapies, as well as post-treatment evaluation (McDannold et al. 2010, Jeanmonod et al. 2012, Elias et al. 2011). Unfortunately, real-time monitoring of non-thermal applications, including cavitation-mediated treatments such as FUS-induced BBB disruption and sonothrombolysis, has yet to be realized. Magnetic resonance thermometry is not an option, as there is no appreciable temperature rise generated during such procedures (Hynynen et al. 2001). However, spectral characteristics of the generated cavitation field during both sonothrombolysis (Datta et al. 2006, Datta et al. 2008, Wright et al. 2012) and FUS-induced BBB disruption (McDannold et al. 2006b, Tung et al. 2010, O’Reilly & Hynynen 2012, Arvanitis et al. 2012) procedures have been correlated with the biological effects of the sonications, and may offer a real-time method to monitor and control the treatments (O’Reilly & Hynynen 2012, Arvanitis et al. 2012).

The adoption of traditional passive imaging with receiver arrays (Hahn 1975, Sato & Sasaki 1977, Norton & Won 2000) to allow for the spatial mapping of cavitation activity over time during the application of FUS, termed passive acoustic mapping (PAM), is becoming increasingly widespread (Salgaonkar et al. 2009, Farny et al. 2009, Gyöngy & Coussios 2010a, Gyöngy & Coviello 2011, Gyöngy & Coussios 2010b, Gateau et al. 2011, Coviello et al. 2012, Choi & Coussios 2012, Haworth et al. 2012, Jensen et al. 2012). Such spatiotemporal monitoring of microbubble activity would be beneficial during cavitation-mediated FUS brain treatments, both to confirm that cavitation and its associated bioeffects are localized at the therapeutic focus, and to control the exposures based on spatial maps of microbubble activity within the skull cavity. In the brain, mapping of the microbubble activity is further complicated by the presence of the skull bone. Indeed, if not properly accounted for, the skull-induced aberrations of propagating acoustic emissions from microbubbles will lead to image distortions and artifacts upon reconstruction. Nevertheless, we hypothesize that if the appropriate corrections to the wave propagation to eliminate the skull-induced distortions are known a priori, or can be calculated, PAM could be used in the brain. In addition, the hemispherical arrays used for transcranial FUS therapy would be well suited for PAM, since large aperture arrays provide superior spatial resolution during passive imaging (Norton & Won 2000).

Through the use of computer simulations, this study investigates the feasibility of transcranial PAM via hemispherical sparse imaging arrays. Sparse arrays have been investigated for both traditional active US imaging (Turnbull & Foster 1991, Lockwood & Foster 1996) and FUS therapy (Goss et al. 1996, Gavrilov & Hand 2000, Pernot et al. 2003), due primarily to their strong performance and relatively low technical complexity. Sparse arrays are of particular interest when large apertures are desired. For example, a traditional fully-populated (i.e. inter-element spacing ≤ λ/2, where λ is the acoustic wavelength (Steinberg 1976)) 30 cm diameter hemispherical array with circular elements operating at 1 MHz would require over 250 000 individual elements. The cost associated with manufacturing the large number of elements and accompanying electronics for such a design is substantial, and prohibitive with current prices. Furthermore, large-aperture sparse array systems with more modest element counts can be driven with currently available multi-channel electronics (Cheung et al. 2012).

In this study a multi-layered ray acoustic transcranial US propagation model based on CT-derived skull morphology was developed and used to compute the skull corrections required for transcranial image formation. By incorporating these skull-specific aberration corrections into a conventional beamforming algorithm (Norton & Won 2000), simulated acoustic source fields were spatially localized through three digitized human skulls. The effects of array sparsity and receiver element configuration on the formation of passive acoustic maps were examined, with the aim of guiding the integration of a hydrophone array within an existing transcranial phased array prototype (Song & Hynynen 2010), to provide it with imaging capabilities. For one skull specimen, multiple source locations spanning a wide range of distances along each Cartesian dimension were simulated to determine the imageable volume within the skull cavity. Finally, the reconstruction algorithm’s sensitivity to noise was explored.

2. Methods

2.1. CT Skull Morphology

CT scans (LightSpeed VCT, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St Giles, UK) of three (SKA, SKB, SKC) human cadaver skulls (The Bone Room, Berkeley, CA, USA) were analyzed to extract each specimen’s morphological information. The skull specimens were scanned individually within a large plastic container filled with degassed, deionized water, and the imaged volume consisted of 512 × 512 × 328 voxels with a uniform voxel size of 625 × 625 × 625 µm3. The skull density (ρ) was estimated from the CT image intensity, acquired in Hounsfield units (HU), using a linear function of the form: ρ = a · HU + b. The two parameters a and b were computed based on the density and Hounsfield intensity of water and air, both visible in the CT scans (Connor et al. 2002, Pulkkinen et al. 2011). The resulting density maps were manually segmented in MATLAB (R2010b, Mathworks, Natick, MA) to extract all possible bone voxels. The segmented data were fed into an open source isosurface generation algorithm to generate triangulated meshes of the inner and outer skull surfaces (Treece et al. 2000). All meshes were created such that no surface area element was greater than (λ/2)2, where λ is the acoustic wavelength in water. The density maps were registered with the skull meshes and, together, defined the material parameters and the physical geometry of the skull used in the transcranial US propagation model. The skulls were positioned relative to the hemispherical array to maximize the usable skull surface area, while avoiding the ear and eye orifices due to the complex nature of the human cranial morphology in these locations, and also because in practice the therapeutic targets within the brain lie superior to these points. In terms of the Cartesian coordinate system present in the results that follow, the x-, y-, and z-axes represent the anterior-to-posterior, left-to-right, and inferior-to-superior axes, respectively.

2.2. Transcranial Ultrasound Propagation Model

The transskull propagation of US was simulated using a multi-layered ray acoustic model (Sun & Hynynen 1998) based on the Rayleigh-Sommerfeld integral (O’Neil 1949), which models linear sound propagation in the temporal frequency domain, taking into account acoustic wave refraction at curved tissue interfaces (Fan & Hynynen 1994). A previously reported 3-layered ray acoustic model that includes shear wave propagation within the skull bone (Pichardo & Hynynen 2007) was augmented by including corrections that take into account the skull’s spatially dependent material properties. This was achieved by calculating spatially averaged acoustical properties independently for each ray path traversing the skull. The mathematical details behind the transcranial US propagation model used in this study are presented in the appendix.

2.3. Transcranial Beamforming Algorithm

In simulating transcranial PAM, the propagation model was used both to simulate the signals recorded by the virtual array from an acoustical source field located within the brain, and to calculate each hydrophone’s set of skull corrections required for transcranial image reconstruction. The skull-specific corrections were incorporated into a conventional passive beamforming algorithm known as Time Exposure Acoustics (TEA), described in (Norton & Won 2000, Norton et al. 2006). TEA is a voxel-based scale, delay, sum and integrate beamforming algorithm originally developed for seismic imaging (Norton & Won 2000), although more recently its modification has been investigated for spatiotemporal mapping of cavitation activity resulting from the application of FUS (Gyöngy & Coussios 2010b).

To generate an image using TEA, one first defines a set of control points throughout a region of interest (ROI) over which the image reconstruction will take place. For each control point, the received signals from the hydrophone array are independently scaled, delayed, and summed together, creating the beamformed signal. An image is then generated by assigning each voxel a representative intensity calculated as the temporal mean of the beamformed signal intensity, which provides a measure of the emitted power from that particular voxel. It is worth noting that the beamforming can be performed either in the frequency (Salgaonkar et al. 2009, Haworth et al. 2012) or the time (Gyöngy & Coussios 2010b) domain. However, because the transcranial propagation of US is frequency dependent (Connor et al. 2002, Pichardo et al. 2011), we chose to work in the frequency domain.

For each control point-hydrophone pair, the phase and amplitude correction values for angular frequency ω are given by the reciprocal of the transfer function describing the propagation from a harmonic source located at the control point of interest to the corresponding hydrophone (Norton & Won 2000). Defining the transfer function for transcranial acoustic propagation from a source located within the brain at rm to the nth hydrophone of the array, Hn(rm; ω), as the ratio of the received signal amplitude to the source strength (see appendix):

| (1) |

an image is formed throughout a set of M control points from a set of N received signals as follows:

| (2) |

The second term in equation (2) is included to remove any D.C. bias from the image resulting from averaging an intensity, a positive-definite quantity, over time (Norton & Won 2000). In the case of a single point source located at rq, equation (2) yields:

| (3) |

which defines the point-spread function of the imaging system containing N hydrophones. Finally, all passive acoustic maps were normalized for comparison:

| (4) |

Computation of the receiver-specific skull corrections for image formation, namely Hn(rm; ω), was achieved by running the transcranial propagation model described in the appendix in reverse. Individually, each hydrophone was driven by a continuous wave excitation at the particular frequency of interest (ω) and the resulting phase and amplitude of the pressure at each control point within the imaging ROI were recorded, enabling calculation of the corresponding transfer functions. This is equivalent to measuring the received signal at each hydrophone due to a point source located at each of the control points, sequentially, assuming spatial reciprocity (Jackson & Dowling 1991).

2.4. Imaging Array Specifications

The centre of each transmit element in the 30 cm diameter hemispherical phased array (Song & Hynynen 2010) was considered as a potential receiver location when constructing hydrophone arrays for numerical simulation. Hydrophone arrays with element counts of 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024 and 1372 were simulated. For each array population fraction, multiple receiver configurations were simulated, allowing conclusions to be drawn based on different levels of sparsity. Sparse array configurations were generated by pseudo-randomly distributing the receiver elements over the entire aperture of the hemispherical array subject to two constraints. First, the hemispherical dome was subdivided evenly into four Cartesian quadrants, and it was required that each quadrant contained an equal number of receiver elements. Second, the standard deviation of the element locations in each Cartesian dimension for a valid sparse receiver configuration was required to be greater than or equal to the corresponding values of an array consisting of a hydrophone placed within each of the existing 1372 transmit elements. Both constraints were imposed to help ensure a more uniform distribution of elements (Yen et al. 2000).

2.5. Simulation Configurations

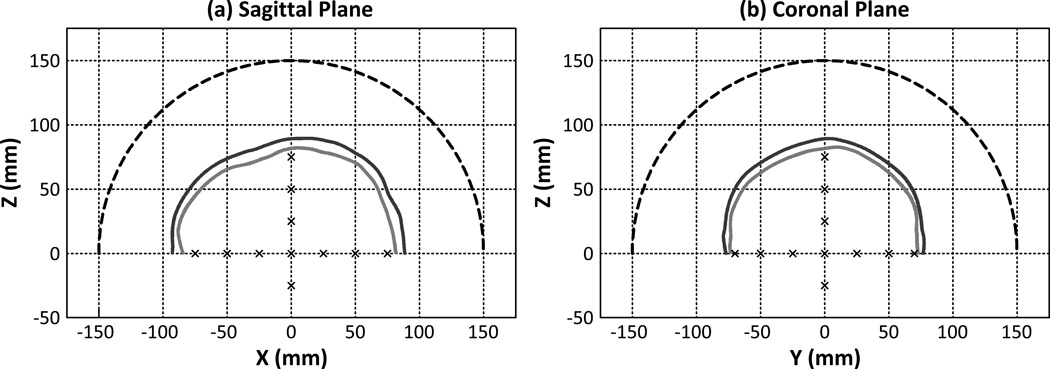

The origin of the simulation coordinates was set as the geometric focus of the hemispherical array. For one skull specimen (SKA), a total of 17 source locations inside the skull cavity spanning [−75 mm,75 mm] along the x-axis, [−70 mm,70 mm] along the y-axis, and [−25 mm,75 mm] along the z-axis were investigated. Figure 1 illustrates sagittal [figure 1(a)] and coronal [figure 1(b)] slices of the hemispherical array, the skull surfaces of SKA, and the simulated source locations. Two source frequencies (500 kHz and 1 MHz) within the relevant frequency range for transcranial FUS therapy were investigated. For each source location, a cubic volume of 20 × 20 × 20 mm3 centered about the source location was reconstructed with a uniform voxel size of (λ/12)3. For source locations where the imaging ROI extended into the skull bone, only voxels within the skull cavity were reconstructed. A corresponding set of simulations was conducted with identical source parameters but with the skull and brain tissue being replaced by water. This idealized water-path case was used as a control for comparison with the transcranial reconstructions. To examine skull-based variability, a subset of the aforementioned simulations were repeated over three CT datasets.

Figure 1.

Sagittal (a) and coronal (b) views of the hemispherical array, segmented skull surfaces (SKA), and simulated source locations.

Individual hydrophone arrays were evaluated based on various metrics. The −3 dB axial and mean lateral main lobe intensity beamwidths were extracted from each reconstructed volume, and were indicative of single-source resolvability. The minimum resolvable separation of two point sources was also investigated (De & Basuray 1972). It is worth noting that this distance depends strongly on the phase offset between the two emitting sources (Gyöngy 2010). Therefore, two distances were calculated: Rmin, the minimum resolvable separation independent of the inter-source phase offset, and R50, the separation with 50% predicted outcome of leading to two resolved sources, obtained through a probit analysis (Bliss 1935). For this set of simulations, 18 phase offsets spanning [0,2π], and 20 source separations about the geometric focus were simulated spanning [λ/20, λ] for sources along the the x- and y-axes, and [λ/10,2λ] for sources along the z-axis. The peak sidelobe ratio of each reconstructed volume was calculated as the ratio of the intensity of the largest sidelobe in the imaging ROI to the peak main lobe intensity. The image signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), defined here as the ratio of the main lobe intensity to the standard deviation of the background signal (all voxels whose distance from the main lobe intensity peak is greater than a wavelength), was also computed for each image reconstruction.

To evaluate the reconstruction algorithm’s sensitivity to noise, electronic noise taken from experimentally measured signals from our group’s current prototype system was added to the simulated RF signals from a 500 kHz source (sampled at 40 MHz) prior to image reconstruction. To quantify the noise level of each channel, the receiver SNR (SNRRCV) was calculated as the ratio of the mean signal power within a 40 kHz band surrounding the source frequency to the mean noise power throughout the remaining bandwidth of the received signal. Two levels of additive noise were investigated: a low noise case where the average receiver SNR over the imaging array (〈 SNRRCV〉) was 5, and a high noise case where 〈SNRRCV〉 = 1. The high noise case was designed to simulate a comparable 〈SNRRCV〉 to that observed experimentally from the receiver (2.5 mm diameter, 612 kHz center frequency, piezo-ceramic disks, DeL Piezo Specialties, LLC, West Palm Beach, FL, USA) signals measured following sonication (5 cycle bust, f = 306 kHz, 0.15 ≤ Focal Pressure (MPA) ≤ 0.35) of a sub-clinical concentration of Definity™ microbubbles (Lantheus Medical Imaging, North Billerica, MA, USA) diluted in saline (dilution ratio = 1:16384000) flowing within a thin-walled tube phantom with a human skullcap positioned between the phantom and the dual-mode array. The low noise case was designed to simulate the same experimental conditions, but with a larger concentration (dilution ratio = 1:256000) of Definity™. The additive noise was uncorrelated between hydrophones. The noisy signals were band-pass filtered with a 4th order Butterworth filter (300 kHz bandwidth centered about the source frequency) in MATLAB prior to beamforming. For this set of simulations, the beamforming was performed in the time domain. Images generated with integration times (Tint) of 10 µs and 40 µs were investigated, corresponding to 5 and 20 acoustic cycles at 500 kHz, respectively.

3. Results

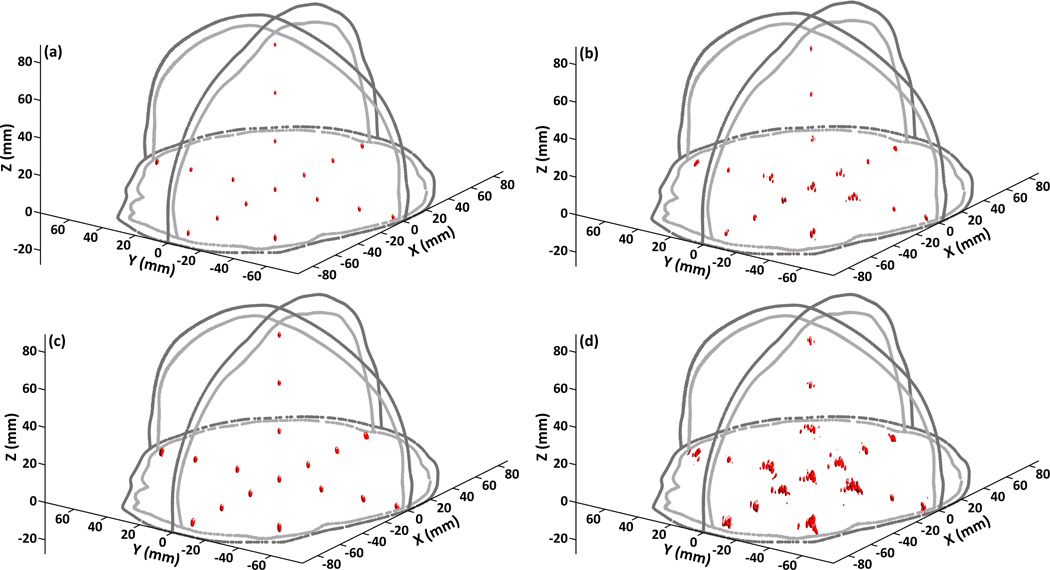

Figure 2 shows the −3 dB [figures 2(a) and 2(b)] and −6 dB [figures 2(c) and 2(d)] intensity isosurfaces extracted from passive acoustic maps of a 500 kHz point source at each of the 17 simulated source locations within the skull cavity of SKA, reconstructed with a hydrophone array containing 128 elements. The volume enclosed by the smooth −3 dB (−6 dB) isosurfaces corresponds to the region where the image intensity is higher than or equal to 50% (25%) of the peak main lobe intensity. Passive acoustic maps generated with [figures 2(a) and 2(c)] and without [figures 2(b) and 2(d)] CT-based skull aberration corrections included in the image reconstruction are shown. When skull corrections are not incorporated into the image reconstruction, significant distortions in the shape and location of the reconstructed focal volumes result, in comparison to the control water-path case (data not shown), and in some cases multiple foci can appear. These distortions are particularly apparent in the plot of −6 dB isosurfaces [figures 2(d)]. However, taking the appropriate skull corrections into account leads to well-defined ellipsoidal focal volumes centered about the corresponding source locations that match closely with the water-path case (data not shown).

Figure 2.

−3 dB [(a) and (b)] and −6 dB [(c) and (d)] intensity isosurfaces of passive acoustic maps at each of the 17 source locations investigated within the skull cavity of SKA for a 500 kHz source with [(a) and (c)] and without [(b) and (d)] CT-based skull corrections included in the reconstruction algorithm. The hydrophone array contained 128 elements. The light and dark gray lines represent the inner and outer skull contours of SKA, respectively.

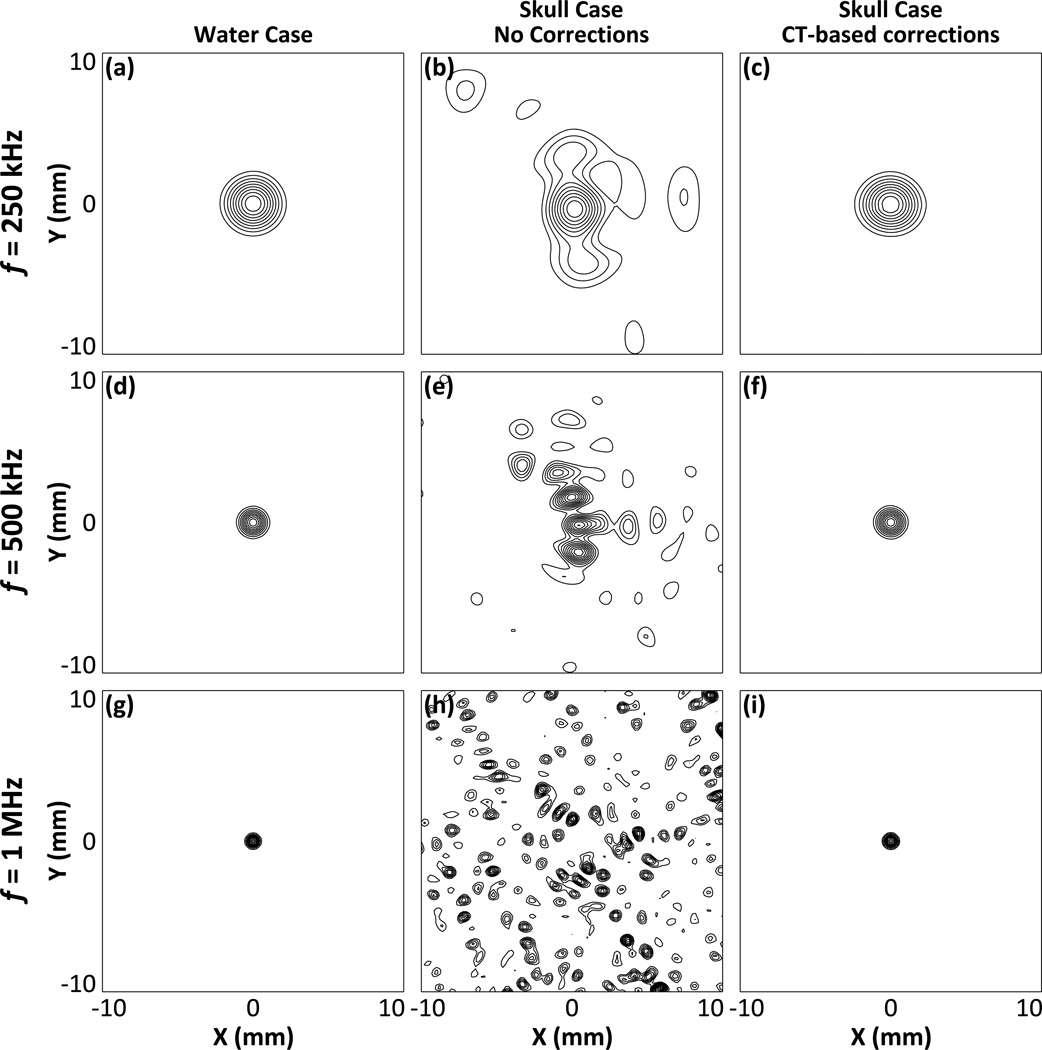

Figure 3 shows passive acoustic maps in the lateral plane at the array’s geometric focus for a point source emitting at 250 kHz [figures 3(a), 3(b), and 3(c)], 500 kHz figures 3(d), 3(e), and 3(f)], and 1 MHz [figures 3(g), 3(h), and 3(i)], reconstructed using a hydrophone array containing 128 elements. Images from the control water-path case [figures 3(a), 3(d), and 3(g)] are shown and compared to transcranial reconstructions both with [figures 3(c), 3(f), and 3(i)] and without [figures 3(b), 3(e), and 3(h)] the incorporation of CT-based skull corrections into the TEA beamforming algorithm. The passive acoustic maps generated using traditional TEA (i.e. no skull corrections) are severely distorted by the presence of a human skull bone between the source field and the imaging array, particularly as the source frequency is increased. However, by incorporating CT-based skull corrections into TEA, image reconstructions comparable to the control water-path case could be restored.

Figure 3.

Normalized passive acoustic maps of a 250 kHz [(a), (b), and (c)], 500 kHz [(d), (e), and (f)], and 1 MHz [(g), (h), and (i)] point source located at the geometric focus of the array, reconstructed in water [(a), (d), and (g)], through a human skullcap (SKA) without skull corrections [(b), (e), and (h)], and through a human skullcap (SKA) using CT-based skull corrections [(c), (f), and (i)]. The hydrophone array contained 128 elements. Contours are shown at 10% intervals.

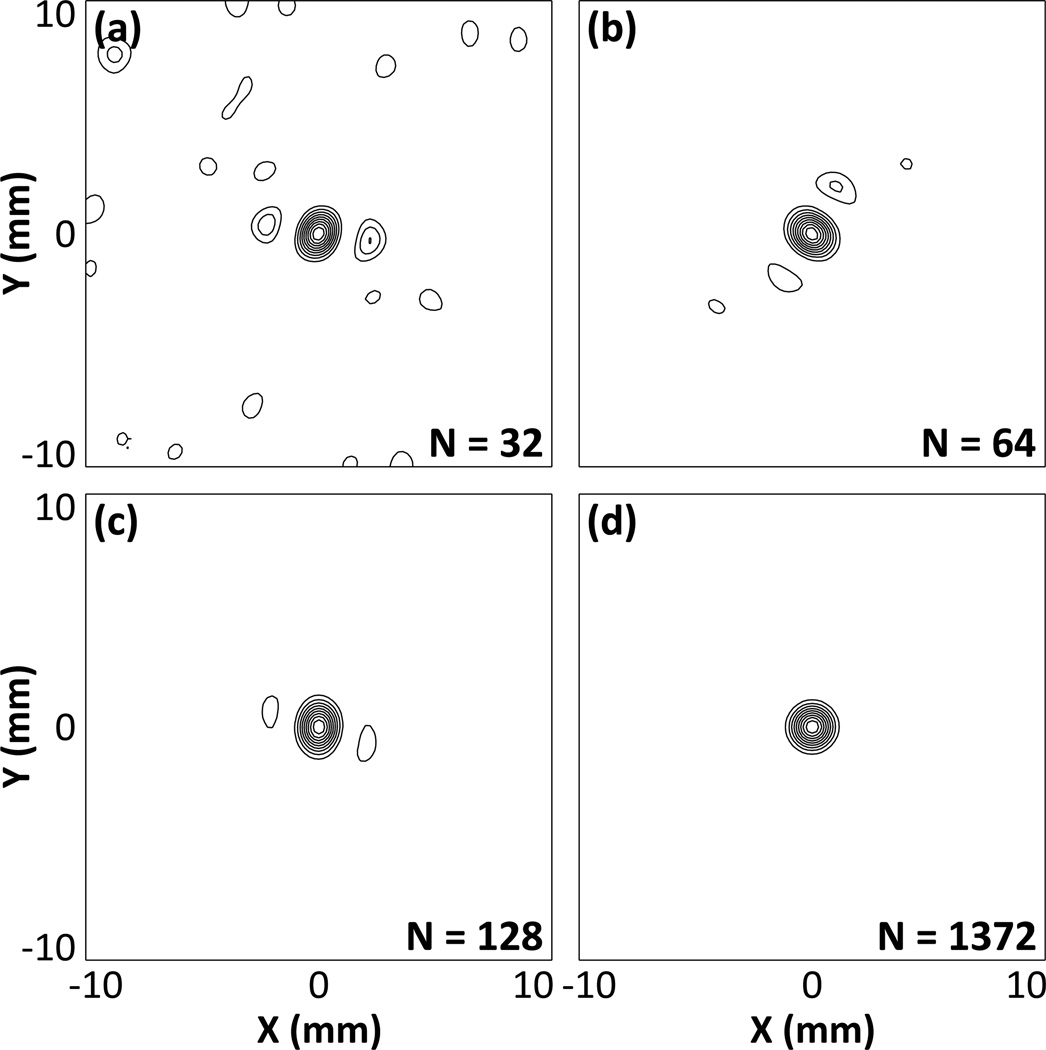

Figure 4 qualitatively demonstrates the dependence of the formation of passive acoustic maps on the number of receiver elements in the hemispherical imaging array. Images of a 500 kHz point source located at the array’s geometric focus are displayed in the lateral plane reconstructed using hydrophone arrays containing 32 [figure 4(a)], 64 [figure 4(b)], 128 [figure 4(c)], and 1372 [figure 4(d)] elements. As the number of receiver elements used for reconstruction is increased, the peak sidelobe level and general background signal in the resulting image is diminished, while the size of the main lobe appears to be less sensitive to array sparsity.

Figure 4.

Normalized transcranial (SKA) passive acoustic maps of a simulated 500 kHz point source located at the geometric focus of the array for hydrophone arrays containing 32 (a), 64 (b), 128 (c), and 1372 elements (d). Contours are drawn at 10% intervals.

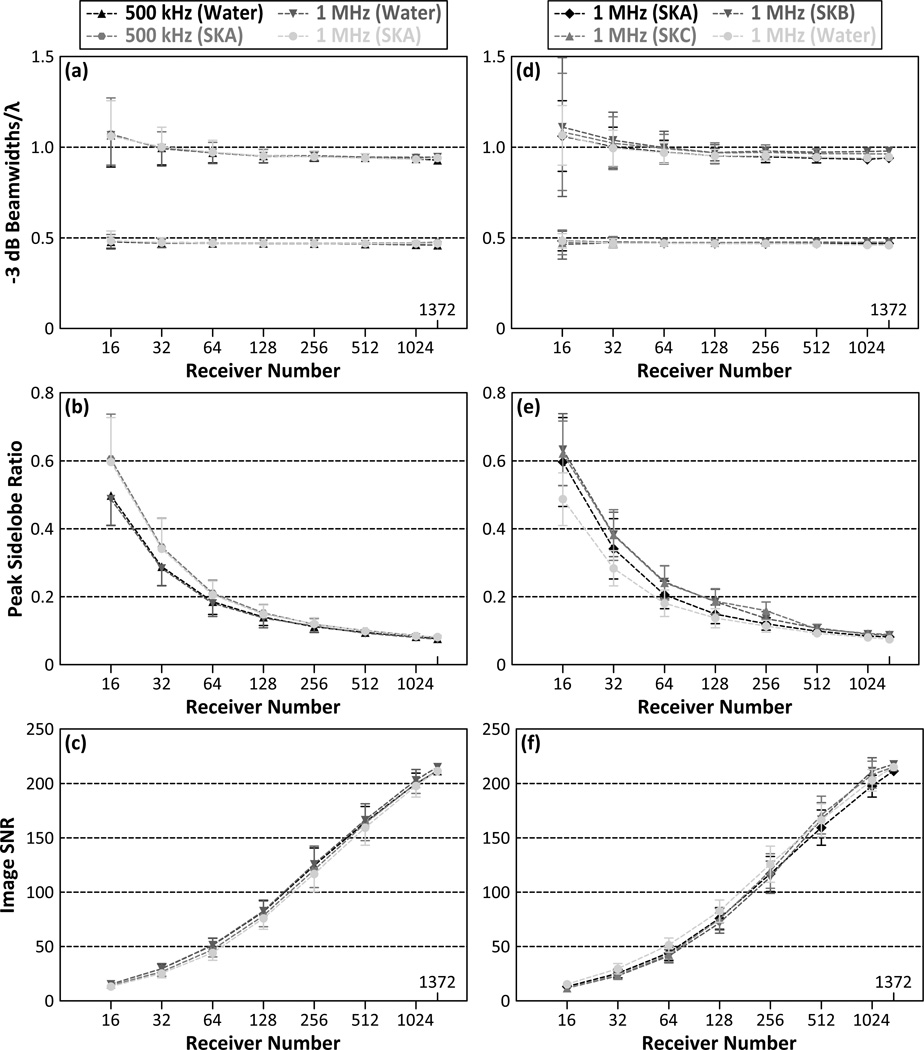

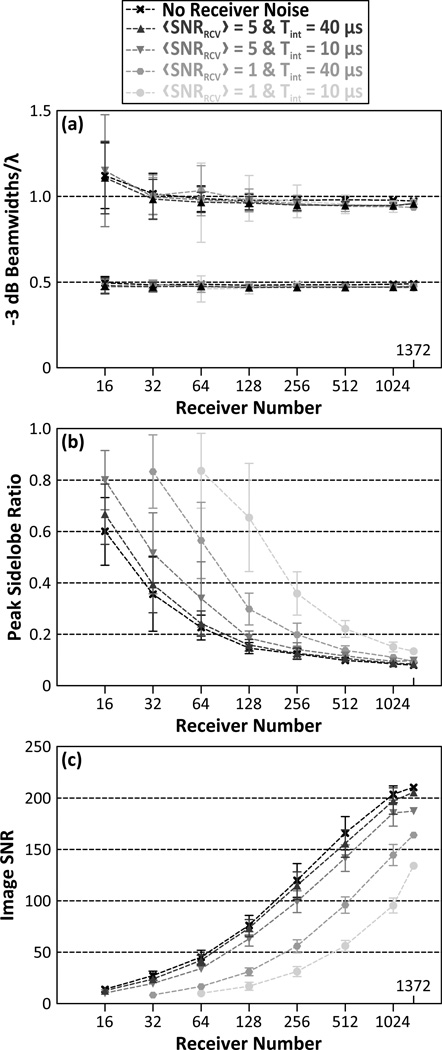

Figure 5 quantifies the aforementioned trends by plotting the −3 dB lateral and axial main lobe beamwidths [figure 5(a)], peak sidelobe ratio [figure 5(b)], and image SNR figure 5(c)] as a function of the number of receiver elements for both 500 kHz and 1 MHz point sources located at the geometric focus of the array. Results for both the transskull (SKA) and water-path cases are shown. The peak sidelobe ratio was found to decrease with increasing number of elements from 60.6%±13.1% with 16 elements down to 8.0% with 1372 elements for transcranial reconstruction of a 500 kHz source. Similar trends for image SNR were obtained at 1 MHz. For sparse hydrophone arrays with receiver element numbers of 128 and greater, the mean peak sidelobe level for transcranial image formation was within 1.3% of the control water-path case, while for arrays with fewer than 128 elements the results for the transcranial case are worse, with a 10.9% greater peak sidelobe ratio than the water-path case with only 16 elements. The −3 dB main lobe beamwidths increased linearly with the source wavelength near the geometric focus of the array, and are not substantially affected by array sparsity. The axial beamwidth is appoximately a factor of two larger than its lateral counterpart, which is expected due to the hemispherical geometry of the array. The image SNR was found to increase monotonically with receiver element number, achieving half the value obtained with 1372 elements between 128 and 256 elements. Similar trends were displayed in both the transcranial and water-path cases for both source frequencies investigated. Figures 5(d), 5(e), and 5(f) plot the same metrics shown in figures 5(a), 5(b), and 5(c) for the three different skull specimens (SKA, SKB, SKC) and the water-path control for 1 MHz sources. As expected, while there are slight differences in the results from different skull specimens, the general trends from SKA still hold. Similar results were obtained in these multi-skull simulations for 500 kHz sources (data not shown).

Figure 5.

−3 dB axial (top curves) and lateral (bottom curves) main lobe beamwidths scaled by the corresponding wavelength (a), peak sidelobe ratio (b), and image SNR (c) as a function of receiver element number for 500 kHz and 1 MHz point sources located at the geometric focus of the array. The same metrics are plotted for 1 MHz sources in [(d), (e), and (f)] for three different skull specimens (SKA, SKB, SKC). Transcranial and water-path reconstruction cases are shown. The results shown in the left (right) column are averaged over 500 (100) receiver configurations per population fraction. Error bars indicate one standard deviation for the different receiver configurations.

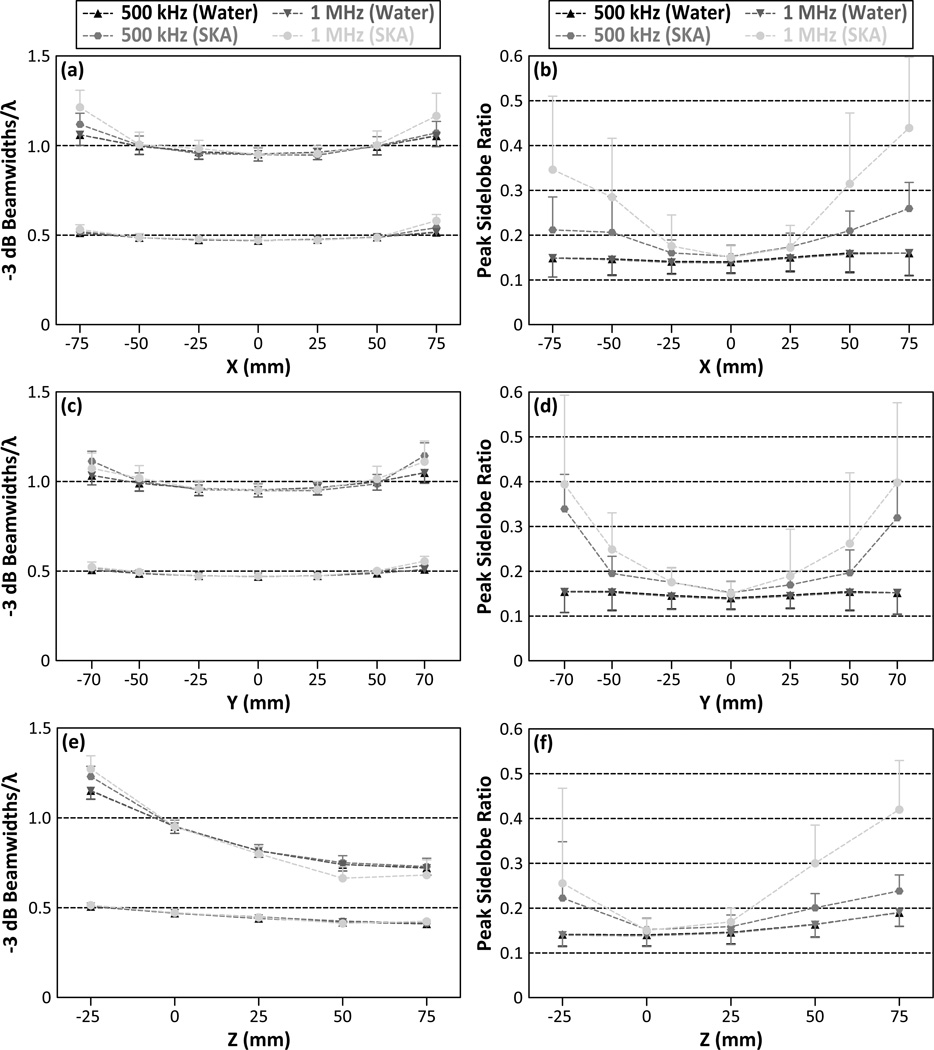

Figures 6(a), 6(c), and 6(e) show the −3 dB lateral and axial main lobe beamwidths as a function of the source location for both 500 kHz and 1 MHz point sources and hydrophone arrays containing 128 elements. Both the lateral and axial main lobe beamwidths increased as the source location was moved laterally and inferiorly away from the array’s geometric focus. The trends for the transcranial case differed from the control water-path case only at the simulated source locations that were farthest from the array’s geometric focus, and thus closest to the inner skull surface. Figures 6(b), 6(d), and 6(f) show the peak sidelobe ratio for the same simulated reconstructions. Peak sidelobe ratios generally increased as the source location was moved away from the array’s geometric focus. For the water-path reconstructions, the peak sidelobe ratio was relatively constant over all simulated source locations, remaining between 13.8% and 19.0% for both 500 kHz and 1 MHz sources. However, in the transskull reconstructions, the peak sidelobe ratios were further increased as the source location was placed closer to the inner skull surface, particularly as the source frequency was increased. For example, at 500 kHz a peak sidelobe ratio of 33.9% ± 7.7% was observed for sources located at r = (0,−70, 0) mm, while at 1 MHz a ratio of 43.9% ± 15.8% was observed for sources located at r = (75, 0, 0) mm.

Figure 6.

−3 dB axial (top curves) and lateral (bottom curves) main lobe beamwidths scaled by the corresponding wavelength [(a), (c), and (e)] and peak sidelobe ratio [(b), (d), and (f)] as a function of source location for 500 kHz and 1 MHz point sources. Transcranial (SKA) and water-path reconstruction cases are shown. The results are averaged over 500 hydrophone arrays each containing 128 elements. One-sided error bars indicate one standard deviation for the different receiver configurations.

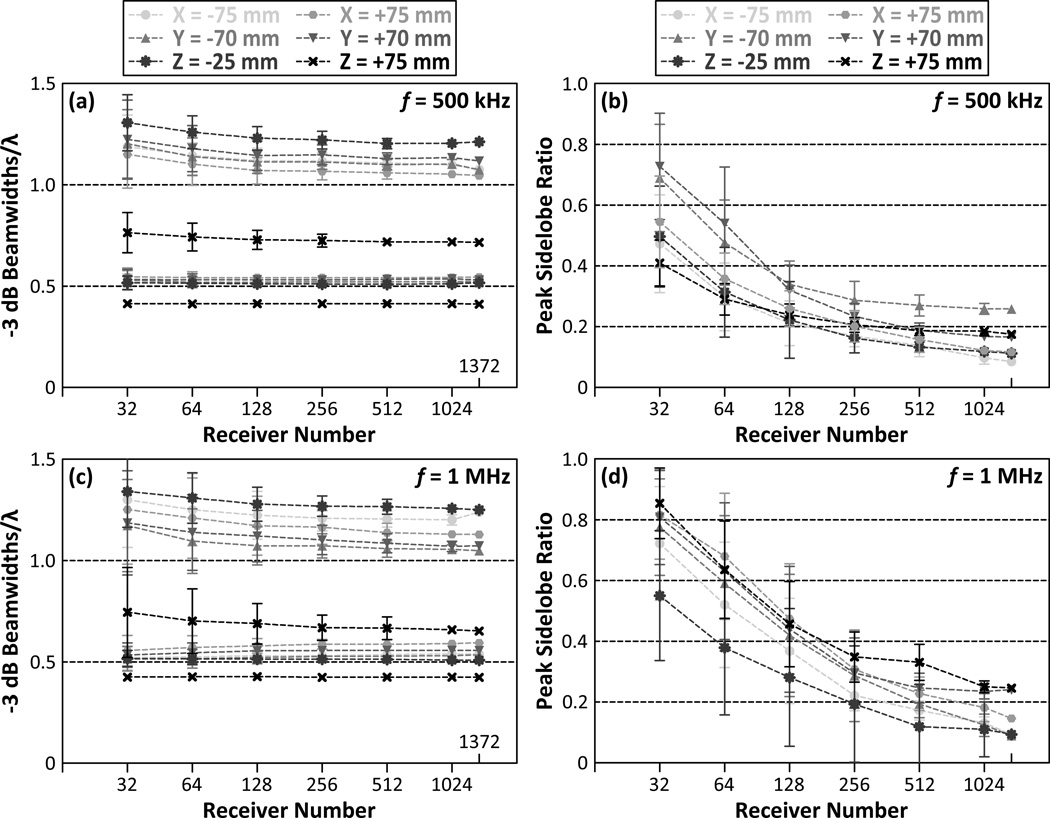

Figure 7 plots the dependence of the formation of passive acoustic maps on the number of receiver elements in the hemispherical imaging array for 500 kHz [figures 7(a) and 7(b)] and 1 MHz [figures 7(c) and 7(d)] sources at the simulated source locations that were farthest from the array’s geometric focus. At these locations, for sparse receiver arrays containing 16 elements, the magnitudes of the largest sidelobes in the reconstructed volumes were greater than the main lobe intensities for certain receiver configurations. As a result, the correct source locations in these reconstructed images were indiscernible, and therefore these results have been omitted from Figure 7. Although the −3 dB main lobe beamwidths are location-dependent, similar to the case at the geometric focus (see figure 5(a)) they are not substantially affected by array sparsity [figures 7(a) and 7(c)]. For hydrophone arrays with 256 receivers or greater, the peak sidelobe ratio was less than 28.6%±6.3% (33.2%±5.0%) for 500 kHz (1 MHz) point sources located as close as 2.7 mm to the inner skull surface [figures 7(b) and 7(d)].

Figure 7.

−3 dB axial (top curves) and lateral (bottom curves) main lobe beamwidths scaled by the corresponding wavelength [(a) and (c)], and peak sidelobe ratio [(b) and (d)] as a function of receiver element number for 500 kHz and 1 MHz point sources located at points farthest away from the array’s geometric focus. Results from the transcranial (SKA) reconstruction case are shown. The results are averaged over 500 receiver configurations per population fraction. Error bars indicate one standard deviation for the different receiver configurations.

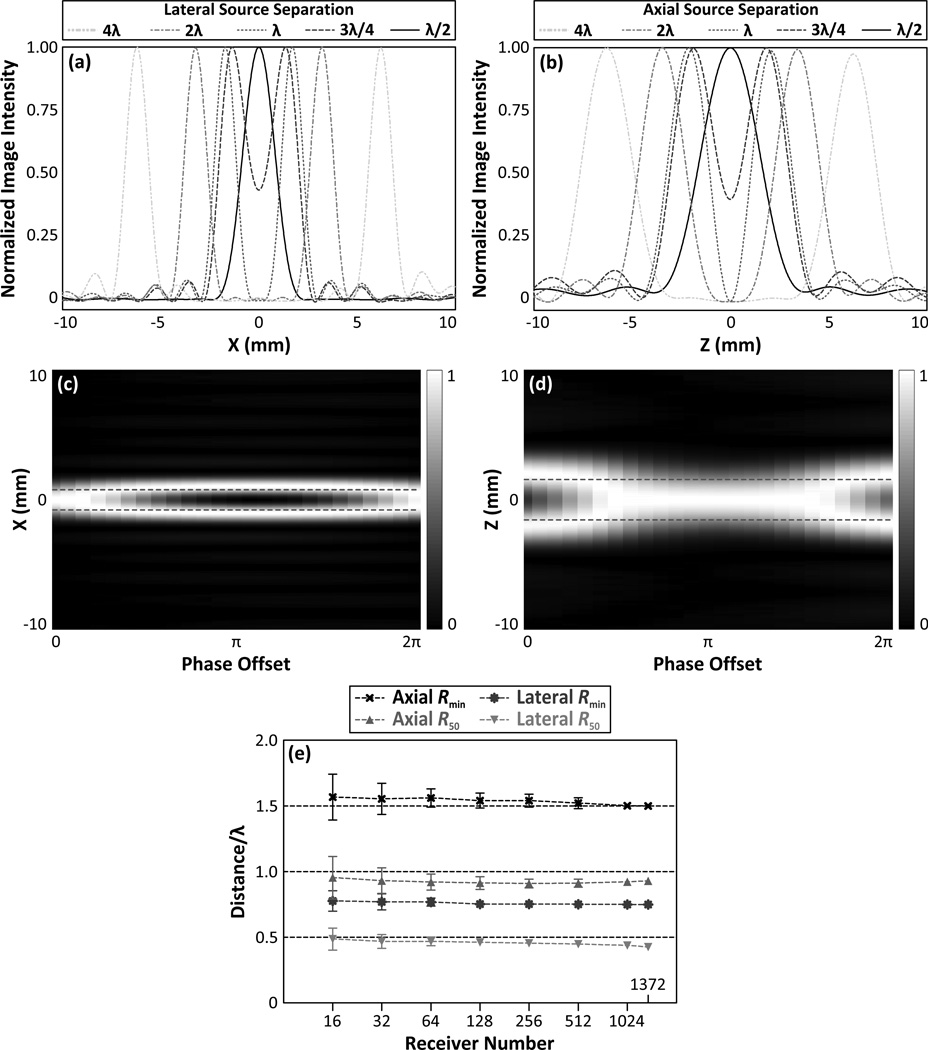

Figure 8 shows results from the two-source study conducted at 500 kHz. Lateral [figures 8(a)] and axial [figures 8(b)] line profiles connecting two in-phase sources of equal amplitude, separated by varying distances about the array’s geometric focus are shown. Plots of lateral [figure 8(c)] and axial [figure 8(d)] line profiles for two equal amplitude sources with fixed locations but with varying phases illustrates the dependence of the imaging technique’s two-source resolution on the inter-source phase offset (Gyöngy 2010). Figure 8(e) plots the two-source resolution as a function of the number of receiver elements for sources separated laterally and axially about the geometric focus of the array. Similar to the −3 dB single source main lobe beamwidths (see [figure 5(a)]), neither Rmin nor R50 are substantially affected by array sparsity. For imaging arrays with 128 receiver elements, Rmin and R50 are given by 0.75λ ± 0.03λ (1.54λ ± 0.06±) and 0.46± ± 0.03± (0.91± ± 0.05±), respectively, for laterally (axially) separated sources.

Figure 8.

Line profiles of the transcranial (SKA) passive acoustic maps of two in-phase, equal amplitude 500 kHz sources separated laterally (a) and axially (b) about the geometric focus of the array by various distances. Line profiles of the transcranial passive acoustic maps of two 500 kHz sources separated by λ/2 (1.55 mm) laterally (c) and λ (3.09 mm) axially (d) about the array’s geometric focus as a function of the inter-source phase offset (dashed red lines indicate actual source locations). The hydrophone array for plots (a), (b), (c), and (d) contained 128 elements. Axial and lateral axial Rmin and R50 distances as a function of receiver element number for transcranial image reconstruction (e). The results are averaged over 100 receiver configurations per population fraction. Error bars indicate one standard deviation for the different receiver configurations.

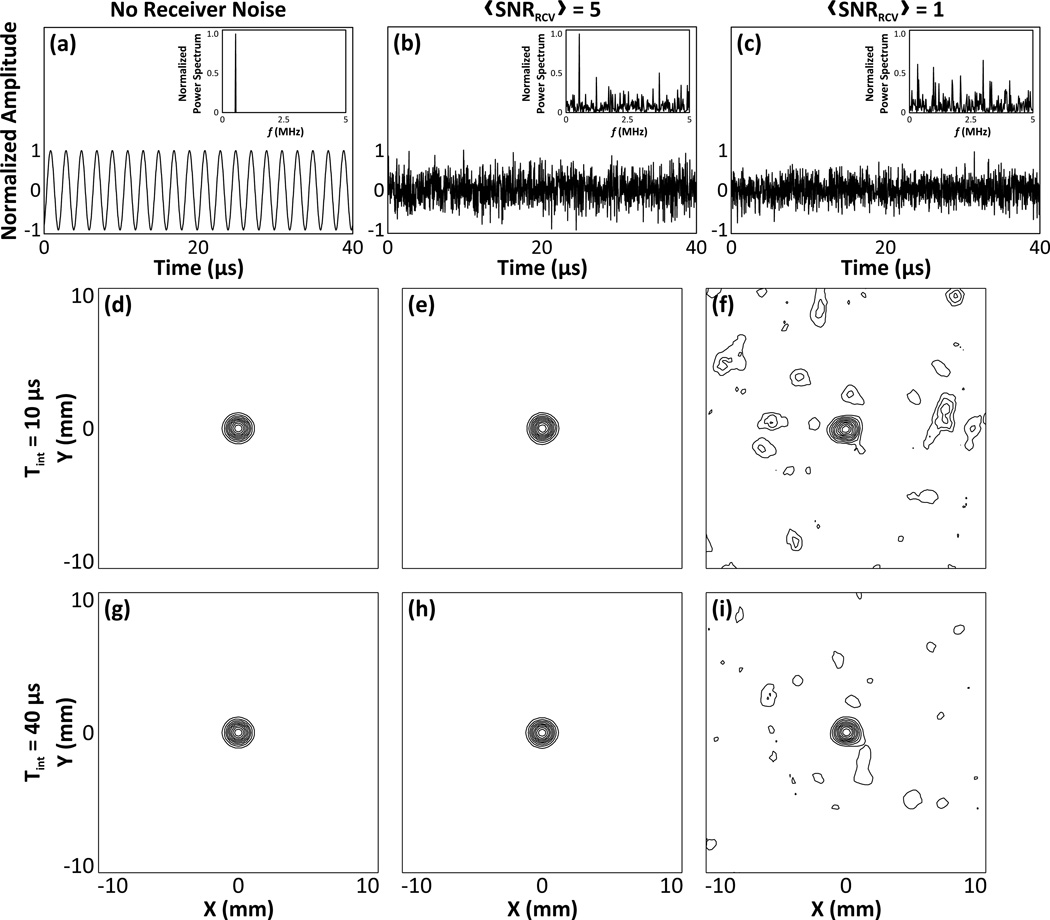

Figure 9 qualitatively demonstrates the dependence of the image quality of passive acoustic maps on the addition of electronic noise to the received signals of a 500 kHz source located at the array’s geometric focus. Plots of a single channel input signal for the no noise [figure 9(a)], low noise [figure 9(b)], and high noise [figure 9(c)] cases are shown, with their corresponding power spectra displayed as insets. The addition of both amounts of noise precluded successful image formation without prior band-pass filtering of the received data. Image reconstructions obtained by beamforming the filtered data from a hydrophone array containing 128 elements using integration times of 10 µs [figures 9(d), 9(e), and 9(f)] and 40 µs [figures 9(g), 9(h), and 9(i)] are shown. In the low noise case, both integration times led to image reconstructions which closely matched the noiseless control case. In the high noise case, both integration times led to successful image formation, however there was a noticeable increase in the sidelobe levels and general background signal, particularly for images generated with the shorter integration time.

Figure 9.

Examples of single channel signals due to a 500 kHz source located at the array’s geometric focus with no noise (a), and with low (b) and high (c) amounts of additive noise. The normalized power spectra of each case is plotted as an inset. Transcranial (SKA) passive acoustic maps generated by beamforming the filtered signals with an integration time of 10 µs for the no noise (d), low noise (e), and high noise (f) cases are shown. Corresponding images generated with an integration time of 40 µs are shown in (g), (h), and (i). All of the images were reconstructed with a hydrophone array containing 128 elements. Contours are drawn at 10% intervals.

Figure 10 quantifies the reconstruction algorithm’s sensitivity to noise by plotting the −3 dB lateral and axial main lobe beamwidths [figure 10(a)], peak sidelobe ratio [figure 10(b)], and image SNR [figure 10(c)] as a function of the number of receiver elements for a 500 kHz point source located at the geometric focus of the array, with and without the addition of electronic noise to the received signals prior to image formation. The signals were band-pass filtered prior to beamforming. Each metric was evaluated for both the low and high noise cases, and for integration times of 10 µs and 40 µs. The addition of both amounts of noise to the pre-beamformed data did not affect the size of the −3 dB main lobe beamwidths in the resulting passive acoustic maps. However, the peak sidelobe level and image SNR values were substantially altered relative to the control noiseless case, particularly in the high noise case. For both noise cases, the longer integration time (20 acoustic cycles) resulted in improved image quality (i.e. reduced peak sidelobe ratio and improved image SNR) relative to the shorter integration time (5 acoustic cycles).

Figure 10.

−3 dB axial (top curves) and lateral (bottom curves) main lobe beamwidths scaled by the corresponding wavelength (a), peak sidelobe ratio (b), and image SNR (c) as a function of receiver element number for a 500 kHz point source located at the geometric focus of the array. Results from transcranial (SKA) reconstructions for each combination of receiver noise level and integration time are shown. The results are averaged over 50 receiver configurations per population fraction. Error bars indicate one standard deviation for the different receiver configurations.

4. Discussion

This numerical study showed that the presence of a human skull between a hemispherical imaging array and an acoustic source field severely distorts the acoustic maps generated using a conventional passive beamforming algorithm (Norton & Won 2000), particularly at higher source frequencies, where the path length in the skull bone is large as compared to the corresponding acoustic wavelength. However, with the inclusion of skull-specific aberration corrections into the reconstruction algorithm, calculated from a CT-based transcranial US propagation model, passive acoustic maps comparable to the idealized water-path case could be restored. In addition, acceptable image quality was obtainable using sparse arrays of pseudo-randomly distributed receiver elements over a hemispherical aperture, reducing the technical complexity associated with the fabrication and electronics of such a system. Transcranial PAM would help improve the safety of microbubble-mediated FUS brain treatments such as FUS-induced BBB disruption (Hynynen et al. 2001) and sonothrombolysis (Medel et al. 2009, Wright et al. 2012), by allowing for the spatiotemporal monitoring of cavitation activity within the skull cavity during the treatments.

The obtainable spatial resolution of such a system, based on the computed Rmin values which represent a worst-case scenario, was found to be approximately 1.2 mm/f (MHz) laterally and 2.4 mm/f (MHz) axially over a wide range of receiver element numbers (see [figure 8(e)]). For source frequencies near 1 MHz, these values are comparable to the voxel sizes currently used during MRI thermometry for monitoring thermal FUS brain treatments (McDannold et al. 2010). The choice of source emission frequency, and by extension the transmit pulse frequency, represents a trade-off between the high resolution achievable with higher frequencies and the diminished received signal amplitude due to the increased attenuation of the skull bone at higher frequencies (Fry & Barger 1978).

The modified TEA beamforming algorithm was shown to perform well under conditions of significant receiver noise. It is noteworthy that source maps could be extracted from signals that are essentially invisible in the receiver noise in the time domain [figures 9(b), 9(e), and 9(h)], and, moreover, from signals whose source peak in the corresponding power spectrum is suppressed relative to the noise [figures 9(c), 9(f), and 9(i)]. This is encouraging due to the small amplitude signals expected from cavitating bubbles from within the brain (O’Reilly & Hynynen 2010). The integration time can be increased to improve the overall image quality of passive acoustic maps, assuming signal is present within the integration window, but at the expense of temporal resolution.

Currently, FUS-induced BBB disruption has been safely controlled in pre-clinical studies by processing cavitation activity obtained from the therapeutic focus using single-element passive cavitation detectors (O’Reilly & Hynynen 2012). In the future, through the use of transcranial PAM, similar algorithms could be expanded to incorporate signals from the whole brain to control the sonication pattern such that the desired microbubble activity is reached within the therapeutic target volume, and to confirm that cavitation, and its associated bioeffects, are localized at the therapeutic focus.

It is worth noting that due to the complex, frequency-dependent manner with which US propagates through skull bone, when beamforming broadband signals for PAM in the brain, frequency-dependent skull corrections should be employed. This is possible due to established relationships of the skull’s acoustical properties with acoustic frequency (Clement & Hynynen 2002b, Connor et al. 2002, Pichardo et al. 2011), but will result in an increased computational time. On the other hand, it may be possible to perform transcranial PAM without CT-based skull corrections at low enough source frequencies, where skull aberrations are reduced (see figure 3(b)) due to the short path length in the skull in relation to the acoustic wavelength (Yin & Hynynen 2005).

The ability of PAM to generate spatial maps of microbubble activity over a large volume allows off-focus events to be monitored. This could be used, for example, to detect unwanted secondary foci during the treatments due to the formation of standing waves within the skull cavity (Baron et al. 2009). Another potential application of transcranial PAM is for monitoring cavitation-enhanced ablation in the brain (McDannold et al. 2006a). Acoustic cavitation can accelerate heating rates, allowing for a larger volume of ablated tissue in a relatively shorter time than would be achieved in the absence of cavitation (Hynynen 1991, Sokka et al. 2003). Additionally, by reducing the required acoustic power, the use of US contrast agents could facilitate treatment of near-skull regions of the brain that are untreatable with thermal ablation due to risks associated with skull heating (Pulkkinen et al. 2011). Although the peak sidelobe ratio was found to increase at superficial sites relative to the center of the skull cavity (see [figures 6(b), 6(d), and 6(f)]), this study demonstrated that with a hemispherical hydrophone array with greater than or equal to 128 receiver elements, acoustic sources within a few millimeters of the inner skull surface could be localized with a peak sidelobe ratio of less than −3 dB, on average (see [figures 7(b) and 7(d)]). Thus, transcranial PAM could be used to monitor cavitation-enhanced ablation of near-skull regions within the brain, though further investigations are required in order to fully characterize the effective area of treatment within the brain using such an approach.

5. Conclusion

This study investigated passive acoustic mapping of source fields through the human cranium by including CT-based skull-specific aberration corrections into TEA, a conventional passive beamforming algorithm, employed on data received from sparse hemispherical hydrophone arrays. Results show that the peak sidelobe ratio and SNR of the reconstructed images increased and decreased, respectively, as the number of receiver elements was diminished, while the main lobe beamwidths and resolvable two-source separations were not substantially affected. Peak sidelobe ratios were found to increase for sources located closer to the inner skull surface, however, imaging arrays with 128 receiver elements or greater were able to successfully (peak sidelobe ratio < −3 dB) image sources within a cylindrical volume of 14 cm in diameter and 10 cm in height inside the skull cavity. The reconstruction algorithm was shown to be robust to the presence of electronic noise in the received signals, provided the source frequency of interest was extracted through band-pass filtering prior to beamforming. Image reconstruction of the filtered signals with short integration times (< 50 µs) led to smooth and accurate source field maps, demonstrating the high temporal resolution of PAM. The choice of receiver element number represents a trade-off between the benefits of improved image quality and increased imageable volume and the drawbacks of increased fabrication complexity with a larger number of elements. Finally, this study has demonstrated that the development of a sparse, hemispherical receiver array could make transcranial microbubble-mediated FUS therapies more practical, by providing a real-time method for monitoring and control to be used in future brain treatments. Future work in this area will be focused on the validation of the proposed reconstruction algorithm through experimental studies with ex-vivo human skull caps and a prototype dual-mode hemispherical phased array.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Aki Pulkkinen and Ben Lucht for their technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Health Institute under grants no. EB003268 and no. EB009032, the Canada Research Chair program, Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarships in Science and Technology (Jones), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Jones).

Appendix

For a given skull specimen, the volume between the skull and the array was filled with water and the volume enclosed by the inner skull was filled with brain tissue. Both water and brain tissue were treated as homogeneous fluid media whose material properties are provided in table A1. The volume confined by the inner and outer skull surfaces was treated as a heterogeneous solid, using the CT-based density maps described above, and supported the propagation of both longitudinal and shear waves. The skull bone’s longitudinal acoustical parameters were estimated by interpolating the empirical relationships presented in (Pichardo et al. 2011), which relate the longitudinal speed of sound and attenuation coefficient of human skull bone to its material density and the US frequency. As there currently exists no analogous data for the shear acoustical parameters of skull bone, the following approximations were used: cs(ρ, f) = 1400/2550) · cl(ρ, f) and αs(ρ, f) = (90/85) · αl(ρ, f), as done in (Song et al. 2012).

Table A1.

Material parameters of water and brain tissue used in the simulation model. Here ρ is the density, cl is the longitudinal sound of speed, and αl is the longitudinal attenuation coefficient. Parameters chosen based on the values presented in (Duck 1990).

| Material Parameter | Water | Brain Tissue |

|---|---|---|

| ρ (kg m−3) | 1000 | 1030 |

| cl (m s−1) | 1500 | 1545 |

| αl (Np m−1 MHz−1) | 0 | 4 |

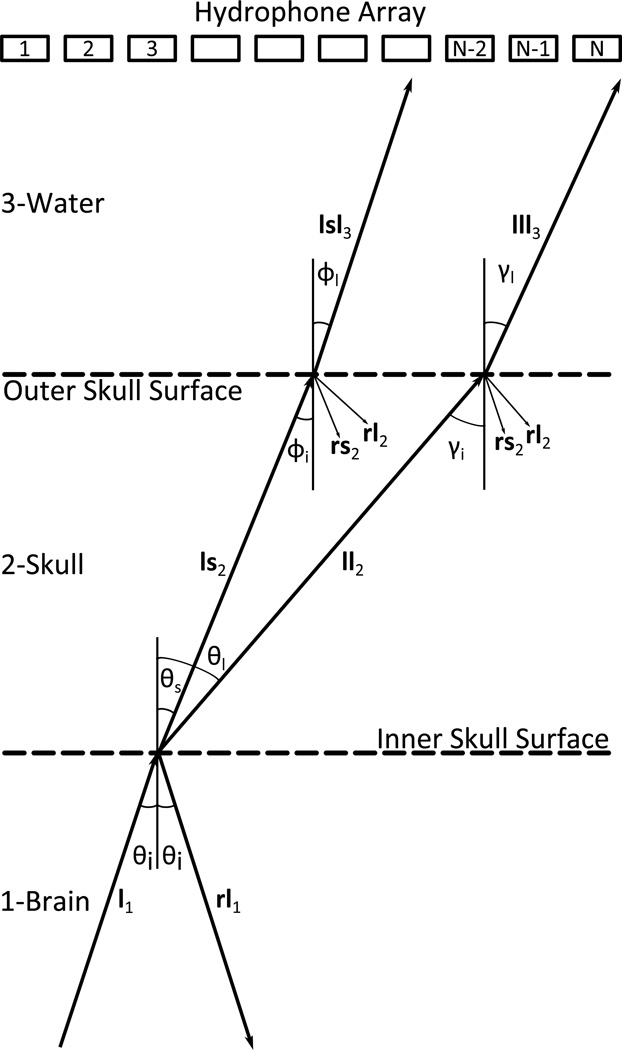

Figure A1 illustrates the 3-layered propagation of sound from an acoustic source located within the brain to a remote array of acoustic receivers submersed in water. The acoustic source generates a longitudinal wave l1 that propagates within the brain until it reaches the inner skull surface. A longitudinal wave l1 incident upon the inner skull surface generates both a longitudinal wave ll2 and a shear wave ls2 within the skull medium. Each wave propagates through the skull on an independent path, determined by Snell’s law, and reaches the outer skull surface. At the outer skull surface two longitudinal components are transmitted into the water medium: lll3 due to pure longitudinal transmission, and lsl3 due to shear mode conversion. The reflected components are included in figure A1 for completeness, but were not considered in the numerical model. Multiple internal reflections within the skull bone were not modeled as it has been shown that their presence does not significantly affect the acoustic signal detected after propagation through a human skull (Clement et al. 2001).

Figure A1.

Schematic of the 3-layered sound transmission through the skull. Sound is transmitted from medium 1 (brain) to medium 3 (water) through medium 2 (skull). The hydrophone array and skull surfaces are shown as parallel for illustrative purposes only. A longitudinal wave incident upon the inner skull surface will generate one reflected longitudinal wave and two transmitted waves: one longitudinal and one shear. The transmitted waves follows independent paths to the outer skull surface, at which point each component will give rise to a transmitted longitudinal wave and two reflected waves: one longitudinal and one shear.

The signal amplitude measured by the nth receiver located in the water medium due to a harmonic point source located at rq within the brain medium, denoted by Sn(rq; ω), is given by the integral of the transmitted pressure over its surface area (Harris 1981). Numerically, this can be expressed as:

| (A.1) |

where is the total pressure amplitude at sub-element i3 of the nth receiver with differential surface area dsn,i3. The receivers were modeled as circular pistons with a diameter of 2.48 mm, equivalent to the active diameter of receivers previously constructed within our lab (O’Reilly & Hynynen 2010). Each receiver was subdivided into N3 quadrilaterals no larger than λ/12 in any dimension.

The total pressure amplitude is given by the sum of both transmitted waves:

| (A.2) |

where and are the complex pressure amplitudes resulting from pure longitudinal transmission and mode conversion, respectively. The pressure amplitude is given by:

| (A.3) |

where the inner and outer skull surfaces are composed of N1 and N2 sub-elements, respectively. The coefficient Q(rq; ω) represents the complex source strength (in units of kg s−2) of a harmonic point source located at rq. The propagation coefficients due to longitudinal propagation from the source located at rq to the inner skull surface, from the inner skull surface to the outer skull surface, and from the outer skull surface to sub-element i3 of the nth receiver are denoted, respectively, by , and . The coefficients and , given by:

| (A.4) |

and

| (A.5) |

model longitudinal US propagation between fluid-solid and solid-fluid media, respectively (Pichardo & Hynynen 2007). The complex longitudinal wavenumber of medium m (m = 1,2,3 for the brain, skull, and water layers, respectively) is defined as klm = ω/clm − jαlm, where ω = 2πf is the angular frequency, clm and αlm are the longitudinal speed of sound and attenuation coefficient of medium m, respectively, and is the imaginary unit. The density of medium m is indicated by the coefficient ρm. The Cartesian distance between the surface elements im and im+1 is indicated by |rim+1 − rim|, while θq→i1 and γi1→i2 represent the incident angle of a longitudinal wave reaching the inner and outer skull surface, respectively. For reference, the angles θq→i1 and γi1→i2 in equations A.4 and A.5 are represented in figure A1 by θi and γi, respectively. The coefficient dsim indicates the surface area of the element im. The coefficients and are the particle velocity transmission coefficients for longitudinal transmission at fluid-solid and solid-fluid interfaces, respectively.

The transmitted sound from the outer skull surface to sub-element i3 of the nth receiver is calculated by:

| (A.6) |

The calculation of the pressure amplitude due to shear mode conversion is analogous to the purely longitudinal case , and is given by:

| (A.7) |

where the propagation coefficients and due to shear mode conversion are given by:

| (A.8) |

and

| (A.9) |

Equation A.8 differs from equation A.4 through , the particle velocity transmission coefficient for the mode conversion of an incident longitudinal wave to a transmitted shear wave at the interface separating fluid and solid media. Similarly, equation A.9 differs from equation A.5 through the replacement of the longitudinal complex wavenumber by its shear counterpart ks2 = ω/cs2 − jαs2, substitution of ϕi1→i2 (the incident angle of a shear wave reaching the outer skull surface, represented in figure A1 by ϕi) for γi1→i2 (see figure A1), and finally through , the particle velocity transmission coefficient for the mode conversion of an incident shear wave to a transmitted longitudinal wave at the interface separating solid and fluid media.

The transmission of sound at an interface separating two media depends on the acoustical properties of the respective media. In our simulation volume the acoustical properties of medium 2 vary spatially, due to the heterogeneous distribution of density within the skull bone. Therefore, for each ray incident upon the inner and outer skull surfaces a local average of the skull’s acoustical parameters was calculated and used to compute the corresponding transmission coefficients. Similarly, the complex longitudinal and shear wavenumbers in the skull medium were calculated independently for each ray traversing the skull bone by spatially averaging the corresponding acoustical properties (speed of sound and attenuation coefficient) over the ray path (Pajek & Hynynen 2012). Details behind the calculation of the particle velocity transmission coefficients for fluidsolid and solid-fluid boundaries are not presented here, but can be found elsewhere in the literature (Brekhovskikh & Godin 1990).

The geometry of the skull bone required supplementary conditions to be met in order to ensure the correctness of the multi-layered propagation model. Due to the combination of the convex disposition of the skull with respect to the hemispherical array and the irregularity of the skull’s surfaces, not all inner skull surface elements will contribute to the particle velocity at a given outer skull surface element, as the path connecting the two elements may be blocked by a third element. A collision detection algorithm was implemented to determine which inner skull surface elements would contribute to a given outer skull surface element. Additionally, sound must arrive at each surface element with a valid angle of incidence. Rays whose incident angle at a given surface element exceeded the corresponding critical angle (either longitudinal or shear), as determined by Snell’s law, did not contribute to the particle velocity at that surface element. This is equivalent to neglecting the generation of evanescent waves along the corresponding boundary surface (Cobbold 2007).

References

- Alexandrov AV, Molina CA, Grotta JC, Garami Z, Ford S, Alvarez-Sabin J, Montaner J, Saqqur M, Demchuk AM, Moyé LA, Hill MD, Wojner AW. Ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;14(2):113–117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitis CD, Livingstone MS, Vykhodtseva N, McDannold N. Controlled ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier disruption using passive acoustic emissions monitoring. Public Library of Science ONE. 2012;7(9):e45783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry J-F, Tanter M, Gerber J, Thomas J-L, Fink M. Optimal focusing by spatio-temporal inverse filter. II. Experiments. Application to focusing through absorbing and reverberating media. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2001;110(1):48–58. doi: 10.1121/1.1377052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry J-F, Tanter M, Pernot M, Thomas J-L, Fink M. Experimental demonstration of noninvasive transskull adaptive focusing based on prior computed tomography scans. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2003;113(1):84–93. doi: 10.1121/1.1529663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron C, Aubry J-F, Tanter M, Meairs S, Fink M. Simulation of intracranial acoustic fields in clinical trials of sonothrombolysis. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2009;35(7):1148–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss CI. The calculation of the dosage-mortality curve. Annals of Applied Biology. 1935;22(1):134–167. [Google Scholar]

- Brekhovskikh LM, Godin OA. Plane-Wave Reflection from Boundaries of Solids. New York: Springer; 1990. Acoustics of layered media I: Plane and quasi-plane waves. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess A, Huang Y, Waspe AC, Ganguly M, Goertz DE, Hynynen K. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for dissolution of clots in a rabbit model of embolic stroke. Public Library of Science ONE. 2012;7(8):e42311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P-Y, Liu H-L, Hua M-Y, Yang H-W, Huang C-Y, Chu P-C, Lyu L-A, Tseng I-C, Feng L-Y, Tsai H-C, Chen S-M, Lu Y-J, Wang J-J, Yen T-C, Ma YH, Wu T, Chen J-P, Chuang J-I, Shin J-W, Hsueh C, Wei K-C. Novel magnetic/ultrasound focusing system enhances nanoparticle drug delivery for glioma treatment. Neuro-Oncology. 2010;12(10):1050–1060. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CCP, Yu ACH, Salimi N, Yiu BYS, Tsang IKH, Kerby B, Azar RZ, Dickie K. Multi-channel pre-beamformed data acquisition system for research on advanced ultrasound imaging methods. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 2012;59(2):243–253. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2012.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JJ, Coussios C-C. Spatiotemporal evolution of cavitation dynamics exhibited by flowing microbubbles during ultrasound exposure. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2012;132(5):3538–3549. doi: 10.1121/1.4756926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JJ, Pernot M, Small SA, Konofagou EE. Noninvasive, transcranial and localized opening of the blood-brain barrier using focused ultrasound in mice. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2007;33(1):95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement GT, Hynynen K. A non-invasive method for focusing ultrasound through the human skull. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2002a;47(8):1219–1236. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/8/301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement GT, Hynynen K. Correlation of ultrasound phase with physical skull properties. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2002b;28(5):617–624. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00503-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement GT, Sun J, Giesecke T, Hynynen K. A hemisphere array for non-invasive ultrasound brain therapy and surgery. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2000;45(12):3707–3719. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/12/314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement GT, Sun J, Hynynen K. The role of internal reflection in transskull phase distortion. Ultrasonics. 2001;39(2):109–113. doi: 10.1016/s0041-624x(00)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement GT, White J, Hynynen K. Investigation of a large-area phased array for focused ultrasound surgery through the skull. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2000;45(4):1071–1083. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/4/319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement GT, White PJ, Hynynen K. Enhanced ultrasound transmission through the human skull using shear mode conversion. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2004;115(3):1356–1364. doi: 10.1121/1.1645610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbold R. Foundations of Biomedical Ultrasound. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Connor CW, Clement GT, Hynynen K. A unified model for the speed of sound in cranial bone based on genetic algorithm optimization. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2002;47(22):3925–3944. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/22/302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coviello CM, Kozick RJ, Hurrell A, Smith PP, Coussios C-C. Thin-film sparse boundary array design for passive acoustic mapping during ultrasound therapy. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 2012;59(10):2322–2330. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2012.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culp WC, Flores R, Brown AT, Lowery JD, Roberson PK, Hennings LJ, Woods SD, Hatton JH, Culp BC, Skinner RD, Borrelli MJ. Successful microbubble sonothrombolysis without tissue-type plasminogen activator in a rabbit model of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(8):2280–2285. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.607150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Coussios C-C, Ammi AY, Mast TD, de Courten-Myers GM, Holland CK. Ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis using Definity as a cavitation nucleation agent. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2008;34(9):1421–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Coussios C-C, McAdory LE, Tan J, Porter T, de Courten-Myers G, Holland CK. Correlation of cavitation with ultrasound enhancement of thrombolysis. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2006;32(8):1257–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daum DR, Buchanan MT, Fjield T, Hynynen K. Design and evaluation of a feedback based phased array system for ultrasound surgery. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 1998;45(2):431–438. doi: 10.1109/58.660153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De M, Basuray A. Two-point resolution in partially coherent light I. Ordinary microscopy, disc source. Optica Acta: International Journal of Optics. 1972;19(4):307–318. [Google Scholar]

- Duck FA. Physical properties of tissue: A comprehensive reference book, a comprehensive reference book. London: Academic Press Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Elias J, Huss D, Mohamad K, Monteith S, Frysinger R, Loomba J, Druzgal J, Wylie S, Voss T, Harrison M, Wooten F, Wintermark M. MR guided focused ultrasound lesioning for the treatment of essential tremor. A new paradigm for noninvasive lesioning and neuromodulation; Congress of Neurological Surgeons 2011 Annual Meeting; Washington, DC. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Hynynen K. The effects of curved tissue layers on the power deposition patterns of therapeutic ultrasound beams. Medical physics. 1994;21(1):25–34. doi: 10.1118/1.597250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farny CH, Holt RG, Roy RA. Temporal and spatial detection of HIFU-induced inertial and hot-vapor cavitation with a diagnostic ultrasound system. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2009;35(4):603–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, Montaldo G, Tanter M. Time-reversal acoustics in biomedical engineering. Annual Reviews of Biomedical Engineering. 2003;5:465–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.5.040202.121630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry FJ, Barger JE. Acoustical properties of the human skull. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1978;63(5):1576–1590. doi: 10.1121/1.381852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gateau J, Aubry J-F, Pernot M, Fink M, Tanter M. Combined passive detection and ultrafast active imaging of cavitation events induced by short pulses of high-intensity ultrasound. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 2011;58(3):517–532. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2011.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilov LR, Hand JW. A theoretical assessment of the relative performance of spherical phased arrays for ultrasound surgery. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 2000;47(1):125–139. doi: 10.1109/58.818755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss SA, Frizzell LA, Kouzmanoff JT, Barich JM, Yang JM. Sparse random ultrasound phased array for focal surgery. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 1996;43(6):1111–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Gyöngy M. PhD thesis. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford; 2010. Passive cavitation mapping for monitoring ultrasound therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Gyöngy M, Coussios C-C. Passive cavitation mapping for localization and tracking of bubble dynamics. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2010a;128(4):EL175–EL180. doi: 10.1121/1.3467491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyöngy M, Coussios C-C. Passive spatial mapping of inertial cavitation during HIFU exposure. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2010b;57(1):48–56. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2026907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyöngy M, Coviello CM. Passive cavitation mapping with temporal sparsity constraint. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2011;130(5):3489–3497. doi: 10.1121/1.3626138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn WR. Optimum signal processing for passive sonar range and bearing estimation. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1975;58(1):201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Harris G. Review of transient field theory for a baffled planar piston. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1981;70(1):10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Haworth KJ, Mast TD, Radhakrishnan K, Burgess MT, Kopechek JA, Huang S-L, McPherson DD, Holland CK. Passive imaging with pulsed ultrasound insonations. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2012;132(1):544–553. doi: 10.1121/1.4728230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Deng J, Xie Z, Wang F, Chen S, Lei B, Liao P, Huang N, Wang Z, Wang Z, Cheng Y. Effective gene transfer into central nervous system following ultrasound-microbubbles-induced opening of the blood-brain barrier. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2012;38(7):1234–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K. The threshold for thermally significant cavitation in dog’s thigh muscle in vivo. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1991;17(2):157–169. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(91)90123-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K, Clement G. Clinical applications of focused ultrasound-The brain. International Journal of Hyperthermia. 2007;23(2):193–202. doi: 10.1080/02656730701200094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K, Jolesz FA. Demonstration of potential noninvasive ultrasound brain therapy through an intact skull. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1998;24(2):275–283. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(97)00269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz FA. Noninvasive MR imaging–guided focal opening of the blood-brain barrier in rabbits. Radiology. 2001;220(3):640–646. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2202001804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K, Sun J. Trans-skull ultrasound therapy: the feasibility of using image-derived skull thickness information to correct the phase distortion. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 1999;46(3):752–755. doi: 10.1109/58.764862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DR, Dowling DR. Phase conjugation in underwater acoustics. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1991;89(1):171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Jeanmonod D, Werner B, Morel A, Michels L, Zadicario E, Schiff G, Martin E. Transcranial magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound: noninvasive central lateral thalamotomy for chronic neuropathic pain. Neurosurgical Focus. 2012;32(1):E1, 1–11. doi: 10.3171/2011.10.FOCUS11248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen CR, Ritchie RW, Gyöngy M, Collin JRT, Leslie T, Coussios C-C. Spatiotemporal monitoring of high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy with passive acoustic mapping. Radiology. 2012;262(1):252–261. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsman N, Shwartz ML, Huang Y, Lee L, Sankar T, Chapman M, Hynynen K, Lozano AM. MR-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor: a proof-of-concept study. The Lancet Neurology. 2013;12(5):462–468. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood GR, Foster FS. Optimizing the radiation pattern of sparse periodic two-dimensional arrays. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 1996;43(1):15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Martin E, Jeanmonod D, Morel A, Zadicario E, Werner B. High-intensity focused ultrasound for noninvasive functional neurosurgery. Annals of Neurology. 2009;66(6):858–861. doi: 10.1002/ana.21801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Arvanitis CD, Vykhodtseva N, Livingstone MS. Temporary disruption of the blood-brain barrier by use of ultrasound and microbubbles: safety and efficacy evaluation in rhesus macaques. Cancer Research. 2012;72(14):3652–3663. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Clement GT, Black P, Jolesz F, Hynynen K. Transcranial magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound surgery of brain tumors: initial findings in 3 patients. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(2):323–332. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000360379.95800.2F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold NJ, Vykhodtseva NI, Hynynen K. Microbubble contrast agent with focused ultrasound to create brain lesions at low power levels: MR imaging and histologic study in rabbits. Radiology. 2006a;241(1):95–106. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2411051170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Hynynen K. Targeted disruption of the blood-brain barrier with focused ultrasound: association with cavitation activity. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2006b;51(4):793–807. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/4/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medel R, Crowley RW, McKisic MS, Dumont AS, Kassell NF. Sonothrombolysis: an emerging modality for the management of stroke. Neurosurgery. 2009;65(5):979–993. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000350226.30382.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton SJ, Carr BJ, Witten AJ. Passive imaging of underground acoustic sources. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2006;119(5):2840–2847. [Google Scholar]

- Norton SJ, Won IJ. Time exposure acoustics. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing. 2000;38(3):1337–1343. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil HT. Theory of focusing radiators. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1949;21(5):516–526. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly MA, Hynynen K. A PVDF receiver for ultrasound monitoring of transcranial focused ultrasound therapy. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2010;57(9):2286–2294. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2010.2050483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly MA, Hynynen K. Blood-brain barrier: real-time feedback-controlled focused ultrasound disruption by using an acoustic emissions-based controller. Radiology. 2012;263(1):96–106. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11111417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajek D, Hynynen K. The design of a focused ultrasound transducer array for the treatment of stroke: a simulation study. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2012;57(15):4951–4968. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/15/4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernot M, Aubry J-F, Tanter M, Thomas J-L, Fink M. High power transcranial beam steering for ultrasonic brain therapy. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2003;48(16):2577–2589. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2076829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo S, Hynynen K. Treatment of near-skull brain tissue with a focused device using shear-mode conversion: a numerical study. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2007;52(24):7313–7332. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/24/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo S, Sin VW, Hynynen K. Multi-frequency characterization of the speed of sound and attenuation coefficient for longitudinal transmission of freshly excised human skulls. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2011;56(1):219–250. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/1/014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen A, Huang Y, Song J, Hynynen K. Simulations and measurements of transcranial low-frequency ultrasound therapy: skull-base heating and effective area of treatment. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2011;56(15):4661–4683. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/15/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgaonkar V, Datta S, Holland CK, Mast TD. Passive cavitation imaging with ultrasound arrays. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2009;126(6):3071–3083. doi: 10.1121/1.3238260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Sasaki K. Bispectral holography. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1977;62(2):404–408. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SW, Trahey GE, von Ramm OT. Phased array ultrasound imaging through planar tissue layers. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1986;12(3):229–243. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(86)90314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokka SD, King R, Hynynen K. MRI-guided gas bubble enhanced ultrasound heating in in vivo rabbit thigh. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2003;48(2):223–241. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/2/306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Hynynen K. Feasibility of using lateral mode coupling method for a large scale ultrasound phased array for noninvasive transcranial therapy. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2010;57(1):124–133. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2028739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Pulkkinen A, Huang Y, Hynynen K. Investigation of standing-wave formation in a human skull for a clinical prototype of a large-aperture, transcranial MR-guided focused (MRgFUS) phased array: an experimental and simulation study. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2012;59(2):435–444. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2174057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg BD. Principles of Aperture and Array System Design: Including Random and Adaptive Arrays. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Hynynen K. Focusing of therapeutic ultrasound through a human skull: a numerical study. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1998;104(3):1705–1715. doi: 10.1121/1.424383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Hynynen K. The potential of transskull ultrasound therapy and surgery using the maximum available skull surface area. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1999;105(4):2519–2527. doi: 10.1121/1.426863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanter M, Aubry J-F, Gerber J, Thomas J-L, Fink M. Optimal focusing by spatio-temporal inverse filterIBasic principles. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2001;110(1):37–47. doi: 10.1121/1.1377051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanter M, Thomas J-L, Fink M. Time reversal and the inverse filter. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2000;108(1):223–234. doi: 10.1121/1.429459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J-L, Fink MA. Ultrasonic beam focusing through tissue inhomogeneities with a time reversal mirror: application to transskull therapy. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 1996;43:1122–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Treece M, Prager RW, Gee AH, Berman L. Surface interpolation from sparse cross sections using region correspondence. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2000;19(11):1106–1114. doi: 10.1109/42.896787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung Y-S, Vlachos F, Choi JJ, Deffieux T, Selert K, Konofagou EE. In vivo transcranial cavitation threshold detection during ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening in mice. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2010;55(20):6141–6155. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/20/007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull DH, Foster FS. Beam steering with pulsed two-dimensional transducer arrays. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 1991;38(4):320–333. doi: 10.1109/58.84270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J, Clement GT, Hynynen K. Transcranial ultrasound focus reconstruction with phase and amplitude correction. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 2005;52(9):1518–1522. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1516024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PJ, Clement GT, Hynynen K. Longitudinal and shear mode ultrasound propagation in human skull bone. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2006;32(7):1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright C, Hynynen K, Goertz DE. In vitro and in vivo high-intensity focused ultrasound thrombolysis. Investigative Radiology. 2012;47(4):217–225. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31823cc75c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen JT, Steinberg JP, Smith SW. Sparse 2-D array design for real time rectilinear volumetric imaging. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 2000;47(1):93–110. doi: 10.1109/58.818752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Hynynen K. A numerical study of transcranial focused ultrasound beam propagation at low frequency. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2005;50(8):1821–1836. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/8/013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]