Abstract

Background

Drug companies maintain close contact with physicians. We studied the extent to which medical students are already in contact with drug companies, and their attitudes toward them.

Methods

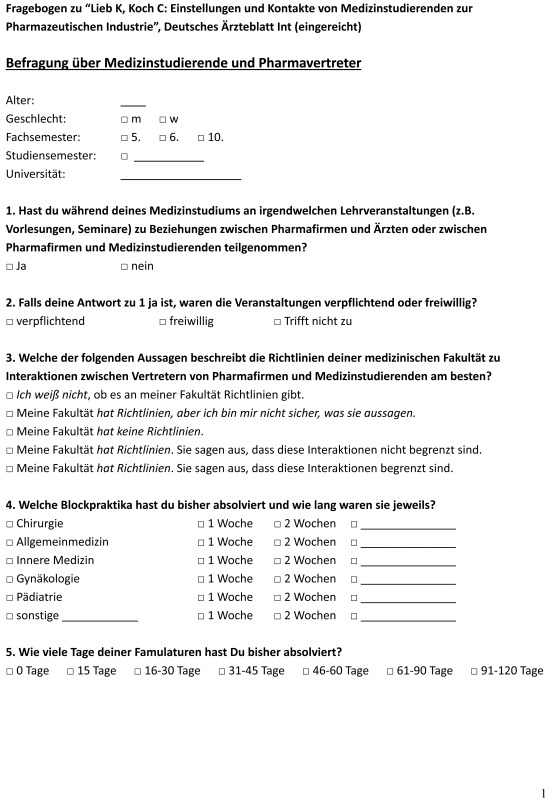

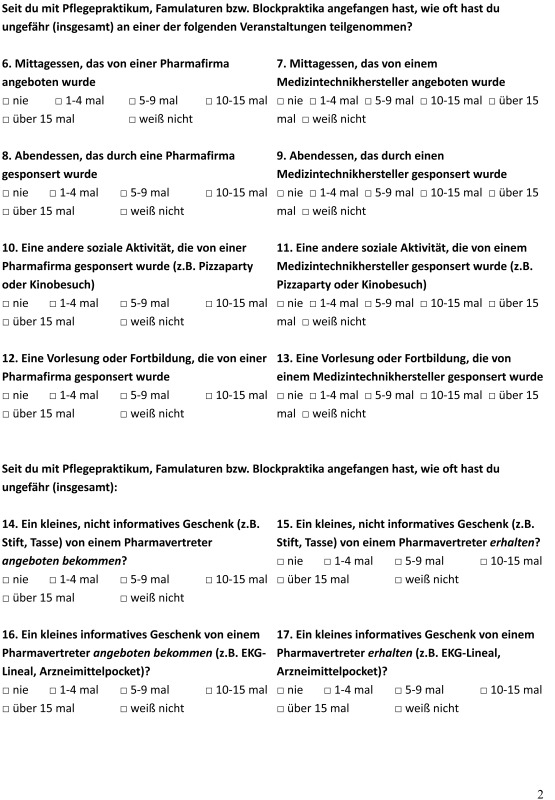

An anonymous questionnaire containing 74 questions was distributed to 1151 medical students at eight German universities. 1038 (90.3%) of the questionnaires were filled out, returned, and evaluated.

Results

12.1% of the students had never received any kind of gift from a drug company or participated in any drug company–sponsored event. 13.0% had received at least one sponsored lunch, and 24.6% had attended at least one sponsored lecture or CME event. 65.6% had received at least one non-informational gift, 50.8% an informational gift, 39.3% a reprint, and 8.6% a drug sample. 39.8% considered sponsored lectures informative and helpful, but simultaneously judged the presentation of content as biased. 45.6% and 49.7% of students, respectively, considered it all right to accept gifts because their influence was minimal in any case or because they considered themselves in a bad financial situation. 24.6% of the students thought gifts would influence their future prescribing behavior, while 45.1% thought gifts would influence their classmates’ future prescribing behavior (p<0.001 for this difference).

Conclusion

Medical students have extensive contact with the pharmaceutical industry even before they are out of medical school. Therefore, the medical school curriculum should include information about the strategies drug companies use to influence physicians’ prescribing behavior, so that medical students can develop an appropriately critical attitude.

There is a great deal of contact between doctors and pharmaceutical companies in Germany (1– 3). In an earlier paper (3) we showed that 77% of physicians in private practice were visited by a pharmaceutical sales representative (PSR) at least once a week, and 19% were visited every day.

Although approximately half of physicians take a critical attitude towards the information provided, only 6% consider themselves often or always prone to influence by PSRs (3). This reveals a blind spot in physicians’ attitudes towards their own susceptibility to influence, as does the fact that physicians consider their colleagues more easily influenced than themselves (3). Close contact between physicians and PSRs does in fact lead to changes in prescribing behavior. This has been suggested in studies by the fact that contact with PSRs is associated with more frequent prescriptions, higher prescription costs, and lower prescription quality (4).

In Germany, research has not yet investigated whether or how medical students come into contact with pharmaceutical companies, or their attitudes towards interaction between pharmaceutical companies and medical students. International studies show that 74% to 100% of medical students have already come into contact with pharmaceutical companies during their clinical studies (5, 6). The variety of types of contact is similar to that of the contact between pharmaceutical companies and physicians (5– 14).

However, due to differences in the structure of medical training, the involvement of medical students in clinical work and the strategies of PSRs, these findings from foreign countries can not be extrapolated to Germany. We therefore investigated German medical students’ attitudes to and contact with pharmaceutical companies.

Methods

Of the 36 German medical faculties contacted, 26 gave their basic consent to a survey among their medical students on contact with pharmaceutical companies. A stratified sample of eight of these 26 universities was established on the basis of the following factors:

Existence of a guideline on contact with PSRs

Type of program (conventional or Modellstudiengang, a newer type of program in which theory and practice are combined from an early stage)

Geographical location: east or west Germany.

A total of 1151 medical students in the fifth to tenth semester of their studies from these eight universities were surveyed between May 10, 2012 and July 12, 2012, using a questionnaire.

All 1151 students were given a questionnaire containing 74 questions (eQuestionnaire [in German]) at the beginning of a lecture (by C. Koch). They filled out the questionnaire immediately and submitted it anonymously. The questionnaire consisted of a German translation of the questionnaire by Sierles et al. (12), with the addition of questions 4, 5, 7, 9–11, 13, 14, 16, 18–20, 22, 30, 31, 61–63, 73, and 74. This allowed for direct comparison with the USA on the one hand while focusing additional attention on the situation in Germany on the other.

Most of the results are shown as both percentages of answers and absolute figures. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0. McNemar’s test was used to verify whether more students would describe themselves than their peers as susceptible to influence.

To make it easier to compare students’ exposure to pharmaceutical companies, an exposure index was calculated in a similar way to the procedure used by Sierles et al. (12). This took length of study into account, to minimize the influence of the duration of study on the amount of exposure. The exposure index was calculated by adding together the answers to the question on how often students had certain types of contact with pharmaceutical companies and dividing the result by the number of semesters since the beginning of the clinical part of the program.

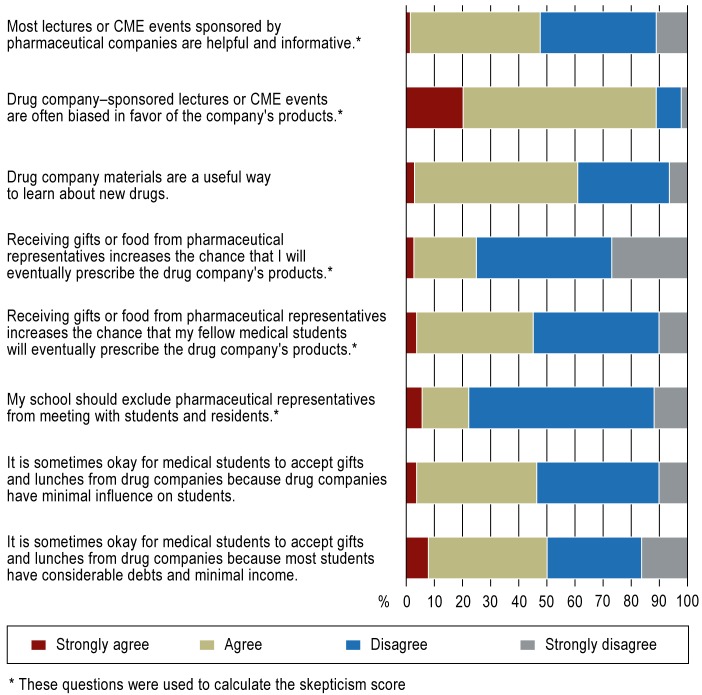

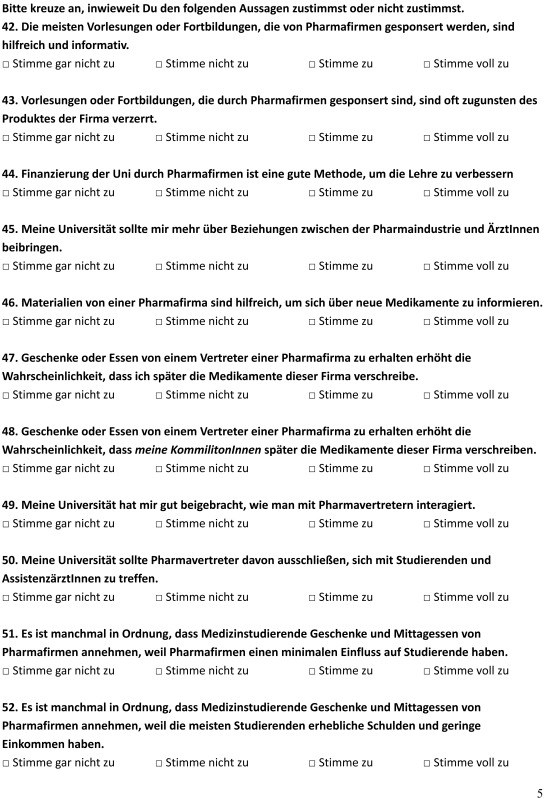

A skepticism score was calculated to assess students’ skepticism (12). Students answered six questions on their attitudes to pharmaceutical companies’ marketing (Figure 1). Answers took the form of a four point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly agree” (1) to “Strongly disagree” (4). The answers were used to calculate a score according to the formula ([(5-F42) + (5-F44) + F43 + F47 + F48 + F50] / 24) × (4/3) - (1/3), where FX is the answer to question X in the questionnaire. The possible range of scores was from 0 (not skeptical) to 1 (very skeptical). Scores were calculated only for students who had answered all six questions.

Figure 1.

Students’ attitudes

to interaction with pharmaceutical companies

An appropriateness score was calculated to assess students’ feelings on the appropriateness of gifts/events provided by pharmaceutical companies (12). The students rated the appropriateness of eight different gifts using a scale from 1 (very appropriate) to 5 (very inappropriate). The answers were used to calculate a score according to the formula ([F53 + F54 + F55 + F56 + F57 + F58 + F59 + F60] / 40) × 1.25 - 0.25. The possible range of scores was from 0 (very little feeling of inappropriateness) to 1 (very strong feeling of inappropriateness) and was calculated only for students who had rated all eight gifts.

Results

Sample

Of the 1151 medical students given the questionnaire, 90.3% (n = 1039) completed it and returned it anonymously. One questionnaire completed by a foreign Erasmus student was excluded; 1038 questionnaires were therefore evaluated. The demographic data for the sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic data of sample.

| Age (years) | Total answers | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Standard deviation | ||

| 1024 | 24.33 | 20 | 51 | 3.23 | |||

| Sex | Total answers | Male | Female | ||||

| 1032 | 324 (31.4%) | 708 (68.6%) | |||||

| Semester in which most courses are taken | Total answers | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1037 | 24 (2.3%) | 529 (51.0%) | 5 (0.5%) | 40 (3.9%) | 1 (0.1%) | 438 (42.2%) | |

| Total semesters of study | Total answers | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1035 | 12 (1.2%) | 476 (46.0%) | 22 (2.1%) | 66 (6.4%) | 10 (1.0%) | 352 (34.0%) | |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||

| 38 (3.7%) | 39 (3.8%) | 4 (0.4%) | 7 (0.7%) | 3 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1%) | ||

| 17 | 18 | 20 | 31 | ||||

| 2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | ||||

| University | RWTH Aachen | TU Dresden | ALU Freiburg | JLU Giessen | GAU Göttingen | FSU Jena | |

| Clinical subject in 6th semester | Pharmacology*1 | Radiology | Pharmacology | Pharmacology | Pharmacology | Biometrics | |

| Questionnaires/ attendees (%)*2 | 35/35 (100) | 80/96 (83) | 148/200 (74.0) | 59/59 (100) | 39/39 (100) | 99/100 (99) | |

| Clinical subject in 10th semester | Clinical pharmacology | Epidemiology | Forensic medicine | Clinical pharmacology | ENT | ||

| Questionnaires/ attendees (%)*2 | 69/69 (100) | 105/105 (100) | 57/60 (95.0) | 50/53 (94) | 43/67 (64) | ||

| University of Cologne | University of Münster | Total | |||||

| Clinical subject in 6th semester | Pharmacology | Cardiology | |||||

| Questionnaires/ attendees (%)*2 | 76/76 (100) | 59/59 (100) | 1039/1151 (90.3) | ||||

| Clinical subject in 10th semester | Forensic medicine | Pediatrics | |||||

| Questionnaires/ attendees (%)*2 | 48/53 (91) | 72/80 (90) |

*1Seminar in 8th semester; *2Number receiving questionnaires/total number of lecture attendees (percentage)

Experience with gifts and sponsorship by pharmaceutical companies

Table 2 provides an overview of the medical students’ experiences with gifts and sponsorship by pharmaceutical companies. The results shown can be summarized as follows:

Table 2. Frequency with which students have received certain gifts or attended certain events sponsored by pharmaceutical companies.

| Sponsored gift / event | Total answers | Don’t know | Never | 1 to 4 times | 5 to 9 times | 10 to 14 times | 15 times or more |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lunch* | 1033 | 13 (1.3%) | 886 (85.8%) | 98 (9.5%) | 19 (1.8%) | 14 (1.4%) | 3 (0.3%) |

| Dinner* | 1032 | 12 (1.2%) | 947 (91.8%) | 67 (6.5%) | 4 (0.4%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Social activity* | 1033 | 14 (1.4%) | 967 (93.6%) | 47 (4.5%) | 3 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Lecture* | 1032 | 56 (5.4%) | 722 (70.0%) | 216 (20.9%) | 27 (2.6%) | 9 (0.9%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| Noneducational gift* | 1030 | 12 (1.2%) | 342 (33.2%) | 478 (46.4%) | 105 (10.2%) | 43 (4.2%) | 50 (4.9%) |

| Educational gift* | 1033 | 11 (1.1%) | 497 (48.1%) | 448 (43.4%) | 57 (5.5%) | 10 (1.0%) | 10 (1.0%) |

| Snack* | 1032 | 25 (2.4%) | 573 (55.5%) | 314 (30.4%) | 77 (7.5%) | 27 (2.6%) | 16 (1.6%) |

| Reprint* | 1031 | 21 (2.0%) | 605 (58.7%) | 334 (32.4%) | 48 (4.7%) | 14 (1.4%) | 9 (0.9%) |

| Gift passed on by a doctor | 1027 | 14 (1.4%) | 401 (39.0%) | 461 (44.9%) | 77 (7.5%) | 33 (3.2%) | 41 (4.0%) |

*These gifts/events were used to calculate the exposure index

12.1% (126/1038) of the students had never yet accepted a gift from a pharmaceutical company or attended a sponsored event.

13.0% (134/1033) of the students had attended at least one sponsored lunch, 5.0% (52/1033) a sponsored social activity, and 24.6% (254/1032) a sponsored lecture/CME event.

65.6% (676/1030) had received at least one noneducational gift (9.0% [93] had received at least 10).

50.8% (525/1033) had received at least one educational gift (1.9% [20] had received at least 10).

42.0% (434/1032) had had at least one snack (4.2% [43] had had at least 10).

39.3% (405/1031) had received at least one reprint (2.2% [23] had received at least 10).

8.6% (89/1030) had received at least one drug sample from a PSR (0.3% [3] had received at least 10).

19.5% (192/987) had received at least one book from a pharmaceutical company.

3.6% of the students (36/987) had traveled to at least one conference at the expense of a pharmaceutical company.

4.0% (39/987) had received reimbursement of conference registration fees from a pharmaceutical company.

10.4% (103/987) of the students had taken part in a sponsored workshop.

The mean exposure index was 3.80 (95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 1.33 to 14.50; standard deviation [SD]: 2.09). This means that students had had an average of approximately nine contacts with the industry per semester of the clinical part of their studies.

Attitudes to contact with pharmaceutical companies

47.1% (366/777) of the students thought that sponsored lectures were helpful and informative, and 60.4% (590/977) found pharmaceutical companies’ materials such as drug pocket guides, reprints of publications, or glossy brochures helpful for their studies (figure 1). At the same time, 88.4% (752/851) considered the information provided in sponsored lectures to be biased. 39.8% (307/772) considered sponsored lectures helpful and informative, and at the same time biased. 45.6% (451/988) of the students believed that accepting gifts was sometimes acceptable because these had only a minimal influence on them, and 49.7% (492/990) believed it was acceptable because of their financial worries. Fewer students thought that gifts were likely to affect their own prescribing behavior (24.6%; 246/998) than that of their peers (45.1%; 444/985; p<0.001). 21.9% (216/989) thought PSRs should be prohibited from meeting with students. 7.6% (78/1026) of the students had already heard of the international organization No Free Lunch, and 6.3% (64/1018) were aware of its German branch, MEZIS (this stands for “Mein Essen zahl’ ich selbst,” or “I pay for my own meals”). 60.2% (622/1034) of the students had already discussed the pros and cons of gifts given to physicians by pharmaceutical companies with a friend or peer.

The skepticism score (12) was successfully calculated for 750 students. The mean score was 0.51 (95% CI: 0.11 to 1.0; SD: 0.13), a neutral result.

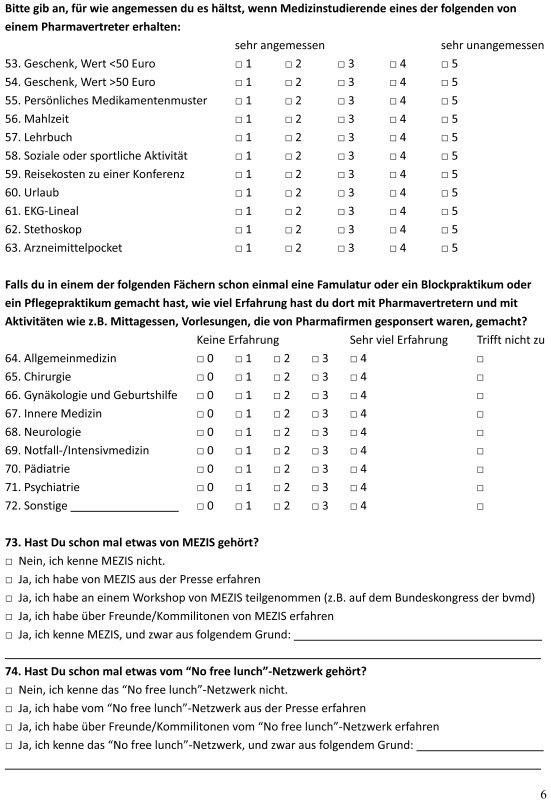

Assessing the appropriateness of gifts

The results of the students’ assessment of the appropriateness of specific gifts are shown in Table 3. 9.2% of the students (93/1008) thought that gifts worth more than €50 were very appropriate. A gift of an ECG ruler or a drug pocket guide was even seen as a very appropriate gift by more than 45.0% (467/1013) and 40.9% (415/1015) respectively. 30.0% (305/1015) of the students considered a textbook very appropriate, and 24.8% (250/1009) considered travel to attend a conference very appropriate.

Table 3. Students’ assessment of the appropriateness of gifts.

| Type of gift | Total answers | Very appropriate | 2 | 3 | 4 | Very inappropriate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | |||||

| Gift worth less than €50*1 | 1005 | 128 (12.7%) | 223 (22.2%) | 262 (26.1%) | 170 (16.9%) | 222 (22.1%) |

| Gift worth more than €50*1 | 1008 | 93 (9.2%) | 60 (6.0%) | 104 (10.3%) | 218 (21.6%) | 533 (52.9%) |

| Drug sample*1 | 1002 | 129 (12.9%) | 205 (20.5%) | 213 (21.3%) | 165 (16.5%) | 290 (28.9%) |

| Meal*1 | 1009 | 185 (18.3%) | 284 (28.1%) | 262 (26.0%) | 139 (13.8%) | 139 (13.8%) |

| Textbook*1 | 1015 | 305 (30.0%) | 347 (34.2%) | 188 (18.5%) | 88 (8.7%) | 87 (8.6%) |

| Social or sporting activity*1 | 1003 | 152 (15.2%) | 220 (21.9%) | 245 (24.4%) | 182 (18.1%) | 204 (20.3%) |

| Travel to conference*1 | 1009 | 250 (24.8%) | 276 (27.4%) | 190 (18.8%) | 134 (13.3%) | 159 (15.8%) |

| Vacation*1 | 1008 | 82 (8.1%) | 36 (3.6%) | 73 (7.2%) | 168 (16.7%) | 649 (64.4%) |

| ECG ruler | 1013 | 467 (45.0%) | 336 (33.2%) | 126 (12.4%) | 31 (3.1%) | 53 (5.2%) |

| Stethoscope | 1013 | 286 (28.2%) | 287 (28.3%) | 210 (20.7%) | 119 (11.7%) | 111 (11.0%) |

| Drug pocket guide*2 | 1015 | 415 (40.9%) | 334 (32.9%) | 149 (14.7%) | 51 (5.0%) | 66 (6.5%) |

*1These answers were used to calculate the appropriateness score.

*2A book small enough to fit into the pocket of a white coat, containing information on drugs. Likert scale from 1 to 5 (“Very appropriate” to “Very inappropriate”)

12.8% (21/164) of the students who thought it very inappropriate to accept a textbook had already received one. 7.6% (21/278) of the students who rated a sponsored meal as inappropriate had already attended a sponsored lunch.

Because answers were missing for some individual variables, the appropriateness score (12) could be calculated for 971 students. The mean was 0.55 (95% CI: 0.0 to 1.0; SD: 0.25). This showed a feeling of inappropriateness that was somewhat stronger than neutral.

The role of practicing physicians as intermediaries

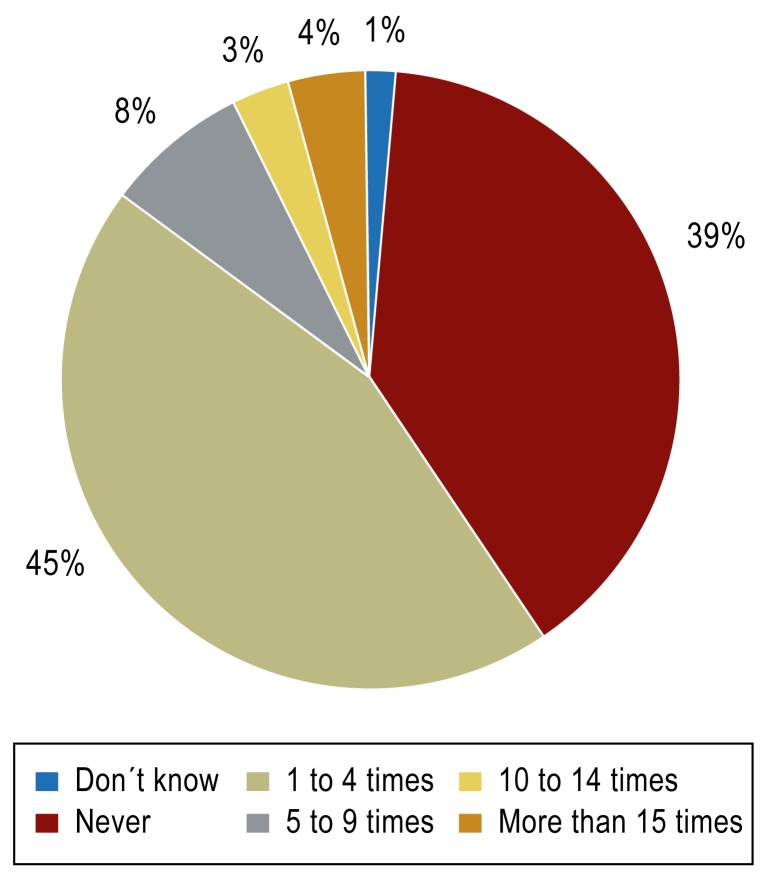

42.0% (434/1033) of the students had already discussed the pros and cons of gifts to physicians from pharmaceutical companies with a doctor at least once, and 10.6% (109/1031) had talked about sponsorship of events. 2.7% (28/1033) of the students had been asked to attend a sponsored dinner by a physician at least once. Of these, seven students had been asked to attend such dinners more than five times. 59.6% (612/1027) of the students had had at least one gift passed on to them by a physician (Figure 2). The most common gifts were as follows:

Figure 2.

Frequency with which students have received gifts passed on to them from physicians

Pens (53.5%, 541/1030)

ECG rulers (30.3%, 312/1030)

Tourniquets (19.4%, 201/1030)

Pocket lights (15.9%, 164/1030)

Drug pocket guides (15.1%, 156/1030)

Reprints (14.9%, 153/1030).

Mugs (9.8%, 101/1030), drug samples (8.7%, 90/1030), textbooks (8.5%, 88/1030), and stethoscopes (3.1%, 32/1030) were also given to students.

Discussion

In Germany as in other countries, medical students come into frequent contact with pharmaceutical companies. Thus only 12% of students had never yet accepted a gift from a pharmaceutical company or attended a sponsored event, while approximately 65% had received a small gift such as a pen or mug from a PSR. Approximately a quarter of the students had already attended a sponsored event. These data are essentially in line with those of international studies (5–7, 12). In the USA, however, contact rates were as high as 100% in one study (6), and the percentage of students who had accepted gifts was 95% in another (12). This may be because in the USA medical students receive clinical training in hospitals even earlier and more frequently.

Concerning the students’ attitudes, it was found that German students were not very skeptical and had only a slightly higher sense for the inappropriateness of gifts. They were fundamentally somewhat more skeptical than US students (12), but this skepticism did not always lead to corresponding behavior: In Germany, too, students who rated particular gifts as inappropriate had accepted them or attended sponsored events. 7.6% (21/278) of the students who considered sponsored lunches inappropriate had attended one (versus 12.0% of students overall). A textbook had been accepted by 12.8% (21/164) of the students who considered it inappropriate to accept a textbook (versus 19.8% overall). This may be because approximately half of the students considered it acceptable to take gifts because they believed gifts had only a minimal influence on them, or that the difficult financial situation of most students justified such behavior. These results are in line with experimental findings obtained for physicians, as physicians are also more inclined to approve of accepting gifts if they are first reminded of the hardships of student life (15). In summary, these findings can be interpreted as showing that students often express skepticism towards pharmaceutical companies’ attempts to influence them when asked. However, when such offers are made they accept pharmaceutical companies’ gifts because they believe that pharmaceutical companies’ influence is small or that they are entitled to accept gifts because of their financial situation.

The blind spot concerning their own susceptibility to influence, which was found in studies among physicians (3, 16, 17), was also found in students. Thus only 24.6% of questionnaire respondents reported that they believed that accepting gifts influenced their later prescribing behavior, whereas 45.1% believed that it affected that of their peers. Fewer students in Germany than in the USA considered themselves to be influenced, while they considered their peers to be influenced more frequently (12).

These results also suggest that physicians play a major role in both establishing contact and passing on attitudes to pharmaceutical companies. For example, approximately 60% of the students reported that they had already received at least one gift that had been passed on to them by a physician. In addition, 42% of the students had already discussed the pros and cons of gifts with a doctor, and the students’ attitudes mostly matched those of physicians (3, 18). It can therefore be assumed that students learn from the examples set by physicians and that students adopt physicians’ contact with and attitudes to pharmaceutical companies during their studies (19).

These results highlight the importance of making students aware of the potential influence of drug marketing at an early stage in their studies (20). As established at the Charité hospital in Berlin, for example, in a required elective subject (21), and implemented at the Universities of Mainz and Ulm in lectures, the potential effects of close contact with the industry should be discussed on the one hand, and on the other, alternative ways to behave must be demonstrated and rehearsed. This would enable students themselves to develop a critical attitude towards pharmaceutical companies. Similarly, doctors who work in medical education should also receive training. Courses of this kind should subsequently be evaluated to ensure they are effective.

Another possibility would be to create guidelines for universities on students’ contact with pharmaceutical companies. Although a new study has shown no clear correlation between students’ attitudes and the quality of university guidelines (14), another study of students did find evidence that even small gifts can lead to a positive attitude towards the product being advertised (8). In addition, a current study has shown that when teaching staff disclose conflicts of interest to students this stimulates a critical attitude towards pharmaceutical companies (22). Critical skills might also be further developed by providing knowledge of the industry’s influence on the conduct and publication of drug trials (23, 24).

In this study we have attempted to survey a sample of students that was as representative as possible, by creating a stratified sample of universities. However, students were not selected at random to be surveyed; instead, the questionnaires were distributed at lectures. There may therefore be some selection bias, for example because particularly critical students attended lectures. We strove to guarantee a feeling of anonymity by distributing questionnaires at well-attended lectures, in order to prevent students from giving answers that were socially desirable. However, the students filled out the questionnaires immediately, some of them sitting closely together.Thus a social desirability bias cannot be ruled out entirely, as complete anonymity was not guaranteed.

Key Messages.

Almost 90% of medical students in Germany have accepted a gift from a pharmaceutical company or attended a sponsored event at least once.

The most frequently accepted items are noneducational and educational gifts, snacks, reprints, and sponsored teaching events.

Medical students display a blind spot regarding their own susceptibility to influence. They consider their peers to be susceptible approximately twice as often as themselves.

Almost 50% of students believe that taking gifts is acceptable because of financial concerns or because it has only minimal influence on them.

Compulsory courses on this subject should be introduced in order to encourage a critical attitude in students; they should be subsequently evaluated to determine whether they are in fact effective.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Devitt, M.A.

The authors would like to thank Dr. R. Sierles for permission to use his questionnaire (12), and the offices of deans of student affairs and the students who participated for their support and collaboration.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Both authors are members of MEZIS e.V. Prof. Lieb is also head of the Conflicts of Interest Working Group of the Drug Commission of the German Medical Association (AkdÄ, Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft).

References

- 1.Merten M, Rabbata S. Selbsthilfe und Pharmaindustrie: Nicht mit und nicht ohne einander. Dtsch Arztebl. 2007;104(46):A3157–A-3162. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiesner A, Lieb K. Interessenkonflikte durch Arzt-Industrie-Kontakte in Praxis und Klinik und Vorschläge zu deren Reduzierung. In: Lieb K, Klemperer D, Ludwig WD, editors. Interessenkonflikte in der Medizin. Hintergründe und Lösungsmöglichkeiten. Heidelberg: Springer; 2011. pp. 162–173. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieb K, Brandtönies S. A survey of german physicians in private practice about contacts with pharmaceutical sales representatives. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(22):392–398. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spurling GK, Mansfield PR, Montgomery BD, et al. Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians’ prescribing: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lea D, Spigset O, Slørdal L. Norwegian medical students’ attitudes towards the pharmaceutical industry. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:727–733. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0805-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkes MS, Hoffman JR. An innovative approach to educating medical students about pharmaceutical promotion. Acad Med. 2001;76:1271–1277. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200112000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Austad KE, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. Medical students’ exposure to and attitudes about the pharmaceutical industry: a systematic review. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grande D, Frosch DL, Perkins AW, Kahn BE. Effect of exposure to small pharmaceutical promotional items on treatment preferences. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169 doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyman PL, Hochman ME, Shaw JG, Steinman MA. Attitudes of preclinical and clinical medical students toward interactions with the pharmaceutical industry. Acad Med. 2007;82:94–99. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000249907.88740.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monaghan MS, Galt KA, Turner PD, et al. Student understanding of the relationship between the health professions and the pharmaceutical industry. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15:14–20. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1501_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandberg WS, Carlos R, Sandberg EH, Roizen MF. The effect of educational gifts from pharmaceutical firms on medical students’ recall of company names or products. Acad Med. 1997;72:916–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sierles FS, Brodkey AC, Cleary LM, et al. Medical students’ exposure to and attitudes about drug company interactions: a national survey. JAMA. 2005;294:1034–1042. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.9.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vuorenkoski L, Valta M, Helve O. Effect of legislative changes in drug promotion on medical students: questionnaire survey. Med Educ. 2008;42:1172–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austad KE, Avorn J, Franklin JM, Kowal MK, Campbell EG, Kesselheim AS. Changing interactions between physician trainees and the pharmaceutical industry: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2361-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sah S, Loewenstein G. Effect of reminders of personal sacrifice and suggested rationalizations on residents’ self-reported willingness to accept gifts: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1204–1211. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pronin E, Gilovich T, Ross L. Objectivity in the eye of the beholder: divergent perceptions of bias in self versus others. Psychological Review. 2004;111:781–799. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.3.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinman MA, Shlipak MG, McPhee SJ. Of principles and pens: attitudes and practices of medicine housestaff toward pharmaceutical industry promotions. Am J Med. 2001;110:551–557. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00660-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283:373–380. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73:403–407. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kao AC, Braddock C, 3rd, Clay M, et al. Effect of educational interventions and medical school policies on medical students’ attitudes toward pharmaceutical marketing practices: a multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2011;86:1454–1462. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182303895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erb S. Medizinstudium: Verdächtige Geschenke. Die Zeit. www.zeit.de/2012/13/C-Medizin. (Last accessed on July 8th, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim A, Mumm LA, Korenstein D. Routine conflict of interest disclosure by preclinical lecturers and medical students’ attitudes toward the pharmaceutical and device industries. JAMA. 2012;308:2187–2189. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.25315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schott G, Pachl H, Limbach U, Gundert-Remy U, Ludwig WD, Lieb K. The financing of drug trials by pharmaceutical companies and its consequences. Part 1. A qualitative, systematic review of the literature on possible influences on the findings, protocols, and quality of drug trials. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(16):279–285. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schott G, Pachl H, Limbach U, Gundert-Remy U, Lieb K, Ludwig WD. The financing of drug trials by pharmaceutical companies and its consequences. Part 2. A qualitative, systematic review of the literature on possible influences on authorship, access to trial data, and trial registration and publication. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(17):295–301. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]