Abstract

Human oncogenic viruses are defined as necessary but not sufficient to initiate cancer. Experimental evidence suggests that the oncogenic potential of a virus is effective in cells that have already accumulated a number of genetic mutations leading to cell cycle deregulation. Current models for viral driven oncogenesis cannot explain why tumor development in carriers of tumorigenic viruses is a very rare event, occurring decades after virus infection. Considering that viruses are mutagenic agents per se and human oncogenic viruses additionally establish latent and persistent infections, we attempt here to provide a general mechanism of tumor initiation both for RNA and DNA viruses, suggesting viruses could be both necessary and sufficient in triggering human tumorigenesis initiation. Upon reviewing emerging evidence on the ability of viruses to induce DNA damage while subverting the DNA damage response and inducing epigenetic disturbance in the infected cell, we hypothesize a general, albeit inefficient hit and rest mechanism by which viruses may produce a limited reservoir of cells harboring permanent damage that would be initiated when the virus first hits the cell, before latency is established. Cells surviving virus generated damage would consequently become more sensitive to further damage mediated by the otherwise insufficient transforming activity of virus products expressed in latency, or upon episodic reactivations (viral persistence). Cells with a combination of genetic and epigenetic damage leading to a cancerous phenotype would emerge very rarely, as the probability of such an occurrence would be dependent on severity and frequency of consecutive hit and rest cycles due to viral reinfections and reactivations.

Keywords: Virus, Carcinogenesis, Tumor, Oncogene, Latency, Viral persistence

Core tip: Current models for viral driven oncogenesis cannot explain why tumor development in carriers of tumorigenic viruses is a very rare event, occurring decades after virus infection. Considering that viruses are mutagenic agents per se and human oncogenic viruses additionally establish latent and persistent infections, we attempt here to provide a general mechanism of tumor initiation both for RNA and DNA viruses, suggesting viruses could be both necessary and sufficient in triggering human tumorigenesis initiation.

TUMORS AND VIRUSES

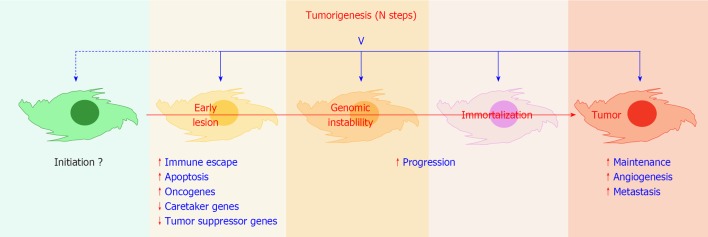

According to currently accepted estimates, viruses are etiologically linked to 15%-20% of all cancer cases worldwide[1-3]. Although many animal and human viruses can transform cells upon infection, only six human viruses are consistently associated with the onset of tumors in man, namely human papillomavirus (HPV), human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Table 1). A large share of what is known about the molecular mechanisms of oncogenesis is due to studies of tumor viruses, defined thereof as viruses carrying in their genome one copy of an oncogene or of an anti-oncogene or viruses that can alter the expression of the cellular version of one such gene[4]. Viruses have been shown to influence tumor sustainment and progression and induce escape pathways from apoptosis and immune surveillance[1,4], however in no case has it been proven that a virus can be the initiator, the primum movens, and not merely an “influential passenger” of a tumor (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Oncogenic viruses are latent/persistent viruses

| Virus | EBV | HHV-8 | HPV | HBV | HCV | HTLV-1 |

| Associated tumor(s): viral protein(s) expressed | BL: EBNA-1 | KS: vFLIP, vCYC, LANA-1 | Anogenital, oral, skin and laryngeal cancers: E6, E7 | HCC: HBx | HCC: CP10, NS3, NS5 | ATL: tax |

| NPC, TCL: EBNA1 + LMP1 | PEL, MCD: vFLIP, vCYC, LANA-1, LANA-2, vIL-6 | |||||

| HL: EBNA1 + LMP1-2 | ||||||

| PTLD: EBNA1-6 + LMP1-2 | ||||||

| Persistency | Always | Always | 20% infected subjects | 90%-95% infected newborns | 70%-85% infected subjects | Always |

| 5% infected adults | ||||||

| Period between infection and tumor onset | 10-20 yr | 10-20 yr | 5-20 yr | 10-30 yr | 10-30 yr | 20-30 yr |

EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; HHV-8: Human herpesvirus 8, also named Kaposi sarcoma virus; HPV: Human papillomavirus; HBV: Hepatatis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HTLV-1: Human T-cell leukemia virus 1; BL: Burkitt lymphoma; NPC: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma; TCL: T cell lymphoma; HL: Hodgkin lymphoma; PTLD: Posttransplant lymphoprolipherative disorder; KS: Kaposi sarcoma; PEL: Primary effusion lymphoma; MCD: Multicentric Castleman’s disease; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; ATL: Adult T-cell leukemia.

Figure 1.

Viral infection and tumorigenesis. Viruses have been shown to encode functions that can modulate all crucial steps towards tumor development, with the exception of the initiation step(s). Recognized contributions of viral infection are mentioned in blue letters. V: Virus. Red arrowheads up, stimulation; down, inhibition.

TUMORS AND GENES

Tumor development is believed to be a multistep process leading to the accumulation of permanent genetic damage[5], affecting either oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, or stability genes[6,7]. Cancer is therefore essentially a genetic disease, and a crucial observation in understanding multistep carcinogenesis is that the vast number and the coarse/crude nature of chromosomal defects that are present in the majority of tumor cells[8], are not amenable to an altered mutation rate in these cells[9,10]. In fact, most human solid tumors are characterized by an abnormal chromosome content, aneuploidy, which can be caused by genetic instability[8,11,12]. In addition, distinct and inheritable gene expression and phenotypic states that arise independently from changes in DNA sequence, known as epigenetic modifications, are also linked to tumor formation and progression[13,14]. On the whole, mechanisms for the initiation of tumorigenesis leading to genetic instability are on the whole poorly understood, both for virus induced and virus unrelated tumors[6].

CAN VIRUSES INITIATE GENETIC INSTABILITY

It has been known for more than four decades that members of different virus families can induce chromosome damage in infected cells in vitro[15], and chromosome breakages have been observed in leukocytes isolated from patients experiencing systemic viral active infections[16,17]. In recent years evidence has accumulated indicating the ability of different viruses to induce aberrant mitosis, genetic instability and interfere with cellular DNA repair pathways, which has confirmed early reports[18-21]. Recent data suggest that viruses induce permanent damage in the genome of infected cells in the context of their natural infection[22,23], and are capable of chromatin manipulation and epigenetic reprogramming of host expression patterns[24,25]; it remains to be seen whether this could stimulate tumor initiation.

It is well known that viruses can transform non-permissive cells and several human viruses cause tumors if introduced in experimental animals. Interestingly all of the six human oncogenic viruses are able to establish latent and persistent infections (Table 1). Chronic HBV, HCV and EBV infections, persistent infection with HTLV-1, prolonged exposures or frequent reactivations of HPV and HHV-8 associated with clinical conditions, are all epidemiologically linked to increased risk of developing virus related malignancies[26-32]. Failure to eliminate emerging tumor cells because of impaired immune function alone cannot account for this increased risk, since tumors develop in a minority of immune depressed patients. Furthermore tumor cells emerge very rarely from in vitro virally transformed cell lines, growing in the absence of immune selective pressure[33]. When they do, these tumors are not associated with genetic instability[34]. Therefore there is a missing causative factor acting in the setting of persistent infections, generally thought of as non viral carcinogens or host responses[35]. We propose that reiteration and severity of infections/reactivations is a key factor that possibly generates primary genetic and epigenetic damage on which viral oncogenes may add up their own oncogenic activities.

A MECHANISM FOR TUMOR INITIATION IN VIRAL PERSISTENCE

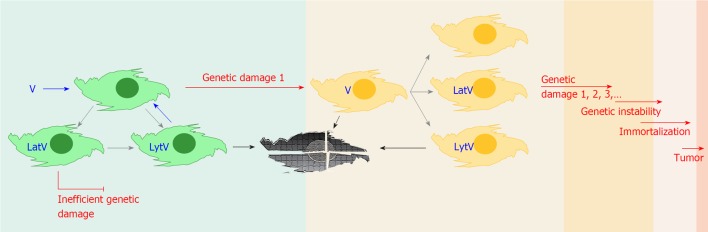

Viral persistence can be achieved by continuous replication, latency or both. Several virus-encoded products have been associated with transforming and/or oncomodulatory activities[4], and with the ability to induce chromosome damage, abnormal mitosis and genetic instability when expressed in cell cultures (Table 2)[18,36-38]. Recent findings point to viral proteins interfering with the epigenetic milieu of the infected cells, leading to the transcriptional repression of tumor suppressor genes, and interference with cell cycling control[39] (Table 3). However in vivo these activities must be particularly inefficient if one considers that the majority of the human population carries a number of resident viruses, but only a minority among infected individuals will develop tumors that can be correlated with persistent viral infections, and generally after very long latency periods (years to decades)[4,35]. It should be noted that latency is characterized by a relatively low viral transcriptional rate[40,41], that one can define as “a virus at rest”: this could explain why damaging and/or destabilizing activities of latent gene products have little chance to induce permanent effects in cells equipped with an intact set of caretaker genes, antioncogenes, and non activated oncogenes. Consistently, subjects with Fanconi’s anemia, an inherited disease with defective DNA repair, have up to 4000 times increased risk of developing solid papillomavirus-associated tumors[4]. In fact cell immortalization has been achieved experimentally only following expression of latent genes in the context of previously accumulated mutations in the cellular genome[18,20]. On the other hand, lytically infected cells are typically characterized by massive transcription of the viral genome, a “hit”. These cells develop virus induced chromosome damage and can undergo abnormal mitosis (Table 2), both in vitro and in vivo[16]. So here we have two observations where there is apparently little if any effect on the genetic stability of healthy cells in vivo: (1) latency functions can transform cells but cause genetic instability only in already genetically damaged cells; and (2) lytic functions may induce genetic instability but kill the cells. Is there a setting in which these two phenomena may lead to an outcome that has been overlooked The phase immediately following virus entry into a permissive cell, before the fate of the infection (lytic or latent) is set (green cells in Figure 2), may be crucial in this regard.

Table 2.

Viral proteins inducing genetic damage

| Virus | EBV | HHV-8 | HPV | HBV | HCV | HTLV-1 |

| Latent proteins | EBNA-1 | LANA-1[64] | E6, E7[66,67] | Naturally occurring pre-S mutants[68] | - | - |

| EBNA-3C | v-CYC[65] | |||||

| LMP-1[63] | ||||||

| Lytic proteins | BZLF-1[69] | - | E1, E2[71,72] | HBx[73,74] | Core | Tax[76,77] |

| BGLF-5[70] | NS3[23,62] | |||||

| NS5[75] |

EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; HHV-8: Human herpesvirus 8, also named Kaposi sarcoma virus; HPV: Human papillomavirus; HBV: Hepatatis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HTLV-1: Human T-cell leukemia virus 1.

Table 3.

Virus products controlling cellular epigenetic modifications

| Virus | EBV | HHV-8 | HPV | HBV | HCV | HTLV-1 |

| EBNA-3A, EBNA-3C[78] | LANA-1[81] | E6[83] | HBx[85,86] | Core[87] | Tax[88] | |

| LMP-1[79] | microRNA[82] | E7[84] | ||||

| LMP-2[80] |

EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; HHV-8: Human herpesvirus 8, also named Kaposi sarcoma virus; HPV: Human papillomavirus; HBV: Hepatatis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HTLV-1: Human T-cell leukemia virus 1.

Figure 2.

Tumor initiation events mediated by virus induced genetic damage. Virus entry into permissive genetically intact cells (green cells), can result in lytic replication or latency. In the latter setting the oncogenic potential of latent genes appears ineffective in vivo. Before silencing of most virus specific transcription is achieved, various viral functions are expressed which could induce genetic/epigenetic damage in a fraction of the infected population (red arrows, genetic damage 1). Cells surviving to sustainable damage (orange cells) could experience reactivation of the virus, host the virus genome in a latent state, or lose it after uneven segregation of their genetic material. In damaged cells latent gene products could now represent an effective oncogenic threat if cellular caretaker genes have been affected (red arrow, genetic damage 1, 2, 3…). Reinfection or reactivation of latent virus in damaged cells could result in further genetic offense, eventually leading to genetic instability, immortalization and tumor development. V: Virus; Lat: Latent; Lyt: Lytic. Blue arrows: Infection; Grey arrows: Consequences of infections; Black arrows: Death.

Latency is defined as an infection where the production of infectious virus does not occur immediately but the virus retains the potential to initiate productive infection at a later time, and is characterized by a unique transcriptional and translational state of the virus, the latency expression program, in which the productive replication cycle is not operative[4]. Hence latency can be regarded as a transitory state of resistance of the infected cell to a virus, and the latency program as the result of a negotiation between virus and host, after a battle between cellular functions reacting to the incoming virus and virus encoded functions, expressed at early stages following virus entry into the host cell. The first consequence of this definition is that latency is not a default life program for a virus, but a survival condition that a virus is forced to opt for when the infected cell does not allow progression of the lytic cycle. A second consequence is that there is not one strictly planned latency program for any given virus, but the latency program is defined depending on the context of host cell gene expression, after the cell succeeds converting a viral hit into a virus at rest by resisting to the initial round of lytic cycle gene transcription, and forces the virus into the latency state, for some time. This state of resistance can last for very different periods of time, depending on the moment viral reactivation will be allowed by the infected cell, and can be long lasting, when reactivation occurs upon transition into a new cell differentiation state, or last an unpredictable period of time, as in cells entering a particular metabolic state triggered by an infrequent external signal (ultraviolet radiations, stress, etc.), or cells being in a particular phase of the cell cycle[42], which could be a frequent event for rapidly replicating cells or a very infrequent event for slowly replicating cells, as for liver cells. Recent evidence reveals that in an EBV latency model lytic genes can be transcribed to considerable levels[43], contrary to what had been thought previously. Similarly in Kaposi sarcoma virus associated tumors, subpopulations of cells express lytic gene products within a general latency setting[44], suggesting the distinction between latency and lytic transcription is less clear cut than expected. But what happens between viral entry into a cell and the establishment of latency in that cell Very few studies have addressed this issue, but available data indicate that during this time lapse the majority of the viral genome is transcriptionally active, with many lytic genes being expressed in very much the same way as during early phases of lytic infection, before transcriptions are silenced by the host cell[45,46]. This delicate, vastly unexplored resistant period may represent a particularly vulnerable setting for the infected host, acting as a non-permissive cell, a well known target for virus transformation[1,47]. Therefore the actual phase between virus entry and the establishment of latency is a stage where some viral genes, whether belonging to the latent or the lytic expression program, can be expressed to various levels. Additionally, this is a time where the structure of the incoming virus disaggregates within the cell, releasing dozens of structural proteins and enzymes, genomic nucleic acids, coding and non coding RNAs, encapsidated in infectious particles. In fact it is now clear that the presence of incoming viral genomes relocates DNA repair proteins at sites of viral genome deposition[48]. Several virus products are able to induce genetic damage (Table 2), and examples of encapsidated DNA nicking activities with a potential role in chromosomal damage have been reported[49,50]. Other viral proteins can interfere with the cellular DNA repair machinery (see[51] for a detailed review) or introduce transcriptional-silencing marks[39]. All these activities could in this context generate primary damage events, leaving the cell with permanent genetic and epigenetic damage before entering into latency. The ensuing latency program would now run in a cell bearing a modified genome.

Although it would be reasonable to expect that the majority of damaged cells could not survive the insult, it would be equally reasonable to expect that cells with sustainable damage may survive, as it is documented in vitro in non-permissive cells[19,52] and in cells undergoing chemically induced DNA breaks and chromosome pulverization[53].

A surviving cell could be imagined as acquiring a genotype with no phenotypic consequences on the virus, in which case the virus would either proceed with the lytic cycle and kill the cell or enter a latent state (rest), according to the virus and the type of infected cell (Figure 2). Alternatively genetic/epigenetic damage could modify the permissivity of the cell to the infecting virus, either further supporting viral expression programs or restricting them. The consequences on lytic infections would be either more productive lytic cycles or their inhibition with possible elimination of the virus, respectively. On latent infections the expression profile of the genome could be affected, either positively, as observed in EBV positive NK/T-cell lymphoma[54], or negatively as it is observed when EBV latently infected B cells switch from the latency III (whole set of latency products expressed) to latency I (EBNA-1 only) following transformation into lymphoblastoid cells. Viral gene expression would now take place in the context of a genetically modified cell, and in some instances this combination could provide damaged cells with a selective advantage in their environment, making them fitter to survive such damage and ready for the accumulation of future genetic modifications, in other words placing them on the road to malignancy.

IS THE VIRUS LATENCY/REACTIVATION CYCLE AN ONCOGENIC THREAT

While a single hit and rest event has little chance to set the stage for cancer initiation, repeated cycles of viral infection or reactivation and latency would increase the number of possibly genetically damaged cells in the host and eventually produce cells accumulating a number of chromosomal abnormalities, as recently observed in an in vitro model by Fang et al[55]. If the damage has modified or abolished the activity of caretaker genes, oncogenes or anti-oncogenes, then the genome damaging and/or destabilizing activities of viral latent gene products could now meet the requirements for the introduction of additional permanent damage, eventually leading to genetic instability. When the combination of hit and rest related damage reached a critical point, let’s say telomerase activation, the cell could become immortal and virus functions may become dispensable. Further damage due to genetic instability could lead finally to the emergence of a tumor cell (Figure 2). If the present hypothesis was confirmed, one consequence would be that the number of viruses with potential for tumor initiation would be larger than that currently accepted. A further consequence of the present hypothesis is that preventing virus reactivations, where possible by pharmacologic prophylaxis or medical modulation of the immune response, should counteract cancer development.

TESTING THE HYPOTHESIS

The demonstration that genetic and epigenetic damage occurs in latently infected cells and that some damaged cells survive in the setting of natural infections is crucial in validating our hypothesis. It would therefore be important to investigate the process whilst it is occurring. It is conceivable to plan prospective studies of patient populations at risk for recurrent or persistent viral infections. The genetic integrity of cells latently or persistently infected by a given virus could be studied using methods applicable to a large number of samples and correlated with virus shed at the site of sampling. For example the analysis of DNA damage could be associated with HPV isolation at the time of pap test screening, or with EBV viral load determination in the follow-up of transplant patients[28]. Retrospective and prospective studies could be implemented, analyzing possible correlation between frequency of different virus reactivations, severity of these reactivations, evidence of genetic damage in cells that harbor latent viruses and development of malignancies, in order to better define the importance of evocative findings[56]: ideal candidates for these studies would be populations of immunocompromised patients such as those in post-transplant settings[57]. Chronic infections, clinically manifest or subclinical, are an additional interesting condition for virus related DNA damage investigation[37]. In this setting the measurement of chromosomal abnormalities in peripheral blood lymphocytes should result particularly fruitful, if one considers that circulating cells are exposed to infectious agents even in localized infections during tissue perfusion[23,58,59].

Precious information would be generated through the analysis of pre-tumoral and tumoral banked samples, where the observation of abnormal mitosis and genetic abnormalities can be associated with the identification of virus related antigens or nucleic acids[60], while prospective studies could include virus isolation. As an example, hepatic biopsies from non-responders to anti-HCV treatment could be analyzed for the presence of genetic abnormalities and the findings would be compared to responders in relation to incidence of hepatocarcinoma development over time. In vitro studies should be devised choosing experimental settings that guarantee the closest simulation of authentic in vivo situations, cautiously choosing animal models and transformed cell lines, avoiding non human cell cultures, and laboratory strains of viruses[61]. Ideally fresh clinical virus isolates should be used to infect cells that are the authentic sites of latency in vivo, looking for consequences of virus infection on mitosis, chromosome integrity and the epigenetic stage.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Denis R, Ciotti M S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Carbone M, Klein G, Gruber J, Wong M. Modern criteria to establish human cancer etiology. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5518–5524. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duelli DM, Padilla-Nash HM, Berman D, Murphy KM, Ried T, Lazebnik Y. A virus causes cancer by inducing massive chromosomal instability through cell fusion. Curr Biol. 2007;17:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, Plummer M. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607–615. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knipe DM, Howley PM. Fields virology. 5th ed. 2 Vols. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armitage P, Doll R. The age distribution of cancer and a multi-stage theory of carcinogenesis. Br J Cancer. 1954;8:1–12. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1954.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 2004;10:789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasser S, Raulet D. The DNA damage response, immunity and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:344–347. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998;396:643–649. doi: 10.1038/25292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomlinson IP, Novelli MR, Bodmer WF. The mutation rate and cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14800–14803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loeb LA, Loeb KR, Anderson JP. Multiple mutations and cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:776–781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0334858100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sieber OM, Heinimann K, Tomlinson IP. Genomic instability--the engine of tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:701–708. doi: 10.1038/nrc1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loeb LA. A mutator phenotype in cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3230–3239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baylin SB, Ohm JE. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer - a mechanism for early oncogenic pathway addiction. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:107–116. doi: 10.1038/nrc1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandoval J, Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: beyond genomics. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortunato EA, Spector DH. Viral induction of site-specific chromosome damage. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:21–37. doi: 10.1002/rmv.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nichols WW. Virus-induced chromosome abnormalities. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1970;24:479–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.24.100170.002403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossi S, Sumberaz A, Gosmar M, Mattioli F, Testino G, Martelli A. DNA damage in peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients with cirrhosis related to alcohol abuse or to hepatitis B and C viruses. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:22–25. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f163fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gatza ML, Chandhasin C, Ducu RI, Marriott SJ. Impact of transforming viruses on cellular mutagenesis, genome stability, and cellular transformation. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2005;45:304–325. doi: 10.1002/em.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duelli DM, Hearn S, Myers MP, Lazebnik Y. A primate virus generates transformed human cells by fusion. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:493–503. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Münger K, Hayakawa H, Nguyen CL, Melquiot NV, Duensing A, Duensing S. Viral carcinogenesis and genomic instability. EXS. 2006:179–199. doi: 10.1007/3-7643-7378-4_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weitzman MD, Lilley CE, Chaurushiya MS. Changing the ubiquitin landscape during viral manipulation of the DNA damage response. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2897–2906. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urazova OI, Litvinova LS, Novitskii VV, Pomogaeva AP. Cytogenetic impairments of peripheral blood lymphocytes during infectious mononucleosis. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2001;131:392–393. doi: 10.1023/a:1017976808339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machida K, McNamara G, Cheng KT, Huang J, Wang CH, Comai L, Ou JH, Lai MM. Hepatitis C virus inhibits DNA damage repair through reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and by interfering with the ATM-NBS1/Mre11/Rad50 DNA repair pathway in monocytes and hepatocytes. J Immunol. 2010;185:6985–6998. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flanagan JM. Host epigenetic modifications by oncogenic viruses. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:183–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein RA. Epigenetics--the link between infectious diseases and cancer. JAMA. 2011;305:1484–1485. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guidotti LG, Chisari FV. Immunobiology and pathogenesis of viral hepatitis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:23–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakrabarty SP, Murray JM. Modelling hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Theor Biol. 2012;305:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bierkens M, Wilting SM, van Wieringen WN, van Kemenade FJ, Bleeker MC, Jordanova ES, Bekker-Lettink M, van de Wiel MA, Ylstra B, Meijer CJ, et al. Chromosomal profiles of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia relate to duration of preceding high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:E579–E585. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isobe Y, Aritaka N, Setoguchi Y, Ito Y, Kimura H, Hamano Y, Sugimoto K, Komatsu N. T/NK cell type chronic active Epstein-Barr virus disease in adults: an underlying condition for Epstein-Barr virus-associated T/NK-cell lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:278–282. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okano M, Gross TG. Acute or chronic life-threatening diseases associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Am J Med Sci. 2012;343:483–489. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318236e02d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuoka M, Jeang KT. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) and leukemic transformation: viral infectivity, Tax, HBZ and therapy. Oncogene. 2011;30:1379–1389. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganem D. KSHV infection and the pathogenesis of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:273–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugimoto M, Tahara H, Ide T, Furuichi Y. Steps involved in immortalization and tumorigenesis in human B-lymphoblastoid cell lines transformed by Epstein-Barr virus. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3361–3364. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimonjic D, Brooks MW, Popescu N, Weinberg RA, Hahn WC. Derivation of human tumor cells in vitro without widespread genomic instability. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8838–8844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLaughlin-Drubin ME, Munger K. Viruses associated with human cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1782:127–150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duensing S, Münger K. Mechanisms of genomic instability in human cancer: insights from studies with human papillomavirus oncoproteins. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:157–162. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGivern DR, Lemon SM. Virus-specific mechanisms of carcinogenesis in hepatitis C virus associated liver cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:1969–1983. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaurushiya MS, Weitzman MD. Viral manipulation of DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoints. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:1166–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paschos K, Allday MJ. Epigenetic reprogramming of host genes in viral and microbial pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirchner EA, Bornkamm GW, Polack A. Transcriptional activity across the Epstein-Barr virus genome in Raji cells during latency and after induction of an abortive lytic cycle. J Gen Virol. 1991;72(Pt 10):2391–2398. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-10-2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maran A, Amella CA, Di Lorenzo TP, Auborn KJ, Taichman LB, Steinberg BM. Human papillomavirus type 11 transcripts are present at low abundance in latently infected respiratory tissues. Virology. 1995;212:285–294. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarid R, Wiezorek JS, Moore PS, Chang Y. Characterization and cell cycle regulation of the major Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) latent genes and their promoter. J Virol. 1999;73:1438–1446. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1438-1446.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arvey A, Tempera I, Tsai K, Chen HS, Tikhmyanova N, Klichinsky M, Leslie C, Lieberman PM. An atlas of the Epstein-Barr virus transcriptome and epigenome reveals host-virus regulatory interactions. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nador RG, Milligan LL, Flore O, Wang X, Arvanitakis L, Knowles DM, Cesarman E. Expression of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor monocistronic and bicistronic transcripts in primary effusion lymphomas. Virology. 2001;287:62–70. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krishnan HH, Naranatt PP, Smith MS, Zeng L, Bloomer C, Chandran B. Concurrent expression of latent and a limited number of lytic genes with immune modulation and antiapoptotic function by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus early during infection of primary endothelial and fibroblast cells and subsequent decline of lytic gene expression. J Virol. 2004;78:3601–3620. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3601-3620.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ciufo DM, Cannon JS, Poole LJ, Wu FY, Murray P, Ambinder RF, Hayward GS. Spindle cell conversion by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: formation of colonies and plaques with mixed lytic and latent gene expression in infected primary dermal microvascular endothelial cell cultures. J Virol. 2001;75:5614–5626. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5614-5626.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.zur Hausen H. Proliferation-inducing viruses in non-permissive systems as possible causes of human cancers. Lancet. 2001;357:381–384. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03652-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lilley CE, Chaurushiya MS, Boutell C, Everett RD, Weitzman MD. The intrinsic antiviral defense to incoming HSV-1 genomes includes specific DNA repair proteins and is counteracted by the viral protein ICP0. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002084. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landini MP, Ripalti A. A DNA-nicking activity associated with the nucleocapsid of human cytomegalovirus. Arch Virol. 1982;73:351–356. doi: 10.1007/BF01318089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berthet C, Raj K, Saudan P, Beard P. How adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein arrests cells completely in S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13634–13639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504583102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weitzman MD, Lilley CE, Chaurushiya MS. Genomes in conflict: maintaining genome integrity during virus infection. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:61–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bystrevskaya VB, Lobova TV, Smirnov VN, Makarova NE, Kushch AA. Centrosome injury in cells infected with human cytomegalovirus. J Struct Biol. 1997;120:52–60. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crasta K, Ganem NJ, Dagher R, Lantermann AB, Ivanova EV, Pan Y, Nezi L, Protopopov A, Chowdhury D, Pellman D. DNA breaks and chromosome pulverization from errors in mitosis. Nature. 2012;482:53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature10802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, Ohyashiki JH, Takaku T, Shimizu N, Ohyashiki K. Transcriptional profiling of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) genes and host cellular genes in nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma and chronic active EBV infection. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:599–608. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fang CY, Lee CH, Wu CC, Chang YT, Yu SL, Chou SP, Huang PT, Chen CL, Hou JW, Chang Y, et al. Recurrent chemical reactivations of EBV promotes genome instability and enhances tumor progression of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2016–2025. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manabe A, Yoshimasu T, Ebihara Y, Yagasaki H, Wada M, Ishikawa K, Hara J, Koike K, Moritake H, Park YD, et al. Viral infections in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: prevalence and clinical implications. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26:636–641. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000140653.50344.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adani GL, Baccarani U, Lorenzin D, Gropuzzo M, Tulissi P, Montanaro D, Currö G, Sainz M, Risaliti A, Bresadola V, et al. De novo gastrointestinal tumours after renal transplantation: role of CMV and EBV viruses. Clin Transplant. 2006;20:457–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhargava A, Raghuram GV, Pathak N, Varshney S, Jatawa SK, Jain D, Mishra PK. Occult hepatitis C virus elicits mitochondrial oxidative stress in lymphocytes and triggers PI3-kinase-mediated DNA damage response. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1806–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bhargava A, Khan S, Panwar H, Pathak N, Punde RP, Varshney S, Mishra PK. Occult hepatitis B virus infection with low viremia induces DNA damage, apoptosis and oxidative stress in peripheral blood lymphocytes. Virus Res. 2010;153:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guzmán P, Sotelo-Regil RC, Mohar A, Gonsebatt ME. Positive correlation between the frequency of micronucleated cells and dysplasia in Papanicolaou smears. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2003;41:339–343. doi: 10.1002/em.10160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pfuhler S, Fellows M, van Benthem J, Corvi R, Curren R, Dearfield K, Fowler P, Frötschl R, Elhajouji A, Le Hégarat L, et al. In vitro genotoxicity test approaches with better predictivity: summary of an IWGT workshop. Mutat Res. 2011;723:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Machida K, Cheng KT, Sung VM, Lee KJ, Levine AM, Lai MM. Hepatitis C virus infection activates the immunologic (type II) isoform of nitric oxide synthase and thereby enhances DNA damage and mutations of cellular genes. J Virol. 2004;78:8835–8843. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8835-8843.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gruhne B, Sompallae R, Masucci MG. Three Epstein-Barr virus latency proteins independently promote genomic instability by inducing DNA damage, inhibiting DNA repair and inactivating cell cycle checkpoints. Oncogene. 2009;28:3997–4008. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Si H, Robertson ES. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded latency-associated nuclear antigen induces chromosomal instability through inhibition of p53 function. J Virol. 2006;80:697–709. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.697-709.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verschuren EW, Hodgson JG, Gray JW, Kogan S, Jones N, Evan GI. The role of p53 in suppression of KSHV cyclin-induced lymphomagenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:581–589. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duensing S, Münger K. The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins independently induce numerical and structural chromosome instability. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7075–7082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patel D, McCance DJ. Compromised spindle assembly checkpoint due to altered expression of Ubch10 and Cdc20 in human papillomavirus type 16 E6- and E7-expressing keratinocytes. J Virol. 2010;84:10956–10964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00259-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hsieh YH, Su IJ, Wang HC, Chang WW, Lei HY, Lai MD, Chang WT, Huang W. Pre-S mutant surface antigens in chronic hepatitis B virus infection induce oxidative stress and DNA damage. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:2023–2032. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adamson AL. Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 protein binds to mitotic chromosomes. J Virol. 2005;79:7899–7904. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7899-7904.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu CC, Liu MT, Chang YT, Fang CY, Chou SP, Liao HW, Kuo KL, Hsu SL, Chen YR, Wang PW, et al. Epstein-Barr virus DNase (BGLF5) induces genomic instability in human epithelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1932–1949. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bellanger S, Blachon S, Mechali F, Bonne-Andrea C, Thierry F. High-risk but not low-risk HPV E2 proteins bind to the APC activators Cdh1 and Cdc20 and cause genomic instability. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1608–1615. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.11.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kadaja M, Sumerina A, Verst T, Ojarand M, Ustav E, Ustav M. Genomic instability of the host cell induced by the human papillomavirus replication machinery. EMBO J. 2007;26:2180–2191. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Livezey KW, Negorev D, Simon D. Increased chromosomal alterations and micronuclei formation in human hepatoma HepG2 cells transfected with the hepatitis B virus HBX gene. Mutat Res. 2002;505:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Matsuda Y, Ichida T. Impact of hepatitis B virus X protein on the DNA damage response during hepatocarcinogenesis. Med Mol Morphol. 2009;42:138–142. doi: 10.1007/s00795-009-0457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baek KH, Park HY, Kang CM, Kim SJ, Jeong SJ, Hong EK, Park JW, Sung YC, Suzuki T, Kim CM, et al. Overexpression of hepatitis C virus NS5A protein induces chromosome instability via mitotic cell cycle dysregulation. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chlichlia K, Khazaie K. HTLV-1 Tax: Linking transformation, DNA damage and apoptotic T-cell death. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;188:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Majone F, Jeang KT. Unstabilized DNA breaks in HTLV-1 Tax expressing cells correlate with functional targeting of Ku80, not PKcs, XRCC4, or H2AX. Cell Biosci. 2012;2:15. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Skalska L, White RE, Franz M, Ruhmann M, Allday MJ. Epigenetic repression of p16(INK4A) by latent Epstein-Barr virus requires the interaction of EBNA3A and EBNA3C with CtBP. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000951. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tsai CN, Tsai CL, Tse KP, Chang HY, Chang YS. The Epstein-Barr virus oncogene product, latent membrane protein 1, induces the downregulation of E-cadherin gene expression via activation of DNA methyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10084–10089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152059399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hino R, Uozaki H, Murakami N, Ushiku T, Shinozaki A, Ishikawa S, Morikawa T, Nakaya T, Sakatani T, Takada K, et al. Activation of DNA methyltransferase 1 by EBV latent membrane protein 2A leads to promoter hypermethylation of PTEN gene in gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2766–2774. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Di Bartolo DL, Cannon M, Liu YF, Renne R, Chadburn A, Boshoff C, Cesarman E. KSHV LANA inhibits TGF-beta signaling through epigenetic silencing of the TGF-beta type II receptor. Blood. 2008;111:4731–4740. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu F, Stedman W, Yousef M, Renne R, Lieberman PM. Epigenetic regulation of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency by virus-encoded microRNAs that target Rta and the cellular Rbl2-DNMT pathway. J Virol. 2010;84:2697–2706. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01997-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rincon-Orozco B, Halec G, Rosenberger S, Muschik D, Nindl I, Bachmann A, Ritter TM, Dondog B, Ly R, Bosch FX, et al. Epigenetic silencing of interferon-kappa in human papillomavirus type 16-positive cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8718–8725. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Laurson J, Khan S, Chung R, Cross K, Raj K. Epigenetic repression of E-cadherin by human papillomavirus 16 E7 protein. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:918–926. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee JO, Kwun HJ, Jung JK, Choi KH, Min DS, Jang KL. Hepatitis B virus X protein represses E-cadherin expression via activation of DNA methyltransferase 1. Oncogene. 2005;24:6617–6625. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Park IY, Sohn BH, Yu E, Suh DJ, Chung YH, Lee JH, Surzycki SJ, Lee YI. Aberrant epigenetic modifications in hepatocarcinogenesis induced by hepatitis B virus X protein. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1476–1494. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zeng B, Li Z, Chen R, Guo N, Zhou J, Zhou Q, Lin Q, Cheng D, Liao Q, Zheng L, et al. Epigenetic regulation of miR-124 by hepatitis C virus core protein promotes migration and invasion of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cells by targeting SMYD3. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:3271–3278. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tomita M, Tanaka Y, Mori N. MicroRNA miR-146a is induced by HTLV-1 tax and increases the growth of HTLV-1-infected T-cells. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2300–2309. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]