Abstract

The Ashkenazi Jewish population has a several-fold higher prevalence of Crohn’s disease compared to non-Jewish European ancestry populations and has a unique genetic history. Haplotype association is critical to Crohn’s disease etiology in this population, most notably at NOD2, in which three causal, uncommon, and conditionally independent NOD2 variants reside on a shared background haplotype. We present an analysis of extended haplotypes which showed significantly greater association to Crohn’s disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish population compared to a non-Jewish population (145 haplotypes and no haplotypes with P-value < 10−3, respectively). Two haplotype regions, one each on chromosomes 16 and 21, conferred increased disease risk within established Crohn’s disease loci. We performed exome sequencing of 55 Ashkenazi Jewish individuals and follow-up genotyping focused on variants in these two regions. We observed Ashkenazi Jewish-specific nominal association at R755C in TRPM2 on chromosome 21. Within the chromosome 16 region, R642S of HEATR3 and rs9922362 of BRD7 showed genome-wide significance. Expression studies of HEATR3 demonstrated a positive role in NOD2-mediated NF-κB signaling. The BRD7 signal showed conditional dependence with only the downstream rare Crohn’s disease-causal variants in NOD2, but not with the background haplotype; this elaborates NOD2 as a key illustration of synthetic association.

Keywords: haplotype association, Ashkenazi Jewish, Crohn’s disease, NF-κB signaling, synthetic association

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a complex genetic disorder characterized by chronic intestinal inflammation resulting from a dysregulated host immune response to intestinal microbiota.1 The NOD2 gene, involved in innate immune responses to bacterial peptidoglycan, is strongly associated with Crohn’s disease and was initially identified through genetic linkage.2 Uncommon, loss-of-function coding mutations (Arg702Trp, Gly908Arg, Leu1007fsinsC) in NOD2 confer a 17.1 fold (95% CI: 10.7 – 27.2) increased risk for disease with homozygous or compound heterozygote risk allele carriage.3 The advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has resulted in the identification of 140 loci with genome-wide significance in CD, implicating numerous immune mechanisms in disease pathogenesis. However, most identified loci involve variants of modest effects, and the presently identified 140 genetic loci account for only 13.6% of the estimated heritability.4

Because genotyping platforms utilized thus far have focused on common variants, it is possible that untested rare mutations may contribute significantly to complex disorders and account for some portion of missing heritability. Furthermore, precise models of disease pathogenesis integrating multiple disease associations are largely lacking, reflecting in part the significant pathophysiologic heterogeneity underlying the myriad associations reported thus far in Crohn’s disease. Approaches to reduce genetic complexity, such as through focused studies in selected populations, may be of benefit.

The Ashkenazi Jewish population has a several-fold higher prevalence of Crohn’s disease compared to non-Jewish European ancestry cohorts, with estimates of increased prevalence ranging between 4.3 to 7.7-fold.5,6 The Ashkenazim have a unique genetic history, characterized by population bottlenecks, expansions and endogamy.7 However, the associated polymorphisms identified thus far through genome-wide association studies, as well as at NOD2, do not account for the higher disease prevalence in the Ashkenazim. Although the basis for the increased frequency of CD in the Ashkenazim is not known, it is possible that unidentified, uncommon variants, unique to or at a higher frequency within Ashkenazi Jews, contribute to higher disease prevalence. An additional possibility, given the greater linkage disequilibrium observed within the Ashkenazim, is that multiple functional polymorphisms inherited in cis, contribute to disease more commonly within Ashkenazi Jewish compared to non-Jewish European ancestry populations. Such a configuration of mutations would be consistent with the well-documented presence of longer haplotype blocks with greater levels of linkage disequilibrium, relative to non-Jewish populations.8,9 As such, association testing to identify significant extended regions may point the way to understanding the unique genetic architecture underlying Crohn’s disease in Ashkenazi Jews.

Studying haplotype structure in the context of disease association also informs our conception of synthetic association, which has been hypothesized to be a major contributor to genome-wide association signals. Under this framework, molecular evolution, which creates varying amounts of haplotype diversity, allows for significant disease association near clusters of rare causal variants.10 For example, in CD, NOD2 is distinguished by three uncommon functional mutations whose carriers are a subset of individuals who have a common background haplotype.3,11 The multiple hierarchical levels in the tree-based genealogy originally proposed by Dickson, et al., are reflected in various stringencies for the clustering parameters in an analysis of contemporary haplotype diversity; for analyses with strict parameters, causal variants may not lie within the associated haplotypes themselves. Using haplotypes may be a particularly powerful approach for tagging functional variants; a recent study found that using a multi-marker method for predicting Crohn’s disease risk showed improved power over a single-variant approach.12 Toward this end, we present an analysis using extended shared haplotypes as a filter for prioritizing novel variants and detecting conditional dependence structure.

Results

Extended haplotype analysis

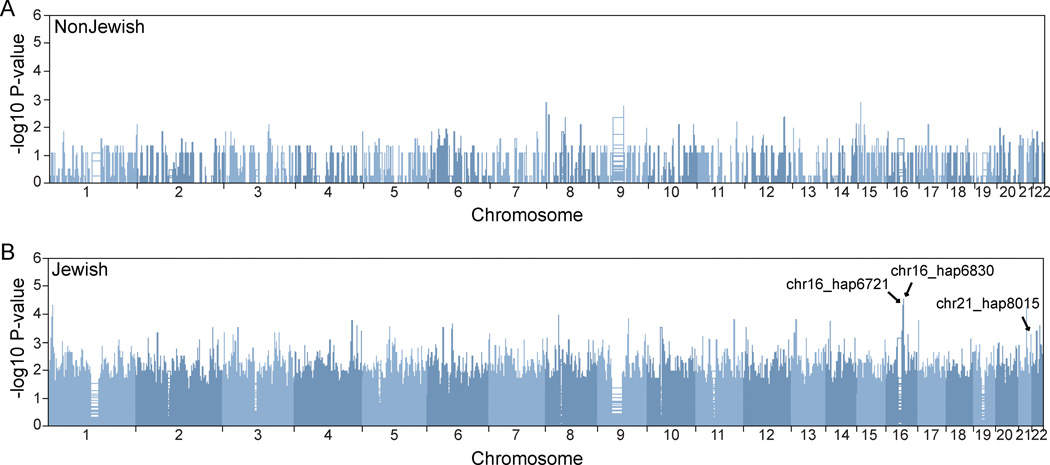

To address the presence and relevance to disease of extended linkage disequilibrium stretches, we performed a haplotype-based analysis of a cohort comprising 397 Ashkenazi Crohn’s disease cases and 431 controls, and 547 non-Ashkenazi Crohn’s disease cases and 549 controls.13,14 Our analysis of associated extended haplotypes showed that there were markedly distinct patterns of haplotype association signals in the Ashkenazim compared to the non-Jewish cohort (Figure 1). We observed 145 haplotypes demonstrating nominal evidence for association with P-values < 10−3, including three distinct regions with P-values < 10−4 (Supplementary Table 2). At this threshold, no regions were found to be significant in the non-Jewish cohort. Comparing the 145 haplotypes with 71 previously identified Crohn’s disease loci in a GWAS-based meta-analysis,15 we found that there were four haplotypes overlapping three established loci (Table 1); no haplotypes overlapped the 69 additional CD-associated loci in a larger Immunochip-based study.4 Among all loci, the most significant haplotype association signal was found at chromosome 16q12 in a region that includes the NOD2 gene. Three of these four haplotypes showed higher allele frequencies in Crohn’s disease cases, corresponding to increased disease risk, while the remaining haplotype on chromosome 2 appeared to confer a protective function.

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of haplotype associations in non-Ashkenazi Jewish (A) and Ashkenazi Jewish (B) European Ancestry cohorts. In the non-Jewish analysis, no regions demonstrated evidence for association. In contrast, in the Ashkenazim, we observed 145 haplotypes demonstrating nominal evidence for association with P-values < 10−3, including three distinct regions with P-values < 10−4. Associated haplotypes that overlapped with established CD loci, and which are detailed in Table 1, are labeled.

Table 1.

Associated haplotypes overlapping with established Crohn’s disease loci in Ashkenazi Jewish samples

| Haplotype association | Established CD loci (Mb) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotype ID | Chr1 | Start position1 | End position1 | P-value | MAF_Case2 (N =397) |

MAF_Ctrl2 (N =431) |

|

| chr2_hap10940 | 2 | 61 184 852 | 61 865 369 | 4.63 × 10−04 | 0.0038 | 0.024 | 60.76–61.87 |

| chr16_hap6721 | 16 | 48 885 095 | 49 184 879 | 5.04× 10−05 | 0.019 | 0 | 49.02–49.41 |

| chr16_hap6830 | 16 | 49 184 879 | 49 479 621 | 3.17× 10−05 | 0.032 | 0.0046 | 49.02–49.41 |

| chr21_hap8015 | 21 | 44 471 849 | 44 657 340 | 5.26 × 10−04 | 0.014 | 0 | 44.41–44.52 |

Chromosomal coordinates in hg 18.

MAF = minor allele frequency.

Chromosome 16 haplotypes

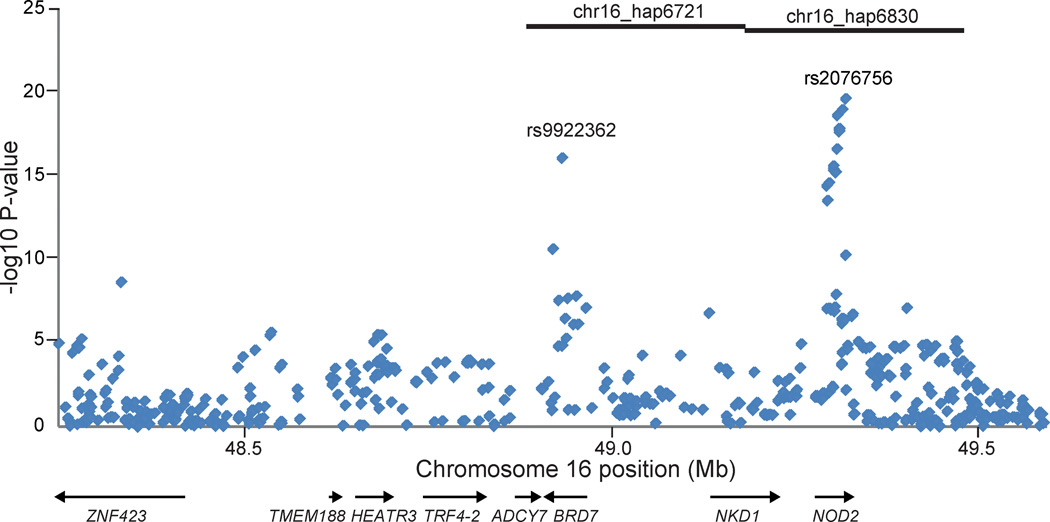

Two of the significant haplotypes in established CD loci (chr16_hap6721 and chr16_hap6830) were located contiguously on chromosome 16, spanning 48.88 – 49.18 and 49.18 – 49.48 Mb, respectively (Table 1). Haplotype chr16_hap6830 was carried by 25 Crohn’s disease Ashkenazi cases and 4 Ashkenazi controls, and chr16_hap6721 was carried by 15 Crohn’s disease cases and no controls. The 15 Crohn’s disease cases that carried chr16_hap6721 were completely a subset of the 25 cases that carried chr16_hap6721. Importantly, of these 15 Crohn’s disease extended haplotype carriers, 12 also carried the Gly908Arg polymorphism within the NOD2 gene. Of the three major disease-associated polymorphisms, only the Gly908Arg variant is present at a significantly higher frequency in Ashkenazi compared to non-Ashkenazi Crohn’s disease cases.16–22 NOD2 encodes an intracellular pathogen recognition receptor that functions as a sensor for peptidoglycan found in the cell wall of most bacteria. In response to stimulation by a component of bacterial peptidoglycan, muramyl dipeptide (MDP), NOD2 signaling leads to the activation of the NF-κB (nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells) family of transcription factors.23,24 In addition to the established association signal at NOD2, the associated region on chromosome 16 also contained the BRD7 (bromodomain containing 7) gene, which has demonstrated genome-wide significant association at rs9922362 (P-value = 3.26 × 10−16) in a GWAS dataset, separate from the one used in the haplotype analysis, comprising 907 Ashkenazi CD and 2345 Ashkenazi controls (Figure 2).25 BRD7 lies within 350Kb of NOD2 and encodes a protein involved in chromatin remodeling.26 Notably, the GWAS dataset did not show any evidence for independent association in CYLD (cylindromatosis), which is immediately adjacent to NOD2, as has previously been reported.27

Figure 2.

Single-marker associations in the chromosome 16 haplotype region. We observed genome-wide significant associations at rs2076756 (P-value = 2.32 × 10−20) in NOD2 and rs9922362 (P-value = 3.26 × 10−16) in BRD7. Positions of two nominally associated Ashkenazi Jewish haplotypes are shown by black bars at top.

Chromosomes 2 and 21 haplotypes

Like the chromosome 16 region, the haplotype on chromosome 21, chr21_hap8015 (chr21: 44.47 – 44.65 Mb) also spans multiple immune-diseases related genes, such as ICOSLG (inducible T-cell co-stimulator ligand) and AIRE (autoimmune regulator). The chromosome 2 haplotype, chr2_hap10940 (chr2: 61.18 – 61.87 Mb), which had a higher frequency in controls compared to cases, was within 125Kb of COMMD1 (copper metabolism [Murr1] domain containing 1), a regulator of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Exome sequencing

To further explore the haplotype regions of interest, we performed exome sequencing on 55 Ashkenazi Jewish samples, including 50 Crohn’s disease cases and 5 healthy controls. The samples’ Jewish ancestry was validated genetically using GWAS data, and the case samples included two carriers each of the risk haplotypes on chromosomes 16 and 21. Within the associated haplotype regions chromosomes 16 and 21, we identified 40 previously unreported missense or nonsense polymorphisms among all 55 Ashkenazi Jewish individuals sequenced (Supplementary Table 3). None of the coding variants identified in the chromosome 2 haplotype were predicted by Polyphen-2 to be probably damaging in function, and no further investigation of these SNPs was conducted.28

Chromosome 21 haplotype

We identified a number of previously unreported missense or nonsense uncommon mutations within the TRPM2 (transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 2) gene, including three polymorphisms, Arg755Cys, Gln953Stop and Thr1347Met, predicted by PolyPhen-2 to be probably damaging in function. Genotyping of these three SNPs was performed using Taqman assays on a follow-up Ashkenazi cohort of 1220 cases and 1167 healthy controls (Supplementary Table 1). Table 2 summarizes the association evidence for the three TRPM2 variants. We observed nominal evidence for association (P-value = 0.0015) for the most common of these variants, Arg755Cys in the Ashkenazi Jewish Crohn’s disease cohort. At this SNP, in a comparably-sized non-Jewish cohort (915 non-Jewish European ancestry Crohn’s disease cases, and 818 matched healthy controls), we observed no evidence for association (P-value = 0.725). In contrast to Arg755Cys, we observed no evidence for association in the Jewish cohort for either Gln953stop or Thr1347Met in TRPM2. Of interest, the Gln953stop variant is carried by an individual carrying the chromosome 21 risk haplotype (Table 1) and is specific to the Ashkenazi Jewish population, not being observed in a subset of the non-Jewish European ancestry samples comprising 192 Crohn’s disease cases and 192 healthy controls. Additional studies with larger cohorts will be required to definitively determine a role for TRPM2 in Ashkenazi Jewish Crohn’s disease.

Table 2.

Single nucleotide polymorphism association and logistic regression analysis in Ashkenazi Jewish samples

| SNP | Position1 | Gene | Alleles | MAF_Case (N =1167) |

MAF_Ctrl (N =1220) |

P-value | P-value with model selection2 |

P-value, full model3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr16 (16q12.1)-HEATR 3, BRD7, and NOD2 | ||||||||

| HEATR3_R642S | 48 696 354 | HEATR3 | C/A | 0.032 | 0.010 | 3.53 × 10−07 | 0.33 | |

| BRD7_rs9922362 | 48 913 242 | BRD7 | G/A | 0.39 | 0.32 | 2.36 × 10−07 | 0.0292 | 0.041 |

| NOD2_R702W | 49 303 427 | NOD2 | C/T | 0.040 | 0.022 | 5.00 × 10−04 | 5.55 × 10−05 | 5.27 × 10−05 |

| NOD2_N852S | 49 311 345 | NOD2 | A/G | 0.024 | 0.012 | 0.00140 | 0.0027 | 0.0028 |

| NOD2_G908R | 49 314 041 | NOD2 | G/C | 0.10 | 0.040 | 1.93 × 10−17 | 1.66 × 10−13 | 3.57 × 10−10 |

| NOD2_L1007fsinsC | 49 321 279 | NOD2 | G/C | 0.087 | 0.028 | 1.65 × 10−18 | 3.10 × 10−8 | 3.90 × 10−08 |

| Chr21(21q22.3) - TRPM2 | ||||||||

| TRPM2_R755C | 44 644 624 | TRPM2 | C/T | 0.043 | 0.026 | 0.0015 | ||

| TRPM2_Q953X | 44 650 971 | TRPM2 | C/T | 0.0080 | 0.0080 | 0.76 | ||

| TRPM2_T1347M | 44 679 507 | TRPM2 | C/T | 0.030 | 0.025 | 0.40 | ||

Chromosom al coordinates in hg 18.

Logistic regression model with minimum AIC, comprising all four NOD2 variants and rs9922362 in BRD7.

Full logistic regression model comprising all six variants on chromosome 16.

Chromosome 16 haplotypes

Within the region encompassing the chromosome 16 risk haplotypes (Table 1), we identified 21 missense or nonsense mutations among the 55 individuals undergoing exome sequencing (Supplementary Table 3). While most of the carriers of the chromosome 16 risk haplotypes also carry the NOD2 Gly908Arg variant, the converse is not true; in the initial GWAS cohort, only 15 of the 68 Gly908Arg carriers (22%) also carried the extended chromosome 16 risk haplotypes. We then asked whether carriers of the extended risk haplotype might carry additional risk alleles. Importantly, two extended chromosome 16 risk haplotype carriers also carried a previously unidentified missense mutation, Arg642Ser, in HEATR3. The HEATR3 gene encodes a 680 amino acid protein, and the Arg642Ser polymorphism is highly conserved between species and predicted to be probably damaging to gene function by PolyPhen-2.

Fine mapping of chromosome 16 haplotypes

To more precisely define the nature of the various association signals in the NOD2 haplotype, we performed single-point and logistic regression analyses on the region’s key markers in the 1167 Ashkenazi cases and 1220 Ashkenazi controls described above (Table 2). Consistent with prior reports, the Gly908Arg variant is the most common NOD2 risk allele (10.4% minor allele frequency in cases) in the Ashkenazi Jewish cohort; this is in contrast to non-Jewish European ancestry Crohn’s disease cohorts, where the frameshift mutation, Leu1007fsinsC, is the most common.19,29 The Arg642Ser variant in HEATR3 (3.2% minor allele frequency in cases) is highly associated with Crohn’s disease (P-value = 3.53 × 10−7). We genotyped the Arg642Ser variant using Sanger sequencing in 384 non-Jewish European ancestry Crohn’s disease cases and identified no carriers, indicating an Ashkenazi Jewish predominance for this novel variant. Because the HEATR3 Arg642Ser variant is present in Ashkenazi Jews on an extended risk haplotype also containing the more common NOD2 Gly908Arg allele (D’ between Arg642Ser in HEATR3 and Gly908Arg in NOD2 = 0.828), we next performed conditional logistic regression analysis to test for additional conditionally dependent relationships. Several models were compared using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to determine the best subset of SNPs. Additive, dominant and factor coding for the SNP genotypes were examined during the modeling stage. The final model with minimum AIC contained the associated marker in BRD7, rs9922362, as well as all four SNPs in NOD2, but not Arg642Ser in HEATR3. Under this regression model, Gly908Arg in NOD2 demonstrated the most significant evidence for association (P-value = 1.66 × 10−13). Additionally, in a full model containing all six variants across the three genes, a conditional relationship to NOD2 accounted for much of the association evidence observed at HEATR3 Arg642Ser variant (P-value = 0.333).

HEATR3 knockdown and over-expression

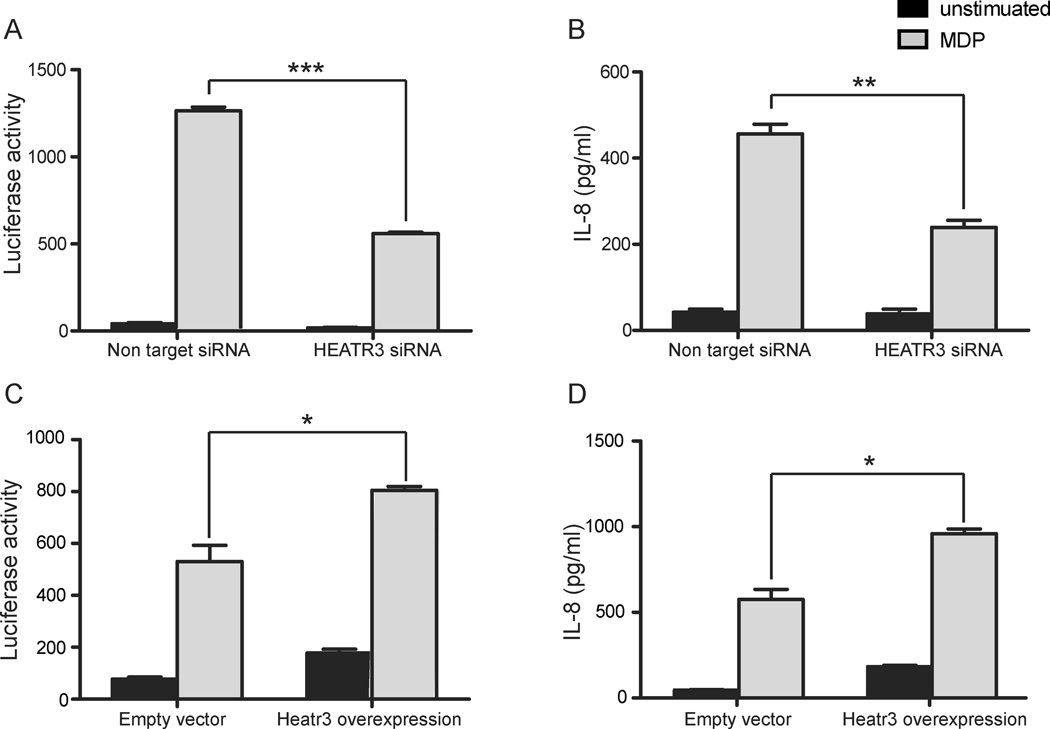

Although the genetic association signal at Arg642Ser in HEATR3 on chromosome 16 did not appear to be independent, we noted that this gene is highly expressed in innate immune cells,30 and we thus investigated its function in regulating NOD2 signaling. To test this, we transiently knocked down HEATR3 using siRNA in cells stably expressing NOD2 and stimulated them with muramyl dipeptide in order to activate NOD2 signaling. We monitored NOD2-dependent signaling using both NF-κB activation, as measured by a luciferase reporter assay (Promega, Madison, WI), and IL-8 secretion, as measured by ELISA assay. Cells transfected with siRNA targeting HEATR3 showed no significant loss in cell viability but resulted in reduced MDP-induced NF-κB activation and greater than 50% reduction in IL-8 secretion compared to non-targeting siRNA controls. These results suggest that HEATR3 is a positive regulator of NOD2 signaling. To further establish this relationship, we also over-expressed HEATR3 in HEK293 cells stable expressing NOD2. Cells over-expressing HEATR3 exhibited increased luciferase activity and increased IL-8 secretion, thereby establishing a role for HEATR3 in positively regulating NOD2 signaling (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

HEATR3 is a positive component of the NOD2 signaling pathway. siRNA mediated knock down of HEATR3 diminished NOD2-dependent NF-κB induction (A) and IL-8 secretion (B) relative to non-targeting siRNA controls. Furthermore, over-expression of HEATR3 increased NF-κB signaling (C) and IL-8 production (D). Cells were left unstimulated (black bars) or stimulated overnight with 20 ng/mL of MDP (grey bars). Together these results support a positive role for HEATR3 in NOD2 signaling. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

Discussion

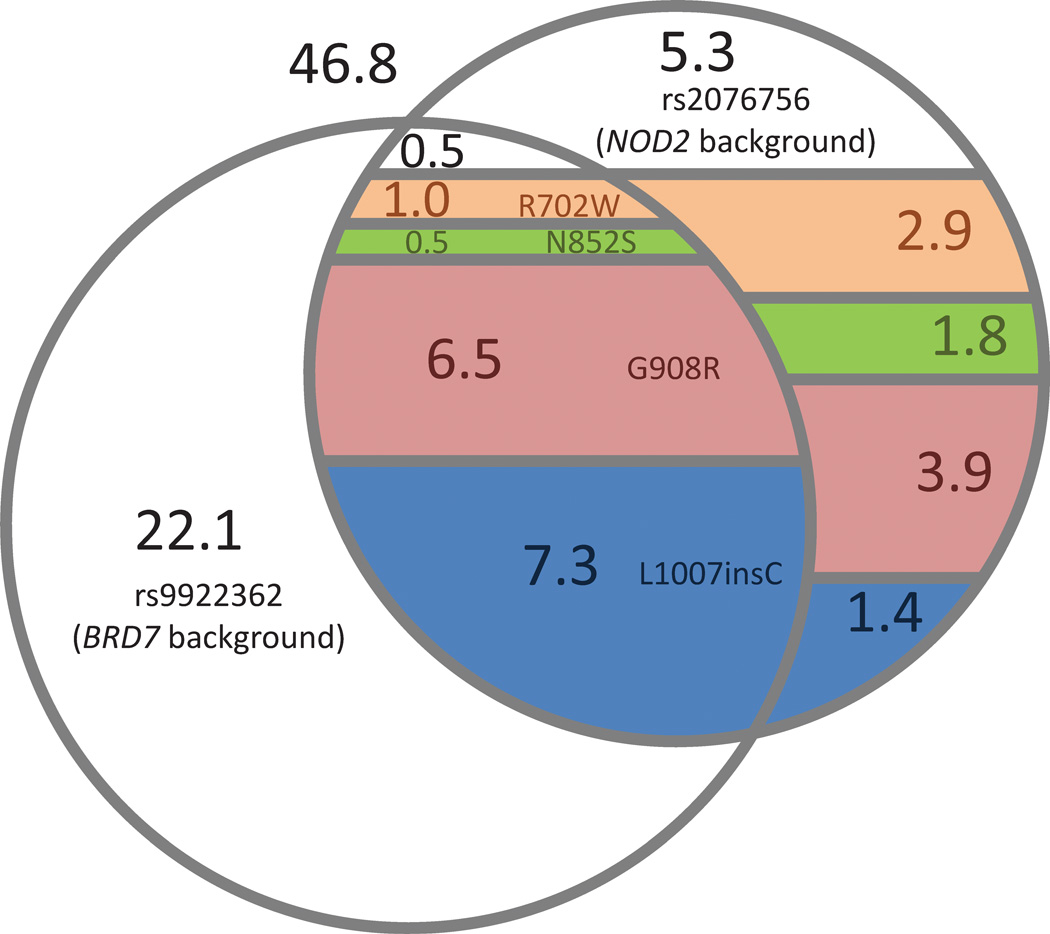

The chromosome 16 associations at BRD7 and NOD2 represent an empirical paradigm of synthetic association that illustrates and extends the proposals of Dickson, et al.10 Using computer simulation, the researchers demonstrated that a cluster of low frequency, highly penetrant mutations often occurs stochastically more frequently with one allele than the other at a common SNP, resulting in “synthetic” association signals at these common variants. While it has been argued that synthetic associations are not common in general, the interactions between and within BRD7 and NOD2 provide an important illustration of the complexities inherent in regression analyses to identify independent alleles. The minor allele (minor allele frequency 25.5% in healthy controls) at the common NOD2 polymorphism rs2076756 tags a shared haplotype on which four independent, causal, and uncommon NOD2 variants (Arg702Trp, Asn852Ser, Gly908Arg, Leu1007fsinsC) completely reside. This has been widely acknowledged as an example of synthetic association, as the NOD2 GWAS signal is created by this cluster of rare variants with high effect, and the signal is mappable using linkage, which was originally predicted by Dickson et al.10,31

In our analysis, common variants at BRD7 (rs9922362) and NOD2 (rs2076756) appeared to confer independent evidence for association, with P-values = 1.42 × 10−13 and 3.25 × 10−13, respectively, in a logistic regression model consisting of the two SNPs. After conditioning the BRD7 SNP on four uncommon causal NOD2 variants, however, the BRD7 association signal largely diminishes (conditional P-value = 0.0292). Taken together, these statistical results imply that the BRD7 SNP functions as a partial background for the directly causal NOD2 mutations, but not for the entire NOD2 IBD-associated haplotype. This is visualized more directly in Figure 4, which shows that the BRD7 SNP indeed does not appear to simply be associated through linkage disequilibrium with the NOD2 background SNP, but rather that its carriers are enriched for the rare causal variants within the NOD2 background haplotype. Importantly, the 0.4 Mb distance between the BRD7 variant and NOD2 is consistent with the findings by Dickson, et al. which showed that causal relationships can extend over long regions surrounding synthetic association, in the range of several megabases. However, we note that the absence of conditional dependence between the two common background SNPs in BRD7 and NOD2 conflicts with the hierarchical genealogy model supported by Dickson, et al. Overall, the example of Crohn’s disease illustrates the variability of conditioning on highly associated, non-causal background variants such as the NOD2 common haplotype background variant, rs2076756, as opposed to functional uncommon variants.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram of carriers for chromosome 16 haplotype variants among healthy controls. Numbers indicate the percentage of haploid chromosomes (n = 2440) that carry each combination of mutations. Colors indicate causal mutations within NOD2: peach = R702W; green = N852S; pink = G908R; blue = L1007insC. Missing genotypes and phasing of haploid carriers were inferred using BEAGLE with default parameters. Regions representing less than 0.5% of haploid carriers are not shown. These results indicate that both the common BRD7 and NOD2 SNPs serve as backgrounds for the NOD2 uncommon causal variants, which in turn serve as the basis for association at the these two common background variants.

In this study, we report associations of uncommon extended haplotypes in Ashkenazi Jewish, but not non-Jewish European ancestry populations, thereby illustrating the greater power of this approach in endogamous populations. The haplotype associations on chromosome 16 tag the Gly908Arg variant within NOD2, the most prevalent causal mutation in Ashkenazi Jewish populations. The extended haplotype carriers in this region tag a less common, Ashkenazi Jewish-specific variant, Arg642Ser in HEATR3, which we demonstrated to function in the NOD2 pathway. Given the extensive linkage disequilibrium between Gly908Arg in NOD2 and Arg642Ser in HEATR3, however, we did not observe independent evidence for association for the HEATR3 SNP. This marker, along with others in TRPM2 on chromosome 21, demonstrated the capability of our haplotype-based analysis to direct the discovery of new disease-associated and population-specific polymorphisms. Furthermore, the extended length of the Jewish-specific haplotypes may indicate the presence of long-distance conditional relationships, as in the case of rs9922362 of BRD7 and the NOD2 causal variants on chromosome 16, an example of synthetic association. As additional fine-mapping studies of GWAS loci are reported, an increasing number of population-specific polymorphisms and haplotypes will be identified. The etiology for the higher prevalence of Crohn’s disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish population remains largely undefined; however, our study indicates that extended haplotypes containing multiple functional polymorphisms inherited in cis may contribute in a population-specific manner.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Three hundred and ninety-seven Ashkenazi Crohn’s disease cases and 431 controls, and 547 non-Ashkenazi Crohn’s disease cases and 549 controls (Supplementary Table 1) were ascertained through Genetics Research Centers in Baltimore, Chicago, Montreal, Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, and Toronto, and through the New York Health Project. In all cases, informed consent was obtained following protocols approved by each local institutional review board. Diagnostic inclusion and exclusion criteria are described elsewhere.13 Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry was validated using principal components analysis.

Genotyping and haplotype association analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood from the case-control cohort. Genotyping was performed on the Illumina HumanHap300 platform, with an average inter-marker distance less than 10Kb. All samples had genotype yields greater than 94%, and missing genotypes were imputed using BEAGLE 3.1.0 with default parameters.32 Analysis was performed using GERMLINE 1.5.0 (Genetic Error-tolerant Regional Matching with LINear-time Extension), a computationally efficient program for identifying shared identical-by-descent segments between pairs of individuals in a large population, and DASH 1.1.0 (DASH Associates Shared Haplotypes), a program for clustering these segments into haplotype regions that are shared by multiple individuals.33,34 Our analysis utilized default parameters, with a minimum haplotype length of 3 Mb and a maximum of 4 homozygous mismatches between shared segments. In the Ashkenazi samples, 473,621 haplotype clusters across the autosomes were tested for association, compared to 8,986 clusters in the non-Jewish samples. Due to correlation between the haplotype clusters, precise multiple testing corrections could not be calculated, but given that all clusters in the Jewish and non-Jewish analyses had P-values greater than 10−5 and 10−3, respectively, it was clear that none were genome-wide significant.

Exome sequencing and variant screening

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood and whole-exome captured with the NimbleGen 2.1 M human exome array following the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche/NimbleGen, Madison, WI). Captured libraries were sequenced on the Illumina genome analyzer as paired-end 75-bp reads, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequence reads were mapped to the reference genome (hg18) using the BWA program using default parameters.35 The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) v2 was used to call alleles at variant sites.36 Sample-level realignment and multi-sample SNP calling were performed using default parameters and the GATKStandard variant filter.

HEATR3 knockdown and over-expression

HEK293 cells stably expressing NOD2 were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 1x penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). All experiments were performed in duplicate. In the silencing experiments, these cells were then reverse-transfected with siGENOME siRNA pools (Thermo Scientific, Hudson, NH) targeting HEATR3 (or non-targeting siRNA as a negative control) at a concentration of 20 nM with the lipid transfection agent Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) diluted in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) for 48 hours. Cells were either left unstimulated or subsequently stimulated with MDP (20 ng/ml; Bachem, Torrance, CA) for 18 hours. In the over-expression experiment, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 with a pCMV-SPORT6 based expression plasmid encoding murine HEATR3 (Thermo Scientific), followed by MDP stimulation as described above. Transfection with the empty vector was used as a negative control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [NIDDK U01 DK062429 to J.H.C., U01 DK062422 to J.H.C., RC1 DK086800 to J.H.C., KL2RR024138, NIGMS T32 GM007205 to K.Y.H., R01 DK77905 to C.A.]; the New York Crohn’s Disease Foundation [L.M., R.J.D., I.P.]; and to the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America [J.H.C.].

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J of Med. 2009;361:2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cezard JP, Belaiche J, et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Economou M, Trikalinos TA, Loizou KT, Tsianos EV, Ioannidis JP. Differential effects of NOD2 variants on Crohn's disease risk and phenotype in diverse populations: a metaanalysis. Am J Gastroenterology. 2004;99:2393–2404. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–124. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayberry JF, Judd D, Smart H, Rhodes J, Calcraft B, Morris JS. Crohn's disease in Jewish people--an epidemiological study in south-east Wales. Digestion. 1986;35:237–240. doi: 10.1159/000199374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein CN, Rawsthorne P, Cheang M, Blanchard JF. A population-based case control study of potential risk factors for IBD. Am J Gastroenterology. 2006;101:993–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostrer H. A genetic profile of contemporary Jewish populations. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:891–898. doi: 10.1038/35098506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atzmon G, Hao L, Pe'er I, Velez C, Pearlman A, Palamara PF, et al. Abraham's children in the genome era: major Jewish diaspora populations comprise distinct genetic clusters with shared Middle Eastern Ancestry. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bray SM, Mulle JG, Dodd AF, Pulver AE, Wooding S, Warren ST. Signatures of founder effects, admixture, and selection in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Proc Natl Aca Sci USA. 2010;107:16222–16227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004381107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickson SP, Wang K, Krantz I, Hakonarson H, Goldstein DB. Rare variants create synthetic genome-wide associations. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang J, Kugathasan S, Georges M, Zhao H, Cho JH. Improved risk prediction for Crohn's disease with a multi-locus approach. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2435–2442. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Daly MJ, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314:1461–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.1135245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD, Silverberg MS, Goyette P, Huett A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:596–604. doi: 10.1038/ng2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franke A, McGovern DP, Barrett JC, Wang K, Radford-Smith GL, Ahmad T, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1118–1125. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karban A, Atia O, Leitersdorf E, Shahbari A, Sbeit W, Ackerman Z, et al. The relation between NOD2/CARD15 mutations and the prevalence and phenotypic heterogeneity of Crohn's disease: lessons from the Israeli Arab Crohn's disease cohort. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1692–1697. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2917-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peter I, Mitchell AA, Ozelius L, Erazo M, Hu J, Doheny D, et al. Evaluation of 22 genetic variants with Crohn's disease risk in the Ashkenazi Jewish population: a case-control study. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman B, Silverberg MS, Gu X, Zhang Q, Lazaro A, Steinhart AH, et al. CARD15 and HLA DRB1 alleles influence susceptibility and disease localization in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterology. 2004;99:306–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugimura K, Taylor KD, Lin YC, Hang T, Wang D, Tang YM, et al. A novel NOD2/CARD15 haplotype conferring risk for Crohn disease in Ashkenazi Jews. Am J Hum Gen. 2003;72(3):509–518. doi: 10.1086/367848. Epub 2003/02/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tukel T, Shalata A, Present D, Rachmilewitz D, Mayer L, Grant D, et al. Crohn disease: frequency and nature of CARD15 mutations in Ashkenazi and Sephardi/Oriental Jewish families. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:623–636. doi: 10.1086/382226. E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonen DK, Ogura Y, Nicolae DL, Inohara N, Saab L, Tanabe T, et al. Crohn's disease-associated NOD2 variants share a signaling defect in response to lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:140–146. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Z, Lin XY, Akolkar PN, Gulwani-Akolkar B, Levine J, Katz S, et al. Variation at NOD2/CARD15 in familial and sporadic cases of Crohn's disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Am J Gastroenterology. 2002;97:3095–3101. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A, Gutierrez O, Pons F, Crespo J, et al. Host recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide mediated through NOD2. Implications for Crohn's disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5509–5512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, Chamaillard M, Labigne A, Thomas G, et al. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8869–8872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenny EE, Pe'er I, Karban A, Ozelius L, Mitchell AA, Ng SM, et al. A genome-wide scan of Ashkenazi Jewish Crohn's disease suggests novel susceptibility loci. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drost J, Mantovani F, Tocco F, Elkon R, Comel A, Holstege H, et al. BRD7 is a candidate tumour suppressor gene required for p53 function. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:380–389. doi: 10.1038/ncb2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elding H, Lau W, Swallow DM, Maniatis N. Dissecting the genetics of complex inheritance: linkage disequilibrium mapping provides insight into Crohn disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brant SR, Wang MH, Rawsthorne P, Sargent M, Datta LW, Nouvet F, et al. A population-based case-control study of CARD15 and other risk factors in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterology. 2007;102:313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maouche S, Poirier O, Godefroy T, Olaso R, Gut I, Collet JP, et al. Performance comparison of two microarray platforms to assess differential gene expression in human monocyte and macrophage cells. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson CA, Soranzo N, Zeggini E, Barrett JC. Synthetic associations are unlikely to account for many common disease genome-wide association signals. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Browning SR, Browning BL. Rapid and accurate haplotype phasing and missing-data inference for whole-genome association studies by use of localized haplotype clustering. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1084–1097. doi: 10.1086/521987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gusev A, Kenny EE, Lowe JK, Salit J, Saxena R, Kathiresan S, et al. DASH: a method for identical-by-descent haplotype mapping uncovers association with recent variation. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:706–717. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gusev A, Lowe JK, Stoffel M, Daly MJ, Altshuler D, Breslow JL, et al. Whole population, genome-wide mapping of hidden relatedness. Genome Res. 2009;19:318–326. doi: 10.1101/gr.081398.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.