Abstract

The visual system’s flexibility in estimating depth is remarkable: we readily perceive three-dimensional (3D) structure under diverse conditions from the seemingly random dots of a ‘magic eye’ stereogram to the aesthetically beautiful, but obviously flat, canvasses of the Old Masters. Yet, 3D perception is often enhanced when different cues specify the same depth. This perceptual process is understood as Bayesian inference that improves sensory estimates. Despite considerable behavioral support for this theory, insights into the cortical circuits involved are limited. Moreover, extant work tested quantitatively similar cues, reducing some of the challenges associated with integrating computationally and qualitatively different signals. Here we address this challenge by measuring functional MRI responses to depth structures defined by shading, binocular disparity and their combination. We quantified information about depth configurations (convex ‘bumps’ vs. concave ‘dimples’) in different visual cortical areas using pattern-classification analysis. We found that fMRI responses in dorsal visual area V3B/KO were more discriminable when disparity and shading concurrently signaled depth, in line with the predictions of cue integration. Importantly, by relating fMRI and psychophysical tests of integration, we observed a close association between depth judgments and activity in this area. Finally, using a cross-cue transfer test, we found that fMRI responses evoked by one cue afford classification of responses evoked by the other. This reveals a generalized depth representation in dorsal visual cortex that combines qualitatively different information in line with 3D perception.

Introduction

Many everyday tasks rely on depth estimates provided by the visual system. To facilitate these outputs, the brain exploits a range of inputs: from cues related to distance in a mathematically simple way (e.g., binocular disparity, motion parallax) to those requiring complex assumptions and prior knowledge (e.g. shading, occlusion) (Mamassian and Goutcher, 2001; Kersten et al., 2004; Burge et al., 2010). These diverse signals each evoke an impression of depth in their own right; however, the brain aggregates cues (Dosher et al., 1986; Buelthoff and Mallot, 1988; Landy et al., 1995) to improve perceptual judgments (Knill and Saunders, 2003).

Here we probe the neural basis of integration, testing binocular disparity and shading depth cues that are computationally quite different. At first-glance these cues may appear so divergent that their combination would be prohibitively difficult. However, perceptual judgments show evidence for the combination of disparity and shading (Buelthoff and Mallot, 1988; Doorschot et al., 2001; Vuong et al., 2006; Lee and Saunders, 2011; Schiller et al., 2011; Lovell et al., 2012), and the solution to this challenge is conceptually understood as a two stage process (Landy et al., 1995) in which cues are first analyzed quasi-independently followed by the integration of cue information that has been ‘promoted’ into common units (such as distance). Moreover, observers can make reliable comparisons between the perceived depth from shading and stereoscopic, as well as haptic, comparison stimuli (Kingdom, 2003; Schofield et al., 2010), suggesting some form of comparable information.

To gain insight into the neural circuits involved in processing three-dimensional information from disparity and shading, previous brain imaging studies have tested for overlapping fMRI responses to depth structures defined by the two cues, yielding locations in which information from disparity and shading converge (Sereno et al., 2002; Georgieva et al., 2008; Nelissen et al., 2009). While this is a useful first step, this previous work has not established integration: for instance, representations of the two cues might be collocated within the same cortical area, but represented independently. By contrast, recent work testing the integration of disparity and motion depth cues, indicates that integration occurs in higher dorsal visual cortex (area V3B/Kinetic Occipital (KO)) (Ban et al., 2012). This suggests a candidate cortical locus in which other types of 3D information may be integrated; however, it is not clear whether integration would generalize to (i) more complex depth structures and/or (ii) different cue pairings.

First, Ban and colleagues (2012) used simple fronto-parallel planes that can sub-optimally stimulate neurons selective to disparity-defined structures in higher portions of the ventral (Janssen et al., 2000) and dorsal streams (Srivastava et al., 2009) compared with more complex curved stimuli. It is therefore possible that other cortical areas (especially those in the ventral stream) would emerge as important for cue integration if more ‘shape-like’ stimuli were presented. Second, it is possible that information from disparity and motion are a special case of cue conjunctions, and thus integration effects may not generalize to other depth signal combinations. In particular, depth from disparity and from motion have computational similarities (Richards, 1985), joint neuronal encoding (Bradley et al., 1995; Anzai et al., 2001; DeAngelis and Uka, 2003) and can, in principle, support metric (absolute) judgments of depth. In contrast, the 3D pictorial information provided by shading relies on a quite different generative process that is subject to different constraints and prior assumptions (Horn, 1975; Sun and Perona, 1998; Mamassian and Goutcher, 2001; Koenderink and van Doorn, 2002; Fleming et al., 2003; Thompson et al., 2011).

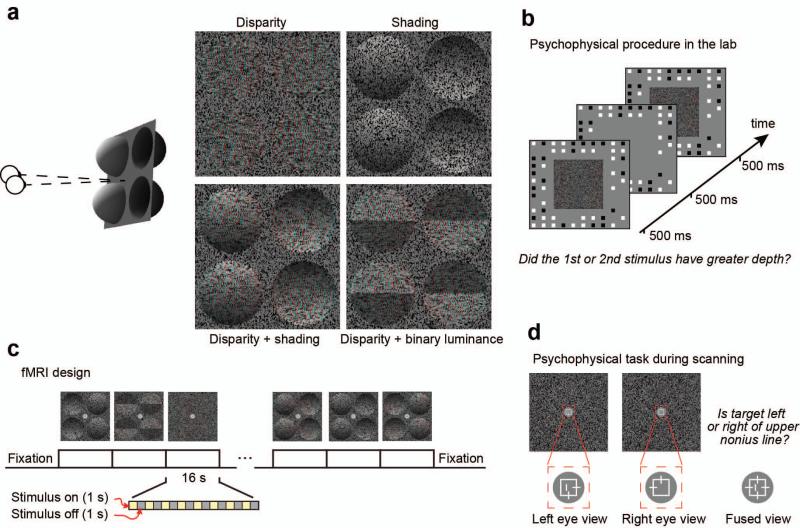

To test for cortical responses related to the integration of disparity and shading, we assessed how fMRI responses change when stimuli are defined by different cues (Fig 1a). We used multi-voxel pattern analysis (MVPA) to assess the information contained in fMRI responses evoked by stimuli depicting different depth configurations (convex vs. concave hemispheres to the left vs. right of the fixation point). We were particularly interested in how information about the stimulus contained in the fMRI signals changed depending on the cues used to depict depth in the display. Intuitively, we would expect that discriminating fMRI responses should be easier when differences in the depicted depth configuration were defined by two cues rather than just one (i.e., differences defined by disparity and shading together should be easier to discriminate than differences defined by only disparity). The theoretical basis for this intuition can be demonstrated based on statistically optimal discrimination (Ban et al., 2012), with the extent of the improvement in the two-cue case providing insight into whether the underlying computations depend on the integration of two cues or rather having co-located but independent depth signals.

Figure 1.

Stimulus illustration and experimental procedures. (a) Left side: Cartoon of the disparity and/or shading defined depth structure. One of the two configurations is presented: bumps to the left, dimples to the right. Right side: stimulus examples rendered as red-cyan anaglyphs. (b) Illustration of the psychophysical testing procedure. (c) Illustration of the fMRI block design. (d) Illustration of the vernier task performed by participants during the fMRI experiment. Participants compared the horizontal position of a vertical line flashed (250 ms) to one eye against the upper vertical nonius element of the crosshair presented to the other eye.

To appreciate the theoretical predictions for a cortical area that responds to integrated cues vs. co-located but independent signals, first consider a hypothetical area that is only sensitive to a single cue (e.g., shading). If shading information differed between two presented stimuli, we would expect neuronal responses to change, providing a signal that could be decoded. By contrast, manipulating a non-encoded stimulus feature (e.g., disparity) would have no effect on neuronal responses, meaning that our ability to decode the stimulus from the fMRI response would be unaffected. Such a computationally isolated processing module is biologically rather unlikely, so next we consider a more plausible scenario where an area contains different subpopulations of neurons, some of which are sensitive to disparity and others to shading. In this case, we would expect to be able to decode stimulus differences based on changes in either cue. Moreover, if the stimuli contained differences defined by both cues, we would expect decoding performance to improve, where this improvement is predicted by the quadratic sum of the discriminabilities for changes in each cue. This expectation can be understood graphically by conceiving of discriminability based on shading and disparity cues as two sides of a right-angled triangle, where better discriminability equates to longer side lengths; the discriminability of both cues together equals the triangle’s hypotenuse whose length is determined based on a quadratic sum (i.e., the Pythagorean equation) and is always at least as good as the discriminability of one of the cues.

The alternative possibility is a cortical region that integrates the depth cues. Under this scenario, we also expect better discrimination performance when two cues define differences between the stimuli. Importantly however, unlike the independence scenario, when stimulus differences are defined by only one cue, a fusion mechanism is adversely affected. For instance, if contrasting stimulus configurations differ in the depth indicated by shading but disparity indicates no difference, the fusion mechanism combines the signals from each cue with the result that it is less sensitive to the combined estimate than the shading component alone. By consequence, if we calculate a quadratic summation prediction based on MVPA performance for depth differences defined by single cues (i.e., disparity; shading) we will find that empirical performance in the combined cue case (i.e., disparity + shading) exceeds the prediction (Ban et al., 2012). Here we exploit this expectation to identify cortical responses to integrated depth signals, seeking to identify discrimination performance that is ‘greater than the sum of its parts’ due to the detrimental effects of presenting stimuli in which depth differences are defined in terms of a single cue.

To this end, we generated random dot patterns (Fig. 1a) that evoked an impression of four hemispheres, two concave (‘dimples’) and two convex (‘bumps’). We formulated two different types of display that differed in their configuration: (1) bumps left – dimples right (depicted in Fig. 1a) vs. (2) dimples left – bumps right. We depicted depth variations from: (i) binocular disparity, (ii) shading gradients, and (iii) the combination of disparity and shading. In addition, we employed a control stimulus (iv) in which the overall luminance of the top and bottom portions of each hemisphere differed (Ramachandran, 1988) (disparity + binary luminance). Perceived depth for these (deliberately) crude approximations of the shading gradients relied on disparity. We tested for integration using both psychophysical- and fMRI- discrimination performance for the component cues (i, ii) with that for stimuli containing two cues (iii, iv). We reasoned that a response based on integrating cues would be specific to concurrent cue stimulus (iii) and not be observed for the control stimulus (iv).

Methods

Participants

Twenty observers from the University of Birmingham participated in the fMRI experiments. Of these, five were excluded due to excessive head movement during scanning, meaning that the correspondence between voxels required by the MVPA technique was lost. Excessive movement was defined as ≥ 4mm over an eight minute run, and we excluded participants if they had fewer than 5 runs below this cut-off as there was insufficient data for the MVPA. Generally, participants were able to keep still: the average absolute maximum head deviation relative to the start of the first run for included participants was 1.2 mm vs. 4.5 mm for excluded participants. Moreover only one included participant had an average head motion of > 2 mm per run, and the mode of the head movement distribution across subjects was <1 mm. Six female and nine male participants were included; twelve were right-handed. Mean age was 26 ± 1.2 (S.E.M.) years. Authors AEW and HB participated, all other subjects were naïve to the purpose of the study. Four of the participants had taken part in Ban et al.’s (2012) study. Participants had normal or corrected to normal vision and were prescreened for stereo deficits. Experiments were approved by the University of Birmingham Science and Engineering ethics committee; observers gave written informed consent.

Stimuli

Stimuli were random dot stereograms (RDS) that depicted concave or convex hemispheres (radius = 1.7°; depth amplitude 1.85 cm ≈ 15.7 arcmin) defined by disparity and/or shading (Fig. 1a). We used small dots (diameter = 0.06°) and patterns with a high density (94 dots/deg2) to enhance the impression of shape-from-shading. We used the Blinn-Phong shading algorithm implemented in Matlab with both an ambient and a directional light. The directional light source was positioned above the observer at an elevation of 45° with respect to the center of the stimulus, and light was simulated as arriving from optical infinity. The ambient light, and illumination from infinity meant that for our stimuli there were no cast shadows. The stimulus was modeled as having a Lambertian surface. For the disparity condition, dots in the display had the same luminance histogram as the shaded patterns; however, their positions (with respect to the original shading gradient) were spatially randomized, breaking the shading pattern. For the shading condition, disparity specified a flat surface. To create the binary luminance stimuli, the luminance of the top and bottom portions of the hemispheres was held constant at the mean luminance of these portions of the shapes for the shaded stimuli. Four hemispheres were presented: two convex, and two concave, located either side of a fixation marker. Two types of configuration were used: (i) convex on the left, concave on the right and (ii) vice versa. The random dot pattern subtended 8×8° and was surrounded by a larger, peripheral grid (18×14°) of a black and white squares which served to provide a stable background reference. Other parts of the display were mid-grey.

Psychophysics

Stimuli were presented in a lab setting using a stereo set-up in which the two eyes viewed separate displays (ViewSonic FB2100×) through front-silvered mirrors at a distance of 50cm. Linearization of the graphics card grey level outputs was achieved using photometric measurements. The screen resolution was 1600 × 1200 pixels at 100Hz.

Under a two interval forced choice design, participants decided which stimulus had the greater depth profile (Fig 1b). On every trial, one interval contained a standard disparity-defined stimulus (± 1.85 cm / 15.7 arcmin), the other interval contained a stimulus from one of three conditions (disparity alone; disparity + shading; disparity + binary luminance) and had a depth amplitude that was varied using the method of constant stimuli. The shading cue varied as the depth amplitude of the shape was manipulated such that the luminance gradient was compatible with a bump/dimple whose amplitude matched that specified by disparity. Similarly, for the binary luminance case, the stimulus luminance values changed at different depth amplitudes to match the luminance variations that occurred for the gradient shaded stimuli. The order of the intervals was randomized, and conditions were randomly interleaved. On a given trial, a random jitter was applied to the depth profile of both intervals (uniform distribution within ±1 arcmin to reduce the potential for adaptation to a single disparity value across trials). Participants judged “did the first or second stimulus have greater depth” by pressing an appropriate button. On some runs participants were instructed to consider their judgment relative to the convex portions of the display, in others the concave portions. The spatial configuration of convex and concave items was randomized. A single run contained a minimum of 630 trials (105 trials × 3 conditions × 2 curvature instructions). We made limited measures of the shading alone condition as we found in pilot testing that participants’ judgments based on shading ‘alone’ were very poor (maximum discriminability in the shading condition was d′ = 0.3 ± 0.25) meaning that we could not fit a reliable psychometric function, and participants became frustrated by the seemingly impossible task. Moreover, in the shading alone condition, stimulus changes could be interpreted as a change of light source direction, rather than depth, given the bas-relief ambiguity (Belhumeur et al., 1999). This ambiguity should be removed by the constraint from disparity signals in the disparity + shading condition, although this does not necessarily happen (see Discussion).

Imaging

Data were recorded at the Birmingham University Imaging Centre using a 3 Tesla Philips MRI scanner with an 8-channel multi-phase array head coil. BOLD signals were measured with an echo-planar (EPI) sequence (TE: 35 ms, TR: 2s, 1.5×1.5×2 mm, 28 slices near coronal, covering visual, posterior parietal and posterior temporal cortex) for both experimental and localizer scans. A high-resolution anatomical scan (1 mm3) was also acquired for each participant to reconstruct cortical surface and coregister the functional data. Following coregistration in the native anatomical space, functional and anatomical data were converted into Talairach coordinates.

During the experimental session, four stimulus conditions (disparity; shading; disparity + shading; disparity + binary luminance) were presented in two spatial configurations (convex on left vs. on right) = 8 trial types. Each trial type was presented in a block (16s) and repeated three times during a run (Fig. 1c). Stimulus presentation was 1s on, 1s off, and different random dot stereograms were used for each presentation. These different stimuli had randomly different depth amplitudes (jitter of 1 arcmin) to attenuate adaptation to a particular depth profile across a block. Each run started and ended with a fixation period (16s), total duration = 416s. Scan sessions lasted 90 minutes, allowing collection of 7 to 10 runs depending on the initial setup time and each individual participant’s requirements for breaks between runs.

Participants were instructed to fixate at the centre of the screen, where a square crosshair target (side = 0.5°) was presented at all times (Fig. 1d). This was surrounded by a mid-grey disc area (radius = 1°). A dichoptic Vernier task was used to encourage fixation and provide a subjective measure of eye vergence (Popple et al., 1998). In particular, a small vertical Vernier target was flashed (250 ms) at the vertical center of the fixation marker to one eye. Participants judged whether this Vernier target was to the left or right of the upper nonius line, which was presented to the other eye. We used the method of constant stimuli to vary Vernier target position, and fit the proportion of ‘target on the right responses’ to estimate whether there was any bias in the observers’ responses that would indicate systematic deviation from the desired vergence state. The probability of a Vernier target appearing on a given trial was 50%, and the timing of appearance was variable with respect to trial onset (during the first vs. second half of the stimulus presentation), requiring constant vigilance on behalf of the participants. In a separate session, a subset of participants (n = 3) repeated the experiment during an eye tracking session in the scanner. Eye movement data were collected with CRS limbus Eye tracker (CRS Ltd, Rochester, UK).

The vernier task was deliberately chosen to ensure that participants were engaged in a task orthogonal to the main stimulus presentations and manipulation. The temporal uncertainty in the timing of presentation, and its brief nature, ensured participants had to constantly attend to the fixation marker. Thus differences in fMRI responses between conditions could not be ascribed to attentional state, task difficulty or the degree of conflict inherent in the different stimuli. Note also that in addition to performing different tasks, the stimuli presented during scanning were highly suprathreshold (i.e. convex vs. concave) to ensure reliable decoding of the fMRI responses. This differed from the psychophysical judgments where we measured sensitivity to small differences in the depth profile of the shapes. We would expect benefits from integrating cues in both cases, however it is important to note these differences imposed by the different types of measurement paradigms (fMRI vs. psychophysics) we have used.

Stereoscopic stimulus presentation was achieved using a pair of video projectors (JVC D-ILA SX21), each containing separate spectral comb filters (INFITEC, GmBH) whose projected images were optically combined using a beam-splitter cube before being passed through a wave guide into the scanner room. The INFITEC interference filters produce negligible overlap between the wavelength emission spectra for each projector, meaning that there is little crosstalk between the signals presented on the two projectors for an observer wearing a pair of corresponding filters. Images were projected onto a translucent screen inside the bore of the magnet. Subjects viewed the display via a front-surfaced mirror attached to the headcoil (viewing distance = 65 cm). The two projectors were matched and grey scale linearized using photometric measurements. The INFITEC filters restrict the visibility of the eyes, making standard remote eye tracking equipment unsuitable for eye movement recording in our setup. We therefore employed a monocular limbus eye tracker located between the participants’ eyes and the spectral comb filters.

Functional and anatomical pre-processing of MRI data was conducted with BrainVoyager QX (BrainInnovation B.V.) and in-house MATLAB routines. For each functional run, data were corrected with slice time correction, 3D motion correction, high pass filtering, and linear trend removal. After motion correction, each participant’s functional data were aligned to their anatomical scan and transformed into Talairach space. No spatial smoothing was performed. Retinotopic areas were identified in individual localizer scanning sessions for each participant.

Mapping regions of interest (ROIs)

We identified regions of interest within the visual cortex for each participant in a separate fMRI session prior to the main experiment. To identify retinotopically organized visual areas, we used rotating wedge stimuli and expanding/contracting rings to identify visual field position and eccentricity maps (Sereno et al., 1995; DeYoe et al., 1996). Thereby we identified areas V1, V2 and the dorsal and ventral portions of V3 (which we denote V3d and V3v). Area V4 was localized adjacent to V3v with a quadrant field representation (Tootell and Hadjikhani, 2001) while V3A was adjacent to V3d with a hemi-field representation. Area V7 was identified as anterior and dorsal to V3A with a lower visual field quadrant representation (Tootell et al., 1998; Tyler et al., 2005). The borders of area V3B were identified as based on a hemi-field retinotopic representation inferior to, and sharing a foveal representation with, V3A (Tyler et al., 2005). This retinotopically-defined area overlapped with the contiguous voxel set that responded significantly more (p = 10−4) to intact vs. scrambled motion-defined contours which has previously been described as the kinetic occipital area (KO) (Dupont et al., 1997; Zeki et al., 2003). Given this overlap, we denote this area as V3B/KO (Ban et al., 2012) (see also (Larsson et al., 2010)). Talairach coordinates for this area are provided in Table 1. We identified the human motion complex (hMT+/V5) as the set of voxels in the lateral temporal cortex that responded significantly more (p = 10−4) to coherent motion than static dots (Zeki et al., 1991). Finally, the lateral occipital complex was defined as the voxels in the lateral occipito-temporal cortex that responded significantly more (p = 10−4) to intact vs. scrambled images of objects (Kourtzi and Kanwisher, 2001). The posterior subregion LO extended into the posterior inferiotemporal sulcus and was defined based on functional activations and anatomy (Grill-Spector et al., 2000).

Table 1.

Talairach coordinates of the centroids of the region we denote V3B/KO. We present data for all participants, and participants separated into the good and poor integration groups.

| Left hemisphere | Right hemisphere | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | ||

| V3B/KO (all participants) |

Mean | −27.5 | −84.7 | 7.0 | 31.6 | −80.7 | 6.5 |

| SD | 4.4 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.8 | |

| Good integrators |

Mean | −26.9 | −86.0 | 6.7 | 31.5 | −81.7 | 7.2 |

| SD | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.8 | |

| Poor integrators |

Mean | −28.1 | −83.4 | 7.2 | 31.8 | −79.9 | 5.8 |

| SD | 4.6 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.8 | |

Multi-voxel pattern analysis (MVPA)

To select voxels for the MVPA, we used a participant-by-participant fixed effects GLM across runs on grey matter voxels using the contrast ‘all stimulus conditions vs. the fixation baseline’. In each ROI, we rank ordered the resultant voxels by their t-statistic (where t>0), and selected to the top 300 voxels as data for the classification algorithm (Preston et al., 2008). To minimize baseline differences between runs we z-scored the response timecourse of each voxel and each experimental run. To account for the hemodynamic response lag, the fMRI time series were shifted by 2 TRs (4 s). Thereafter we averaged the fMRI response of each voxel across the 16 s stimulus presentation block, obtaining a single test pattern for the multivariate analysis per block. To remove potential univariate differences (that can be introduced after z-score normalization due to averaging across timepoints in a block, and grouping the data into train vs. test data sets), we normalized by subtracting the mean of all voxels for a given volume (Serences and Boynton, 2007), with the result that each volume had the same mean value across voxels, and differed only in the pattern of activity. We performed multivoxel pattern analysis using a linear support vector machine (SVMlight toolbox) classification algorithm. We trained the algorithm to distinguish between fMRI responses evoked by different stimulus configurations (e.g., convex to the left vs. to the right of fixation) for a given stimulus type (e.g., disparity). Participants typically took part in 8 runs, each of which had 3 repetitions of a given spatial configuration and stimulus type, creating a total of 24 patterns. We used a leave-one-run out cross validation procedure: we trained the classifier using 7 runs (i.e., 21 patterns) and then evaluated the prediction performance of the classifier using the remaining, non-trained data (i.e., 3 patterns). We repeated this, leaving a single run out in turn, and calculated the mean prediction accuracy across cross-validation folds. Accuracies were represented in units of discriminability (d′) using the formula:

| (Eq. 1) |

where erfinv is the inverse error function and p the proportion of correct predictions.

For tests of transfer between disparity and shading cues, we used a Recursive Feature Elimination method (RFE) (De Martino et al., 2008) to detect sparse discriminative patterns and define the number of voxels for the SVM classification analysis. In each feature elimination step, five voxels were discarded until there remained a core set of voxels with the highest discriminative power. In order to avoid circular analysis, the RFE method was applied independently to the training patterns of each cross-validation fold, resulting in eight sets of voxels (i.e. one set for each test pattern of the leave-one-run out procedure). This was done separately for each experimental condition, with final voxels for the SVM analysis chosen based on the intersection of voxels from corresponding cross-validation folds. A standard SVM was then used to compute within- and between- cue prediction accuracies. This feature selection method was required for transfer, in line with evidence that it improves generalization (De Martino et al., 2008).

We conducted Repeated Measures GLM in SPSS (IBM, Inc.) applying Greenhouse-Geisser correction when appropriate. Regression analyses were also conducted in SPSS. For this analysis, we considered the use of repeated measures MANCOVA (and found results consistent with the regression results); however, the integration indices (defined below) we use are partially correlated between conditions because their calculation depends on the same denominator, violating the GLM’s assumption of independence. We therefore limited our analysis to the relationship between psychophysical and fMRI indices for the same condition, for which the psychophysical and fMRI indices are independent of one another.

Quadratic summation and integration indices

We formulate predictions for the combined cue condition (i.e., disparity + shading) based on the quadratic summation of performance in the component cue conditions (i.e., disparity; shading). As outlined in the Introduction, this prediction is based on the performance of an ideal observer model that discriminates pairs of inputs (visual stimuli or fMRI response patterns) based on the optimal discrimination boundary. Psychophysical tests indicate that this theoretical model matches human performance in combining cues (Hillis et al., 2002; Knill and Saunders, 2003).

To compare measured empirical performance in disparity + shading condition with the prediction derived from the component cue conditions, we calculate a ratio index (Nandy and Tjan, 2008; Ban et al., 2012) whose general form is:

| (Eq. 2) |

where CD, CS, and CD+S are sensitivities for disparity, shading, and the combined cue conditions respectively. If the responses of the detection mechanism to the disparity and shading conditions (CD, CS) are independent of each other, performance when both cues are available (CD+S) should match the quadratic summation prediction, yielding a ratio of 1 and thus an index of zero. A value of less than zero suggests suboptimal detection performance, and a value above zero suggests that the component sources of information are not independent (Nandy and Tjan, 2008; Ban et al., 2012). However, a value above zero does not preclude the response of independent mechanisms: depending on the amount of noise introduced during fMRI measurement (scanner noise, observer movement), co-located but independent responses can yield a positive index (see the fMRI simulations by Ban et al, 2012 in their Supplementary Figure 3). Thus, the integration index alone cannot be taken as definite evidence of cue integration, and therefore needs to be considered in conjunction with the other tests. To assess statistical significance of the integration indices, we used bootstrapped resampling, as our use of a ratio makes distributions non-normal, and thus a non-parametric procedure more appropriate.

Results

Psychophysics

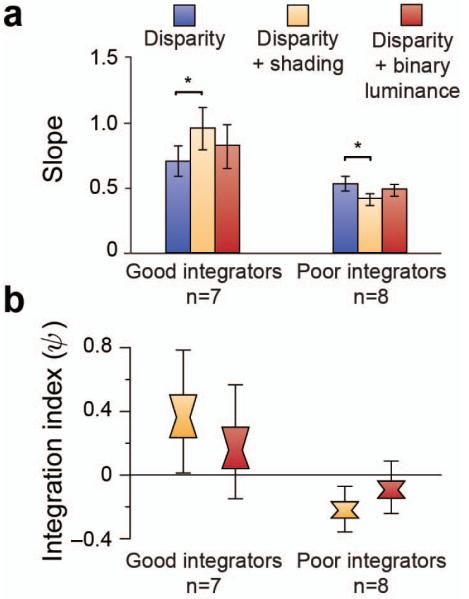

To assess cue integration psychophysically, we measured observers’ sensitivity to slight differences in the depth profile of the stimuli (Fig. 1b). Participants viewed two shapes sequentially, and decided which had the greater depth (that is, which bumps were taller, or which dimples were deeper). By comparing a given standard stimulus against a range of test stimuli, we obtained psychometric functions. We used the slope of these functions to quantify observers’ sensitivity to stimulus differences (where a steeper slope indicates higher sensitivity). To determine whether there was a perceptual benefit associated with adding shading information to the stimuli, we compared performance in the disparity condition with that in the disparity and shading condition. Surprisingly, we found no evidence for enhanced performance in the disparity and shading condition at the group level (F(1,14)<1, p=.38). In light of previous empirical work on cue integration this was unexpected (e.g. (Buelthoff and Mallot, 1988; Doorschot et al., 2001; Vuong et al., 2006; Schiller et al., 2011; Lovell et al., 2012)), and prompted us to consider the significant variability between observers (F(1,14)=62.23, p<.001) in their relative performance in the two conditions. In particular, we found that some participants clearly benefited from the presence of two cues, however others showed no benefit and some actually performed worse relative to the disparity only condition. Poorer performance might relate to individual differences in the assumed direction of the illuminant (Schofield et al., 2011); ambiguity or bistability in the interpretation of shading patterns (Liu and Todd, 2004; Wagemans et al., 2010); and/or differences in cue weights (Knill and Saunders, 2003; Schiller et al., 2011; Lovell et al., 2012) (we return to this issue in the Discussion). To quantify variations between participants in the relative performance in two conditions, we calculated a psychophysical integration index (ψ):

| (Eq. 3) |

where SD+S is sensitivity in the combined condition and SD is sensitivity in the disparity condition. This index is based on the quadratic summation test (Nandy and Tjan, 2008; Ban et al., 2012); and see Methods) where a value above zero suggests that participants integrate the depth information provided by the disparity and shading cues when making perceptual judgments. In this instance we assumed that SD ≈ √(SD2 + SS2) because our attempts to measure sensitivity to differences in depth amplitude defined by shading alone in pilot testing resulted in such poor performance that we could not fit a reliable psychometric function. Specifically, discriminability for the maximum presented depth difference was d′ = 0.3±0.25 for shading alone, in contrast to d′ = 3.9±0.3 for disparity, i.e. SD2 >> SS2.

We rank-ordered participants based on ψ, and thereby formed two groups (Fig. 2): good integrators (n=7 participants for whom ψ > 0) and poor integrators (n=8, ψ < 0). By definition, these post-hoc groups differed in the relative sensitivity to disparity and disparity + shading conditions. Our purpose in forming these groups, however, was to test the link between differences in perception and fMRI responses.

Figure 2.

Psychophysical results. (a) Behavioral tests of integration. Bar graphs represent the between-subjects mean slope of the psychometric function. * indicates p<.05. (b) Psychophysical results as an integration index. Distribution plots show bootstrapped values: the center of the ‘bowtie’ represents the median, the colored area depicts 68% confidence values, and the upper and lower error bars 95% confidence intervals.

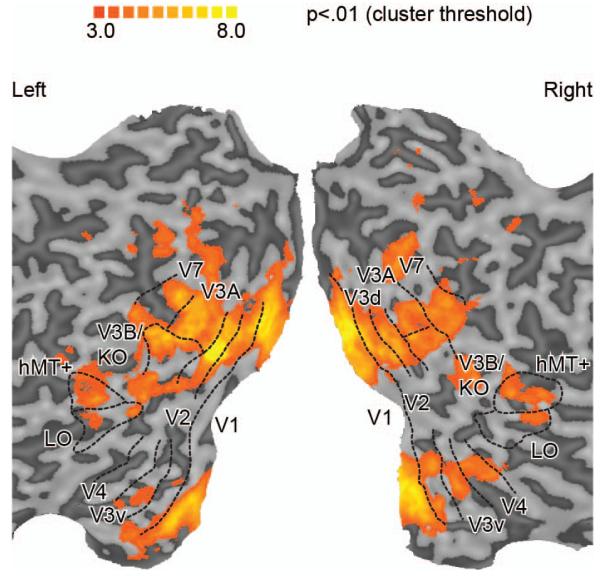

fMRI measures

Before taking part in the main experiment, each participant underwent a separate fMRI session to identify regions of interest (ROIs) within the visual cortex (Fig. 3). We identified retinotopically organized cortical areas based on polar and eccentricity mapping techniques (Sereno et al., 1995; DeYoe et al., 1996; Tootell and Hadjikhani, 2001; Tyler et al., 2005). In addition we identified area LO involved in object processing (Kourtzi and Kanwisher, 2001), the human motion complex (hMT+/V5) (Zeki et al., 1991) and the Kinetic Occipital (KO) region which is localized by contrasting motion-defined contours with transparent motion (Dupont et al., 1997; Zeki et al., 2003). Responses to the KO localizer overlapped with the retinotopically-localized area V3B and were not consistently separable across participants and/or hemispheres (see also (Ban et al., 2012)) so we denote this region as V3B/KO. A representative flatmap of the regions of interest is shown in Fig. 3, and Table 1 provides mean coordinates for V3B/KO.

Figure 3.

Representative flat maps from one participant showing the left and right regions of interest. The sulci are depicted in darker gray than the gyri. Shown on the maps are retinotopic areas, V3B/KO, the human motion complex (hMT+/V5), and lateral occipital (LO) area. The activation on the maps shows the results of a searchlight classifier analysis that moved iteratively throughout the measured cortical volume, discriminating between stimulus configurations. The color code represents the t-value of the classification accuracies obtained. This procedure confirmed that we had not missed any important areas outside those localized independently.

We then measured fMRI responses in each of the ROIs, and were, a priori, particularly interested in the V3B/KO region (Tyler et al., 2006; Ban et al., 2012). We presented stimuli from four experimental conditions (Fig. 1) under two configurations: (a) bumps to the left of fixation, dimples to the right or (b) bumps to the right, dimples to the left, thereby allowing us to contrast fMRI responses to convex vs. concave stimuli.

To analyze our data, we trained a machine learning classifier (support vector machine: SVM) to associate patterns of fMRI voxel activity and the stimulus configuration (convex vs. concave) that gave rise to that activity. We used the performance of the classifier in decoding the stimulus from independent fMRI data (i.e., leave-one-run-out cross-validation) as a measure of the information about the presented stimulus within a particular region of cortex.

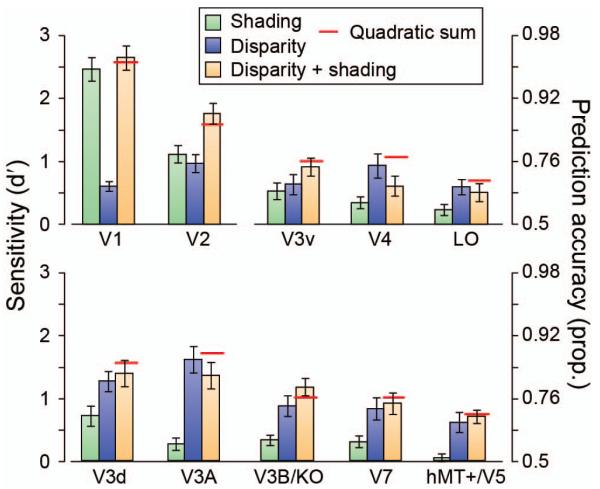

We could reliably decode the stimulus configuration in the four conditions in almost every region of interest (Fig. 4), and there was a clear interaction between conditions and ROIs (F(8.0,104.2)=8.92, p<.001). This widespread sensitivity to differences between convex vs. concave stimuli is not surprising in that a range of features might modify the fMRI response (e.g., distribution of image intensities, contrast edges, mean disparity, etc.). The machine learning classifier may thus decode low-level image features, rather than ‘depth’ per se. We were therefore interested not in overall prediction accuracies between areas (which are influenced by our ability to measure fMRI activity in different anatomical locations). Rather, we were interested in the relative performance between conditions, and whether this related to between-observer differences in perceptual integration. We therefore considered our fMRI data subdivided based on the behavioral results (significant interaction between condition and group (good vs. poor integrators): F(2.0,26.6)=4.52, p=.02).

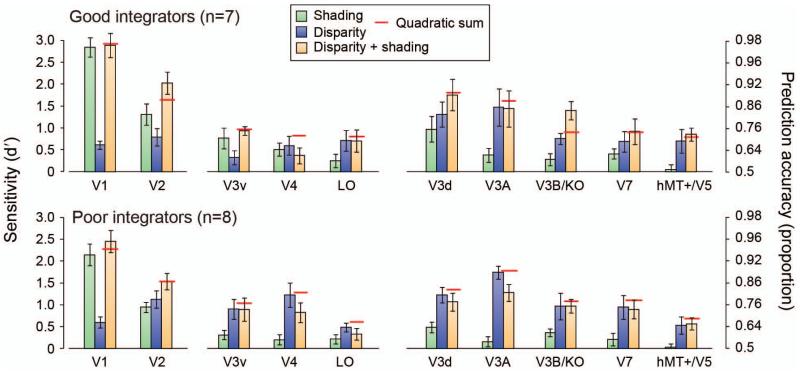

Figure 4.

Performance in predicting the convex vs. concave configuration of the stimuli based on the fMRI data measured in different regions on interest. The bar graphs show the results from the ‘single cue’ experimental conditions, the ‘disparity + shading’ condition, the quadratic summation prediction (horizontal red line). Error bars indicate SEM.

First, we wished to determine whether fMRI decoding performance improved when both depth cues indicated depth differences. Prediction accuracies for the concurrent stimulus (disparity + shading) were statistically higher than the component cues in areas V2 (F(3,39)=7.47, p<.001) and V3B/KO (F(1.6,21.7)=14.88, p<.001). To assess integration, we compared the extent of improvement in the concurrent stimulus relative to a minimum bound prediction (Figs. 4, 5 red lines) based on the quadratic summation of decoding accuracies for ‘single cue’ presentations (Ban et al., 2012). This corresponds to the level of performance expected if disparity signals and shading signals are collocated in a cortical area, but represented independently. If performance exceeds this bound, it suggests that cue representations are not independent, as performance in the ‘single’ cue case was attenuated by the conflicts that result from ‘isolating’ the cue. We found that performance was higher (outside the S.E.M.) than the quadratic summation prediction in areas V2 and V3B/KO. However, this result was only statistically reliable in V3B/KO (Fig. 5). Specifically in V3B/KO, there was a significant interaction between the behavioral group and experimental condition (F(2,26)=5.52, p=.01), with decoding performance in the concurrent (disparity + shading) condition exceeding the quadratic summation prediction for good integrators (F(1,6)=9.27, p=.011), but not for the poor integrators (F(1,7)<1, p=.35); Fig. 5). In V2 the there was no significant difference between the quadratic summation prediction and the measured data in the combined cue conditions (F(2,26)<1, p=.62) nor an interaction (F(2,26)=2.63, p=.091). We quantified the extent of integration using a bootstrapped index (Φ) that contrasted decoding performance in the concurrent condition (d′D+S) with the quadratic summation of performance with ‘single’ cues (d′D and d′S):

| (4) |

Figure 5.

Prediction performance for fMRI data separated into the two groups based on the psychophysical results (‘good’ vs. ‘poor’ integrators). The bar graphs show the results from the ‘single cue’ experimental conditions, the ‘disparity + shading’ condition, the quadratic summation prediction (horizontal red line). Error bars indicate SEM.

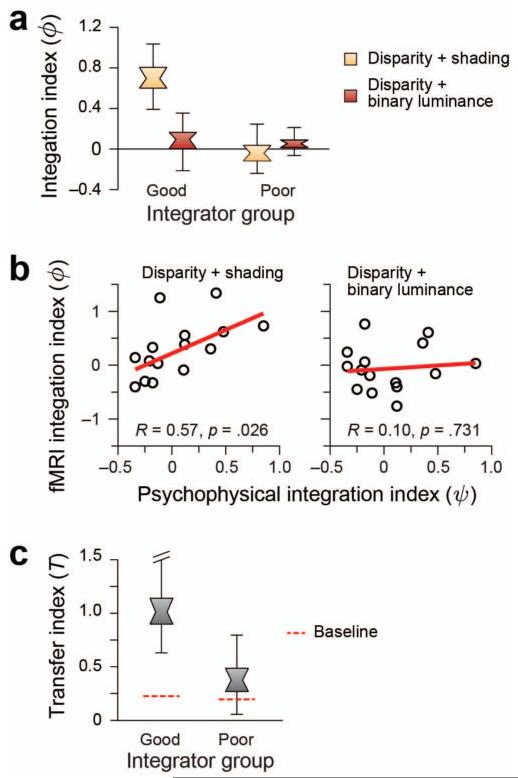

Using this index a value of zero corresponds to the performance expected if information from disparity and shading are collocated, but independent. We found that only in areas V2 and V3B/KO was the integration index for the concurrent condition reliably above zero for the good integrators (Fig. 6a; Table 2).

Figure 6.

(a) fMRI based prediction performance as an integration index for the two groups of participants in area V3B/KO. A value of zero indicates the minimum bound for fusion as predicted by quadratic summation. The index is calculated for the ‘Disparity + shading’ and ‘Disparity + binary shading’ conditions. Data are presented as notched distribution plots. The center of the ‘bowtie’ represents the median, the colored area depicts 68% confidence values, and the upper and lower error bars 95% confidence intervals. (b) Correlation between behavioral and fMRI integration indices in area V3B/KO. Psychophysics and fMRI integration indices are plotted for each participant for disparity + shading and disparity + binary luminance conditions. The Pearson correlation coefficient (R) and p-value are shown. (c) The transfer index values for V3B/KO for the good and poor integrator groups. Using this index, a value of 1 indicates equivalent prediction accuracies when training and testing on the same cue vs. training and testing on different cues. Distribution plots show the median, 68% and 95% confidence intervals. Dotted horizontal lines depict a bootstrapped chance baseline based on the upper 95th centile for transfer analysis obtained with randomly permuted data.

Table 2.

Probabilities associated with obtaining a value of zero for the fMRI integration index in the (i) disparity + shading condition and (ii) luminance control condition. Values are from a bootstrapped resampling of the individual participants’ data using 10,000 samples. Bold formatting indicates Bonferroni-corrected significance.

| Cortical area | Disparity + Shading | Luminance control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good integrators |

Poor integrators |

Good integrators |

Poor integrators |

|

| V1 | 0.538 | 0.157 | 0.999 | 0.543 |

| V2 | 0.004 | 0.419 | 0.607 | 0.102 |

| V3v | 0.294 | 0.579 | 0.726 | 1.000 |

| V4 | 0.916 | 0.942 | 0.987 | 0.628 |

| LO | 0.656 | 0.944 | 0.984 | 0.143 |

| V3d | 0.253 | 0.890 | 0.909 | 0.234 |

| V3A | 0.609 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.961 |

| V3B/KO | <0.001 | 0.629 | 0.327 | 0.271 |

| V7 | 0.298 | 0.595 | 0.844 | 0.620 |

| hMT+/V5 | 0.315 | 0.421 | 0.978 | 0.575 |

To provide additional evidence for neuronal responses related to depth estimation, we used the binary luminance stimuli as a control. We constructed these stimuli such that they contained a very obvious low-level feature that approximated luminance differences in the shaded stimuli but did not, per se, evoke an impression of depth. As the fMRI response in a given area may reflect low-level stimulus differences (rather than depth from shading), we wanted to rule out the possibility that improved decoding performance in the concurrent disparity + shading condition could be explained on the basis that two separate stimulus dimensions (disparity and luminance) drive the fMRI response. The quadratic summation test should theoretically rule this out; nevertheless, we contrasted decoding performance in the concurrent condition vs. the binary control (disparity + binary luminance) condition. We reasoned that if enhanced decoding is related to the representation of depth, superquadratic summation effects would be limited to the concurrent condition. Based on a significant interaction between subject group and condition (F(2,26)=5.52, p=.01), we found that this was true for the good integrator subjects in area V3B/KO: sensitivity in the concurrent condition was above that in the binary control condition (F(1,6)=14.69, p=.004). By contrast, sensitivity for the binary condition in the poor integrator subjects matched that of the concurrent group (F(1,7)<1, p=.31) and was in line with quadratic summation. Results from other regions of interest (Table 2) did not suggest the clear (or significant) differences that were apparent in V3B/KO.

As a further line of evidence, we used regression analyses to test the relationship between psychophysical and fMRI measures of integration. While we would not anticipate a one-to-one mapping between them (the fMRI data were obtained for differences between concave vs. convex shapes, while the psychophysical tests measured sensitivity to slight differences in the depth profile) our group-based analysis suggested a correspondence. We found a significant relationship between the fMRI and psychophysical integration indices in V3B/KO (Fig. 6b) for the concurrent (R=0.57, p=.026) but not the binary luminance (R=0.10, p=.731) condition. This result was specific to area V3B/KO (Table 3), and, in line with the preceding analyses, suggests a relationship between activity in area V3B/KO and the perceptual integration of disparity and shading cues to depth.

Table 3.

Results for the regression analyses relating the psychophysical and fMRI integration indices in each region of interest. The table shows the Pearson correlation coefficient (R) and the signficance of the fit as a p value for the ‘Disparity + shading’ and ‘Disparity + binary luminance’ conditions.

| Disparity + shading | Disparity + binary luminance |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical area | R | p-value | R | p-value |

| V1 | −0.418 | 0.121 | −0.265 | 0.340 |

| V2 | 0.105 | 0.709 | −0.394 | 0.146 |

| V3v | −0.078 | 0.782 | 0.421 | 0.118 |

| V4 | 0.089 | 0.754 | −0.154 | 0.584 |

| LO | 0.245 | 0.379 | −0.281 | 0.311 |

| V3d | 0.194 | 0.487 | −0.157 | 0.577 |

| V3A | 0.232 | 0.405 | −0.157 | 0.577 |

| V3B/KO | 0.571 | 0.026 | 0.097 | 0.731 |

| V7 | 0.019 | 0.946 | −0.055 | 0.847 |

| hMT+/V5 | 0.411 | 0.128 | −0.367 | 0.178 |

As a final assessment of whether fMRI responses related to depth structure from different cues, we tested whether training the classifier on depth configurations from one cue (e.g. shading) afforded predictions for depth configurations specified by the other (e.g. disparity). To compare the prediction accuracies on this cross-cue transfer with baseline performance (i.e., training and testing on the same cue), we used a bootstrapped transfer index:

| (5) |

where d′T is between-cue transfer performance and ½ (d′D + d′S) is the average within-cue performance. A value of one using this index indicates that prediction accuracy between cues equals that within cues. To provide a baseline for the transfer that might occur by chance, we calculated the transfer index on data sets for which we randomly shuffled the condition labels, such that we broke the relationship between fMRI response and the stimulus that evoked the response. We calculated shuffled transfer performance 1000 times for each ROI, and used the 95th centile of the resulting distribution of transfer indices as the cut-off for significance. We found reliable evidence for transfer between cues in area V3B/KO (Fig. 6c) for the good, but not poor, integrator groups. Further, this effect was specific to V3B/KO and was not observed in other areas (Table 4). Together with the previous analyses, this result suggests a degree of equivalence between representations of depth from different cues in V3B/KO that is related to an individual’s perceptual interpretation of cues.

Table 4.

Probabilities associated with the transfer between disparity and shading producing a Transfer index above the random (shuffled) baseline. These p-values are calculated using bootstrapped resampling with 10,000 samples. Bold formating indicates Bonferroni-corrected significance.

| Cortical area | Good integrators | Poor integrators |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | 0.247 | 0.748 |

| V2 | 0.788 | 0.709 |

| V3v | 0.121 | 0.908 |

| V4 | 0.478 | 0.062 |

| LO | 0.254 | 0.033 |

| V3d | 0.098 | 0.227 |

| V3A | 0.295 | 0.275 |

| V3B/KO | <0.001 | 0.212 |

| V7 | 0.145 | 0.538 |

| hMT+/V5 | 0.124 | 0.302 |

To ensure we had not missed any important loci of activity outside the areas we sampled using our ROI localizers, we conducted a searchlight classification analysis (Kriegeskorte et al., 2006) in which we moved a small aperture (9 mm) through the sampled cortical volume performing MVPA on the difference between stimulus configurations for the concurrent cue condition (Fig. 3). This analysis indicated that discriminative signals about stimulus differences were well captured by our region of interest definitions.

Our main analyses considered MVPA of the fMRI responses partitioned into two groups based on psychophysical performance. To ensure that differences in MVPA prediction performance between groups related to the pattern of voxel responses for depth processing, rather than the overall responsiveness of different regions of interest, we calculated the average fMRI activations (% signal change) in each ROI for the two groups of participants. Reassuringly, we found no evidence for statistically reliable differences between groups across conditions and ROIs (i.e., no ROI × group interaction: F(3.3, 43.4)<1, p=.637; no condition × group interaction: F(3.5, 45.4)<1, p=.902; and no ROI × condition × group interaction: F(8.6, 112.2)=1.06, p=.397). Moreover, limiting this analysis to V3B/KO provided no evidence for a difference in the percent signal change between groups (i.e., no condition × group interaction: F(3.1, 40.3)<1, p=.586). Further, we ensured that we had sampled from the same cortical location in both groups by calculating the mean Talairach location of V3B/KO subdivided by groups (Table 1). This confirmed that we had localized the same cortical region in both groups of participants.

To guard against artifacts complicating the interpretation of our results, we took specific precautions during scanning to control attentional allocation and eye movements. First, participants performed a demanding vernier judgment task at fixation. This ensured equivalent attentional allocation across conditions, and, as the task was unrelated to the depth stimuli, psychophysical judgments and fMRI responses were not confounded and could not thereby explain between-subject differences. Second, the attentional task served to provide a subjective measure of eye vergence (Popple et al., 1998). In particular, participants judged the relative location of a small target flashed (250 ms) to one eye, relative to the upper vertical nonius line (presented to the other eye) (Fig. 1d). We fit the proportion of “target is to the right” responses as a function of the target’s horizontal displacement. Bias (i.e. deviation from the desired vergence position) in this judgment was around zero suggesting that participants were able to maintain fixation with the required vergence angle. Using a repeated measures ANOVA we found that there were no significant differences in bias between stimulus conditions (F1.5,21.4=2.59, p =0.109), sign of curvature (F1,14=1.43, p=0.25), and no interaction (F2.2,30.7=1.95, p=0.157). Further, there were no differences in the slope of the psychometric functions: no effect of condition (F3,42 < 1, p =0.82) or curvature (F1,14 < 1, p =0.80), and no interaction (F3,42 < 1, p =0.85).

Third, our stimuli were constructed to reduce the potential for vergence differences: disparities to the left and right of the fixation point were equal and opposite, a constant low spatial frequency pattern surrounded the stimuli, and participants used horizontal and vertical nonius lines to monitor their eye vergence. Finally, we recorded horizontal eye movements for three participants inside the scanner bore in a separate session. Analysis of the eye position signals suggested that the three participants were able to maintain steady fixation: in particular, deviations in mean eye position were < 1 degree from fixation. In particular, we found no significant difference between conditions in mean eye position (F3,6 < 1, p = 0.99), number of saccades (F3,6 < 1, p = 0.85), or saccade amplitude (F3,6 = 1.57, p = 0.29).

Discussion

Here we provide three lines of evidence that activity in dorsal visual area V3B/KO reflects the integration of disparity and shading depth cues in a perceptually-relevant manner. First, we used a quadratic summation test to show that performance in concurrent cue settings improves beyond that expected if depth from disparity and shading are collocated but represented independently. Second, we showed that this result was specific to stimuli that are compatible with a three-dimensional interpretation of shading patterns. Third, we found evidence for cross-cue transfer. Importantly, the strength of these results in V3B/KO varied between individuals in a manner that was compatible with their perceptual use of integrated depth signals.

These findings complement evidence for the integration of disparity and relative motion in area V3B/KO (Ban et al., 2012), and suggest both a strong link with perceptual judgments and a more generalized representation of depth structure. Such generalization is far from trivial: binocular disparity is a function of an object’s 3D structure, its distance from the viewer and the separation between the viewer’s eyes; by contrast, shading cues (i.e., intensity distributions in the image) depend on the type of illumination, the orientation of the light source with respect to the 3D object, and the reflective properties of the object’s surface (i.e., the degree of Lambertian and Specular reflectance). As such disparity and shading provide complementary shape information: they have quite different generative processes, and their interpretation depends on different constraints and assumptions (Blake et al., 1985; Doorschot et al., 2001). Taken together, these results indicate that the 3D representations in the V3B/KO region are not specific to specific cue pairs (i.e., disparity-motion) and generalize to more complex forms of 3D structural information (i.e., local curvature). This points to an important role for higher portions of the dorsal visual cortex in computing information about the 3D structure of the surrounding environment.

Individual differences in disparity and shading integration

One striking, and unexpected feature of our findings was that we observed significant between-subject variability in the extent to which shading enhanced performance, with some subjects benefitting, and others actually performing worse. What might be responsible for this variation in performance? While shading cues support reliable judgments of ordinal structure (Ramachandran, 1988), shape is often underestimated (Mingolla and Todd, 1986) and subject to systematic biases related to the estimated light source position (Pentland, 1982; Curran and Johnston, 1996; Sun and Perona, 1998; Mamassian and Goutcher, 2001) and light source composition (Schofield et al., 2011). Moreover assumptions about the position of the light source in the scene are often esoteric: most observers assume overhead lighting, but the strength of this assumption varies considerably (Liu and Todd, 2004; Thomas et al., 2010; Wagemans et al., 2010), and some observers assume lighting from below (e.g., 3 of 15 participants in Schofield et al, 2011). Our disparity + shading stimuli were designed such that the cues indicated the same depth structure to an observer who assumed lighting from above. Therefore, it is quite possible that observers experienced conflict between the shape information specified by disparity, and that determined by their interpretation of the shading pattern. Such participants would be ‘poor integrators’ only inasmuch as they failed to share the assumptions typically made by observers (i.e., lighting direction, lighting composition, and Lambertian surface reflectance) when interpreting shading patterns. In addition, participants may have experienced alternation in their interpretation of the shading cue across trials (i.e., a weak light-from-above assumption which has been observed quite frequently (Thomas et al., 2010; Wagemans et al., 2010)); aggregating such bimodal responses to characterize the psychometric function would result in more variable responses in the concurrent condition than in the ‘disparity’ alone condition which was not subject to perceptual bistability. Such variations could also result in fMRI responses that vary between trials; in particular, fMRI responses in V3B/KO change in line with different perceptual interpretations of the same (ambiguous) 3D structure indicated by shading cues (Preston et al., 2009). This variation in fMRI responses could thereby account for reduced decoding performance for these participants.

An alternative possibility is that some of our observers did not integrate information from disparity and shading because they are inherently poor integrators. While cue integration both within and between sensory modalities has been widely reported in adults, it has a developmental trajectory and young children do not integrate signals (Gori et al., 2008; Nardini et al., 2008; Nardini et al., 2010). This suggests that cue integration may be learnt via exposure to correlated cues (Atkins et al., 2001) where the effectiveness of learning can differ between observers (Ernst, 2007). Further, while cue integration may be mandatory for many cues where such correlations are prevalent (Hillis et al., 2002), inter-individual variability in the prior assumptions which are used to interpret shading patterns may cause some participants to lack experience of integrating shading and disparity cues (at least in terms of how these are studied in the laboratory).

These different possibilities are difficult to distinguish from previous work that has looked at the integration of disparity and shading signals and reported individual results. This work indicated that perceptual judgments are enhanced by the combination of disparity and shading cues (Buelthoff and Mallot, 1988; Doorschot et al., 2001; Vuong et al., 2006; Schiller et al., 2011; Lovell et al., 2012). However, between-participant variation in such enhancement is difficult to assess given that low numbers of participants were used (mean per study = 3.6, max = 5) a sizeable proportion of whom were not naïve to the purposes of the study. Here we find evidence for integration in both authors H.B. and A.W., but considerable variability among the naïve participants. In common with Wagemans et al (2010), this suggests that interobserver variability may be significant in the interpretation of shading patterns in particular, and integration more generally, providing a stimulus for future work to explain the basis for such differences.

Responses in other regions of interest

When presenting the results for all the participants, we noted that performance in the disparity + shading condition was statistically higher than for the component cues in area V2 as well as in V3B/KO (Fig. 3). Our subsequent analyses did not provide evidence that V2 is a likely substrate for the integration of disparity and shading cues. However, it is possible that the increased decoding performance—around the level expected by quadratic summation—is due to parallel representations of disparity and shading information. It is unlikely that either signal is fully elaborated, but V2’s more spatially extensive receptive fields may provide important information about luminance and contrast variations across the scene that provide signals important when interpreting shape from shading (Schofield et al., 2010).

Previous work (Georgieva et al., 2008) suggested that the processing of 3D structure from shading is primarily restricted in its representation to a ventral locus near the area we localize as LO (although Gerardin et al. (2010) suggested V3B/KO is also involved and Taira et al. (2001) reported widespread responses). Our fMRI data supported only weak decoding of depth configurations defined by shading in LO, and more generally across higher portions of both the dorsal and ventral visual streams (Figs. 3, 4). Indeed, the highest prediction performance of the MVPA classifier for shading (relative to overall decoding accuracies in each ROI) was observed in V1 and V2 which is likely to reflect low-level image differences between stimulus configurations rather than an estimate of shape from shading per se. Nevertheless, our findings from V3B/KO make it clear that information provided by shading contributes to fMRI responses in higher portions of the dorsal stream. Why then is performance in the ‘shading’ condition so low? Our experimental stimuli purposefully provoked conflicts between the disparity and shading information in the ‘single cue’ conditions. Therefore, the conflicting information from disparity that the viewed surface was flat is likely to have attenuated fMRI responses to the ‘shading alone’ stimulus. Indeed, given that sensitivity to disparity differences was so much greater than for shading, it might appear surprising that we could decode shading information at all. Previously, we used mathematical simulations to suggest that area V3B/KO contains a mixed population of responses, with some units responding to individual cues and others fusing cues into a single representation (Ban et al., 2012). Thus, residual fMRI decoding performance for the shading condition may reflect responses to non-integrated processing of the shading aspects of the stimuli. This mixed population could help support a robust perceptual interpretation of stimuli that contain significant cue conflicts: for example, the reader should still be able to gain an impression of the 3D structure of the shaded stimuli in Fig. 1, despite conflicts with disparity).

In summary, previous fMRI studies suggest a number of locations in which three-dimensional shape information might be processed (Sereno et al., 2002; Nelissen et al., 2009). Here we provide evidence that area V3B/KO plays an important role in integrating disparity and shading cues, compatible with the notion that it represents 3D structure from different signals (Tyler et al., 2006) that are subject to different prior constraints (Preston et al., 2009). Our results suggest that V3B/KO is involved in 3D estimation from qualitatively different depth cues, and its activity may underlie perceptual judgments of depth.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [H22,290], the Wellcome Trust [095183/Z/10/Z], the EPSRC [EP/F026269/1] and by the Birmingham University Imaging Centre.

References

- Anzai A, Ohzawa I, Freeman RD. Joint-encoding of motion and depth by visual cortical neurons: neural basis of the Pulfrich effect. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:513–518. doi: 10.1038/87462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins JE, Fiser J, Jacobs RA. Experience-dependent visual cue integration based on consistencies between visual and haptic percepts. Vision Research. 2001;41:449–461. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban H, Preston TJ, Meeson A, Welchman AE. The integration of motion and disparity cues to depth in dorsal visual cortex. Nature Neurosci. 2012;15:636–643. doi: 10.1038/nn.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belhumeur PN, Kriegman DJ, Yuille AL. The bas-relief ambiguity. International Journal of Computer Vision. 1999;35:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Blake A, Zisserman A, Knowles G. Surface descriptions from stereo and shading. Image Vision Comput. 1985;3:183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley DC, Qian N, Andersen RA. Integration of motion and stereopsis in middle temporal cortical area of macaques. Nature. 1995;373:609–611. doi: 10.1038/373609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buelthoff HH, Mallot HA. Integration of Depth Modules - Stereo and Shading. J Opt Soc Am: A. 1988;5:1749–1758. doi: 10.1364/josaa.5.001749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge J, Fowlkes CC, Banks MS. Natural-scene statistics predict how the figure-ground cue of convexity affects human depth perception. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7269–7280. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5551-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran W, Johnston A. The effect of illuminant position on perceived curvature. Vision Res. 1996;36:1399–1410. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(95)00213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Martino F, Valente G, Staeren N, Ashburner J, Goebel R, Formisano E. Combining multivariate voxel selection and support vector machines for mapping and classification of fMRI spatial patterns. Neuroimage. 2008;43:44–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis GC, Uka T. Coding of horizontal disparity and velocity by MT neurons in the alert macaque. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1094–1111. doi: 10.1152/jn.00717.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoe EA, Carman GJ, Bandettini P, Glickman S, Wieser J, Cox R, Miller D, Neitz J. Mapping striate and extrastriate visual areas in human cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2382–2386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorschot PCA, Kappers AML, Koenderink JJ. The combined influence of binocular disparity and shading on pictorial shape. Perception & Psychophysics. 2001;63:1038–1047. doi: 10.3758/bf03194522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosher BA, Sperling G, Wurst SA. Tradeoffs between stereopsis and proximity luminance covariance as determinants of perceived 3D structure. Vis Res. 1986;26:973–990. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(86)90154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont P, De Bruyn B, Vandenberghe R, Rosier AM, et al. The kinetic occipital region in human visual cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7:283–292. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst MO. Learning to integrate arbitrary signals from vision and touch. J Vis. 2007;7(7):1–14. doi: 10.1167/7.5.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming RW, Dror RO, Adelson EH. Real-world illumination and the perception of surface reflectance properties. Journal of Vision. 2003;3:347–368. doi: 10.1167/3.5.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva SS, Todd JT, Peeters R, Orban GA. The extraction of 3D shape from texture and shading in the human brain. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:2416–2438. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerardin P, Kourtzi Z, Mamassian P. Prior knowledge of illumination for 3D perception in the human brain. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16309–16314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006285107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori M, Del Viva M, Sandini G, Burr DC. Young children do not integrate visual and haptic form information. Curr Biol. 2008;18:694–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, Kushnir T, Hendler T, Malach R. The dynamics of object-selective activation correlate with recognition performance in humans. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:837–843. doi: 10.1038/77754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis JM, Ernst MO, Banks MS, Landy MS. Combining sensory information: mandatory fusion within, but not between, senses. Science. 2002;298:1627–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1075396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn BKP. Obtaining shape from shading information. In: Winston PH, editor. The Psychology of Computer Vision. McGraw Hill; New York: 1975. pp. 115–155. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen P, Vogels R, Orban GA. Three-dimensional shape coding in inferior temporal cortex. Neuron. 2000;27:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten D, Mamassian P, Yuille A. Object perception as Bayesian inference. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:271–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom FAA. Color brings relief to human vision. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6:641–644. doi: 10.1038/nn1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knill DC, Saunders JA. Do humans optimally integrate stereo and texture information for judgments of surface slant? Vision Research. 2003;43:2539–2558. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(03)00458-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenderink JJ, van Doorn AJ. Shape and Shading. In: Chalupa LM, Werner JS, editors. The Visual Neurosciences. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kourtzi Z, Kanwisher N. Representation of perceived object shape by the human lateral occipital complex. Science. 2001;293:1506–1509. doi: 10.1126/science.1061133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegeskorte N, Goebel R, Bandettini P. Information-based functional brain mapping. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:3863–3868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600244103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landy MS, Maloney LT, Johnston EB, Young M. Measurement and Modeling of Depth Cue Combination - in Defense of Weak Fusion. Vision Res. 1995;35:389–412. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00176-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson J, Heeger DJ, Landy MS. Orientation selectivity of motion-boundary responses in human visual cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:2940–2950. doi: 10.1152/jn.00400.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YL, Saunders JA. Stereo improves 3D shape discrimination even when rich monocular shape cues are available. J Vis. 2011;11 doi: 10.1167/11.9.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Todd JT. Perceptual biases in the interpretation of 3D shape from shading. Vision Res. 2004;44:2135–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell PG, Bloj M, Harris JM. Optimal integration of shading and binocular disparity for depth perception. J Vision. 2012;12:1–18. doi: 10.1167/12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamassian P, Goutcher R. Prior knowledge on the illumination position. Cognition. 2001;81:B1–B9. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(01)00116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingolla E, Todd JT. Perception of Solid Shape from Shading. Biol Cybernetics. 1986;53:137–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00342882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandy AS, Tjan BS. Efficient integration across spatial frequencies for letter identification in foveal and peripheral vision. J Vis. 2008;8(3):1–20. doi: 10.1167/8.13.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardini M, Bedford R, Mareschal D. Fusion of visual cues is not mandatory in children. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17041–17046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001699107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardini M, Jones P, Bedford R, Braddick O. Development of cue integration in human navigation. Curr Biol. 2008;18:689–693. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen K, Joly O, Durand JB, Todd JT, Vanduffel W, Orban GA. The Extraction of Depth Structure from Shading and Texture in the Macaque Brain. Plos One. 2009;4:e8306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentland AP. Finding the illuminant direction. J Opt Soc Am. 1982;72:448–455. [Google Scholar]

- Popple AV, Smallman HS, Findlay JM. The Area of Spatial Integration for Initial Horizontal Disparity Vergence. Vision Res. 1998;38:319–326. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston TJ, Kourtzi Z, Welchman AE. Adaptive estimation of three-dimensional structure in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1688–1698. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5021-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston TJ, Li S, Kourtzi Z, Welchman AE. Multivoxel Pattern Selectivity for Perceptually Relevant Binocular Disparities in the Human Brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:11315–11327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2728-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran VS. Perception of Shape from Shading. Nature. 1988;331:163–166. doi: 10.1038/331163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards W. Structure from Stereo and Motion. J Opt Soc Am: A. 1985;2:343–349. doi: 10.1364/josaa.2.000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller PH, Slocum WM, Jao B, Weiner VS. The integration of disparity, shading and motion parallax cues for depth perception in humans and monkeys. Brain Res. 2011;1377:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield AJ, Rock PB, Georgeson MA. Sun and sky: Does human vision assume a mixture of point and diffuse illumination when interpreting shape-from-shading? Vision Res. 2011;51:2317–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield AJ, Rock PB, Sun P, Jiang XY, Georgeson MA. What is second-order vision for? Discriminating illumination versus material changes. J Vision. 2010;10 doi: 10.1167/10.9.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serences JT, Boynton GM. The representation of behavioral choice for motion in human visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12893–12899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4021-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno ME, Trinath T, Augath M, Logothetis NK. Three-dimensional shape representation in monkey cortex. Neuron. 2002;33:635–652. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00598-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno MI, Dale AM, Reppas JB, Kwong KK, Belliveau JW, Brady TJ, Rosen BR, Tootell RB. Borders of multiple visual areas in humans revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Science. 1995;268:889–893. doi: 10.1126/science.7754376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Orban GA, De Maziere PA, Janssen P. A Distinct Representation of Three-Dimensional Shape in Macaque Anterior Intraparietal Area: Fast, Metric, and Coarse. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:10613–10626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6016-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Perona P. Where is the sun? Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:183–184. doi: 10.1038/630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira M, Nose I, Inoue K, Tsutsui K. Cortical areas related to attention to 3D surface structures based on shading: An fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2001;14:959–966. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R, Nardini M, Mareschal D. Interactions between “light-from-above” and convexity priors in visual development. J Vis. 2010;10:6. doi: 10.1167/10.8.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WB, Fleming RW, Creem-Regehr SH, Stefanucci JK. Illumination, shading and shadows. In: Visual perception from a computer graphics perspective. Taylor and Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tootell RB, Hadjikhani N, Hall EK, Marrett S, Vanduffel W, Vaughan JT, Dale AM. The retinotopy of visual spatial attention. Neuron. 1998;21:1409–1422. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80659-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tootell RBH, Hadjikhani N. Where is ‘dorsal V4’ in human visual cortex? Retinotopic, topographic and functional evidence. Cerebral Cortex. 2001;11:298–311. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.4.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler CW, Likova LT, Kontsevich LL, Wade AR. The specificity of cortical region KO to depth structure. Neuroimage. 2006;30:228–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler CW, Likova LT, Chen C-C, Kontsevich LL, Wade AR. Extended Concepts of Occipital Retinotopy. Current Medical Imaging Reviews. 2005;1:319–329. [Google Scholar]

- Vuong QC, Domini F, Caudek C. Disparity and shading cues cooperate for surface interpolation. Perception. 2006;35:145–155. doi: 10.1068/p5315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagemans J, van Doorn AJ, Koenderink JJ. The shading cue in context. i-Perception. 2010;1:159–177. doi: 10.1068/i0401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeki S, Perry RJ, Bartels A. The processing of kinetic contours in the brain. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:189–202. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeki S, Watson JD, Lueck CJ, Friston KJ, Kennard C, Frackowiak RS. A direct demonstration of functional specialization in human visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1991;11:641–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00641.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]