Summary

Survey data on contraceptive use for about 80 countries are related to measures of contraceptive access, by method, from 1999 to 2009. Cross-tabulation and correlational methods are employed, with geographic comparisons and time trends. Total prevalence of use for five modern contraceptive methods correlates well to a variety of access measures. Greater access is also accompanied by a better balance among methods for both access and use. Sub-Saharan African countries show similar patterns though at lower levels. Improved access to multiple methods is consistently associated with higher levels of contraceptive use.

Introduction

Since the mid-1960s hundreds of national surveys have documented the historic rise in contraceptive use. On average, use has grown at about one percentage point a year, or 10 percentage points in ten years (for example from 30% to 40% of married/in union women of reproductive age using contraception). For the developing world as a whole, use has grown to exceed 60% of married/in union women of reproductive age (UN Population Division, 2011).

The types and variety of methods available to large populations are among the determinants of contraceptive use. Prior to the mid-1960s, there were few contraceptive methods to offer. Since then, the contraceptive landscape has been transformed with the appearance of the IUD, the pill, simpler sterilization, improved condoms, and later, the injectable. Existing methods have been improved (e.g. low dose and progestin-only pills, and various types of IUDs and implants, and delivery systems for injectables) and new methods are on the horizon. While the main methods theoretically spread through family planning programmes in much of the developing world, some countries in fact still make only a minimum of contraceptive choices available to their general populations. Pakistan and the Philippines make only the pill and condom available to over half of the population. In Africa, Nigeria makes no method except the condom available to over half of the population; in most sub-Saharan African countries the pill and condom are the main methods offered to most people, and they suffer from high discontinuation and pregnancy rates (based on data from the 2009 round of the Family Planning Effort scores, explained below.)

The purpose of this paper is to specify the relationship between access to a range of contraceptive methods and the use of those methods. The relationship is examined from a variety of perspectives, through multiple analyses, and across different years, contraceptive methods and regions. The analysis uses evidence of access and use for six contraceptive methods and for the years 1999, 2004 and 2009, with some comparisons of sub-Saharan African countries with countries from other regions, totalling more than 60 countries.

Much of the literature on the relationship between access to contraception and its overall use focuses on the effect of adding one or methods to the previous mix. The reasoning for these studies is that after many decades of improvements in contraceptive technology, no single method has emerged that satisfies all needs. Each method has its own shortcomings: it is not reversible, it carries unpleasant side-effects, it is costly, it requires a clinical vaginal procedure, or it conflicts with religious tenets. However, each method does work for some women and couples; therefore each method added can serve another subgroup in the population and add to total use.

Numerous studies from the early experience of developing countries support the link between easier access to contraception and the greater use of it. Freedman & Berelson (1976) showed that during the early emergence of national family planning programmes, the addition of each new method raised total contraceptive use. In Korea in 1964 the IUD was added to the national programme through the network of private physicians, and within three years one in eight married/in union women were using it, more than replacing a decline in traditional methods, while other modern methods remained constant (Kim & Ross, 2007). In Thailand the Ministry of Public Health in 1970 added the pill to the family planning programme through the national network of auxiliary nurse midwives; its use rose rapidly to 20% of married/in union women and by 1975 one in seven married/in union women were using it, double that of the pre-existing methods (Rosenfield & Min, 2007). In Egypt in 1985 regulatory constraints to IUD provision were removed and the new copper-T IUD was introduced. Within four years its prevalence of use doubled, from 8% to 16% (Robinson & El-Zanaty, 2007).

Additional national and local studies have found links between access and use. In Colombia, Korea and Malaysia use declined regularly according to the perceived travel time to a clinic (Rodriguez, 1978). In Thailand, use increased according to the number of different sources of contraception in villages, reducing travel time to the nearest one (Chamratrithirong & Kamnuansilpa, 1984). In Mexico and rural Korea, national survey data showed use to be greater where women believed contraceptive services to be readily available and lived in areas where contraceptive outlets were located nearby; moreover, unmet need was less (Tsui, 1982). A study of four Philippines towns concluded that increasing clinic density would put services closer to more people and greatly reduce the average distance for clients (Lynch & Aganon, 1974). Successive concentric bands, lying farther from a health centre, have larger diameters and contain larger areas and populations; therefore more outlying service points are needed to keep travel time down. A comparison of 21 countries participating in the World Fertility Survey showed travel distances and time to vary sharply among contraceptive methods (Jones, 1984). A study of 36 countries with 1982 national data found use to rise from 10% to over 60% as the number of available modern contraceptive methods increased from none to 5–6 (Lapham & Mauldin, 1985). These various results were consistent with the 1971 simulation study by Robert Potter (1971) on the limitations of a single method, demonstrating that the normal duration of use of the IUD alone, even allowing for reinsertions, left many women with no alternative protection for the reproductive years remaining, apart from multiple abortions.

Jain (1989) extended that work to show that India's heavy reliance on sterilization would be inadequate to reach its goal of a 2.1 total fertility rate by 2020 without extending its use unrealistically into young age groups. By broadening the method mix the goal would become more feasible, with younger couples using reversible methods. Chao et al. (1994) obtained a very similar result for India using a computer simulation of alternative method mixes. Substantial important work appeared in Bulatao et al. (1989) in a volume devoted to determinants of contraceptive choice in Asia and the United States.

In work on Taiwan, Jain (1989) noted the large increase in total duration of contraceptive use when multiple methods were considered. At 30 months after an IUD insertion, the percentage still using the IUD, including reinsertions, was 47%, but an additional 26% were using other available methods after giving up on the IUD. He extended the original Freedman and Berelson work to show that, with 1982 data, the widespread addition of one method would raise contraceptive use by about 12 percentage points (e.g. from 30% to 42% using), based upon the correlation across countries between an access index and prevalence of use. Choe & Bulatao (1992) stressed differences in the mix of methods according to life stage, from before marriage to the interval between marriage and first birth, then between births, and finally after the last birth. The actual method mix found in survey information for Nepal and Indonesia showed shortfalls both in use and in the numbers of unplanned births resulting from distortions in the mix. An important analysis by Sullivan et al. (2006) examined highly distorted contraceptive method mixes. They defined a skewed method mix as a single method constituting 50% or more of all contraceptive use in a country. Of 96 countries, 34 had a skewed mix: sixteen in which traditional methods dominated, most in sub-Saharan Africa; four in which female sterilization dominated, in India and three in Latin America; and fourteen that relied either on the pill, or IUD, or injectable, spread over various regions. Reasons for distorted method mixes are multiple, including poor access to a broad range of methods.

For the developing world in general, Darroch et al. (2011) have assessed the potential for reducing unmet needs for contraceptive use, given improved options among contraceptive choices. They stress that even when improved methods are available they suffer from such defects as side-effects, or the necessity for partner compliance and medical services. Better contraceptive technology is needed both to improve current methods and to develop new ones. They estimate that if method-related reasons for non-use of modern contraception were overcome, unintended pregnancies could be reduced by as much as 59% in sub-Saharan Africa and South-Central and South-East Asia.

The overall relationship between access and contraceptive use, employing ratings of contraceptive access together with measures of contraceptive use, by method, was explored by Ross et al. (2002). The present article provides an updated analysis of several features of that study by using the 1999, 2004 and 2009 rounds of the Family Planning Effort scores, described below. All rounds of the Family Planning Programme Effort scores measured access to the IUD, pill, male and female sterilization and the condom. The 2004 and 2009 rounds measured access to the injectable, separately from the pill; previously the injectable was used less by women and so was merged with access to the pill.

A word is required as to the meaning of ‘contraceptive access’. Whether a variety of method choices are easily available to a woman or couple depends upon the physical closeness of a site for each method and upon low cost. In addition, the absence of barriers is important, and they can be multiple: regulations against young or unmarried women for any method, or against women with no or few children (for sterilization); repeated clearances by obstetricians/gynaecologists or general practitioners; long waiting lines; supply outages; and social awkwardness, as when women obtain condoms. Side-effects of the available methods also make them less inviting. Empirical measures for these obstacles vary, and no single one can capture them all.

However, a single measure of access to contraception has been used in a time series running from 1972 to 2009, for over 80 countries, and it is used here to test the relationship of actual contraceptive use to access defined broadly. It is necessarily approximate, as a trade-off for nearly universal coverage of the developing world, using a common questionnaire over a long time period. It relies on the assessments of local experts who are in a position to judge the proportion of the entire population having ‘ready and easy access’ to each contraceptive method. This is regardless of source, so it covers both private and public sectors, and both clinical and non-clinical outlets. Sources include static facilities, social marketing through partially subsidized sales, community-based depots and home delivery, and in some countries contraception is offered at the time of delivery or post-abortion care. Disadvantages include the judgmental nature of ratings by expert observers, though that affords measures on variables not otherwise available.

An alternative approach to exploring the access–use relationship uses data from a sample of facilities to gather information on methods offered, with linkages at some geographic level to contraceptive use as given in household surveys. These can be helpful (see Wang et al., 2012) despite the limitation of dissimilar sampling designs that require aggregation of results at regional or other levels. Wang et al. review a number of other facility-based studies.

Methods and Data Sources

The analyses in this paper come from two sources of information: first, contraceptive use information is taken from the Demographic and Health Survey series (Macro International, 2011) and from the United Nations compilation (UN Population Division, 2011), which provides additional national surveys. Second, information on access to contraception by national populations comes from the 1999, 2004 and 2009 cycles of the National Family Planning Programme Effort studies, each cycle covering more than 80 developing countries. These studies have been reported on extensively (Ross & Smith, 2011); they gather information on each national programme through a standard questionnaire administered to expert observers in each country. These respondents are asked to estimate the proportion of the national population that has ‘ready and easy access’ to each of six contraceptive methods plus safe abortion, along with ratings for eight policy variables, thirteen services variables and three evaluation variables, 31 in all. Additionally, responses are obtained for a set of judgments concerning programme goals, the effect of funding changes, and other items of interest. All large countries are included in each year (China, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Indonesia in Asia, Mexico and Brazil in Latin America, Nigeria in Africa, and nearly all middle-sized countries in each developing region).

Access to contraception is obtained for each widely used ‘modern’ method: male and female sterilization, the IUD, the pill, the injectable and the condom. ‘Traditional methods’ of rhythm and withdrawal are omitted as they do not require services and supplies. The percentage of the whole population judged to have access to each modern method gives the basic data used below. Depending upon the analysis the focus is upon either the individual method or the average across methods.

The access measures are compared with the prevalence measures, i.e. the proportion of married/in union women or couples who are currently using each of the above methods, as obtained in nationally representative surveys. Access and use are the primary variables employed throughout. The access studies are in fixed years (1999, 2004 and 2009), so the household surveys taken closest to those dates are employed for each country.

The selection of methods below uses a variety of approaches to examine the access–use relationship. The basic rationale, as explained above, is that because the available contraceptives are so different from one another and because each one has its own particular set of strengths and shortcomings, each one will attract its own subset of users. Therefore, total use will be greater where more methods are made readily accessible to the general population. Each table or chart below applies a different approach to the nature or closeness of the access–use relationship. While the possibility cannot be excluded of some circularity in the relationship whereby questionnaire respondents who rate access are influenced by some sense of the degree of use in the country, the systematic patterns reported below appear to go well beyond that, differentiating the results beyond a simple overall correlation.

In addition, for some analyses in the paper, sub-Saharan Africa is considered here separately from other regions, and a 1999–2009 time trend is given for access to multiple contraceptive methods.

Results

The results reported below focus first on the average relationships between access and use in each of the years 1999, 2004 and 2009, followed by the regional difference between countries in sub-Saharan Africa and those elsewhere. Then the access–use relationship is examined for each contraceptive method separately as of 2004 (when there are more data from surveys than in 2009). Next, the relative positions of the methods are examined to show the contrasts under low access vs high access. Finally, the degree of access to multiple methods in the same country is examined.

Mean access and mean use

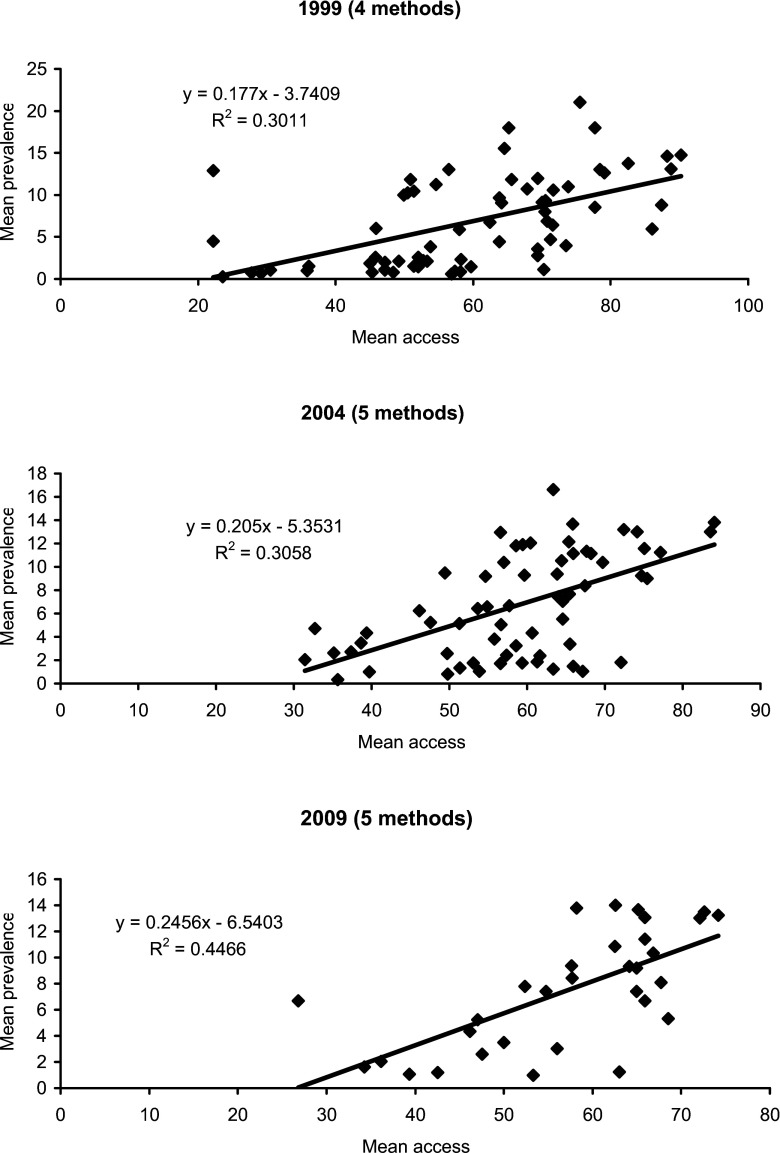

A first way to examine the dependence of contraceptive use upon its access appears in Fig. 1. It compares, for each year, the average access rating with the average rating for the prevalence of use. ‘Mean access’ includes the IUD, pill, female sterilization and condom in 1999, and those methods plus the injectable in 2004 and 2009, when it became more widely available in programmes. The estimates come from the Family Planning Programme Effort scores mentioned above. ‘Mean prevalence’ denotes the percentage of married/in union women using those methods, taken from national surveys conducted within one to three years of the date of the effort score.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of mean contraceptive access rating with mean prevalence rating, by year.

For 1999 and 2004 there are 67 and 63 countries respectively that have information on both mean prevalence and mean access; for 2009 there are only 32 due to lack of prevalence surveys on or near 2009 since few surveys were available for exactly 2009 or in 2010–2011. In each of the three years 1999 to 2009 the relationship is consistently positive; in fact the relationship becomes stronger with time. Not only do the correlations between mean access and mean use progress from 0.30 to 0.31 to 0.45, the slopes also sharpen from 0.18 to 0.21 to 0.25, meaning that in 2009, a 10-point increase in the mean access score translated into an increase of 2.5% in mean contraceptive use.

The earlier analysis by Ross et al. (2002) found very similar results for patterns in 1982, 1989 and 1994, as well as 1999, for the same contraceptive methods except the injectable, for which separate data were not gathered in those years. Thus the positive relationship between access to contraception and contraceptive use has persisted over nearly three decades. As access ratings across various methods have improved to give more options to more couples, total use has increased.

Regional contrasts in access and use

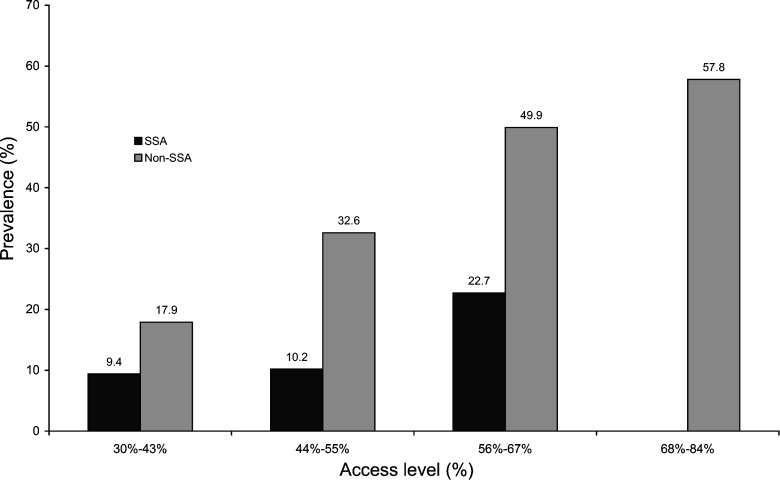

An important regional difference exists in the overall averages, illustrated by the 2004 data in Fig. 2. It compares the 30 sub-Saharan Africa countries with the 35 countries in other regions. The sub-Saharan Africa countries are clustered toward the left of the figure, at lower access levels; in fact none falls into the highest access range of 68% and above (to 84%, the highest recorded). Moreover, at each of the other three levels of access, the average prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa is well below that of the other countries. Francophone countries are especially disadvantaged: prevalence is constrained at a low level even though access varies appreciably. Among all 30 sub-Saharan countries, 23 are below 20% prevalence, and eleven Francophone countries are below 10% prevalence (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Relationship of contraceptive prevalence to access, by region, 2004.

Overall prevalence rises rather sharply across the access range shown in both groups of countries: from 9.4% to 22.7% in sub-Saharan Africa compared with an increase from 17.9% to 57.8% elsewhere. Over time, a shift of more African countries toward higher access levels should bring with it higher prevalence levels as well, although additional research is needed to examine the reasons for the difference in mean contraceptive prevalence at the same level of access in sub-Saharan Africa compared with other countries. It is likely that other programmatic or demand-side factors are driving the differences.

Access–use by method

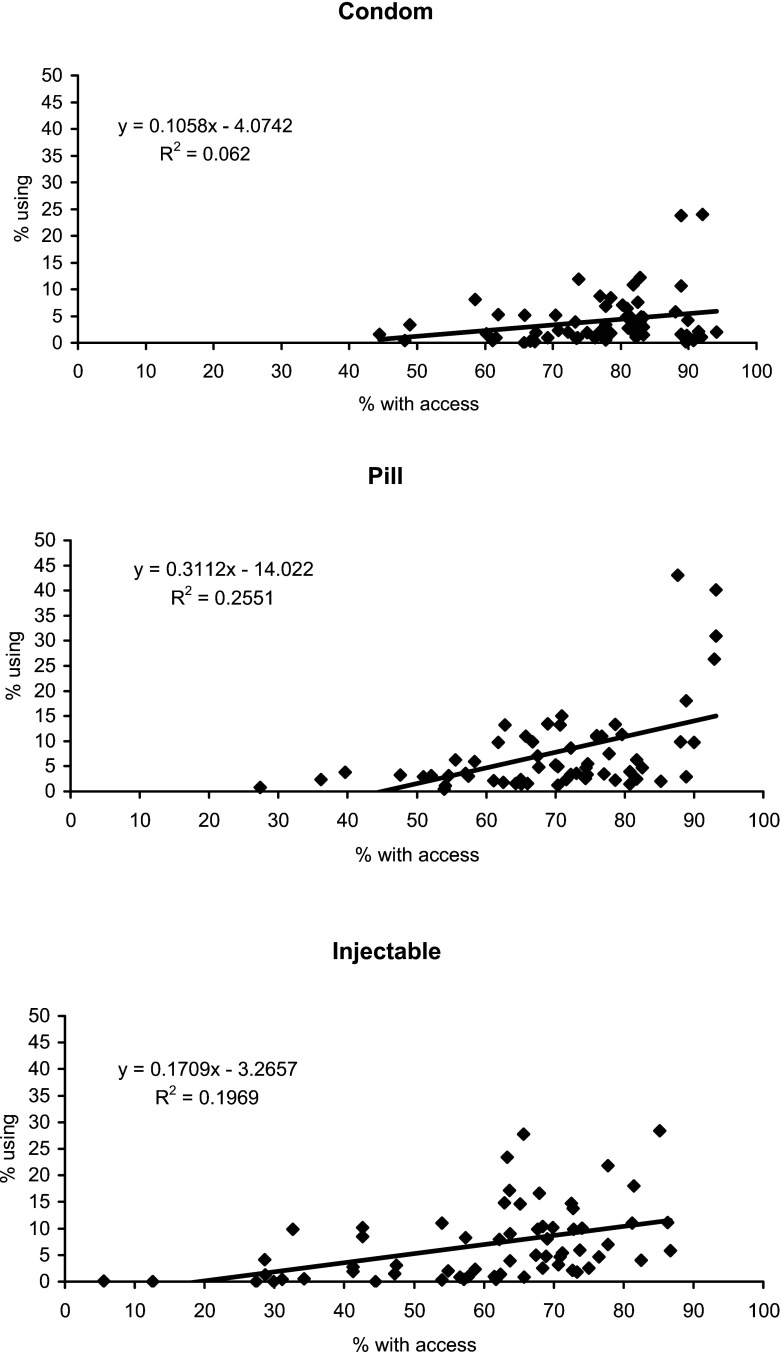

An additional perspective on the relationship between access and use focuses on the individual contraceptive methods (Fig. 3), using data from 2004. Note that Fig. 3 keeps 50% as the maximum for use (the y-axis in each chart) in order to highlight the range differences among methods. The access–use relationship is positive for each method, but with significant variations. Three methods – the pill, IUD, and female sterilization – show substantial slopes, between 0.31 and 0.39 (the latter meaning that a 10-point increase in access yields an increase of 3.9% using the method). However, the slopes are weaker for the injectable and the condom (see Table 1). The condom may be a special case since the data pertain to married/in union women, for contraceptive purposes only, and condom use would be greater by including use for HIV prevention and among unmarried women. It is possible that reported condom use for contraception is depressed, not only due to respondent shyness to mention it, but also due to some stigma from its association with HIV.

Fig. 3.

Relationship of contraceptive prevalence to access, by method, 2004.

Fig. 3.

Continued

Table 1.

Slope of access–use relationship for different contraceptive methods, 2004

| Slope | R 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Pill | 0.31 | 0.26 |

| IUD | 0.39 | 0.44 |

| Female sterilization | 0.36 | 0.41 |

| Injectable | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| Condom | 0.11 | 0.06 |

The IUD and female sterilization show high correlation values, indicating that use follows access more closely than with the other methods. However, use levels are universally far below access levels, which is as expected. A particular method may be readily available for many women or couples but they prefer a different method or are not using anything at all. Access is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the use of a method.

For all five methods some countries are outliers, high and to the right. This reflects the marked geographic pattern that characterizes programmes and the methods that are both accessible and popular within them. For the condom, Ukraine and Jamaica show the highest values; otherwise the cluster of points rests lower for percentage using than for any other method. The injectable takes high values in east and southern Africa, in some Latin American countries, and in Indonesia and Thailand; but it is a minor method elsewhere (Ross & Agwanda, 2012). The IUD is nearly absent in sub-Saharan Africa but is prominent in the Middle East and North Africa. Female sterilization is absent in the Middle East and North Africa but is important in Latin America. Condom access is rated quite high nearly everywhere but the actual use levels are low.

Dependence of prevalence upon the level and variability of access

Ideally, access should be good for several methods, at a uniformly high level, so that the variability among methods is low. Then total prevalence of use should be high. But variability can also be low when access is uniformly poor for all methods; in that case prevalence should be low. Therefore, it is important to know both the level and the variability of access, and to relate those to prevalence.

Table 2 examines the prevalence of use as the sum across all methods, shown by country. Sixty-four countries are classified according to both level and variability of access in 2004. Cutting points in the table cast about half of all countries into each column and about half into each row. Variability is measured by the standard deviation across access ratings for the various methods, and the access level, either low or high, uses the median rating. Countries are grouped into four cells: low access and low variability (upper left cell), low access and high variability (upper right cell), high access and low variability (lower left cell), and high access and high variability (lower right cell). Most countries fall into the upper right and lower left cells, for either low access with high variability or high access with low variability. Within each cell, the countries are listed in order of their total prevalence of use (exclusive of traditional methods).

Table 2.

Contraceptive prevalence for 64 countries classified by high/low access and variability, 2004

| Variability of access | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access level | Low | High | ||||||

| Low | Congo, DR | 5.8 | Chad | 1.6 | Madagascar | 16.3 | ||

| Liberia | 10.3 | Guinea | 4.0 | Haiti | 21.7 | |||

| Yemen | 13.1 | Niger | 4.9 | Armenia | 23.6 | |||

| Uganda | 17.4 | Mauritania | 5.2 | Cambodia | 25.3 | |||

| Tanzania | 19.0 | Nigeria | 6.6 | Georgia | 25.7 | |||

| Philippines | 32.8 | Burundi | 8.5 | Zambia | 26.2 | |||

| Guatemala | 33.4 | Rwanda | 8.8 | Myanmar | 31.3 | |||

| Indonesia | 51.8 | Gambia | 8.9 | Bolivia | 32.2 | |||

| Uzbekistan | 59.0 | Cameroon | 12.1 | Peru | 46.0 | |||

| Dominican Republic | 64.7 | Azerbaijan | 12.9 | India | 47.4 | |||

| Ethiopia | 13.6 | |||||||

| Median | 25.9 | Median | 13.6 | |||||

| High | Mozambique | 11.8 | Honduras | 55.8 | Benin | 5.3 | ||

| Ghana | 16.8 | Viet Nam | 56.1 | Mali | 6.2 | |||

| Pakistan | 21.7 | Ecuador | 57.8 | Burkina Faso | 7.3 | |||

| Lesotho | 35.2 | Paraguay | 60.3 | Togo | 9.0 | |||

| Jordan | 38.3 | El Salvador | 60.8 | Senegal | 9.3 | |||

| Turkey | 41.8 | Colombia | 65.0 | Malawi | 27.7 | |||

| Turkmenistan | 45.0 | Mexico | 65.1 | Nepal | 37.1 | |||

| Bangladesh | 46.3 | Nicaragua | 68.4 | Morocco | 51.8 | |||

| Swaziland | 46.5 | Thailand | 69.1 | Namibia | 52.7 | |||

| Ukraine | 46.9 | China | 83.1 | Egypt | 55.7 | |||

| Zimbabwe | 56.6 | |||||||

| South Africa | 59.6 | |||||||

| Jamaica | 66.0 | |||||||

| Median | 51.4 | Median | 37.1 | |||||

As expected, median contraceptive prevalence is highest where access is high, at 51% and 37% in the two cells on the bottom row (prevalence is 46% for the two cells merged). Contraceptive prevalence is much lower where access is low, in the top row, at 26% and 14% (17% merged).

Similarly, prevalence is considerably higher where variability is low indicating fairly uniform levels of access among the several methods. That might offer greater choice among methods; however, uniformity across the methods can occur with either low or high access levels. Given low variability (two left cells), greater access makes a large difference, doubling the prevalence level: 26% compared with 51% (43% merged). The relationship holds in the second column for high variability: prevalence averages a very low 14% if access is poor with more than a doubling to 37% where access is good (23% merged). Overall, prevalence ranges from only 14% using to about half (51%) using, depending upon the blend between average access to contraceptive methods and average variability among the five methods. Clearly the best combination is good access with an even-handed treatment of the several contraceptive options.

The pattern of differences across the five methods affects the means in some cases. Why, for example, is Indonesia in the low access row while Mozambique is in the high access row? Actually, both lie close to the 59% cut-off rule for mean access that creates the two rows, with Indonesia at 57% and Mozambique at 62%. Both countries have low ratings for access to female sterilization, and high ratings for access to the pill and injectable, but Mozambique is considerably higher for the condom, probably due to the AIDS programme in the country. Pakistan barely enters the high access group, at only 58% average access, and measurement error can be present in particular country ratings.

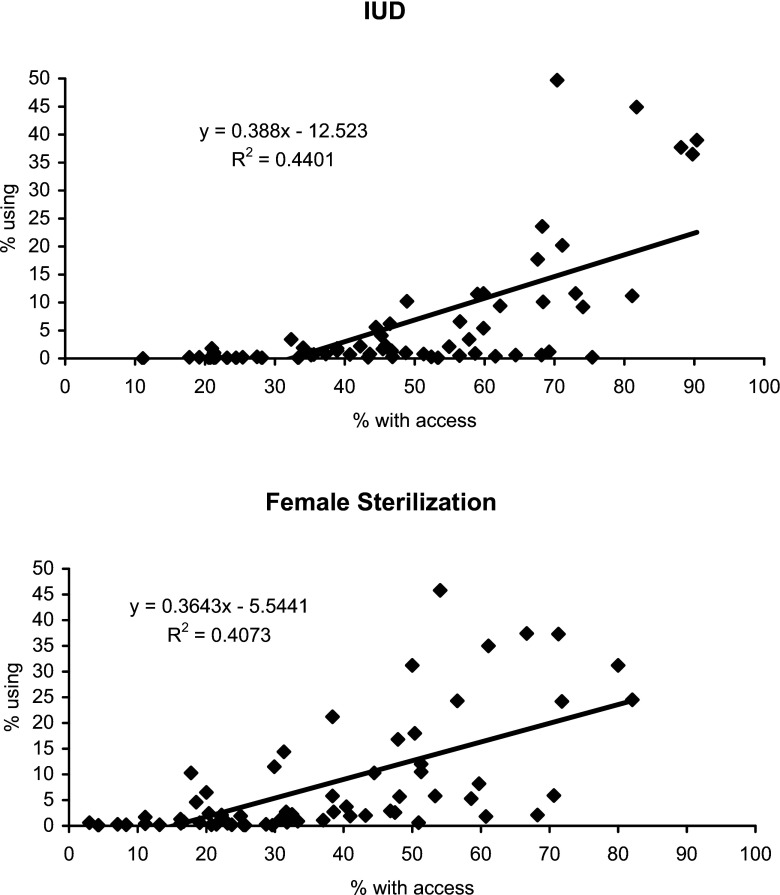

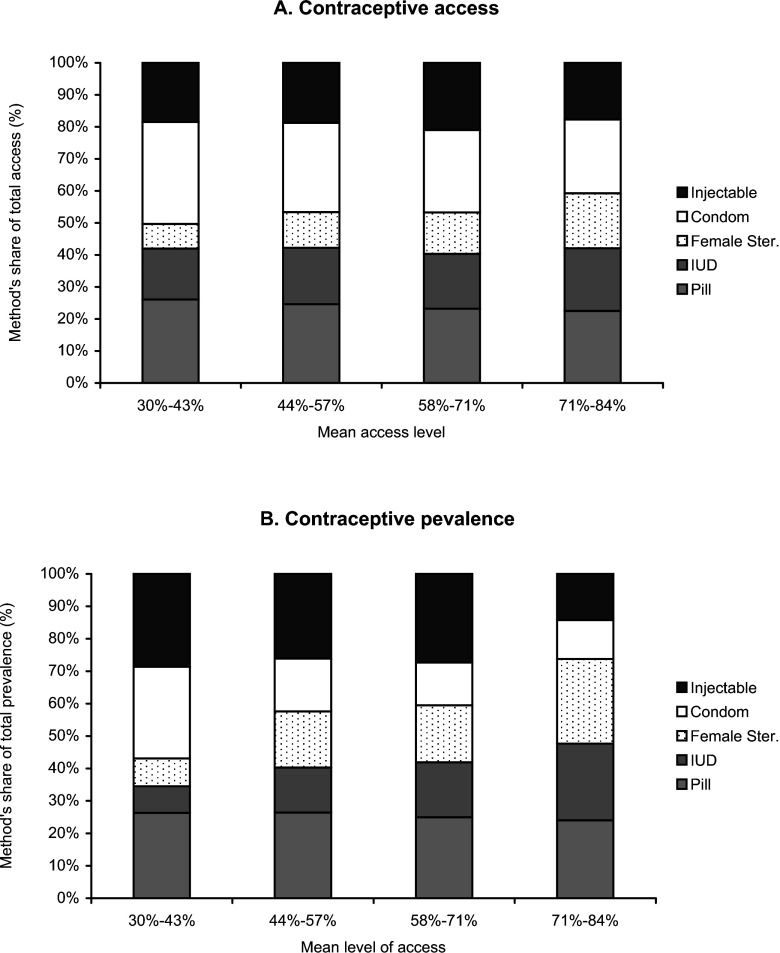

Comparative positions of methods as access improves

A different approach to understanding the comparative pictures of contraceptive access and contraceptive prevalence for the various contraceptive methods is shown in Fig. 4, again for 2004. Figure 4A shows in each bar the distribution of access for each of the five methods. As overall access improves (along the bottom axis), the relative positions of the various methods shift. At the left, where average access is limited to 43% or less of the population, condom access is best, with pills second. At the other extreme, where average access is 71% or higher, the balance among methods is better: access to condoms is relatively lower while access to female sterilization and the IUD is relatively higher. Over past decades, actual access for all methods has in fact been improving; meanwhile their relative positions have been changing, toward a closer balance of choices offered to the population.

Fig. 4.

Percentage distribution of contraceptive access (A) and prevalence (B), by method, according to mean level of access, 2004.

Figure 4B goes farther to show in each bar the distribution of prevalence for the five methods. Again, that distribution changes as access improves along the x-axis. These shifts are more marked than those shown for access in Fig. 4A: the relative position of condom use declines considerably while that of female sterilization increases quite sharply. Use of the IUD increases regularly along the access continuum. The pill declines very little. In general the injectable is about as important as the pill, except in countries with the highest overall access.

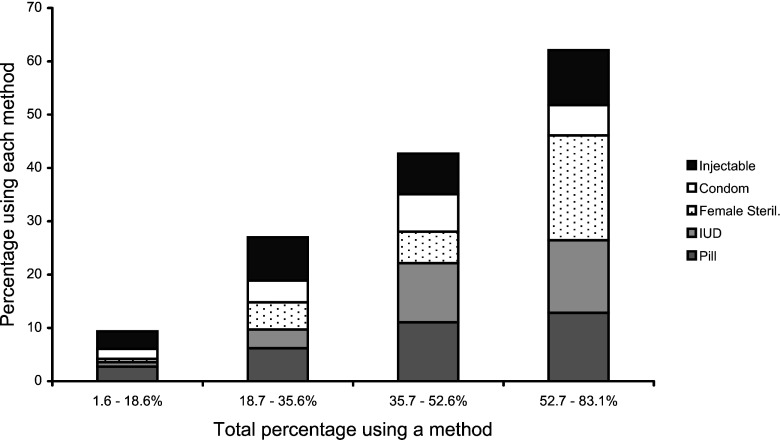

All this pertains only to shares, not absolute levels of use. While the condom loses share, the original data show an increase in the absolute percentage using it. In fact, use of every method shown rises as total prevalence of use rises. Figure 5 displays this; it divides the range of total use into four equal intervals on the x-axis, with each bar showing the percentage of married/in union women using each method. (The rightmost range ends at 83.1% but that is for China, an outlier. The other countries go only to 69.1%.) The condom increases until the highest range. Sterilization gains the most, and each of the other methods gains at each level, including the injectable at the top.

Fig. 5.

Increase in use of each contraceptive method as total use increases.

The principal message in Fig. 4 is the emergence of a better balance among the five methods as access improves, with a corresponding improvement in the balance for actual use of the methods. That balance is consistent with a wider choice for clients. The data show the manner in which the pool of users tends to move toward a variety of methods as more options are made available. Again, note that the figures show only the relative positions of contraceptive use as access improves; the absolute level of use for each method generally rises with better access.

Access to multiple methods

The focus on personal choice among contraceptive options requires attention to combinations of methods, not just to any single method. It is possible from the access data to examine access to multiple methods in various combinations (Table 3). For this analysis, the rule is that at least half of the population must have access to a method for it to be considered available in any of the combinations shown.

Table 3.

Percentage of population with access to multiple contraceptive methods a

| 1999 | 2004 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condom | 90.8 | 96.4 | 98.8 |

| Pill | 83.9 | 90.4 | 91.4 |

| IUD | 48.3 | 45.8 | 45.7 |

| Female sterilization | 42.5 | 27.7 | 30.9 |

| Male sterilization | 17.2 | 4.8 | 7.4 |

| Injectable | na | 67.5 | 69.1 |

| Pill, IUD | 47.1 | 42.2 | 44.4 |

| Pill, female sterilization | 42.5 | 25.3 | 30.9 |

| IUD, female sterilization | 33.3 | 18.1 | 24.7 |

| Pill, IUD, female sterilization | 33.3 | 15.7 | 24.7 |

| Pill, IUD, female sterilization, condom | 32.2 | 15.7 | 24.7 |

| At least one long-term method | 57.5 | 55.4 | 53.1 |

| At least one short-term method | 93.1 | 97.6 | 98.8 |

| At least one long-term & one short-term method | 57.5 | 55.4 | 53.1 |

To protect the time trend the injectable is not included in the combinations.

Access rule: 50% or more of the population has access to the method.

The first panel in the table sets a baseline; it shows the limiting effect of each method when included in any combination below. For example, because female sterilization was available in only 31% of countries, no combination including it below can rise above 31%. A consistency across the years is evident: in the first panel the rank order of methods does not change annually. In 1999 the condom comes first, then the pill, then the IUD, then female sterilization, and finally male sterilization. In 2004 and 2009 the injectable was included and it took third place. The injectable is excluded in the combinations that follow to maintain the time trend for a full decade. Male sterilization is also excluded, since its low value would force a low value on any combination involving it.

The middle panel reveals the ceiling effects from the ratings in the top panel. Any combination with the IUD can rate at most 46% to 48%, which is the case for its combination with the pill: the values of 42% to 47% are slightly below those of the IUD alone since the pill, while widely available, is lacking in some countries. The last three rows in the middle panel are quite similar and take the lowest values due to the double constraints of female sterilization and the IUD.

Finally, the bottom panel permits more flexibility: the first row allows for a country to have either the IUD or female sterilization, and the second row permits either the pill or the condom to qualify. The last row reflects the limit due to the inclusion of the first row rules.

These results make it clear that many countries fall short in offering multiple methods. Dual long-term methods are not common. For short-term methods, most countries offer at least the pill or condom or both, and that high figure would be yet higher if the injectable were included as well. However the rule is ‘at least one’, and where it is only one the choice of options is unsatisfactory for many potential users. Similarly, where ‘at least one’ short-term method and one long-term method means only one of each, that is inadequate for the general population.

Discussion

The findings in this report extend and expand those in the analysis from ten years ago that used similar methods and data sources. Putting the two together gives a 27-year span of experience, from 1982 to 2009, for the dependence of contraceptive use upon the degree of access to a range of contraceptive methods. There is a positive access–use relationship in each of the six years examined (1982, 1989, 1994, 1999, 2004 and 2009) based first upon the mean levels of both access and use. Next, this result is reinforced with breakdowns of the means across ranges of both access and use. The relationship is also positive for each contraceptive method taken separately. In addition, prevalence of use is highest in countries where both the mean level for access is high and the variability among methods is low, which together provide a wide choice of options to the population. Further, where the overall level of access is high, methods are in better balance in their relative accessibility and relative use.

However, the absolute levels of access show that most countries have far to go in actually offering multiple methods for both long-term and short-term alternatives. In practice, few countries have come close to making even four methods fully available to everyone. Whatever the reasons, there is a sharp selectivity in which methods are present. Access varies not only by method, but by local areas within each country and by source of supply. Not everyone in a country has the same access to each method and to each source. The extent of these disparities is not well documented and deserves much more attention, especially in individual country studies.

Various new methods that have been tested have failed for a variety of reasons to win a substantial following after pilot trials, so the experience of the past decades is that most use is of just six modern methods: the pill, injectable, IUD, male and female sterilization and the condom (leaving traditional methods aside). Every country has been selective within that group, concentrating on as few as one or two methods. Others have a balance among three to four methods, but that is uncommon. New methods face challenges in being scaled up to ensure wide access for full national implementation.

In general, because each method has its own particular blend of advantages and weaknesses it finds its own subgroup of users, therefore total use increases with the number of methods made available to the population at large. A wider choice of options leads to greater overall use and to easier avoidance of unintended pregnancies. Because none of the current methods can serve all needs among all users a variety of methods fits a wider variety of needs.

Inevitably the access level will always be higher than the use level for a method, since some persons prefer to use a different method or no method. A partial exception to this is sterilization since the use level cumulates from many past years, in each of which access may have been low. Finally, prevalence of any method is not a function only of access. Given reasonable access to a method, its use will fall below the access level and will depend upon competing methods, provider influences, personal likes and dislikes among potential users, and the experience of past users pro and con regarding the method's appeal vs such negatives as side-effects, health concerns and cost. The analyses here pertain to a limit on what prevalence can become, based on the public's opportunity to obtain the methods. Raising those limits can both enhance personal options for protection against unplanned pregnancy, and reduce unmet need in the population at large. The results here support policy and programme decisions to make a wider range of contraceptive methods available and to extend access to them throughout the country.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Health Policy Project under Co-operative Agreement No. AID-OAA-A-10-00067, beginning 30th September 2010. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of USAID or the US government.

References

- Bulatao R. A., Palmore A. & Ward S. E. (eds) (1989) Choosing a Contraceptive: Method Choice in Asia and the United States. Westview Press [Google Scholar]

- Chamratrithirong A. & Kamnuansilpa P. (1984) How family planning availability affects contraceptive use: the case of Thailand In Ross J. & McNamara R. (eds) Survey Analysis for the Guidance of Family Planning Programs. Center for Population and Family Health, Columbia University, New York, pp. 219–235 [Google Scholar]

- Chao D. N. W., Gupta Y. P., Stover J. & Talwar P. P. (1994) Using age-specific appropriate method-mix strategy to achieve replacement level fertility in India: a model for policy analysis. Demography India 23(1 & 2), 157–166 [Google Scholar]

- Choe M. K. & Bulatao R. A. (1992) Defining an appropriate contraceptive method mix to meet fertility preferences. Presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America.

- Darroch J. E., Sedgh G. & Ball H. (2011) Contraceptive Technologies: Responding to Women's Needs. Guttmacher Institute, New York, p. 51 [Google Scholar]

- Freedman R. & Berelson B. (1976) The record of family planning programs. Studies in Family Planning 7(1), 1–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A. K. (1989) Fertility reduction and the quality of family planning services. Studies in Family Planning 20(1), 1–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E. F. (1984) The Availability of Contraceptive Services. WFS Comparative Studies No. 37, International Statistical Institute [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. L. & Ross J. (2007) The Korean breakthrough In Robinson W. & Ross J. (eds) The Global Family Planning Revolution: Three Decades of Population Policies and Programs. World Bank, Washington DC, Chapter 11. [Google Scholar]

- Lapham R. J. & Mauldin W. P. (1985) Contraceptive prevalence: the influence of organized family planning programs. Studies in Family Planning 16(3), 117–137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch F. & Aganon V. (1974) The Clinic Location Site Study. Research Note No. 13, Commission on Population, Rizal, Philippines [Google Scholar]

- Macro International (2011) DHS Series Stat Complier. URL: http://www.statcompiler.com/

- Potter R. G. (1971) Inadequacy of a one-method family planning program. Studies in Family Planning 2(1), 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson W. & El-Zanaty F. H. (2007) The evolution of population policies and programs in the Arab Republic of Egypt In Robinson W. & Ross J. (eds) The Global Family Planning Revolution: Three Decades of Population Policies and Programs. World Bank, Washington DC, Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson W. & Ross J. (eds) (2007) The Global Family Planning Revolution: Three Decades of Population Policies and Programs. World Bank, Washington DC [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez G. (1978) Family planning availability and contraceptive prevalence. International Family Planning Perspectives 4(4), 100–115 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield A. G. & Min C. J. (2007) The emergence of Thailand's national family planning program In Robinson W. & Ross J. (eds) The Global Family Planning Revolution: Three Decades of Population Policies and Programs. World Bank, Washington, DC, Chapter 14. [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. & Agwanda A. T. (2012) Increased use of injectable contraception in sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health 16(4). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J., Hardee K., Mumford E. & Eid S. (2002) Contraceptive method choice in developing countries. International Family Planning Perspectives 28(1), 32–40 [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. & Smith E. (2011) Trends in national family planning programs: 1999, 2004, and 2009. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 37(3), 125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T. M., Bertrand J. T., Rice J. & Shelton J. D. (2006) Skewed contraceptive method mix: why it happens, why it matters. Journal of Biosocial Science 38(4), 501–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui A. O. (1982) Contraceptive availability and family limitation in Mexico and Rural Korea. International Family Planning Perspectives 8(1), 8–18 [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Division (2011) World Contraceptive Use 2010. POP/DB/CP/Rev2010; URL: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/unpp/panel_population.htm [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Wang S., Pullum T. & Ametepi P. (2012) How family planning supply and the service environment affect contraceptive use: findings from four East African countries. DHS Analytical Studies No. 26 ICF International, Calverton, Maryland, USA [Google Scholar]