Abstract

Skeletal muscle is one of the most sensitive tissues to mechanical loading, and unloading inhibits the regeneration potential of skeletal muscle after injury. This study was designed to elucidate the specific effects of unloading stress on the function of immunocytes during muscle regeneration after injury. We examined immunocyte infiltration and muscle regeneration in cardiotoxin (CTX)-injected soleus muscles of tail-suspended (TS) mice. In CTX-injected TS mice, the cross-sectional area of regenerating myofibers was smaller than that of weight-bearing (WB) mice, indicating that unloading delays muscle regeneration following CTX-induced skeletal muscle damage. Delayed infiltration of macrophages into the injured skeletal muscle was observed in CTX-injected TS mice. Neutrophils and macrophages in CTX-injected TS muscle were presented over a longer period at the injury sites compared with those in CTX-injected WB muscle. Disturbance of activation and differentiation of satellite cells was also observed in CTX-injected TS mice. Further analysis showed that the macrophages in soleus muscles were mainly Ly-6C-positive proinflammatory macrophages, with high expression of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β, indicating that unloading causes preferential accumulation and persistence of proinflammatory macrophages in the injured muscle. The phagocytic and myotube formation properties of macrophages from CTX-injected TS skeletal muscle were suppressed compared with those from CTX-injected WB skeletal muscle. We concluded that the disturbed muscle regeneration under unloading is due to impaired macrophage function, inhibition of satellite cell activation, and their cooperation.

Keywords: macrophages, muscle regeneration, mice, satellite cells, tail suspension

skeletal muscle has powerful regenerative ability. Several studies have indicated that unloading stress under certain conditions, such as spaceflight and bed rest, inhibits the regenerative potential of skeletal muscles in mice (16, 18, 35). Some of these studies suggested that the decreased number and disturbed fusion ability of satellite cells during unloading contributes to such delayed muscle regeneration, implicating the role of satellite cell activation in muscle regeneration during unloading stress.

Infiltrating immune cells are also important in the regulation of muscle regeneration after injury. Massive numbers of immunocytes, such as neutrophils and macrophages, accumulate at the site of skeletal muscle injury prior to satellite cell activation (14, 24, 26). Neutrophils are the first to infiltrate the injured muscle, followed by macrophages, which in turn induce phagocytosis of necrotic myofibers. Macrophages also activate satellite cells, which fuse with one another or with preexisting muscle fibers to form regenerating myofibers (10, 12, 32). In particular, the switch from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory macrophages is important for support and regulation of muscle regeneration (1, 6).

The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of muscle unloading stress on the recruitment and function of immune cells before the activation of satellite cells. For this purpose, we examined neutrophils and macrophages that infiltrate into skeletal muscle after cardiotoxin (CTX) injection. Under unloading conditions, infiltrating neutrophils remained at the site of injury for 1 wk. Furthermore, macrophage infiltration into the site was delayed. Surprisingly, almost all the delayed macrophages during unloading were of the proinflammatory type, indicating prolonged inflammation after the injection. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence to suggest that unloading prolongs the inflammatory process in skeletal muscle after injury. Such findings implicate the regulation of proinflammatory macrophages as a therapeutic target in stimulating the regeneration of injured skeletal muscle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tail suspension and CTX injection. C57BL/6 mice (Japan SLC, Shizuoka, Japan) were housed at 23 ± 2°C on a 12:12-h light/dark cycle with free access to the MF laboratory animal diet (Oriental Yeast, Tokyo, Japan) and water under specific pathogen-free conditions. The mice were divided into four groups (n = 45 per each following groups): CTX-injected tail suspension (TS) group, vehicle-injected TS group, CTX-injected weight bearing (WB) group, and vehicle-injected WB group. TS was performed using the method described previously (13). Briefly, a piece of tape was attached to both the tail and a swivel tied to a horizontal bar at the top of cage. On day 0, CTX at 10 μM in 10 μl of saline (Latoxan, Rosans, France) or vehicle was injected into the soleus muscles. Each five mice in four groups were euthanized on the indicated days, day 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 14, after CTX or vehicle injection.

The Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at The University of Tokushima School of Medicine approved all study protocols, which were conducted according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at The University of Tokushima.

Histological analysis.

The isolated soleus muscles were immediately frozen in chilled isopentane and liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis. Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (22), using the following primary antibodies: anti-Gr-1 (a marker of neutrophils) antibody (Serotec, Oxford, UK), anti-F4/80 (a marker of macrophages) antibody (Serotec), anti-Ly-6C antibody (BMA Biomedicals, Augst, Switzerland), anti-CD31 antibody (BMA Biomedicals), anti-MyoD antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and anti-embryonic myosin heavy chain (MyHC) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Sections were also viewed after hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining. For quantitative analysis, we counted the number of cells or necrotic fibers in 45 high-power fields per 15 sections in five mice/group. We used the BIOREVO BZ-9000 (Keyence, Osaka, Japan) to calculate the cross-sectional area (CSA) of each myofiber. The distribution of fiber sizes was reported as a percentage of myofibers per visual field.

Preparation of primary macrophages and myoblasts.

Primary macrophages and myoblasts were prepared from skeletal muscles, according to the method of Ojima et al. (23). For preparation of primary macrophages, soleus muscles of CTX-injected TS or WB mice (C57BL/6 mice, 10 wk old) were removed on day 3 and day 2, respectively, after CTX injection. We also isolated whole hindlimb skeletal muscles of C57BL/6 mice (6–8 wk old) for preparation of primary myoblasts. Briefly, skeletal muscles were harvested immediately following euthanasia and minced in sterile, ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Tissue was digested in PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.2% type II collagenase (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ). Following digestion, tissues were filtered through 100-μm nitrex mesh and subsequently through 40-μm nitrex mesh. Filtrates were spun at 800 g for 5 min, and then the pellets were resuspended in 0.17 M Tris-buffer solution, pH 7.65, containing 0.8% NH4Cl for 30 s. After washing with PBS, these cells were seeded on dishes and cultured with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C under 5% CO2-95% air for 2 h. Adherent and nonadherent cells were used as primary macrophages and myoblasts, respectively.

Coculture of primary macrophages and primary myoblasts.

Nonadherent cells (myoblasts) at 3 × 104 cells/well were seeded on collagen (type I)- coated plate (IWAKI Scitech Div., Tokyo, Japan) and further cultured for 2 days with growth medium, consisting of nutriment mixture F-10 ham containing 20% FBS, 2.5 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (Kaken Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, at 37°C under 5% CO2-95% air. Previously isolated macrophages were seeded on these cultured myoblasts at the following ratio: macrophages:primary myoblasts = 3:1. Then these cells were cocultured with differentiation medium for myoblasts (DMEM containing 2% horse serum) for 3 days. Myotube formation was estimated by counting the embryonic MyHC-positive multinuclear myotube. Myotubes are defined to be developing muscle cells or fibers forming a spindlelike shape with more than two centrally located nuclei, indicating that cells were fused. Therefore, we defined skeletal muscle cells with more than two centrally located nuclei as myotubes. We counted such myotubes in 12 high-power fields in four individual dishes, according to the previous report (2), with a slight modification.

Phagocytosis.

Phagocytosis of primary macrophages was quantified at 1 h after incubation with 2 μm fluoresbrite yellow green microspheres (Polyscience, Warrington, PA) as described previously (3). The number of microspheres in F4/80-positive cells was quantified with the BIOREVO BZ-9000 (Keyence). Phagocytic properties of macrophage-like RAW264.7 cells subjected to 3-dimensional (3D) clinorotation for 24 h were also measured in the similar way. RAW264.7 cells were subjected to 3D clinorotation in an apparatus, portable microgravity simulator-VI (Advanced Engineering Service, Tsukuba, Japan), as described previously (11). Briefly, plates containing RAW264.7 cells were filled with DMEM in the presence of 10% FBS. They were rotated with two axes on the microgravity simulator at 37°C in a 5% CO2 chamber. The rate and cycle of rotation were controlled by the computer to randomize the gravity vector both in magnitude and in direction, and then the dynamic stimulation of gravity to cell was canceled in any direction (11).

Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Total RNA was subjected to real-time RT-PCR with SYBR Green dye using an ABI7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), as described previously (31). Table 1 lists the oligonucleotide primers used for real-time RT-PCR.

Table 1.

Primers for real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

| Target Gene | Sequence | Length, bp |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | ||

| S | 5′-ATGGCCTCCCTCTCATCAGTT-3′ | 78 |

| AS | 5′-ACAGGCTTGTCACTCGAATTTTG-3′ | |

| IL-1β | ||

| S | 5′-AAGGGCTGCTTCCAAACCTTTGAC-3′ | 100 |

| AS | 5′-ATACTGCCTGCCTGAAGCTCTTGT-3′ | |

| TGF-β | ||

| S | 5′-GACTCTCCACCTGCAAGACCAT-3′ | 101 |

| AS | 5′-GGGACTGGCGAGCCTTAGTT-3′ | |

| IL-10 | ||

| S | 5′-GCTCTTACTGACTGGCATGAG-3′ | 105 |

| AS | 5′-CGCAGCTCTAGGAGCATGTG-3′ | |

| 18 s rRNA | ||

| S | 5′-GCAATTATTCCCCATGAACG-3′ | 68 |

| AS | 5′-GGGACTTAATCAACGCAAGC-3′ | |

| MAFbx/ Atrogin-1 | ||

| S | 5′-CCCAATGAGTAGGCTGGAGA-3′ | 100 |

| AS | 5′-GGCAGAGTTTCTTCCACAGC-3′ | |

| MuRF-1 | ||

| S | 5′-ACGAGAAGAAGAGCGAGCTG-3′ | 179 |

| AS | 5′-CTTGGCACTTGAGAGGAAGG-3′ | |

| GAPDH | ||

| S | 5′-CGTGTTCCTACCCCCAATGT-3′ | 74 |

| AS | 5′-ATGTCATCATACTTGGCAGGTTTCT-3′ |

AS, antisense primer; S, sense primer; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; IL-10, interleukin-10; 18 s rRNA, 18 s ribosomal RNA; MAFbx/Atrogin-1, muscle atrophy F-box/atrogin-1; MuRF-1, muscle specific ring finger protein-1; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Statistical analysis.

All data were statistically evaluated by ANOVA using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (release 6.1; SPSS Japan) and expressed as means ± SD. Differences between groups were analyzed with Duncan's multiple range test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Disturbance of muscle regeneration in tail-suspended mice.

We performed histochemical analysis of soleus muscles of TS and WB mice. On day 14 after CTX injection into the soleus muscle, the myofibers contained central nuclei in both groups, indicating they were regenerated myofibers (Fig. 1A). No myofibers with central nuclei were observed in the vehicle-injected soleus. The CSA of the regenerating myofibers in CTX-injected TS mice was smaller than that of the CTX-injected WB mice (Fig. 1A). The size distribution of myofibers in soleus muscle also indicated that TS decreased myofibers with CSA > 900 μm2 and increased those with CSA of 100–500 μm2 compared with CSA of the myofibers of CTX and WB mice (Fig. 1B). These findings indicate that TS results in disturbance of muscle regeneration.

Fig. 1.

Histological analysis of muscle regeneration. A: representative sections (8-μm thickness) from soleus muscles of weight-bearing (WB) and tail suspension (TS) mice on day 14 after cardiotoxin (CTX) or vehicle injection were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E). Arrows indicate the centralized nuclei. We observed 45 high-power fields per 15 sections in 5 mice/group in an experiment. Scale bar = 100 μm. B: calculated cross-sectional area (CSA) of myofibers in 45 high-power fields per 15 sections in 5 mice/group are expressed as means ± SD.

We next examined the time-dependent histological changes in soleus muscles of TS and WB mice after vehicle or CTX injection. By day 1, CTX-injected WB mice showed necrotic myofibers with accumulation of mononuclear cells in the injured muscles (Fig. 2A). The accumulation of mononuclear cells reached a peak level on day 3, before gradually diminishing in their number. The infiltration of mononuclear cells was followed by the appearance of regenerating myofibers with central nuclei on day 7. Regeneration in CTX-injected WB mice was completed on day 14. In contrast, CTX-injected TS mice showed delay of infiltration of mononuclear cells into soleus muscles (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, necrotic fibers remained in soleus muscles of CTX-injected TS mice from days 3 to 7 after the injection, while necrotic fibers were scarce even by day 3 in CTX-injected WB mice (Fig. 2B). Regenerating myofibers with central nuclei appeared around day 14 in CTX-injected TS mice, and the myofiber CSA was smaller than that of CTX-injected WB mice (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Time-dependent histological changes in soleus muscle after CTX injection. A: H and E-stained representative sections (8-μm thickness) of soleus muscles of WB and TS mice obtained at the indicated time points after injection of CTX or vehicle. Scale bar = 100 μm. B: the number of necrotic myofibers in 45 high-power fields per 15 sections in 5 mice per time point per group were counted and expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle injection, #P < 0.05 compared with CTX-injected WB mice.

Effect of unloading on recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages into damaged muscle.

To identify the infiltrated mononuclear cells, we performed immunohistochemistry using an antibody against neutrophils (Gr-1) and macrophage (F4/80) marker proteins. In CTX-injected WB mice, Gr-1-positive neutrophils first appeared in the injured muscle by 6 h after CTX injection and were still noted on day 2 (Fig. 3, A and B). CTX-injected TS mice showed a similar time course of initial neutrophil infiltration, but these neutrophils were still noted in soleus muscles at 1 wk (Fig. 3, A and B). F4/80-positive macrophages infiltrated into soleus muscles on day 2 after the injection and reached a peak on day 3 in CTX-injected WB mice (Fig. 3, C and D), before gradually decreasing in number to zero on day 7. The soleus muscles of CTX-injected TS mice first showed F4/80-positive macrophages on day 3, and these cells were still present in large numbers even on day 7 (Fig. 3, C and D).

Fig. 3.

Identification of infiltrated cells into injured muscles. A and C: representative sections (8-μm thickness) from soleus muscles of WB and TS mice obtained at the indicated time points after CTX or vehicle injection were immunostained with an anti-Gr-1 (green) antibody and Hoechst 33342 (blue) (A), or an anti-F4/80 (green) antibody and Hoechst 33342 (blue) (C). Scale bar = 100 μm. B and D: Gr-1-positive cells (B) and F4/80-positive cells (D) were counted in 45 high-power fields per 15 sections in 5 mice per time point per group and expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle injection, #P < 0.05 compared with CTX-injected WB mice.

Effect of unloading on phenotype of infiltrating macrophages during muscle regeneration.

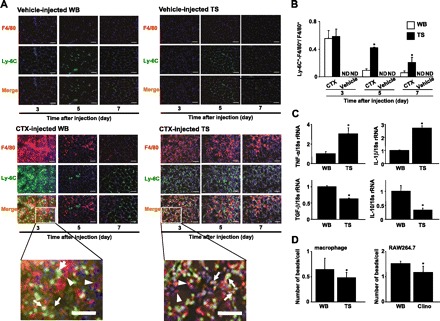

The switch from proinflammatory macrophages (Ly-6C-F4/80 double-positive cells) to anti-inflammatory macrophages (Ly-6C-negative, F4/80-positive cells) is important for support and regulation of muscle regeneration (1, 6). We examined the effect of unloading stress on this switching of infiltrated macrophages. Immunohistochemical analysis using antibodies against F4/80 or Ly-6C revealed that the soleus muscles of CTX-injected WB mice contained proinflammatory (Ly-6C-positive) macrophages on day 3, which disappeared by day 5 (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, Ly-6C-negative macrophages (F4/80-positive) were observed from days 3 to 7. Ly-6C-positive and F4/80-negative cells observed on days 5 and 7 were endothelial cells, since they also stained for CD31 (Fig. 4A and data not shown). Interestingly, CTX-injected TS mice showed sustained numbers of Ly-6C- and F4/80-positive macrophages in soleus muscle compared with CTX-injected WB mice (Fig. 4, A and B), indicating that TS results in preferential accumulation and persistence of proinflammatory macrophages in the injured muscle. No macrophages were noted in the soleus muscle of the vehicle-injected WB and TS mice. Therefore, we did not detect Ly-6C/F4/80 double-positive cells in the soleus muscle (Fig. 4, A and B).

Fig. 4.

Identification of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophages in injured muscles. A: representative sections (8 μm thickness) of soleus muscles of WB and TS mice obtained at the indicated time points after CTX or vehicle injection were immunostained with an anti-Ly-6C (green) antibody, anti-F4/80 (Red) antibody, and Hoechst 33342 (blue). We observed 45 high-power fields per 15 sections in 5 mice per time point per group in an experiment. Scale bar = 50 μm. B: we counted the number of yellow-colored cells (indicated by arrows in bottom panels) and red-colored cells (indicated by arrowheads in bottom panels) as Ly-6C-positive-F4/80 positive macrophages and Ly-6C-negative-F4/80 positive macrophages, respectively, in 45 high-power fields per 15 sections in 5 mice per time point per group. The ratio of yellow-colored cells to total macrophages (yellow-colored cells and red-colored cells) was calculated and is expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with CTX-injected WB mice. C: gene expression levels of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages isolated from muscles of WB and TS mice obtained on day 5 after CTX injection were assessed by real-time reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The fluorescence ratio of target gene cDNA to 18s ribosomal RNA (18s rRNA), a housekeeping gene, was calculated. Data are means ± SD of 3 mice. *P < 0.05 compared with CTX-injected WB mice. D: macrophages were isolated from muscles of WB and TS mice obtained on day 2 or 3 after CTX injection, respectively. RAW264.7 cells were cultured with or without clinorotation (clino) for 24 h. These cells were cultured with 2 μm fluoresbrite yellow green microspheres. One hour later, the number of microspheres in cells was counted in 12 high-power fields in 3 individual dishes and expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with WB conditions.

To examine the macrophage profile in CTX-injected WB and CTX-injected TS mice, we analyzed the gene expressions of cytokines of isolated from CTX-injected soleus muscle on day 5 after injury by real-time RT-PCR. Macrophages from CTX-injected WB mice expressed transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and interleukin (IL)-10 transcripts more strongly than those from CTX-injected TS mice (Fig. 4C). Conversely, macrophages from CTX-injected TS mice expressed tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-1β transcripts more strongly than those from CTX-injected WB mice (Fig. 4C). These results indicate a proinflammatory profile for macrophages from CTX-injected TS mice and anti-inflammatory profile for macrophages from CTX-injected WB mice.

Effect of unloading on phagocytosis.

Phagocytosis of necrotic myofibers is a key factor for the switch from pro-inflammatory profile to anti-inflammatory profile of macrophages (1). In this study, necrotic fibers were persistently seen in the soleus muscle of CTX-injected TS mice (Fig. 2, A and B). Therefore, we examined the effect of unloading stress on phagocytotic ability of macrophages using in vitro phagocytosis assay. The phagocytotic ability of macrophages isolated from CTX-injected TS mice was significantly lower than that of macrophages from CTX-injected WB mice (Fig. 4D). RAW264.7 cells were also cultured with or without 3D-clinorotation and their phagocytosis properties was analyzed. The phagocytotic properties of 3D-clinorotated cells was lower than that of nonrotated cells (Fig. 4D), suggesting that unloading stress suppresses the phagocytotic properties of macrophages.

Stimulatory effects of macrophages on myotube formation.

Anti-inflammatory macrophages are important for effective differentiation and fusion of myoblasts (1). Next, we examined the effect of unloading stress on myofiber formation in the presence of macrophages with impaired phagocytic function. For this purpose, we analyzed the myotube formation using a coculture system of primary myoblasts and macrophages. Coculture with macrophages from CTX-injected WB mice, but not from CTX-injected TS mice, significantly increased myotube formation (Fig. 5, A and B).

Fig. 5.

Stimulatory effects of macrophages on myotube formation. A: macrophages were prepared from soleus muscles of WB and TS mice on day 5 after CTX injection. Primary macrophages (9 × 104 cells/well) were seeded on cultured primary myoblasts (3 × 104 cells/well). These cells were cocultured for 3 days, and cells were immunostained with an anti-embryonic MyHC (green) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Arrows indicate centrally located nuclei. Scale bar = 100 μm. B: myotube formation was estimated by counting the number of embryonic MyHC-positive multinuclear myotube in 12 high-power fields in 4 individual dishes. *P < 0.05 compared with myoblasts without macrophages, #P < 0.05 compared with myoblasts + macrophages from TS muscle.

Delay of satellite cell activation in tail-suspended mice.

We examined the effect of unloading stress on the activation of satellite cells by immunohistochemical analysis with an antibody against MyoD, because the expression of MyoD represents activated satellite cells (7). Large numbers of MyoD-positive mononuclear cells, i.e., activated satellite cells, were identified in soleus muscles of CTX-injected WB mice, compared with CTX-injected TS mice (Fig. 6, A and B). To evaluate the effect of unloading stress on the formation of regenerating myofibers, we also performed immunohistochemical analysis using an antibody against embryonic MyHC, which is expressed in regenerated myofibers (37). In CTX-injected WB mice, myofibers expressing embryonic MyHC were observed from day 3 and reached a peak on day 7 (Fig. 6, C and D). In contrast, in CTX-injected TS soleus muscle, the appearance of embryonic MyHC-positive fibers was delayed: only a few and small-size embryonic MyHC-positive fibers were noted up to days 5 and 7. On day 14, their number became similar to that observed in CTX-injected WB soleus muscle on day 7.

Fig. 6.

Delayed activation of satellite cells in tail-suspended mice. A–D: representative sections (8 μm thickness) of soleus muscles of WB and TS mice were obtained at the indicated time points after injection of CTX or vehicle. A: representative sections were immunostained with an anti-MyoD (green) antibody and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Arrowheads: MyoD-positive mononuclear cells. Scale bar = 100 μm. B: MyoD-positive mononuclear cells were counted in 45 high-power fields per 15 sections in 5 mice per time point per group and are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle injection, #P < 0.05 compared with CTX-injected WB mice. C: representative sections were immunostained with an anti-embryonic MyHC (green) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bar = 100 μm. D: embryonic MyHC-positive cells were counted in 45 high-power fields per 15 sections in 5 mice per time point per group and are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle injection, #P < 0.05 compared with WB mice.

Expression of MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 mRNA was not associated with muscle regeneration.

Muscle atrophy-associated ubiquitin ligases (so-called atrogenes), such as MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1, contribute to skeletal muscle atrophy (27). To investigate whether unloading stress suppresses muscle regeneration through atrogene activation, we examined the time-dependent changes in the expressions of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 in vehicle- or CTX-injected soleus muscles. The mRNA expression of both atrogenes was upregulated in the soleus muscle of only vehicle-injected TS mice. In other groups, the mRNA levels did not change throughout the experiment (days 1–14) (Fig. 7, A and B). These results suggest that the disturbed muscle regeneration in CTX-injected TS mice is not associated with unloading-mediated muscle atrophy.

Fig. 7.

Kinetics of gene expression of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 in soleus muscles. A and B: levels of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 (A) and MuRF-1 (B) gene transcripts in soleus muscles of WB and TS mice on the indicated days after CTX or vehicle injection were assessed by real-time RT-PCR. The fluorescence ratio of target gene cDNA to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), a housekeeping gene, was calculated. Data are means ± SD of 5 mice per time point per group. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle injection.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, unloading stress resulted in persistent accumulation of proinflammatory macrophages at the site of injury, resulting in incomplete muscle regeneration. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that unloading stress suppresses muscle regeneration after injury by impairing the infiltration of immune cells and phagocytosis of necrotic myofibers.

Substantial evidence indicates that macrophages and satellite cells are essential for muscle regeneration after injury (5, 30, 33). For instance, CC chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) is a receptor for monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) to recruit macrophages (4). The CCR2-deficient mouse shows lack of infiltration of macrophages in the injured muscle after CTX injection, and significant delay in muscle regeneration (15, 21). In addition, Segawa et al. (28) depleted macrophages using an anti-macrophage colony stimulating factor antibody after CTX injection and noted suppression of mitogen responses and myotube formation of satellite cells. In the present study, unloading induced by tail suspension delayed macrophage infiltration into injured muscle. Tail suspension also delayed the activation of satellite cells and appearance of regenerated myofibers, consistent with the delayed infiltration of macrophages. Thus we suggest that delayed infiltration of macrophages into the injured skeletal muscle contributes, at least in part, to the disturbed muscle regeneration under unloading.

Although unloading delayed the infiltration of macrophages only for several days, the appearance of regenerated myofibers was inhibited by TS for at least 1 wk compared with WB skeletal muscle. Macrophage functions, such as phagocytosis, are also critical for muscle regeneration. Phagocytosis of necrotic muscle debris induces a switch in macrophages from a proinflammatory profile to an anti-inflammatory profile, and inhibition of phagocytosis prevents muscle regeneration as well as the phenotype switch of macrophages (1). To elucidate other factors, we examined in this study the interaction between macrophage functions and myogenesis. First, we noted an increased number of Ly-6C- and F4/80-positive macrophages and necrotic myofibers in the soleus muscles of CTX-injected TS mice after injury compared with CTX-injected WB mice. We also demonstrated that TS and 3D-clinorotation suppressed the phagocytotic ability of macrophages and RAW264.7 cells, respectively. Our coculture system of primary macrophages and myoblasts revealed that macrophages isolated from TS skeletal muscles showed disturbed myotube formation compared with those from WB muscles. Based on these findings, we conclude that the disturbance of muscle regeneration under unloading is due to impairment of macrophage function, inhibition of satellite cell activation, and their cooperation.

Riley et al. (25) demonstrated that tail suspension reduced soleus electromyogram activity. In addition, Woodman et al. (36) indicated that tail suspension disturbed vascular function in soleus (slow-twitch muscle) but not in gastrocnemius (fast-twitch muscle). Based on these findings, they suggest that the blood flow to slow-twitch muscles of the hindlimb may be reduced by tail suspension. However, we observed that tail suspension similarly disturbed muscle regeneration of tibialis anterior muscle as well as soleus muscle (data not shown), although the flow to the fast-twitch muscle, such as tibialis anterior muscle, was hardly affected by tail suspension (36). Therefore, we suggest that there is a negligible effect of reduced blood flow on the disturbed muscle regeneration in soleus muscle shown in the present study.

Skeletal muscles are sensitive to mechanical stress such as gravity and stretch (9). Under loading conditions, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) signaling promotes protein synthesis and suppresses protein degradation through Akt-dependent phosphorylation and sequestration of forkhead transcription factors, which leads to the inhibition of atrogenes in skeletal muscle (27, 29). Unloading impairs IGF-1-dependent pathways and increases the expression of atrogenes (19, 20, 31). In this study, the expression of atrogenes did not change during muscle regeneration in tail-suspended mice. Our (immuno)histochemical observations revealed that there was no intact myofiber in soleus muscle of CTX-injected TS mice until day 7 after the injection (Fig. 2A). Although on day 14 myofibers were regenerated even in CTX-injected TS soleus muscle, only immature embryonic MyHC-positive-fibers existed (Fig. 6C). In general, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 are upregulated in intact (mature) skeletal muscle in response to unloading conditions, such as tail suspension (8. 34). Since skeletal muscle fibers were destroyed or immature during regeneration, they possibly failed to stimulate atrogene expression in response to unloading conditions. We suggest that the mechanism of unloading-induced disturbance of muscle regeneration is distinct from that of unloading-related muscle atrophy.

In the present study, we demonstrated that unloading stress alters muscle regeneration, in association with delayed infiltration of macrophages into the site of muscle injury, together with failed changes in macrophages from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory phenotypes. Furthermore, disturbance of activation and differentiation of satellite cells was observed in muscle regeneration during unloading. In conclusion, the disturbed muscle regeneration under unloading is due to impaired macrophage function, inhibition of satellite cell activation, and their cooperation.

GRANTS

This study was supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences from the Bio-Oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution of Japan (to T. Nikawa and J. Terao).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.K., Y.Y., K.H., S.T.-K., Y.O., and T.N. conception and design of research; S.K., Y.Y., T.A., M.O., A.O., A.H., I.C., and J.T. performed experiments; S.K., Y.Y., T.A., M.O., A.O., A.H., I.C., and J.T. analyzed data; S.K. and K.H. interpreted results of experiments; S.K. and Y.Y. prepared figures; S.K. drafted manuscript; S.K., Y.Y., E.M.M., and T.N. edited and revised manuscript; S.K., Y.Y., K.H., M.O., A.O., S.T.-K., A.H., I.C., E.M.M., Y.O., J.T., and T.N. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arnold L, Henry A, Poron F, Baba-Amer Y, van Rooijen N, Plonquet A, Gherardi RK, Chazaud B. Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into antiinflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis. J Exp Med 204: 1057–1069, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Authier FJ, Chazaud B, Plonquet A, Eliezer-Vanerot MC, Poron F, Belec L, Barlovatz-Meimon G, Gherardi RK. Differential expression of the IL-1 system components during in vitro myogenesis: implication of IL-1β in induction of myogenic cell apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 6: 1012–1021, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Champion JA, Walker A, Mitragotri S. Role of particle size in phagocytosis of polymeric microspheres. Pharm Res 25: 1815–1821, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Charo IF, Taubman MB. Chemokines in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. Circ Res 95: 858–866, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chazaud B, Sonnet C, Lafuste P, Bassez G, Rimaniol AC, Poron F, Authier FJ, Dreyfus PA, Gherardi RK. Satellite cells attract monocytes and use macrophages as a support to escape apoptosis and enhance muscle growth. J Cell Biol 163: 1133–1143, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chazaud B, Brigitte M, Yacoub-Youssef H, Arnold L, Gherardi R, Sonnet C, Lafuste P, Chretien F. Dual and beneficial roles of macrophages during skeletal muscle regeneration. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 37: 18–22, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cooper RN, Tajbakhsh S, Mouly V, Cossu G, Buckingham M, Butler-Browne GS. In vivo satellite cell activation via Myf5 and MyoD in regenerating mouse skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci 112: 2895–2901, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foletta VC, White LJ, Larsen AE, Léger B, Russell AP. The role and regulation of MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in skeletal muscle atrophy. Pflügers Arch 461: 325–335, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goldspink G. Changes in muscle mass and phenotype and the expression of autocrine and systemic growth factors by muscle in response to stretch and overload. J Anat 194: 323–334, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hawke TJ, Garry DJ. Myogenic satellite cells: physiology to molecular biology. J Appl Physiol 91: 534–551, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirasaka K, Nikawa T, Yuge L, Ishihara I, Higashibata A, Ishioka N, Okubo A, Miyashita T, Suzue N, Ogawa T, Oarada M, Kishi K. Clinorotation prevents differentiation of rat myoblastic L6 cells in association with reduced NF-kappa B signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1743: 130–140, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hirata A, Masuda S, Tamura T, Kai K, Ojima K, Fukase A, Motoyoshi K, Kamakura K, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda S. Expression profiling of cytokines and related genes in regenerating skeletal muscle after cardiotoxin injection: a role for osteopontin. Am J Pathol 163: 203–215, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ikemoto M, Nikawa T, Takeda S, Watanabe C, Kitano T, Baldwin KM, Izumi R, Nonaka I, Towatari T, Teshima S, Rokutan K, Kishi K. Space shuttle flight (STS-90) enhances degradation of rat myosin heavy chain in association with activation of ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. FASEB J 15: 1279–1281, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malm C. Exercise immunology: a skeletal muscle perspective. Exerc Immunol Rev 8: 116–167, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martinez CO, McHale MJ, Wells JT, Ochoa O, Michalek JE, McManus LM, Shireman PK. Regulation of skeletal muscle regeneration by CCR2-activating chemokines is directly related to macrophage recruitment. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: R832–R842, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsuba Y, Goto K, Morioka S, Naito T, Akema T, Hashimoto N, Sugiura T, Ohira Y, Beppu M, Yoshioka T. Gravitational unloading inhibits the regenerative potential of atrophied soleus muscle in mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 196: 329–339, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morioka S, Goto K, Kojima A, Naito T, Matsuba Y, Akema T, Fujiya H, Sugiura T, Ohira Y, Beppu M, Aoki H, Yoshioka T. Functional overloading facilitates the regeneration of injured soleus muscles in mice. J Physiol Sci 58: 397–404, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mozdziak PE, Truong Q, Macius A, Schultz E. Hindlimb suspension reduces muscle regeneration. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 78: 136–140, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakao R, Hirasaka K, Goto J, Ishidoh K, Yamada C, Ohno A, Okumura Y, Nonaka I, Yasutomo K, Baldwin KM, Kominami E, Higashibata A, Nagano K, Tanaka K, Yasui N, Mills EM, Takeda S, Nikawa T. Ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b is a negative regulator for IGF-1 signaling during muscle atrophy caused by unloading. Mol Cell Biol 29: 4798–4811, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nikawa T, Ishidoh K, Hirasaka K, Ishihara I, Ikemoto M, Kano M, Kominami E, Nonaka I, Ogawa T, Adams GR, Baldwin KM, Yasui N, Kishi K, Takeda S. Skeletal muscle gene expression in space-flown rats. FASEB J 18: 522–524, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ochoa O, Sun D, Reyes-Reyna SM, Waite LL, Michalek JE, McManus LM, Shireman PK. Delayed angiogenesis and VEGF production in CCR2−/− mice during impaired skeletal muscle regeneration. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R651–R661, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ogawa T, Nikawa T, Furochi H, Kosyoji M, Hirasaka K, Suzue N, Sairyo K, Nakano S, Yamaoka T, Itakura M, Kishi K, Yasui N. Osteoactivin upregulates expression of MMP-3 and MMP-9 in fibroblasts infiltrated into denervated skeletal muscle in mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289: C697–C707, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ojima K, Uezumi A, Miyoshi H, Masuda S, Morita Y, Fukase A, Hattori A, Nakauchi H, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda S. Mac-1 (low) early myeloid cells in the bone marrow-derived SP fraction migrate into injured skeletal muscle and participate in muscle regeneration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 321: 1050–1061, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orimo S, Hiyamuta E, Arahata K, Sugita H. Analysis of inflammatory cells and complement C3 in bupivacaine-induced myonecrosis. Muscle Nerve 14: 515–520, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Riley DA, Slocum GR, Bain JL, Sedlak FR, Sowa TE, Mellender JW. Rat hindlimb unloading: soleus histochemistry, ultrastructure, and electromyography. J Appl Physiol 69: 58–66, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Robertson TA, Maley MA, Grounds MD, Papadimitriou JM. The role of macrophages in skeletal muscle regeneration with particular reference to chemotaxis. Exp Cell Res 207: 321–331, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sandri M, Sandri C, Gilbert A, Skurk C, Calabria E, Picard A, Walsh K, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell 117: 399–412, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Segawa M, Fukada S, Yamamoto Y, Yahagi H, Kanematsu M, Sato M, Ito T, Uezumi A, Hayashi S, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda S, Tsujikawa K, Yamamoto H. Suppression of macrophage functions impairs skeletal muscle regeneration with severe fibrosis. Exp Cell Res 314: 3232–3244, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stitt TN, Drujan D, Clarke BA, Panaro F, Timofeyva Y, Kline WO, Gonzalez M, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol Cell 14: 395–403, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Summan M, Warren GL, Mercer RR, Chapman R, Hulderman T, Van Rooijen N, Simeonova PP. Macrophages and skeletal muscle regeneration: a clodronate-containing liposome depletion study. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R1488–R1495, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suzue N, Nikawa T, Onishi Y, Yamada C, Hirasaka K, Ogawa T, Furochi H, Kosaka H, Ishidoh K, Gu H, Takeda S, Ishimaru N, Hayashi Y, Yamamoto H, Kishi K, Yasui N. Ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b downregulates bone formation through suppression of IGF-I signaling in osteoblasts during denervation. J Bone Miner Res 21: 722–734, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tidball JG. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R345–R353, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tidball JG, Wehling-Henricks M. Macrophages promote muscle membrane repair and muscle fibre growth and regeneration during modified muscle loading in mice in vivo. J Physiol 578: 327–336, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tintignac LA, Lagirand J, Batonnet S, Sirri V, Leibovitch MP, Leibovitch SA. Degradation of MyoD mediated by the SCF (MAFbx) ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem 280: 2847–2856, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang XD, Kawano F, Matsuoka Y, Fukunaga K, Terada M, Sudoh M, Ishihara A, Ohira Y. Mechanical load-dependent regulation of satellite cell and fiber size in rat soleus muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C981–C989, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Woodman CR, Schrage WG, Rush JW, Ray CA, Price EM, Hasser EM, Laughlin MH. Hindlimb unweighting decreases endothelium-dependent dilation and eNOS expression in soleus not gastrocnemius. J Appl Physiol 91: 1091–1098, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang L, Ran L, Garcia GE, Wang XH, Han S, Du J, Mitch WE. Chemokine CXCL 16 regulates neutrophil and macrophage infiltration into injured muscle, promoting muscle regeneration. Am J Pathol 175: 1–10, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]