Abstract

This study examined the effectiveness of a short-duration but high-intensity exercise countermeasure in combination with a novel oral volume load in preventing bed rest deconditioning and orthostatic intolerance. Bed rest reduces work capacity and orthostatic tolerance due in part to cardiac atrophy and decreased stroke volume. Twenty seven healthy subjects completed 5 wk of −6 degree head down bed rest. Eighteen were randomized to daily rowing ergometry and biweekly strength training while nine remained sedentary. Measurements included cardiac mass, invasive pressure-volume relations, maximal upright exercise capacity, and orthostatic tolerance. Before post-bed rest orthostatic tolerance and exercise testing, nine exercise subjects were given 2 days of fludrocortisone and increased salt. Sedentary bed rest led to cardiac atrophy (125 ± 23 vs. 115 ± 20 g; P < 0.001); however, exercise preserved cardiac mass (128 ± 38 vs. 137 ± 34 g; P = 0.002). Exercise training preserved left ventricular chamber compliance, whereas sedentary bed rest increased stiffness (180 ± 170%, P = 0.032). Orthostatic tolerance was preserved only when exercise was combined with volume loading (−10 ± 22%, P = 0.169) but not with exercise (−14 ± 43%, P = 0.047) or sedentary bed rest (−24 ± 26%, P = 0.035) alone. Rowing and supplemental strength training prevent cardiovascular deconditioning during prolonged bed rest. When combined with an oral volume load, orthostatic tolerance is also preserved. This combined countermeasure may be an ideal strategy for prolonged spaceflight, or patients with orthostatic intolerance.

Keywords: atrophy, hypertrophy, myocardium, rowing

sustained exposure to microgravity leads to changes in the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems that can limit normal activities of astronauts. Cardiovascular deconditioning during spaceflight (29), or its ground-based analog of bed rest, leads to myocardial atrophy (40) and chamber stiffening, decreased plasma volume (26), and orthostatic intolerance (5, 32). This degradation of cardiovascular function combined with skeletal muscle atrophy results in an impaired work capacity (2), which may be especially profound in the upright posture.

Bed rest with a 6 degree head down tilt (HDTBR) is used as an earth analog to microgravity because it reproduces the hydrostatic gradients in a similar fashion, and there are similar reductions in cardiac mass, plasma volume, aerobic capacity, and orthostatic tolerance as in spaceflight (34, 40). Our laboratory recently showed that as little as 2 wk of sedentary HDTBR resulted in significant cardiac atrophy, a leftward shift of the left ventricular (LV) pressure-volume relationship suggesting a reduction in LV distensibility, and a greater reduction in orthostatic stroke volume (SV) than hypovolemic controls (32, 40, 43).

The optimal countermeasure for the cardiovascular system during spaceflight or bed rest has not been determined, although exercise has always played a central role (39). For example, we recently showed that 2 wk of supine cycling for 90 min/day was sufficient to prevent cardiac remodeling (43). However, in space, prolonged exercise has a substantial impact on resources in terms of time, calorie use, water loss, and heat generation. For this study, rowing was chosen as the primary exercise modality (along with strength training) because of its low impact plus its combination of high-intensity dynamic and static exercise components while utilizing a large muscle mass (45). As a consequence, rowing leads to a marked hypertrophy stimulus (7, 44), and we hypothesized that it would be especially effective at preventing cardiovascular deconditioning during limited-duration exercise sessions. Besides the novelty of using rowing as an exercise countermeasure, no bed rest studies to date have used a comprehensive training program as typically followed by competitive endurance athletes incorporating submaximal intensity base training, higher-intensity intervals, and regular strength training.

The reduction in plasma volume is also an important contributor to bed rest and spaceflight-induced cardiovascular deconditioning (49). However, plasma volume repletion by itself has been unsuccessful in preventing orthostatic intolerance from bed rest or spaceflight (6, 15, 43). As such, maintenance of cardiovascular structure and volume appears to be necessary but not sufficient alone to preserve orthostatic tolerance (43); both are needed for optimal performance. Because an integrated countermeasure consisting of an intense exercise training paradigm coupled with a simple and effective volume-loading strategy may be required, a novel volume-loading strategy using oral fludrocortisone and increased dietary salt intake was evaluated with the exercise training intervention.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was twofold: first, to assess whether a rowing-based exercise countermeasure, of high intensity but short duration, is sufficient to prevent the cardiac atrophy and cardiovascular deconditioning associated with prolonged (5 wk) bed rest; second, to prevent orthostatic intolerance associated with prolonged bed rest by integrating a novel and cost-effective oral volume-loading strategy with this intense exercise program.

METHODS

Twenty seven healthy, nonsmoking, 20- to 54-yr-old adults were enrolled in this study. All subjects were normotensive by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and had a normal electrocardiogram (ECG) and stress echocardiogram. All subjects signed an informed consent form approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas and Presbyterian Hospital.

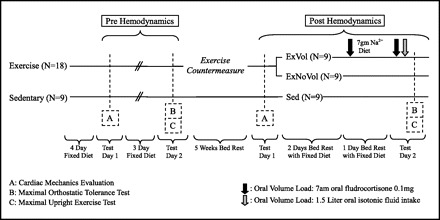

Figure 1 depicts an outline of the study protocol. Subjects were allocated into groups based on age, body surface area (BSA), fitness, and sex and then randomly assigned to either the exercise arm or sedentary arm in a 2:1 fashion. Nine sedentary subjects (1 female) and 18 exercise subjects (2 females) completed 5 wk of −6 degree head down tilt.

Fig. 1.

Study design: 5 wk of 6 degree head down tilt bed rest and the following two countermeasures: 1) rowing ergometry and resistance training and 2) oral volume loading. Exercise (n = 18) depicts the exercise training countermeasure. Following the 5 wk of exercise countermeasure, the exercise group was split into ExVol (n = 9), who received the oral volume load, and ExNoVol (n = 9), who did not receive volume expansion. Sedentary (n = 9; Sed) depicts sedentary bed rest without any countermeasures. Testing scheme and schedule were matched pre- and postbed rest. Testing days 1 and 2 were separated by at least 72 h.

Exercise Countermeasure

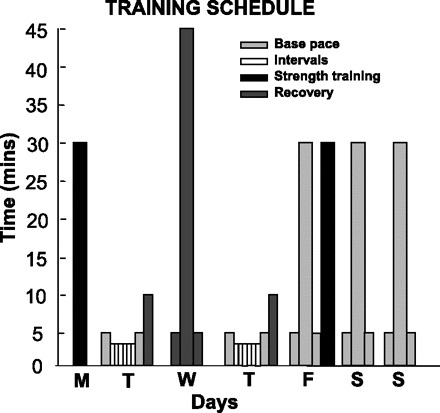

Exercise training consisted of both endurance and strength training. Endurance training was performed on a rowing ergometer (Concept2) 6 days/wk in a periodized training protocol as outlined in Fig. 2. Sedentary subjects sat upright with legs outstretched in the rowing position for an equivalent time. Heart rate (HR) monitors (Polar electro) were used during exercise for guiding exercise intensity. The subject's HR at ventilatory threshold, or maximal steady-state (MSS) HR, was measured during baseline exercise testing and used with maximal HR to divide exercise intensity into four training zones consisting of: 1) recovery, 2) base, 3) MSS, and 4) interval as previously described (22). During intervals, subjects were instructed to row for 3 min within the interval zone followed by 3 min in the recovery zone for six cycles.

Fig. 2.

Exercise subject's training schedule: a comprehensive periodized competitive-style training program with biweekly resistance training is shown in black. Rowing intensity prescription as: “base” training, “recovery” training, and “interval” training, with 6 repetitions of 3 min followed by 3 min of recovery. Exercises are preceded and followed by appropriate warm-up and cool-down periods.

To maximize preservation of strength, resistance training was performed in the supine position using a modified RiPP Pro device (Schwinn) utilizing the SpiraFlex elastomer Flexpacks technology duplicated in the international space station resistance exercise device (37). Two sets each of lower-body exercise (consisting of leg press, hip abduction, and plantar, knee, and hip flexion) and one set each of upper-body exercise (consisting of crunches, pullovers, elbow flexion, and shoulder, chest, and elbow press) were performed biweekly as per guidelines on resistance training (13). Intensity was adjusted weekly to reach the point of fatigue during 8–12 repetitions. Exercising subjects also performed 25 repetitions of plantarflexion exercises two times daily using elastic bands as resistance.

Volume-Loading Countermeasure

Beginning the final day of bed rest, one-half of the exercise group was randomized to receive the volume-loading protocol (ExVol), whereas the other exercise subjects (ExNoVol) and the sedentary subjects continued their regular fixed diet and fluid intake. As shown in the protocol (Fig. 1), the ExVol group began the final day of bed rest at 7:00 A.M. with a dose of 0.1 mg oral fludrocortisone followed by an increased 7-g salt diet for 24 h. On the final day of testing, the ExVol group ingested a second 7:00 A.M. dose of 0.1 mg oral fludrocortisone, a light breakfast from a 7-g salt diet, and then 1.5 liters of a glucose-electrolyte beverage 2 h before maximal orthostatic tolerance testing.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging measurements.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data acquisition and analysis of LV mass and volumes were performed as previously described (1). LV mass was computed as the difference between the areas of the manually drawn epicardial and endocardial borders multiplied by the density of heart muscle, 1.05 g/ml (24).

LV pressure-volume measurements.

A 6-Fr balloon-tipped, fluid-filled catheter (Swan-Ganz; Baxter) was placed through an antecubital vein into the pulmonary artery with fluoroscopic guidance as previously described (32). Pressure measurements were referenced to atmospheric pressure, which was zeroed at 5 cm below the sternal angle. At each stage, three measurements of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) during end expiration were recorded and averaged.

Three-dimensional echocardiography (iE33; Philips) was used to measure LV volumes by a standard apical method as described by the American Society of Echocardiography (21). LV volumes were calculated using an offline analysis package (Qlab 3DQA; Philips). Our laboratory assessment of LV volumes by three-dimensional measurements resulted in good correlation with MRI values, with a typical error of measurement expressed as a coefficient of variation of 10% (95% confidence interval, 8–15).

Cardiac output measurements were performed using a modified acetylene rebreathing technique that has been validated in our laboratory (23). HR was recorded using a three-lead ECG (Hewlett-Packard). SV was calculated from cardiac output and HR during the rebreathing measurement. An electrosphygmomanometric cuff (SunTech 4240) was used for blood pressure assessments.

To generate the hemodynamic changes necessary to measure pressure-volume relationships, we used a sequence of lower-body negative pressure (LBNP) and rapid saline infusion to decrease and increase cardiac-loading conditions as previously reported (28, 32, 43). Measurements of PCWP, HR, cardiac output, and left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) were made at baseline and again after 5 min of −15 and −30 mmHg LBNP. After 30 min of rest, baseline measurements were repeated. Warm (37°C) isotonic saline was then rapidly infused at a rate of 200 ml/min to increase cardiac loading with hemodynamic measurements made after 15 ml/kg and again after 30 ml/kg were infused.

Maximal LBNP

Before maximal LBNP testing, all subjects followed a 4-day fixed diet and fluid intake. Maximal orthostatic tolerance was tested using a ramped LBNP protocol that has been previously described in detail (43). Maximal orthostatic tolerance was quantified from the cumulative stress index (CSI), calculated by the summation of time multiplied by LBNP for each level completed, and reported in units of millimeters mercury per minute.

Maximal Exercise

The hemodynamic and metabolic responses to maximal upright exercise were measured using a cycle ergometer (Lode) and a previous protocol including two steady-state levels followed by an incremental test to maximal effort (43). Respiratory gas collection and analysis were assessed as previously described (43). Although exercise training was performed with rowing, testing was performed on a cycle ergometer for the following three reasons: 1) we wanted to assess the overall response of the countermeasure to upright exercise rather than the semirecumbency of rowing while avoiding the injury risk of a treadmill immediately after bed rest; 2) we wanted to maximize the generalizability of the countermeasure by avoiding the specificity of testing in the same modality as the training stimulus; and 3) we wanted to take advantage of the highly specific and reproducible testing protocols available on an electronically braked cycle ergometer, in contrast to rowing testing protocols, which are more dependent on the stroke frequency and effort of the subject.

Plasma Volume

Hemoglobin mass was measured using a modified carbon monoxide rebreathing method (16). A baseline hematocrit obtained from a 20-min supine rest period was used to calculate plasma and blood volume.

Bed Rest

After completing baseline testing, subjects began 6 degree HDTBR for 5 wk in the General Clinical Research Center of The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. A baseline weight was obtained after the initial 72 h of bed rest because of the associated early decrease in plasma volume. Weights were followed biweekly with adjustment of caloric intake to maintain a stable body weight. Normal circadian rhythms were strictly controlled with scheduled lights-out and lights-on times.

Upon completion of 5 wk HDTBR, subjects underwent posttesting with MRI followed by invasive pressure-volume measurements. Bed rest was continued for three more days with a fixed sodium and fluid diet. The final 24 h of bed rest was performed with or without the volume-loading protocol and followed by maximal orthostatic tolerance testing and subsequent maximal upright exercise testing.

Data Analysis

Pressure-volume relations.

As a measurement of static chamber stiffness of the left ventricle, pressure-volume curves were constructed from PCWP and LVEDV data with an exponential regression (1, 35).

where P and V are the variables of PCWP and LVEDV, respectively. The calculated coefficients are: P∝, the pressure asymptote of the curve; V0, the LV volume when P = 0 mmHg; and “a,” a stiffness constant.

Given that LV diastolic pressure is influenced by external constraining forces and may complicate measurements of compliance (9), myocardial compliance curves were generated using an estimated transmural pressure [PCWP − right atrial pressure (RAP)] (46) and LVEDV. Exponential regression analyses were performed with commercially available software (Sigmaplot 10.0; Systat Software) using a Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± SD, except graphical representations, which use SE. All statistical analyses were performed with a commercially available analysis program (SigmaStat; Systat Software). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used for the comparison of the differences between pre- and postbed rest and to test interactions among groups. A Tukey's post hoc test was applied when the P value was <0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline Hemodynamics

All baseline measurements of cardiac filling pressures (PCWP and RAP) and SV significantly decreased in both groups after HDTBR regardless of exercise training, although the sedentary group had a greater decrease in filling pressure and volume (Table 1). Plasma and blood volume also decreased in both groups, again with a larger decrease in the sedentary subjects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline hemodynamics

| Exercise (n = 18) |

Sedentary (n = 9) |

P |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Condition: | Pre | Post | Change, % | Pre | Post | Change, % | PrePost | Ex vs. Sed | Int |

| Weight, kg | 77 ± 13 | 76 ± 12 | −2.1 ± 2.7 | 71 ± 10 | 71 ± 11 | −0.1 ± 3.5 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.10 |

| Plasma volume, liters | 3.40 ± 0.68 | 3.16 ± 0.62 | −6.4 ± 7.8 | 3.30 ± 0.69 | 2.95 ± 0.67 | −10.6 ± 11.1 | <0.001* | 0.56 | 0.38 |

| Blood volume, liters | 5.36 ± 1.08 | 4.97 ± 0.97 | −6.7 ± 7.1 | 5.19 ± 1.05 | 4.70 ± 0.97 | −9.3 ± 7.4 | <0.001* | 0.59 | 0.56 |

| MBP, mmHg | 85 ± 6 | 84 ± 6 | −0.7 ± 6.4 | 85 ± 9 | 84 ± 7 | −0.9 ± 5.5 | 0.43 | 0.89 | 0.93 |

| Qco, l/min | 5.9 ± 2.2 | 5.5 ± 2.3 | −8.3 ± 11.1 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | −2.6 ± 25.0 | 0.08* | 0.65 | 0.43 |

| HR, beats/min | 68 ± 7 | 70 ± 9 | 3.1 ± 9.7 | 67 ± 10 | 78 ± 13 | 16.6 ± 9.9 | <0.001* | 0.33 | <0.01* |

| SV, ml | 89 ± 36 | 80 ± 39 | −10.4 ± 14.1 | 82 ± 11 | 68 ± 14 | −16.7 ± 17.1 | <0.001* | 0.48 | 0.31 |

| TPR, dyne · s · cm−5 | 1,222 ± 262 | 1,348 ± 345 | 10.1 ± 16.4 | 1,272 ± 218 | 1,359 ± 417 | −6.7 ± 22.6 | 0.046* | 0.80 | 0.71 |

| PCWP, mmHg | 11.8 ± 1.5 | 10.2 ± 2.2 | −13.4 ± 16.9 | 12.1 ± 1.6 | 9.5 ± 2.0 | −22.1 ± 10.9 | <0.001* | 0.78 | 0.19 |

| RAP, mmHg | 8.7 ± 1.3 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | −17.9 ± 18.2 | 8.4 ± 1.2 | 6.4 ± 1.4 | −23.4 ± 17.4 | <0.001* | 0.34 | 0.53 |

| MRI LVEDV, ml | 144 ± 23 | 137 ± 25 | −4.5 ± 11.7 | 147 ± 16 | 123 ± 15 | −16.2 ± 8.5 | <0.001* | 0.45 | 0.02* |

| MRI LV mass, g | 128 ± 38 | 137 ± 34 | 8.6 ± 9.1 | 125 ± 23 | 115 ± 20 | −8.0 ± 4.0 | 0.72 | 0.36 | <0.001* |

| Chamber stiffness | 0.029 ± 0.013 | 0.037 ± 0.019 | 32 ± 57 | 0.022 ± 0.015 | 0.043 ± 0.020 | 180 ± 169 | 1.0 | 0.04* | 1.0 |

| V0, ml | 47 ± 26 | 36 ± 22 | −3 ± 67 | 62 ± 27 | 34 ± 26 | −51 ± 37 | <0.001* | 0.49 | 0.05* |

Values are means ± SD; n, no. of subjects. Int, Interaction; MBP, mean blood pressure; Qco, cardiac output; HR, heart rate; SV, stroke volume; TPR, total peripheral resistance; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; RAP, right atrial pressure; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); LV mass, left ventricular mass by MRI; V0, equilibrium volume.

P < 0.05.

MRI-measured LVEDV was preserved in the exercise group (144 ± 23 vs. 137 ± 25 ml, P = 0.099) but was reduced significantly in the sedentary subjects after HDTBR (147 ± 16 vs. 123 ± 15 ml, P = 0.001) (Table 1). LV mass increased by 8.6 ± 9.1% in the exercise group but was reduced 8.0 ± 4.0% in the sedentary group (interaction P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Although caloric intake was adjusted to attempt to maintain body weight, the exercise group lost weight with training (77.8 ± 13.5 vs. 76.1 ± 13.7 kg, P = 0.004), primarily through loss of lean body mass (57.2 ± 9.8 vs. 56.3 ± 10.5 kg, P = 0.003) while the sedentary subjects maintained their baseline weight (71.3 ± 10.2 vs. 71.2 ± 10.5 kg, P = 0.9) and lead body mass (55.3 ± 7.6 vs. 55.3 ± 8.2 kg, P = 0.9).

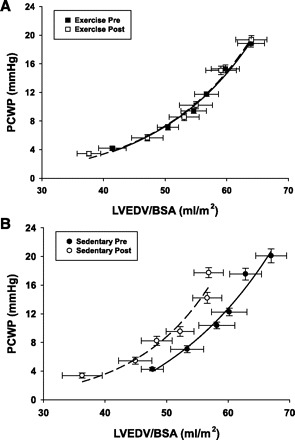

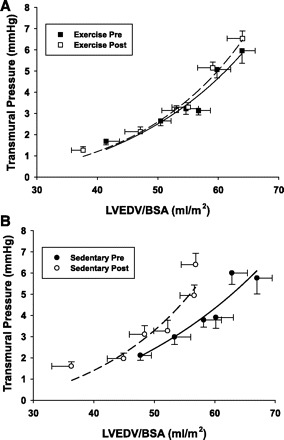

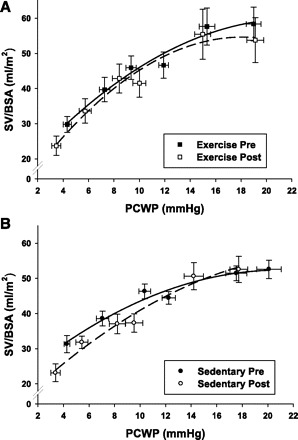

Pressure-Volume Curves

Measurements of LVEDV indexed by BSA were used to generate pressure-volume curves shown in Fig. 3. The pressure-volume curves were identical in the exercise group from pre- to postbed rest. Conversely, the sedentary post-bed-rest curve is shifted left and upward. The stiffness constants calculated from group mean data showed similar results with preserved compliance in the exercise group (0.063 vs. 0.065/ml) and a 61% increase in ventricular stiffness postbed rest in the sedentary group (0.050 vs. 0.081/ml). The myocardial compliance curves (Fig. 4) similarly demonstrated a left and upward shift of the sedentary group with a 61% increase in stiffness compared with a 21% increase in the exercise subjects. This leftward shift in the sedentary group is also evidenced by a 180 ± 169% increase in the mean of the individual's LV chamber stiffness (0.022 ± 0.015 vs. 0.043 ± 0.020/ml, P < 0.001) and a fall in equilibrium volume (V0) (62.2 ± 26.5 vs. 34.0 ± 26.4 ml, P < 0.001). However, the mean of the individual's stiffness increased more modestly by 32 ± 57% in the exercise subjects (0.029 ± 0.013 vs. 0.037 ± 0.019/ml, P = 0.062), and V0 (46.9 ± 25.8 vs. 36.3 ± 21.9 ml, P = 0.041) remained relatively preserved.

Fig. 3.

Left ventricular pressure-volume curves: pre- and postbed rest in exercise and sedentary groups. Six data points correspond to 2 degrees of lower-body negative pressure (LBNP), 2 baselines, and 2 saline infusions. PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; BSA, body surface area.

Fig. 4.

Myocardial compliance curves: estimated transmural pressure (PCWP, right atrial pressure) and LVEDV for pre- and postbed rest in exercise and sedentary subjects.

Starling Curves

The Starling curves in the exercise group were superimposable from prebed rest to postbed rest (Fig. 5) but with a small shift of the baseline operating point down the curve. This finding was consistent with a preservation of cardiac mechanics but a mild loss in filling pressure and plasma volume. The slope of the linear portion of the Starling curve changed minimally in the exercise group (change in slope: +17%, P = 0.08). The sedentary group demonstrated a larger downward shift of the operating point, consistent with a lower resting PCWP and SV, while the linear portion of the post-bed-rest curve demonstrated an increase in slope, consistent with a larger decrease in SV for any given decrease in PCWP below baseline (change in slope: +29%, P = 0.11).

Fig. 5.

Starling curves: before (pre) and after (post) bed rest in the exercise and sedentary groups. Shown are mean group data ± SE for stroke volume (SV) at given PCWP. Six data points correspond to 2 degrees of LBNP, 2 baselines, and 2 saline infusions. Curves were drawn by second linear regression based on mean values for each condition.

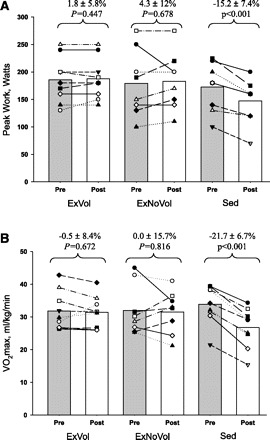

Maximal Exercise Results

Peak HR was unaffected in the three groups after bed rest, although peak SV decreased in the ExNoVol group (−12.7 ± 19.2%; P = 0.072) and the sedentary group (−28.7 ± 13.7%; P = 0.001), whereas it was unaffected in the ExVol subjects (Table 2). Cardiac output mirrored changes seen in SV, demonstrating a significant fall in maximal cardiac output in the sedentary group (−29.0 ± 12.2%; P = 0.001), with a smaller decrease in the ExNoVol group (−12.9 ± 19%; P = 0.063), whereas exercise training with oral volume loading preserved maximal upright cardiac output (Table 2). Maximal oxygen uptake decreased 22% in the sedentary group (33.9 ± 5.8 vs. 26.7 ± 6.0 ml·kg−1·min−1; P < 0.001), whereas peak work load decreased 15% (173 ± 42 vs. 147 ± 38 watts; P < 0.001) (Fig. 6, A and B). Conversely, V̇o2 max and peak work load were preserved with training in both the ExVol and ExNoVol subjects (Fig. 6, A and B).

Table 2.

Maximal exercise results

| ExVol (n = 9) |

ExNoVol (n = 8) |

Sed (n = 9) |

P |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Condition: | Pre | Post | Change, % | Pre | Post | Change, % | Pre | Post | Change, % | PrePost | Sed vs. ExVol vs. ExNoVol | Int |

| V̇o2max, l/min | 2.50 ± 0.47 | 2.41 ± 0.33 | −2.3 ± 6.9 | 2.38 ± 0.59 | 2.34 ± 0.59 | −1.1 ± 14.9 | 2.38 ± 0.46 | 1.87 ± 0.37 | −21.5 ± 6.1 | <0.001* | 0.29 | 0.001* |

| Qci max, l · min−1 · m−2 | 8.8 ± 2.0 | 8.3 ± 1.8 | −4.4 ± 15.5 | 8.8 ± 2.6 | 7.5 ± 2.1 | −12.9 ± 19.0 | 9.2 ± 2.0 | 6.4 ± 1.3 | −29.0 ± 12.2 | <0.001* | 0.67 | 0.02* |

| A–V Do2 max | 14.8 ± 2.7 | 15.4 ± 3.2 | 4.1 ± 15.1 | 14.6 ± 3.3 | 16.7 ± 3.3 | 19.0 ± 34.3 | 14.3 ± 1.7 | 16.1 ± 2.7 | 14.0 ± 24.5 | 0.04 | 0.89 | 0.62 |

| HRmax, beats/min | 180 ± 8 | 179 ± 10 | −0.8 ± 3.0 | 190 ± 9 | 190 ± 9 | −0.2 ± 2.3 | 184 ± 16 | 185 ± 20 | 0.1 ± 6.5 | 0.73 | 0.23 | 0.90 |

| SVImax, ml · beat−1 · m−2 | 50 ± 13 | 46 ± 10 | −5.2 ± 17.4 | 46 ± 13 | 40 ± 12 | −12.7 ± 19.2 | 50 ± 12 | 35 ± 8 | −28.7 ± 13.7 | <0.001* | 0.46 | 0.06 |

Values are means ± SD; n, no. of subjects. ExVol, exercise group that received oral volume load; NoExVol, exercise group that did not receive oral volume load; Sed, sedentary group; V̇o2max, maximal oxygen uptake; Qci max, maximum Qco divided by body surface area; A–V Do2 max, maximal arteriovenous oxygen difference; HRmax, maximal heart rate; and SVImax, maximal SV divided by body surface area.

P < 0.05.

Fig. 6.

A: peak work rate: pre- and postbed rest in ExVol, ExNoVol, and in the sedentary group without exercise or volume loading (Sed). B: maximal oxygen uptake (V̇o2): pre- and postbed rest in ExVol, ExNoVol, and Sed groups.

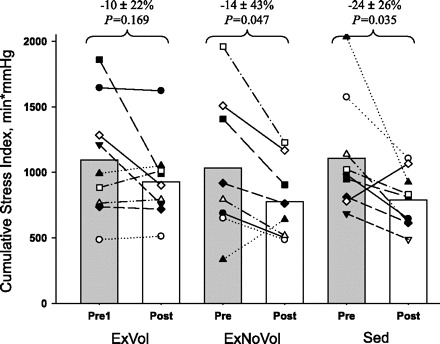

Orthostatic Tolerance

Maximal orthostatic tolerance as measured by CSI was preserved in ExVol (1,096 ± 447 vs. 928 ± 311 mmHg·min, P = 0.169; Fig. 7), whereas it was reduced in both ExNoVol (1,032 ± 541 vs. 776 ± 297 mmHg·min, P = 0.047) and the sedentary group (1,108 ± 433 vs. 790 ± 215 mmHg·min, P = 0.035). Furthermore, six of nine ExVol subjects showed an unchanged or even increased CSI, whereas eight of nine sedentary subjects had a decreased CSI (P = 0.049 by χ2-test).

Fig. 7.

Orthostatic tolerance: maximal LBNP tolerance pre and post head down tilt bed rest in ExVol, ExNoVol, and Sed groups.

As a measure of hemodynamics during upright posture, SV was evaluated at −40 mmHg of LBNP because the head-to-foot hydrostatic gradients are approaching those of orthostasis (50). At LBNP −40 mmHg, SV was reduced by 38 ± 15% in sedentary (44.6 ± 21.1 vs. 27.1 ± 10.1 l·min−1·kg−1, P = 0.010), 13 ± 11% in ExNoVol (41.8 ± 12.3 vs. 33.6 ± 11.5 l·min−1·kg−1, P = 0.041), and 1.7 ± 33% in the ExVol group (45.6 ± 27.2 vs. 42.1 ± 25.7 l·min−1·kg−1, P = 0.317) group.

DISCUSSION

The principal new findings from this study were that: 1) 5 wk of 6 degree head down tilt bed rest led to a smaller, less-distensible, and less-compliant ventricle as shown by a leftward and upward shift in the LV pressure-volume relationships; 2) the cardiac atrophy and stiffening that occur with sedentary bed rest were prevented by a well-periodized exercise program consisting of rowing ergometry and strength training; and 3) the exercise program maintained post-bed-rest upright exercise capacity, but only when coupled with an oral volume load did it prevent the orthostatic intolerance commonly seen with prolonged bed rest. These findings suggest that exercise during bed rest and volume restoration before assuming the upright posture can successfully prevent orthostatic intolerance and preserve upright exercise capacity despite the deconditioning associated with prolonged bed rest and possibly spaceflight.

Despite following a shorter exercise regimen than previous studies (43), rowing for <1 h/day preserved upright exercise capacity after 5 wk of bed rest. In addition to doubling the duration of bed rest and exercise compared with previous work (43), the choice of mode of exercise and the strategy of implementation in this study was also unique. No previous bed rest countermeasure studies have used a comprehensive training program as followed by competitive endurance athletes (3, 31). When such training is performed over very prolonged periods of time (25 yr), recent studies have demonstrated that even cardiac stiffening from aging can be prevented (1). The use of periodized elite athlete training programs to prevent bed rest deconditioning makes intuitive sense, but until now has never been tested directly.

Importance of Cardiac Mass for Orthostatic Tolerance

Regulation of cardiac myocyte cell size has been shown closely related to changes in cardiac-loading conditions (8, 47), including physical activity (27). The molecular mechanisms governing this regulation have recently been reviewed comprehensively (20). Sedentary bed rest causes ∼1%/wk loss of cardiac mass through 12 wk of bed rest (10, 40). If such atrophy continued unabated during 6 mo in microgravity, an ∼25% reduction in cardiac mass could be observed.

Based on the direct relationship between cardiac work and LV mass, we hypothesized that the reduction in wall stress combined with the reduction in physical activity led to cardiac atrophy during bed rest (32, 40). Previous measurements during sedentary bed rest demonstrated a decrease in stroke work by ∼18% compared with normal ambulation (32). Ninety minutes of daily supine cycling at 75% of maximal HR was sufficient to normalize cardiac work and prevent cardiac atrophy during 18 days of 6 degree head down tilt bed rest (43). In fact, 90 min of dynamic cycle ergometry exercise may be excessive, since the subjects developed myocardial hypertrophy in response to training. As such, the duration of exercise sessions might be reduced and optimized with a different mode of exercise. This is a key goal for astronauts due to time and resource constraints.

One such candidate exercise modality is rowing. Rowing is the prototype of a combined high-dynamic/high-static exercise that results in substantial myocardial hypertrophy (36). In fact, competitive rowers have the greatest degree of myocardial hypertrophy of any group of athletes (44), likely because of the marked increases in blood pressure during each stroke from the combination of dynamic and static exercise, and a brief Valsalva maneuver at the beginning of every pull that leads to a two- to threefold increase in pulse pressure (7). Although the true cardiac afterload during purely static exercise may be overestimated from arterial pressure alone (18), rowing activates >70% of the total body muscle mass (45) and clearly leads to a unique phenotype with prominent cardiac hypertrophy. Recently, a high-intensity 10-wk exercise program consisting of rowing and strength training three times a week in physically active experienced rowers was shown to increase LV diastolic area with an 18% increase in LV mass (12). Although a goal of this study was only to prevent atrophy, 5 wk of short-term rowing for 30–45 min/session combined with biweekly resistance training led to a 9% increase in cardiac mass, one-half that of the 10-wk program. Because of the high energy cost of rowing (17), the present study used a variable caloric intake based on weekly weights to balance energy expenditure; however, lean body mass decreased in exercising subjects, whereas cardiac mass increased. Compared with supine cycling, rowing is a time-effective mode of exercise to counteract the cardiac atrophy that is associated with bed rest.

Pressure-Volume Curves and Stiffness

Not only did this exercise countermeasure prevent cardiac atrophy and normalize the Starling curves after bed rest, but it also preserved LV chamber and myocardial compliance. Importantly, the exercise pre- and post-bed-rest curves were essentially superimposable, whereas the sedentary curves are shifted leftward and upward after bed rest. This shift is a result of stiffening of the LV chamber and a fall in distensibility, resulting in a smaller LVEDV for a given filling or transmural pressure.

The V0 was also calculated as a key measure of cardiovascular remodeling. V0 represents the point below which the ventricle must contract to produce recoil in early diastole to generate diastolic suction (38). The significant reduction in V0 demonstrated in the sedentary group suggests that dynamic ventricular filling may be impaired during bed rest as reported in other bed rest studies (32, 41, 43). For example, Dorfman et al. (11) showed impaired diastolic untwisting rates in sedentary subjects after bed rest, but preservation with exercise training. Supine cycling has shown relative preservation of V0 during bed rest (43), as does rowing, confirming that sufficient exercise helps prevent the deterioration of V0, and thus preserves diastolic suction.

Maintenance of SV

After adaptation to real or simulated microgravity, virtually all individuals studied exhibit an excessive fall in SV in the upright position (5, 30). As such, it is likely that, if this excessive fall in upright SV could be eliminated, then orthostatic intolerance would be improved or prevented (33, 43).

In the sedentary subjects of the present study, the fall in upright SV, as well as the reduction in plasma volume, PCWP, and LVEDV, was similar to that observed in previous bed rest studies (32, 41). Starling curves in the sedentary confirm an increased slope after bed rest (41, 43) such that, after bed rest, for any given PCWP below baseline, there was a smaller SV, compared with before bed rest (i.e., a different Starling curve), without a change in contractility. However, exercise sufficient to prevent cardiac atrophy almost prevents the change seen in sedentary bed rest but still results in a shift of the operating point down the curve. This displacement down the curve seems to imply preservation of cardiac mechanics with a mild loss in filling pressure and plasma volume.

Volume Loading in Addition to Exercise

Although exercise training by itself has been shown sufficient to normalize cardiac work and thereby cardiac mass, previous studies have emphasized the importance of normalizing plasma volume to prevent orthostatic intolerance (43, 49). We have recently shown that complete volume repletion with intravenous dextran after sedentary bed rest did not preserve exercise capacity or prevent orthostatic intolerance (43). Supine cycling alone worsened orthostatic intolerance, but, when combined with an infusion of intravenous dextran sufficient to normalize plasma volume and left atrial pressure, orthostatic tolerance was preserved after 18 days of bed rest (43). However, delivery of intravenous fluids in space would be challenging, given the number of astronauts and the amount of intravenous fluid needed for volume repletion. Moreover, the current National Aeronautic and Space Administration approach of ingesting salt tablets and drinking water (6) induces vomiting or gastrointestinal distress in many individuals. As such, to extend this countermeasure strategy to space, there was a need to develop an optimal strategy of oral rehydration.

Recent studies suggested that suppression of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAS) axis, and to a lesser degree antidiuretic hormone, compensates for an acute volume load with rapid renal excretion of salt and water (4, 19, 25). These studies suggest that stimulation of the RAS axis may be beneficial in preventing the renal excretion of a volume load when euhydrated. An acute fludrocortisone dose appeared to preserve plasma volume after 7 days of bed rest (48), but single-dose oral fludrocortisone (without dedicated salt loading) given to astronauts 7 h before landing did not improve orthostatic tolerance compared with controls (42). Unpublished pilot data showed that the combination of fludrocortisone with a high-salt diet and oral isotonic volume led to an expansion of plasma volume by 300–400 ml, with a peak volume 90 min postingestion that was sustained for at least 3 h.

The maintenance of plasma volume and thus cardiac filling appears to be the leading factor in preserving hemodynamics during orthostatic tolerance. This suggests that the use of this novel oral volume-loading protocol to restore cardiac filling volumes in conjunction with exercise to preserve cardiac mechanics can preserve orthostatic tolerance.

In conclusion, upright work capacity and orthostatic tolerance were preserved after 5 wk of bed rest using a novel periodized rowing ergometry training program to maintain cardiac mass and compliance followed by an oral volume load designed for sodium retention and normalization of cardiac filling volumes. This short-duration exercise program is a safe and easily implemented countermeasure for preservation of cardiac mass and LV compliance. These findings demonstrate a methodological improvement on prior integrated exercise countermeasures and are relevant not only for astronauts, but clinically for patients after prolonged confinement to bed rest, chronic reduction in physical activity, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (14), or even healthy aging (1).

GRANTS

This study was supported by the National Space Biomedical Research Institute through National Aeronautic and Space Administration NCC 9–58, American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship Grant No. 0525077Y, and the Clinical Translational Research Center (formerly General Clinical Research Center) Grant No. RR-00804.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.L.H., F.K., P.G.S., E.P., M.J., P.S.B., S.S., Q.F., M.D.P., and B.D.L. performed experiments; J.L.H. and M.J. analyzed data; J.L.H. and B.D.L. interpreted results of experiments; J.L.H. prepared figures; J.L.H. drafted manuscript; J.L.H., F.K., and B.D.L. edited and revised manuscript; J.L.H. and B.D.L. approved final version of manuscript; B.D.L. conception and design of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Concept2, Inc. (Morrisville, VT), for providing the rowing ergometer.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arbab-Zadeh A, Dijk E, Prasad A, Fu Q, Torres P, Zhang R, Thomas JD, Palmer D, Levine BD. Effect of aging and physical activity on left ventricular compliance. Circulation 110: 1799–1805, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baldwin KM. Effect of spaceflight on the functional, biochemical, and metabolic properties of skeletal muscle. Med Sci Sports Exercise 28: 983–987, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Banister EW, Morton RH, Fitz-Clarke J. Dose/response effects of exercise modeled from training: physical and biochemical measures. Ann Physiol Anthropol 11: 345–356, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bestle MH, Norsk P, Bie P. Fluid volume and osmoregulation in humans after a week of head-down bed rest. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R310–R317, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buckey JC, Jr, Lane LD, Levine BD, Watenpaugh DE, Wright SJ, Moore WE, Gaffney FA, Blomqvist CG. Orthostatic intolerance after spaceflight. J Appl Physiol 81: 7–18, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bungo MW, Charles JB, Johnson PC., Jr Cardiovascular deconditioning during space flight and the use of saline as a countermeasure to orthostatic intolerance. Aviat Space Environ Med 56: 985–990, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clifford PS, Hanel B, Secher NH. Arterial blood pressure response to rowing. Med Sci Sports Exercise 26: 715–719, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cooper Gt, Kent RL, Mann DL. Load induction of cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 21, Suppl 5: 11–30, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dauterman K, Pak PH, Maughan WL, Nussbacher A, Arie S, Liu CP, Kass DA. Contribution of external forces to left ventricular diastolic pressure. Implications for the clinical use of the Starling law. Ann Intern Med 122: 737–742, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dorfman TA, Levine BD, Tillery T, Peshock RM, Hastings JL, Schneider SM, Macias BR, Biolo G, Hargens AR. Cardiac atrophy in women following bed rest. J Appl Physiol 103: 8–16, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dorfman TA, Rosen BD, Perhonen MA, Tillery T, McColl R, Peshock RM, Levine BD. Diastolic suction is impaired by bed rest: MRI tagging studies of diastolic untwisting. J Appl Physiol 104: 1037–1044, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. duManoir GR, Haykowsky MJ, Syrotuik DG, Taylor DA, Bell GJ. The effect of high-intensity rowing and combined strength and endurance training on left ventricular systolic function and morphology. Int J Sports Med 28: 488–494, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feigenbaum MS, Pollock ML. Prescription of resistance training for health and disease. Med Sci Sports Exercise 31: 38–45, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fu Q, VanGundy TB, Galbreath MM, Shibata S, Jain M, Hastings JL, Bhella PS, Levine BD. Cardiac origins of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 55: 2858–2868, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gaffney FA, Buckey JC, Lane LD, Hillebrecht A, Schulz H, Meyer M, Baisch F, Beck L, Heer M, Maass H. The effects of a 10-day period of head-down tilt on the cardiovascular responses to intravenous saline loading Acta physiologica. Scandinavica 604: 121–130, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gore CJ, Bourdon PC, Woolford SM, Ostler LM, Eastwood A, Scroop GC. Time and sample site dependency of the optimized co-rebreathing method. Med Sci Sports Exercise 38: 1187–1193, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hagerman FC, Lawrence RA, Mansfield MC. A comparison of energy expenditure during rowing and cycling ergometry. Med Sci Sports Exercise 20: 479–488, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haykowsky M, Taylor D, Teo K, Quinney A, Humen D. Left ventricular wall stress during leg-press exercise performed with a brief Valsalva maneuver. Chest 119: 150–154, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heer M, Drummer C, Baisch F, Maass H, Gerzer R, Kropp J, Blomqvist CG. Effects of head-down tilt and saline loading on body weight, fluid, and electrolyte homeostasis in man. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 144: 13–22, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hill JA, Olson EN. Cardiac plasticity. N Engl J Med 358: 1370–1380, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hung J, Lang R, Flachskampf F, Shernan SK, McCulloch ML, Adams DB, Thomas J, Vannan M, Ryan T. 3D echocardiography: a review of the current status and future directions. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 20: 213–233, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iwasaki K, Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Levine BD. Dose-response relationship of the cardiovascular adaptation to endurance training in healthy adults: how much training for what benefit? J Appl Physiol 95: 1575–1583, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jarvis SS, Levine BD, Prisk GK, Shykoff BE, Elliott AR, Rosow E, Blomqvist CG, Pawelczyk JA. Simultaneous determination of the accuracy and precision of closed-circuit cardiac output rebreathing techniques. J Appl Physiol 103: 867–874, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Katz J, Milliken MC, Stray-Gundersen J, Buja LM, Parkey RW, Mitchell JH, Peshock RM. Estimation of human myocardial mass with MR imaging. Radiology 169: 495–498, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Latzka WA, Sawka MN, Montain SJ, Skrinar GS, Fielding RA, Matott RP, Pandolf KB. Hyperhydration: tolerance and cardiovascular effects during uncompensable exercise-heat stress. J Appl Physiol 84: 1858–1864, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leach CS, Alfrey CP, Suki WN, Leonard JI, Rambaut PC, Inners LD, Smith SM, Lane HW, Krauhs JM. Regulation of body fluid compartments during short-term spaceflight. J Appl Physiol 81: 105–116, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levine BD, Buckey JC, Fritsch JM, Yancy CW, Jr, Watenpaugh DE, Snell PG, Lane LD, Eckberg DL, Blomqvist CG. Physical fitness and cardiovascular regulation: mechanisms of orthostatic intolerance. J Appl Physiol 70: 112–122, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levine BD, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Friedman DB, Blomqvist CG. Left ventricular pressure-volume and Frank-Starling relations in endurance athletes. Implications for orthostatic tolerance and exercise performance. Circulation 84: 1016–1023, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levine BD, Lane LD, Watenpaugh DE, Gaffney FA, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG. Maximal exercise performance after adaptation to microgravity. J Appl Physiol 81: 686–694, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levine BD, Pawelczyk JA, Ertl AC, Cox JF, Zuckerman JH, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I, Ray CA, Smith ML, Iwase S, Saito M, Sugiyama Y, Mano T, Zhang R, Iwasaki K, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Jr, Cooke WH, Baisch FJ, Eckberg DL, Blomqvist CG. Human muscle sympathetic neural and haemodynamic responses to tilt following spaceflight. J Physiol 538: 331–340, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levine BD, Stray-Gundersen J. “Living high-training low”: effect of moderate-altitude acclimatization with low-altitude training on performance. J Appl Physiol 83: 102–112, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Levine BD, Zuckerman JH, Pawelczyk JA. Cardiac atrophy after bed-rest deconditioning: a nonneural mechanism for orthostatic intolerance. Circulation 96: 517–525, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ludwig DA, Convertino VA. Predicting orthostatic intolerance: physics or physiology? Aviat Space Environ Med 65: 404–411, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meck JV, Dreyer SA, Warren LE. Long-duration head-down bed rest: project overview, vital signs, and fluid balance. Aviat Space Environ Med 80: A1–A8, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mirsky I. Assessment of diastolic function: suggested methods and future considerations. Circulation 69: 836–841, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mitchell JH, Haskell WL, Raven PB. Classification of sports. J Am Coll Cardiol 24: 864–866, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.NASA The Best Workout on Earth, and in Space. http://www.sti.nasa.gov/tto/spinoff2001/ch2.html. [December 20, 2011]

- 38. Nikolic S, Yellin EL, Tamura K, Vetter H, Tamura T, Meisner JS, Frater RW. Passive properties of canine left ventricle: diastolic stiffness and restoring forces. Circ Res 62: 1210–1222, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pavy L, Traon A, Heer M, Narici MV, Rittweger J, Vernikos J. From space to Earth: advances in human physiology from 20 years of bed rest studies (1986–2006). Eur J Appl Physiol 101: 143–194, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Perhonen MA, Franco F, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG, Zerwekh JE, Peshock RM, Weatherall PT, Levine BD. Cardiac atrophy after bed rest and spaceflight. J Appl Physiol 91: 645–653, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Perhonen MA, Zuckerman JH, Levine BD. Deterioration of left ventricular chamber performance after bed rest : “cardiovascular deconditioning” or hypovolemia? Circulation 103: 1851–1857, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi SJ, South DA, Meck JV. Fludrocortisone does not prevent orthostatic hypotension in astronauts after spaceflight. Aviat Space Environ Med 75: 235–239, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shibata S, Perhonen M, Levine BD. Supine cycling plus volume loading prevent cardiovascular deconditioning during bed rest. J Appl Physiol 108: 1177–1186, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Spirito P, Pelliccia A, Proschan MA, Granata M, Spataro A, Bellone P, Caselli G, Biffi A, Vecchio C, Maron BJ. Morphology of the “athlete's heart” assessed by echocardiography in 947 elite athletes representing 27 sports. Am J Cardiol 74: 802–806, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Steinacker JM, Lormes W, Lehmann M, Altenburg D. Training of rowers before world championships. Med Sci Sports Exercise 30: 1158–1163, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tyberg JV, Taichman GC, Smith ER, Douglas NW, Smiseth OA, Keon WJ. The relationship between pericardial pressure and right atrial pressure: an intraoperative study. Circulation 73: 428–432, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Urabe Y, Mann DL, Kent RL, Nakano K, Tomanek RJ, Carabello BA, Cooper Gt. Cellular and ventricular contractile dysfunction in experimental canine mitral regurgitation. Circ Res 70: 131–147, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vernikos J, Convertino VA. Advantages and disadvantages of fludrocortisone or saline load in preventing post-spaceflight orthostatic hypotension. Acta Astronaut 33: 259–266, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Waters WW, Platts SH, Mitchell BM, Whitson PA, Meck JV. Plasma volume restoration with salt tablets and water after bed rest prevents orthostatic hypotension and changes in supine hemodynamic and endocrine variables. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H839–H847, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wolthuis RA, Bergman SA, Nicogossian AE. Physiological effects of locally applied reduced pressure in man. Physiol Rev 54: 566–595, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]