Summary

cAMP is an ancient second messenger, and is used by many organisms to regulate a wide range of cellular functions. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-complex bacteria are exceptional in that they have genes for at least 15 biochemically distinct adenylyl cyclases, the enzymes that generate cAMP. cAMP-associated gene regulation within tubercle bacilli is required for their virulence, and secretion of cAMP produced by M. tuberculosis bacteria into host macrophages disrupts the host’s immune response to infection. In this review, we discuss recent advances in our understanding of the means by which cAMP levels are controlled within mycobacteria, the importance of cAMP to M. tuberculosis during host infection, and role of cAMP in mycobacterial gene regulation. Understanding the myriad aspects of cAMP signaling in tubercle bacilli will establish new paradigms for cAMP signaling, and may contribute to new approaches for prevention and/or treatment of tuberculosis (TB) disease.

The Mycobacterial cAMP Signaling Team: Cyclases and Effector Proteins

An abundance of adenylyl cyclases

Cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate (cAMP) is one of the most universal second messengers, and it is used by bacteria, fungi and complex eukaryotes such as Homo sapiens to regulate gene expression in response to changing environmental conditions. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-complex bacteria are exceptional in the microbial world in that they encode an unusually large number of biochemically distinct adenylyl cyclases (ACs) (McCue et al., 2000). The precise number of ACs varies amongst M. tuberculosis isolates, with H37Rv containing 15 complete AC genes and one pseudogene (Rv1120c) (Table S1) (McCue et al., 2000, Shenoy et al., 2005b). Ten of these H37Rv ACs have been shown to be biochemically active so far, including: Rv0386, Rv1264, Rv1318, Rv1319, Rv1320, Rv3645, Rv1625c, Rv1647, Rv1900c, and Rv2212 (Table S2, and reviewed in (Shenoy et al., 2006)). M. tuberculosis CDC1551 has one additional putative cyclase gene (MT1360), bringing its predicted AC gene count to 17 (Shenoy et al., 2004). In contrast, many bacteria and fungi, such as Escherichia coli, Streptomyces griseus, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans have only a single AC (Cha et al., 2010, Shenoy et al., 2004, Klengel et al., 2005, Mallet et al., 2000).

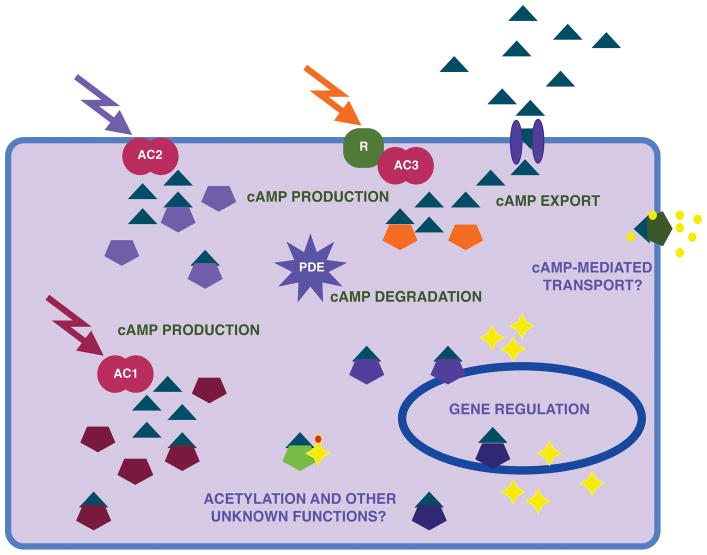

ACs are grouped into six classes, and all ACs in M. tuberculosis belong to Class III, a group that encompasses all eukaryotic and some prokaryotic ACs (Tang et al., 1998). M. tuberculosis cyclases include a diverse assortment of both soluble and membrane-associated ACs (Fig. 1, Table S2), two of which (Rv1625c and Rv2435) group with the eukaryotic cyclase lineage based on their catalytic sites (McCue et al., 2000). Rv1625c is particularly unusual in that it is a mammalian-like integral membrane protein with six transmembrane helices, with demonstrated activity in mammalian epithelial cells as well as E. coli (Guo et al., 2001, Reddy et al., 2001, McCue et al., 2000). Six M. tuberculosis ACs (Rv0891c, Rv1264, Rv1359, Rv1647, Rv2212 and Rv1625c) contain just a cyclase domain. The remaining ACs have additional domains that presumably allow them to respond to multiple signals, regulate their activity in response to environmental conditions, and/or expand their repertoire with effector function capability. Five of these multidomain ACs (Rv1318c, Rv1319c, Rv1320c, Rv2435c and Rv3645c) are membrane-associated ACs that contain HAMP (histidine kinases, adenylyl cyclases, methyl binding proteins and phosphatases) domains (Linder et al., 2004). HAMP domains are often associated with two-component signal transduction pathways and connect the sensing of extracellular environmental signals with responding intracellular signaling domains (Hulko et al., 2006). Rv2435c also has a chemotaxis receptor-like extracellular domain (McCue et al., 2000). An N-terminal auto-regulatory domain in Rv1264 is a pH responsive element that inhibits cyclase activity above pH 6.0 (Linder et al., 2002, Tews et al., 2005). An additional group of proteins (Rv0386, Rv1358 and Rv2488c) contains both ATPase and helix-turn-helix domains, while Rv1900c contains an αβ-hydrolase domain.

Figure 1.

Possible M. tuberculosis cAMP signaling pathways are illustrated. Adenyl cyclases (double circles, designated as AC1–3) can be activated by intra- or extracellular signals (arrows) to produce cAMP (represented as triangles). Some cyclases may directly respond to the activating signal, as indicated for AC1 and AC2, while intermediary receptors may transmit the signal to others, as shown for AC3, where ‘R’ is a receptor protein. cAMP is then bound to effector proteins (pentagons), which have functions in gene regulation, protein acetylation or other yet to be described activities, possibly including small molecule transport (indicated as yellow dots). cAMP can also be degraded by a phosphodiesterase (PDE), or exported, as shown. Yellow stars represent proteins, some of which are expressed from cAMP-responsive transcription factors, and the orange dot represents acetylation. Different colors are used to indicate that diversity, and likely specificity, exists at the signal, cyclase and effector levels.

A wide variety of cNMP- binding effector proteins

In silico studies also predict ten cNMP binding proteins that encompass a wide range of potential effector functions, only three of which have been functionally characterized to date (Fig. 1). Two of these proteins, Rv3676 (referred to as CRPMt, for cAMP responsive protein of M. tuberculosis) and Rv1675c (named Cmr, for cAMP and macrophage regulator), contain helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA binding domains, and belong to the CRP-FNR family of transcription factors (McCue et al., 2000). Both CRPMt and Cmr are functional as cAMP-responsive transcription factors, although only CRPMt has been shown to directly bind cAMP (Bai et al., 2007, Bai et al., 2005, Reddy et al., 2009, Stapleton et al., 2010). Both of these proteins are discussed in greater detail later in this review. A third protein from this group, encoded by Rv0998 in M. tuberculosis, was recently shown to regulate protein lysine acetylation in mycobacteria in a cAMP-responsive manner (Nambi et al., 2010). Rv0998 in M. tuberculosis and its ortholog in M. smegmatis (MSMEG_5458) each contain a cyclic nucleotide binding domain fused to a domain with similarity to the GNAT (GCN5-related N-acetyltransferases) family. Both orthologs bind cAMP, and a point mutation in MSMEG_5458 R95K abolishes its cAMP binding. This GNAT-like protein acetylates the epsilon amino group of a lysine in a Universal Stress Protein (USP) from M. smegmatis, and acetylation is enhanced in the presence of either cAMP or cGMP. The biological effects of this acetylation are not yet known.

The remaining seven predicted cNMP binding proteins (Rv0073, Rv0104, Rv2434c, Rv2564, Rv2565, Rv3239c and Rv3728) contain an assortment of putative functional domains, including those associated with transport and esterase activities (McCue et al., 2000, Shenoy et al., 2006). None of these activities has previously been associated with cAMP-mediated signal transduction in other organisms, so the study of these proteins and their roles in M. tuberculosis is expected to establish new paradigms for cAMP, and possibly cGMP, signaling.

Regulation of cAMP Levels: Production, Secretion and Degradation

Functional details of mycobacterial ACs and cNMP binding proteins have been thoroughly reviewed by Shenoy and Visweswariah (2006), so the remainder of this review will focus on the regulation and possible roles of cAMP within mycobacteria (Fig. 1). Cytoplasmic cAMP levels can be controlled at the levels of production, degradation or secretion. Although there are similarities between mycobacteria and other bacteria, the classical procaryotic cAMP paradigm established in E. coli (Botsford, 1981) does not adequately explain cAMP signaling in mycobacteria.

cAMP production: geared to the host environment

The classical catabolite repression paradigm that has been so well established in E. coli is unlikely to be a dominant feature of cAMP signaling in mycobacteria. Rather, the existing M. tuberculosis AC regulatory data suggest a complex role for cAMP signaling that is likely to be important during host infection. Cytoplasmic cAMP levels in E. coli are reduced three- to fourfold when the carbon source is ~0.2% glucose rather than glycerol (Buettner et al., 1973, Epstein et al., 1975). In contrast, a recent study shows no significant change in the cytoplasmic cAMP levels of M. bovis BCG incubated with 0.2% glucose (Bai et al., 2009), or starved for carbon (Dass et al., 2008), although cAMP levels decrease in both fast-and slow-growing mycobacteria in response to very high levels of glucose (2%) (Padh et al., 1976a, Lee, 1979). Starvation or hypoxia affected the expression of seven M. tuberculosis AC genes in microarray studies (Table S2), providing a possible first level of control over cAMP production within M. tuberculosis. However, post-translational activation of the cyclases themselves provides a second, and often dominant, level of control over cAMP production (Botsford, 1981, Tang et al., 1998). Signals identified as modulators of M. tuberculosis AC activity include pH, fatty acids and CO2 levels, which are also signals encountered by M. tuberculosis during host infection (Table S2). CO2/HCO3− provides a critical virulence regulatory signal for fungal pathogens through their single AC (Klengel et al., 2005), and it is possible that such a connection also exists in M. tuberculosis.

Macrophage passage had a significant stimulatory effect on cAMP production by mycobacteria, as cAMP levels within macrophage-passaged mycobacteria were ~50-fold higher than cAMP levels within bacteria incubated in the tissue culture medium alone (Bai et al., 2009). The specific signals controlling this cAMP increase are not known. However, cAMP production in both M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG increased when the pH of their growth medium was shifted from pH 6.7 to pH 5.5 (Gazdik et al., 2009). In contrast, addition of 0.5% albumin to a defined (Sauton’s) medium significantly reduced M. bovis BCG’s cAMP production (Bai et al., 2009). This albumin effect may also have physiological relevance during M. tuberculosis host infection, as albumin is likely to serve as a signal to different environments within the host. Surprisingly, addition of oleic acid completely overrode the inhibitory effect of albumin, restoring cAMP levels to what were observed in albumin- free media. However, cAMP produced in the presence of oleic acid in the absence of albumin was secreted into the media instead of being retained within the cells (Bai et al., 2009)(Fig. 1). This finding indicates that cAMP production and secretion are regulated separately, and identifying the signals and mechanisms underlying these two processes is essential for understanding the role of cAMP in TB pathogenesis, as discussed later in this review.

The abundance of ACs and the range of factors that affect their activity provide an opportunity for high levels of cAMP production, and it is sometimes stated that cAMP levels of in vitro grown mycobacteria exceed those of other bacteria by more than 100-fold (Shenoy et al., 2006, Barba et al., 2010, Padh et al., 1976b, Rickman et al., 2005, Stapleton et al. 2010, Nambi et al., 2010). However, variations in the conditions tested, as well as the different normalization and reporting methods that were used, make it difficult to directly compare cAMP levels across studies. Inadvertent comparison of dry weight M. smegmatis levels (520 pmol/mg) with wet weight E. coli (5.0 pmol/mg) levels in an early study (Padh et al., 1976b) has caused some confusion. A wet weight level measured for cAMP in M. smegmatis (4.5 pmol/mg) in another contemporary study (Lee, 1979) is actually quite comparable to the original E. coli wet weight value (5.0 pmol/mg) (Table S3). cAMP levels reported within E. coli (370–450 pmol/mg dry weight) and Salmonella typhiumurium (130–370 pmol/mg dry weight), are also well within the range of those reported in early studies for mycobacteria (18.7–1,000 pmol/mg dry weight) (Table S3). Nonetheless, recent measurements show wide variations in mycobacterial cytoplasmic cAMP levels (0.5 – 400 pmol/108 bacteria), depending on growth conditions, and indicate that very high levels are possible (Bai et al., 2009, Agarwal et. al., 2009, Dass et al., 2008) (Table S3). Additional studies that directly compare the levels of cAMP within the cytoplasm of tubercle bacilli relative to other bacteria are needed to better address this issue.

cAMP secretion: novel adaptation with potential for dual functions

Despite questions about the relative levels of cytoplasmic cAMP, the amount of cAMP secreted into culture medium by mycobacteria is consistently higher than the levels secreted by other bacteria (Table S3) (Botsford, 1981, Padh et al., 1976b). While differences in conditions and measurement approaches again make it impossible to directly compare these results across studies, the magnitude of differences in secreted cAMP levels across bacteria is striking and warrants further investigation. More direct measurements of cAMP levels produced and secreted by mycobacteria exposed to different environmental conditions are clearly needed to understand the modulation of cAMP levels in mycobacteria.

Perhaps most importantly, cAMP secreted by mycobacteria could have important biological effects on host cells during infections. Previous studies reported that infection with live, but not heat-killed, M. microti and M. bovis BCG elevated the cAMP levels of infected macrophages (Lowrie et al., 1979, Lowrie et al., 1975). Similar increases in cAMP levels occur within macrophages following infection with live M. tuberculosis or M. bovis BCG (Bai et al., 2009, Agarwal et al., 2009), and another recent study showed that the additional cAMP is derived from the infecting M. tuberculosis bacteria rather than the macrophages (Agarwal et al., 2009). Rv0386 was identified as the M. tuberculosis AC responsible for the elevating the cAMP levels in infected macrophages, which increased TNF-α production via the protein kinase A and cAMP response-element-binding (CREB) protein pathway (Agarwal et al., 2009). An M. tuberculosis Rv0386 knockout mutant showed decreased survival and less immunopathology than wild type bacteria during mouse infection, indicating the importance of Rv0386 for M. tuberculosis pathogenesis. Previous studies had also found that macrophages increased CREB-mediated TNF-alpha production upon infection with M. smegmatis, but not with M. avium (Roach et al., 2005, Yadav et al., 2004). M. smegmatis lacks an Rv0386 ortholog (Table S1), so there are likely to be multiple ways in which mycobacteria can stimulate the CREB pathway in macrophages. Another way M. tuberculosis may use cAMP to manipulate host immune function is by modulation of phagosome trafficking, as elevated cAMP levels in infected macrophages have been correlated with defects in phagosome-lysosome fusion (Lowrie et al., 1975, Kalamidas et al., 2006). The ability of M. tuberculosis to secrete cAMP as a common signaling molecule into host cells to subvert host defenses is an important topic and should be explored in much greater depth.

cAMP degradation: an unusual phosphodiesterase

Another intriguing possibility consistent with the high levels of cAMP secreted by mycobacteria is that secretion may be used in lieu of degradation as a primary means of modulating cAMP levels within the bacteria (Fig. 1). Despite the presence of at least ten functional ACs, only one class III cNMP phosphodiesterase (Rv0805) has been identified in M. tuberculosis (McCue et al., 2000, Shenoy et al., 2006). Moreover, Rv0805’s ability to efficiently hydrolyze 3′, 5′-cAMP appears to be modest, and reports of its activity differ among laboratories.

Biochemical studies and a crystal structure indicate that Rv0805 forms a dimer, and identified seven amino acids required for coordination of active site metals that also contribute to dimerization. Asp21, His23, Asp63 and His209 were found to coordinate Fe3+ binding, while Asn97, His169, Asp63 and His207 coordinate the Mn2+ binding (Shenoy et al., 2007). Structural studies have failed in obtaining crystals that contain 3′, 5′-cAMP, although investigators have been able to dock 3′,5′-cAMP into the Rv0805 active site of the resulting models (Podobnik et al., 2009, Shenoy et al., 2007). Overexpression of Rv0805 reduces the 3′, 5′-cAMP levels in M. smegmatis by ~30% (Shenoy et al., 2005a), and M. tuberculosis by ~50% (Agarwal et al., 2009), compared with their corresponding vector controls, and a single amino acid change (N97A) in Rv0805 abolished its 3′,5′-cAMP phosphodiesterase activity when expressed in M. smegmatis (Podobnik et al., 2009, Shenoy et al., 2005a).

However, Rv0805’s 3′, 5′-cAMP phosphodiesterase activity (Vmax =42 nmol 3′, 5′-cAMP hydrolyzed/min/mg protein; Km =153 μM) (Shenoy et al., 2005a) is significantly weaker than the 3′, 5′ phosphodiesterase activity of CpdA in E. coli, (Vmax =2.0 μmole/min/mg; Km =0.5 mM (Imamura et al., 1996), and alternate activities for Rv0805 represent an emerging story in the mycobacterial cAMP field. Rv0805 has recently been shown to have robust 2′, 3′-cAMP phosphodiesterase activity, and it is 150-fold more active in hydrolyzing 2′, 3′-cAMP than 3′, 5′-cAMP in vitro (Keppetipola et al., 2008). Purified Rv0805 did not discriminate between 2′, 3′-cAMP versus 2′,3′-cGMP in vitro, indicating some flexibility in its recognition site (Keppetipola et al., 2008). Our laboratory has also observed hydrolysis of 2′, 3′-cAMP and 2′, 3′-cGMP as the dominant in vivo phosphodiesterase activity associated with Rv0805 (Bai et al, unpublished). Amino acid substitutions H98A or H98D greatly reduced Rv0805’s 2′, 3′-cAMP phosphodiesterase activity (Keppetipola et al., 2008). The mutational studies suggest that the functional sites for Rv0805’s 2′, 3′- and 3′, 5′-cAMP phosphodiesterase activities overlap, but are not identical. Curiously, overexpression of Rv0805 in M. smegmatis also altered its cell wall permeability to hydrophobic cytotoxic compounds, and this activity was independent of Rv0805’s ability to hydrolyze cAMP (Podobnik et al., 2009). The basis of Rv0805’s effect on membrane permeability remains to be determined. Nonetheless, all evidence to date indicates that Rv0805’s function in mycobacteria is more complex than initially expected.

Biological Function: A Significant Role in Gene Regulation

Gene regulation is the most extensively studied role of cAMP signaling in mycobacteria to date, and this work has focused primarily on the cAMP-associated transcription factors CRPMt and Cmr (Fig. 1). Both proteins were initially predicted to be members of the Crp-Fnr family of transcription factors, based on in silico analyses (McCue et al., 2000). While CRPMt has been experimentally shown to conform well to this family from the biochemical and structural standpoints, Cmr’s biochemical and structural features are not well characterized. Nonetheless, both transcription factors appear to have roles in M. tuberculosis- host interactions. Deletion of the CRPMt encoding gene crp attenuates M. tuberculosis virulence in a murine model, and reduces bacterial growth rates in vitro and within macrophages (Rickman et al., 2005). This suggests that genes regulated by CRPMt are important for general metabolism as well as the virulence of this pathogen. In contrast, Cmr regulates M. tuberculosis gene expression within macrophages, but no signifcant growth defects have been observed for cmr-deleted M. tuberculosis in vitro or within macrophages (Gazdik et al., 2009). It is therefore likely that Cmr’s role in M. tuberculosis biology is more specialized that that of CRPMt.

Cmr: a cAMP and macrophage responsive regulator

cAMP-dependent regulation of gene expression in mycobaceria was first demonstrated by adding dibutyryl cAMP to M. bovis BCG cultures and assessing changes in the proteome (Gazdik et al., 2005). Dibutyryl cAMP, which crosses the bacterial cell membrane more readily than cAMP, is converted to cAMP and butyrate in the bacterial cytoplasm, causing an increase in cellular cAMP levels. Dibutyrate treatment was used in parallel as a control to confirm that the observed regulation was actually due to cAMP. In later studies, excess cAMP was generated endogenously, by expression of the catalytic domain of the Rv1264 AC, which is constitutively active in the absence of its repressor domain (Gazdik et al., 2009). Results were similar regardless of whether the cAMP was produced internally or added exogenously as dibutyryl cAMP (Gazdik et al., 2009, Gazdik et al., 2005).

Effects of cAMP on the proteome varied depending on the conditions in which the cultures were grown, indicating that the regulation was multifactorial. Two dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry (2D-GEMS) was used to identify five proteins whose expression levels were affected by cAMP (GroEL2, Rv2971, PE_PGRS6a, Mdh and Rv1265)(Gazdik et al., 2005). Expression of all five of the genes encoding these proteins was regulated by cAMP at the RNA level, although levels of GroEL2 and PE_PGRS6a were also affected at the level of post-transcriptional regulation. Cmr was found to regulate all five of these genes, as they were dysregulated in a cmr-deleted mutant (Gazdik et al., 2009). The upstream regions of three of these genes, (mdh, groEL2 and Rv1265) bound specifically to Cmr in Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSA), consistent with direct regulation of these genes by Cmr. Expression of all three of these genes was found to be regulated by the bacterium’s residence within macrophages, and this regulation was mediated by Cmr in both M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG (Gazdik et al., 2009). Low pH was also found to be a regulator of these genes in M. bovis BCG, but not in M. tuberculosis, and the reasons for this difference are not yet clear. Despite the importance of Cmr for the cAMP-dependent regulation of these genes, Cmr has not been shown to directly bind cAMP in vitro, and cAMP did not affect Cmr’s binding to any of their promoter sequences (Gazdik et al., 2009). Thus, the mechanism by which Cmr responds to cAMP levels has yet to be discovered, and it is possible that a second factor plays a facilitating role.

CRPMt: an adaptive cAMP responsive protein with classical sensibilities

CRPMt, the second cAMP responsive transcription factor in M. tuberculosis, has been far better studied than Cmr. Still, relatively little is known about CRPMt’s role in M. tuberculosis biology aside from CRPMt’s importance to M. tuberculosis pathogenesis and in vitro growth (Rickman et al., 2005). The CRP ortholog in M. bovis BCG (CRPBCG) is a fully functional transcription factor despite differing from CRPMt at two amino acid positions (L47P and E178K). CRPBCG is similar to CRPMt in its ability to bind both cAMP and DNA, although CRPBCG’s DNA binding affinity is approximately twice that of CRPMt (Bai et al., 2007, Hunt et al., 2008). These observations contradict a previous report proposing that two point mutations in crpBCG contributed to M. bovis BCG’s attenuation due to inactivation of CRPBCG ’s cAMP- and DNA-binding activities (Spreadbury et al., 2005). A recent study demonstrating that CRPBCG could overcome the virulence deficiency of an M. tuberculosis crp mutant further confirmed that CRPBCG is a functional transcription factor in vivo, and that earlier results suggesting otherwise were likely an artifact of the E. coli expression system that was used to measure transcriptional activity (Hunt et al., 2008).

Possible roles in persistence and/or reactivation tuberculosis

Rickman et. al. (2005) initially identified 16 genes whose expression was dysregulated in a crp mutant relative to wild-type M. tuberculosis in a microarray analysis. One gene in this set was shown to be directly activated by CRPMt is rpfA, which encodes a potent resuscitation promoting factor (Rpf) (Rickman et al., 2005). Rpfs are growth factors that stimulate the growth of aged M. tuberculosis cultures, and are thought to play a role in reactivation of dormant M. tuberculosis (Mukamolova et al., 2002). Regulation of rpfA by CRPMt suggests that CRPMt plays a role in persistence and/or reactivation of tuberculosis, but this is only one of many biological functions that may be regulated by CRPMt in M. tuberculosis. Recent studies predict an increasing number of biologically important genes that may be regulated by CRPMt, including those encoding proteins involved in respiration, nitrogen assimilation, fatty acid and carbohydrate metabolism, as well as the highly repetitive glycine rich PE_PGRS family of surface proteins (Akhter et al., 2008, Bai et al., 2005, Krawczyk et al., 2009). Functional studies are needed to confirm many of these CRPMt regulatory predictions and will provide insight into the roles of CRPMt in M. tuberculosis biology.

The environmental signals that affect CRPMt’s activity are not known. Bai et al (2005) identified a putative regulon for CRPMt of over 100 genes by using a combination of affinity capture and Bayesian-based computational approaches. The two largest groups of genes in this predicted CRPMt regulon overlap with hypoxia (14%) and starvation (30%) regulated genes. This is consistent with CRP’s regulatory network in E. coli, which also includes multiple overlapping stimulons that respond to signals such as starvation and anaerobiosis (Kolb et al., 1993). The hypoxia and starvation stimulons have both been proposed to play role in M. tuberculosis persistence within the host, providing further support for CRPMt’s proposed role in M. tuberculosis persistence (Bai et al., 2005, Betts et al., 2002, Sherman et al., 2001). However, the significance of this observation must be further evaluated, as microarray studies have reported a large number of hypoxia- and starvation-regulated genes in M. tuberculosis, and the proportions of these regulated genes in CRPMt regulon are similar to the proportions of these genes in overall genome.

An ortholog with its own personality

A recent study indicates that, like E. coli CRP, CRPMt can function as both a repressor and an activator. Expression of M. tuberculosis whiB1, a member of the Wbl (WhiB-like) family, was initially found to be up-regulated by CRPMt in a microarray study using a crp knockout mutant, and a CRPMt binding site was detected in whiB1’s upstream regulatory region (Rickman et al., 2005). Promoter reporter assays with native and mutated promoter sequences indicated that transcription from the native, but not the mutant, promoter was affected by cAMP levels via the direct binding with CRPMt (Agarwal et al., 2006). Another recent study found that a second CRPMt binding site in the whiB1 promoter altered CRPMt’s regulatory effect. In this study, CRPMt binding to a newly discovered downstream site inhibited whiB1 expression (Stapleton et al. 2010).

The strong resemblance of CRPMt’s DNA binding motif to that of E. coli CRP’s binding site (Agarwal et al., 2006, Bai et al., 2007, Bai et al., 2005, Hunt et al., 2008, Rickman et al., 2005, Spreadbury et al., 2005), suggests that there is functional similarity between the DNA binding domains of these orthologs despite their low level of overall sequence identity. Like E. coli CRP, CRPMt bends its target DNA upon binding, and binding of cAMP induces an allosteric change in CRPMt that enhances the affinity of CRPMt for DNA (Bai et al., 2005). Several recent studies have explored this allosteric effect and the means by which it affects CRPMt’s ability to bind DNA. Structural studies indicate that a repositioning of CRPMt’s helix-turn-helix domain occurs upon cAMP binding, and it is likely that this structural change allows the presence of the cAMP inducer to affect DNA binding. However, there is disagreement over the extent of this helix re-orientation, as attempts to establish the apo form of CRPMt have produced conflicting results. Gallagher et al (2009) reported a structure with profound asymmetry in one of the CRPMt subunits, and proposed that this asymmetry formed the basis of its inactivity in the absence of cAMP. However, another study found asymmetry only in the placement of the DNA binding domain in the absence of cAMP, and suggested that the extreme asymmetry of the first study resulted from a crystal packing effect (Kumar et al., 2010). A third study crystallized only the holo-protein, so mechanistic conclusions from this structure are dependent on resolution of the differing apo structures (Reddy et al., 2009). One significant difficulty in these studies is that the mechanism by which cAMP binding activates the highly studied E. coli CRP is still not known, as it has been difficult to obtain crystals of E. coli CRP in its apo form.

Despite their functional similarities, CRPMt and E. coli CRP also differ in significant ways that may complicate mechanistic inferences made from cross species structural studies. For example, CRPMt binds DNA strongly and specifically in the absence of cAMP, and shows a relatively modest increase in DNA binding affinity (2–10 fold) when bound with cAMP (Bai et al., 2005, Rickman et al., 2005). This contrasts with E. coli’s relative lack of specific DNA binding activity in the absence of cAMP, and is consistent with CRPMt’s relatively low affinity for cAMP compared with that of E. coli CRP (Stapleton et al., 2010). The structural effects of cAMP binding also differ for CRPMt and E. coli CRP. cAMP binding is thought to convert E. coli CRP to an more open structure, while CRPMt’s structure becomes more closed in the presence of cAMP (Bai et al., 2005, Reddy et al., 2009, Rickman et al., 2005). In these respects CRPMt better resembles the cAMP-independent E. coli CRP* protein, which is encoded by a mutated crp allele (Aiba et al., 1985, Bai et al., 2005). CRPMt also cannot substitute for CRP in E. coli, presumably due to a lack of functional interactions with E. coli’s RNA polymerase (Bai et al., 2005, Spreadbury et al., 2005). Structural studies that directly compare apo and holo forms of CRPMt with those of E. coli CRP will be needed to gain a more complete understanding of cAMP’s effects on CRPMt function, as well as to fully understand the relationship of the E. coli and mycobacterial orthologs to one another.

Defining the CRPMt regulon

CRPMt’s palindromic binding motif (C/TGTGANNNNNNTCACG/A), initially predicted by Bai et al (2005), was based on 58 predicted binding sites from the M. tuberculosis genome, using a combination of E. coli CRP binding sites and M. tuberculosis DNA sequences recovered by affinity capture using CRPMt to seed the computational analyses. Experimental validation of this binding model showed that mutation of nucleotides G2 or C15 abolished binding with CRPMt, and both positions are conserved in all predicted binding sites. Seven putative CRPMt binding sites from this sequence set located within intergenic gene regions were later tested for binding with CRPMt and CRPBCG, and six of these were found to be functional in vitro and in vivo (Bai et al., 2007). While this high rate of validation (86%) provides confidence in the prediction algorithm that was used to identify CRPMt binding sites, it is clear that the CRPMt regulon requires further refinement. For example, one DNA sequence (Rv0019c) with a high significance value in the computational model did not bind CRPMt, while another functional DNA sequence (Rv0145) was isolated by affinity capture using CRPMt but was not predicted by the computational algorithm. The presence of only one promoter (rpfA) from the microarray study further indicates that the CRPMt binding motif identified in this study requires broadening. This regulon refinement is likely to benefit from additional approaches, such as a recent in silico studies to identify a large number of possible additional CRP targets in M. tuberculosis (Fig. 2). One study used promoter sequences from the Corynebacterium glutamicum ortholog GlxR (Cg0350) regulon as seed sequences (Krawczyk et al., 2009), while another applied an entropy based algorithm to two previously predicted CRPMt regulons to develop their motif model (Akhter et al., 2008). In total, these four studies predict 145 promoters to be directly regulated by CRPMt binding. Downstream genes in operons controlled by these promoters, and indirectly regulated genes could greatly increase the number of genes whose expression is affected by CRPMt. The C. glutamicum dataset is the largest of the computational studies, and it includes all but one of the 11 putative CRPMt-regulated promoters identified in the microarray study and approximately two thirds of the regulon members predicted by each of the other two studies, along with 48 unique promoters (Krawczyk et al., 2009). In contrast, the Akhter et al (2008) study yielded the smallest dataset, more than two thirds of which overlapped with either or both of the other computationally derived datasets. Experimental validation of the sequences predicted by the in silico studies will be critical for accurately establishing the CRPMt regulon, the functions it mediates, and the environmental factors that regulate its expression.

Conclusions, future directions and unanswered questions

A tremendous amount must still be done to understand cAMP signaling in mycobacteria, but the increased rate of progress in recent years is exciting. Future investigations are particularly needed on the factors that regulate levels of cAMP within mycobacteria, the environmental signals to which Cmr and CRPMt are responding, and the biological roles of the regulons controlled by these transcription factors. Biological roles have yet to be investigated for most of the putative cNMP binding proteins, and these may establish new paradigms for cAMP signaling. The multifunctional nature of the Rv0805 phosphodiesterase and its modest activity for 3′, 5′-cAMP raise many questions. What is the role of 2′, 3′-cAMP, and how is it made? Are there other unrecognized 3′, 5′-cAMP phosphodiesterases, or do mycobacteria require less degradation of their cAMP than other better studied organisms because of their high rates of cAMP secretion? The high levels of cAMP secreted by mycobacteria also have broad biological implications because they provide a mechanism by which mycobacteria can communicate with their host cells, and possibly other mycobacteria. The importance of cAMP secretion by tubercle bacilli within host macrophages has already been shown to have immunomodulatory effects, and this will likely be an area of fruitful future investigation. However, signaling specificity may be one of the biggest questions raised by the large number of ACs in M. tuberculosis, and it remains to be determined how cAMP can mediate specific regulatory outcomes depending on which cyclase produces it. Defining the myriad roles of cAMP signaling in mycobacteria promises to provide new insights into the biology of signal transduction in TB pathogenesis, a new guise for an ancient messenger.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported by grants AI4565801 and AI063499 from the National Institutes of Health.

References cited

- Agarwal N, Lamichhane G, Gupta R, Nolan S, Bishai WR. Cyclic AMP intoxication of macrophages by a Mycobacterium tuberculosis adenylate cyclase. Nature. 2009;460:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature08123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal N, Raghunand TR, Bishai WR. Regulation of the expression of whiB1 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: role of cAMP receptor protein. Microbiology. 2006;152:2749–2756. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28924-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiba H, Nakamura T, Mitani H, Mori H. Mutations that alter the allosteric nature of cAMP receptor protein of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1985;4:3329–3332. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04084.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter Y, Yellaboina S, Farhana A, Ranjan A, Ahmed N, Hasnain SE. Genome scale portrait of cAMP-receptor protein (CRP) regulons in mycobacteria points to their role in pathogenesis. Gene. 2008;407:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Gazdik MA, Schaak DD, McDonough KA. The Mycobacterium bovis BCG cyclic AMP receptor-like Protein is a functional DNA binding protein in vitro and in vivo, but its activity differs from that of its M. tuberculosis ortholog, Rv3676. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5509–5517. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00658-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, McCue LA, McDonough KA. Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3676 (CRPMt), a cyclic AMP receptor protein-like DNA binding protein. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7795–7804. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7795-7804.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Schaak DD, McDonough KA. cAMP levels within Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG increase upon infection of macrophages. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2009;55:68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00500.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barba J, Alvarez AH, Flores-Valdez MA. Modulation of cAMP metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its effect on host infection. Tuberculosis. 2010;90:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts JC, Lukey PT, Robb LC, McAdam RA, Duncan K. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:717–731. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botsford JL. Cyclic nucleotides in procaryotes. Microbiol Rev. 1981;45:620–642. doi: 10.1128/mr.45.4.620-642.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner MJ, Spitz E, Rickenberg HV. Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate in Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology. 1973;114:1068–1073. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.3.1068-1073.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha PH, Park SY, Moon MW, Subhadra B, Oh TK, Kim E, et al. Characterization of an adenylate cyclase gene (cyaB) deletion mutant of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85:1061–1068. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dass BK, Sharma R, Shenoy AR, Mattoo R, Visweswariah SS. Cyclic AMP in mycobacteria: characterization and functional role of the Rv1647 ortholog in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Journal of Bacteriology. 2008;190:3824–3834. doi: 10.1128/JB.00138-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein W, Rothman-Denes LB, Hesse J. Adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate as mediator of catabolite repression in Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1975;72:2300–2304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.6.2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher DT, Smith N, Kim SK, Robinson H, Reddy PT. Profound asymmetry in the structure of the cAMP-free cAMP Receptor Protein (CRP) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:8228–8232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800215200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdik MA, Bai G, Wu Y, McDonough KA. Rv1675c(cmr) regulates intramacrophage and cyclic AMP-induced gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-complex mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:434–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdik MA, McDonough KA. Identification of cyclic AMP-regulated genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria under low-oxygen conditions. Journal of Bacteriology. 2005;187:2681–2692. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.8.2681-2692.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo YL, Seebacher T, Kurz U, Linder JU, Schultz JE. Adenylyl cyclase Rv 1625c of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a progenitor of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. EMBO J. 2001;20:3667–3675. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.14.3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulko M, Berndt F, Gruber M, Linder JU, Truffault V, Schultz A, et al. The HAMP domain structure implies helix rotation in transmembrane signaling. Cell. 2006;126:929–940. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt DM, Saldanha JW, Brennan JF, Benjamin P, Strom M, Cole JA, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms that cause structural changes in the cyclic AMP receptor protein transcriptional regulator of the tuberculosis vaccine strain Mycobacterium bovis BCG alter global gene expression without attenuating growth. Infection and Immunity. 2008;76:2227–2234. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01410-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura R, Yamanaka K, Ogura T, Hiraga S, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Niki H. Identification of the cpdA gene encoding cyclic 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate phosphodiesterase in Escherichia coli. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:25423–25429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamidas SA, Kuehnel MP, Peyron P, Rybin V, Rauch S, Kotoulas OB, et al. cAMP synthesis and degradation by phagosomes regulate actin assembly and fusion events: consequences for mycobacteria. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3686–3694. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppetipola N, Shuman S. A phosphate-binding histidine of binuclear metallophosphodiesterase enzymes is a determinant of 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:30942–30949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805064200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klengel T, Liang WJ, Chaloupka J, Ruoff C, Schroppel K, Naglik JR, et al. Fungal adenylyl cyclase integrates CO2 sensing with cAMP signaling and virulence. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2021–2026. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb A, Busby S, Buc H, Garges S, Adhya S. Transcriptional regulation by cAMP and its receptor protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:749–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk J, Kohl TA, Goesmann A, Kalinowski J, Baumbach J. From Corynebacterium glutamicum to Mycobacterium tuberculosis--towards transfers of gene regulatory networks and integrated data analyses with MycoRegNet. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37:e97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Joshi DC, Akif M, Akhter Y, Hasnain SE, Mande SC. Mapping conformational transitions in cyclic AMP receptor protein: crystal structure and normal-mode analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis apo-cAMP receptor protein. Biophys J. 2010;98:305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH. Metabolism of cyclic AMP in non-pathogenic Mycobacterium smegmatis. Archives of Microbiology. 1979;120:35–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00413269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder JU, Hammer A, Schultz JE. The effect of HAMP domains on class IIIb adenylyl cyclases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:2446–2451. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder JU, Schultz A, Schultz JE. Adenylyl cyclase Rv1264 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis has an autoinhibitory N-terminal domain. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:15271–15276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrie DB, Aber VR, Jackett PS. Phagosome-lysosome fusion and cyclic adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium microti, Mycobacterium bovis BCG or Mycobacterium lepraemurium. Journal of General Microbiology. 1979;110:431–441. doi: 10.1099/00221287-110-2-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrie DB, Jackett PS, Ratcliffe NA. Mycobacterium microti may protect itself from intracellular destruction by releasing cyclic AMP into phagosomes. Nature. 1975;254:600–602. doi: 10.1038/254600a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet L, Renault G, Jacquet M. Functional cloning of the adenylate cyclase gene of Candida albicans in Saccharomyces cerevisiae within a genomic fragment containing five other genes, including homologues of CHS6 and SAP185. Yeast. 2000;16:959–966. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(200007)16:10<959::AID-YEA592>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue LA, McDonough KA, Lawrence CE. Functional classification of cNMP-binding proteins and nucleotide cyclases with implications for novel regulatory pathways in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Research. 2000;10:204–219. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamolova GV, Turapov OA, Young DI, Kaprelyants AS, Kell DB, Young M. A family of autocrine growth factors in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecular Microbiology. 2002;46:623–635. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambi S, Basu N, Visweswariah SS. cAMP-regulated protein lysine acetylases in mycobacteria. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:24313–24323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.118398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padh H, Venkitasubramanian TA. Adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate in Mycobacterium phlei and Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra. Microbios. 1976a;16:183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padh H, Venkitasubramanian TA. Cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate in mycobacteria. Indian Journal of Biochemistry & Biophysics. 1976b;13:413–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podobnik M, Tyagi R, Matange N, Dermol U, Gupta AK, Mattoo R, et al. A mycobacterial cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase that moonlights as a modifier of cell wall permeability. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:32846–32857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MC, Palaninathan SK, Bruning JB, Thurman C, Smith D, Sacchettini JC. Structural insights into the mechanism of the allosteric transitions of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cAMP receptor protein. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:36581–36591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SK, Kamireddi M, Dhanireddy K, Young L, Davis A, Reddy PT. Eukaryotic-like adenylyl cyclases in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv: cloning and characterization. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:35141–35149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickman L, Scott C, Hunt DM, Hutchinson T, Menendez MC, Whalan R, et al. A member of the cAMP receptor protein family of transcription regulators in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for virulence in mice and controls transcription of the rpfA gene coding for a resuscitation promoting factor. Molecular Microbiology. 2005;56:1274–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach SK, Lee SB, Schorey JS. Differential activation of the transcription factor cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) in macrophages following infection with pathogenic and nonpathogenic mycobacteria and role for CREB in tumor necrosis factor alpha production. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73:514–522. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.514-522.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Capuder M, Draskovic P, Lamba D, Visweswariah SS, Podobnik M. Structural and biochemical analysis of the Rv0805 cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;365:211–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Sivakumar K, Krupa A, Srinivasan N, Visweswariah SS. A survey of nucleotide cyclases in actinobacteria: unique domain organization and expansion of the class III cyclase family in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Comp Funct Genomics. 2004;5:17–38. doi: 10.1002/cfg.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Sreenath N, Podobnik M, Kovacevic M, Visweswariah SS. The Rv0805 gene from Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes a 3′,5′-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase: biochemical and mutational analysis. Biochemistry. 2005a;44:15695–15704. doi: 10.1021/bi0512391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Srinivas A, Mahalingam M, Visweswariah SS. An adenylyl cyclase pseudogene in Mycobacterium tuberculosis has a functional ortholog in Mycobacterium avium. Biochimie. 2005b;87:557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Visweswariah SS. New messages from old messengers: cAMP and mycobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2006;14:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DR, Voskuil M, Schnappinger D, Liao R, Harrell MI, Schoolnik GK. Regulation of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis hypoxic response gene encoding alpha -crystallin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7534–7539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121172498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreadbury CL, Pallen MJ, Overton T, Behr MA, Mostowy S, Spiro S, et al. Point mutations in the DNA- and cNMP-binding domains of the homologue of the cAMP receptor protein (CRP) in Mycobacterium bovis BCG: implications for the inactivation of a global regulator and strain attenuation. Microbiology. 2005;151:547–556. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton M, Haq I, Hunt DM, Arnvig KB, Artymiuk PJ, Buxton RS, Green J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis cAMP receptor protein (Rv3676) differs from the Escherichia coli paradigm in its cAMP binding and DNA binding properties and transcription activation properties. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7016–7027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang WJ, Yan S, Drum CL. Class III adenylyl cyclases: regulation and underlying mechanisms. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1998;32:137–151. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(98)80009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tews I, Findeisen F, Sinning I, Schultz A, Schultz JE, Linder JU. The structure of a pH-sensing mycobacterial adenylyl cyclase holoenzyme. Science. 2005;308:1020–1023. doi: 10.1126/science.1107642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav M, Roach SK, Schorey JS. Increased mitogen-activated protein kinase activity and TNF-alpha production associated with Mycobacterium smegmatis- but not Mycobacterium avium-infected macrophages requires prolonged stimulation of the calmodulin/calmodulin kinase and cyclic AMP/protein kinase A pathways. J Immunol. 2004;172:5588–5597. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.