Summary

Pro-inflammatory caspases play important roles in innate immunity. Much attention has focused on caspase-1, which acts to eliminate pathogens by obliterating their replicative niches as well as alerting the host to their presence. Emerging data now sheds light on the lesser-studied pro-inflammatory caspase-11 in the combat between host and pathogen. With new tools available, researchers are now further elucidating the mechanisms by which caspase-11 contributes to host defense. Here, we review the emerging understanding of caspase-11 functions and mechanisms of activation, and discuss implications for human disease.

Paradigms of caspase regulation

Caspases are a family of cysteine-dependent proteases that play a major role in various aspects of host physiology including development, homeostasis, and host defense. The pro-inflammatory caspases, which constitute a subset of this family of cysteine proteases, have primary functions in innate immune responses, and include caspase-1, -11 (also referred to as murine ich-3, and in humans, caspase-4 and -5 as discussed later in this review) and -12. Upon activation, these pro-inflammatory caspases cleave as yet unidentified substrates to induce pore formation in host cell membranes and a specialized form of cell death called pyroptosis (Bergsbaken et al., 2009). Importantly, pyroptotic cell death is distinct from apoptosis, which activates a completely different set of caspases to induce a non-inflammatory mode of cell death. In contrast, apoptosis is triggered by the initiator caspases, caspase-2, -8, -9, and -10, which subsequently activate the executioner caspases, caspase-3, -6, and -7. These executioner caspases then directly cleave cellular proteins, prompting the packaging of cellular contents into membrane-bound vesicles, which are then degraded (MacKenzie and Clark, 2012).

Despite their distinct downstream consequences, caspases follow a similar protein structural organization. They are initially expressed as inactive zymogens containing a variable N-terminal pro-domain linked to a conserved large and small sub-domain. Caspase-1, -2, -4, -9, and -11 have particularly long pro-domains that contain either death effector domains (DED) or caspase recruitment domains (CARD), which are thought to confer specificity of activation since they mediate interactions with other DED- and CARD-containing adaptor proteins. Association with these adaptor proteins likely nucleates caspases, increasing their local concentration. This nucleation can favor activation through dimerization, which has been reported for the initiator caspases (Chang et al., 2003; Yang et al., 1998). Upon activation, auto-proteolytic cleavage of the pro-domain and the linker region between the large (p20) and small (p10) sub-domains can occur. However, the executioner caspases must be cleaved directly by the initiator caspases. Cleavage then enables the formation and stabilization of the active caspase tetramer consisting of two p10 and p20 subunits (MacKenzie and Clark, 2012). It is important to note that cleavage is not absolutely necessary for inducing caspase-1, -8, or -9-dependent cell death (Boatright et al., 2003; Broz et al., 2010b). However, auto-proteolytic cleavage is required for caspase-1-mediated IL-1β maturation (Broz et al., 2010b). The mechanisms that direct caspase-1-mediated cell death versus cytokine maturation remain to be determined. For a more comprehensive review on general mechanisms of caspase activation, see Boatright and Salvesen (2003).

Elucidating the mechanisms of the pro-inflammatory caspases is important because they are absolutely required for clearance of some pathogens in the host. The pro-inflammatory caspases serve two main functions. First, these caspases induce a pyroptotic cell death that eliminates the replicative niche of intracellular pathogens, and second, they process pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β and IL-18), which upon maturation, are released extracellularly along with danger signals (e.g. IL-1α and High mobility group box 1, HMGB1) to alert the host of pathogen invasion (Franchi et al., 2012). It is currently unclear if the release of these cytokines and danger signals is a direct result of pyroptosis-mediated pore formation or through unidentified secretory pathways (Rubartelli et al., 1990; Verhoef et al., 2005; Wewers, 2004).

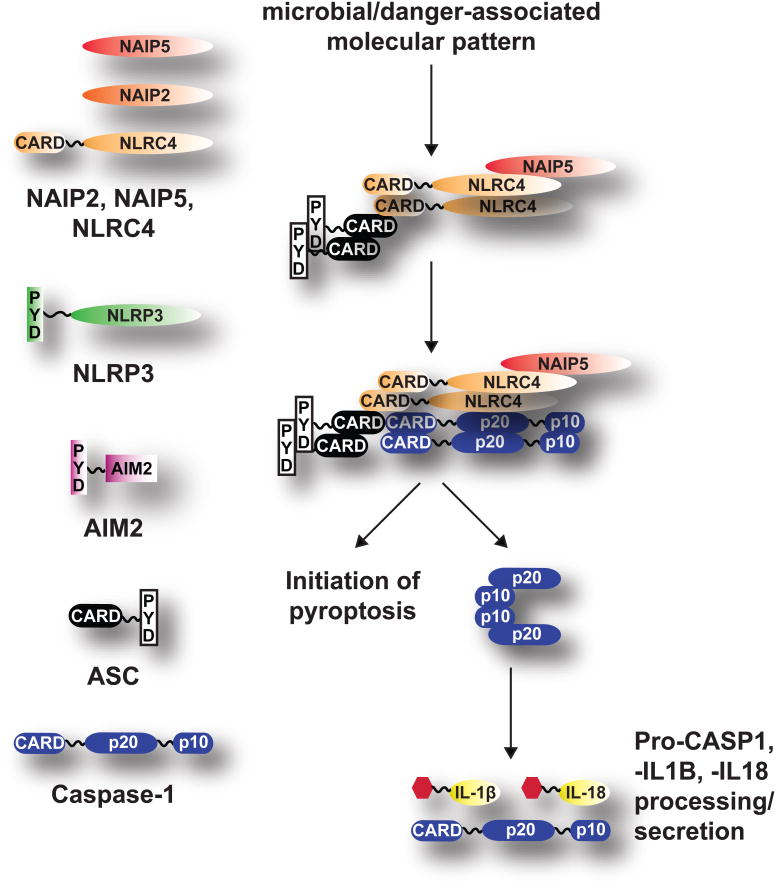

Pro-inflammatory caspases must be tightly regulated in order to avoid aberrant activation and host tissue damage. The current model for pro-inflammatory caspase activation follows that of the non-inflammatory caspases. Specifically, caspase-1 nucleation occurs upon activation of cytosolic microbial- and danger- associated molecular pattern recognition receptors that contain CARD and PYD domains, including the Neuronal apoptosis inhibitor proteins (NAIPs), Nucleotide-binding oligomerization (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs, e.g. NLRP3 and NLRC4), and the PYHIN (AIM2) families of proteins. Upon detection of their respective agonists, these receptors recruit Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC) through its PYD and CARD domains. The CARD and PYD protein-interacting domains also promote oligomerization of ASC, leading to the recruitment of caspase-1. A macromolecular complex called the inflammasome is thus formed (see Figure 1). Inflammasome formation is believed to provide a platform to promote the formation and stabilization of the caspase-1 p10/p20 tetramer that is required for pro-inflammatory cytokine maturation (pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18). The mature forms of caspase-1 and the cytokines are then released outside of the cell to engage a systemic inflammatory response (Franchi et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Model for caspase-1 activation. Different cytosolic receptors are engaged upon detection of microbial- and danger-associated molecular patterns. ASC then associates with these receptors through its PYD and CARD domains. Recruitment of caspase-1 leads to formation of the inflammasome. Caspase-1 is activated to induce pyroptosis. Further auto-proteolytic cleavage of caspase-1 leads to formation of the catalytic tetramer required for maturation of other caspase-1 proteins as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines, e.g. pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18.

Caspase-11 contributes to host inflammatory responses

Although most of the work on pro-inflammatory caspases has focused on caspase-1, recently, caspase-11 has taken center stage. This has stemmed from the availability of mice deficient specifically for either Casp1 or Casp11 (Kayagaki et al., 2011). Previous studies were performed with mice deficient for both Casp1 and Casp11 because the embryonic stem cells used to generate the original Casp1-/- mouse strains were isolated from the murine 129 strain that contains a naturally occurring 5-base pair deletion within the Casp11 locus (Kayagaki et al., 2011). Recombination and segregation of the nonfunctional Casp11 gene away from the Casp1-/- locus is nearly impossible because Casp1 and Casp11 occur only ∼1500 bp apart on chromosome 9 in mice. Researchers are now actively examining whether the lack of caspase-11 has contributed to any of the previously reported Casp1-/- phenotypes.

Caspase-11 was identified almost 17 years ago in a mouse cDNA library screen for homologs of human caspase-1, though the mechanisms of caspase-11 in the host response to pathogen invasion remain poorly understood (Wang et al., 1996). Initial characterization of caspase-11 in COS and immortalized EF cells demonstrated that it plays a direct role in cell death and enhances pro-IL-1β processing in the presence of caspase-1 (Wang et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1998). Additionally, the authors observed bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of caspase-11 expression in several mouse tissues, particularly in the spleen (Wang et al., 1996). However, researchers did not observe LPS-stimulated Casp11 expression in the previous murine 129 Casp1-/-mice (detailed above), halting further studies aimed at elucidating any potential crosstalk between the two pro-inflammatory caspases. Instead, studies focused on dissecting the independent role of caspase-11 using a LPS-induced septic shock model since Casp11-/- mice are more resistant to lethal doses of LPS compared to wild-type mice (Wang et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1998). Upon administration of a lethal dose of LPS, caspase-11 activation promotes caspase-3 activity independent of caspase-1 (Kang et al., 2002). However, Casp3-/- mice exhibit LPS-induced mortality that is indistinguishable from wild-type mice. In addition, Il1b-/-/Il18-/- mice are also susceptible to lethal doses of LPS while Nlrp3-/- and Asc-/- mice are more resistant compared to wild-type mice. This suggests that while NLRP3 and ASC can engage CASP1 to process pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, these cytokines are dispensable in the LPS-induced septic shock model (Lamkanfi et al., 2010; Mariathasan et al., 2004; Mariathasan et al., 2006). Interestingly, the administration of neutralizing antibodies against the alarmin, HMGB1, enhances survival in the LPS-induced septic shock model (Lamkanfi et al., 2010). Together, these studies suggest that LPS-induced mortality is predominantly due to caspase-11-dependent pyroptotic release of HMGB1 and potentially other sepsis mediators.

More recently, several research groups have examined how caspase-11 contributes to host defenses against pathogen invasion. A variety of known inflammasome activators were added to LPS-primed and unprimed bone-marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs), which led to the identification of a specific subset of NLRP3-engaging stimuli that also activate caspase-11-dependent cell death and IL-1β secretion, including cholera toxin B and several Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Citrobacter rodentium, Salmonella typhimurium, and Legionella pneumophila (Aachoui et al., 2013; Broz et al., 2012; Case et al., 2013; Kayagaki et al., 2011; Rathinam et al., 2012). Strikingly, caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis occurs independently of the known inflammasome mediators, NLRC4, NLRP3, and ASC (Aachoui et al., 2013; Broz et al., 2012; Case et al., 2013; Kayagaki et al., 2011). This is particularly notable because caspase-1-mediated cell death, in contrast, requires at least one adaptor protein to initiate cell death (e.g. NLRC4 and AIM2/ASC) (Broz et al., 2010b). Also, caspase-11 is required for the release of the alarmins, IL-1α and HMGB1 (Kayagaki et al., 2011). However, this may not be surprising since these alarmins do not contain signal peptides and their release from cells appears to be correlated to the loss of cell membrane integrity irrespective of whether caspase-1 or caspase-11 is activated (Lamkanfi et al., 2010; Watanabe and Kobayashi, 1994).

In contrast to cell death, the role of caspase-11 in pro-IL-18 and pro-IL-1β maturation is dependent on NLRP3/ASC/CASP1 inflammasomes. First, upon infection with S.typhimurium, the level of pro-IL-1β maturation in BMDMs is reduced in the absence of caspase-11 and completely abrogated in the absence of caspase-1 (Broz et al., 2012). Second, Casp1-/- and Casp11-/- BMDMS stimulated with LPS in addition to either cholera toxin B or E.coli failed to secrete mature IL-1β (Kayagaki et al., 2011). Taken together, it is likely that caspase-11 promotes caspase-1-mediated responses by engaging NLRP3/ASC inflammasomes. Furthermore, upon exposure of BMDMs to stimuli that engage both NLRP3 and NAIP/NLRC4, NAIP/NLRC4/CASP1 inflammasome responses dominate. As a result, caspase-11-dependent cell death and IL-1β secretion can only be detected in vitro in the absence of a NAIP/NLRC4 stimulus, e.g. flagellin (Aachoui et al., 2013; Broz et al., 2012; Case et al., 2013). Thus, it is plausible that caspase-11 functions as a backup measure for macrophages to ensure that cell death and cytokine maturation is initiated, particularly when potent caspase-1 activation/stimulation is abrogated or dampened, which is an immune evasive tactic engaged by many pathogens (Taxman et al., 2010).

Signaling pathways in caspase-11 activation

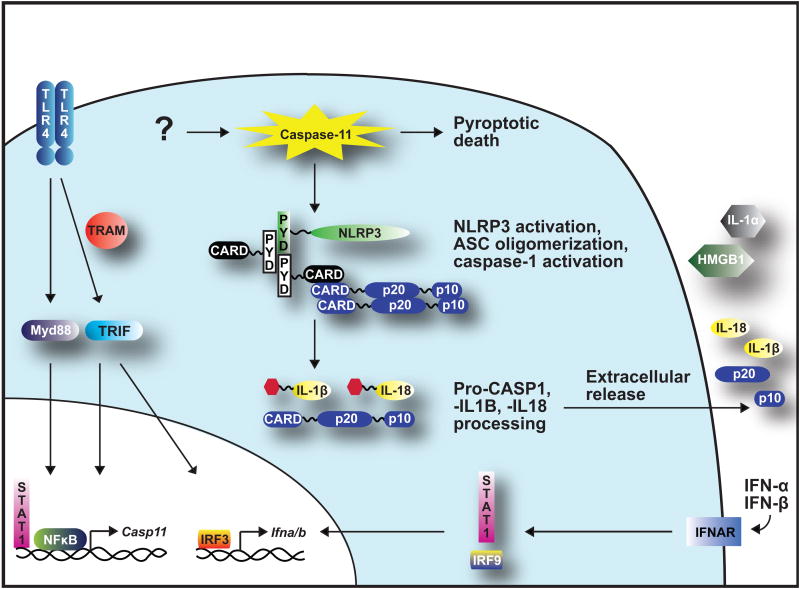

Recent studies focusing on mechanisms of caspase-11 activation have shed light on the signaling pathways involved. Consistent with previous findings, caspase-11 expression is induced upon TLR4 recognition of LPS (Wang et al., 1996). TLR4 recruits TIR-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing IFN-β (TRIF) and TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM), resulting in the activation of Interferon regulatory transcription factor 3 (IRF3), which leads to type-I interferon, IFN-α and -β, expression (Broz et al., 2012; Gurung et al., 2012; Rathinam et al., 2012). The TLR adaptor, Myd88, also appears to contribute to this in some cases (Broz et al., 2012; Case et al., 2013). Autocrine or paracrine engagement of Interferon α/β receptor (IFNAR) then stimulates STAT1 and IRF9 signaling pathways that also contribute to the up-regulation of Casp11 expression and activation (see Figure 2) (Broz et al., 2012; Rathinam et al., 2012).

Figure 2.

Caspase-11-activating pathways. LPS engagement of TLR4 activates Myd88 and TRAM/TRIF signaling pathways that contribute to the transcriptional up-regulation of Casp11 and Ifna/b. IFN-α and -β can engage IFNAR, activating signaling pathways that also lead to Casp11 transcription. Once activated in the cytosol, caspase-11 initiates pyroptosis. Engagement of NLRP3 and ASC promotes caspase-1 inflammasome activity that leads to maturation of pro-caspase-1, pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18. Figure modified from (Ng et al., 2013).

Although the signaling pathways involved in inducing Casp11 expression are clear, there are some differences between the proposed models for its activation and function. First, while it is accepted that IFN-β stimulation is necessary for caspase-11-mediated cell death, there is some dispute as to whether this stimulation alone is sufficient (Broz et al., 2012; Rathinam et al., 2012). LPS, IFN-β, and IFN-γ are all certainly capable of inducing Casp11 expression since the Casp11 promoter contains consensus binding sites for both NFκB and STAT1 transcription factors that are downstream of the Myd88, TRIF, and IFNAR signaling pathways (Schauvliege et al., 2002). Consistent with this, Rathinam et al., report that exogenous addition of these stimuli to immortalized BMDMs induces Casp11 gene expression, and that expression is sufficient for activation since exposure to IFN-β and IFN-γ alone leads to caspase-11-dependent cell death. In contrast, Broz et al. demonstrate that caspase-11-dependent cell death can only occur upon stimulation with IFN-β in conjunction with S.typhimurium infection in primary BMDMs (Broz et al., 2012). However, this distinction may be attributed to the use of immortalized macrophages, which contain replication-proficient retroviruses used in the immortalization process (unpublished observation). Still, the issue of sufficiency has broader implications for our understanding of caspase regulation and begs the question of whether a single extrinsic signal can directly induce caspase-mediated cell death, or whether cells employ a two-signal model to safeguard against unintentional caspase activation.

The second inconsistency centers on whether caspase-11 is required for ASC oligomerization and thus, for NLRP3/ASC inflammasome assembly. Immunofluorescent microscopy studies have shown that upon S.typhimurium infection of primary BMDMs, ASC oligomerization (through visualization of the “ASC speck”) occurs first, followed by caspase-1 and pro-IL-1β recruitment (Broz et al., 2010a). Extending this analysis, Broz et al. recently demonstrated that caspase-11 is required for ASC speck formation in NLRP3 inflammasomes, thus placing caspase-11 early in the sequence of the NLRP3 inflammasome assembly cascade (Broz et al., 2012). In contrast, Rathinam et al. conclude that caspase-11 is not required for ASC oligomerization upon NLRP3 activation in immortalized BMDMs using a biochemical assay to measure ASC dimer and oligomer formation. The authors suggest an alternative model in which caspase-1 activation is enhanced through heterodimerization with caspase-11 (Rathinam et al., 2012). It is important to note that the nature of these two assays is starkly different since immunofluorescent microscopy examines the spatial organization of proteins within intact cells as opposed to molecular assemblies of proteins isolated from whole cell lysates. Although both conclusions are consistent with the reported functions of caspase-11 in promoting caspase-1-mediated cell death and pro-IL-1β maturation, they have disparate ramifications on our understanding of NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and function (Case et al., 2013; Kayagaki et al., 2011; Wang et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1998). Thus, further investigation will be required to distinguish between these two models.

What is the caspase-11 activator?

If caspase-11 activation operates on a two-signal model, the nature of the second signal remains elusive. Interestingly, a recent report demonstrates that escape of mutant Legionella or Salmonella from endosomal vacuoles upon infection of LPS-primed BMDMs specifically triggers caspase-11-dependent cell death and IL-1β secretion whereas the wild-type bacteria that remain within vacuoles do not. Although the impact of the absence of these bacterial effectors on host defense is unclear, infection with wild-type Burkholderia exhibited similar phenotypes. Taken together, the authors propose that vacuolar lysis may be a potential source of the second signal (Aachoui et al., 2013). Consistent with this, the endosomal enzyme, cathepsin B, was previously isolated from lysosomal fractions of murine liver lysates and shown to induce caspase-11 processing and activation (Schotte et al., 1998).

However, the vacuolar lysis hypothesis contradicts two observations. First, many of the other Gram-negative bacteria implicated in caspase-11 activation (E.coli, C.rodentium, and S.typhimurium) do not induce vacuolar lysis (Broz et al., 2012; Kayagaki et al., 2011). Second, the Gram-negative Francisella tularensis, which escapes phagosomes to replicate in the cytosol of host cells, does not appear to induce caspase-11-dependent IL-1β secretion upon infection of BMDMs (Kayagaki et al., 2011). Although F. tularensis normally engages TLR2, the pre-stimulation of BMDMs with LPS should have been sufficient to induce the first signal for caspase-11 function, the expression of Casp11. It is possible that caspase-11-dependent responses could not be detected during F. tularensis infection due to concomitant AIM2/CASP1 inflammasome activation, which may dominate caspase-11 responses similar to what is observed with NAIP/NLRC4/CASP1 inflammasomes (Broz et al., 2012; Case et al., 2013). Considering this, it would be interesting to determine whether infection of LPS-stimulated BMDMs with Listeria monocytogenes, a Gram-positive bacterium that escapes the phagosome, can activate caspase-11. This experiment not only tests the vacuolar lysis hypothesis but may also provide a clue to another possible signal for caspase-11 activation. Intriguingly, in the context of bacterial infections, caspase-11 activation has only been observed in BMDMs infected specifically with Gram-negative bacteria (Aachoui et al., 2013; Broz et al., 2012; Case et al., 2013; Kayagaki et al., 2011; Rathinam et al., 2012). The notion that caspase-11 activation may be due to some component of Gram-negative bacteria is also consistent with a previous report in which caspase-11 did not contribute to the host defense against L. monocytogenes (Mueller et al., 2002).

Various toxins have also been tested for caspase-11-activating functions in BMDMs pre-stimulated with LPS. To date, the only known caspase-11-activating toxin is cholera toxin B (Kayagaki et al., 2011). While cholera toxin B does not induce endosomal lysis, it reaches the host cytosol by associating with the ganglioside receptor GM1, enabling trafficking from the plasma membrane to the trans-Golgi and ER before retro-translocating across the ER membrane (Reig and van der Goot, 2006). Two other toxins have been tested for the ability to activate caspase-11. This includes the adenylate cyclase and listerolysin O toxins, which, despite their pore-forming capabilities, do not activate caspase-11 (Kayagaki et al., 2011). However, the different modes of action of cholera toxin B, adenylate cyclase, and listerolysin O may provide a hint into the mechanism of caspase-11 activation. Adenylate cyclase penetrates directly through the plasma membrane and thus, does not involve endosomal acidification (Reig and van der Goot, 2006). In contrast, listerolysin O induces pore formation in vacuolar membranes upon pH reduction. Taken together, these results suggest that perhaps the caspase-11 activator involves a component of membrane trafficking that is disrupted during pathogen invasion rather than vacuolar lysis itself. Furthermore, differences in S.typhimurium- and L.pneumophila-mediated membrane trafficking may explain why caspase-11 induces cell death within four hours of L.pneumophila infection as compared to eight hours with S.typhimurium (Haraga et al., 2008; Hubber and Roy, 2010).

Cell death-independent functions of caspase-11

In addition to inducing cell death, caspase-11 has also been implicated in modulating actin dynamics and cell migration (Li et al., 2007). Caspase-11 cooperatively interacts with actin-interacting protein (Aip1) to activate cofilin-dependent actin depolymerization leading to increased splenocyte migration (Li et al., 2007). Caspase-11-mediated actin depolymerization appears to be independent of its enzymatic activity (Li et al., 2007). Thus, LPS and IFN-α/β/γ stimulation of caspase-11 expression may be sufficient for increasing cell migration towards chemokines released at the site of infection as part of the defense against pathogen invasion. Reports of caspase-11 promoting L.pneumophila trafficking to the lysosome within BMDMs may also be due to modulation of actin dynamics (Akhter et al., 2012; Santic et al., 2005). However, it is not clear if these observations can be attributed to the concomitant activation of cell death since L.pneumophila trafficking in Casp11-C254G enzymatic mutant BMDMs was not examined (Akhter et al., 2012). The authors also conclude that caspase-11 is required for cofilin phosphorylation. It is possible that cells induce a compensatory response to modulate cofilin levels and cofilin phosphorylation states in order to maintain active actin dynamics (Li et al., 2007).

Caspase-11 function in humans

It is critical to understand the mechanisms of caspase-11 activation, particularly due to its role in regulating NLRP3, a central player in many inflammatory diseases in humans (McIlwain et al., 2013). There are two possible human homologs of murine caspase-11, caspase-4 and -5. Murine CASP11 exhibits 60% and 55% identity with human CASP4 and CASP5, respectively. The pro-domains of CASP4 and CASP5 exhibit 84-86% identity to the pro-domain of murine CASP11 while the catalytic C-terminal p20 and p10 domains of the human homologs exhibit 85-86% identity to that found in mice. Additionally, CASP4 and CASP5 share 74% identity with each other, although no functional complementation tests have been reported. Analysis of expression levels in different tissues indicates that human Casp4 expression is more widely distributed than Casp5 (Lin et al., 2000). In unstimulated cells, the highest expression levels of murine Casp11 are observed in spleens while Casp4 is highly expressed in placental and lung tissues and Casp5 in the colon (Lin et al., 2000; Wang et al., 1996). Similar to murine Casp11, transcription of Casp4 and Casp5 is increased upon stimulation with LPS or IFN-γ depending on the cell line examined (Lin et al., 2000). Moreover, interactions of both CASP4 and CASP5 with CASP1 have been reported as well as contributions to caspase-1 and pro-IL-1β maturation in vitro in several cell lines (Martinon et al., 2002; Nour et al., 2009; Sollberger et al., 2012). Based on these studies, it is not clear which is the functional human homolog of murine CASP11, though this may simply be a matter of tissue specificity and expression levels therein.

Interestingly, several studies implicate a role for human caspase-4 and murine caspase-12 in ER stress-induced cell death. These caspases undergo auto-proteolytic cleavage in response to tunicamycin and thapsigargin, which inhibit N-linked glycosylation and deplete calcium stores in the ER, respectively (Hitomi et al., 2004; Nakagawa et al., 2000). Furthermore, immuno-staining and immuno-EM reveals caspase-4 localization to the ER while caspase-1 localization to membranes has also been reported (Hitomi et al., 2004; Nour et al., 2009; Singer et al., 1995). However, the role of murine caspase-12 in ER stress-induced cell death is unclear because the Casp12-/- mice used in this study were also generated using embryonic cells from the murine 129 strain that is deficient for caspase-11 (Nakagawa et al., 2000). Because the probability of recombination between the Casp11 and Casp12 locus is as low as that between Casp11 and Casp1, the Casp12-/- mice are effectively Casp12-/-Casp11-/-double knockout mice. Finally, since murine caspase-11 activation potentially involves ER membrane trafficking (see “What is the caspase-11 activator?” above), further studies are necessary in order to substantiate potential links between ER membranes and caspase-4/5/11 functions.

Concluding Remarks

Innate immune responses are the first line of defense against invasive pathogens, and as such, the responses must be simultaneously comprehensive and potent. Although the pro-inflammatory caspase-11 was previously implicated in host defense, researchers did not have the tools to dissect out the mechanistic details of the crosstalk between caspase-1 and -11 in mice until recently. Emerging data now point to a cascade of events during which caspase-11 promotes and corroborates caspase-1 activity through NLRP3 inflammasomes. Caspase-11 is also capable of independently inducing pyroptotic cell death. Future studies will need to be aimed at understanding the precise signals that activate caspase-11, how it synergizes with caspase-1 function, and what downstream targets lead to pyroptosis since direct death substrates have not been identified for either caspase-1 or caspase-11. The misregulation of caspase-1 and NLRP3 has also been implicated in several human inflammatory diseases and cancer (McIlwain et al., 2013). Thus, directing treatments aimed at modulating caspase-11-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and function may prove to be more effective for these relevant diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Monack lab for critical reading of the manuscript. We apologize if any references were left out due to space constraints. This work was supported by awards AI095396 and AI08972 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to D.M. and award AI007328-25 from the National Institute of Health and Dean's Postdoctoral Fellowship from Stanford University to T.M.N..

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Selected Reading

- Aachoui Y, Leaf IA, Hagar JA, Fontana MF, Campos CG, Zak DE, Tan MH, Cotter PA, Vance RE, Aderem A, et al. Caspase-11 protects against bacteria that escape the vacuole. Science. 2013;339:975–978. doi: 10.1126/science.1230751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter A, Caution K, Abu Khweek A, Tazi M, Abdulrahman BA, Abdelaziz DH, Voss OH, Doseff AI, Hassan H, Azad AK, et al. Caspase-11 promotes the fusion of phagosomes harboring pathogenic bacteria with lysosomes by modulating actin polymerization. Immunity. 2012;37:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:99–109. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatright KM, Renatus M, Scott FL, Sperandio S, Shin H, Pedersen IM, Ricci JE, Edris WA, Sutherlin DP, Green DR, et al. A unified model for apical caspase activation. Mol Cell. 2003;11:529–541. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatright KM, Salvesen GS. Mechanisms of caspase activation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, Newton K, Lamkanfi M, Mariathasan S, Dixit VM, Monack DM. Redundant roles for inflammasome receptors NLRP3 and NLRC4 in host defense against Salmonella. J Exp Med. 2010a;207:1745–1755. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, Ruby T, Belhocine K, Bouley DM, Kayagaki N, Dixit VM, Monack DM. Caspase-11 increases susceptibility to Salmonella infection in the absence of caspase-1. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature11419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, von Moltke J, Jones JW, Vance RE, Monack DM. Differential requirement for Caspase-1 autoproteolysis in pathogen-induced cell death and cytokine processing. Cell Host Microbe. 2010b;8:471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case CL, Kohler LJ, Lima JB, Strowig T, de Zoete MR, Flavell RA, Zamboni DS, Roy CR. Caspase-11 stimulates rapid flagellin-independent pyroptosis in response to Legionella pneumophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1851–1856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211521110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang DW, Ditsworth D, Liu H, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Yang X. Oligomerization is a general mechanism for the activation of apoptosis initiator and inflammatory procaspases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16466–16469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L, Munoz-Planillo R, Nunez G. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:325–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung P, Malireddi RK, Anand PK, Demon D, Walle LV, Liu Z, Vogel P, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. TRIF-mediated caspase-11 production integrates TLR4- and Nlrp3 inflammasome-mediated host defense against enteropathogens. J Biol Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraga A, Ohlson MB, Miller SI. Salmonellae interplay with host cells. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:53–66. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi J, Katayama T, Eguchi Y, Kudo T, Taniguchi M, Koyama Y, Manabe T, Yamagishi S, Bando Y, Imaizumi K, et al. Involvement of caspase-4 in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and Abeta-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:347–356. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubber A, Roy CR. Modulation of host cell function by Legionella pneumophila type IV effectors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:261–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SJ, Wang S, Kuida K, Yuan J. Distinct downstream pathways of caspase-11 in regulating apoptosis and cytokine maturation during septic shock response. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1115–1125. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Vande Walle L, Louie S, Dong J, Newton K, Qu Y, Liu J, Heldens S, et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. 2011;479:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M, Sarkar A, Vande Walle L, Vitari AC, Amer AO, Wewers MD, Tracey KJ, Kanneganti TD, Dixit VM. Inflammasome-dependent release of the alarmin HMGB1 in endotoxemia. J Immunol. 2010;185:4385–4392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Brieher WM, Scimone ML, Kang SJ, Zhu H, Yin H, von Andrian UH, Mitchison T, Yuan J. Caspase-11 regulates cell migration by promoting Aip1-Cofilin-mediated actin depolymerization. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:276–286. doi: 10.1038/ncb1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin XY, Choi MS, Porter AG. Expression analysis of the human caspase-1 subfamily reveals specific regulation of the CASP5 gene by lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39920–39926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007255200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie SH, Clark AC. Death by caspase dimerization. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;747:55–73. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3229-6_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, Vucic D, French DM, Lee WP, Roose-Girma M, Erickson S, Dixit VM. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O'Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, Lee WP, Weinrauch Y, Monack DM, Dixit VM. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlwain DR, Berger T, Mak TW. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller NJ, Wilkinson RA, Fishman JA. Listeria monocytogenes infection in caspase-11-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2657–2664. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2657-2664.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Zhu H, Morishima N, Li E, Xu J, Yankner BA, Yuan J. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature. 2000;403:98–103. doi: 10.1038/47513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TM, Kortmann J, Monack DM. Policing the cytosol--bacterial-sensing inflammasome receptors and pathways. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nour AM, Yeung YG, Santambrogio L, Boyden ED, Stanley ER, Brojatsch J. Anthrax lethal toxin triggers the formation of a membrane-associated inflammasome complex in murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1262–1271. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01032-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam VA, Vanaja SK, Waggoner L, Sokolovska A, Becker C, Stuart LM, Leong JM, Fitzgerald KA. TRIF Licenses Caspase-11-Dependent NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Gram-Negative Bacteria. Cell. 2012;150:606–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reig N, van der Goot FG. About lipids and toxins. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5572–5579. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubartelli A, Cozzolino F, Talio M, Sitia R. A novel secretory pathway for interleukin-1 beta, a protein lacking a signal sequence. Embo J. 1990;9:1503–1510. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santic M, Molmeret M, Abu Kwaik Y. Maturation of the Legionella pneumophila-containing phagosome into a phagolysosome within gamma interferon-activated macrophages. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3166–3171. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.3166-3171.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauvliege R, Vanrobaeys J, Schotte P, Beyaert R. Caspase-11 gene expression in response to lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma requires nuclear factor-kappa B and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41624–41630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotte P, Van Criekinge W, Van de Craen M, Van Loo G, Desmedt M, Grooten J, Cornelissen M, De Ridder L, Vandekerckhove J, Fiers W, et al. Cathepsin B-mediated activation of the proinflammatory caspase-11. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:379–387. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer II, Scott S, Chin J, Bayne EK, Limjuco G, Weidner J, Miller DK, Chapman K, Kostura MJ. The interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme (ICE) is localized on the external cell surface membranes and in the cytoplasmic ground substance of human monocytes by immuno-electron microscopy. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1447–1459. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollberger G, Strittmatter GE, Kistowska M, French LE, Beer HD. Caspase-4 is required for activation of inflammasomes. J Immunol. 2012;188:1992–2000. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taxman DJ, Huang MT, Ting JP. Inflammasome inhibition as a pathogenic stealth mechanism. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef PA, Kertesy SB, Lundberg K, Kahlenberg JM, Dubyak GR. Inhibitory effects of chloride on the activation of caspase-1, IL-1beta secretion, and cytolysis by the P2X7 receptor. J Immunol. 2005;175:7623–7634. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Miura M, Jung Y, Zhu H, Gagliardini V, Shi L, Greenberg AH, Yuan J. Identification and characterization of Ich-3, a member of the interleukin-1beta converting enzyme (ICE)/Ced-3 family and an upstream regulator of ICE. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20580–20587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Miura M, Jung YK, Zhu H, Li E, Yuan J. Murine caspase-11, an ICE-interacting protease, is essential for the activation of ICE. Cell. 1998;92:501–509. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80943-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Kobayashi Y. Selective release of a processed form of interleukin 1 alpha. Cytokine. 1994;6:597–601. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wewers MD. IL-1beta: an endosomal exit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10241–10242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403971101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Chang HY, Baltimore D. Autoproteolytic activation of pro-caspases by oligomerization. Mol Cell. 1998;1:319–325. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]