Abstract

The binding of at least two molecular targets simultaneously with a single bispecific antibody is an attractive concept. The use of bispecific antibodies as possible therapeutic agents for cancer treatment was proposed in the mid-1980s. The design and production of bispecific antibodies using antibody- and/or receptor-based platform technology has improved significantly with advances in the knowledge of molecular manipulations, protein engineering techniques, and the expression of antigens and receptors on healthy and malignant cells. The common strategy for making bispecific antibodies involves combining the variable domains of the desired mAbs into a single bispecific structure. Many different formats of bispecific antibodies have been generated within the research field of bispecific immunotherapeutics, including the chemical heteroconjugation of two complete molecules or fragments of mAbs, quadromas, F(ab’)2, diabodies, tandem diabodies and single-chain antibodies. This review describes key modifications in the development of bispecific antibodies that can improve their efficacy and stability, and provides a clinical perspective on the application of bispecific antibodies for the treatment of solid and liquid tumors, including the promises and research limitations of this approach.

Keywords: Bispecific antibody, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte, Fc receptor, immunotherapy, mAb, targeted T-cell, T-cell, tumor antigen

Introduction

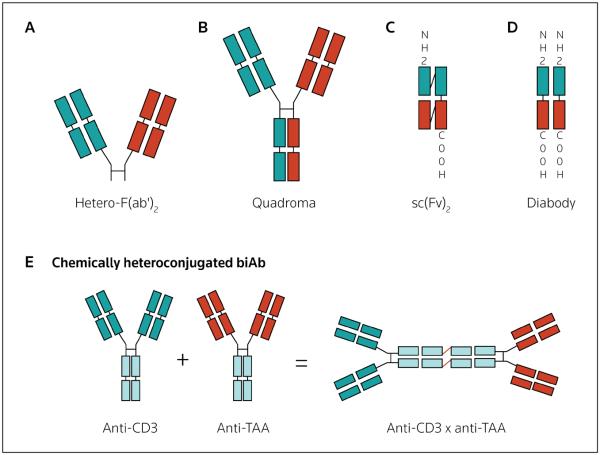

Developing improved treatment strategies for cancer is a challenging task wherein the balance between increasing clinical efficacy without increasing systemic toxicity determines the success of the drug. mAbs have become an important class of protein-based drugs (> 20 mAbs have been approved by the FDA) for the treatment of cancer and other diseases [1-7]. Multiple novel approaches are being explored to enhance the efficacy and targeting of mAbs to tumor antigens. Early efforts were focused on increasing the efficiency of mAbs by their direct conjugation with various effector compounds, such as toxins, radionucleotides and cytotoxic drugs. However, the majority of these chemical manipulations resulted in the inactivation of antibody-binding sites or in alterations to the functions of effector agents. The next step in this process was to use combinations of whole mAbs, fragments of mAbs, or dual-targeting antibodies referred to as bispecific antibodies (biAbs). BiAbs have two distinct binding specificities and represent a promising approach to improving the effectiveness of antitumor therapy. BiAbs can be infused alone or after coating effector cells to redirect their cytolytic activity. Protein engineering has produced a variety of biAb formats (Figure 1), among which quadroma, F(ab')2, diabodies, tandem diabodies and single-chain antibody (scFv)-based constructs are best characterized [8-11]. Trifunctional (tri)biAbs were developed to improve serum stability and in vivo efficacy. In tribiAbs, the two halves of the Fab (fragment antigen-binding) segment have different specificities, and engineered heterologous Fc (fragment crystallizable) variants facilitate enhanced serum stability and cytotoxicity [11,12]. The next modification led to the development of a multivalent and multifunctional dock-and-lock (DNL) tribiAb [13]. This review highlights the key developmental steps that lead to biAb-based therapies, either alone or in combination with effector cells armed with biAbs.

Figure 1. Bispecific antibody formats.

Genetically engineered antibody fragments or the heteroconjugation of intact antibodies to generate bispecific antibodies (biAbs) in various formats are shown: (A) fragment antigen-binding (Fab) format, (B) quadroma (IgG) formats constructed by fusing two hybridomas secreting antibodies of different specificities, (C) single-chain antibody (scFv [single-chain variable fragment])-based formats, (D) diabody formats or (E) chemical heteroconjugation of two IgG molecules [(IgG)2] of different antigen specificities. Hetero-F(ab)2 Heterogeneous fragment antigen-binding, TAA tumor-associated antigen

Combining cellular and humoral immunity

Both cellular- and antibody-based therapies exhibit antitumor activity, but do not engage each other because of the lack of Fc receptors on T-cells. Thus, a strategy that can combine cellular and humoral effectors will not only offer a potent anticancer response, but also a targeted and non-toxic therapeutic anticancer approach. The importance of cellular immunotherapy in cancer was first documented by Southam et al in 1966 [14]. This study demonstrated that subcutaneous growth of human tumor autografts to patients bearing advanced cancers was inhibited by the cotransfer of autologous leukocytes in approximately half of the patients [14]. Both allogeneic and autologous T-cells obtained from several anatomical sites were tested for cell-mediated antitumor activity. However, the effectiveness of cell therapy was compromised by multiple factors, such as quantity, in vivo proliferative potential, specificity, homing to the tumor targets and effector cell functions [15-23]. Many early clinical trials using autologous lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) did not contribute greatly to the routine treatment of human cancer [15-23]. After numerous manipulations and efforts, Rosenberg and colleagues were the first to report an objective response rate of 34% among patients with metastatic malignant melanoma (MM) who were treated with TILs [24,25]. Results improved with further manipulations, such as treatment with adoptive transfer of T-cell receptor (TCR) gene-modified T-cells and high-dose IL-2 after non-myeloablative lymphodepleting chemotherapy, achieving an objective response rate of up to 49% [26]. These trials demonstrated that the adoptive transfer of TILs after non-myeloablative conditioning can be an effective treatment for patients with MM. Another example of immunotherapy successfully inducing cytogenetic and molecular remissions in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) was observed as a result of donor lymphocyte infusions (DLIs) after relapse of CML following allogeneic stem cell transplant [27-29]. Infusions of EBV-specific CTLs in EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disease (LPD) were also successful [29]. Nonetheless, the promising responses observed with CTL immunotherapy in MM and LPD have not been reproduced in other solid tumors or hematological malignancies, suggesting that new clinical treatment approaches are needed.

The development of most biAb constructs focuses on recruiting T-cells by targeting the CD3 complex, a potent signal transducer associated with polymorphic TCRs expressed on all T-cell subpopulations. Thus, biAbs offer an effective bridging between cellular and humoral effectors that can redirect and harness the cytotoxic potential of T-lymphocytes to kill tumor cells in a non-MHC-restricted manner.ssn

Bispecific antibodies

BiAbs are able to crosslink different target antigens either on the same cell or on two different cells. Because of their dual specificity, biAbs can activate immune effector cells by targeting the CD3 complex, costimulatory CD28 molecule (supra-agonistic) on T-cells or Fcγ receptors [FcγRs] on accessory cells, and can bind simultaneously to tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) on tumor cells [30-34]. Since Milstein and Cuello first described the hybrid hybridoma technique, numerous biAbs that target antigens on tumor cells and receptors on effector cells have been developed and demonstrated to redirect cellular cytotoxicity [35]. The concept of using such biAbs to engage CTLs for cancer cell lysis was first reported by Staerz and Bevan in 1986 [36,37]. This concept was based on the observation that anti-idiotypic and anti-allotypic mAbs coupled covalently to any cell surface will render that cell sensitive to lysis by a CTL expressing a receptor recognized by the mAb.

BiAb constructs can be produced by the co-expression of two antibodies in one cell, via the hybrid hybridoma technique or by DNA cotransfection, or via protein engineering methods. One antibody of the biAb construct binds to a trigger (receptor) molecule on an immune effector cell and a second antibody binds to tumor antigens, such as HER2/neu [38], epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) [39], the EGFR [40] and the folate receptor [41].

Hybrid hybridoma (also referred to as quadroma) was the earliest technology used to produce biAbs [36]. This technology is based on the somatic fusion of two different hybridoma cell lines expressing murine mAbs of desired specificities. However, because of the random pairing between two different Ig heavy and light chains, the quality of the desired biAbs was poor, resulting in 80 to 90% of mispaired byproducts. The next improvement was the development of a mouse-rat quadroma expressing mAbs with two IgG subclasses selected for their preferential pairing [11]. The yields and purity of the biAbs were further improved by differential elution techniques that reduced contamination with parental antibodies [11]. Ertumaxomab (anti-HER2 × anti-CD3; Fresenius Biotech GmbH; Table 1) and catumaxomab (Removab, anti-EpCAM × anti-CD3; Table 1) are tribiAbs developed using the quadroma technology [42]. These biAbs are directed against TAA and CD3 and bind selectively to type I/III FcγRs, forming a complex between tumor cells, T-cells and accessory cells [11,42].

Table 1.

Selected clinical trials with bispecifc antibodies.

| BiAb (alternative name; developing company) |

Target or cancer type | Effector cell | Antibody format | Reference/ClinicalTrials.gov identifer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD3 x anti-EpCAM (catumaxomab, Removab) |

Ovarian, gastric, colon and breast (malignant ascites) cancers |

T-cells | IgG | [70,73] |

| NSCLC | T-cells | IgG | [72] | |

| Ovarian carcinoma | T-cells | IgG | NCT00189345 | |

| Anti-CD3 x anti-CD19 (blinatumomab; Micromet AG/Micromet Inc) |

NHL | T-cells | BiTE | NCT00274742 |

| B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

T-cells | BiTE | NCT00560794 | |

| Anti-CD3 x anti-CA19-9 (OKT3/NSI19-9) |

CA19-9-positive tumors | T-cells | IgG | [97] |

| Anti-CD3 x anti-CEA | Human CEA-expressing cells | T-cells | F(ab’)2 | [98] |

| Anti-CD3 x anti-CEA | Ovarian carcinoma | T-cells | Diabody | [99] |

| Anti-CD3 x anti-CD19 (SHR-1) | NHL | T-cells | IgG | [55] |

| Anti-OCAA x anti-CD3 (OC/TR) | Ovarian carcinoma | T-cells | F(ab’)2 | [92,100] |

| Anti-CD3 x anti-CD20 (CD20 biAb) | NHL | T-cells | (IgG)2 | NCT00521261 |

| Anti-CD3 x anti-HER2 (HER-2Bi-armed ATCs; Transtarget Inc) |

Metastatic breast cancer | T-cells | (IgG)2 | NCT01022138 |

| Anti-CD3 x anti-HER2 (ertumaxomab; Fresenius Biotech GmbH) |

Metastatic breast cancer | T-cells | IgG | NCT00452140 |

| Anti-CD28 x MAPG (rM28) | Metastatic melanoma | T-cells | Tandem scFv | NCT00204594 |

| Anti-EpCAM x anti-CD3 (MT-110; Micromet Inc) |

Adenocarcinoma of the lung, small cell lung cancer, gastric and colorectal cancer |

T-cells | BiTE | NCT00635596 |

| Anti-CD16 x anti-CD30 (HRS-3/A9) | Hodgkin’s disease | NK cells | IgG | [101] |

| Anti-CD16 x anti-HER2 (2B1) | HER2-positive tumors | NK cells | IgG | [57,102] |

| Anti-CD3 x anti-glioma | Human glioma | LAK cells | F(ab’)2 | [53] |

| Anti-CD64 x anti-HER2 (MDX-210 and MDX-H210) |

Breast, ovarian and prostate cancer |

Monocytes/ macrophages |

F(ab’)2 | [59,60] |

| Anti-CD64 x anti-EGFR (MDX-447) | Solid tumors | Monocytes/ macrophages |

F(ab’)2 | [103] |

ATCs Activated T-cells, biAb bispecifc antibody, BiTE bispecifc T-cell engager, CA19-9 cancer (gastrointestinal)-associated antigen CEA carcino-embryonic antigen, EpCAM epithelial cell adhesion molecule, F(ab’)2 two fragment antigen binding, (IgG)2 biAb generated by chemical heteroconjugation of two IgG molecules of different specifcities, LAK lymphokine-activated killer, NHL Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, MAPG melanoma-associated proteoglycan, OCAA ovarian cancer associated antigen, OC/TR chimeric biAb against human folate-binding protein overexpressed in ovarian carcinoma and T-cell receptors (CD3), scFv single-chain variable fragment

The DNL method described by Rossi and colleagues is another well-designed approach to generate biAbs with multivalency and multifunctionality [13,43]. This method uses the self-assembling dimerization-and-docking domain (DDD) mAb attached to a DDD moiety, wherein two copies of the DDD moiety form a dimer that binds to the anchoring domain (AD) moiety, resulting in the formation of the DNL complex. The combining of the respective DDD- and AD-modules generates stably-tethered structures of defined composition with retained bioactivity. The main advantage of this system is that an antibody fragment of any specificity can be produced separately, as fusion proteins with either a DDD or a AD and, when needed, a simple mixing of the two purified products will yield the desired biAb [43].

Continued efforts to improve the therapeutic efficacy of biAbs led to the development of a new class of biAbs – BiTE (bispecific T-cell engager) and diabodies. Constructs in which linked variable heavy (VH)-variable light (VL) pairs are from the same antibody are referred to as scFvs, with two such scFvs connected by a linker to yield a single polypeptide chain [10]. Diabodies are arranged such that linked VL–VH pairs are from two different antibodies. BiTE biAbs can bind monovalently to all T-cells, but do so with low affinity [9], and will not trigger T-cell signaling by CD3 unless the BiTE antibody is presented to the T-cell in a multivalent manner by a target cell [44]. This mode of action is referred to as BiTE technology. An approach using the multimerization of antibody fragments was developed to improve the serum half-life and binding affinity of BiTE biAbs. Similarly, divalent scFvs were developed from the monovalent scFvs, either through the spontaneous non-covalent association of two scFv molecules (ie, diabodies) or through a covalent disulfide bond. Divalent and multivalent scFvs were also generated by linking two or more scFv molecules using a peptide linker [10].

A variety of immune effector cells, such as CTLs, NK cells, neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, or drugs, toxins, enzymes, prodrugs, DNA, antivascular agents, viral vectors and radionuclides are redirected using biAbs. For T-cells, cytotoxicity is redirected to tumor targets, bypassing MHC restrictions by targeting CD3 on T-cells. A wide variety of effector responses can be derived against tumor cells by changing the specificities of the anti-effector and anti-target components of the biAb [45-48].

Clinical trials using bispecific antibodies Whole IgG-based bispecific antibodies

Several clinical trials have been conducted with chemically linked or genetically engineered biAbs targeting TCRs or FcγRs and TAA, either alone or in combination with IFNγ, GM-CSF or G-CSF [49-51]. The trials using local [52,53] or intravenous injections [54] of biAbs alone were conducted in the early 1990s. Local injections of biAbs caused antitumor activity and acute-phase inflammatory responses. However, the effectiveness of the biAbs was restricted to the tumor injection site with little impact on distant metastatic sites of disease. Subsequent trials tested whether biAbs can arm and redirect T-cells to tumor sites. A phase I trial conducted in patients with CD19+ non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) using SHR-1 biAbs (anti-CD3 × anti-CD19; Table 1) demonstrated that infusions of SHR-1 could arm endogenous T-cells and retarget them to tumor sites [55]. Similarly, a phase I trial conducted by Kroesen et al using BIS-1 biAbs (anti-CD3 × anti-EGP-2) confirmed that endogenous T-cells could be armed and redirected to tumor sites [56]. However, in both of these trials DLT was observed. Trials in solid tumors using 2B1 (anti-HER2 × anti-FcγRIII; Table 1), a murine IgG quadroma, to target HER2/neu-positive tumors did not reveal any antitumor responses [57,58]. Treatment resulted in significant increases in TNFα, IL-2, and IL-8, with 14 out of 15 patients developing human anti-mouse antibody (HAMA) responses; however, DLT limited the clinical use of this biAb [57]. The results from these trials suggest that whole IgG-based biAb infusions cause the activation of immune cells, leading to unmanageable cytokine storm, and prompting the redesign and modification of biAb constructs to overcome DLTs.

MDX bispecific antibodies based on the heterogeneous F(ab′)2 molecule

Using the same platform as 2B1 and targeting the same epitope on HER2, MDX-210 (Table 1), a heterogeneous (hetero)-F(ab')2 molecule, was produced by chemically conjugating a humanized anti-CD64 Fab' with a murine anti-HER2/neu Fab' [59]. This biAb was engineered to delete Fc domains to decrease adverse reactions. Patients tolerated higher doses of MDX-210 than the intact IgG-based biAb 2B1. In addition, the deletion of the Fc domains decreased the cytokine storm-related toxicities observed in the 2B1 clinical trials [59]. Phase I trials using the MDX-210 biAb revealed potent in vitro cytotoxicity, phagocytosis and induction of anti-HER2 antibodies. However, trials with either 2B1 or MDX-210 demonstrated no consistent pattern of antitumor activity [57,59]. In a phase II trial, James et al evaluated MDX-H210 (a semi-humanized antibody; Table 1) in combination with GM-CSF and reported that this combination is active in hormone-refractory prostate carcinoma with acceptable toxicity [60]. In a multidose trial conducted by Posey et al, GM-CSF was administered on days 1 to 4 and MDX-H210 was administered on day 4 weekly for 4 consecutive weeks, with ten patients completing 4 weeks of treatment [61]. One patient had a 48% reduction in lesions and six patients had stable disease at the time of evaluation; three patients exhibited disease progression before the fourth week. The therapy was generally well tolerated with toxicity limited primarily to the days of treatment [61].

BiTE-bispecific antibodies

Bispecific immunotherapeutics involving CD3-binding activity, and in particular the scFv-based BiTE format, have demonstrated promising results in directing CTL responses against tumor cells. BiTE antibodies are able to induce potent redirected lysis of target antigen-expressing cells at pico- to femtomolar concentrations that is accompanied by highly conditional T-cell activation [44,62]. Phase I and II clinical trials are being conducted with the CD19/CD3-bispecific blinatumomab (MT-103; Micromet AG/Micromet Inc; Table 1) and the EpCAM/CD3-bispecific MT-110 (Micromet) BiTE antibodies [9,63,64]. Results with blinatumomab from the phase I trial have confirmed that T-cells can be potently engaged for redirected tumor cell lysis in patients with cancer [65]. Among patients with NHL (n = 38) receiving blinatumomab (doses ranging from 0.0005 to 0.06 mg/m2/day), 11 patients exhibited objective responses. In addition, four patients demonstrated complete responses (CRs), and seven patients exhibited partial tumor regressions (PRs) at doses of ≥ 0.015 mg/m2/day. Seven patients treated at the dose level of 0.06 mg/m2/day displayed objective responses. Tumor regressions were observed in patients with follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blinatumomab doses of ≥ 0.015 mg/m2/day led to the depletion of tumor cells not only in blood, lymph node lesions and spleen, but also in the bone marrow. In 9 out of 11 cases of bone marrow infiltration, immunohistochemical and flow cytometric analysis of patient biopsies revealed either complete (n = 6) or partial (n = 3) elimination of tumor cells from the bone marrow [65].

Data from a phase II clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00560794) in patients with B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia indicated that T-cells engaged by blinatumomab are able to locate and eradicate rare disseminated tumor cells in the bone marrow that can only be detected by quantitative PCR assays, which identify tumor cell-specific genomic aberrations [66]. Data from these ongoing trials demonstrate the highly effective cytotoxic activity of T-cells against both bulky and minimal residual disease [67].

Trifunctional antibodies

Trifunctional antibodies (triAb) were also designed and developed to improve the effectiveness of biAbs further [68,69]. A triAb is composed of the halves of two distinct full-size antibodies, a tumor-specific mouse antibody and a T-cell specific rat antibody, combined in one molecule. TriAbs therefore have two different specific binding sites, while the Fc portion binds to accessory cells, providing a trifunctionality to this antibody. Burges et al conducted a phase I/II clinical trial using the anti-CD3 × anti-EpCAM triAb catumaxomab, administered intraperitoneally to patients (n = 23) with recurrent malignant ascites from ovarian cancer [70]. A 5-log reduction in EpCAM-positive tumor cells in the ascites was observed after therapy with intraperitoneal injections of catumaxomab, and direct injections of the antibody demonstrated clinical promise, but was limited by DLTs when administered intravenously. Kiewe et al reported a phase I trial of ertumaxomab, which is a tri-antibody directed at CD3 and HER2/neu with a Fcγ type I/III receptor that establishes a tri-cell complex between T-cells, Fc receptor-positive cells and tumor cells [71]. The majority of patients (15 out of 17) completed the trial (MTD of 100 µg) with mild and transient side effects. Antitumor responses were observed in 5 out of 15 patients, with one CR, two PRs and 2 patients with stable disease. Testing for serum cytokines revealed a Th1 pattern [71]. Another phase I trial using a triAb for the treatment of NSCLC demonstrated that catumaxomab can be infused intravenously in combination with dexamethasone with substantially reduced side effects [72]. The MTD was 5 µg of catumaxomab administered after 50 mg of dexamethasone. Results from this trial suggested that clinical responses can be obtained without DLTs using infusions of triAbs. Catumaxomab is the most advanced triAb based on TRION Pharma GmbH's TriomAb technology, and received EU approval for the intraperitoneal treatment of malignant ascites in patients with EpCAM-positive carcinomas in 2009 [73]. This triAb is not only the first drug indicated for the treatment of malignant ascites, but is also the first approved bispecific triAb.

The activation and targeting of immune effector cells

Studies have revealed that the in vitro activation of T-cells prior to arming enhances antitumor activity [74-76]. Similarly, the higher lytic activity of in vitro-activated PBMCs compared with resting PBMCs against tumor cells has been demonstrated [77-80]. While the in vitro activation and expansion of T-cells is straightforward and is typically achieved using the CD3-recognizing mAb (OKT3) that is present on all T-lymphocytes together with low doses of IL-2 [80-82], the in vivo activation of CTLs is not as simple. Clinical trials aimed at activating CTLs using OKT3 were unsuccessful [83-86]. Consistent with these results, Janssen et al demonstrated that whole blood cultures exhibited a poor proliferative response when OKT3 was added, whereas isolated PBMCs displayed brisk proliferative responses to OKT3 [87].

BiAb-induced effector cell-mediated cytotoxicity not only results in cell death, but also leads to cytokine and chemokine release through biAb-induced effector-target interactions. The release of multiple cytokines and chemokines, such as IFNγ, GM-CSF, IL-12, MIP-1α and MIP-1β, may recruit and activate endogenous immune cells to enhance the local antitumor response [88]. Cytotoxicity can induce cell death, either through necrosis or apoptosis, that can facilitate tumor antigen release and cytokine/chemokine production, all of which augment the recruitment and uptake of TAAs. Studies have revealed that arming ex vivo-expanded activated T-cells (ATCs) with biAbs prior to infusion can enhance cytotoxicity to several TAAs; this strategy converts every ATC into a specific CTL [89-91].

Clinical trials using bispecific antibody-armed/coated effector cells

The first clinical trial using biAb-armed LAK cells, which were co-injected into brain tumors with heteroconjugated anti-CD3 × anti-glioma biAbs, was reported in 1990 [53]. This trial demonstrated encouraging results, with four out of ten patients exhibiting regressed tumors and improved survival. A subsequent trial by Canevari et al evaluated the antitumor effect of the anti-ovarian cancer × anti-CD3 antibody (OC/TR; Table 1), a F(ab')2 of a quadroma that recognizes a folate-binding protein on cells with one arm and anti-CD3 with the other arm [92]. In this trial, ex vivo-expanded T-cells were armed (coated) with OC/TR biAbs and injected regionally (intraperitoneally) together with additional soluble biAbs and, in some cases, low-dose IL-2. The arming dose of OC/TR was 1 mg/109 viable cells (~ 1000 ng/106 cells). Despite high tumor burdens, 27% of patients demonstrated clinical responses. Mild side effects were observed with intraperitoneal administration; however, intravenous injection of even low doses of OC/TR F(ab')2 resulted in non-specific T-cell activation, TNFα secretion and toxicity [92]. Subsequent to this trial, Link et al reported that non-specific T-cell activation from biAbs can occur in an antigen-independent manner because of the Fc/Fc receptor interaction with whole IgG-based biAbs, or in an antigen-dependent manner when antigen is expressed on healthy or tumor cells with F(ab')2-biAbs [93]. Both mechanisms may be responsible for the toxicities observed in prior trials. Table 1 summarizes selected biAbs that have been evaluated in trials.

In a pilot clinical trial, Riechelmann et al used antibody-coated immune cells in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma to determine the MTD of the loading dose of catumaxomab onto PBMCs [94]. PBMCs were collected from patients (n = 4) by leukapheresis, incubated with catumaxomab ex vivo for 24 h and cleared from released cytokines prior to infusion into patients at twice-weekly intervals. This strategy was undertaken to remove large amounts of IFNγ and TNFα that were released with the binding of catumaxomab to PBMCs prior to administration. Ex vivo loading with triAb and the removal of potent cytokines and chemokines was concluded to decrease the severity of the cytokine storm [94].

The ongoing phase I/II dose-escalation clinical trial of HER-2Bi-armed ATCs in women (n = 20) with stage IV breast cancer is being conducted to determine the MTD or technically feasible dose and, thus far, has revealed no DLTs at total dose levels of 40, 80 and 160 billion total cells per patient [88]. Eight infusions are administered twice weekly for 4 weeks along with IL-2 (300,000 IU/m2/day sc) and GM-CSF (250 µg/m2 twice weekly) beginning 3 days before the first armed ATC infusion and ending 1 week after the last infusion. The highest dose is 4.0 × 1010 cells per infusion for a total dose of 3.20 × 1011 HER-2Bi-armed ATCs. Armed ATC infusions of up to 20 × 109 cells have been well tolerated, with chills, fever and transient hypotension managed with antihistamines, meperidine, antipyretics and hydration. After four infusions, investigations using the peripheral blood from several patients revealed cytotoxicity directed at the breast cancer cell line SK-BR-3, and serum cytokine profiles that were shifted toward a Th1 pattern. IFNγ, GM-CSF, TNFα and IL-12 were detected in the serum of patients 2 weeks after the initiation of immunotherapy [88].

In vitro studies by Guo et al also suggest that antitumor responses can be generated by in vitro targeting with biAbs and the modification of tumor cells with cytokines to generate immunogenic tumor cells [95]. The major difference of low-grade toxicity observed by Lum et al [88,96] compared with other trials using biAb-armed ATC therapy in which high-grade toxicity has been observed, may be a result of the ex vivo arming of the T-cells prior to infusion, such that unbound biAbs are not infused into the patients. In other words, the biAb effect is limited to the interactions of the armed effector cells, as opposed to biAb infusions that provide much larger amounts of circulating biAbs to interact with immune cells in the patient leading to cytokine storm. The infusions of targeted ATCs may induce vaccine responses by creating a local environment that contains tumor lysates and high local concentrations of Th1 cytokines and chemokines, inducing the development of endogenous dendritic cells, which in turn, would facilitate tumor antigen (lysate) presentation to endogenous naïve T-cells. These trials demonstrate promising results using biAbs that can target tumor cells selectively and may immunize patients against their own tumors [88,96].

Conclusion

Several biAbs display significant in vitro cytotoxicity and antitumor effects in animal models, but fail to demonstrate consistent clinical activity. In most clinical trials in which clinical response was observed, cellular immunotherapy was administered after debulking chemotherapy, surgery and/or radiation, highlighting the importance of lymphodepletion, decreased tumor burden and/or regulatory T-cell depletion. Failure to obtain clinical responses may reflect limitations in tumor targeting, inadequate lymphocyte migration to tumor sites, defective in vivo activation of lymphocytes, and in vivo suppression of memory and effector CTLs. More recently, the concept of multiple receptor targeting and fusion molecules has been applied to the development of triAb or trispecific antibodies. Advances in the understanding of tumor antigens, antibody engineering and immunology, and their application in the appropriate clinical models may help to resolve some of these challenges and improve the effectiveness of biAb-targeted immunotherapy.

Acknowledgements

Research involving ATCs and ATCs armed with biAbs was funded in part by R01 CA092344 from the NIH, 5P30CA022453-24 Cancer Center Grant from the NIH, Translational Grant number 60660-5 from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Susan G Komen Foundation Grant number BCTR0707125, Michigan Cell Therapy Center for Excellence Grant number 1819 from the State of Michigan, and funding from the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute.

References

•• of outstanding interest

• of special interest

- 1.Baselga J, Tripathy D, Mendelsohn J, Baughman S, Benz CC, Dantis L, Sklarin NT, Seidman AD, Hudis CA, Moore J, Rosen PP, et al. Phase II study of weekly intravenous recombinant humanized anti-p185HER2 monoclonal antibody in patients with HER2/neu-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):737–744. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobleigh MA, Vogel CL, Tripathy D, Robert NJ, Scholl S, Fehrenbacher L, Wolter JM, Paton V, Shak S, Lieberman G. Slamon DJ: Multinational study of the efficacy and safety of humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody in women who have HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer that has progressed after chemotherapy for metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(9):2639–2648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundin J, Kimby E, Björkholm M, Broliden PA, Celsing F, Hjalmar V, Möllgard L, Rebello P, Hale G, Waldmann H, Mellstedt H, et al. Phase II trial of subcutaneous anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) as first-line treatment for patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) Blood. 2002;100(3):768–773. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maloney DG, Liles TM, Czerwinski DK, Waldichuk C, Rosenberg J, Grillo-Lopez A, Levy R. Phase I clinical trial using escalating single-dose infusion of chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (IDEC-C2B8) in patients with recurrent B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1994;84(8):2457–2466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaughlin P, Grillo-Lopez AJ, Link BK, Levy R, Czuczman MS, Williams ME, Heyman MR, Bence-Bruckler I, White CA, Cabanillas F, Jain V, et al. Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: Half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(8):2825–2833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller RA, Maloney DG, Warnke R, Levy R. Treatment of B-cell lymphoma with monoclonal anti-idiotype antibody. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(9):517–522. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198203043060906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Steinberg SM, Chen HX, Rosenberg SA. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(5):427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asano R, Ikoma K, Kawaguchi H, Ishiyama Y, Nakanishi T, Umetsu M, Hayashi H, Katayose Y, Unno M, Kudo T, Kumagai I. Application of the Fc fusion format to generate tag-free bispecific diabodies. FEBS J. 2010;277(2):477–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreier T, Lorenczewski G, Brandl C, Hoffmann P, Syring U, Hanakam F, Kufer P, Riethmuller G, Bargou R, Baeuerle PA. Extremely potent, rapid and costimulation-independent cytotoxic T-cell response against lymphoma cells catalyzed by a single-chain bispecific antibody. Int J Cancer. 2002;100(6):690–697. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kufer P, Lutterbüse R, Baeuerle PA. A revival of bispecific antibodies. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22(5):238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindhofer H, Mocikat R, Steipe B, Thierfelder S. Preferential species-restricted heavy/light chain pairing in rat/mouse quadromas. Implications for a single-step purification of bispecific antibodies. J Immunol. 1995;155(1):219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazar GA, Dang W, Karki S, Vafa O, Peng JS, Hyun L, Chan C, Chung HS, Eivazi A, Yoder SC, et al. Engineered antibody Fc variants with enhanced effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(11):4005–4010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508123103. • Describes the use of computational design algorithms and high-throughput screening to engineer a series of Fc variants with optimized FcγR affinity for improved effector functions against cells expressing low levels of the target antigen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldenberg DM, Rossi EA, Sharkey RM, McBride WJ, Chang CH. Multifunctional antibodies by the dock-and-lock method for improved cancer imaging and therapy by pretargeting. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(1):158–163. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.046185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Southam CM, Brunschwig A, Levin AG, Dizon QS. Effect of leukocytes on transplantability of human cancer. Cancer. 1966;19(11):1743–1753. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196611)19:11<1743::aid-cncr2820191143>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damle NK, Doyle LV, Bradley EC. Interleukin 2-activated human killer cells are derived from phenotypically heterogeneous precursors. J Immunol. 1986;137(9):2814–2822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimm EA. Human lymphokine-activated killer cells (LAK cells) as a potential immunotherapeutic modality. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;865(3):267–279. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(86)90017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lafreniere R, Rosenstein MS, Rosenberg SA. Optimal methods for generating expanded lymphokine activated killer cells capable of reducing established murine tumors in vivo. J Immunol Methods. 1986;94(1-2):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merluzzi VJ, Smith MD, Last-Barney K. Similarities and distinctions between murine natural killer cells and lymphokine-activated killer cells. Cell Immunol. 1986;100(2):563–569. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(86)90054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ortaldo JR, Mason A, Overton R. Lymphokine-activated killer cells. Analysis of progenitors and effectors. J Exp Med. 1986;164(4):1193–1205. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.4.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owen-Schaub LB, Abraham SR, Hemstreet GP. 3rd: Phenotypic characterization of murine lymphokine-activated killer cells. Cell Immunol. 1986;103(2):272–286. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(86)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Muul LM, Leitman S, Chang AE, Vetto JT, Seipp CA, Simpson C. A new approach to the therapy of cancer based on the systemic administration of autologous lymphokine-activated killer cells and recombinant interleukin-2. Surgery. 1986;100(2):262–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg SA, Packard BS, Aebersold PM, Solomon D, Topalian SL, Toy ST, Simon P, Lotze MT, Yang JC, Seipp CA, et al. Use of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2 in the immunotherapy of patients with metastatic melanoma. A preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1676–1680. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812223192527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang JC, Mule JJ, Rosenberg SA. Murine lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells: Phenotypic characterization of the precursor and effector cells. J Immunol. 1986;137(2):715–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Delgado CH, Robbins PF, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Yannelli JR, Adema GJ, Miki T, Rosenberg SA. Identification of a human melanoma antigen recognized by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(14):6458–6462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg SA, Yannelli JR, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ, Weber JS, Parkinson DR, Seipp CA, Einhorn JH, White DE. Treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin 2. Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(15):1159–1166. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.15.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Sherry R, Restifo NP, Hubicki AM, Robinson MR, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298(5594):850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolb HJ, Holler E. Adoptive immunotherapy with donor lymphocyte transfusions. Curr Opin Oncol. 1997;9(2):139–145. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolb HJ, Mittermuller J, Clemm C, Holler E, Ledderose G, Brehm G, Heim M, Wilmanns W. Donor leukocyte transfusions for treatment of recurrent chronic myelogenous leukemia in marrow transplant patients. Blood. 1990;76(12):2462–2465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z, Savoldo B, Huls H, Lopez T, Gee A, Wilson J, Brenner MK, Heslop HE, Rooney CM. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes for the prevention and treatment of EBV-associated post-transplant lymphomas. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2002;159:123–133. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56352-2_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grosse-Hovest L, Hartlapp I, Marwan W, Brem G, Rammensee HG, Jung G. A recombinant bispecific single-chain antibody induces targeted, supra-agonistic CD28-stimulation and tumor cell killing. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33(5):1334–1340. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez P, Titus JA, Lotze MT, Cuttitta F, Longo DL, Groves ES, Rabin H, Durda PJ, Segal DM. Specific lysis of human tumor cells by T cells coated with anti-T3 cross-linked to anti-tumor antibody. J Immunol. 1986;137(7):2069–2072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raso V, Griffin T. Hybrid antibodies with dual specificity for the delivery of ricin to immunoglobulin-bearing target cells. Cancer Res. 1981;41(6):2073–2078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Segal DM, Garrido MA, Perez P, Titus JA, Winkler DA, Ring DB, Kaubisch A, Wunderlich JR. Targeted cytotoxic cells as a novel form of cancer immunotherapy. Mol Immunol. 1988;25(11):1099–1103. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(88)90144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Titus JA, Perez P, Kaubisch A, Garrido MA, Segal DM. Human K/natural killer cells targeted with hetero-cross-linked antibodies specifically lyse tumor cells in vitro and prevent tumor growth in vivo. J Immunol. 1987;139(9):3153–3158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milstein C, Cuello AC. Hybrid hybridomas and their use in immunohistochemistry. Nature. 1983;305(5934):537–540. doi: 10.1038/305537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Staerz UD, Bevan MJ. Hybrid hybridoma producing a bispecific monoclonal antibody that can focus effector T-cell activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(5):1453–1457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staerz UD, Bevan MJ. Targeting cells for attack by cytotoxic T lymphocytes using heteroconjugates of monoclonal antibodies. Symp Fundam Cancer Res. 1986;38:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fendly BM, Kotts C, Vetterlein D, Lewis GD, Winget M, Carver ME, Watson SR, Sarup J, Saks S, Ullrich A, Shepard M. The extracellular domain of HER2/neu is a potential immunogen for active specific immunotherapy of breast cancer. J Biol Response Mod. 1990;9(5):449–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balzar M, Winter MJ, de Boer CJ, Litvinov SV. The biology of the 17-1A antigen (Ep-CAM) J Mol Med. 1999;77(10):699–712. doi: 10.1007/s001099900038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Negri DR, Tosi E, Valota O, Ferrini S, Cambiaggi A, Sforzini S, Silvani A, Ruffini PA, Colnaghi MI, Canevari S. In vitro and in vivo stability and anti-tumour efficacy of an anti-EGFR/anti-CD3 F(ab’)2 bispecific monoclonal antibody. Br J Cancer. 1995;72(4):928–933. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canevari S, Mezzanzanica D, Mazzoni A, Negri DR, Ramakrishna V, Bolhuis RL, Colnaghi MI, Bolis G. Bispecific antibody targeted T cell therapy of ovarian cancer: Clinical results and future directions. J Hematother. 1995;4(5):423–427. doi: 10.1089/scd.1.1995.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heiss MM, Strohlein MA, Jager M, Kimmig R, Burges A, Schoberth A, Jauch KW, Schildberg FW, Lindhofer H. Immunotherapy of malignant ascites with trifunctional antibodies. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(3):435–443. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rossi EA, Goldenberg DM, Cardillo TM, McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Chang CH. Stably tethered multifunctional structures of defined composition made by the dock and lock method for use in cancer targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(18):6841–6846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600982103. • Describes the elegant DNL method for generating trivalent biAbs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brischwein K, Parr L, Pflanz S, Volkland J, Lumsden J, Klinger M, Locher M, Hammond SA, Kiener P, Kufer P, Schlereth B, et al. Strictly target cell-dependent activation of T cells by bispecific single-chain antibody constructs of the BiTE class. J Immunother. 2007;30(8):798–807. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318156750c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Cheung LH, Marks JW, Rosenblum MG. Recombinant single-chain antibody fusion construct targeting human melanoma cells and containing tumor necrosis factor. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(4):549–557. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Zhang W, Cheung LH, Niu T, Wu Q, Li C, Van Pelt CS, Rosenblum MG. The antimelanoma immunocytokine scFvMEL/TNF shows reduced toxicity and potent antitumor activity against human tumor xenografts. Neoplasia. 2006;8(5):384–393. doi: 10.1593/neo.06121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang TH, Morrison SL. A trimeric anti-HER2/neu ScFv and tumor necrosis factor-α fusion protein induces HER2/neu signaling and facilitates repair of injured epithelia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316(3):983–991. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.095513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenblum MG, Cheung LH, Liu Y, Marks JW. 3rd: Design, expression, purification, and characterization, in vitro and in vivo, of an antimelanoma single-chain Fv antibody fused to the toxin gelonin. Cancer Res. 2003;63(14):3995–4002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elsasser D, Valerius T, Repp R, Weiner GJ, Deo Y, Kalden JR, van de Winkel JG, Stevenson GT, Glennie MJ, Gramatzki M. HLA class II as potential target antigen on malignant B cells for therapy with bispecific antibodies in combination with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1996;87(9):3803–3812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis LD, Cole BF, Wallace PK, Fisher JL, Waugh M, Guyre PM, Fanger MW, Curnow RT, Kaufman PA, Ernstoff MS. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships of the bispecific antibody MDX-H210 when administered in combination with interferon γ: A multiple-dose phase-I study in patients with advanced cancer which overexpresses HER-2/neu. J Immunol Methods. 2001;248(1-2):149–165. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Ojik HH, Repp R, Groenewegen G, Valerius T, van de Winkel JG. Clinical evaluation of the bispecific antibody MDX-H210 (anti-Fc γ RI × anti-HER-2/neu) in combination with granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim) for treatment of advanced breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;45(3-4):207–209. doi: 10.1007/s002620050434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kroesen BJ, ter Haar A, Spakman H, Willemse P, Sleijfer DT, de Vries EG, Mulder NH, Berendsen HH, Limburg PC, The TH, de Leij L. Local antitumour treatment in carcinoma patients with bispecific-monoclonal-antibody-redirected T cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1993;37(6):400–407. doi: 10.1007/BF01526797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nitta T, Sato K, Yagita H, Okumura K. Ishii S: Preliminary trial of specific targeting therapy against malignant glioma. Lancet. 1990;335(8686):368–371. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90205-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ball ED, Guyre PM, Mills L, Fisher J, Dinces NB, Fanger MW. Initial trial of bispecific antibody-mediated immunotherapy of CD15-bearing tumors: Cytotoxicity of human tumor cells using a bispecific antibody comprised of anti-CD15 (MoAb PM81) and anti-CD64/Fc γ RI (MoAb 32) J Hematother. 1992;1(1):85–94. doi: 10.1089/scd.1.1992.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Gast GC, Van Houten AA, Haagen IA, Klein S, De Weger RA, Van Dijk A, Phillips J, Clark M, Bast BJ. Clinical experience with CD3 × CD19 bispecific antibodies in patients with B cell malignancies. J Hematother. 1995;4(5):433–437. doi: 10.1089/scd.1.1995.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kroesen BJ, Nieken J, Sleijfer DT, Molema G, de Vries EG, Groen HJ, Helfrich W, The TH, Mulder NH, de Leij L. Approaches to lung cancer treatment using the CD3 × EGP-2-directed bispecific monoclonal antibody BIS-1. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;45(3-4):203–206. doi: 10.1007/s002620050433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiner LM, Clark JI, Davey M, Li WS, Garcia de Palazzo I, Ring DB, Alpaugh RK. Phase I trial of 2B1, a bispecific monoclonal antibody targeting c-erbB-2 and Fc γ RIII. Cancer Res. 1995;55(20):4586–4593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weiner LM, Holmes M, Richeson A, Godwin A, Adams GP, Hsieh-Ma ST, Ring DB, Alpaugh RK. Binding and cytotoxicity characteristics of the bispecific murine monoclonal antibody 2B1. J Immunol. 1993;151(5):2877–2886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Valone FH, Kaufman PA, Guyre PM, Lewis LD, Memoli V, Deo Y, Graziano R, Fisher JL, Meyer L, Mrozek-Orlowski M. Phase Ia/Ib trial of bispecific antibody MDX-210 in patients with advanced breast or ovarian cancer that overexpresses the proto-oncogene HER-2/neu. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(9):2281–2292. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.9.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.James ND, Atherton PJ, Jones J, Howie AJ, Tchekmedyian S, Curnow RT. A phase II study of the bispecific antibody MDX-H210 (anti-HER2 × CD64) with GM-CSF in HER2+ advanced prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(2):152–156. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Posey JA, Raspet R, Verma U, Deo YM, Keller T, Marshall JL, Hodgson J, Mazumder A, Hawkins MJ. A pilot trial of GM-CSF and MDX-H210 in patients with erbB-2-positive advanced malignancies. J Immunother. 1999;22(4):371–379. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199907000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baeuerle PA, Kufer P, Lutterbuse R. Bispecific antibodies for polyclonal T-cell engagement. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2003;5(4):413–419. • Reviews a single-chain BiTE biAb that is emerging as a powerful and promising class of polyclonal T-cell-engaging proteins. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dreier T, Baeuerle PA, Fichtner I, Grun M, Schlereth B, Lorenczewski G, Kufer P, Lutterbuse R, Riethmuller G, Gjorstrup P, Bargou RC. T cell costimulus-independent and very efficacious inhibition of tumor growth in mice bearing subcutaneous or leukemic human B cell lymphoma xenografts by a CD19-/CD3-bispecific single-chain antibody construct. J Immunol. 2003;170(8):4397–4402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loffler A, Kufer P, Lutterbuse R, Zettl F, Daniel PT, Schwenkenbecher JM, Riethmuller G, Dorken B, Bargou RC. A recombinant bispecific single-chain antibody, CD19 × CD3, induces rapid and high lymphoma-directed cytotoxicity by unstimulated T lymphocytes. Blood. 2000;95(6):2098–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bargou R, Leo E, Zugmaier G, Klinger M, Goebeler M, Knop S, Noppeney R, Viardot A, Hess G, Schuler M, Einsele H, et al. Tumor regression in cancer patients by very low doses of a T cell-engaging antibody. Science. 2008;321(5891):974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1158545. •• First paper to report the therapeutic success of an anti-CD3 and anti-CD19 BiTE antibody in patients with NHL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Topp M, Goekbuget N, Kufer P, Zugmaier G, Degenhard E, Neumann S, Horst HA, Viardot A, Schmid M, Ottmann OG, Schmidt M, et al. Treatment with anti-CD19 BiTE antibody blinatumomab (MT103/MEDI-538) is able to eliminate minimal residual disease (MRD) in patients with B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): First results of an ongoing phase II study. Blood. 1926;112(Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baeuerle PA, Reinhardt C. Bispecific T-cell engaging antibodies for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2009;69(12):4941–4944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zeidler R, Mysliwietz J, Csanady M, Walz A, Ziegler I, Schmitt B, Wollenberg B, Lindhofer H. The Fc-region of a new class of intact bispecific antibody mediates activation of accessory cells and NK cells and induces direct phagocytosis of tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2000;83(2):261–266. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zeidler R, Reisbach G, Wollenberg B, Lang S, Chaubal S, Schmitt B, Lindhofer H. Simultaneous activation of T cells and accessory cells by a new class of intact bispecific antibody results in efficient tumor cell killing. J Immunol. 1999;163(3):1246–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burges A, Wimberger P, Kümper C, Gorbounova V, Sommer H, Schmalfeldt B, Pfisterer J, Lichinitser M, Makhson A, Moiseyenko V, Lahr A, et al. Effective relief of malignant ascites in patients with advanced ovarian cancer by a trifunctional anti-EpCAM × anti-CD3 antibody: A phase I/II study. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(13):3899–3905. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2769. •• Describes a landmark multicenter trial demonstrating the effectiveness of intraperitoneal catumaxomab administration in patients with ovarian cancer with malignant ascites containing EpCAM-positive tumor cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kiewe P, Hasmuller S, Kahlert S, Heinrigs M, Rack B, Marme A, Korfel A, Jager M, Lindhofer H, Sommer H, Thiel E, et al. Phase I trial of the trifunctional anti-HER2 × anti-CD3 antibody ertumaxomab in metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(10):3085–3091. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sebastian M, Passlick B, Friccius-Quecke H, Jager M, Lindhofer H, Kanniess F, Wiewrodt R, Thiel E, Buhl R, Schmittel A. Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer patients with the trifunctional monoclonal antibody catumaxomab (anti-EpCAM × anti-CD3): A phase I study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(10):1637–1644. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0310-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.TRION Pharma GmbH: EU approval for Removab: First trifunctional antibody hits market. Apr 23, 2009. Press Release.

- 74.Lum LG, Rathore R, Cummings F, Colvin GA, Radie-Keane K, Maizel A, Quesenberry PJ, Elfenbein GJ. Phase I/II study of treatment of stage IV breast cancer with OKT3 × trastuzumab-armed activated T cells. Clin Breast Cancer. 2003;4(3):212–217. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2003.n.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lum LG, Rathore R, Quesenberry PJ, Elfenbein GJ. Future prospects for patient care utilizing autologous lymphoid and hematopoietic stem cells. Med Health R I . 2003;86(8):247–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Davol PA, Smith JA, Kouttab N, Elfenbein GJ, Lum LG. Anti-CD3 × anti-HER2 bispecific antibody effectively redirects armed T cells to inhibit tumor development and growth in hormone-refractory prostate cancer-bearing severe combined immunodeficient beige mice. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2004;3(2):112–121. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2004.n.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Azuma M, Cayabyab M, Buck D, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. CD28 interaction with B7 costimulates primary allogeneic proliferative responses and cytotoxicity mediated by small, resting T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1992;175(2):353–360. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.2.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Donohue JH, Ramsey PS, Kerr LA, Segal DM, McKean DJ. Enhanced in vitro lysis of human ovarian carcinomas with activated peripheral blood lymphocytes and bifunctional immune heteroaggregates. Cancer Res. 1990;50(20):6508–6514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kerr L, Huntoon C, Donohue J, Leibson PJ, Bander NH, Ghose T, Luner SJ, Vessella R, McKean DJ. Heteroconjugate antibody-directed killing of autologous human renal carcinoma cells by in vitro-activated lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1990;144(10):4060–4067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Phillips JH, Lanier LL. Dissection of the lymphokine-activated killer phenomenon. Relative contribution of peripheral blood natural killer cells and T lymphocytes to cytolysis. J Exp Med. 1986;164(3):814–825. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.3.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jung G, Martin DE, Muller-Eberhard HJ. Induction of cytotoxicity in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by monoclonal antibody OKT3. J Immunol. 1987;139(2):639–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Van Wauwe JP, Goossens JG, Beverley PC. Human T lymphocyte activation by monoclonal antibodies; OKT3, but not UCHT1, triggers mitogenesis via an interleukin 2-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 1984;133(1):129–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Buter J, Janssen RA, Martens A, Sleijfer DT, de Leij L, Mulder NH. Phase I/II study of low-dose intravenous OKT3 and subcutaneous interleukin-2 in metastatic cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A(15):2108–2113. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(93)90044-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chatenoud L, Ferran C, Legendre C, Thouard I, Merite S, Reuter A, Gevaert Y, Kreis H, Franchimont P, Bach JF. In vivo cell activation following OKT3 administration. Systemic cytokine release and modulation by corticosteroids. Transplantation. 1990;49(4):697–702. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chatenoud L, Ferran C, Reuter A, Legendre C, Gevaert Y, Kreis H, Franchimont P, Bach JF. Systemic reaction to the anti-T-cell monoclonal antibody OKT3 in relation to serum levels of tumor necrosis factor and interferon-γ. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(21):1420–1421. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905253202117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sosman JA, Weiss GR, Margolin KA, Aronson FR, Sznol M, Atkins MB, O’Boyle K, Fisher RI, Boldt DH, Doroshow J. Phase IB clinical trial of anti-CD3 followed by high-dose bolus interleukin-2 in patients with metastatic melanoma and advanced renal cell carcinoma: Clinical and immunologic effects. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(8):1496–1505. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Janssen RA, Heijn AA, The TH, de Leij L. Poor induction of interleukin-2 receptor expression on CD8bright+ cells in whole blood cell cultures with CD3 mAb. Implications for immunotherapy with CD3 mAb. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1994;38(1):53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01517170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lum LG, Rathore R, Dizon D, Wang D, Al-Kadhimi Z, Uberti JP, Ratanatharathorn V. Induction of immune responses and improved survival after infusions of T cells armed with anti-CD3 × anti-HER2/neu bispecific antibody in stage IV breast cancer patients (phase I) Blood. 2007;110(11 Pt 1) [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grabert RC, Cousens LP, Smith JA, Olson S, Gall J, Young WB, Davol PA, Lum LG. Human T cells armed with HER2/neu bispecific antibodies divide, are cytotoxic, and secrete cytokines with repeated stimulation. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(2):569–576. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2005. •• Describes a trial suggesting that the arming of ATCs with biAbs engineered to bind CD3 on one end and a specific tumor antigen on the other end is a feasible approach for overcoming the practical limitations in cancer immunotherapy regarding the specificity and the magnitude of antitumor T-cell populations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lum LG, Davol PA, Lee RJ. The new face of bispecific antibodies: Targeting cancer and much more. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Reusch U, Sundaram M, Davol PA, Olson SD, Davis JB, Demel K, Nissim J, Rathore R, Liu PY, Lum LG. Anti-CD3 × anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) bispecific antibody redirects T-cell cytolytic activity to EGFR-positive cancers in vitro and in an animal model. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(1):183–190. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Canevari S, Stoter G, Arienti F, Bolis G, Colnaghi MI, Di Re EM, Eggermont AM, Goey SH, Gratama JW, Lamers CH, Nooy MA, et al. Regression of advanced ovarian carcinoma by intraperitoneal treatment with autologous T lymphocytes retargeted by a bispecific monoclonal antibody. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(19):1463–1469. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.19.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Link BK, Kostelny SA, Cole MS, Fusselman WP, Tso JY, Weiner GJ. Anti-CD3-based bispecific antibody designed for therapy of human B-cell malignancy can induce T-cell activation by antigen-dependent and antigen-independent mechanisms. Int J Cancer. 1998;77(2):251–256. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980717)77:2<251::aid-ijc14>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Riechelmann H, Wiesneth M, Schauwecker P, Reinhardt P, Gronau S, Schmitt A, Schroen C, Atz J, Schmitt M. Adoptive therapy of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma with antibody coated immune cells: A pilot clinical trial. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(9):1397–1406. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0283-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guo YJ, Che XY, Shen F, Xie TP, Ma J, Wang XN, Wu SG, Anthony DD, Wu MC. Effective tumor vaccines generated by in vitro modification of tumor cells with cytokines and bispecific monoclonal antibodies. Nat Med. 1997;3(4):451–455. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lum LG, Al-Kadhimi Z, Skuba C, Ratanatharathorn V, Uberti JP. Enhanced anti-breast cancer cytotoxicity after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant (PBSCT) by boosting with multiple infusions of activated T cells (ATC) armed with anti-CD3 × anti-HER2 bispecific antibody (HER2Bi) prior to PBSCT. Blood. 2007;110(11 Pt 1) [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hombach A, Tillmann T, Jensen M, Heuser C, Sircar R, Diehl V, Kruis W, Pohl C. Specific activation of resting T cells against CA19-9+ tumor cells by an anti-CD3/CA19-9 bispecific antibody in combination with a costimulatory anti-CD28 antibody. J Immunother. 1997;20(5):325–333. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199709000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kuwahara M, Kuroki M, Arakawa F, Senba T, Matsuoka Y, Hideshima T, Yamashita Y, Kanda H. A mouse/human-chimeric bispecific antibody reactive with human carcinoembryonic antigen-expressing cells and human T-lymphocytes. nticancer Res. 1996;16(5A):2661–2667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Compte M, Blanco B, Serrano F, Cuesta AM, Sanz L, Bernad A, Holliger P, Alvarez-Vallina L. Inhibition of tumor growth in vivo by in situ secretion of bispecific anti-CEA × anti-CD3 diabodies from lentivirally transduced human lymphocytes. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14(4):380–388. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bolhuis RL, Lamers CH, Goey SH, Eggermont AM, Trimbos JB, Stoter G, Lanzavecchia A, di Re E, Miotti S, Raspagliesi F, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy of ovarian carcinoma with bs-mAb-targeted lymphocytes: A multicenter study. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1992;7:78–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hartmann F, Renner C, Jung W, Deisting C, Juwana M, Eichentopf B, Kloft M. Pfreundschuh M: Treatment of refractory Hodgkin’s disease with an anti-CD16/CD30 bispecific antibody. Blood. 1997;89(6):2042–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Borghaei H, Alpaugh RK, Bernardo P, Palazzo IE, Dutcher JP, Venkatraj U, Wood WC, Goldstein L, Weiner LM. Induction of adaptive anti-HER2/neu immune responses in a phase 1B/2 trial of 2B1 bispecific murine monoclonal antibody in metastatic breast cancer (E3194): A trial coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Immunother. 2007;30(4):455–467. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31803bb421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fury MG, Lipton A, Smith KM, Winston CB, Pfister DG. A phase-I trial of the epidermal growth factor receptor directed bispecific antibody MDX-447 without and with recombinant human granulocyte-colony stimulating factor in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(2):155–163. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0357-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]