Abstract

Double electron-electron resonance (DEER) spectroscopy was used to determine the conformational state in solution for the heme monooxygenase P450cam when bound to its natural redox partner, putidaredoxin (Pdx). When oxidized Pdx was titrated into substrate-bound ferric P450cam, the enzyme shifted from the closed to the open conformation. In sharp contrast however, the enzyme remained in the closed conformation when ferrous-CO P450cam was titrated with reduced Pdx. This result fully supports the proposal that binding of oxidized Pdx to P450cam opposes the open to closed transition induced by substrate binding. However, the data strongly suggest that, in solution, binding of reduced Pdx to P450cam does not favor the open conformation. This supports a model in which substrate recognition is associated with the open-to-closed transition and electron transfer from Pdx occurs in the closed conformation. The opening of the enzyme in the ferric-hydroperoxo state following electron transfer from Pdx would provide for efficient O2 bond activation, substrate oxidation and product release.

The cytochrome P450 superfamily, which includes more than 15,000 sequences found in most organisms from bacteria to humans 2, serves essential biological roles ranging from sterol biosynthesis to drug metabolism. These heme containing monooxygenases catalyze the oxidation of organic substrates by molecular O2 (RH + O2 + 2H+ + 2e− → ROH + H2O). A series of ordered steps precedes O-O bond activation and cleavage to create the catalytically competent Compound I intermediate 3. These steps include substrate binding, one-electron reduction, O2 binding, a second one-electron reduction, proton delivery, and O-O bond cleavage 4. The source of electrons depends on the type of P450. While microsomal P450s utilize FAD/FMN containing cytochrome P450 reductases, most mitochondrial and bacterial P450s use separate ferredoxins and ferredoxin reductases 5.

Reduction and O-O bond activation are believed to be carefully controlled by the enzyme to prevent oxidative damage and unproductive side reactions. For many P450s, this control appears to be coupled to structural changes associated with substrate binding and recognition 6–12. In the archetypical bacterial enzyme P450cam from Pseudomonas putida 13, binding of the substrate camphor induces a transition from an open to closed conformation in both the crystal 12 and solution states 14. Interestingly, it was the open conformation in which the structure near the active site showed remarkable similarities to that of the ferrous O2 complex, including changes in the I helix bulge, a reorientation of Thr-252 and inclusion of the catalytic water above the heme 12, each of which have been proposed to be important in O-O bond cleavage 15,16. On this basis, it was proposed that the conformational shift between open and closed states might be coupled to the known effector function upon binding its reductase, putidaredoxin (Pdx) 12.

The structure of a covalently linked complex between P450cam and Pdx has recently been reported 17, providing significant new insight into these issues. While the protein contacts in this complex are in general agreement with previous mutagenesis 18–22 and spectroscopic studies 23–26, the structure of the P450cam-Pdx complex was observed to be in the open conformation for both crystals grown in the oxidized state and for crystals that were subsequently reduced with dithionite. Transition to the open conformation resulted in the changes noted above in the I helix, Thr-252 and the water network, allowing Tripathi et al. to conclude that the effector function of Pdx binding was indeed associated with conversion of the enzyme to the open conformation 17. While these results provide a paradigm shift in the understanding of P450 catalysis, they also leave some important questions unresolved. It is likely that the structure of the P450cam-Pdx complex was not adversely affected by the covalent tether, because two different linkages were examined in the study. Second, it is possible that the oxidized structure was affected by at least some degree of X-ray induced reduction. Most importantly, the reduced structure was obtained by soaking crystals of the oxidized complex with dithionite. As we have observed that crystals of substrate-free open P450cam do not convert to the closed state upon soaking with substrate 12, it is possible that the structure of the chemically reduced P450cam-Pdx complex remained trapped in the open conformation by crystal packing effects. Therefore it is important to characterize the conformational states of the P450cam-Pdx complex both in oxidized and reduced states in solution.

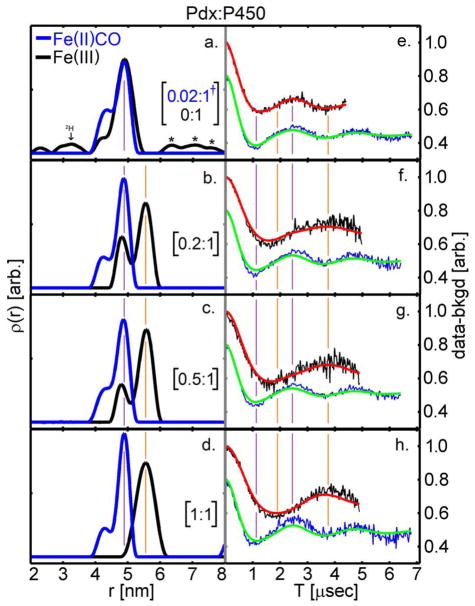

Double Electron-Electron Resonance (DEER) was used to determine the solution conformational states of P450cam in complex with Pdx. Two spin-labels were placed on P450cam such that the distance between spins can be determined from their dipolar coupling by DEER 27. Samples of the P450cam-(4S,2C) mutant containing two surface cysteines at positions 48 and 190 were labeled with MTSL ((1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-Δ3-pyrroline-3-methyl) methanethiosulfonate) 14. Figure 1 shows background subtracted X-band DEER traces and their corresponding distance distributions using Tikhonov regularization 28. We have previously shown that measured spin-spin distances of 4.8 nm and 5.6 nm from such DEER data represent the closed substrate-bound and open substrate-free states of P450cam, respectively 14. As shown in Figure 1, in the absence of Pdx and the presence of 1 mM camphor, the major peak in the distance distribution appeared at 4.8 nm for both ferric and CO-bound ferrous P450cam, indicating that both forms are in the closed conformation (Figure 1a). A small peak in the distance distribution at 4.3 nm was also observed for both samples, and most likely results from a minor alternate MTSL rotamer.

Figure 1.

X-band DEER at 30K for the titration of Pdx with aerobic camphor-bound P450cam (black) and with anaerobic camphor-bound P450cam under reducing conditions (blue). †In panel a., Pdx:P450 was 0.02:1 for the Fe(II)CO species, whereas it was 0:1 for the Fe(III) species. Deuterium modulations (2H) and background subtraction errors(*) in panel a. are as demarcated. The closed and open states are marked with the purple and orange lines, respectively.

When the ferric spin-labeled P450cam-(4S,2C) was titrated with 0.2, 0.5 and 1.0 molar equivalents of oxidized Pdx, a clear and progressive change in the DEER echo modulation frequency was observed (Figure 1e–h). This results in a shift in the peak of the distance distribution from 4.8 nm to 5.6 nm (Figure 1a–d), which corresponds exactly to that for conversion from the closed to the open conformation 14. Quantitation of the relative contribution of the two conformations is challenging due to the different effects of low- and high-spin heme on MTSL spin relaxation, but the qualitative effect clearly shows that addition of oxidized Pdx to the closed substrate-bound enzyme causes its conversion to the open state. Moreover, EPR measurements on these samples showed a decrease in the amount of high-spin heme as Pdx is titrated into P450cam (Figure S1). It has been known for many years that Pdx binding to P450cam induces an increase of the low-spin species 29,30, and in hindsight these results are consistent with the conversion from the closed to the open state.

In stark contrast to the above results, Figure 1 shows that samples of ferrous-CO P450cam display very well defined DEER modulations with no significant changes upon addition of reduced Pdx. Instead the spin-spin distance remains at 4.8 nm, exactly that characteristic of the closed conformation. UV/Vis spectra of these samples showed the characteristic Soret peak at 446 nm (Figure S2). As many previous observations have shown specific interactions between ferrous-CO P450cam and reduced Pdx 25,26,31,32, we consider it unlikely that the ferrous CO P450cam does not bind to reduced Pdx in our samples. Thus, DEER measurements show that in solution, addition of reduced Pdx does not result in conversion of substrate-bound ferrous-CO P450cam from the closed to the open state.

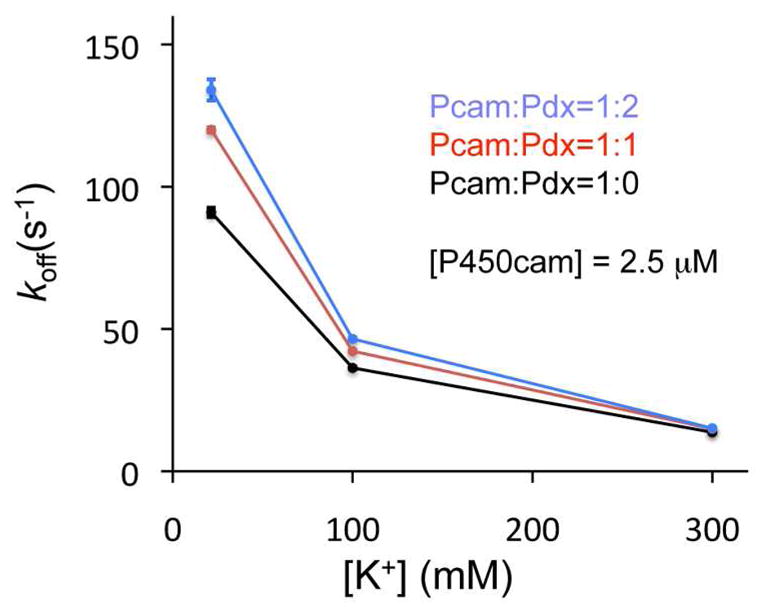

To provide additional support that oxidized Pdx causes a shift in enzyme conformation, the rate of camphor dissociation from P450cam was measured as a function of [Pdx] and [K+] by stopped-flow mixing with the strong-binding competitive inhibitor metyrapone. Figure 2 shows that the rate of camphor dissociation further increases in the presence of Pdx at low [K+]. The camphor dissociation rate was not influenced by oxidized Pdx at high salt concentrations, possibly because of disruption of the salt bridge between P450cam-Arg112 and Pdx-Asp38. These results are consistent with the observation that oxidized Pdx binding to P450cam results in conversion to the open conformation.

Figure 2.

Effects of oxidized Pdx on camphor dissociation from ferric P450cam. The rate of camphor dissociation was calculated from the spectral change from 391 nm (camphor-bound) to 421 nm (metyrapone-bound) 1

This study supports recent results by X-ray crystallography 17 suggesting that the P450cam-Pdx complex favors the open conformation in the oxidized state. Importantly, our results show that this effect is observed in the solution state, and that addition of oxidized Pdx to the substrate-bound closed conformation causes its conversion to the open conformation. This removes any possibility of crystal contacts or X-ray induced reduction as the source of the effect. In hindsight, a significant body of previous work also supports this observation. For example, resonance Raman 30 and EPR 29 studies have shown that oxidized Pdx shifts the spin state of P450cam from high- to low-spin even in the presence of camphor. In addition, Glascock et al. observed that oxidized Pdx binding to oxyferrous P450cam increased the rate of auto-oxidation by 100-fold 33.

Our results also show that in solution, the ferrous-CO state of the enzyme remains in the closed substrate-bound conformation upon addition of reduced Pdx. Also, while small changes have been noted by NMR for both proximal and distal residues upon binding reduced Pdx to ferrous-CO P450cam, a large change in structure was not indicated 34. However, these conclusions appear to contrast with the results of Tripathi et al.17 in which dithionite reduced crystals did not cause a shift from the open conformation seen in the oxidized complex. We propose three possible explanations for this difference. First, the effects of Pdx binding on the ferrous and ferrous-CO states may be distinct. The former may represent the state of the complex prior to O2 binding, while the latter may more accurately reflect the state before the second electron transfer step. Second, it is possible that the interactions between Pdx and the enzyme are different for the ferrous CO complex and the ferrous O2 complex. DEER studies of the ferrous and ferrous-O2 complexes with Pdx are under active investigation to provide insight into this important issue. Third, to account for the observation of the open conformation in the dithionite reduced crystals, we propose that the complex becomes trapped in the open conformation during crystallization of the oxidized forms, and resists conformational change upon subsequent reduction. This is supported by our observation that crystals of the open conformation do not convert to the closed conformation upon soaking in substrate12.

As our DEER results suggest that reduced Pdx favors the closed state of substrate bound P450cam, we propose that ET may also occur in this state. In this view, if the effector function of Pdx results from the redox state dependent triggering of the closed to open transition, this would occur naturally as a slow conformational transition following the second electron transfer from Pdx. We propose that a redox-dependent conformational change induced by Pdx binding to P450cam permits such a dual role. Whether that also occurs during the first reduction remains uncertain. It should be also noted that the effector function of Pdx may not require a transition of P450cam from the closed to the completely open state, as we have previously observed an intermediate conformation for some tethered substrates that also results in occupation of the catalytic water 35,36.

In summary, our observations in solution are consistent with the recently proposed model for Pdx effector function 17, but with one important difference. In this view, substrate recognition by P450cam is associated with conversion from open to closed conformation. The same open and closed states have been observed by X-ray crystallography 12 and DEER spectroscopy 14 and for a large number of tethered substrate analogs 36. However our results suggest that binding of reduced Pdx to the substrate bound closed conformation does not cause conversion to the open conformation but instead allows ET to occur in the closed state if substrate is bound. As soon as the second electron is transferred, the system will exist as the ferric hydroperoxo complex bound to oxidized Pdx. It is this state that we propose converts to the open conformation. Further clarification of these possibilities is under active investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the NIH (GM41049 to D.B.G.) and the Department of Energy (DE-FG02-09ER16117 to R.D.B.).

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Shu-Hao Liou, Xiaoxiao Shi, Mo Zhang and discussions with Professor T.L. Poulos.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information. Detailed experimental methods, and additional data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Griffin BW, Peterson JA. Biochemistry. 1972;11:4740. doi: 10.1021/bi00775a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson DR. Hum Genomics. 2009;4:59. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-1-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rittle J, Green MT. Science. 2010;330:933. doi: 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denisov IG, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Schlichting I. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2253. doi: 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hannemann F, Bichet A, Ewen KM, Bernhardt R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:330. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, Poulos TL. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:140. doi: 10.1038/nsb0297-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouellet H, Podust LM, de Montellano PRO. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708734200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SY, Yamane K, Adachi S, Shiro Y, Weiss KE, Maves SA, Sligar SG. J Inorg Biochem. 2002;91:491. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(02)00446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu LH, Fushinobu S, Ikeda H, Wakagi T, Shoun H. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1211. doi: 10.1128/JB.01276-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yano JK, Koo LS, Schuller DJ, Li H, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Poulos TL. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao B, Guengerich FP, Voehler M, Waterman MR. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee YT, Wilson RF, Rupniewski I, Goodin DB. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3412. doi: 10.1021/bi100183g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katagiri M, Ganguli BN, Gunsalus IC. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:3543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoll S, Lee YT, Zhang M, Wilson RF, Britt RD, Goodin DB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207123109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlichting I, Berendzen J, Chu K, Stock AM, Maves SA, Benson DE, Sweet RM, Ringe D, Petsko GA, Sligar SG. Science. 2000;287:1615. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagano S, Tosha T, Ishimori K, Morishima I, Poulos TL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tripathi S, Li H, Poulos TL. Science. 2013;340:1227. doi: 10.1126/science.1235797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unno M, Shimada H, Toba Y, Makino R, Ishimura Y. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koga H, Sagara Y, Yaoi T, Tsujimura M, Nakamura K, Sekimizu K, Makino R, Shimada H, Ishimura Y, Yura K. Febs Lett. 1993;331:109. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80307-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura K, Horiuchi T, Yasukochi T, Sekimizu K, Hara T, Sagara Y. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1207:40. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sligar SG, Debrunner PG, Lipscomb JD, Namtvedt MJ, Gunsalus IC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:3906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuznetsov VY, Blair E, Farmer PJ, Poulos TL, Pifferitti A, Sevrioukova IF. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pochapsky TC, Lyons TA, Kazanis S, Arakaki T, Ratnaswamy G. Biochimie. 1996;78:723. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(97)82530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang W, Pochapsky SS, Pochapsky TC, Jain NU. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:349. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tosha T, Yoshioka S, Takahashi S, Ishimori K, Shimada H, Morishima I. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pochapsky SS, Pochapsky TC, Wei JW. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5649. doi: 10.1021/bi034263s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeschke G. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2012;63:419. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032511-143716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeschke G, Chechik V, Ionita P, Godt A, Zimmermann H, Banham J, Timmel CR, Hilger D, Jung H. Appl Magn Reson. 2006;30:473. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipscomb JD. Biochemistry. 1980;19:3590. doi: 10.1021/bi00556a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Unno M, Christian JF, Benson DE, Gerber NC, Sligar SG, Champion PM. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6614. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimada H, Nagano S, Ariga Y, Unno M, Egawa T, Hishiki T, Ishimura Y, Masuya F, Obata T, Hori H. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Unno M, Christian JF, Sjodin T, Benson DE, Macdonald IDG, Sligar SG, Champion PM. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glascock MC, Ballou DP, Dawson JH. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505426200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asciutto EK, Madura JD, Pochapsky SS, Ouyang B, Pochapsky TC. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:801. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hays AMA, Dunn AR, Chiu R, Gray HB, Stout CD, Goodin DB. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:455. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee YT, Glazer EC, Wilson RF, Stout CD, Goodin DB. Biochemistry. 2011;50:693. doi: 10.1021/bi101726d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.