Abstract

Aims: Recent studies have suggested that in addition to oxygen transport, red blood cells (RBC) are key regulators of vascular function by both inhibiting and promoting nitric oxide (NO)-mediated vasodilation. Most studies assume that RBC are homogenous, but, in fact, they comprise cells of differing morphology and biochemical composition which are dependent on their age, parameters that control NO reactions. We tested the hypothesis that distinct RBC populations will have differential effects on NO signaling. Results: Young and old RBC were separated by density gradient centrifugation. Consistent with previous reports, old RBC had decreased levels of surface N-acetyl neuraminic acid and increased oxygen binding affinities. Competition kinetic experiments showed that older RBCs scavenged NO∼2-fold faster compared with younger RBC, which translated to a more potent inhibition of both acetylcholine and NO-donor dependent vasodilation of isolated aortic rings. Moreover, nitrite oxidation kinetics was faster with older RBC compared with younger RBC; whereas no differences in nitrite-reduction kinetics were observed. This translated to increased inhibitory effect of older RBC to nitrite-dependent vasodilation under oxygenated and deoxygenated conditions. Finally, leukodepleted RBC storage also resulted in more dense RBC, which may contribute to the greater NO-inhibitory potential of stored RBC. Innovation: These results suggest that a key element in vascular NO-homeostasis mechanisms is the distribution of RBC ages across the physiological spectrum (0–120 days) and suggest a novel mechanism for inhibited NO bioavailability in diseases which are characterized by a shift to an older RBC phenotype. Conclusion: Older RBC inhibit NO bioavailability by increasing NO- and nitrite scavenging. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 1198–1208.

Introduction

Nitric oxide (no) plays critical and diverse functions that are integrated within mechanisms controlling vascular homeostasis. This is reflected by the fact that inhibited or aberrant NO signaling, secondary to decreased formation and/or increased NO scavenging, underlies endothelial dysfunction and the pathogenesis of cardiovascular and other inflammatory diseases (14). The metabolic fate of NO production in the vasculature is largely oxidation to nitrite and nitrate (12). Administration of NO scavengers, or inhibitors of NO formation, leads to a rapid loss of NO-dependent signaling, which is manifested in, for example, hypertension. However, it is now appreciated that in the case where this involves oxidation of NO to nitrite or nitrate, it does not represent a complete inactivation of NO signaling per se, as mechanisms operational under biological conditions (that require lowering oxygen tensions and pH) have been identified that reduce nitrate to nitrite, and nitrite back to NO (26, 32, 33, 55, 57). This paradigm has been supported by many recent studies, and nitrite/nitrate therapies are being tested as potential modalities to replete NO signaling in multiple disease settings (4, 6, 26, 55). Therefore, in the context of these new findings, it is important to understand the mechanisms that regulate NO concentrations, specifically the interconversion between NO, nitrite, and nitrate. This understanding will, in turn, inform on disease mechanisms and potential therapeutics.

Innovation.

Erythrocytes are known modulators (activators and inhibitors) of nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability. However, erythrocytes comprise a spectrum of heterogeneous cells that are characterized by different ages, biochemical and morphological phenotypes. We show here that across the physiologic spectrum of erythrocyte ages, substantial differences in how these cells modulate NO-bioactivity (via altered NO- and nitrite oxidation kinetics) exist. These data provide novel insights into how erythrocytes control NO signaling and suggest that in diseases where the physiologic spectrum of erythrocyte ages is perturbed, significant perturbation in vascular NO homeostasis is also predicted.

Red blood cells (RBC) and hemoglobin have been discussed extensively in the context of NO metabolism, as both inhibitors and stimulators of NO-dependent signaling (36). Inhibition occurs via relatively rapid reactions of either oxy- or deoxyhemoglobin with NO forming nitrate or nitrosylheme, respectively (reactions 1 and 2). With cell-free hemoglobin, the rate constants for these reactions are∼2–6×107 M−1 s−1 (3).

|

Encapsulation of hemoglobin within the RBC slows this rate constant by∼500–1000-fold, which combined with a flow-dependent RBC-free zone is thought to be critical in ensuring that NO signaling in vivo is viable (2, 24, 30, 31, 42, 56). This is exemplified by data showing that cell-free hemoglobin arising from hemolysis at low micromolar concentrations (compared with millimolar concentrations present in RBC), for example during sickle cell crisis or when administered during acellular hemoglobin blood substitute therapy or transfusion with stored RBC, potently inhibits NO signaling and causes hypertension and inflammation (27). How hemoglobin encapsulation slows NO-scavenging reactions remains under investigation, with barriers created that either slow diffusion of NO to the RBC surface, entry across the membrane, or diffusion inside of the RBC being discussed as possible mechanisms (2, 3, 31, 56). In contrast, RBC have also been proposed to play key roles in supporting NO signaling by multiple mechanisms (36) and in the context of the paradigm outlined earlier specifically, by reduction of nitrite to NO by deoxyhemoglobin (reaction 3). Importantly, nitrite is also oxidized to nitrate by oxyhemoglobin (see Discussion and reaction 4, below). Reactions 3 and 4 underscore the proposal that hemoglobin-dependent nitrite reduction and stimulation of NO signaling is integrated within allosteric mechanisms regulating oxygen delivery. Moreover, since nitrite may be a substrate for NO formation by other metalloproteins as well, nitrite oxidation to nitrate should also be considered as a mechanism that may significantly affect NO homeostasis by modulating substrate nitrite levels.

The discussion stated earlier highlights that RBC can affect both sides of the balance between NO scavenging and stimulation of NO signaling (36). While it is clear that hemolysis dramatically disrupts how RBC and hemoglobin affect NO signaling with implications for the pathogenesis of acute hemolytic disorders and transfusion therapeutics noted, whether NO- or nitrite oxidation or reduction by intact RBC is altered has received little attention. Our recent studies suggested that during RBC storage in the blood bank, significant increases in NO scavenging and nitrite oxidation occurred due to changes in RBC morphology (which is predicted to be associated with increased surface area to volume ratio), which, in turn, led to enhanced inhibition of NO-dependent vasodilation (51). Furthermore, previous studies have shown that antioxidants present in the RBC may slow nitrite oxidation reactions (35, 39, 48), and lower antioxidant levels in older RBC have been documented (21, 22, 46, 52). Thus, biochemical and structural/morphological perturbations in RBC could significantly alter how RBC regulate the balance between NO scavenging and stimulation of NO signaling. Since any preparation of RBC collected from healthy donors is, in fact, a heterogeneous population of cells comprising different ages (human RBC have a life span of∼120 days), which are characterized by different sizes, densities, surface areas, volumes, and antioxidant status, we tested the hypothesis that younger versus older RBC will exhibit significant differences in how they metabolize and affect NO- and nitrite-dependent signaling.

Results

Characterization of RBC heterogeneity by age in vivo

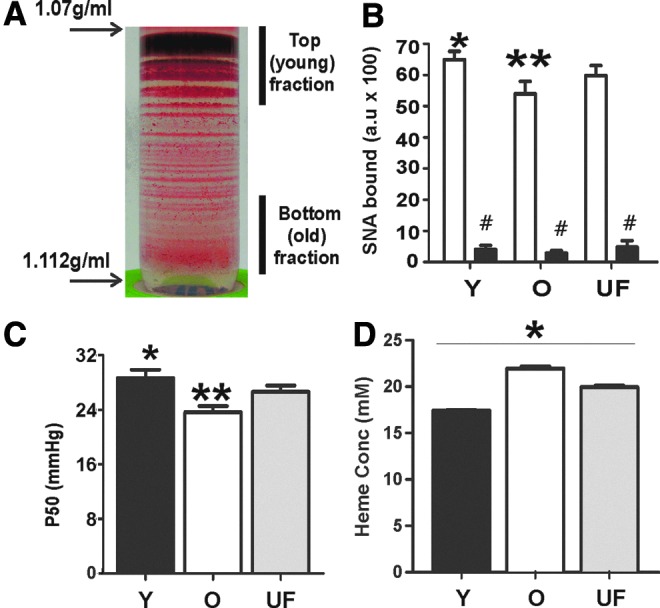

RBC were separated by density gradient (1.07–1.112 g/ml) centrifugation. Figure 1A shows a representative photograph showing many distinct RBC populations (indicated by different density bands) which reflect the physiologic spectrum of RBC ages that are populated at any given time. To test how RBC aging affects reactions with NO or nitrite, RBC were pooled from either the top or bottom fractions as indicated (Fig. 1A) and designated as representative of young and old RBC, respectively. The average recovery (% of total RBC added) in the young and old fractions was 68.4±0.44 and 10.1±0.04 (mean±standard error of the means [SEM], n=3), respectively. Young and old fractions were further characterized biochemically by measurement of surface sialic acid, hemoglobin oxygen affinity, and heme concentration, parameters that have been reported to change with RBC age (17, 19, 45, 49). Consistent with earlier studies (8, 46), Figure 1B and C shows that surface sialic acid expression was decreased by∼20% and P50 (oxygen tension at which hemoglobin is 50% saturated) by∼6 mmHg in older RBC. Figure 1D shows that heme concentrations in packed RBC are higher in old versus young RBC. This is a result of smaller/denser RBC, as the heme per RBC (in nmol/1×107 cells) was not significantly different between any group, being 0.022±0.0001, 0.021±0.0002, and 0.022±0.0005 for young, old, and unfractionated (UF) RBC, respectively (mean±SEM, n=3).

FIG. 1.

Characterization of young and old RBC. RBC were isolated from whole blood and left UF, or separated by density gradient centrifugation. (A) Representative image of RBC after density gradient centrifugation and designation of young (Y) and old (O) RBC fractions. (B) Surface sialic acid content was determined by SNA-FITC binding with (■) or without (□) neuraminidase treatment. *p<0.05 relative to UF or old RBC, **p<0.01 relative to UF by one way RM-ANOVA with Tukey post test. #p<0.05 relative to respective RBC age by paired t-test. (C) P50 for oxygen binding to Y, O, or UF hemolysates was measured by tonometry. *p<0.01 relative to old RBC, **p<0.05 relative to UF RBC by one-way RM-ANOVA with Tukey post test. (D) Heme concentration in packed RBC. *p<0.01 between all groups one-way RM-ANOVA with Tukey post test All data are mean±SEM, n=3–7. RBC, red blood cells; RM-ANOVA, repeated measures-analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the means; SNA-FITC, Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA)-fluorescein isothiocyantae; UF, unfractionated. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Effects of RBC age on NO reactions and signaling

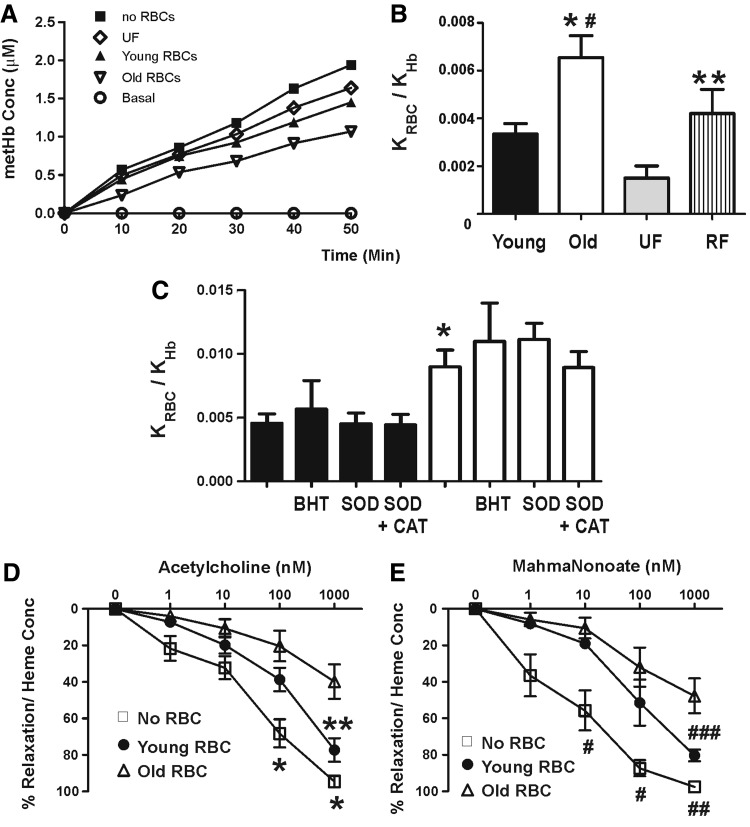

Since older RBC are morphologically and structurally distinct to young RBC, we hypothesized that NO-scavenging rates by these cells would also be distinct. A competition kinetic assay was employed to determine the relative rate constants (for intact RBC vs. cell free hemoglobin) for NO dioxygenation. Figure 2 shows representative traces of NO-dependent formation of cell-free metHb in the absence or presence of young and old RBC. The degree to which the rate of metHb formation deviates in the presence of RBC as compared with preparations containing only cell-free hemoglobin reflects the competition between cell-free and erythrocytic hemoglobin for NO; a slower rate of metHb formation reflects faster rates of NO dioxygenation by erythrocytic hemoglobin. Figure 2B shows that the relative rate constant for NO dioxygenation by old RBC is∼2-fold greater than by young RBC. Surprisingly, UF RBC displayed NO dioxygenation kinetics which did not fall between young and old RBC, but rather lower than that observed for young RBC. We, therefore, also tested RBC that were recombined after fractionation (RF) after density gradient separation. For these experiments, all RBC were recovered after separation (yield being 99.4%±0.3%, mean±SEM, n=3). Figure 2B shows that these RBC exhibited NO-dioxygenation kinetics that were not different from the young fraction, but significantly higher than UF RBC. Older RBC have lower antioxidant capacities, which, in turn, could lead to increased steady-state oxidant (superoxide and lipid radicals) levels that may contribute to accelerated rates of NO dioxygenation. Figure 2C shows that butylated hydroxy-toluene (BHT) (lipid radical scavenger), superoxide dismutase (SOD, scavenge superoxide), or SOD+catalase (to scavenge superoxide and hydrogen peroxide) had no effect on increased rates of NO dioxygenation by older RBC, suggesting that any increase in reactive species due to diminished antioxidant activities is not a major effector of increased NO-dioxygenation kinetics observed. To test whether increased NO-scavenging rates translate into a greater inhibition of NO-dependent signaling, the effects of young and old RBC on acetylcholine or MahmaNonoate (NO-donor)-dependent vasodilation was determined (Fig. 2D, E). Both young and old RBC inhibited NO-dependent vasodilation, but the inhibitory effects of older RBC were significantly more potent compared with younger RBC. Differential concentrations of cell-free hemoglobin in bioassay chambers could account for different inhibitory effects. However, no differences in cell-free hemoglobin were observed between young and old RBC (cell-free heme concentrations at the end of experiments, in bioassay chambers being 1.9±0.22 μM and 2.4±0.23 μM for young and old RBC, respectively (p=0.13 by t-test, data are mean±SEM, n=6). Furthermore, hemoglobin-containing microparticles are readily formed from RBC and react with NO at rates that are similar to cell-free hemoglobin (11). Microparticle levels were measured in UF, young, or old RBC stored at 20°C for 2 h (for most studies, RBC were first washed to remove microparticles and were then stored on ice for<30 min before addition for kinetic or vasodilation studies). No differences in microparticle levels were observed between any RBC preparation, with levels (expressed as percent of total RBC) being 0.21±0.07, 0.26±0.09, and 0.43±0.18 for UF, young, and old RBC, respectively (data are mean±SEM, n=3. p=0.62 by 1-way repeated measures-analysis of variance [RM-ANOVA]). Finally, we note that previous studies have shown∼2-fold lower methemoglobin reductase activities in older RBC compared with younger RBC (60). This could, in turn, affect NO-dioxygenation kinetics by altering the concentration of oxyhemolobin in the RBC. However, no differences in methemoglobin concentrations in pRBC were observed (264±10.3 μM in young and 270.2±38.8 μM in old; data are mean±SEM, n=3).

FIG. 2.

Effect of RBC age on NO-scavenging kinetics and signaling. (A) Shows representative traces for cell-free methemoglobin formation after addition of spermine NONOate (10 μM) to cell-free oxyhemoglobin (7 μM) in the presence or absence of young, old, or UF RBC (7% Hct) as shown. (B) Shows relative rate constant for NO dioxygenation by RBC hemoglobin compared with cell-free hemoglobin (KRBC/KHb). Data are mean±SEM (n=6). *p<0.05 relative to young or RBC RF, #p<0.0001 relative to UF RBC, **p<0.05 relative to UF by one-way RM-ANOVA with Tukey post test. (C) Shows effects of BHT, SOD, or SOD+catalase on relative rate constant for NO dioxygenation by young (■) or old (□) RBC. *p<0.05 by one-way ANOVA with tukey post test. No effect of BHT, SOD, or SOD+catalase on young or old was observed. Data are mean±SEM (n=3–7). (D, E) Show, respectively, acetycholine and Mahmanonoate dose-dependent vasodilation of rat thoracic aorta at 21% O2 in Krebs–Henseleit buffer and in the absence (□) or presence of either young (•) or old RBC (▵). RBC were added at 0.3% Hct (final) and 30 s before the first dose of acetycholine or Mahmanonoate. Data show percent vasodilation normalized to the amount of RBC heme present in each vessel bath as described in Materials and Methods. Data are mean±SEM (n=3). *p<0.01 for control versus either young or old RBC groups, **p<0.001 between young and old RBC groups, #p<0.05 for control versus young RBC or #p<0.001 for control versus old RBC, ##p<0.001 for control versus old RBC, ###p<0.05 for young versus old RBC by two-way RM-ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons post test. NO, nitric oxide; RF, recombined after fractionation; SOD, superoxide dismutase; BHT, butylated hydroxytoluene; Hct, hematocrit.

Effects of RBC age on nitrite oxidation and reduction

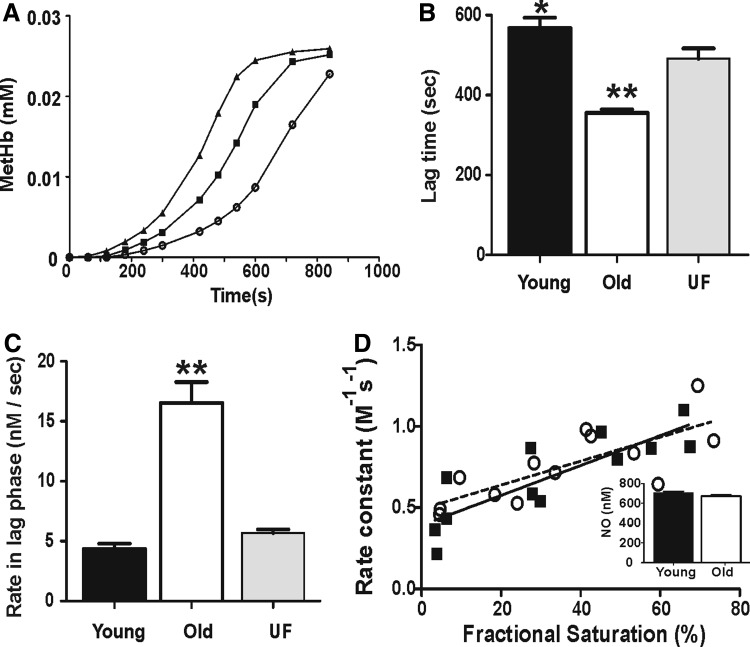

Nitrite-dependent oxidation of oxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin was measured by visible spectroscopy using hemolysates as described in Materials and Methods. As previously reported (29, 39), this reaction was autocatalytic characterized by an initial lag phase, where metHb formation was relatively slow, followed by a more rapid or propagation phase (Fig. 3A). Figure 3B and C shows, respectively, the lag times and rate within the lag phase for young, old, and UF RBC. Interestingly, the lag time was less, and the rate of metHb formation within the lag phase was faster for old RBC lysates compared with either young or UF RBC lysates. No change in the rate of metHb formation within the propagation phase between the different RBC groups was observed (not shown). In contrast to oxidation of nitrite by oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin reduces nitrite-forming NO (and methemoglobin), a reaction proposed to stimulate NO-dependent signaling during hypoxemia (38). Previous studies have shown that the rate constant for nitrite reduction, assessed by measuring loss of deoxyhemoglobin, increases by increasing oxygen fractional saturation, due to increased R-state character (5, 9, 18, 20, 41). Figure 3D shows that the rate constant for nitrite reactions with deoxyhemoglobin increased linearly with fractional saturation in both cases but did not differ between old and young RBC. This was confirmed by observing no differences in NO formation from deoxygenated hemolysates from young or old RBC (Fig. 3D, inset).

FIG. 3.

Effect of RBC age on nitrite oxidation and reduction. Nitrite (500 μM and 3 mM for oxidation and reduction experiments, respectively) was added to hemolysates containing oxyhemoglobin (25 μM) in phosphate-buffered saline+100 μM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid at 37°C and visible spectra acquired between 450 and 700 nm every 2 min. Formation of methemoglobin was determined by spectral deconvolution as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Shows representative methemoglobin formation profiles from old (▲), UF (■), and young (○) RBC. (B) Shows the lag time and (C) the rate of methemoglobin formation in the lag phase. Data are mean±SEM (n=4). *p<0.01 relative to UF RBC, **p<0.001 relative to UF and young RBC by one-way RM-ANOVA with Tukey post test. (D) Shows the rate constant for nitrite reduction by deoxyhemoglobin measured at different initial fractional saturations. Each data point represents individual replicates compiled from three separate RBC preparations (■=young RBC, ○=old RBC). Lines represent best fits by linear regression for young (solid line) and old (dashed line) with no differences between the slopes (p=0.5). Inset: NO formation after addition of nitrite to deoxygenated young or old RBC hemolysates was measured by ozone-based chemiluminesence. Data show mean±SEM (n=3).

Effect of RBC age on nitrite-dependent vasodilation

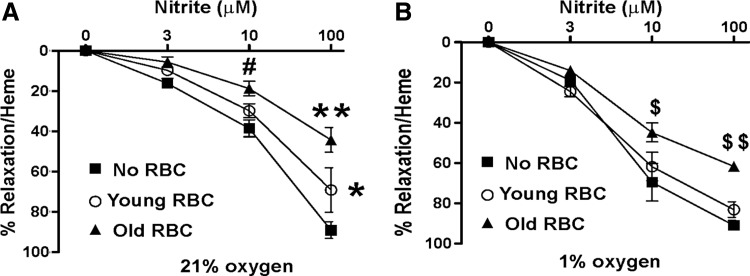

Figure 4A and B shows the effects of young and old RBC on nitrite-dependent vasodilation at 21% O2 (oxygenated) and 1% O2 (deoxygenated) conditions, respectively. Consistent with previous data, nitrite was a more potent vasodilator at the lower pO2. Both young and old RBC inhibited nitrite-dependent vasodilation at 21% O2, with the magnitude of inhibition being significantly greater for old RBC compared with young RBC. At low pO2, however, young RBC had no effect on nitrite-dependent vasodilation; whereas old RBC inhibited, albeit to a lesser extent compared with the degree of inhibition observed at 21% O2.

FIG. 4.

Effects of RBC age on nitrite-dependent vasodilation: Nitrite-dependent vasodilation of rat thoracic aorta was determined at 21% O2 (A) and 1% O2 (B) in the absence (■) or presence of young (○) or old (▲) RBC. Data are mean±SEM (n=3). *p<0.05 for control versus young and young versus old, **p<0.0001 and #p<0.01 for control versus old RBC; $p<0.05, $$p<0.01 for old versus control, and old versus young. All p-values calculated by two-way RM-ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons post test.

Effects of blood bank storage on RBC density distribution

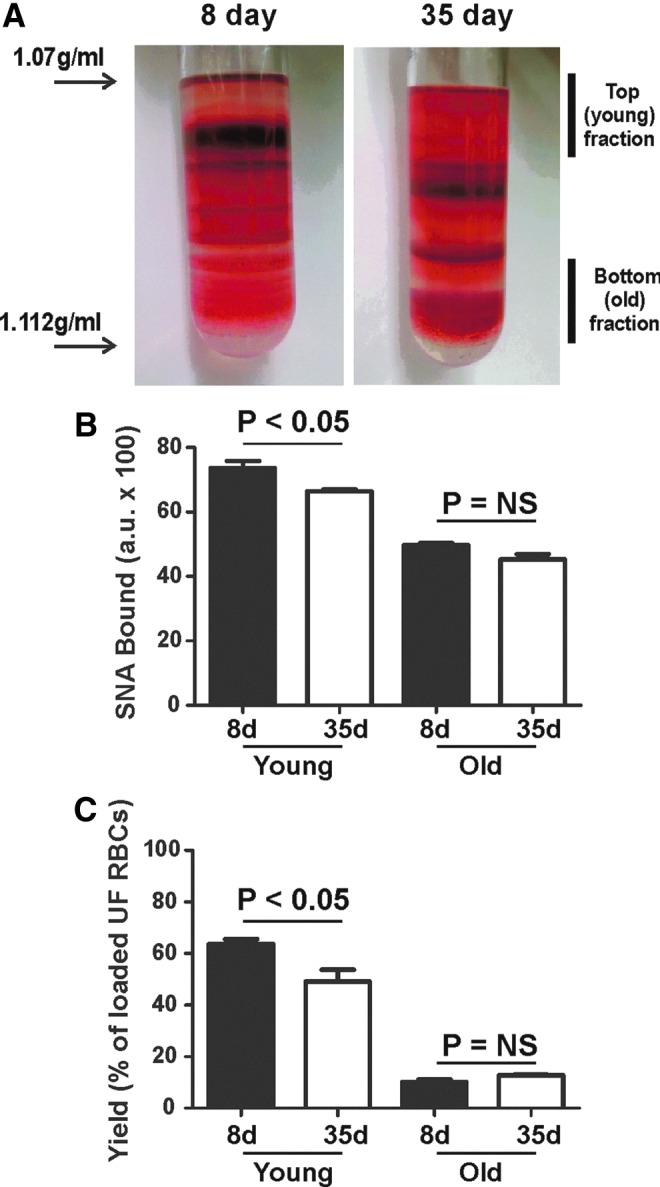

Our recent studies have shown that storage of leukodepleted RBC in the blood bank also results in increased rates of an NO and nitrite oxidation (51), albeit to a greater extent compared with changes observed here due to differences in the physiologic age of RBC. Previous studies have also shown that RBC storage in the blood bank results in RBC that are overall smaller and with increased density. Figure 5 compares density gradient profiles, and biochemical characteristics of RBC stored for either 8 or 35 days in the blood bank. Interestingly, RBC after 35 days of storage showed a shift toward a higher density compared with RBC stored for 8 days, indicating a greater percent of RBC that have an older phenotype. This was further indicated by Figure 5B and C, which showed, respectively, that Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA) content per RBC and yield are slightly but significantly lower in the young fraction of RBC stored for 35 days.

FIG. 5.

Characterization of young and old RBC from stored blood. RBC were purified from leukodepleted packed RBC stored in our institutional blood bank for either 8 or 35 days. (A) Shows representative images of RBC after density gradient centrifugation and designation of young and old fractions. (B) Shows surface sialic acid content determined by SNA-FITC binding. (C) Shows the yield of RBC in designated young and old fractions relative to the total number of RBC loaded onto density gradients. For (B, C), data are mean±SEM, n=3. Indicated p-values calculated by t-test. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Discussion

Human erythrocyte aging from reticulocytes to senescent cells occurs over 120 days. This process is accompanied by many biochemical, structural, and morphological changes that result in cells which are denser, have decreased antioxidant and glycolytic enzyme activities, higher oxygen affinities, and which express surface antigens that allow receptor mediated clearance (15, 46, 58). However, the potential that RBC of differing ages could differentially modulate vascular homeostasis functions remains untested. Data presented here suggest a novel functional implication in that older RBC may decrease NO bioavailability due to faster rates of NO scavenging and/or nitrite oxidation.

How RBC control NO metabolism and signaling has emerged as an important consideration for understanding the biological roles of this free radical in the vasculature. RBC may act as hubs through which both inhibition and stimulation of NO signaling may occur (36). Inhibition of NO signaling is a direct consequence of NO dioxygenation to nitrate by oxyhemoglobin, or heme-ligation by deoxyhemoglobin forming nitrosylhemoglobin (10). Stimulation of NO signaling may occur through a variety of proposed mechanisms that include expression of a functional endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in RBC (28), modulation of blood viscosity and hence shear-stress dependent activation of eNOS in the vascular wall (43), and hypoxia-dependent formation of NO via nitrite-reduction, ATP release (and subsequent vascular wall eNOS activation) or increased reactivity of S-nitrosohemoglobin (16, 47, 50). Despite the appreciation that RBC comprise a heterogeneous population of cells, that differ in shape, size, and biochemical composition, all of which are factors that affect how RBC react with NO and nitrite, surprisingly few insights into how NO bioavailability may be modulated across the physiological spectrum of RBC ages exist. Subasinghe and Spence have shown that older RBC have a diminished capacity to release ATP in response to mechanical deformation (52). Our data show that older RBC display accelerated NO-dioxygenation rates compared with younger RBC. Importantly, this may translate to a greater inhibition of NO bioavailability as reflected by a greater inhibition of NO-dependent vasodilation by older RBC. An important consideration is that although the rate constant for NO dioxygenation by older RBC is twofold higher than by young RBC, the former comprise only∼10% of the total RBC as defined in this study. The question remains as to what extent this 10% of total RBC or any increases in this pool affects NO bioavailability. Doubling of the old RBC population to 20%, with a concomitant decrease in all other RBC from 90% to 80%, would increase overall inhibitory potential of all RBC by∼8%. Little is known regarding to what extent increases in the amount of older RBC can occur in different pathologic settings, although as noted next in pre-eclampsia an increase of older RBC by∼10% relative to normal pregnancy has been reported (34). More importantly is the fact that a modest inhibition of NO bioavailability can lead to significant changes in biological function as exemplified by the fact that many environmental stressors (e.g., smoking, hypercholesterolemia) have been shown to cause modest deficits in NO bioavailability which are, however, associated with significant increases in chronic inflammatory diseases. Another example is that a 20% decrease in vessel diameter (i.e., a 20% inhibition of NO signaling observed in in vitro bioassay experiments) would translate to∼2.4-fold inhibition in blood flow according to Poiseuille's equation. We acknowledge the weaknesses associated with extrapolation of kinetic data to predictions on effects on NO bioavailability, and hypothesize that relatively small changes in the population of older RBC may have significant consequences on vascular homeostasis mechanisms.

Nitrite oxidation was also faster with older RBC; however, no change in nitrite reduction kinetics was observed, suggesting that with older RBC, the balance previously described between nitrite-dependent NO formation and NO scavenging by hemoglobin (23) will be shifted to the latter. Consistent with this hypothesis, at low oxygen tensions, young RBC did not inhibit nitrite-dependent vasodilation; whereas older RBC did. These data, taken together with other reports demonstrating attenuated ATP-release (52), indicate that the relative distribution of RBC ages will be an important factor in controlling vascular NO-signaling.

The kinetics of NO scavenging by RBC is regulated by diffusion barriers that slow NO access to hemoglobin (relative to cell-free hemoglobin). The basis of these diffusion barriers remains under investigation with both the unstirred layer and membrane permeability discussed as potential mechanisms (2, 3, 24, 30, 31, 42, 56). For the same amount of encapsulated hemoglobin, an increase in the surface area to volume ratio in RBC is predicted to increase NO-dioxygenation rates exemplified during blood bank storage of RBC (51). Interestingly, despite RBC volume and size decreasing during RBC maturation, the surface area to volume ratio for human RBC, in fact, increases (58). We posit that this biophysical property of older versus younger RBC accounts for the increased rates of NO dioxygenation and enhanced inhibition of NO-dependent vasodilation shown in Figure 2. No differences in microparticle formation was observed between young and old RBC under the employed experimental conditions, further suggesting that differences in NO-dioxygenation kinetics are intrinsic to the intact RBC. Notably, RBC that underwent density gradient separation showed higher rates of NO-dioxygenation compared with those which did not (compared RF vs. UF data in Fig. 2B) and suggest that centrifugation and/or the exposure to percoll affects properties that govern NO diffusion. What underlies this effect remains unclear, but we note that both young and old RBC were subjected to the same procedure, allowing a direct comparison to be made with regard to NO-scavenging kinetics.

To our knowledge, no systematic studies testing how older versus younger RBC stream in the circulation have been performed. Since older RBC are denser, and display a greater tendency for RBC–RBC adhesion, due to decreased surface negative charge, we speculate that older RBC will be found predominantly in the center of the flow. This, in turn, would limit NO scavenging by increasing the diffusion distance between NO formation (from eNOS) and older RBC, which may be important in countering increased NO-dioxygenation rates. On the other hand, due to increased adhesivity, older RBC may more closely interact with the endothelium, which would decrease NO-diffusion distance and lead to an even greater inhibition of NO signaling. These perspectives are speculative and require experimental testing.

Hemoglobin-mediated nitrite oxidation, under condition of excess nitrite, is a multi-step autocatalytic reaction as recently described (39) that involves intermediate formation of H2O2 and NO2 radical (reactions 4–8):

|

The time dependence of this reaction is sigmoidal, with the transition from the initial lag to the latter maximum rate or propagation phase reflecting a transition from an H2O2-dependent to an NO2-dependent process (i.e., change in the rate limit from reaction 5 to reactions 6 and 7). In the RBC, the presence of H2O2-metabolizing systems (glutathione peroxidase, peroxiredoxin, and catalase) and molecules that react with the NO2 radical (e.g., glutathione, ascorbate) is critical in keeping nitrite oxidation relatively slow; therefore, although as previously noted, under physiologic conditions where nitrite levels are far lower than hemoglobin, limiting H2O2 and metHb concentrations are likely to be the predominant pathways that modulate nitrite oxidation (25). Interestingly, nitrite-dependent oxidation of oxyhemoglobin was faster with older versus younger RBC. This was demonstrated by a decrease in the lag phase duration and rate in the lag phase, with no differences observed in the rate of oxidation during the propagation phase. These data suggest that H2O2 formation and hemoglobin redox cycling between ferric and ferryl oxidation states is faster in older versus younger RBC, and is likely explained by the decrease in the activities of H2O2-metabolizing antioxidant systems in older RBC (7, 22, 54). In contrast to oxidation, nitrite reduction kinetics by deoxyhemoglobin were not affected by RBC age. However, since older RBC have higher oxygen affinities, at any given oxygen tension, the differing concentrations of deoxyhemoglobin are predicted to control nitrite reduction in relation to the bell-shaped dependence of this reaction on fractional saturation as previously described (9, 18). Older RBC inhibited nitrite-dependent vasodilation more so compared with young RBC. This is consistent with faster nitrite oxidation kinetics, but a role for increased rates of NO scavenging cannot be excluded, as nitrite-dependent vasodilation is an NO-dependent process.

As stated earlier, the relative distribution of RBC ages could affect vascular function via controlling NO bioavailability with our prediction being that a shift to an older RBC phenotype will lead to decreased NO bioavailability, a process implicated in numerous pro-inflammatory, pro-coagulative, and hypertensive disease states. Interestingly, RBC from young, healthy women comprise a higher proportion of younger cells compared with male counterparts (44). Moreover, different RBC age distributions have been documented in disease states as well. For example, a distribution to a younger RBC phenotype occurs during pregnancy; however, this does not occur during preeclampsia, a disease associated with decreased NO bioavailability (34). Our data would suggest that RBC in preeclamptic women would scavenge NO faster compared with normotensive pregnant women, which could then contribute to hypertension associated with this condition; a hypothesis that remains to be tested. In addition, the range of antioxidant activities in RBC isolated from older mice compared with younger mice (37 vs. 10 months) was shifted toward decreased levels, suggesting that a shift to an older RBC phenotype occurs during aging as well (1). We note, however, that other studies with humans suggest the opposite (40). Hypertension and increased cholesterol content are associated with decreased RBC surface sialic acid levels (17), a property associated with older RBC (see Fig. 1). Interestingly, decreased sialic acid content increased RBC aggregability; how this may affect reactions with NO and nitrite requires evaluation but it is interesting to speculate that altered RBC reactions may contribute to attenuated NO function in hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. In addition, recent studies have shown that increased red cell distribution width (RDW) is strongly associated with mortality in a number of inflammatory diseases (13, 37, 53). The RDW reflects the heterogeneity of RBC sizes, although information regarding the underlying nature for increased variation in RBC size in different diseases is not clear. Importantly, a shift in the spectrum of RBC ages to young or older cells will increase the RDW. Clearly, additional studies are required to test whether an increase in the relative number of older RBC will lead to significant increases in RDW, and whether the latter is associated with RBC that inhibit NO bioactivity. Finally, the results presented here complement our previous studies (51) documenting similar increases in NO- and nitrite oxidation by RBC storage in the blood bank over 42 days. Transfusion with older units of RBC have been shown to be associated with transfusion-related morbidity and mortality toxicity (59). A common mechanism may be the increased levels of RBC that display an older phenotype (based on density) in stored units (see Fig. 5). One area of interest in transfusion medicine is the quality of RBC collected for banking and transfusion. It is interesting to speculate that perhaps the RBC age distribution at the time of collection may affect development of storage lesion toxicity.

In summary, we show that RBC heterogeneity is an important consideration in evaluating NO-homeostasis mechanisms and that changes in the relative RBC age distribution have the potential to significantly affect NO signaling in the vasculature.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Percoll solution was obtained from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Piscataway, NJ). MahmaNONOate, spermine NONOate (SpNO), and N-monomethyl-l-arginine (L-NMMA) were obtained from Axxora Platform (San Diego, CA). Male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–250 g) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). All other materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All animal studies were performed following Institutional Animal Care and Use approved procedures.

RBC collection

Blood was collected from healthy donors (following Institutional Review Board approved protocols) and washed thrice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), pH 7.4, 4°C, by centrifugation (1500g for 5 min per wash and the supernatant discarded). In separate studies, leukodepleted packed RBCs were collected from segments from the UAB blood bank. RBC were washed as described next before use. All procedures followed Institutional Review Board approved protocols.

Density gradient fractionation of RBCs

Two milliliter of PBS-washed RBC (50% hematocrit [Hct]) were loaded onto Percoll (28 ml) density gradients ranging from 1.07 to 1.113 g/ml. Separation of the RBCs based on density was achieved by centrifugation at 20,000g, 4°C for 1 h. The top and bottom fractions (see Fig. 1) were collected (respective yield of pRBC were 800 and 100 μl) and washed (thrice with PBS containing 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4) to represent the young (low density) and old (high density) RBC age phenotypes.

RBC surface N-acetylneuraminic acid (sialic acid) measurement

An equal number of RBC (1×107 cells) from each RBC fraction were incubated with 1 μg/ml SNA-fluorescein isothiocyantae (FITC) in TBS+Ca2+/Mg2+ (1 mM) at room temperature for 10 min. The RBCs were separated from the supernatant by centrifugation (2000g for 5 min), and the relative fluorescence intensities of the unbound SNA was measured using a fluorescent plate reader. The SNA bound to the RBCs after incubation was calculated by the difference in relative fluorescent intensities with and without RBCs. Specificity of SNA binding to N-acetylneuraminic acid on the RBCs was confirmed by pre-treatment with Neuraminidase for 1 h at 37°C before incubation with SNA-FITC.

Measurement of oxygen binding affinity

Oxygen binding curves and calculation of the P50 to different RBC hemolysates were determined as previously described using a tonometer in PBS at 37°C (51). Specifically, RBC were lysed in deionized water (at a ratio of 1:5), and then diluted to∼20 μM heme in PBS. This protocol maintains the ratio of hemoglobin to allosteric effectors while allowing measurement of visible spectra (450–700 nm) without scattering associated with intact RBC.

Kinetic analysis of NO scavenging by RBCs

The rate of NO dioxygenation by RBC was determined using a competition kinetic assay as previously described (51, 56). Three experimental conditions were used, PBS+0.5% BSA containing either cell-free oxyHb (7 μM heme), oxyHb with SpNO (10 μM), or a suspension of RBC (7% Hct) plus oxyHb and SpNO. RBC were washed thrice with PBS at 1500g, 5 min before addition to remove any hemolysis-derived products that might have accumulated before the start of the experiment. Free hemoglobin concentrations were also assessed before addition of SpNO. Samples were placed in six-well tissue culture plates at room temperature and rocked gently on a rocking platform. After addition of SpNO, 0.5 ml samples were taken at every 10 min for 50 min and immediately centrifuged (20 s at 2000g) to separate RBC from the supernatant. The concentration of oxyHb and metHb in the supernatant was determined by visible light spectroscopy. The rates of cell-free oxyHb oxidation to metHb by SpNO, in the presence or absence of RBC, were measured, and relative rate constants for NO dioxygenation by RBC (KRBC) versus cell-free oxyHb (KHb) were calculated as described (51, 56). In some experiments, the effects of BHT (100 μM), SOD (100 U/ml)±catalase (100 U/ml) were tested by adding these compounds to RBC suspensions 1–2 min before addition of NO donor. It should be noted that since these experiments were performed at 7% Hct, different RBC heme concentrations (see Fig. 1D) were present for young and old RBC. Calculation of the relative rate constant (KRBC:KHb) was performed using the respective RBC heme concentrations present in the assay. Similarly, nitrite reduction or oxidation kinetics (described below) was performed under equivalent heme conditions.

Ex vivo aorta vasodilation

Thoracic aortas were isolated from male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–250 g) and cut into∼5 mm segments. Rings were suspended between two hooks connected to a force transducer and placed within a vessel bath chamber containing Krebs–Henseleit (KH) buffer at 21% O2 as previously described (51). After two rounds of KCl-induced contractions followed by washing with KH buffer, vessels were equilibrated with 21% or 1% oxygen in KH buffer at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. Vessels were pretreated with indomethacin (5 μM) and L-NMMA (100 μM) and precontracted with phenylephrine (200 nM at 21% O2 and 400 nM at 1% O2) before the addition of RBCs (0.3% hematocrit final concentration). L-NMMA was not added when acetylcholine-dependent responses were assessed. Once vessels had reached a stable tone, vasorelaxation was induced by the addition of cumulative doses of either the NO donor Mahma-NONOate or acetylcholine (at 21% O2 only) or sodium nitrite (at 21% O2 and 1% O2). Vasorelaxation was determined in the absence and presence of RBCs, and the time of the experiment was limited to <15 min post RBC addition to avoid significant RBC hemolysis, which would preclude assessment of RBC-dependent effects on NO- or nitrite dependent vasodilation. At the end of each experiment, the concentration of cell-free and RBC heme in the vessel bioassay chamber was measured, and data were normalized to RBC heme concentrations.

Heme concentration measurement

Heme was measured by deconvolution of visible spectra for oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, and methemoglobin as previously described (20).

Nitrite reductase activity

Hemoglobin solutions in PBS (25 μM, pH 7.4, containing 100 μM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid [DTPA]) were prepared from RBC lysates and then degassed by a gentle stream of nitrogen gas in sealed quartz cuvettes to reach different oxygen fractional saturations (ranging from 0% to 80%). A solution of deoxygenated sodium nitrite (3 mM final concentration) was added using an air-tight Hamilton syringe, and the absorbance spectrum (450–700 nm) was measured as a function of time at 37°C. DeoxyHb concentrations were calculated by spectral deconvolution as previously described (5, 51) and plotted as a function of time. The initial reaction velocity, initial deoxyhemoglobin, and nitrite concentrations were used to calculate the biomolecular rate constant. NO formation from nitrite reduction by hemolysates under anoxic conditions was determined using ozone-based chemiluminesence. Hemolysates from young or old RBC were prepared by lysing RBCs with water (1:4 vol:vol) and then diluting to a final heme concentration of 20 μM with PBS, pH 7.4. 10 ml of hemolysate was placed into the reaction chamber perfused with helium and under vacuum. SE25 antifoam (10 μl) was added and after 2–3 min equilibration, 20 μl of 250 mM nitrite solution was (final nitrite concentration 500 μM) added. NO produced was measured, and its concentration was determined by comparison to a standard curve generated using the NO-donor proliNonoate.

Nitrite oxidation by oxyHb

RBC were lysed in deionized water at a ratio of 1:5 and then diluted to 25 μM heme in PBS, pH 7.4+100 μM DTPA, 37°C. Sodium nitrite (500 μM final) was added, time-dependent changes in the visible spectrum (450–700 nm) were measured, and formation of metHb was determined by spectral deconvolution using oxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin standards. The lag phase, rate in the lag phase, and rate during propagation phase was determined as previously indicated (39).

Microparticle measurement

RBCs fractions (50% Hct) were incubated for 2 h at 20°C, in PBS with 0.1% BSA. The RBCs were then incubated with anti-glycophorin A-FITC-conjugated antibody (0.17 μg/ml) for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Samples were then analyzed by flow cytometry using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and events were acquired using CellQuest software. A total of 100,000 events were collected per measurement, and the data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR) as previously described (51).

Statistical analysis

One-way RM-ANOVA, two-way RM-ANOVA, and Student's t-test were used as indicated. p-Values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were done using GraphPad Prism Software (San Diego, CA).

Abbreviations Used

- BHT

butylated hydroxytoluene

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DTPA

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- Hct

hematocrit

- KH

Krebs-Henseleit

- L-NMMA

N-monomethyl-l-arginine

- NO

nitric oxide

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- RBC

red blood cells

- RDW

red cell distribution width

- RF

recombined after fractionation

- RM-ANOVA

repeated measures-analysis of variance

- SEM

standard error of the means

- SNA

Sambucus nigra lectin

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- SpNO

spermine NONOate

- UF

unfractionated

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL095468 to RPP). R.S. is supported by an NIH T32 HL007918 research training grant.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests or conflicts of interest related to this work exist for any author.

References

- 1.Abraham EC. Taylor JF. Lang CA. Influence of mouse age and erythrocyte age on glutathione metabolism. Biochem J. 1978;174:819–825. doi: 10.1042/bj1740819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azarov I. Huang KT. Basu S. Gladwin MT. Hogg N. Kim-Shapiro DB. Nitric oxide scavenging by red blood cells as a function of hematocrit and oxygenation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39024–39032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azarov I. Liu C. Reynolds H. Tsekouras Z. Lee JS. Gladwin MT. Kim-Shapiro DB. Mechanisms of slower nitric oxide uptake by red blood cells and other hemoglobin-containing vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:33567–33579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.228650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calvert JW. Lefer DJ. Clinical translation of nitrite therapy for cardiovascular diseases. Nitric Oxide. 2010;22:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantu-Medellin N. Vitturi DA. Rodriguez C. Murphy S. Dorman S. Shiva S. Zhou Y. Jia Y. Palmer AF. Patel RP. Effects of T- and R-state stabilization on deoxyhemoglobin-nitrite reactions and stimulation of nitric oxide signaling. Nitric Oxide. 2011;25:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castiglione N. Rinaldo S. Giardina G. Stelitano V. Cutruzzola F. Nitrite and nitrite reductases: from molecular mechanisms to significance in human health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:684–716. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho CS. Lee S. Lee GT. Woo HA. Choi EJ. Rhee SG. Irreversible inactivation of glutathione peroxidase 1 and reversible inactivation of peroxiredoxin II by H2O2 in red blood cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1235–1246. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen NS. Ekholm JE. Luthra MG. Hanahan DJ. Biochemical characterization of density-separated human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;419:229–242. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(76)90349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crawford JH. Isbell TS. Huang Z. Shiva S. Chacko BK. Schechter AN. Darley-Usmar VM. Kerby JD. Lang JD., Jr. Kraus D. Ho C. Gladwin MT. Patel RP. Hypoxia, red blood cells, and nitrite regulate NO-dependent hypoxic vasodilation. Blood. 2006;107:566–574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doherty DH. Doyle MP. Curry SR. Vali RJ. Fattor TJ. Olson JS. Lemon DD. Rate of reaction with nitric oxide determines the hypertensive effect of cell-free hemoglobin. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:672–676. doi: 10.1038/nbt0798-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donadee C. Raat NJ. Kanias T. Tejero J. Lee JS. Kelley EE. Zhao X. Liu C. Reynolds H. Azarov I. Frizzell S. Meyer EM. Donnenberg AD. Qu L. Triulzi D. Kim-Shapiro DB. Gladwin MT. Nitric oxide scavenging by red blood cell microparticles and cell-free hemoglobin as a mechanism for the red cell storage lesion. Circulation. 2011;124:465–476. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.008698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feelisch M. Rassaf T. Mnaimneh S. Singh N. Bryan NS. Jourd'Heuil D. Kelm M. Concomitant S-, N-, and heme-nitros(yl)ation in biological tissues and fluids: implications for the fate of NO in vivo. FASEB J. 2002;16:1775–1785. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0363com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felker GM. Allen LA. Pocock SJ. Shaw LK. McMurray JJ. Pfeffer MA. Swedberg K. Wang D. Yusuf S. Michelson EL. Granger CB. Red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic marker in heart failure: data from the CHARM Program and the Duke Databank. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forstermann U. Sessa WC. Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:829–837. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr304. 837a–837d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gifford SC. Derganc J. Shevkoplyas SS. Yoshida T. Bitensky MW. A detailed study of time-dependent changes in human red blood cells: from reticulocyte maturation to erythrocyte senescence. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:395–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gladwin MT. Raat NJ. Shiva S. Dezfulian C. Hogg N. Kim-Shapiro DB. Patel RP. Nitrite as a vascular endocrine nitric oxide reservoir that contributes to hypoxic signaling, cytoprotection, and vasodilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2026–H2035. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00407.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadengue AL. Del-Pino M. Simon A. Levenson J. Erythrocyte disaggregation shear stress, sialic acid, and cell aging in humans. Hypertension. 1998;32:324–330. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang KT. Keszler A. Patel N. Patel RP. Gladwin MT. Kim-Shapiro DB. Hogg N. The reaction between nitrite and deoxyhemoglobin. Reassessment of reaction kinetics and stoichiometry. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31126–31131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang YX. Wu ZJ. Mehrishi J. Huang BT. Chen XY. Zheng XJ. Liu WJ. Luo M. Human red blood cell aging: correlative changes in surface charge and cell properties. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:2634–2642. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Z. Shiva S. Kim-Shapiro DB. Patel RP. Ringwood LA. Irby CE. Huang KT. Ho C. Hogg N. Schechter AN. Gladwin MT. Enzymatic function of hemoglobin as a nitrite reductase that produces NO under allosteric control. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2099–2107. doi: 10.1172/JCI24650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imanishi H. Nakai T. Abe T. Takino T. Glutathione metabolism in red cell aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 1985;32:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(85)90035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imanishi H. Nakai T. Abe T. Takino T. Glutathione-linked enzyme activities in red cell aging. Clin Chim Acta. 1986;159:73–76. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(86)90168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isbell TS. Gladwin MT. Patel RP. Hemoglobin oxygen fractional saturation regulates nitrite-dependent vasodilation of aortic ring bioassays. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2565–H2572. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00759.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joshi MS. Ferguson TB., Jr. Han TH. Hyduke DR. Liao JC. Rassaf T. Bryan N. Feelisch M. Lancaster JR., Jr. Nitric oxide is consumed, rather than conserved, by reaction with oxyhemoglobin under physiological conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10341–10346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152149699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keszler A. Piknova B. Schechter AN. Hogg N. The reaction between nitrite and oxyhemoglobin: a mechanistic study. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9615–9622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705630200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kevil CG. Kolluru GK. Pattillo CB. Giordano T. Inorganic nitrite therapy: historical perspective and future directions. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:576–593. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim-Shapiro DB. Lee J. Gladwin MT. Storage lesion: role of red blood cell breakdown. Transfusion. 2011;51:844–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinbongard P. Schulz R. Rassaf T. Lauer T. Dejam A. Jax T. Kumara I. Gharini P. Kabanova S. Ozuyaman B. Schnurch HG. Godecke A. Weber AA. Robenek M. Robenek H. Bloch W. Rosen P. Kelm M. Red blood cells express a functional endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Blood. 2006;107:2943–2951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kosaka H. Tyuma I. Imaizumi K. Mechanism of autocatalytic oxidation of oxyhemoglobin by nitrite. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1983;42:S144–S148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X. Miller MJ. Joshi MS. Sadowska-Krowicka H. Clark DA. Lancaster JR., Jr. Diffusion-limited reaction of free nitric oxide with erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18709–18713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X. Samouilov A. Lancaster JR., Jr. Zweier JL. Nitric oxide uptake by erythrocytes is primarily limited by extracellular diffusion not membrane resistance. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26194–26199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundberg JO. Gladwin MT. Ahluwalia A. Benjamin N. Bryan NS. Butler A. Cabrales P. Fago A. Feelisch M. Ford PC. Freeman BA. Frenneaux M. Friedman J. Kelm M. Kevil CG. Kim-Shapiro DB. Kozlov AV. Lancaster JR., Jr. Lefer DJ. McColl K. McCurry K. Patel RP. Petersson J. Rassaf T. Reutov VP. Richter-Addo GB. Schechter A. Shiva S. Tsuchiya K. van Faassen EE. Webb AJ. Zuckerbraun BS. Zweier JL. Weitzberg E. Nitrate and nitrite in biology, nutrition and therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:865–869. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundberg JO. Weitzberg E. Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:156–167. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lurie S. Mamet Y. Red blood cell survival and kinetics during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;93:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.May JM. Qu ZC. Xia L. Cobb CE. Nitrite uptake and metabolism and oxidant stress in human erythrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1946–C1954. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.6.C1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owusu BY. Stapley R. Patel R. Nitric Oxide formation versus scavenging: the red blood cell balancing act. J Physiol. 2012;590:4993–5000. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.234906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel KV. Semba RD. Ferrucci L. Newman AB. Fried LP. Wallace RB. Bandinelli S. Phillips CS. Yu B. Connelly S. Shlipak MG. Chaves PH. Launer LJ. Ershler WB. Harris TB. Longo DL. Guralnik JM. Red cell distribution width and mortality in older adults: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:258–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel RP. Hogg N. Kim-Shapiro DB. The potential role of the red blood cell in nitrite-dependent regulation of blood flow. Cardiovasc Res\ 2011;89:507–515. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piknova B. Keszler A. Hogg N. Schechter AN. The reaction of cell-free oxyhemoglobin with nitrite under physiologically relevant conditions: implications for nitrite-based therapies. Nitric Oxide. 2009;20:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinkofsky HB. The effect of donor age on human erythrocyte density distribution. Mech Ageing Dev. 1997;97:73–79. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(97)01885-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roche CJ. Dantsker D. Samuni U. Friedman JM. Nitrite reductase activity of sol-gel-encapsulated deoxyhemoglobin. Influence of quaternary and tertiary structure. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36874–36882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakai H. Sato A. Masuda K. Takeoka S. Tsuchida E. Encapsulation of concentrated hemoglobin solution in phospholipid vesicles retards the reaction with NO, but not CO, by intracellular diffusion barrier. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1508–1517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salazar Vazquez BY. Cabrales P. Tsai AG. Intaglietta M. Nonlinear cardiovascular regulation consequent to changes in blood viscosity. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2011;49:29–36. doi: 10.3233/CH-2011-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samaja M. Rovida E. Motterlini R. Tarantola M. The relationship between the blood oxygen transport and the human red cell aging process. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;307:115–123. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5985-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt W. Boning D. Braumann KM. Red cell age effects on metabolism and oxygen affinity in humans. Respir Physiol. 1987;68:215–225. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(87)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shinozuka T. Changes in human red blood cells during aging in vivo. Keio J Med. 1994;43:155–163. doi: 10.2302/kjm.43.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singel DJ. Stamler JS. Chemical physiology of blood flow regulation by red blood cells: the role of nitric oxide and S-nitrosohemoglobin. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:99–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.060603.090918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spagnuolo C. Rinelli P. Coletta M. Chiancone E. Ascoli F. Oxidation reaction of human oxyhemoglobin with nitrite: a reexamination. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;911:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(87)90270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sparrow RL. Healey G. Patton KA. Veale MF. Red blood cell age determines the impact of storage and leukocyte burden on cell adhesion molecules, glycophorin A and the release of annexin V. Transfus Apher Sci. 2006;34:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sprague RS. Ellsworth ML. Erythrocyte-derived ATP and perfusion distribution: role of intracellular and intercellular communication. Microcirculation. 2012;19:430–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2011.00158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stapley R. Owusu BY. Brandon A. Cusick M. Rodriguez C. Marques MB. Kerby JD. Barnum SR. Weinberg JA. Lancaster JR., Jr. Patel RP. Erythrocyte storage increases rates of NO- and nitrite scavenging: implications for transfusion related toxicity. Biochem J. 2012;446:499–508. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Subasinghe W. Spence DM. Simultaneous determination of cell aging and ATP release from erythrocytes and its implications in type 2 diabetes. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;618:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tonelli M. Sacks F. Arnold M. Moye L. Davis B. Pfeffer M. Relation between red blood cell distribution width and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation. 2008;117:163–168. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.727545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tyan ML. Age-related increase in erythrocyte oxidant sensitivity. Mech Ageing Dev. 1982;20:25–32. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(82)90071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Faassen EE. Bahrami S. Feelisch M. Hogg N. Kelm M. Kim-Shapiro DB. Kozlov AV. Li H. Lundberg JO. Mason R. Nohl H. Rassaf T. Samouilov A. Slama-Schwok A. Shiva S. Vanin AF. Weitzberg E. Zweier J. Gladwin MT. Nitrite as regulator of hypoxic signaling in mammalian physiology. Med Res Rev. 2009;29:683–741. doi: 10.1002/med.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaughn MW. Huang KT. Kuo L. Liao JC. Erythrocyte consumption of nitric oxide: competition experiment and model analysis. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:18–31. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vitturi DA. Patel RP. Current perspectives and challenges in understanding the role of nitrite as an integral player in nitric oxide biology and therapy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waugh RE. Narla M. Jackson CW. Mueller TJ. Suzuki T. Dale GL. Rheologic properties of senescent erythrocytes: loss of surface area and volume with red blood cell age. Blood. 1992;79:1351–1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weinberg JA. Barnum SR. Patel RP. Red blood cell age and potentiation of transfusion-related pathology in trauma patients. Transfusion. 2011;51:867–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zerez CR. Lachant NA. Tanaka KR. Impaired erythrocyte methemoglobin reduction in sickle cell disease: dependence of methemoglobin reduction on reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide content. Blood. 1990;76:1008–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]