Abstract

The first line of defense protecting rhesus macaques from HIV-1 is the restriction factor rhTRIM5α, which recognizes the capsid core of the virus early after entry and normally blocks infection prior to reverse transcription. Cytoplasmic bodies containing rhTRIM5α have been implicated in the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, but the specific roles these structures play remain uncharacterized. Here, we examine the ubiquitination status of cytoplasmic body proteins. Using antibodies specific for different forms of ubiquitin, we show that ubiquitinated proteins are present in cytoplasmic bodies, and that this localization is altered after proteasome inhibition. A decrease in polyubiquitinated proteins localizing to cytoplasmic bodies was apparent after 1 h of proteasome inhibition, and greater differences were seen after extended proteasome inhibition. The decrease in polyubiquitin conjugates within cytoplasmic bodies was also observed when deubiquitinating enzymes were inhibited, suggesting that the removal of ubiquitin moieties from polyubiquitinated cytoplasmic body proteins after extended proteasome inhibition is not responsible for this phenomenon. Superresolution structured illumination microscopy revealed finer details of rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies and the polyubiquitin conjugates that localize to these structures. Finally, linkage-specific polyubiquitin antibodies revealed that K48-linked ubiquitin chains localize to rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies, implicating these structures in proteasomal degradation. Differential staining of cytoplasmic bodies seen with different polyubiquitin antibodies suggests that structural changes occur during proteasome inhibition that alter epitope availability. Taken together, it is likely that rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies are involved in recruiting components of the ubiquitin–proteasome system to coordinate proteasomal destruction of a viral or cellular protein(s) during restriction of HIV-1.

Introduction

The first line of defense in preventing HIV-1 from infecting rhesus macaques is the restriction factor TRIM5α. TRIM5α proteins are found in a variety of species and individual variants exhibit activity against a wide array of different viruses,1 with specificity encoded by the C-terminal SPRY domain.2–4 This SPRY domain interacts with the capsid core of the virus, and in the case of the rhesus macaque variant of TRIM5α (rhTRIM5α), interaction with the capsid core of HIV-1 normally leads to a block in infectivity prior to the completion of reverse transcription.5–7

Members of the TRIM family of proteins have been shown to self-associate through coiled-coiled domains into higher-order oligomers,8–10 and many members of this family accumulate in discrete subcellular structures.11 Studies examining the subcellular localization of rhTRIM5α revealed that this protein localizes in two cytoplasmic populations, but these populations are dynamic and are capable of exchanging protein.12 There is a pool of rhTRIM5α localized diffusely throughout the cytoplasm, and this pool is capable of exchanging protein with the population of rhTRIM5α that accumulates in puncta throughout the cytoplasm known as cytoplasmic bodies. In addition to rhTRIM5α, heat shock proteins13 and sequestosome-1/p6214 have been identified as localizing to cytoplasmic bodies, although these structures likely contain a number of other proteins of which we are not yet aware. Like the well-characterized accumulations of proteins in the nucleus associated with another TRIM family protein called PML,15,16 cytoplasmic bodies containing rhTRIM5α could also serve as a depot for the recruitment and release of proteins to coordinate the response to cellular stresses such as viral infection.

While the relevance of cytoplasmic body localization to restriction has been debated,17,18 imaging studies have revealed interesting connections to the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Cytoplasmic bodies have been observed to increase in size after inhibiting the activity of the proteasome pharmacologically with drugs such as MG132.19 Inhibiting the proteasome during infection also reveals an intermediate stage of restriction, in which reverse transcription is able to be completed, but the preintegration complex is defective for nuclear entry and is unable to infect the cell.20

In this intermediate stage of restriction virions can be observed to be sequestered within cytoplasmic bodies, and live cell imaging of cells expressing fluorescently tagged rhTRIM5α and infected with fluorescently labeled virus has revealed that these two components associate with and traffic with each other in the cytoplasm after infection.18 Additionally, these structures have been shown to contain ubiquitin18 and proteasomes.21,22

Biochemical studies examining ubiquitination have revealed more information regarding the interplay between restriction and the ubiquitin–proteasome system. The process of ubiquitination utilizes a cascade of enzymes to orchestrate the conjugation of ubiquitin to a target protein. The final enzyme in this process is the E3 ligase, which provides the specificity in determining which substrate will become ubiquitinated. The N-terminal RING domain of rhTRIM5α has been shown to act as an E3 ligase toward itself both in vitro23 and in vivo.24 However, although it is clear that rhTRIM5α is able to act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, this does not appear to be essential to its function as a restriction factor. rhTRIM5α proteins containing mutations in the RING domain predicted to interrupt E3 ligase activity, or even a deletion of the entire RING domain, exhibit an impaired ability to restrict infection, but these mutations do not completely eliminate restriction.24,25

In addition to playing a role in coordinating ubiquitin conjugation, rhTRIM5α is likely self-ubiquitinated. The attachment of a single ubiquitin moiety to a target protein (monoubiquitination) can have consequences such as influencing protein trafficking or DNA repair,26 while the attachment of chains of multiple ubiquitin moieties to a target protein (polyubiquitination) acts as a tag for proteasomal degradation.27,28 rhTRIM5α has been shown to be polyubiquitinated by western blot, and higher levels of polyubiquitinated forms of rhTRIM5α were detected after proteasome inhibition.13 More relevant to infection is that rhTRIM5α itself undergoes accelerated proteasomal degradation in the presence of restricted virus,29 revealing that ubiquitination of rhTRIM5α seems to have a functional consequence related to restriction.

Taken together, previous studies suggest that ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of a cytoplasmic body component, whether cellular or viral, might take place within these structures. While it is clear that the ubiquitin–proteasome system has many ties to rhTRIM5α restriction of HIV-1, there are still several important questions remaining. Although ubiquitin has previously been visualized in rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies, whether this ubiquitin is conjugated to cytoplasmic body proteins was not examined. The present study aimed to visualize the ubiquitination status of the population of rhTRIM5α that localizes to cytoplasmic bodies as well as other proteins that accumulate in these structures, to gain a better understanding of cytoplasmic body function and whether the ubiquitin present in these structures has consequences relevant to proteasomal degradation.

Materials and Methods

Cells and pharmaceuticals

HeLa cells stably expressing HA-tagged rhTRIM5α were a kind gift of Joseph Sodroski.5 These cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (HyClone) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 292 μg/ml l-glutamine (Gibco). Cells were treated with 1 μg/ml MG132 (Sigma-Aldrich) to inhibit the proteasome, or with ethanol (EtOH) as a vehicle control. In experiments using a deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitor, cells were treated with either 20 μM Δ12-PGJ230,31 (Cayman Chemical) or 20 μM PR-61932,33 (LifeSensors) together with either MG132 or EtOH. After appropriate drug treatments, cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde (Polysciences) in PIPES buffer for 5 min.

Antibodies

After fixation, cells were stained with rabbit-anti-HA (Sigma-Aldrich, used at a 1:300 dilution) together with one of the following monoclonal ubiquitin antibodies for 60 min: P4D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, used at a 1:100 dilution) recognizes both free and conjugated ubiquitin; FK2 (Enzo, used at a 1:15,000 dilution) recognizes both mono- and polyubiquitin conjugates; or FK1 (Enzo, used at a 1:500 dilution) recognizes only polyubiquitin-conjugated proteins. In separate experiments, cells were stained with FITC-conjugated rat-anti-HA (Roche, clone 3F10, used at a 1:125 dilution) together with two linkage-specific polyubiquitin antibodies: rabbit-anti-K48-Ub recognizes K48-linked polyubiquitin (Millipore, clone Apu2, used at a 1:100 dilution) and mouse-anti-K63-Ub recognizes K63-linked polyubiquitin (Enzo, clone HWA4C4, used at a 1:100 dilution). After incubation with primary antibodies, cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained sequentially with fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch or Invitrogen, used at dilutions determined separately for each stock) for 15 min. Cells were rinsed with PBS prior to mounting coverslips onto slides with FluoroGel (Electron Microscopy Sciences).

Microscopy

Images were acquired with a DeltaVision deconvolution microscope, then deconvolved and chromatically corrected for Z-shift using softWoRx software (Applied Precision) prior to analysis. Superresolution structured illumination images were acquired with a DeltaVision Optical Microscope, eXperimental (OMX), and then reconstructed using softWoRx software prior to analysis. For all experiments, all conditions were imaged at the same time using identical microscope and camera settings. For each figure, all images are shown with intensities displayed identically to facilitate comparison, with the exception of Fig. 3 in which panels A and B are from the same experiment shown in Fig. 2, while panels D and E are from a separate experiment.

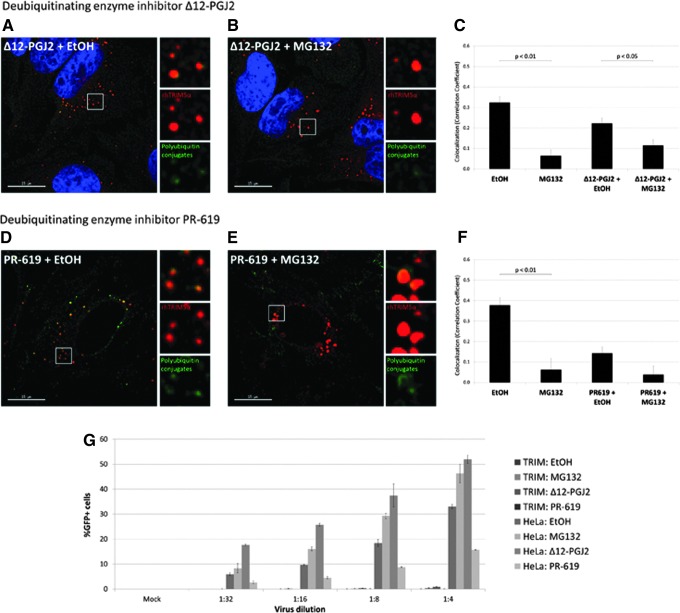

FIG. 3.

Deubiquitinating enzymes may act on cytoplasmic body proteins during proteasome inhibition. (A) Compared to treatment with deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitor Δ12-PGJ2 and EtOH, (B) there is still a reduction in colocalization after treatment with Δ12-PGJ2 and MG132. (C) The amount of conjugated polyubiquitin detected with the FK1 antibody within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies was quantified by measuring the Pearson correlation coefficient. Three experiments were performed, and data shown are from a representative experiment. Error bars represent the standard error within an experiment (N=25 images per condition). Significance was assessed by first transforming correlation coefficients with Fisher's transformation and then using a paired Student's t-test to compare EtOH to MG132 and to compare Δ12-PGJ2+EtOH to Δ12-PGJ2+MG132. (D) Similar results were obtained in experiments using deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitor PR-619 and EtOH compared to (E) PR-619 and MG132. (F) The amount of conjugated polyubiquitin detected with the FK1 antibody within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies was quantified by measuring the Pearson correlation coefficient. Three experiments were performed, and data shown are from a representative experiment. Error bars represent the standard error within an experiment (N=10 images per condition). Significance was assessed by first transforming correlation coefficients with Fisher's transformation and then using a paired Student's t-test to compare EtOH to MG132 and to compare PR-619+EtOH to PR-619+MG132. (G) Cells were pretreated with the indicated drug for 3 h prior to infection and drug was present in diluted virus for 3 h after being added to cells. Three experiments were performed, and data shown are from a representative experiment. Error bars represent the standard deviation between duplicate wells.

FIG. 2.

Time course of polyubiquitinated protein relocalization after proteasome inhibition. (A) Compared to vehicle control treatment (EtOH, left), there is a slight reduction in FK1-positive polyubiquitin conjugates localizing to rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies after 1 h of proteasome inhibition (MG132, right). (B) Compared to vehicle control treatment (EtOH, left), there is a reduction of FK1-positive polyubiquitin conjugates localizing to rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies after 3 h of proteasome inhibition (MG132, right). (C) The amount of conjugated polyubiquitin detected with the FK1 antibody within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies was quantified by measuring the Pearson correlation coefficient. Three experiments were performed, and data shown are from a representative experiment. Error bars represent the standard error within an experiment (N=25 images per condition). Significance was assessed by first transforming correlation coefficients with Fisher's transformation and then using a paired Student's t-test to compare EtOH to MG132 for each time point.

Image analysis

Colocalization was assessed by measuring the Pearson correlation coefficient using softWoRx software. Thresholds were selected to discriminate rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies from the diffuse population, and the same threshold was used for all conditions within an experiment. Optimal thresholds for each ubiquitin antibody were determined separately, and the same threshold was used for all conditions within an experiment. For statistical analysis, correlation coefficients were transformed using Fisher transformations to allow the use of Student's t-test, which requires normally distributed data. After transforming the correlation coefficient measured for each image, paired Student's t-tests were performed using these transformed values to compare cells treated with two different drugs. The transformed values were used only for statistical analysis, and the values displayed in figures are the raw correlation coefficients.

Infectivity experiments

VSV-G pseudotyped GFP reporter virus was produced by transfecting 293T cells with R7ΔenvGFP and CMV VSV-G plasmids using polyethylenimine (PEI, Polysciences). Virus was harvested approximately 48 h posttransfection, purified through 0.45-μm filters (Millipore), and stored at −80°C before use. Cells were infected in a 96-well format in duplicate and harvested for flow cytometry analysis approximately 48 h postinfection. Fixed samples were analyzed for GFP expression using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Western blots

Cells were treated with indicated drugs for 6 h before cell pellets were harvested and resuspended in Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) containing 2-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad) and heated at 95°C for 5 min. Samples were loaded onto 12% polyacrylamide Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast gels (Bio-Rad) and then transferred onto Odyssey Nitrocellulose Membranes (LI-COR). After blocking in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR) diluted 1:1 in PBS, membranes were probed using the following combinations of primary antibodies: P4D1 and rabbit-anti-HA; FK2 and rabbit-anti-HA; FK1 and rabbit-anti-HA; or rabbit-anti-K48-Ub and rat-anti-HA. Secondary antibodies (LI-COR) were used at a 1:5,000 dilution. Membranes were scanned on an Odyssey imager (LI-COR).

Results

Polyubiquitination is dynamic in rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies

Ubiquitin exists in several forms, each with distinct roles in the cell. Discriminating between free and conjugated ubiquitin, and more specifically examining the localization of the polyubiquitin conjugated to proteins that targets them for proteasomal destruction, should provide more information on the role that ubiquitin plays within cytoplasmic bodies.

To determine whether the ubiquitin previously observed to localize to rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies might be capable of targeting rhTRIM5α or another protein localized to cytoplasmic bodies for proteasomal degradation, we used antibodies specific for different forms of ubiquitin. First, an antibody that recognizes all forms of ubiquitin whether free or conjugated (P4D1) confirmed previous studies18 that ubiquitin is concentrated within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies, and this localization is especially apparent after 6 h of proteasome inhibition (Fig. 1A).

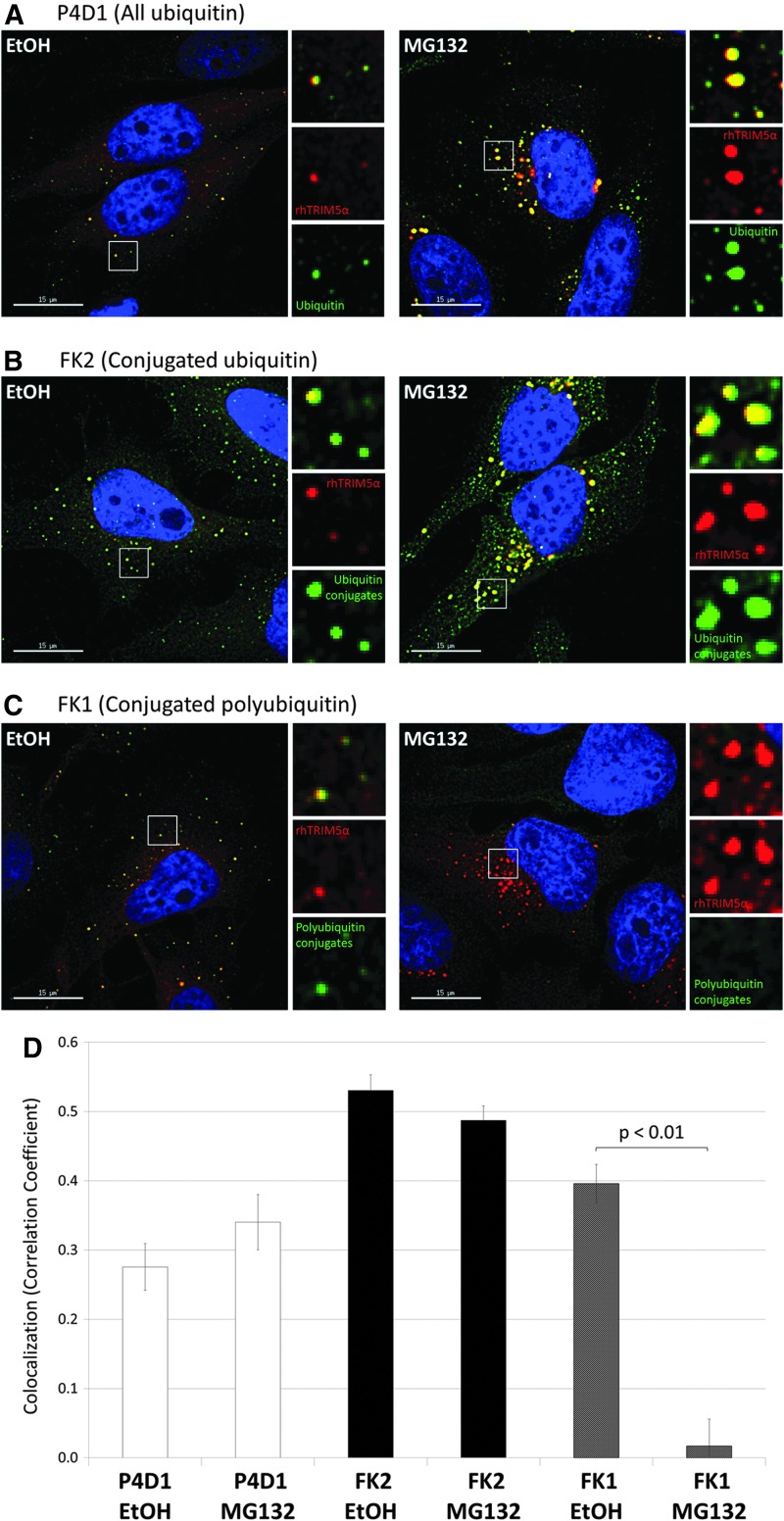

FIG. 1.

Polyubiquitination is dynamic in rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies. (A) The P4D1 antibody detects all ubiquitin, whether free or conjugated. P4D1 staining shows that cytoplasmic bodies containing HA-tagged rhTRIM5α also contain ubiquitin with vehicle control treatment (EtOH, left), or after 6 h of proteasome inhibition (MG132, right). (B) The FK2 antibody detects only conjugated ubiquitin, whether present as monoubiquitin or polyubiquitin conjugates. FK2 staining shows that cytoplasmic bodies containing HA-tagged rhTRIM5α also contain ubiquitin conjugates with vehicle control treatment (EtOH, left), or after 6 h of proteasome inhibition (MG132, right). (C) The FK1 antibody detects only conjugated polyubiquitin. FK1 staining shows that cytoplasmic bodies containing HA-tagged rhTRIM5α also contain polyubiquitinated proteins with vehicle control treatment (EtOH, left), but 6 h of proteasome inhibition (MG132, right) eliminates this cytoplasmic body localization. (D) The amount of all ubiquitin (P4D1), conjugated ubiquitin (FK2), or conjugated polyubiquitin (FK1) within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies was quantified by measuring the Pearson correlation coefficient. Three experiments were performed, and data shown are from a representative experiment. Error bars represent the standard error within an experiment (N=25 images per condition). Significance was assessed by first transforming correlation coefficients with Fisher's transformation and then using a paired Student's t-test to compare EtOH to MG132 for each antibody.

Two additional antibodies were also used that are well-characterized in their ability to specifically recognize ubiquitin only when it is conjugated to a protein, but not in its free form.34 Both FK2 and FK1 antibodies recognize polyubiquitin conjugates, but the FK2 antibody also recognizes conjugated monoubiquitin. Staining with FK2 revealed a similar localization of ubiquitinated proteins to cytoplasmic bodies both with and without proteasome inhibition (Fig. 1B).

Finally, staining with the FK1 antibody revealed that polyubiquitin conjugates are concentrated within cytoplasmic bodies under normal conditions, but strikingly upon proteasome inhibition a dramatic relocalization was observed (Fig. 1C). After proteasome inhibition, the polyubiquitin conjugates detected with the FK1 antibody no longer accumulated in cytoplasmic bodies, and only a weak signal remained that was localized diffusely throughout the cell and was barely visible after normalizing display intensities.

Localization to cytoplasmic bodies was quantified by measuring colocalization as represented by the Pearson correlation coefficient. The colocalization of ubiquitin antibody staining and rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies shows that these patterns are consistent between individual cells (Fig. 1D). While colocalization does not change significantly for the ubiquitin detected by the P4D1 and FK2 antibodies, a significant decrease was observed for the polyubiquitin conjugates detected by the FK1 antibody after proteasome inhibition.

Time course of polyubiquitinated protein relocalization after proteasome inhibition

To further characterize the decrease in the epitope within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies detected by the FK1 antibody after proteasome inhibition, earlier time points of MG132 treatment were examined. These experiments revealed that the decrease in polyubiquitinated proteins localizing to rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies occurred gradually over time as proteasome function was inhibited, with a noticeable decrease after 3 h of proteasome inhibition (Fig. 2B) and only a slight decrease visible after 1 h (Fig. 2A). The greatest decrease in polyubiquitinated proteins within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies detected with the FK1 antibody was seen after 6 h of proteasome inhibition, and at earlier time points the difference between MG132 treatment and EtOH vehicle controls was less pronounced (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that over time, proteasome inhibition gradually reduces the amount or availability of the epitope recognized by FK1, revealing changes in the accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins within TRIM bodies.

These results reveal that polyubiquitination is dynamic in rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies, and several possibilities could explain the reduction in FK1 staining despite the continued presence of FK2-positive accumulations within cytoplasmic bodies. FK2 staining in the absence of FK1 staining is generally interpreted as monoubiquitination, so we initially suspected that the change in localization we observed with the FK1 antibody after proteasome inhibition might represent a shift from polyubiquitin to monoubiquitin conjugated to cytoplasmic body proteins.

Deubiquitinating enzymes acting on cytoplasmic body proteins during proteasome inhibition cannot fully explain the reduction in FK1 staining

The absence of polyubiquitinated proteins in cytoplasmic bodies during proteasome inhibition could be a result of deubiquitinating enzymes removing polyubiquitin attached to proteins sequestered at proteasomes within cytoplasmic bodies, in the absence of proteasome function. The proteasome itself contains associated deubiquitinating enzymes, so the shortening of polyubiquitin chains could potentially occur within cytoplasmic bodies without the need for any additional enzymes to be recruited. To test this possibility, we used pharmacological inhibitors of deubiquitinating enzymes to assess whether the accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins in cytoplasmic bodies could be rescued after MG132 treatment.

Cells were treated with deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitor Δ12-PGJ230,31 together with either MG132 or EtOH as a vehicle control, and stained with the FK1 antibody to detect polyubiquitinated proteins. We observed that in the presence of this deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitor, proteasome inhibition exerted a weaker effect on the relocalization of FK1-positive polyubiquitin conjugates (Fig. 3A–C). A 2-fold decrease in the correlation coefficient was seen after 6 h of proteasome inhibition in the presence of Δ12-PGJ2 (relative to 6 h of EtOH+Δ12-PGJ2 treatment), compared to the 5-fold decrease seen after 6 h of proteasome inhibition alone (relative to 6 h of EtOH treatment). We repeated these experiments with an additional pharmacological inhibitor of deubiquitinating enzymes, PR-619,32,33 and obtained similar results (Fig. 3D–F).

Despite the weaker effect that MG132 had on the relocalization of FK1-positive polyubiquitin conjugates in the presence of either Δ12-PGJ2 or PR-619, we cannot be certain that this observation is a result of the specific inhibition of deubiquitination, as we saw an overall reduction in staining with the FK1 antibody after treatment with either deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitor, whereas the opposite would be expected if polyubiquitinated proteins are stabilized. Deubiquitinating enzymes provide a number of critical functions throughout the cell, and inhibiting these enzymes often results in cytotoxicity,35,36 complicating the use of these compounds in studies of intact cells.

To ensure that rhTRIM5α is able to function in the presence of deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors, we measured restriction in an infectivity assay. The presence of either Δ12-PGJ2 or PR-619 during infection did not impair the ability of rhTRIM5α to restrict infection (Fig. 3G, “TRIM” bars). We also examined the effect of these deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors on infectivity in permissive HeLa cells that do not express rhTRIM5α (Fig. 3G, “HeLa” bars), and greater levels of infection were seen with Δ12-PGJ2 while the opposite was seen with PR-619.

Although the weaker effect of MG132 during deubiquitinating enzyme inhibition suggests that overactive deubiquitinating enzymes may play a role in cytoplasmic bodies during proteasome inhibition, other possibilities must be considered to fully explain the reduction in cytoplasmic body FK1 staining seen after proteasome inhibition.

Superresolution imaging of polyubiquitin conjugates in rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies

To gain further insight into the relocalization of polyubiquitin conjugates within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies after proteasome inhibition, we used superresolution structured illumination microscopy to examine these structures during two different time points of proteasome inhibition. Cells were treated with proteasome inhibitor MG132 or with EtOH as a vehicle control, and fixed after either 3 or 6 h. Staining was carried out as described above, and rhTRIM5α and the polyubiquitin conjugates detected with the FK1 antibody were visualized using the OMX superresolution microscope.

The resolution attainable with structured illumination microscopy confirms that FK1-positive polyubiquitinated proteins do indeed colocalize with cytoplasmic bodies under normal conditions, although it also revealed that rhTRIM5α and FK1-positive polyubiquitin conjugates also occupy distinct areas within cytoplasmic bodies. For example, a large accumulation of polyubiquitin conjugates detected with the FK1 antibody often contained several smaller puncta of rhTRIM5α after EtOH vehicle control treatment (Fig. 4A and C). The increased resolution also revealed structural details to the polyubiquitin conjugates after proteasome inhibition that we were unable to observe with standard diffraction-limited deconvolution microscopy. Interestingly, the superresolution images revealed that polyubiquitinated proteins appeared to localize primarily on the outside of the cytoplasmic bodies after 3 h (Fig. 4B) or 6 h (Fig. 4D) of proteasome inhibition. This observation could represent a true difference in localization of polyubiquitin conjugates, or alternatively, could reflect an inability of the FK1 antibody to detect epitopes buried within the higher order structure of cytoplasmic bodies. Quantification was performed in the same manner as with previous deconvolution images, and although there was no significant difference in colocalization after 3 h of proteasome inhibition we did observe a significant decrease after 6 h of proteasome inhibition compared to the vehicle control (Fig. 4E). The similar correlation coefficient measured after 3 h of MG132 may be due to the increased resolution of the superresolution microscope favoring the detection of punctate signals. On the diffraction-limited deconvolution microscope, when the signal for the FK1 antibody is decreased after proteasome inhibition this weaker signal is more diffuse, decreasing colocalization. In contrast, on the superresolution microscope the FK1 antibody staining is more punctate and the signal level is better maintained so the overlap does not change as dramatically. This difference in resolution between the two systems may allow the signal to maintain greater levels of overlap in this experiment compared to the diffraction-limited deconvolution microscopy we used in the rest of this article.

FIG. 4.

Superresolution imaging of polyubiquitin conjugates in rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies. (A) After 3 h of EtOH vehicle control treatment polyubiquitin conjugates detected with the FK1 antibody localize to cytoplasmic bodies containing several smaller clusters of rhTRIM5α. (B) Polyubiquitin conjugates detected with the FK1 antibody often localize toward the outside of larger rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies after 3 h of proteasome inhibition. (C) After 6 h of EtOH vehicle control treatment polyubiquitin conjugates detected with the FK1 antibody localize to cytoplasmic bodies containing several smaller clusters of rhTRIM5α. (D) Polyubiquitin conjugates detected with the FK1 antibody often localize toward the outside of larger rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies after 6 h of proteasome inhibition. (E) The amount of conjugated polyubiquitin detected with the FK1 antibody within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies was quantified by measuring the Pearson correlation coefficient. Three experiments were performed, and data shown are from a representative experiment. Error bars represent the standard error within an experiment (N=10 images per condition). Significance was assessed by first transforming correlation coefficients with Fisher's transformation and then using a paired Student's t-test to compare EtOH to MG132 for each time point. There was no difference in colocalization after 3 h of MG132 treatment, but a significant decrease was observed after 6 h of MG132 treatment.

Cytoplasmic bodies contain accumulations of K48-linked polyubiquitin chains

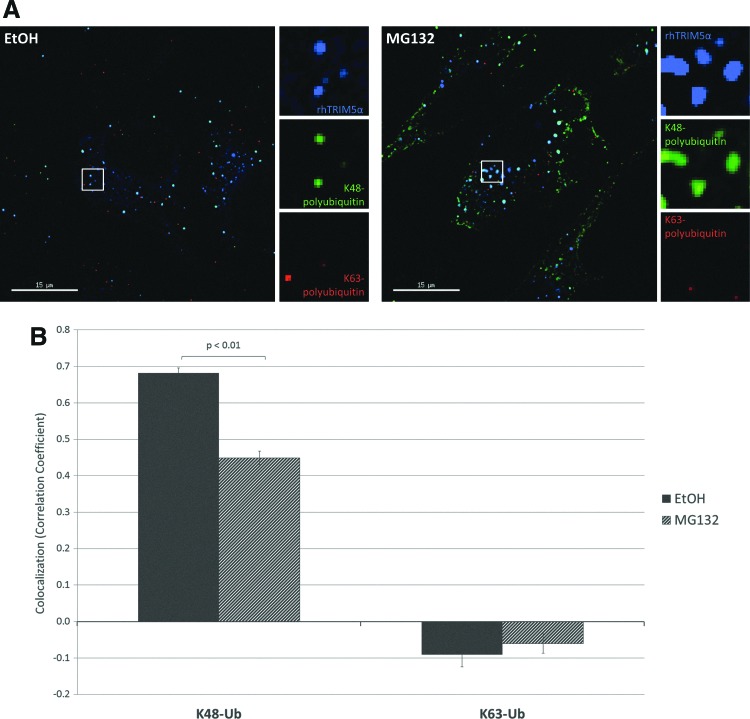

To determine whether the polyubiquitin localized to these puncta was marking cytoplasmic body proteins for proteasomal degradation, we used linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies. Proteins conjugated to polyubiquitin chains linked at the 48th lysine residue (K48) are generally bound for degradation by the proteasome,27,28 whereas conjugation to K63-linked polyubiquitin has other consequences such as regulation of protein function and cellular trafficking.37,38 Staining with a K48 linkage-specific antibody revealed an accumulation of K48-linked polyubiquitin conjugates present in rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies, whereas staining with a K63 linkage-specific antibody showed localization in smaller puncta distributed throughout the cell that did not overlap with rhTRIM5α (Fig. 5A, left). Measuring the Pearson correlation coefficient confirmed these findings, as high levels of colocalization with rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies were seen for K48-linked polyubiquitin, while the correlation for K63-linked polyubiquitin was close to zero (Fig. 5B). Thus, the polyubiquitin conjugates that we observe localized to rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies are likely destined for destruction by the proteasome.

FIG. 5.

Cytoplasmic bodies contain accumulations of K48-linked polyubiquitin chains. (A) Linkage-specific polyubiquitin antibodies reveal that K48-linked polyubiquitin localizes to rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies. Left: K48-linked polyubiquitin (green) localizes to rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies (blue), while K63-linked polyubiquitin (red) shows a different distribution throughout the cell. Right: Although K48-linked polyubiquitin can still be detected within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies after 6 h of proteasome inhibition, a population of this K48-linked polyubiquitin can also be seen to localize diffusely throughout the cell. (B) The amount of K48-linked and K63-linked polyubiquitin within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies was quantified by measuring the Pearson correlation coefficient. Three experiments were performed, and data shown are from a representative experiment. Error bars represent the standard error within an experiment (N=25 images per condition), and significance was assessed by first transforming correlation coefficients with Fisher's transformation and then using a paired Student's t-test to compare EtOH to MG132 for each antibody.

Treatment with MG132 led to the presence of a diffuse population of K48-linked polyubiquitin staining in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A, right), and this can be measured as a decrease in colocalization after 6 h of MG132 treatment (Fig. 5B). However, unlike the staining seen with the FK1 antibody there did not appear to be a noticeable loss in staining within cytoplasmic bodies.

The differences in staining seen with two antibodies capable of detecting polyubiquitin suggest that the reduction in FK1 staining may not represent a true loss of polyubiquitin conjugates within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies, but may instead result from changes in the availability of the epitope recognized by the monoclonal antibody FK1. The ubiquitin antibodies used in this study are thought to discriminate between different forms of ubiquitin based on conformational differences, so the decrease in staining with the FK1 antibody may represent a change in structure within cytoplasmic bodies that could render the epitope detected by the FK1 antibody unavailable while not affecting the ability of the K48 linkage-specific ubiquitin antibody to bind.

To verify that the reduction in FK1 staining we observed in cytoplasmic bodies after proteasome inhibition was not due to a reduction in the overall levels of polyubiquitin conjugates within the cell, we performed western blots using the same antibodies as in our imaging experiments. Ubiquitin antibodies P4D1, FK2, FK1, and K48-linked polyubiquitin all revealed accumulations of high-molecular-weight polyubiquitin conjugates after 6 h of proteasome inhibition, as expected (Fig. 6). Furthermore, both deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors are working properly, as demonstrated by the prominent high-molecular-weight staining after treatment with either Δ12-PGJ2 or PR-619. These results provide further evidence that structural differences affecting epitope availability within cytoplasmic bodies in an intact cell may explain our observations, rather than the true levels of ubiquitinated proteins.

FIG. 6.

Western blot analysis of antibodies and drug treatments used in imaging experiments. Cells were treated with indicated drugs for 6 h before preparing samples for SDS-PAGE. Denatured samples were loaded in quadruplicate and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed in parallel using either (A) P4D1 (all ubiquitin) and rabbit-anti-HA, (B) FK2 (conjugated ubiquitin) and rabbit-anti-HA, (C) FK1 (conjugated polyubiquitin) and rabbit-anti-HA, or (D) K48 linkage-specific polyubiquitin and rat-anti-HA antibodies. Samples were prepared in three independent experiments, and western blots were performed twice.

While FK2 staining in the absence of FK1 staining is usually interpreted as monoubiquitination, the results presented here suggest that detecting ubiquitination can be more complicated than is usually appreciated, and that a simple interpretation may not always be correct. In any case, it reveals dynamic changes in ubiquitin epitopes within cytoplasmic bodies as a consequence of proteasome inhibition.

Discussion

Cytoplasmic bodies containing restriction factor rhTRIM5α have been implicated in the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, but the specific role these structures may play with regard to this pathway remains uncharacterized. Here, we show that not only do these cytoplasmic bodies contain ubiquitin as previously observed (Fig. 1A), but that much of this ubiquitin is conjugated to proteins within these structures. Using an antibody reported to be specific to conjugated ubiquitin (FK2) revealed that accumulations of ubiquitinated proteins localize to cytoplasmic bodies both under normal conditions and when the function of the proteasome has been pharmacologically inhibited (Fig. 1B). The presence of ubiquitinated proteins in cytoplasmic bodies suggests either that ubiquitin conjugation occurs within these structures or that ubiquitinated cargo is delivered to them for degradation in the proteasomes concentrated in cytoplasmic bodies. The sequestration within cytoplasmic bodies of ubiquitin–proteasome components could be an important mechanism to ensure a quick response upon viral infection.

Although we observed a constitutive presence of ubiquitinated proteins inside of cytoplasmic bodies, the situation was quite different for polyubiquitinated proteins. We observed an accumulation of polyubiquitin conjugates within cytoplasmic bodies under normal conditions, as detected with the FK1 antibody previously reported to be specific to polyubiquitin conjugates. However, cytoplasmic body staining with the FK1 antibody after several hours of proteasome inhibition was dramatically reduced (Fig. 1C). When the proteasome was inhibited there was no longer a concentration of FK1 staining in cytoplasmic bodies, but only a weak signal remained that was localized diffusely throughout the cell.

We examined different time points of proteasome inhibition to assess the time course of this effect. This revealed that there is a gradual decrease in FK1-positive polyubiquitinated proteins within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies, evident after 1 h of proteasome inhibition but much stronger by 6 h of drug treatment (Fig. 2).

One possibility to explain this change in localization is that during proteasome inhibition, deubiquitinating enzymes remove polyubiquitin chains from the proteins that are stalled at proteasomes awaiting degradation. To address this idea, we used two compounds to pharmacologically inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes—Δ12-PGJ230,31 and PR-61932,33—to examine whether inhibiting such enzymes from removing ubiquitin from polyubiquitin chains could rescue the cytoplasmic body localization of polyubiquitin conjugates detected with the FK1 antibody. A caveat to this experiment is that deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors have been shown to have other effects in the cell and can be cytotoxic,35,36 and the overall reduction in FK1 staining after treatment with Δ12-PGJ2 or PR-619 suggests that such off-target effects may be occurring. For both compounds, we observed that proteasome inhibition had a weaker effect on relocalization in the presence of the deubiquitinating inhibitor (Fig. 3), supporting the hypothesis that deubiquitinating enzymes may play a role in the reduction of FK1 staining after proteasome inhibition. However, the use of these compounds did not completely rescue the reduction in FK1 staining within cytoplasmic bodies, suggesting that alternative mechanisms may be responsible for these observations.

We also used superresolution structured illumination microscopy to visualize structural details of polyubiquitin conjugates within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies. The increased resolution allowed us to observe that rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies were often composed of several smaller puncta that could not be resolved with standard diffraction-limited microscopy, and that the polyubiquitin conjugates detected with the FK1 antibody localize to these structures (Fig. 4A and C). We also observed that after proteasome inhibition, the signal from the FK1 antibody often localized at the perimeter of rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies while minimal staining was detected at the center of these bodies (Fig. 4B and D).

Staining with linkage-specific polyubiquitin antibodies revealed that K48-linked ubiquitin chains localize to cytoplasmic bodies (Fig. 5A, left). Polyubiquitin chains linked through the 48th lysine residue of ubiquitin are able to tag proteins for proteasomal degradation, so it is likely that rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies are involved in recruiting components of the ubiquitin–proteasome system to coordinate proteasomal destruction of either a viral or cellular protein during restriction of HIV-1.

The presence of K48-linked polyubiquitin in cytoplasmic bodies was also observed after proteasome inhibition (Fig. 5A, right), however, which contrasts with the dramatic loss of staining we observed with the FK1 antibody. This reveals that the reduction of staining in cytoplasmic bodies seen with the FK1 antibody cannot be explained entirely by the activity of deubiquitinating enzymes during proteasome inhibition. Both FK1 and FK2 are well-characterized antibodies thought to recognize specific forms of ubiquitin based on the differences in conformation between ubiquitin in its free form and when it is conjugated to a target protein either as a monoubiquitin or as a polyubiquitin chain. This implies that the structure of ubiquitin within chains is different than the structure of a single ubiquitin attached to a protein, and that these differences may correspond to differential epitope availability. Likewise, NMR studies suggest that there are structural differences between K48-linked and K63-linked polyubiquitin chains.39–42 The FK2 and FK1 antibodies are widely used, and most reports in the literature conclude that FK2 staining in the absence FK1 staining represents monoubiquitination. However, the results presented here make it clear that situations are not always so simple. Understanding more about the epitope recognized by the FK1 antibody would provide more insight into potential structural rearrangements that occur within rhTRIM5α cytoplasmic bodies during proteasome inhibition that may hide certain epitopes.

We also used these antibodies in western blot analyses to verify that polyubiquitin conjugates are still present within the cell after proteasome inhibition. In contrast with our observations from imaging experiments in intact cells, in the context of denatured cellular proteins the FK1 antibody was able to detect high-molecular-weight polyubiquitin conjugates. This further supports the possibility that the structure of cytoplasmic bodies may alter epitope availability after MG132 treatment.

Based on the differences in staining observed here using two different polyubiquitin antibodies along with the knowledge of conformational changes within ubiquitin that occur depending on whether or how it is linked to a substrate, it is likely that the reduction in staining with the FK1 antibody is a result of a structural difference in the ubiquitinated proteins present in cytoplasmic bodies during proteasome inhibition. Although the precise epitopes that these ubiquitin antibodies bind are unknown, it is possible that proteasome inhibition could induce a structural change in either rhTRIM5α itself or another protein that localizes to cytoplasmic bodies, which could prevent the FK1 antibody from binding while leaving the epitope recognized by the K48 linkage-specific antibody unaffected. Alternatively, if the ubiquitin chains attached to cytoplasmic body proteins have an altered conformation this could also affect the ability of conformation-specific ubiquitin antibodies to bind. Future experiments utilizing a wider array of ubiquitin antibodies should help to define what structural changes may take place in cytoplasmic bodies during proteasome inhibition, which will lead to a better understanding of how restriction takes place in the absence of proteasome function.

Like the well-characterized nuclear bodies known as ND10 associated with another TRIM family protein, PML,15 cytoplasmic bodies containing rhTRIM5α could potentially serve as a depot for the recruitment and release of cellular and viral proteins, in which the concentration of specific proteins in close proximity could facilitate the coordination of specific functions important in viral infection and other cellular stresses.16 Whether ubiquitination or degradation actually occurs within cytoplasmic bodies remains to be determined, but the presence of ubiquitin and K48-linked polyubiquitinated proteins within these structures and the changes seen during proteasome inhibition add to the growing evidence that they are dynamic organized structures involved in proteasomal degradation during restriction of HIV-1.

Acknowledgments

HeLa cells stably expressing HA-tagged rhTRIM5α were a kind gift of Joseph Sodroski.5 This research was supported by the Structural Biology Center for HIV/Host Interactions in Trafficking and Assembly NIH P50 GM082545, NIH training grant T32 AI060523, and NIH 5 RO1 AI047770.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Towers GJ. Control of viral infectivity by tripartite motif proteins. Human Gene Ther. 2005;16(10):1125–1132. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yap MW. Nisole S. Stoye JP. A single amino acid change in the SPRY domain of human Trim5alpha leads to HIV-1 restriction. Curr Biol. 2005;15(1):73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohkura S. Yap MW. Sheldon T. Stoye JP. All three variable regions of the TRIM5alpha B30.2 domain can contribute to the specificity of retrovirus restriction. J Virol. 2006;80(17):8554–8565. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00688-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stremlau M. Perron M. Welikala S. Sodroski J. Species-specific variation in the B30.2(SPRY) domain of TRIM5alpha determines the potency of human immunodeficiency virus restriction. J Virol. 2005;79(5):3139–3145. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.3139-3145.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stremlau M. Owens CM. Perron MJ. Kiessling M. Autissier P. Sodroski J. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature. 2004;427(6977):848–853. doi: 10.1038/nature02343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sebastian S. Luban J. TRIM5alpha selectively binds a restriction-sensitive retroviral capsid. Retrovirology. 2005;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stremlau M. Perron M. Lee M. Li Y. Song B. Javanbakht H. Diaz-Griffero F. Anderson DJ. Sundquist WI. Sodroski J. Specific recognition and accelerated uncoating of retroviral capsids by the TRIM5{alpha} restriction factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(14):5514–5519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509996103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mische CC. Javanbakht H. Song B. Diaz-Griffero F. Stremlau M. Strack B. Si Z. Sodroski J. Retroviral restriction factor TRIM5alpha is a trimer. J Virol. 2005;79(22):14446–14450. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14446-14450.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javanbakht H. Yuan W. Yeung DF. Song B. Diaz-Griffero F. Li Y. Li X. Stremlau M. Sodroski J. Characterization of TRIM5alpha trimerization and its contribution to human immunodeficiency virus capsid binding. Virology. 2006;353(1):234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langelier CR. Sandrin V. Eckert DM. Christensen DE. Chandrasekaran V. Alam SL. Aiken C. Olsen JC. Kar AK. Sodroski JG. Sundquist WI. Biochemical characterization of a recombinant TRIM5alpha protein that restricts human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol. 2008;82(23):11682–11694. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01562-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reymond A. Meroni G. Fantozzi A. Merla G. Cairo S. Luzi L. Riganelli D. Zanaria E. Messali S. Cainarca S. Guffanti A. Minucci S. Pelicci PG. Ballabio A. The tripartite motif family identifies cell compartments. EMBO J. 2001;20(9):2140–2151. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell EM. Dodding MP. Yap MW. Wu X. Gallois-Montbrun S. Malim MH. Stoye JP. Hope TJ. TRIM5 alpha cytoplasmic bodies are highly dynamic structures. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(6):2102–2111. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-12-1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz-Griffero F. Li X. Javanbakht H. Song B. Welikala S. Stremlau M. Sodroski J. Rapid turnover and polyubiquitylation of the retroviral restriction factor TRIM5. Virology. 2006;349(2):300–315. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connor C. Pertel T. Gray S. Robia SL. Bakowska JC. Luban J. Campbell EM. p62/Sequestosome1 associates with and sustains the expression of the retroviral restriction factor TRIM5{alpha} J Virol. 2010;84(12):5997–6006. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02412-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everett RD. Meredith M. Orr A. Cross A. Kathoria M. Parkinson J. A novel ubiquitin-specific protease is dynamically associated with the PML nuclear domain and binds to a herpesvirus regulatory protein. EMBO J. 1997;16(7):1519–1530. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Negorev D. Maul G.G. Cellular proteins localized at and interacting within ND10/PML nuclear bodies/PODs suggest functions of a nuclear depot.”. Oncogene. 2001;20(49):7234–7242. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song B. Diaz-Griffero F. Park DH. Rogers T. Stremlau M. Sodroski J. TRIM5alpha association with cytoplasmic bodies is not required for antiretroviral activity. Virology. 2005;343(2):201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell EM. Perez O. Anderson JL. Hope TJ. Visualization of a proteasome-independent intermediate during restriction of HIV-1 by rhesus TRIM5alpha. J Cell Biol. 2008;180(3):549–561. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu X. Anderson JL. Campbell EM. Joseph AM. Hope TJ. Proteasome inhibitors uncouple rhesus TRIM5alpha restriction of HIV-1 reverse transcription and infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(19):7465–7470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510483103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson JL. Campbell EM. Wu X. Vandegraaff N. Engelman A. Hope TJ. Proteasome inhibition reveals that a functional preintegration complex intermediate can be generated during restriction by diverse TRIM5 proteins. J Virol. 2006;80(19):9754–9760. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01052-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danielson CM. Cianci GC. Hope TJ. Recruitment and dynamics of proteasome association with rhTRIM5alpha cytoplasmic complexes during HIV-1 infection. Traffic. 2012;13(9):1206–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukic Z. Hausmann S. Sebastian S. Rucci J. Sastri J. Robia SL. Luban J. Campbell EM. TRIM5alpha associates with proteasomal subunits in cells while in complex with HIV-1 virions. Retrovirology. 2011;8:93. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamauchi K. Wada K. Tanji K. Tanaka M. Kamitani T. Ubiquitination of E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM5 alpha and its potential role. FEBS J. 2008;275(7):1540–1555. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lienlaf M. Hayashi F. Di Nunzio F. Tochio N. Kigawa T. Yokoyama S. Diaz-Griffero F. Contribution of E3-ubiquitin ligase activity to HIV-1 restriction by TRIM5alpha(rh): Structure of the RING domain of TRIM5alpha. J Virol. 2011;85(17):8725–8737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00497-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Javanbakht H. Diaz-Griffero F. Stremlau M. Si Z. Sodroski J. The contribution of RING and B-box 2 domains to retroviral restriction mediated by monkey TRIM5alpha. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(29):26933–26940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukhopadhyay D. Riezman H. Proteasome-independent functions of ubiquitin in endocytosis and signaling. Science. 2007;315(5809):201–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1127085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chau V. Tobias JW. Bachmair A. Marriott D. Ecker DJ. Gonda DK. Varshavsky A. A multiubiquitin chain is confined to specific lysine in a targeted short-lived protein. Science. 1989;243(4898):1576–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2538923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thrower JS. Hoffman L. Rechsteiner M. Pickart CM. Recognition of the polyubiquitin proteolytic signal. EMBO J. 2000;19(1):94–102. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rold C J. Aiken C. Proteasomal degradation of TRIM5alpha during retrovirus restriction. PLoS Path. 2008;4(5):e1000074. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mullally JE. Moos PJ. Edes K. Fitzpatrick FA. Cyclopentenone prostaglandins of the J series inhibit the ubiquitin isopeptidase activity of the proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(32):30366–30373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Z. Melandri F. Berdo I. Jansen M. Hunter L. Wright S. Valbrun D. Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Delta12-Prostaglandin J2 inhibits the ubiquitin hydrolase UCH-L1 and elicits ubiquitin-protein aggregation without proteasome inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319(4):1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian X. Isamiddinova NS. Peroutka RJ. Goldenberg SJ. Mattern MR. Nicholson B. Leach C. Characterization of selective ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like protease inhibitors using a fluorescence-based multiplex assay format. ASSAY Drug Dev Technol. 2011;9(2):165–173. doi: 10.1089/adt.2010.0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altun M. Kramer HB. Willems LI. McDermott JL. Leach CA. Goldenberg SJ. Kumar KG. Konietzny R. Fischer R. Kogan E. Mackeen MM. McGouran J. Khoronenkova SV. Parsons JL. Dianov GL. Nicholson B. Kessler BM. Activity-based chemical proteomics accelerates inhibitor development for deubiquitylating enzymes. Chem Biol. 2011;18(11):1401–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujimuro M. Sawada H. Yokosawa H. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific to multi-ubiquitin chains of polyubiquitinated proteins. FEBS Lett. 1994;349(2):173–180. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Y. Baker RT. Fischer-Vize JA. Control of cell fate by a deubiquitinating enzyme encoded by the fat facets gene. Science. 1995;270(5243):1828–1831. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindsey DF. Amerik A. Deery WJ. Bishop JD. Hochstrasser M. Gomer RH. A deubiquitinating enzyme that disassembles free polyubiquitin chains is required for development but not growth in Dictyostelium. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(44):29178–29187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.29178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spence J. Sadis S. Haas AL. Finley D. A ubiquitin mutant with specific defects in DNA repair and multiubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(3):1265–1273. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newton K. Matsumoto ML. Wertz IE. Kirkpatrick DS. Lill JR. Tan J. Dugger D. Gordon N. Sidhu SS. Fellouse FA. Komuves L. French DM. Ferrando RE. Lam C. Compaan D. Yu C. Bosanac I. Hymowitz SG. Kelley RF. Dixit VM. Ubiquitin chain editing revealed by polyubiquitin linkage-specific antibodies. Cell. 2008;134(4):668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varadan R. Walker O. Pickart C. Fushman D. Structural properties of polyubiquitin chains in solution. J Mol Biol. 2002;324(4):637–647. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Varadan R. Assfalg M. Haririnia A. Raasi S. Pickart C. Fushman D. Solution conformation of Lys63-linked di-ubiquitin chain provides clues to functional diversity of polyubiquitin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(8):7055–7063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eddins M J. Varadan R. Fushman D. Pickart CM. Wolberger C. Crystal structure and solution NMR studies of Lys48-linked tetraubiquitin at neutral pH. J Mol Biol. 2007;367(1):204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weeks SD. Grasty KC. Hernandez-Cuebas L. Loll PJ. Crystal structures of Lys-63-linked tri- and di-ubiquitin reveal a highly extended chain architecture. Proteins. 2009;77(4):753–759. doi: 10.1002/prot.22568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]