Abstract

We propose a simple approach, based on the minimization of the total (entropic plus unfolding) energy of a two-state system, to describe the unfolding of multi-domain macromolecules (proteins, silks, polysaccharides, nanopolymers). The model is fully analytical and enlightens the role of the different energetic components regulating the unfolding evolution. As an explicit example, we compare the analytical results with a titin atomic force microscopy stretch-induced unfolding experiment showing the ability of the model to quantitatively reproduce the experimental behaviour. In the thermodynamic limit, the sawtooth force–elongation unfolding curve degenerates to a constant force unfolding plateau.

Keywords: macromolecules unfolding, biopolymers, macromolecule mechanics, protein stability, titin

1. Introduction

The past decade has shown a significant theoretical and experimental effort in the analysis of the thermomechanical behaviour of macromolecular materials such as muscle tissues [1], spider silks [2,3], polymers and biopolymers [4], polysoaps [5,6] and silks in general [7]. A common property of these materials [2,4,8–10] is that their macroscopic history-dependent, dissipative response is the result of complex evolutions of ‘semicrystalline’ microstructures. These are constituted by flexible (polymeric or protein) macromolecules reinforced by strong and stiff crystals (e.g. in the form of fillers or β-sheets [11,12]), undergoing typical hard–soft transitions owing to the unravelling of hard crystal domains into soft unfolded entropic domains. The deduction of predictive models describing the mechanical behaviour of macromolecular materials, connecting the macroscale response with the mesoscale behaviour, is crucial not only for the description of the fundamental polymeric and biopolymeric existing materials, but also in the perspective of the design of new bioinspired or reconstructed biological materials. As a consequence, an intense experimental, numerical and theoretical effort has been recently devoted in this field [11].

From an experimental point of view, a great impulse in the comprehension of the behaviour of these materials has been induced by new experimental techniques [13], such as atomic force microscopy (AFM) [14], laser optical tweezers [15], magnetic tweezers and single-molecule fluorescence techniques. The typical experiment is a mechanically induced unfolding of a macromolecule composed of n unravelling domains, such as a polymeric polypeptide, dextran [16], silks [7], proteins (see [14] for titin and [17] for fibrinogen), DNA/RNA strands [18].

From a theoretical point of view, the thermomechanical behaviour of multi-domain proteins has been investigated following different approaches: molecular dynamics (MD), off lattice models, all atom Monte Carlo approaches (see [19]), phenomenological approaches, statistical mechanics energy landscape analyses, with funnelling [20] and inherent structure models [21]. MD theories [19] have been restricted by the computational effort required to describe the unfolding of such large macromolecules at the AFM loading time scale. On the other hand, the statistical approaches for the discrete chain have been essentially based on numerical techniques, whereas analytical results have been obtained only in the thermodynamic limit hypothesis that hides the crucial role of finite size and discreteness of the unfolding phenomenon.

Schematically, we may describe a typical stretch-induced unfolding (figure 1) of a multi-domain macromolecule as follows [22]. At small elongations, the stiffness is principally regulated by the tertiary structure elasticity. Under increasing stretching, the force–elongation diagram shows periodic discontinuities resulting from (first-order) hard–soft transitions (owing to the secondary structure in the case of proteins where β-sheet unfolding is observed or to cross-link breakage in polymeric networks). These transitions have a main role in the energetics of the chain unfoldings owing to the two following effects: first, there is the enthalpic contribution of the transition itself (debonding energy), then there is an entropic contribution associated with the variation of the microstructure, leading to increased contour lengths of the chains. In the final stage, leading to the material failure, the behaviour is regulated by the entropic hardening of the fully unfolded macromolecules (primary structure).

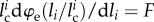

Figure 1.

Scheme of the energetic decomposition of the external work into unfolding (dissipated) energy Qi, i = 1,2,3,4 and elastic stored energy Φe (dashed region) for a typical unfolding force–elongation curve (continuous line) reproduced from [14]. Dashed lines represent approximating worm-like chain curves each characterized by a different contour length Lc(i), i = 1, … , 4; lc represents the (fixed) contour length increase at each unfolding event.

To fix the ideas, in figure 1, we schematically show a typical AFM single-molecule stretching experiment reproduced from [14] on an engineering reconstructed macromolecule. The sawtooth force–length diagram can be described as a stick–slip dynamical evolution in a wiggly energy landscape, characterized by multiple energy wells, each corresponding to a given microstructure configuration. Thus, for growing assigned end-to-end length (see [23]), the chain alternates ‘slow’ (intrabasin) steps in energy wells at fixed folded/unfolded configuration, followed by ‘fast’ (interbasins) transitions corresponding to the unfolding of (typically single) crystals. These transitions are signalled by the periodic localized force drops induced by the entropy jumps owing to the creation of new free monomers. As a result, we observe hysteresis cycles (figure 1) with no permanent deformations resembling the pseudo-elastic hysteresis well known in metal alloys such as shape memory alloys (see [24]) or in rubber elasticity, owing to the polymeric network damage, known as the Mullins effect [25].

The MD approach in [23], based on the inherent structure formalism, clarifies that the observed unfolding is regulated by three main time scales: loading time τload, intrabasin relaxation time τintra and interbasin transition time τinter. Our theoretical model can be applied to the diffuse case when the following time-scale separation hypothesis can be assumed:

| 1.1 |

In this time-scale regime [23], unfolding results as an alternated sequence of purely elastic, intrabasin, stick evolutions and purely dissipative, interbasin, slip transitions, localized at fixed unfolding length thresholds.

In the case of AFM-induced unfolding, the non-dissipative hypothesis of the intrabasin evolution is supported by the observation [15,26] that during the (slip) evolution at fixed folded/unfolded configuration, the behaviour is fully reversible, thus indicating that the system relaxes to the local energy minimum. On the other hand, the fully dissipative hypothesis of the ‘fast’ (stick) interbasin transitions results from the observations (figure 1) that at the AFM loading time scale the β-sheet unfolding events are (mainly) localized at fixed macromolecule end-to-end lengths.

We remark that the time-scale separation (1.1) has been successfully adopted in other stick–slip evolutions associated with abrupt microstructure transitions in multi-valley energy landscapes at ‘low loading rates’ and ‘low temperature regimes’ such as depinning or nucleation of new defects, dislocations and Frank–Read sources in metal plasticity (see [24]), and Barkhausen jumps in ferromagnetism [27]. It is important to observe that under different time-scale regimes (see again [23]), e.g.  , the system can show very different behaviours, with cooperative elastic transitions and no dissipation as observed in other protein unfolding experiments [28].

, the system can show very different behaviours, with cooperative elastic transitions and no dissipation as observed in other protein unfolding experiments [28].

By energy conservation (Gibbs equation), under our hypothesis (1.1), the external work (see [24] for a theoretical discussion) can be decomposed as follows. By focusing again on the AFM experiment in figure 1, suppose that we begin stretching the macromolecule from its natural state. The macromolecule follows elastically the first equilibrium path (O–A in figure 1) with the external work W accumulated as elastic energy Φe (ΔW = ΔΦe). At the first β-sheet unfolding (path O–B)—here approximated as instantaneous with no external work W—there is an internal energy discontinuity [|Φ|]1 (area O–A–B) that by energy conservation equals the unfolding energy Q1 of the first hard domain. Similar considerations can be extended to the next elastic and dissipative steps, so that the total dissipation is Q = ∑Qi = ∑[|Φ|]i.

Based on previous considerations and inspired by the model in [2,29], where the authors describe the hysteresis of filled polymers and spider silks, here we propose an energetic approach and describe the unfolding macromolecule as a two-state material. Similarly, a two-state energetic approach was proposed in [30] to describe the helix → coil transition of polypeptide chains regulating the damage of multi-block copolymers. In this work, we obtained an analytic solution in the thermodynamic limit of a large number of breakable links. Recently [31] a statistical mechanics approach for a discrete two-well finite size chain has been proposed describing the force–extension diagrams of polymeric chains under assigned force (soft device) or end-to-end length (hard device). In particular, numerical results let us describe the sawtooth behaviour observed in a hard device.

In the field of protein mechanics, on the basis of the approach proposed in [30], an important step in the comprehension of the energy competition between the unfolding and entropic energy terms, has been delivered in [32]. In this paper, the author models the unfolding of a biomacromolecule as a chain composed of folded and unfolded domains, both elastic with Gaussian type response, combined with an Ising-type unfolding energy. The resulting MD simulation well describes the unfolding effect in a protein macromolecule, whereas analytical results are obtained only in the thermodynamic limit of many folded domains [32].

More recently, in [33], a statistical mechanics-based model for the stretching of titin proteins has been proposed, considering also the influence of the AFM loading device. A simple Ising model, neglecting the elasticity of both folded and unfolded domains in protein macromolecules, was instead proposed in [34] to describe the statistics of unfolding events. The described competition between the entropic energy of the unfolded fraction and the β-sheet unfolding energy has been analysed in [35,36] via Monte Carlo simulations combining a worm-like chain (WLC) with a two-state bell-type model for the unfolding. Finally, we recall the fully phenomenological continuum approaches recently proposed in [37,38] where the authors show the possibility of describing the protein unfolding as an energy minimization of a continuum system with a non-convex internal energy. In particular in [37], based on the general approach of [24,39] for the description of the mechanical behaviour of bistable discrete chains, the authors obtain an interesting characterization of an optimality condition of the number of β-sheet domains with respect to the toughness of the macromolecule.

The aim of this work is to obtain a fully analytical model, resulting from the energetic analysis and time-scale decomposition discussed previously, represented by a two-state lattice, describing the stretch-induced unfolding of macromolecules and the corresponding energy decomposition into stored and ‘dissipated’ energy. Interestingly, the analysis of this discrete bi-stable chain shows the existence of a fundamental, experimentally measurable, non-dimensional parameter ξ, defined in (3.8), representing the ratio of the elastic and unfolding energy of the single folded domains, that regulates the dissipation and the unfolding thresholds of each folded/unfolded phase configuration. The model is also extended to describe the possibility of the existence of a hierarchy of variable unfolding energies of the different folded domains. As we show, the effective distribution of unfolding energies can be deduced on the basis of the previously described energetic analysis, using the experimental force–elongation diagrams. Notably, after performing such an analysis for different macromolecule experimental curves, we obtain simple phenomenological linear dissipation energy distributions. The predictivity of the proposed model relies on the new theoretical (MD and all atom simulations) and experimental techniques permitting the independent evaluation of the main dimensional parameter ξ [40–42] and possibly its inhomogeneity and rate-dependent expression [36].

Aimed at the deduction of a three-dimensional continuum extension for biological tissues constituted by networks of modular macromolecules [43], we also deduce the thermodynamic limit of the proposed discrete model. The main advantage of our theoretical approach is that the behaviour of the single chain also in the continuum limit is regulated by the experimentally measurable parameter ξ that fully characterizes the unfolding behaviour of the macromolecule: unfolding force, initial unfolding stretch, stretch for unfolding saturation.

Finally, as an explicit example, we focus on the AFM experiments of titin unfolding. It is important to point out that such experiments often show rate-dependent effects, because at the AFM loading time scale the β-sheet unfolding transitions represent out of equilibrium events (e.g. the analysis performed by extending the Kramer reaction theory in [44,45] or the MD analysis in [23]). Here, aimed again to the deduction of a fully analytical approach, following [11,23,36,46], we take care of the described rate dependence by considering effective, rate-dependent unfolding energies.

2. Energetic assumptions

Because in macromolecules the hard crystal unfolding is typically an all-or-none transition, as confirmed also from the size of periodicity of the experimental unfolding lengths [14] in the case of titin, we model the molecule as a discrete lattice of n two-state (rigid-folded/entropic-unfolded) links (see the scheme in figure 1). The folded/unfolded state of the chain is assigned by a set of internal variables χi, i = 1, … , n, such that χi = 0 (χi = 1) denotes the folded (unfolded) state of the ith domain. Thus, in particular,  is the number of unfolded elements and nf = n − nu is the number of folded elements.

is the number of unfolded elements and nf = n − nu is the number of folded elements.

As in the case of freely jointed chain or WLC models [47], we characterize the behaviour of each unfolded link through its contour length lc and end-to-end length l, with a free energy density (energy per unit length) φe = φe(η), where η:= l/lc represents a strain measure. We assume then the limit extensibility condition limη → 1φe(η) = ∞.

Consider first the entropic energy of the unfolded fraction. By neglecting non-local interactions (weak interaction hypothesis), it is possible to show that the total elastic energy  can be simply expressed as

can be simply expressed as

| 2.1 |

Here,

is the strain in the unfolded domain,

is (by neglecting the extension of the folded domains) the total end-to-end length, and

| 2.2 |

is the total contour length of the chain. In (2.2), L0 denotes the ‘initial’ (virgin) contour length of the unfolded domain.

Indeed, at equilibrium, by neglecting the elastic energy of the (rigid) folded domains, the total elastic energy is given by  , where

, where  and li are the (possibly variable) contour length and end-to-end length of the ith link in the unfolded state (χi = 1). Under an equilibrium hypothesis, we have a constant force F for all unfolded links, i.e.

and li are the (possibly variable) contour length and end-to-end length of the ith link in the unfolded state (χi = 1). Under an equilibrium hypothesis, we have a constant force F for all unfolded links, i.e.  . Thus, for a convex energy density (monotonic derivative

. Thus, for a convex energy density (monotonic derivative  ), such as WLC or FLC, the strain is homogeneous in all unfolded elements, i.e.

), such as WLC or FLC, the strain is homogeneous in all unfolded elements, i.e.  , for all i = 1, … , n with χi = 1. Thus, we have

, for all i = 1, … , n with χi = 1. Thus, we have  .

.

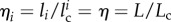

Consider now the configurational energy associated with the different folded/unfolded states. Following [30,32], here we consider an Ising-type transition energy

|

depending on the internal variables χi and the number  of contiguous folded blocks in the folded/unfolded configuration. Here, Q is the unfolding energy for a single domain and J is a penalizing ‘interfacial’ energy term (measuring the loss of internal energy owing to the unbind terminal hydrogen bonds of each contiguous folded domain [30]).

of contiguous folded blocks in the folded/unfolded configuration. Here, Q is the unfolding energy for a single domain and J is a penalizing ‘interfacial’ energy term (measuring the loss of internal energy owing to the unbind terminal hydrogen bonds of each contiguous folded domain [30]).

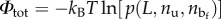

To get the total energy  (where T is the temperature and kB is the Boltzmann constant), we have to know the probability

(where T is the temperature and kB is the Boltzmann constant), we have to know the probability  of a given configuration of the chain with a microstructure corresponding to nu and

of a given configuration of the chain with a microstructure corresponding to nu and  and end-to-end length L. In particular, we have

and end-to-end length L. In particular, we have  , where

, where  represents the number of sequences with assigned nu and

represents the number of sequences with assigned nu and  , pe(L,nu) ∼ exp(−Φe(L,nu)/kBT) represents the probability of attaining a length L at given nu and

, pe(L,nu) ∼ exp(−Φe(L,nu)/kBT) represents the probability of attaining a length L at given nu and

is the probability of a state with assigned nu. So, we obtain

is the probability of a state with assigned nu. So, we obtain  where

where  represents a mixing entropy component.

represents a mixing entropy component.

Observe that the coupling energy term J penalizes the multiplicity of folded blocks, whereas the mixing entropy term induces multi-domain configurations. In the following, we assume, as in [30], that the penalizing term J dominates this effect, so that we always consider single folded domain configurations (thus we assume  : di-block approximation). This hypothesis is supported by the MD simulations [22] showing an unfolding strategy with always one single connected internal unfolded domain inside two boundary-folded domains.

: di-block approximation). This hypothesis is supported by the MD simulations [22] showing an unfolding strategy with always one single connected internal unfolded domain inside two boundary-folded domains.

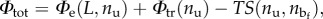

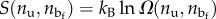

Under these hypotheses, we obtain the simple expression of the total energy

| 2.3 |

We remark that to avoid the introduced di-block approximation, not always experimentally verified, one needs to evaluate the partition function [32,33] and only numerical results in the discrete model can be obtained. Moreover, stochastic processes considering fluctuations in both the unfolding forces [48] and the unfolding lengths are possible extensions of the proposed model. In addition, these extensions require the applications of numerical approaches.

3. Energy minimization

Consider the WLC force–length relation proposed in [49]

|

3.1 |

corresponding to an energy density

| 3.2 |

Thus, using (2.1), the adimensionalized total entropic energy of the unfolded fraction can be written as

| 3.3 |

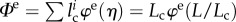

In order to obtain analytical solutions, we consider the following simplified expression of the WLC energy density:

| 3.4 |

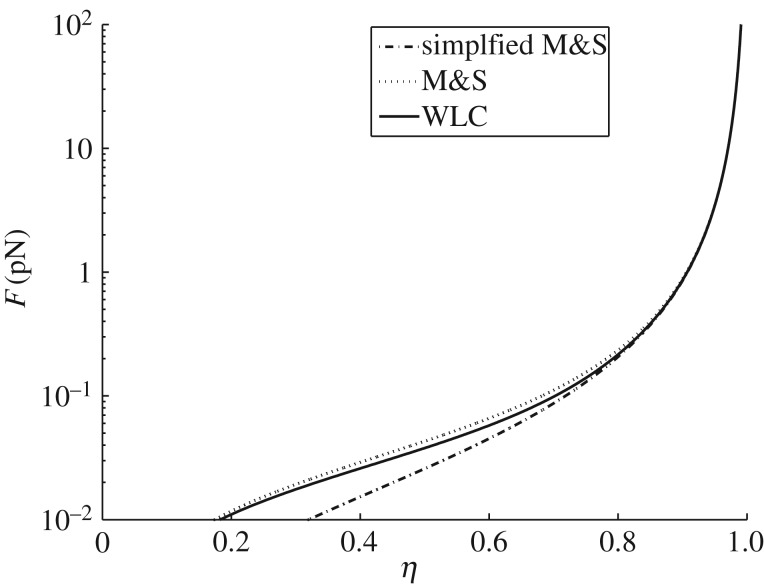

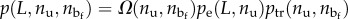

Observe that this approximation keeps the same asymptotic behaviour as l → lc of the WLC model in (3.3). Figure 2 shows (in a log scale, stressing the differences at low values of the force) that, while for low forces (F < 10−1 pN) the introduced approximation is significant (when compared with the approximation in [49]), for larger forces the approximation is of the same order (actually approximating better than [49] the WLC expression) as the one proposed by [49]. Because in the low force regime the elasticity is mainly regulated by the PEVK and tertiary structure elasticity (see [50,22] for details), this approximation appears inessential in both the qualitative and the quantitative analysis of the behaviour during the large-force unfolding regime of interest in this paper. Moreover, we remark that the approximation (3.1) has been shown to be inefficient in the low force regime in [51], where the authors introduce a Mooney–Rivlin-type correction to the WLC constitutive law.

Figure 2.

Force–strain curve (log-scale evidences the differences in the low force regime) for the WLC compared with the usual Marko & Siggia [49] approximation (M&S) and with the simplified model in (3.5) for lp = 0.42 nm. Observe that the proposed approximation keeps the same asymptotic behaviour as l→lc of (3.3) and that for F > 10−1 pN the approximation is of the same order as that of [49].

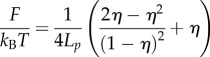

Thus, using (2.1) and (2.2), the total elastic energy is

and, correspondingly, the total force–deformation relation is

|

3.5 |

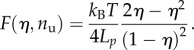

Finally, according to (2.3), the total energy is

| 3.6 |

We follow a Griffith-like approach [52], minimizing the total unfolding (fracture) energy plus elastic (entropic) energy, and based on (1.1) we assume that the observed solutions are the global minima of Φtot in (3.6).

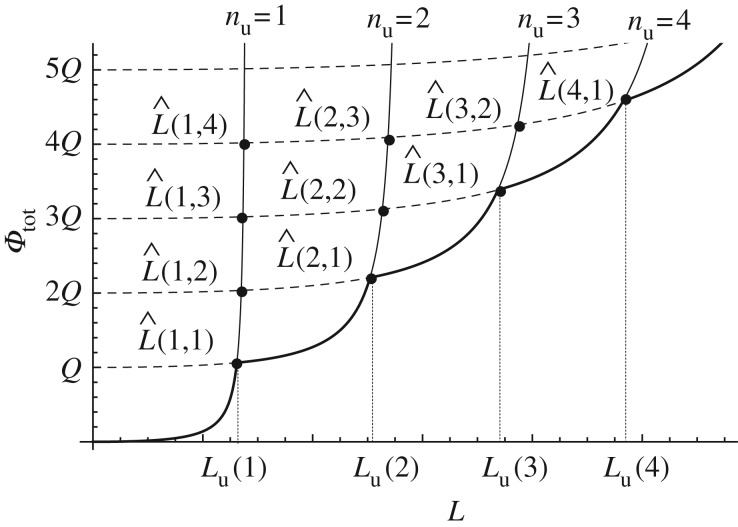

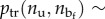

The first important step is to justify the experimental observation that the hard crystals unfold one at a time, resulting in a constant increase of the contour length (see [14]). To obtain this result, we begin by evaluating the solution of the equations Φtot(L, nu + m) − Φtot(L, nu) = 0 and get the intersection lengths  (figure 3). The searched result follows by the observation that

(figure 3). The searched result follows by the observation that  so that if

so that if  is the branch corresponding to the global minimum at assigned end-to-end length L, by increasing L it loses its global stability at the intersection with the equilibrium branch

is the branch corresponding to the global minimum at assigned end-to-end length L, by increasing L it loses its global stability at the intersection with the equilibrium branch  (figure 3). Thus, the chain unfolds with a sequence of single hard domain transitions at the threshold assigned by

(figure 3). Thus, the chain unfolds with a sequence of single hard domain transitions at the threshold assigned by  :

:

| 3.7 |

(in this formula and in the following, we omit the nu dependence of Lc).

Figure 3.

Scheme of the energy minimization: with bold line we represent stable (global energy minimum) solutions.

In (3.7), we introduced the main non-dimensional parameter of the model

| 3.8 |

representing a measure of the ratio between the elastic and fracture energy of the single β-sheet. Indeed, we observe that according to (3.2) we have that the term kBTlc/8Lp = φe(1/2)lc, so that it measures the elastic energy of a single domain when the deformation is a half of the maximum elongation (contour length).

It is easy to verify that Lu∈(0, Lc) and that dLu/dnu > 0. As a result, the nu branch corresponds to the global energy minimum for

representing the existence domain of the nu branch under our energy minimization hypothesis. In the special cases of the virgin curve, with nu = 0, we have L∈(0, Lu(0)), whereas in the case of the fully unfolded chain, with nu = n, we have L∈(Lu(n−1), Lr), where Lr is the fracture threshold of the fully unfolded chain (figure 6).

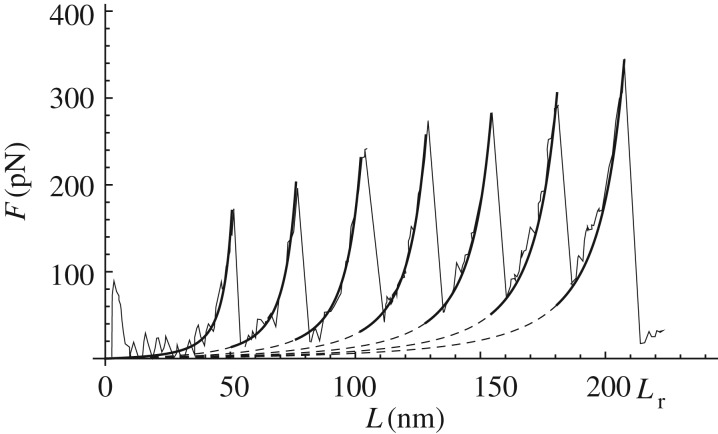

Figure 6.

Comparison between the AFM experiment for the titin protein reproduced from [14] (continuous curves) and the force versus elongation curves deduced by (3.5), (3.7), (4.3) and (4.2) (bold lines). Here, we considered the parameters: lo = 58 nm, lc = 28.43 nm, lp = 0.36 nm, Q = 770kBT, ΔQ = 420kBT.

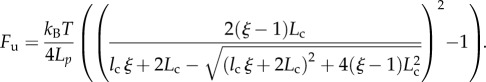

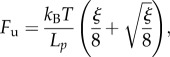

Using (3.5), we get the unfolding force Fu = F(Lu/Lc, nu)

|

3.9 |

Observe that using (3.7) and (3.9), it is also possible to obtain an explicit relation between the unfolding forces and the unfolding end-to-end lengths

|

3.10 |

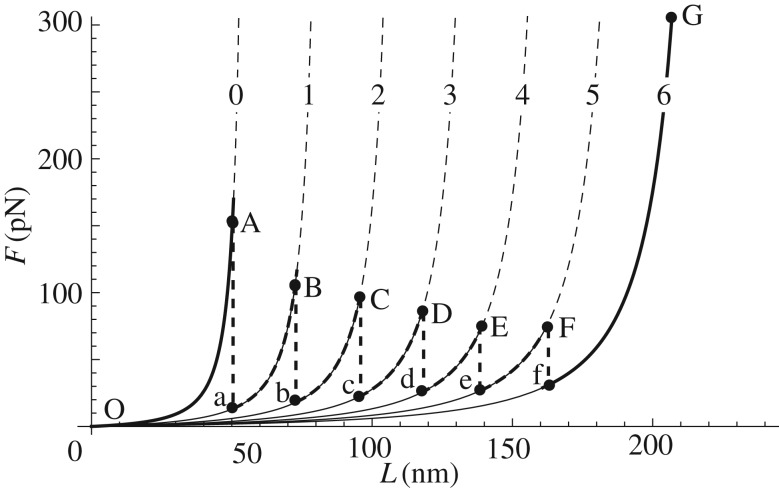

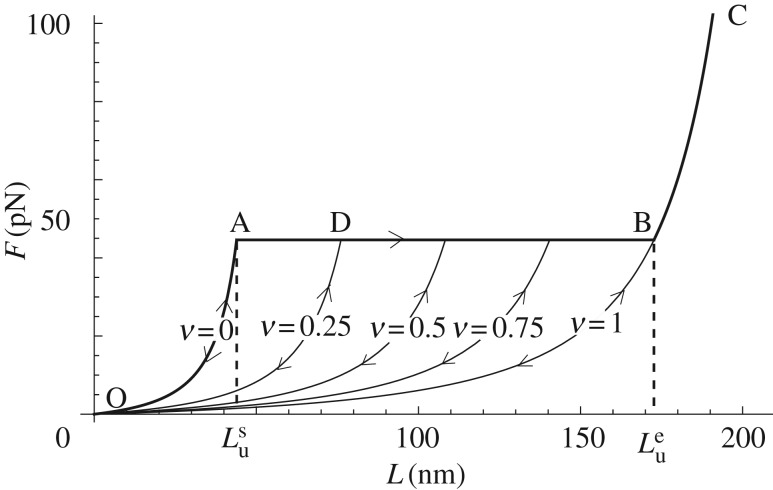

The stretch-induced unfolding of the system is shown with bold line in figure 4. The system reproduces the typical experimental behaviour of unravelling macromolecules with a regularly spaced sequence of unfolding events of the hard domains. Thus, if we start loading from the virgin configuration (nu = 0, point O in figure 4), the system follows elastically the equilibrium curve nu = 0 until the unfolding energy Q equals the jump of the entropic energy owing to the transition from the branch nu = 0 to the branch nu = 1 (path A–a in figure 4). By increasing further the assigned length, the system follows the new branch until another sudden transition to the branch nu = 2 is observed when it becomes energetically favourable (path B–b). Similar transitions with single domain unfoldings are then observed, until all the crystals unfold and the system shows a hardening behaviour owing to the entropic elasticity of the fully unfolded chain (curve f–G in figure 4).

Figure 4.

Unfolding behaviour for a system of n = 6 initial folded domains. Here, we considered the parameters: lo = 58 nm, lc = 28.43 nm, lp = 0.36 nm, Q = 770kBT, ΔQ = 420kBT. Each equilibrium path is labelled by the number nu of unfolded domains.

Regarding the behaviour of the system under unloading, because typically at the AFM loading rate no refolding is observed [53], we assume irreversible (hard–soft) transitions. As a result if the system is unloaded at a given equilibrium branch  the system follows this branch until both stretch and force go to zero. Under reloading the system instead changes again configuration with another hard–soft transition at the same value of primary loading

the system follows this branch until both stretch and force go to zero. Under reloading the system instead changes again configuration with another hard–soft transition at the same value of primary loading  . The memory of the system is then restricted to the only maximum value attained in the past by the end-to-end length L.

. The memory of the system is then restricted to the only maximum value attained in the past by the end-to-end length L.

Finally, we observe that the theoretical model shows a softening behaviour during the unfolding regime, in the sense that the unfolding force decreases with the number nu of unfolded domains. This can be analytically proved by observing that in view of (3.10) we have ∂F(Lu(nu))/∂nu < 0. Nevertheless, the experimental behaviour of stretch-induced unfolding of macromolecules shows a variable behaviour, with typically nearly constant unfolding forces [54], but with possibly increasing, decreasing or non-monotonic transition thresholds (see [14] for titin macromolecule and [55] for artificial elastomeric protein).

In the following section, we discuss this issue and propose an extension of our model able to reproduce the hardening effect observed, e.g. in titin macromolecule unfolding.

4. Unfolding energy hierarchy

The described variable observations on subsequent transition forces (force plateaux, hardening, softening) have been given different physical interpretations. A hierarchy of unfolding energies of the unfolding crystals may be simply due to inhomogeneity effects of the crystal domains [14,35,56], showing variable bond-breaking barriers [33] possibly owing to interfacial energy effects [57]. Another important effect is anisotropicity of the crystals with respect to the force direction—different paths in the wiggly energy landscape lead to different unfolding energy barriers [58]—so that different unfolding forces can be induced by variable crystal orientations in the macromolecule. Another known effect, that can induce hardening, is the so-called n-effect (see [58]) that, based on statistical considerations, leading to an unfolding force growth owing to a progressively reduced number of folded crystals available for unfolding in the macromolecule for growing elongations.

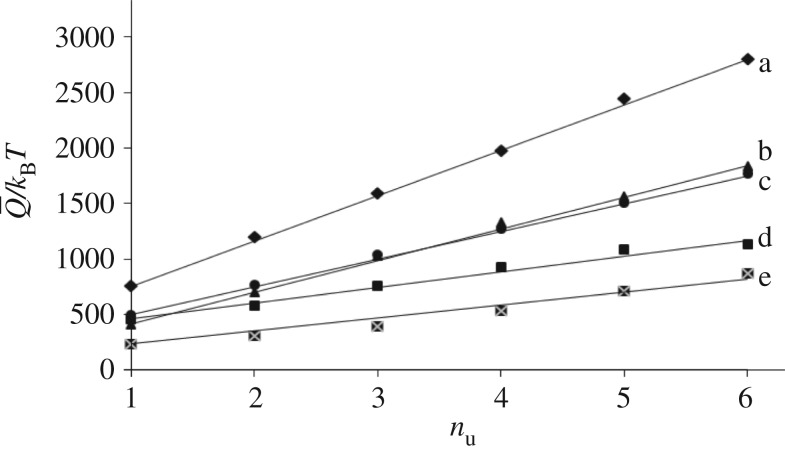

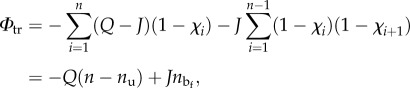

To check the possibility of variable unfolding energies, following the energetic decomposition schematized in figure 1, based on the experimental force–displacement unfolding diagrams we may estimate the fracture energy of each unfolding event using the relation

| 4.1 |

where  represents the variable fracture energy of the nu-th folded domain and ηu = Lu(nu)/Lc(nu) is the corresponding unfolding strain. Based on this relation, we analysed the experimental length–force diagrams for different unfolding macromolecules: titin in [14,48,59], TNfnAll protein from [60] and tenascin-C from [54]. The results are summarized in figure 5 and interestingly all show a linear phenomenological growing law for the dissipation energy of successive unfolding domains

represents the variable fracture energy of the nu-th folded domain and ηu = Lu(nu)/Lc(nu) is the corresponding unfolding strain. Based on this relation, we analysed the experimental length–force diagrams for different unfolding macromolecules: titin in [14,48,59], TNfnAll protein from [60] and tenascin-C from [54]. The results are summarized in figure 5 and interestingly all show a linear phenomenological growing law for the dissipation energy of successive unfolding domains

| 4.2 |

where  represents the fracture energy of the weakest folded domain, which has the important role of regulating the stability of the initial unfolded configuration and the initial unfolding length Lu(1), whereas ΔQ is a fixed energy increment for successive unfolding events (figure 5).

represents the fracture energy of the weakest folded domain, which has the important role of regulating the stability of the initial unfolded configuration and the initial unfolding length Lu(1), whereas ΔQ is a fixed energy increment for successive unfolding events (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Unfolding energies as a function of nu deduced from the following experiments: (a) AFM experiment on titin from [14]; (b) AFM experiment on TNfnAll protein from [60]; (c) AFM experiment on titin from [48]; (d) AFM experiment on tenascin-C from [54]; (e) AFM experiment on titin from [59].

It is important to remark that in the case of increasing unfolding energies, the di-block approximation can fail, with the order of unfolding that is regulated by the competition of mixing energy, interfacial energy effects and variability of the unfolding energy. This competition regulates in the quasi-static regime the order of transition and the hardening, softening or non-monotonic law of the successive unfolding force. Aimed again at a fully analytical result, we here suppose that both the mixing entropy contribution and the interfacial energy term are negligible when compared with the unfolding energy increment ΔQ so that the unfolding evolution strategy is regulated by the unfolding energy hierarchy and we may again describe the stretching behaviour of the macromolecule by minimizing an energy as in (3.6), but with variable unfolding energy increments. Indeed, (3.6) is obtained by simply considering ΔQ = Q in (4.2).

Under the considered assumption, we may first extend the considerations described in figure 3 to obtain that the domains unfold one at a time in the order of their unfolding energies. Then, we may again explicitly evaluate the unfolding lengths (3.7) and forces (3.9) by simply using (3.7) with a variable parameter

| 4.3 |

measuring the variable ratio of dissipated and elastic energy of the folded domains.

5. An explicit example: titin unfolding

To show the feasibility of the proposed model in quantitatively predicting the experimental behaviour of macromolecule unfolding, in this section, we analyse the diffusely studied AFM stretching experiments of titin, the protein responsible of the passive strength of muscles. These proteins are very long macromolecules with contour length larger than 1 μm [1], whose secondary structure is characterized by the presence of immunoglobulin (Ig) and fibronectin-type III (FNIII) domains, folded in forms of β-sheets, connected to the PEVK domain (rich in proline, glutamate, valine and lysine) [61]. At low forces, the elasticity is regulated by the tertiary structure and the (random coil) domain orientation, combined with the elasticity of PEVK domains [22,57,61]. At higher forces, the macromolecule response is dominated by an energetic competition of the entropic elasticity of the unfolded fraction of (Ig) and (FNIII) domains and by the enthalpic contribution of the folded → unfolded transition of the β-sheets.

One important effect in the case of titin is the rate-dependent behaviour of the unfolding events [14] whose detailed description has been addressed through MD approaches [23] and reaction theory approaches [44]. Here, as anticipated above, following [11,23,36,46], we take care of the observed rate dependence (i.e. rate-dependent unfolding energy barriers and dissipation) by considering effective rate-dependent dissipation energies Qi.

In figure 6, we show the ability of the model in describing quantitatively the behaviour of titin unfolding experiments reported in [14] based on the obtained analytical relations (3.5), (3.7) and (4.3) with an energy hierarchy as in (4.2) deduced based on the experiments in [14] as reported in figure 5a.

6. Continuum limit

Here, aimed to a deduction of a continuum model for macromolecular materials [2], we analyse the continuum limit of the proposed model, obtained as a limit when n → ∞. To get this limit, we fix the total unfolded length that using (2.2) is given by

| 6.1 |

and consider the limit when both lc → 0 and n → ∞. Introduce then the new continuum variable

representing the unfolded fraction. In the language of continuum mechanics νu represents a damage (internal) variable, with νu∈(0, 1) and νu = 0 in the virgin state and νu = 1 in the fully unfolded state [62,63]. The total contour length is then using (2.2) given by

| 6.2 |

Thus, the damage variable νu measures the change of contour length with in particular Lc = L0 in the virgin configuration (νu = 0) and  , as in (6.1), in the damage saturation configuration of the fully unfolded state (νu = 1).

, as in (6.1), in the damage saturation configuration of the fully unfolded state (νu = 1).

The total energy, using (3.6), can be rephrased as

| 6.3 |

where we introduced the rescaled unfolding energy

ensuring that  decreases proportionally to the length lc of the unfolded single elements. Here, in view of (6.2), the deformation variable depends on the continuum damage variable νu according to the following relation:

decreases proportionally to the length lc of the unfolded single elements. Here, in view of (6.2), the deformation variable depends on the continuum damage variable νu according to the following relation:

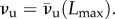

| 6.4 |

The obtained framework can be inscribed in the classical variational approach for damage known as pseudo-elasticity [64], requiring the minimization of the damage-dependent energy (6.3) under the constraint of irreversibility of unfolding. We refer the reader to [29] for the technical details of the variational approach, whereas we here resume the loading–unloading behaviour of the deduced continuum damage model. Based on our irreversibility assumption (no refolding), we may observe that also in the continuum damage model the memory of the loading history depends on the only value Lmax of the maximum end-to-end length attained in the past that assigns νu. Indeed (see again [29] for technical details), during loading (L = Lmax) to determine the global minimum of the energy (6.3), we minimize both with respect to L and νu. Minimization with respect to L (i.e.  ) delivers the equilibrium force as in (3.5) with the deformation variable defined in (6.4). Minimization with respect to νu (i.e.

) delivers the equilibrium force as in (3.5) with the deformation variable defined in (6.4). Minimization with respect to νu (i.e.  ) delivers the damage as a function of the assigned length

) delivers the damage as a function of the assigned length

| 6.5 |

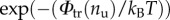

Interestingly, using (3.10), in this limit we obtain a constant unfolding force plateau

|

that by (6.5) begins (νu = 0) at

and ends at

where the fully unfolded state (νu = 1) is attained. The obtained unfolding behaviour is shown in figure 7 (path OABC). During unloading (L < Lmax), because we neglect refolding, the behaviour is again given by (3.5) with fixed damage that by (6.5) is given by  Different unloading paths are shown in figure 7 (e.g. path DO is attained for an unloading at νu = 0.25).

Different unloading paths are shown in figure 7 (e.g. path DO is attained for an unloading at νu = 0.25).

Figure 7.

Unfolding behaviour of the lattice in the thermodynamic limit. Bold lines represent the loading path, whereas continuous lines the unloading paths at different values of the unfolded fraction νu and maximum end-to-end length. Here, we used the same parameters as figure 4.

7. Conclusion

In this paper, we propose, based on the time-scale separation (1.1), an energetic model for the description of the important phenomenon of stretch-induced unfolding of macromolecules. By considering a di-block approximation and by neglecting rate-dependent effects (possibly considering rate-dependent effective unfolding energies), we deduced a fully analytical model delivering the unfolding forces and lengths for the different equilibrium branches, all depending on a deduced main dimensional parameter ξ. Despite the important simplifications underlying the proposed model, the availability of a fully analytical model (available only in the thermodynamic limit for previously proposed models) let us clarify the main ingredients regulating the energetics underlying stretch-induced unfolding in multi-domain macromolecules. The analytical results for the (finite) discrete lattice have been also extended to the case of inhomogeneous unfolding energies based on the empirical law (4.2) that we deduced by analysing typical macromolecule unfolding experiments. The deduced analytical model shows a good qualitative (stick–slip unfolding evolution with regular spacing of the localized unfolding events) and quantitative agreement (figure 6) with the experimental behaviour and elucidates the experimentally determinable variables  in (4.3) regulating the mechanical behaviour of the chains. Finally, we deduced a continuum limit one-dimensional system available for three-dimensional extension to study the mechanical behaviour of biological and polymeric tissues and networks of modular macromolecules [43] that will be the subject of our future studies and that appears particularly valuable also in the perspective of analytical criteria in the new important technological field of the design of new bioinspired materials.

in (4.3) regulating the mechanical behaviour of the chains. Finally, we deduced a continuum limit one-dimensional system available for three-dimensional extension to study the mechanical behaviour of biological and polymeric tissues and networks of modular macromolecules [43] that will be the subject of our future studies and that appears particularly valuable also in the perspective of analytical criteria in the new important technological field of the design of new bioinspired materials.

Acknowledgements

G.S. is grateful to the Istituto Nazionale di Alta Matematica (Italy) and PRIN 2009 Matematica e meccanica dei sistemi biologici e dei tessuti molli for financial support.

Funding statement

The work of D.D. and G.P. has been supported by Progetto di ricerca industriale-Regione Puglia, ‘Modelli innovativi per sistemi meccatronici’ and PRIN 2010–11: ‘Dinamica, stabilità e controllo di strutture flessibili’ (Dynamics, stability and control of slender structures).

References

- 1.Wang K. 1996. Titin/connectin and nebulin: giant protein rulers of muscle structure and function. Adv. Biophys. 33, 123–134. ( 10.1016/0065-227X(96)81668-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Tommasi D, Puglisi G, Saccomandi G. 2010. Damage, self-healing, and hysteresis in spider silks. Biophys. J. 98, 1941–1948. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.01.021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oroudjev E, Soares J, Arcidiacono S, Thompson JB, Fossey SA, Hansma HG. 2002. Segmented nanofibers of spider dragline silk: atomic force microscopy and single-molecule force spectroscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6460–6465. ( 10.1073/pnas.082526499) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrington MJ, Wasko SS, Masic A, Fischer FD, Gupta HS, Fratzl P. 2012. Pseudoelastic behaviour of a natural material is achieved via reversible changes in protein backbone conformation. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 2911–2922. ( 10.1098/rsif.2012.0310) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borisov OV, Halperin A. 1996. On the elasticity of polysoaps: the effects of secondary structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 34, 657–662. ( 10.1209/epl/i1996-00511-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borisov OV, Halperin A. 1997. On the extension of polysoaps: the Gaussian approximation. Macromol. Symp. 113, 11–17. ( 10.1002/masy.19971130104) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shulhaa H, Foob CWP, Kaplanb DL, Tsukruka VV. 2006. Unfolding the multi-length scale domain structure of silk fibroin protein. Polymer 47, 5821–5830. ( 10.1016/j.polymer.2006.06.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazakevicuite-Makovska R, Steeb H. 2011. Superelasticity and self-healing of proteinaceous biomaterials. Proc. Eng. 10, 2597–2602. ( 10.1016/j.proeng.2011.04.432) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miserez A, Wasko SS, Carpenter CF, Waite JH. 2009. Non-entropic and reversible long-range deformation of an encapsulating bioelastomer. Nat. Mater. 8, 910–916. ( 10.1038/nmat2547) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Termonia Y. 1994. Molecular modeling of spider silk elasticity. Macromolecules 27, 7378–7381. ( 10.1021/ma00103a018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buehler MJ, Yung YC. 2009. Deformation and failure of protein materials in physiologically extreme conditions and disease. Nat. Mater. 8, 175–188. ( 10.1038/nmat2387) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin Z, Buehler MJ. 2010. Cooperative deformation of hydrogen bonds in beta-strands and beta-sheet nanocrystals. Phys. Rev. E 82, 061906 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.061906) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritort F. 2006. Single-molecule experiments in biological physics: methods and applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 18, R531–R583. ( 10.1088/0953-8984/18/32/R01) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rief M, Gautel M, Oesterhelt F, Fernandez JM, Gaub HE. 1997. Reversible unfolding of individual titin immunoglobulin domains by AFM. Science 276, 1109–1112. ( 10.1126/science.276.5315.1109) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellermayer MSZ, Smith SB, Granzier HL, Bustamante C. 1997. Folding–unfolding transitions in single titin molecules characterized with laser tweezers. Science 276, 1112–1116. ( 10.1126/science.276.5315.1112) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rief M, Oesterhelt F, Heymann B, Gaub HE. 1997. Single molecule force spectroscopy on polysaccharides by atomic force microscopy. Science 275, 1295–1297. ( 10.1126/science.275.5304.1295) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown AEX, Litvinov RI, Discher DE, Weisel JW. 2007. Forced unfolding of coiled-coils in fibrinogen by single-molecule AFM. Biophys. J. 92, L39–L41. ( 10.1529/biophysj.106.101261) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith SB, Cui Y, Bustamante C. 1996. Overstretching B-DNA: the elastic response of individual double-stranded and single-stranded DNA molecules. Science 271, 795–799. ( 10.1126/science.271.5250.795) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirny L, Shakhnovich E. 2001. Protein folding theory: from lattice to all-atom models. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 30, 361–396. ( 10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.361) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jha SK, Udgaonkar JB. 2010. Free energy barriers in protein folding and unfolding reactions. Curr. Sci. 99, 457–475. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakagawa N, Peyrard M. 2006. The inherent structure landscape of a protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 5279–5284. ( 10.1073/pnas.0600102103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsin J, Strümpfer J, Lee EH, Schulten K. 2011. Molecular origin of the hierarchical elasticity of titin: simulation, experiment, and theory. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 40, 187–203. ( 10.1146/annurev-biophys-072110-125325) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacks DJ. 2005. Energy landscape distortions and the mechanical unfolding of proteins. Biophys. J. 88, 3494–3501. ( 10.1529/biophysj.104.051953) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puglisi G, Truskinovsky L. 2005. Thermodynamics of rate-independent plasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 53, 655–679. ( 10.1016/j.jmps.2004.08.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Tommasi D, Puglisi G, Saccomandi G. 2006. A micromechanics-based model for the Mullins effect. J. Rheol. 50, 495–512. ( 10.1122/1.2206706) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duff N, Duong NH, Lacks DJ. 2006. Stretching the immunoglobulin 27 domain of the titin protein: the dynamic energy landscape. Biophys. J. 91, 3446–3455. ( 10.1529/biophysj.105.074278) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertotti G. 1998. Hysteresis in magnetism. Boston, MA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwaiger I, Sattler C, Hostetter DR, Rief M. 2002. The myosin coiled-coil is a truly elastic protein structure. Nat. Mater. 1, 232–235. ( 10.1038/nmat776) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Tommasi D, Puglisi G, Saccomandi G. 2008. Localized versus diffuse damage in amorphous materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 085502 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.085502) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buhot A, Halperin A. 2000. Extension of rod-coil multiblock copolymers and the effect of the helix-coil transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2160–2163. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.2160) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manca F, Giordano S, Palla PL, Cleri F, Colombo L. 2013. Two-state theory of single-molecule stretching experiments. Phys. Rev. E 87, 032705 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.87.032705) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makarov DE. 2009. A theoretical model for the mechanical unfolding of repeat proteins. Biophys. J. 96, 2160–2167. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3899) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staple DB, Payne SH, Reddin ALC, Kreuzer HJ. 2008. Model for stretching and unfolding the giant multidomain muscle protein using single-molecule force spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 248301 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.248301) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kajander T, Cortajarena AL, Main ERG, Mochrie SGJ, Regan L. 2005. A new folding paradigm for repeat proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 10 188–10 190. ( 10.1021/ja0524494) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rief M, Fernandez JM, Gaub HE. 1998. Elastically coupled two-level systems as a model for biopolymer extensibility. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 4764–4767. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.4764) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritort F, Bustamante C, Tinoco I. 2002. A two-state kinetic model for the unfolding of single molecules by mechanical force. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13 544–13 548. ( 10.1073/pnas.172525099) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benichou I, Givli S. 2011. The hidden ingenuity in titin structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 091904 ( 10.1063/1.3558901) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raj R, Purohit PK. 2011. Phase boundaries as agents of structural change in macromolecules. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 59, 2044–2069. ( 10.1016/j.jmps.2011.07.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puglisi G, Truskinovsky L. 2002. A mechanism of transformational plasticity. Cont. Mech. Therm. 14, 437–457. ( 10.1007/s001610200083) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Best RB, Fowler SB, Toca Herrera JL, Steward A, Paci E, Clarke J. 2003. Mechanical unfolding of a titin Ig domain: structure of transition state revealed by combining atomic force microscopy, protein engineering and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 330, 867–877. ( 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00618-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fersht AR, Daggett V. 2002. Protein folding and unfolding at atomic resolution. Cell 108, 573–582. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00620-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vendruscolo M, Paci E. 2003. Protein folding: bringing theory and experiment closer together. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13, 82–87. ( 10.1016/S0959-440X(03)00007-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi HJ, Ortiz C, Boyce MC. 2006. Mechanics of biomacromolecular networks containing folded domains. Trans. ASME J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 128, 509–518. ( 10.1115/1.2345442) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evans E, Ritchie K. 1997. Dynamic strength of molecular adhesion bonds. Biophys. J. 72, 1541–1555. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78802-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans E, Ritchie K. 1999. Strength of a weak bond connecting flexible polymer chains. Biophys. J. 76, 2439–2447. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77399-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bryngelson JD, Onuchic JN, Socci ND, Wolynes PG. 2004. Funnels, pathways, and the energy landscape of protein folding: a synthesis. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 21, 167–195. ( 10.1002/prot.340210302) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buhot A, Halperin A. 2002. Extension behavior of helicogenic polypeptides. Macromolecules 35, 3238–3252. ( 10.1021/ma011631w) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carrion-Vazquez M, Oberhauser AF, Fowler SB, Marszalek PE, Broedel SE, Clarke J, Fernandez JM. 1999. Mechanical and chemical unfolding of a single protein: a comparison. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3694–3699. ( 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3694) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marko JF, Siggia ED. 1995. Stretching DNA. Macromolecules 28, 8759–8770. ( 10.1021/ma00130a008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang B, Evans JS. 2001. Modeling AFM-induced PEVK extension and the reversible unfolding of Ig/FNIII domains in single and multiple titin molecules. Biophys. J. 80, 597–605. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76040-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dobrynin AV, Carrillo JY. 2011. Universality in nonlinear elasticity of biological and polymeric networks and gels. Macromolecules 44, 140–146. ( 10.1021/ma102154u) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Griffith AA. 1921. The phenomena of rupture and flow in solids. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 221, 163–198. ( 10.1098/rsta.1921.0006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rief M, Grubmüller H. 2002. Force spectroscopy of single biomolecules. ChemPhysChem 3, 255–261. ( 10.1002/1439-7641) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fisher TE, Oberhauser AF, Carrion-Vazquez M, Marszalek PE, Fernandez JM. 1999. The study of protein mechanics with the atomic force microscope. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 379–384. ( 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01453-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lv S, Dudek DM, Cao Y, Balamurali MM, Gosline J, Li H. 2010. Designed biomaterials to mimic the mechanical properties of muscles. Nature 465, 69–73. ( 10.1038/nature09024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brockwell DJ, Paci E, Zinober RC, Beddard GS, Olmsted PD, Smith DA, Perham RN, Radford SE. 1997. Pulling geometry defines the mechanical resistance of a beta-sheet protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 731–737. ( 10.1038/nsb968) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li H, Linke WA, Oberhauser AF, Carrion-Vazquez M, Kerkvliet JG, Lu H, Marszalek PE, Fernandez JM. 2002. Reverse engineering of the giant muscle protein titin. Nature 418, 998–1002. ( 10.1038/nature00938) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dietz H, Berkemeier F, Bertz M, Rief M. 2006. Anisotropic deformation response of single protein molecules. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12 724–12 728. ( 10.1073/pnas.0602995103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Linkea WA, Kulkea M, Lib H, Fujita-Beckerc S, Neagoea C, Mansteinc DJ, Gauteld M, Fernandez JM. 2002. PEVK domain of titin: an entropic spring with actin-binding properties. J. Struct. Biol. 137, 194–205. ( 10.1006/jsbi.2002.4468) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oberhauser AF, Marszalek PR, Erickson HP, Fernandez JM. 1998. The molecular elasticity of the extracellular matrix protein tenascin. Nature 393, 181–185. ( 10.1038/30270) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee EH, Hsin J, Mayans O, Shulten K. 2007. Secondary and tertiary structure elasticity of titin z1z2 and a titin chain model. Biophys. J. 93, 1719–1735. ( 10.1529/biophysj.107.105528) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.D'ambrosio D, De Tommasi D, Ferri D, Puglisi G. 2008. A phenomenological model for healing and hysteresis in rubber-like materials. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 46, 293–305. ( 10.1016/j.ijengsci.2007.12.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.DeSimone A, Marigo JJ, Teresi L. 2001. A damage mechanics approach to stress softening and its application to rubber. Eur. J. Mech. A Solids 20, 873–892. ( 10.1016/S0997-7538(01)01171-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dorfmann A, Ogden RW. 2003. A pseudo-elastic model for loading, partial unloading and reloading of particle-reinforced rubber. Int. J. Solids Struct. 40, 2699–2714. ( 10.1016/S0020-7683(03)00089-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]