Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Presacral ganglioneuromas are rare, usually benign lesions. Patients typically present when the mass is very large and becomes symptomatic.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

This report describes the case of a 42 year old lady presenting with back pain who was subsequently diagnosed with a presacral ganglioneuroma based on MR imaging and a CT guided biopsy of the lesion.

DISCUSSION

After counselling regarding nonoperative management, the patient opted for surgical resection. Open resection was performed with preservation of the neurovascular pelvic anatomy and an uneventful postoperative recovery. A review of the relevant literature was also performed using a search strategy in the online literature databases PUBMED and EMBASE.

CONCLUSION

Surgical resection of a presacral ganglioneuroma is reasonable given their propensity for local effects and reported potential malignant transformation.

Keywords: Ganglioneuroma, Presacral, Resection

1. Introduction

Ganglioneuromas are rare tumours in the neuroblastoma group.1–4 They are benign lesions arising from sympathetic ganglion cells and complete surgical resection is considered to be curative.1–3 They are rarely located in the presacral space, with 17 cases reported previously in the presacral area.4 As imaging techniques have become more widely performed, the number of ganglioneuromas found incidentally has increased.5 However, it can be difficult to diagnose this lesion precisely as ganglioneuroma preoperatively.3 The authors report their experience with a case of presacral ganglioneuroma.

2. Case report

A primary extra adrenal ganglioneuroma was discovered incidentally in a healthy 42 year lady during the course of investigations for a six month history of lower back pain. She had no significant past medical history other than a previous caesarean section. Clinical examination was unremarkable. Investigative MRI of her lumbosacral spine revealed an enhancing retroperitoneal tumour lying anterior to the sacrum and lumbosacral junction (Figs. 1 and 2).

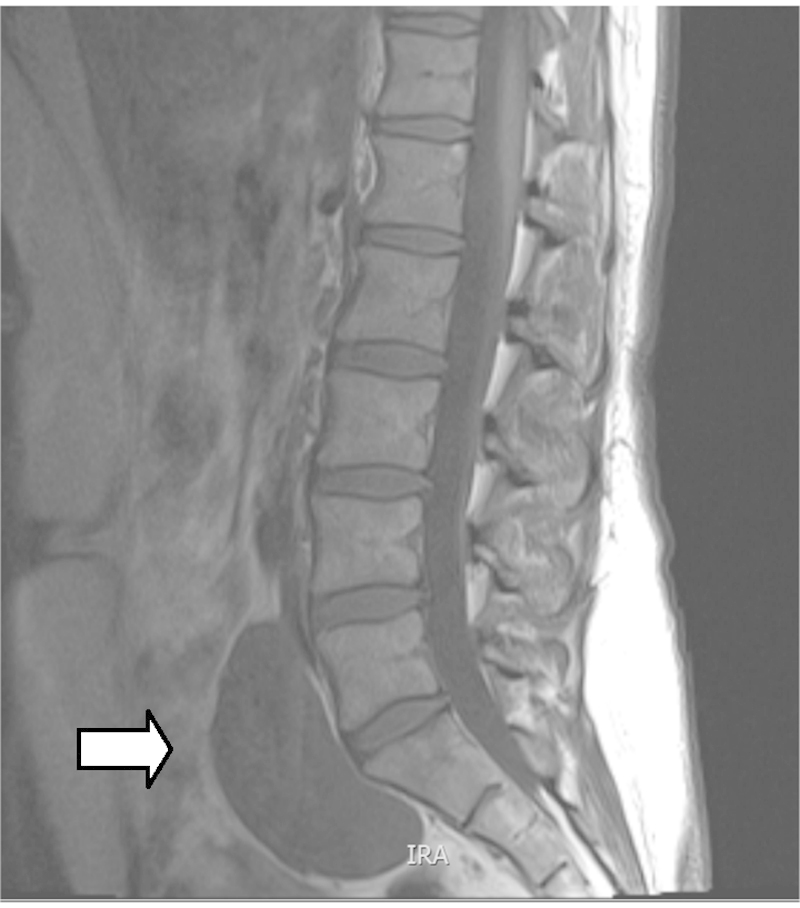

Fig. 1.

MR T1 weighted image of tumour indicated by white arrow.

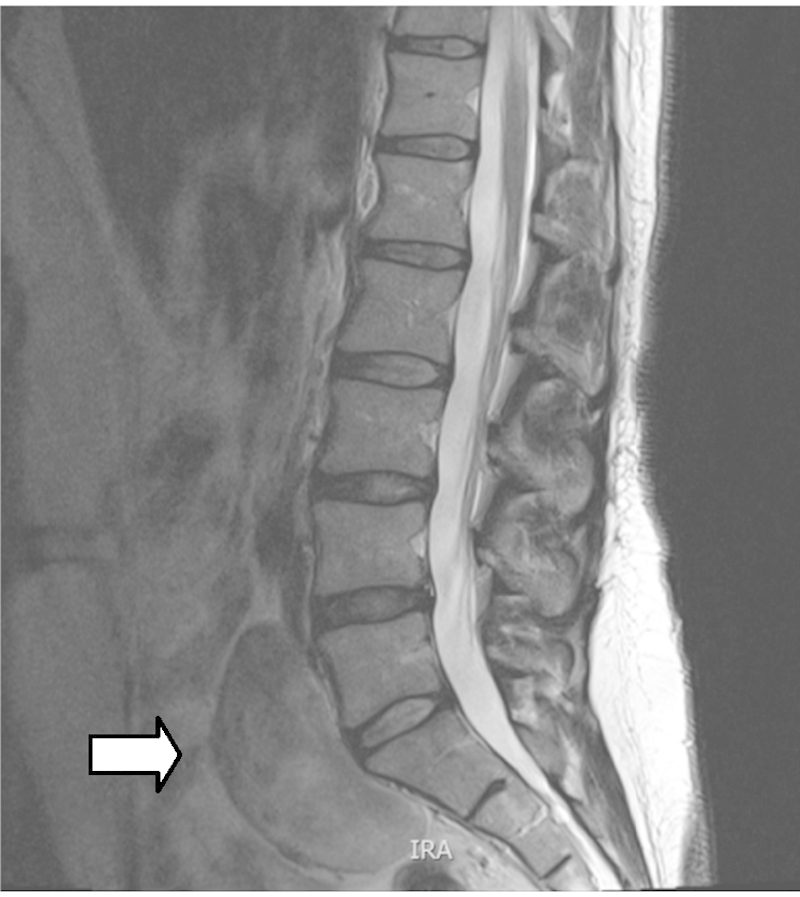

Fig. 2.

MR T2 weighted image of tumour indicated by white arrow.

She subsequently underwent a CT guided biopsy of the lesion. Frozen section at the time of the biopsy suggested a possible schwannoma. Further microscopic examination of the biopsy sections showed connective tissue skeletal muscle and a fragment of tissue composed of spindle cells in elongated, wavy, hyperchromatic nuclei which were mildly pleomorphic. Larger ganglion cells were also noted. Immunohistochemistry using antibodies to S100 protein showed patchy weak immunoreactivity. No proliferative activity was demonstrated by MIB-1 labelling using Ki-67. The neuropathologist concluded that the biopsy was insufficient for definitive diagnosis but taken in the context of the imaging, it suggested ganglioneuroma. No mitoses were seen. A repeat MRI performed three months later revealed no interval changes. Following discussion at a multidisciplinary meeting and consultation with the patient it was decided to proceed with resection of the lesion.

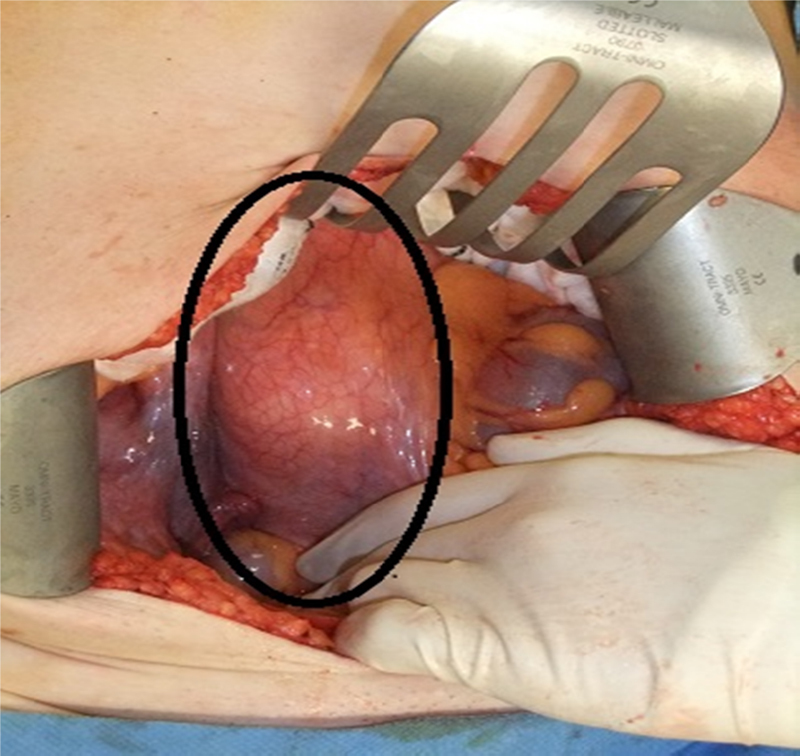

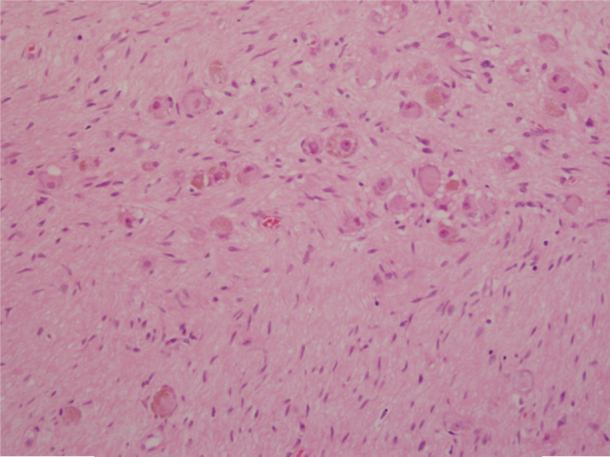

The tumour was exposed via an anterior intraperitoneal approach. A well circumscribed mobile tumour in the retroperitoneum at the aortic bifurcation grossly measuring 12 cm × 6 cm × 8 cm was noted (Fig. 3). It extended from the L4 vertebrae over the sacral promontory to S2. The tumour was noted to be adherent to the left common iliac vein. The retroperitoneum was opened directly over the tumour and the tumour was mobilised with diathermy using Ligaclips to the vessels supplying it. It easily peeled off the left common iliac vein and retroperitoneum. The tumour was completely excised macroscopically with no residual tumour evident (Fig. 4). The retroperitoneal defect was closed prior to routine abdominal closure. The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative recovery and was discharged home six days following surgery free of her back pain. Subsequent pathology reports indicated complete excision of a benign ganglioneuroma with no evidence of neuroblastoma (Fig. 5) At 2 month clinical follow up the patient was symptom free. Further clinical follow up in one year with abdominal computed tomography scan to exclude any radiological recurrence is planned.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative image shows tumour underlying retroperitoneum outlined in a black ellipse.

Fig. 4.

Resected specimen.

Fig. 5.

Photomicrograph showing large ganglion cells embedded in neuromatous stroma.

3. Discussion

Ganglioneuromas are benign slow-growing lesions that arise from sympathetic ganglion cells. Histologically ganglioneuromas are considered to be part of the neuroblastoma group together with neuroblastomas and ganglioneuroblastomas.1–5 Ganglioneuromas can arise anywhere along the sympathetic chain. Common locations include the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, and adrenal gland.6,7 The presacral location is rare, with only 17 previously reported cases.4 Stout et al. 8 reviewed a series of 234 ganglioneuromas located in multiple areas and reported that they are more common in females and that 60% of patients were younger than 20 years of age at the time of diagnosis.

Ganglioneuromas are commonly asymptomatic, but patients can present with symptoms associated with local mass effect such as back pain, constipation or even bowel obstruction.9,10 Of the 17 reported cases of presacral ganglioneuroma in the literature, six were found incidentally, seven presented with pain, five with constipation and one with amenorrhoea.4 All patients underwent surgical resection with only two undergoing retroperitoneal exposure.

Ganglioneuromas can be difficult to diagnose preoperatively. Modha et al.3 describe in their case series that no patient was diagnosed with ganglioneuroma preoperatively, despite imaging studies in all cases and FNAC in three out of five cases. Two cases were felt to be fibroid tumours based on initial CT findings. The third case had a preliminary diagnosis of chondroma and their fourth and fifth cases, a preliminary diagnosis of schwannoma. Jain et al.11 stressed in their report that FNAC samples of the ganglioneuromas be obtained at multiple sites within the tumour to improve diagnostic accuracy. Structural and morphological features of ganglioneuromas, such as the presence of mature sympathetic ganglion cells, can help distinguish them from other pelvic or abdominal lesions such as schwannoma, neurofibroma, meningoma or cystic lesions, however to date, there have been only three case reports of a confident diagnosis of ganglioneuroma based on the cytologic features alone.11

MRI is considered the radiological investigation of choice.3 MRI projects ganglioneuroma as a homogeneous mass with signal intensity less than that of liver on T1-weighted MRI (Fig. 1) and as a heterogeneous mass with predominant signal intensity greater than that of liver on T2-weighted MRI (Fig. 2).3 MR imaging can help distinguish lesions of spinal origin from those of pelvic origin, aiding treatment planning.3

In our case the anterior intraperitoneal approach gave excellent access to the lesion and facilitated its full excision. Other approaches reported in the literature include successful use of the posterior transsacral approach. This was indicated due to the involvement of sacral nerve roots. However in one case series of 5 patients3, the authors performed a partial resection of the tumour via an anterior approach and preferred returning in a staged fashion later to perform a laminectomy and foramenectomy to treat intractable radicular symptoms.

Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy is not indicated due to the benign nature of this disease. In the case of complete resection there are no clear follow up protocols in place. Cerullo et al.4 suggest yearly clinical examination and MR imaging to ensure no local recurrence. Modha et al.3 suggest intensive follow up for a year to ensure no evidence of local recurrence. Interestingly, no adult case has been described where a recurrence has actually occurred however Drago et al.12 did describe the spontaneous development of an malignant nerve sheath tumour in a benign ganglioneuroma in a 11 year old girl.

4. Conclusion

Presacral ganglioneuromas are rare, benign lesions. Patients typically present when the mass is very large and symptomatic. Surgery is the primary means of diagnosis and treatment. MR imaging is the preferred imaging modality to assess its characteristics and help plan the surgical procedure. An anterior approach to the tumour allows safe and adequate resection. Optimal follow up is unclear.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Funding

None.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

Noel Lynch: Study design, writing. Peter Neary: Writing and editing. Emmet Andrews: Editing. John Fitzgibbon: Editing, image retrieval.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Leeson M.C., Hite M. Ganglioneuroma of the sacrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(246):102–105. [Epub 1989/09/01] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmor E., Fourney D.R., Rhines L.D., Skibber J.M., Fuller G.N., Gokaslan Z.L. Sacrococcygeal ganglioneuroma. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15(3):265–268. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200206000-00018. [Epub 2002/07/20] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modha A., Paty P., Bilsky M.H. Presacral ganglioneuromas. Report of five cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2(3):366–371. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.3.0366. [Epub 2005/03/31] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerullo G., Marrelli D., Rampone B., Miracco C., Caruso S., di Martino M. Presacral ganglioneuroma: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(14):2129–2131. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i14.2129. [Epub 2007/05/01] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamaguchi K., Hara I., Takeda M., Tanaka K., Yamada Y., Fujisawa M. Two cases of ganglioneuroma. Urology. 2006;67(3):622 e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.09.024. [Epub 2006/03/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen H.J., Hansen L.G., Lange P., Teglbjaerg P.S. Presacral ganglioneuroma. Case report. Acta Chir Scand. 1986;152:777–778. [Epub 1986/12/01] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghali V.S., Gold J.E., Vincent R.A., Cosgrove J.M. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor arising spontaneously from retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma: a case report, review of the literature, and immunohistochemical study. Human Pathol. 1992;23(1):72–75. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90015-u. [Epub 1992/01/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stout A.P. Ganglioneuroma of the sympathetic nervous system. Surgery, Gynecol Obstet. 1947;84(1):101–110. [Epub 1947/01/01] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes F.A., Green A.A., Rao B.N. Clinical manifestations of ganglioneuroma. Cancer. 1989;63(6):1211–1214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890315)63:6<1211::aid-cncr2820630628>3.0.co;2-1. [Epub 1989/03/15] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cronin E.M., Coffey J.C., Herlihy D., Romics L., Aftab F., Keohane C. Massive retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma presenting with small bowel obstruction 18 years following initial diagnosis. Irish J Med Sci. 2005;174(2):63–66. doi: 10.1007/BF03169133. [Epub 2005/08/13] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain M., Shubha B.S., Sethi S., Banga V., Bagga D. Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma: report of a case diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology, with review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21(3):194–196. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199909)21:3<194::aid-dc9>3.0.co;2-b. [Epub 1999/08/18] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drago G., Pasquier B., Pasquier D., Pinel N., Rouault-Plantaz V., Dyon J.F. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor arising in a “de novo” ganglioneuroma: a case report and review of the literature. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28(3):216–222. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199703)28:3<216::aid-mpo13>3.0.co;2-c. [Epub 1997/03/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]