Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Herein we present an extremely rare case of a giant extra gastrointestinal stromal tumor (EGIST) of the lesser omentum obscuring the diagnosis of a choloperitoneum.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 79 years old female was admitted to our hospital with symptoms of vomiting and epigastric pain. Abdominal computer tomography revealed a sizable formation that was diagnosed as a tumor of the pancreas. In laparotomy, a choloperitoneum was diagnosed as the cause of patient's symptoms. A tumor adherent firmly to the lesser curvature of stomach was also discovered. Cholecystectomy and subtotal gastrectomy were performed. Histologically, the tumor was diagnosed as a EGIST of the lesser omentum. The patient did not receive any adjuvant therapy and after two years of follow up she is without any recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Omental EGISTs may remain clinically silent despite the large tumor's size. It is difficult to differentiate a EGIST in the lesser omentum from a GIST of the lesser curvature of the stomach, despite the use of advanced radiological imaging techniques. Our case of a giant EGIST of lesser omentum obscuring the diagnosis of acute choloperitoneum is the only one reported in literature.

CONCLUSION

EGISTs that arise from the omentum are very rare and complete surgical resection is the only effective treatment approach. Adjuvant therapy following resection of localized disease has become standard of care in high risk cases.

Keywords: EGIST, Lesser omentum, Choloperitoneum, Gastrectomy

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract, accounting for 0.1–3% of all gastrointestinal malignancies.1 These tumors are typically discovered in symptomatic patients (e.g., gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal pain) or incidentally in asymptomatic patients (e.g., diagnostic tests, during abdominal surgery, present in surgical specimens). They are characterized by the expression of KIT (CD117) a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor for stem cell factor.2 GISTs are rarely found as primary tumors in extragastrointestinal intra-abdominal tissues such as the omentum, the mesentery and the retroperitoneum (EGISTs).3 The origin of EGISTs is uncertain, but their histological appearance and immunophenotype are identical to the classic GISTs.4 Our knowledge about EGISTs is based on accumulated data from individual case reports. In this paper, we describe a rear case of EGIST of lesser omentum, that confused us of making diagnosis of a choloperitoneum.

2. Presentation of case

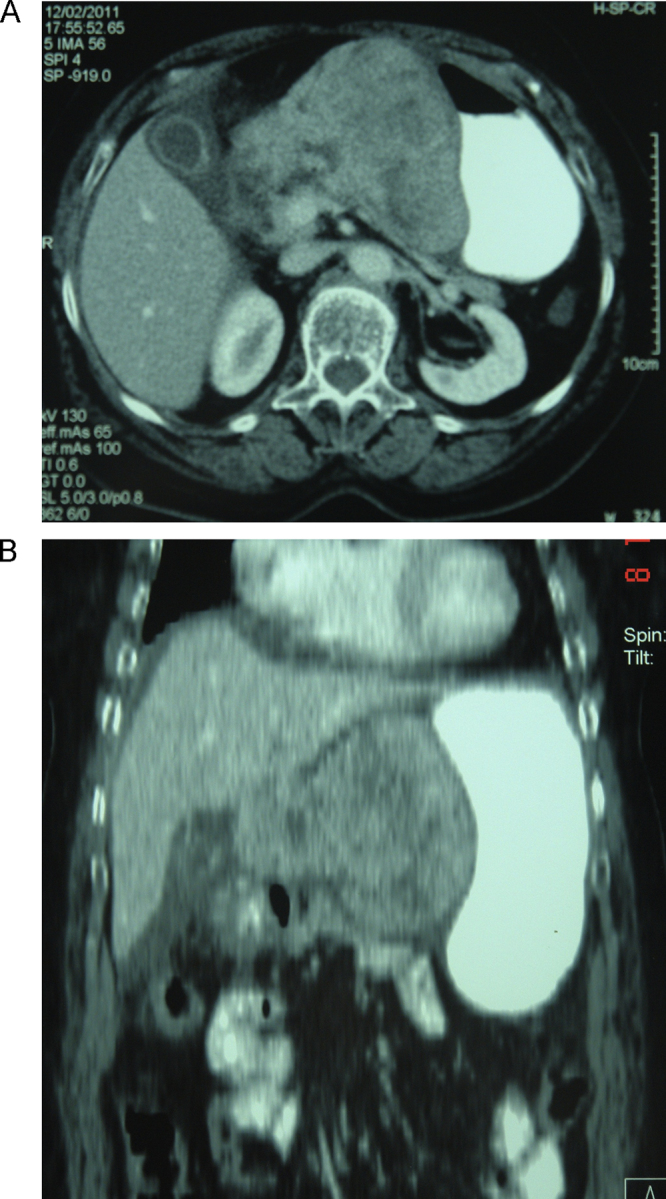

A 79 years old female, was admitted to the emergency clinic with symptoms of vomiting and epigastric pain during the last 24 h. Her medical history included atrial fibrillation as well as respiratory failure. Physical examination revealed painful epigastric distension. Laboratory tests revealed Hb: 12.1 g/dL, Hct 36.2%, WBC: 8000/mm3, gran: 71.5%, lymph: 18.2% and serum levels of glucose: 147 mg/dL, urea: 39 mg/dL, creatinine: 0.90 mg/dL, T.bil: 0.50 mg/dL, D.bil: 0.19 mg/dL, SGOT: 18 IU/L, SGPT: 15 IU/L, γ-GT: 19 IU/L, amylase: 89 IU/L, lipase: 52 IU/L. Abdominal X-ray examination was normal. Axial CECT demonstrated a large lobulated mass measuring 10.77 × 9.67 cm between the lesser curvature of the stomach and the body of pancreas. The mass demonstrated post-contrast heterogeneous enhancement with large necrotic areas. It was diagnosed as a tumor of the pancreas. There were radiologic features of acute cholecystitis, while the liver parenchyma appeared to be normal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(A and B) Abdominal computer tomography scan demonstrating a sizable formation contiguous with the stomach and the pancreas.

A nasogastric tube was inserted and parenteral fluid therapy was administered. During the following 48 h the patient deteriorated clinically with signs of acute abdomen comprising of epigastric pain radiating to the rest of the abdomen and generalized guarding of the anterior abdominal muscles. There was also deterioration of the hematology and biochemistry indices (Hct: 39%, WBC: 17,040/mm3, gran: 81.5%, lymph: 5.8%, urea: 46 mg/dL, creatinine: 1.70 mg/dL). Abdominal ultrasound examination revealed free fluid in all abdominal quadrants.

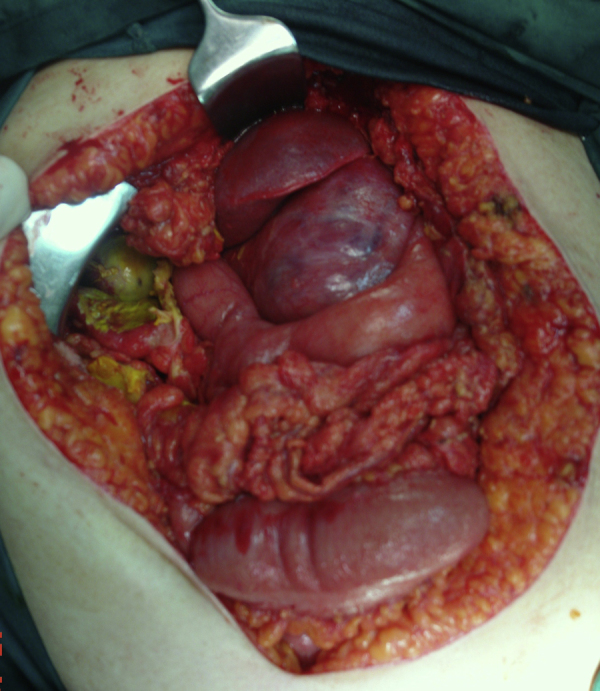

After that, under general anesthesia, the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy by midline incision. The peritoneal cavity was full of bilious liquid and bile-colored pseudomembranes. There was thickening of the gallbladder wall with focal necroses. There was also a sizable mass with a diameter of about 10 cm, firmly adherent to the lesser curvature of stomach and the pancreas. The tumor was in contact with the left gastric artery (Fig. 2). Cholecystectomy was performed along with lavage of the peritoneal cavity. Dissection of the tumor from the stomach was deemed unfeasible since there were no identifiable tumor margins on the stomach wall. Therefore we proceeded with resection of the tumor en-block with the adjacent part of the stomach (subtotal gastrectomy) and resection of the lesser omentum. The gastrointestinal continuity was restored with a Bilroth II procedure (Fig. 3). The patient, because of her respiratory problems, was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit and was connected to the ventilator.

Fig. 2.

Surgical field: choloperitoneum, focal necroses of the gallbladder and a sizable formation adherent firmly to the lesser curvature of the stomach.

Fig. 3.

Surgical specimen of cholecystectomy and subtotal gastrectomy.

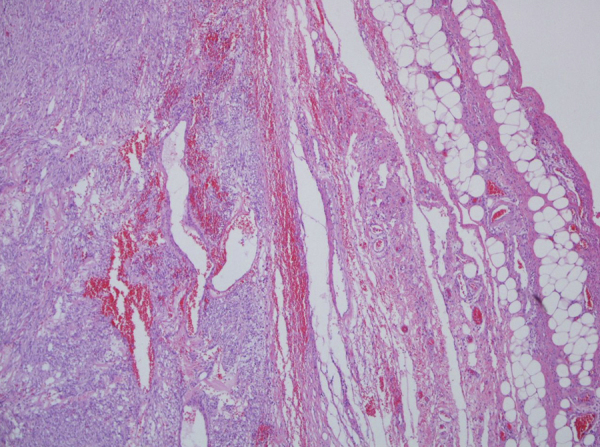

The tumor was well circumscribed in the lesser omentum (Fig. 4), measuring 11 cm × 9 cm × 9 cm. There was no infiltration to stomach. The cut surface appear reddish-gray, solid. The histological features characterized by fascicles of spindle cells with monotonous and uniform nuclei, without atypia. There were foci of tumor cell necrosis. Mitotic activity was 7/50 HRF. Immunohistochemically the tumor cells were diffusely positive for c-kit (CD117), CD34 and slightly positive for SMA but negative for DESMINE and S-100 proteine. The MIB-1 index was <5%. The gallbladder was measured 7 cm in length and 3 cm in width and was full of multiple small stones and the histopathology revealed intense inflammation and focal wall necroses of its wall.

Fig. 4.

EGIST arising in lesser omentum with a pushing margin extending to the fat.

Recovery was prolonged because of the patient's respiratory failure; she was disconnected from the ventilator on the 11th postoperative day and she was discharged on 20th postoperative day. The patient did not receive any additional adjuvant treatment, according to the attending oncologist and after two years of follow up she is without any recurrence.

3. Discussion

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract, accounting for 0.1–3% of all gastrointestinal malignancies. They are currently believed to originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) or their precursors in the gastrointestinal tract.2 Cajal cells are the only ones along the GI tract that exhibit the CD117+/CD34+ immunophenotype, which is the diagnostic hallmark of GIST.5 The molecular pathogenesis of GISTs is usually driven by activating mutations of the KIT gene that encodes the CD117 oncoprotein. Typically they are characterized by the expression of KIT (CD 117), a transmembrane tyrosine kinase reseptor for stem cells factor, in 90% of cases, although in some cases CD117 may be negative.6 CD34 strongly and diffuse stains approximately 70% of GISTs. GISTs may show smooth muscle actine positivity but are negative for desmin and S-100 protein.3

GISTs can occur anywhere interstitial cells of Cajal are present along the gastrointestinal tract, including the stomach (60%), small intestine (30%), duodenum (5%), colorectum (4%) and esophagus.7 GISTs originating from extragastrointestinal intra-abdominal tissues (EGISTs) are located in the omentum and mesentery in 80% of cases. EGISTs were also reported in pleura, pancreas and abdominal wall8 Lesser omental EGISTs are particularly rare and only seven cases have been previously reported.9

The origin of EGISTs is uncertain but, as a rule, there is a strong analogy between GISTs and EGISTs from histological aspect. EGISTs in the lesser omentum may theoretically arise from CD117+/CD34+ mesenchymal cells, like Cajal cells in the normal omentum.10

The clinical presentation of GISTs is erratic. About 70% of patients are symptomatic and GISTs are associated with a broad range of presentations, including bleeding, perforation and most commonly obstruction.10,11 However, approximately 30% of cases are asymptomatic and they are diagnosed as incidental findings during endoscopy, surgery, radiologic studies for other reasons or at autopsy.12 There are no physical findings specific to GISTs. The most frequent non-specific presenting complaint is of an abdominal mass. Omental EGISTs may remain clinically silent despite the large tumor size13 as in our case.

Contrast-enhanced Computer Tomography is the imaging test of choice for detecting, staging, surgical planning and monitoring of patients with GISTs.14 The EGISTs of lesser omentum occur as large, well-circumscribed, post-contrast heterogeneously enhanced tumors with areas of necrosis and hemorrhage, as in our case.

It is difficult to differentiate an EGIST in the lesser omentum from a GIST of the lesser curvature of the stomach, despite the use of advanced radiological imaging techniques such as CT or abdominal ultrasound. About half of omental EGISTs are misdiagnosed as extra mucosal tumors of the stomach.15 In our case, the CT images suggested a huge tumor most likely originating from the pancreas. Our patient's symptomatology of acute abdomen was though to be due to rupture of the tumor. It was under these circumstances that we decided to perform an exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperatively the origin of the tumor could not be macroscopically determined since it was firmly adherent to the lesser curvature of the stomach. Complete tumor resection was achieved by performing a distal subtotal gastrectomy with Bilroth II reconstruction.

There is a general agreement that tumor's size and mitotic count are the most important prognostic factors in GISTs.16 Malignancy characteristics of GISTs on CT are diameter greater than 5 cm, irregular surface, indeterminate limits, tissue infiltration, heterogeneous contrast enhancement, hepatic metastasis and peritoneal dispersion. The lymph node swelling is not a factor associated with malignant GIST and rarely they manifest ascites. A high mitotic rate (>5/50HRF), the high cellularity and necrosis show a possible aggressive clinical course of EGISTs, while the existence of two or more of these three factors have a poor prognosis. The size criterion is not as important for the prognosis of EGISTs as it is for GISTs.4

Surgical resection remains the treatment of choice for localized GISTs. All incidental GISTs in the published reports were determined to have low or very low risk of malignant potential. Imatinib mesylate, which is an inhibitor of a family of structurally related tyrosine kinase signaling enzymes, and sunitinibe, which is a multi kinase inhibitor, are currently the most effective adjuvant therapy for GISTs pro or postoperatively,17 while a careful follow-up is needed to rule out late recurrence or metastasis.

4. Conclusion

EGISTs that arise from the omentum are very rare and complete surgical resection is the only effective treatment approach. Adjuvant therapy following resection of localized disease has become standard of care in high risk cases.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Authors’ contributions

The study was designed by Ioannis K Skandalos. Data collections were done by Ioannis K Skandalos, Nikolaos F Hotzoglou, Kyriaki Ch Matsi, Xanthi A Pitta and Athanasios I Kamas. Data analysis was done by Nikolaos F Hotzoglou, Xanthi A Pitta and Athanasios I Kamas. The manuscript was written by Ioannis K Skandalos, Nikolaos F Hotzoglou, Kyriaki Ch Matsi, Xanthi A Pitta and Athanasios I Kamas.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Liegl-Atzwanger B., Fletcher J.A., Fletcher C.D. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Virchows Archiv. 2010;456:111–127. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-0891-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirota S., Isozaki K., Moriyama Y., Hashimoto K., Nishida T., Ishiguro S. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279:577–580. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miettinen M., Monihan J.M., Sarlomo-Rikala M., Kovatich A.J., Carr N.J., Emory T.S. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary in the omentum and mesentery: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1999;23:1109–1118. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto H., Oda Y., Kawaguchi K., Nakamura N., Takahira T., Tamiya S. c-kit and PDGFRA mutations in extragastrointestinal stromal tumor (gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the soft tissue) American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2004;28:479–488. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirota S., Nishida T., Isozaki K., Taniguchi M., Nakamura J., Okazaki T. Gain-of-function mutation at the extracellular domain of KIT in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Journal of Pathology. 2001;193:505–510. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH818>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medeiros F., Corless C.L., Duensing A., Hornick J.L., Oliveira A.M., Heinrich M.C. KIT-negative gastrointestinal stromal tumors: proof of concept and therapeutic implications. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2004;28:889–894. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miettinen M., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 2006;130:1466–1478. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1466-GSTROM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkhatib L., Albtoush O., Bataineh N., Gharaibeh K., Matalka I., Tokuda Y. Extragastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (EGIST) in the abdominal wall: case report and literature review. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 2011;2:253–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogawa H., Gotoh K., Yamada T., Takahashi H., Ohigashi H., Nagata S. A case of KIT-negative extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the lesser omentum. Case Reports in Gastroenterology. 2012;6:375–380. doi: 10.1159/000337908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakurai S., Hishima T., Takazawa Y., Sano T., Nakajima T., Saito K. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors and KIT-positive mesenchymal cells in the omentum. Pathology International. 2001;51:524–531. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2001.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sepe P.S., Brugge W.R. A guide for the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal cell tumors. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2009;6:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson B., Bümming P., Meis-Kindblom J.M., Odén A., Dortok A., Gustavsson B. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era – a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103:821–829. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akahoshi K., Sumida Y., Matsui N., Oya M., Akinaga R., Kubokawa M. Preoperative diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;13(April):2077–2082. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i14.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoch G., Herrmann K., Heusner T.A., Buck A.K. Imaging procedures for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Radiologe. 2009;49:1109–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00117-009-1852-9. [article in German] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuda H., Suwa T., Kimura F., Sugiura T., Shinoda T., Kaneko K. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the lesser omentum: report of a case. Surgery Today. 2001;31:715–718. doi: 10.1007/s005950170077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutkowski P., Bylina E., Wozniak A., Nowecki Z.I., Osuch C., Matlok M. Validation of the Joensuu risk criteria for primary resectable gastrointestinal stromal tumour – the impact of tumour rupture on patient outcomes. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2011;37:890–896. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demetri G.D., Heinrich M.C., Fletcher J.A., Fletcher C.D., Van den Abbeele A.D., Corless C.L. Molecular target modulation, imaging, and clinical evaluation of gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients treated with sunitinib malate after imatinib failure. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15:5902–5909. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]