Abstract

INTRODUCTION

An obturator hernia is a rare condition but is associated with the highest mortality of all abdominal wall hernias. Early surgical intervention is often hindered by clinical and radiological diagnostic difficulty. The following case report highlights these diagnostic difficulties, and reviews the current literature on management of such cases.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We present the case of an 86-year-old lady who presented with intermittent small bowel obstruction, clear hernial orifices, and right medial thigh pain. Pre-operative CT imaging was suggestive of an obstructed right femoral hernia. However, intra-operatively the femoral canal was clear and an obstructed hernia was found passing through the obturator foramen lying between the pectineus and obturator muscles in the obturator canal.

DISCUSSION

Obturator hernias are notorious for diagnostic difficulty. Patients often present with intermittent bowel obstruction symptoms due to a high proportion exhibiting Richter's herniation of the bowel. Hernial sacs can irritate the obturator nerve within the canal, manifesting as medial thigh pain, and often no hernial masses can be detected on clinical examination. Increasing speed of diagnosis through early CT imaging has been shown to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with obturator hernias. However, over-reliance on CT findings should be cautioned, as imaging and operative findings may not always correlate.

CONCLUSION

A high suspicion for obturator hernia should be maintained when assessing a patient presenting with bowel obstruction particularly where intermittent symptoms or medial thigh pain are present. Rapid clinical and appropriate radiological assessment, followed by early surgery is critical to successful treatment.

Keywords: Obturator, Hernia

1. Introduction

Most external abdominal hernias are found in the inguinal region as either inguinal or femoral hernias. However, much more infrequently, patients will present with problems attributed to more rare forms of hernias, such as obturator hernias. Obturator hernias account for 0.07–1% of all hernias and 0.2–1.6% of all cases of mechanical obstruction of the small bowel.1 They have the highest mortality rate of all abdominal wall hernias at between 13% and 40%.2

Signs and symptoms resulting from obturator hernias are often vague and non-specific. There is rarely a palpable mass as in other common abdominal wall hernias and diagnostic imaging can often be inconclusive. The combination of diagnostic difficulty and high mortality rates make obturator hernias a serious diagnosis that can potentially be easily overlooked.

I present an interesting case of an elderly woman who presented with bowel obstruction secondary to an obstructed, incarcerated obturator hernia.

2. Presentation of case

An 86-year-old thin, frail lady was admitted with a 9 day history of nausea, vomiting, constipation, and lower right quadrant abdominal pain that radiated down the right medial thigh. On examination her abdomen was soft, mildly distended, with tenderness on palpation of the right iliac fossa, but clinically she exhibited no masses and had clear hernial orifices.

An abdominal X-ray (Fig. 1) revealed dilated loops of small bowel with little gas passing to the large bowel. A CT scan was undertaken to further investigate the cause of her dilated bowel loops. This revealed markedly dilated small bowel extending into the pelvis where a suspicion was raised regarding the possibility of a femoral hernia causing the small bowel obstruction.

Fig. 1.

Plain abdominal X-ray showing small bowel obstruction.

The patient was taken to theatre for surgical exploration. A transverse incision just superior to the right inguinal region was utilised. The transverse fascia was opened and dissection performed inferiorly to the femoral canal. No hernia was identified.

Blunt dissection was performed retroperitoneally revealing a projection of peritoneum passing inferiorly behind the superior pubic ramus along with the obturator artery and nerve. A diagnosis of an incarcerated obstructed obturator hernia was made.

The hernial sac was very oedematous and stuck within the obturator canal. To minimise injury risk to the bowel, the peritoneum was opened and with gentle traction applied to the bowel, the hernia was successfully reduced. The bowel wall showed no signs of ischaemia and therefore no resection was performed. The rest of the bowel was examined which revealed no abnormality.

The hernial sac was then inverted and excised after ligating its neck with 2-0 Vicryl™. The defect was repaired with a 6 cm × 8 cm Ethicon Prolene™ mesh. This was shaped appropriately and inset by suturing with 2-0 prolene to the pectineal ligament and the fascia overlying the pubic symphysis. The peritoneum, transversalis fascia, and aponeurosis were then closed using 2-0 Vicryl™.

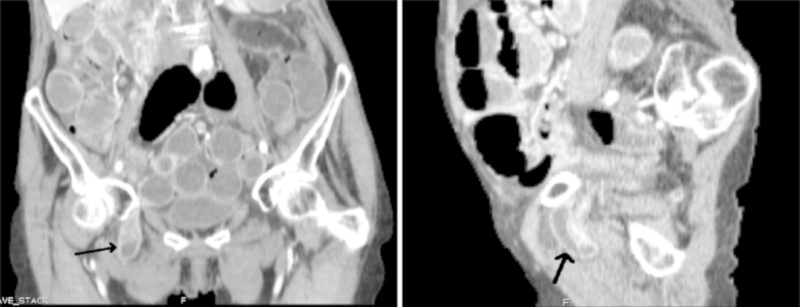

Post-operatively the multi-disciplinary team reviewed the CT images in light of the operative findings. It was concluded that the high axial slices had been deceptive and that an obturator hernia had been demonstrated passing in front of obturator externus and beneath pectineus in the obturator canal (Figs. 2 and 3). The patient had an uneventful post-operative period and was discharged on the 5th post-operative day. At a clinic review 6 weeks later, the patient exhibited no pain and no masses and was discharged.

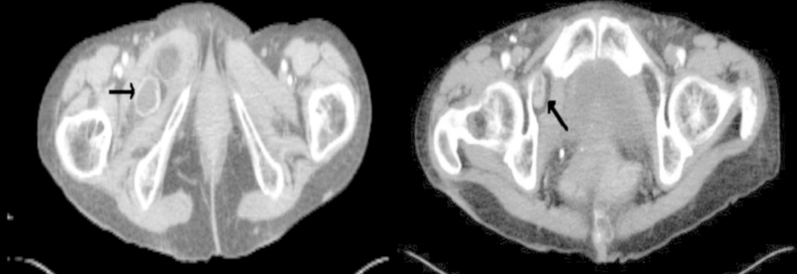

Fig. 2.

Low and high axial CT pelvic images showing the small bowel loop descending into the right obturator canal anterior to the oburator externus muscle.

Fig. 3.

Coronal and Saggital CT pelvic images showing the small bowel loop descending into the right obturator canal.

3. Discussion

Arnaud de Ronsil first described the obturator hernia in 1724 and Obre performed the first successful operation in 1851.3 It is a rare condition with only 541 cases having been reported in the literature by 1980.4

It occurs through the obturator canal, which is approximately 2–3 cm long and 1 cm wide. Obturator hernias are much more common in elderly female and post-pregnancy patients owing to the greater width of the pelvis, larger obturator canal, and increased laxity of the pelvic tissues.2 The condition has been nicknamed the ‘little old ladies hernia’ as it affects this group due to atrophy and loss of the pre-peritoneal fat around the obturator vessels in the canal predisposing hernia formation.

The symptoms are vague and are usually in the form of nausea and vomiting or other signs of bowel obstruction such as abdominal pain and a lack of bowel movement. The literature has shown that up to 80% of patients with obturator hernias usually have symptoms of bowel obstruction, which is often partial due to a high proportion exhibiting Richter's herniation of the bowel into the obturator canal.1 This tends to give rise to a clinical picture of intermittent bowel obstruction symptoms, which is an important factor to identify in the clinical history if accurate diagnosis is to be made. Obturator hernia sacs often compress or irritate the obturator nerve running in the canal, giving rise to medial thigh pain such as the type exhibited in my case. This is known as the Howship–Rhomberg Sign and has been shown to be present in 15–50% of obturator hernia cases.1

Recent literature has shown that early diagnosis of obturator hernia can be made with CT of the abdomen and pelvis.6,7 However, an emphasis is also placed on the dangers of over-reliance on such imaging. Our case demonstrates that radiological and operative findings may not always correlate, and that only intra-operatively can a truly accurate diagnosis be made. Despite this, the consensus from current published evidence is that CT of the pelvis and upper thigh is the most useful imaging tool when an obturator hernia is suspected clinically. CT imaging of bowel herniating through the obturator foramen and lying between the pectineus and obturator muscles is shown to be the best diagnostic clue.5 This is demonstrated clearly by the low axial CT image in Fig. 2.

Various surgical approaches have been described in the literature in the acute management of an obturator hernia. Abdominal, inguinal, retropubic, obturator, and laparoscopic approaches have all been described. The majority of published evidence favours the abdominal approach, utilising a low midline incision. This method allows the surgeon to establish the diagnosis, avoid any obturator vessels, give better exposure of the obturator ring, and facilitate bowel resection if necessary.1 Simple closure of the hernial defect with interrupted sutures or placement of a synthetic mesh are the preferred methods of herniorrhaphy as they are associated with the lowest complication rates.1

In my case, pre-operative and intra-operative evaluation resulted in conflicting diagnostic findings. Despite this, a high inguinal approach was utilised to perform a successful surgical repair of an incarcerated, obstructed obturator hernia. This surgical approach may be particularly useful when diagnostic incongruity exists on the exact type of hernia suspected following pre-operative and radiological assessment.

The literature on laparoscopic repair of obturator hernias is quite sparse, probably due to a combination of the rarity of these cases and the relatively recent emergence of laparoscopic hernia surgery. Both trans-abdominal and extra-peritoneal laparoscopic approaches have been described in the literature.8–10 Laparoscopic repair has been shown to produce less post-operative pain, fewer pulmonary complications and shorter hospital stays in such cases. Given these results, and the fact that obturator hernias classically tend to occur in patients that have limited physiological reserve, an argument could be made for a shift in practice from open repairs towards laparoscopic repairs.

4. Conclusions

Despite many papers dealing with various surgical techniques used in treatment of obturator hernias, it is important to emphasise diagnosis and early intervention is the most important aspect of management. Obturator hernias carry significant morbidity and mortality rates, therefore rapid clinical and radiological assessment followed by early surgery is critical to successful treatment.

A high suspicion for obturator hernia should be maintained when assessing a patient presenting with bowel obstruction particularly where intermittent symptoms or medial thigh pain are present. A full assessment of the hernial orifices including screening for the Howship–Rhomberg sign should not be overlooked.

Early CT scanning should be considered in cases where inguinal and femoral hernias have been ruled out by clinical examination. This should increase speed of diagnosis and therefore reduce complications such as bowel ischaemia and the need for bowel resection at the time of surgery.

Open approaches are well documented with good hernial defect repair rates but are not without complications of open abdomino-pelvic surgery. A push towards laparoscopic repair may be appropriate in the classical patient group if repair effectiveness and recurrence rates are shown to be similar to those seen following open repairs. Further research into the laparoscopic repair of obturator hernias needs conducted before this transition can be made.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author's contributions

Nicholas Hodgins and Krzysztof Cieplucha have written the manuscript. Essam Ghareeb has reviewed the final manuscript and edited the manuscript. Padhraic Conneally has provided the images and associated comments.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Nicholas Hodgins, Email: nickhodgins@googlemail.com.

Krzysztof Cieplucha, Email: krzysztof.cieplucha@westerntrust.hscni.net.

Padhraic Conneally, Email: padhraic.conneally@westerntrust.hscni.net.

Essam Ghareeb, Email: essam.ghareeb@westerntrust.hscni.net.

References

- 1.Mantoo S.K., Mak K., Tan T.J. Obturator hernia: diagnosis and treatment in the modern era. Singapore Medical Journal. 2009;50(9):866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Clerq L., Coenegrachts K., Feryn T., Van Couter A., Vandevoorde P., Verstraete K. An elderly woman with obstructed obturator hernia: a less common variety of external abdominal hernia. Journal Belge de Radiologie – Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Radiologi. 2010;93:302–304. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjork A.K.J., Cahill D.R. Obturator hernia. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1988;167:217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho Y.H., Goh H.S. Obstructed obturator hernia in 90 year olds—a management dilemma. Annals of the Academy of Medicine. 1991;20(3):410–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamadar D., Jacobson J., Morag Y., Girish G., Ebrahim F., Gest T. Sonography of inguinal region hernias. American Journalism Review. 2006;187:185–190. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yokoyama Y., Yamaguchi A., Isogai M., Hori A., Kaneoka Y. Thirty-six cases of obturator hernia: does computerised tomography contribute to postoperative outcome? World Journal of Surgery. 1999;23:2144–2147. doi: 10.1007/pl00013176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dundamadappa S.K., Tsou I.Y., Goh J.S. Clinics in diagnostic imaging. Singapore Medical Journal. 2006;47:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreno-Egea A., La Calle M.C., Torralba-Martinez J.A. Obturator hernia as a cause of chronic pain after inguinal hernioplasty: elective management using tomography and ambulatory total extraperitoneally laparoscopy. Surgical Laparoscopy Endoscopy & Percutaneous Techniques. 2006;16:54–57. doi: 10.1097/01.sle.0000202184.34666.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J.M., Lin H.F., Chen K.H., Tseng L.M., Huang S.H. Laparoscopic pre-peritoneal mesh repair of incarcerated obturator hernia and contralateral direct inguinal hernia. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques A. 2006;16:616–619. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.16.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt L., Morrison C., Lengyel J., Sagar P. Laparoscopic management of an obstructed obturator hernia: should laparoscopic assessment be the default option? Hernia. 2009;13(3):313. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]