Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the outcome of treatment with methotrexate for noninfectious ocular inflammation.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Participants

Patients with noninfectious ocular inflammation managed at 4 tertiary ocular inflammation clinics in the United States observed to add methotrexate as a single, noncorticosteroid immunosuppressive agent to their treatment regimen, between 1979 and 2007, inclusive.

Methods

Participants were identified from the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases Cohort Study. Demographic and clinical characteristics, including dosage, route of administration of methotrexate, and main outcome measures, were obtained for every eye of every patient at every visit via medical record review by trained expert reviewers.

Main Outcome Measures

Control of inflammation, corticosteroid-sparing effects, and incidence of and reason for discontinuation of therapy.

Results

Among 384 patients (639 eyes) observed from the point of addition of methotrexate to an anti-inflammatory regimen, 32.8%, 9.9%, 21.4%, 14.6%, 15.1%, and 6.3%, respectively, had anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior or panuveitis, scleritis, ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid, and other forms of ocular inflammation. In these groups, complete suppression of inflammation sustained for ≥28 days was achieved within 6 months in 55.6%, 47.4%, 38.6%, 56.4%, 39.5%, and 76.7%, respectively. Corticosteroid-sparing success (sustained suppression of inflammation with prednisone ≤10 mg/d) was achieved within 6 months among 46.1%, 41.3%, 20.7%, 37.3%, 36.5%, and 50.9%, respectively. Overall, success within 12 months was 66% and 58.4% for sustained control and corticosteroid sparing ≤10 mg), respectively. Methotrexate was discontinued within 1 year by 42% of patients. It was discontinued owing to ineffectiveness in 50 patients (13%); 60 patients (16%) discontinued because of side effects, which typically were reversible with dose reduction or discontinuation. Remission was seen in 43 patients, with 7.7% remitting within 1 year of treatment.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that adding methotrexate to an anti-inflammatory regimen not involving other noncorticosteroid immunosuppressive drugs is moderately effective for management of inflammatory activity and for achieving corticosteroid-sparing objectives, although many months may be required for therapeutic success. Methotrexate was well tolerated by most patients, and seems to convey little risk of serious side effects during treatment.

Financial Disclosure(s)

The authors have no proprietary or commercial interests in any of the materials discussed in this article.

Corticosteroids typically serve as the initial treatment for noninfectious inflammatory eye conditions. Addition of immunosuppressive therapy to a corticosteroid treatment regimen for ocular inflammation is indicated when corticosteroid therapy fails to control inflammation, when corticosteroid-sparing therapy is needed to minimize the side effects of systemic corticosteroids, and/or for certain diseases that have shown better response to the early initiation of noncorticosteroid immunosuppression.1 The 4 main classes of immunosuppressive agents that have been used for these purposes are antimetabolites, T-cell inhibitors, alkylating agents, and biologic response modifiers.1 Herein, the term “immunosuppressive agents” is used to refer to these 4 classes of agents, not including corticosteroids.

Methotrexate, a member of the antimetabolite class, has been the immunosuppressive agent most commonly used for ocular inflammation. Methotrexate was introduced in 1948 as an antineoplastic agent,2 and was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis in 1988. The mechanism of action of methotrexate is by reducing cell proliferation, increasing the rate of T-cell apoptosis, increasing endogenous adenosine concentrations, and altering cytokine production and humoral responses.3 When given orally, up to 35% of the methotrexate dose may be metabolized by the intestinal flora before absorption. When given parenterally, methotrexate is completely absorbed.

Use of methotrexate as a treatment for ocular inflammation was reported in 1965.4 Since then, small- to medium sized series have reported methotrexate to be effective for ocular inflammation in general,5–10 as well as for specific ocular inflammatory conditions, including juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis,11–14 sarcoidosis-related panuveitis,15 mucous membrane pemphigoid,16 rheumatoid arthritis-associated scleritis and episcleritis,17 sympathetic ophthalmia,18 and corticosteroid-resistant uveitis.19–22 Although case reports demonstrate detectable intraocular levels after systemic administration,23,24 extraocular effects of the drug on the immune system likely provide the primary therapeutic mechanism by which systemically administered methotrexate affects ocular inflammation.

To provide more robust information regarding the usefulness of methotrexate for ocular inflammatory diseases, we herein have reported the outcomes of 384 patients managed at 4 ocular inflammation referral centers in the United States, who were followed from the point of addition of methotrexate to an ocular inflammation treatment regimen.

Methods

Study Population

The methods of the SITE Cohort Study have been described previously.25 In brief, the cohort consists of all patients with ocular inflammation seen at 4 ocular immunology and uveitis clinics since the inception of the center, and an approximate 40% random sample of such patients at a 5th center. For this report, data from 1 of the first 4 centers were excluded, because its co-management approach—wherein many follow-up visits conducted at other centers were not available and patients often did not return to the center when response to therapy was favorable—biased ascertainment of the outcomes studied herein. At the other centers, all patients with noninfectious ocular inflammatory disease who have been treated with methotrexate were identified; those initiating methotrexate as a sole (noncorticosteroid) immunosuppressive agent during observation constitute the study population reported. All patients were seen between 1979 and 2007, inclusive.

Data Collection

Information on all patients with noninfectious ocular inflammation was entered into a custom database (Access, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) by trained expert reviewers. The available information for every eye of every patient at every visit was entered. Data relevant to this report included demographic information, ophthalmologic examination findings, presence or absence of systemic illnesses, ocular surgeries, and all medications in use at every clinic visit (including all use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs).

Main Outcome Measures

Patients were followed from the time that they started methotrexate until they stopped methotrexate, added a second immunosuppressive agent, stopped attending a study clinic, or the end of study data collection was reached, whichever occurred first. Inflammatory status was categorized as “active,” “slightly active,” or “inactive” for every eye at every visit, based on the clinician’s notations at the time of each visit. The study defined “slightly active” inflammation as “activity that is minimally present, described also by terms such as mild, few, or trace cells, and so on,” whereas inflammation was scored as inactive when described by terms such as “quiet,” “quiescent,” “no cells,” and “no active inflammation.” Anterior chamber cells had been graded at the time of clinical examinations in a manner generally similar to the system ultimately adopted for this purpose by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group.26Vitreous cells had been graded on an ordinal scale of 0, 0.5+, 1+, 2+, 3+, and 4+. Vitreous haze, when available, was graded according to the National Eye Institute system,27 subsequently adopted by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group,26 or a post hoc approximation thereof. Corticosteroid-sparing effects were evaluated based on time to reduction of the prednisone dose to 10, 5, or 0 mg without reactivation of the ocular inflammation, among those not meeting the respective criterion for success at the outset. Prednisone-equivalent doses of alternative corticosteroids28 were calculated for these evaluations when necessary. Discontinuation of methotrexate and the reasons for discontinuation were noted.

Statistical Methods

Frequencies of variables at enrollment and outcomes were tabulated for the study population using SAS version 9.1 (SAS, Cary, NC). Because stopping the treatment or adding an additional agent likely indicates failure of treatment, we used a time-to-success approach to evaluate the benefits of therapy. Outcomes were not accepted until they had been observed over ≥2 visits spanning ≥28 days, to avoid counting transient improvements and brief interruptions of therapy as successes or failures. Time-to-success outcomes and the proportions observed to have outcomes by 6 and 12 months’ treatment were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, by person and/or by eye. Incidence of methotrexate discontinuation and reasons for stopping methotrexate were summarized using incidence rates and Kaplan–Meier estimates. Multiple regression analysis using Cox proportional hazards models29 was used to adjust for potentially confounding variables, such as demographic characteristics, anatomic location of inflammation, highest methotrexate dosage, and prior use of immunosuppressive therapies. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted using alternative definitions of success to evaluate the extent to which results would be different under alternative standards for “success.”

Results

Among patients who started methotrexate during follow-up, 384 were identified who used methotrexate as the only treatment for ocular inflammation other than local therapies, corticosteroids, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. These patients were followed up at the centers while taking methotrexate monotherapy for a median of 0.73 years (interquartile range, 0.31–1.59). The characteristics of the patients and their involved eyes at the time of starting methotrexate are given as Table 1. Further details are provided in Table 2 (available online at http://aaojournal.org). The median age was 46.9 years. The cohort was predominantly female(72.9%) and Caucasian (73.2%). A total of 639 eyes were affected by different forms of ocular inflammation, including anterior uveitis (126 patients; 208 eyes), intermediate uveitis (38 patients; 63 eyes), posterior uveitis or panuveitis (82 patients; 142 eyes), scleritis (56 patients; 84 eyes), ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid (58 patients; 109 eyes) and other forms of ocular inflammation (24 patients; 33 eyes). At the time of starting methotrexate, 66.4% of patients had bilateral involvement, 232 eyes (36.3%) had a visual acuity of ≤20/50, and 225 eyes (35.2%) had slightly active or active inflammation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients and Eyes on Starting Methotrexate (MTX)

| Characteristic | Anterior Uveitis | Intermediate Uveitis | Posterior or Panuveitis | Scleritis | Mucus Membrane Pemphigoid | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-specific characteristics | |||||||

| Patient number | 126 | 38 | 82 | 56 | 58 | 24 | 384 |

| Median age, y (range) | 33.9 (5.3–83.3) | 32.1 (7.6–63.3) | 44.0 (7.5–81.6) | 56.1 (0.4–90.9) | 75.3 (49.9–93.5) | 50.5 (15.1–82.6) | 46.9 (0.4–93.5) |

| Gender, % female | 90 (71.4%) | 28 (73.7%) | 63 (76.8%) | 42 (75.0%) | 41 (70.7%) | 16 (66.7%) | 280 (72.9%) |

| Race | |||||||

| % Caucasian | 95 (75.4%) | 29 (76.3%) | 39 (47.6%) | 43 (76.8%) | 55 (94.8%) | 20 (83.3%) | 281 (73.2%) |

| % Black | 20 (15.9%) | 6 (15.8%) | 31 (37.8%) | 6 (10.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (16.7%) | 67 (17.4%) |

| % Other | 11 (8.7%) | 3 (7.9%) | 12 (14.6%) | 7 (12.5%) | 3 (5.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 36 (9.4%) |

| Duration of inflammation, y (range) | 2.7 (0.0–37.0) | 3.3 (0.0–26.7) | 3.5 (0.0–26.7) | 0.6 (0.0–17.6) | 1.1 (0.0–14.6) | 0.7 (0.0–12.7) | 2.1 (0.0–37.0) |

| Bilateral Inflammation | 82 (65.1%) | 25 (65.8%) | 60 (73.2%) | 28 (50.0%) | 51 (87.9%) | 9 (37.5%) | 255 (66.4%) |

| Prednisone ≤10 mg/d | 98 (77.8%) | 27 (71.1%) | 40 (48.8%) | 27 (48.2%) | 47 (81.0%) | 13 (54.2%) | 252 (65.6%) |

| Highest MTX dose (mg/wk) | |||||||

| ≤12.5 | 61 (48.4%) | 23 (60.5%) | 36 (43.9%) | 24 (42.9%) | 37 (63.8%) | 12 (50.0%) | 193 (50.3%) |

| >12.5 and ≤17.5 | 27 (21.4%) | 7 (18.4%) | 24 (29.3%) | 16 (28.6%) | 10 (17.2%) | 6 (25.0%) | 90 (23.4%)s |

| >17.5 and ≤22.5 | 22 (17.5%) | 6 (15.8%) | 11 (13.4%) | 7 (12.5%) | 5 (8.6%) | 4 (16.7%) | 55 (14.3%) |

| ≥22.5 | 16 (12.7%) | 2 (5.3%) | 11 (13.4%) | 9 (16.1%) | 6 (10.3%) | 2 (8.3%) | 46 (12.0%) |

| Oral dosing of MTX | 105 (83.3%) | 29 (76.3%) | 69 (84.1%) | 49 (87.5%) | 55 (94.8%) | 22 (91.7%) | 329 (85.7%) |

| Prior MTX | 8 (6.3%) | 3 (7.9%) | 8 (9.8%) | 2 (3.6%) | 5 (8.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 26 (6.8%) |

| Prior antimetabolites (other than MTX) | 4 (3.2%) | 3 (7.9%) | 6 (7.3%) | 8 (14.3%) | 11 (19.0%) | 3 (12.5%) | 35 (9.1%) |

| Prior alkylating agent | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (8.5%) | 2 (3.6%) | 9 (15.5%) | 6 (25.0%) | 25 (6.5%) |

| Prior T-cell inhibitor | 3 (2.4%) | 2 (5.3%) | 9 (11.0%) | 2 (3.6%) | 1 (1.7%) | 2 (8.3%) | 19 (4.9%) |

| Prior Biologics | 6 (4.8%) | 1 (2.6%) | 2 (2.4%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.2%) | 11 (2.9%) |

| Any prior immunosuppressive agent* | 10 (7.9%) | 4 (10.5%) | 18 (22.0%) | 12 (21.4%) | 16 (27.6%) | 8 (33.3%) | 68 (17.7%) |

| Eye-specific characteristics | |||||||

| No. of affected eyes | 208 | 63 | 142 | 84 | 109 | 33 | 639 |

| ≤20/50 | 61 (29.3%) | 21 (33.3%) | 72 (50.7%) | 15 (17.9%) | 48 (44.0%) | 15 (45.5%) | 232 (36.3%) |

| ≤20/200 | 24 (11.5%) | 5 (7.9%) | 32 (22.5%) | 7 (8.3%) | 23 (21.1%) | 7 (21.2%) | 98 (15.3%) |

| Overall activity | |||||||

| Inactive | 141 (67.8%) | 48 (76.2%) | 82 (57.7%) | 52 (61.9%) | 61 (56.0%) | 26 (78.8%) | 410 (64.2%) |

| Slightly active | 27 (13.0%) | 8 (12.7%) | 24 (16.9%) | 9 (10.7%) | 12 (11.0%) | 1 (3.0%) | 81 (12.7%) |

| Active | 39 (18.8%) | 6 (9.5%) | 35 (24.6%) | 23 (27.4%) | 35 (32.1%) | 6 (18.2%) | 144 (22.5%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.6%) |

| Ocular complications† affected eyes, % | 110 (52.9%) | 33 (52.4%) | 84 (59.2%) | 15 (17.9%) | 34 (31.2%) | 8 (24.2%) | 284 (44.4%) |

Total does not add up because some patients were on >1 prior immunosuppressive agent.

Ocular complications included raised intraocular pressure >21 mmHg and >30 mmHg, hypotony, band keratopathy, macular edema, epiretinal membrane formation, exudative retinal detachment, retinal neovascularization, choroidal neovascularization, and glaucoma and cataract surgeries.

Table 2.

Inflammatory Activity and Ocular Complications Present at Initiation of Methotrexate

| Characteristic | Anterior Uveitis | Intermediate Uveitis | Posterior or Panuveitis | Scleritis | Mucus Membrane Pemphigoid | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of affected eyes | 208 | 63 | 142 | 84 | 109 | 33 | 639 |

| Prednisone dose ≤10 mg/d | 163 (78.4%) | 45 (71.4%) | 69 (48.6%) | 36 (42.9%) | 89 (81.7%) | 16 (48.5%) | 418 (65.4%) |

| Ocular hypertension (>21 mmHg) | 33 (16.8%) | 4 (6.9%) | 16 (11.3%) | 7 (9.1%) | 8 (10.7%) | 2 (7.7%) | 70 (12.2%) |

| Ocular hypertension (>30 mmHg) | 6 (3.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 2 (1.4%) | 2 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (1.9%) |

| Hypotony | 6 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (2.9%) | 3 (3.9%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 14 (2.5%) |

| Band keratopathy | 26 (13.1%) | 2 (3.2%) | 9 (6.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 37 (6.1%) |

| Macular edema | 9 (5.4%) | 8 (14.3%) | 20 (16.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 37 (7.9%) |

| Epiretinal membrane formation | 13 (7.7%) | 16 (28.6%) | 30 (24.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.0%) | 60 (12.8%) |

| Exudative retinal detachment | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Retinal neovascularization | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Choroidal neovascularization | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.6%) |

| Glaucoma surgery | 11 (5.3%) | 2 (3.2%) | 7 (4.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 22 (3.4%) |

| Cataract surgery | 64 (30.8%) | 12 (19.0%) | 47 (33.1%) | 6 (7.1%) | 27 (24.8%) | 5 (15.2%) | 161 (25.2%) |

| Anterior chamber cell | |||||||

| No cell | 124 (59.6%) | 41 (65.1%) | 81 (57.0%) | 80 (95.2%) | 107 (98.2%) | 31 (93.9%) | 464 (72.6%) |

| 0.5+ | 36 (17.3%) | 15 (23.8%) | 31 (21.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.0%) | 83 (13.0%) |

| 1.0+ | 26 (12.5%) | 4 (6.3%) | 15 (10.6%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 46 (7.2%) |

| ≥2.0+ | 21 (10.1%) | 2 (3.2%) | 14 (9.9%) | 3 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.0%) | 41 (6.4%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (0.8%) |

| Vitreous cell | |||||||

| No cell | 184 (88.5%) | 35 (55.6%) | 87 (61.3%) | 80 (95.2%) | 85 (78.0%) | 31 (93.9%) | 502 (78.6%) |

| 0.5+ | 11 (5.3%) | 6 (9.5%) | 22 (15.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 40 (6.3%) |

| 1.0+ | 7 (3.4%) | 12 (19.0%) | 18 (12.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 37 (5.8%) |

| ≥2.0+ | 3 (1.4%) | 8 (12.7%) | 10 (7.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 22 (3.4%) |

| Missing | 3 (1.4%) | 2 (3.2%) | 5 (3.5%) | 2 (2.4%) | 24 (22.0%) | 2 (6.1%) | 38 (5.9%) |

| Vitreous haze | |||||||

| None | 201 (96.6%) | 47 (74.6%) | 118 (83.1%) | 82 (97.6%) | 85 (78.0%) | 31 (93.9%) | 564 (88.3%) |

| 0.5+ | 1 (0.5%) | 12 (19.0%) | 12 (8.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 25 (3.9%) |

| 1.0+ | 4 (1.9%) | 2 (3.2%) | 7 (4.9%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 14 (2.2%) |

| Missing | 2 (1.0%) | 2 (3.2%) | 5 (3.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | 24 (22.0%) | 2 (6.1%) | 36 (5.6%) |

Table 3 summarizes success of therapy patients achieved with methotrexate. Information on treatment success from the by eye perspective is given in Table 4 (available online at http://aaojournal. org). Among patients with active or slightly active inflammation at the start of methotrexate therapy, complete control of inflammation sustained over 2 visits spanning ≥28 days was achieved at or before 6 months for 55.6%, 47.4%, 38.6%, 56.4%, and 39.5% of patients with anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior or panuveitis, scleritis, and ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid, respectively. The proportion achieving complete control of inflammation continued to improve between 6 and 12 months of therapy, with 67.2%, 74.9%, 52.1%, 71.5%, and 65%, respectively, achieving complete control of inflammation by 12 months of methotrexate therapy. Success at or before 6 months was 7% to 16% more frequent if improvement from “active” to “inactive or slightly active” was used as the criterion for success.

Table 3.

Outcomes of Methotrexate (MTX) Therapy by Patient

| Outcome | Anterior Uveitis | Intermediate Uveitis | Posterior or Panuveitis | Scleritis | Mucus Membrane Pemphigoid | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Used as only immunosuppressive drug therapy | 126 | 38 | 82 | 56 | 58 | 24 | 384 |

| Treatment success within 6 months (% [95% CI]) | |||||||

| Controlled inflammation | |||||||

| No activity | 55.6 (45.5–66.4) | 47.4 (30.2–68.3) | 38.6 (27.2–52.7) | 56.4 (40.9–73.1) | 39.5 (25.9–56.8) | 76.7 (52.2–94.3) | 49.4 (43.4–55.8) |

| No activity or slightly active | 69.7 (58.4–80.4) | 62.8 (42.2–83.3) | 53.9 (39.7–69.6) | 63.7 (46.8–80.3) | 56.0 (38.9–74.5) | 74.3 (48.6–93.8) | 62.8 (56.0–69.5) |

| Plus ≤10 mg prednisone/d | 46.1 (36.5–56.8) | 41.3 (25.2–62.3) | 20.7 (12.5–33.0) | 37.3 (24.9–53.2) | 36.5 (23.5–53.7) | 50.9 (29.2–76.9) | 37.3 (32.0–43.3) |

| Plus ≤5 mg prednisone/d | 41.8 (32.4–52.5) | 31.8 (17.9–52.5) | 20.2 (12.2–32.3) | 26.3 (15.7–42.0) | 33.6 (21.1–50.6) | 48.1 (26.2–75.7) | 32.6 (27.4–38.4) |

| Without systemic corticosteroids | 6.2 (2.8–13.2) | 7.4 (1.9–26.5) | 3.0 (0.8–11.5) | 4.3 (1.1–16.0) | 4.4 (1.1–16.7) | 7.1 (1.0–40.9) | 5.1 (3.1–8.3) |

| MTX dose decreased after stable dose maintained | 19/81 (23.5%) | 8/25 (32.0%) | 11/54 (20.4%) | 5/33 (15.2%) | 4/24 (16.7%) | 3/11 (27.3%) | 50/228 (21.9%) |

| Corticosteroid-sparing (prednisone ≤10 mg/d) success after reduction in dose | 0/19 (0.0%) | 2/8 (25.0%) | 1/11 (9.1%) | 0/5 (0.0%) | 0/4 (0.0%) | 0/3 (0.0%) | 3/50 (6.0%) |

| MTX dose increased after stable dose maintained | 38/81 (46.9%) | 12/25 (48.0%) | 22/54 (40.8%) | 16/33 (48.5%) | 8/24 (33.3%) | 4/11 (36.4%) | 100/228 (43.9%) |

| Corticosteroid sparing (prednisone ≤10 mg/d) success after increase in dose | 9/38 (23.7%) | 2/12 (16.7%) | 9/22 (40.9%) | 5/16 (31.3%) | 2/8 (25.0%) | 0/4 (0.0%) | 27/100 (27.0%) |

| Treatment success within 12 months (% [95% CI]) | |||||||

| Controlled inflammation | |||||||

| No Activity | 67.2 (56.7–77.3) | 74.9 (56.1–90.3) | 52.1 (38.6–67.1) | 71.5 (52.8–87.7) | 65.0 (48.3–81.3) | 92.2 (70.6–99.5) | 66.0 (59.6–72.3) |

| No activity or slightly active | 71.6 (60.3–82.1) | 89.4 (71.4–98.2) | 66.2 (51.2–80.6) | 79.2 (57.0–94.7) | 70.7 (52.2–87.0) | 100 | 74.3 (67.5–80.4) |

| Plus ≤10 mg prednisone/d | 62.6 (52.2–73.1) | 68.8 (49.8–86.1) | 39.1 (27.1–54.2) | 58.3 (42.0–75.4) | 66.9 (50.4–82.4) | 83.6 (51.1–99.0) | 58.4 (52.1–64.9) |

| Plus ≤5 mg prednisone/d | 59.4 (48.9–70.1) | 57.0 (38.9–76.4) | 32.0 (21.1–46.6) | 55.6 (39.4–73.2) | 60.7 (44.5–77.4) | 65.4 (35.3–92.5) | 52.9 (46.6–59.5) |

| Without systemic corticosteroids | 17.6 (11.1–27.1) | 15.0 (5.9–35.2) | 11.9 (5.4–24.9) | 17.5 (8.7–33.5) | 26.8 (15.3–44.4) | 52.8 (25.7–85.1) | 18.8 (14.5–24.3) |

CI = confidence interval.

Table 4.

Outcomes of Methotrexate Therapy by Eye

| Reason | No. of Affected Patients | Kaplan–Meier Estimate ≤1 Year, % (95% CI) | Events per Person-Year, 95% CI (All Persons) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinuation for side effects | 60 (16%) | 17.5 (13.5–22.7) | 0.13 (0.10–0.17) |

| GI upset | 11 (2.9%) | 3.3 (1.8–6.2) | 0.02 (0.01–0.04) |

| Bone marrow suppression | 10 (2.6%) | 3.0 (1.4–6.3) | 0.02 (0.01–0.04) |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 9 (2.3%) | 3.6 (1.8–7.1) | 0.02 (0.01–0.04) |

| Malaise | 8 (2.1%) | 2.1 (0.9–5.3) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) |

| Allergy | 6 (1.6%) | 1.7 (0.8–3.8) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) |

| Mouth ulcers | 5 (1.3%) | 1.9 (0.7–4.7) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) |

| Infection | 3 (0.8%) | 1.4 (0.4–4.4) | 0.01 (0.00–0.02) |

| Respiratory complaint | 2 (0.5%) | 0.7 (0.2–2.7) | 0.00 (0.00–0.02) |

| Hair loss | 2 (0.5%) | 0.5 (0.1–3.3) | 0.00 (0.00–0.02) |

| Cirrhosis of the liver | 1 (0.3%) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.00 (0.00–0.01) |

| Other side effect | 7 (1.8%) | 2.3 (1.1–4.9) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) |

| Ineffectiveness | 50 (13%) | 15.5 (11.6–20.6) | 0.11 (0.08–0.14) |

| Remission | 43 (11%) | 7.7 (4.7–12.5) | 0.09 (0.07–0.12) |

| Missing/unspecified | 49 (13%) | 10.2 (7.1–14.5) | 0.11 (0.08–0.14) |

| Total stopped methotrexate | 198 (52%) | 41.6 (36.3–47.3) | 0.42 (0.37–0.49) |

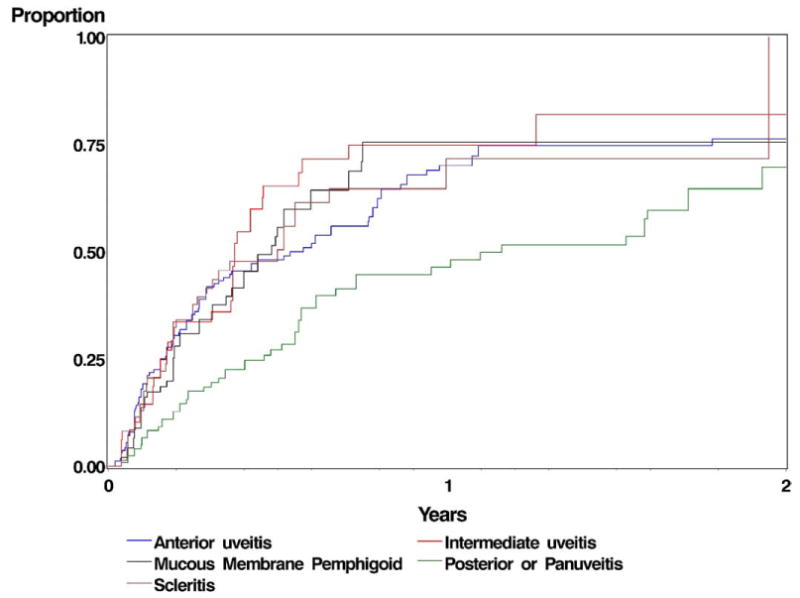

Corticosteroid-sparing success—defined as completely inactive inflammation at ≥2 visits spanning ≥28 days after tapering the prednisone dose to ≤10 mg/d—was achieved at or before 6 months among 46.1% of patients with anterior uveitis, 41.3% with intermediate uveitis, 20.7% with posterior uveitis or panuveitis, 37.3% with scleritis, and 36.5% with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid (Fig 1). Corticosteroid-sparing success also continued to improve with time, and was achieved at or before 12 months of methotrexate by 62.6% of patients with anterior uveitis, 68.8% with intermediate uveitis, 39.1% with posterior uveitis or panuveitis, 58.3% with scleritis, and 66.9% with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid. Sustained control of inflammation after tapering prednisone to ≤5 mg/d was achieved nearly as often, observed in 59.4%, 57%, 32.0%, 55.6%, and 60.7% patients with anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis or panuveitis, scleritis, and mucus membrane pemphigoid, respectively. Only 5.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.1–8.3) of patients were able to completely discontinue prednisone while maintaining sustained control of inflammation within the first 6 months of therapy, and 18.8% (95% CI, 14.5–24.3) within 12 months of therapy.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating the corticosteroid-sparing success of methotrexate for different categories of ocular inflammation.

Sensitivity analyses evaluating success in controlling inflammation and corticosteroid-sparing outcomes among patients not meeting these success criteria initially also were performed without requiring the 28-day period of controlled inflammation, so as to allow better comparisons with prior reports that used less stringent criteria for success. These analyses found that complete suppression of inflammation was achieved at any visit at or before 6 months in 70.5%, 74.4%, 55.8%, 63%, 71%, and 100% for anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis or panuveitis, scleritis, mucus membrane pemphigoid, and other inflammatory disorders, respectively. Among those who were counted as a success in the sensitivity analysis, which did not require success to be sustained but were not counted as a success in the primary analysis, 83% had a relapse of inflammation by the next visit, whereas for 17% control only was observed at the last visit, after which control may or may not have been sustained. Under this liberalized definition of success, corticosteroid-sparing success (prednisone ≤10 mg/d) was observed at any visit within 6 months among 56.4%, 66.6%, 40.9%, 41.5%, 53.5%, and 82.0% of patients, respectively.

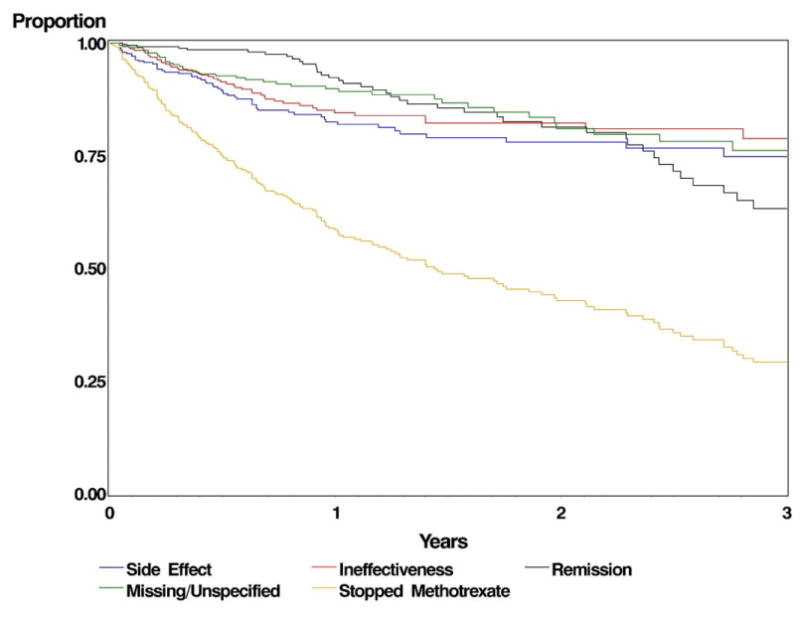

One hundred ninety-eight patients (52%) discontinued methotrexate (Table 5). Side effects attributed to methotrexate contributed to discontinuation for 16% of patients, usually early in the course of therapy (Kaplan–Meier estimate of discontinuation within 1 year = 17.5%). No single complication stood out as a leading cause of discontinuation of therapy. Therapy was discontinued within 1 year because of failure to control inflammation by 15.5% of patients, and for unknown reasons for 10.2% of patients. If we assume that the distribution of reasons for discontinuation of therapy in the latter group is the same as for patients where the cause for discontinuation was known, the proportion of all patients started on methotrexate who ended up stopping for side effects within 1 year would be 18.3%. A second immunosuppressive agent was added to methotrexate during follow-up for 60 patients (15.6%). After the first year of therapy, most discontinuation of therapy occurred on the basis of remission of disease; discontinuation for side effects or ineffectiveness was uncommon after that point (Fig 2). Forty-three patients discontinued methotrexate because of remission of disease, a rate of 8%/person-year, mostly ≥1 year after treatment initiation. One hundred twenty-six patients (32.8%) were still taking methotrexate monotherapy at the end of follow-up, after a median of 380 days of treatment (interquartile range, 133–658).

Table 5.

Reasons Contributing to Discontinuation of Methotrexate

| Reason | No. of Affected Patients | Kaplan-Meier Estimate ≤1 Year, % (95% Confidence Interval (CI)) | Events per Person-Year, 95% CI (All Persons) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinuation for side effects | 60 (16%) | 17.5 (13.5–22.7) | 0.13 (0.10, 0.17) |

| Gastrointestinal upset | 11 (2.9%) | 3.3 (1.8–6.2) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04) |

| Bone marrow suppression | 10 (2.6%) | 3.0 (1.4–6.3) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04) |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 9 (2.3%) | 3.6 (1.8–7.1) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04) |

| Malaise | 8 (2.1%) | 2.1 (0.9–5.3) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) |

| Allergy | 6 (1.6%) | 1.7 (0.8–3.8) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.03) |

| Mouth ulcers | 5 (1.3%) | 1.9 (0.7–4.7) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.03) |

| Infection | 3 (0.8%) | 1.4 (0.4–4.4) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) |

| Respiratory Complaint | 2 (0.5%) | 0.7 (0.2–2.7) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.02) |

| Hair Loss | 2 (0.5%) | 0.5 (0.1–3.3) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.02) |

| Cirrhosis of the liver | 1 (0.3%) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.01) |

| Other Side Effect | 7 (1.8%) | 2.3 (1.1–4.9) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) |

| Ineffectiveness | 50 (13%) | 15.5 (11.6–20.6) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.14) |

| Remission | 43 (11%) | 7.7 (4.7–12.5) | 0.09 (0.07, 0.12) |

| Missing/Unspecified | 49 (13%) | 10.2 (7.1–14.5) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.14) |

| Total stopped Methotrexate | 198 (52%) | 41.6 (36.3–47.3) | 0.42 (0.37, 0.49) |

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve showing the proportion of subjects continuing methotrexate therapy.

Multiple regression analysis was performed, evaluating whether demographic or clinical characteristics could be identified as factors predictive of a favorable response to therapy (Table 6). Race and gender did not seem to have any association with the control of inflammation or corticosteroid-sparing effect of methotrexate. Compared with adults ages 18 to 39, children under the age of 18 were less likely (P<0.05) to experience treatment success (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] for control of inflammation, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.20 – 0.55; adjusted HR for corticosteroid-sparing, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.22–0.57). Compared with anterior uveitis, control of inflammation and corticosteroid-sparing success occurred less often with posterior uveitis or panuveitis (adjusted HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.28–0.72 and adjusted HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.28–0.72, respectively). Patients with other forms of ocular inflammation did not consistently differ from patients with anterior uveitis at achieving success outcomes. Patients who had used T-cell inhibitors in the past were 3 times as likely to gain control of inflammation (adjusted HR, 3.08; 95% CI, 1.51–6.31) than those using methotrexate for the first time. However, prior use of other immunosuppressive agents was not associated with significantly different rates of treatment success. No difference in success rates was observed with alternative dosages of methotrexate, or with use of oral versus parenteral therapy. Coexisting systemic autoimmune disease was not associated with lesser control of inflammation. Multiple regression analysis evaluating discontinuation for side effects also did not indicate significant differences between oral versus parenteral administration of methotrexate, nor between different methotrexate dosages (data not shown).

Table 6.

Factors Associated with Success Using Methotrexate as a Single Immunosuppressive Agent

| Characteristic | Crude HR Control of Inflammation HR (95% CI, P)* |

Adjusted HR Control of Inflammation HR (95% CI, P)* |

Crude HR Corticosteroid-sparing Success (≤10 mg/d Prednisone) HR (95% CI, P)* |

Adjusted HR Corticosteroid-sparing Success (≤10 mg/dPrednisone) HR (95% CI, P)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 1.13 (0.85–1.51, 0.40) | 1.11 (0.81–1.51, 0.52) | 0.95 (0.69–1.30, 0.75) | 0.96 (0.70–1.33, 0.82) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 0.89 (0.60–1.33, 0.57) | 0.91 (0.59–1.40, 0.68) | 0.60 (0.39–0.91, 0.02) | 0.63 (0.40–0.99, 0.04) |

| Other | 0.78 (0.46–1.32, 0.36) | 0.69 (0.40–1.21, 0.20) | 0.83 (0.48–1.42, 0.49) | 0.71 (0.39–1.30, 0.27) |

| Age (y) | ||||

| <18 | 0.41 (0.25–0.66, 0.00) | 0.33 (0.20–0.55, <.0001) | 0.53 (0.33–0.85, 0.01) | 0.43 (0.26–0.73, 0.00) |

| 18–39 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 40–54 | 0.87 (0.58–1.32, 0.52) | 1.03 (0.69–1.54, 0.89) | 0.91 (0.60–1.37, 0.65) | 0.97 (0.62–1.51, 0.89) |

| 55–64 | 0.86 (0.55–1.36, 0.52) | 0.85 (0.52–1.37, 0.50) | 1.04 (0.67–1.62, 0.86) | 0.98 (0.59–1.60, 0.92) |

| ≥65 | 0.93 (0.61–1.42, 0.74) | 1.42 (0.84–2.43, 0.20) | 1.09 (0.70–1.69, 0.71) | 1.30 (0.78–2.16, 0.31) |

| Type of inflammation | ||||

| Anterior | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | 1.06 (0.61–1.85, 0.83) | 0.96 (0.59–1.57, 0.88) | 1.10 (0.63–1.94, 0.73) | 0.89 (0.52–1.54, 0.68) |

| Posterior or panuveitis | 0.69 (0.46–1.03, 0.07) | 0.42 (0.26–0.68, 0.00) | 0.60 (0.41–0.90, 0.01) | 0.45 (0.28–0.72, 0.00) |

| Scleritis | 1.28 (0.83–1.99, 0.26) | 0.85 (0.52–1.37, 0.50) | 1.17 (0.75–1.83, 0.48) | 0.78 (0.47–1.28, 0.32) |

| Mucus membrane pemphigoid | 0.97 (0.66–1.42, 0.86) | 0.50 (0.30–0.85, 0.01) | 1.16 (0.74–1.81, 0.51) | 0.72 (0.42–1.24, 0.23) |

| Other | 2.60 (1.41–4.81, 0.00) | 1.57 (0.80–3.10, 0.19) | 1.52 (0.77–3.00, 0.23) | 1.11 (0.56–2.17, 0.77) |

| Previous methotrexate | ||||

| Yes | 1.10 (0.58–2.09, 0.76) | 1.23 (0.52–2.89, 0.64) | 0.63 (0.28–1.43, 0.27) | 0.80 (0.30–2.18, 0.67) |

| Other antimetabolite(s) before treatment | ||||

| Yes | 0.93 (0.50–1.72, 0.81) | 0.90 (0.41–1.96, 0.78) | 0.88 (0.52–1.48, 0.63) | 0.95 (0.53–1.71, 0.88) |

| T-cell inhibitor(s) before treatment | ||||

| Yes | 2.20 (1.20–4.03, 0.01) | 3.08 (1.51–6.31, 0.00) | 0.96 (0.43–2.15, 0.92) | 1.48 (0.58–3.75, 0.41) |

| Biologic(s) before treatment | ||||

| Yes | 0.25 (0.03–1.88, 0.18) | 0.10 (0.01–1.11, 0.06) | 0.53 (0.14–1.97, 0.34) | 0.61 (0.13–2.97, 0.54) |

| Alkylating agent(s) before treatment | ||||

| Yes | 0.73 (0.38–1.40, 0.34) | 0.59 (0.32–1.08, 0.09) | 0.67 (0.30–1.48, 0.32) | 0.58 (0.24–1.38, 0.22) |

| Route–oral | ||||

| Yes | 1.03 (0.65–1.63, 0.90) | 0.99 (0.58–1.68, 0.97) | 1.21 (0.77–1.91, 0.42) | 1.30 (0.75–2.24, 0.35) |

| Dosage (mg/wk) | ||||

| ≤12.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| >12.5 and ≤17.5 | 1.03 (0.70–1.52, 0.87) | 1.05 (0.70–1.57, 0.83) | 1.05 (0.71–1.54, 0.81) | 1.10 (0.73–1.64, 0.66) |

| >17.5 and ≤22.5 | 1.02 (0.57–1.82, 0.94) | 1.13 (0.63–2.00, 0.69) | 0.87 (0.52–1.47, 0.60) | 1.02 (0.61–1.71, 0.94) |

| >22.5 | 1.09 (0.60–1.97, 0.79) | 1.33 (0.71–2.50, 0.37) | 0.93 (0.52–1.65, 0.79) | 1.23 (0.66–2.27, 0.51) |

| Systemic (extraocular) autoimmune disease† | ||||

| Yes | 0.98 (0.74–1.30, 0.91) | 0.89 (0.65–1.23, 0.50) | 0.85 (0.64–1.14, 0.28) | 0.70 (0.50–0.98, 0.04) |

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

Hazard ratio (95% CI, P value).

Ankylosing spondylitis, Behçet’s disease, Cogan’s syndrome, erythema nodosum, familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis, giant cell arteritis, Graves’ disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, multiple sclerosis, pemphigus, polyarteritis nodosum, polymyositis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, relapsing polychondritis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, scleroderma, Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosis, Takayasu’s disease, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and other forms of arteritis.

In sensitivity analyses, similar patterns of association between the demographic and clinical characteristics and treatment success were observed when evaluating success in terms of accomplishment of corticosteroid-sparing to the level of 5 mg or to discontinuation of prednisone, although the proportion achieving these levels of corticosteroid sparing was lower. Likewise, the pattern of association was similar if reduction of inflammation from “active” to either “inactive” or “slightly active” was used as the standard of success, and the proportion achieving success was slightly higher.

Discussion

Our results indicate that methotrexate is reasonably effective for ocular inflammation. However, not all patients experience treatment success, and several months of treatment may be needed before success is observed. Among published reports regarding methotrexate therapy, the definitions of treatment success reported vary, making direct comparisons with our results difficult. Samson et al8 retrospectively evaluated use of methotrexate in 160 patients, including 14 for whom cyclosporine was added when methotrexate alone was deemed ineffective. Defining success as the presence of <1+ cellular reaction for 6 consecutive months, or the absence of active lesions in posterior uveitis cases, they achieved control of inflammation in 76% patients and were able to taper prednisone to ≤8 mg/d in 64% of their patients. These results were reported based on a mean duration of methotrexate therapy of 14 months and a mean follow-up of 16.4 months (range, 1–96), rather than at specific time points. Simultaneous evaluation of control of inflammation and prednisone dose was not done. Galor et al30 retrospectively reviewed 90 patients on methotrexate initially taking >10 mg of prednisone. Their patients took a median time of 6.5 months to achieve treatment success, defined as absence of ocular inflammation at ≤10 mg/d prednisone; 42% of the patients demonstrated corticosteroid-sparing success at the end of a 6-month window. Each of these reports derived from centers participating in the SITE Cohort Study; their patients were included in this report if they started methotrexate as a single immunosuppressive therapy during the SITE Cohort Study follow-up period. Kaplan-Messas et al6 reported full or partial control of inflammation in 79% of 39 patients, with response to treatment occurring at a mean of 2.4±0.8 months. Shah et al7 reported that 16 of their 22 patients had a reduction in inflammation by a mean of 5 weeks.

What differences exist between this report and ours likely are owing to differences in the inclusion criteria (we limited the cohort to patients receiving methotrexate mono-therapy) and our stricter treatment success definitions. Sensitivity analyses that did not require observation of sustained success produced higher success rates, with results more similar to those of the previous reports. Although our approach of requiring observation of sustained control of inflammation before counting treatment as a success may have resulted in our missing a small number of cases in which the patient did not return to clinic after achieving success, our approach is more realistic in that many patients relapse just after achieving control of inflammation or corticosteroid-sparing goals, as we demonstrated. These patients have not truly experienced successful treatment, suggesting that previous reports may have overestimated success. Also, in accordance with quality reporting standards for the field,26 we did not consider “last visit” data to calculate outcome, but instead evaluated success of methotrexate therapy after a period of 6 months of monotherapy, an approach that can be expected to provide a lower proportion of success given that some patients gain treatment success after 6 months.

Beneficial effects of methotrexate seemed to vary by the type of ocular inflammation, with posterior uveitis or panuveitis responding to methotrexate less often than other forms of ocular inflammation to methotrexate therapy. This pattern of results was consistent across alternative definitions of success and whether success was evaluated by eye or by patient, suggesting that real differences in therapeutic effects of methotrexate across different sites of ocular inflammation could exist. However, differences in spontaneous remission rates between types of ocular inflammation, differences in disease severity, and/or other factors also may explain this difference in responsiveness. It is possible that different subtypes of ocular inflammation at the same anatomic site may exhibit heterogeneity of response to methotrexate, which was not directly addressed by this report.

Comparison of subcutaneous versus oral administration of methotrexate did not show significant differences between these routes of administration, although moderate differences in benefits and likelihood of discontinuation for side effects could have been missed with the available statistical power. Hoekstra et al31 have shown improved effect for rheumatoid arthritis when methotrexate was administered subcutaneously at dosages of ≥25 mg/wk.31 Our results regarding doses and the likelihood of response or discontinuation for side effects are difficult to interpret because clinicians often started with lower doses and advanced to higher doses when initial response was not satisfactory. A randomized trial comparing initial low-dose and initial high-dose therapy would be required to sort out whether higher doses have greater risk-to-benefit ratio for patients with ocular inflammation than lower doses.

Our finding that prior use of other immunosuppressive agents does not seem to be associated with lack of response to methotrexate suggests that patients who have failed other agents may still respond to methotrexate.

Other factors associated with treatment success were few. Children were substantially less likely to gain control of inflammation with methotrexate than adults. However, our observation may simply reflect greater severity of inflammation occurring in the pediatric age range in our tertiary populations,8,32,33 not a deficiency of effectiveness of methotrexate with respect to alternative drugs. Further data are needed to determine whether other agents may be more effective than methotrexate in this age range.

Regarding the tolerability of methotrexate therapy, approximately 18% of patients stopped treatment because of side effects within the first year of treatment, but few stopped because of side effects thereafter. A similar rate of discontinuation of methotrexate was observed in a previous report, based on an overlapping, smaller group of patients.8 Because laboratory abnormalities and substantial symptoms leading to discontinuation of therapy typically were well documented in the charts, it is likely that few of the patients discontinuing therapy for unknown reasons was because of toxicity. Historically, elevated liver enzymes, debilitating nausea, and fatigue have been reported to be the most common side effects with methotrexate, usually occurring within the first 3 months of treatment.6,8,34 Other systemic side effects reported include cytopenia, stomatitis,35–38 and, occasionally, interstitial pneumonitis.39–42 Ocular side effects of methotrexate, including irritation and dry eye, have been reported.43 There also have been reports of the rare occurrence of toxic optic neuropathy, which is reversible with addition of folic acid.44,45 Such side effects were either infrequent or did not seem to have a major negative impact in our hands, because dose reduction or drug discontinuation typically was successful in alleviating these problems. Serious adverse events such as bone marrow suppression (0.02 cases/person-year) and cirrhosis of the liver (0.002 cases/person-year) were rare in our population. Thus, use of systemic methotrexate therapy for ocular inflammation does not seem to incur a high risk of complications during therapy when patients are monitored for predictable side effects. This conclusion would be reached even if we were to make the extreme assumption that all patients stopping for unknown reasons had toxicity. Although this analysis did not compare adverse effects of methotrexate with alternative immunosuppressive drugs, a previous report found that within the first year of treatment the proportion of patients discontinuing methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil owing to side effects was the same (0.09), whereas the proportion discontinuing azathioprine for side effects was substantially higher (0.24).46

Although we did not assess teratogenicity, methotrexate is a known teratogen, even at doses of 10 mg/wk, with the critical period being 8 and 12 weeks postconception. Exposure during this period can cause miscarriages and fetal malformations.47,48 Therefore, use of effective methods of birth control and substitution of therapy ≥3 months before attempting conception is recommended. Immunosuppression has been suggested to cause increased risk of malignancy with chronic use. However, our work in reviewing the existing literature from other disease states regarding cancer risk with methotrexate49 suggests that such risk is minimal or absent with the use of methotrexate for ocular inflammation.

Limitations of the study arise from the retrospective nature of data collection from clinical records.25 Although the participating centers followed a standardized approach in the abstraction of clinical data from records, and the treatment and grading approaches historically used at the participating centers was similar to those ultimately adopted by consensus groups,1,26 the degree of standardization was less than could have been achieved in a prospective study. Because the study was conducted at tertiary care centers, cases may have been more severe than would have been seen in primary ophthalmology clinics, with the result that methotrexate may seem to be less effective at our centers than had it been studied in alternative settings. However, many patients requiring immunosuppressive therapy are likely to be managed at a tertiary center. Also, the data covered nearly 30 years, during which secular trends may have occurred. However, use of methotrexate has not changed a great deal during that period, other than a trend toward use of parenteral treatment and higher doses, which was captured directly by the study. The more rigorous definition of treatment success used in this study than prior studies likely reduces the apparent treatment benefit of methotrexate vis-à-vis the prior reports, but may be a more realistic metric of success, given that recurrent inflammation was observed at the next visit for the large majority who would have been classified as a success under more lenient criteria.

Strengths of the study include its large sample size, providing greater ability to ascertain the likelihood of treatment success, safety, side effects, and remission rates. Data collection was highly standardized, using an extensive array of quality control mechanisms, to optimize data quality within the constraints of a retrospective design.25 We followed the approach for reporting clinical outcomes advocated by a consensus group26 to as great an extent as possible in a retrospective study. We evaluated the effect of methotrexate as a single immunosuppressive agent, thereby eliminating potential confounding effects of other immuno-suppressive agents that were used in combination with methotrexate by some patients in other reports. It is likely that more success and more side effects would be observed when methotrexate is used in combination with other immunosuppressive agents than as monotherapy.

In summary, our data suggest that when a patient with ocular inflammation meets indications for the addition of immunosuppressive therapy to a treatment regimen, addition of methotrexate has a moderate chance of achieving control of inflammation and/or of maintaining control of inflammation while tapering prednisone dosages to ≤10 mg. The beneficial effects of methotrexate may not be seen for months, during which time other therapies (typically corticosteroids) usually are needed to control inflammation. Methotrexate is likely to be well tolerated, and important long-term adverse effects seem to be rare when methotrexate is used and monitored in a manner similar to commonly accepted guidelines.1 When side effects do occur, they are likely to be reversible. It would be valuable to identify biological or genetic markers predictive of a favorable response to methotrexate, which would enable methotrexate to be targeted to the patients most likely to respond to such therapy. The site of ocular inflammation may be one such factor, in that posterior and panuveitis seem less likely to respond to methotrexate than other forms of ocular inflammation, although this may reflect disease severity rather than differential responsiveness. Randomized, controlled trials would be valuable to determine more accurately whether use of higher doses and/or subcutaneous administration improve a patient’s chances of treatment success with methotrexate.

Acknowledgments

Supported primarily by National Eye Institute Grant EY014943 (JHK). Additional support was provided by Research to Prevent Blindness and the Paul and Evanina Mackall Foundation. Dr Kempen is a Research to Prevent Blindness James S. Adams Special Scholar Award recipient. Drs Jabs and Rosenbaum are Research to Prevent Blindness Senior Scientific Investigator Award recipients. Dr Thorne is a Research to Prevent Blindness Harrington Special Scholar Award recipient. Dr Levy-Clarke was previously supported by and Dr Nussenblatt continues to be supported by intramural funds of the National Eye Institute.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure(s):

The authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any of the materials discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Foster CS, et al. Guidelines for the use of immunosuppressive drugs in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders: recommendations of an expert panel. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:492–513. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farber S, Diamond LK, Mercer RD, et al. Temporary remissions in acute leukemia in children produced by folic antagonist 4-aminopteroylglutamic acid (aminopterin) N Engl J Med. 1948;238:787–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194806032382301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wessels JA, Huizinga TW, Guchelaar HJ. Recent insights in the pharmacological actions of methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:249–55. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong VG, Hersh EM. Methotrexate in the therapy of cyclitis. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1965;69:279–93. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okada AA. Immunomodulatory therapy for ocular inflammatory disease: a basic manual and review of the literature. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005;13:335–51. doi: 10.1080/09273940590951034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan-Messas A, Barkana Y, Avni I, Neumann R. Methotrexate as a first-line corticosteroid-sparing therapy in a cohort of uveitis and scleritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2003;11:131–9. doi: 10.1076/ocii.11.2.131.15919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah SS, Lowder CY, Schmitt MA, et al. Low-dose methotrexate therapy for ocular inflammatory disease. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1419–23. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31790-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samson CM, Waheed N, Baltatzis S, Foster CS. Methotrexate therapy for chronic noninfectious uveitis: analysis of a case series of 160 patients. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1134–9. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00576-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bom S, Zamiri P, Lightman S. Use of methotrexate in the management of sight-threatening uveitis. Ocul Immunol In-flamm. 2001;9:35–40. doi: 10.1076/ocii.9.1.35.3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malik AR, Pavesio C. The use of low dose methotrexate in children with chronic anterior and intermediate uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:806–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.054239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foeldvari I, Wierk A. Methotrexate is an effective treatment for chronic uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:362–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shetty AK, Zganjar BE, Ellis GS, Jr, et al. Low-dose methotrexate in the treatment of severe juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and sarcoid iritis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1999;36:125–8. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19990501-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hemady RK, Baer JC, Foster CS. Immunosuppressive drugs in the management of progressive, corticosteroid-resistant uveitis associated with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1992;32:241–52. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199203210-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace CA, Bleyer WA, Sherry DD, et al. Toxicity and serum levels of methotrexate in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:677–81. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dev S, McCallum RM, Jaffe GJ. Methotrexate treatment for sarcoid-associated panuveitis. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:111–8. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCluskey P, Chang JH, Singh R, Wakefield D. Methotrexate therapy for ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:796–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinblatt ME, Coblyn JS, Fox DA, et al. Efficacy of low-dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:818–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198503283121303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazar M, Weiner MJ, Leopold IH. Treatment of uveitis with methotrexate. Am J Ophthalmol. 1969;67:383–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(69)92051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holz FG, Krastel H, Breitbart A, et al. Low-dose methotrexate treatment in noninfectious uveitis resistant to corticosteroids. Ger J Ophthalmol. 1992;1:142–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong VG. Methotrexate treatment of uveal disease. Am J Med Sci. 1966;251:239–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong VG. Immunosuppressive therapy of ocular inflammatory diseases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969;81:628–37. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1969.00990010630006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hersh EM, Wong VG, Freireich EJ. Inhibition of the local inflammatory response in man by antimetabolites. Blood. 1966;27:38–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puchta J, Hattenbach LO, Baatz H. Intraocular levels of methotrexate after oral low-dose treatment in chronic uveitis. Ophthalmologica. 2005;219:54–5. doi: 10.1159/000081784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Smet MD, Stark-Vancs V, Kohler DR, et al. Intraocular levels of methotrexate after intravenous administration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:442–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kempen JH, Daniel E, Gangaputra S, et al. Methods for identifying long-term adverse effects of treatment in patients with eye diseases: the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases (SITE) Cohort Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:47–55. doi: 10.1080/09286580701585892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data: results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nussenblatt RB, Palestine AG, Chan CC, Roberge F. Standardization of vitreal inflammatory activity in intermediate and posterior uveitis. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:467–71. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schimmer BP, Parker KL. Adrenocorticotropic hormone; ad-renocortical steroids and their synthetic analogs; inhibitors of the synthesis and actions of adrenocortical hormones. In: Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL, editors. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. pp. 1587–612. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox DR, Oakes D. Analysis of Survival Data. London: Chap-man & Hall; 1984. pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galor A, Jabs DA, Leder HA, et al. Comparison of antimetabolite drugs as corticosteroid-sparing therapy for noninfectious ocular inflammation. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1826–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoekstra M, Haagsma C, Neef C, et al. Bioavailability of higher dose methotrexate comparing oral and subcutaneous administration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:645–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heiligenhaus A, Mingels A, Heinz C, Ganser G. Methotrexate for uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: value and requirement for additional anti-inflammatory medication. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007;17:743–8. doi: 10.1177/112067210701700509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorne JE, Woreta F, Kedhar SR, et al. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: incidence of ocular complications and visual acuity loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:840–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Ede AE, Laan RF, Blom HJ, et al. Methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: an update with focus on mechanisms involved in toxicity. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1998;27:277–92. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(98)80049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker AM, Funch D, Dreyer NA, et al. Determinants of serious liver disease among patients receiving low-dose methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:329–35. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tolman KG, Clegg DO, Lee RG, Ward JR. Methotrexate and the liver. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1985;12(suppl):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoekstra M, van Ede AE, Haagsma CJ, et al. Factors associated with toxicity, final dose, and efficacy of methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:423–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.5.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lahdenne P, Rapola J, Ylijoki H, Haapasaari J. Hepatotoxicity in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis receiving longterm methotrexate therapy. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:2442–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suwa A, Hirakata M, Satoh S, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis associated with methotrexate-induced pneumonitis: improvement with i.v. cyclophosphamide therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999;17:355–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salaffi F, Manganelli P, Carotti M, et al. Methotrexate-induced pneumonitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis: report of five cases and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 1997;16:296–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02238967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cottin V, Tebib J, Massonnet B, et al. Pulmonary function in patients receiving long-term low-dose methotrexate. Chest. 1996;109:933–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.4.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hilliquin P, Renoux M, Perrot S, et al. Occurrence of pulmonary complications during methotrexate therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:441–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doroshow JH, Locker GY, Gaasterland DE, et al. Ocular irritation from high-dose methotrexate therapy: pharmacokinetics of drug in the tear film. Cancer. 1981;48:2158–62. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811115)48:10<2158::aid-cncr2820481007>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clare G, Colley S, Kennett R, Elston JS. Reversible optic neuropathy associated with low-dose methotrexate therapy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2005;25:109–12. doi: 10.1097/01.wno.0000166061.73483.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balachandran C, McCluskey PJ, Champion GD, Halmagyi GM. Methotrexate-induced optic neuropathy. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2002;30:440–1. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2002.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baker KB, Spurrier NJ, Watkins AS, et al. Retention time for corticosteroid-sparing systemic immunosuppressive agents in patients with inflammatory eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1481–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.097998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bawle EV, Conard JV, Weiss L. Adult and two children with fetal methotrexate syndrome. Teratology. 1998;57:51–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199802)57:2<51::AID-TERA2>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewden B, Vial T, Elefant E, et al. Low dose methotrexate in the first trimester of pregnancy: results of a French collaborative study. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2360–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kempen JH, Gangaputra S, Daniel E, et al. Long-term risk of malignancy among patients treated with immunosuppressive agents for ocular inflammation: a critical assessment of the evidence. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:802–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]