Abstract

Leucocytes migrate into and out of blood vessels at multiple points during their development and maturation, and during immune surveillance. In response to tissue damage and infection, they are rapidly recruited through the endothelium lining blood vessels into the tissues. Leukaemia cells also move in and out of the bloodstream during leukaemia progression. Rho GTPases are intracellular signalling proteins that regulate cytoskeletal dynamics and are key coordinators of cell migration. Here, we describe how different members of the Rho GTPase family act in leucocytes and leukaemia cells to regulate steps of transendothelial migration. We discuss how inhibitors of Rho signalling could be used to reduce leucocyte or leukaemia cell entry into tissues.

Keywords: Rho GTPases, cell migration, actin cytoskeleton, leucocytes, endothelial cells

1. Introduction

Rho GTPases regulate cytoskeletal dynamics, and thereby affect a variety of cellular processes including cell polarity, migration, adhesion and vesicle trafficking. Rho GTPases are highly conserved in evolution and found in nearly all eukaryotes sequenced to date. There are 20 Rho GTPase genes in humans, most of which encode proteins of 20–28 kDa. Rho GTPase expression varies across tissues and is regulated by multiple stimuli. They exert their function by interaction with downstream targets including protein kinases, phospholipases, adaptor proteins and actin nucleators [1,2].

Most Rho GTPases cycle between a guanine diphosphate (GDP)-bound inactive form and a guanine triphosphate (GTP)-bound active form that interacts with downstream effector proteins. The GTP–GDP switch is regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that promote exchange of bound GDP for GTP and GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) that stimulate GTP hydrolysis to GDP. The Rho GTPases RhoU and RhoV have a high-intrinsic GDP/GTP exchange rate and are therefore mainly GTP-bound in cells [3]. Rnd, RhoH and RhoBTB proteins lack GTPase activity, hence they are constitutively bound to GTP [4].

Rho GTPases are post-translationally modified by addition of isoprenyl and/or palmitoyl lipid groups at the C-terminus, facilitating their interaction with membranes where they signal to downstream effectors [5]. Unlike isoprenylation, palmitoylation is a reversible process. This allows proteins to associate transiently with membranes, regulating their localization or endocytic trafficking [6,7]. The Rho GTPases RhoU and RhoV are targeted to membranes by palmitoylation and are not prenylated. Rac1 was recently demonstrated to be palmitoylated, which requires its prior prenylation. Rac1 palmitoylation appears to be important for it to stimulate actin cytoskeleton remodelling [8].

The Rho GTPase Cdc42 is well known to contribute to cell polarity in multiple eukaryotic organisms, from polarized growth and mating in yeasts, to polarized cell migration and epithelial polarity in mammals [9]. Here, we focus on the roles of Rho GTPases in leucocytes and leukaemia cells during their polarized migration across the endothelium.

2. Rho GTPases and leucocyte migration

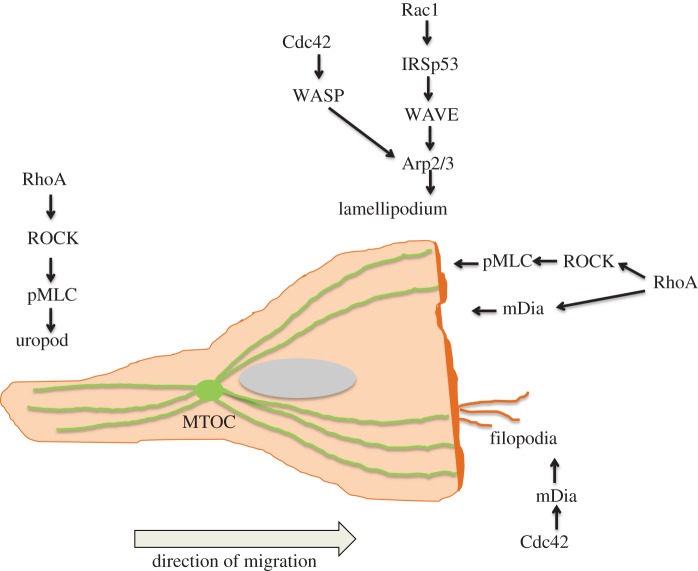

Cell polarization and migration are driven by actin cytoskeletal dynamics, which is regulated by Rho GTPases acting on actin nucleators and actin-regulatory proteins [2]. Migrating leucocytes have an F-actin-rich lamellipodium at the front and a contractile uropod at the back (figure 1). Transmigrating leucocytes extend lamellipodia and filopodia under the endothelium [10] (figure 2). The main regulators of lamellipodium extension in leucocytes are Rac1 and Rac2 [11,12]. Rac GTPases regulate actin polymerization through the WAVE complex, consisting of WAVE, PIR121/Sra-1, Nap125, HSPC300 and Abl interactor. Rac binds to PIR121/Sra-1. In response to stimuli, WAVE can activate the Arp2/3 complex, inducing actin polymerization [13]. Cdc42 can also activate WASP and N-WASP leading to actin nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex [14].

Figure 1.

Leucocyte polarity and Rho GTPases. Rac1 activates the WAVE complex, leading to Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization at the leading edge to form a lamellipodium. Cdc42 can also contribute to membrane extension via WASP which activates the Arp2/3 complex. RhoA is active at the front of the cell and is proposed to induce actin polymerization and membrane protrusion via the formin mDia and membrane retraction via ROCK. Cdc42 induces filopodia via mDia. RhoA activation at the rear of the cell controls uropod contractility through ROCK inhibtion of MLC phosphatase and subsequent MLC phosphorylation. In polarized leucocytes, the microtubule organizing centre (MTOC) normally localizes behind the nucleus in the uropod region. (Online version in colour.)

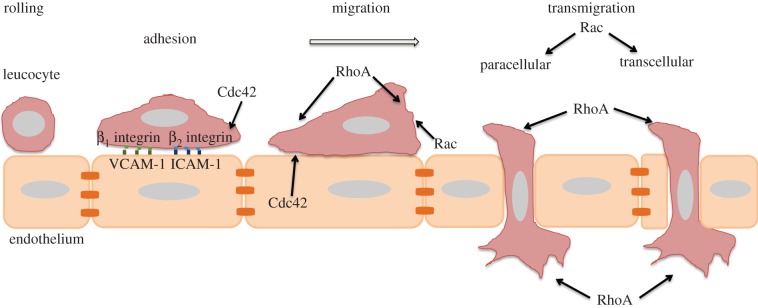

Figure 2.

Roles of Cdc42, Rac1/2 and RhoA in transendothelial migration (TEM). Schematic of leucocyte TEM. Rolling is the first step of TEM, which is mediated by selectins and their ligands. Subsequently, leucocytes firmly adhere to the endothelium through binding of active β1 and β2 integrins to VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 receptors on the endothelium. Leucocytes can then transmigrate via a paracellular route passing through endothelial junctions or a transcellular route through a transient pore in the body of an endothelial cell. The Cdc42 target WASP affects leucocyte adhesion by regulating β2 integrin clustering. Cdc42, Rac1/2 and RhoA all affect the ability of leucocytes to polarize and migrate on top of endothelial cells. RhoA acts at the front and back of transmigrating cells during TEM, and Rac1/2 also contribute to TEM. (Online version in colour.)

Formin family proteins nucleate non-branching actin filaments and also contribute to lamellipodium as well as filopodium formation [15,16]. Depolymerization of actin filaments is mediated by ADF/cofilin proteins that bind preferentially to ADP-actin, promoting the release of actin monomers. Cofilin activity is regulated by Rac and Rho via PAK and ROCK, which phosphorylate LIMK, which in turn phosphorylates and inhibits cofilin [17]. Cdc42 induces filopodium formation via mDia formins; transmigrating T-acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL) cells extend filopodia under the endothelium [13].

The uropod at the back of migrating leucocytes contains contractile actomyosin filaments, which require RhoA and ROCK for their assembly [18] (figure 1). Actin filaments are linked to the plasma membrane and transmembrane receptors in the uropod by ezrin–radixin–moesin proteins, which are also linked to Rho/ROCK signalling.

3. Leucocyte and leukaemia cell transendothelial migration

Leucocytes cross the endothelium in low numbers into lymph nodes and tissues during immune surveillance [19]. At a site of inflammation, however, endothelial cells get activated and upregulate expression of adhesion receptors for leucocytes including selectins, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 [20]. This leads to rapid recruitment of leucocytes into inflamed tissues. Leukaemia cells proliferate in niches in the bone marrow and/or lymph nodes, and therefore need to adhere to and cross the endothelium to enter these sites [21–23].

Leucocytes first roll on endothelial cells through low-affinity interactions between selectins and selectin ligands. Chemokines present on the surface of activated endothelial cells then stimulate integrin activation on leucocytes, leading to firm adhesion to ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, followed by transendothelial migration (TEM) [24] (figure 2).

Leucocytes can cross the endothelium by going between endothelial cells (paracellular route), which involves local disassembly of endothelial cell–cell junctions [25] (figure 2). Alternatively, they can take a transcellular route, in which a transcellular pore through an endothelial cell transiently opens, allowing the leucocyte to cross through [26]. The choice between these two routes may depend on the tissue, endothelial stimulus and type of leucocyte.

4. Cdc42 and transendothelial migration

Cdc42 was found to prevent the formation of a lamellipodium in the uropod, thereby preventing the formation of ‘two-headed’ T cells and preserving polarity [27]. Cdc42 is required for chemokine-driven TEM of effector memory CD4 T cells [28]. However, T-ALL cells do not show impairment of TEM following Cdc42 depletion [10].

The Cdc42 effector WASP contributes to TEM. WASP-deficient macrophages and neutrophils show defective clustering of β2 integrins (which bind to the endothelial receptor ICAM-1) and impaired adhesion to and transmigration across endothelial cells [29]. Another effector for Cdc42 is Par6, which is part of the polarity complex that includes Par3 and the atypical PKCs (aPKCι and aPKCζ). The Par complex controls T cell migratory polarity [30], but so far it is not known whether Par3, Par6 and aPKCs contribute to TEM.

5. Rac proteins and transendothelial migration

The two main Rac proteins expressed in leucocytes, Rac1 and Rac2, appear to have different functions. Rac2 depletion reduces T-ALL cell TEM, whereas Rac1 depletion had only a small effect on TEM [10]. This might reflect a higher level of Rac2 in T-ALL cells. However, in neutrophils, Rac1 and Rac2 contribute different aspects of actin dynamics in lamellipodia [31–33].

Interestingly, the RacGEF Tiam1 controls the route of T cell TEM: Tiam1-deficient mouse T cells predominantly use a transcellular route rather than paracellular route. PKCζ, Tiam1 and Rac are required for efficient migration of T cells on endothelial cells [34]. As Rac-driven lamellipodia are likely to be required for both paracellular and transcellular leucocyte TEM, this suggests that different RacGEFs are involved for transcellular versus paracellular TEM, presumably because different leucocyte receptors mediate each pathway.

6. RhoA regulates leucocyte polarity on endothelial cells

The first evidence that Rho subfamily members in leucocytes contributed to TEM came from studies using the Clostridial exoenzyme C3 transferase, which covalently ADP-ribosylates and inhibits the closely related proteins RhoA, RhoB and RhoC [35]. Monocytes treated with C3 transferase adhered normally to endothelial cells but showed a defect in tail retraction, preventing them from completing TEM.

We subsequently showed that RhoA plays a central role both at the leading edge and uropod of transmigrating T-ALL cells. Active RhoA was found at the front and back of T-ALL cells during TEM and its activity correlated with both retraction and protrusion [10]. At the front, it colocalized with the formin mDia1, suggesting that it could stimulate actin polymerization in lamellipodia and/or filopodia extending under endothelial cells (figure 2). It was also associated with localized areas of retraction in the lamellipodium, suggesting that it could be important for determining turning.

The uropod generates a contractile force through myosin II interaction with actin bundles [13]. RhoA is a major player in the T cell uropod because it is a regulator on myosin II activity. RhoA induces myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation and inhibits MLC phosphatase via its downstream targets ROCK1 and ROCK2 [36,37]. The RhoA/ROCK/myosinII axis was also shown to be important in T-ALL TEM by controlling actomyosin contractility, and indeed knock-down of both ROCK1 and ROCK2 together reduced TEM [10]. The RhoGEF GEF-H1 might contribute to RhoA activation in the uropod.

In polarized leucocytes, the microtubule organizing centre (MTOC) localizes at the back of the cell, behind the nucleus, along with ROCK [18]. Treatment of T cells with nocodazole depolymerizes microtubules, increasing RhoA activity and cell contractility, and inducing loss of migratory polarity [37]. This phenotype could be reversed by adding ROCK inhibitors, indicating that the balance between RhoA-driven protrusion and contraction is critical for T cell migration (figure 2).

7. Other Rho family members and leucocyte migration

Several Rho family members in addition to RhoA, Rac1/2 and Cdc42 have been implicated in leucocyte migration in vitro and/or in vivo, although so far their roles in TEM have not specifically been studied. These include RhoU and RhoH, which are atypical Rho GTPase family members that are predominantly GTP-bound and regulated by changes in phosphorylation, gene expression and degradation, rather than GTP/GDP cycling [4].

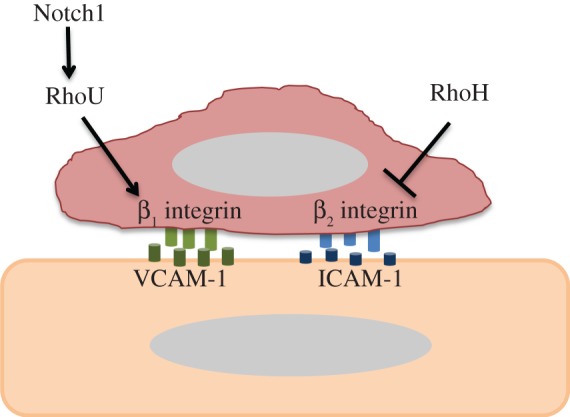

RhoH suppresses β2 integrin/LFA-1 adhesion to ICAM-1 and impairs chemotaxis [38,39], so would be expected to reduce TEM of T cells (figure 3), although this has not been tested. Homing of CLL cells lacking RhoH to the bone marrow is reduced [40], which might, in part, reflect a decrease in interaction with bone marrow endothelial cells.

Figure 3.

Postulated roles of RhoH and RhoU in TEM. RhoH inhibits β2 integrin activation in leucocytes, and hence is postulated to reduce adhesion to endothelial cells and TEM. RhoU expression is induced by Notch signalling and promotes adhesion of T-ALL leukaemia cells via β1 integrin. It would therefore be expected to stimulate TEM. (Online version in colour.)

RhoU was described as a target gene for the Notch1 oncogene in T-ALL [41]. RhoU is most closely related to Cdc42 (57% identical at the amino acid sequence level) but together with RhoV forms a distinct subfamily of the Rho family [42,43]. RhoU was demonstrated to be important for T-ALL cell adhesion to fibronectin and also for chemotaxis and migration, possibly through its role in adhesion. It was also shown that Notch1 siRNA depletion induced a decrease in the adhesion and migration of T-ALL cell lines, suggesting that Notch1 could affect migration of T-ALL cells through RhoU [41]. These data suggest that RhoU affects β1 integrin-mediated adhesion, and could thereby affect adhesion and subsequent TEM of leucocytes (figure 3).

8. Small molecule inhibitors of Rho GTPases and transendothelial migration

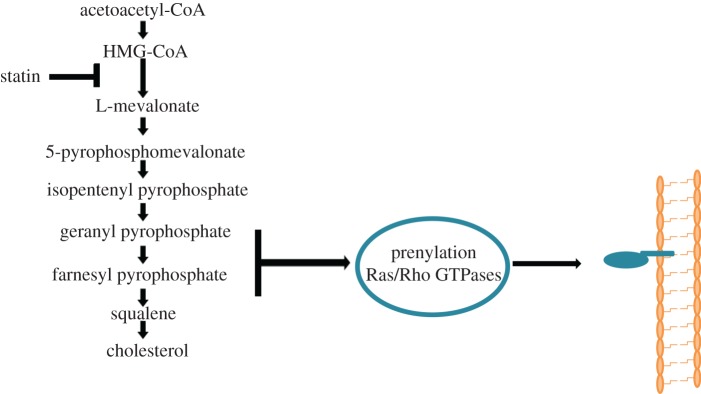

Several small molecule inhibitors that affect Rho GTPase signalling have been tested for their effects on TEM and have the potential to be used clinically either to treat leukaemia patients or to reduce chronic inflammation. Statins are best known for their effects on cholesterol levels, but the same metabolic pathway leads to synthesis of isoprenyl groups used for Rho family GTPase modification as well as multiple other prenylated proteins [44] (figure 4). Statin treatment of cells reduces Rho family signalling by reducing their interaction with membranes, which are their principal sites of action [45]. Interestingly, statin treatment of T-ALL cells reduces TEM, in part by reducing integrin LFA-1 activation and adhesion to its ligand ICAM-1. It turns out that the effect of statin treatment on T-ALL adhesion is mediated by Rap1b [46]. However, RhoA and Rac1 are also affected by statins, and it is likely that they contribute to the reduction in TEM in statin-treated T-ALL cells, but not specifically to LFA-1 activation.

Figure 4.

Statins inhibit Rho GTPase prenylation. 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase catalyses the synthesis of mevalonate, which is required for synthesis of geranylgeranylpyrophosphate and farnesylpyrophosphate (isoprenyl groups). These groups are covalently added to most Rho GTPases, allowing their anchorage to membranes. Statins inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, and hence decrease post-translational modifications on Rho GTPases, and thereby inhibit Rho GTPase signalling. Statins also prevent synthesis of cholesterol. (Online version in colour.)

Further evidence for Rac and Rho signalling in TEM comes from treatment of cells with the Rac inhibitor NSC23766 and ROCK inhibitors. The Rac inhibitor appears to reduce Rac activation by affecting GEF interaction with Rac [47]. It would be predicted to reduce TEM although this has not so far been directly tested. The ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 was initially shown to inhibit TEM of monocytes by inhibiting tail retraction [35]. Y-27632 also inhibited tail retraction of T-ALL cells migrating on endothelial cells [10]. In vivo, the ROCK inhibitor fasudil reduced leucocyte interaction with endothelial cells following ischaemia–reperfusion [48], although the relative contribution of fasudil treatment to endothelial versus leucocyte responses was not established. Fasudil is well known to inhibit endothelial activation [49], and thus more studies on how it contributes to leucocytes and leukaemia cells during TEM in vivo would be interesting.

9. Conclusions and future perspectives

The classical Rho GTPases RhoA, Rac1/2 and Cdc42 have each been studied in the context of leucocyte and/or leukaemia cell TEM in vitro, but so far little is known of how other members of the Rho family contribute to this process. It will be important to characterize further the roles of each Rho GTPase in the different steps of the TEM process, from rolling, integrin-mediated adhesion, polarization and choice of transcellular versus paracellular routes of transmigration (figure 2). In the future, targeted knock-out of Rho GTPases in leucocytes and leukaemia models combined with intravital microscopy [50] should determine the relative contribution of each family member to TEM in vivo. Finally, identifying the specific RhoGEFs and downstream targets of Rho GTPases involved in TEM should allow the development of more targeted therapies for inhibiting chronic inflammation and leukaemia progression.

References

- 1.Heasman SJ, Ridley AJ. 2008. Mammalian Rho GTPases: new insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 690–701 (doi:10.1038/nrm2476) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridley AJ. 2012. Historical overview of Rho GTPases. Methods Mol. Biol. 827, 3–12 (doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-442-1_1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shutes A, Berzat AC, Cox AD, Der CJ. 2004. Atypical mechanism of regulation of the Wrch-1 Rho family small GTPase. Curr. Biol. 14, 2052–2056 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aspenstrom P, Ruusala A, Pacholsky D. 2007. Taking Rho GTPases to the next level: the cellular functions of atypical Rho GTPases. Exp. Cell Res. 313, 3673–3679 (doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.07.022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaffe AB, Hall A. 2005. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 247–269 (doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charollais J, Van Der Goot FG. 2009. Palmitoylation of membrane proteins. Mol. Membr. Biol. 26, 55–66 (doi:10.1080/09687680802620369) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resh MD. 2006. Trafficking and signaling by fatty-acylated and prenylated proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 584–590 (doi:10.1038/nchembio834) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navarro-Lerida I, Sanchez-Perales S, Calvo M, Rentero C, Zheng Y, Enrich C, Del Pozo MA. 2012. A palmitoylation switch mechanism regulates Rac1 function and membrane organization. EMBO J. 31, 534–551 (doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.446) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etienne-Manneville S. 2004. Cdc42: the centre of polarity. J. Cell Sci. 117, 1291–1300 (doi:10.1242/jcs.01115) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heasman SJ, Carlin LM, Cox S, Ng T, Ridley AJ. 2010. Coordinated RhoA signaling at the leading edge and uropod is required for T cell transendothelial migration. J. Cell Biol. 190, 553–563 (doi:10.1083/jcb.201002067) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tybulewicz VLJ, Henderson RB. 2009. Rho family GTPases and their regulators in lymphocytes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 630–644 (doi:10.1038/nri2606) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridley AJ. 2011. Life at the leading edge. Cell 145, 1012–1022 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rougerie P, Delon J. 2012. Rho GTPases: masters of T lymphocyte migration and activation. Immunol. Lett. 142, 1–13 (doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2011.12.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris KP, Tepass U. 2010. Cdc42 and vesicle trafficking in polarized cells. Traffic 11, 1272–1279 (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01102.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campellone KG, Welch MD. 2010. A nucleator arms race: cellular control of actin assembly. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 237–251 (doi:10.1038/nrm2867) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faix J, Grosse R. 2006. Staying in shape with formins. Dev. Cell 10, 693–706 (doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiuchi T, Ohashi K, Kurita S, Mizuno K. 2007. Cofilin promotes stimulus-induced lamellipodium formation by generating an abundant supply of actin monomers. J. Cell Biol. 177, 465–476 (doi:10.1083/jcb.200610005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchez-Madrid F, Serrador JM. 2009. Bringing up the rear: defining the roles of the uropod. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 353–359 (doi:10.1038/nrm2680) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shechter R, London A, Schwartz M. 2013. Orchestrated leukocyte recruitment to immune-privileged sites: absolute barriers versus educational gates. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 206–218 (doi:10.1038/nri3391) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vestweber D. 2007. Adhesion and signaling molecules controlling the transmigration of leukocytes through endothelium. Immunol. Rev. 218, 178–196 (doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00533.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soma LA, Craig FE, Swerdlow SH. 2006. The proliferation center microenvironment and prognostic markers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Hum. Pathol. 37, 152–159 (doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2005.09.029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sison EA, Brown P. 2011. The bone marrow microenvironment and leukemia: biology and therapeutic targeting. Expert Rev. Hematol. 4, 271–283 (doi:10.1586/ehm.11.30) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayala F, Dewar R, Kieran M, Kalluri R. 2009. Contribution of bone microenvironment to leukemogenesis and leukemia progression. Leukemia 23, 2233–2241 (doi:10.1038/leu.2009.175) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller WA. 2011. Mechanisms of leukocyte transendothelial migration. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 6, 323–344 (doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130224) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dejana E. 2004. Endothelial cell–cell junctions: happy together. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 261–270 (doi:10.1038/nrm1357) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carman CV. 2009. Mechanisms for transcellular diapedesis: probing and pathfinding by ‘invadosome-like protrusions’. J. Cell Sci. 122, 3025–3035 (doi:10.1242/jcs.047522) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratner S, Piechocki MP, Galy A. 2003. Role of Rho-family GTPase Cdc42 in polarized expression of lymphocyte appendages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73, 830–840 (doi:10.1189/jlb.1001894) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manes TD, Pober JS. 2013. TCR-driven transendothelial migration of human effector memory CD4 T cells involves Vav, Rac, and Myosin IIA. J. Immunol. 190, 3079–3088 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1201817) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Schaff UY, Green CE, Chen H, Sarantos MR, Hu Y, Wara D, Simon SI, Lowell CA. 2006. Impaired integrin-dependent function in Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein-deficient murine and human neutrophils. Immunity 25, 285–295 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerard A, Mertens AE, van der Kammen RA, Collard JG. 2007. The Par polarity complex regulates Rap1- and chemokine-induced T cell polarization. J. Cell Biol. 176, 863–875 (doi:10.1083/jcb.200608161) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun CX, Magalhaes MA, Glogauer M. 2007. Rac1 and Rac2 differentially regulate actin free barbed end formation downstream of the fMLP receptor. J. Cell Biol. 179, 239–245 (doi:10.1083/jcb.200705122) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim MB, Kuiper JW, Katchky A, Goldberg H, Glogauer M. 2011. Rac2 is required for the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Leukoc. Biol. 90, 771–776 (doi:10.1189/jlb.1010549) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H, Sun C, Glogauer M, Bokoch GM. 2009. Human neutrophils coordinate chemotaxis by differential activation of Rac1 and Rac2. J. Immunol. 183, 2718–2728 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0900849) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerard A, van der Kammen RA, Janssen H, Ellenbroek SI, Collard JG. 2009. The Rac activator Tiam1 controls efficient T-cell trafficking and route of transendothelial migration. Blood 113, 6138–6147 (doi:10.1182/blood-2008-07-167668) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Worthylake RA, Lemoine S, Watson JM, Burridge K. 2001. RhoA is required for monocyte tail retraction during transendothelial migration. J. Cell Biol. 154, 147–160 (doi:10.1083/jcb.200103048) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaibuchi K, Kuroda S, Amano M. 1999. Regulation of the cytoskeleton and cell adhesion by the Rho family GTPases in mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 459–486 (doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.459) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takesono A, Heasman SJ, Wojciak-Stothard B, Garg R, Ridley AJ. 2010. Microtubules regulate migratory polarity through Rho/ROCK signaling in T cells. PLoS ONE 5, e8774 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008774) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baker CM, et al. 2012. Opposing roles for RhoH GTPase during T-cell migration and activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10 474–10 479 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1114214109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cherry LK, Li X, Schwab P, Lim B, Klickstein LB. 2004. RhoH is required to maintain the integrin LFA-1 in a nonadhesive state on lymphocytes. Nat. Immunol. 5, 961–967 (doi:10.1038/ni1103) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Troeger A, Johnson AJ, Wood J, Blum WG, Andritsos LA, Byrd JC, Williams DA. 2012. RhoH is critical for cell–microenvironment interactions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia in mice and humans. Blood 119, 4708–4718 (doi:10.1182/blood-2011-12-395939) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhavsar PJ, Infante E, Khwaja A, Ridley AJ. 2013. Analysis of Rho GTPase expression in T-ALL identifies RhoU as a target for Notch involved in T-ALL cell migration. Oncogene 32, 198–208 (doi:10.1038/onc.2012.42) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellenbroek SI, Collard JG. 2007. Rho GTPases: functions and association with cancer. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 24, 657–672 (doi:10.1007/s10585-007-9119-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boureux A, Vignal E, Faure S, Fort P. 2007. Evolution of the Rho family of Ras-like GTPases in eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 203–216 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msl145) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenwood J, Steinman L, Zamvil SS. 2006. Statin therapy and autoimmune disease: from protein prenylation to immunomodulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 358–370 (doi:10.1038/nri1839) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Demierre MF, Higgins PD, Gruber SB, Hawk E, Lippman SM. 2005. Statins and cancer prevention. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 930–942 (doi:10.1038/nrc1751) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Infante E, Heasman SJ, Ridley AJ. 2011. Statins inhibit T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell adhesion and migration through Rap1b. J. Leukoc. Biol. 89, 577–586 (doi:10.1189/jlb.0810441) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao Y, Dickerson JB, Guo F, Zheng J, Zheng Y. 2004. Rational design and characterization of a Rac GTPase-specific small molecule inhibitor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7618–7623 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0307512101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang QM, Stalker TJ, Gong Y, Rikitake Y, Scalia R, Liao JK. 2012. Inhibition of Rho-kinase attenuates endothelial–leukocyte interaction during ischemia-reperfusion injury. Vasc. Med. 17, 379–385 (doi:10.1177/1358863X12459790) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dong M, Yan BP, Liao JK, Lam YY, Yip GW, Yu CM. 2010. Rho-kinase inhibition: a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Drug Discov. Today 15, 622–629 (doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2010.06.011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodfin A, Voisin MB, Imhof BA, Dejana E, Engelhardt B, Nourshargh S. 2009. Endothelial cell activation leads to neutrophil transmigration as supported by the sequential roles of ICAM-2, JAM-A, and PECAM-1. Blood 113, 6246–6257 (doi:10.1182/blood-2008-11-188375) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]