Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Both oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress (ER stress) are causal events in diabetic embryopathy. We tested whether oxidative stress causes ER stress.

STUDY DESIGN

Wild-type (WT) and superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1)—overexpressing day 8.75 embryos from nondiabetic WT control with SOD1 transgenic male and diabetic WT female with SOD1 transgenic male were analyzed for ER stress markers: C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP), calnexin, eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), protein kinase ribonucleic acid (RNA)-like ER kinase (PERK), binding immunoglobulin protein, protein disulfide isomerase family A member 3, kinases inositol-requiring protein-1α (IRE1α), and the X-box binding protein (XBP1) messenger RNA (mRNA) splicing.

RESULTS

Maternal diabetes significantly increased the levels of CHOP, calnexin, phosphorylated (p)-eIF2α, p-PERK, and p-IRE1α; triggered XBP1 mRNA splicing; and enhanced ER chaperone gene expression in WT embryos. Thus, SOD1 overexpression blocked these diabetes-induced ER stress markers.

CONCLUSION

Mitigating oxidative stress via SOD1 overexpression blocks maternal diabetes—induced ER stress in vivo.

Keywords: diabetic embryopathy, endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative stress, superoxide dismutase 1 transgenic mice

Preexisting maternal diabetes increases the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs).1 In mouse models of diabetic embryopathy, embryos exposed to maternal diabetes during neurulation develop a high rate of NTDs.2–5 Although the mechanism for this is still being elucidated, we do know that maternal diabetes increases the production of several reactive oxygen species5, 6 and simultaneously impairs the activities of endogenous antioxidant enzymes,7 resulting in oxidative stress.

On the other hand, we also know that both dietary antioxidant supplements in vivo8 and antioxidant treatment to cultured embryos in vitro3 can ameliorate the incidence of NTDs in diabetic embryopathy. Indeed, transgenic (Tg) mice overexpressing an endogenous antioxidant, superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), have been shown to have a significantly reduced NTD rate, even under maternal diabetic conditions.9

These multiple lines of experimental evidence support the hypothesis that oxidative stress plays a causal role in the induction of NTDs in diabetic embryopathy. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is likely candidate to play a role in this pathological pathway because it is a critical organelle for the posttranslation modification and correct folding of newly synthesized proteins. A group of ER-resident chaperone proteins, including binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) and calnexin, is essential for maintaining normal ER function. An overload of misfolded and/or aggregated proteins in the ER lumen induces ER dysfunction, which results in ER stress and the induction of cell apoptosis.10

ER stress triggers the unfolded protein response (UPR), which enhances the expression of ER chaperone proteins.11 Elevated ER chaperone proteins thus are indicators of ER stress. In mammalian cells, 2 kinases, the inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α) and the protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), are responsible for the activation of UPR.12,13 IRE1α activation induces messenger RNA (mRNA) splicing of the transcription factor, X-box-binding protein1 (XBP1), and converts this XBP1 into a potent activator that induces the expression of many UPR-responsive genes,14 whereas PERK activation inhibits protein translation and increases the expression of the proapoptotic C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) through the phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α).15

We have recently demonstrated that maternal diabetes induces ER stress, and an ER stress inhibitor, 4-phenylbutyrate, blocks ER stress and thus suppresses the induction of diabetic embryopathy.16 We also have demonstrated that the activation of c-Jun-N-terminal kinase 1 and 2 (JNK1/2) causes diabetic embryopathy.17,18 Indeed, in our laboratory the targeted deletion of either jnk1 or jnk2 gene diminished maternal diabetes—induced ER stress, supporting the causal role of JNK1/2 activation in maternal diabetes—induced ER stress.16 Because our experimental evidence has demonstrated that oxidative stress triggers JNK1/2 activation, we hypothesize that oxidative stress is responsible for ER stress induced by maternal diabetes in diabetic embryopathy.

In vivo SOD1 overexpression in SOD1-Tg mice effectively suppresses maternal diabetes—induced oxidative stress19,20 and significantly ameliorates maternal diabetes—induced NTDs.9 Thus, in the present study, we used SOD1-Tg mice to determine whether reducing oxidative stress by SOD1 overexpression blocks maternal diabetes-induced ER stress and found that SOD1 overexpression diminished ER stress markers, suggesting that oxidative stress causes ER stress in diabetic embryopathy.

Materials and Methods

Animals and reagents

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). SOD1-Tg mice in a C57BL/6J background were revived from frozen embryos by the Jackson Laboratory (stock no. 002298). Streptozotocin (STZ) from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in sterile 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 4.5). Sustained-release insulin pellets were purchased from Linplant (Linshin, CA).

Mouse models of diabetic embryopathy

The procedures for animal use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Our mouse model of diabetic embryopathy has been described previously16, 2012 #654. Briefly, 8 week old wild-type (WT) mice were intravenously injected daily with 75 mg/ kg STZ over 2 days to induce diabetes. Once a level of hyperglycemia indicative of diabetes (≥250 mg/dL) was achieved, insulin pellets were subcutaneously implanted in these diabetic mice to restore euglycemia prior to mating. The mice were then mated with SOD1-Tg male mice at 3:00 PM to generate WT (SOD1 negative) and SOD1-overexpressing embryos.

We designated the morning when a vaginal plug was present as embryonic day (E) 0.5. On E5.5 (day 5.5), insulin pellets were removed to permit frank hyperglycemia (>250 mg/dL glucose level), so the developing conceptuses would be exposed to a hyperglycemic conditions from E7 onward. WT, nondiabetic female mice with vehicle injections and sham operation of insulin pellet implants served as nondiabetic controls. On E8.75, mice were euthanized, and conceptuses were dissected out of the uteri for analysis. E8.75 embryos are suitable models to study the impact of diabetes on embryonic neural tube closure. This is based on the fact that the E8.75 is a key stage of neurulation, and the major part of E8.75 embryos is the developing neural tube. The average litter sizes of nondiabetic and diabetic dams do not differ and are about 5–6 embryos per dam. To avoid any redundancy, data of NTD incidences were not collected because these have been published elsewhere.9

Genotyping of embryos

Embryos from WT diabetic dams mated with SOD1-Tg male mice were genotyped according to the Jackson Laboratory’s protocol using the yolk sac deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described.16,17 Briefly, embryos from different experimental groups were sonicated in 80 μL ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM Na-orthovanadate, 1 mM pheylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1% Triton X-100) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Equal amounts of protein and the Precision Plus protein standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacryamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto Immunobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA).

Membranes were incubated in 5% nonfat milk for 45 minutes and then were incubated for 18 hours at 4°C with the following 5 primary antibodies at 1:1000 to 1:2000 dilutions in 5% nonfat milk: (1) CHOP, (2) calnexin, (3) phosphorylated (p)-eIF2α, (4) p-PERK, and (5) SOD1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). After that, the membranes were exposed to goat antirabbit or antimouse secondary antibodies.

To ensure that equivalent amounts of protein were loaded among samples, membranes were stripped and probed with a mouse antibody against β-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Signals were detected using SuperSignal West Femto maximum sensitivity substrate kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). All experiments were repeated 3 times with the use of independently prepared tissue lysates.

Detection of XBP1 mRNA splicing

The mRNA was reverse transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA) using QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The PCR primers for XBP1 were: forward, 5′-GAA CCAGGAGTTAAGAACACG-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGGCAACAGTGTCAGAGT CC-3′. If no XBP1 mRNA splicing occurred, a 205 bp band was produced. A 205 bp and a 179 bp (main band) bands were produced when XBP1 splicing exists.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from embryos using an RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and reverse transcribed by using the high-capacity cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for BiP, calnexin, IRE1α, eIF2αk3, eIF2αs1, PDIA3, and β-actin were performed using Maxima SYBR Green/ROX quantitative PCR master mix assay (Thermo Scientific). Primers are listed in the Table. RT-PCR and subsequent calculations were performed using a 7700 ABI PRISM sequence detector system (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis

Densitometric data were presented as means ± SE. Three embryos from 3 different dams were used for immunoblotting and 4 embryos for 4 different dams were studied for RT-PCR. One-way ANOVA was performed using SigmaStat 3.5 software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). After using a 1-way ANOVA, Tukey was used for multiple comparison testing to estimate the significance of the results. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 05.

Results

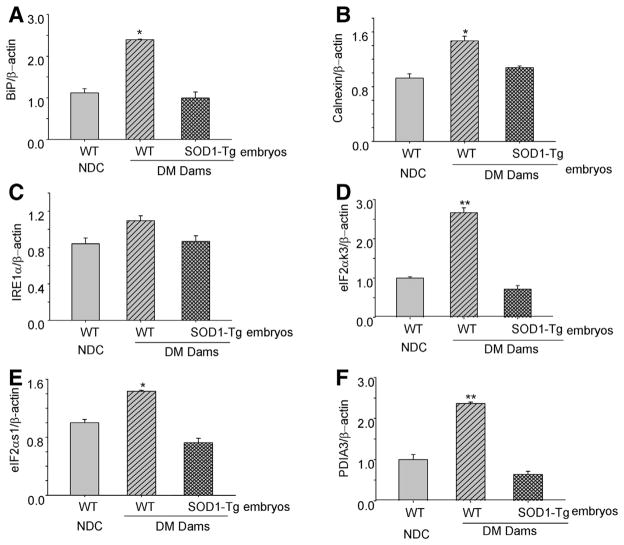

SOD1 overexpression blocks maternal diabetes—induced CHOP and calnexin expression

Elevated levels of CHOP and calnexin are indicative of ER stress. To investigate whether mitigating oxidative stress, using SOD1 transgenic mice, could block maternal diabetes—induced ER stress, we analyzed protein levels of these 2 ER stress markers in E8.75 embryos. Consistent with our previous finding,16 protein levels of CHOP and calnexin were significantly higher in WT embryos from diabetic dams compared with WT embryos of nondiabetic control (NDC) dams (Figure 1). Indeed, protein levels of CHOP and calnexin in SOD1-overexpressing embryos of diabetic dams were significantly lower when compared with WT (non—SOD1-overexpressing) embryos of the same group of diabetic dams, and their ER stress marker levels were comparable with those of the WT embryos of NDC dams (Figure 1). These results demonstrate that maternal diabetes increases the ER stress markers, CHOP and calnexin, via oxidative stress.

FIGURE 1. SOD1 overexpression blocks maternal diabetes—increased CHOP and calnexin expression.

Protein levels of CHOP and calnexin were analyzed in WT embryos from the NDC group and WT embryos and SOD1 overexpressing embryos from the same group of diabetic WT dams mated with SOD1-Tg males. Experiments were repeated 3 times using 3 embryos from 3 different dams. Arrows point to the actual sizes of the targeted proteins. Asterisk indicates significant difference (P < .05) when compared with other groups.

CHOP, superoxide dismutase 1; DM, diabetic mellitus; NDC, nondiabetic control; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; Tg, transgenic; WT, wild-type.

Wang. SOD1 overexpression blocks ER stress in diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013.

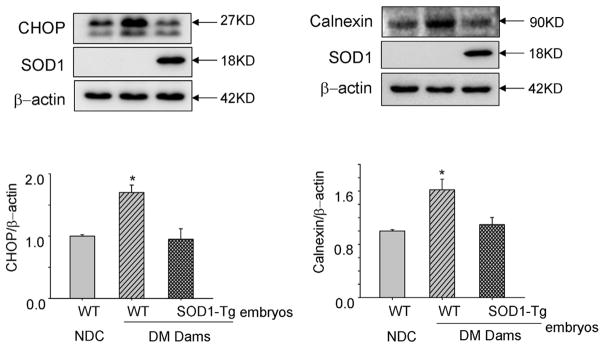

SOD1 overexpression suppresses maternal diabetes-induced phosphorylation of eIF2α, PERK and IRE1α

Increases in the phosphorylation of eIF2α and PERK also is indicative of ER stress, and, previously we demonstrated that maternal diabetes increases the phosphorylation of eIF2α and PERK in embryos, especially during neurulation. 16 To determine whether SOD1 overexpression could block maternal diabetes—induced eIF2α, PERK and IRE1α phosphorylation, we assessed the phosphorylated levels of eIF2α, PERK, and IRE1α in E8.75 embryos. Levels of p-PERK, p-eIF2α, and p-IRE1α in WT embryos of diabetic dams were significantly higher than those in WT embryos of NDC dams and in SOD1-overexpressing embryos of diabetic dams (Figure 2). These results support that suppressing oxidative stress by SOD1 overexpression abrogates maternal diabetes—induced eIF2α, PERK, and IRE1α phosphorylation.

FIGURE 2. SOD1 overexpression blocks maternal diabetes—induced eIF2α and PERK phosphorylation.

Protein levels of p-eIF2α, p-PERK, and p-IRE1α were analyzed in WT embryos from the NDC group and WT embryos and SOD1 overexpressing embryos from the same group of diabetic WT dams mated with SOD1-Tg males. Data in the graph were expressed as the density of phosphorprotein in a group against the density of total protein in the same group. Experiments were repeated 3 times using 3 embryos from 3 different dams. Arrows point to the actual sizes of the targeted proteins. Asterisk indicates P<.05, and double asterisks indicate P<.01 compared with the other 2 groups.

DM, diabetic mellitus; NDC, nondiabetic control; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α; p-IRE1α, phosphorylated inositol-requiring enzyme 1α; p-PERK, phosphorylated protein kinase ribonucleic acid-like ER kinase; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; Tg, transgenic; WT, wild-type.

Wang. SOD1 overexpression blocks ER stress in diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013.

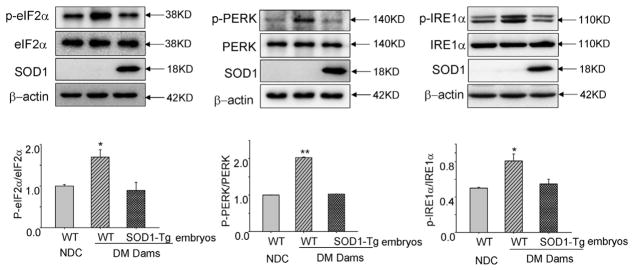

SOD1 overexpression abolishes maternal diabetes—induced XBP1 mRNA splicing

XBP1 mRNA splicing is a robust ER stress indicator. To determine whether SOD1 overexpression can prevent maternal diabetes—induced XBP1 mRNA splicing, WT embryos of NDC dams and WT and SOD1-overexpressing embryos from a same group of diabetic dams were used. WT embryos exposed to maternal diabetes exhibited robust splicing manifested with 2 bands at 205 and 179 bp of the PCR products, whereas WT embryos from NDC dams showed no XBP1 splicing with only 1 band (205 bp) of the PCR products (Figure 3). In SOD1-overexpressing embryos exposed to maternal diabetes, XBP1 splicing was diminished (Figure 3). The results demonstrate that SOD1 overexpression abolishes maternal diabetes—induced XBP1 splicing.

FIGURE 3. SOD1 overexpression abrogates maternal diabetes—induced XBP1 mRNA splicing.

XBP1 mRNA splicing in WT embryos of the NDC group, WT embryos, and SOD1 overexpressing embryos from diabetic WT dams mated with SOD1-Tg males is shown. Arrows point to the actual size of the bands.

DM, diabetic mellitus; NDC, nondiabetic control; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; Tg, transgenic; WT, wild-type; XBP1, X-box binding protein.

Wang. SOD1 overexpression blocks ER stress in diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013.

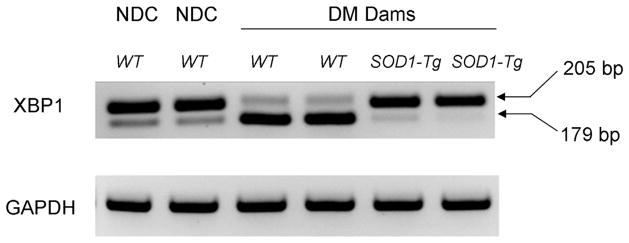

SOD1 overexpression reverses maternal diabetes-increased ER chaperone gene expression

ER stress-triggered UPR response induces ER chaperone gene expression. Consistent with our previous finding,16 maternal diabetes significantly increased the expression of 5 ER chaperone genes: (1) BiP, (2) calnexin, (3) eIF2αk3, (4) eIF2αs1, and (5) PDIA3 (Figure 4). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the increased expression of these 5 ER chaperone genes induced by diabetes was diminished in SOD1-overexpressing embryos of diabetic dams (Figure 4). Thus, SOD1 overexpression inhibited maternal diabetes-increased ER chaperone gene expression. However, one of the ER chaperone genes, IRE1α, did not differ in WT embryos of NDC dams and WT embryos and SOD1-overexpressing embryos of diabetic dams (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. SOD1 overexpression suppresses maternal diabetes—induced ER chaperone gene expression.

A, The mRNA levels of BiP, B, calnexin, C, IRE1α, D, eIF2αk3, E, eIF2αs1, F, and PDIA3 were analyzed in WT embryos from the NDC group, WT embryos and SOD1-overexpressing embryos from diabetic WT dams mated with SOD1-Tg males. Four embryonic samples (n = 4) from 4 different dams of each group were analyzed for real-time polymerase chain reaction. Asterisk indicates P < .05 and double asterisks indicate P < .01 compared with the other 2 groups.

BiP, binding immunoglobulin protein; DM, diabetic mellitus; eIF2αs1, eukaryotic initiation factor 2α; eIF2αk3, XX; IRE1α, inositol-requiring enzyme 1α; NDC, nondiabetic control; PDIA3, XX; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; Tg, transgenic; WT, wild-type.

Wang. SOD1 overexpression blocks ER stress in diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013.

Comment

Our previous studies have demonstrated that SOD1 overexpression in SOD1 transgenic mice abolishes maternal diabetes—induced oxidative stress by inhibiting lipid peroxidation and nitrosative stress19,20 and thus prevents maternal diabetes—induced NTD formation. 9 Overexpression of the antioxidant enzyme SOD1 is an effective way to investigate the causal relationship between oxidative stress and ER stress. Indeed, evidence in other systems supports the hypothesis that oxidative stress causes ER stress. For example, in vitro studies using human hepatocytes have demonstrated that the potent reactive oxygen species, hydrogen peroxide, is able to induce ER stress.21

In addition, we have demonstrated that maternal diabetes induces oxidative stress in embryonic tissues,5,22,23 and our previous studies using antioxidants3, 24 or ER stress inhibitors16 have determined that oxidative stress and ER stress are 2 causal events in maternal diabetes— induced NTD formation. This present study, which uses SOD1 overexpressing transgenic mice, provides direct evidence that maternal diabetes—induced oxidative stress is responsible for ER stress in diabetic embryopathy.

Extremely high-dosage SOD1 overexpression has been linked to the neural disorders seen in Down syndrome.25 The level of SOD1 expression in our SOD1-Tg mice appears modestly high and does not exhibit any neurological disorders and thus serves as a control in the study of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caused by human SOD1 point mutation containing a substitution of glycine to alanine at position 93.26

Clinical studies have demonstrated that the degree of maternal hyperglycemia correlates with the rate and severity of birth defects.27,28 Whole rodent embryos cultured under high-glucose conditions exhibit NTDs similar to those observed in human fetuses exposed to maternal diabetes.18 We also have demonstrated that high glucose in vitro induces ER stress in cultured embryos. Therefore, hyperglycemia can induce ER stress in diabetic embryopathy.

Cells respond to ER stress through a set of pathways known as UPR, whose prolonged activation triggers cell apoptosis.29,30 In mammalian cells, there are 3 distinct UPR signaling pathways that involve the activation of PERK, IRE1α, and activating transcription factor-6, respectively.30,31 Consistent with our previous finding,16 in the present study, we detected the activation of key intermediates in all 3 of these pathways in WT embryos exposed to maternal diabetes. Specifically, our results show that the protein levels of CHOP, calnexin, and the phosphorylated levels of eIF2α, PERK, and IRE1α are significantly increased in WT embryos of the diabetic group compared with those of WT embryos of the nondiabetic group.

SOD1 overexpression suppresses maternal diabetes—induced UPR responses, providing strong evidence that SOD1 overexpression blocks maternal diabetes—induced ER stress markers. PERK increases the expression of proapoptotic CHOP through eIF2α phosphorylation. 15 CHOP, in turn, mediates the proapoptotic effect of ER stress.10

Excess apoptosis is the central hypothesis in diabetic embryopathy. Our previous studies have demonstrated that both SOD1 overexpression and ER stress inhibition block caspase-mediated apoptosis in embryos exposed to maternal diabetes.16,17,19 Because SOD1 overexpression suppresses CHOP expression and apoptosis, the role of CHOP in maternal diabetes—induced apoptosis and malformations warrants further investigation.

We analyzed ER stress markers in whole embryonic levels. However, in our previous study, using electronic microscopy, we observed stressed ER only in neuroepithelial cells but not in other types of cells in the developing embryos. 16 Thus, ER stress in neuroepithelial cells triggers apoptosis of these cells, leading to NTD formation. Indeed, an ER stress inhibitor, 4-PBA, prevented high glucose in vitro-induced NTDs.

In the current study, we used embryos at E8.75, a critical time of neurulation but before NTDs are manifested. Therefore, NTD rates are not assessed. Nevertheless, our previous studies have demonstrated that maternal diabetes significantly increases NTD rates in E10.5 embryos,16,17 and SOD1 overexpression in transgenic mice reduces NTD formatiom.9 In vivo studies using mouse models of reduced ER stress such as gene deletions of ER stress markers need to be performed in future studies to determine whether ER stress is responsible for NTD formation in embryos exposed to diabetes during neurulation.

Studies have suggested that during cardiogenesis, at a late time window (E10.5 to E13.5) than that of neurulation, ER stress also occurs in the developing heart, resulting in heart defects.32 Thus, maternal diabetes induces ER stress in different organs at different time points, resulting in organ-specific defects. Our study reveals ER stress in neurulation-stage embryos, which develop to NTDs after diabetic exposure.

XBP1 is required for ER expansion and directs transcription of a core group of genes that are involved in constitutive maintenance of ER function in all cell types.31 Under the ER stress condition, phosphorylated IRE1α induces the excision of a 26 bp fragment from the XBP1 mRNA (205 bp) by an unconventional splicing event and thus generates a 179 bp mRNA splicing variant, which is translated to a potent transcriptional activator that induces many UPR-responsive genes.14 Our previous study has demonstrated that there is a robust XBP1 splicing event in embryos exposed to maternal diabetes, whereas the JNK1/2 deletion abolishes this process.16

In the present study, we show that maternal diabetes—induced XBP1 mRNA splicing is diminished in SOD1-overexpressing embryos. Because maternal diabetes—induced oxidative stress is responsible for JNK1/2 activation,22,23,33 SOD1 may suppress XBP1 mRNA splicing through the blockade of JNK1/2 activation.

Under ER stress, the UPR response and the 179 bp XBP1 splicing variant collectively induce the expression of ER chaperone genes. Indeed, we found that the mRNA levels of BiP, calnexin, eIF2αs1, eIF2αk3, and PDIA3 are all significantly increased in WT embryos of the diabetic group and that SOD1 overexpression abrogates the expression of these ER chaperone genes. Interestingly, we did not observe any changes in IRE1α mRNA expression. Because the phosphorylation of IRE1α is an early and important indicator of ER stress, our finding on the elevation of phosphorylated IRE1α in diabetic embryopathy underscores the importance of IRE1α phosphorylation in mediating the UPR response under ER stress.

The ER chaperone gene expression profile observed in the current study is in agreement with our previous findings. 16,17 There are 2 possibilities of how SOD1 overexpression blocks maternal diabetes—induced ER chaperone gene expression. First, SOD1 diminishes ER chaperone gene expression by blocking XBP1 mRNA splicing, thus, preventing the generation of a potent transcription activator that is essential for ER chaperone gene induction. Second, SOD1 blocks ER chaperone gene expression via JNK1/2 inhibition because JNK1/2 activation induces an array of transcription factors that may induce ER chaperone gene expression.

A previous report has shown that ER stress can induce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and thus leads to oxidative stress.34 In diabetic embryopathy, increased glucose flux damages the integrity of the mitochondria, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction, 6 which is the source of ROS. Because SOD1 overexpression blocks maternal diabetes—induced ER stress markers and ER chaperone gene expression, it supports the hypothesis that oxidative stress leads to ER stress in maternal diabetes. It is unknown whether SOD1 overexpression can suppress the ROS production in stressed ER lumen. Thus, future studies need to determine whether stressed ER under maternal diabetic conditions is also a source of ROS. Maternal diabetes—induced oxidative stress and ER stress may promote each other and form a vicious cycle, leading to excess apoptosis in target tissues of the developing embryo.

Our study reveals a new pathway, oxidative stress—ER stress, in the pathogenesis of diabetic embryopathy. This discovery will aid our design toward effective preventions against this disease. Our previous animal studies have shown that antioxidants including multivitamin and natural polyphenols are effective in the prevention of diabetic embryopathy.1,3,24,33,35,36 Because human clinical trials on antioxidants, particularly vitamins, have failed to achieve any protective effects against any human diseases, the effectiveness of antioxidants on human diabetic embryopathy is in question.36,37 Nevertheless, because of the obesity epidemic38–48 and its associated type 2 diabetes,49 diabetes-induced birth defects are urgent public health problems affecting both the mother and her fetus.50–52

Our mechanistic studies on ER stress will provide the basis for the development of ER stress inhibitors as new interventions in diabetic embryopathy. If the ER stress inhibitors are proven to be safe to human pregnancy, they also can be used in other pregnancy-related pathologies such as preeclampsia with manifested ER stress.53

TABLE.

Primer list for RT-PCR

| Gene | Sense | Antisense |

|---|---|---|

| BiP | ACTTGGGGACCACCTATTCCT | CTCAGGATAATGGTAGCCATGTC |

| Calnexin | ATGGAAGGGAAGTGGTTACTGT | GCTTTGTAGGTGACCTTTGGAG |

| IRE1α | ACTGTGGATCCAGGAAGTGG | GCGGAGGACAAGGAAATGTA |

| eIF2αk3 | AGTCCCTGCTCGAATCTTCCT | TCCCAAGGCAGAACAGATATACC |

| eIF2αs1 | ATGCCGGGGCTAAGTTGTAGA | AACGGATACGTCGTCTGGATA |

| PDIA | CGCCTCCGATGTGTTGGAA | CAGTGCAATCCACCTTTGCTAA |

| β-Actin | GTGACGTTGACATCCGTAAAGA | GCCGGACTCATCGTACTCC |

| XBP1 splicing | GAACCAGGAGTTAAGAACACG | AGGCAACAGTGTCAGAGTCC |

Wang. SOD1 overexpression blocks ER stress in diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01DK083243 and R56 DK095380 (P.Y.).

We are grateful to Ms Hua Li and Drs Xuezheng Li and Cheng Xu (all at the University of Maryland School of Medicine) for their technical support.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Reprints not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Correa A, Gilboa SM, Besser LM, et al. Diabetes mellitus and birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:237.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang P, Reece EA. Role of HIF-1alpha in maternal hyperglycemia-induced embryonic vasculopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:332.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang P, Li H. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate ameliorates hyperglycemia-induced embryonic vasculopathy and malformation by inhibition of Foxo3a activation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:75.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao Y, Zhao Z, Eckert RL, Reece EA. Protein kinase Cbeta2 inhibition reduces hyperglycemia-induced neural tube defects through suppression of a caspase 8-triggered apoptotic pathway. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:226.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang P, Cao Y, Li H. Hyperglycemia induces inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression and consequent nitrosative stress via c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:185.e5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang X, Borg LA, Eriksson UJ. Altered metabolism and superoxide generation in neural tissue of rat embryos exposed to high glucose. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E173–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.1.E173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sivan E, Lee YC, Wu YK, Reece EA. Free radical scavenging enzymes in fetal dysmorphogenesis among offspring of diabetic rats. Teratology. 1997;56:343–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199712)56:6<343::AID-TERA1>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sivan E, Reece EA, Wu YK, Homko CJ, Polansky M, Borenstein M. Dietary vitamin E prophylaxis and diabetic embryopathy: morphologic and biochemical analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:793–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)80001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagay ZJ, Weiss Y, Zusman I, et al. Prevention of diabetes-associated embryopathy by overexpression of the free radical scavenger copper zinc superoxide dismutase in transgenic mouse embryos. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1036–41. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szegezdi E, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Samali A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:880–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ron D, Hubbard SR. How IRE1 reacts to ER stress. Cell. 2008;132:24–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–4. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee K, Tirasophon W, Shen X, et al. IRE1-mediated unconventional mRNA splicing and S2P-mediated ATF6 cleavage merge to regulate XBP1 in signaling the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev. 2002;16:452–66. doi: 10.1101/gad.964702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zinszner H, Kuroda M, Wang X, et al. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 1998;12:982–95. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Xu C, Yang P. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1/2 and endoplasmic reticulum stress as interdependent and reciprocal causation in diabetic embryopathy. Diabetes. 2013;62:599–608. doi: 10.2337/db12-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, Weng H, Xu C, Reece EA, Yang P. Oxidative stress-induced JNK1/2 activation triggers proapoptotic signaling and apoptosis that leads to diabetic embryopathy. Diabetes. 2012;61:2084–92. doi: 10.2337/db11-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang P, Zhao Z, Reece EA. Involvement of c-Jun N-terminal kinases activation in diabetic embryopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:749–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weng H, Li X, Reece EA, Yang P. SOD1 suppresses maternal hyperglycemia-increased iNOS expression and consequent nitrosative stress in diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:448.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Weng H, Reece EA, Yang P. SOD1 overexpression in vivo blocks hyperglycemia-induced specific PKC isoforms: substrate activation and consequent lipid peroxidation in diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:84.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanada S, Harada M, Kumemura H, et al. Oxidative stress induces the endoplasmic reticulum stress and facilitates inclusion formation in cultured cells. J Hepatol. 2007;47:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang P, Zhao Z, Reece EA. Activation of oxidative stress signaling that is implicated in apoptosis with a mouse model of diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:130.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang P, Zhao Z, Reece EA. Blockade of c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation abrogates hyperglycemia-induced yolk sac vasculopathy in vitro. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:321.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reece EA, Wu YK, Zhao Z, Dhanasekaran D. Dietary vitamin and lipid therapy rescues aberrant signaling and apoptosis and prevents hyperglycemia-induced diabetic embryopathy in rats. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:580–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groner Y, Elroy-Stein O, Avraham KB, et al. Cell damage by excess CuZnSOD and Down’s syndrome. Biomed Pharmacother. 1994;48:231–40. doi: 10.1016/0753-3322(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–5. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greene MF, Hare JW, Cloherty JP, Benacerraf BR, Soeldner JS. First-trimester hemoglobin A1 and risk for major malformation and spontaneous abortion in diabetic pregnancy. Teratology. 1989;39:225–31. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420390303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller E, Hare JW, Cloherty JP, et al. Elevated maternal hemoglobin A1c in early pregnancy and major congenital anomalies in infants of diabetic mothers. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:1331–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198105283042204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyce M, Bryant KF, Jousse C, et al. A selective inhibitor of eIF2alpha dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science. 2005;307:935–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1101902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, et al. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134:743–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Z. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in maternal diabetes-induced cardiac malformations during critical cardiogenesis period. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2012;95:1–6. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reece EA, Wu YK. Prevention of diabetic embryopathy in offspring of diabetic rats with use of a cocktail of deficient substrates and an antioxidant. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:790–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70602-1. discussion 797–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim HR, Lee GH, Cho EY, Chae SW, Ahn T, Chae HJ. Bax inhibitor 1 regulates ER-stress-induced ROS accumulation through the regulation of cytochrome P450 2E1. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1126–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reece EA, Wu YK, Wiznitzer A, et al. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acid prevents malformations in offspring of diabetic rats. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:818–23. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Correa A, Gilboa SM, Botto LD, et al. Lack of periconceptional vitamins or supplements that contain folic acid and diabetes mellitus-associated birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:218.e1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Hassan SS. Supplementation with vitamins C and E during pregnancy for the prevention of preeclampsia and other adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:503.e1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gunatilake RP, Perlow JH. Obesity and pregnancy: clinical management of the obese gravida. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:106–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Catalano PM, Hauguel-De Mouzon S. Is it time to revisit the Pedersen hypothesis in the face of the obesity epidemic? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:479–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedderson MM, Williams MA, Holt VL, Weiss NS, Ferrara A. Body mass index and weight gain prior to pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:409.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herring SJ, Oken E, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Weight gain in pregnancy and risk of maternal hyperglycemia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:61.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hull HR, Thornton JC, Ji Y, et al. Higher infant body fat with excessive gestational weight gain in overweight women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:211.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynch AM, Eckel RH, Murphy JR, et al. Prepregnancy obesity and complement system activation in early pregnancy and the subsequent development of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:428.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cardozo ER, Neff LM, Brocks ME, et al. Infertility patients’ knowledge of the effects of obesity on reproductive health outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:509.e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolfe KB, Rossi RA, Warshak CR. The effect of maternal obesity on the rate of failed induction of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:128.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halloran DR, Marshall NE, Kunovich RM, Caughey AB. Obesity trends and perinatal outcomes in black and white teenagers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:492.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khatibi A, Brantsaeter AL, Sengpiel V, et al. Prepregnancy maternal body mass index and preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:212.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mornar S, Chan LN, Mistretta S, Neustadt A, Martins S, Gilliam M. Pharmacokinetics of the etonogestrel contraceptive implant in obese women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:110.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stuebe AM, Landon MB, Lai Y, et al. Maternal BMI, glucose tolerance, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:62.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yee LM, Cheng YW, Inturrisi M, Caughey AB. Effect of gestational weight gain on perinatal outcomes in women with type 2 diabetes mellitus using the 2009 Institute of Medicine guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:257.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roeder HA, Moore TR, Ramos GA. Insulin pump dosing across gestation in women with well-controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:324.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yanit KE, Snowden JM, Cheng YW, Caughey AB. The impact of chronic hypertension and pregestational diabetes on pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:333.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loset M, Mundal SB, Johnson MP, et al. A transcriptional profile of the decidua in pre-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:84.e1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]