Abstract

Background

We consider the strength of the relationship between types of conduct problems in early life and pattern of alcohol use during adolescence.

Methods

Children from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a UK birth-cohort, had their level of conduct problems assessed repeatedly from 4 to 13 years using the maternal report Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Developmental trajectories derived from these data were subsequently related to (i) patterns of alcohol use from 13 to 15 years, and (ii) hazardous alcohol used at age 16.

Results

Boys with ‘Adolescent Onset’ or ‘Early Onset Persistent’ conduct problems were much more likely to be high frequency drinkers between 13 and 15 years (OR 5.00 95% CI = [2.4, 10.6] and 3.9 95% CI = [2.1, 7.3] respectively) compared with those with Low or ‘Childhood Limited’ conduct. Adolescent Onset/Early Onset Persistent girls also had greater odds of this high-alcohol frequency drinking pattern (2.67 [1.4, 5.0] and 2.14 [1.2, 4.0] respectively). Associations were more moderate for risk of hazardous alcohol use at age 16. Compared to 32% among those with low conduct problems, over 40% of young people classified as showing Adolescent Onset/Early Onset Persistent conduct problems were drinking hazardously (OR 1.52 [1.09, 2.11] and 1.63 [1.22, 2.18] respectively).

Conclusions

Whilst persistent conduct problems greatly increase the risk of adolescent alcohol problems, the majority of adolescents reporting hazardous use at age 16 lack such a history. It is important, therefore, to undertake alcohol prevention among all young people as a priority, as well as target people with manifest conduct problems.

Keywords: ALSPAC, Conduct problems, Alcohol use, Adolescence, Trajectory

1. Introduction

Early and hazardous drinking in adolescence is associated with adult alcohol consumption and problems (Hingson et al., 2006; Pitkanen et al., 2005), as well as with problems during adolescence (Fergusson and Horwood, 2000). It has been argued that during childhood and in adolescence the adverse consequences of drinking alcohol far outweigh the modest number of positive impacts such as social and emotional coping (Newbury-Birch et al., 2008). The UK government recommends that an alcohol-free childhood is the healthiest and best option; and that if children drink alcohol, it should not be until at least the age of 15. Furthermore, it is recommended that 15–17 year olds should consume alcohol on no more than one day a week and never exceed recommended adult daily limits (CMO, 2009). Young people in the UK report some of the highest rates of alcohol consumption and hazardous drinking in Europe (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, 2006; Hibell et al., 2012). Recent trends suggest that monthly alcohol use may have decreased for young people over 16 and increased for those under 16 but with little change in trends in heavy episodic (binge) drinking and little to no difference between girls and boys with over 50% reporting heavy episodic drinking (Hibell et al., 2012; Smith and Foxcroft, 2009). Average weekly alcohol consumption among women aged 16–19 nearly trebled from ~5 units in 1992 to 14 units per week in 2002 and the gap between men and women has narrowed (Goddard, 2007). Consistent with these data, we recently found that nearly 15% of both boys and girls aged 13–15 were classified as “high” frequency drinkers, and that by age 16 over 1 in 3 of boys and girls were defined as hazardous drinkers based on reported Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores (Heron et al., 2012).

There are a large number of potential environmental and genetic influences on problematic alcohol use (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, 2006; Horn et al., 2007; Rutter, 2002). The strongest and most consistent evidence is seen in relation to antecedent conduct problems or antisocial behaviour (Dodge et al., 2009; Glantz and Leshner, 2000; Rutter, 2002; Zucker, 2008). There is now extensive evidence that childhood/early-adolescent conduct problems are associated with increased risk for alcohol use/abuse (Costello, 2007). Recent evidence from UK samples suggests that these associations follow a dose–response relationship with severity of externalising/conduct symptoms, and are robust to controls for a variety of socio-demographic confounds (Goodman, 2010).

Given the heterogeneity inherent in most measures of antisocial behaviour, there is clearly the need for more refined characterizations of the characteristics of antisocial behaviour most associated with alcohol use. Most work in this area has focused on refining the nature of the behavioural/trait characteristics most strongly associated with vulnerability to alcohol problems (see Zucker et al. (2011) for a review). However, developmental variations may also be important, especially in studies of childhood risk. One highly influential approach to ‘parsing’ the heterogeneity of conduct problems in this way is Moffitt’s developmental taxonomy (Moffitt, 1993; Moffitt et al., 1996). This proposed that the overall ‘pool’ of antisocial young people is made up of two distinct groups, defined by age at onset, and differentiable in terms of both aetiology and course. On the one hand, childhood onset problems are thought to stem from individually-based risks (neuropsychological and temperamental/genetic) which, in conjunction with adverse early rearing conditions, go on to produce the problematic personality traits that maintain long-term antisocial lifestyles (Odgers et al., 2008). ‘Adolescence-limited’ conduct problems, by contrast, are thought to be relatively free of such individual risks, whereby individuals become involved in delinquent behaviours primarily as a result of environmental influences. Much adolescent onset antisocial behaviour is seen as normative and time-limited, declining naturally as young people mature into adult roles – though involvement in some associated problems might act as ‘snares’, trapping young people into on-going difficulties. In contrast, most early onset problems were initially thought likely to have a poor long-term prognosis; a range of empirical studies have now confirmed that this only applies to a sub-set of early-onset individuals, and that a third, ‘childhood limited’ sub-group is found in many samples.

The lack of refined measures of antisocial behaviour and how they relate to harms in adolescence and adulthood has been highlighted by Zucker and others (Englund et al., 2008; Horn et al., 2007; Maggs et al., 2008; Zucker, 2008; Zucker et al., 2011). In this paper we test whether different trajectories of antisocial behaviour assessed six times between ages 4 and 13 years have a different relationship with patterns of alcohol exposure from age 13 to 15 years and hazardous drinking at age 16, and we assess the proportion of hazardous drinking that is associated with early conduct problems and thereby how important targeting conduct problems is in relation to prevention of excessive alcohol use among young people.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample comprised participants from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), an on-going population-based study investigating a wide range of environmental and other influences on the health and development of children (Boyd et al., 2013; Fraser et al., 2012; Golding et al., 2001). Pregnant women resident in the former Avon Health Authority (Bristol) in south-west England with an estimated date of delivery between 1 April 1991 and 31 December 1992 were invited to take part, resulting in a ‘core’ cohort of 14,541 pregnancies and 13,973 singletons/twins alive at 12 months of age. The primary source of data collection was via self-completion questionnaires administered to the mother, her partner and the ALSPAC offspring. Since the age of seven years, the cohort has been invited to annual ‘focus’ clinic for a variety of hands-on assessments. More information on the study is available at http://www.alspac.bris.ac.uk. All aspects of the study were reviewed and approved by the ALSPAC Law and Ethics Committee, which is registered as an Institutional Review Board. Approval was also obtained from the National Health Service Local Research Ethics Committees.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome #1 Patterns of alcohol frequency in early adolescence

Latent Class Analysis has recently been used to describe patterns of alcohol frequency in early adolescence (13–15 years) using three-category ordinal measures of self-reports of current drinking frequency (None/Occasional [has had a drink in the last 6 months but does not drink weekly]/Weekly use; Heron et al., 2012). Heterogeneity in response was summarised by a three-class model consisting of low (53.2%), medium (32.5%) and high-frequency (14.2%) alcohol use. Whilst girls were very slightly overrepresented in the medium and high frequency classes, there was little evidence of an association between gender and alcohol frequency.

2.2.2. Outcome #2 Alcohol problems at age 16

In a postal questionnaire administered at age 16 (median age 16 years 7 months) the young people completed the self-report version of the ten-item AUDIT (Babor et al., 2001). Here we used a cutoff of 7/8 to indicate non-hazardous (total score < 8), and hazardous (total score 8 or more). Respondents answering “No” to the stem question on alcohol use since the age of 15 were assigned a score of zero and retained in further analyses as members of the non-hazardous group.

2.2.3. Main exposure conduct problem trajectories

The derivation of trajectories of conduct problems with these data has previously been reported (Barker and Maughan, 2009). Latent Class Growth Analysis models were applied to six binary indicators of conduct problems derived from maternal reports on the conduct problem sub-scale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ: Goodman, 2001; Goodman and Scott, 1999) completed between child ages 4 and 13 years. The items cover temper tantrums, obedience, fighting/bullying, lying/cheating and stealing. The derived sum-score was dichotomized at the threshold 4/5 (Goodman, 2001) for computation of the trajectory classes. The four resulting trajectories were described as ‘Low’ (64.3%), ‘Childhood Limited’ (CL: 14.7%), ‘Adolescent Onset’ (AO: 11.8%) and ‘Early Onset Persistent’ (EOP: 9.2%). Boys were over-represented in all non-low conduct problem classes however there was only a marked difference in gender ratio for the EOP group.

2.2.4. Early life risk factors that may confound the CP/alcohol relationship

A number of early life factors that may confound the relationship between conduct problems and alcohol hazardous use were selected on the basis that they have been shown previously to be risk factors for CP and/or alcohol use. Appropriate variables were selected from questionnaires administered to the young person’s parents between enrolment (early in antenatal period) and 47 months after the birth (i.e., up until the first measure of conduct problems). Demographic variables: comprised sex, housing tenure (coded as owned/mortgaged, privately rented, subsidised housing rented from council/housing-association), parity (coded as whether study child is 1st/2nd/3rd or subsequent child in the family), crowding status (coded as a value greater than one for the ratio of number of residents to number of rooms in house) and maternal educational attainment (coded as no high school qualifications, high school, beyond high school). Maternal alcohol use: maternal daily alcohol use (yes indicating that alcohol was consumed daily at either two, eight, 21 or 33 months postnatal).

2.3. Statistical methods

Mixture models with four and three classes respectively have been shown to be optimal for describing patterns of conduct problems and alcohol frequency in this dataset. For the current analysis we did not seek to reaffirm these findings. A series of one-stage models were derived in which the association between conduct problem trajectories and alcohol frequency patterns were examined at the same time as the estimation of the pair of mixture models. The alcohol outcome was then additionally regressed on the early life risk factors listed above in order to adjust for their confounding effect. As a second set of analyses the alcohol frequency patterns spanning 13–15 years was replaced with the binary AUDIT measure (hazardous/non-hazardous alcohol use) collected at age 16. All models were estimated using Mplus version 6.0 (Muthén and Muthén, 2010).

2.3.1. Gender interaction models

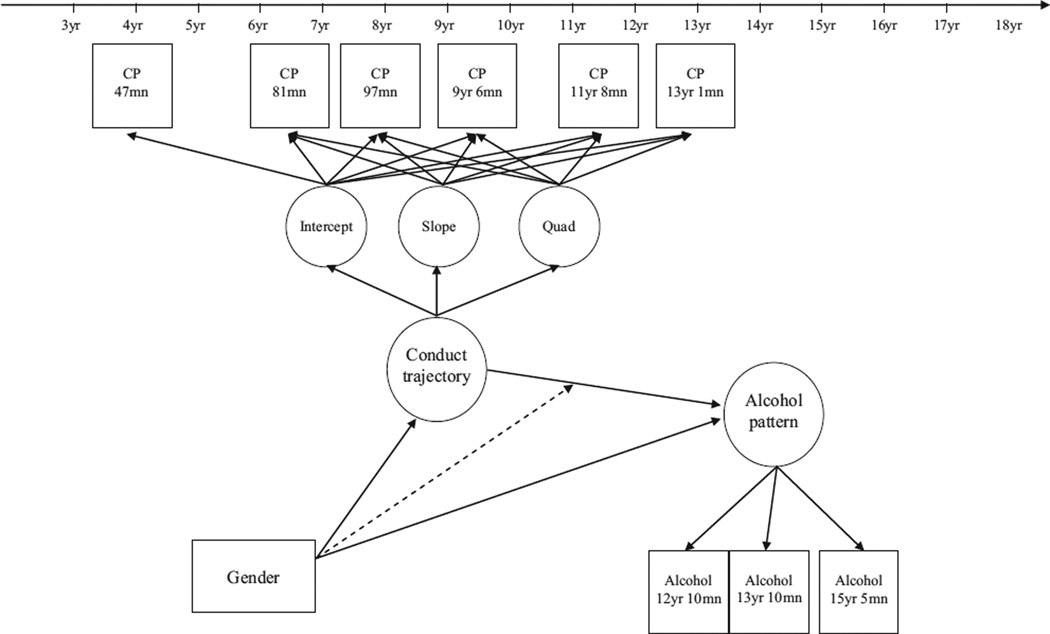

Previous work has reported that gender-invariant models for both conduct problems and alcohol frequency provided an adequate fit to these data. These were models where the measurement model was constrained but the prevalence of each latent class was allowed to vary between boys and girls. In the current study we sought to test whether the effect of conduct problems on alcohol frequency may differ between boys and girls, e.g., whether having a particular pattern of conduct problems impacts on alcohol uptake differentially between the genders. To this end, two models were compared, firstly a model which constrained the measurement models for conduct and alcohol frequency to be gender-invariant but allowed the effect of conduct on alcohol to differ (see Fig. 1), and secondly a model where all aspects apart from the class-distributions for conduct and alcohol frequency were constrained. As these models are not nested we relied on a comparison of BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) values to determine the better-fitting model. Again this was repeated using the binary AUDIT outcome.

Fig. 1.

Path diagram of gender interaction model for relationship between conduct problems (CP) and alcohol frequency.

2.3.2. Missing data

The original models for conduct problems and alcohol frequency utilised Full Information Maximum Likelihood to permit the inclusion of those respondents with a partially complete set of repeated measures. The conduct problem trajectory model was based on those with up to three missing values (n = 7218) whilst the model of alcohol patterns included respondents with one or two missing values (n = 7100). Main analyses of the association between these two measures focussed on the sample of n = 5659 with information on both latent variables (equivalent to the requirement of 1+ alcohol measure and 3+ conduct problems measures). The incorporation of covariates led to a reduction from this starting figure, with a sample of 5340 cases having measures of alcohol pattern, conduct problem trajectory plus the confounders examined with the inclusion of maternal alcohol use reducing the sample further to 4788. Similarly, main analyses of the association between conduct problems and hazardous alcohol use at age 16 focussed on the sample of n = 4021. In this instance, the incorporation of covariates led to a reduction to 3817 and then 3482

3. Results

3.1. Sample demographics

The descriptive statistics shown in Table 1 are restricted to the subsample of ALSPAC who have conduct-problem trajectory data available. The demographics of this subsample have been described previously (Barker and Maughan, 2009). The left hand side of Table 1 describes the cases providing additional information necessary for the final analytical model of alcohol-patterns. The majority of this dropout was due to lack of alcohol data in adolescence. There is strong evidence of social patterning apparent among the cases present in the final model with inclusion being more likely for respondents with more-highly-educated mothers, and from less crowded, mortgaged/owned houses. There were slightly weaker effects for gender and maternal alcohol use with girls more likely to provide outcome data, and surprisingly, offspring whose mothers drank alcohol on a daily basis in the first few postnatal years. The remaining columns of Table 1 illustrate the association between the chosen potential confounders and both conduct-problem trajectory and alcohol-pattern (each derived by modal class assignment). There is a slight discordance in the measures that are most strongly related to each of CP and alcohol. Whilst education, gender, housing tenure and home overcrowding are most strongly related to CP class, only tenure and crowding are also strongly associated with alcohol pattern. The strongest risk factors for alcohol are parity and maternal alcohol use, neither of which infers a particularly great risk of a non-normative CP classification.

Table 1.

Estimated association between potential confounders and (i) inclusion in final adjusted model for alcohol patterns, (ii) CP trajectory class membership, (iii) alcohol frequency of use pattern.

| (i) In final adjusted model | (ii) CP trajectory class | (iii) Alcohol frequency of use pattern | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | X2, p | Low | CL | AO | EOP | X2, p | Low freq | Medium freq | High freq | X2, p | |

| Parity | ||||||||||||

| 1st born | 1025 (31.1%) | 2270 (68.9%) | X2 = 4.69 p = 0.096 | 2322 (70.5%) | 377 (11.4%) | 302 (9.2%) | 294 (8.9%) | X2 = 12.0 p = 0.061 | 1668 (62.6%) | 763 (28.6%) | 233 (8.8%) | X2 = 45.1 p < 0.001 |

| 2nd born | 799 (31.8%) | 1712 (68.2%) | 1776 (70.7%) | 310 (12.4%) | 207 (8.2%) | 218 (8.7%) | 1090 (56.0%) | 595 (30.6%) | 261 (13.4%) | |||

| 3rd or greater | 424 (34.5%) | 806 (65.5%) | 845 (68.7%) | 159 (12.9%) | 90 (7.3%) | 136 (11.1%) | 500 (54.0%) | 296 (32.0%) | 130 (14.0%) | |||

| Maternal education | ||||||||||||

| A-level or higher | 816 (26.6%) | 2254 (73.4%) | X2 = 133.4 p < 0.001 | 2250 (73.3%) | 334 (10.9%) | 256 (8.3%) | 230 (7.5%) | X2 = 49.6 p < 0.001 | 1503 (59.2%) | 768 (30.2%) | 270 (10.6%) X2 = 8.10 p = 0.088 | |

| O-level | 813 (32.4%) | 1694 (67.6%) | 1764 (70.4%) | 303 (12.1%) | 213 (8.5%) | 227 (9.1%) | 1180 (60.1%) | 547 (27.8%) | 238 (12.1%) | |||

| <O-level | 650 (43.6%) | 840 (56.4%) | 960 (64.4%) | 212 (14.2%) | 130 (8.7%) | 188 (12.6%) | 597 (56.3%) | 334 (31.5%) | 129 (12.2%) | |||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1285 (35.3%) | 2352 (64.7%) X2 = 9.11 p = 0.003 | 2478 (68.1%) | 474 (13.0%) | 306 (8.4%) | 379 (10.4%) | X2 = 20.6 p < 0.001 | 1681 (60.3%) | 792 (28.4%) | 313 (11.2%) | X2 = 5.25 p = 0.072 | |

| Female | 1145 (31.2%) | 2436 (68.0%) | 2583 (72.1%) | 401 (11.2%) | 310 (8.7%) | 287 (8.0%) | 1652 (57.5%) | 892 (31.1%) | 329 (11.5%) | |||

| Housing tenure | ||||||||||||

| Mortgaged/owned | 1724 (29.3%) | 4161 (70.7%) X2 = 140.8 p < 0.001 | 4253 (72.3%) | 680 (11.6%) | 484 (8.2%) | 468 (8.0%) | X2 = 97.8 p < 0.001 | 2748 (58.2%) | 1447 (30.6%) | 527 (11.2%) | X2 = 13.8 p = 0.008 | |

| Privately rented | 243 (43.5%) | 316 (56.5%) | 358 (64.0%) | 76 (13.6%) | 59 (10.6%) | 66 (11.8%) | 266 (64.4%) | 101 (24.5%) | 46 (11.1%) | |||

| Subsidised rented | 306 (49.6%) | 311 (50.4%) | 354 (57.4%) | 96 (15.6%) | 57 (9.2%) | 110 (17.8%) | 248 (60.6%) | 103 (25.2%) | 58 (14.2%) | |||

| Home overcrowding | ||||||||||||

| Up to 1 person/room | 2072 (30.8%) | 4652 (69.2%) | X2 = 34.9 p < 0.001 | 4758 (70.8%) | 812 (12.1%) | 565 (8.4%) | 589 (8.8%) | X2 = 21.7 p < 0.001 | 3099 (58.5%) | 1601 (30.2%) | 597 (11.3%) | X2 = 11.2 p = 0.004 |

| >1 person/room | 126 (48.1%) | 136 (51.9%) | 163 (62.2%) | 27 (10.3%) | 29 (11.1%) | 43 (16.4%) | 120 (64.9%) | 36 (19.5%) | 29 (15.7%) | |||

| Maternal daily alcohol | ||||||||||||

| No | 1309 (24.8%) | 3964 (75.2%) | X2 = 6.96 p =0.008 | 3732 (70.8%) | 629 (11.9%) | 450 (8.5%) | 462 (8.8%) | X2 = 1.47 p = 0.688 | 2520 (60.6%) | 1177 (28.3%) | 461 (11.1%) | X2 = 17.0 p < 0.001 |

| Yes | 219 (21.0%) | 824 (79.0%) | 753 (72.2%) | 123 (11.8%) | 78 (7.5%) | 89 (8.5%) | 452 (53.0%) | 1466 (33.9%) | 573 (13.1%) | |||

Figures for CP trajectory class and alcohol frequency pattern are derived using modal-class assignment and hence these data only approximate the associations estimated in the final one-step model. Samples sizes vary depending on the availability of data on each potential confounder.

3.2. Conduct problems and alcohol patterns 13–15

Table 2 describes the relationship between the conduct problem trajectory classes and alcohol frequency patterns separately in girls and boys. Alcohol frequency is treated as a three category multinomial outcome with low-frequency as the reference; conduct problem trajectories are modelled as a four-category exposure, with consistently low conduct problems as the reference.

Table 2.

Gender interaction model for relationship between Conduct Problems and Alcohol frequency of use (n = 5659).

| Alcohol frequency pattern | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low alcohol frequency | Medium alcohol frequency | High alcohol frequency | ||||

| Row % | Row % | OR [95% CI] | Row % | OR [95% CI] | ||

| Males (n = 2786) | Low | 59.6 | 31.2 | – | 9.2 | – |

| Childhood Limited | 61.2 | 24.0 | 0.75 [0.38, 1.45] | 14.8 | 1.57 [0.78, 3.17] | |

| Adolescent Onset | 41.0 | 27.5 | 1.28 [0.57, 2.89] | 31.5 | 5.00 [2.36, 10.57] | |

| Early Onset Persistent | 51.3 | 18.1 | 0.67 [0.31, 1.46] | 30.7 | 3.89 [2.08,7.25] | |

| Females (n = 2873) | Low | 55.0 | 33.7 | – | 11.4 | – |

| Childhood Limited | 56.4 | 26.4 | 0.77 [0.38, 1.54] | 17.1 | 1.47 [0.74, 2.92] | |

| Adolescent Onset | 38.1 | 49.8 | 2.14 [1.15, 3.96] | 12.1 | 1.53 [0.51, 4.59] | |

| Early Onset Persistent | 51.2 | 20.5 | 0.65 [0.28, 1.51] | 28.3 | 2.67 [1.42, 5.00] | |

Multinomial odds ratios shown are with reference to the low-alcohol frequency outcome category.

For males, those with ‘Adolescent Onset’ (AO) or ‘Early Onset Persistent’ (EOP) conduct problems had a markedly higher odds of being a high frequency drinker: AO (OR = 5.00, 95% CI = [2.4, 10.6]); EOP (OR = 3.9, 95% CI = [2.1, 7.3]); in contrast, there is little evidence of a difference in alcohol frequency pattern between those with low and childhood limited conduct problems. The pattern is similar, although slightly less marked, for girls, with girls with EOP conduct problems having greater odds of the high-alcohol frequency pattern (OR = 2.67, 95% CI = [1.42, 5.00]) and those with AO conduct problems having greater odds of medium alcohol frequency (OR = 2.14, 95% CI = [1.15, 3.96]). Again there was little difference between the low and ‘Childhood Limited’ (CL) groups. Though the association between conduct problems and alcohol was slightly stronger for boys, there was little indication of any interaction between gender and conduct problems and the more parsimonious model in which the effect of conduct problems on alcohol was constrained to be equal across the sexes was superior based on BIC values – 55012.8 versus 55036.7. All subsequent analyses of alcohol use at 13–15 therefore combined males and females.

Table 3 shows the estimated association between conduct problems and alcohol frequency pattern at ages 13–15 years for the full sample collapsed over gender. High alcohol frequency was nearly three times as likely among young people classified as having AO (OR = 2.99, 95% CI = [1.8, 4.9]) or EOP conduct problems (OR = 2.93, 95% CI = [1.8, 4.8]) compared to young people in the low conduct problems group. There was little evidence of a difference in alcohol frequency between the low problem and CL groups (OR = 0.7, 95% CI = [0.43, 1.29] and OR = 1.4, 95% CI = [0.9, 2.3] for medium and high alcohol frequency respectively) and weak evidence that the risk of being in the medium alcohol frequency class was higher for AO conduct problems (OR = 1.68, 95% CI = [1.01, 2.8]) compared to low conduct problems. Despite this association, the vast majority (~65%) of high-frequency alcohol users have a history of low or childhood limited conduct problems. The adjustment for potential confounders occurring early in life did not alter markedly the effect estimates between conduct problems and alcohol patterns.

Table 3.

Adjusted models for CP and patterns of alcohol use from 13 to 15 years

| Low alcohol frequency (53.9%) |

Medium alcohol frequency (30.5%) | High alcohol frequency (157%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row % | Row % | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted 1 OR | Adjusted 2 OR | Row % | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted 1 OR | Adjusted 2 OR | ||

| Conduct problem trajectory | Low (64.8%) | 56.1 | 32.2 | 1.00 ref | 1.00 ref | 1.00 ref | 11.7 | 1.00 ref | 1.00 ref | 1.00 ref |

| Childhood Limited (14.8%) | 58.1 | 24.8 | 0.74 [0.43, 1.29] | 0.69 [0.35, 1.35] | 0.53 [0.21, 1.34] | 17.2 | 1.41 [0.89, 2.26] | 1.24 [0.79, 1.97] | 1.27 [0.73, 2.22] | |

| Adolescent Onset (11.2%) | 38.6 | 37.3 | 1.68 [1.01, 2.79] | 2.00 [1.09, 3.68] | 2.05 [1.09, 3.85] | 24.1 | 2.99 [1.84, 4.86] | 3.34 [1.82, 6.12] | 3.18 [1.63, 6.21] | |

| Early Onset Persistent (9.2%) | 50.2 | 19.1 | 0.66 [0.36, 1.22] | 0.54 [0.26, 1.13] | 0.56 [0.26, 1.21] | 30.7 | 2.93 [1.81, 4.75] | 2.44 [1.49, 3.99] | 2.66 [1.34, 5.26] | |

Multinomial odds ratios shown are with reference to the low-alcohol frequency outcome category.

Percentages describing class distributions correspond to the sample of 5659 used for the unadjusted analysis.

Unadjusted model (n = 5659) –main effect of conduct problems trajectory on alcohol frequency pattern.

Adjusted model 1 (n = 5340) –adjusted for gender, housing tenure, over-crowding, parity and maternal education.

Adjusted model 2 (n = 4788) –additionally adjusted for pre-4y maternal alcohol use.

3.3. Conduct problems and hazardous drinking at 16

The association between conduct problems trajectories and hazardous/ harmful drinking at age 16 is shown in Table 4. Again, BIC values gave no evidence of a gender interaction. Over 40% of young people classified as showing AO and EOP conduct problems were drinking hazardously (OR = 1.52, 95% CI = [1.09, 2.11] and OR = 1.63, 95% CI = [1.22, 2.18] respectively) compared to those with consistently low levels of conduct problems. There was no evidence of more hazardous drinking among those in the CL conduct problems trajectory compared to those low in conduct problems throughout (OR 1.17, 95% CI = [0.9, 1.6]). Approximately 78% of hazardous alcohol users have a history of low or childhood limited conduct problems. Adjustment for confounders did not markedly change these findings.

Table 4.

Adjusted models for CP and hazardous alcohol use at age 16

| Unadjusted OR | Adjusted 1 OR | Adjusted 2 OR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage reporting hazardous use % | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | ||

| Conduct problem trajectory | Low (67.5%) | 32.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Childhood Limited (14.9%) | 35.6 | 1.17 [0.89, 1.55] | 1.18 [0.88, 1.60] | 1.20 [0.89, 1.62] | |

| Adolescent Onset (10.9%) | 41.7 | 1.52 [1.09, 2.11] | 1.50 [1.06, 2.13] | 1.39 [0.94, 2.06] | |

| Early Onset Persistent (6.8%) | 43.4 | 1.63 [1.22, 2.18] | 1.60 [1.18, 2.18] | 1.52 [1.09, 2.11] | |

Percentages describing CP class distribution correspond to the sample of 4021 used for the unadjusted analysis.

Unadjusted model (n = 4021) –main effect of conduct problems trajectory on hazardous alcohol use at age 16 (34.3% of sample).

Adjusted model 1 (n = 3817) – adjusted for gender, housing tenure, over-crowding, parity and maternal education.

Adjusted model 2 (n = 3482) –additionally adjusted for pre-4y maternal alcohol use.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key findings

Heavier alcohol use during the early-mid teens and hazardous/ harmful use at age 16 was associated with both early onset persistent (EOP) and adolescent onset (AO) conduct problems. There was a stronger relationship between conduct problems and high frequency alcohol use at ages 13–15 than for the more distal measure of hazardous drinking at age 16. There was no evidence for an increased risk of frequent or hazardous alcohol use among young people with childhood limited (CL) conduct problems compared to those with low levels of conduct problems from early childhood. The effect estimates remained similar after adjustment for several confounders. There was some suggestion that the relationship between conduct problems and high frequency alcohol use was stronger among boys than girls aged 13–15, beyond this, however, alcohol-conduct problem associations did not appear to differ by gender.

4.2. Limitations

We acknowledge a number of limitations with the study. First, there are missing observations in the exposure, outcome or covariates which means that the total number of cases used in the analyses vary. Missing observations in ALSPAC are socially patterned, and are more likely among both young people with conduct problems and greater alcohol consumption (Barker and Maughan, 2009; Heron et al., 2012; Macleod et al., 2008). Full Information Maximum Likelihood could be used with the unadjusted models to account for missing conduct problem observations. However, observations are dropped with the introduction of other covariates – which may add bias. There are no generally accepted methods for the use of multiple-imputation with latent classes and mixture modelling (Heron et al., 2011). Nonetheless our analyses were not underpowered and previous analyses of alcohol use in ALSPAC using multiple-imputation suggest that frequencies are unaffected (Melotti et al., 2011, 2013). Second, there was little attenuation of the alcohol-use/conduct problem relationship after adjusting for confounders. As we have demonstrated that these covariates are strong predictors of dropout, these conditional models should in part be addressing the problem of non-response bias in addition to their main function of assessing confounding. It is possible that there are other confounders/covariates which we have not included in the current analyses that may explain the observed alcohol/conduct relationship, though we have used common covariates shown in previous studies to be associated both with the exposure and the outcome. Our previous analyses found no evidence of an association between gender and patterns of alcohol use and only slight increase in EOP conduct problems between boys and girls.

One aim of the current paper was to examine whether the effect of conduct problems on alcohol may differ across the genders. We did not find any evidence to support the hypothesis. Alcohol consumption is based on self-reported data as biological markers are unreliable (Lees et al., 2012); there maybe some misclassification of the level of drinking which may introduce non-differential bias. In addition, our measures of alcohol use start at age 13, though some children may be exposed to alcohol before age 13 and so may overlap slightly with the antisocial behaviour trajectories, the alcohol trajectories are less likely to be affected as they measure level of drinking rather than simply onset. However, as the latter trajectories extend from age 4 to 13 we think it highly unlikely that there would be reverse causation between alcohol exposure and antisocial behaviour. Furthermore, the majority of the conduct-problem items are not typical of the sort of conduct one would immediately associate with alcohol use (e.g., rowdyness/ vandalism). Finally, our alcohol trajectory and the AUDIT measure at age 16 primarily assess alcohol consumption and may miss some important “alcohol related harms” such as affray and dangerous use of machinery that contribute to classifications of alcohol abuse and dependence. However, excessive drinking was our focus and also is the driver of these other harms.

4.3. Comparison with other literature and implications

In the UK, studies of conduct problems in early life and later alcohol use have tended to rely upon a single measure of conduct problems/antisocial behaviour, and examined some form of dose response associations with alcohol consumption (Goodman, 2010; Maggs et al., 2008). Given the repeated measures of conduct problems available in ALSPAC, we were able to construct a more developmentally-oriented characterisation of the risk phenotype, consistent with Moffitt’s developmental taxonomy (Barker and Maughan, 2009; Moffitt, 1993). First, we showed that although some early childhood conduct problems are associated with increased risk for early and problematic alcohol use, these links are by no means inevitable. Indeed, in our sample they were confined to those young people whose antisocial behaviour was both early and persistent; those whose early behavioural difficulties remitted across the childhood years were at no higher risk of alcohol problems than their peers with consistently low conduct problem profiles. Second, we show that there is little difference in alcohol consumption between the two types of antisocial young people (Early Onset Persistent and Adolescent Onset) whose conduct problems are consistently high, or rising, as they enter their teens. It is proposed that there are different aetiologies to these two types of conduct problem/antisocial behaviour: with “early onset persistent problems” stemming from individually-based risks (neuropsychological and temperamental/genetic) in conjunction with adverse early rearing conditions (Odgers et al., 2008); and “adolescent-limited problems”, by contrast, more influenced by affiliation with deviant peers. Equally, it is possible that hazardous alcohol use in young people also has similarly contrasting aetiological pathways (Dick et al., 2009; Kendler et al., 2011, also Dick et al. (paper under review)). However, to test such hypotheses will require genetic analyses of phenotypes that combine information on CP and alcohol in order to distinguish these potentially different pathways, which may not be possible if the phenotypes are based solely on alcohol consumption.

It is hypothesised that much of adolescent-onset antisocial behaviour is seen as normative and time-limited, declining naturally as young people mature into adult roles – but involvement in heavy alcohol use may act as a ‘snare’, trapping young people into on-going difficulties (Moffitt and Caspi, 2001; Odgers et al., 2008). Fergusson and colleagues also have suggested that alcohol problems are associated with antisocial behaviour (Fergusson and Horwood, 2000), which could be due to reverse causation or that alcohol consumption is a marker of antisocial behaviour rather than a mediator of its persistence. These hypotheses can only be tested in future studies.

In contrast to some past studies we did not find marked differences between boys and girls in the association between conduct problems and alcohol use. A variety of factors may have contributed here: the relatively high rates of alcohol use among girls in our sample; temporal trends in antisocial behaviour among girls; and the lack of marked gender differences in the trajectory of conduct problems (Barker and Maughan, 2009; Moffitt et al., 1996). We found that the more proximal the outcome (high frequency alcohol use from 13–15 rather than drinking at 16) the stronger the association. This will need to be tested in additional studies, as it may reflect a waning or differential influence of conduct problems over time; or alternatively may be an indication that conduct problems operate within an accumulation or cascade of risks with additional mediating factors required for older age groups, or could be due to measurement error (Dodge et al., 2009; Kendler et al., 2011; Phillips and Smith, 1992).

It is important to note, however, that the majority of both high-frequency mid-adolescent drinkers and hazardous drinkers at age 16 were among young people with low or childhood limited conduct problems. The stark implication for the prevention of alcohol misuse among adolescents is that even though conduct problems increase the risk of alcohol consumption and are a potential target for alcohol prevention; conduct problems alone are likely to cause a modest proportion of high frequency and hazardous drinkers during adolescence. For example, by age 16 less than 10% of hazardous drinkers could be attributed to early persistent or adolescent onset conduct problems. Our findings are consistent, therefore, with recommendations that wider population and structural interventions are required to reduce alcohol related harm in young people (Viner et al., 2012).

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses.

Role of funding source

The UK Medical Research Council (Grant: 74882) the Wellcome Trust (Grant: 076467) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. This publication is the work of the authors and Jon Heron and Matt Hickman will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper. JH is supported by the UK Medical Research Council (Grants G0800612 and G0802736) and this work was also supported in part by NIH Grant RO1 AA018333.

The funders listed had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

M. Hickman, G. Lewis and K.S. Kendler contributed to the overall scientific direction of the project. M. Hickman, B. Maughan, D.M. Dick and J. Heron developed the manuscript. M. Hickman, B. Maughan and D.M. Dick managed the literature searches and summaries of previous work. J. Heron performed the statistical analyses. All authors assisted with writing and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Pathways to Problems. London: Home Office; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, Monteiro M, editors. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. The alcohol use disorders identification test. In: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. [Google Scholar]

- Barker ED, Maughan B. Differentiating early-onset persistent versus childhood-limited conduct problem youth. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009;166:900–908. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J, Lawlor DA, Fraser A, Henderson J, Molloy L, Ness A, Ring S, Davey Smith G. Cohort profile: the ‘children of the 90s’-the index offspring of the avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013;42:111–127. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CMO. London: Department of Health; 2009. [accessed (18.07.12)]. Draft Guidance on the Consumption of Alcohol by Children and Young People from the Chief Medical Officers of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Retrieved from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_110256.pdf, Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/69FIZlrQv">Retrieved from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/ digitalasset/dh_110256.pdf, Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/69FIZlrQv. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ. Psychiatric predictors of adolescent and young adult drug use and abuse: what have we learned? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl. 1):S97–S99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Latendresse SJ, Lansford JE, Budde JP, Goate A, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Role of GABRA2 in trajectories of externalizing behavior across development and evidence of moderation by parental monitoring. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009;66:649–657. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone PS, Lansford JE, Miller S, Pettit GS, Bates JE. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2009;74:vii–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund MM, Egeland B, Oliva EM, Collins WA. Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: a longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction. 2008;103:23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Alcohol abuse and crime: a fixed-effects regression analysis. Addiction. 2000;95:1525–1536. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951015257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser A, Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K, Boyd A, Golding J, Davey Smith G, Henderson J, Macleod J, Molloy L, Ness A, Ring S, Nelson SM, Lawlor DA. Cohort profile: the avon longitudinal study of parents and children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012;42:97–110. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz MD, Leshner AI. Drug abuse and developmental psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000;12:795–814. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard E. Estimating Alcohol Consumption from Survey Data: Updated Method of Converting Volumes to Units, 37. London: ONS HMSO; 2007. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Golding J, Pembrey M, Jones R. ALSPAC – the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. I. Study methodology. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2001;15:74–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. Substance use and common child mental health problems: examining longitudinal associations in a British sample. Addiction. 2010;105:1484–1496. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Scott S. Comparing the strengths and difficulties questionnaire and the child behavior checklist: is small beautiful? J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1999;27:17–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1022658222914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J, Hickman M, Macleod J, Munafo MR. Characterizing patterns of smoking initiation in adolescence: comparison of methods for dealing with missing data. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011;13:1266–1275. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J, Macleod J, Munafo MR, Melotti R, Lewis G, Tilling K, Hickman M. Patterns of alcohol use in early adolescence predict problem use at age 16. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47:169–177. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibell B, Guttormsson U, Ahlström S, Balakireva O, Bjarnason T, Kokkevi A, Kraus L. The 2011 ESPAD Report. Substance Use Among Students in 36 European Countries. Stockholm, Sweden: The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn G, Barnes J, Brownsword R, Deakin JFW, Gilmore IMH, Iversen L, Robbins T, Taylor E, Wolff J. Academy of Medical Sciences. London: 2007. [Accessed: 18.07.12]. Brain Science, Addiction and Drugs. Retrieved from http://www.acmedsci.ac.uk/p99puid126.html. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/69FIqtEir. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner C, Dick DM. Predicting alcohol consumption in adolescence from alcohol-specific and general externalizing genetic risk factors, key environmental exposures and their interaction. Psychol. Med. 2011;41:1507–1516. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000190X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees R, Kingston R, Williams TM, Henderson G, Lingford-Hughes A, Hickman M. Comparison of ethyl glucuronide in hair with self-reported alcohol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47:267–272. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod J, Hickman M, Bowen E, Alati R, Tilling K, Smith GD. Parental drug use early adversities, later childhood problems and children’s use of tobacco and alcohol at age 10: birth cohort study. Addiction. 2008;103:1731–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Patrick ME, Feinstein L. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol use and problems in adolescence and adulthood in the National Child Development Study. Addiction. 2008;103(Suppl. 1):7–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotti R, Heron J, Hickman M, Macleod J, Araya R, Lewis G. Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use and early socioeconomicposition: the ALSPAC birth cohort. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e948–e955. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotti R, Lewis G, Hickman M, Heron J, Araya R, Macleod J. Early life socio-economic position and later alcohol use: birth cohort study. Addiction. 2013;108:516–525. doi: 10.1111/add.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol. Rev. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Dev. Psychopathol. 2001;13:355–375. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Silva P, Stanton W. Childhood-onset versus adolescent-onset antisocial conduct problems in males: natural history from ages 3 to 18 years. Dev. Psychopathol. 1996;9:399–424. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6th. ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Newbury-Birch D, Gilvarry E, McArdle P, Venkateswaran R, Stewart S, Walker J, Avery L, Beyer F, Brown N, Jackson K, Lock C, McGovern R, Kaner E. Impact of alcohol consumption on young people: a systematic review of reviews. DCSF. [Accessed 18.07.12];2008 Retrieved from http://alcoholeducationtrust.org/resources/facts/DCSFalcoholandyoungpeoplefindngs.pdf. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/69FIPkrpC. [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Poulton R, Sears MR, Thomson WM, Caspi A. Female and male antisocial trajectories: from childhood origins to adult outcomes. Dev. Psychopathol. 2008;20:673–716. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AN, Smith GD. Bias in relative odds estimation owing to imprecise measurement of correlated exposures. Stat. Med. 1992;11:953–961. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780110712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen T, Lyyra AL, Pulkkinen L. Age of onset of drinking and the use of alcohol in adulthood: a follow-up study from age 8–42 for females and males. Addiction. 2005;100:652–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. 4th ed. New York: Blackwell Publishing; 2002. Substance Use and Abuse: Causal Pathway Considerations Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; pp. 455–463. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA, Foxcroft DR. Drinking in the UK:An Exploration of Trends. Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, Currie C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012;379:1641–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Anticipating problem alcohol use developmentally from childhood into middle adulthood: what have we learned? Addiction. 2008;103(Suppl. 1):100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Heitzeg MM, Nigg JT. Parsing the undercontrol/disinhibition pathway to substance use disorders: a multilevel developmental problem. Child Dev. Perspect. 2011;5:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]