Abstract

Objective

Candida remains an important cause of late-onset infection in preterm infants. Mortality and neurodevelopmental outcome of extremely low birthweight (ELBW) infants enrolled in the Candida study was evaluated based on infection status.

Study design

ELBW infants born at NICHD Neonatal Research Network (NRN) centers between March 2004 and July 2007 screened for suspected sepsis were eligible for inclusion in the Candida study. Primary outcome data for neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) or death were available for 1317/1515 (90%) of the infants enrolled in the Candida study. The Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID)-II or the BSID-III was administered at 18 months adjusted age. A secondary comparison with 864 infants registered with NRN enrolled during the same cohort never screened for sepsis and therefore not eligible for the Candida study was performed.

Results

Among ELBW infants enrolled in the Candida study, 31% with Candida and 31% with late-onset non-Candida sepsis had NDI at 18 months. Infants with Candida sepsis and/or meningitis had an increased risk of death and were more likely to have the composite outcome of death and/or NDI compared with uninfected infants in adjusted analysis. Compared with infants in the NRN registry never screened for sepsis, overall risk for death were similar but those with Candida infection were more likely to have NDI (OR 1.83 (1.01,3.33, p=0.047).

Conclusion

In this cohort of ELBW infants, those with infection and/or meningitis were at increased risk for death and/or NDI. This risk was highest among those with Candida sepsis and/or meningitis.

Keywords: Candida, Neonatal sepsis, Neurodevelopmental and Prematurity

Although premature infants remain at increased risk for adverse neurodevelopmental (ND) outcome, it is increasingly clear that this risk is modified by a variety of neonatal morbidities, including neonatal infection. Candida has consistently remained an important pathogen associated with late-onset neonatal sepsis (LOS), affecting approximately 7% of very low birthweight (VLBW) infants prior to hospital discharge.(1–4) Improved understanding of the morbidity and mortality associated with Candida infection is needed to interpret previous data and to consider new prevention and treatment strategies.

Adverse ND outcomes in preterm infants have been associated with LOS due to various bacterial pathogens (4, 5); however, data regarding outcome of infants with Candida infection have been somewhat variable. Friedman et al reported outcomes of 46 extremely low birthweight (ELBW) infants < 1000grams with Candida sepsis/meningitis compared with ELBW peers.(6) Periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) (26% vs 12%; p=0.06), severe retinopathy of prematurity (22% vs 9%, p=0.04), chronic lung disease (CLD) (100% vs 34%; p=.0001), and adverse neurologic outcomes at 2 years of age (60% vs 35%, p=0.005) were more common among those with Candida infection.(6) Stoll et al compared ND outcomes of ELBW infants with Candida infection with those infected with bacterial pathogens and those who were uninfected.(4) The 105 infants with Candida were more likely to have moderate to severe cerebral palsy (CP) and neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) compared with uninfected infants; however, these differences were not statistically significant after adjustment for other contributing variables. Benjamin et al reported ND outcome of 320 ELBW infants with Candida sepsis and/or meningitis, of whom 293 had sepsis only, 14 had sepsis and meningitis and 13 had meningitis only compared with peers without Candida infection. (7) Candida infected neonates had lower Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II (BSID-II) scores, were more likely to have moderate/severe CP, NDI, blindness and hearing impairment compared with those without Candida infection.(7)

The Neonatal Research Network (NRN) of the Eunice Kennedy Shiver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) performed a prospective observational study of ELBW infants evaluated for sepsis to develop predictive models for Candida infection.(8) This analysis evaluates mortality and neurodevelopmental outcome at 18–22 months adjusted age in ELBW infants from this cohort with Candida infection, compared with infants with other LOS pathogens and to uninfected infants.

Methods

Extremely low birthweight infants (401–1000 grams birthweight) born between March 2004 and July 2007 at participating NICHD NRN hospitals who were alive at 72 hours and subsequently screened for sepsis were eligible for inclusion in the Candida study which was a prospective observational study to develop predictive models to estimate the probability of invasive candidiasis based on laboratory and clinical variables.(8) This analysis evaluates the primary outcomes of death or NDI based on infection status for these infants. Infants with early onset sepsis (EOS), congenital anomalies, congenital infection and those lost to follow-up were excluded from analysis. Based on study design, the Candida study only included infants screened for sepsis, therefore to address potential bias introduced by using a higher at risk comparison group, we performed a secondary analysis comparing outcomes of uninfected ELBW infants enrolled during the same study period in the NRN registry. (9) IRB approval was obtained at each site and separate informed consents were obtained for the Candida Observational Study and the Neurodevelopmental Follow-Up Study.

Neonatal and maternal data were collected systematically from birth until hospital discharge, transfer, death or 120 days postnatal age and infant data were collected at the 18–22 month follow-up visit. Infection status was established based on positive cultures obtained at each study site. Additional clinical data were collected with each suspected episode of sepsis, including the use and timing of antibiotic and antifungal therapy.

Chronic Lung Disease was defined by the use of supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks postmenstrual age. Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) was defined by modified Bells Stage IIA or greater (10) and treated for ≥ 5 days. Early onset sepsis (EOS) within 72 hours of birth and late onset sepsis (LOS) after 72 hours were defined by a positive blood culture and antibiotic therapy for ≥ 5 days. Clinical infection was defined as suspected sepsis with negative cultures but administration of antibiotics for ≥ 5 days. Meningitis was defined as a positive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture for Candida or bacterial organisms. Grades 3 and 4 intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), as defined by Papile (11) were considered severe for this analysis. Periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) was defined as the presence of cystic echolucencies in the periventricular white matter by ultrasonography.

Infants had a comprehensive neurodevelopmental evaluation at 18–22 months adjusted age. Certified examiners who were unaware of infection status performed a standardized neurosensory examination. Functional motor impairment was defined based on the Palisano Gross Motor Functional Classification score.(12) Children evaluated prior to October 1, 2007 (Epoch 1) were administered the cognitive and motor scales of the BSID-II Revised and those evaluated after this date (Epoch 2) were administered the cognitive and language scales of the BSID-III. Both instruments are normed based on a representative sample of children from the United States and standardized to a score of 100 ± 15 (mean ± standard deviation (SD).(13, 14) The composite language score is a sum of the receptive and expressive language scores on the BSID-III which are based on a scale of 1–19 and converted to a standardized score with a mean 100 ± 15 SD. Even though the fundamental structure of these two instruments is similar, changes in age adjusted item sets and instrument design limit the ability to combine or directly compare results from these two instruments. Therefore, categorical values of neurodevelopmental outcome based on these predefined definitions were used to compare patients in Epochs 1 and 2. Differences in the definition of neurodevelopmental impairment for the two epochs are outlined in Table I.

Table 1.

Neurodevelopmental Impairment Definitions and Outcomes by Epoch at 18 Months Adjusted Age of Children Enrolled in Candida Study who Survived to Follow-Up

| Variable | Epoch 1 (N=544) | Epoch 2 (N=522) |

|---|---|---|

| Neurodevelopmental Impairment Definitions | ||

| Child has any of the following: | ||

| Neurological | Moderate to severe cerebral palsy with GMFCS level ≥ 2 | Moderate to severe cerebral palsy with GMFCS level ≥ 2 |

| Development | Bayley II MDI < 70 or PDI < 70 | Bayley III cognitive < 70 or GMFCS level ≥ 2 |

| Vision | Bilateral blindness with no functional vision | Visual acuity < 20–200 bilateral |

| Hearing | Bilateral amplification for permanent hearing loss | Permanent hearing loss that does not permit the child to understand directions of examiner and communicate despite amplification |

| Neurodevelopmental Outcomes | Epoch 1 N (%) |

Epoch 2 N (%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodevelopmental Impairment | 222 (41) | 59 (11) | < .001 |

| Visually impaired | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | .948 |

| Hearing impaired | 16 (3) | 17 (3) | .783 |

| Moderate/severe cerebral palsy | 42 (8) | 19 (4) | .004 |

| Any cerebral palsy | 85 (16) | 49 (9) | .002 |

| Gross motor function level ≥ 2 | 44 (8) | 27 (5) | .056 |

| MDI | |||

| < 70 | 189 (35) | -- | -- |

| 70–85 | 166 (31) | -- | -- |

| > 85 | 187 (35) | -- | -- |

| PDI | |||

| < 70 | 127 (24) | -- | -- |

| 70–85 | 136 (25) | -- | -- |

| > 85 | 277 (51) | -- | -- |

| Cognitive | |||

| < 70 | -- | 42 (8) | -- |

| 70–85 | -- | 167 (32) | -- |

| > 85 | -- | 313 (60) | -- |

| Language | |||

| < 70 | -- | 82 (16) | -- |

| 70–85 | -- | 159 (31) | -- |

| > 85 | -- | 269 (53) | -- |

Patients in the Candida study were divided into four groups based on infection status: (1) Candida (blood or CSF culture positive for Candida); (2) LOS-Other (blood or CSF culture positive for bacterial pathogen but not Candida); (3) Clinical infection and (4) Uninfected (no history of infection or NEC) Additionally, ELBW infants enrolled in the NRN ELBW registry never treated for suspected or confirmed sepsis who were therefore ineligible for inclusion in the Candida study, comprised the NRN Registry-Uninfected group.

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate analyses were performed to compare demographic and morbidity profiles by infection status and epoch, using chi-square tests for categorical variables and analyses of variance for continuous variables. We estimated the incidence of three outcomes by infection status: (1) death, (2) NDI, and (3) death and/or NDI. We conducted multilevel logistic regression modeling to compare the risk of adverse outcomes (death and/or NDI) for children in each of the infection groups (Candida infection, LOS-Other, Clinical infection, Uninfected-Candida, and Uninfected NRN Registry) after adjusting for clustering of children within research centers and controlling for potential confounders including: epoch, sex, birth weight, race, maternal education, postnatal corticosteroids, NEC, and IVH/PVL. Five percent of children had missing data for maternal education, therefore multiple imputation was used to impute missing values for this variable to preserve the sample size for the regression models.

RESULTS

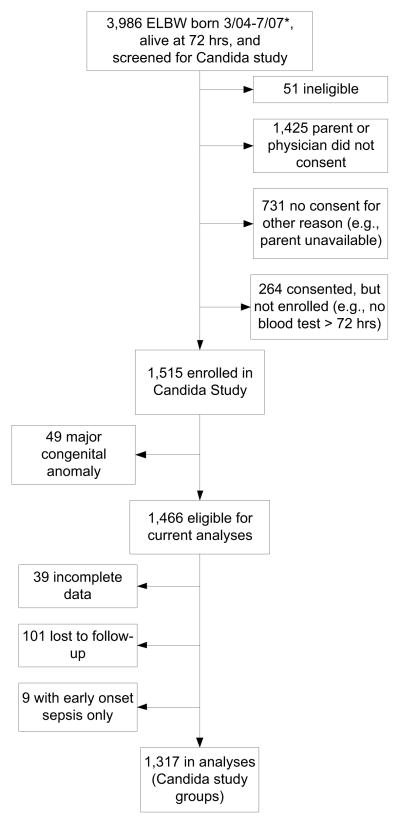

During the study period, 6,493 ELBW infants were born in 19 participating centers, of whom, 5,252 were alive at 72 hours. The Candida study included 1,515 ELBW infants who were screened for sepsis.(8) Data on the primary outcomes of death and/or neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) were available for 1317 (90%) of the eligible infants enrolled in the Candida study (Figure; available at www.jpeds.com). Compared with children in the analyses, those who were lost to follow-up were less likely to have IVH/PVL and NEC, had higher gestational ages and birth weights, and were more likely to be in the uninfected infection group. There were no significant differences by sex, race, postnatal corticosteroid receipt, or CLD. From this same cohort of ELBW infants, there were 1,333 infants in the NRN ELBW registry who survived to 72 hours and were not screened or treated for sepsis or meningitis. Among whom, 58 were excluded due to major congenital anomaly, 34 had incomplete data at follow-up, and 377 were lost to follow-up or ineligible for follow-up based on their gestational age. The remaining 864 infants (67% from Epoch 1 and 33% from Epoch 2) were included in our analyses as the GDB uninfected comparison group.

Figure 1. Candida Study Enrollment.

* 2 infants in Candida study were born before 3/04 (birthdates 1/04 and 2/04)

Bivariate analyses were conducted to compare Candida-infected children to those in the other infection groups based on epoch, sex, birth weight, maternal education, race, postnatal steroids, IVH/PVL, NEC, and CLD. (Table II) Compared with uninfected children in either the Candida study or the NRN registry, children with Candida infection were significantly more likely to be male, have lower birth weight, have lower maternal education, have received postnatal corticosteroids, have IVH/PVL, have NEC, and have CLD (p < .05; Table II)

Table 2.

Demographic and Medical Characteristics by Infection Status

| Characteristic | Candida Study

|

GDB (Post hoc comparison group)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida (N=123) | LOS (N=533) | Clinical infection (N=381) | Uninfected (N=280) | Uninfected (N=864) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Cohort 1 | 66 (54) | 298 (56) | 187 (49) | 137 (49) | 284 (33) |

| Male | 70 (57) | 286 (54) | 191 (50) | 123 (44) | 362 (42) |

| Birth weight < 750g | 83 (67) | 257 (48) | 194 (51) | 82 (29) | 295 (34) |

| High school or less education | 70 (67) | 255 (52) | 176 (49) | 139 (51) | 388 (50) |

| Nonwhite race | 56 (46) | 245 (46) | 158 (41) | 111 (40) | 387 (45) |

| Postnatal steroids | 17 (14) | 63 (12) | 47 (12) | 15 (5) | 35 (4) |

| IVH/PVL | 39 (32) | 104 (20) | 55 (14) | 27 (10) | 198 (23) |

| NEC | 23 (19) | 106 (20) | 43 (11) | -- | -- |

| CLD | 55 (63) | 253 (58) | 163 (48) | 83 (31) | 193 (29) |

| Early onset sepsis | 3 (2) | 13 (2) | 9 (2) | -- | -- |

| Weight percentile at 18-month follow-up (kg)…mean (SD) | 39 (30) | 39 (30) | 36 (29) | 41 (28) | 41 (30) |

| Length percentile at 18-month follow-up (cm)…mean (SD) | 31 (30) | 27 (28) | 28 (28) | 32 (27) | 33 (29) |

| Head circumference percentile at 18-month follow-up (cm)…mean (SD)* | 44 (36) | 42 (31) | 40 (32) | 49 (30) | 50 (30) |

| Head circumference at 18 mo <3rd percentile* | 15 (21) | 44 (11) | 41 (13) | 12 (5) | 30 (5) |

Note: The uninfected groups exclude infants with NEC by definition. Percentages for CLD and maternal education only include children with data on those variables.

Head circumference data available on 1,715 children

Infection Incidence

Among infants in the Candida study, 123 infants (9%) developed Candida sepsis/meningitis, 533 infants (40%) had LOS associated with pathogens other than Candida, 381 (29%) had clinical infection, and 280 (21%) were uninfected. Among the infants with Candida sepsis/meningitis who survived and had repeated cultures from the same source, the median time to negative culture was 6 days (range 1–28 days); however, 25% of infants had positive cultures for ≥ 10 days.

A total of 55 (4.2%) of the infants in the Candida study had positive CSF cultures. The most common bacterial pathogens causing meningitis were: Staphylococcus sp. (coagulase-negative-Staphylococcus (N=28) and S aureus (N=4), Klebsiella sp (N=5) and Steptococcus sp (N=4). Positive CSF cultures due to Candida infection were due to C albicans (N=7) and C parapsilosis (N=1). Among those with a positive CSF culture for Candida only 50% also had a positive blood culture for Candida within 7 days.

Mortality by Infection Status

Two hundred and fifty-one infants (19%) enrolled in the Candida study died; of whom 51 (20%) had Candida sepsis/meningitis. Forty-one percent of Candida infected infants died (Table III). The death rate was similar between the two epochs; however, the risk was significantly higher among those infants who were male, of lower birth weight, with lower maternal education, and who developed severe IVH/PVL or NEC (Table IV).

Table 3.

Death and Neurodevelopmental Impairment by Infection Status

| Infection status | Death | NDI | Death/NDI |

|---|---|---|---|

| N/Total N (%) | N/Total N (%) | N/Total N (%) | |

| Candida Study | |||

| Candida | 51/123 (41) | 22/72 (31) | 73/123 (59) |

| LOS-Other | 131/533 (25) | 126/402 (31) | 257/533 (48) |

| Clinical Infection | 55/381 (14) | 89/326 (27) | 144/381 (38) |

| Uninfected | 14/280 (5) | 44/266 (17) | 58/280 (21) |

| NRN Registry | |||

| Uninfected | 213/864 (25) | 109/651 (17) | 322/864 (37) |

Note: Percentages for NDI include only children with NDI data at the follow-up visit.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Models of Death and NDI by Infection Status

| Variable | Death | NDI | Death/NDI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj OR (95% CI) | p | Adj OR (95% CI) | P | Adj OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Infection Status: Candida vs. Groups from Candida Study | ||||||

| Candida vs. Uninfected (Candida study) | 4.76 (2.24, 10.14) | < 0.001 | 1.37 (0.72, 2.63) | 0.339 | 2.47 (1.47, 4.13) | 0.001 |

| Candida vs. LOS-Other | 1.62 (0.96, 2.75) | 0.073 | 0.79 (0.44, 1.43) | 0.441 | 1.19 (0.76, 1.85) | 0.457 |

| Candida vs. Clinical infection | 2.59 (1.47, 4.55) | 0.001 | 0.83 (0.45, 1.53) | 0.559 | 1.57 (0.99, 2.49) | 0.057 |

| Infection Status: Candida vs. Group from NRN registry | ||||||

| Candida vs. Uninfected (NRN registry) | 0.85 (0.51, 1.43) | 0.545 | 1.83 (1.01, 3.33) | 0.047 | 1.54 (0.99, 2.38) | 0.054 |

| Epoch 1 | 1.14 (0.88, 1.46) | 0.325 | 6.22 (4.59, 8.43) | < 0.001 | 3.35 (2.69, 4.17) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 2.08 (1.62, 2.67) | < 0.001 | 1.54 (1.19, 1.99) | 0.001 | 1.93 (1.57, 2.37) | < 0.001 |

| Birth weight < 750g | 5.41 (4.17, 7.02) | < 0.001 | 1.66 (1.27, 2.18) | < 0.001 | 3.20 (2.59, 3.95) | < 0.001 |

| Nonwhite race | 1.07 (0.84, 1.37) | 0.587 | 1.56 (1.21, 2.01) | 0.001 | 1.40 (1.14, 1.72) | 0.001 |

| High school or less | 1.84 (1.35, 2.52) | < 0.001 | 1.44 (1.12, 1.86) | 0.005 | 1.70 (1.35, 2.13) | < 0.001 |

| Postnatal corticosteroids | 1.19 (0.75, 1.89) | 0.452 | 2.24 (1.45, 3.45) | < 0.001 | 2.00 (1.36, 2.93) | < 0.001 |

| IVH/PVL | 4.84 (3.70, 6.31) | < 0.001 | 3.08 (2.19, 4.33) | < 0.001 | 5.45 (4.17, 7.10) | < 0.001 |

| NEC | 5.20 (3.38, 8.02) | < 0.001 | 1.26 (0.75, 2.12) | 0.377 | 2.82 (1.90, 4.18) | < 0.001 |

Note: Models also account for clustering of children within research centers. Model for NDI excludes children without data on NDI at follow-up. Reference categories are epoch 2, female, birth weight ≥ 750g, white race, more than high school education, did not receive postnatal steroids, did not have IVH/PVL, and did not have NEC. Areas under the ROC curve (AUC) for the models are: Death (AUC=0.83), NDI (AUC=0.77), and Death/NDI (AUC=0.80).

Overall, when comparing infants enrolled in the Candida study, those with Candida sepsis/meningitis were more likely to die compared with both those infected with other pathogens and those who were uninfected (Table III). In adjusted analyses, these differences were statistically similar to those with other LOS infections; however, they were statistically different compared with uninfected infants in the Candida study (OR (95% CI) = 4.76 (2.24, 10.14), p<.001) (Table IV). Odds of death were similar compared with uninfected infants enrolled in the NRN registry; however, cause of death was most commonly attributed to proven or suspected sepsis (37%), NEC (16%), CLD (14%), and RDS (10%) among infants with Candida in contrast to those in the NRN Registry-Uninfected group where 50% of deaths were related to RDS or severe IVH.

Among infants with Candida dying before hospital discharge, the median number of days between first positive Candida culture and death was 13 days (range 0–283 days). Ninety-nine infants (80%) with Candida sepsis/meningitis had a catheter in place at the time of the initial infection. Death rates did not differ significantly between those with a catheter for ≤ one week and those with the catheter > one week (39% v 43%) after testing positive for Candida.

Neurodevelopmental Outcome

ND outcomes are reported by infection status and epoch (Tables I, III, and IV). In unadjusted comparison, Candida infected infants had similar rates of NDI to those infected with other LOS pathogens but higher rates compared with uninfected infants in both the Candida study and the NRN Registry Uninfected group (Table III). After controlling for other factors, these differences in NDI alone were no longer seen based on infection status for infants enrolled in the Candida study (Table IV). However, Candida infected had significantly higher odds of NDI compared with uninfected NRN registry infants with no history of suspected sepsis or proven sepsis (OR (95% CI) =1.83 (1.01,3.33, p=0.047) (Table IV). In unadjusted analyses, those with Candida infection were more likely to have a head circumference <3rd percentile for adjusted age at follow-up compared with those in the GDB Uninfected Group (Candida 21%; OR 5.42 (2.76, 10.66). Children with LOS (11% OR 2.55 (1.58, 4.14)) and Clinical Infection (13%; OR 2.97 (1.82,4.86)) were also more likely to have microcephaly than the GDB Uninfected Group. There was no difference between those in the two uninfected groups (Uninfected 5%; OR 0.97 (OR 0.49, 1.93).

Among infants in the Candida study, neurodevelopmental outcomes for the 544/688 (79%) infants enrolled in Epoch 1 and the 522/629 (83%) infants enrolled in Epoch 2 assessed at 18-month follow-up are outlined in Table I. The two groups were similar with respect to infection group, race, sex, gestational age, birth weight, IVH/PVL, CLD, and NEC. However, significantly more children in Epochs 1 received postnatal corticosteroids (13% vs. 9%; p=.023), and fewer had meningitis (3% vs. 5%; p=.033). Although children from the two study periods had similar mortality rates (Table IV), significant differences were noted in NDI at 18 months with 41% of children in Epoch 1 diagnosed with NDI compared with 11% in Epoch 2 (Table I). The rate of NDI increases from 11% to 30% in Epoch 2 if a cutoff of <85 is used to define NDI; however, the differences in rates of NDI remain significantly different between the two groups. Infants in Epoch 1 were significantly more likely to have moderate/severe CP than those in Epoch 2 (8% vs. 4%) (Table I).

Duration of positive cultures did not predict the risk for NDI. Candida infected infants with a catheter greater than or equal to one week after testing positive for Candida had significantly higher rates of NDI alone (50% vs. 19%) (OR (95% CI) = 4.37 (1.50, 12.77), p=.007) and the combined outcome of death/NDI (71% vs. 51%) (OR (95% CI) = 2.43 (1.12, 5.28), p= .025) compared with those with catheters less than or equal to one week after infection.

Composite Outcome of Death/NDI

Candida infected infants were significantly more likely to have death and/or NDI compared with all other infection groups. These differences were most striking among those infants < 750 grams and those who were uninfected.

Discussion

Infectious complications of prematurity, including late onset sepsis, have been associated with an increased mortality risk, adverse neurodevelopmental outcome and growth impairment.(4, 5, 15) In our study evaluating outcomes of a high risk group of infants who had clinical signs suggestive of sepsis, systemic candidiasis was associated with an increased risk of death and/or NDI compared with uninfected infants but similar outcome to those infected with other late onset pathogens.

Research suggests that the cytokine mediated inflammatory response generated in response to infection may be responsible for injury to the developing central nervous system secondary to activation of innate and adaptive immune responses resulting in direct and downstream neurotoxic effects on developing neurons.(16, 17) Furthermore, the maturation dependent vulnerability of the developing white matter to cytokine induced injury creates a critical window of vulnerability for the ELBW infant which likely contributes to the adverse neurodevelopmental outcome of infected infants.(17–19) Clinical and animal studies evaluating cytokine response to specific pathogens are limited. (20, 21) The complexity of downstream activation and interaction makes it difficult to identify a direct causal relationship between a specific cytokine or pathogen and the resultant brain injury.(19, 22, 23) The number of children with a previous early onset pathogen was small therefore we were unable to evaluate any relationship between EOS and later risk of Candida infection or the impact on multiple infections on ND outcome.

In the current study, we evaluated differences in ND outcome between Candida infected infants to both those who were uninfected and those infected with other late onset pathogens to better understand the specific impact of Candida infection on ND outcome. Stoll et al evaluated ND outcome at 18 months in 6093 ELBW infants.(4) Compared with uninfected infants, those with infection had worse ND outcome; however, this risk did not vary based on pathogen except for an increased risk of hearing impairment among those with Candida infection. Similarly, in our study, survivors with systemic candidiasis had a similar risk of poor neurologic outcome as those infected with other pathogens, which suggests that the pathophysiologic pathways resulting in CNS injury in infected preterm neonates may not be pathogen specific. Additional research evaluating specific cytokine responses at the onset of infection are needed to better understand this relationship.

Our study is unique because only infants being evaluated for sepsis were eligible for inclusion in the Candida study. We speculated that the uninfected group in the Candida study was not representative of a more homogenous ELBW population because the overall rate of culture proven LOS in the Candida study cohort was significantly higher than previous reports of similar low birth weight populations. (3, 4) Therefore a significant percentage of infants would not be accounted for in the uninfected group based on our study design. How these findings affected our outcome are unclear; however, both represent potential bias and limit comparability with previous reports. Our results are consistent with this observation in that differences in ND outcome were seen between Candida infected infants compared with uninfected GDB infants but not with uninfected infants in the Candida study.

Approximately 7% of infants with Candida isolated from the blood culture also had a positive CSF culture; however, lumbar punctures were not systematically performed on infants with culture proven or suspected sepsis. The small number of infants with meningitis limits our ability to interpret these data. Furthermore, animal model and autopsy studies suggest that parenchymal involvement resulting in meningo-encephalitis is more common with Candida infection which may further underestimate the impact on CNS injury.(24)

The neurodevelopmental assessment tool changed during the study period due to the 2005 revision in the BSID. Even though there were similar demographic profiles and rates of Candida infection between both epochs, our study may not have been adequately powered to detect differences in NDI due to the unanticipated lower rate of NDI among infants evaluated using the BSID-III. We can only speculate about reasons for the significantly higher cognitive scores among children evaluated using the BSID-III. There are limited data regarding comparability of the two versions of the BSID, appropriate cutoffs to define impairment or the long term predictive validity of the BSID-III in a preterm population.(25) In our cohort, differences in NDI may be related to differences in rates of moderate/severe CP between the two epochs. Additional research is needed to explore the differences in these two instruments.

Interestingly, in this cohort neurodevelopmental outcome did not correlate with duration of positive cultures; however, these data were quite skewed and the number of patients with prolonged candidemia was small. However, similar to previous reports (26), we observed an association between delayed catheter removal and increased risk of death and/or NDI. Among Candida infected infants < 750 grams, 50% die, 33% survivors have NDI and 66% either die or have NDI. The dramatically increased mortality among infants infected with Candida emphasizes the need for development and implementation of multi-level strategies and guidelines to enhance prevention, early detection and treatment of these high risk infants. (7, 26–30)

Among infants enrolled in the Candida study, those with systemic candidiasis had the highest risk of death. Infected survivors had similar neurodevelopmental outcomes compared with other infants in this cohort but worse outcomes compared with peers with no history of suspected infection, particularly among those < 750 gram birthweight.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) for the Neonatal Research Network’s Candidiasis Study. D.B. received support from the Thrasher Research Fund and NICHD (HD44799). The funding agencies provided overall oversight for study conduct, but all data analyses and interpretation were independent of the funding agencies. Data collected at participating sites of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network were transmitted to RTI International, the data coordinating center for the network, which stored, managed, and analyzed the data for this study.

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. The NICHD NRN is deeply grateful for the scholarly contributions and leadership of Anna M. Dusick, MD (Indiana University Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Riley Hospital for Children, and Wishard Health Services [U10 HD27856, M01 RR750]), who died prior to the publication of this article.

Abbreviations

- BSID

Bayley Scales of Infant Development

- CLD

Chronic Lung Disease

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- CP

Cerebral Palsy

- CSF

Cerebrospinal Fluid

- ELBW

Extremely Low Birth Weight

- EOS

Early Onset Sepsis

- GA

Gestational Age

- GDB

Generic Database

- IVH

Intraventricular Hemorrhage

- LOS

Late Onset Sepsis

- ND

Neurodevelopmental

- NDI

Neurodevelopmental Impairment

- NEC

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

- NICHD

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- NRN

Neonatal Research Network

- PVL

Periventricular Leukomalacia

- RDS

Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- VLBW

Very Low Birth Weight

Appendix

The following investigators, in addition to those listed as authors, are members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network:

NRN Steering Committee Chairs: Alan Jobe, MD PhD, University of Cincinnati (2001–2006); Michael S. Caplan, MD, University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine (2006–2011).

Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (U10 HD27904) – William Oh, MD; Abbot R. Laptook, MD; Angelita M. Hensman, RN BSN; Theresa M. Leach, MEd CAES; Lucy Noel; Bonnie E. Stephens, MD; Dawn Andrews, RN MS; Kristen Angela, RN.

Case Western Reserve University Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital (U10 HD21364, M01 RR80) – Avroy A. Fanaroff, MD; Nancy S. Newman, BA RN; Harriet G. Friedman, MA; Bonnie S. Siner, RN.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center University Hospital and Good Samaritan Hospital (U10 HD27853, M01 RR8084) – Kurt Schibler, MD; Edward F. Donovan, MD; Kimberly Yolton, PhD; Barbara Alexander, RN; Kate Bridges, MD; Teresa L. Gratton, PA; Cathy Grisby, BSN CCRC; Jody Hessling, RN; Holly L. Mincey, RN BSN.

Duke University School of Medicine University Hospital, Alamance Regional Medical Center, and Durham Regional Hospital (U10 HD40492, M01 RR30) – C. Michael Cotten, MD MHS; Kathy J. Auten, MSHS; Kimberley A. Fisher, PhD FNP-BC IBCLC; Katherine A. Foy, RN; Sandra Grimes, RN BSN; Kathryn E. Gustafson, PhD; Melody B. Lohmeyer, RN MSN.

Emory University Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Grady Memorial Hospital, and Emory University Hospital Midtown (U10 HD27851, UL1 RR25008, M01 RR39) – Yun F. Wang, MD; Ellen C. Hale, RN BS CCRC; Ann Blackwelder, RNC, MS; David P. Carlton, MD; Maureen Mulligan LaRossa, RN; Sheena Carter PhD; Gloria Smikle, PNP MSN.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development – Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.

Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center (U10 HD53119, M01 RR54) – Ivan D. Frantz III, MD; Brenda L. MacKinnon, RNC; Ellen Nylen, RN BSN; Anne Furey, MPH; Cecelia Sibley, PT MHA; Ana Brussa, MS OTR/L.

Indiana University Indiana University Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Riley Hospital for Children, and Wishard Health Services (U10 HD27856, M01 RR750) – Brenda B. Poindexter, MD MS; James A. Lemons, MD; Ann B. Cook, MS; Faithe Hamer, BS; Dianne E. Herron, RN; Carolyn Lytle, MD MPH; Lucy C. Miller, RN BSN CCRC; Heike M. Minnich, PsyD HSPP; Cassandra L. Stahlke, BS; Leslie Dawn Wilson, BSN CCRC.

RTI International (U10 HD36790) – W. Kenneth Poole, PhD; Dennis Wallace, PhD; Jeanette O’Donnell Auman, BS; Margaret Cunningham, BS; Marie Gantz, PhD; Amanda R. Irene, BS; Betty K. Hastings; Elizabeth M. McClure, MEd; Jamie E. Newman, PhD MPH; Carolyn M. Petrie Huitema, MS; James W. Pickett II, BS; Scott E. Schaefer, MS; Kristin M. Zaterka-Baxter, RN BSN.

Stanford University Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (U10 HD27880, M01 RR70) – Krisa P. Van Meurs, MD; David K. Stevenson, MD; M. Bethany Ball, BS CCRC; Anne M. DeBattista, RN PNP; Alexis S. Davis, MD MS Epi; Jean G. Kohn, MD MPH; Barbara Bentley, PhD; Ginger K. Brudos, PhD; Renee P. Pyle, PhD.

University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System and Children’s Hospital of Alabama (U10 HD34216, M01 RR32) – Waldemar A. Carlo, MD; Namasivayam Ambalavanan, MD; Monica V. Collins, RN BSN MaEd; Shirley S. Cosby, RN BSN; Fred J. Biasini, PhD; Kristen C. Johnston, MSN CRNP; Kathleen G. Nelson, MD; Cryshelle S. Patterson, PhD; Vivien A. Phillips, RN BSN; Richard V. Rector, PhD; Sally Whitley, MA OTR-L FAOTA.

University of California – San Diego Medical Center and Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women and Newborns (U10 HD40461) – Neil N. Finer, MD; Maynard R. Rasmussen MD; David Kaegi, MD; Kathy Arnell, RNC; Renee Bridge, RN; Clarence Demetrio, RN; Martha G. Fuller, RN MSN; Chris Henderson, RCP CRTT; Wade Rich, BSHS RRT.

University of Iowa Children’s Hospital (U10 HD53109, M01 RR59) – Edward F. Bell, MD; John A. Widness, MD; Karen J. Johnson, RN BSN; Diane L. Eastman, RN CPNP MA.

University of Miami Holtz Children’s Hospital (U10 HD21397) – Shahnaz Duara, MD; Ruth Everett- Thomas, RN MSN; Amy Mur Worth, RN MS; Maria Calejo, MS; Alexis N. Diaz, BA; Silvia M. Frade Eguaras; BA; Yamiley C. Gideon; BA; Sylvia Hiriart-Fajardo, MD; Ann Londono, MD; Elaine O. Mathews, RN; Alexandra Stroerger, BA.

University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (U10 HD53089, M01 RR997) – Robin K. Ohls, MD; Conra Backstrom Lacy, RN.

University of Rochester Medical Center and Golisano Children’s Hospital (U10 HD40521, M01 RR44, UL1 RR24160) – Dale L. Phelps, MD; Linda J. Reubens, RN CCRC; Erica Burnell, RN; Diane Hust, MS RN CS; Rosemary L. Jensen; Julie Babish Johnson, MSW; Emily Kushner, MA; Kelley Yost, PhD; Lauren Zwetsch, RN MS PNP; Joan Merzbach, LMSW.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Parkland Health & Hospital System and Children’s Medical Center Dallas (U10 HD40689, M01 RR633) – Pablo J. Sánchez, MD; Charles R. Rosenfeld, MD; Walid A. Salhab, MD; Nancy A. Miller, RN; Alicia Guzman; Gaynelle Hensley, RN; Melissa H. Leps, RN; Roy J. Heyne, MD; Janet S. Morgan, RN; Lizette E. Torres, RN; Catherine Twell Boatman, MS CIMI; Sally S. Adams, MS RN CPNP; Elizabeth Heyne, PsyD PA-C; Linda A. Madden, RN CPNP.

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Medical School and Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital (U10 HD21373) – Kathleen A. Kennedy, MD MPH; Jon E. Tyson, MD MPH; Margarita Jiminez, MD MPH; Brenda H. Morris, MD; Saba Siddiki, MD; Esther G. Akpa, RN BSN; Nora I. Alaniz, BS; Susan Dieterich, PhD; Beverly Foley Harris, RN BSN; Charles Green, PhD; Anna E. Lis, RN BSN; Sarah Martin, RN BSN; Georgia E. McDavid, RN; Patti L. Pierce Tate, RCP; Margaret L. Poundstone, RN BSN; Stacey Reddoch, BA; Maegan C. Simmons, RN; Sharon L. Wright, MT (ASCP).

Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Brenner Children’s Hospital, and Forsyth Medical Center (U10 HD40498, M01 RR7122) – T. Michael O’Shea, MD MPH; Nancy J. Peters, RN CCRP; Korinne Chiu, MA; Deborah Evans Allred, MA LPA; Donald J. Goldstein, PhD; Carroll Peterson, MA; Ellen L. Waldrep, MS; Lisa K. Washburn, MD; Barbara G. Jackson, RN, BSN.

Wayne State University Hutzel Women’s Hospital and Children’s Hospital of Michigan (U10 HD21385) – Rebecca Bara, RN BSN; Laura Goldston, MA.

Yale University Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital (U10 HD27871, UL1 RR24139, M01 RR125) – Patricia Gettner, RN; Monica Konstantino, RN BSN; JoAnn Poulsen, RN; Elaine Romano, MSN; Janet Taft, RN BSN.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of the study were presented as a poster at the Pediatric Academic Society Meeting in May 2010.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Benjamin DK, Jr, Stoll BJ, Gantz MG, Walsh MC, Sanchez PJ, Das A, et al. Neonatal candidiasis: epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical judgment. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):e865–73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3412. Epub 2010/09/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin DK, Jr, Ross K, McKinney RE, Jr, Benjamin DK, Auten R, Fisher RG. When to Suspect Fungal Infection in Neonates: A Clinical Comparison of Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis Fungemia With Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcal Bacteremia. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4):712–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 Pt 1):285–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.285. Epub 2002/08/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr B, et al. Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA. 2004;292(19):2357–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2357. Epub 2004/11/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vohr BR, Wright LL, Dusick AM, Mele L, Verter J, Steichen JJ, et al. Neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 1993–1994. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):1216–26. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.1216. Epub 2000/06/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman S, Richardson SE, Jacobs SE, O’Brien K. Systemic Candida infection in extremely low birth weight infants: short term morbidity and long term neurodevelopmental outcome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(6):499–504. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200006000-00002. Epub 2000/07/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin D, Stoll BJ, Fanaroff AA, McDonald SA, Oh W, et al. Neonatal Candidiasis Among Extremely Low Birth Weigh Infants: Risk Factors, Mortality Rates, and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 18 to 22 Months. Pediatrics. 2006;117:84–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamin DK, Jr, Stoll BJ, Gantz MJ, Walsh MC, Sanchez PJ, Das A, et al. Neonatal Candidasis: Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Clinical Judgement. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):e865–73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Walsh MC, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):443–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2959. Epub 2010/08/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP, Marshall R, Barton L, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Annals of surgery. 1978;187(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197801000-00001. Epub 1978/01/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92(4):529–34. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80282-0. Epub 1978/04/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 1997;39(4):214–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x. Epub 1997/04/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayley N. The Bayley Scales of Infant Development -II. San Antonio, Texas: The Psych Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bayley N. Manual for the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. San Antonio, Texas: Harcourt Assessment; 2006. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulzke SM, Deshpande GC, Patole SK. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Very Low-Birth-Weight Infants With Necrotizing Enterocolitis: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(6):583–90. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khwaja O, Volpe JJ. Pathogenesis of cerebral white matter injury of prematurity. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93(2):F153–61. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.108837. Epub 2008/02/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leviton A, Gressens P. Neuronal damage accompanies perinatal white-matter damage. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(9):473–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.009. Epub 2007/09/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Back SA, Luo NL, Borenstein NS, Levine JM, Volpe JJ, Kinney HC. Late oligodendrocyte progenitors coincide with the developmental window of vulnerability for human perinatal white matter injury. J Neurosci. 2001;21(4):1302–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01302.2001. Epub 2001/02/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rezaie P, Dean A. Periventricular leukomalacia, inflammation and white matter lesions within the developing nervous system. Neuropathology. 2002;22(3):106–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2002.00438.x. Epub 2002/11/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schelonka RL, Maheshwari A, Carlo WA, Taylor S, Hansen NI, Schendel DE, et al. T cell cytokines and the risk of blood stream infection in extremely low birth weight infants. Cytokine. 53(2):249–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baier RJ, Loggins J, Yanamandra K. IL-10, IL-6 and CD14 polymorphisms and sepsis outcome in ventilated very low birth weight infants. BMC medicine. 2006;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-10. Epub 2006/04/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams-Chapman I, Stoll BJ. Neonatal infection and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in the preterm infant. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19(3):290–7. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000224825.57976.87. Epub 2006/04/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girard S, Kadhim H, Roy M, Lavoie K, Brochu ME, Larouche A, et al. Role of perinatal inflammation in cerebral palsy. Pediatric neurology. 2009;40(3):168–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.09.016. Epub 2009/02/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faix RG. Systemic Candida infections in infants in intensive care nurseries: High incidence of central nervous system involvement. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1984;105(4):616–22. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80433-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson PJ, De Luca CR, Hutchinson E, Roberts G, Doyle LW. Underestimation of developmental delay by the new Bayley-III Scale. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 164(4):352–6. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.20. Epub 2010/04/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benjamin DK, Jr, Miller W, Garges H, Benjamin DK, McKinney RE, Jr, Cotton M, et al. Bacteremia, Central Catheters, and Neonates: When to Pull the Line. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1272–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clerihew LAN, McGuire W. Prophylactic systemic antifungal agents to prevent mortality and morbidity in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Dababase of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003850.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlowicz MG, Hashimoto LN, Kelly RE, Jr, Buescher ES. Should central venous catheters be removed as soon as candidemia is detected in neonates? Pediatrics. 2000;106(5):E63. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.5.e63. Epub 2000/11/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaufman D, Boyle R, Hazen KC, Patrie JT, Robinson M, Donowitz LG. Fluconazole prophylaxis against fungal colonization and infection in preterm infants. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;345(23):1660–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010494. Epub 2002/01/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manzoni P, Stolfi I, Pugni L, Decembrino L, Magnani C, Vetrano G, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of prophylactic fluconazole in preterm neonates. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356(24):2483–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065733. Epub 2007/06/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]