Abstract

The effect of metal ions on the enzymatic activity of Lactobacillus reuteri was studied. The enzymatic activity was determined spectrophotometrically using the corresponding substrate. In the control group, L. reuteri MF14-C, MM2-3, SD2112, and DSM20016 produced the highest α-glucosidase (40.06 ± 2.80 Glu U/mL), β-glucosidase (17.82 ± 1.45 Glu U/mL), acid phosphatase (20.55 ± 0.74 Ph U/mL), and phytase (0.90 ± 0.05 Ph U/mL) respectively. The addition of Mg2+ and Mn2+ led to enhance α-glucosidase produced by L. reuteri MM2-3 by 113.6% and 100.6% respectively. α-Glucosidase produced by MF14-C and CF2-7F was decrease in the presence of K+ by 65.8 and 69.4% respectively. β-Glucosidase activity of MM7 and SD2112 increased in the presence of Ca2+ (by 121.8 and 129.8%) and Fe2+ (by 143.9 and 126.7%) respectively. Acid phosphatase produced by L. reuteri CF2-7F and MM2-3 was enhanced in the presence of Mg2+, Ca2+ or Mn2+ by (94.7, 43.2, and 70.1%) and (63.1, 67.8, and 45.6%) respectively. On the other hand, Fe2+, K+, and Na+ caused only slight increase or decrease in acid phosphatase activity. Phytase produced by L. reuteri MM2-3 was increase in the presence of Mg2+ and Mn2+ by 51.0 and 74.5% respectively. Ca2+ enhanced phytase activity of MM2-3 and DSM20016 by 27.5 and 28.9% respectively. The addition of Na+ or Fe2+ decreased phytase activity of L. reuteri. On average, Mg2+ and Mn2+ followed by Ca2+ led to the highest enhancement of the tested enzymes. However, the effect of each metal ion on the enzymatic activity of L. reuteri was found to be a strain dependent. Therefore, a maximized level of a target enzyme could be achieved by selecting a combination of specific strain and specific metal ion.

Keywords: L. reuteri, Metal ions, Mg2+, Mn2+, α–glucosidase, β-glucosidases, Acid phosphatase, Phytase

Introduction

Species of the genus lactobacilli are commonly found in a diversity of ecosystems including human, animal, plants, and soil (Barrangou et al. 2011; Song et al. 2012). Lactobacillus has been employed in many applications with regard to food, feed, and fertilizers. This genus of lactic acid bacteria is the lead of food fermentation and probiotic applications (Rodríguez et al. 2009; Song et al. 2012). Lactobacillus produces several functional enzymes that could help in the digestibility of complex carbohydrates such as indigestible fibers and benefit the human health (Mahajan et al. 2010; Palacios et al. 2007; Raghavendra and Halami 2009; Zotta et al. 2007). For example, α–glucosidase (α-D-glucoside glucohydrolase, EC 3.2.1.20) is responsible for hydrolyzing glycosidic bonds in oligosaccharides (starch, disaccharides, and glycogen) and releasing α-glucose (Krasikov et al. 2001). Deficiency of α–glucosidase in human could cause glycogen storage disease II which also known as Pompe (Krasikov et al. 2001). β-Glucosidase (β-D-glucoside glucohydrolase, EC 3.2.1.21) hydrolyzes all four β-linked glucose dimmers in cellulose to produce glucose monomers (Sestelo et al. 2004). Cellulose is considered the highest proportion of plants, and can be hydrolyzed by β-glucosidases for both industry and human health. Humans are unable to digest cellulose due to the low levels of cellulases in the gut. β-Glucosidase is also used in the production of fuel ethanol from cellulose and in food fermentation to release the aromatic compounds (Sestelo et al. 2004). Acid phosphatase (orthophosphoric monoester phosphohydrolase, EC. 3.1.3.2) and phytase (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate 6-phosphohydrolases; EC 3.1.3.26) hydrolyze phytate and reduce its antinutritional properties (Iqbal et al. 1994; López-González et al. 2008; Palacios et al. 2005). The specificity of acid phosphatase and phytase can partially overlapped since acid phosphatase produced by microorganisms has phytase activity (Simon and Igbasan 2002). Phytate is a common fiber that found in cereals, legumes, and nuts, and acts as an antinutrient binding with proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and metal ions (zinc, iron, calcium, and magnesium). Phytate degrading activity in humans is relatively low (mainly in the small intestine) (Iqbal et al. 1994), so other sources of phytate degrading enzymes are required. Microbial sources of such functional enzymes could be the most promising sources for human health.

Utilization of indigestible fibers and oligosaccharides, not digestible by human enzymes, has been recognized as an important attribute of probiotics (Alazzeh et al. 2009; Gyawali and Ibrahim 2012; Song et al. 2012). Species of Lactobacillus that produce functional enzymes such as α-glucosidase, β-glucosidase, acid phosphatase, and phytase could have an important impact on human health. However, the production capacity of such hydrolyzing enzymes by Lactobacillus is strain specific (Bury et al. 2001; Ibrahim et al. 2010; Palacios et al. 2007; Zotta et al. 2009; Zotta et al. 2007). Lactobacillus reuteri is known to inhabit the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals (Casas and Dobrogosz 2000). L. reuteri is a special probiotic species since the entire species has been shown to exhibit efficient probiotic functionality (Casas and Dobrogosz 2000) and to produce different functional enzymes (Alazzeh et al. 2009). L. reuteri exhibit high activity of α-galactosidase and β-galactosidase (Ibrahim et al. 2010). Strains of L. reuteri have high activity of α-glucosidase (Kralj et al. 2005) and β-glucosidase (Otieno et al. 2005). These strains also showed the highest phytate degrading activity producing both phytase and acid phosphatase compare to other Lactobacillus spp. (Palacios et al. 2007). We have previously shown that L. reuteri produce higher α spp. (Hayek -glucosidase, acid phosphatase, and phytase than other Lactobacillus2013).

In addition to human health applications, these probiotic strains can be also used in animals and plants. However, the enzymatic activity of Lactobacillus can be affected by their nutritional requirements such as vitamins metal ions, sugars, and protein (Alazzeh et al. 2009; Hayek and Ibrahim 2013; Ibrahim et al. 2010; Mahajan et al. 2010; Palacios et al. 2005). Nevertheless, even though the nutritional requirements of Lactobacillus have been established, controlling, optimizing, and maximizing the enzymatic activity of Lactobacillus have many limitations and challenges (Hayek and Ibrahim 2013). Metal ions have been reported in several studies to enhance the enzymatic activity of Lactobacillus (Aqel spp. including L. reuteri2012; Ibrahim et al. 2010; Ozimek et al. 2005; Palacios et al. 2005). For example, the addition of 10 mM of Mn2+ caused a significant enhancement in β-glucosidase activity while 10 mM of Zn2+ or Cu2+ resulted in a reduction of β-glucosidase of up to 90%. (Jeng et al. 2011). Acid phosphatase was enhanced by Ca2+ and Mg2+ with a greater effect on Ca2+ (Tham et al. 2010). Thus, developing a means to enhance the enzymatic activity of L. reuteri may help to solve different digestive problems.

Sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) (Batatas an Arawak name) are an abundant agricultural product that play a major role in the food industry and human nutrition. Sweet potatoes are a rich source of carbohydrates (mainly starch and sugars), some amino acids, vitamins (vitamin A, vitamin C, thiamin (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin, and vitamin E), minerals (calcium, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, and zinc), and dietary fiber (Broihier 2006; Padmaja 2009). Sweet potatoes also contain other minor nutrients such as antioxidants, triglycerides, linoleic acid, and palmitic acid (Broihier 2006; Padmaja 2009). Previous studies have shown that plant components can support the growth and functionality of probiotic bacteria (Gyawali and Ibrahim 2012). We have previously showed that sweet potatoes could be used to form an alternative low cost medium for the growth of Lactobacillus strains (Hayek et al. 2013). Lactobacillus strains grown in a sweet potato base medium were also found to produce higher β-glucosidase, acid phosphatase, and phytase activities and lower α–glucosidase than that in MRS (Hayek 2013). However, the suitability of the sweet potato base medium to study the effect of metal ions on the enzymatic activity of L. reuteri was not investigated. Therefore, the objective of this work was to study the effect of metal ions on α-glucosidase, β-glucosidase, acid phosphatase, and phytase activity of L. reuteri growing in a sweet potato based medium.

Materials and methods

Media preparation

Sweet potato medium (SPM) was previously developed to support the growth of Lactobacillus (Hayek et al. 2013). Fresh sweet potatoes (Covington cultivar) (obtained from Burch Farms in Faison NC, USA) were baked in a conventional oven at 400°C for 1 h. The sweet potatoes were then peeled and blended in a kitchen blender with deionized distilled water (DDW) at a ratio of 1:2. The solution was centrifuged at 7800 × g for 10 min using Sorvall RC 6 Plus Centrifuge (Thermo Scientific Co., Asheville, NC, USA) and the supernatant was collected. SPM was then formed by mixing 1 L of supernatant with the following ingredients: sodium acetate (5 g), potassium monophosphate (2 g), disodium phosphate (2 g), ammo-nium citrate (2 g), Tween 80 (1 mL), beef extract (Neogen Corporation, Lansing, MI, USA) (4 g), yeast extract (Neogen Corporation) (4 g), proteose peptone #3 (4 g), and L-Cysteine (1 g). SPM was sterilized at 121°C for 15 min, cooled down, and stored at 4°C then used within 3 days. All ingredients were obtained from Thermo Scientific Co. (Asheville, NC, USA) unless otherwise noted.

Bacterial culture activation and preparation

L. reuteri strains (Table 1) were provided by BioGaia (Raleigh, NC) and stored in the stock collection of the Food Microbiology and Biotechnology Laboratory, North Carolina A&T State University. The strains were activated in SPM by transferring 100 μL of stock culture to 10 mL SPM broth, incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and stored at 4°C. Prior to each experimental replication, bacterial strains were streaked on SPM agar and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. One isolated colony was then transferred to 10 mL SPM broth and incubated at 37°C for next day use.

Table 1.

Lactobacillus reuteristrains and sources

| L. reuteri | Source |

|---|---|

| MF14-C | Mother fecal isolate |

| CF2-7F | Child fecal isolate |

| DSM20016 | Mother’s milk |

| SD2112 | Mother’s milk |

| MM7 | Mother’s milk |

| MM2-3 | Mother’s milk |

Culturing with metal ions

Samples of SPM with metal ions were prepared by dissolving 10 mM of either FeSO4.4H2O, MgSO4.7H2O, K2SO4, or Na2SO4, or 5 mM of either MnSO4.4H2O or CaSO4.7H2O into batches of 60 mL non-sterile pre-prepared SPM. The use of 10 mM or less of metal ions was established to avoid the hypertonic pressure on bacterial cells (Ibrahim et al. 2010). The used 5 mM of MnSO4.4H2O and CaSO4.7H2O was required since higher concentrations did not dissolve completely in SPM. Batches of 60 mL SPM without metal ions served as control. Samples were sterilized at 121°C for 15 min, cooled down to room temperature, then inoculated with 3% v/v precultured L. reuteri and incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the turbidity (optical density (OD) at 610 nm) at 2 h intervals using a 96-well microplate reader (BioTek Institute, Winooski, VT). At the end of incubation, cultures were divided into two portions of 30 mL each. One portion was used for α-glucosidase and β-glucosidase determination and the other portion was used for acid phosphatase and phytase determination.

Enzyme samples preparation

Samples used for α-glucosidase and β-glucosidase determination were centrifuged at 7800 × g for 10 min at 4°C using Sorvall RC 6 Plus Centrifuge to harvest the bacterial cells. The cells were washed twice with 0.5 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and suspended in 1 mL of the same buffer. Suspended cells were maintained in Eppendorf tubes containing 0.1 mm glass beads and treated with a mini-Beadbeater-8 (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA) for a total of 3 min to disrupt the cells. During cells disruption, samples were allowed to rest after each minute for 15 s in an ice bath to avoid overheating. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min using Microcentrifuge 5415 R (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and supernatant was used for enzyme assay analysis of α-glucosidase. Disrupted cells were suspended in a minimum amount of sodium phosphate buffer and used for enzyme assay analysis of β-glucosidase.

Samples used for acid phosphates and phytase determination were centrifuged at 7800 × g for 10 min at 4°C to harvest the bacterial cells. The cells were washed with 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 6.5) and suspended in 1 mL 50 mM sodium acetate-acetic acid (pH 5.5). Suspended cells were disrupted then centrifuged using same procedure as that of samples used for α-glucosidase and β-glucosidase. Supernatants were used for enzyme assay analysis of acid phosphatase and phytase.

Determination of α-glucosidase and β-glucosidase

α-Glucosidase and β-glucosidase were determined by monitoring the rate of hydrolysis of ρ-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (α-PNPG) and ρ-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (β-PNPG) respectively according to Mahajan and others with some modifications (Mahajan et al. 2010). In this procedure 1 mL of 10 mM of either (α-PNPG) or (β-PNPG) was mixed with 0.5 mL of the corresponding enzyme sample. Samples were then incubated at 37°C for 20 min. All reactions were stopped by adding 2.5 mL of 0.5 M Na2CO3. The released yellow ρ-nitrophenol was determined by measuring the OD at 420 nm. One unit of α-glucosidase or β-glucosidase (Glu U/mL) was defined as 1.0 μM of ρ-nitrophenol liberated per minute under assay conditions.

Determination of acid phosphatase and phytase

Acid phosphatase (E.C.3.1.3.2.) was determined by monitoring the rate of hydrolysis of ρ-nitrophenyl phosphate (PNPP), and phytase activity was determined by measuring the amount of liberated inorganic phosphate from sodium phytate (Haros et al. 2008). For acid phosphatase, 250 μL of 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) containing 5 mM PNPP was mixed with 250 μL of enzyme sample. Samples were then incubated at 50°C for 30 min in a water bath, the reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 mL of 1.0 M NaOH and the released ρ-nitrophenol was measured at 420 nm. For phytase, 400 μL of 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5) containing 1.2 mM sodium phytate was mixed with 250 μL of enzyme sample. Samples were then incubated for 30 min at 50°C in a water bath, the reaction was stopped by adding 100 μL of 20% trichloroacetic acid solution. An aliquot was analyzed to determine the liberated inorganic phosphate (Pi) by the ammonium molybdate method, OD at 420 nm (Tanner and Barnett 1986). One unit of acid phosphatase or phytase (Ph U/mL) was defined as 1.0 μM of ρ-nitrophenol or 1.0 μM of Pi liberated per minute under assay conditions.

Statistical analysis

Each experimental test was conducted three times in randomized block design to evaluate the effect of metal ions on the enzymatic activity of L. reuteri in SPM. Mean values and standard deviations were calculated from the triplicate tested samples. R Project for Statistical Computing version R-2.15.2 (http://www.r-project.org) was used to determine significance of differences in the effect of metal ions on the enzymatic activity of the tested L. reuteri strains and significance of differences in the enzymatic activity among strains using one way and multi-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results and discussions

Effect of metal ions on the growth of Lactobacillus reuteri

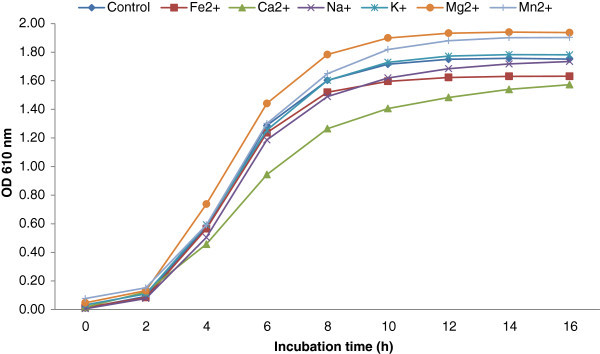

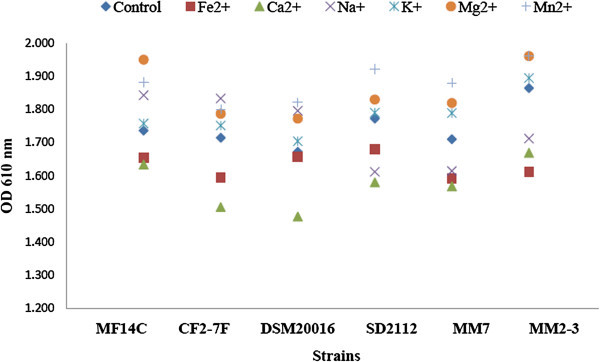

The growth of L. reuteri was monitored using OD at 610 nm. Figure 1 shows average growth rates of L. reuteri strains growing in SPM with added metal ions during 16 h of incubation at 37°C. In the control samples, strains of L. reuteri continued to grow and reached an average of 1.75 OD (610 nm) within 16 h of incubation at 37°C. The addition of Mg2+ or Mn2+ to SPM enhanced the growth of L. reuteri to reach an average of 1.94 and 1.90 OD (610 nm) respectively. Fe2+ and Ca2+ slows down the growth of L. reuteri to reach an average of 1.63 and 1.57 OD (610 nm) respectively. Similar growth curves were shown for the strains of L. reuteri in the presence of Na+ and K+ as control group. All tested strains of L. reuteri grew better in SPM with added Mn2+ or Mg2+, and they grew slower in SPM with added Fe2+ and Ca2+ compared to their in control (Figure 2). The addition of Na+ to SPM enhanced the growth of MF14-C, CF2-7F, and DSM20016 but slowed down the growth of SD2112, MM7, and MM2-3. K+ showed only slight effect on the growth of the tested strains.

Figure 1.

Effect of adding metal ions on the growth pattern ofL. reuteri(results of six strains ofL. reuteriwere pooled for each metal ion).

Figure 2.

Effect of adding metal ions on the growth ofL. reuteristrains after 16 h of incubation.

The enhancement L. reuteri growth by Mn2+ and Mg2+ can be explained by that these metal ions are essential for the growth of Lactobacillus (Boyaval 1989; Letort and Juillard 2001; Wegkamp et al. 2010). Mn2+ helps the cell to deal with reactive oxygen species and serves as an alternative for the absence of a gene encoding a superoxide dismutase (Wegkamp et al. 2010). Mg2+ was earlier found to stimulates the growth of Lactobacillus and improve its survival (Amouzou et al. 1985). It was shown that Mg2+ is the only essential oligoelement for the growth of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis (Hébert et al. 2004). Mg2+ and Mn2+ were found to be essential minerals for the growth of L. plantarum (Wegkamp et al. 2010). In this experiment we are reporting the enhancement of L. reuteri growth by Mn2+ and Mg2+.

Induction of α-glucosidase by metal ions

In control group, α-glucosidase activity produced by L. reuteri ranged between 20.65 ± 1.70 and 40.06 ± 2.80 Glu U/mL for MM2-3 and MF14-C respectively (Table 2). In the presence of Mg2+, α-glucosidase produced by L. reuteri MM2-3 was increased by 23.46 units to reach 44.11 ± 3.20 Glu U/mL. L. reuteri MF14-C grown in the presence of Mg2+ showed the highest α-glucosidase activity (61.74 ± 3.09 Glu U/mL) compared to other strains. The addition of Mn2+ also enhanced α-glucosidase activity L. reuteri MM2-3 and MF14-C to reach 41.42 ± 3.66 and 58.31 ± 2.88 respectively. Mn2+ enhanced α-glucosidase activity for all L. reuteri strains except CF2-7F. On the other hand, the addition of K+ reduced α-glucosidase of MF14-C to reach 13.71 ± 1.70 Glu U/mL. The growth of L. reuteri in the presence of K+ led to a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in α-glucosidase activity in all strains. The addition of Fe2+ also reduced α-glucosidase of MF14-C, 25.90 ± 2.72 Glu U/mL. Fe2+ decreased α-glucosidase activity of all L. reuteri strains except DSM20016 and MM2-3. Ca2+ enhanced α-glucosidase activity of DSM20016, MM7, and MM2-3 and decreased the activity of MF14-C, CF2-7F, and SD2112. Na+ enhanced α-glucosidase activity for all L. reuteri strains except MF14-C which was not affected.

Table 2.

Effect of metal ions onα-glucosidase activity (Glu U/mL) produced byL. reuteri

| α-Glucosidase activity (Glu U/mL)* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. reuteri | Control | Fe2+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | K+ | Mg2+ | Mn2+ |

| MF14-C | 40.06 | 25.90 | 26.32 | 38.38 | 13.71 | 61.74 | 58.31 |

| ±2.80bA | ±2.72cA | ±3.50cB | ±1.98bB | ±1.70dBC | ±3.09aA | ±2.88aA | |

| CF2-7F | 34.38 | 20.48 | 25.20 | 47.59 | 10.52 | 46.30 | 32.83 |

| ±1.36bB | ±1.75cB | ±1.83cB | ±1.86aA | ±1.30dC | ±2.64aB | ±2.91bC | |

| DSM20016 | 31.80 | 30.20 | 41.69 | 46.14 | 26.22 | 50.64 | 55.52 |

| ±2.01dBC | ±2.27dA | ±2.89cA | ±2.66bcA | ±1.09dA | ±1.30aB | ±4.68aA | |

| SD2112 | 29.34 | 19.54 | 20.57 | 34.58 | 15.59 | 35.51 | 40.55 |

| ±1.27cC | ±3.89 dB | ±1.82dC | ±2.32abB | ±1.11dB | ±2.74abC | ±1.90aB | |

| MM7 | 25.32 | 19.40 | 35.93 | 37.57 | 12.59 | 28.13 | 35.68 |

| ±2.32cdCD | ±1.75deB | ±3.62abA | ±4.39aB | ±1.83eBC | ±3.22bcD | ±2.63abC | |

| MM2-3 | 20.65 | 18.28 | 24.79 | 24.98 | 14.79 | 44.11 | 41.42 |

| ±1.70bcE | ±1.49bcB | ±2.72bB | ±2.30bC | ±2.60eB | ±3.20aB | ±3.66aB | |

*Data points with different lower case letters in the same row are significantly (p < 0.05) different. Data points with different upper case letters in the same column are significantly (p < 0.05) different.

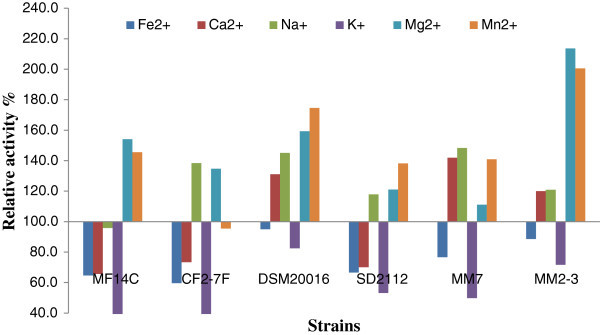

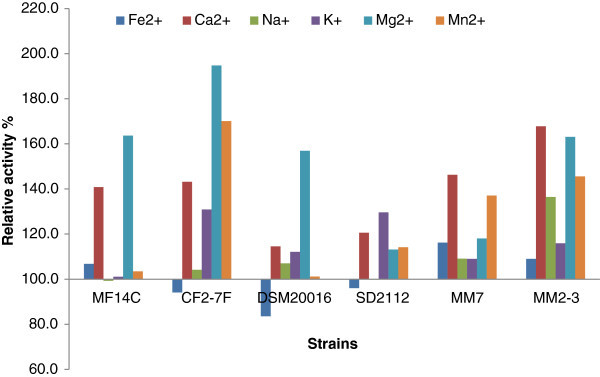

Figure 3 shows the relative activity (%) of α-glucosidase produced by L. reuteri in the presence of metal ions. α-Glucosidase activity of MM2-3 growing in SPM with the addition of Mg2+ and Mn2+ was increase by 113.6% and 100.6% respectively. Mg2+ and Mn2+ also increased α-glucosidase activity of DSM20016 (by 59.2 and 74.6%) and MF14-C (by 54.1 and 45.6%) respectively. Mg2+ and Mn2+ were also found earlier to stimulate α-glucosidase activity of L. acidophilus(Li and Chan 1983). The addition of Na+ also enhanced α-glucosidase activity of the tested L. reuteri strains while showing less effect than Mg2+ and Mn2+. On the other hand, the growth of L. reuteri in SPM with added K+ led to a decrease in α-glucosidase ranged between 17.5 – 65.8%. Thus the effect of metal ions on α-glucosidase activity of L. reuteri is strain specific. These results come in agreement with previous studies. For example, α-glucosidase produced by L. rhamnosus R was inhibited by Hg2+, Mn2+, Cu2+, Fe2+ and Zn2+ and slightly activated by Li+, Na+, K+, Ca2+, Co2+, and Mg2+ (Pham et al. 2000). In addition, our results suggest the use of MF14-C and DSM20016 in the presence of Mg2+ and Mn2+ to produce enhanced levels of α-glucosidase.

Figure 3.

Relative activity (%) ofα-glucosidase produced byL. reuterigrown is SPM with added metal ions compared to the control group without metal ions. The relative activity was calculated as the enzymatic activity in SPM with added metal ions divided by the enzymatic activity in SPM without metal ions then multiplied by 100.

Induction of β-glucosidase by metal ions

In control group, β-glucosidase activity of L. reuteri ranged between 6.94 ± 1.29 and 17.82 ± 1.45 Glu U/mL for MF14-C and MM2-3 respectively (Table 3). The addition of K+ increased β-glucosidase produced by L. reuteri MF14-C and MM2-3 to reach 13.71 ± 1.70 and 24.79 ± 2.60 Glu U/mL respectively. K+ also increased β-glucosidase L. reuteri DSM20016 to reach the highest activity among the tested strains, 26.22 ± 1.09 Glu U/mL. The addition of Ca2+ or Fe2+ to SPM significantly (p < 0.05) enhanced β-glucosidase activity in all tested strains. Mg2+ and Mn2+ also enhanced β-glucosidase activity in the tested strains but showed lower enhancement effect compared to Ca2+, Fe2+ or K+. The lowest β-glucosidase with metal ions was produced by L. reuteri MF14-C in the presence of Ca2+ (9.66 ± 2.17 Glu U/mL). Thus, the addition of metal ions to SPM could enhance β-glucosidase activity of L. reuteri.

Table 3.

Effect of metal ions onβ-glucosidase activity (Glu U/mL) produced byL. reuteri

| β-Glucosidase activity (Glu U/mL)* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. reuteri | Control | Fe2+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | K+ | Mg2+ | Mn2+ |

| MF14-C | 6.94 | 11.46 | 9.66 | 11.18 | 13.71 | 10.15 | 12.30 |

| ±1.29cC | ±1.66abC | ±2.17bC | ±1.60abC | ±1.70aBC | ±1.74bD | ±1.29aB | |

| CF2-7F | 10.11 | 18.02 | 21.93 | 16.86 | 10.52 | 13.60 | 16.71 |

| ±1.58cB | ±2.21aAB | ±2.05aA | ±1.12abB | ±1.30cD | ±1.13bC | ±1.93abA | |

| DSM20016 | 12.04 | 21.05 | 22.45 | 18.24 | 26.22 | 20.57 | 16.87 |

| ±1.05dB | ±2.23bA | ±1.70bA | ±1.75bcB | ±1.09aA | ±1.28bAB | ±1.08cdA | |

| SD2112 | 7.59 | 17.21 | 17.44 | 10.46 | 15.59 | 17.50 | 13.28 |

| ±1.20cdC | ±1.94aAB | ±1.90aB | ±1.69cC | ±1.11abB | ±1.72aBC | ±1.50bcB | |

| MM7 | 7.92 | 19.32 | 17.57 | 12.37 | 12.59 | 14.28 | 9.82 |

| ±0.88cC | ±2.94aAB | ±1.70aB | ±1.75bC | ±1.83bCD | ±1.60abC | ±1.68cC | |

| MM2-3 | 17.82 | 23.60 | 22.70 | 23.48 | 24.79 | 22.57 | 17.52 |

| ±1.45bA | ±2.27aA | ±3.27aA | ±3.21aA | ±2.60aA | ±3.24aA | ±2.06bA | |

*Data points with different lower case letters in the same row are significantly (p < 0.05) different. Data points with different upper case letters in the same column are significantly (p < 0.05) different.

The growth of L. reuteri in the presence of metal ions led to relative change in β-glucosidase ranged between -1.7 to 143.9% (Figure 4). The addition of Fe2+ enhanced β-glucosidase activity produced by L. reuteri MM7 and L. reuteri SD2112 by 143.9% and 126.7% respectively. Ca2+ enhanced β-glucosidase activity produced by L. reuteri MM7 and L. reuteri SD2112 by 121.8% and 129.8% respectively. The addition of K+ enhanced β-glucosidase produced by L. reuteri CF2-7F and L. reuteri SD2112 by 4.1% and 117.8% respectively. The effect of metal ions on β-glucosidase activity of L. reuteri MM2-3 was relatively low compared to other strains. Thus, the effect of metal ions on β-glucosidase activity produced by L. reuteri is strain dependent. Previous studies also showed that the effect of metal ions on β-glucosidase activity varied with the bacterial strain and type of metal ions (Pham et al. 2000). The effect of metal ions on β-glucosidase may be explained by that the bacterial sources of β-glucosidase have the highest activity and the most tolerance to inhibitors such as metal ions compare to other sources (Jeng et al. 2011). The growth of L. reuteri DSM20016 or MM2-3 in the presence of K+ could be used to produce high quantity of β-glucosidase. Thus, our results suggest the addition of Ca2+ and Fe+2 to produce enhanced levels of β-glucosidase.

Figure 4.

Relative activity (%) ofβ-glucosidase produced byL. reuterigrown in SPM with added metal ions compared to the control group without metal ions. The relative activity was calculated as the enzymatic activity in SPM with added metal ions divided by the enzymatic activity in SPM without metal ions then multiplied by 100.

β-Glucosidase activity of L. reuteri was determined in the disrupted cells. However, β-glucosidase was also tested in the supernatant after removal of the cells but only trace of enzyme activity was detected (data not shown). Thus, β-glucosidase produced by the tested L. reuteri strains is mainly cell-associated enzyme. β-Glucosidase was also reported to be a cell-associated enzyme in L. acidophilus (Mahajan et al. 2010) and L. rhamnosus R (Pham et al. 2000). The absence of β-glucosidase in the supernatant may suggest that most of extracted enzyme could be inactivated when separated from the cells.

Induction of acid phosphatase by metal ions

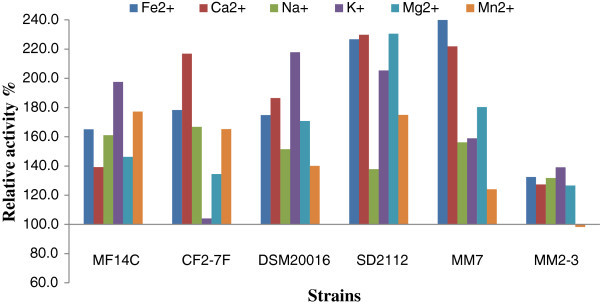

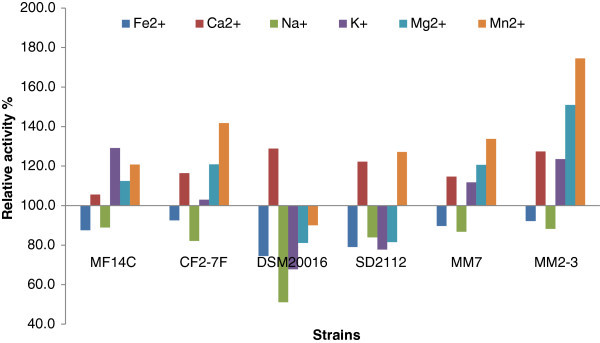

Acid phosphatase in control group ranged between 8.73 ± 1.11 and 20.56 ± 0.74 Ph U/mL (Table 4). The addition of Mg2+ enhanced acid phosphatase activity of L. reuteri DSM20016 to reach the highest activity among tested strains, 29.33 ± 2.36 Ph U/mL. Mg2+ caused significant (p < 0.05) increase in acid phosphatase activity in all tested strains. Acid phosphatase produced by L. reuteri SD2112 was significantly (p < 0.05) increased in the presence of K+ or Ca2+ to reach 26.64 ± 1.39 and 24.78 ± 0.91 Ph U/mL respectively. The addition of Mn2+ increased acid phosphatase activity of L. reuteri CF2-7F by 10.1 units to reach 24.29 ± 2.54 Ph U/mL. Figure 5 shows the relative effect of metal ions on acid phosphatase. Acid phosphatase produced by L. reuteri CF2-7F was increased by 94.7% and 70.1% in the presence of Mg2+ and Mn2+ respectively. The addition of Ca2+ led to enhance acid phosphatase activity in L. reuteri MM2-3 by 67.8%. Fe2+ and Na+ caused only slight effect (decrease or increase) on acid phosphatase. For example Fe2+ decreased acid phosphatase activity of L. reuteri DSM20016 by 16.5%.

Table 4.

Effect of metal ions on acid phosphatase activity (Ph U/mL) produced byL. reuteri

| Acid phosphatase activity (Ph U/mL)* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. reuteri | Control | Fe2+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | K+ | Mg2+ | Mn2+ |

| MF14-C | 13.59 | 14.51 | 19.14 | 13.49 | 13.74 | 22.24 | 14.06 |

| ±1.51bB | ±1.24bB | ±1.51aB | ±0.98bB | ±0.74bC | ±2.49aB | ±0.90bC | |

| CF2-7F | 14.28 | 13.44 | 20.45 | 14.88 | 18.69 | 27.81 | 24.29 |

| ±1.2cB | ±1.11cB | ±2.16abB | ±1.57cB | ±1.16bB | ±2.43aAB | ±2.54aA | |

| DSM20016 | 18.69 | 15.61 | 21.41 | 20.00 | 20.96 | 29.33 | 18.91 |

| ±1.15bcA | ±2.40cB | ±2.01bB | ±1.27bA | ±2.19bB | ±2.36aA | ±1.95bcB | |

| SD2112 | 20.55 | 19.73 | 24.78 | 20.50 | 26.64 | 23.25 | 23.46 |

| ±0.74bA | ±0.36bA | ±0.91aA | ±0.95bA | ±1.39aA | ±2.38aB | ±2.07aA | |

| MM7 | 12.60 | 14.65 | 18.43 | 13.75 | 13.74 | 14.88 | 17.27 |

| ±1.63cB | ±0.98abB | ±2.66aB | ±2.37bcB | ±1.20bcC | ±1.31abC | ±2.53aBC | |

| MM2-3 | 8.73 | 9.52 | 14.65 | 11.91 | 10.12 | 14.24 | 12.71 |

| ±1.11cC | ±1.14bcC | ±1.21aC | ±1.41abBC | ±1.31bcD | ±1.49aC | ±1.37abCD | |

*Data points with different lower case letters in the same row are significantly (p < 0.05) different. Data points with different upper case letters in the same column are significantly (p < 0.05) different.

Figure 5.

Relative activity (%) of acid phosphatase produced byL. reuterigrown in SPM with added metal ions compared to the control group without metal ions. The relative activity was calculated as the enzymatic activity in SPM with added metal ion divided by the enzymatic activity in SPM without metal ions then multiplied by 100.

The relative activity data suggested that the addition of Mg2+, Ca2+, or Mn2+ may lead to high increase in acid phosphatase. Mn2+ was reported to stimulate phosphatase activity which was explained by the fact that many protein phosphatases contain Mn2+ (Pallen and Wang 1985). However, the effect of metal ions on acid phosphatase produced by L. reuteri was found to be a strain dependent. Previous studies also showed that the effect of metal ions on acid phosphatase activity varied with bacterial strain (Aqel 2012; Palacios et al. 2005).

Induction of phytase by metal ions

Phytase activity in control group ranged between 0.51 ± 0.04 and 0.90 ± 0.05 Ph U/mL (Table 5). The growth of L. reuteri DSM20016 in the presence of Ca2+ led to the highest phytase activity, 1.16 ± 0.20 Ph U/mL. Phytase activity of L. reuteri SD2112 reached 1.03 ± 0.06 Ph U/mL in the presence of Mn2+. The addition of Ca2+ or Mn2+ to SPM enhanced phytase activity in all tested strains. On the other hand, phytase activity of L. reuteri DSM20016 was significantly (p < 0.05) decreased in the presence of Na+ to reach 0.46 ± 0.15 Ph U/mL. Phytase produced by L. reuteri DSM20016 was also reduced by Fe2+, K+, and Mg2+. Figure 6 shows the relative activity of L. reuteri in the presence of metal ions. Phytase produced by MM2-3 was increased by 74.5% in the presence of Mn2+. The addition Mg2+ enhanced phytase activity of MM2-3 by 51.0% and caused slight increase or decrease in the other strains. The addition of K+ enhanced phytase activity of MF14-C and MM2-3 and decreased phytase activity of DSM20016 and SD2112. Thus, our results suggested the addition of Mg2+, Mn2+, and Ca2+ to the culture media of L. reuteri to enhance the production of phytase. In addition, the effect of metal ions on phytase activity of L. reuteri was found to be a strain dependent.

Table 5.

Effect of metal ions on phytase activity (Ph U/mL) produced byL. reuteri

| Phytase activity (Ph U/mL)* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. reuteri | Control | Fe2+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | K+ | Mg2+ | Mn2+ |

| MF14-C | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.87 |

| ±0.08bcBC | ±0.06cA | ±0.11abBC | ±0.05cAB | ±0.08aA | ±0.05abA | ±0.05abB | |

| CF2-7F | 0.67 | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.95 |

| ±0.05bcC | ±0.07bcA | ±0.08bB | ±0.04cB | ±0.05bBC | ±0.06bA | ±0.06aA | |

| DSM20016 | 0.90 | 0.67 | 1.16 | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.81 |

| ±0.05abA | ±0.04cA | ±0.20aA | ±0.15cBC | ±0.23bcBC | ±0.19bAB | ±0.17abA | |

| SD2112 | 0.81 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 1.03 |

| ±0.06bAB | ±0.05cA | ±0.06aA | ±0.03bcA | ±0.04cBC | ±0.08bcB | ±0.06aA | |

| MM7 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.78 | 0.59 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.91 |

| ±0.04bcC | ±0.06cA | ±0.06abB | ±0.09cB | ±0.06abB | ±0.04aA | ±0.14aAB | |

| MM2-3 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.63 | 0.77 | 0.89 |

| ±0.04cD | ±0.04cB | ±0.04bC | ±0.03cC | ±0.11bBC | ±0.05bAB | ±0.03aB | |

*Data points with different lower case letters in the same row are significantly (p < 0.05) different. Data points with different upper case letters in the same column are significantly (p < 0.05) different.

Figure 6.

Relative activity (%) of phytase produced byL. reuterigrown in SPM with added metal ions compared to the control group without metal ions. The relative activity was calculated as the enzymatic activity in SPM with added metal ion divided by the enzymatic activity in SPM without metal ions then multiplied by 100.

The effect of metal ions on phytase activity of Lactobacillus was also investigated in previous studies. The addition of Ca2+ was previously reported to enhance phytase activity of Lactobacillus (Tang et al. 2010) and the addition of Fe2+ strongly inhibited phytase activity of L. sanfranciscensis (De Angelis et al. 2003). On the other hand, phytase activity of L. reuteri was found low compared to other tested enzymes. Lactobacillus strains had higher activity against ρ-nitrophenyl phosphate than phytate (Palacios et al. 2005). In addition, phytase does not seem to be common in Lactobacillus strains and phytase activity of Lactobacillus is generally low compared to other bacterial genera (De Angelis et al. 2003; Palacios et al. 2005). However, phytase and acid phosphatase are particular subgroups of phosphatases, whereas phytase exhibits a preference for phytate. The specificity of both acid phosphatase and phytase can partially overlap since acid phosphatase also shows phytase activity (Simon and Igbasan 2002). Thus, both acid phosphatase and phytase can be useful in the degradation of phytate.

Conclusion

We studied the growth and enzymatic activity of L. reuteri in SPM. Our results demonstrate that the enzymatic activity of L. reuteri is strain dependent. α-Glucosidase activity of L. reuteri MFI4-C and DSM20016 was enhanced by Mg2+ and Mn2+. The addition of Ca2+, Fe+2, or K+ can enhance β-glucosidase activity of L. reuteri SD2112, DSM20016, and MM7. Acid phosphatase and phytase produced by MM2-3, CF2-7F, or MM7 could be increased by the addition of Mg2+, Ca2+, and Mn2+. Thus, to maximize the production of a target enzyme, it is required to select a combination of specific strain and specific metal ion. Nevertheless, Mn2+ and Mg2+ could be added to the culture media of L. reuteri to enhance the growth and enzymatic activity. Our results also revealed that more attention should be given to L. reuteri DSM20016 as high enzymatic activity is associated with this strain. Further studies need to done to investigate the optimum concentrations and possible combinations of metal ions that could be used to maximize the enzymatic activity of L. reuteri.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by grant number NC.X-267-5-12-170-1 from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily response the official view of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture. The authors like to thank: Dr. K. Schimmel, for his support while conducting this work.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors’ contributions

SAH and SAI defined the research theme, experimental design, samplings, reviewed the literature, conducted the research experiments, interpret the results, and wrote the manuscript. AS and MW helped with the experimental design, data interpretation, and manuscript writing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Saeed A Hayek, Email: safesaeed@yahoo.com.

Aboghasem Shahbazi, Email: ash@ag.ncat.edu.

Mulumebet Worku, Email: worku@ncat.edu.

Salam A Ibrahim, Email: ibrah001@ncat.edu.

References

- Alazzeh AY, Ibrahim SA, Song D, Shahbazi A, AbuGhazaleh AA. Carbohydrate and protein sources influence the induction of α-and β-galactosidases in Lactobacillus reuteri. Food Chem. 2009;117:654–659. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.04.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amouzou K, Prevost H, Divies C. Effects of milk magnesium supplementation on lactic acid fermentation by Streptococcus lactis and Streptococcus thermophilus. Le Lait. 1985;65:21–34. doi: 10.1051/lait:1985647-6482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aqel H. Effects of pH-Values, temperatures, sodium chloride, metal ions, sugars and Tweens on the acid phosphatase activity by thermophilic Bacillus strains. Eur J Sci Res. 2012;75:262–268. [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R, Lahtinen SJ, Ibrahim F, Ouwehand AC. Genus lactobacilli. In: Lahtinne S, Salminen S, Von Wright A, Ouwehand A, editors. Lactic acid bacteria: microbiological and functional aspects. 1. London: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boyaval P. Lactic acid bacteria and metal ions. Lait. 1989;69:87–113. doi: 10.1051/lait:198927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broihier K. Sweet potato: tuber delivers top-notch nutrition. Environ Nutr. 2006;29:8–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bury D, Jelen P, Geciova J. Effect of yeast extract supplementation on beta-galactosidase activity of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus 11842 grown in whey. Czech J Food Sci. 2001;19:166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Casas IA, Dobrogosz WJ. Validation of the probiotic concept: Lactobacillus reuteri confers broad-spectrum protection against disease in humans and animals. Microb Ecol Health D. 2000;12:247–285. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis M, Gallo G, Corbo MR, McSweeney PL, Faccia M, Giovine M, Gobbetti M. Phytase activity in sourdough lactic acid bacteria: purification and characterization of a phytase from Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis CB1. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003;87:259–270. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyawali R, Ibrahim SA. Impact of plant derivatives on the growth of foodborne pathogens and the functionality of probiotics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;95:29–45. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haros M, Bielecka M, Honke J, Sanz Y. Phytate-degrading activity in lactic acid bacteria. Polish J Food Nutr Sci. 2008;58:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek SA. Use of sweet potato to develop a medium for cultivation of lactic acid bacteria. North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University: Dissertation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek SA, Ibrahim SA. Food Nutr Sci. 2013. Current limitations and challenges with lactic acid bacteria: a review. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek SA, Shahbazi A, Awaisheh SS, Shah NP, Ibrahim SA. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013. Sweet potato as a basic component in developing a medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert EM, Raya RR, Giori GS. Nutritional requirements of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis in a chemically defined medium. Currunt Microbiol. 2004;49(5):341–345. doi: 10.1007/s00284-004-4357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim SA, Alazzeh AY, Awaisheh SS, Song D, Shahbazi A, AbuGhazaleh AA. Enhancement of α-and β-galactosidase activity in Lactobacillus reuteri by different metal ions. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2010;136(1):106–116. doi: 10.1007/s12011-009-8519-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal TH, Lewis KO, Cooper BT. Phytase activity in the human and rat small intestine. Gut. 1994;35(9):1233–1236. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.9.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng WY, Wang NC, Lin MH, Lin CT, Liaw YC, Chang WJ, Liu CI, Liang PH, Wang AHJ. Structural and functional analysis of three β-glucosidases from bacterium Clostridium cellulovorans, fungus Trichoderma reesei and termite Neotermes koshunensis. J Struct Biol. 2011;173:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralj S, Stripling E, Sanders P, van Geel-Schutten GH, Dijkhuizen L. Highly hydrolytic reuteransucrase from probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri strain ATCC 55730. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(7):3942–3950. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3942-3950.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasikov VV, Karelov DV, Firsov LM. α-Glucosidases. Biochem (Moscow) 2001;66(3):267–281. doi: 10.1023/A:1010243611814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letort C, Juillard V. Development of a minimal chemically defined medium for the exponential growth of Streptococcus thermophilus. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;91(6):1023–1029. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li KB, Chan KB. Production and properties of α-glucosidase from Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46(6):1380–1387. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.6.1380-1387.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-González AA, Grases F, Roca P, Mari B, Vicente-Herrero MT, Costa-Bauzá A. Phytate (myo-inositol hexaphosphate) and risk factors for osteoporosis. J Med Food. 2008;11(4):747–752. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan PM, Desai KM, Lele SS. Production of cell membrane-bound α-and β-glucosidase by Lactobacillus acidophilus. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2010;5:706–718. doi: 10.1007/s11947-010-0417-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otieno DO, Ashton JF, Shah NP. Stability of β-glucosidase activity produced by Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus spp. in fermented soymilk during processing and storage. J Food Sci. 2005;70(4):M236–M241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb07194.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozimek LK, Euverink GJW, Van Der Maarel MJEC, Dijkhuizen L. Mutational analysis of the role of calcium ions in the Lactobacillus reuteri strain 121 fructosyltransferase (levansucrase and inulosucrase) enzymes. FEBS Let. 2005;579(5):1124–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmaja G. Uses and nutritional data of sweetpotato. In: Loebenstein G, Thottappilly G, editors. The Sweetpotato. Belgium, Germany: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios MC, Haros M, Rosell CM, Sanz Y. Characterization of an acid phosphatase from Lactobacillus pentosus: regulation and biochemical properties. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;98(1):229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios MC, Haros M, Sanz Y, Rosell CM. Selection of lactic acid bacteria with high phytate degrading activity for application in whole wheat breadmaking. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2007;41:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2007.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pallen CJ, Wang JH. A multifunctional calmodulin-stimulated phosphatase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;237(2):281–291. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham P, Dupont I, Roy D, Lapointe G, Cerning J. Production of exopolysaccharide by Lactobacillus rhamnosus R and analysis of its enzymatic degradation during prolonged fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(6):2302–2310. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.6.2302-2310.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra P, Halami PM. Screening, selection and characterization of phytic acid degrading lactic acid bacteria from chicken intestine. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;133:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez H, Curiel JA, Landete JM, de las Rivas B, de Felipe FL, Gómez-Cordovés C, Mancheño JM, Muñoz R. Food phenolics and lactic acid bacteria. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;132(2–3):79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sestelo ABF, Poza M, Villa TG. β-Glucosidase activity in a Lactobacillus plantarum wine strain. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;20:633–637. doi: 10.1023/B:WIBI.0000043195.80695.17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon O, Igbasan F. In vitro properties of phytases from various microbial origins. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2002;37(7):813–822. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2621.2002.00621.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Ibrahim S, Hayek S. Recent application of probiotics in food and agricultural science. In: Rigobelo EC, editor. Probiotics. 1. Manhattan NY: InTech; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tang AL, Wilcox G, Walker KZ, Shah NP, Ashton JF, Stojanovska L. Phytase activity from Lactobacillus spp. in calcium-fortified soymilk. J Food Sci. 2010;75(6):M373–M376. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner JT, Barnett SA. Methods of analysis of infant formula: food and drug administration and infant formula council collaborative study, phase III. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1986;69:777–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham S, Chang C, Huang H, Lee Y, Huang T, Chang C. Biochemical characterization of an acid phosphatase from Thermus thermophilus. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74:727–735. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegkamp A, Teusink B, De Vos WM, Smid EJ. Development of a minimal growth medium for Lactobacillus plantarum. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2010;50(1):57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotta T, Ricciardi A, Parente E. Enzymatic activities of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Cornetto di Matera sourdoughs. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;115:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotta T, Parente E, Ricciardi A. Viability staining and detection of metabolic activity of sourdough lactic acid bacteria under stress conditions. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;25(6):1119–1124. doi: 10.1007/s11274-009-9972-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]