Abstract

Objectives

To investigate microRNAs (miRNAs) in urinary exosomes and their association with an individual’s blood pressure response to dietary salt intake.

Design and methods

Human urinary exosomal miRNome was examined by microarray.

Results

Of 1898 probes tested, 194 miRNAs were found in all subjects tested. 45 miRNAs had significant associations with salt sensitivity or inverse salt sensitivity.

Conclusion

The expression of 45 urinary exosomal miRNAs associates with an individual’s blood pressure response to sodium.

Keywords: miRNA, Exosome, Blood pressure, Salt-sensitive, Salt-resistant

Introduction

Salt sensitivity of blood pressure (BP) is associated with higher incidence of cardiovascular disease independent of hypertension [1]; however, it is difficult to diagnose. The paradoxical decrease in BP following high salt intake, which we term “inverse salt sensitivity” also may be associated with increased cardiovascular disease and mortality if sufficient salt intake is not maintained [2]. For these latter individuals, low salt intake will cause an increase in their BP. The most effective method in diagnosing either condition is using an extensive two-week dietary protocol [3]. Finding a simpler method to correctly diagnose these conditions is critical since salt sensitivity affects approximately 25% of the population and inverse salt sensitivity may affect up to 15% [2]. Urinary exosomes provide a unique view of renal metabolic activity and may provide a valuable source for diagnostic biomarkers [2,4].

Exosomes are 50–90 nm membrane-derived vesicles found in bodily fluids including blood, saliva, and urine. They encapsulate proteins and mRNA as well as miRNA that may be exchanged as a signaling mechanism between cells [5]. Encapsulated mRNA and miRNA are relatively stable because exosomes protect nucleic acids from extra-cellular degradation [6,7].

miRNAs have been characterized previously in total urine specimens and exosomes from body fluids other than urine, but have yet to be studied in urinary exosomes. Advances have been made in understanding the role of miRNAs in cancer pathogenesis, but less is known about their role in other chronic diseases. Studies have been reported associating certain miRNAs with hypertension [8] but miRNAs have not yet been directly linked to sodium metabolism.

Potentially, miRNAs may be exchanged between tubule segments via exosomes to alter sodium metabolism in various nephron segments.

To characterize the urinary exosome miRNome, we used microarrays to explore the miRNA spectrum present within urinary exosomes from ten individuals that had completed our salt sensitivity clinical study. We picked individuals at the two extremes as well as the middle of the continuous variable of salt sensitivity. One group of individuals had a dramatic increase in BP when consuming a high sodium diet, i.e. salt-sensitive. Another group, termed inverse salt-sensitive, had the opposite response to salt, i.e. their BP dramatically dropped while consuming a high sodium diet. These two groups exhibiting extremes of salt sensitivity of BP were compared to a group of normal individuals who fell in the middle of this continuum. These normal control individuals had BP that did not change dependent on sodium consumption, i.e. they were salt-resistant. In the microarray, potential biomarkers were sought based on these three phenotypes, defined in more detail below.

Materials and methods

Research participants

Ten Caucasian subjects previously evaluated for their BP response to controlled sodium intake [3] were asked to participate in this study one to five years after their initial classification. The study protocol and informed consent documents were approved by the UVA Institutional Review Board. The three phenotypes identified were: salt-sensitive (SS, N = 3) who showed a ≥7 mm Hg increase in mean arterial pressure (MAP) transitioning from a low to high sodium diet (mean ΔMAP = +17.5 mm Hg); salt-resistant (SR, N = 4) who had <7 mm Hg change in MAP following any change in sodium intake (i.e. our normal or control group); and inverse salt-sensitive (ISS, N = 3) whose MAP decreased ≥7 mm Hg transitioning from a low to high sodium diet (mean ΔMAP = −12.7 mm Hg) [2,9]. Random urine samples were pooled from three to four independent collections from each subject. Two independent miRNA analyses were performed by microarray.

Exosome purification

The ultracentrifugation protocol to isolate exosomes from urine samples was followed according to Gonzales et al. [10] with the following modifications: 1) protease inhibitors were not used because miRNA was the target and 2) the first centrifugation step to remove whole cells and debris was performed for 30 min rather than 10 min to ensure maximum purity. Urine specimens were processed as quickly as possible after voiding (<4 h) or frozen at −80 °C until processed. Previous studies had demonstrated that miRNA is stable for 24 h in urine at room temperature [11]. After exosome pellets were resuspended in Phosphate Buffered Saline, total RNA was isolated using a miRNeasy kit (Qiagen). Samples were stored individually at −80 °C until microarray analysis was performed.

miRNome analysis

Three to four collections per individual were pooled in order to reach the 5μg miRNA minimum required for enrichment and pre-amplification by a commercial firm (LC Sciences, Houston, TX). Individual miRNA expression was analyzed using microarray (miRBase Human: Version 18). To test for analytical variability of the miRNA microarray chips, each pooled specimen from 5 individuals was split into two aliquots and each aliquot was analyzed twice. To get a preliminary understanding of biological variability, we collected and pooled specimens from the same 5 individuals (3 months later) and repeated the procedure of splitting the pools into two aliquots and analyzing them in duplicate. The other 5 individuals were examined once in this second run.

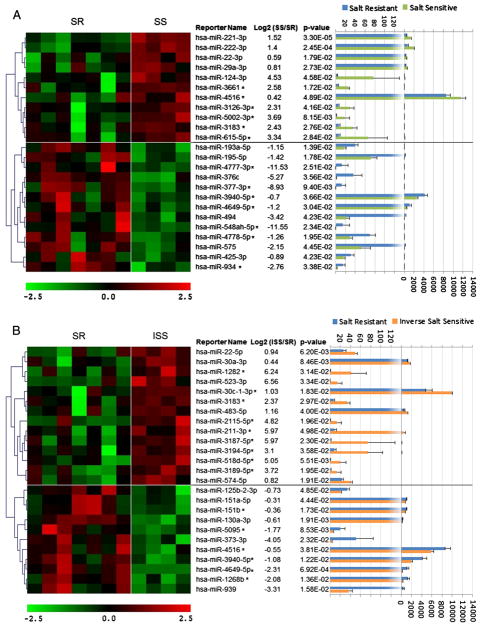

We compared the data from 10 individuals that fell into the three salt-sensitive phenotypes, 4 individuals that showed a normal response to salt (SR), 3 that were SS and 3 that were ISS. The graphs are displayed as SS individuals compared to SR individuals (Fig. 1A), and ISS individuals compared to SR individuals (Fig. 1B). Data from selected datasets were averaged and presented as mean ± standard error of means. Statistical significance was determined using both Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Holm–Sidak correction for multiple comparisons that was applied to compare the different groups. In our figure, we report P values from the Student’s t-test; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Differential miRNA expression in urine exosomes. miRNA expression patterns of 11 pooled urines were analyzed using miRBase version 18 microarray. In the heat maps on the left, each column corresponds to the relative expression profile of a pooled urine sample from an individual previously indexed for their blood pressure response to salt. Replicates of specimens per individual are included in the heat map. Student’s t-test was used to identify mature miRNAs that were significantly different between subjects (P < 0.05). Panel A shows the 24 miRNAs that were different between the Salt-Resistant (SR) and Salt-Sensitive (SS) individuals. The 11 miRNAs above the horizontal line showed increased expression in the SS vs. the SR group, and the 13 miRNAs below that line showed decreased expression compared to the SR control. Panel B shows an additional 21 miRNAs that were different between the Salt-Resistant (SR) and Inverse Salt-Sensitive (ISS) individuals. The miRNAs are positioned similarly to panel A, i.e. those with increased expression compared to the SR control are above the ones with decreased expression. To the right of the reporter name, asterisks indicate 13 miRNAs in panel A and 11 additional miRNAs in panel B that have not previously been reported to be circulating. The bar graph on the right (with corresponding P-values) displays the absolute RFU of each specific miRNA probe. The top axis displays the values for the low expressers, and a different scale is used on the bottom axis for the high expressing miRNAs, to label the bars to the right of the dotted line. The microarray hierarchical cluster analysis is depicted along the left edge of the figure by grouping genes that had the most similar expression patterns.

RT-PCR assays

miRNA that was extracted from all 10 subjects was also analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR using the miScript PCR System by Qiagen. 80 ng of the same RNA samples analyzed by microarray were first reverse transcribed (miScript II RT Kit, Qiagen). In order to confirm the microarray data, 2.5 ng of this DNA was measured by real-time PCR using mature miRNA-specific primers (specific miScript Primer Assay, miScript SYBR Green PCR kit, Qiagen) in a BioRad CFX connect real-time PCR machine, using standard manufacturer’s conditions. The 7 miRNAs that were picked to confirm the microarray results were: hsa-miR-1268b, hsa-miR-5002-3p, hsa-miR-4516, hsa-miR-3183, hsa-miR-3940-5p, hsa-miR-4649-5p, and a control hsa-miR-320a.

Results

Out of the 1898 unique miRNA probes examined by the chips for miRBase Version 18, a total of 194 were above background in all ten subjects. These 194 miRNAs replicated within individual aliquots and between the analytical runs performed 3 months apart. Of the 194 miRNAs detected, 45 were significantly different between the SS and SR individuals or between the ISS and SR subjects. The differences in urinary exosomal miRNAs between those groups replicated between pooled sample aliquots and also replicated between the analytical runs performed 3 months apart.

Four miRNAs shared expression differences between ISS or SS and their SR control. The only single miRNA that could differentiate the 2 extremes (salt sensitivity or inverse salt sensitivity) vs. the normal SR group was hsa-miR-4516. This was higher in SS and lower in ISS, compared to the SR control. One miRNA (hsa-miR-3183) was higher in SS and ISS vs. SR. 2 miRNA (hsa-miR-3940-5p, hsa-miR-4649-5p) were lower in SS and ISS vs. SR.

We searched the literature for each of the 45 miRNAs that were significantly different between SS or ISS vs. SR individuals, and found that only 21 were previously cited as extracellular secreted miRNAs in serum or other bodily fluids (http://atlas.dmi.unict.it/mirandola/index.html). The 24 miRNAs that have not been described as secreted from cells or found in body fluids are highlighted by asterisks in the 2 panels of Fig. 1. Currently, these miRNAs can be considered unique to urinary exosomes and strongly indicate that serum exosomal miRNAs do not pass into the urine in appreciable quantities.

Six of the mature miRNAs that showed significant differences using microarrays were verified using quantitative RT-PCR. Parallel significant differences were found using real-time RT-PCR that matches the micro-array analysis (P < 0.05 for each pairwise comparison). A 7th miRNA was also picked for this assay as a control. This showed no difference in the PCR between the SR and either SS or ISS, confirming the result seen in the microassay.

Our data demonstrate that there were significant differences in 45 miRNA concentrations in urinary exosomes, presumably derived from kidney tubule cells. The relative concentration of each miRNA is shown by pseudocolor representation on the heat maps at the left in each figure. There were dramatic differences between the various miRNA concentrations so the bar graph was made and scaled to accommodate these differences.

Discussion

These results provide the first examination of miRNAs present in urinary exosomes. Exosomes are membrane-derived vesicles that encapsulate cytoplasmic contents and thus provide a view of both membrane and cytoplasmic-based biomolecules, including miRNAs. Previous studies of circulating miRNAs excreted in urine have demonstrated association between presence of disease and changes in the concentration of urinary-selected miRNAs [11]. However, the interpretation that those miRNAs are biomarkers for kidney disease is complicated by the fact that urinary miRNA is composed of a combination of both filtered miRNA (derived from the blood) as well as kidney-derived miRNA. For our studies, we used urinary exosomes to exclude miRNA filtered from the blood because plasma exosomes are too large to pass through the glomerulus.

In our study, 24 of the 45 miRNAs that associated with salt sensitivity or inverse salt sensitivity have never been reported as secreted miRNAs. Some of the miRNAs that we identified as potential biomarkers for SS and ISS hypertension have been reported to regulate known pathways implicated in hypertension, including PPARγ[12], EGFR [13], TGFβ-1 [14] and PTEN/PI3K signaling [15]. Since changes in miRNA expression may occur early in disease pathogenesis, we postulate that urinary exosomal miRNAs may be useful biomarkers for individuals with aberrant sodium regulatory pathways [6]. In addition, each segment of the human nephron has distinct sodium regulatory functions and the transfer of miRNA from one tubule segment to more distal segments, as exosomes are carried along with the flow of urine, may mediate trans-tubular segment communication [16]. The identification of exosomal membrane markers in fractionated nephron-specific exosomes will shed light on the specific gene regulatory function of urinary exosomal miRNA.

The kidney nephron-derived exosomal miRNAs that were identified in our study may associate with kidney-specific metabolic activity, particularly renal sodium metabolism. Exosomal miRNAs that did not vary between conditions tested may serve as renal-specific controls for future longitudinal studies. Plasma-specific exosomal biomarkers may be used to exclude plasma contamination from occult glomerular diseases.

These studies are the first examination of the urinary exosomal miRNome; however, there are some caveats. The limited quantities of exosomes secreted into the lumen of the nephron required large pooled samples from relatively few subjects to be concentrated to yield enough material for array testing. Thus, these data do not explore the effect of dietary or temporal biological variation. The design and testing of smaller customized urinary exosomal miRNA arrays or RT-PCR panels should lower analytical costs and allow larger cohorts to be examined.

Conclusion

Investigating renal cellular pathophysiology through the study of kidney cell-derived extracellular biomarkers has the potential of providing a deeper understanding of how individuals express unique patterns of salt sensitivity of blood pressure. Ultimately, personalized therapeutic approaches to controlling salt-related illnesses will result from these new diagnostic techniques.

Acknowledgments

We thank Helen E. McGrath for editing and Robert E. Van Sciver for assistance with the figures.

Sources of funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NHLBI) grant HL074940.

Abbreviations

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- BP

blood pressure

- SS

salt-sensitive

- SR

salt-resistant

- ISS

inverse salt-sensitive

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Conflict of interest

This work has been submitted for patent protection by the co-inventors Gildea JJ, Carlson JM, and Felder RA.

References

- 1.Morimoto A, Uzu T, Fujii T, Nishimura M, Kuroda S, Nakamura S, et al. Sodium sensitivity and cardiovascular events in patients with essential hypertension. Lancet. 1997;350:1734–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)05189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felder RA, White MJ, Williams SM, Jose PA. Diagnostic tools for hypertension and salt sensitivity testing. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22:65–76. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835b3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carey RM, Schoeffel CD, Gildea JJ, Jones JE, McGrath HE, Gordon LN, et al. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure is associated with polymorphisms in the sodium-bicarbonate cotransporter. Hypertension. 2012;60:1359–66. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.196071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dear JW, Street JM, Bailey MA. Urinary exosomes: a reservoir for biomarker discovery and potential mediators of intra-renal signaling. Proteomics. 2012;13:1572–8. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciesla M, Skrzypek K, Kozakowska M, Loboda A, Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. MicroRNAs as biomarkers of disease onset. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;401:2051–61. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miranda KC, Bond DT, McKee M, Skog J, Păunescu TG, Da Silva N, et al. Nucleic acids within urinary exosomes/microvesicles are potential biomarkers for renal disease. Kidney Int. 2010;78:191–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khella HW, Bakhet M, Lichner Z, Romaschin AD, Jewett MA, Yousef GM. MicroRNAs in kidney disease: an emerging understanding. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;61:798–808. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gildea JJ, Lahiff DT, Van Sciver RE, Weiss RS, Shah N, McGrath HE, et al. A linear relationship between the ex-vivo sodium mediated expression of two sodium regulatory pathways as a surrogate marker of salt sensitivity of blood pressure in exfoliated human renal proximal tubule cells: the virtual renal biopsy. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;421:236–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzales PA, Zhou H, Pisitkun T, Wang NS, Star RA, Knepper MA, et al. Isolation and purification of exosomes in urine. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;641:89–99. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-711-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorenzen JM, Volkmann I, Fiedler J, Schmidt M, Scheffner I, Haller H, et al. Urinary miR-210 as a mediator of acute T-cell mediated rejection in renal allograft recipients. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2221–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang A, Zhang S, Li Z, Liang R, Ren S, Li J, et al. miR-615-3p promotes the phagocytic capacity of splenic macrophages by targeting ligand-dependent nuclear receptor corepressor in cirrhosis-related portal hypertension. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011;236:672–80. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.010349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teixeira AL, Gomes M, Medeiros R. EGFR signaling pathway and related-miRNAs in age-related diseases: the example of miR-221 and miR-222. Front Genet. 2012;3:286. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang T, Liang Y, Lin Q, Liu J, Luo F, Li X, et al. MiR-29 mediates TGFβ1-induced extracellular matrix synthesis through activation of PI3K-AKT pathway in human lung fibroblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:1336–42. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Gao L, Luo X, Wang L, Gao X, Wang W, et al. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-193a contributes to leukemogenesis in t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia by activating the PTEN/PI3K signal pathway. Blood. 2013;121:499–509. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-444729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Street JM, Birkhoff W, Menzies RI, Webb DJ, Bailey MA, Dear JW. Exosomal transmission of functional aquaporin 2 in kidney cortical collecting duct cells. J Physiol. 2011;589:6119–27. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.220277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]