Abstract

Objective

To explore maternity nurses' perceptions of women's informed decision making during labor and birth to better understand how interdisciplinary communication challenges might affect patient safety.

Design

Constructivist grounded theory.

Setting

Four hospitals in the Western United States.

Participants

Forty six (46) nurses and physicians practicing in maternity units.

Methods

Data collection strategies included individual interviews and participant observation. Data were analyzed using the constant comparative method, dimensional analysis, and situational analysis (Charmaz, 2006; Clarke, 2005; Schatzman, 1991).

Results

The nurses' central action of holding off harm encompassed three communication strategies: persuading agreement, managing information, and coaching of mothers and physicians. These strategies were executed in a complex, hierarchical context characterized by varied practice patterns and relationships. Nurses' priorities and patient safety goals were sometimes misaligned with those of physicians, resulting in potentially unsafe communication.

Conclusions

The communication strategies nurses employed resulted in intended and unintended consequences with safety implications for mothers and providers and had the potential to trap women in the middle of interprofessional conflicts and differences of opinion.

Keywords: childbirth, communication, grounded theory, maternity nursing, patient safety, United States

Communication and teamwork failures remain major contributing causes of preventable perinatal injury and death (The Joint Commission [TJC], 2004, 2011). Despite some improvements (Pettker et al., 2009), many obstetric safety challenges remain (Knox & Simpson, 2011). Nurses play a key role in reducing medical errors through prevention of communication breakdowns (Simpson, 2005), and they are well-positioned to identify communication challenges that threaten safety. One such potential challenge is information exchange during labor and birth between clinicians and mothers.

Women's decision making during labor and birth can have implications for the mother and her child. In making complex medical decisions, patients may balance relationships of mutual obligation with nurses, physicians, and their own social networks (Forsyth, Scanlan, Carter, Jordens, & Kerridge, 2011). Providers' communication practices may shape mothers' decision making, autonomy, and satisfaction with the birth experience. Providers effectively engaging patients may prevent medical errors (Hovey et al., 2011). According to a US national survey, 97% of women want to know about potential complications before agreeing to labor interventions (Declerq Sakala, Corry, & Applebaum, 2007). Most women who experienced interventions were not knowledgeable about complications, and many women were frightened or felt powerless during labor and birth (Declerq et al.) suggesting that inadequate information sharing may have emotional consequences for mothers.

CALLOUT 1

The overlooked role of patients in safety work and navigating the complexities of information exchange and risk assessment in decision making are critical areas for improvement (Fagerhaugh, Strauss, Suczek, & Wiener, 1987; Hovey et al., 2011; TJC, 2011). Team-based and patient-focused communication can support women in making informed decisions. Informed decision making requires shared responsibility for meaningful discussion between providers and patients and communication of sufficient but not overwhelming information (Braddock, Edwards, Hasenberg, Laidley, & Levinson, 1999; Cohn & Larson, 2007). However, communication regarding decision making is often executed in a limited fashion (Goldberg, 2009; Declerq et al., 2007; Levy, 1999). Although physicians or midwives obtain informed consent, maternity nurses have considerable opportunity to educate mothers (Simpson, 2005) and are positioned to identify issues that may undermine safety.

We developed a program of research exploring the nurse's role in communication and safety during labor and birth in inpatient maternity units. Nurses practicing in two academic maternity units identified the quality of information conveyed to women and breakdowns in informed decision making as safety problems (Lyndon, Africa, Lee, & Kennedy, 2010). Our purpose in this analysis was to explore maternity nurses' perspectives on how communication about women's treatment options during labor and birth may affect patient safety and to compare these nurses' perspectives with physicians' perspectives.

Theoretical Framework

Organizational Accident Theory (OAT) locates the source of medical errors in latent conditions that can be triggered by events within complex healthcare systems (Reason, 1990). In light of the unknowable nature of latent conditions, high reliability and resiliency theorists suggest that safety research should be focused on the acceptable boundaries of human adaptation to evolving conditions in dynamic environments (Rochlin, 1999; Woods & Cook, 2004). Such an approach requires analysis of individual behaviors, group norms, and interactions of individuals and groups within organizational systems (Rasmussen, 1990/2003; Woods & Cook). Individual and group behaviors such as decision making are shaped by societal constraints, social dynamics, individuals' self-concepts and perceptions in a given situation, and the interactions of individuals with each other and their environments (Blumer, 1969; Clarke, 2005). All medical care decisions ideally reflect communication strategies aimed at shared understanding and cooperative action. Symbolic interactionism, a theoretical framework in which meaning arises from social interaction, provided the structure for understanding the process of informed decision making by women during labor and birth (Blumer).

Design and Methods

Approach

We selected grounded theory for this qualitative study because we conceptualize safety as a dynamic process of collective agency (Lyndon & Kennedy, 2010). We took a constructivist approach to grounded theory in which data and interpretation are co-generated by researchers and participants (Charmaz, 2006). We examined data from two phases of research on clinicians' perspectives on maintaining safety in maternity care (Lyndon, 2008, 2010, Lyndon et al., 2010). In both phases, we asked participants how they defined safety and asked them to identify their safety concerns rather than providing definitions to them.

Data Collection

The University of California, San Francisco and participating institutions gave ethics committee approval. We collected data between September 2005 and December 2010 through individual interviews and participant observation with a purposive sample of 46 nurses and physicians. We conducted 60– 90 minute interviews that were recorded and professionally transcribed. We selected participants for their clinical experience, typical work shifts, and other characteristics (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss, 1987). We shadowed 20 participants for 107 hours of participant observation and took field notes during observations (Hammersley & Atkinson, 1995; Spradley, 1979). We obtained signed informed consent from enrolled participants and verbal consent from other staff and patients present during observations. Enrolled participants received a $15 gift card for each interview and observation.

Settings

We conducted the study in the maternity units of two urban teaching hospitals and two community hospitals in the western United States that serve childbearing women of diverse medical and social needs. Midwifery, obstetric, and maternal-fetal medical care were available in all settings; level III intensive care nurseries were available in three hospitals. We were able to recruit only two midwifery participants overall and excluded their data from this analysis to protect their confidentiality. Maternity care in the teaching settings was hospital service-based; maternity care in the community settings was private practice-based. In three hospitals, continuous in-house obstetric providers were available. Three hospitals had between 1200 and 1800 annual births; the fourth had approximately 7000 annual births.

Participants

The sample included 32 registered nurses and 14 obstetricians and maternal-fetal medicine specialists. The mean duration of maternity experience for nurses was 13 years (range 1.5 to 40) with 10 years tenure in their current positions (range 1.5 to 37). Physicians had a mean of 19 years of experience (range 1 to 45) and 15 years in their current positions (range 1 to 33). All of the nurses were women. Nine physicians were women; five were men. Self-reported ethnicity for the nurses was 75% European American, 12% Latina, and 12% Asian Pacific Islander and for the physicians was 85% European American and 15% Asian Pacific Islander. Nurses worked day, night, and evening shifts lasting either eight or 12 hours. Twelve nurses worked in teaching hospitals; 20 worked in community hospitals. Five physicians held privileges at teaching hospitals and nine at community hospitals. Physicians worked a combination of day, night, and weekend hours including time spent seeing patients and on call.

Data Analysis

We evaluated all data from two phases of research on safety in maternity care (the first focused on academic settings and the second on community settings). We simultaneously collected and analyzed data throughout each study phase using the constant comparative method and dimensional analysis (Lyndon, 2008, 2010). We read the text for units of meaning to develop open, focused, and theoretical codes to describe aspects of participants' experiences (dimensions). We used theoretical sampling (testing concepts with participants and collecting new data) to develop and differentiate properties of identified dimensions (Charmaz, 2006; Kools, McCarthy, Durham, & Robrecht, 1996). We used the dimensional analysis strategy of arranging and rearranging dimensions in a matrix to identify the central perspective and theoretical explanation for the observed relationships (Kools et al., Schatzmann, 1991). We used situational analysis mapping techniques to enhance understanding of the range of data variation and complexity (Clarke, 2005), and interpretive checks with participants to ensure validity and maintained reflexivity regarding our position as researchers and potential social influences on interviews, observations, and analysis (Angen, 2000; Kvale, 1996). Triangulation of interview and observation data, reflexive journaling, attention to representing the varied voices of participants, and member reflection further enhanced rigor (Tracy, 2010; Whittemore, Chase, & Mandle, 2001). Consideration of the quality of information women received about labor care as a safety issue was initially identified in the first phase of the study, and spontaneously raised by multiple participants thereafter. We systematically re-examined all data relating to decision making from both phases of the research to develop this analysis.

Results

Perspective: Holding Off Harm

Both nurses and physicians were concerned with keeping patients safe. Nurse participants in all settings conceptualized safety as protecting the physical, emotional, and psychological integrity of the childbearing woman. Some nurses and most physicians described safety less broadly as the prevention of physical harm or healthy mom, healthy baby. Some physicians included mothers' satisfaction with care as significant to well-being. Both nurses and physicians described patient advocacy as central to the nurse's role in protecting patients.

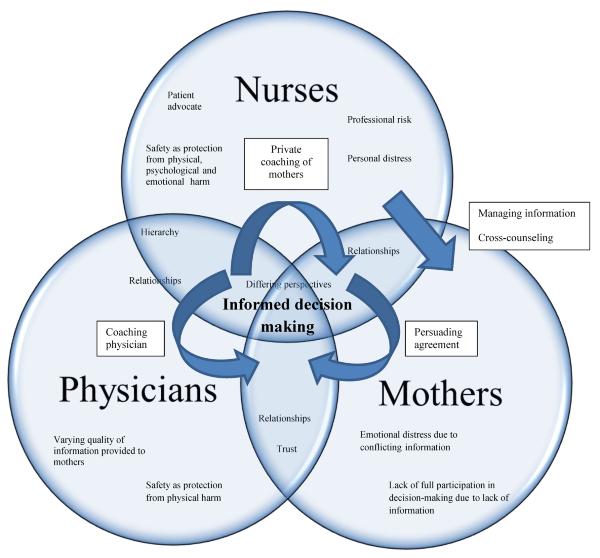

Nurses described women's involvement in care decisions as critical to safe navigation of the sometimes hostile environment of the hospital. The perspective holding off harm represents nurses' efforts to guide women safely through decision making during labor and birth (See Figure 1). Nurses engaged in holding off harm to avoid what they viewed as poorly informed, suboptimal, or potentially harmful medical decisions. They attempted to reduce conflict within the healthcare team or between the woman and her providers to avoid emotional or psychological harm to the woman. Nurses employed a range of strategies, including persuading agreement, managing information, and coaching.

Figure 1.

Holding Off Harm in Informed Decision Making: Processes, Context, Conditions and Consequences

Persuading agreement

Nurses worked to guide women toward safety by persuading them to agree with what the nurse judged to be safest. In addition to providing safe physical care, nurses aimed to protect women emotionally and psychologically when labor deviated from the anticipated course by securing the woman's support for anticipated care decisions and minimizing doubts she might have about her care. Nurses worked to maximize women's satisfaction with their birth experiences in unexpected or undesired situations:

For some women there's also that emotional harm … Let her come to accept the situation and be satisfied from here to the next 40 years or 70 years that she did everything that she could, and the baby did everything he or she could … your team did everything they could. And then you can put it to rest and go on …. So [failure to gain that acceptance] that's another kind of injury, I think.

Nurses tried to prepare women for future events to avoid surprise or conflict. Nurses and physicians also established consensus preemptively with women and families so that in the event of an emergency, women would trust providers' decisions. Similarly, some physicians reported using persuasion to facilitate agreement in care decisions. Nurses felt that by facilitating agreement they were supporting the safest plan of care. Their goal was achieving harmony among stakeholders and maintaining the woman's sense of taking an active role in her birth.

Managing Information

Many nurses thought mothers received inadequate information for decisions, perceived this lack of information as a safety threat, and took responsibility to correct information gaps. They tried to ensure women received complete information regarding the risks, benefits, and alternatives of care decisions. Nurses directly linked managing information to protecting women's safety:

Informing [women] - keeping them informed… often times physicians when they do informed consent, there's a lot that they leave out. And so I think that making sure the patient really understands things, that helps make the patient more safe.

Nurses identified potential safety threats related to poor information from other providers, mothers' support persons, and the internet. They identified physicians' communication strategies for describing procedures as often inadequate and at times problematic. In response, they gave women information that expanded on information from physicians. Nurses were felt obligated to ensure that informed consent had occurred but in most cases were not authorized to obtain the actual consent. Thus, after care decisions occurred, some nurses felt they would be overstepping the boundaries of their roles if they countered the information given by physicians or filedl in gaps to a degree that would require obtaining another consent; these nurses did not provide additional information once a decision had been made.

Nurses sometimes strategically withheld information from women for reasons of persuasion or protection. Withholding information involved awareness of the knowledge being withheld and its potential impact on the mother:

I then felt like I had to make this patient feel like she did the best thing ever, [missing her epidural,] it was the best thing. I had to end up kind of changing the rhetoric and saying, “Oh you did great. Second babies do come fast.” Knowing that she could have still gotten the epidural and gotten comfortable.

Similarly, nurses and physicians talked around women, using code language that avoided signifying a change in clinical course. For example, during an observation a nurse attending a woman in labor called the desk, asked for the charge nurse by name, and asked for a particular kind of blood sample needed for a cesarean birth and not for a routine vaginal birth. She cued the charge nurse that the fetus was in a position remote from birth (“minus two”), thereby giving a rationale for her request. The nurse's action had the effect of concealing from the mother and her support persons that the purpose of the exchange was to plan ahead for a cesarean birth. Physicians and nurses also withheld information from women with the express intent of minimizing their fear and preserving their confidence in the physician.

Coaching

Nurses described three coaching strategies for mediating communication about decisions: coaching the physician in front of the patient; private coaching of patients when the physician was not in the room; and cross-counseling of women. The purpose of these strategies was to hold off anticipated safety threats by making sure the woman had enough information to make informed decisions about her care. Coaching was a strategy for avoiding potential harm while also avoiding direct conflict with the physician.

Coaching the physician

Nurses facilitated communication between women and physicians to advocate for a woman's preferences. Nurses who used this strategy did not directly challenge the physician's decision-making authority, which most felt would be counterproductive and potentially harmful. Coaching the physician usually took place in the presence of the mother:

I said, “You know, she really kind of wanted to see if she could do this without an episiotomy.” And he said, “Oh really.” And he was kind of like stuck there now with scissors in his hand. And then he goes, “Okay.” And he puts [the scissors] down.

By repeating the mother's wishes to the physician in the mother's presence, nurses supported the mother's role in the decision-making process. Nurses used coaching primarily with specific physicians who were viewed as less likely to give women's preferences full attention.

Private coaching of mothers

Nurses also coached women privately to protect patient safety by ensuring they had the information needed to weigh risks, benefits, and alternatives of procedures. In private coaching nurses would identify concerns and coach mothers in how to elicit needed information from the physician. This kind of coaching was explicitly entwined with the nurse's personal knowledge of the physician's practice style:

I'll try to approach [an anticipated procedure] by saying, “Sometimes Dr. [Name] does things quickly and if that isn't where your thinking is going, you might want to say to her when she comes in, “Let's talk. I want to know what you're going to do to me before you do it.”

Cross-counseling

Some of the academic center nurses and most of the community hospital nurses believed giving women conflicting information could decrease women's trust in their providers, leading to distress. However, some nurses felt that their responsibility to advocate for mothers extended to providing information even when it conflicted with information given by physicians. Nurses described cross-counseling when they thought the woman's safety or autonomy was potentially threatened by a lack of accurate information. Cross-counseling involved giving information that differed from what physicians conveyed that sometimes involved stating directly that women did not or should not have to accept treatments. Cross-counseling took place when physicians were absent and gave the mother responsibility for communicating directly with the physician when s/he returned:

This has happened handfuls of times, where the physician leaves the room and the patient's ready to [take medication]; the next time the physician comes back, the patient's changed their mind! Because, I'll say to them, “I really want you to understand what it means to go on this medication” … all these really practical things that the doctors just sort of brush over in their discussion … if [the medication] is necessary, that's one thing, but they should at least be informed of what it means.

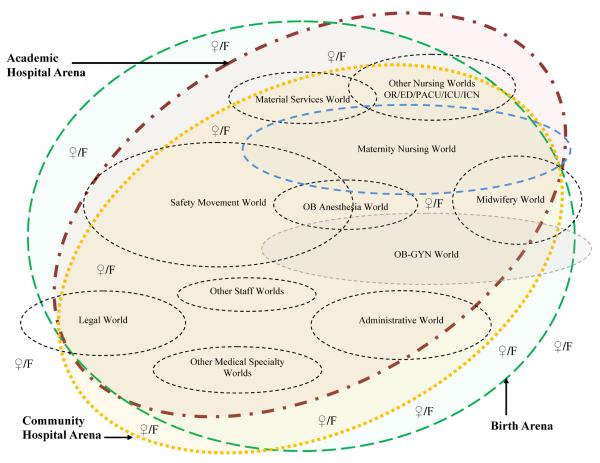

Context: The Situation in Which the Phenomenon is Embedded

Nurses cared for women in a complex social environment that reflected the influences of multiple institutions, professional associations, and world views (Figure 2). Tensions were generated by the overlap of intervention and standardization as safety strategies in the hospital arena and a holistic conceptualization of safety as attunement to women's needs in the birth arena. Nurses at the bedside tried to coordinate approaches from the differing professional worlds of obstetrics/gynecology, midwifery, pediatrics, and anesthesia while simultaneously juggling their extensive nursing and organizational responsibilities.

Figure 2.

Social worlds and arenas map. The symbol ♀/F denotes women and families positioned individually within the various arenas and sometimes trapped between social worlds (Clarke, 2005).

Hierarchy

Overt and unspoken hierarchical pressures from physicians and hospital management exerted a profound influence on nurses' communication practices. Nurses anticipated potential repercussions with colleagues or humiliation in front of patients should they choose to resist these pressures. Hierarchy included greater value placed on physicians' knowledge and tacit pressure to accommodate the non-medical needs of physicians (i.e., office or teaching schedules, sleep, recreation) for example, by attempting to achieve a more convenient time of birth. Nurses, especially in community settings, sometimes negotiated details of care without the participation or knowledge of the woman or her family:

Working with individual physicians … to accommodate [them] and avoid having a lot of pressure around the time of birth and do it safely … “Okay, your office hours finish at five, huh? Okay. I'll straight cath her at like a quarter to five.” And then, you know, maybe the head will just descend and she'll just go. You kind of work with it.

Differing perspectives

Although both nurses and physicians valued the life experience of birth, nurses were more attuned to the idea that feeling safe and empowered during birth is beneficial. Nurses expressed concern about loss of normalcy and preventing unnecessary treatments that might initiate a cascade of undesired and potentially harmful interventions. Physicians more often emphasized the ultimate goal of maternal-fetal physiological safety. Although physicians occasionally identified organizational culture and unnecessary interventions as a threat to mothers' safety, only one physician explicitly identified “normalcy” and avoiding intervention as a goal.

Physicians and a minority of nurses voiced concerns over potential threats to patient safety when women wanted what these clinicians thought was excessive or misguided control over decisions about care during birth. Physicians worried that these aspirations could potentially increase women's physiological risk by delaying or preventing needed interventions, and that physical safety was much more important than the birth experience. Some physicians stated that women sometimes need to be protected from overinvestment in the birth experience:

And then we have a little baby to keep safe. And sometimes you're keeping them safe from the obvious: hypertension or diabetes. But sometimes you're keeping them safe from that same crazy business, like, “I so much don't want a [Cesarean]-section, that I don't care if my baby's heart rate is down.” You know, the birth experience- you're keeping them safe from the birth experience.

Some physicians linked women's satisfaction with safety, but unlike nurses whether or not they thought it was important they did not identify the woman's participation in fully informed decision making as a key component of safety. In the following case, the nurse describes how physicians' and mothers' desires for a timed birth, particularly in the absence of a full discussion of the risks, benefits, and alternatives of inducing labor, can unintentionally endanger mother and fetus:

I think sometimes what keeps them not safe … is over intervention …. I mean it's not always on the physician's part too, I mean part of it is patient population driven … “I'm here to have my baby, people are in town, it's all arranged,” she's one centimeter, they break her bag, and then she's committed and she's not ready, you know, they pit her all day long, nothing, and then she ends up with a [C-]section…. that happens every day …You're toying around with pitocin all day, IUPCs, FSEs, just every single gadget. They get early epidural, it's not working, they get an epidural replaced, they end up on antibiotics for chorio. It just seems kind of like a train wreck.

Conditions Facilitating, Blocking, or Shaping Action

Variable Information Quality

A key condition shaping nurses' assessment of potential harm and their strategies for holding off harm was variation in the information provided by physicians for women's decision making. Some physicians concurred that their discussions with women regarding care decisions varied depending on a variety of factors. Nurses viewed poor information quality as a force that impaired women's ability to make informed decisions, and thereby considered information quality to be a safety problem. Nurses also objected to the language some physicians used as being difficult for women to truly understand:

I hate that word [“Help”]. “We'd like to help you” [really means] “We'd like to put two metal spoons on your baby's head and yank it out.” Like would you - can we have a real discussion about what “help” means? Can we get rid of the euphemism?

Relationships

Interpersonal relationships strongly influenced communication patterns, including communication about decision making. Both nurses and physicians emphasized the importance of sustaining trust between the woman and the physician. Nurses suggested this was important for women's satisfaction and psychological well-being during labor. Especially in community settings, nurses described intentionally being careful to relay information to women in ways that preserved the physician-woman relationship.

Consequences

Nurses' priorities for patient care and patient safety goals were sometimes misaligned with those of physicians, resulting in problematic or unsafe communication. The strategies of persuading agreement, managing information, and coaching had potentially significant intended and unintended consequences for women. Although nurses' intentions were to hold off harm by protecting women and guiding them safely, indirect communication strategies incurred the risk of trapping women between conflicting views, leaving them to struggle in isolation. For example, one situation involved an ambiguous fetal heart tracing in labor and a debate over whether to continue with oxytocin labor augmentation or proceed to cesarean birth. Rather than confront the physician with her concerns about continuing the augmentation, a nurse informed the woman of her option to decline further oxytocin. When the labor ended in harm to the baby, the patient expressed to the nurse that she blamed herself for not following the nurse's advice. Although the nurse offered the advice with the best of intentions, this example demonstrates how indirect efforts at protecting patients can backfire and result in harm.

CALLOUT 2

Paradoxically, nurses who engaged in persuading agreement protected women from distress and dissatisfaction with their care, preserved ongoing physician-patient relationships, and might indeed have created more positive birth experiences for some women. However, the strategy of tailoring information to guide women to the safest choice could often be paternalistic, decrease women's autonomy, and may not have resulted in evidence-based decisions. Moreover, the range of indirect strategies used may not have reliably enhanced safety.

Discussion

Nurses in our study viewed informed decision making as a safety process. Their efforts to support this safety process took place in a context of steep workplace hierarchy and contrasting clinical approaches and were shaped by conditions such as varying quality in information, personal relationships, and communication between team members. Nurses reported many examples of successful communication, yet their stories also illuminate unintended harmful consequences of some of the same communication strategies.

Involvement in decision making during labor increases a woman's sense of responsibility for herself and her newborn and her positive feelings toward her infant (Green, Coupland, & Kitzinger, 1990; Harrison, Kushner, Benzies, Rempel, & Kimak, 2003) whereas a traumatic birth experience can lay the foundation for recurring negative sequelae (Beck, 2011). Providers can hinder or facilitate a woman's sense of control and can humanize high-risk births even in the presence of multiple interventions (Kjaergaard, Foldgast, Dykes, 2007; Behruzi et al., 2010). Thus treatment decisions and interactions during labor and birth can influence the long-term health and quality of life of the mother, child, and family.

Some physicians articulated the importance of being in control as part of safety; at times physicians might feel that informed consent needs to take a back seat to safety in cases of unexpected emergency, such as fetal bradycardia or postpartum hemorrhage. In addition to the long-contested status of what can or should constitute informed consent (Fagerhaugh et al., 1987; Ahmed, Bryant, Tizro, & Shickle, 2012), the concept of decision making competence discourages discussion when patients are in so much pain that they cannot concentrate or have received narcotic pain medications (Graber, Ely, Clarke, Kurtz, & Weir, 1999). The complexity of decision making in light of potential conflicts between maternal and fetal interests may require too much information for a woman to absorb within the dynamic birth process, and physicians might feel that they best understood a woman's true wishes in the office prior to the onset of labor. Furthermore, physicians may have prior knowledge of the woman's concerns that the nurse is not privy to and may have established a mandate of trust based on prior interactions through which the woman extended some degree of decision making authority to the physician (Skirbekk, Middelthon, Hjortdahl, & Finset, 2011).

CALLOUT 3

Nurses frequently referenced accountability for ensuring that informed consent occurred as a professionally codified responsibility (American Nurses Association, 2010). However, nurses have neither authority nor responsibility for providing the counseling leading to consent for treatment; this falls solely to physicians or midwives. When nurses cannot communicate effectively with physicians to ensure that adequate informed consent has taken place, they must go up the chain of command, accessing administrative hierarchies and disrupting their professional worlds. Although nurses were resourceful in their patient advocacy strategies, they were often distressed by the untenable choices they faced when they thought women were poorly informed. Some strategies nurses employed to navigate these situations also placed the women they were trying to protect at risk of confusion, uncertainty, and emotional suffering.

The complexity of communications between mothers and health care team members during labor and birth increases the potential for error and safety issues. The combination of physiological, emotional, relational, and contextual factors that influence labor contribute to the challenge of communication, and nuanced and quickly-evolving situations make it more difficult to maintain the shared understanding necessary for successful teamwork. Unrecognized differences in clinical goals and divergent understandings of risks and benefits may increase safety threats when platforms for explicit sharing of interpretation are weak or absent (Lyndon et al., 2011).

In holding off harm, nurses at times create a space for mothers to add their voices and determine their own individual path within the bounds of safety. However, Dixon-Woods et al. (2006) found women sometimes made the conscious decision to give consent for surgery they did not want in order to maintain their status as “good patients,” and that covert power differentials in the process of informed consent can reinforce women's passivity. Their analysis suggested that informed consent might not only be influenced by but could also obscure key processes motivated by relationships and power inequalities.

In the case of cross-counseling, nurses' efforts to provide mothers with full information could put women at risk for emotional and psychological harm. Yet persuading agreement and other strategies nurses used to create harmony and trust between mothers and the health care team occasionally came close to using informing as a mechanism of control, where keeping the patient informed assured mothers' compliance with an anticipated plan of care, sacrificing the mother's right to full information. This strategy suggests that while nurses' stated rationale for shaping information flow to preserve women's cooperation and trust was to protect their emotional and psychological safety, at times these communication strategies might be driven by other, more paternalistic motivations.

Limitations

The perspectives presented here represent selected nurses and physicians from four unique settings and are not intended to be generalizable to all practice settings. While changes occurred in obstetric practice during the data collection period, we did not note major shifts in communication strategies or the general context of practice during participant observation. Knowledge of the outcome of clinical care affects perceptions of care processes (Dekker, 2002). Because informed decision making emerged as a safety issue in a study of clinicians, mothers and their families were not included in the study design and their perspective is absent, as are the experiences of other important maternity care personnel. Conversations were virtually always framed around autonomy and individualism and did not account for culturally diverse modes of medical decision making. The analysis is influenced by the researchers' clinical backgrounds.

Conclusion

At its best, holding off harm focuses on managing dynamic safety risks rather than guiding patients toward a single path of care and as such could be understood as a form of safeguarding (MacKinnon, 2011; Wynn, 2006). However, this exploration of safety concerns about communication during labor highlights challenges that occur when nurses are caught between advocating for mothers' rights to full information about care decisions and supporting their emotional and psychological well-being during labor and birth. The dynamics of interprofessional communication and hierarchical relationships in shaping safety remain a critical area of study, and interventions to uncover and address potential safety threats for mothers and newborns are needed. From a practice perspective, it is critical that nurses consider the potential implications of cross-counseling and work with their physician colleagues and administrators to create a work environment where direct and collegial communication oriented to the patient's interests are the overriding social norm so that engaging indirect strategies is no longer perceived necessary for meeting women's needs.

Callouts

-

1)

We sought to explore maternity nurses' perspectives on the intersection of communication about treatment options during labor and birth and patient safety.

-

2)

Nurses' communication around women's decision making was at times successful in holding off harm but could also have unintended negative consequences for patients and nurses.

-

3)

Further research is needed to address communication challenges resulting from workplace hierarchy, differing ideas of safety, and tensions between patient advocacy and emotional support.

Acknowledgement

Supported in part by the Nursing Initiative of the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation, the Association of Women's Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses, and NIH/NCRR/OD UCSF-CTSI grant KL2 RR024130. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Joanna Sullivan, CNM for assistance with data collection and analysis.

Biographies

Carrie H. Jacobson, RN, CNM, MS, is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Family Health Care Nursing, UCSF School of Nursing, San Francisco, CA.

Marya G. Zlatnik, MD, MMS, is a clinical professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, UCSF School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA.

Holly Powell Kennedy, PhD, CNM, FACNM, FAAN is the Helen Varney Professor of Midwifery, Yale University School of Nursing, New Haven, CT.

Audrey Lyndon, PhD, RNC, CNS-BC, FAAN, is an assistant professor In the Department of Family Health Care Nursing, UCSF School of Nursing, San Francisco, CA.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors reports no conflict of interest or relevant financial relationships.

References

- Ahmed S, Bryant LD, Tizro Z, Shickle D. Interpretations of informed choice in antenatal screening: A cross-cultural, Q-methodology study. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74:997–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association The nurse's role in ethics and human rights: Protecting and promoting individual worth, dignity, and human rights in practice settings. 2010 Retrieved from http://nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/EthicsStandards/Ethics-Position-Statements/-Nursess-Role-in-Ethics-and-Human-Rights.pdf.

- Angen MJ. Evaluating interpretive inquiry: Reviewing the validity debate and opening the dialogue. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10:378–395. doi: 10.1177/104973230001000308. doi: 10.1177/104973230001000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. A metaethnography of traumatic childbirth and its aftermath: Amplifying causal looping. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21:301–311. doi: 10.1177/1049732310390698. doi: 10.1177/1049732310390698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behruzi R, Hatem M, Goulet L, Fraser W, Leduc N, Misago C. Humanized birth in high risk pregnancy: Barriers and facilitating factors. Medicine Health Care and Philosophy. 2010;13(1):49–58. doi: 10.1007/s11019-009-9220-0. doi: 10.1007/s11019-009-9220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Braddock CH, 3rd, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: Time to get back to basics. JAMA. 1999;282:2313–2320. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2313. doi:10.1001/jama.282.24.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A. Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn E, Larson E. Improving participant comprehension in the informed consent process. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2007;39:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00180.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, Applebaum S. Listening to mothers II: Report of the second national U.S. survey of women's childbearing experiences. The Journal of Perinatal Education. 2007;16(4):9–14. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244769. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker S. The field guide to human error investigations. Ashgate; Burlington, VT: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M, Williams SJ, Jackson CJ, Akkad A, Kenyon S, Habiba M. Why do women consent to surgery, even when they do not want to? An interactionist and Bourdieusian analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:2742–2753. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.006. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerhaugh SY, Strauss A, Suczek B, Wiener C. Hazards in hospital care: Ensuring patient safety. Josey Bass; San Francsico, CA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth R, Scanlan C, Carter SM, Jordens CF, Kerridge I. Decision making in a crowded room: The relational significance of social roles in decisions to proceed with allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21:1260–1272. doi: 10.1177/1049732311405802. doi: 10.1177/1049732311405802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine; Chicago, IL: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg H. Informed decision making in maternity care. The Journal of Perinatal Education. 2009;18(1):32–40. doi: 10.1624/105812409X396219. doi: 10.1624/105812409X396219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber MA, Ely JW, Clarke S, Kurtz S, Weir R. Informed consent and general surgeons' attitudes toward the use of pain medication in the acute abdomen. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 1999;17:113–116. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(99)90039-6. doi: 10.1016/S0735-6757(99)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JM, Coupland VA, Kitzinger JV. Expectations, experiences, and psychological outcomes of childbirth: A prospective study of 825 women. Birth. 1990;17:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1990.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley M, Atkinson P. Ethnography: principles in practice. 2nd ed Routledge; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MJ, Kushner KE, Benzies K, Rempel G, Kimak C. Women's satisfaction with their involvement in health care decisions during a high-risk pregnancy. Birth. 2003;30:109–115. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2003.00229.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536X.2003.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey RB, Dvorak ML, Burton T, Worsham S, Padilla J, Hatlie MJ, Morck AC. Patient safety: A consumer's perspective. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21:662–672. doi: 10.1177/1049732311399779. doi: 10.1177/1049732311399779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaergaard H, Foldgast AM, Dykes AK. Experiences of non-progressive and augmented labour among nulliparous women: A qualitative interview study in a grounded theory approach. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox GE, Simpson KR. Perinatal high reliability. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011;204:373–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.10.900. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.10.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kools S, McCarthy M, Durham R, Robrecht L. Dimensional analysis: Broadening the conception of grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research. 1996;6:312–330. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale S. Interviews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Sage Publishing; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Levy V. Maintaining equilibrium: A grounded theory study of the processes involved when women make informed choices during pregnancy. Midwifery. 1999;15:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(99)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A. Social and environmental conditions creating fluctuating agency for safety in two urban academic birth centers. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2008;37:13–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00204.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A. Skilful anticipation: maternity nurses' perspectives on maintaining safety. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2010:e8. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.024547. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.024547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A, Africa D, Lee KA, Kennedy HP. Trapped in the chasm: Communication breakdowns in informed decision-making. CTS: Clinical and Translational Science. 2010;3:S22. [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A, Kennedy HP. Perinatal safety: from concept to nursing practice. Journal of Perinatatl and Neonatal Nursing. 2010;24:22–31. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e3181cb9351. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e3181cb9351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A, Sexton JB, Simpson KR, Rosenstein A, Lee KA, Wachter RM. Predictors of likelihood of speaking up about safety concerns in labour and delivery. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2011 Jul 1; doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2010-050211. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.050211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon K. Rural nurses' safeguarding work: Reembodying patient safety. Advances in Nursing Science. 2011;34:119–129. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182186b86. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182186b86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettker CM, Thung SF, Norwitz ER, Buhimschi CS, Raab CA, Copel JA, Kuczynski E, Lockwood CJ, Funai EF. Impact of a comprehensive patient safety strategy on obstetric adverse events. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009;200:492, e491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.022. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen J. The role of error in organizing behavior. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 1990/2003;12:377–383. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.5.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reason JT. Human error. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rochlin GI. Safe operation as a social construct. Ergonomics. 1999;42:1549–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzman L. Dimensional analysis: Notes on an alternative approach to the grounding of theory in qualitative research. In: Maines DR, editor. Social organization and social process: Essays in honor of Anselm Strauss. Aldine de Gruyter; New York: 1991. pp. 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson KR. Failure to rescue: Implications for evaluating quality of care during labor and birth. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 2005;19(1):24–34. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirbekk H, Middelthon AL, Hjortdahl P, Finset A. Mandates of trust in the doctor-patient relationship. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21:1182–1190. doi: 10.1177/1049732311405685. doi: 10.1177/1049732311405685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradley JP. The ethnographic interview. Holt, Rinehart and Winston; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission Preventing infant death and injury during delivery. Sentinel Event Alert. 2004;30:1–3. Retrieved from http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_30_preventing_infant_death _and_injury_during_delivery/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission Sentinel event data root causes by event type 2004-2Q 2012. 2012 http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/Root_Causes_Event_Type_20042Q2012.pdf.

- Tracy SJ. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry. 2010;16:837–851. doi: 10.1177/1077800410383121. [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2001;11:522–537. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119299. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DD, Cook RI. Mistaking error. In: Youngberg BJ, Hatlie M, editors. The patient safety handbook. Jones and Bartlett; Sudsbury, MA: 2004. pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn F. Art as measure: nursing as safeguarding. Nursing Philosophy. 2006;7(1):36–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2006.00247.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2006.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]