Abstract

There are no established treatments for recurrent meningioma when surgical and radiation options are exhausted. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is often over-expressed in meningiomas and may promote tumor growth. In open label, single arm phase II studies of the EGFR inhibitors gefitinib (NABTC 00-01) and erlotinib (NABTC 01-03) for recurrent malignant gliomas, we included exploratory subsets of recurrent meningioma patients. We have pooled the data and report the results here. Patients with recurrent histologically confirmed meningiomas with no more than 2 previous chemotherapy regimens were treated with gefitinib 500 mg/day or erlotinib 150 mg/day until tumor progression or unacceptable toxicity. Twenty-five eligible patients were enrolled with median age 57 years (range 29–81) and median Karnofsky performance status (KPS) score 90 (range 60–100). Sixteen patients (64%) received gefitinib and 9 (36%) erlotinib. Eight patients (32%) had benign tumors, 9 (36%) atypical, and 8 (32%) malignant. For benign tumors, the 6-month progression-free survival (PFS6) was 25%, 12-month PFS (PFS12) 13%, 6-month overall survival (OS6) 63%, and 12-month OS (OS12) 50%. For atypical and malignant tumors, PFS6 was 29%, PFS12 18%, OS6 71%, and OS12 65%. The PFS and OS were not significantly different by histology. There were no objective imaging responses, but 8 patients (32%) maintained stable disease. Although treatment was well-tolerated, neither gefitinib nor erlotinib appear to have significant activity against recurrent meningioma. The role of EGFR inhibitors in meningiomas is unclear. Evaluation of multi-targeted inhibitors and EGFR inhibitors in combination with other targeted molecular agents may be warranted.

Keywords: meningioma, erlotinib, gefitinib, epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor

Introduction

Meningiomas are the most common type of primary brain tumor in adults [1]. Gross total resection offers the best chance of cure. Unfortunately, this cannot be achieved safely in many patients. In patients whose tumors are incompletely resected, recurrence is common, approaching 70% with 10–15 years of follow-up; in the case of atypical (WHO grade II) and malignant meningiomas (WHO grade III), the time to recurrence is shorter and long-term survival rates are low.

The WHO classification for meningiomas is based on the degree of anaplasia, number of mitoses, and presence of necrosis [2]. Histological grading is important because it helps to predict the likelihood of recurrence. Benign meningiomas (WHO grade I) account for over 90% of tumors and have a recurrence risk of 7–20% after gross total resection [2–4]. Atypical meningiomas account for 5–7% of meningiomas and are associated with a 40% recurrence rate despite resection [4]. Malignant meningiomas represent 1–3% of meningiomas but recur in 50–80% of patients and usually result in death within 2 years of diagnosis [2, 3].

Recurrent meningiomas are typically treated with re-operation or, more often, with external beam irradiation or stereotactic radiosurgery, if previously unirradiated [5]. These interventions are usually effective in preventing or delaying a second recurrence, especially in benign meningioma. Patients with atypical and malignant meningiomas obtain less benefit from these treatments and are more likely to relapse [6]. Patients with recurrent meningioma who have exhausted surgical and radiotherapy options have limited therapeutic choices. Despite interest in treating such patients with cytotoxic chemotherapy and targeted molecular agents, no effective drug therapy has emerged [5, 7].

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is over-expressed in more than 60% of meningiomas [8–14]. Many human meningioma specimens have activated EGFRs that signal through the Ras/mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase pathways [9], and receptor activation by epidermal growth factor (EGF) or transforming growth factor-α (TGFα) promotes proliferation of meningioma cells in vitro [10, 14, 15]. Most meningiomas express both EGF and TGFα mRNA [9]. Increased TGFα immunoreactivity in meningioma cells and tumor specimens has been associated with aggressive growth [12, 15, 16]. These findings suggest that EGFR activation by autocrine or paracrine mechanisms in human meningioma may promote tumor growth.

Gefitinib (ZD1839, Iressa®, AstraZeneca, London, United Kingdom) and erlotinib (OSI-774, Tarceva®, Genentech, South San Francisco, California and OSI Pharmaceuticals, Melville, New York) are small molecule EGFR inhibitors that were first evaluated in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Gefitinib is now in limited use in the United States after a follow-up trial failed to demonstrate a survival benefit [17], while erlotinib is FDA-approved for NSCLC and pancreatic cancer. Given limited options for patients with recurrent meningioma, they were included as a pilot component in phase II studies of gefitinib and erlotinib for malignant glioma patients organized by the North American Brain Tumor Consortium (NABTC). Because gefitinib is metabolized in the liver by cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 3A4 (CYP 3A4), gefitinib dose escalation was required for patients taking CYP enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (EIAED). Erlotinib is metabolized primarily in the liver by CYP 3A4 (70%) and CYP 1A2 (30%). Patients taking EIAEDs were not eligible for the erlotinib trial.

Materials and Methods

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to determine the efficacy of gefitinib or erlotinib in patients with recurrent meningioma treated on the two NABTC trials. Six-month progression-free survival (PFS6) was the primary endpoint, and overall survival (OS) was the secondary endpoint. We also evaluated the safety of these regimens and assessed radiographic response rates.

Patient Eligibility

Patients were enrolled between March 2002 and June 2005. Both protocols were approved by the local institutional review boards, and each patient was required to sign an informed consent form prior to enrollment. Patients had to be ≥ 18 years old, with a life expectancy > 8 weeks and a Karnofsky performance status of ≥ 60. All patients were required to have a histologically confirmed meningioma of any grade. Tumor specimens were reviewed centrally to confirm the diagnosis, but tumor tissue was not obtained for additional analyses. Patients who underwent resection at recurrence were eligible after they recovered from surgery; evaluable or measurable disease was not mandated. All patients were required to have pretreatment brain CT or MRI within 14 days of starting therapy and on a stable steroid dose for ≥ 5 days.

Patients treated with gefitinib were required to have had radiation treatment, while patients treated with erlotinib were eligible whether they had received radiation or not. The requirement for prior radiation therapy was removed for patients treated with erlotinib in an attempt to improve accrual. All patients who received radiotherapy had to have completed treatment at least 4 weeks prior to starting protocol therapy. Patients with disease progression within 12 weeks of completing radiation therapy or who were treated with interstitial brachytherapy or stereotactic radiosurgery were required to have confirmation of progressive disease based on brain imaging or histopathology. Patients were excluded if they had >2 prior treatments with chemotherapy or biologic agents. They had to have recovered from the toxic effects of any previous therapies. All patients were required to have adequate bone marrow function (white blood cells > 3,000/μl, absolute neutrophil count > 1,500/mm3, platelets > 100,000/mm3, and hemoglobin > 10 mg/dl), liver function (SGOT and bilirubin < 1.5 times the upper limit of normal), and renal function (creatinine < 1.5 mg/dL) within 14 days prior to registration. Only patients treated with gefitinib were permitted to take EIAEDs. Erlotinib patients who switched from an EIAED to a non-EIAED required a 14-day wash-out period. Patients with abnormalities of the cornea were ineligible. Patients could not have any significant medical illnesses that would compromise their ability to tolerate protocol therapy. Patients with a history of any other cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer or carcinoma in situ of the cervix), unless in complete remission and off all therapy for that disease for ≥ 3 years, were ineligible. Women of child-bearing potential and men agreed to use adequate contraception for the duration of study participation and for 12 weeks after study completion. Women who were pregnant or nursing were excluded.

Treatment Regimen

Gefitinib was supplied as 250 mg tablets by the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis (DCTD), Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, under a clinical trials agreement with AstraZeneca. Gefitinib tablets were taken with an 8 ounce glass of water. The starting dose was 500 mg/day on a continuous daily basis. Patients receiving dexamethasone, other corticosteroids, or EIAEDs were required to escalate the dose to 750 mg/day after 2 weeks of therapy if no significant toxicity developed. A second dose escalation to 1000 mg/day was required after 2 more weeks if no significant toxicity developed.

Erlotinib was supplied as 25 mg, 100 mg, or 150 mg tablets by the DCTD under a clinical trials agreement with OSI Pharmaceuticals. The tablets were taken with an 8 ounce glass of water, one hour before or two hours after food, in the morning. All patients received 150 mg/day on a continuous daily basis.

Patients were treated in 4 week cycles. Treatment continued indefinitely, with clinical and radiographic evaluations approximately every other cycle, as long as there were no unacceptable toxicities or tumor progression.

Dose Modification and Patient Follow-up

Patients were monitored closely throughout therapy for drug-related toxicity, and all adverse events were recorded and graded according to the NCI CTC version 2.0. A complete blood count with differential was obtained every 2 weeks during treatment and a comprehensive metabolic panel every 4 weeks. Patients on warfarin had a prothrombin time checked every 1–2 weeks. Physical and neurologic examinations were performed every 4 weeks and brain imaging every 8 weeks. Radiographic responses were evaluated at the individual institutions and confirmed centrally.

Treatment was held in patients who developed corneal erosions and was not restarted until the erosion had resolved completely. Patients with grade 2 rash or diarrhea that was unacceptable to them were permitted to hold treatment and then resume after a dose reduction when the toxicity resolved to < grade 1. Patients who developed grade 3 or 4 toxicity were required to hold treatment until toxicity resolved to < grade 1; treatment then resumed after a dose reduction. If grade 2 or higher toxicity persisted after the study drug was held for 2 weeks or more, patients were required to come off study treatment unless the patient and investigator agreed that the risk of further treatment was justified. Patients were required to come off study treatment if a second dose reduction was required, unless the investigator and the subject agreed that the risk of further treatment was justified.

Imaging and Response Assessment

MRI or CT of the brain was performed every 8 weeks. Axial and coronal T1 pre- and post-gadolinium images, among others, were obtained and used for this study. Responses were determined using modified Macdonald criteria [18]: complete response—complete disappearance of enhancing tumor; partial response—at least 50% decrease in the sum of products of the two largest perpendicular diameters of all measurable lesions; progressive disease—at least 25% increase in the sum of products of the two largest perpendicular diameters of all measurable lesions; stable disease—neither complete response, partial response, nor progressive disease. The criteria were applied when patients were on a stable dose of corticosteroids and did not experience clinical deterioration other than that attributable to progressive tumor burden (e.g., systemic or metabolic disturbances). Responses (complete or partial) had to be sustained on two successive scans taken at least 4 weeks apart compared with the baseline scan.

Statistical Methods

The primary objective of both studies was to determine whether the study drug prolongs PFS6 for patients with recurrent malignant gliomas compared to historical controls. Sample size and power calculations, therefore, did not account for the subset of patients with meningiomas. A relatively small number of meningioma patients were included in each study to provide preliminary information about the potential efficacy and safety of the study drug in this population.

Given limited accrual to the exploratory meningioma arm in each trial, patients treated with either gefitinib or erlotinib were pooled for purposes of this analysis. PFS6 and response rate were determined based on the proportion of patients known to have reached that endpoint. Median PFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Time was measured from the registration date. Data were stratified by histologic grade with benign meningioma patients in one group and atypical or malignant meningioma patients in the other group. Patients who were not eligible or who received no treatment were excluded from the efficacy analysis. All patients who received therapy were included in the evaluation of safety. Comparisons of PFS and OS between patient groups were based on the log-rank test.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Twenty-eight patients were enrolled. Three patients proved ineligible because of the inability to confirm the diagnosis on central pathology review (n=1), more than 2 previous recurrences (n=1), and the patient’s decision to have surgery shortly after starting protocol therapy (n=1). Characteristics of the 25 eligible patients are summarized in Table 1. Median age was 57 years with a range of 29–81 years. There were 12 men and 13 women. Median Karnofsky performance status (KPS) score was 90 with a range of 60–100. Meningioma histologic grades were evenly divided, with 8 benign, 9 atypical, and 8 with malignant meningiomas. The median number of previous chemotherapy regimens was 0, but 8 patients had received 1 previous regimen, and 1 patient had received 2. All but 4 patients had received radiation therapy. Sixteen patients (64%) were treated with gefitinib and 9 (36%) with erlotinib. None of the gefitinib patients received corticosteroids. Three gefitinib patients were taking EIAEDs and therefore escalated their gefitinib doses to 1000 mg/day. The other gefitinib patients received 500 mg/day. Two of the erlotinib patients received corticosteroids during protocol therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 25 eligible patients

| Patient Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age, years | 57 |

| Age range, years | 29–81 |

| Male:female ratio | 12:13 |

| Median KPS score | 90 |

| KPS range | 60–100 |

| Meningioma grade | |

| Benign | 8 (32) |

| Atypical | 9 (36) |

| Malignant | 8 (32) |

| Median number of previous chemotherapy regimens | 0 |

| Range of previous chemotherapy regimens | 0–2 |

| Previous radiation therapy | 21 (84) |

| Protocol treatment | |

| Erlotinib | 9 (36) |

| Gefitinib | 16 (64) |

Response and Survival

The 25 eligible patients came off study due to progressive disease (n=19), death of unknown cause (n=1), toxicity (n=4), or protocol violation (n=1). There were no radiographic responses. Eight patients (32%) had stable disease as their best response.

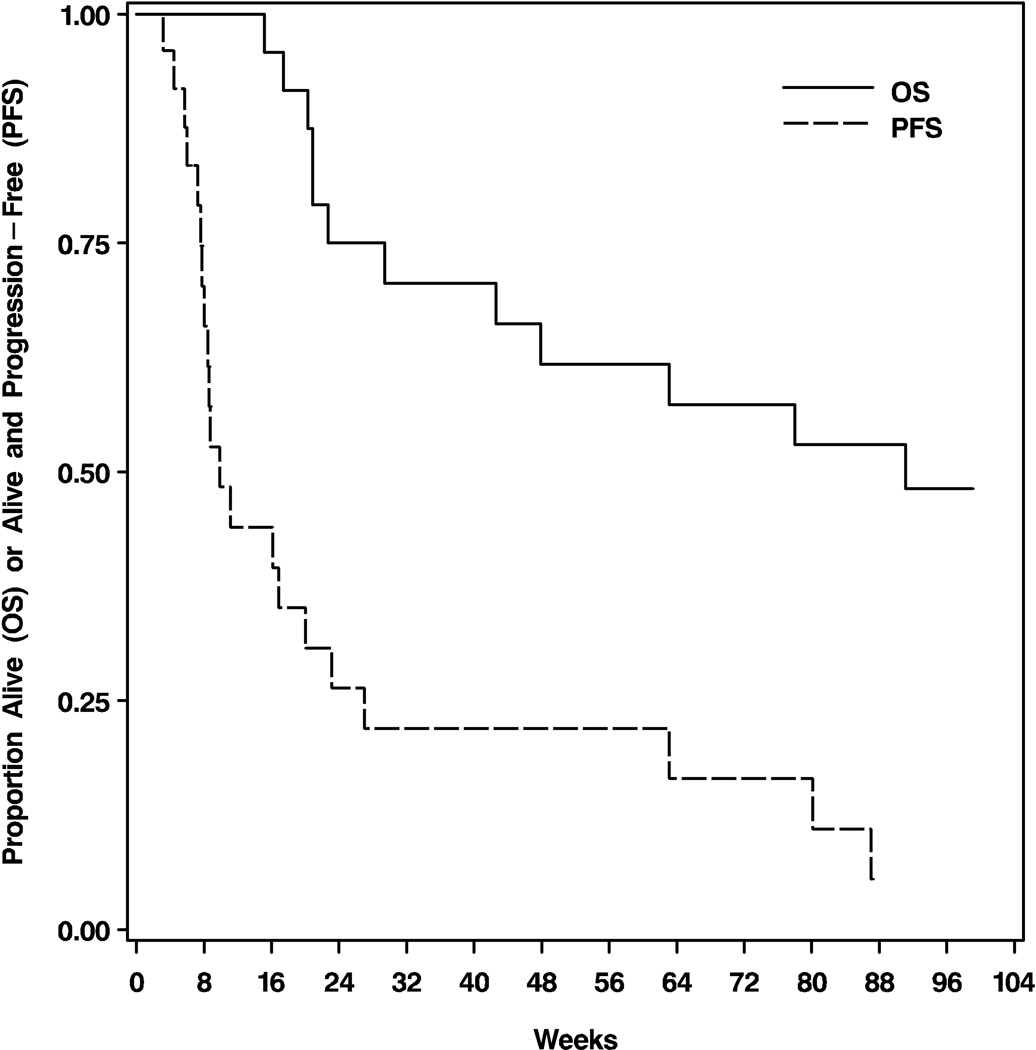

At the time of analysis, 14 (56%) patients had died. From study enrollment, the median PFS was 10 weeks (95% confidence interval [CI]: 8–20), PFS6 28%, and 12-month PFS (PFS12) 16% (Figure 1). The median OS was 23 months (95% CI: 11-not yet reached), 6-month OS (OS6) 76%, and 12-month OS (OS12) 60% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing progression-free and overall survival for the 25 eligible patients.

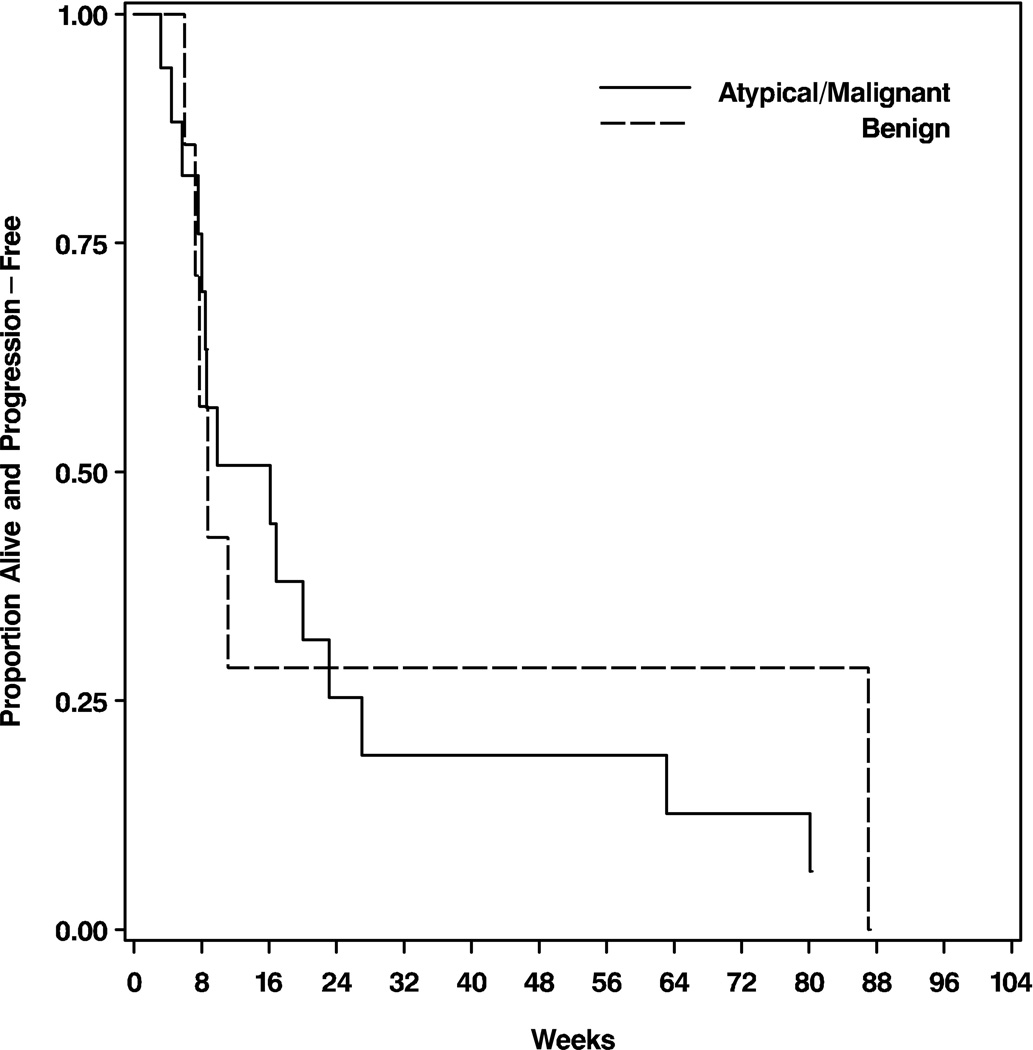

There was no PFS difference between the benign meningioma patients and the patients with atypical or malignant meningiomas (Figure 2a; p=0.93). Patients with benign meningiomas had a median PFS of 9 weeks (95% CI: 7–87), PFS6 of 25%, and PFS12 of 13%; patients with atypical or malignant meningiomas had a median PFS of 16 weeks (95% CI: 8–23), PFS6 of 29%, and PFS12 of 18%. There was also no OS difference between the two groups (Figure 2b; p=0.43). Patient with benign meningiomas had a median OS of 13 months (95% CI: 5-not yet reached), OS6 of 63%, and OS12 of 50%; patients with atypical or malignant meningiomas had a median OS of 33 months (95% CI: 12-not yet reached), OS6 of 71%, and OS12 of 65%.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing progression-free (A) and overall survival (B) for the 25 eligible patients stratified by histologic grade. The differences are not statistically significant.

Progression-free survival and OS were also compared between the two trials. There was no PFS difference (p=0.80). Patients treated with gefitinib had a median PFS of 16 weeks (95% CI: 7–23) and a PFS6 of 25%, while patients treated with erlotinib had a median PFS of 9 weeks (95% CI: 8–27) and a PFS6 of 33%. The OS difference was statistically significant (p=0.01). Patients treated with gefitinib had a median OS that was not yet reached; 1-year OS was 75%, and 2-year OS was 50%. Patients treated with erlotinib had a median OS of 9 months (95% CI: 5–33); 1-year OS was 44%, and 2-year OS was 22%.

Toxicity

Patients treated with gefitinib received a median of 2 cycles (range 1–26), while patients treated with erlotinib received a median of 6 cycles (range 1–55). Toxicity was monitored and graded based on the NCI CTC version 2.0 throughout both trials. In both cases, grades 1 and 2 rash and diarrhea were the most common toxicities reported. There were no treatment-related deaths. Of the 4 patients who stopped treatment for toxicity, 1 on each protocol had grade 3 rash, and 1 on erlotinib had grade 3 abdominal pain thought due to infection. One gefitinib patient had grade 1 rash and grade 2 edema that were intolerable to the patient. Grade 3 treatment-related toxicities are listed in Table 2. There were no treatment-related grade 4 or 5 toxicities. There were 19 grade 3 toxicities in 6 gefitinib patients and 3 grade 3 toxicities (1 dehydration and 2 rash) in 3 erlotinib patients. Thirteen patients had grade 2 or higher rash within the first 6 weeks of therapy. Rash was not predictive of PFS or OS from this timepoint.

Table 2.

Grade 3 adverse events at least possibly related to treatment

| Adverse Event | No. |

|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 1 |

| Dehydration | 1 |

| Diarrhea | 2 |

| Fatigue | 1 |

| Hyperammonemia | 1 |

| Hypokalemia | 1 |

| Hyponatremia | 1 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 1 |

| Infection | 1 |

| Lymphocytopenia | 3 |

| Rash | 6 |

| SGPT elevation | 1 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 |

| Weight loss | 1 |

Discussion

Meningioma patients whose tumors progress following surgery and radiation therapy have few remaining treatment options. Because of pre-clinical data suggesting that EGFR may drive tumor cell growth and proliferation, we included exploratory subsets of recurrent meningioma patients in phase II clinical trials of gefitinib and erlotinib for recurrent malignant glioma.

Six-month progression-free survival for patients with recurrent atypical and malignant meningiomas is nearly zero in reported studies [6, 19]. There are limited historical data concerning the rate of tumor progression in patients with recurrent benign meningiomas. In a phase II study of imatinib mesylate for recurrent meningiomas, approximately 40% of patients with benign meningiomas achieved PFS6 [20]. In the phase II studies reported here, atypical and malignant meningioma patients had a PFS6 of 29% and benign meningioma patients 25%. The number of patients in our exploratory cohorts is too small to draw statistically robust conclusions. However, the relatively low PFS6 and lack of radiographic responses suggest that gefitinib and erlotinib have minimal activity in recurrent meningioma.

In prospective phase II studies in recurrent malignant glioma patients, neither gefitinib [21, 22] nor erlotinib [23, 24] has been shown to have activity. One potential explanation for failure of these EGFR inhibitors in malignant glioma is insufficient penetration of the blood-brain barrier. Since no such barrier exists for meningiomas, one must conclude that these agents alone, like several other chemotherapeutics that have been evaluated [20, 25–28], are inactive.

The chief limitation of this study is the small number of patients enrolled as a result of poor accrual. The two protocols reported here were powered to identify a therapeutic effect in recurrent malignant glioma rather than meningioma. The relatively small number of patients treated likely explains why there were no significant survival differences between patients with benign compared to atypical and malignant meningiomas, although since resampling tumor was not mandatory, some of the lower grade tumors may have transformed at the time of recurrence. Interestingly, there was a statistically significant OS difference that favored patients treated with gefitinib. Since there was no significant PFS difference between the gefitinib and erlotinib groups, the most likely explanation is a difference in the patient populations which cannot be detected based on the small number of cases.

The relative inactivity of gefitinib and erlotinib against recurrent meningioma suggests that EGFR alone may not be a valuable therapeutic target in this disease. However, drugs that inhibit EGFR together with other relevant receptor tyrosine kinases may have a role in meningioma therapy. Examples include the EGFR/Her2 inhibitor lapatinib and the EGFR/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFR) inhibitor vandetanib (ZD6474, Zactima™, AstraZeneca, London, United Kingdom). Additionally, combinations of EGFR inhibitors with other targeted molecular agents may prove more effective. Testing these approaches in meningiomas may be worthwhile, especially if combined with correlative studies examining intratumoral drug levels and target inhibition in vivo.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: 5-U01CA62399-09 (J.J. Raizer, L.E. Abrey, A.B. Lassman and L.M. DeAngelis), NABTC # CA62399 and Member # CA62422, GCRC Grant # M01-RR00079 (S.M. Chang, K.R. Lamborn and M.D. Prados); CA62412, GCRC Grant # CA16672 (W.K.A. Yung and M.R. Gilbert); U01CA62407-08 (P.Y. Wen), U01CA62421–08, GCRC Grant # M01 RR03186 (M. Mehta and I.H. Robins); U01CA62405, GCRC Grant # M01-RR00056 (F. Lieberman); U01 CA62399, GCRC Grant # M01-RR0865 (T.F. Cloughesy).

References

- 1.CBTRUS. Statistical Report: Primary Brain Tumors in the United States, 2000–2004. Published by the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DN, Scheithauer BW, Budka H. Meningeal tumors. In: Kleihues P, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO Classification of Tumors Tumors of the Nervous System. Lyon: IARC; pp. 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamszus K. Meningioma pathology, genetics, and biology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:275–286. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.4.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perry A, Gutmann DH, Reifenberger G. Molecular pathogenesis of meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2004;70:183–202. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-2749-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMullen KP, Stieber VW. Meningioma: current treatment options and future directions. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2004;5:499–509. doi: 10.1007/s11864-004-0038-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Modha A, Gutin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: a review. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:538–550. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000170980.47582.a5. discussion 538–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norden AD, Drappatz J, Wen PY. Targeted drug therapy for meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E12. doi: 10.3171/FOC-07/10/E12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson U, Guo D, Malmer B, Bergenheim AT, Brannstrom T, Hedman H, Henriksson R. Epidermal growth factor receptor family (EGFR, ErbB2-4) in gliomas and meningiomas. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2004;108:135–142. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0875-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll RS, Black PM, Zhang J, Kirsch M, Percec I, Lau N, Guha A. Expression and activation of epidermal growth factor receptors in meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:315–323. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.2.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson MD, Horiba M, Winnier AR, Arteaga CL. The epidermal growth factor receptor is associated with phospholipase C-gamma 1 in meningiomas. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:146–153. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(94)90270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones NR, Rossi ML, Gregoriou M, Hughes JT. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression in 72 meningiomas. Cancer. 1990;66:152–155. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900701)66:1<152::aid-cncr2820660127>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linggood RM, Hsu DW, Efird JT, Pardo FS. TGF alpha expression in meningioma--tumor progression and therapeutic response. J Neurooncol. 1995;26:45–51. doi: 10.1007/BF01054768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanfilippo JS, Rao CV, Guarnaschelli JJ, Woost PG, Byrd VM, Jones E, Schultz GS. Detection of epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor alpha protein in meningiomas and other tumors of the central nervous system in human beings. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:488–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisman AS, Raguet SS, Kelly PA. Characterization of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human meningioma. Cancer Res. 1987;47:2172–2176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson M, Toms S. Mitogenic signal transduction pathways in meningiomas: novel targets for meningioma chemotherapy? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:1029–1036. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000189834.63951.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu DW, Efird JT, Hedley-Whyte ET. MIB-1 (Ki-67) index and transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF alpha) immunoreactivity are significant prognostic predictors for meningiomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1998;24:441–452. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1998.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, von Pawel J, Thongprasert S, Tan EH, Pemberton K, Archer V, Carroll K. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macdonald DR, Cascino TL, Schold SC, Jr, Cairncross JG. Response criteria for phase II studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1277–1280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen PY, Yung WKA, Lamborn KR, Norden AD, Cloughesy TF, Abrey LE, Fine HA, Chang SM, Robins HI, Fink K, DeAngelis LM, Mehta M, Di Tomaso E, Drappatz J, Kesari S, Ligon KL, Aldape K, Jain RK, Stiles CD, Egorin MJ, Prados MD. Phase II Study of Imatinib Mesylate (Gleevec®) For Recurrent Meningiomas (North American Brain Tumor Consortium Study 01-08) Neuro Oncol. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2009-010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen PY, Yung WKA, Lamborn K, et al. Phase II Study of Imatinib Mesylate (STI571) For Patients With Recurrent Meningiomas (NABTC 01-08) Neuro Oncol. 2006;8:454. [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franceschi E, Cavallo G, Lonardi S, Magrini E, Tosoni A, Grosso D, Scopece L, Blatt V, Urbini B, Pession A, Tallini G, Crino L, Brandes AA. Gefitinib in patients with progressive high-grade gliomas: a multicentre phase II study by Gruppo Italiano Cooperativo di Neuro-Oncologia (GICNO) Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1047–1051. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich JN, Reardon DA, Peery T, Dowell JM, Quinn JA, Penne KL, Wikstrand CJ, Van Duyn LB, Dancey JE, McLendon RE, Kao JC, Stenzel TT, Ahmed Rasheed BK, Tourt-Uhlig SE, Herndon JE, 2nd, Vredenburgh JJ, Sampson JH, Friedman AH, Bigner DD, Friedman HS. Phase II trial of gefitinib in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:133–142. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raizer JJ, Abrey LE, Wen P, Cloughesy T, Robins IA, Fine HA, Lieberman F, Puduvalli VK, Fink KL, Prados M. A phase II trial of erlotinib (OSI-774) in patients (pts) with recurrent malignant gliomas (MG) not on EIAEDs. Proc ASCO. 2004;22:1502. [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Den Bent MJ, Brandes A, Rampling R, Kouwenhoven M, Kros JM, Carpentier AF, Clement P, Klughammer B, Gorlia T, Lacombe D. Randomized phase II trial of erlotinib (E) versus temozolomide (TMZ) or BCNU in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme (GBM): EORTC 26034. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5984. [abstract] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chamberlain MC, Tsao-Wei DD, Groshen S. Temozolomide for treatment-resistant recurrent meningioma. Neurology. 2004;62:1210–1212. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118300.82017.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chamberlain MC, Tsao-Wei DD, Groshen S. Salvage chemotherapy with CPT-11 for recurrent meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2006;78:271–276. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-9093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grunberg SM, Rankin C, Townsend J, Ahmadi J, Feun L, Fredericks R, Russell C, Kabbinavar F, Barger GR, Stelzer KJ. Phase III Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study of Mifepristone (RU) for the Treatment of Unresectable Meningioma. Proc ASCO. 2001;20:222. [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton HB, Scott SR, Volpi C. Hydroxyurea chemotherapy for meningiomas: enlarged cohort with extended follow-up. Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18:495–499. doi: 10.1080/02688690400012392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]