Abstract

Pituitary gonadotrophs are a small fraction of the anterior pituitary population, yet they synthesize gonadotropins: luteinizing (LH) and follicle-stimulating (FSH), essential for gametogenesis and steroidogenesis. LH is secreted via a regulated pathway while FSH release is mostly constitutive and controlled by synthesis. Although gonadotrophs fire action potentials spontaneously, the intracellular Ca2+ rises produced do not influence secretion, which is mainly driven by Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), a decapeptide synthesized in the hypothalamus and released in a pulsatile manner into the hypophyseal portal circulation. GnRH binding to G-protein-coupled receptors triggers Ca2+ mobilization from InsP3-sensitive intracellular pools, generating the global Ca2+ elevations necessary for secretion. Ca2+ signaling responses to increasing (GnRH) vary in stereotyped fashion from subthreshold to baseline spiking (oscillatory), to biphasic (spike-oscillatory or spike-plateau). This progression varies somewhat in gonadotrophs from different species and biological preparations. Both baseline spiking and biphasic GnRH-induced Ca2+ signals control LH/FSH synthesis and exocytosis. Estradiol and testosterone regulate gonadotropin secretion through feedback mechanisms, while FSH synthesis and release are influenced by activin, inhibin, and follistatin. Adaptation to physiological events like the estrous cycle, involves changes in GnRH sensitivity and LH/FSH synthesis: in proestrus, estradiol feedback regulation abruptly changes from negative to positive, causing the pre-ovulatory LH surge. Similarly, when testosterone levels drop after orquiectomy the lack of negative feedback on pituitary and hypothalamus boosts both GnRH and LH secretion, gonadotrophs GnRH sensitivity increases, and Ca2+ signaling patterns change. In addition, gonadotrophs proliferate and grow. These plastic changes denote a more vigorous functional adaptation in response to an extraordinary functional demand.

Keywords: pituitary, gonadotrophs, calcium, gonadotropins, GnRH, secretion

Gonadotrophs Function and Characteristics

The reproductive function and sexual maturation is under the control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Pituitary gonadotrophs, which constitute 7–15% of the anterior pituitary gland secrete two dimeric glycoproteins, gonadotropins, luteinizing (LH) and follicle-stimulating (FSH) hormones that play an essential role in the control of steroidogenesis, gametogenesis, and ovulation (1). The regulation of their synthesis and secretion are under control of hypothalamic stimulation (gonadotropin-releasing hormone; GnRH), gonadal sex steroids (estradiol, progesterone, testosterone) and peptides (inhibins), and paracrine factors (inhibins, activins, and follistatin). The pituitary gland must adapt to different physiological changes from prepubertal to mature sexual life, therefore gonadotrophs plasticity and gonadotropins secretion are essential to produce the changes needed in different situations, for example the rapid daily hormonal variations along the reproductive female cycle. Integration of the different regulatory signals by the gonadotrophs results in the coordinated control of synthesis, packaging, and differential secretion of gonadotropins to accurately respond and control sexual maturation and normal reproductive function.

Immunocytochemical studies have demonstrated the presence of bihormonal (70%) and monohormonal (15%) gonadotrophs whose percentage shifts under different physiological conditions, such as castration or estrous cycle (2). LH and FSH have a common alpha (α) and distinct beta (β) subunit. After its synthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and its passage trough the Golgi apparatus, hormones are delivered to the plasma membrane trough a constitutively or regulated secretory pathway; in the latter, fusion of secretory vesicles to the plasma membrane is arrested waiting for specific signals to be secreted. Gonadotropin synthesis and secretion diverges under a range of physiological and experimental conditions (3), indicating that GnRH and other regulators of gonadotropins selectively activate this pathways.

Exocytosis in excitable cells is a process highly dependent of intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) rise, gonadotrophs as other pituitary endocrine cells display spontaneous intracellular Ca2+ transients in dependence of changes in the membrane electrical activity. However, this membrane potential oscillations are small and do not produce the necessary [Ca2+]i increase to generate hormonal secretion (4, 5), as a result, basal secretion is low and not affected by extracellular Ca2+ (4, 6). In both cases, the principal regulation is done by GnRH, a decapeptide that is synthesized in the hypothalamus, stored in axon terminals in the median eminence, and released in a pulsatile manner into the hypophyseal portal circulation (7). Numerous studies have shown that isolated gonadotrophs in primary culture (and more recently, also gonadotrophs in situ) present robust and stereotyped dose-dependent intracellular Ca2+ signals in response to suprathreshold concentrations of GnRH (8–11), the rise produced in cytosolic [Ca2+] triggers gonadotropins exocytosis and synthesis.

Understanding the origin and meaning of these intracellular Ca2+ signals are essential to the knowledge of the physiology of normal reproduction, as well as reproductive function disorders. This review outlines different regulators of the gonadotrophs biology with special regard in the recent progress on GnRH-induced Ca2+ signaling and secretion in pituitary gonadotrophs, both at the cellular and tissue level.

Ca2+ Signals Induced by GnRH and Other Secretagogues

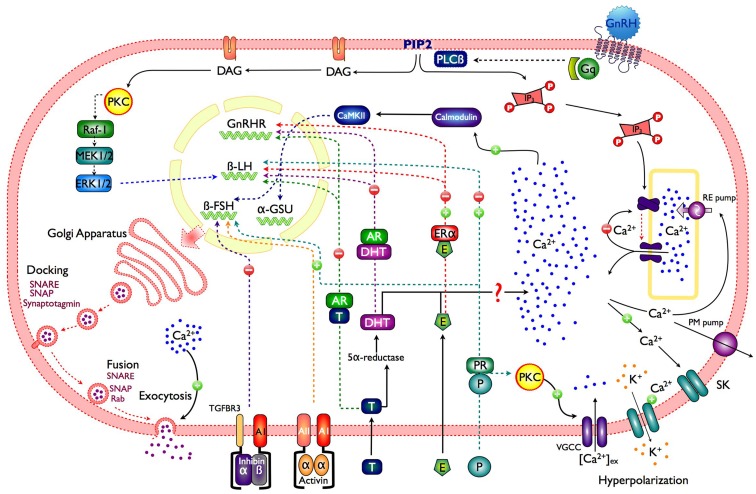

In order to mediate multiple effects such as secretion, synthesis, and phenotype maintenance, the GnRH variants in different species interact with their receptor (GnRHR), which is a member of the rhodopsin-like G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) superfamily (12). Upon GnRH binding to the GnRHRs in the gonadotroph membrane, the α subunit of the Gq/11 protein dissociates and activates phospholipase C (PLC-β), resulting in the rapid hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-biphosphate (PIP2) and the production of two second messengers: diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3); long lasting GnRH stimulation (∼5–10 min) could also activate phospholipase D (PLD) and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (12). InsP3 generates Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular pools, and DAG triggers protein kinase C (PKC) activation which in turn reduces depolarization-mediated Ca2+ influx, while increasing gonadotropin secretion (13) (Figure 1). PKC sensitizes the secretory machinery to Ca2+ (14), which explain why GnRH application is more effective to induce secretion than membrane depolarization or caged Ca2+ photolysis (5). PKC activation is also involved in other exocytosis-associated processes, like GnRH self-priming and cytoskeletal rearrangement (3).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of a gonadotroph illustrating the main control pathways of gonadotropin synthesis and secretion. GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; Gq, protein Gq/11; PLCβ, phospholipase C; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; PKC, protein kinase C; VGCC, voltage-gated calcium channels; CaMKII, calcium calmodulin type II kinase; RE pump, endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump; PM pump, plasma membrane Ca2+ pump; SK, small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels; P, progesterone; PR, progesterone receptor; E, estradiol; ERα, estrogen receptor α; T, testosterone; AR, androgen receptor; Raf, serine/threonine kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinases.

In the lumen of the ER, [Ca2+] is maintained higher (between 10 and 250 μM free) than in the cytosol (50–250 nM) by the pumping activity of the sarco-ER Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) located in the ER membrane (15). This membrane holds intracellular channel that allow Ca2+ efflux from the ER down its concentration gradient; the InsP3 receptor (InsP3R), a ligand-gated Ca2+ channel that opens after InsP3 binding (16). Besides InsP3 binding, Ca2+ interaction with high-affinity (activation) sites on the cytoplasmic side of the InsP3R is essential for channel opening. In fact, Ca2+ and InsP3 operate as co-agonists. Ca2+ signal amplification and spreading phenomena, involving assemblies of InsP3Rs originate from this synergistic role of Ca2+ (17). The large and abrupt [Ca2+]i increase, triggered by InsP3Rs activation results from the combination of Ca2+ released and its amplification by Ca2+ induced Ca2+ release [CICR; (18)]. Even if cytosolic InsP3 remains high, Ca2+ efflux often ceases because Ca2+ binds to a low-affinity (inactivating) site of the receptor, which closes the InsP3R channel. This occurs when cytosolic Ca2+ close to the InsP3Rs is high, i.e., after an episode of fast release. As in most pituitary cells, agonist stimulation in gonadotrophs produce a [Ca2+]i peak which decays to sustained Ca2+ level (plateau phase). At intermediate GnRH concentration the initial Ca2+ spike is often followed by large [Ca2+]i oscillations resulting from opening and closing cycles of the InsP3R channels as a consequence of [Ca2+]i fluctuations near its cytoplasmic side (19). The frequency of these Ca2+ oscillations is determined by the dose of GnRH applied and the intracellular (InsP3) reached (20) (Figure 1).

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations can be reproduced with mathematical models that include a Ca2+ gradient between the ER lumen and the cytosol maintained by a SERCA Ca2+ pump, Ca2+ influx trough voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and InsP3R channels co-activated by InsP3 and low [Ca2+]i, and inactivated by high [Ca2+]i (8, 15, 21, 22). Nonetheless, Ca2+ oscillations in real cells requires the precise coordination of Ca2+ mobilization/uptake/extrusion mechanisms, it is for it that immortalized gonadotroph cell lines αT3–1 (21) and LβT2 (23) are not good cell models for studies on GnRH-induced calcium signaling and modulation of voltage-gated calcium influx, as well as goldfish (24, 25) and immature mammalian gonadotrophs, since these cells respond to GnRH with non-oscillatory amplitude-modulated Ca2+ signals. When SERCA pumps in gonadotrophs are blocked by thapsigargin, the agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations become non-oscillatory biphasic responses (8, 26). Therefore different factors, i.e., the amount and speed of InsP3 production, the total number of InsP3R channels available for activation, the rate of Ca2+ leakage from the store and the efficiency of the SERCA Ca2+ pump vary from cell to cell, and they ultimately determine the characteristics of gonadotrophs Ca2+ signaling patterns. It is important to note that the oscillatory behavior is intrinsic to the Ca2+ handling properties of gonadotrophs (17).

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone produces Ca2+ oscillations: i.e., large Ca2+ spikes, arising from a flat baseline as well as smaller sinusoidal Ca2+ oscillations superimposed on an elevated plateau. Under sustained GnRH stimulation, the amplitude of these Ca2+ spikes gradually diminishes, probably due to intracellular Ca2+ pool depletion, until a “plateau” without oscillations is reached. Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels is essential to maintain this plateau, and also for the replenishment of intracellular Ca2+ pools. GnRH induces continuous AP firing periodically interrupted by hyperpolarizations, which occur in phase with each Ca2+ elevation, and resulting from the opening of Ca2+ dependent SK-type K+ channels (6, 27). Immediately after each hyperpolarization, the cell fires a burst of APs, which open Ca2+ channels allowing Ca2+ influx, predominantly high-voltage – activated L-type calcium channels. This Ca2+ entry does not contribute to Ca2+ elevation or gonadotropin secretion, but is crucial for refilling the intracellular Ca2+ pools (20) (Figure 1).

Oscillatory Ca2+ signals in gonadotrophs can also be elicited by endothelin (ET) (28, 29), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, (PACAP) (30), and substance P (SP) (31). Conversely, neuropeptide Y (NPY) and melatonin, in neonatal gonadotrophs, inhibit GnRH-induced Ca2+ signals and gonadotropin secretion. Lactotrophs, gonadotrophs, and somatotrophs produce ETs, and gonadotrophs express ET receptors (32) under the control of ovarian steroid hormones, suggesting a paracrine function. ET binding, leads to Gq/11 activation, intracellular Ca2+ fluctuations, and gonadotropin secretion (29). SP, which is a weaker agonist than GnRH, produces amplitude-modulated [Ca2+]i responses and secretion in gonadotrophs (31), being the first phase of secretion dependent of intracellular Ca2+ release, and the second phase Ca2+ influx-dependent. The hypothalamic factor PACAP which stimulates cAMP production and potentiates gonadotropin release (33), also induces Ca2+ oscillations in rat gonadotrophs through activation of PVR1, a G-protein-coupled receptor and InsP3 production (30). The activation of coupled Gi/o melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2, expressed in gonadotrophs only at neonatal stage, inhibits both calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels and calcium mobilization from intracellular stores, decreasing intracellular cAMP production and protein kinase A (PKA) activity, with a consequent diminution on gonadotropin secretion (34–36); tonic melatonin inhibition of immature gonadotrophs prevents premature initiation of puberty. NPY inhibits GnRH-induced Ca2+ signaling and LH release (37); its receptors Y1 and Y5 expression on gonadotrophs is regulated by estrogens (38).

Ca2+ Signaling Patterns and Secretion in Gonadotrophs is Dependent on GnRH Concentration

Dissociated pituitary gonadotrophs respond to increasing doses of GnRH with a stereotyped progression of intracellular Ca2+ signaling: i.e., subthreshold GnRH concentrations produce either small monophasic Ca2+ transients or irregular, small Ca2+ spikes. With higher GnRH concentrations (0.1–10 nM) regular, oscillatory, frequency-modulated, large Ca2+ transients (baseline Ca2+ spiking) are produced. Eventually (∼50–100 nM GnRH), these Ca2+ spikes fuse into an amplitude-modulated biphasic Ca2+ response (9, 10, 39) which comprises two variants; biphasic oscillatory and biphasic non-oscillatory, also known as spike-plateau (40). It is reasonable to assume that different Ca2+ release patterns observed with increasing doses of GnRH underlie the dose-dependent increase of gonadotropin secretion. Nonetheless, it has also been suggested that these patterns encode other cell functions. For instance, spike-plateau Ca2+ responses were associated to LH secretion and oscillatory Ca2+ responses to the synthesis of LH β-subunits (9). Later, it was established that GnRH-induced Ca2+ oscillations trigger exocytosis (41) and that both oscillatory and spike-plateau Ca2+ signals can initiate LH release (10, 40). Furthermore, gonadotrophs do not respond in the same way to the secretagogue: i.e., individual cells can respond with different patterns of activity to the same GnRH concentration (40). Conversely, when the same dose of GnRH is applied repetitively, individual cells respond with similar latency and signaling pattern (11). It remains to be established which cellular aspects determine the Ca2+ signals displayed by individual gonadotrophs in response to GnRH and how these different patterns affect gonadotropin synthesis and secretion. Moreover, LH and FSH are secreted through parallel pathways (see below) and hormones that alter their synthesis, release, and/or storage can dynamically regulate their output.

Gonadotropin Exocytosis. Contribution of VGCC-Mediated Ca2+ Influx and Intracellular Ca2+ Release

A rise in [Ca2+]i is the key signal to trigger regulated exocytosis in neuronal and endocrine tissues. Endocrine cell models used to study the role of Ca2+ in exocytosis include adrenal chromaffin and PC12 cells (42–46), pancreatic β cells (47–49), and pituitary cells (6, 50). Cytosolic Ca2+ levels regulate several maturation steps that secretory vesicles must undergo prior to fusion, like priming of secretory vesicles (51). An entirely different phenomena occurs when [Ca2+]i rises abruptly, promoting the fusion of docked secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane (47, 52). In contrast to nerve synapses, where Ca2+ influx is primarily responsible for this abrupt [Ca2+]i rise, exocytosis in endocrine cells is triggered to a large extent by Ca2+ released from intracellular stores (17, 53).

Ca2+ controls the fusion of secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane to release neurotransmitters and hormones when is needed [regulated exocytosis, (51)]. The first phase of GnRH-induced exocytosis in gonadotrophs is mediated by InsP3-sensitive Ca2+ pools, while the second “plateau” phase of secretion involves voltage-gated Ca2+ influx (54). GnRH-InsP3 induced Ca2+ oscillations produce much greater exocytosis than the simple general rise in [Ca2+]i induced by micropipette injection or uncaging [Ca2+]i (5, 41). This suggests that in contrast with other pituitary cell types, the formation of sub-plasmalemmal microdomains of high Ca2+ in gonadotrophs is insufficient to induce vesicular fusion. Instead large Ca2+ signals that propagate across the entire cell are needed to accomplish this task (6). Exocytosis can be directly monitored electrically as changes in membrane capacitance due to the addition of new plasma membrane. Using capacitance measurements, exocytosis is detected in gonadotrophs whenever [Ca2+] rises above 300 nM (55), but for strong exocytosis high [Ca2+]i with half maximal concentration of 16 μM are required (6). When the responses induced by GnRH are oscillatory, step increases in membrane capacitance can be seen in each Ca2+ spike (40, 41, 55). The first Ca2+ oscillations elicit the largest exocytosis events, returning to full capacity within about 2 min (5). GnRH-induced secretion continues in the absence of external Ca2+, but ceases when [Ca2+] rises are blocked by the introduction of a strong intracellular Ca2+ buffer (41).

Secretory granules must undergo a well-defined series of events: (1) recruitment, (2) tethering at the plasma membrane, (3) priming, and (4) vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane. Regulated hormone secretion is a Ca2+-dependent exocytosis that uses the secretory vesicle synaptotagmin as the Ca2+ sensor and is mediated by SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors) proteins as effectors. Syntaxin, SNAP25 (synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa in molecular weight), and synaptobrevin (vesicle-associated membrane protein, VAMP, also termed vSNARE) constitute SNARE proteins. Syntaxin and SNAP25 (also known as “target” tSNAREs) are the plasma membrane proteins to which VAMP couples (Figure 1). Then, vSNAREs and tSNAREs form trans-SNARE complexes, which join secretory vesicles and plasma membrane (56–58). Vesicle priming, another Ca2+-dependent step in exocytosis probably involves early SNARE complex formation (particularly tSNARE), before its association to the trans-SNAREs. Finally, synaptotagmin detects the [Ca2+] elevation and provides the extra drive needed to overcome the energy barrier of lipid-to-lipid interaction, allowing membrane fusion (58). The use of high-resolution microscopy techniques have allowed to demonstrate in PC12 cells that tSNARE molecules are distributed on the plasma membrane in areas of low and high density, and in contrast to current models of SNARE-driven membrane fusion (59), this data suggest that secretory vesicles are targeted over areas of low tSNARE density as sites of docking, hence a relatively low number of tSNAREs close to the secretory vesicle (less than seven) are sufficient to drive membrane fusion. Moreover, using atomic forces microscopy and scanning electron microscopy it has been described that gonadotrophs mainly present “single and simple fusion pore” with diameter ranging from 100 to 500 nm, which appear more frequently after stimulation with GnRH; this pore configuration supports the idea of a “kiss and stay” mechanism for the exocytosis process (60), in addition pores of 20–40 nm diameter have also been found, probably representing the constitutive pathway of gonadotropins (60).

FSH and LH Differential Secretion Under Physiological Conditions

Along the follicular phase of the estrus cycle, LH secretion is maximal while FSH secretion is reduced; even though gonadotrophs secrete both hormones, the mechanisms underlying this differential release are unclear. FSH appears to be released mostly through the constitutive pathway in accordance to its rate of synthesis. Conversely, LH-containing granules are released through the regulated pathway in response to GnRH, with no effect on LHβ mRNA production (61). Moreover, LH and FSH appear to be packaged into different secretory granules (62). Large, moderately electron-dense granules show antigenicity for FSH, LH, and chromogranin A (CgA), while smaller, electron-dense storage granules released by GnRH contain LH and secretogranin II (SgII) (3); thereby protein sorting domains in the β subunit of gonadotropins and the association with certain proteins may be responsible for differential sorting and packaging of LH and FSH into different secretory granules (3). The movement of these granules toward the membrane defining a secretory pathway and differential exocytosis could explain the disparity on the gonadotropins secretion (63). Accordingly, in LβT2 mouse cells, FSH released in response to activin/GnRH is constitutively secreted via a granin-independent pathway; while LH is released in response to GnRH is co-released with SgII via a regulated, granin-dependent pathway (64).

Gonadotropin subunits (α-GSU, FSHβ, and LHβ) mRNAs levels, which reflect changes in gene transcription in pituitary gonadotrophs, are GnRH pulse frequency modulated (65–67). GnRH pulses (30–60 min interval), preferentially increases synthesis and secretion of LH by the mediation of the transcription factor Egr-1 (68–71); whereas slower GnRH pulsing (120–240 min interval) favors FSH secretion (65–67, 72) by the activation of PKA (73–75). There is no a definitive explanation to how GnRH pulses can activate in a different manner gonadotropin subunit gene transcription; nevertheless several routes have been proposed which may contribute to this regulation; one is through the increase on Ca2+ levels and PKC activation, which as a consequence activated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, culminating in an activation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2, cJun NH2-terminale kinase (JNK), p38 MAPK, and ERK 5 (76–80), it is also believe that the rise in [Ca2+]i, activates a calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CAMK2), whose autophosphorylation could be important in transmitting Ca2+ pulse frequency and amplitude signals, as fast and high-amplitude Ca2+ influxes, which results in greater and/or sustained Ca2+/CALM1 levels (79, 81) (Figure 1). GnRH pulses at lower frequency selectively increase the expression of PACAP and its receptor (PAC1-R) in gonadotrophs (82), where they subsequently stimulate the synthesis of gonadotropin subunits (83).

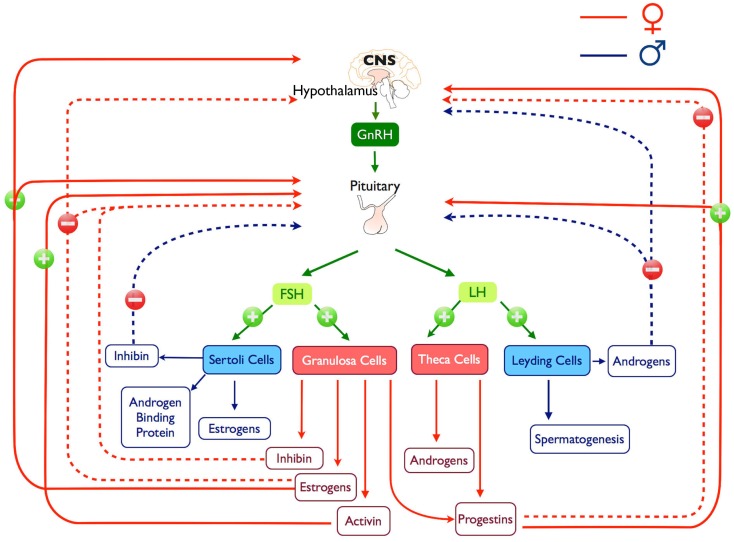

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone-induced LH and FSH synthesis and secretion are modulated by steroid hormones, such as estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, in addition to peptide hormones, such as activin, inhibin, and follistatin (Figures 1 and 2). This modulation occurs principally through gonadal feedback at the pituitary and hypothalamus level (84–86). During most part of the female reproductive cycle and in males, pulsatile GnRH release drives tonic gonadotropin secretion (84, 87) while steroids and inhibins provide negative feedback to limit further gonadotropin stimulation and maintaining low circulating levels of gonadotropins; in females, this happens until the pre-ovulatory surge when, in response to low levels of progesterone (88) and an increase in estrogen, feedback switches to positive (89), producing changes on GnRHergic neurons (90) and gonadotrophs (91), which results in increased LH and FSH secretion (Figure 2). In some female species a secondary FSH surge occurs after ovulation when LH levels are already low, this rise produces the recruitment of the next cohort of follicles and it is GnRH independent (92) and more likely depends on the reduction of circulating inhibin (93).

Figure 2.

Representation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis, positive and negatives feedback loops and products are illustrated.

Estradiol (E) exerts a direct action at the pituitary level through its α-receptor (94–97), increasing gonadotroph responsiveness to GnRH (98–100) raising synthesis and insertion of GnRH receptor into gonadotroph membrane (86, 91, 101–104) and decreasing the concentration of GnRH needed to produce the threshold response and frequency of Ca2+ spiking (101, 105, 106). Nevertheless, these actions seems to be and indirect action that depends of the increased expression produced by GnRH on its own receptor (101, 103, 107–109). Besides these changes, during the gonadotropin surge, the pituitary gland shows cellular modifications, implying an augmentation on the number of secreting gonadotrophs (98, 104) and hypertrophy and re-organization of its intracellular organelles (110–112). However, it has been documented that E can act to suppress the transcriptional rate of LH subunit genes. Controversial results have been reported for FSHβ synthesis (113–117), although serum levels of both hormones increased markedly.

Progesterone (P) exerts some of its effects at hypothalamic level, decreasing GnRH secretion and pulse frequency (91, 103) contributing to the abrupt decline in gonadotropin levels. P does not inhibit LH secretion induced by GnRH (100, 118) but it can stimulate murine FSHβ promoter activity alone or in synergy with activins (103). In dependence with the time of exposition, P can either inhibit or facilitate the estrogen-induced LH surge during the rat estrous cycle (100, 103, 119). P modulates the E effect on GnRH production of LH surge by the modulation of Ca2+ mobilization and Ca2+ entry to gonadotrophs. In E-primed cells P alters the intracellular Ca2+ signaling patterns produced by GnRH. In the short-term P treatment shifts subthreshold [Ca2+]i responses to oscillatory, and oscillatory to biphasic responses; in contrast, long-term P exposure led to decreased GnRH sensitivity, changing oscillatory response into subthreshold [Ca2+]i response profiles (105, 106).

Androgens [testosterone (T) and 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT)] are important component of the male gonadal feedback and they act either at the hypothalamic level by regulating the secretion of GnRH into the hypophyseal portal circulation (120–122), directly at the pituitary level (99) or by the combination of both sites (123) (Figure 2).

At hypothalamic level, T reduce GnRH synthesis (122, 124–127) and pulsatile patterns of GnRH release (128–131). At pituitary level, it is known that testosterone and more dramatically DHT inhibits LH synthesis and GnRH-induced LH secretion in a concentration and time dependent manner (132–137), but increase basal FSH secretion and synthesis (138, 139). In castrated rats it has been shown that LH secretion increase (140, 141) as well as gonadotrophs size and number (140, 142, 143). These hypertrophied cells are called castration cells (144–146), and they present a dilated rough ER and an extended Golgi complex (147, 148). On these cells, the secretion granules content are progressively diminished (149) and their cisternae fused to form large vacuoles that originated the typical “signet ring cell” (148, 150, 151).

It is widely accepted that in gonadotrophs an increase in [Ca2+]i is essential for the transduction of GnRH signal; T but specially DHT regulate GnRH-induced [Ca2+]i variations (152) changing the type of calcium patterns (153), these effects are not seen in all species (145) and it could be related with the influence of this hormone on the regulation of the GnRH receptor density (154–156) and the change in their sensitivity to the GnRH stimulus (134).

Tobin and collaborators (153) demonstrated that in cultured gonadotrophs of gonadectomized male rats, the relationship between GnRH concentration and the type of intracellular Ca2+ response is altered, most gonadotrophs (∼70%) show oscillatory responses regardless of the GnRH concentration. Correlated with this results it has been demonstrated that in T or DHT treated cells, there is an inhibition of the GnRH increase in [Ca2+]i; at low GnRH doses (0.1 nM) 30% of gonadotrophs were unable to initiated threshold spiking and in the residual cells the frequency of oscillations decreased, as in controls, androgen treated cells, respond with a spike-plateau type of signal to 1 nM GnRH, but the frequency of spiking was also reduced (134, 152). Finally at high dose GnRH (100 nM) induce biphasic elevations of [Ca2+]i with a minor reduction in the amplitude (134). Testosterone inhibits both phases of GnRH-stimulated LH secretory responses, the early extracellular Ca2+-independent spike phase and the sustained Ca2+ and extracellular Ca2+-dependent plateau phase (134). These results suggest that androgens act on the efficacy of the agonist to release Ca2+, leading to a decrease in the secretory output.

As it has been previously established, secretion of FSH and LH are not co-ordinately regulated, their discordant regulation must be related to differential intracellular responses to several stimuli, factors as activins, inhibins, and follistatin, may play a key role on establishing such differences. In this regard, activins which are produced in a variety of tissues, including gonadotrophs, stimulates FSHβ transcription (132, 157–159) and enhance its sensitivity to GnRH by up-regulation of the GnRH receptor expression (92, 160). Contrary, inhibins which are produced in Sertoli and granulosa cells as well as in gonadotrophs (161), have been shown to rapidly reduce FSHβ synthesis and secretion independently of GnRH (162), by binding to activin receptors on gonadotrophs preventing the assembly of active signaling complexes (92).

Follistatins, which are glycoprotein ubiquitously expressed (including gonadotrophs and follicle stellated cells) bind to activins with high-affinity modulating its actions (92, 132, 160, 163). Activin and follistatin function in a reciprocal feedback loop altering their secretion, internalization, and degradation (92, 114, 160, 163), modifying the rise and fall of biosynthesis and secretion across the reproductive cycle (160, 163).

One mechanism that contributes to differential FSH and LH production may be related to the observation that different patterns of GnRH pulses produce differential effects on inhibin/activin and follistatin mRNA levels (160). Estrogen, progesterone, testosterone, inhibin, activin, follistatin, and hypothalamic GnRH, may combine to distinct regulate LH and FSH during the reproductive cycle (97).

Gonadotrophs Activity at the Tissue Level

Endocrine cells are organized in three-dimensional networks, which facilitate the coordination of the activity of thousands of individual cells to respond to different regulation factors and achieve hormone output (164, 165). The magnitude of the hormone pulses into the systemic circulation is apparently not just the simple addition of the individual endocrine activity, instead, biophysical and biochemical interactions in the whole tissue must be essential for in vivo organization. However, as it has been described in this and other works, most of the studies have been done in individual cell activity where this networks and relations are disrupted, due to methodological difficulties, just few recently approaches has been done in the understanding of the endocrine activity in a tissue context.

In this regard, the distribution of gonadotrophs in fixed and live slices at different female reproductive stages has been analyzed (166). Across different physiological stages, pituitary gonadotrophs shows changes in their distribution within the gland and in response to GnRH stimulation (166), this might represent and adaptation to better respond at different conditions.

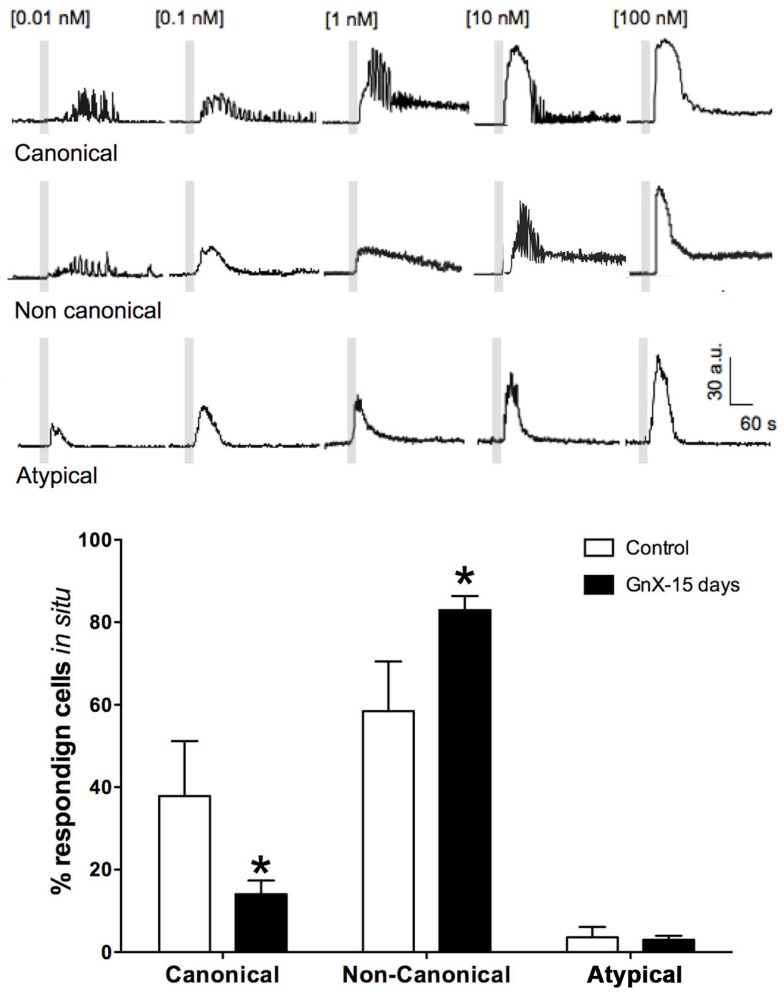

The possibility of changes in gonadotrophs activity within its tissue context and physiological conditions was recently addressed using Ca2+ imaging in male mouse acute pituitary slices (11, 145). Cells in this preparation are amenable to functional studies in their native environment. We showed that rather than a constant number of gonadotrophs responding to GnRH stimulus, the number of responding cells grew with increasing GnRH concentration (GnRH), and in general, gonadotrophs Ca2+ signaling resembled that recorded in primary cultures (11, 145). However, Ca2+ imaging in acute mouse pituitary slices revealed Ca2+ signaling patterns unique to in situ conditions, gonadotrophs (58%) under increasing doses of GnRH stimulation exhibited a progression of Ca2+ signaling patterns termed “non-canonical” [i.e., oscillatory responses at a given (GnRH) and transient responses at both lower and higher concentrations as described before in this review; Figure 3], and some of them (3.6%) even showed atypical (non-oscillatory) responses, regardless of the (GnRH) used (145). Furthermore, responses to a given dose of GnRH varied considerably from one cell to another, reflecting a range of dose-response properties in the in situ gonadotroph population.

Figure 3.

Percentage of gonadotrophs that display different GnRH dose-response intracellular Ca2+ signaling patterns rises in response to increasing GnRH: canonical ([Ca2+]i oscillations of increasing frequency at low-medium GnRH concentration and spike-plateau at saturating GnRH concentration), non-canonical (disordered sequence of oscillatory and spike-plateau [Ca2+]i signals in response to increasing GnRH concentrations), and atypical (non-oscillatory, transient [Ca2+]i); open bars represent data from intact mice and black bars those of castrated mice after 15 post-GnX. After orchidectomy, non-canonical responses increased, while the fraction of cells with canonical responses declined. Differences between intact and post-GnX, for both canonical and non-canonical responses are significant. *p < 0.05 versus the control (two way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test). Parts of this figure were originally published in Durán-Pastén et al., (145).

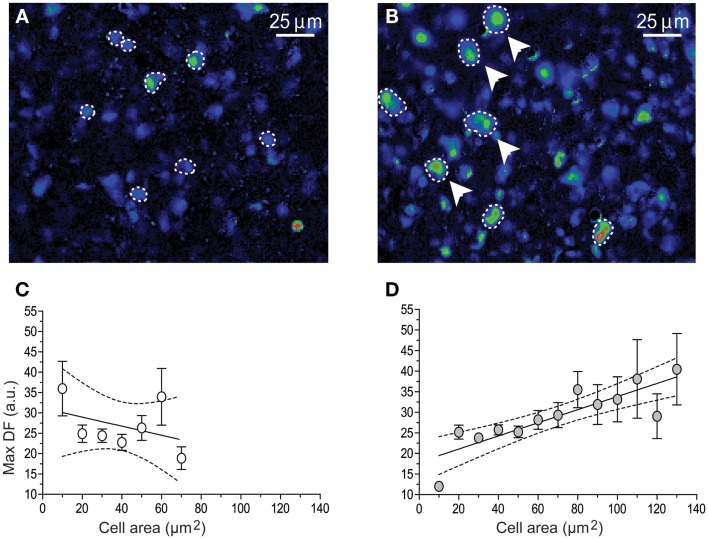

As it has been described in this review, following the removal of the gonads, the population of pituitary gonadotrophs undergoes drastic functional and morphological modifications concomitantly with the large (five to sixfold) increase in gonadotropin secretion that characterizes this condition (123, 154, 167, 168) some changes as amplitude and frequency of GnRH-induced Ca2+ signaling has been reported in dissociated cells (10) and there is no difference with respect of what it has been reported in acute pituitary slices from 15 and 45 days castrated male mice (GnX) (145). Nevertheless, other characteristics on the intracellular Ca2+ signaling appear to be different; gonadotrophs of pituitary slices from GnX responding with “non-canonical” sequences of Ca2+ signaling (described earlier in this review) to increasing GnRH were significantly augmented (80% of GnRH responding gonadotrophs) and “canonical” sequences were significantly reduced (145) (Figure 3), indicating that probably this sequences of Ca2+ signaling in response to GnRH are modulated by paracrine and systemic factors as testosterone, allowing gonadotrophs to adapt to different physiological requirements. Additionally, median effective dose (ED50) for GnRH decreased from 0.17 nM (control) to 0.07 nM after GnX, suggesting an increased GnRH responsiveness of the gonadotroph population (145). Different sizes of gonadotrophs are present in intact mice pituitary gland, most gonadotrophs (97%) were smaller than 60 μm2 with a mean of 31.3 ± 0.6 μm2 in area and even if large interindividual variation on the peak amplitude of Ca2+ transients (Max DF) was seen, no matter the size of the cell, they generated intracellular Ca2+ signals smaller than 40 fluorescence arbitrary units (a.u.) poorly correlated with the cell size (Figure 4). By contrast it is reported that 15-day castrated male mouse pituitary gonadotrophs, whose size increase to a mean of 54.4 ± 1.24 μm2 and 26% of cells larger than 60 μm2 present less variation on the Ca2+ peak amplitude and significantly higher correlation of this with the cell size (i.e., hypertrophied gonadotrophs tended to generate Ca2+ signals of greater amplitude) (145) (Figure 4), suggesting that in this condition, Ca2+ peak amplitude correlated with cell size, and that hypertrophied gonadotrophs tended to produce stronger GnRH-induced Ca2+ signals.

Figure 4.

Graphs illustrating the relation between gonadotrophs area size versus the peak amplitude of GnRH-induced Ca2+ transients. Fluo-4 fluorescence images of 100 nM GnRH responding gonadotrophs (dashed lines) in intact (A) and 15 days post-GnX (B) mice pituitary slice, arrows pointed bigger gonadotrophs. (C,D) shows the relationship between [Ca2+]i transients peak amplitude (Max DF) and cell area (Mean ± SE). (C) Intact (n = 6) and (D) 15 days post-GnX (n = 6) mice pituitary slices are represented; dashed line represent the confidence interval. (C) y = −0.11* ± 0.11x + 31.1 ± 5.1, R2 = 0.15, p > 0.05, Pearson r = 0.38, p > 0.05 and (D) y = 0.16* ± 0.02x + 17.88 ± 2.3, R2 = 0.73, p < 0.05, Pearson r = 0.85, p < 0.05. Parts of this figure were originally published in Durán-Pastén et al., (145).

Functional adaptation of the gonadotrophs in the pituitary gland to different external and internal conditions may involucrate not just alterations in cell number, size, and morphology, as it has been considered for many years, recent methodological techniques allowed us to understand that it is a more complicated process that involucrates different aspects at the cellular physiology level but in coordination with the whole tissue environment.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Dr. Arturo Hernández who provided invaluable insights throughout this work. We are also grateful with Daniel Diaz for his support on data analysis and figure design. Grant support: PAPIIT IN222613 and IN222413, CONACYT 166430.

References

- 1.Kaiser UB. Gonadotropin hormones. In: Melmed S, editor. The Pituitary. Amsterdam: Academic Press; (2011). 731 p. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moriarty GC. Immunocytochemistry of the pituitary glycoprotein hormones. J Histochem Cytochem (1976) 24:846–63 10.1177/24.7.60435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson L. Intracellular mechanisms triggering gonadotropin secretion. Rev Reprod (1996) 1:193–202 10.1530/ror.0.0010193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stojilkovic SS, Zemkova H, Van Goor F. Biophysical basis of pituitary cell type-specific Ca2+ signaling-secretion coupling. Trends Endocrinol Metab (2005) 16:152–9 10.1016/j.tem.2005.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tse FW, Tse A, Hille B, Horstmann H, Almers W. Local Ca2+ release from internal stores controls exocytosis in pituitary gonadotrophs. Neuron (1997) 18:121–32 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)80051-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stojilkovic SS. Pituitary cell type-specific electrical activity, calcium signaling and secretion. Biol Res (2006) 39:403–23 10.4067/S0716-97602006000300004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stojilkovic SS, Krsmanovic LZ, Spergel DJ, Catt KJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: intrinsic pulsatility and receptor-mediated regulation. Trends Endocrinol Metab (1994) 5:201–9 10.1016/1043-2760(94)90078-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iida T, Stojilkovic SS, Izumi S, Catt KJ. Spontaneous and agonist-induced calcium oscillations in pituitary gonadotrophs. Mol Endocrinol (1991) 5:949–58 10.1210/mend-5-7-949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leong DA, Thorner MO. A potential code of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-induced calcium ion responses in the regulation of luteinizing hormone secretion among individual gonadotrophs. J Biol Chem (1991) 266:9016–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomic M, Cesnajaj M, Catt KJ, Stojilkovic SS. Developmental and physiological aspects of Ca2+ signaling in agonist-stimulated pituitary gonadotrophs. Endocrinology (1994) 135:1762–71 10.1210/en.135.5.1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez-Cardenas C, Hernandez-Cruz A. GnRH-induced [Ca2+]i-signalling patterns in mouse gonadotrophs recorded from acute pituitary slices in vitro. Neuroendocrinology (2010) 91:239–55 10.1159/000274493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naor Z. Signaling by G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR): studies on the GnRH receptor. Front Neuroendocrinol (2009) 30:10–29 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stojilkovic SS, Iida T, Merelli F, Torsello A, Krsmanovic LZ, Catt KJ. Interactions between calcium and protein kinase C in the control of signaling and secretion in pituitary gonadotrophs. J Biol Chem (1991) 266:10377–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu H, Hille B, Xu T. Sensitization of regulated exocytosis by protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2002) 99:17055–9 10.1073/pnas.232588899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li YX, Keizer J, Stojilkovic SS, Rinzel J. Ca2+ excitability of the ER membrane: an explanation for IP3-induced Ca2+ oscillations. Am J Physiol (1995) 269:C1079–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stojilkovic SS, Tabak J, Bertram R. Ion channels and signaling in the pituitary gland. Endocr Rev (2010) 31:845–915 10.1210/er.2010-0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stojilkovic SS. Molecular mechanisms of pituitary endocrine cell calcium handling. Cell Calcium (2012) 51:212–21 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stojilkovic SS, He ML, Koshimizu TA, Balik A, Zemkova H. Signaling by purinergic receptors and channels in the pituitary gland. Mol Cell Endocrinol (2010) 314:184–91 10.1016/j.mce.2009.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tse A, Hille B. GnRH-induced Ca2+ oscillations and rhythmic hyperpolarizations of pituitary gonadotrophs. Science (1992) 255:462–4 10.1126/science.1734523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stojilkovic SS, Kukuljan M, Tomic M, Rojas E, Catt KJ. Mechanism of agonist-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations in pituitary gonadotrophs. J Biol Chem (1993) 268:7713–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li YX, Rinzel J, Keizer J, Stojilkovic SS. Calcium oscillations in pituitary gonadotrophs: comparison of experiment and theory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1994) 91:58–62 10.1073/pnas.91.1.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Young GW, Keizer J. A single-pool inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-receptor-based model for agonist-stimulated oscillations in Ca2+ concentration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1992) 89:9895–9 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas P, Mellon PL, Turgeon J, Waring DW. The L beta T2 clonal gonadotrope: a model for single cell studies of endocrine cell secretion. Endocrinology (1996) 137:2979–89 10.1210/en.137.7.2979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strandabo RA, Hodne K, Ager-Wick E, Sand O, Weltzien FA, Haug TM. Signal transduction involved in GnRH2-stimulation of identified LH-producing gonadotrophs from lhb-GFP transgenic medaka (Oryzias latipes). Mol Cell Endocrinol (2013) 372:128–39 10.1016/j.mce.2013.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mollard P, Kah O. Spontaneous and gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated cytosolic calcium rises in individual goldfish gonadotrophs. Cell Calcium (1996) 20:415–24 10.1016/S0143-4160(96)90004-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tse A, Tse FW, Hille B. Calcium homeostasis in identified rat gonadotrophs. J Physiol (1994) 477(Pt 3):511–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kukuljan M, Vergara L, Stojilkovic SS. Modulation of the kinetics of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations by calcium entry in pituitary gonadotrophs. Biophys J (1997) 72:698–707 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78706-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanyicska B, Burris TP, Freeman ME. Endothelin-3 inhibits prolactin and stimulates LH, FSH and TSH secretion from pituitary cell culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (1991) 174:338–43 10.1016/0006-291X(91)90525-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stojilkovic SS, Merelli F, Iida T, Krsmanovic LZ, Catt KJ. Endothelin stimulation of cytosolic calcium and gonadotropin secretion in anterior pituitary cells. Science (1990) 248:1663–6 10.1126/science.2163546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rawlings SR, Demaurex N, Schlegel W. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide increases [Ca2]i in rat gonadotrophs through an inositol trisphosphate-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem (1994) 269:5680–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mau SE, Witt MR, Saermark T, Vilhardt H. Substance P increases intracellular Ca2+ in individual rat pituitary lactotrophs, somatotrophs, and gonadotrophs. Mol Cell Endocrinol (1997) 126:193–201 10.1016/S0303-7207(96)03988-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Freeman ME. Endothelin-like immunoreactivity in lactotrophs, gonadotrophs, and somatotrophs of rat anterior pituitary gland are affected differentially by ovarian steroid hormones. Endocrine (2001) 14:263–8 10.1385/ENDO:14:2:263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Culler MD, Paschall CS. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) potentiates the gonadotropin-releasing activity of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. Endocrinology (1991) 129:2260–2 10.1210/endo-129-4-2260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balik A, Kretschmannova K, Mazna P, Svobodova I, Zemkova H. Melatonin action in neonatal gonadotrophs. Physiol Res (2004) 53(Suppl 1):S153–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zemkova H, Vanecek J. Inhibitory effect of melatonin on gonadotropin-releasing hormone-induced Ca2+ oscillations in pituitary cells of newborn rats. Neuroendocrinology (1997) 65:276–83 10.1159/000127185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zemkova H, Vanecek J. Dual effect of melatonin on gonadotropin-releasing-hormone-induced Ca(2+) signaling in neonatal rat gonadotropes. Neuroendocrinology (2001) 74:262–9 10.1159/000054693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shangold GA, Miller RJ. Direct neuropeptide Y-induced modulation of gonadotrope intracellular calcium transients and gonadotropin secretion. Endocrinology (1990) 126:2336–42 10.1210/endo-126-5-2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill JW, Urban JH, Xu M, Levine JE. Estrogen induces neuropeptide Y (NPY) Y1 receptor gene expression and responsiveness to NPY in gonadotrope-enriched pituitary cell cultures. Endocrinology (2004) 145:2283–90 10.1210/en.2003-1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stojilkovic SS, Tomic M. GnRH-induced calcium and current oscillations in gonadotrophs. Trends Endocrinol Metab (1996) 7:379–84 10.1016/S1043-2760(96)00189-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas P, Waring DW. Modulation of stimulus-secretion coupling in single rat gonadotrophs. J Physiol (1997) 504(Pt 3):705–19 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.705bd.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tse A, Tse FW, Almers W, Hille B. Rhythmic exocytosis stimulated by GnRH-induced calcium oscillations in rat gonadotropes. Science (1993) 260:82–4 10.1126/science.8385366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alvarez YD, Marengo FD. The immediately releasable vesicle pool: highly coupled secretion in chromaffin and other neuroendocrine cells. J Neurochem (2011) 116:155–63 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia AG, Padin F, Fernandez-Morales JC, Maroto M, Garcia-Sancho J. Cytosolic organelles shape calcium signals and exo-endocytotic responses of chromaffin cells. Cell Calcium (2012) 51:309–20 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss JL. Ca(2+) signaling mechanisms in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Adv Exp Med Biol (2012) 740:859–72 10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marengo FD. Calcium gradients and exocytosis in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Cell Calcium (2005) 38:87–99 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neher E. A comparison between exocytic control mechanisms in adrenal chromaffin cells and a glutamatergic synapse. Pflugers Arch (2006) 453:261–8 10.1007/s00424-006-0143-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dolensek J, Skelin M, Rupnik MS. Calcium dependencies of regulated exocytosis in different endocrine cells. Physiol Res (2011) 60(Suppl 1):S29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoppa MB, Jones E, Karanauskaite J, Ramracheya R, Braun M, Collins SC, et al. Multivesicular exocytosis in rat pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia (2012) 55:1001–12 10.1007/s00125-011-2400-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wan QF, Dong Y, Yang H, Lou X, Ding J, Xu T. Protein kinase activation increases insulin secretion by sensitizing the secretory machinery to Ca2+. J Gen Physiol (2004) 124:653–62 10.1085/jgp.200409082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tse A, Lee AK, Tse FW. Ca2+ signaling and exocytosis in pituitary corticotropes. Cell Calcium (2012) 51:253–9 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin TF. Tuning exocytosis for speed: fast and slow modes. Biochim Biophys Acta (2003) 1641:157–65 10.1016/S0167-4889(03)00093-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Voets T. Dissection of three Ca2+-dependent steps leading to secretion in chromaffin cells from mouse adrenal slices. Neuron (2000) 28:537–45 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00131-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tse FW, Tse A. Regulation of exocytosis via release of Ca(2+) from intracellular stores. Bioessays (1999) 21:861–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naor Z, Harris D, Shacham S. Mechanism of GnRH receptor signaling: combinatorial cross-talk of Ca2+ and protein kinase C. Front Neuroendocrinol (1998) 19:1–19 10.1006/frne.1997.0162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hille B, Tse A, Tse FW, Almers W. Calcium oscillations and exocytosis in pituitary gonadotropes. Ann N Y Acad Sci (1994) 710:261–70 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb26634.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stojilkovic SS. Ca2+-regulated exocytosis and SNARE function. Trends Endocrinol Metab (2005) 16:81–3 10.1016/j.tem.2005.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jahn R, Scheller RH. SNAREs – engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2006) 7:631–43 10.1038/nrm2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martens S, McMahon HT. Mechanisms of membrane fusion: disparate players and common principles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2008) 9:543–56 10.1038/nrm2417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang L, Dun AR, Martin KJ, Qiu Z, Dunn A, Lord GJ, et al. Secretory vesicles are preferentially targeted to areas of low molecular SNARE density. PLoS ONE (2012) 7:e49514. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Savigny P, Evans J, McGrath KM. Cell membrane structures during exocytosis. Endocrinology (2007) 148:3863–74 10.1210/en.2006-1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farnworth PG. Gonadotrophin secretion revisited. How many ways can FSH leave a gonadotroph? J Endocrinol (1995) 145:387–95 10.1677/joe.0.1450387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Childs GV. Functional ultrastructure of gonadotropes: a review. Curr Top Neuroendocrinol (1986) 7:49–97 10.1007/978-3-642-71461-0_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McNeilly AS, Crawford JL, Taragnat C, Nicol L, McNeilly JR. The differential secretion of FSH and LH: regulation through genes, feedback and packaging. Reprod Suppl (2003) 61:463–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nicol L, McNeilly JR, Stridsberg M, McNeilly AS. Differential secretion of gonadotrophins: investigation of the role of secretogranin II and chromogranin A in the release of LH and FSH in LbetaT2 cells. J Mol Endocrinol (2004) 32:467–80 10.1677/jme.0.0320467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haisenleder DJ, Dalkin AC, Ortolano GA, Marshall JC, Shupnik MA. A pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulus is required to increase transcription of the gonadotropin subunit genes: evidence for differential regulation of transcription by pulse frequency in vivo. Endocrinology (1991) 128:509–17 10.1210/endo-128-1-509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martinez de la Escalera G, Choi AL, Weiner RI. Generation and synchronization of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulses: intrinsic properties of the GT1-1 GnRH neuronal cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1992) 89:1852–5 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shupnik MA. Effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone on rat gonadotropin gene transcription in vitro: requirement for pulsatile administration for luteinizing hormone-beta gene stimulation. Mol Endocrinol (1990) 4:1444–50 10.1210/mend-4-10-1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Halvorson LM, Ito M, Jameson JL, Chin WW. Steroidogenic factor-1 and early growth response protein 1 act through two composite DNA binding sites to regulate luteinizing hormone beta-subunit gene expression. J Biol Chem (1998) 273:14712–20 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Halvorson LM, Kaiser UB, Chin WW. The protein kinase C system acts through the early growth response protein 1 to increase LHbeta gene expression in synergy with steroidogenic factor-1. Mol Endocrinol (1999) 13:106–16 10.1210/me.13.1.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tremblay JJ, Drouin J. Egr-1 is a downstream effector of GnRH and synergizes by direct interaction with Ptx1 and SF-1 to enhance luteinizing hormone beta gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol (1999) 19:2567–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolfe MW, Call GB. Early growth response protein 1 binds to the luteinizing hormone-beta promoter and mediates gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated gene expression. Mol Endocrinol (1999) 13:752–63 10.1210/me.13.5.752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wildt L, Hausler A, Marshall G, Hutchison JS, Plant TM, Belchetz PE, et al. Frequency and amplitude of gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation and gonadotropin secretion in the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology (1981) 109:376–85 10.1210/endo-109-2-376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thompson IR, Ciccone NA, Xu S, Zaytseva S, Carroll RS, Kaiser UB. GnRH pulse frequency-dependent stimulation of FSHbeta transcription is mediated via activation of PKA and CREB. Mol Endocrinol (2013) 27:606–18 10.1210/me.2012-1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garrel G, Simon V, Thieulant ML, Cayla X, Garcia A, Counis R, et al. Sustained gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation mobilizes the cAMP/PKA pathway to induce nitric oxide synthase type 1 expression in rat pituitary cells in vitro and in vivo at proestrus. Biol Reprod (2010) 82:1170–9 10.1095/biolreprod.109.082925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ciccone NA, Xu S, Lacza CT, Carroll RS, Kaiser UB. Frequency-dependent regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone beta by pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone is mediated by functional antagonism of bZIP transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol (2010) 30:1028–40 10.1128/MCB.00848-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Melamed P, Savulescu D, Lim S, Wijeweera A, Luo Z, Luo M, et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone signalling downstream of calmodulin. J Neuroendocrinol (2012) 24:1463–75 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2012.02359.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pnueli L, Luo M, Wang S, Naor Z, Melamed P. Calcineurin mediates the gonadotropin-releasing hormone effect on expression of both subunits of the follicle-stimulating hormone through distinct mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol (2011) 31:5023–36 10.1128/MCB.06083-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lim S, Pnueli L, Tan JH, Naor Z, Rajagopal G, Melamed P. Negative feedback governs gonadotrope frequency-decoding of gonadotropin releasing hormone pulse-frequency. PLoS ONE (2009) 4:e7244. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burger LL, Haisenleder DJ, Aylor KW, Marshall JC. Regulation of intracellular signaling cascades by GNRH pulse frequency in the rat pituitary: roles for CaMK II, ERK, and JNK activation. Biol Reprod (2008) 79:947–53 10.1095/biolreprod.108.070987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haisenleder DJ, Yasin M, Marshall JC. Gonadotropin subunit and gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene expression are regulated by alterations in the frequency of calcium pulsatile signals. Endocrinology (1997) 138:5227–30 10.1210/en.138.12.5227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Koninck P, Schulman H. Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science (1998) 279:227–30 10.1126/science.279.5348.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Purwana IN, Kanasaki H, Oride A, Mijiddorj T, Shintani N, Hashimoto H, et al. GnRH-induced PACAP and PAC1 receptor expression in pituitary gonadotrophs: a possible role in the regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene expression. Peptides (2010) 31:1748–55 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kanasaki H, Purwana IN, Miyazaki K. Possible role of PACAP and its PAC1 receptor in the differential regulation of pituitary LHbeta- and FSHbeta-subunit gene expression by pulsatile GnRH stimulation. Biol Reprod (2013) 88:35. 10.1095/biolreprod.112.105601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Levine JE. New concepts of the neuroendocrine regulation of gonadotropin surges in rats. Biol Reprod (1997) 56:293–302 10.1095/biolreprod56.2.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Herbison AE. Multimodal influence of estrogen upon gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocr Rev (1998) 19:302–30 10.1210/er.19.3.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gregg DW, Schwall RH, Nett TM. Regulation of gonadotropin secretion and number of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors by inhibin, activin-A, and estradiol. Biol Reprod (1991) 44:725–32 10.1095/biolreprod44.4.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Steiner RA, Bremner WJ, Clifton DK. Regulation of luteinizing hormone pulse frequency and amplitude by testosterone in the adult male rat. Endocrinology (1982) 111:2055–61 10.1210/endo-111-6-2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hooley RD, Baxter RW, Chamley WA, Cumming IA, Jonas HA, Findlay JK. FSH and LH response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone during the ovine estrous cycle and following progesterone administration. Endocrinology (1974) 95:937–42 10.1210/endo-95-4-937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith MS, Freeman ME, Neill JD. The control of progesterone secretion during the estrous cycle and early pseudopregnancy in the rat: prolactin, gonadotropin and steroid levels associated with rescue of the corpus luteum of pseudopregnancy. Endocrinology (1975) 96:219–26 10.1210/endo-96-1-219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Libertun C, Orias R, McCann SM. Biphasic effect of estrogen on the sensitivity of the pituitary to luteinizing hormone-releasing factor (LRF). Endocrinology (1974) 94:1094–100 10.1210/endo-94-4-1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nett TM, Turzillo AM, Baratta M, Rispoli LA. Pituitary effects of steroid hormones on secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone. Domest Anim Endocrinol (2002) 23:33–42 10.1016/S0739-7240(02)00143-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bernard DJ, Fortin J, Wang Y, Lamba P. Mechanisms of FSH synthesis: what we know, what we don’t, and why you should care. Fertil Steril (2010) 93:2465–85 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schwartz NB, Channing CP. Evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1977) 74:5721–4 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wersinger SR, Haisenleder DJ, Lubahn DB, Rissman EF. Steroid feedback on gonadotropin release and pituitary gonadotropin subunit mRNA in mice lacking a functional estrogen receptor alpha. Endocrine (1999) 11:137–43 10.1385/ENDO:11:2:137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mercer JE, Phillips DJ, Clarke IJ. Short-term regulation of gonadotropin subunit mRNA levels by estrogen: studies in the hypothalamo-pituitary intact and hypothalamo-pituitary disconnected ewe. J Neuroendocrinol (1993) 5:591–6 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1993.tb00526.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mercer JE, Clements JA, Funder JW, Clarke IJ. Regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone beta and common alpha-subunit messenger ribonucleic acid by gonadotropin-releasing hormone and estrogen in the sheep pituitary. Neuroendocrinology (1989) 50:321–6 10.1159/000125240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Glidewell-Kenney C, Weiss J, Hurley LA, Levine JE, Jameson JL. Estrogen receptor alpha signaling pathways differentially regulate gonadotropin subunit gene expression and serum follicle-stimulating hormone in the female mouse. Endocrinology (2008) 149:4168–76 10.1210/en.2007-1807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Smith PF, Frawley LS, Neill JD. Detection of LH release from individual pituitary cells by the reverse hemolytic plaque assay: estrogen increases the fraction of gonadotropes responding to GnRH. Endocrinology (1984) 115:2484–6 10.1210/endo-115-6-2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Drouin J, Labrie F. Selective effect of androgens on LH and FSH release in anterior pituitary cells in culture. Endocrinology (1976) 98:1528–34 10.1210/endo-98-6-1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Batra SK, Miller WL. Progesterone decreases the responsiveness of ovine pituitary cultures to luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. Endocrinology (1985) 117:1436–40 10.1210/endo-117-4-1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Clarke IJ, Cummins JT, Crowder ME, Nett TM. Pituitary receptors for gonadotropin-releasing hormone in relation to changes in pituitary and plasma gonadotropins in ovariectomized hypothalamo/pituitary-disconnected ewes. II. A marked rise in receptor number during the acute feedback effects of estradiol. Biol Reprod (1988) 39:349–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Clayton RN, Solano AR, Garcia-Vela A, Dufau ML, Catt KJ. Regulation of pituitary receptors for gonadotropin-releasing hormone during the rat estrous cycle. Endocrinology (1980) 107:699–706 10.1210/endo-107-3-699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bauer-Dantoin AC, Weiss J, Jameson JL. Roles of estrogen, progesterone, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in the control of pituitary GnRH receptor gene expression at the time of the preovulatory gonadotropin surges. Endocrinology (1995) 136:1014–9 10.1210/en.136.3.1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ghosh BR, Wu JC, Strahl BD, Childs GV, Miller WL. Inhibin and estradiol alter gonadotropes differentially in ovine pituitary cultures: changing gonadotrope numbers and calcium responses to gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology (1996) 137:5144–54 10.1210/en.137.11.5144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ortmann O, Stojilkovic SS, Cesnjaj M, Emons G, Catt KJ. Modulation of cytoplasmic calcium signaling in rat pituitary gonadotrophs by estradiol and progesterone. Endocrinology (1992) 131:1565–7 10.1210/en.131.3.1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ortmann O, Merelli F, Stojilkovic SS, Schulz KD, Emons G, Catt KJ. Modulation of calcium signaling and LH secretion by progesterone in pituitary gonadotrophs and clonal pituitary cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol (1994) 48:47–54 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90249-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Clayton RN, Channabasavaiah K, Stewart JM, Catt KJ. Hypothalamic regulation of pituitary gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors: effects of hypothalamic lesions and a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist. Endocrinology (1982) 110:1108–15 10.1210/endo-110-4-1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Naik SI, Young LS, Charlton HM, Clayton RN. Pituitary gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor regulation in mice. II: females. Endocrinology (1984) 115:114–20 10.1210/endo-115-1-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nett TM, Crowder ME, Moss GE, Duello TM. GnRH-receptor interaction. V. Down-regulation of pituitary receptors for GnRH in ovariectomized ewes by infusion of homologous hormone. Biol Reprod (1981) 24:1145–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shupnik MA, Gharib SD, Chin WW. Estrogen suppresses rat gonadotropin gene transcription in vivo. Endocrinology (1988) 122:1842–6 10.1210/endo-122-5-1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gharib SD, Wierman ME, Badger TM, Chin WW. Sex steroid hormone regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone subunit messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels in the rat. J Clin Invest (1987) 80:294–9 10.1172/JCI113072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sanchez-Criado JE, de Las Mulas JM, Bellido C, Navarro VM, Aguilar R, Garrido-Gracia JC, et al. Gonadotropin-secreting cells in ovariectomized rats treated with different oestrogen receptor ligands: a modulatory role for ERbeta in the gonadotrope? J Endocrinol (2006) 188:167–77 10.1677/joe.1.06377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Prendergast KA, Burger LL, Aylor KW, Haisenleder DJ, Dalkin AC, Marshall JC. Pituitary follistatin gene expression in female rats: evidence that inhibin regulates transcription. Biol Reprod (2004) 70:364–70 10.1095/biolreprod.103.021733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kaiser UB, Chin WW. Regulation of follistatin messenger ribonucleic acid levels in the rat pituitary. J Clin Invest (1993) 91:2523–31 10.1172/JCI116488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Baratta M, West LA, Turzillo AM, Nett TM. Activin modulates differential effects of estradiol on synthesis and secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone in ovine pituitary cells. Biol Reprod (2001) 64:714–9 10.1095/biolreprod64.2.714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Strahl BD, Huang HJ, Sebastian J, Ghosh BR, Miller WL. Transcriptional activation of the ovine follicle-stimulating hormone beta-subunit gene by gonadotropin-releasing hormone: involvement of two activating protein-1-binding sites and protein kinase C. Endocrinology (1998) 139:4455–65 10.1210/en.139.11.4455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Miller CD, Miller WL. Transcriptional repression of the ovine follicle-stimulating hormone-beta gene by 17 beta-estradiol. Endocrinology (1996) 137:3437–46 10.1210/en.137.8.3437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lagace L, Massicotte J, Labrie F. Acute stimulatory effects of progesterone on luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone release in rat anterior pituitary cells in culture. Endocrinology (1980) 106:684–9 10.1210/endo-106-3-684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Everett JW. Progesterone and estrogen in the experimental control of ovulation time and other features of the estrous cycle in the rat. Endocrinology (1948) 43:389–405 10.1210/endo-43-6-389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Urbanski HF, Pickle RL, Ramirez VD. Simultaneous measurement of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone in the orchidectomized rat. Endocrinology (1988) 123:413–9 10.1210/endo-123-1-413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shivers BD, Harlan RE, Morrell JI, Pfaff DW. Immunocytochemical localization of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone in male and female rat brains. Quantitative studies on the effect of gonadal steroids. Neuroendocrinology (1983) 36:1–12 10.1159/000123522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Toranzo D, Dupont E, Simard J, Labrie C, Couet J, Labrie F, et al. Regulation of pro-gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene expression by sex steroids in the brain of male and female rats. Mol Endocrinol (1989) 3:1748–56 10.1210/mend-3-11-1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lindzey J, Wetsel WC, Couse JF, Stoker T, Cooper R, Korach KS. Effects of castration and chronic steroid treatments on hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone content and pituitary gonadotropins in male wild-type and estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mice. Endocrinology (1998) 139:4092–101 10.1210/en.139.10.4092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wetsel WC, Negro-Vilar A. Testosterone selectively influences protein kinase-C-coupled secretion of proluteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-derived peptides. Endocrinology (1989) 125:538–47 10.1210/endo-125-1-538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Selmanoff M, Shu C, Petersen SL, Barraclough CA, Zoeller RT. Single cell levels of hypothalamic messenger ribonucleic acid encoding luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone in intact, castrated, and hyperprolactinemic male rats. Endocrinology (1991) 128:459–66 10.1210/endo-128-1-459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Roselli CE, Kelly MJ, Ronnekleiv OK. Testosterone regulates progonadotropin-releasing hormone levels in the preoptic area and basal hypothalamus of the male rat. Endocrinology (1990) 126:1080–6 10.1210/endo-126-2-1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Culler MD, Valenca MM, Merchenthaler I, Flerko B, Negro-Vilar A. Orchidectomy induces temporal and regional changes in the processing of the luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone prohormone in the rat brain. Endocrinology (1988) 122:1968–76 10.1210/endo-122-5-1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zanisi M, Celotti F, Ferraboschi P, Motta M. Testosterone metabolites do not participate in the control of hypothalamic LH-releasing hormone. J Endocrinol (1986) 109:291–6 10.1677/joe.0.1090291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Levine JE, Pau KY, Ramirez VD, Jackson GL. Simultaneous measurement of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone and luteinizing hormone release in unanesthetized, ovariectomized sheep. Endocrinology (1982) 111:1449–55 10.1210/endo-111-5-1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Jackson GL, Kuehl D, Rhim TJ. Testosterone inhibits gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse frequency in the male sheep. Biol Reprod (1991) 45:188–94 10.1095/biolreprod45.1.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Giri M, Kaufman JM. Effects of long-term orchidectomy on in vitro pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone release from the medial basal hypothalamus of the adult guinea pig. Endocrinology (1994) 134:1621–6 10.1210/en.134.4.1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Burger LL, Haisenleder DJ, Wotton GM, Aylor KW, Dalkin AC, Marshall JC. The regulation of FSHbeta transcription by gonadal steroids: testosterone and estradiol modulation of the activin intracellular signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab (2007) 293:E277–85 10.1152/ajpendo.00447.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gharib SD, Leung PC, Carroll RS, Chin WW. Androgens positively regulate follicle-stimulating hormone beta-subunit mRNA levels in rat pituitary cells. Mol Endocrinol (1990) 4:1620–6 10.1210/mend-4-11-1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ortmann O, Tomic M, Weiss JM, Diedrich K, Stojilkovic SS. Dual action of androgen on calcium signaling and luteinizing hormone secretion in pituitary gonadotrophs. Cell Calcium (1998) 24:223–31 10.1016/S0143-4160(98)90131-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kalra SP, Kalra PS. Neural regulation of luteinizing hormone secretion in the rat. Endocr Rev (1983) 4:311–51 10.1210/edrv-4-4-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Liang T, Brady EJ, Cheung A, Saperstein R. Inhibition of luteinizing hormone (LH)-releasing hormone-induced secretion of LH in rat anterior pituitary cell culture by testosterone without conversion to 5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone. Endocrinology (1984) 115:2311–7 10.1210/endo-115-6-2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Wierman ME, Gharib SD, LaRovere JM, Badger TM, Chin WW. Selective failure of androgens to regulate follicle stimulating hormone beta messenger ribonucleic acid levels in the male rat. Mol Endocrinol (1988) 2:492–8 10.1210/mend-2-6-492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kennedy J, Chappel S. Direct pituitary effects of testosterone and luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone upon follicle-stimulating hormone: analysis by radioimmuno and radioreceptor assay. Endocrinology (1985) 116:741–8 10.1210/endo-116-2-741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Winters SJ, Ishuizaka K, Kitahara S, Troen P, Attardi B, Ghooray D, et al. Effects of testosterone on gonadotropin subunit messenger ribonucleic acids in the presence or absence of gonadotropin releasing hormone. Endocrinology (1992) 130:726–34 10.1210/en.130.2.726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Inoue K, Kurosumi K. Mode of proliferation of gonadotrophic cells of the anterior pituitary after castration – immunocytochemical and autoradiographic studies. Arch Histol Jpn (1981) 44:71–85 10.1679/aohc1950.44.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Childs GV, Lloyd JM, Unabia G, Gharib SD, Wierman ME, Chin WW. Detection of luteinizing hormone beta messenger ribonucleic acid (RNA) in individual gonadotropes after castration: use of a new in situ hybridization method with a photobiotinylated complementary RNA probe. Mol Endocrinol (1987) 1:926–32 10.1210/mend-1-12-926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Hymer WC, Mastro A, Griswold E. DNA synthesis in the anterior pituitary of the male rat: effect of castration and photoperiod. Science (1970) 167:1629–31 10.1126/science.167.3925.1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Inoue K, Tanaka S, Kurosumi K. Mitotic activity of gonadotropes in the anterior pituitary of the castrated male rat. Cell Tissue Res (1985) 240:271–6 10.1007/BF00222334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Ishikawa H, Totsuka S. Histological and histometrical studies on the adeno-hypophyseal cells in castrated male rats, with special emphasis on a contradiction of classifying the gonadotroph and the thyrotroph. Endocrinol Jpn (1968) 15:457–79 10.1507/endocrj1954.15.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Duran-Pasten ML, Fiordelisio-Coll T, Hernandez-Cruz A. Castration-induced modifications of GnRH-elicited [Ca2+](i) signaling patterns in male mouse pituitary gonadotrophs in situ: studies in the acute pituitary slice preparation. Biol Reprod (2013) 88:38. 10.1095/biolreprod.112.103812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Arimura A, Shino M, de la Cruz KG, Rennels EG, Schally AV. Effect of active and passive immunization with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone on serum luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone levels and the ultrastructure of the pituitary gonadotrophs in castrated male rats. Endocrinology (1976) 99:291–303 10.1210/endo-99-1-291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Yoshimura F, Harumiya K. Electron microscopy of the anterior lobe of pituitary in normal and castrated rats. Endocrinol Jpn (1965) 12:119–52 10.1507/endocrj1954.12.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Console GM, Jurado SB, Rulli SB, Calandra RS, Gomez Dumm CL. Ultrastructural and quantitative immunohistochemical changes induced by nonsteroid antiandrogens on pituitary gonadotroph population of prepubertal male rats. Cells Tissues Organs (2001) 169:64–72 10.1159/000047862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Gomez-Dumm CL, Echave-Llanos JM. Further studies on the ultrastructure of the pars distalis of castrated male mice pituitary. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol (1973) 13:145–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Tixier-Vidal A, Tougard C, Kerdelhue B, Jutisz M. Light and electron microscopic studies on immunocytochemical localization of gonadotropic hormones in the rat pituitary gland with antisera against ovine FSH, LH, LHalpha, and LHbeta. Ann N Y Acad Sci (1975) 254:433–61 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb29193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Ibrahim SN, Moussa SM, Childs GV. Morphometric studies of rat anterior pituitary cells after gonadectomy: correlation of changes in gonadotropes with the serum levels of gonadotropins. Endocrinology (1986) 119:629–37 10.1210/endo-119-2-629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Tobin VA, Canny BJ. The regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone-induced calcium signals in male rat gonadotrophs by testosterone is mediated by dihydrotestosterone. Endocrinology (1998) 139:1038–45 10.1210/en.139.3.1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Tobin VA, Canny BJ. Testosterone regulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone-induced calcium signals in male rat gonadotrophs. Endocrinology (1996) 137:1299–305 10.1210/en.137.4.1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Clayton RN, Detta A, Naik SI, Young LS, Charlton HM. Gonadotrophin releasing hormone receptor regulation in relationship to gonadotrophin secretion. J Steroid Biochem (1985) 23:691–702 10.1016/S0022-4731(85)80004-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Sonntag WE, Forman LJ, Fiori JM, Hylka VW, Meites J. Decreased ability of old male rats to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) is not due to alterations in pituitary LH-releasing hormone receptors. Endocrinology (1984) 114:1657–64 10.1210/endo-114-5-1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Garcia A, Schiff M, Marshall JC. Regulation of pituitary gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors by pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone injections in male rats. Modulation by testosterone. J Clin Invest (1984) 74:920–8 10.1172/JCI111510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Weiss J, Guendner MJ, Halvorson LM, Jameson JL. Transcriptional activation of the follicle-stimulating hormone beta-subunit gene by activin. Endocrinology (1995) 136:1885–91 10.1210/en.136.5.1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Dalkin AC, Knight CD, Shupnik MA, Haisenleder DJ, Aloi J, Kirk SE, et al. Ovariectomy and inhibin immunoneutralization acutely increase follicle-stimulating hormone-beta messenger ribonucleic acid concentrations: evidence for a nontranscriptional mechanism. Endocrinology (1993) 132:1297–304 10.1210/en.132.3.1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Gregory SJ, Lacza CT, Detz AA, Xu S, Petrillo LA, Kaiser UB. Synergy between activin A and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in transcriptional activation of the rat follicle-stimulating hormone-beta gene. Mol Endocrinol (2005) 19:237–54 10.1210/me.2003-0473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]