Abstract

Advanced heart failure (HF) is a disease process that carries a high burden of symptoms, suffering, and death. Palliative care can complement traditional care to improve symptom amelioration, patient-caregiver communication, emotional support, and medical decision making. Despite a growing body of evidence supporting the integration of palliative care into the overall care of patients with HF and some recent evidence of increased use, palliative therapies remain underused in the treatment of advanced HF. Review of the literature reveals that although barriers to integrating palliative care are not fully understood, difficult prognostication combined with caregiver inexperience with end-of-life issues specific to advanced HF is likely to contribute. In this review, we have outlined the general need for palliative care in advanced HF, detailed how palliative measures can be integrated into the care of those having this disease, and explored end-of-life issues specific to these patients.

Keywords: Advanced heart failure, Palliative care, Hospice, End-of-life

Advanced heart failure (HF), defined by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association as stage D, is the end of the HF disease spectrum in which symptoms are present at rest despite optimal medical management.1 Because standard oral therapies no longer offer adequate symptom relief, advanced HF requires specialized interventions or a fundamental change in therapeutic approach. Of the nearly 6 million patients in the United States living with HF, approximately 1% will reach advanced-stage HF and die of progressive pump failure.2 This number is likely to increase as the population ages and improvements in medical therapy prolong disease progression.

As HF enters advanced stage, physical and spiritual sufferings increase at the same time that patients face a growing risk for death. In addition, HF is associated with advanced age and a high burden of comorbidity, creating a complex setting in which the care of these patients must occur. Therefore, palliative care is needed in a variety of forms to complement traditional therapies and address the entire process of care for these complex patients. Despite an apparent need for integration of palliative interventions into the care of patients with advanced HF, there continues to be an underutilization of these resources by many health care providers. Prior reviews of this topic have identified gaps in integration of these services into the care of patients with advanced HF and have called for further investigation into palliative therapies specific to patients with HF.3–5 In this article, we provide an updated review of the why, what, when, and how of palliative care in advanced HF and discuss factors contributing to underutilization.

Why: defining the need for palliative care in advanced HF

By its nature, advanced HF is highly morbid, with significant symptoms and functional limitation. A study of veterans with symptomatic HF demonstrated that 63% had low energy levels, 58% experienced shortness of breath, and 55% had pain.6 Patients with advanced HF have been shown to experience a greater number of physical complaints, higher depression scores, and lower spiritual well-being than patients with metastatic cancer.7 Furthermore, the amount of suffering that occurs in advanced HF—and remains inadequately treated—is likely underestimated by many health care providers.8 Because of several epidemiological and therapeutic changes, advanced HF will include an increasingly older population and with greater comorbidity, exacerbating the symptoms of HF and complicating management. Without a focused approach and adequate resources, health care professionals who care for patients with advanced HF may find it increasingly difficult to fully address these symptoms while also managing patients’ ongoing medical problems.

Advanced HF is also highly lethal, with life expectancy of less than 1 year for most patients once they enter stage D HF.9 In addition, as patients with HF progress into advanced stages of disease, they become more likely to die of pump failure in comparison with sudden cardiac death. This shift in the mode of death is accompanied by greater symptoms, progressive loss of autonomy, and the need for complex decision making by patients, families, and providers.

Because of its high morbidity and mortality, advanced HF is accompanied by a unique need for communication between patients, families, and health care providers. Yet, this does not appear to be happening adequately. Patients and their families report that they would like to have indepth discussions regarding both prognosis and end-of-life issues but feel that they are not given full disclosure on prognosis and severity of illness.10 The perceived lack of open communication is felt to contribute directly to unmet care needs and may impart a negative impact on quality of life. Furthermore, this may adversely affect patients’ ability to appropriately make the transition to end-of-life care and hospice. This is particularly important in the setting of advanced HF, in which many patients have been shown to have poorly calibrated expectations of their longevity. A survey of patients enrolled in an academic HF clinic demonstrated significant discordance between patient predicted life expectancy vs actual and model-predicted life expectancy, on average overestimating longevity by 40%.11 Hence, it appears that there are significant gaps in what patients perceive to be their prognosis, unanswered needs for open communication, and inadequate understanding about what physicians ultimately are able to provide.

Incongruity between patient expectations and health care provider communication increases the likelihood that patients will end their lives in a way that is not consistent with their preferences for a “good death.”12 Studies of patient preferences have noted that 90% people would prefer to die at home, as opposed to a hospital or nursing home.13 Yet, among patients with HF and decreased ejection fraction, 58% die in the hospital vs only 29% at home.14

In addition to failing to meet patient needs, end-of-life care, as currently delivered, is exceedingly costly. The estimated combined direct and indirect cost of caring for HF in the United States is in excess of $39 billion, a large fraction of which is devoted to end-of-life care.2 The Dartmouth Group has estimated that the 2-year end-of-life cost for Medicare beneficiaries with serious chronic illness, such as HF, is anywhere between $53,432 and $105,000.15 In addition, they demonstrated that intensity of care and frequency of hospitalizations tend to increase significantly at the end of life and are negatively correlated with patient satisfaction.

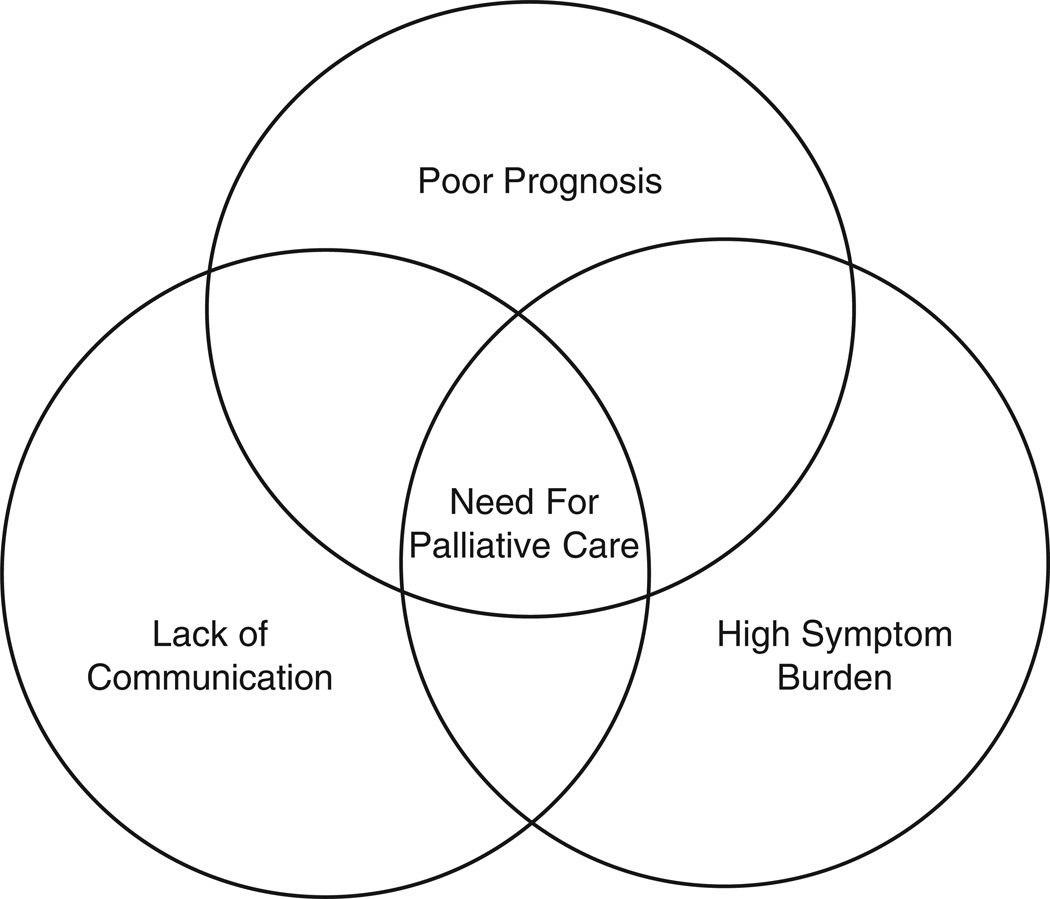

This high symptom burden, poor prognosis, and inadequate communication all combine in advanced HF to create a particularly complex care situation at high risk for undermining patient quality of life and autonomy (Fig 1). Palliative care services have the potential to address all of these needs, as they provide a focus on symptom control, a more holistic approach to end of life, and improved communication. These targeted services have the potential to improve patient and family satisfaction and lead to more efficient use of resources, throughout the disease process and especially in the last days of life.

Fig 1.

The perfect storm of factors in advanced HF that converge to create a true need for palliative interventions in the care of those with advanced HF.

What: defining palliative care and hospice services and their role

Although the terms hospice and palliative care are sometimes used interchangeably in colloquial use, the term hospice captures a particular type of palliative care. Although hospice has specific legal, administrative, and financial definitions, palliative care is a general term that encompasses a wide range of activities. The word “palliative” is derived from the Latin word palliare, which means to cloak. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) defines palliative care as treatment for the relief of pain and other uncomfortable symptoms through the appropriate coordination of all aspects of care needed to maximize personal comfort and relieve distress.16 The World Health Organization (WHO) provides an expanded definition, which includes a supportive role as well as a role in communicating and anticipating end-of-life needs.17 Thus, palliative care measures are those in which the principle aim is to improve symptoms and quality of life, in contrast to interventions that are primarily meant to be curative or prolong life. In the treatment of HF, many traditional therapies are aimed at treating the physiologic causes of symptoms; and therefore, substantial overlap exists between palliative and traditional therapies for HF. Palliative interventions can be integrated at any point in the care of those afflicted with serious illness and can be used to complement traditional medical management.

A hospice uses an interdisciplinary approach to deliver medical, social, physical, emotional, and spiritual services through the use of a broad spectrum of caregivers within a defined time frame at the end of life.16 Hospice care derives its origin from religiously affiliated institutions, which first appeared in the United Kingdom in the 1800s.18 These institutions were originally devoted to ameliorating the suffering of dying patients. The first hospice was established in the United States in New Haven in the 1970s, and the number of hospice institutions has since grown substantially. Hospice care was first recognized by Medicare in 1982 but was initially geared only toward the care of patients with cancer. This was because cancer was the only terminal illness, at that time, which was perceived to have a defined and predictable disease course. The diagnoses treated in hospices began to expand after AIDS brought to the forefront the notion that other terminal illnesses could be treated under the umbrella of hospice. Currently, any terminal illness, defined as having less than 6-month predicted survival, qualifies for hospice. Because Medicare is the primary source of funding for hospice services in the United States, the CMS definitions of hospice services are exceedingly important. The CMS definition of hospice is “care that allows the terminally ill patient to remain at home as long as possible by providing support to the patient and family and keeping the patient as comfortable as possible while maintaining his or her dignity and quality of life.”16 Furthermore, CMS states that hospice care provides palliative care rather than traditional medical care and curative treatment, although the lines between curative and palliative therapies in advanced HF are often not so distinct. Hospice is the only Medicare benefit that includes pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, and 24-hour access to medical care outside the inpatient hospital environment. Specific palliative measures and hospice services in HF will be discussed in subsequent sections of this article.

When: timing and integration of palliative care

Palliative care is recommended by all of the major governing bodies of cardiology: the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2009 guidelines designate palliative care measures as a level 1C guideline1; the European Society of Cardiology 2008 guidelines recommend its use with level 1C19; and the Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) 2010 guidelines recommend these measures with level C evidence.20 Although there are strong recommendations in favor of general use of these practices, the guidelines lack specifics on the exact nature and timing of these services. A consensus statement from the HFSA on “Palliative and Supportive Care in Advanced Heart Failure” identifies these gaps in specific practice recommendation.21 Thus, many of the details of the timing of integration of these services are left to the discretion of the practitioner.

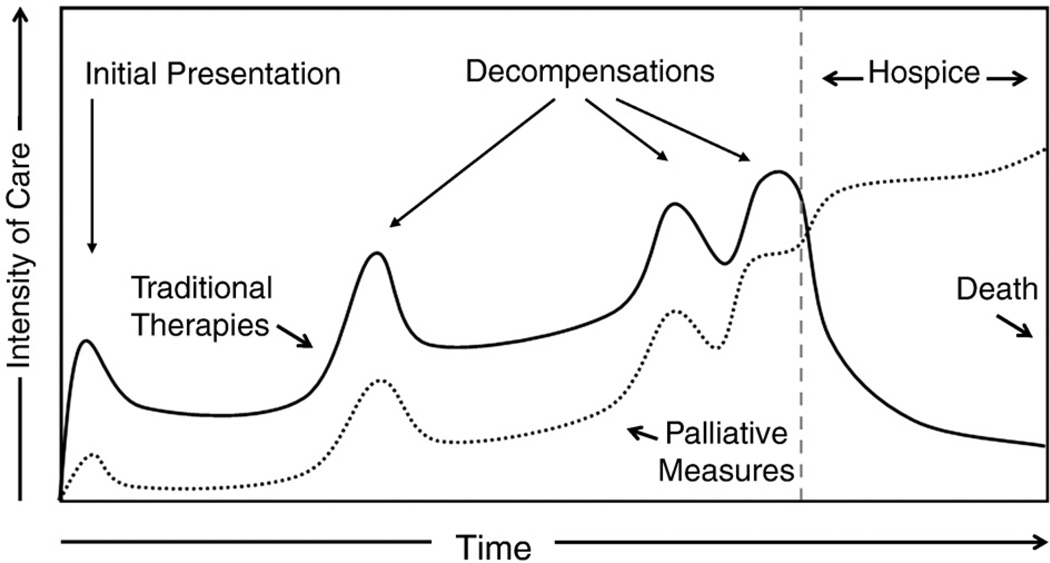

Unlike the relatively linear decline seen in terminal cancer, HF is marked by an undulating and less predictable course. This makes prognostication difficult and, consequently, can make the decision of when to integrate certain palliative services quite challenging. Multiple public health advisory organizations have begun to recognize the importance of early use of palliative care. Specifically, the WHO has modified its stance on palliative care to state that these services should be offered “early in the course of the illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life.”17 The WHO recommendations are intended for all “life-threatening” illnesses, including advanced HF. To that end, therapies to ameliorate pain, dyspnea, and depression as well as other symptoms that may be present should be integrated throughout the disease process as symptoms present themselves (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Intensity of care throughout the time course of the disease spectrum of HF. Palliative therapies should be integrated throughout, intensified as the patient experiences worsening HF, and escalated when the patient transitions to hospice. Important to note is that some traditional therapies may remain even after the patient is enrolled in hospice. Adapted from Lanken et al.22

Although it is apparent that some aspects of palliative care should be considered early in the disease course of HF, the appropriate timing of end-of-life discussions and referral for hospice care is more problematic because of the variable nature of disease progression. Because the qualification for hospice care benefits requires the patient to have a life expectancy of less than 6 months and designates an important transition in the goals of care, it is important to be able to identify patients who are not transplant or mechanical circulatory support candidates within this life expectancy window.16

Historically, prognostic models have been relied upon to help aid in prediction of survival. The Seattle Heart Failure Model, which was derived from randomized trial populations and has been validated in several settings, has gained popularity and is available for use online.23 This model has been validated in a wide variety of HF populations to accurately predict 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival. However, it is cumbersome, encompassing 14 continuous variables and 10 categorical variables, and may underestimate risk in some patients with advanced HF.24 In an attempt to simplify risk calculation, more parsimonious models have been developed. Huynh et al25 have worked to develop 7-item and 4-item dichotomous risk scores to calculate 6-month life expectancy in patients with HF. The 7-item score— which predicts a high likelihood of 6-month mortality if 4 or more risk factors are present—includes age greater than 75 years, coronary artery disease, dementia, serum urea nitrogen greater than or equal to 30 mg/dL, systolic blood pressure less than 120 mm Hg, peripheral arterial disease, and serum sodium less than 135 mEq/L.25 The 4-item risk score omits age, coronary disease, and dementia from its calculation while retaining similar performance.26 Others have advocated for an eventdriven approach to trigger discussions and decisions about palliative care, such as recurrent hospitalization or implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) discharge; but such an approach has not been formally studied. Regardless of the method used, the health care providers treating patients with advanced HF should continuously reassess the likely survival of their patients to be able to anticipate the need for conversations about advanced therapies and/or end-of-life decisions and implementation of specific palliative care interventions.

The ability to identify patients who are appropriate for transition to end-of-life care is central to patient and family satisfaction around the dying process. Unfortunately, interventions to provide health care practitioners with objective data about prognosis have not been shown to improve communication or end-of-life care decisions, at least in the intensive care setting.27 Simply having prognostic information available is not sufficient; health care providers must have the initiative and experience to act on this information, using it to guide discussions with the patient and inform medical decision making. Unless advanced-care planning takes place, most patients with advanced HF will meet their demise in an inpatient hospital setting.14 Teno et al28 have noted that “many people dying in institutions have unmet needs for symptom amelioration, physician communication, emotional support, and being treated with respect.” Their research further notes that families of those dying with hospice services were more likely to rate their dying experience as favorable or “excellent” as compared with those who died in an institution or at home with only home health services. In addition to location of death, timing of referral to hospice is an important consideration when caring for patients who are at the end of their lives. Perception of appropriate timing of hospice care, not total length of stay, correlates well with family satisfaction, whereas the perception of being referred “too late” was associated with greater dissatisfaction and unmet needs.29

How: achieving symptom palliation in and transitioning to end-of-life care

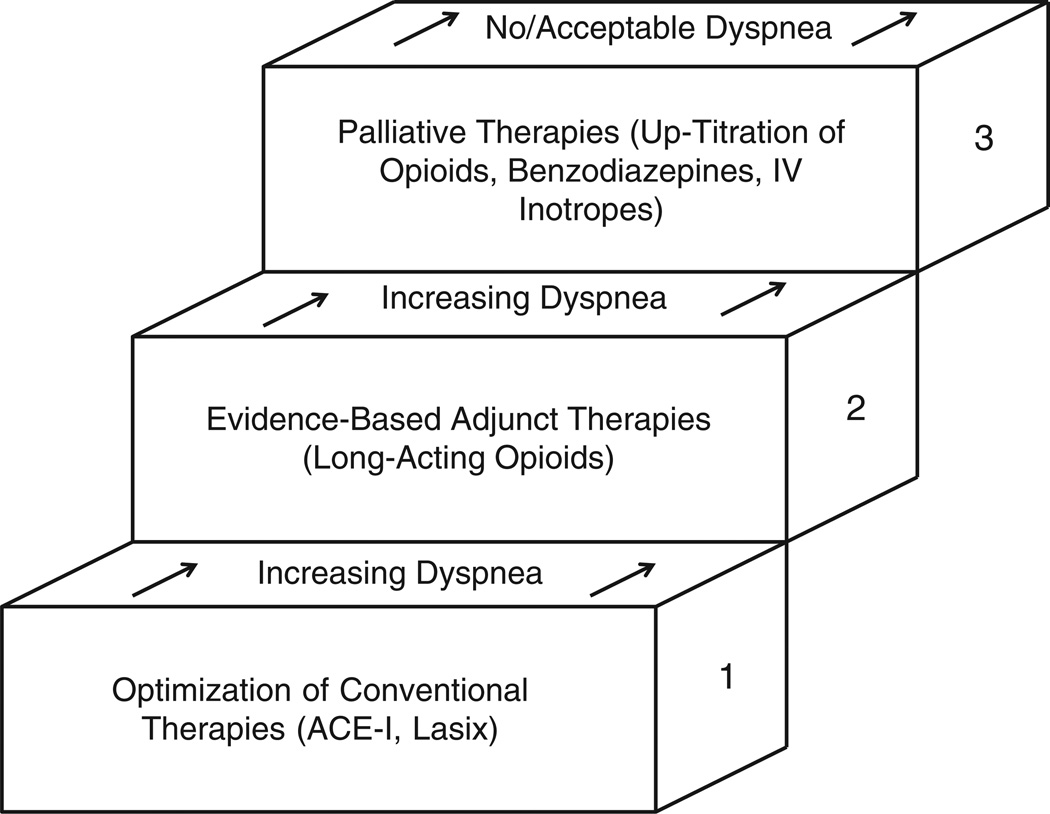

Advanced HF is a disease process that is highly symptomatic. The most prevalent complaints are dyspnea, depression, pain, edema, and fatigue.30,31 Other sources of suffering that have been identified include isolation, difficulty navigating the health care system, and the feeling of uncertainty surrounding prognosis and longevity.32 Because many of the symptomatic complaints expressed by patients with advanced HF are the result of the underlying pathophysiology of advanced HF, evidence-based HF therapies, as the patient tolerates, form the foundation of care. In addition, palliative approaches also recognize that most patients with advanced HF are older and that HF is often the result of other diseases such as diabetes and vascular disease. As such, these patients often have other medical comorbidities, which contribute to their symptoms and suffering. It is important to consider all sources of suffering and address other treatable issues, which may be contributing to the spectrum of suffering. Therefore, beyond continuing a medical regimen appropriate for advanced HF, adjuvant therapies for symptom management should be considered on an individual basis. Medications and nonpharmacologic therapies are added in a stepwise fashion to target specific symptoms (Fig 3). Management of the 3 most common sources of suffering in advanced HF—dyspnea, depression, and pain—will be discussed below; but it is important to recognize that other sources of suffering may be present and warrant individualized attention.

Fig 3.

Palliative therapies should be added in a stepwise fashion to traditional therapies and optical medical management of HF. Adapted from Rocker et al.33

Dyspnea

Dyspnea is a common symptom experienced in advanced HF. The mainstay of therapy is diuresis and vasodilation to decrease pulmonary congestion. These agents include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, long-acting nitrates, hydralazine, and diuretics.1,19,20 However, patients with advanced HF may have hypotension, renal dysfunction, or other factors, which may limit the effective use of these therapies to diminish dyspnea. In the circumstance of refractory dyspnea, low-dose opiates are the mainstay of therapy.34 An additional benefit of opiates is that they may aid in the control of pain symptoms, which often overlap with symptoms of dyspnea. Other therapies have been tested for control of breathlessness but have been found to be inferior to opiates. A recent Cochrane review of benzodiazepines for the treatment of dyspnea in patients with noncancer illnesses demonstrated that benzodiazepines may be used for the treatment of dyspnea in patients enrolled in palliative care but that they should only be used as second-line agents.35 It is a common misconception among health care providers that oxygen therapy will reduce the sensation of dyspnea in the nonhypoxic patient. Several studies, including a Cochrane review, have demonstrated that oxygen is only beneficial in reducing dyspnea in hypoxic patients and has no role in the nonhypoxic patient.35,36

Depression

Depression is highly prevalent among patients with advanced HF. Approximately 1 in 5 patients with HF meets criteria for major depressive disorder, and a greater percentage report depressive symptoms.37 Even when adjusting for covariates, it has been found that patients with worsening depression have worsened clinical outcomes. In addition, depressive symptoms are highly correlated with decreased quality of life and increased pain. Despite the obvious need to treat depression in patients with HF, there is limited high-quality evidence to guide therapy. To date, the only randomized control trial with specific pharmacologic intervention for the treatment of depression in HF is the sertraline against depression and heart disease in chronic heart failure (SADHART-CHF) study.38 This study treated patients with symptomatic HF with either sertraline or placebo for 12 weeks. Treatment with sertraline did not show a benefit in depression scores. Although SADHART-CHF did not meet its primary end point, which may have been attributable to short duration of therapy or lower-than-average dosing, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are still considered first-line therapy for depression in patients with advanced HF. This is due to extrapolation from studies in other settings and a lack of other proven options. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors have not been studied in advanced HF. Tricyclic antidepressants have a limited role in HF, as they can cause QTc prolongation and may cause anticholinergic effects such as dry mouth and orthostatic hypotension, which are unfavorable side effects in the setting of advanced HF.

Pain

The general sensation of pain is a shared complaint of many patients with advanced HF, regardless of stage. A recent cross-sectional study performed in 2009 of 300 patients with HF demonstrated that 67% of all patients with HF reported some form of pain. The prevalence of pain, however, increases with New York Heart Association functional class, with 69% of class III patients reporting pain and an overwhelming 89% of class IV patients reporting pain.8 Heart failure is a disease process that primarily affects the elderly, with a median patient age of 75 years. Thus, this group of patients often carries a large burden of medical comorbidities, which may contribute to or individually cause pain. Although pain syndromes in HF are not well described, it is thought that both HF itself and underlying medical comorbidities contribute to the experience of pain. The Pain Assessment, Incidence & Nature in Heart Failure (PAIN-HF) study has identified medical comorbidities most highly associated with pain in patients with advanced HF, including degenerative joint disease, chronic back pain, anxiety, and depression.39 Others have confirmed that pain increases with greater psychosocial stressors and medical comorbidities in patients with HF, suggesting that this is a multifactorial problem.6

Although there is a high prevalence of pain among the advanced HF population, usage of opiates appears to be disproportionately low among these patients. A recent study demonstrated that the usage of opiates was only 22% among patients with advanced HF compared with nearly 50% among patients with cancer.40 The reasons for this disparity are unclear; however, this problem may have its root in the fundamental underestimation of pain in advanced HF by health care providers.

The specific management of pain in advanced HF has been little studied with randomized control trials. Given its prevalence within the advanced HF population, with most patients experiencing pain, the degree of pain should be frequently assessed by either or both the primary care provider and the cardiologist. Special attention may need to be paid to sources of pain from comorbid medical conditions, but the general principles of pain management apply to patients with advanced HF. Opiates are the mainstay of therapy and should be up-titrated as is usual practice. However, special caution should be given to methadone, which can prolong QT; thus, the electrocardiogram should be periodically followed up for the duration of methadone therapy, or alternative agents should be used.41 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided, if possible, in all patients with HF because of their propensity to cause sodium and fluid retention, which may exacerbate HF.42

End-of-life issues in advanced HF

Advanced-care planning

Once it has been determined that a patient with advanced HF who is failing oral therapies is not a transplantation candidate or mechanical circulatory support candidate and that they will make the transition to end-of-life care, a series of critical discussions between the patient and health care provider should ensue. Health care provider guidance through clear and open communication is of the utmost importance. Before initiating end-of-life conversations, the health care provider must achieve 2 goals. First, the health care provider must carry out a frank conversation with the patient regarding their prognosis, specifically addressing the inherent uncertainty and the varying possibilities of disease trajectory, including the possibility of sudden cardiac death. Although this direct and open approach is not universally endorsed by all cultures, American principals of autonomy and selfdetermination require this type of conversation to build the foundation for subsequent decision making by the patient. After the range of anticipated prognosis has been adequately discussed, the health care provider can begin to assess the ultimate goals of the patient and their family regarding medical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs.43 It is important to account for wide variations in preference among patients when discussing end of life. Although certain aspects of care, including pain control and perceived autonomy are important, other psychosocial aspects of dying may be considered equally important to patients. Underappreciated aspects of a good death from a patient perspective include being at peace with God, having family present, and being mentally aware.44 Being familiar with a patient’s individual preferences can help the health care provider to guide the patient when making difficult decisions.

There are 2 primary types of decision making that should occur in preparation for end-of-life care: decision making for emergency situations (ie, respiratory failure or cardiac arrest) and decision making for clinical situations that can be reasonably anticipated.45 Preferences regarding do-not-resuscitate (DNR) status vary widely among patient populations with different end-stage diseases; notably, patients with HF are much more likely than patients with cancer to desire cardiopulmonary resuscitation, with only 23% of patients with HF stating that they do not want resuscitation.46 In addition, it has been found that patients with HF are not likely to change their preferences, even after hospitalizations for decompensation47; and some studies suggest that patient preferences are solidified very early in the disease process.48 Thus, it is appropriate to broach these issues early in the disease course. Although there are apparent barriers to changing code status, it is recommended that the health care provider attempt to address this topic at frequent intervals in patients with advanced HF.49

Planning for nonemergent end-of-life issues can pose a significant challenge for health care providers treating patients with advanced HF. This is related, in part, to advances in medical technology and devices used in the treatment of advanced HF. Devices, such as left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) and ICDs, may pose their own management dilemmas for the patient and the health care provider at the end of life.

Intravenous inotropes

Continuous intravenous inotropic therapy can be considered for end-of-life symptom palliation in advanced HF. The HFSA recommends this therapy for palliation in patients who have refractory symptoms; however, it is advised that these therapies only be undertaken with the consideration that they may increase the risk of sudden cardiac death and may potentially accelerate ventricular remodeling.20 There is conflicting evidence regarding the efficacy of symptom amelioration of intravenous inotropes. A meta-analysis found that not only did patients treated with intravenous inotropes have no significant improvement in symptoms but also that there was an increased risk of death in those treated with dobutamine.50 This increased risk of death, particularly due to sudden cardiac death, is supported by multiple other studies.51

Although there is a risk of sudden cardiac death, this may be acceptable to patients with advanced HF. A recent study of patient preferences in patients with advanced HF demonstrated that there are 2 relatively distinct groups of patients, those who would prefer a significantly shortened life with fewer symptoms and those who would prefer longevity regardless of symptoms.48 Therefore, patient preferences should dictate considerations of continuous intravenous inotropic therapy.

The cost-effectiveness of continuous inotrope therapy has been investigated in a cohort of 331 Medicare beneficiaries. This cohort was evaluated both before and after initiation of intravenous inotrope therapy. Hospital admissions were decreased throughout the study, and reimbursement rates were decreased in the first 6 months. However, the expense of the infusions was greater than the savings from decreased hospitalizations if the infusions were continued for longer than 60 days.52

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators

There is a large body of evidence supporting the use of ICDs for the prevention, both primary and secondary, of death from fatal ventricular arrhythmias. The number of devices implanted in the United States is approximately 10,000 devices placed per month and continues to increase.53 Implantable cardioverter defibrillators prevent sudden cardiac death. However, unlike many life-saving therapies for patients with chronic systolic HF (eg, neurohormonal antagonist medications and cardiac resynchronization therapy), ICDs do not improve symptoms and can create an additional burden on patients related to procedural complications and inappropriate discharges. Therefore, when a patient approaches the end of life due to progressive pump failure, ICD implantation is not indicated.1,20 Device deactivation should be a decision reached through collaboration between the patient and health care provider in an effort to avoid preventable suffering. It should be discussed before implantation and, as the end of life nears, from either cardiovascular causes or noncardiac causes, such as terminal cancer.54 However, data indicate that health care providers are failing to initiate these conversations with their patients with advanced HF. A recent survey found that only 1 in 4 next of kin reported that a physician had discussed device deactivation with their deceased family member before death.55 In a nationwide survey including 600 cardiologists, 60% of the physicians in their cohort had undertaken less than 2 conversations with patients and/or families about deactivation of ICDs.56 Concordant with those findings, a national survey of hospices found that less than 10% of hospices have a policy regarding deactivation of ICDs and that greater than 50% of hospices had at least 1 patient who had been shocked within the last year.57 To avoid inappropriate device discharge and suffering, discussion of device deactivated should occur when patients with advanced HF have a change in either clinical status or transition their goals from treatment to comfort.54

Mechanical circulatory support

Left ventricular assist devices were originally developed to act as a bridge to cardiac transplantation; however, they are now also being used increasingly as destination therapy in those who are not transplant candidates.58 The average life span of a patient post-LVAD placement has been increasing over time,59 but morbidity and mortality remain relatively high. Estimated actuarial survival in the HeartMate II destination therapy trial was 58% at 2 years.60 With improvements in medical technology and associated outcomes, patients with LVADs may not only be susceptible to death from cardiovascular causes but also to other life-limiting disease as well.61 As such, many patients with LVADs will subsequently embark on the decision-making process regarding discontinuation of LVAD therapy. Unlike ICDs, which can be deactivated without immediate effect, LVAD discontinuation can result in rapid decompensation and expedite death, particularly with valveless continuous flow devices. This clinical scenario has been likened to withdrawal of endotrachial intubation and ventilatory support, although LVAD patients are more likely to be awake and alert at the time of decision to discontinue support. Despite the perception that LVADs may impose special ethical dilemmas,62 the Patient Self Determination Act still broadly applies, giving the patient or their surrogate decision maker full autonomy to withdrawal support. In a recent small study of characteristics of patients electing to discontinue mechanical support, the most common triggers for discontinuation included infection/sepsis, stroke, cancer, renal failure, and impending pump failure.61 This study also documented that the average time to death after device deactivation was around 20 minutes, indicating that a careful plan for comfort and support after withdrawal of mechanical circulatory support should be in place well before the device is discontinued. Although there are no specific recommendations to direct when these therapies should be discontinued, it appears that declining quality of life or signs of other organ system failure should trigger serious discussions about device discontinuation. Just as is recommended with ICDs, potential scenarios around deactivation should be discussed before implantation.

Underutilization of palliative services and hospice in advanced HF

Despite the clear need for palliative services and specialized end-of-life care in advanced HF, multiple authors have noted that there is a dearth of use of these services by practitioners caring for patients with advanced HF.5 There is a lingering disparity between the usage of hospice and palliative services in the advanced HF population compared with the cancer population. In 2006, it was estimated that 11% of patients who died of advanced HF were enrolled in hospice programs.63 Reasons for underutilization have not been fully elucidated; however, the topic is actively being investigated. Proposed barriers to palliative care and hospice care in the advanced HF population include historical patterns of care, uncertain prognosis/disease course, increasing number of available therapies, lack of clinical evidence to support palliative care and hospice care, and inadequate training.64 Other authors have suggested that lack of clear communication from health care providers, which ultimately appears to stem from uncertainty surrounding prognosis, could also be contributing to the lack of referral to palliative care and hospice.10 It has been noted that physician discussion of hospice was strongly associated with subsequent enrollment in hospice, but this occurred in only 7% of patients with HF compared with 46% of patients with cancer.65 The onus appears to be on the health care provider, as patients are unlikely to access these services without being advised to by their health care providers. Encouraging, however, are data that show that there has been an apparent increase in use over the past decade. Medicare beneficiary data from patients with the specific diagnosis of HF from 2000 to 2007 show a significant increase in hospice services, with nearly 40% these beneficiaries using hospice services in the most recent years evaluated.66 Similar trends have been seen in Canada.67 Thus, it seems that, as health care providers become more experienced with these issues, access to and appropriate use of hospice and palliative care may continue to improve.

Conclusions

Advanced HF imparts high rates of morbidity and mortality. There is a great need for palliation of physical and emotional suffering throughout the disease process. Communication to address sources of discomfort and to ensure adequate patient understanding of their disease process and prognosis is integral to the care of these patients. Improved use of palliative measures may improve patient comfort and satisfaction with the death and dying process. Although there has been a great deal of research in palliative medicine, there are very few studies that are specific to symptom amelioration of patients with HF. Investigation into modalities of palliation specific to HF will be required in the future to better care for these patients.

As patients with HF reach the need for end-of-life care, specialized interventions and communication may be required. Hospice care is designed to meet the needs of patients with HF in this final phase of their lives; and although rates of hospice access are increasing among this population, many patients still do not achieve access to this care. Increased awareness appears to be leading to higher rates of use of these services; however, there are still significant strides to be made.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carolyn Cassin, MPA, President of the National Hospice Work Group.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- HF

heart failure

- HFSA

Heart Failure Society of America

- ICD

implantable cardioverter defibrillator

- LVAD

left ventricular assist device

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Statement of Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1–e90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(4):e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pantilat SZ, Steimle AE. Palliative care for patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2004;291:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodlin SJ. Palliative care in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adler ED, Goldfinger JZ, Kalman J, et al. Palliative care in the treatment of advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2009;120:2597–2606. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.869123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goebel JR, Doering LV, Shugarman LR, et al. Heart failure: the hidden problem of pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:698–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekelman DB, Rumsfeld JS, Havranek EP, et al. Symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well-being: a comparison of heart failure and advanced cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:592–598. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0931-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evangelista LS, Sackett E, Dracup K. Pain and heart failure: unrecognized and untreated. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;8:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolinsky FD, Smith DM, Stump TE, et al. The sequelae of hospitalization for congestive heart failure among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:558–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb03087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harding R, Selman L, Beynon T, et al. Meeting the communication and information needs of chronic heart failure patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen LA, Yager JE, Funk MJ, et al. Discordance between patient-predicted and model-predicted life expectancy among ambulatory patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2008;299:2533–2542. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.21.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 362:1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJ. Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:287–300. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olshansky B, Wood F, Hellkamp AS, et al. Where patients with mild to moderate heart failure die: results from the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) Am Heart J. 2007;153:1089–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice: The Dartmouth Atlas. [Accessed November 30, 2010]; www.dartmouthatlas.org.

- 16.Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: 42 CFR Part 418: Medicare and Medicaid programs: hospice conditions of participation; Final Rule. Fed Regist. 2008;73(109):32088–32220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization: WHO definition of palliative care. [Accessed November 30, 2010]; www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/.

- 18.Clark D. From margins to centre: a review of the history of palliative care in cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:430–438. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2388–2442. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindenfeld J, Albert NM, Boehmer JP, et al. HFSA 2010 Comprehensive heart failure practice guideline. J Card Fail. 2010;16:e1–e194. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodlin SJ, Hauptman PJ, Arnold R, et al. Consensus statement: palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:912–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, et al. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1424–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorodeski EZ, Chu EC, Chow CH, et al. Application of the Seattle Heart Failure Model in ambulatory patients presented to an advanced heart failure therapeutics committee. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:706–714. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.944280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huynh BC, Rovner A, Rich MW. Long-term survival in elderly patients hospitalized for heart failure: 14-year follow-up from a prospective randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1892–1898. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huynh BC, Rovner A, Rich MW. Identification of older patients with heart failure who may be candidates for hospice care: development of a simple four-item risk score. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1111–1115. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients The study to understand prognoses. preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teno JM, Shu JE, Casarett D, et al. Timing of referral to hospice and quality of care: length of stay and bereaved family members’ perceptions of the timing of hospice referral. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benedict CR, Weiner DH, Johnstone DE, et al. Comparative neurohormonal responses in patients with preserved and impaired left ventricular ejection fraction: results of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) Registry. The SOLVD Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:146A–153A. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90480-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings JA, et al. Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hopp FP, Thornton N, Martin L. The lived experience of heart failure at the end of life: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Work. 2010;35:109–117. doi: 10.1093/hsw/35.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rocker G, Horton R, Currow D, et al. Palliation of dyspnoea in advanced COPD: revisiting a role for opioids. Thorax. 2009;64:910–915. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.116699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Frith P, et al. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled crossover trial of sustained release morphine for the management of refractory dyspnoea. BMJ. 2003;327:523–528. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon ST, Higginson IJ, Booth S, et al. Benzodiazepines for the relief of breathlessness in advanced malignant and non-malignant diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007354.pub2. CD007354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clemens KE, Quednau I, Klaschik E. Use of oxygen and opioids in the palliation of dyspnoea in hypoxic and non-hypoxic palliative care patients: a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:367–377. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, et al. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Connor CM, Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Safety and efficacy of sertraline for depression in patients with heart failure: results of the SADHART-CHF (Sertraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goodlin SJ, Wingate S, Houser JL, et al. How painful is advanced heart failure? Results from PAIN-HF. J Card Fail. 2008;14(6S):S106. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Stedman M, et al. Hospice, opiates, and acute care service use among the elderly before death from heart failure or cancer. Am Heart J. 2010;160:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krantz MJ, Martin J, Stimmel B, et al. QTc interval screening in methadone treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:387–395. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Page J, Henry D. Consumption of NSAIDs and the development of congestive heart failure in elderly patients: an underrecognized public health problem. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:777–784. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quill TE. Perspectives on care at the close of lifeInitiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients: addressing the “elephant in the room.”. JAMA. 2000;284:2502–2507. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weissman DE. Decision making at a time of crisis near the end of life. JAMA. 2004;292:1738–1743. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krumholz HM, Phillips RS, Hamel MB, et al. Resuscitation preferences among patients with severe congestive heart failure: results from the SUPPORT project. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Circulation. 1998;98:648–655. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.7.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevenson LW, Hellkamp AS, Leier CV, et al. Changing preferences for survival after hospitalization with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1702–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacIver J, Rao V, Delgado DH, et al. Choices: a study of preferences for end-of-life treatments in patients with advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1002–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldfinger JZ, Adler ED. End-of-life options for patients with advanced heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2010;7:140–147. doi: 10.1007/s11897-010-0017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thackray S, Easthaugh J, Freemantle N, et al. The effectiveness and relative effectiveness of intravenous inotropic drugs acting through the adrenergic pathway in patients with heart failure—a metaregression analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4:515–529. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oliva F, Latini R, Politi A, et al. Intermittent 6-month low-dose dobutamine infusion in severe heart failure: DICE multicenter trial. Am Heart J. 1999;138:247–253. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hauptman PJ, Mikolajczak P, George A, et al. Chronic inotropic therapy in end-stage heart failure. Am Heart J. 2006;152:1096. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.08.003. e1-1096.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammill SC, Kremers MS, Stevenson LW, et al. Review of the Registry’s second year, data collected, and plans to add lead and pediatric ICD procedures. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1359–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Padeletti L, Arnar DO, Boncinelli L, et al. EHRA Expert Consensus Statement on the management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. Europace. 2010;12:1480–1489. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kelley AS, Reid MC, Miller DH, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator deactivation at the end of life: a physician survey. Am Heart J. 2009;157:702–708. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.12.011. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hauptman PJ, Swindle J, Hussain Z, et al. Physician attitudes toward end-stage heart failure: a national survey. Am J Med. 2008;121:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldstein N, Carlson M, Livote E, et al. Brief communication: management of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in hospice: a nationwide survey. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:296–299. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Slaughter MS, Pagani FD, Rogers JG, et al. Clinical management of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 29:S1–S39. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Long JW, Healy AH, Rasmusson BY, et al. Improving outcomes with long-term “destination” therapy using left ventricular assist devices. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:1353–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.09.124. [discussion 1360-1] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2241–2251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rush BS, Budge D, Alharethi R, et al. End-of-life decision making and implementation in recipients of a destination left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 29:1337–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rizzieri AG, Verheijde JL, Rady MY, et al. Ethical challenges with the left ventricular assist device as a destination therapy. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2008;3:20. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wingate SJ, Goodlin SJ. Where’s the data? Heart failure admissions to hospice. Journal of cardiac failure. 2006;12:S124. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berry JI. Hospice and heart disease: missed opportunities. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2010;24:23–26. doi: 10.3109/15360280903583081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomas JM, O’Leary JR, Fried TR. Understanding their options: determinants of hospice discussion for older persons with advanced illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:923–928. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1030-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF, et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000–2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:196–203. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaul P, McAlister FA, Ezekowitz JA, et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among patients with heart failure in Canada. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:211–217. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]